Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

Uploaded by

Evan KarapanosCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- UP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFDocument631 pagesUP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFCSWCD Aklatan UP DilimanNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Impact of Corporate Rebranding On Customer Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence From The Beverage IndustryDocument14 pagesInvestigating The Impact of Corporate Rebranding On Customer Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence From The Beverage Industryalidani92No ratings yet

- Difference Between PERT and CPM (With Comparison Chart) - Key DifferencesDocument11 pagesDifference Between PERT and CPM (With Comparison Chart) - Key DifferencesmalusenthilNo ratings yet

- Reporting and Sharing The FindingsDocument19 pagesReporting and Sharing The FindingsAhzi D. VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- UNGS 2080 Assignment Essay - Zubiya PDFDocument23 pagesUNGS 2080 Assignment Essay - Zubiya PDFZubiyaNo ratings yet

- MTTM - 16 Dissertation Proposal SamarjitDocument14 pagesMTTM - 16 Dissertation Proposal Samarjitsamarjit kumarNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in AI Development and DeploymentDocument4 pagesEthical Considerations in AI Development and DeploymentInnovation ImperialNo ratings yet

- Research: Research Is "Creative and Systematic Work Undertaken To Increase The Stock of Knowledge"Document19 pagesResearch: Research Is "Creative and Systematic Work Undertaken To Increase The Stock of Knowledge"sacNo ratings yet

- Masters IR EthicsDocument10 pagesMasters IR EthicsKirsty McKiddieNo ratings yet

- Assignment/ Term Paper Instruction: Please Choose Any One Option Which Is Suitable For YouDocument4 pagesAssignment/ Term Paper Instruction: Please Choose Any One Option Which Is Suitable For YouRahad IslamNo ratings yet

- Road Accidents in India 2008Document77 pagesRoad Accidents in India 2008DEBALEENA MUKHERJEENo ratings yet

- Bunge OkDocument31 pagesBunge OkJaskaran RaizadaNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Assessment of Industrial Engineering Graduates: Basis For Enhancing Industry Driven CurriculumDocument5 pagesCompetency-Based Assessment of Industrial Engineering Graduates: Basis For Enhancing Industry Driven CurriculumTech and HacksNo ratings yet

- Transmittal 1Document3 pagesTransmittal 1Yasuo DouglasNo ratings yet

- Application of Seismic Instantaneous Attributes in Gas Reservoir PredictionDocument7 pagesApplication of Seismic Instantaneous Attributes in Gas Reservoir Predictiondwi ayuNo ratings yet

- Probiotics - in Depth - NCCIHDocument17 pagesProbiotics - in Depth - NCCIHMuthu KumarNo ratings yet

- NCERT Solution For Cbse Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 ProbabilityDocument6 pagesNCERT Solution For Cbse Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 ProbabilityTeam goreNo ratings yet

- ISO 19036 - Measurement UncertaintyDocument76 pagesISO 19036 - Measurement UncertaintyHa Do Thi ThuNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6.flood Frequency AnalysisDocument37 pagesLecture 6.flood Frequency AnalysisLestor NaribNo ratings yet

- Directory of Institution - College 24012020011036777PMDocument10 pagesDirectory of Institution - College 24012020011036777PMravism3No ratings yet

- CEcover904 p2Document4 pagesCEcover904 p2Antonio MezzopreteNo ratings yet

- 2023 07 03 547464v1 FullDocument36 pages2023 07 03 547464v1 FullasdfsoidjfoiqjwefNo ratings yet

- Olson Et Al. (2019)Document13 pagesOlson Et Al. (2019)DavidNo ratings yet

- Logistic RegressionDocument12 pagesLogistic Regressionomar mohsenNo ratings yet

- 2014 Subiendo Student FAQs PDFDocument1 page2014 Subiendo Student FAQs PDFclementscounsel8725No ratings yet

- 'Working Conditions and Level of Satisfaction Among The Workers in Selected Tailoring and Dressmaking Establishments in Tacloban CityDocument68 pages'Working Conditions and Level of Satisfaction Among The Workers in Selected Tailoring and Dressmaking Establishments in Tacloban CityGrace SuperableNo ratings yet

- 2 - Template - Report and ProposalDocument6 pages2 - Template - Report and ProposalAna SanchisNo ratings yet

- The Economic Effects of The Protestant ReformationDocument58 pagesThe Economic Effects of The Protestant ReformationMbuyamba100% (1)

- Measurement in Education: By: Rubelyn P. PingolDocument14 pagesMeasurement in Education: By: Rubelyn P. PingolNafiza V. CastroNo ratings yet

- DAT101x Lab 3 - Statistical AnalysisDocument19 pagesDAT101x Lab 3 - Statistical AnalysisFederico CarusoNo ratings yet

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

Uploaded by

Evan KarapanosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

On The Retrospective Assessment of Users' Experiences Over Time: Memory or Actuality?

Uploaded by

Evan KarapanosCopyright:

Available Formats

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

On the Retrospective Assessment

of Users Experiences Over Time:

Memory or Actuality?

Evangelos Karapanos

Abstract

Eindhoven University of Technology

An alternative paradigm to longitudinal studies of user

experience is proposed. We illustrate this paradigm

through a number of recent tool-based methods. We

conclude by raising a number of challenges that we

need to address in order to establish this paradigm as a

fruitful alternative to longitudinal studies.

P.O. Box 513, 5600 MB, Eindhoven

The Netherlands

E.Karapanos@tue.nl

Jean-Bernard Martens

Eindhoven University of Technology

P.O. Box 513, 5600 MB,

Keywords

Eindhoven

J.B.O.S.Martens@tue.nl

User experience evaluation, longitudinal methods, retrospective techniques, day reconstruction, experience

sampling

Marc Hassenzahl

ACM Classification Keywords

Folkwang University

H5.2. User Interfaces: Evaluation/methodology.

The Netherlands

Universittsstrae 12, 45117 Essen

Germany

General Terms

marc.hassenzahl@folkwang-hochschule.de

Human Factors, Measurement, Theory

Introduction

Copyright is held by the author/owner(s).

CHI 2010, April 1015, 2010, Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

ACM 978-1-60558-930-5/10/04.

Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and User Experience in consequence have traditionally been interested

in users initial interactions with products. A growing

4075

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

interest is however attributed to the study of users

experiences over prolonged use [3-5, 11, 13, 15].

We [12] distinguished three dominant methodological

paradigms in understanding the change in users experience and behavior over time.

Cross-sectional approaches are the most popular in the

HCI domain [e.g. 18]. Such studies distinguish user

groups of different levels of expertise, e.g. novice and

expert users, or different lengths of ownership of a

product. Such approaches are limited as one may fail to

control for external variation and may falsely attribute

variation across the different user groups to the manipulated variable. Prmper et al. [18] already highlighted this problem, by showing that different definitions of novice and expert users lead to varying results.

Within-subject repeated sampling (pre-post) designs

study the same participants at two points in time. For

instance, Kjeldskov et al. [15] studied the same seven

nurses, using a healthcare system, right after the system was introduced to the organization and 15 months

later, while we [11] studied how 10 individuals formed

overall evaluative judgments of a novel pointing device,

during the first week of use as well as after four weeks

of using the product. While these studies inquire into

the same participants over an extended period of time,

one may not readily infer time effects as these might

be due to random contextual variation, given that we

have only two measurements.

Longitudinal designs take more than two measurements and, thus, enable greater insight into the exact

form of change. For instance, Minge [16] elicited judgments of perceived usability, innovativeness and the

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

overall attractiveness of computer-based simulations of

a digital audio player at three distinct points: a) after

participants had seen but not interacted with the product, b) after 2 minutes of interaction and c) after 15

minutes of interaction. In [13], we followed 6 individuals after the purchase of a single product over the

course of 5 weeks. One week before the purchase of

the product, participants started reporting their expectations. After product purchase, during each day, participants were asked to narrate the three most impactful experiences of the day.

While longitudinal studies are considered as the gold

standard in studying changes in users behavior and

experiences over time, they are increasingly laborious

when one needs to generalize over large populations of

users and products.

A fourth paradigm, aiming at providing a lightweight

alternative to longitudinal studies, relies on the retrospective elicitation of users experiences from memory.

Participants may be asked, within a single contact, to

recall the most salient experiences they had within a

given time period, and provide estimated temporal details regarding the recalled experiences. In the remainder of the paper we review existing approaches to the

retrospective assessment of temporal dynamics of experience and outline some of the challenges that we

need to address in order to establish this paradigm as a

fruitful alternative to longitudinal studies. Through this

position paper, we attempt to generate some discussion

on this avenue of research.

A review of retrospective methods

One of the most popular retrospective techniques is the

Day Reconstruction Method (DRM) proposed by Daniel

4076

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

Kahneman and colleagues [10] as an alternative to the

established Experience Sampling Method (ESM) [8].

DRM asks participants to reconstruct, in forward chronological order, all experiences that took place in the

previous day. Each experience is thus reconstructed

within a temporal context. Kahneman et al. [10]

showed that DRM provides a surprisingly good approximation to Experience Sampling data, while providing the benefits of a retrospective method. While DRM

has not been proposed as a longitudinal method, it may

well be applied as such. In [13], we employed DRM in

an ethnographic study of users experiences with

iPhone during the first 4 weeks of ownership. Khan [14]

proposed a tool that combines ESM and DRM in a longitudinal setting.

Can reconstruction be extended to longer periods of

time (e.g. full time of ownership of a product)? Von

Willamowitz et al. [20] proposed a structured interview

technique named CORPUS (Change Oriented analysis of

the Relation between Product and User). CORPUS starts

by asking participants to compare their current opinion

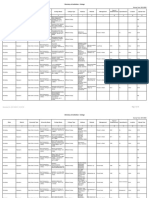

Figure 1. In iScale participants are

asked to sketch how their opinion has

changed from the moment of purchase

till the present. Each sketch is annotated by the respective time period and

participants are asked to narrate one or

more experiences that induced this

change in their perception of the respective product quality.

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

on a given product quality (e.g. ease-of-use) to the one

they had right after purchasing the product. If change

has occurred, participants are asked to assess the direction and shape of change (e.g., accelerated improvement, steady deterioration). Finally, participants

are asked to elaborate on the reasons that induced

these changes in the form of short narratives, the socalled change incidents.

One may wonder about the extent to which these data

suffer from retrospection biases. One could argue,

however, that this issue, the veridicality of reconstructed from memory experiences, is of minimal importance as these memories (1) will guide future behavior of the individual and (2) will be communicated to

others (Karapanos et al. [12], Norman [17]).

In [12] we argued that while the validity of these experience reports may not be as crucial, their reliability

is, in the sense that participants should at least report

the same experiences when asked repeatedly to report

their most impactful experiences with a product. In

other words, what we remember might be different

from what we experienced; however, as long as these

memories are consistent over multiple recalls, they

provide valuable information.

We proposed iScale [12], a survey tool that aims at

assisting users in reconstructing their experiences with

a product (see figure 1). iScale employs sketching in

imposing a specific procedure in the reconstruction of

ones experiences. We proposed and empirically validated two different versions of iScale, the Constructive

and the Value-Account iScale, each motivated by a distinct theory on how people reconstruct emotional experiences from memory [2, 19]. The Constructive iS-

4077

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

cale tool imposes a chronological order in the reconstruction of one's experiences. It assumes that "emotional experience can neither be stored nor retrieved"

[19, p. 935], but instead is re-constructed on the basis

of the recalled contextual details. Moreover, it assumes

that chronological reconstruction results in recalling

more contextual details surrounding the experienced

events [1] and consequently to a more reliable recall of

experiential information. The Value-Account iScale tool

explicitly distinguishes the elicitation of the two kinds of

information: value-charged (e.g. emotional) and contextual details. It assumes that value-charged information can be recalled without recalling concrete contextual details of an experienced event due to the existence of a specific memory structure, called ValueAccount, that stores the frequency and intensity of

one's responses to stimuli [2]. Overall, the constructive

iScale tool was found to outperform the Value-Account

iScale tool and to offer a significant improvement in the

amount, the richness and the test-retest reliability of

recalled information when compared to free recall, an

Figure 2. An example of Free-Hand

Sketching (the analog version of iScale, see [12]). Identified segments are

indicated by vertical lines. Each segment is coded for the type of experience report (1: Reporting a discrete

experience, 2: Reporting on attitude,

reasoning through experience, 3: Reporting on attitude with no further reasoning) and type of sketch (C: Constant, L: Linear, NL: Non-Linear, D:

Discontinuous).

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

approach that does not involve sketching in the recall

process [12]. Further, iScale was found to have a number of limitations, but also benefits, over its analog version, free-hand sketching.

Techniques like CORPUS and iScale provide two kinds

of data: a) self-reports of personal experiences that

induced the changes in the respective product quality,

over time and b) a recalled pattern of change on the

perceived product quality. Both techniques emphasize

qualitative data; sketches are seen as a way to assist

participants in reconstructing their experiences with a

product.

Analytic Scale is a lightweight technique for characterizing the temporal development of a judgment analytically. It relies on Value Account Theory [2] that assumes that people may recall an overall emotional assessment of an experience without recalling the exact

details of the experienced event. Participants are thus

asked in an analytic fashion to characterize the pattern

of change (if any). Participants are first asked to judge

whether this was improving, deteriorating, or stable. In

a second step, they are asked to further distinguish

between different patterns, for example, did it improve

in the beginning or at the end of the respective period,

or was it stable throughout the whole period or did it

follow some fluctuation ending approximately at the

same value?

Analytic Scale may firstly be employed in eliciting an

emotional assessment of an experience (e.g. how did

you feel while using the product?). This affective information is assumed to be directly accessible through

the hypothetical Value-Account memory. Secondly, it

may be employed in characterizing the temporal devel-

4078

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

opment of overall evaluations (e.g. goodness [6]) or

quality judgments (e.g. perceived ease of use) of a

product. In these later cases, only affect that is partially attributed to the product is used to reconstruct

the temporal development of the judgment [7].

Analytic Scale may be employed in characterizing the

temporal development on a macro-scale as in the case

of CORPUS and iScale (e.g. 6 months), but also on a

micro-scale (e.g. single interaction session). This latter

information may complement traditional experiential

evaluations in which participants are asked to summarize their experience in a single judgment. Despite their

practical value, such reductive evaluations have been

shown to reflect biased representations of experiences

(e.g. peak-and-end phenomenon [9]). The question is

thus: can the assessment of the temporal development

of emotion or judgment provide complementary information to the overall amplitude of an experience reflected in a single summative judgment of intensity?

Figure 3. Analytic Scale asks participants to characterize the temporal development of a judgment analytically.

Participants are first asked to judge

whether this was improving, deteriorating, or stable. In a second step, they

are asked to further distinguish between the three shapes, e.g. improved

in the beginning, at the end of the respective period, or linearly (parts

1/1a/1b).

1a

2a

3a

1b

2b

3b

Challenges to retrospective assessment:

Memory or actuality?

Perhaps the most crucial question is: how do these

memories differ from actual experiences, and, if so, for

which contexts are memories more important than actuality?

Kahneman [10] aimed at demonstrating close approximation of retrospective data elicited through the Day

Reconstruction Method to experiential data elicited

through the Experience Sampling Method. On the contrary, we [12] argued for reconstructing experiences

spanning greater lengths of time. They argued that

these memories may vary substantially from the actual

experiences. Reliability (i.e. consistency over multiple

recall trials) is more important than veridicality (i.e.

consistency between the memory and the experience),

they argued.

iScale was found to provide a substantial improvement

in the test-retest reliability of participants reconstruction process [12]. It thus provides meaningful information. But, what does this information represent, and in

what ways is it different from the actual experiences?

Are there systematic biases in these recalled experiences? For instance, we found user-perceived time to

relate to the actual time through a power-law. Participants were more inclined to recall experiences that

took place in the first month of use (75% of all recalled

experiences related to the first month while 95% related to the first six months) and participants sketches

reflected a logarithmic scale of time. These questions

are yet to be addressed and are crucial in order to establish retrospective techniques as an alternative to

longitudinal methods in HCI.

4079

CHI 2010: Work-in-Progress (Spotlight on Posters Days 3 & 4)

References

[1] Anderson, S.J. and Conway, M.A., Investigating the

structure of autobiographical memories. Learning.

Memory, 1993. 19(5): p. 1178-1196.

[2] Betsch, T., Plessner, H., Schwieren, C., and Gutig, R.,

I like it but I don't know why: A value-account approach to implicit attitude formation. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, 2001. 27(2): p. 242.

[3] Courage, C., Jain, J., and Rosenbaum, S., Best practices in longitudinal research, in Proceedings of the

27th international conference extended abstracts on

Human factors in computing systems. 2009, ACM:

Boston, MA, USA.

[4] Fenko, A., Schifferstein, H.N.J., and Hekkert, P., Shifts

in sensory dominance between various stages of user

product interactions. Applied Ergonomics, 2010.

41(1): p. 34-40.

April 1415, 2010, Atlanta, GA, USA

[11] Karapanos, E., Hassenzahl, M., and Martens, J.-B.,

User experience over time, in CHI '08 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems.

2008, ACM: Florence, Italy.

[12] Karapanos, E., Martens, J.B., and Hassenzahl, M.,

Reconstructing Experiences through Sketching. arXiv:0912.5343, 2009.

[13] Karapanos, E., Zimmerman, J., Forlizzi, J., and Martens, J.-B., User Experience Over Time: An initial

framework, in Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - CHI '09. 2009, ACM: Boston.

[14] Khan, V.J., Markopoulos, P., Eggen, B., Ijsselsteijn,

W., and de Ruyter, B. Reconexp: a way to reduce the

data loss of the experiencing sampling method. in

Proceedings of the 10th international conference on

Human computer interaction with mobile devices and

services 2008: ACM.

[5] Gerken, J., Bak, P., and Reiterer, H. Longitudinal

evaluation methods in human-computer studies and

visual analytics. in Visualization 2007: IEEE Workshop

on Metrics for the Evaluation of Visual Analytics. 2007.

[15] Kjeldskov, J., Skov, M.B., and Stage, J., A longitudinal

study of usability in health care: Does time heal? International Journal of Medical Informatics, 2008.

[6] Hassenzahl, M., The interplay of beauty, goodness,

and usability in interactive products. HumanComputer Interaction, 2004. 19(4): p. 319-349.

[16] Minge, M., Dynamics of User Experience, in Proceedings of the Nordichi '08 Workshop "Research Goals

and Strategies for Studying User Experience and Emotion". 2008.

[7] Hassenzahl, M. and Ullrich, D., To do or not to do:

Differences in user experience and retrospective

judgements depending on the presence or absence of

instrumental goals. Interacting with Computers, 2007.

19: p. 429-437.

[17] Norman, D.A., THE WAY I SEE IT. Memory is more

important than actuality. interactions, 2009. 16(2): p.

24-26.

[8] Hektner, J.M., Schmidt, J.A., and Csikszentmihalyi,

M., Experience sampling method: Measuring the quality of everyday life. 2007: Sage Publications Inc.

[18] Prmper, J., Zapf, D., Brodbeck, F.C., and Frese, M.,

Some surprising differences between novice and expert errors in computerized office work. Behaviour &

Information Technology, 1992. 11(6): p. 319-328.

[9] Kahneman, D., Fredrickson, B.L., Schreiber, C.A., and

Redelmeier, D.A., When more pain is preferred to

less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science,

1993: p. 401-405.

[19] Robinson, M.D. and Clore, G.L., Belief and feeling:

Evidence for an accessibility model of emotional selfreport. Psychological Bulletin, 2002. 128(6): p. 934960.

[10] Kahneman, D., Krueger, A.B., Schkade, D.A.,

Schwarz, N., and Stone, A.A., A Survey Method for

Characterizing Daily Life Experience: The Day Reconstruction Method. 2004, American Association for the

Advancement of Science. p. 1776-1780.

[20] von Wilamowitz Moellendorff, M., Hassenzahl, M., and

Platz, A., Dynamics of user experience: How the perceived quality of mobile phones changes over time, in

User Experience - Towards a unified view, Workshop

at the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction. 2006.

4080

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- UP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFDocument631 pagesUP System Administration Citizen's Charter Handbook - FINAL PDFCSWCD Aklatan UP DilimanNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Impact of Corporate Rebranding On Customer Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence From The Beverage IndustryDocument14 pagesInvestigating The Impact of Corporate Rebranding On Customer Satisfaction: Empirical Evidence From The Beverage Industryalidani92No ratings yet

- Difference Between PERT and CPM (With Comparison Chart) - Key DifferencesDocument11 pagesDifference Between PERT and CPM (With Comparison Chart) - Key DifferencesmalusenthilNo ratings yet

- Reporting and Sharing The FindingsDocument19 pagesReporting and Sharing The FindingsAhzi D. VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- UNGS 2080 Assignment Essay - Zubiya PDFDocument23 pagesUNGS 2080 Assignment Essay - Zubiya PDFZubiyaNo ratings yet

- MTTM - 16 Dissertation Proposal SamarjitDocument14 pagesMTTM - 16 Dissertation Proposal Samarjitsamarjit kumarNo ratings yet

- Ethical Considerations in AI Development and DeploymentDocument4 pagesEthical Considerations in AI Development and DeploymentInnovation ImperialNo ratings yet

- Research: Research Is "Creative and Systematic Work Undertaken To Increase The Stock of Knowledge"Document19 pagesResearch: Research Is "Creative and Systematic Work Undertaken To Increase The Stock of Knowledge"sacNo ratings yet

- Masters IR EthicsDocument10 pagesMasters IR EthicsKirsty McKiddieNo ratings yet

- Assignment/ Term Paper Instruction: Please Choose Any One Option Which Is Suitable For YouDocument4 pagesAssignment/ Term Paper Instruction: Please Choose Any One Option Which Is Suitable For YouRahad IslamNo ratings yet

- Road Accidents in India 2008Document77 pagesRoad Accidents in India 2008DEBALEENA MUKHERJEENo ratings yet

- Bunge OkDocument31 pagesBunge OkJaskaran RaizadaNo ratings yet

- Competency-Based Assessment of Industrial Engineering Graduates: Basis For Enhancing Industry Driven CurriculumDocument5 pagesCompetency-Based Assessment of Industrial Engineering Graduates: Basis For Enhancing Industry Driven CurriculumTech and HacksNo ratings yet

- Transmittal 1Document3 pagesTransmittal 1Yasuo DouglasNo ratings yet

- Application of Seismic Instantaneous Attributes in Gas Reservoir PredictionDocument7 pagesApplication of Seismic Instantaneous Attributes in Gas Reservoir Predictiondwi ayuNo ratings yet

- Probiotics - in Depth - NCCIHDocument17 pagesProbiotics - in Depth - NCCIHMuthu KumarNo ratings yet

- NCERT Solution For Cbse Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 ProbabilityDocument6 pagesNCERT Solution For Cbse Class 9 Maths Chapter 15 ProbabilityTeam goreNo ratings yet

- ISO 19036 - Measurement UncertaintyDocument76 pagesISO 19036 - Measurement UncertaintyHa Do Thi ThuNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6.flood Frequency AnalysisDocument37 pagesLecture 6.flood Frequency AnalysisLestor NaribNo ratings yet

- Directory of Institution - College 24012020011036777PMDocument10 pagesDirectory of Institution - College 24012020011036777PMravism3No ratings yet

- CEcover904 p2Document4 pagesCEcover904 p2Antonio MezzopreteNo ratings yet

- 2023 07 03 547464v1 FullDocument36 pages2023 07 03 547464v1 FullasdfsoidjfoiqjwefNo ratings yet

- Olson Et Al. (2019)Document13 pagesOlson Et Al. (2019)DavidNo ratings yet

- Logistic RegressionDocument12 pagesLogistic Regressionomar mohsenNo ratings yet

- 2014 Subiendo Student FAQs PDFDocument1 page2014 Subiendo Student FAQs PDFclementscounsel8725No ratings yet

- 'Working Conditions and Level of Satisfaction Among The Workers in Selected Tailoring and Dressmaking Establishments in Tacloban CityDocument68 pages'Working Conditions and Level of Satisfaction Among The Workers in Selected Tailoring and Dressmaking Establishments in Tacloban CityGrace SuperableNo ratings yet

- 2 - Template - Report and ProposalDocument6 pages2 - Template - Report and ProposalAna SanchisNo ratings yet

- The Economic Effects of The Protestant ReformationDocument58 pagesThe Economic Effects of The Protestant ReformationMbuyamba100% (1)

- Measurement in Education: By: Rubelyn P. PingolDocument14 pagesMeasurement in Education: By: Rubelyn P. PingolNafiza V. CastroNo ratings yet

- DAT101x Lab 3 - Statistical AnalysisDocument19 pagesDAT101x Lab 3 - Statistical AnalysisFederico CarusoNo ratings yet