Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Uploaded by

Georgiana BlagociCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Official Guide PTE Academic PDFDocument249 pagesThe Official Guide PTE Academic PDFboosbochy67% (18)

- Skillful 4 Listening and Speaking Teacher's Book Unit 4Document7 pagesSkillful 4 Listening and Speaking Teacher's Book Unit 4Cristiano Hung40% (5)

- Introduction - Macro SkillsDocument14 pagesIntroduction - Macro SkillsChermie Sarmiento77% (75)

- Personal Health Record - Template For AdultsDocument16 pagesPersonal Health Record - Template For AdultsGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Lecture 14 Phraseological Units in EnglishDocument56 pagesLecture 14 Phraseological Units in EnglishSorin TelpizNo ratings yet

- Conditional Sentences in English and TurkishDocument9 pagesConditional Sentences in English and Turkishsuper_sumoNo ratings yet

- Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List: English For Specific Purposes December 2008Document18 pagesEstablishment of A Medical Academic Word List: English For Specific Purposes December 2008Anh NhamNo ratings yet

- A Corpus-Driven Food Science and Technology Academic Word ListDocument27 pagesA Corpus-Driven Food Science and Technology Academic Word ListMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly (June 2007)Document210 pagesTESOL Quarterly (June 2007)dghufferNo ratings yet

- J Esp 2014 05 003Document12 pagesJ Esp 2014 05 003赵文No ratings yet

- Coxhead 2000 2001 A New Academic WordlistDocument27 pagesCoxhead 2000 2001 A New Academic WordlistSamantha BasterfieldNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadDocument26 pagesA New Academic Word List: Averil Coxheadjorge IvanNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadDocument26 pagesA New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadWienwien WienaNo ratings yet

- Academic Words in Education Research Artic 2014 Procedia Social and BehaviDocument7 pagesAcademic Words in Education Research Artic 2014 Procedia Social and BehaviNoFree PahrizalNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Vocabulary ListDocument23 pagesA New Academic Vocabulary ListDan Bar Tre100% (1)

- The Development of Science Academic Word ListDocument11 pagesThe Development of Science Academic Word Lists0790095293sNo ratings yet

- Academic Word ListDocument8 pagesAcademic Word ListArfan Ismail100% (1)

- Coxhead 2000 A New Academic Word ListDocument27 pagesCoxhead 2000 A New Academic Word Listkayta2012100% (1)

- English For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuDocument12 pagesEnglish For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- English For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuDocument12 pagesEnglish For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- Academic VocabularyDocument14 pagesAcademic VocabularyNozima ANo ratings yet

- J Esp 2016 08 003Document9 pagesJ Esp 2016 08 003赵文No ratings yet

- Teaching Lexical Bundles in The Disciplines: An Example From A Writing Intensive History ClassDocument16 pagesTeaching Lexical Bundles in The Disciplines: An Example From A Writing Intensive History ClassJuanito ArosNo ratings yet

- Definitions in Theology Lectures: Implications For Vocabulary LearningDocument17 pagesDefinitions in Theology Lectures: Implications For Vocabulary LearningEwa SoNo ratings yet

- Vlach and Ellis, 2010 - An Academic Formulas List New Methods in Phraseology ResearchDocument27 pagesVlach and Ellis, 2010 - An Academic Formulas List New Methods in Phraseology ResearchLarissa GoulartNo ratings yet

- A Basic Engineering Word ListDocument13 pagesA Basic Engineering Word ListWirun CherngchawanoNo ratings yet

- 2022 O'FlynnDocument28 pages2022 O'FlynnHurmet FatimaNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Project Word ListDocument76 pagesVocabulary Project Word Listabdulsahib100% (1)

- A New Academic Vocabulary List: Dee Gardner and Mark DaviesDocument24 pagesA New Academic Vocabulary List: Dee Gardner and Mark DaviesRama AterNo ratings yet

- ESP VocabularyDocument5 pagesESP Vocabularychahinez bouguerraNo ratings yet

- Gardner, D., & Davies, M. (2014) - A New Academic Vocabulary List. Applied Linguistics, 35 (3), 305-327.Document23 pagesGardner, D., & Davies, M. (2014) - A New Academic Vocabulary List. Applied Linguistics, 35 (3), 305-327.Marko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- Gardner, D., & Davies, M. (2014) - A New Academic Vocabulary List. Applied Linguistics, 35 (3), 305-327.Document23 pagesGardner, D., & Davies, M. (2014) - A New Academic Vocabulary List. Applied Linguistics, 35 (3), 305-327.Marko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- P. Durrant 2009 - Investigating The ViabDocument13 pagesP. Durrant 2009 - Investigating The ViabIrman FatoniiNo ratings yet

- A Phrasal ListDocument22 pagesA Phrasal ListRoy Altur RobinsonNo ratings yet

- Ackermannand Chen 2013 Developing Academic Collocation List AuthorsmanuscriptDocument31 pagesAckermannand Chen 2013 Developing Academic Collocation List AuthorsmanuscriptaridNo ratings yet

- The Academic Vocabulary List (Gardner and Davies, 2014)Document23 pagesThe Academic Vocabulary List (Gardner and Davies, 2014)tuyettran.eddNo ratings yet

- Academic Vocab ESL Student PapersDocument19 pagesAcademic Vocab ESL Student Paperswacwic wydadNo ratings yet

- The Role of Vocabulary in ESP Teaching and Learning: Wu Jiangwen & Wang Binbin Guangdong College of FinanceDocument15 pagesThe Role of Vocabulary in ESP Teaching and Learning: Wu Jiangwen & Wang Binbin Guangdong College of FinanceChie IbayNo ratings yet

- A Corpus-Based Study On The Use of MAKE by Turkish EFL LearnersDocument8 pagesA Corpus-Based Study On The Use of MAKE by Turkish EFL LearnersBeste TöreNo ratings yet

- English Learners' DictionariesDocument12 pagesEnglish Learners' DictionariesM Saddam HossainNo ratings yet

- The Development of Academic Vocabulary For Undergraduate Students in Writing An Undergraduate Thesis A Corpus-Based AnalysisDocument6 pagesThe Development of Academic Vocabulary For Undergraduate Students in Writing An Undergraduate Thesis A Corpus-Based AnalysisInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Assessing Second Language Vocabulary KnowledgeDocument9 pagesAssessing Second Language Vocabulary KnowledgebarkhaNo ratings yet

- Word Lists For Vocabulary LearningDocument18 pagesWord Lists For Vocabulary LearningynottripNo ratings yet

- AsiaTEFL V10 N4 Winter 2013 An Exploration of Lexical Bundles in Academic Lectures Examples From Hard and Soft Sciences PDFDocument29 pagesAsiaTEFL V10 N4 Winter 2013 An Exploration of Lexical Bundles in Academic Lectures Examples From Hard and Soft Sciences PDFDanica JerotijevicNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Size 1Document10 pagesVocabulary Size 1Gaycel Mariño RectoNo ratings yet

- A Phrasal Expressions List: Ron Martinez and Norbert SchmittDocument22 pagesA Phrasal Expressions List: Ron Martinez and Norbert SchmittZulaikha ZulkifliNo ratings yet

- The Most Frequently Used Spoken American English IdiomsDocument31 pagesThe Most Frequently Used Spoken American English Idioms7YfvnJSWuNo ratings yet

- (H) 2022 - Akira Iwata - The Effectiveness of Extensive Reading (ER) On The Development of EFL Learners' Sight Vocabulary Size and Reading FluencyDocument18 pages(H) 2022 - Akira Iwata - The Effectiveness of Extensive Reading (ER) On The Development of EFL Learners' Sight Vocabulary Size and Reading FluencyDanell MinhNo ratings yet

- Reading Materials For Learning TOEIC Vocabulary Based On Corpus DataDocument17 pagesReading Materials For Learning TOEIC Vocabulary Based On Corpus Datarachelle_baltazarNo ratings yet

- Chen - 2012 - Dictionary Use and Vocabulary Learning in The Context of ReadingDocument32 pagesChen - 2012 - Dictionary Use and Vocabulary Learning in The Context of Reading5d7bmfffvjNo ratings yet

- ESL Reading Textbooks vs. University Textbooks Are We Giving Our Students The Input They May Need 2011 MillerDocument15 pagesESL Reading Textbooks vs. University Textbooks Are We Giving Our Students The Input They May Need 2011 Millerdeheza77No ratings yet

- 11.structural Analysis of Lexical Bundles Across Two Types of English News Papers Edited by Native and Non-NatDocument20 pages11.structural Analysis of Lexical Bundles Across Two Types of English News Papers Edited by Native and Non-Natstella1986No ratings yet

- Phraseological Examination Using Key Phrase FrameDocument20 pagesPhraseological Examination Using Key Phrase FramelindaNo ratings yet

- Michael West's General List Comparison With Yemeni Crescent Book WordsDocument40 pagesMichael West's General List Comparison With Yemeni Crescent Book WordsRed RedNo ratings yet

- 58 R3 BaumannGraves2010Document21 pages58 R3 BaumannGraves2010Kainat BatoolNo ratings yet

- Journal of English For Academic Purposes: Ana Frankenberg-GarciaDocument12 pagesJournal of English For Academic Purposes: Ana Frankenberg-GarciaLê Hoàng PhươngNo ratings yet

- Second Language Vocabulary Assessment - Read - 2007Document21 pagesSecond Language Vocabulary Assessment - Read - 2007ho huongNo ratings yet

- EJ1247208Document12 pagesEJ1247208Vishal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Revising and Validating The 2000 Word Level and The University Word Level Vocabulary TestsDocument33 pagesRevising and Validating The 2000 Word Level and The University Word Level Vocabulary Testsho huongNo ratings yet

- Schmitt & Schmitt (2012) A Reassessment of Frequency and Vocabulary Size in L2 Vocabulary TeachingDocument21 pagesSchmitt & Schmitt (2012) A Reassessment of Frequency and Vocabulary Size in L2 Vocabulary TeachingEdward FungNo ratings yet

- Kazemi 2014Document6 pagesKazemi 2014Mhilal ŞahanNo ratings yet

- V.vo JSLW CorpusDocument13 pagesV.vo JSLW CorpusThomasNguyễnNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument31 pages10 - Chapter 2 PDFVioly Fulgencio Mateo GuianedNo ratings yet

- The Most Frequent Collocations in Spoken EnglishDocument10 pagesThe Most Frequent Collocations in Spoken EnglishRubens RibeiroNo ratings yet

- 3M Oral Care Impression Procedure GuideDocument123 pages3M Oral Care Impression Procedure GuideGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Two Different Bonding Materials For Orthodontic Retention TreatmentDocument22 pagesEvaluation of Two Different Bonding Materials For Orthodontic Retention TreatmentGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Mandibular Expansion AppliancesDocument9 pagesMandibular Expansion AppliancesGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Handout Elmex 1Document1 pageHandout Elmex 1Georgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Methods of Data Collection in Qualitative Research: Interviews and Focus GroupsDocument6 pagesMethods of Data Collection in Qualitative Research: Interviews and Focus GroupsGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Paradigm Shift in The Treatment of Class-II Malocclusions in Children and AdolescentsDocument31 pagesParadigm Shift in The Treatment of Class-II Malocclusions in Children and AdolescentsGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Errors in Survey Research and Their Threat To Validity and ReliabilityDocument9 pagesErrors in Survey Research and Their Threat To Validity and ReliabilityGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Clinical Manifestation, DiagnosisDocument13 pagesClinical Manifestation, DiagnosisGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Lista SindroameDocument1 pageLista SindroameGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic DisordersDocument38 pagesSchizophrenia and Other Psychotic DisordersGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Winter2016microscopes PDFDocument8 pagesWinter2016microscopes PDFGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Filament End-Rounding Quality in Electric ToothbrushesDocument4 pagesFilament End-Rounding Quality in Electric ToothbrushesGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- An IV 2013-2014Document16 pagesAn IV 2013-2014Georgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Schizophrenia:Courseoverthe Lifetime: Philipd - Harvey MichaeldavidsonDocument16 pagesSchizophrenia:Courseoverthe Lifetime: Philipd - Harvey MichaeldavidsonGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Types of Texts in Science in GeneralDocument1 pageTypes of Texts in Science in GeneralGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Study Skills HandoutDocument2 pagesStudy Skills HandoutGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Reading For Study Purposes RTP Read The Problem PQRST Preview, Question, Read, SQ3R Survey, Question, Read, PERU Preview, Enquire, Read, UseDocument1 pageReading For Study Purposes RTP Read The Problem PQRST Preview, Question, Read, SQ3R Survey, Question, Read, PERU Preview, Enquire, Read, UseGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Wulff, 2004, The Language of Medicine (Paper)Document2 pagesWulff, 2004, The Language of Medicine (Paper)Georgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- The ProblemDocument59 pagesThe ProblemPunong Grande NHS Banga NHS Annex (R XII - South Cotabato)No ratings yet

- PurComm - Unit 1 Lesson 2Document4 pagesPurComm - Unit 1 Lesson 2SUMAYYAH MANALAONo ratings yet

- Reading SkillsDocument25 pagesReading SkillsDaffodilsNo ratings yet

- English For Logistics: Essential Vocabulary To Get The Job Done Right - FluentU Business English Blo PDFDocument18 pagesEnglish For Logistics: Essential Vocabulary To Get The Job Done Right - FluentU Business English Blo PDFAndrew PerishNo ratings yet

- Revised - 2022-2023 - French - Language, BGEC 109-Detailed Course OutlineDocument7 pagesRevised - 2022-2023 - French - Language, BGEC 109-Detailed Course OutlineEwurah AbhenaNo ratings yet

- SIOP Components Menu-1Document3 pagesSIOP Components Menu-1Erick CastilloNo ratings yet

- Giáo án Tiếng Anh 7 kì 1 - 5512Document156 pagesGiáo án Tiếng Anh 7 kì 1 - 5512Alice TranNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 Lesson 5-8Document12 pagesUnit 7 Lesson 5-8Nguyen Lan PhuongNo ratings yet

- MTBW 1Document7 pagesMTBW 1ANGELA ABENANo ratings yet

- Unit 11: Shopping: Practice The VocabularyDocument6 pagesUnit 11: Shopping: Practice The VocabularyArney TorresNo ratings yet

- Cambridge IGCSE: GERMAN 0525/03Document32 pagesCambridge IGCSE: GERMAN 0525/03kalman.valkovszkyNo ratings yet

- Trọn Bộ Tài Liệu IELTS Từ 0 - 7.5+Document6 pagesTrọn Bộ Tài Liệu IELTS Từ 0 - 7.5+Nguyễn Văn NhớNo ratings yet

- Ant and Grasshopper: Text SummaryDocument109 pagesAnt and Grasshopper: Text Summarybigbencollege2930No ratings yet

- English 365-3 ContentsDocument4 pagesEnglish 365-3 Contentstatianaspb19750% (2)

- Clinton,.et - Al 2018 PDFDocument39 pagesClinton,.et - Al 2018 PDFHema BalasubramaniamNo ratings yet

- 5 Ways To Improve Your EnglishDocument8 pages5 Ways To Improve Your EnglishMaksymilianNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 1 RPPDocument10 pagesLesson Plan 1 RPPfatillah putri QamariaNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Log WorksheetDocument7 pagesVocabulary Log WorksheetFanvian Chen XWNo ratings yet

- Kelas XII Cause EffectDocument4 pagesKelas XII Cause EffectSandi Maulana SA50% (8)

- Latihan Inisiasi 3: State Whether The Underlined Word(s) Is (Are), ,, ,, ,,, orDocument3 pagesLatihan Inisiasi 3: State Whether The Underlined Word(s) Is (Are), ,, ,, ,,, orAdam RizkyNo ratings yet

- Grammar Translation Method GTM Versus CommunicativDocument5 pagesGrammar Translation Method GTM Versus CommunicativKaiffNo ratings yet

- Cambridge O Level: Bengali 3204/01 May/June 2021Document7 pagesCambridge O Level: Bengali 3204/01 May/June 2021nayna sharminNo ratings yet

- Online Games For Primary School Vocabulary TeachinDocument10 pagesOnline Games For Primary School Vocabulary Teachinmdz marliniNo ratings yet

- Pasted Dev'tal ReadingDocument29 pagesPasted Dev'tal ReadingMarie Joy GarmingNo ratings yet

- Auld Lang SyneDocument1 pageAuld Lang SyneAnnie Rose SencioNo ratings yet

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Uploaded by

Georgiana BlagociOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Wang, Liang, Ge, 2008, Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List (Paper)

Uploaded by

Georgiana BlagociCopyright:

Available Formats

Available online at www.sciencedirect.

com

English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

ENGLISH FOR

SPECIFIC

PURPOSES

www.elsevier.com/locate/esp

Establishment of a Medical Academic Word Listq

Jing Wang, Shao-lan Liang, Guang-chun Ge *

Department of Foreign Languages, Fourth Military Medical University, Xian, China

Abstract

This paper reports a corpus-based lexical study of the most frequently used medical academic

vocabulary in medical research articles (RAs). A Medical Academic Word List (MAWL), a word

list of the most frequently used medical academic words in medical RAs, was compiled from a corpus containing 1 093 011 running words of medical RAs from online resources. The established

MAWL contains 623 word families, which accounts for 12.24% of the tokens in the medical RAs

under study. The high word frequency and the wide text coverage of medical academic vocabulary

throughout medical RAs conrm that medical academic vocabulary plays an important role in medical RAs. The MAWL established in this study may serve as a guide for instructors in curriculum

preparation, especially in designing course-books of medical academic vocabulary, and for medical

English learners in setting their vocabulary learning goals of reasonable size during a particular

phase of English language learning.

2008 The American University. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The acquisition of vocabulary has long been considered to be a crucial component of

learning a language (Coady, Magoto, Hubbard, Graney, & Mokhtari, 1993; Nation,

2001) because the breadth and depth of a students vocabulary will have a direct inuence

upon the descriptiveness, accuracy and quality of his or her writing (Read, 1998). Nagy

(1988) also claimed that vocabulary is a major prerequisite and causative factor in comprehension. The dramatically large number of English words, however, is a learning goal far

q

*

The article is co-authored equally.

Corresponding author. Tel.: +86 29 8477 4475; fax: +86 29 8323 4516.

E-mail address: guangcge@fmmu.edu.cn (G.-c. Ge).

0889-4906/$34.00 2008 The American University. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.esp.2008.05.003

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

443

beyond the reaches of second language learners and even beyond the reaches of most

native speakers.

Fortunately, all words are not equally important in dierent stages of learning. Nations

(2001) division of vocabulary into four levels high frequency words, academic vocabulary, technical vocabulary and low frequency words indicates that some words deserve

more attention and eort than others in dierent phases of language learning or for dierent purposes. According to Nation and Waring (1997), it is generally agreed that the

beginners of English learning should focus on the rst 2000 most frequently occurring

word families of English in the General Service List (GSL) (West, 1953), while for intermediate or advanced learners who usually study English for academic purposes, the command of these GSL words may no longer be their major concern and the priority of their

vocabulary acquisition may be shifted to lower frequency vocabulary. In academic settings, ESP students do not see these technical terms as a problem because these terms

are usually the focus of the discussion in the classroom or are glossed in the textbook

(Strevens, 1973). The vocabulary that ESP students have most diculty with is known,

in ESP jargon, as non-subject-specic semi-technical vocabulary or academic vocabulary

(Li & Pemberton, 1994; Shaw, 1991; Thurstun & Candlin, 1998).

1.1. Academic vocabulary

Academic vocabulary, which is also called sub-technical vocabulary (Cowan, 1974) or

semi-technical vocabulary (Farrell, 1990), is viewed as formal, context-independent

words with a high frequency and/or wide range of occurrence across scientic disciplines,

not usually found in basic general English courses; words with high frequency across scientic disciplines (Farrell, 1990, p. 11). The high frequency occurrence of academic words

in academic text has been conrmed by some researchers. Sutarsyah, Nation, and Kennedy (1994) reported that academic vocabulary accounted for 8.4% of the tokens in the

Learned and Scientic sections of the LOB and Wellington corpora, and for 8.7% of

the tokens in economics texts. Coxhead (2000) reported that the academic vocabulary

in her Academic Word List covered 10% of the tokens in her 3 500 000 running word academic corpus. Santos research (2000) revealed that roughly 16% of the words in his textbook samples across dierent disciplines were academic words. This high coverage of

academic words in the academic texts has far exceeded the 5% ratio of the unknown to

the known comprehension threshold suggested by Laufer (1988), who has pointed out that

a learner has to know 95% of the words in a text to ensure reasonable comprehension of

the text because the ratio of unknown to known words over 5% is not sucient to allow

reasonably successful guessing of the meaning of the unknown words. In addition, Kuehn

(1996) observed that knowledge of academic words dierentiated academically well-prepared from under-prepared college students from all backgrounds. The ndings from these

studies clearly indicate that EAP learners, without sucient knowledge of academic

vocabulary, cannot deal eectively with reading materials for various types of academic

tasks they are supposed to fulll (Laufer & Nation, 1999). However, procient use of academic vocabulary is one of the most challenging tasks in ESP students word expansion.

Anderson and Freebody (1981) found that academic words were the words most often

identied as unknown by her students in academic texts. Based on his study, Farrell

(1990) reported that the lack of knowledge was partly the result of the assumption of some

444

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

subject teachers that their students knew these words and as a result they seldom taught

these words explicitly.

1.2. Previous studies on academic vocabulary list development

Previous studies on academic vocabulary have produced some very helpful academic

word lists. Quite a number of these academic word lists focused on the academic vocabulary

occurring across dierent disciplines. By analyzing 301 800 words in textbooks and lectures

published in journals covering 19 academic disciplines, Campion and Elley (1971) developed a word list containing 500 most common words and 3200 frequently used words.

The items in their list represented the vocabulary that students were likely to encounter

in their university studies. Praninskas (1972) compiled the American University Word list,

which was based on a corpus of 272 466 words from 10 university-level textbooks covering

10 academic disciplines. Lynns (1973) and Ghadessys (1979) word lists were drawn up by

counting the words for which foreign students wrote annotations in their university textbooks and the words that the students had found dicult during their reading. Xue and

Nation (1984) combined the four earlier-compiled word lists (Campion and Elleys, Praninskass, Lynns, and Ghadessys) into the University Word List (UWL), consisting of

about 800 words that were not in the rst 2000 words of the GSL but that were of high frequency and of wide range in academic texts. Xue and Nations purpose of setting up the

UWL was to create a list of high frequency words for learners with academic purposes,

so that these words can be taught and directly studied in the same way as the words from

the GSL. More recently, Coxhead (2000) developed the Academic Word List (AWL), using

a corpus of 3.5 million running words, plus Rangethe software which could calculate how

often a word occurred (its frequency) and in how many dierent texts in the corpus it

occurred (its range). The texts in her corpus were selected from dierent academic journals

and university textbooks in four main areas: arts, commerce, law and natural science. The

AWL contains 570 word families that account for approximately 10% of the total words in

her selected academic texts. Compared with the UWL, the AWL contains fewer word families but provides more text coverage and more consistent word selection criteria. AWL now

is a widely cited academic word list across a broad range of disciplines.

In addition to these discipline-crossing academic word lists, some researchers have

focused on the academic vocabulary used in a single discipline. They assumed that there

might be some unique features in the academic vocabulary across sub-disciplines of one

discipline. Lam (2001) conducted an empirical study of academic vocabulary of Computer

Science in order to nd the vocabulary problems encountered by the computer science students in reading academic texts. She noted that academic vocabulary was semantically distinct from the same vocabulary when it appeared in general texts. She suggested that such

lexical terms should be presented as a glossary of academic vocabulary with information

of frequency of occurrences based on a specialized corpus. Mudraya (2006) established the

Student Engineering English Corpus (SEEC), containing nearly 2 000 000 running words

selected from engineering textbooks in 13 engineering disciplines and produced an academic word list of 1200 word families for engineering students. The word families in

her word list are frequently encountered in engineering textbooks compulsory for all engineering students, regardless of their elds of specialization. She argued that academic

vocabulary should be given more attention in the ESP classroom.

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

445

Despite the academic vocabulary lists across dierent disciplines compiled respectively

by some researchers, there were few detailed studies exclusively on medical academic

vocabulary used in the eld of medicine. Baker (1988) analyzed three rhetorical items in

medical journal articles and she concluded that rhetorical items were in the category of

academic vocabulary and that identifying academic items had some pedagogical implications. Chen and Ge (2007) analyzed the occurrence and distribution of the AWL word

families in medical RAs. Their ndings conrmed that the academic vocabulary had a

high text coverage and dispersion throughout a medical research article and served some

important rhetorical functions, but they argued that the AWL was far from complete in

representing the frequently used medical academic vocabulary in medical RAs and called

for eorts in establishing a medical academic word list.

The study reported in this paper was designed to develop a Medical Academic Word

List (MAWL) of the most frequently used medical academic vocabulary across dierent

sub-disciplines in medical science. We hope the MAWL established in this study may serve

as a guide for medical English instructors in curriculum preparation, especially in designing course-books of medical academic vocabulary, and for medical English learners in setting their vocabulary learning goals of reasonable size during a particular phase of English

language learning.

2. Methodology

2.1. Corpus establishment

We established as the database for our study a written specialized corpus containing

1 093 011 running words from 288 written texts of a single genremedical research articles, because reading and writing medical RAs is the fundamental concern for most learners/users of English for Medical Purposes (EMP).

2.1.1. Data collection

All the written medical RAs to be adopted in the corpus were downloaded from the

database ScienceDirect Online (http://www.sciencedirect.com), the worlds largest electronic collection of science, technology and medicine with full text and bibliographic information, accessed at the library of the Fourth Military Medical University (FMMU). The

database ScienceDirect Online contains over 1800 journals, including almost every top title

across 24 disciplines from natural science to social science, and is considered to be one of

the most authoritative and representative databases.

In the discipline of Medicine and Dentistry of ScienceDirect Online, there were 32 subject areas at the time of our study, covering almost all the elds of medical science. The

samples in the corpus were chosen from the following 32 subject areas.

1.

2.

3.

Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine

Cardiology and Cardiovascular

Medicine

Clinical Neurology

Line missing

17. Medicine and Dentistry

18. Nephrology

19. Obstetrics, Gynecology and Womens

Health

446

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

Complementary and Alternative

Medicine

Critical Care and Intensive Care

Medicine

Dentistry, Oral Surgery and

Medicine

Dermatology

Emergency Medicine

Endocrinology, Diabetes and

Metabolism

Forensic Medicine

Gastroenterology

Health Informatics

Hematology

Hepatology

Immunology, Allergology and

Rheumatology

Infectious Diseases

20. Oncology

21. Ophthalmology

22. Orthopedics, Sports Medicine and

Rehabilitation

23. Otorhinolaryngology and Facial Plastic

Surgery

24. Pathology and Medical Technology

25. Perinatology, Pediatrics and Child

Health

26. Psychiatry and Mental Health

27. Public Health and Health Policy

28. Pulmonary and Respiratory Medicine

29. Radiology and Imaging

30. Surgery

31. Transplantation

32. Urology

All the sample medical RAs included in the corpus were kept at their original length,

written in the internationally conventionalized IMRD (IntroductionMethodResultDiscussion) structure, published in the years 20002006 and written by native English speaking writers by Woods (2001) strict criteria (rst authors had to have names native to the

country concerned and also be aliated with an institution in countries where this language is spoken as the rst language).

A three-round selection was conducted in choosing the sample medical RAs for the corpus. In the rst round, we took each of the 32 subject areas as one stratum and then by

stratied random sampling we selected 3 journals from each of the 32 subject areas/stratum, totaling 96 journals. In the second round, we randomly selected one issue out of each

of the 96 journals obtained in the rst round. From the 96 selected issues, the articles

which were not following the IMRD format, were not written by native English speaking

writers or were shorter than 2000 running words or longer than 12 000, running words

were eliminated. In the third round, we selected 3 criteria-fullling articles from each of

the 96 issues by simple random sampling. After this three-round selection, 288 texts were

chosen for the corpus, the shortest one containing 2923 running words and the longest one

containing 10 901 running words (4939 on average).

2.1.2. Data processing

In this study, data processing incorporated the standardization of the medical RAs to

be stored in the corpus and the normalization of the words in the to-be-stored RAs. For

the standardization of the medical RAs included in the corpus, the charts, diagrams, bibliographies and some components in texts, which were not able to be processed by computer analyzing programs or should not be included in the lexical analysis in the chosen

medical RAs, were removed so as to eliminate the factors unrelated to the lexical analysis

and to ensure that the texts stored in the corpus be readable by the computer software. The

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

447

normalization of words was fullled automatically by the computer software. The computer software would read all inections or derivations of a word as its basic form and

would count the range and frequency of them as one word family. For example, induce,

induced, induces, inducing and induction would be counted as one word by the computer

software. Word family, as dened by Bauer and Nation (1993), is the base word plus its

inected forms and transparent derivations, including all closely related axed forms as

well as the stems most frequent, productive and regular prexes, suxes and perceived

transparency. According to Coxhead (2000, p. 218), comprehending regularly inected

or derived members of a family does not require much more eort by learners if they know

the base word and if they have control of basic word-building processes, which may

account for the general adoption of the word family in many word lists. After the standardization of the sample texts and normalization of words, the words in the corpus were

counted and sorted automatically by computer.

2.2. List development

2.2.1. Word selection criteria

The three principles (specialized occurrence, range and frequency of a word family)

used by Coxhead in developing the AWL were adopted in our study with some adjustment. In her study, Coxhead named wide-range word families as the word families whose

members occur in at least half of the 28 subject areas in her corpus. In this study, we also

set 50% as the criterion for inclusion. The members of a word family to be included in the

MAWL should occur in 16 subject areas, half of the 32 subject areas in our corpus. The

least frequency of the members of a word family to be included in the MAWL was 30

times, a third of Coxheads 100 times, for the number of the running words (1 000 000)

in our corpus was only about one third of that (3 500 000) in Coxheads corpus.

Coxhead (2000) also reported that in her AWL word selection, range was the rst criterion and frequency the second because a word count based mainly on the frequency

would have been biased by longer texts and topic-related words. This principle was also

applied in the present study. Only word families covering 16 subject areas or more would

be included in the MAWL, while word families occurring with very high frequency but

covering fewer than 16 subject areas would be excluded.

In sum, all the nally included word families in the MAWL met the following word

selection criteria:

1. Specialized occurrence: The word families included had to be outside the rst 2000 most

frequently occurring words of English, as represented by Wests GSL (1953).

2. Range: Members of a word family had to occur at least in 16 or more of the 32 subject

areas.

3. Frequency: Members of a word family had to occur at least 30 times in the corpus of

medical research articles.

As is known, the division between technical vocabulary and academic/sub-technical

vocabulary is not always distinct (Chung & Nation, 2003; Mudraya, 2006). In some cases,

arbitrary decisions need to be made to distinguish technical vocabulary and academic/subtechnical vocabulary. In compiling the MAWL, two experienced professors of English for

Medical Purposes from our department were consulted whenever any arbitrary decision

448

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

was needed in the inclusion or the elimination of some criteria-fullling controversial word

families in or from the computer-screened-out candidate list.

2.2.2. MAWL development

Following the standardization of the medical RAs and the normalization of the words,

the frequency and the range of the word families in the corpus were counted and listed by

computer software. The word selection criteria were then applied to locate our target word

families to be included in the MAWL. The word families included in the GSL were eliminated rst and then from the remaining word families, the word families occurring at least

in 16 or more of the 32 subject areas were selected. From the screened-out word families,

only those that occurred at least 30 times in the corpus of medical research articles were

selected for the candidate word list. If there was any uncertainty about any of the criteria-fullling word families in the computer-screened-out candidate list, two experienced

English professors who have taught and conducted studies on English for Medical Purposes for more than 20 years were consulted, as mentioned above, and they made the decision on whether the word families in question should be included in or excluded from the

nalized word list. The nalized list was termed as the Medical Academic Word List

(MAWL).

3. Results

There were 1 093 011 running words, 31 275 word families and 4128 pages of text in the

corpus. Totally 3345 word families were found to have occurred P30 times (frequency).

After the elimination of the GSL word families (1899 word families), 1446 word families

were left and 650 (44.95%) word families of them occurred in 16 or more subject areas

under study (range). By consulting the two experienced professors of English for Medical

Purposes, 27 (4.15%) borderline word families out of the 650 word families in the computer-screened candidate list were eliminated by expert opinion. Table 1 displays the 27

word families which were eliminated by expert opinion.

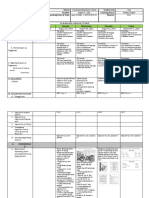

Table 1

Twenty-seven word families eliminated by expert opinion

Number

Headword

Frequency

Range

Number

Headword

Frequency

Range

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

pathogenesis

cytokine

epithelial

mitochondrial

carcinoma

ligand

situ

lymphoid

vitro

pulmonary

posterior

anterior

lysis

cardia

146

119

115

110

80

79

68

68

65

65

63

63

60

56

22

18

17

16

16

17

16

16

17

16

18

18

16

18

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

necrosis

cutaneous

stent

vivo

hepatic

aortic

ischemia

cerebral

dorsal

hemorrhage

pathophysiology

exogenous

phenotypic

55

55

52

52

51

50

50

49

46

44

44

39

33

16

16

16

17

19

18

17

17

16

18

17

16

16

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

449

By our word selection criteria plus the expert opinion of our consulted experienced

EMP professors, 623 (95.85% of 650) word families were ultimately chosen and formed

the Medical Academic Word List (see Appendix), which appeared 133 746 times totally.

In the MAWL, the most frequently used word was cell, which appeared 4421 times and

appeared in all the 32 subject areas in the corpus, while the least frequently used one

was static, which appeared 30 times and appeared in 20 subject areas in the corpus. Table

2 shows the statistical results of the top 30 most frequently used word families in the

MAWL.

The word families in the MAWL occurred in a wide range of the subject areas in our

corpus. Of the 623 word families in the list, 104 (16.69%) covered all the 32 subject areas

and 321 (51.52%) covered 25 or more subject areas (see Table 3). Totally, 486 word families (78.01%) in the MAWL occurred in 20 or more of the 32 subject areas under study.

Taking the list as a whole, the frequency and the range of the word families included in the

MAWL were positively correlated (rs = 0.753, p = 0.000). Among the top 100 most frequently used word families in the list, 54 (54%) appeared in all the 32 subject areas and

Table 2

Statistical results of the top 30 word families of the MAWL

Headword

Frequency

Range

Occurrence

Occurrence

cell

data

muscular

signicant

clinic

analyze

respond

factor

method

protein

tissue

dose

gene

previous

demonstrate

normal

process

similar

concentrate

function

therapy

indicate

area

obtain

research

vary

activate

require

induce

cancer

4421

2226

2049

2039

1598

1447

1427

1237

1209

1122

1097

1035

999

926

861

819

819

810

787

756

749

745

734

705

704

695

673

669

668

667

3.31

1.66

1.53

1.52

1.19

1.08

1.07

0.92

0.90

0.84

0.82

0.77

0.75

0.69

0.64

0.61

0.61

0.61

0.59

0.57

0.56

0.56

0.55

0.53

0.53

0.52

0.50

0.50

0.50

0.50

32

32

23

32

32

32

32

32

32

28

29

26

28

32

32

32

32

32

27

32

29

32

32

32

32

32

31

32

30

22

100.00

100.00

71.88

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

87.50

90.63

81.25

87.50

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

84.38

100.00

90.63

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

100.00

96.88

100.00

93.75

68.75

450

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

Table 3

Subject-area coverage of word families in MAWL

Subject areas covered

Number of word families

32

31

30

29

28

27

26

25

24

23

22

21

20

19

18

17

16

104

31

30

37

32

27

29

31

38

22

32

35

38

29

40

35

33

%

16.69

4.98

4.82

5.94

5.14

4.33

4.65

4.98

6.10

3.53

5.13

5.62

6.10

4.65

6.42

5.62

5.30

Total

623

100.00

90 (90%) appeared in 25 or more subject areas, while among the bottom 100 word families

in the list, only 1 (1%) covered 32 subject areas and 42 (42%) covered fewer than 20 subject

areas.

The average text coverage of the MAWL was 12.24% of the total words in the medical

RAs under study. The following passage randomly selected from a medical research article

(Supp & Boyce, 2005) in our corpus gave us a picture of the academic words used in such

texts. The words included in the MAWL are underlined.

Chronic wounds represent a dierent kind of challenge for wound healing. These

wounds do not usually involve a large surface area, but they have a high incidence

in the general population and thus have enormous medical and economic impacts.

The most common chronic wounds include pressure ulcers and leg ulcers. In the United States alone, these wounds are estimated to aect more than 2 million people

with total clinical treatment costs as high as $1 billion annually. Pressure ulcers,

characterized by tissue ischemia and necrosis, are common among patients in

long-term care settings, but patients hospitalized for short-term care settings are also

at risk if mobility is impaired. Leg ulcers can have a variety of etiologies. Venous

ulcers are the most common, often resulting from dysfunction of valves in veins of

the lower leg that normally prevent the backow of venous blood. Venous congestion leads to leakage of blood and macromolecules into the dermis, which can act

as physical barriers to diusion of oxygen and nutrients from the vasculature into

the skin. Arterial insuciency and diabetes also contribute to the development of

leg ulcers. Arterial blockage can lead to tissue ischemia, inducing ulcers or necrosis.

The patients with diabetes are prone to leg ulcers because of several aspects of their

disease, including neuropathy, poor circulation, and reduced response to infection.

Diabetic foot ulcers can lead to complications that result in as many as 50,000 amputations annually in the United States, accounting for 4570% of all lower-extremity

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

451

amputations performed. Historically, treatment of the relatively small chronic

wounds has included the use of topical agents and occlusive dressings, and grafting

of split- or full-thickness skin. Skin grafts can provide timely wound coverage, but

may lead to painful donor sites which are slow to heal and may be unsuccessful

because of underlying deciencies in wound healing (p. 403).

Among the 305 words in the above passage, 37 belonged to the MAWL. The MAWL

text coverage in the passage was 12.13%, which was consistent with the results of our

study.

We have included only 623 base words of the word families in the MAWL, even though

derivative forms are sometimes more frequent than the base forms, because in most cases

learning the derived form requires very little extra work once the base form is known and if

learners have control of basic word-building processes (Xue & Nation, 1984). In the

Appendix, the words in the MAWL are listed according to the frequency of their occurrence in the corpus in a descending order, that is, the more frequently used word families

are listed prior to those appearing less frequently in the corpus. This frequency priority in

listing illustrates the relative usefulness of these words in medical English, which is one of

the major objectives of the present study.

Only 342 (54.90%) of the 623 word families in the MAWL overlapped with the 570

word families in the AWL. The marked dierence between the MAWL and the AWL

argues for itself that dierent practices and discourses of disciplinary communities require

a more restricted discipline-based lexical repertoire, which undermines the usefulness of

general academic word lists across dierent disciplines. Words like lesion and vein, though

they tend to be considered as technical terms by people outside medical eld, are included

in the MAWL as medical academic vocabulary because they are general purpose medical

words frequently used across dierent medical subject disciplines. Academic vocabulary or

semi-technical vocabulary is a class of words between technical and non-technical words

and usually with technical as well as non-technical implications. The word families

included in the MAWL are medical academic vocabulary common across various sub-disciplines of medicine but not within one single sub-discipline of medicine.

4. The pedagogical implications

The MAWL can serve as reference for a Medical English lexical syllabus. As the frequently and widely used medical academic vocabulary in medical RAs, the word families

in the MAWL are worth special attention in designing some English for Medical Purposes

(EMP) courses. The MAWL can provide some guidelines concerning vocabulary in curriculum preparation, particularly in designing EMP course-books for learning medical academic vocabulary and in selecting relevant teaching/learning materials. The MAWL can

help learners/instructors center on essential medical academic words, providing learners

with some more specic approach to learning medical academic vocabulary and facilitating instructors setting of their medical academic vocabulary teaching goals in dierent

stages. Well-timed and repeated exposure to the word families of the MAWL in a variety

of contexts may signicantly contribute to the acquisition of the deep-going properties of

this important set of medical academic words.

The MAWL can also help learners study EMP academic vocabulary in a more conscious and manageable way. The MAWL provides a clear and direct access to the most

452

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

frequently used medical vocabulary for EMP learners and enables them to conduct explicit

learning of vocabulary when these words are rst introduced to the learners. With more

exposure to medical texts, the learners will consolidate the vocabulary knowledge acquired

from the MAWL. This pattern of learning academic vocabulary in medical context may

also exemplify a compromise for a long-running debate about explicit learning versus

guessing from context.

5. Conclusion

The MAWL, a medical academic word list based on a Medical RAs Corpus with

1 093 011 running words, has been compiled for the better learning and application of medical academic words in the discipline of medicine. Although a number of word lists of academic words in other disciplines have been reported, our MAWL has been so far the only

list of academic words targeted exclusively on medical science. By developing a list of the

frequently used medical academic words in medicine, we hope to inspire enough attention

of instructors and learners/users to this type of vocabulary. It would be of special significance for EMP students/instructors and medical professionals in learning or using medical academic vocabulary in medical reading and writing.

Our research is only a preliminary study on the medical academic vocabulary used in

medical RAs. If possible, the MAWL needs to be rechecked in larger corpora or in other

genres of medicine, such as medical textbooks or spoken medical academic English. We

hope the availability of exercises and tests based on the MAWL will promote eective

and ecient teaching and learning of medical academic vocabulary.

Appendix

Medical Academic Word List (submitted by frequency of word families)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

cell

data

muscular

signicant

clinic

analyze

respond

factor

method

protein

tissue

dose

gene

previous

demonstrate

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

normal

process

similar

concentrate

function

therapy

indicate

area

obtain

research

vary

activate

require

induce

cancer

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

occur

role

evident

range

identify

period

outcome

phase

specic

liver

infect

culture

mediate

score

aect

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

453

Appendix (continued)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

potential

individual

expose

involve

survive

target

respective

intervene

site

per

design

primary

approach

estimate

component

acid

baseline

procedure

overall

pathway

inammation

region

participate

lesion

technique

volume

serum

dene

evaluate

prior

assay

injury

section

task

achieve

symptom

detect

molecular

error

incubate

donor

intense

chronic

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

fraction

insulin

contrast

react

source

available

disorder

positive

structure

multiple

generate

conclude

medium

inhibit

complex

distribute

major

tumor

initial

channel

receptor

membrane

stress

strain

nuclear

ratio

approximate

release

transplant

surgery

assess

impact

versus

drug

laboratory

minimize

onset

reveal

scan

monitor

criterion

visual

duration

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

Headword

cycle

investigate

acute

sequence

select

maximize

whereas

peak

elevation

image

enzyme

parameter

isolate

mutation

enhance

calcium

glucose

appropriate

incidence

conduct

protocol

background

stimulate

algorithm

establish

ecacy

hypothesis

feature

interval

mortality

array

derive

series

buer

specimen

focus

display

plasma

abstract

grade

secondary

strategy

(continued on next page)

454

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

Appendix (continued)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

graft

undergo

peripheral

transcription

despite

consist

status

furthermore

immune

reverse

infuse

author

interact

issue

negative

throughout

goal

vein

chamber

independent

proliferation

formation

subsequent

predict

correspond

correlate

regulate

exclude

metabolic

device

recruit

nal

impair

inject

percent

publish

remove

syndrome

exhibit

blot

defect

biopsy

index

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

diameter

cognitive

followup

uid

lipid

magnetic

margin

energy

locate

survey

software

prole

attribute

convention

synthesis

recover

objective

lter

segment

compound

link

guideline

extract

proportion

regression

questionnaire

discharge

respiratory

gender

summary

promote

tract

toxic

relevant

episode

acquire

communicate

internal

dimension

layer

microscope

adverse

recipient

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

density

virus

interpret

document

instruct

oral

theory

illustrate

probe

diagnose

consequence

version

create

dilute

skeletal

novel

threshold

technology

element

dynamic

challenge

typical

transfer

aspect

diet

cohort

external

vector

antibiotic

domain

temporary

linear

plus

digit

accurate

concept

transport

rotate

input

absorb

replicate

distinct

radical

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

455

Appendix (continued)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

superior

contact

ensure

stable

prevalence

capture

degrade

anesthesia

optimal

kit

bias

proximal

constant

incorporate

sucient

sustain

label

barrier

zone

chart

implement

trauma

fund

context

hence

community

lateral

facilitate

trim

prolong

quantify

perception

accumulate

expert

grant

amplication

random

construct

mount

renal

environment

couple

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

laser

magnitude

formula

decit

alter

access

supplement

eliminate

graph

shift

capacity

qualitative

simulate

globe

modulate

output

attenuate

statistic

prescribe

dierentiate

equivalent

orient

practitioner

substantial

chemical

thereby

consent

intake

stance

trend

overnight

contribute

enable

spectrum

assign

option

implicate

aid

tag

portion

electron

cope

decline

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

Headword

species

unique

overlap

adjacent

node

transform

modify

manual

colleague

core

entry

decient

cascade

benet

identical

parallel

migrate

reagent

exceed

comprise

highlight

evolution

schedule

organism

predominant

cumulative

purchase

plot

seek

emerge

anity

valid

code

sterile

compute

prospect

utilize

deposit

column

contract

scar

axis

(continued on next page)

456

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

Appendix (continued)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

451

452

453

454

455

456

457

458

459

460

461

462

463

464

465

466

467

468

469

470

471

472

473

inferior

deviate

trigger

loop

precursor

perceive

preliminary

undertake

substitute

whilst

scenario

adapt

adult

expand

cord

fundamental

feedback

sum

elicit

circulation

tolerance

team

sex

candidate

assume

imply

terminal

vascular

hormone

minor

panel

aggressive

comprehensive

residual

perspective

brief

trace

equip

accelerate

template

mode

diminish

consecutive

foundation

474

475

476

477

478

479

480

481

482

483

484

485

486

487

488

489

490

491

492

493

494

495

496

497

498

499

500

501

502

503

504

505

506

507

508

509

510

511

512

513

514

515

516

517

emphasize

physiology

oxide

restore

conict

phenomenon

invade

restrict

attach

longitude

technical

nevertheless

append

inltrate

bacterium

agonist

rely

capable

manipulate

histology

pharmacology

saline

persist

integrity

precede

rear

mental

demographic

pathology

prominent

apparatus

paradigm

adjust

crucial

nervous

gradient

disrupt

encounter

nitrogen

format

robust

spontaneous

principal

transmit

518

519

520

521

522

523

524

525

526

527

528

529

530

531

532

533

534

535

536

537

538

539

540

541

542

543

544

545

546

547

548

549

550

551

552

553

554

555

556

557

558

559

560

561

audit

decade

compromise

cue

gland

assist

inner

intrinsic

consume

suppress

fragment

hypertension

placebo

dominant

text

susceptible

spinal

corporate

principle

relapse

numerical

resolve

mature

uniform

diverse

retain

abdominal

lane

vital

suspend

voluntary

diuse

rationale

simultaneous

transient

secrete

methanol

confer

constitute

accomplish

enroll

embryo

logistic

project

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

457

Appendix (continued)

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

Number

Headword

562

563

564

565

566

567

568

569

570

571

572

573

574

575

576

577

578

579

580

581

582

insight

compliance

emission

soluble

comment

oxygen

warrant

route

morbidity

widespread

alcohol

conjugate

acknowledge

alternative

manifest

cluster

notion

render

malignancy

resemble

obvious

583

584

585

586

587

588

589

590

591

592

593

594

595

596

597

598

599

600

601

602

603

antigen

concomitant

fusion

elucidate

consensus

le

biology

urban

verify

speculate

postulate

routine

somewhat

catheter

odd

discrete

converse

span

augment

depict

adequate

604

605

606

607

608

609

610

611

612

613

614

615

616

617

618

619

620

621

622

623

neutral

thereafter

annual

plastic

professional

recall

entity

precise

successive

contaminate

tone

integrate

confound

profound

tension

dramatic

blast

encompass

consult

static

References

Anderson, R. C., & Freebody, P. (1981). Vocabulary knowledge. In J. Guthrie (Ed.), Comprehension and

teaching: Research reviews (pp. 77117). Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Baker, M. (1988). Sub-technical vocabulary and the ESP teacher: An analysis of some rhetorical items in medical

journal articles. Reading in a Foreign Language, 4(2), 91105.

Bauer, L., & Nation, P. (1993). Word families. International Journal of Lexicography, 6(4), 253279.

Campion, M., & Elley, W. (1971). An academic vocabulary list. Wellington: New Zealand Council For

Educational Research.

Chen, Q., & Ge, G. C. (2007). A corpus-based lexical study on frequency and distribution of Coxheads AWL

word families in medical research articles. English for Specic Purposes, 26, 502514.

Chung, T. M., & Nation, P. (2003). Technical vocabulary in specialized texts. Reading in a Foreign Language,

15(2), 103116.

Coady, J., Magoto, J., Hubbard, P., Graney, J., & Mokhtari, K. (1993). High frequency vocabulary and reading

prociency in ESL readers. In T. Huckin, M. Haynes, & J. Coady (Eds.), Second language reading and

vocabulary acquisition (pp. 217228). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Cowan, J. R. (1974). Lexical and syntactic research for the design of EFL reading materials. TESOL Quarterly,

8(4), 389400.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 213238.

Farrell, P. (1990). A lexical analysis of the English of electronics and a study of semi-technical vocabulary (CLCS

Occasional Paper No. 25). Dublin: Trinity College (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED332551).

Ghadessy, P. (1979). Frequency counts, word lists, material preparation: A new approach. English Teaching

Forum, 17, 2427.

458

J. Wang et al. / English for Specic Purposes 27 (2008) 442458

Kuehn, P. (1996). Assessment of academic literacy skills: Preparing minority and limited English procient (LEP)

students for post-secondary education. Fresno, CA: California State University (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED415498).

Lam, J. (2001). A study of semi-technical vocabulary in computer science texts, with special reference to ESP

teaching and lexicography (Research reports, Vol. 3). Hong Kong: Language Centre, Hong Kong University

of Science and Technology.

Laufer, B. (1988). What percentage of lexis is necessary for comprehension? In C. Lauren & M. Norman (Eds.),

Special language: From humans to thinking machines (pp. 316323). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Laufer, B., & Nation, P. (1999). A vocabulary-size test of controlled productive ability. Language Testing, 16(1),

3351.

Li, L., & Pemberton, R. (1994). An investigation of students knowledge of academic and subtechnical

vocabulary. In L. Flowerdew & A. K. K. Tong (Eds.), Entering text (pp. 183196). Hong Kong: The Hong

Kong University of Science and Technology.

Lynn, R. W. (1973). Preparing word lists a suggested method. RELC Journal, 4(1), 2532.

Mudraya, O. (2006). Engineering English: A lexical frequency instructional model. English for Specic Purposes,

25(2), 235256.

Nagy, W. (1988). Teaching vocabulary to improve reading comprehension. Newark, DE: International Reading

Association.

Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nation, P., & Waring, R. (1997). Vocabulary size, text coverage and word lists. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy

(Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 619). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Praninskas, J. (1972). American university word list. London: Longman.

Read, J. (1998). Validating a test to measure depth of vocabulary knowledge. In A. J. Kunnan (Ed.), Validation in

language assessment: Selected papers from the 17th language testing research colloquium (pp. 4160). Mahwah,

NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Shaw, P. (1991). Science research students composing processes. English for Specic Purposes, 10, 189206.

Santos, M. (2000). Analyzing academic vocabulary and contextual cue support in community college textbook.

Unpublished qualifying paper. Harvard: Harvard Graduate School of Education. <http://www.ncsall.net>

(Retrieved March 12, 2006, electronic version).

Strevens, P. (1973). Technical, technological, and scientic English. ELT Journal, 27, 223234.

Supp, D., & Boyce, S. (2005). Engineered skin substitutes: Practices and potentials. Clinics in Dermatology, 23(4),

403412.

Sutarsyah, C., Nation, P., & Kennedy, G. (1994). How useful is EAP vocabulary for ESP? A corpus based study.

RELC Journal, 25(2), 3450.

Thurstun, J., & Candlin, N. (1998). Concordancing and the teaching of the vocabulary of academic English.

English for Specic Purpose, 17(3), 267280.

West, M. (1953). A general service list of English words. London: Longman, Green & Co.

Wood, A. (2001). International scientic English: The language of research scientists around the world. In J.

Flowerdew & M. Peacock (Eds.), Research perspectives on English for academic purposes (pp. 7183).

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Xue, G., & Nation, P. (1984). A university word list. Language Learning and Communication, 3(2), 215219.

Wang Jing is an associate professor of English at the Department of Foreign Languages, Fourth Military Medical

University, China. She has taught courses in college English and published articles on academic reading and on

learning styles and communication strategies of Chinese learners.

Liang Shao-lan is an associate professor of English at the Department of Foreign Languages, Fourth Military

Medical University, China. She has published articles on learning strategies of Chinese English learners and on

genre analysis of English medical research articles.

Ge Guang-chun is a full professor of English and Chair at the Department of Foreign Languages, Fourth Military

Medical University, China. He has taught and published extensively in applied linguistics and ESP and EMP in

particular, where his areas of long-term interest include medical academic vocabulary, and genre and style

analysis of medical research articles.

You might also like

- The Official Guide PTE Academic PDFDocument249 pagesThe Official Guide PTE Academic PDFboosbochy67% (18)

- Skillful 4 Listening and Speaking Teacher's Book Unit 4Document7 pagesSkillful 4 Listening and Speaking Teacher's Book Unit 4Cristiano Hung40% (5)

- Introduction - Macro SkillsDocument14 pagesIntroduction - Macro SkillsChermie Sarmiento77% (75)

- Personal Health Record - Template For AdultsDocument16 pagesPersonal Health Record - Template For AdultsGeorgiana BlagociNo ratings yet

- Lecture 14 Phraseological Units in EnglishDocument56 pagesLecture 14 Phraseological Units in EnglishSorin TelpizNo ratings yet

- Conditional Sentences in English and TurkishDocument9 pagesConditional Sentences in English and Turkishsuper_sumoNo ratings yet

- Establishment of A Medical Academic Word List: English For Specific Purposes December 2008Document18 pagesEstablishment of A Medical Academic Word List: English For Specific Purposes December 2008Anh NhamNo ratings yet

- A Corpus-Driven Food Science and Technology Academic Word ListDocument27 pagesA Corpus-Driven Food Science and Technology Academic Word ListMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- TESOL Quarterly (June 2007)Document210 pagesTESOL Quarterly (June 2007)dghufferNo ratings yet

- J Esp 2014 05 003Document12 pagesJ Esp 2014 05 003赵文No ratings yet

- Coxhead 2000 2001 A New Academic WordlistDocument27 pagesCoxhead 2000 2001 A New Academic WordlistSamantha BasterfieldNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadDocument26 pagesA New Academic Word List: Averil Coxheadjorge IvanNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadDocument26 pagesA New Academic Word List: Averil CoxheadWienwien WienaNo ratings yet

- Academic Words in Education Research Artic 2014 Procedia Social and BehaviDocument7 pagesAcademic Words in Education Research Artic 2014 Procedia Social and BehaviNoFree PahrizalNo ratings yet

- A New Academic Vocabulary ListDocument23 pagesA New Academic Vocabulary ListDan Bar Tre100% (1)

- The Development of Science Academic Word ListDocument11 pagesThe Development of Science Academic Word Lists0790095293sNo ratings yet

- Academic Word ListDocument8 pagesAcademic Word ListArfan Ismail100% (1)

- Coxhead 2000 A New Academic Word ListDocument27 pagesCoxhead 2000 A New Academic Word Listkayta2012100% (1)

- English For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuDocument12 pagesEnglish For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- English For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuDocument12 pagesEnglish For Specific Purposes: Wenhua HsuMarko Tauses KarbaNo ratings yet

- Academic VocabularyDocument14 pagesAcademic VocabularyNozima ANo ratings yet

- J Esp 2016 08 003Document9 pagesJ Esp 2016 08 003赵文No ratings yet

- Teaching Lexical Bundles in The Disciplines: An Example From A Writing Intensive History ClassDocument16 pagesTeaching Lexical Bundles in The Disciplines: An Example From A Writing Intensive History ClassJuanito ArosNo ratings yet

- Definitions in Theology Lectures: Implications For Vocabulary LearningDocument17 pagesDefinitions in Theology Lectures: Implications For Vocabulary LearningEwa SoNo ratings yet

- Vlach and Ellis, 2010 - An Academic Formulas List New Methods in Phraseology ResearchDocument27 pagesVlach and Ellis, 2010 - An Academic Formulas List New Methods in Phraseology ResearchLarissa GoulartNo ratings yet