Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unit10 Feb2015 PDF

Unit10 Feb2015 PDF

Uploaded by

Jared OlivarezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Unit10 Feb2015 PDF

Unit10 Feb2015 PDF

Uploaded by

Jared OlivarezCopyright:

Available Formats

10

February 2015 beta

MARKET SUCCESSES

AND FAILURES

Courtesy of US Coastguard

WHY MANY, BUT NOT ALL, GOODS ARE BOUGHT AND SOLD IN

MARKETS. HOW MARKETS CAN WORK WELL, BUT SOMETIMES FAIL.

You will learn:

That the functioning of markets depends on the establishment of property rights and

enforcement of contracts by governments.

How market competition provides incentives for innovation.

Market failure arises from a lack of competition, or external effects such as pollution and

knowledge creation.

How these external effects can result in the misallocation of resources.

How private bargaining, government policy, or a combination of the two might improve

this allocation.

That the distribution of income among individuals depends on what they own (including

their skills), and on the prices at which these endowments are traded.

That for moral and political reasons some goods and services are not traded on markets,

but are allocated by other means.

See www.core-econ.org for the full interactive version of The Economy by The CORE Project.

Guide yourself through key concepts with clickable figures, test your understanding with multiple choice

questions, look up key terms in the glossary, read full mathematical derivations in the Leibniz supplements,

watch economists explain their work in Economists in Action and much more.

Funded by the Institute for New Economic Thinking with additional funding from Azim Premji University and Sciences Po

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

since the discovery of penicillin in 1928, the development of antibiotics

has brought huge benefits to mankind. Diseases that were once fatal are now

easily treatable with medicines that are cheap to produce. But the World Health

Organisation has recently warned that we are heading for a post-antibiotic era as

bacteria are becoming resistant: Unless we take significant actions to change how

we produce, prescribe and use antibiotics, the world will lose more and more of these

global public health goods and the implications will be devastating.

Not all markets work well. Bacteria become resistant to antibiotics when we use them

too often, in the wrong dosage or for conditions that are not caused by bacteria. In

India, where medicines are easily available over the counter in pharmacies without

a doctors prescription, doctors recognise that leaving the allocation of antibiotics to

the market is having damaging consequences. On the advice of unlicensed private

medical practitioners people use antibiotics when other treatments would be

better. The patients often stop taking the antibiotics to save money when they feel a

little better. This is exactly the pattern of use that will produce antibiotic-resistant

pathogens. But, for the patient, the treatment worked, and the unlicensed doctors

business will prosper. The challenge for the Indian government is how to regulate

the market without denying poor rural communities the chance to get the medicines

they need.

In The Wealth of Nations, Adam Smith explained how the owners of capital (motivated

by their individual desire for profit) and others (through their pursuit of a more

comfortable or pleasant life) would make economic decisions that would benefit

society as a whole. Capital would be invested where it was most productive, and the

consumption of goods and services would economise on societys scarce resources.

He wrote that each individual could be led by an invisible hand to promote an end

[the well-being of others] which was no part of his intention.

He also explained that this was not always the case, and that in many areas, such as

promoting education and limiting the powers of monopolies, government policies

were needed to promote social well-being and to ensure that markets work well.

We have studied a variety of marketsinstitutions in which buyers and sellers

are brought together to trade a good or a service. Smith reasoned that investors,

consumers and others exchange their goods on markets, and that a process of market

competition determines:

1. The prices at which people buy and sell.

2. The profitability of the capital owners investments.

We have studied market competition in Unit 6 where workers compete with each

other for jobs, and where firms compete to make profits by employing labour to

produce goods that they sell. In Units 7 and 8 we studied how firms compete when

selling their goods on markets that may be less or more competitive.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

How well markets work in reality, and what role markets should play in an economy,

are questions at the centre of political debate. Many people believe that markets

work well and that, except for special cases, the government should take a handsoff approach. Others think that we should use government policies to modify how

markets work, to ensure that the resulting allocations are fairand do not result in

unwanted side effects such as environmental degradation. Almost everyone thinks

that some things should not be bought and sold on markets, and should be allocated

in some other way.

At any point we see many different markets operating in an economy. We can

evaluate them by applying the criteria of Pareto efficiency and fairness to ask

whether the gains from trade in a particular market are fully exploited and are

fairly distributed. We can also ask whether the economy as a whole leads to a fair

distribution of the burdens and benefits of economic life.

One way to answer these questions is to consider the economy at a particular

moment, taking the existing knowledge, natural environment, technologies, skills,

population, and capital goods as given, and asking: how healthy is the economy

from the perspective of Pareto efficiency and fairness? We call this evaluation static

(meaning without change); it is a snapshot of the economy.

We can also evaluate the economy from a dynamic standpoint. A dynamic evaluation

is more like a film than a snapshot (because dynamic means changing). It draws our

attention to the introduction of new technologieslike the spinning jenny and the

other changes that account for historys hockey stick in Unit 1, such as the resources

devoted to education. A dynamic evaluation also asks if decisions we are making

today will affect the climate and natural environment for future generations.

In the previous unit we also showed that the prices at which goods and services are

bought and sold send messages to buyers and sellers, messages that motivate them

to consume, invest, and innovate in ways that sometimes result in the best use being

made of an economys productive potential. Are the messages sent by market prices

the right messages, ones that lead individuals promoting their own ends to make

decisions in the interest of others, including those who are not yet born?

In this unit we will evaluate different markets, and the workings of the market

system as a whole, demonstrating both successes and failures in the way they allocate

resources, and pointing out some reasons why most people do not support the idea

that everything ought to be for sale.

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

10.1 PROPERTY RIGHTS AND CONTRACTS

markets might seem to be everywhere in the economy, but this is not the

case. Firms, as we have seen in Unit 6, are organised hierarchically, not as a market.

Families do not allocate resources among parents and children by buying and selling.

Governments use the political process rather than market competition to determine

allocations of resources, such as the public road system.

In the past markets played a far smaller role in the economy. While people have

exchanged goods over long distances for at least 50,000 years, for most of human

history and prehistory there was no market in land or labour, because we didnt have

the conditions we needed to create a market. So what does a market require?

The most important requirement is private property. If something is to be bought

and sold, then it must be possible to claim the right to own it. You would hesitate

to pay for something unless you believed that others would acknowledge (and if

necessary protect) your right to keep it. Owning something, as we have seen in Unit

5, means two things: you can exclude others from using it, and you have the right to

any income that it creates including from the sale of it. Markets in land did not exist

through most of human history simply because individuals could not own land (in

many economies a farmer could exclude others from the land that he traditionally

used, but could not sell that land).

Markets in labour came into existence in two forms. The first was slavery, in which

the labourer himself or herself was sold. In the second and eventually more common

form, labour (meaning the activity of work) is not what is bought or sold. Instead the

employer buys the right to direct the workers activities during a specified period of

time, as we studied in Unit 6. The worker rents a willingness to be directed in this

way.

Therefore markets require a system of property rights, laws preventing theft or other

violations, and a means of enforcing and settling disputes regarding them.

Government has the important role of establishing and maintaining the legal

institutions supporting markets. The courts and police give governments the

ability to control theft, and the courts intervene in cases in which more than one

person claims ownership. Formal legal documents and a system of registration may

guarantee ownership of higher value goods, including land and houses.

If goods are privately owned, the only ways to acquire them are by buying them, or

being given them. Buying low-value tangible goods involves a straightforward swap

for money, but more complex transactions require contracts that can be used in court

as evidence that the parties agreed a transfer of ownership. For example, an author

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

may sign a contract giving a publisher the sole right to publish a book. Contracts

govern relationships that are to be maintained over a period of time, particularly

employment: in the labour market, a court upholds the right of the worker to work no

more than contracted hours.

Laws and legal traditions can also help markets function when they provide

compensation for individuals who are harmed by the actions of others. Liability

law, for example, ensures that if a firm sells a car with a design fault, and someone

is injured as a result, the firm must pay for the damage. Employers usually have

a duty of care towards their employees, requiring them to provide a safe working

environment.

The definition and enforcement of private property rights are the most essential

conditions for markets to work and governments, in the form of police and the

courts, are essential to provide these conditions.

But threats to the security of your possessions do not come only from other private

individuals. Governments powerful enough to enforce property rights always have

enough power to seize the goods of their citizens. In the 1950s Chinese peasants were

forced to surrender their land, animals and farm implements to collective ownership.

In Unit 1 we mentioned the importance of restraints on governments, so that we may

reasonably expect to enjoy the goods that we own and are able to profit from our

investments. Multinational firms considering investment in other countries factor in

the risk of the government seizing their assets. This is a real problem: the Venezuelan

government expropriated oil projects in the Orinoco Belt in 2007, for example. A

38% share of the projects was transferred from French, Norwegian, British and US

oil companies to the Venezuelan national oil company, giving it a controlling 78%

interest.

DISCUSS 1: PROPERTY RIGHTS AND CONTRACTS IN MADAGASCAR

Marcel Fafchamps and Bart Minten studied grain markets in Madagascar in 1997,

where the legal institutions for enforcing property rights and contracts were weak.

Despite this, they found that theft and breach of contract were rare. The grain

traders avoided theft by keeping their stocks very low and, if necessary, sleeping

in the grain stores. They refrained from employing additional workers for fear of

employee-related theft. When transporting their goods they paid protection money

and travelled in convoy. Most transactions took a simple cash and carry form. Trust

was established through repeated interaction with the same traders.

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

1. Do these findings suggest that strong legal institutions are not necessary for

markets to work?

2. Consider some market transactions in which you have been involved. Could

these markets work in the absence of a legal framework? How would they be

different?

3. Can you think of any examples of transactions where repeated interaction helps

to facilitate market transactions? Why might this be important even when a legal

framework is present?

Source: Fafchamps, M. and Minten, B. 2001. Property Rights in a flea market economy, Economic

Development and Cultural Change, 49(2), pp. 229-267.

10.2 MARKET FAILURE

where property rights exist, it is possible for markets to function. But, for a

market to function well, the messages that prices send must be the right ones. That

is, prices must measure the true scarcity of a good.

When prices send the wrong messages we have what is called a market failure. One

cause is a lack of competition. Competition among many buyers and sellers is an

essential part of Adam Smiths reasoning and, when it is absent or limited, the

invisible hand will not work.

We examined the implications of competition in Units 7 and 8. Firms facing little

competitionmonopolists or those producing differentiated goodsset their prices

above marginal cost. The price at which the good is sold then sends the wrong

message: the high price overstates the real scarcity of the good as indicated by its

marginal cost. The resulting allocation is not Pareto efficient: too little is sold, so

there is a deadweight loss. In contrast, firms in competitive markets are price-takers:

they produce where price is equal to marginal cost and the allocation maximises the

total surplus of the buyers and sellers.

But we also noted in Unit 8 that, even if a market is competitive, the allocation of

the good may not be Pareto efficient if the decisions of the buyers and sellers also

have costs or benefits for other people. Such an effect is known as an external cost or

external benefit, or simply an externality (you may also see externalities referred to as

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

external diseconomies and external economies for reasons like this), and this is a second

possible cause of market failure. Specifically, market failure occurs if consumers or

firms account for the direct costs and benefits to themselves when making decisions,

but not those imposed or conferred on others.

There are many economic decisions that have external effects:

If you use a car to travel to work, you contribute to traffic congestion for other

road users.

A firm that operates an incinerator produces fumes that lower the surrounding air

quality.

If you play music loudly at night, you disturb the sleep of your neighbours.

If a firm trains a worker, it may benefit from the workers increased skills; but if

the worker quits a different firm may receive the benefit.

When you are employed at a fixed wage, working harder brings no benefit to you,

but increases your employers profits.

When Kim (the farmer in Unit 4) contributes to the cost of an irrigation project,

other farmers will also benefit.

A country that invests in reducing carbon emissions helps to lower the risks of

climate change for other countries.

Several of these problems have the character of the social dilemmas we studied in

Unit 4. If you are a considerate person you probably care about your neighbours

sleep. But whenever the decision-maker does not take account of external effects

there is likely to be a misallocation of some resource. We have already seen in Unit

4 that if Kim takes into account only the costs and benefits to herself she will not

contribute to the irrigation project. The allocation of irrigation will not be Pareto

efficient.

As the list above illustrates, external costs or benefits arise in different contexts and

for different reasons. Climate change is a major social dilemma. An irrigation project

is a public good. Roads are (usually) a common property resource to which we all

have free access. The external effect of work effort arises because labour contracts

are incomplete. In other cases the externality seems to be an incidental side-effect.

The potential solutions for these problems differ too, but what they all have in

common is that the contracts, property rights, laws, markets and prices in the

economy do not provide incentives for individual consumers and firms to take into

account all the relevant costs and benefits of their decisions. Therefore some costs

and benefits are not reflected in market prices, resulting in a Pareto inefficient

allocation: there is a market failure.

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

10.3 MARKET FAILURE: POLLUTION EXTERNALITIES

when we analyse the gains from trade in markets for consumer goods such

as cars, books, clothes, or washing machines using the methods in Units 7 to 9, we

measure the gains to the buyers and sellers using consumer and producer surplus.

We must also include the external costs or benefits if others are affected by the

consumption or production of the good. We will use this approach to analyse the case

in which the production of a good creates an external cost in the form of pollution.

In the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe and Martinique (both part of France), the

pesticide Chlordecone was used on banana plantations from 1972 until 1993 to

kill banana weevil, reducing costs and boosting the plantations profits. As the

chemical was washed off the land into rivers that flowed to the coast it contaminated

freshwater prawn farms, the mangrove swamps where crabs were caught, and coastal

fisheries.

To investigate the implications of this kind of externality, Figure 1 shows the

marginal costs of growing bananas on an imaginary Caribbean island where a

fictional pesticide called Weevokil is used. The purple line is the marginal cost for

the growers, which we label as the marginal private cost (MPC). It slopes upward

because the cost of an additional tonne increases as the land is more intensively used,

which requires more Weevokil. The orange line shows the marginal cost imposed

by the banana growers on fishermenthe marginal external cost (MEC). This is the

cost of the reduction in quantity and quality of fish caused by each additional tonne

of bananas. Adding together the MPC and the MEC, we get the full marginal cost

of banana production: the marginal social cost (MSC). This is the brown line in the

diagram. The orange shaded area in the figure shows the costs imposed on fishermen

by plantations using Weevokil. At each level of production this is the difference

between the marginal social cost and the marginal private cost.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

900

Marginal social cost

800

Costs imposed on

fishermen by plantations

using Weevokil

700

Costs, $

600

500

Marginal private cost

Marginal external cost

400

300

200

100,000

90,000

80,000

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

100

Q, quantity of bananas (tonnes per year)

Figure 1. Marginal costs of banana production using Weevokil.

INTERACT

Follow figures click-by-click in the full interactive version at www.core-econ.org.

To focus on the essentials, we will consider a case in which the wholesale market for

bananas is competitive, and the market price is $400 per tonne. Then, if the banana

growers wish to maximise their profit, we know that they will choose their output

so that price is equal to marginal costthat is, marginal private cost. Figure 2 shows

that total output will be 80,000 tonnes at point A.

Although 80,000 tonnes maximises profits for banana producers, this does not

include the cost imposed on the fishing industry. You can see in Figure 2 that for

the first 38,000 tonnes, the price is greater than the MSC. Thinking about the

joint surplus of plantations and fisheries, we can see that this amount of banana

production is socially beneficial, even accounting for the pollution it causes. But

for every tonne of production above 38,000 the marginal cost to plantations and

fisheries together is greater than the revenue of $400 that the banana company

receives, decreasing the social surplus. It would be better to reduce production to

38,000.

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

900

Marginal social cost

800

Costs imposed on

fishermen by plantations

using Weevokil

700

600

Costs, $

$ 270

500

400

Marginal private cost

Price

300

200

100,000

90,000

80,000

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

100

0

10

Q, quantity of bananas (tonnes per year)

Figure 2. The choice of banana output.

In other words, production of 80,000 tonnes, when price equals MPC, is Pareto

inefficient. To see this, suppose that output was reduced by 1 tonne. This would

hardly affect banana profits (since price is equal to MPC) but fishermen would gain

$270. If the fishermen paid the plantation owners $135 (say) to reduce output by 1

tonne, everyone would be better off. They could do better still by reducing output

more. The Pareto efficient level of output would be 38,000 tonnes of bananas, at

which price equals MSC, and there are no further joint gains to be made.

10.4 EXTERNALITIES: POLICY AND DISTRIBUTION

the banana plantations use too much Weevokil and produce too many

bananas from a social point of view because they dont take account of the costs

imposed on fishermen. How can a society resolve such a problem? We shall see in the

next section that it may be possible to create conditions under which the fisherman

and the plantations can resolve it for themselves. Alternatively, a government might

intervene directly. There are several policies that could achieve the Pareto efficient

choice of pesticide and level of output, although they differ both in practicality and

their implications for the two industries.

Suppose that the government wants to achieve a reduction in the output of bananas

to the level that takes into account the costs for the fishermen. There are three ways

this might be done.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

1. Regulation. The government could cap banana output at 38,000 tonnes, the Pareto

efficient amount. This looks like a straightforward solution. On the other hand, if the

plantations differ in size and output it may be difficult to determine and enforce the

right cap for each one.

This policy would reduce the costs of pollution for the fishermen, and it would

lower the plantations profit: they would lose their surplus on each tonne of bananas

between 38,000 and 80,000.

2. Taxation. At the Pareto efficient quantity the marginal private cost is $295. The

price is $400. If the government puts a tax on each tonne of bananas produced equal

to $400 - $295 = $105, then the after-tax price received by plantations will be $295.

The light blue line in Figure 3 shows the after-tax price. Now, if plantations maximise

their profit they will choose point P1 where the after-tax price equals the marginal

private cost, and produce 38,000 tonnes.

900

Marginal social cost

800

Costs imposed on

fishermen by plantations

using Weevokil

700

Costs, $

600

500

400

Tax

300

Marginal private cost

Price

After tax price

received by

plantation

P1

200

100,000

90,000

80,000

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

100

Pareto efficient

quantity

Q, quantity of bananas (tonnes per year)

Figure 3. Using a tax to achieve Pareto efficiency.

The distributional effects of taxation are different from those of regulation. The

costs of pollution for fishermen are reduced by the same amount, but the reduction

in banana profits is greater, since the plantations pay taxes as well as reducing

output; in addition, the government receives tax revenue. The tax corrects the price

message, so that the plantations face the full social marginal cost of their decisions.

When the plantations are producing 38,000 bananas the tax is exactly equal to the

cost imposed on the fishermen. This approach is known as a Pigouvian tax, after the

economist who advocated it.

11

12

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

PAST ECONOMISTS

ARTHUR PIGOU

Arthur Pigou (1877-1959) was one of the first neoclassical economists to focus on

welfare economics: the analysis of the allocation of resources in terms of the wellbeing of society as a whole. Born in Ryde on the Isle of Wight, Pigou won several

awards during his studies at Cambridge in history, languages and moral sciences

(there was no dedicated economics degree at the time). He became a disciple

and protg of Alfred Marshall, and eventually succeeded him as professor of

Political Economy after Marshall manipulated the process in his favour. Although

Pigou was an outgoing and lively person when young, his experiences as a

conscientious objector and ambulance driver during the first world war, as well

as anxieties over his health, turned him into a recluse who hid in his office except

for lectures and walks.

Pigous economic theory was mainly focused on using economics for the good of

society, which is why he is sometimes seen as the founder of welfare economics.

His book Wealth and Welfare (1912) was described by Schumpeter as the greatest

venture in labour economics ever undertaken by a man who was primarily a

theorist, and provided the foundation for Economics of Welfare (1920). Together,

these works built up a relationship between a nations economy and the welfare

of its people. This was very much focused on happiness and well-being; concepts

such as political freedom and relative status were recognised as important

factors.

Pigou believed that reallocation of resources was necessary in the event of

what we would today call externalities, where the interests of a private firm or

individual had diverged from the interests of society. To solve this problem, Pigou

suggested the use of taxes, which now bear his name: Pigouvian taxes ensure that

producers face the true social costs of their decisions.

Pigou also wrote extensively on the labour side of welfare, such as the link

between short-run involuntary unemployment and labour demand, as opposed to

the effects of real wages (which he found to be less important than psychological

factors).

Despite both being heirs to Marshalls new school of economics, Pigou and

Keynes did not see eye-to-eye. Keyness The General Theory of Employment,

Interest and Money contained a critique of Pigous The Theory of Unemployment,

and Pigou felt that Keyness material was becoming too dogmatic and turning

students into identical sausages.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Although overlooked for much of the 20th century, Pigou paved the way for much

of labour economics and environmental policy. Pigouvian taxes were mostly

unrecognised until the 1960s but they have become a major policy tool for

reducing pollution and environmental damage.

3. Enforcing compensation. The government could require the plantation owners

to pay compensation for costs imposed on fisherman. The compensation required

for each tonne of bananas will be equal to the difference between the MSC and the

MPC, which is the distance between the brown and purple lines in the diagram.

Once compensation is included the MPC will be equal to the MSC, so plantations will

maximise profit by choosing point P2 in Figure 4 and producing 38,000 tonnes. The

grey area shows the total compensation paid. The fishermen are fully compensated

for pollution, and the plantations profits are equal to the true social surplus of

banana production.

900

Marginal social cost

800

700

Costs, $

600

500

P2

400

Marginal private cost

Price

300

100,000

90,000

80,000

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

Total

compensation paid

20,000

100

10,000

200

Pareto efficient

quantity

Q, quantity of bananas (tonnes per year)

Figure 4. The plantations compensate the fishermen.

The effect of this policy on the plantations profits is similar to the effect of the tax,

but the fisherman do betterthey, rather than the government, receive payment

from the plantations. Using calculus LEIBNIZ 20, part A, explains how the market

equilibrium fails to be Pareto efficient in presence of externalities. Part B shows how

a Pigouvian tax can re-establish Pareto efficiency.

13

14

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

LEIBNIZ

For mathematical derivations of key concepts, download the Leibniz boxes from

www.core-econ.org.

TEST YOUR UNDERSTANDING

Test yourself using multiple choice questions in the full interactive version at

www.core-econ.org.

When we identified 38,000 tonnes as the Pareto efficient level of output, we

implicitly assumed that growing bananas inevitably involves Weevokil pollution.

But that was not the case in Guadaloupe and Martinquethere were alternatives

to Chlordecone. If alternatives to Weevokil were available it would be inefficient to

restrict output to 38,000 tonnes, because if the plantations could choose a different

production method and the corresponding profit-maximising output, they could be

better off, and the fishermen no worse off.

The root of the problem was the use of Chlordecone, not the production of bananas.

The market failure occurred because the price of Chlordecone did not incorporate

the costs that its use inflicted on the fishermen, and so it sent the wrong message

to the firm. Its low price said: use this chemical, it will save you money and raise

profits, but it should have said: think about the downstream damage, and look for

an alternative way to grow bananas.

Of the three policies we considered, requiring the plantations to compensate the

fishermen would give them the incentive to find less polluting production methods,

and could in principle achieve an efficient outcome. But, for the other policies, it

would be better to regulate or tax the sale or the use of Chlordecone rather than the

production of bananas, to motivate them to find the best alternative to intensive

Chlordecone use.

If the tax on a unit of Chlordecone was equal to its marginal external cost, the price of

Chlordecone for the plantations would be equal to its marginal social costit would

be sending the right message. They could then choose the best production method

taking into account the high cost of Chlordecone, which would involve reducing

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

its use or switching to a different pesticide, and determine their profit-maximising

output. As with the banana tax, the profits of the plantations and the pollution costs

for the fisherman would fall; but the outcome would be better for the plantations,

and possibly the fisherman also, if Chlordecone rather than bananas were taxed.

Unfortunately, none of these remedies was used for two decades in the case of

Chlordecone, and the people of Guadaloupe and Martinique are still living with

the consequences. In 1993 it was finally recognised the social marginal cost of

Chlordecone use was so high that it should be banned altogether.

DISCUSS 2: POLICIES FOR POLLUTION

Which of the policies do you think should have been implemented? Which additional

facts you would like to know to answer this question? Evaluate the strengths and

weaknesses of each policy from the standpoint of Pareto efficiency and fairness.

10.5 EXTERNALITIES, BARGAINING AND PROPERTY RIGHTS

the economist ronald coase challenged the assumption that external costs

like those suffered by the fishermen require government intervention, arguing that

compensation can be negotiated privately.

Lets see how a private bargain might solve the problem of banana pesticide. Initially

it is not illegal to use Weevokil: the plantations have the right to use it, and they

produce 80,000 tonnes of bananas. This allocation and the incomes, environmental

effects and other outcomes represent the reservation position of the plantation

owners and fishermen. This is what they will get if they do not come to some

agreement.

For the fishermen and the plantation owners to negotiate, they would each have to be

organised so that a single person (or body) could make agreements on behalf of the

entire group. So lets imagine that a representative of an association of fishermen sits

down to bargain with a representative of an association of banana growers. To keep

things simple we will assume that, at present, there are no feasible alternatives to

Weevokil; so they are bargaining over the output of bananas.

15

16

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

PAST ECONOMISTS

RONALD COASE

Ronald Coase (1910-2013) had the insight

to argue that when one party is engaged in

an activity that has the incidental effect of

causing damage to another, a negotiated

settlement between the two would result in

a Pareto efficient allocation of resources. He

used the legal case of Sturges v. Bridgman to

illustrate his argument. The case concerned

Bridgman, a confectioner (candy maker) who

for many years had been using machinery

that generated noise and vibration.

This caused no external effects until his

neighbour Dr Sturges built a consulting room

on the boundary of his property, close to the

confectioners kitchen. The courts granted

the doctor an injunction that prevented

Bridgman from using his machinery.

Source: By Ionel141 (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/bysa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Coase pointed out that, once the doctors right to prevent the use of the machinery

had been established, the two sides could modify the outcome. The doctor would be

willing to waive his right to stop the noise in return for a compensation payment. The

confectioner would be willing to pay if the value of his annoying activities exceeded

the costs that they imposed on the doctor. Also, the courts decision would make no

difference to whether Bridgman continued to use his machinery. If the confectioner

had been granted the right to use it, the doctor would have paid him to stop if and

only if the doctors costs were greater than the confectioners profits.

In other words, private bargaining would ensure that the machinery was used if and

only if its use along with a payment to compensate the doctor made both better

off. Private bargaining would ensure that its use was Pareto efficient. Bargaining

is simply a way to make sure that the candy-maker takes account of not only the

private marginal costs of producing candy but also for the external costs imposed

on the doctor, that is, on the entire social costs. To the candy maker, the price of

using the annoying machinery (or using it during the doctors visiting hours) would

now send the right message, for it would include not only the costs of powering the

machine, wear and tear and so on, but also the costs of compensating the doctor.

Private bargaining could thus be a substitute for liability law in ensuring that those

harmed were paid compensation, and that those inflicting harm would make every

effort to avoid doing so.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

As long as private bargaining exhausted all the potential mutual gains, the result

would (by definition) be Pareto efficient, whatever the court decided. One could

object that the courts decision resulted in an unfair distribution of profits, but not

that the outcome was Pareto inefficient.

But Coase emphasised that this conclusion was of limited practical relevance

because of the costs of bargaining and other impediments to the parties exploiting

all possible mutual gains. For example, when there are a large number of parties

affected by decisions made by other individuals bargaining between the two sets of

parties will often be impossible unless they are organised into groups. These costs of

bargaining are sometimes called transaction costs and in their presence the outcome

of bargaining will not be Pareto efficient.

Coase also noted that the decision on who has rights has an impact on the incentives

to compromise. For example, the confectioner might have had to cease producing,

when it would have been relatively easy for the doctor to change his consulting

hours or improve the sound insulation and vibration resistance of the wall.

Coases analysis suggests that a lack of established property rights, and other

impediments leading to high transaction costs, can prevent the resolution of

externalities through bargaining. If there were a clear legal framework in which

one side initially owned the rights to produce (or to prevent production of) the

externality, and if these rights were tradable between the two parties in a market for

the externality, then there would be no need for further intervention. While this can

be a useful insight we also need to recognise, as he did, that establishing tradable

property rights is not easy, because of transaction costs.

Bargaining can fail for other reasons. Sometimes in Unit 4 players in the Ultimatum

Game failed to come to an acceptable agreement, both parties walking away empty

handed, when the Proposer claimed too large a slice of the pie.

Both sides should recognise that they could gain from an agreement to reduce output

to the Pareto efficient level. In Figure 5 the situation before bargaining begins) is

point A, and the Pareto efficient quantity is 38,000 tonnes. The gain for fishermen

(from cleaner water) if output is reduced from 80,000 to 38,000 is shown by the total

shaded area. The lost profit for plantations is the blue area, so the net social gain is

the remaining yellow area. The fishing industry could pay the plantations to reduce

output.

17

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

900

Marginal social cost

800

700

600

Costs, $

500

Net social gain

400

Loss of profit

Marginal private cost

Price

300

200

100,000

90,000

80,000

70,000

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

20,000

10,000

100

0

18

Pareto efficient

quantity

Q, quantity of bananas (tonnes per year)

Figure 5. The gains from bargaining.

The minimum acceptable payment is determined by what the plantations get in

the existing situation: their reservation profits. This would be the blue area, to

compensate them for loss of profit. If this minimum payment were the deal they

struck, the fishing industry would achieve a net gain from the agreement equal to the

net social gain, while plantations would be no better off.

The maximum the fishing industry would pay is (as in the case of the plantations)

determined by their fallback (reservation) position, and it is the sum of the blue and

yellow areas; in that case the plantations would get all of the net social gain, while

the fishermen would be no better off. Unit 5 showed us that the compensation they

agree on between these maximum and minimum levels will be determined by the

bargaining power of the two groups.

You may think it unfair that the fishermen need to pay for a reduction in pollution.

At the Pareto efficient level of banana production, not only is the fishing industry

still suffering from pollution, but it also has to pay to stop it getting worse. This

happens because we have assumed that the plantations have a legal right to use

Weevokil. An alternative legal framework could give the fishermen a right to clean

water. If that were the case, the plantation owners wishing to use Weevokil could

propose a bargain in which they paid the fishermen to give up some of their right to

clean water to allow the Pareto efficient level of banana production, which will be a

much more favourable outcome for the fishermen.

We have reached the same conclusion as for the doctor and confectioner. Pareto

efficiency can be achieved irrespective of the initial allocation of property rights

including the right to pollute; although only in the unlikely event that there are no

transaction costs or other impediments to bargaining. But the initial allocation has a

big effect on the distribution of income.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Coase knew that in practice there are always obstacles to bargaining. Transaction

costs are likely to be high in this case. Coase focused on externalities involving just

two parties; here many plantations and fisherman are involved. Each side needs

to appoint someone they trust to bargain for them, and agree how payments will

be shared within each industry. Secondly, it must be possible to measure the costs,

which is difficult when we are discussing pollution. Thirdly, the contract must be

enforceable. Having agreed to pay thousands of dollars, the fishermen must be able

to rely on the legal system to back them if a plantation owner does not reduce output

as agreed.

A further problem in the case of the fisherman is that they may not be able to afford

to pay a large sum to the plantations to persuade them to reduce output. They will

eventually have higher incomes if pesticide use is curtailed, but if they cannot pay

until this happens (or borrow the money) the difficulties of writing an enforceable

contract are exacerbated. We will see in Unit 11 why they are unlikely to obtain a

loan.

The pesticide example illustrates that, although the resolution of externalities

through bargaining does not require direct government intervention, the

government still has an important role. It needs to establish the initial allocation

of property rights, to determine the reservation position of each side, and a legal

framework for enforcing contracts so that property rights are tradable. And in

determining their reservation positions it has a big influence on the relative

incomes of the banana and fishing industries: both sides have an incentive to lobby

for a favourable allocation of property rights. In Guadeloupe and Martinique, the

plantation owners had close relationships with the local government; which perhaps

explains why the right to use Chlordecone persisted for so long.

DISCUSS 3: BARGAINING POWER

What do you know about this problem that might affect the bargaining power of the

plantation owners and the fishermen? Think of other things that might plausibly

affect their bargaining power.

19

20

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

DISCUSS 4: EXTERNALITIES AND MARKET POWER

Imagine that, in contrast to our example, there is a single banana plantation with a

large amount of market power (similar to the monopolies in Unit 7). Use the analysis

of firms with market power in Unit 7, and the analysis of external environmental

effects in this unit, to make a case for and against:

1. Making the banana market more competitive by breaking up the single

plantation into a large number of smaller producers (supposing this is possible).

2. Taxing the sale of bananas.

10.6 FAIRNESS: ENDOWMENTS, INCOME AND INEQUALITY

when we analyse the distributional consequences of an individual market, we

measure what individuals gain as a result of participatingtheir surplus. We have

seen, for example, that a firm with market power can increase its own surplus and

reduce that of consumers by setting a high price. But what determines the extent of

inequality in the distribution of resources in the market economy as a whole?

Imagine a country, Econesia, in which there are many islands. On each island

the natural resources and the skills of the population are suitable for one kind of

economic activity. The residents of Wheat Island grow grain and make bread, Goat

Island produces milk and meat, Coal Island is populated by miners, on Cotton Island

people grow cotton and make clothes, and so on. There are no firms; each family

owns the land and other resources for its work. At the weekly market (on Market

Island), people from all over the country buy and sell their produce. Each family

obtains income from selling its own produce, and uses it to buy other goods in the

market.

For every type of good produced there are many buyers and sellers; all markets are

perfectly competitive with the market prices equal to the marginal cost of producing

the good. And there are no externalities: no pollution, noise or traffic congestion. In

fact the allocation of goods in Econesia is Pareto efficient: there are no further trades

that could make anyone better off without making someone worse off.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

The distribution of income in Econesia is very unequal. On some islands most people

have low incomes and consequently a low standard of living. All Econesians work

hard, but there are other islands where the residents have much higher incomes.

Some people describe the life of the rich Econesians as ostentatious, and think that

they have more than they need. Others say that they are entitled to do what they like

with the fruits of their labour.

Why are some islands rich and others poor? The main difference in income comes

from the prices at which they can sell their produce in the market. There is a small

island that produces chocolate, which is in high demand all over Econesia. Since

there are relatively few suppliers, the equilibrium price is high and the expert

chocolate producers enjoy a high standard of living. Miners are poor, however;

although they are skilled workers, coal is abundant, and an alternative source of

energy is available from Oil Island. So the price of coal is low.

There is inequality between people who live on the same island, too. On Cotton Island

some families own extensive plantations. Others scrape a living on a tiny plot of land.

Should we attribute inequality in Econesia to the market system? Some people think

that the market prices are unfair: after all, miners work just as hard as chocolate

makers. But the prices reflect how much people all over Econesiarich and poor

value the products. There is little that producers of less-valued goods can do about

this, although an advertising campaign might help. The difference in the wealth

which residents have before they enter the market is the underlying source of

inequality. Each person has an endowment, consisting of the land and productive

resources inherited from their parents, together with their skills; they use their

endowment to produce an income. Some families are endowed with more land or

larger workshops than others. Some were lucky enough to be born on islands with

the resources and skills to produce highly-valued goods; others have endowments

that are worth far less, because people dont want to buy what they produce, or

because there are many others with similar endowments.

The story of Econesia illustrates that an important source of inequality in income

is the endowments that people can use to generate that income. For most people

in the world, their endowment consists mainly of their skills, which are enhanced

by education or vocational training, and they generate income by working for

an employer. Nevertheless the same mechanisms are at work: those whose skill

endowments can be used to produce goods and services that people value will

earn higher incomes, provided that they have access to a workplace with the other

resources required in production. Those who own these resources will also have

higher incomes.

Of course, this is not the only source of inequality; unlike those in Econesia, most

markets are not perfectly competitive. We know from Unit 5 that the institutions in

a society determine the distribution of bargaining power, and that those with more

21

22

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

bargaining powerlike the proposer in the Ultimatum Game in Unit 4 or the real

world plantation owners in Guadeloupe and Martiniquecan use it to take a large

share of the gains from trade.

Econesia has a democratic government. The government sets the rules under which

Market Island operates, ensuring that ownership rights and contracts are respected.

The government is considering a change in the distribution of income by regulating

the prices of some goods. We know from Unit 9 that this is likely to lead to excess

supply or demand. For example, if the government raises the price of coal above its

market clearing level, some miners may be unable to sell their output. An alternative

policy might be for the government to tax the sales of some goods (chocolate,

perhaps). This would probably raise the price of chocolate and reduce sales; however,

the tax revenue could be used to supplement the incomes of people on the poorest

islands. Or, since the fundamental source of inequality is the distribution of

endowments, it might be better to address it directlyby taxing more productive

land, for example.

But Econesia has competitive markets, no externalities and complete contracts.

Prices are sending the right messages to allocate goods efficientlychanging the

prices would distort the messages. If the people of Econesia care about the welfare

of others and want to reduce inequality and poverty there is an alternative policy

focusing on the fundamental source of the problemthe government could change

the distribution of endowments. The assets of Cotton Island could be shared more

equally between the residents: some of the land on the larger plantations could

be reallocated to those with smaller plots. Some of the productive land on Wheat

Island, which generates high incomes for the residents, could be redistributed to the

struggling miners.

Redistributing the endowments in Econesia could achieve a more equal society while

maintaining the efficiency of Econesias markets.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

DISCUSS 5: INEQUALITY AND COMMUNITY

How likely are Econesians to implement measures reducing inequalities?

In a 2000 article (LINK) Alberto Alesina and Eliana La Ferrera suggest that group

homogeneity is a key determinant of successful collective actions. Using US group

membership survey data, they show that individual participation in church, local

services and political activities is more likely in communities characterised by a

higher degree of racial homogeneity and less income inequality.

Source: Alesina, A. and La Ferrara, E. 2000. Participation in Heterogeneous Communities. Quarterly

Journal of Economics, pp. 847-904.

You may have wondered how things got to be the way they are in Econesia, and

whether they will stay that way if the government does not intervene. The original

settlers just took the land they wanted, so both luck and the use of force played a

part in determining todays distribution of income. The miners have only been poor

since the discovery and settlement of Oil Island; perhaps in future they will find new

production techniques and develop new products or skills to increase their incomes.

One problem in Econesia is that people cannot move from a poor island to a richer

one (unless the government redistributes land): the miners cannot go elsewhere to

work because they dont own land on other islands (and no one wants to buy their

land). In reality, although it may be costly for workers to change industries, they

can develop new skills through education and training. New opportunities arise as

a result of innovation and technological change, because products and markets are

continually evolving.

23

24

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

10.7 PUBLIC GOODS

markets are not the best way to determine the allocation of many kinds of goods

or services. We saw in Unit 6 that, within firms, tasks are assigned and resources

allocated by the command of management, not by the working of supply and

demand. As Coase pointed out, for the things that are done within firms, markets

are not the least-cost way to allocate resources. There is another large class of goods

and services for which this is also true. These are called public goods and they include

such things as a system of justice, national defence and weather forecasting, services

that are typically provided by governments rather than the market. Other examples

are the knowledge of the rules of multiplication or the view of the setting sun.

The defining characteristic of a public good is that if it is available to one person it

can be available to all at no additional cost. For a view of the setting sun, one more

person enjoying it does not deprive anyone else of enjoyment. This means that, once

the good is available at all, the marginal cost of making it available to additional

people is zero. Goods with this characteristic are sometimes called non-rival goods.

Pure public goods are non-rival goods from which others cannot be excluded.

Examples include a view of a lunar eclipse, knowing the time of day, and publically

broadcast signals such as weather forecasts or the news, for people in a particular

area.

For some public goods it is possible to exclude additional users, even though the

cost of their use is zero. Examples are satellite TV, the information in a copyrighted

book, or a film shown in an uncrowded cinema; it costs no more if an additional

viewer is there, but the owner can nonetheless require than anyone who wants to

see the film must pay a price. The same goes for a quiet road on which tollgates have

been erected. Drivers can be excluded (unless they pay the toll) even though the

marginal cost of an additional traveller is zero. Public goods from which people may

be excluded are sometimes called artificially scarce goods or club goods (as long as the

golf course is not crowded, adding a member costs nothing).

The opposite of public goods are private goods. Like the loaves of bread, dinners in

restaurants, pesetas divided between Ana and Beatriz, and boxes of breakfast cereal

that we have used as examples so far, private goods are both rival (more for Ana

means less for Beatriz) and excludable (Ana can prevent Beatriz from taking her

pesetas for herself).

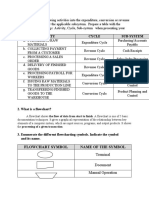

There is a fourth kind of good that is rival, but not excludable. Examples include

fisheries open to all: what one fisherman catches cannot be caught by anyone else,

and anyone who wants to fish can do so. Figure 6 summarises the four kinds of

goods.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

RIVAL

NON-RIVAL

EXCLUDABLE

Private goods (food,

clothes, houses)

Public goods that are artificially

scarce (subscription TV,

uncongested toll roads,

knowledge subject to intellectual

property rights, Unit 19)

NON-EXCLUDABLE

Common-pool

resources (fish stocks in

a lake, common grazing

land, Units 4 and 17)

Pure public goods and bads (view

of a lunar eclipse, public

broadcasts, rules of arithmetic or

calculus, national defence, noise

and air pollution, Units 17 and 19)

Figure 6. Private goods and public goods.

As can be seen from the examples, whether a good is private or public depends not

only on the nature of the good itself, but on legal and other institutions. For example,

knowledge that is not subject to copyright or other intellectual property rights would

be classified as a pure public good; but when an author has a monopoly on the right

to reproduce the work it is a public good that is artificially scarce. Another example:

common grazing land is a common-pool resource; but if the same land is fenced to

exclude other users, it becomes a private good.

Markets typically allocate private goods. But, for the other three kinds of good,

markets are either not possible or likely to fail. There are two reasons:

1. When goods are non rival the marginal cost is equal to zero and so setting a price

equal to a marginal cost (as is necessary for a Pareto efficient market transaction)

will not be possible unless the provider is subsidised.

2. When additional users cannot be excluded there is no way for the provider to

charge a price for the good or service.

It is not easy for governments to create public policy to achieve both Pareto efficient

and fair outcomes in cases where goods are not private. In the next section of this

unit and in Unit 20, we examine knowledge and intellectual property rights, and in

Unit 18 we return to common-pool resources and public bads.

25

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

26

DISCUSS 6: RIVALRY AND EXCLUDABILITY

For each of the following goods or bads, decide whether they are rival, and whether

they are excludable, and explain your answer. If you think the answer depends on

factors not specified here, explain how.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

A public lecture given at a university.

The noise produced by aircraft around an international airport.

A public park.

A forest used by local people to collect firewood.

Seats in a theatre.

Bicycles available for hire to the public to travel around a city

10.8 MARKETS AND INNOVATION

the television programme Dragons Den gives inventors three minutes to

pitch an idea for a new product to potential investors. They hope the investors will

back them with the finance needed to set up in business. We know more about the

successes, such as Reggae Reggae Sauce (created in 2007 by an entrepreneur called

Levi Roots, real name Keith Valentine Graham) and the ideas that had no hope of

being funded (a glove for drivers to wear on one hand to remind them which side

of the road to drive on) than about the credible investments that later failed. But

innovation almost always involves risky investments with uncertain returns, because

a new product or a new method of production typically requires new machinery, a

new way of organising sales or production, and other startup costs.

So far in our discussion of markets we have adopted a static viewpoint: given the

markets, firms, goods and workers that we observe in the economy now, are resources

allocated fairly and efficiently? But economies are continuously evolving and we

can also ask whether markets provide incentives for innovation and investment, to

improve the living standards of individuals and society in the future.

Successful innovation can contribute to rising living standards by expanding the set

of products available to consumers, and reducing the prices of existing products.

Many people in the world now have mobile phones, household appliances like

washing machines and vacuum cleaners, and access to entertainment such as films

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

and recorded music, all of which were unimaginable 100 years ago. Developments

in healthcare and pharmaceuticals have immeasurably improved the quality of life.

But innovation can be painful too. In Unit 2 we saw how the invention of the spinning

jenny contributed to the Industrial Revolution in England, but the first spinning

jennies were destroyed in attacks by workers who were worried that technology

would eliminate their jobs. As new products and industries are established, new

skills are needed, and workers with obsolete skills may suffer. The economist Joseph

Schumpeter (see Unit 2), who studied the role of the entrepreneur in society, called

the process of innovation and changing markets creative destruction.

We know that, in markets where many firms compete to sell identical or very similar

products, competition has the effect of reducing the price and expanding the

amounts produced so that the price approximates the marginal cost of production.

This is good for consumers because more goods are sold at a lower price; but it

lowers the profits of firms. A firm would prefer to be a monopolist or at least to sell a

differentiated good with unique characteristics not possessed by other products on

the market.

Competition thus gives firms the incentive to innovate. There are two ways in which

research and development (R&D) can create monopoly power. It might create a new

product, as attractive to consumers and as different from its competitors products

as possible. Toyotas hybrid car, the Prius, was a successful product innovation.

Alternatively a firm may find a better production process for an existing product.

If it can produce more cheaply than its competitors, profits will increase; if the cost

reduction is large it may even be able to set a price that other firms cannot match ,

and become a monopolist.

There is a catch, however. Monopoly power might not last long. Other firms will copy

a successful new product or process, increasing competition and reducing profits

again. For a firm to decide to invest in the R&D needed for successful innovation, it

must expect to be able to gain enough monopoly power, for long enough, to obtain a

return on its investment.

The problem for a firm is good news for the rest of us. For consumers and other firms,

this process of copying innovation reduces prices and makes desirable commodities

available. Since the 1980s competition between the worlds top mobile phone

companies such as Samsung (South Korea), Nokia (Finland), and Apple (US) has

stimulated a continuous process of product innovation and improvement in design

and capabilities, and further price competition. In 1996 Nokia combined a mobile

phone and Personal Digital Assistant in a single device and the smartphone was

born. Other companiesEricsson, Palm, Blackberry and NTT Docomodeveloped

the idea further, followed by Apples touchscreen device, the iPhone, in 2007. In 2013

world smartphone sales reached 1 billion.

The spinning jenny was a major process innovation. One worker operating a spinning

jenny could replace 12 spinsters with spinning wheels. Since wages in England were

high, it greatly reduced the costs of spinning cotton. Its inventor, James Hargreaves,

27

28

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

spent several years perfecting his machine, with the backing of a businessman

called Robert Peel. Their incentive was clear: together they hoped to go into textile

production, and if they had been able to prevent others from using their invention

they would have made high profits. But this part of the plan failed, and other textile

manufacturers quickly adopted the jenny. If copying is easy, new technology will

spread fast and consumers can benefit from cheaper goods, but the rents available to

innovators disappear faster and this may slow down the pace of innovation.

Hargreaves experience illustrates the risks of R&D. If copying is easy, new

technology will spread fast and consumers can benefit from cheaper goods, but the

economic rents available to innovators disappear faster and this may slow down the

pace of innovation. The innovator may not capture enough of the return to make

the investment worthwhile. We can think of knowledge as a public good. Once

a new product or process is known, others can profit from it, free riding on the

original investment. Governments can address free riding by granting a patent to

the innovator. A patent is a right of exclusive ownership of an idea, which lasts for

a specified length of time (typically 20 years). During this time it effectively allows

the owner to be a monopolist or exclusive user. Although this did not protect the

spinning jenny (Hargreaves discovered that he had invalidated his patent by selling

some early jennies) there are many examples of successful use of patents, such as the

prolific inventor Thomas Edison (1847-1931), who made a fortune in telegraphy and

electric power distribution .

DISCUSS 7: PATENTS

Knowledge is a public good. Once produced, it can be made available to everyone

without further cost: think of calculus or the ideas of Ronald Coase. Patents are a

way to reward a knowledge-producing company by granting it the exclusive right to

exploit the knowledge commercially for a fixed period.

Surprisingly, the chief executive of Tesla Motors (a US-based electric car company)

decided last June to make public all the patents its company owned. Technology

leadership is not defined by patents, which history has repeatedly shown to be small

protection indeed against a determined competitor, but rather by the ability of a

company to attract and motivate the worlds most talented engineers, he wrote in a

blogpost: LINK.

Do you understand Teslas decision? Do you think executives in pharmaceutical firms

would be willing to do similarly?

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Innovation involves a delicate balancing act for government policy. In established

markets competition lowers prices and increases gains from trade. Although change

may not benefit everyone, innovation can eventually raise our well-being. But

incentives for research and development (R&D) depend on solving the free rider

problem, perhaps by allowing monopoly power. In Unit 20 we will investigate how we

use patents in the trade-off between competition and monopoly.

Important innovations have emerged from combinations of public and private sector

R&D. The technology used to create the glass of iPhone screens is derived from

military research. In India, agricultural productivity has grown rapidly due to the

introduction of new seed varieties. Until the development of genetically modified

(GM) hybrids, research was conducted mainly by public sector organisations: private

companies could not profit from selling new varieties because once released, farmers

could produce new seed for themselves. But GM hybrids require repeat purchase

because second- generation seeds have low yields. This is one of the reasons why

private seed producing companies like hybrids. In the last 20 years competition

between plant biotechnology companies has led to the development of many new

hybrid seed varieties. Revolutionary insect-resistant cotton hybrids developed

through biotechnology have led to a boom in cotton exports. This is another example

of the delicate balance between monopoly power and R&D: the market power of

domestic and multinational biotech companies, and corporate control over seeds,

have caused concern, both about farmers dependence on multinational corporations

and environmental sustainability, but the new varieties have boosted the incomes of

Indian farmers.

While markets are powerful engines of innovation, there are some innovations

with large impacts on human well-being worldwide for which we need nonmarket

institutions, either to solve the free rider problem, or because the potential market is

small or lacks funding .

Consider, for instance, the case of vaccines. Using vaccines to eradicate a disease like

polio is both feasible and highly desirable. But this is almost impossible to achieve

through market mechanisms alone. No matter what the price of vaccination, there

will always be some people who are unable or unwilling to pay for them. This is

especially the case if the disease is rare, and the likelihood of contraction is perceived

to be low. Eradication needs a concerted global effort to vaccinate children without

exception and without charge. Historically, this has required coordinated action by

national governments and international agencies, sometimes with the assistance of

private foundations.

Here is a striking example. In 2009, there were 741 cases of polio in India, nearly

half the total number of reported cases. But on 13 January 2014, India marked three

years since its last reported polio case, and on 28 March 2014 it was officially declared

free of polio by the World Health Organisation. The eradication of polio in India

required 2.3 million vaccinators, and a large financial commitment by the national

government, the World Health Organisation, the Centres for Disease Control, the

29

30

coreecon | Curriculum Open-access Resources in Economics

United Nations Childrens Fund, Rotary International and the Gates Foundation. Polio

is now endemic only in Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Nigeria, although international

travel allows the virus to be transmitted across their borders.

Without commitments like this by nonmarket institutions, we might not even have

the vaccines. In 1955 the virologist Jonas Salk (1914-1995) developed the earliest

polio vaccine deemed safe for human use at the University of Pittsburgh School of

Medicine. He relied on funding from the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis

(now known as The March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation). The vaccine was never

patented, and Salk made no money from it.

10.9 POSITIONAL EXTERNALITIES

some goods, such as cars and clothes, may act as status symbols. Their owners

value them partly because they rank them above other people.

Perhaps one of your motives when you buy a car, or a coat, is to demonstrate your

wealth and superior style. Or perhaps you settle for a cheaper second-hand coat while

feeling envious, or embarrassed, or disadvantaged at a job interview. The economist

and sociologist Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) described the former as conspicuous

consumption: buying luxury items as a public display of social and economic status.

Goods that are valued more because they are expensive are known as Veblen goods.

Veblen goods are an example of a larger class called positional goods. They are

positional because they are based on status or power, which can be ranked as high or

low. Our positions in this rank, like the rungs of a ladder, may be higher or lower. But

there is only a fixed amount of a positional good to go around. If Maria is on a higher

rung of the ladder because of her new coat, somebody must now be on a lower rung.

The effect of positional goods on other people is a negative externality. To see its

implications, consider the case of Maria and her sister, moving with their families

to a new town. Each family has a choice between buying a luxury house or a more

modest one. Their payoffs are represented in Figure 7. Since both families have

limited funds they would be better off if both bought modest houses than if both

bought luxury ones, squeezing the rest of their budget. But, we already know that

Maria is status-conscious, and the two families are competitive when it comes to

lifestyle: if the Smiths buy a modest house, the Joneses can benefit from feeling

superior if they choose a luxury house. The Smiths, in turn, will feel miserable.

UNIT 10 | MARKET SUCCESSES AND FAILURES

Figure 7. Keeping up with the Joneses.

You can see that this problem has the

structure of a Prisoners Dilemma.

Whatever the Joneses do, the Smiths are

better off with a luxury house. For both

couples, choosing Luxury is a dominant

strategy. They will achieve a payoff

of 1 each, and the outcome is Pareto

inefficient, because both would be better

off if they bought modest houses. The

root of this problem is the external cost

that one family imposes on the other by

choosing a luxury house. The price of the

luxury house that Marias family will buy

does not include the positional externalities

that purchasing it inflicts on her sisters

family. If it did, Maria would not buy the

luxury house, given the payoffs in the

table.

What can they do to avoid the Pareto inefficient outcome? We know from Unit 4 that

altruism would help, but these families are not altruistic about houses. Following

Coases advice, they could agree in advance that if one family has a better house

they will compensate the other, with a payment chosen to make Modest a dominant

strategy. However, courts might be unwilling to enforce a contract like this.

The keeping up with the Joneses problem that Maria and her sister face arises

because people care not only about what they have, but also about what they have

relative to what other people have. This is sometimes called a Veblen effect.

Veblen effects help to explain two facts about modern economies:

1. People work longer hours in countries in which the very rich receive a larger

fraction of the income. For example, the US has both higher hours of work and

a higher income share of the very rich than Germany, France, Sweden and the

Netherlands. The rich are the Joneses who people want to keep up with. To do

this, they work longer hours if the Joneses are richer. A century ago American

workers worked fewer hours than workers in any of the countries just named.

But over the past century the share of income going to the very rich declined in

all these countries. Sweden, for example, went from one of the most unequal

countries (by this measure) to one of the most equal.

2. As a nation gets richer, its people sometimes do not become happier or more

satisfied with their lives. Economists measure happiness by a persons answer to