Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter Eight

Chapter Eight

Uploaded by

Sandra Rodriguez0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views1 pageThis document contains a list of 65 endnotes citing various court cases, publications, and other references related to topics discussed in Chapter 8 such as architectural regulation, abortion access, race-restrictive housing covenants, encryption standards, and online worlds. The endnotes reference court decisions, journal articles, books, and news articles published between 1947 and 2000.

Original Description:

SD

Original Title

381

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document contains a list of 65 endnotes citing various court cases, publications, and other references related to topics discussed in Chapter 8 such as architectural regulation, abortion access, race-restrictive housing covenants, encryption standards, and online worlds. The endnotes reference court decisions, journal articles, books, and news articles published between 1947 and 2000.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

8 views1 pageChapter Eight

Chapter Eight

Uploaded by

Sandra RodriguezThis document contains a list of 65 endnotes citing various court cases, publications, and other references related to topics discussed in Chapter 8 such as architectural regulation, abortion access, race-restrictive housing covenants, encryption standards, and online worlds. The endnotes reference court decisions, journal articles, books, and news articles published between 1947 and 2000.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

0465039146-RM

12/5/06

12:31 AM

Page 367

notes to chapter eight

367

55. See New York v. United States, 505 US 144 (1992).

56. Lee Tien identifies other important problems with architectural regulation in Architectural Regulation and the Evolution of Social Norms, International Journal of Communications Law and Policy 9 (2004): 1.

57. Aida Torres, The Effects of Federal Funding Cuts on Family Planning Services,

19801983, Family Planning Perspectives 16 (1984): 134, 135, 136.

58. Rust v. Sullivan, USNY (1990) WL 505726, reply brief, *7: The doctor cannot explain

the medical safety of the procedure, its legal availability, or its pressing importance to the

patients health.

59. See Madsen v. Womens Health Center, Inc., 512 US 753, 785 (1994) (Justice Antonin

Scalia concurring in the judgment in part and dissenting in part: Todays decision . . . makes

it painfully clear that no legal rule or doctrine is safe from ad hoc nullification by this Court

when an occasion for its application arises in a case involving state regulation of abortion

[quoting Thornburgh v. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 476 US 747, 814

(1986) (Justice Sandra Day OConnor dissenting)]).

60. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 US 1 (1948).

61. See Herman H. Long and Charles S. Johnson, People Versus Property: Race-Restrictive

Covenants in Housing (Nashville: Fisk University Press, 1947), 3233. Douglas S. Massey and

Nancy A. Denton point out that the National Association of Real Estate Brokers adopted an

article in its 1924 code of ethics stating that a Realtor should never be instrumental in introducing into a neighborhood . . . members of any race or nationality . . . whose presence will

clearly be detrimental to property values in that neighborhood (citing Rose Helper, Racial

Policies and Practices of Real Estate Brokers [1969], 201); they also note that the Fair Housing

Authority advocated the use of race-restrictive covenants until 1950 (citing Kenneth T. Jackson,

Crabgrass Frontier: the Suburbanization of the United States [1985], 208); American Apartheid:

Segregation and the Making of the Under Class (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1993), 37, 54.

62. See Massey and Denton, American Apartheid.

63. Michael Froomkin points to the Clipper chip regulations as another example. By

using the standards-setting process for government purchases, the federal government could

try to achieve a standard for encryption without adhering to the Administrative Procedure

Act. A stroke of bureaucratic genius lay at the heart of the Clipper strategy. Congress had not,

and to this date has not, given the executive branch the power to control the private use of

encryption. Congress has not even given the executive the power to set up an escrow system

for keys. In the absence of any formal authority to prevent the adoption of unescrowed cryptography, Clippers proponents hit upon the idea of using the governments power as a major

consumer of cryptographic products to rig the market. If the government could not prevent

the public from using nonconforming products, perhaps it could set the standard by purchasing and deploying large numbers of escrowed products; It Came from Planet Clipper, 15,

24, 133.

64. See The Industry Standard, available at link #51.

65. See Legal Eagle (letter to the editor), The Industry Standard, April 26, 1999 (emphasis

added).

CHAPTER EIGHT

1. Castronova, Synthetic Worlds, 207.

2. Declan McCullagh, Its Time for the Carnivore to Spin, Wired News, July 7, 2000,

available at link #52.

You might also like

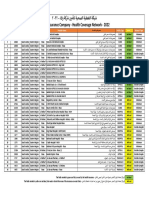

- Walaa Network 2022 شبكة التغطية الصحية-تامين شركة ولاءDocument1 pageWalaa Network 2022 شبكة التغطية الصحية-تامين شركة ولاءMohammed SulimanNo ratings yet

- Con Law II ChecklistDocument12 pagesCon Law II Checklistjclavet39No ratings yet

- Worksheet No. 5Document2 pagesWorksheet No. 5Xie Zhen WuNo ratings yet

- Maggi ComebackDocument7 pagesMaggi ComebackAnikNo ratings yet

- Interring The Nondelegation DoctrineDocument43 pagesInterring The Nondelegation DoctrinericardonevesNo ratings yet

- The United States: Constitutional Law, Edited by Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (WashDocument1 pageThe United States: Constitutional Law, Edited by Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (WashSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter FourteenDocument1 pageChapter FourteenSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id3530136Document94 pagesSSRN Id3530136larpNo ratings yet

- Whittington (2005) - James Madison Has Left The Building PDFDocument22 pagesWhittington (2005) - James Madison Has Left The Building PDFMarcosMagalhãesNo ratings yet

- The Myth of OwnershipDocument35 pagesThe Myth of OwnershipRenan GomesNo ratings yet

- Seperation of Powers An The Growth of Judicial ReviewDocument28 pagesSeperation of Powers An The Growth of Judicial ReviewSuatNo ratings yet

- The Ethereal Scholar: Does Critical Legal Studies Have What Minorities Want?Document22 pagesThe Ethereal Scholar: Does Critical Legal Studies Have What Minorities Want?Yau-Hei ChaiNo ratings yet

- Norms GameDocument18 pagesNorms GameMiguel GutierrezNo ratings yet

- The Yale Law Journal Volume 78 Issue 2 1968 (Doi 10.2307 - 795063) Lionel H. Frankel - Preventive Restraints and Just Compensation - Toward A PDFDocument40 pagesThe Yale Law Journal Volume 78 Issue 2 1968 (Doi 10.2307 - 795063) Lionel H. Frankel - Preventive Restraints and Just Compensation - Toward A PDFMariusNo ratings yet

- National Human Rights Institutions - Good Governance Perspectives C Raj Kumanr (2003)Document40 pagesNational Human Rights Institutions - Good Governance Perspectives C Raj Kumanr (2003)Art ManfredNo ratings yet

- Yale Law Journal Company, IncDocument36 pagesYale Law Journal Company, IncDiogo AugustoNo ratings yet

- 2016 Practicing - Internal - Selfdetermination - Visavis - Vital - Quests - For - SecessionDocument28 pages2016 Practicing - Internal - Selfdetermination - Visavis - Vital - Quests - For - SecessionLuca CapriNo ratings yet

- Norms and Values. Rethinking The Domestic Analogyl - Friedrich Kratochwil (E&IA)Document25 pagesNorms and Values. Rethinking The Domestic Analogyl - Friedrich Kratochwil (E&IA)NicoNo ratings yet

- Thomas W. Hazlett, "Physical Scarcity, Rent Seeking, and The First Amendment," Columbia Law Review 97 (1997) : 905, 933-34Document1 pageThomas W. Hazlett, "Physical Scarcity, Rent Seeking, and The First Amendment," Columbia Law Review 97 (1997) : 905, 933-34Sandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Backsliding: Andrew T. Guzman & Katerina LinosDocument52 pagesHuman Rights Backsliding: Andrew T. Guzman & Katerina LinosailopiNo ratings yet

- Social EntrepeneurDocument19 pagesSocial EntrepeneurenlumyenedNo ratings yet

- Landau 5Document65 pagesLandau 5Victor MedinaNo ratings yet

- "Drown The World": Imperfect Necessity and Total Cultural RevolutionDocument86 pages"Drown The World": Imperfect Necessity and Total Cultural RevolutionMatthew ParhamNo ratings yet

- Internal Colonialism and Humanitarian InterventionDocument34 pagesInternal Colonialism and Humanitarian InterventionManzoor NaazerNo ratings yet

- Beyond - Social MediaDocument19 pagesBeyond - Social Mediagdickinson.junkmailNo ratings yet

- 2009 Rothschild (Workers Cooperatives and Social Enterprise)Document19 pages2009 Rothschild (Workers Cooperatives and Social Enterprise)BazikstanoNo ratings yet

- Challenging and Refining The "Unwilling or Unable" DoctrineDocument75 pagesChallenging and Refining The "Unwilling or Unable" DoctrineKkNo ratings yet

- The Race To The Bottom Hypothesis: An Empirical and Theoretical ReviewDocument20 pagesThe Race To The Bottom Hypothesis: An Empirical and Theoretical ReviewBenjamin Goo KWNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Review Explosion of Foi 2006Document47 pagesAdmin Law Review Explosion of Foi 2006Ed996No ratings yet

- Literature Review 1Document4 pagesLiterature Review 1api-534381583No ratings yet

- Eternity ClausesDocument20 pagesEternity ClausesAnna Isack KaswalalaNo ratings yet

- Washington20 20state Round6Document35 pagesWashington20 20state Round6Wazeen HoqNo ratings yet

- Actio Popularis - The Class Action in International LawDocument51 pagesActio Popularis - The Class Action in International LawYaki RelevoNo ratings yet

- Constitutions and Their Ideal TypesDocument14 pagesConstitutions and Their Ideal TypesEve AthanasekouNo ratings yet

- The Limitation of LibertyDocument16 pagesThe Limitation of LibertyRistie LimbagNo ratings yet

- Vermuele Veil RulesDocument35 pagesVermuele Veil RulesLuis Patricio Garcia RamosNo ratings yet

- The Ethereal Scholar - Does Critical Legal Studies Have What Minor-3Document23 pagesThe Ethereal Scholar - Does Critical Legal Studies Have What Minor-3Marcelo Carvalho-LoureiroNo ratings yet

- Women and Reproduction The Case of ChileDocument26 pagesWomen and Reproduction The Case of ChileLIDIA CECILIA CASAS BECERRANo ratings yet

- Legal PhilosophyDocument57 pagesLegal PhilosophyMylene Muncal-AquinoNo ratings yet

- Constitutional HandcuffsDocument54 pagesConstitutional HandcuffsEnrique Chaves LópezNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 49.150.0.228 On Fri, 05 Apr 2019 07:48:12 UTCDocument16 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 49.150.0.228 On Fri, 05 Apr 2019 07:48:12 UTCPen ValkyrieNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1148802Document13 pagesSSRN Id1148802kkskNo ratings yet

- Directive Principles and The Expressive Accommodation of Ideological DissentersDocument32 pagesDirective Principles and The Expressive Accommodation of Ideological Dissenters61 Neelesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Regime Progress: Towards International Small Trade: and ProblemsDocument21 pagesRegime Progress: Towards International Small Trade: and ProblemsLucyNo ratings yet

- Schur CriticalRaceTheory 2009Document19 pagesSchur CriticalRaceTheory 2009abdulazeez FatimaNo ratings yet

- 82 4 Johanningmeier PDFDocument28 pages82 4 Johanningmeier PDFstorontoNo ratings yet

- CROSS The Error of Positive Rights 48UCLALRev857Document69 pagesCROSS The Error of Positive Rights 48UCLALRev857Rorro ProofNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Cusotmary International LawDocument67 pagesA Theory of Cusotmary International Lawjignan90No ratings yet

- Issachroff 2099Document59 pagesIssachroff 2099Paulo Anós TéNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 10 Oct 2021 23:03:01 UTCDocument12 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 34.195.88.230 On Sun, 10 Oct 2021 23:03:01 UTCmarting91No ratings yet

- Are Constitutional State of Emergency Clauses Effective? An Empirical ExplorationDocument27 pagesAre Constitutional State of Emergency Clauses Effective? An Empirical ExplorationVale SánchezNo ratings yet

- Democracy and Development-2Document20 pagesDemocracy and Development-2Ankita DuttaNo ratings yet

- Veiw From The Bottom BookDocument31 pagesVeiw From The Bottom BookcamNo ratings yet

- S10 StilesDocument19 pagesS10 StilesJeyson Stiven Bernal MontalvoNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Separation of Powers in The Global South and Global NorthDocument28 pagesThe Evolution of The Separation of Powers in The Global South and Global NorthMaryann MainaNo ratings yet

- Building Institutional Legitimacy The Role of Procedural JusticeDocument23 pagesBuilding Institutional Legitimacy The Role of Procedural JusticeNedimFerizovićNo ratings yet

- Between Power and Principle An IntegrateDocument69 pagesBetween Power and Principle An IntegrateBabar Khan100% (1)

- Game Theory Cooperation ComplianceDocument32 pagesGame Theory Cooperation ComplianceRamonAndradeNo ratings yet

- What Is DiscriminationDocument25 pagesWhat Is Discriminationmeghasarsambe2001No ratings yet

- To Divide and Not Conquer: Preventing Partisan Gerrymandering with Independent Nonpartisan CommissionsFrom EverandTo Divide and Not Conquer: Preventing Partisan Gerrymandering with Independent Nonpartisan CommissionsNo ratings yet

- The Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S.From EverandThe Litigation State: Public Regulation and Private Lawsuits in the U.S.No ratings yet

- Chapter TwoDocument1 pageChapter TwoSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Notes: Preface To The Second EditionDocument1 pageNotes: Preface To The Second EditionSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- And Cyberspace (New York: M&T Books, 1996), 63-81, Though More Interesting Variations OnDocument1 pageAnd Cyberspace (New York: M&T Books, 1996), 63-81, Though More Interesting Variations OnSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter FourDocument1 pageChapter FourSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Journal of Science and Technology Law 7 (2001) : 288, 299.: Chapter FiveDocument1 pageJournal of Science and Technology Law 7 (2001) : 288, 299.: Chapter FiveSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter ThreeDocument1 pageChapter ThreeSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- And Privacy in Cyberspace: The Online Protests Over Lotus Marketplace and The Clipper ChipDocument1 pageAnd Privacy in Cyberspace: The Online Protests Over Lotus Marketplace and The Clipper ChipSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- And Electronic Commerce (Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1998), XVDocument1 pageAnd Electronic Commerce (Boston: Kluwer Law International, 1998), XVSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Chapter SevenDocument1 pageChapter SevenSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Nities in Cyberspace, Edited by Marc A. Smith and Peter Kollock (London: Routledge, 1999), 109Document1 pageNities in Cyberspace, Edited by Marc A. Smith and Peter Kollock (London: Routledge, 1999), 109Sandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Science and Technology Law Review 1 (2000) : 2Document1 pageScience and Technology Law Review 1 (2000) : 2Sandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- The United States: Constitutional Law, Edited by Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (WashDocument1 pageThe United States: Constitutional Law, Edited by Philip B. Kurland and Gerhard Casper (WashSandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

- The Judiciary and American Democracy, Kenneth D. Ward and Cecilia R. Castillo, Eds. (AlbanyDocument1 pageThe Judiciary and American Democracy, Kenneth D. Ward and Cecilia R. Castillo, Eds. (AlbanySandra RodriguezNo ratings yet

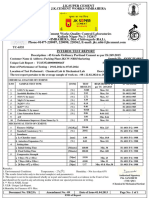

- Opc JK Super MTC (4) 25.02.2024Document1 pageOpc JK Super MTC (4) 25.02.2024msconstu2No ratings yet

- Numerical DifferentiationDocument26 pagesNumerical DifferentiationchibenNo ratings yet

- Malta Dair Products LTDDocument5 pagesMalta Dair Products LTDGabriella CauchiNo ratings yet

- Free TradeStation EasyLanguage TutorialsDocument15 pagesFree TradeStation EasyLanguage TutorialszzzebrabNo ratings yet

- II yr/III Sem/Mech/EEE 2 Marks With Answers Unit-VDocument5 pagesII yr/III Sem/Mech/EEE 2 Marks With Answers Unit-VanunilaNo ratings yet

- Estate of W. R. Olsen, Deceased, Kenneth M. Owen and First National Bank of Minneapolis, Co-Executors, and Hazel D. Olsen v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 302 F.2d 671, 1st Cir. (1962)Document6 pagesEstate of W. R. Olsen, Deceased, Kenneth M. Owen and First National Bank of Minneapolis, Co-Executors, and Hazel D. Olsen v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 302 F.2d 671, 1st Cir. (1962)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robotic Aid For Commando OperationDocument23 pagesRobotic Aid For Commando OperationShafi PulikkalNo ratings yet

- (MIÑOZA - Wen Roniel Badayos) - PKYF 2023 Application EssayDocument3 pages(MIÑOZA - Wen Roniel Badayos) - PKYF 2023 Application EssayWen MinozaNo ratings yet

- Ethical Issues and Role Duality in InsidDocument17 pagesEthical Issues and Role Duality in InsidJayson MolejonNo ratings yet

- KSKV SVM ElektrikDocument1 pageKSKV SVM ElektrikSiti Meryam Ahmad ZakiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3Document44 pagesLecture 3Quynh Trang DinhNo ratings yet

- JD1ADocument3 pagesJD1AKEYURKUMAR100% (4)

- Digital Electronics: Course Description and ObjectivesDocument3 pagesDigital Electronics: Course Description and ObjectivesMaxNo ratings yet

- BSBINS603 Student Assessment TasksDocument26 pagesBSBINS603 Student Assessment Taskssukhim44nNo ratings yet

- Caso 2 - Gerencia de Operaciones 2023Document3 pagesCaso 2 - Gerencia de Operaciones 2023Eyner PeñaNo ratings yet

- Jpghrsghrb-905 (PWHT Procedure, Asme) Rev.0 - PDF - Scribd: Jpghr..Document3 pagesJpghrsghrb-905 (PWHT Procedure, Asme) Rev.0 - PDF - Scribd: Jpghr..king 1983No ratings yet

- Fundamental Design Principles and Their Impact On Digital DesignsDocument14 pagesFundamental Design Principles and Their Impact On Digital DesignsCARLOS, EPHRAIM O.No ratings yet

- Tingkat Stres Dan Kualitas Tidur Mahasiswa: Keywords: Level of Stress, Stress Management, Sleep QualityDocument6 pagesTingkat Stres Dan Kualitas Tidur Mahasiswa: Keywords: Level of Stress, Stress Management, Sleep QualityJemmy KherisnaNo ratings yet

- Critically Analyse The Recruitment and Selection Process That An Organisation Should Adopt in Today's Business Context - Nitish Roy PertaubDocument4 pagesCritically Analyse The Recruitment and Selection Process That An Organisation Should Adopt in Today's Business Context - Nitish Roy Pertaubayushsoodye01No ratings yet

- A Spam Transformer Model For SMS Spam DetectionDocument11 pagesA Spam Transformer Model For SMS Spam Detectionsireesha payyavulaNo ratings yet

- HEC HMS Tech ManualDocument170 pagesHEC HMS Tech ManualRahmi Diah AdhityaNo ratings yet

- MobileApp Checklist 2017Document21 pagesMobileApp Checklist 2017Trico AndreasNo ratings yet

- Eng Cressi Manu 03842Document7 pagesEng Cressi Manu 03842Marin PintarNo ratings yet

- Seminar ReportDocument29 pagesSeminar ReportUrja DhabardeNo ratings yet

- Bin Card Coc Level 4Document19 pagesBin Card Coc Level 4Kaleb Tilahun100% (4)

- Dahua DVR 5104C/5408C/5116C Especificaciones: M Odel DH-DVR5104C-V2 DH-DVR5108C DH-DVR5116C SystemDocument1 pageDahua DVR 5104C/5408C/5116C Especificaciones: M Odel DH-DVR5104C-V2 DH-DVR5108C DH-DVR5116C Systemomar mejiaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Disinterested PersonDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Disinterested PersonDexter John SuyatNo ratings yet