Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 viewsCotm# 12

Cotm# 12

Uploaded by

Jimmy BackwardsThis document summarizes a book about global unionism and a campaign against the security firm G4S led by several global unions including SEIU and UNI. The campaign involved negotiating a global framework agreement with G4S setting labor standards. Implementation of the agreement varied between countries and unions based on local contexts. In South Africa, organizing efforts by SATAWU improved after shifting to an organizing model supported by UNI. In India, two unions had differing approaches, with one following organizing and one relying on political lobbying. The book examines lessons from the campaign, including how global and local factors interact and the need for unions to innovate organizationally.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- Business Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisDocument12 pagesBusiness Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisAnish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Form U Abstract of The Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 (English Version)Document2 pagesForm U Abstract of The Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 (English Version)chirag bhojak0% (1)

- Pickaxe and RifleDocument277 pagesPickaxe and RifleJohn Hamelin100% (2)

- Does Traditional Workplace Trade Unionism Need To Change in Order To Defend Workers' Rights and Interests? and If So, How?Document11 pagesDoes Traditional Workplace Trade Unionism Need To Change in Order To Defend Workers' Rights and Interests? and If So, How?hadi ameerNo ratings yet

- TradeingDocument5 pagesTradeing7thestreetwalkerNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesTrade Union Literature Reviewc5qdk8jn100% (1)

- Industrial Relations AssignmentDocument5 pagesIndustrial Relations AssignmentangeliaNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Trade UnionsDocument6 pagesResearch Papers On Trade Unionsegabnlrhf100% (1)

- Research Paper On Labor UnionsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Labor Unionsefkm3yz9100% (1)

- Globalization and Collective Bargaining in NigeriaDocument7 pagesGlobalization and Collective Bargaining in NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of New Industrial Relations and Postulates of Industrial JusticeDocument17 pagesDynamics of New Industrial Relations and Postulates of Industrial Justicelakshay dagarNo ratings yet

- Bargaining Indicators PDFDocument202 pagesBargaining Indicators PDFMallinatha PNNo ratings yet

- Case Study - A GUF's Relationship With A Multinational CompanyDocument32 pagesCase Study - A GUF's Relationship With A Multinational CompanyabinNo ratings yet

- Cunningham 2009Document28 pagesCunningham 2009Rituparna Sinha ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Labor Union ThesisDocument8 pagesLabor Union Thesisalexisadamskansascity100% (2)

- Topic:Nexus Between Public Sector Employees and Effectiveness of Trade UnionismDocument8 pagesTopic:Nexus Between Public Sector Employees and Effectiveness of Trade UnionismThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Shyam SunderDocument20 pagesShyam SunderAbhinav JunejaNo ratings yet

- The - Impact - of - Trade - Unions - On - Employee - Performance 333Document23 pagesThe - Impact - of - Trade - Unions - On - Employee - Performance 333robertjeff313No ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics On Trade UnionsDocument4 pagesDissertation Topics On Trade UnionsPaperHelpWritingSingapore100% (1)

- WRITING EXAMPLE - Labor Relations Essay - IrfanDocument4 pagesWRITING EXAMPLE - Labor Relations Essay - IrfanIrfan AsganiNo ratings yet

- Trade Union in IndiaDocument4 pagesTrade Union in IndiaKirubakar RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Wcms 218879Document4 pagesWcms 218879Eric WhitfieldNo ratings yet

- Role and Relevance of Trade Unions in Contemporary Indian Industry by Mukesh BhavsarDocument7 pagesRole and Relevance of Trade Unions in Contemporary Indian Industry by Mukesh BhavsarMukeshBhavsarNo ratings yet

- Trade Unionin IndiaDocument4 pagesTrade Unionin IndiasubashtalatamNo ratings yet

- Integrated Handloom Cluster Development Programme: Is It Responding To The Learning's From UNIDO Approach?Document9 pagesIntegrated Handloom Cluster Development Programme: Is It Responding To The Learning's From UNIDO Approach?Mukund VermaNo ratings yet

- Labour in The New Industrial RelationsDocument14 pagesLabour in The New Industrial RelationsSoumya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Trade Unions On Promoting Industrial Relations in ZimbabweDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Trade Unions On Promoting Industrial Relations in ZimbabweThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Gig WorkersDocument12 pagesGig WorkersAryan MishraNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Globalization On Industrial RelationsDocument2 pagesThe Impact of Globalization On Industrial RelationsSharmistha MitraNo ratings yet

- EPW Vol. 57Document171 pagesEPW Vol. 57Neha VermaNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial SuccessionDocument17 pagesEntrepreneurial SuccessionColince UkpabiaNo ratings yet

- Gender and The Composition of Corporate Boards: A Ghanaian StudyDocument13 pagesGender and The Composition of Corporate Boards: A Ghanaian StudyAhmad Shah KakarNo ratings yet

- Industrial Policy With Conditionality Mazzucato RodrikDocument43 pagesIndustrial Policy With Conditionality Mazzucato RodrikmicorreosinusoNo ratings yet

- Employment RelationsDocument23 pagesEmployment RelationsAdabre AdaezeNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Trade UnionsDocument5 pagesDissertation On Trade UnionsSomeoneToWriteMyPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Labor Rights and ContractualizationDocument4 pagesLabor Rights and ContractualizationchinaoillahatNo ratings yet

- General Description of The Labour /industrial /issues: ExternalityDocument11 pagesGeneral Description of The Labour /industrial /issues: ExternalitysomebodyNo ratings yet

- Topic-Nestle Workers Struggle in Rudrapur, Uttarakhand:An Analysis of The Judiciary's Approach Towards Emplyer-Employee RelationshipDocument18 pagesTopic-Nestle Workers Struggle in Rudrapur, Uttarakhand:An Analysis of The Judiciary's Approach Towards Emplyer-Employee RelationshipAbhijat SinghNo ratings yet

- Competitive Intelligence and International BusinessDocument7 pagesCompetitive Intelligence and International BusinessKenjin SaiNo ratings yet

- Role of Labor Unions in LaborDocument4 pagesRole of Labor Unions in LaborMrunal LaddeNo ratings yet

- Employee Relation and RewardDocument28 pagesEmployee Relation and RewardFiona TanNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Research PapersDocument7 pagesTrade Union Research Papersgz7vxzyz100% (1)

- Brit J Industrial Rel - 2017 - Mustchin - Transnational Collective Agreements and The Development of New Spaces For UnionDocument25 pagesBrit J Industrial Rel - 2017 - Mustchin - Transnational Collective Agreements and The Development of New Spaces For Unionawalker041881No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Page 40 - 68Document29 pagesChapter 2 Page 40 - 68Naveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Non-Standard Employment PDFDocument112 pagesNon-Standard Employment PDFMallinatha PNNo ratings yet

- Unions and The Labor Market: SummaryDocument7 pagesUnions and The Labor Market: SummaryOona NiallNo ratings yet

- 13 - Breaking New GroundDocument2 pages13 - Breaking New GroundIls DoleNo ratings yet

- Journal 3Document252 pagesJournal 3MUSANJE GEOFREYNo ratings yet

- Carter Union AvoaviidanceDocument16 pagesCarter Union AvoaviidanceЈанко ЦветиновNo ratings yet

- Business Challenges in Globalization ContextDocument10 pagesBusiness Challenges in Globalization ContextSri HarshaNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Thesis PDFDocument8 pagesTrade Union Thesis PDFCheapPaperWritingServiceAnchorage100% (2)

- MA 50700 - Milestone #2 of Final Research Paper - Jose Zuniga, Agustin CanonicoDocument10 pagesMA 50700 - Milestone #2 of Final Research Paper - Jose Zuniga, Agustin Canonicobxqqhn9b8mNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1: ROLE OF TRADE UNION An Organizational Study at CSWMDocument80 pagesChapter-1: ROLE OF TRADE UNION An Organizational Study at CSWMMuhammed Althaf VKNo ratings yet

- Role of Trade UnionDocument80 pagesRole of Trade UnionMuhammed Althaf VKNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Labor RelationsDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Labor Relationsaflbvmogk100% (1)

- IPE - Adnan - 18508Document7 pagesIPE - Adnan - 18508Adnan SiddiqiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Collective BargainingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Collective Bargainingkgtsnhrhf100% (3)

- Polciy Brief #8 FinalDocument6 pagesPolciy Brief #8 FinalSerenaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Trade UnionDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Trade Unionhyz0tiwezif3100% (1)

- Kafaya Assign 21Document4 pagesKafaya Assign 21Umar FarouqNo ratings yet

- Mobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismFrom EverandMobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismLee H. AdlerNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Mercosur Of Civil Society" By Gerardo Caetano: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Mercosur Of Civil Society" By Gerardo Caetano: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Call of The Millons #11Document11 pagesCall of The Millons #11Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- ... We Are Nothing and We Should Be Everything... This Is The Call of The MillionsDocument14 pages... We Are Nothing and We Should Be Everything... This Is The Call of The MillionsJimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Cotm#7 Dec 2013Document15 pagesCotm#7 Dec 2013Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Call of The Millions 6Document12 pagesCall of The Millions 6Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Rizal NotesDocument4 pagesRizal NotesTifanny Araneta DalisayNo ratings yet

- 1 Basic Electrical Safety SafetycorDocument2 pages1 Basic Electrical Safety SafetycorHendri Agustinus KollyNo ratings yet

- Jagualing v. CA (Digest)Document2 pagesJagualing v. CA (Digest)Tini GuanioNo ratings yet

- Housing Manual - EnglishDocument86 pagesHousing Manual - EnglishJnanamNo ratings yet

- Judicial Review (Illegality) - 2Document4 pagesJudicial Review (Illegality) - 2Mahdi Bin MamunNo ratings yet

- 7-1 Notice of Special Meeting - ShareholdersDocument1 page7-1 Notice of Special Meeting - ShareholdersDaniel100% (4)

- Alabama House Bill 374 With AmendmentDocument11 pagesAlabama House Bill 374 With AmendmentUSA TODAYNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 200749 G.R. No. 208725 Cecilio Abenion Vs Pilipinas Shell PetroleumDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 200749 G.R. No. 208725 Cecilio Abenion Vs Pilipinas Shell PetroleumAthiena MangadangNo ratings yet

- Germany Questions by ThemeDocument5 pagesGermany Questions by ThemeRayyan MalikNo ratings yet

- Handbook On The Construction and Interpretation of The LawDocument1 pageHandbook On The Construction and Interpretation of The Lawlicopodicum7670No ratings yet

- Copia de Josefina ASTOUL - Essay - ToV - To What Extent Was The Treaty of Versailles FairDocument5 pagesCopia de Josefina ASTOUL - Essay - ToV - To What Extent Was The Treaty of Versailles FairBenita AlvarezNo ratings yet

- United Employees Union of Gelmart Industries Philippines (UEUGIP) vs. Noriel (1975)Document2 pagesUnited Employees Union of Gelmart Industries Philippines (UEUGIP) vs. Noriel (1975)Vianca Miguel100% (1)

- Plumbing Evolution in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesPlumbing Evolution in The Philippinesミスター ヤスNo ratings yet

- Article IV CITIZENSHIPDocument3 pagesArticle IV CITIZENSHIPItsClarenceNo ratings yet

- GKDocument24 pagesGKNavya KiranNo ratings yet

- Kilosbayan V ErmitaDocument16 pagesKilosbayan V Ermitaalexis_beaNo ratings yet

- January 2007 NSA PowerPoint On Bulk Collection of Telephony Metadata For AnalystsDocument18 pagesJanuary 2007 NSA PowerPoint On Bulk Collection of Telephony Metadata For AnalystsMatthew KeysNo ratings yet

- Summary Complete Intellectual Property NotesDocument125 pagesSummary Complete Intellectual Property NotesAdv Faisal AwaisNo ratings yet

- Emergency Management Disaster Preparedness Manager in Phoenix AZ Resume Don BrazieDocument2 pagesEmergency Management Disaster Preparedness Manager in Phoenix AZ Resume Don BrazieDonBrazieNo ratings yet

- Kanlungan Convention PaperDocument4 pagesKanlungan Convention PaperAi Vhee100% (1)

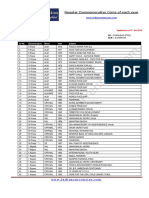

- Yearwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiaDocument4 pagesYearwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiashambhavNo ratings yet

- Local Literature: According To Atty. Manuel J. Laserna JRDocument2 pagesLocal Literature: According To Atty. Manuel J. Laserna JRMae Cruz0% (1)

- Antigua and BarbudaDocument15 pagesAntigua and BarbudaclovaliciousNo ratings yet

- 17udj050 CE ProofDocument2 pages17udj050 CE Proofsurya crazeNo ratings yet

- Cyberstalking and Cyberharassment LawsDocument3 pagesCyberstalking and Cyberharassment LawsBennet KelleyNo ratings yet

- ICTJ Report KAF TruthCommPeace 2014Document116 pagesICTJ Report KAF TruthCommPeace 2014sofiabloemNo ratings yet

- Information For SwissStudent VisaDocument1 pageInformation For SwissStudent VisaAnonymous ErgGsdNo ratings yet

Cotm# 12

Cotm# 12

Uploaded by

Jimmy Backwards0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views13 pagesThis document summarizes a book about global unionism and a campaign against the security firm G4S led by several global unions including SEIU and UNI. The campaign involved negotiating a global framework agreement with G4S setting labor standards. Implementation of the agreement varied between countries and unions based on local contexts. In South Africa, organizing efforts by SATAWU improved after shifting to an organizing model supported by UNI. In India, two unions had differing approaches, with one following organizing and one relying on political lobbying. The book examines lessons from the campaign, including how global and local factors interact and the need for unions to innovate organizationally.

Original Description:

international solidarity newsletter

Original Title

cotm# 12

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes a book about global unionism and a campaign against the security firm G4S led by several global unions including SEIU and UNI. The campaign involved negotiating a global framework agreement with G4S setting labor standards. Implementation of the agreement varied between countries and unions based on local contexts. In South Africa, organizing efforts by SATAWU improved after shifting to an organizing model supported by UNI. In India, two unions had differing approaches, with one following organizing and one relying on political lobbying. The book examines lessons from the campaign, including how global and local factors interact and the need for unions to innovate organizationally.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

29 views13 pagesCotm# 12

Cotm# 12

Uploaded by

Jimmy BackwardsThis document summarizes a book about global unionism and a campaign against the security firm G4S led by several global unions including SEIU and UNI. The campaign involved negotiating a global framework agreement with G4S setting labor standards. Implementation of the agreement varied between countries and unions based on local contexts. In South Africa, organizing efforts by SATAWU improved after shifting to an organizing model supported by UNI. In India, two unions had differing approaches, with one following organizing and one relying on political lobbying. The book examines lessons from the campaign, including how global and local factors interact and the need for unions to innovate organizationally.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 13

CALL OF THE MILLIONS # 12

the global challenge

special issue on global unionism today

book review p 2; interview p7.

This issue of cotm is devoted to global

unionism and organising and based

around the book 'Global Unions, Local

Power' by Jamie McCallum.

The book takes an extended look at the

nuts and bolts of what it calls the most

successful global campaign so far,

conducted against the security firm G4S.

In it McCallum brings together detailed

field research and a new view of labour

internationalism. Looking at the major

unions involved America's Service

Employees International Union (SEIU), the

Union Network International (UNI) and its

South African and Indian affiliates the

book tracks the achievement and

implementation of a global framework

agreement (GFA) across different societies.

This set of processes involved crucial

changes internal to the union bodies too,

which is summed up as a shift to a focus

upon organising.....

We begin with context. In the era

of globalised production, McCallum

argues that unions are having to

rethink their traditional focus upon

workers rights, acting instead to

contest the rules under which TNCs

operate, through 'governance

struggles'. In this contest, unions try

to change the TNC rule base to gain an

organising foothold, aware that state

powers and international law are today

too weak to secure workers legal

rights. In pinpointing these 'rules of

engagement' as a new site of struggle,

unions have tried three avenues of

advance social clauses, codes of

conduct and GFAs.

The organising story begins in USA

where the SEIU was looking to repeat

the organising success of Justice for

Janitors in a rapidly changing private

security industry. Tackling the US

sector meant dealing with Europeanowned companies and a reorientation

of the campaign onto a global footing.

SEIU also found it had to build the

organising capacity of its allies and

The last of these is the most

partners before they could be

promising, leading to direct bargaining effective campaigners. The

between unions and TNCs on labour

globalisation of its 'organising model'

standards throughout global supply

- uniting direct action with detailed

chains. A GFA directly challenges

corporate research was the way this

company power in the absence of

change came about.

workers rights - they construct new

rules and regulations that reorder the Different industrial relations

labour-capital relationship creating traditions loomed large here, creating

a framework for global union

some dissonance and obstacles e.g.

campaigns and long-term industrial

the more consensual industrial

strategies to build power across a

relations found between the UK's

sector or region.

GMB and G4S were threatened by the

McCallum pays particular attention confrontational American approach.

to the implementation of the G4S

In other settings things moved more

GFA, examining how it was used in

smoothly, Australia's LMHU eagerly

different states in different ways,

adopting the new organising model to

including its spur to new organising

revive their fortunes.

across Africa, USA, Brazil and

Australia.

Most important here were the links

SEIU forged with the UNI global

union federation, establishing a global

partnership that proved vital in its

battles with the Swedish security

firm Securitas and G4S. This involved

funding for UNI projects where GFAs

could not be easily established,

supplying training for reps and advice

on running corporate campaigns.

In the G4S case SEIU brought their

corporate campaigning techniques

centre stage. The strategy targets an

employer's financial interdependencies, political linkages and their

reputation through hard-hitting

negative publicity. This 'air war'

precedes the 'ground war' of

organising workplaces - a two-stage

process that effectively excludes

rank and file input from a strategy

designed from above, as McCallum

recognises.

In its early battles with Securitas,

SEIU worked with Swedish partners

STWF to gain a neutrality agreement

that allowed it access to workplaces.

In the US it came up against far

stronger opposition from the

Wackenhut corporation, forerunner of

G4S. When industry merger created

the second largest private firm in the

world in 2004, SEIU's response was

to commit to organising G4S on a

global scale.

They began with a struggle against the

casualisation of 15,000 guards in

Indonesia. By 2006 SEIU and the UNI

had established the G4S Alliance to

push forward their campaign,

especially within the Global South.

The signing of the GFA in 2008

led to far deeper global involvement

when South Africa and India were

chosen as the first sites to push the

GFA forwards. The Alliance had relied

on negative publicity, around the

equation of workers rights as human

rights, to pressure the employer into

signing the GFA. This focus continued

in the implementation phase. In terms

of its depth and scope the agreement

is the best achieved so far in the

arena of global organising.

It contained grievance and dispute

resolution mechanisms, higher

standards for workers and a

neutrality agreement allowing unions

access to organise G4S sites.

Organising advances around the globe

UK, Poland, Uganda, Malawi, Nepal

and DR Congo - were to follow.

drifted into a service union mentality.

The campaign here was as much about

reviving SATAWU as organising G4S

sites in fact the latter depended

upon the former.

After a damaging strike in 2006,

marred by violence, SATAWU moved

closer to the UNI and laid down an

organising plan with its financial

support. New committees of activists

were established at key sites, major

cities now became the focus of the

campaign. Despite this, prior to the

introduction of the GFA, SATAWU

had made little progress.

McCallum then turns to a detailed

analysis of the GFA's progress in

South Africa and India. It is evident

immediately that different industrial

relations systems play an important

role in this process: global does not

equal universal. Instead the outcomes The situation then began to change

register a plea for historical

and the union slowly gained a foothold

specificity, in theory and practice.

on G4S sites. Internal changes within

SATAWU were central to this success

story, a shift to a mode of organising

activity that paid off in terms of

membership and participation. As

McCallum notes this change was

powered both from above and below,

and from the outside by UNI. Local

and global forces are acting interdependently here.

In South Africa, the private

security sector had grown enormously

in recent years, helping turn G4S into

the largest employer in the whole

continent. SEIU UNI worked with

the SATAWU union, an outfit that

had made unsuccessful efforts to

organise G4S in the past, and then

Over in India the story was very

different, the campaign passing

through the fracturing prisms of local

industrial relations and political

affiliation. UNI SEIU worked with

two separate unions divided by

geography and political traditions, via

an umbrella coalition. The outcomes

were strikingly different.

In Bangalore, the PSUG partner

followed the organising model quite

closely, although the employer refused

to abide by the neutrality agreement

and continued to retaliate against reps

and activists.

Over in Kolkata, the CITU partner

resisted the UNI plan. Instead it

relied on its historic role as labour

broker for a vast informal workforce

to recruit members and political

lobbying of the Communist state

government for industrial relations

reforms. It even refused to prioritise

G4S as an organising site ahead of

other employers. The continued noncompliance of G4S with the GFA made

the political lobbying route even more

important.

This shows, says McCallum, that

different actors can use the GFA for

different kinds of gain. In India the

massive scale of the security sector

and a fractured industrial relations

context mean that the organising and

mobilising of its workforce remains a

huge challenge today.

In the final chapter of the book

McCallum draws out the theoretical

implications of his research. The G4S

campaign signals a new kind of labour

politics: the potential for workers to

flex their associational power in

'governance struggles' despite

operating in a context where their

structural power and legal rights are

weak.

Challenging the rules and winning the

GFA gave the unions involved a way

forwards both in respect of the

immediate employer and over the

wider industry. As an instrument of

union power, the GFA works best, says

the author, when it is part of a wider

industrial strategy than as a stand

alone procedure.

The impact of the GFA in the US

demonstrates this well. Though SEIU

only recruited 1000 new members, it

was vital to get a foothold within G4S,

in order to make organising other

major employers and the rest of the

US private security industry easier,

which in turn duly happened.

The interplay of global and local

factors is a second feature of the

G4S case. They combine in different

ways, translating global-level gains

into national contexts. The local

context can however determine the

specific strategy used by global unions

as the Indian example showed us.

And institutional and organisational

innovation within unions themselves

at both levels is a vital part of the

process. McCallum argues it is a

precondition to effective campaigning,

as the alliances SEIU forged here

show.

Most surprising among the lessons of

G4S is that has not proved an easy

model to emulate. The cost and

complexity of global organising a la

G4S have been too daunting and

SEIU itself has taken a step back

from the global stage.

...So plenty material to

reflect on there. We decided

to take things a step further

and ask Jamie McCallum a few

questions about his work.........

1 There are plenty critics of SEIU,

but you are not entirely of that view.

Given their role in conducting and

funding the most successful

transnational labour campaign so far,

why did they then 'move away' from

global organising? Were they right

to do so?

I dont think they have completely

moved away from it. I think that

some people within the union thought

that some of the campaigns were

long shots that wasted scarce

The case is controversial for another resources.

reason. Corporate campaigning and

Im not an insider and I dont have

governance struggles are top-down

access to all the debates that take

initiatives, putting a premium on

place. But my understanding is that

effective leadership and control a

many within SEIU feel that global

loose group of autonomous bodies

organizing is the future of their

could not have organised this mega

union.

TNC. Such a conclusion is massively

I think that UNI has maintained

out of step with the current focus on many of their commitments to

rank-and-file organising. As McCallum winning global framework

sums it up:

agreements. Other unions have

victory is not as simple as winning; it

backed away in more demonstrable

is about building the power to fight in

ways than SEIU.

the first place.

2 Is top-down, centralised control

the only way to wage war effectively

against TNCs today? What about the

work of other unions who have

developed smaller bilateral projects

that seem successful e.g. U E

FAT, or the UK's GMB alliance with

its Latin American partners under

the Bananalink banner?

No, its not the only way. But I am

less sanguine about a completely

uber-democratic (bottom-up)

movement against transnational

capital. Scholars are far more likely

to challenge me on this point than

unionists because unionists

understand that centralization and

consolidation of resources can

prepare them to fight in a better

way.

I think a lot of critics of the topdown model underestimate the

logistics and complexity of managing

and sustaining a global campaign, or

even one involving just two or three

countries. The necessity to keep all

the players on the same page is

critical and so far I havent seen it

work without a fair amount of

centralization.

3 Targeting TNC investors seems an

unlikely route for unions to build

workers power. Are you convinced

that these 'corporate campaigns'

deliver the goods, with the

investment community playing the

role of our surprising allies?

Great question. I agree that

corporate campaigns are unlikely to

build worker power. They can,

And to be clear, I dont know of

many wars against TNCs. There are however, create conditions more

campaigns, many of which are fairly favorable for workers to take action.

No one really thinks that corporate

tame and tepid. Youre right, those

campaigns are going to save labor.

alliances you mention seem

successful, but I dont have much

data to suggest that they are.

Theres a group I am starting to do

some work with called ReAct in

France. It has had some success with

smaller bilateral campaigns in

French-speaking Africa.

But what are the goods, as you put

it? The goods, in my opinion, is a

strategy that allows workers to take

action. I think corporate campaigns

have the potential to do that. This is

what I mean when I say governance

struggles. It allows unions to

exercise a degree of control over

what employers can do and this is

very important.

4 To the uninitiated the sketch of

Indian trade unions and industrial

relations seems almost too fantastic

for words - 66,000 registered trade

unions!! Were you surprised by the

scale and complexity of this stony

organising terrain?

The global-local dynamic is a major

issue, yes. I was primarily interested

in the influence of UNI and SEIU,

and that was pretty clear. Most

unions in India that worked with

them trusted them and did

transform to some degree. One was

more or less opposed to SEIU on

Yes, very surprised. Like many

some quasi-ideological grounds. But a

young(ish) scholars from the states, fair amount of change happened

I went to India a little nave, even

within SEIU too. As we talked about

though Id read a lot and talked with above, these campaigns put pressure

a handful of organizers before going. on the internal machination of the

The number of unions in India is

union.

possibly more like 100,000 actually.

But it wasnt just in India. UNI and

Its just unfathomable.

SEIU helped to build an organizing

Some people in India were

disappointed with UNIs role there, program at multiple unions in Europe,

with SEIUs role. They thought they the UK, Australia, South Africa,

should have accomplished more. But Poland. It was fairly committed to a

strategy of local union restructuring.

many of their in-country partners

This could be seen as bullying but I

were hamstrung by a lack of

think that would be a simplistic way

resources or state repression or

their own ideological blinders. Given of looking at it. SEIU clearly had

the circumstances, Im surprised as valuable experience, personnel, and

strategy to offer. The degree to

much happened as it did.

which SEIU, and some parts of UNI,

5 In the interplay of global and local are considered to be the

dynamics that is a key finding from organizers in Europe is a testament

your research, it often seems as if it to how attractive or useful its model

was.

is the global players who call the

shots. In the Indian example, who

changed most CITU or the UNI?

You might also like

- Business Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisDocument12 pagesBusiness Dealings in Emerging Economies, Non-Contractual Relations, and Recourse To Law - An AnalysisAnish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Form U Abstract of The Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 (English Version)Document2 pagesForm U Abstract of The Payment of Gratuity Act, 1972 (English Version)chirag bhojak0% (1)

- Pickaxe and RifleDocument277 pagesPickaxe and RifleJohn Hamelin100% (2)

- Does Traditional Workplace Trade Unionism Need To Change in Order To Defend Workers' Rights and Interests? and If So, How?Document11 pagesDoes Traditional Workplace Trade Unionism Need To Change in Order To Defend Workers' Rights and Interests? and If So, How?hadi ameerNo ratings yet

- TradeingDocument5 pagesTradeing7thestreetwalkerNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesTrade Union Literature Reviewc5qdk8jn100% (1)

- Industrial Relations AssignmentDocument5 pagesIndustrial Relations AssignmentangeliaNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Trade UnionsDocument6 pagesResearch Papers On Trade Unionsegabnlrhf100% (1)

- Research Paper On Labor UnionsDocument5 pagesResearch Paper On Labor Unionsefkm3yz9100% (1)

- Globalization and Collective Bargaining in NigeriaDocument7 pagesGlobalization and Collective Bargaining in NigeriaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of New Industrial Relations and Postulates of Industrial JusticeDocument17 pagesDynamics of New Industrial Relations and Postulates of Industrial Justicelakshay dagarNo ratings yet

- Bargaining Indicators PDFDocument202 pagesBargaining Indicators PDFMallinatha PNNo ratings yet

- Case Study - A GUF's Relationship With A Multinational CompanyDocument32 pagesCase Study - A GUF's Relationship With A Multinational CompanyabinNo ratings yet

- Cunningham 2009Document28 pagesCunningham 2009Rituparna Sinha ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Labor Union ThesisDocument8 pagesLabor Union Thesisalexisadamskansascity100% (2)

- Topic:Nexus Between Public Sector Employees and Effectiveness of Trade UnionismDocument8 pagesTopic:Nexus Between Public Sector Employees and Effectiveness of Trade UnionismThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Shyam SunderDocument20 pagesShyam SunderAbhinav JunejaNo ratings yet

- The - Impact - of - Trade - Unions - On - Employee - Performance 333Document23 pagesThe - Impact - of - Trade - Unions - On - Employee - Performance 333robertjeff313No ratings yet

- Dissertation Topics On Trade UnionsDocument4 pagesDissertation Topics On Trade UnionsPaperHelpWritingSingapore100% (1)

- WRITING EXAMPLE - Labor Relations Essay - IrfanDocument4 pagesWRITING EXAMPLE - Labor Relations Essay - IrfanIrfan AsganiNo ratings yet

- Trade Union in IndiaDocument4 pagesTrade Union in IndiaKirubakar RadhakrishnanNo ratings yet

- Wcms 218879Document4 pagesWcms 218879Eric WhitfieldNo ratings yet

- Role and Relevance of Trade Unions in Contemporary Indian Industry by Mukesh BhavsarDocument7 pagesRole and Relevance of Trade Unions in Contemporary Indian Industry by Mukesh BhavsarMukeshBhavsarNo ratings yet

- Trade Unionin IndiaDocument4 pagesTrade Unionin IndiasubashtalatamNo ratings yet

- Integrated Handloom Cluster Development Programme: Is It Responding To The Learning's From UNIDO Approach?Document9 pagesIntegrated Handloom Cluster Development Programme: Is It Responding To The Learning's From UNIDO Approach?Mukund VermaNo ratings yet

- Labour in The New Industrial RelationsDocument14 pagesLabour in The New Industrial RelationsSoumya MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Trade Unions On Promoting Industrial Relations in ZimbabweDocument10 pagesThe Influence of Trade Unions On Promoting Industrial Relations in ZimbabweThe IjbmtNo ratings yet

- Gig WorkersDocument12 pagesGig WorkersAryan MishraNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Globalization On Industrial RelationsDocument2 pagesThe Impact of Globalization On Industrial RelationsSharmistha MitraNo ratings yet

- EPW Vol. 57Document171 pagesEPW Vol. 57Neha VermaNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial SuccessionDocument17 pagesEntrepreneurial SuccessionColince UkpabiaNo ratings yet

- Gender and The Composition of Corporate Boards: A Ghanaian StudyDocument13 pagesGender and The Composition of Corporate Boards: A Ghanaian StudyAhmad Shah KakarNo ratings yet

- Industrial Policy With Conditionality Mazzucato RodrikDocument43 pagesIndustrial Policy With Conditionality Mazzucato RodrikmicorreosinusoNo ratings yet

- Employment RelationsDocument23 pagesEmployment RelationsAdabre AdaezeNo ratings yet

- Dissertation On Trade UnionsDocument5 pagesDissertation On Trade UnionsSomeoneToWriteMyPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Labor Rights and ContractualizationDocument4 pagesLabor Rights and ContractualizationchinaoillahatNo ratings yet

- General Description of The Labour /industrial /issues: ExternalityDocument11 pagesGeneral Description of The Labour /industrial /issues: ExternalitysomebodyNo ratings yet

- Topic-Nestle Workers Struggle in Rudrapur, Uttarakhand:An Analysis of The Judiciary's Approach Towards Emplyer-Employee RelationshipDocument18 pagesTopic-Nestle Workers Struggle in Rudrapur, Uttarakhand:An Analysis of The Judiciary's Approach Towards Emplyer-Employee RelationshipAbhijat SinghNo ratings yet

- Competitive Intelligence and International BusinessDocument7 pagesCompetitive Intelligence and International BusinessKenjin SaiNo ratings yet

- Role of Labor Unions in LaborDocument4 pagesRole of Labor Unions in LaborMrunal LaddeNo ratings yet

- Employee Relation and RewardDocument28 pagesEmployee Relation and RewardFiona TanNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Research PapersDocument7 pagesTrade Union Research Papersgz7vxzyz100% (1)

- Brit J Industrial Rel - 2017 - Mustchin - Transnational Collective Agreements and The Development of New Spaces For UnionDocument25 pagesBrit J Industrial Rel - 2017 - Mustchin - Transnational Collective Agreements and The Development of New Spaces For Unionawalker041881No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Page 40 - 68Document29 pagesChapter 2 Page 40 - 68Naveen KumarNo ratings yet

- Non-Standard Employment PDFDocument112 pagesNon-Standard Employment PDFMallinatha PNNo ratings yet

- Unions and The Labor Market: SummaryDocument7 pagesUnions and The Labor Market: SummaryOona NiallNo ratings yet

- 13 - Breaking New GroundDocument2 pages13 - Breaking New GroundIls DoleNo ratings yet

- Journal 3Document252 pagesJournal 3MUSANJE GEOFREYNo ratings yet

- Carter Union AvoaviidanceDocument16 pagesCarter Union AvoaviidanceЈанко ЦветиновNo ratings yet

- Business Challenges in Globalization ContextDocument10 pagesBusiness Challenges in Globalization ContextSri HarshaNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Thesis PDFDocument8 pagesTrade Union Thesis PDFCheapPaperWritingServiceAnchorage100% (2)

- MA 50700 - Milestone #2 of Final Research Paper - Jose Zuniga, Agustin CanonicoDocument10 pagesMA 50700 - Milestone #2 of Final Research Paper - Jose Zuniga, Agustin Canonicobxqqhn9b8mNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1: ROLE OF TRADE UNION An Organizational Study at CSWMDocument80 pagesChapter-1: ROLE OF TRADE UNION An Organizational Study at CSWMMuhammed Althaf VKNo ratings yet

- Role of Trade UnionDocument80 pagesRole of Trade UnionMuhammed Althaf VKNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Labor RelationsDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Labor Relationsaflbvmogk100% (1)

- IPE - Adnan - 18508Document7 pagesIPE - Adnan - 18508Adnan SiddiqiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Collective BargainingDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Collective Bargainingkgtsnhrhf100% (3)

- Polciy Brief #8 FinalDocument6 pagesPolciy Brief #8 FinalSerenaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review Trade UnionDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Trade Unionhyz0tiwezif3100% (1)

- Kafaya Assign 21Document4 pagesKafaya Assign 21Umar FarouqNo ratings yet

- Mobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismFrom EverandMobilizing against Inequality: Unions, Immigrant Workers, and the Crisis of CapitalismLee H. AdlerNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "The Mercosur Of Civil Society" By Gerardo Caetano: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "The Mercosur Of Civil Society" By Gerardo Caetano: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Call of The Millons #11Document11 pagesCall of The Millons #11Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- ... We Are Nothing and We Should Be Everything... This Is The Call of The MillionsDocument14 pages... We Are Nothing and We Should Be Everything... This Is The Call of The MillionsJimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Cotm#7 Dec 2013Document15 pagesCotm#7 Dec 2013Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Call of The Millions 6Document12 pagesCall of The Millions 6Jimmy BackwardsNo ratings yet

- Rizal NotesDocument4 pagesRizal NotesTifanny Araneta DalisayNo ratings yet

- 1 Basic Electrical Safety SafetycorDocument2 pages1 Basic Electrical Safety SafetycorHendri Agustinus KollyNo ratings yet

- Jagualing v. CA (Digest)Document2 pagesJagualing v. CA (Digest)Tini GuanioNo ratings yet

- Housing Manual - EnglishDocument86 pagesHousing Manual - EnglishJnanamNo ratings yet

- Judicial Review (Illegality) - 2Document4 pagesJudicial Review (Illegality) - 2Mahdi Bin MamunNo ratings yet

- 7-1 Notice of Special Meeting - ShareholdersDocument1 page7-1 Notice of Special Meeting - ShareholdersDaniel100% (4)

- Alabama House Bill 374 With AmendmentDocument11 pagesAlabama House Bill 374 With AmendmentUSA TODAYNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 200749 G.R. No. 208725 Cecilio Abenion Vs Pilipinas Shell PetroleumDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 200749 G.R. No. 208725 Cecilio Abenion Vs Pilipinas Shell PetroleumAthiena MangadangNo ratings yet

- Germany Questions by ThemeDocument5 pagesGermany Questions by ThemeRayyan MalikNo ratings yet

- Handbook On The Construction and Interpretation of The LawDocument1 pageHandbook On The Construction and Interpretation of The Lawlicopodicum7670No ratings yet

- Copia de Josefina ASTOUL - Essay - ToV - To What Extent Was The Treaty of Versailles FairDocument5 pagesCopia de Josefina ASTOUL - Essay - ToV - To What Extent Was The Treaty of Versailles FairBenita AlvarezNo ratings yet

- United Employees Union of Gelmart Industries Philippines (UEUGIP) vs. Noriel (1975)Document2 pagesUnited Employees Union of Gelmart Industries Philippines (UEUGIP) vs. Noriel (1975)Vianca Miguel100% (1)

- Plumbing Evolution in The PhilippinesDocument2 pagesPlumbing Evolution in The Philippinesミスター ヤスNo ratings yet

- Article IV CITIZENSHIPDocument3 pagesArticle IV CITIZENSHIPItsClarenceNo ratings yet

- GKDocument24 pagesGKNavya KiranNo ratings yet

- Kilosbayan V ErmitaDocument16 pagesKilosbayan V Ermitaalexis_beaNo ratings yet

- January 2007 NSA PowerPoint On Bulk Collection of Telephony Metadata For AnalystsDocument18 pagesJanuary 2007 NSA PowerPoint On Bulk Collection of Telephony Metadata For AnalystsMatthew KeysNo ratings yet

- Summary Complete Intellectual Property NotesDocument125 pagesSummary Complete Intellectual Property NotesAdv Faisal AwaisNo ratings yet

- Emergency Management Disaster Preparedness Manager in Phoenix AZ Resume Don BrazieDocument2 pagesEmergency Management Disaster Preparedness Manager in Phoenix AZ Resume Don BrazieDonBrazieNo ratings yet

- Kanlungan Convention PaperDocument4 pagesKanlungan Convention PaperAi Vhee100% (1)

- Yearwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiaDocument4 pagesYearwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiashambhavNo ratings yet

- Local Literature: According To Atty. Manuel J. Laserna JRDocument2 pagesLocal Literature: According To Atty. Manuel J. Laserna JRMae Cruz0% (1)

- Antigua and BarbudaDocument15 pagesAntigua and BarbudaclovaliciousNo ratings yet

- 17udj050 CE ProofDocument2 pages17udj050 CE Proofsurya crazeNo ratings yet

- Cyberstalking and Cyberharassment LawsDocument3 pagesCyberstalking and Cyberharassment LawsBennet KelleyNo ratings yet

- ICTJ Report KAF TruthCommPeace 2014Document116 pagesICTJ Report KAF TruthCommPeace 2014sofiabloemNo ratings yet

- Information For SwissStudent VisaDocument1 pageInformation For SwissStudent VisaAnonymous ErgGsdNo ratings yet