Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Uploaded by

Anonymous ID2ZO7Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5824)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- McDonald's Decision Making ProcessDocument5 pagesMcDonald's Decision Making ProcessSyed Adnan Shah75% (4)

- Solution Manual For Children A Chronological Approach 5th Canadian Edition Robert V Kail Theresa ZolnerDocument26 pagesSolution Manual For Children A Chronological Approach 5th Canadian Edition Robert V Kail Theresa ZolnerAngelKelleycfayo99% (92)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- DocxDocument5 pagesDocxYuyun Purwita SariNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bender Gestalt Visual Motor TestDocument41 pagesBender Gestalt Visual Motor TestJennifer CaussadeNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan Template Slippery FishDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Template Slippery Fishapi-550546162No ratings yet

- Allegory Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesAllegory Lesson Planapi-269729950No ratings yet

- Escultor - Non Nursing TheoriesDocument2 pagesEscultor - Non Nursing TheoriesDaniela Claire FranciscoNo ratings yet

- AIP Presentation DraftDocument26 pagesAIP Presentation DraftUmme AbeehaNo ratings yet

- Journal Critique GuidelinesDocument4 pagesJournal Critique GuidelinesNadia MoralesNo ratings yet

- SummativeDocument2 pagesSummativeZack Diaz100% (1)

- Employee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Investigation On The RelationshipDocument4 pagesEmployee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Investigation On The Relationshipvolvo HRNo ratings yet

- 40 Years of Design Research Cross2007Document4 pages40 Years of Design Research Cross2007EquipoDeInvestigaciónChacabucoNo ratings yet

- Research Learning StylesDocument21 pagesResearch Learning Stylesanon_843340593100% (1)

- Q7 - Post BureaucracyDocument2 pagesQ7 - Post BureaucracyJooYi OngNo ratings yet

- Family Law and Policy SpeechDocument4 pagesFamily Law and Policy Speechapi-539169687No ratings yet

- Hints On Writing - Jordan Peterson PDFDocument2 pagesHints On Writing - Jordan Peterson PDFSantiagoNo ratings yet

- Identi-T Stress Program QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesIdenti-T Stress Program QuestionnairepenguinlovecandyNo ratings yet

- Exploring Symbols Lesson 1 Class 3Document4 pagesExploring Symbols Lesson 1 Class 3api-535552931No ratings yet

- Theory of Translation ModulDocument120 pagesTheory of Translation ModulTri Indri YaniNo ratings yet

- A Review On Multidisciplinary Personality of Private and Government Academic StaffDocument16 pagesA Review On Multidisciplinary Personality of Private and Government Academic StaffInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Speak English: Fluently & ConfidentlyDocument12 pagesSpeak English: Fluently & ConfidentlyMBBS MBBS91% (11)

- Summary Experimental Psychology Chapter 1 Until 8 + 10: MlvkustersDocument53 pagesSummary Experimental Psychology Chapter 1 Until 8 + 10: MlvkustersAnonymous J2Ld5LM5lNo ratings yet

- Unit 7: Observation and Inference: ObjectivesDocument7 pagesUnit 7: Observation and Inference: ObjectivesmesaprietaNo ratings yet

- B2+ UNIT 3 CultureDocument2 pagesB2+ UNIT 3 CultureJuan Pablo Rincon100% (1)

- Training Evaluation Form TemplatesDocument2 pagesTraining Evaluation Form TemplatesahmadNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Chantal Smeekens, Margaret S. Stroebe, Georgios AbakoumkinDocument8 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Chantal Smeekens, Margaret S. Stroebe, Georgios AbakoumkinDoriana JdioreantuNo ratings yet

- Presentation and Facilitation Skills Module 1: WorkshopDocument6 pagesPresentation and Facilitation Skills Module 1: WorkshopnoorhidayahismailNo ratings yet

- Cartas de Blyenberg-Spinoza-Reason - Daniel SchneiderDocument18 pagesCartas de Blyenberg-Spinoza-Reason - Daniel SchneiderAntonio AlcoleaNo ratings yet

- Locus of ControlDocument3 pagesLocus of ControlAmisha MehtaNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument4 pages1 PDFKashyap Chintu100% (1)

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Uploaded by

Anonymous ID2ZO7Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Eveningness Is Associated With Higher Risk-Taking, Independent of Sex and Personality.

Uploaded by

Anonymous ID2ZO7Copyright:

Available Formats

Psychological Reports: Sociocultural Issues in Psychology

2014, 115, 3, 932-947. Psychological Reports 2014

EVENINGNESS IS ASSOCIATED WITH HIGHER RISK-TAKING,

INDEPENDENT OF SEX AND PERSONALITY1

DAVIDE PONZI, M. CLAIRE WILSON, AND DARIO MAESTRIPIERI

Institute for Mind and Biology, The University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois, USA

Summary.This study tested the hypotheses that eveningness is associated

with higher risk-taking propensities across dierent domains of risk and that this

association is not the result of sex dierences or confounding covariation with particular personality traits. Study participants were 172 men and women between 20

and 40 years of age. Surveys assessed chronotype, domain-specific risk-taking and

risk-perception, and Big Five personality dimensions. Eveningness was associated

with greater general risk-taking in the specific domains of financial, ethical, and

recreational decision making. Although risk-taking was associated with both risk

perception and some personality dimensions, eveningness predicted risk-taking independent of these factors. Higher risk-taking propensities among evening types

may be causally or functionally linked to their propensities for sensation- and novelty-seeking, impulsivity, and sexual promiscuity.

The source of inter-individual variation in risk-taking is a topic of

great interest to psychologists, economists, evolutionary biologists, and

other behavioral scientists (e.g., Figner & Weber, 2011). Whether or not individual dierences in the propensities to take risks are stable over time

and consistent across contexts, or they are temporally variable and domain-specific, however, has been debated for quite some time (e.g., Kowert

& Hermann, 1997; Weber, Blais, & Betz, 2002; Hanoch, Johnson, & Wilke,

2006; Figner & Weber, 2011). Historically, psychologists viewed risk-taking as a stable personality trait (e.g., Eysenck & Eysenck, 1977; Dahlback,

1990). Personality traits such as impulsivity and sensation seeking have

been associated with risk preferences in the context of drug abuse, smoking, unsafe sex, and extreme sports (Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000). Moreover, emphasis has been placed on consistency in risk-taking propensities across dierent contexts such as antisocial behaviors, gambling, and

sex (e.g., Mishra & Lalumiere, 2009; Mishra, Lalumiere, & Williams, 2010).

However, there is now a growing body of research documenting high intra-individual variability in risk preferences across dierent domains (e.g.,

MacCrimmon & Wehrung 1988; Weber, et al., 2002). People's risk preferences are also very sensitive to the framing of the context; e.g., if the outcome of a situation results in a loss or a gain, which makes people's prefer-

Address correspondence to Dario Maestripieri, Institute for Mind and Biology, The University of Chicago, 940 E. 57th Street, Chicago, IL 60637 or e-mail (dario@uchicago.edu).

1

DOI 10.2466/19.12.PR0.115c28z5

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 932

ISSN 0033-2941

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

933

ence for risk inconsistent (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) and leads to a view

of risk-taking more similar to a state than a trait construct.

Personality traits have been postulated to play an important role in

predicting both stability of risk preferences across domains and individual

dierences in domain specificity (e.g., Levenson, 1990; Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000; Lauriola & Levin, 2001; Nicholson, Soane, Fenton-O'Creevy,

& Willman, 2005). A study measuring Big Five personality traits showed

that extraversion and openness to experience were associated with overall greater risk propensity across six domains, but both traits failed to predict risk consistently in each domain (Nicholson, et al., 2005). In another

study, consistency of risk-aversion across three domains of everyday life

was found to be positively associated with agreeableness and conscientiousness but negatively with neuroticism (Soane & Chmiel, 2005). Personality dierences are also expected to influence the perception of risk

and the assessment of the costs and benefits (or rewards) associated with

risky decisions. For example, personality traits associated with emotionality play an important role in risk perception, while conscientiousness is

more important for the evaluation of the potential benefits (Weller & Tikir,

2011). Likewise, individual dierences in the perception of framing eects

during risky choices are mediated by individual dierences in personality

traits (Lauriola & Levin, 2001).

The influence of stable behavioral characteristics other than personality traits on general and domain-specific risk-taking remains, with a few

exceptions, largely uninvestigated. One type of stable behavioral characteristic that has recently been investigated in relation to risk taking is chronotype. Chronotype refers to inter-individual variation in sleep time preference such that some individuals prefer to wake up early in the morning

and go to sleep early in the evening while others prefer the opposite pattern (e.g., Adan, Archer, Hidalgo, Di Milia, Natale, & Randler, 2012). Sleep

preferences are generally distributed on a continuum in a population, with

unequivocal morning and evening types at the two extremes of the distribution; approximately 70% of the population is between these extremes,

exhibiting a weak sleep pattern bias or no bias at all (Adan, et al., 2012).

Although age and environmental factors (e.g., geographic and seasonal

variation, work schedule, etc.) can contribute significantly to variation in

sleep patterns (Roenneberg, Kuehnle, Pramstaller, Ricken, Havel, Guth, et

al., 2004; Leonhard & Randler, 2009; Natale, Adan, & Fabbri, 2009), interindividual variation in chronotype is generally stable over time and moderately heritable (h2 = .45; Hur & Lykken, 1998; Klei, Reitz, Miller, Wood,

Maendel, Gross, et al., 2005; Hur, 2007). Moreover, there are sex dierences

in chronotype, as men are more likely to be evening types than women

(Roenneberg, et al., 2004; Randler, 2007), although this dierence is relatively small and detected only with large samples (Randler, 2007).

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 933

15/12/14 8:51 AM

934

D. PONZI, ET AL.

Interest in the possible association between chronotype and risk-taking has been stimulated by observed dierences between morning and

evening types in various psychological and behavioral traits; specifically,

evening types have been reported to score higher than morning types in

extraversion (e.g., Matthews, 1988; Daz-Morales, 2007; Randler, Ebenhh,

Fischer, Hchel, Schro, Stoll, et al., 2012), novelty seeking (Caci, Robert,

& Boyer, 2004; Killgore, 2007), sensation seeking (Tonetti, Adan, Caci, De

Pascalis, Fabbri, & Natale, 2010), sexual promiscuity (Randler, et al., 2012),

and addictive behaviors such as alcohol or drug abuse (Prat & Adan,

2011). Consistent with expectations, two previous studies of chronotype

and general risk-taking have reported that evening types have higher propensities for risk-taking than morning types (Killgore, 2007; Maestripieri,

2014), while another study found a similar dierence in the specific domain of financial risk-taking but no dierences in other domains (Wang &

Chartrand, in press). These three studies, however, have some important

limitations.

Killgore (2007) examined dierent measures of risk-taking in a sample of 54 young adults (29 male, 25 female) that was subdivided by a median split into evening-type and morning-type groups based on self-reported sleep patterns and preferences. The evening-type group scored

higher than the morning-type group on the Brief Sensation-Seeking Scale

and in Total Risk-Taking Propensity (a cumulative Index obtained by

combining all the items in the Evaluation of Risks Scale), but there were

no dierences in performance on the behavioral Balloon Analogue Risk

Task (Killgore, 2007). Sex dierences in risk-taking and their possible confounding interaction with chronotype were not considered in this study.

Moreover, it was not clear how men and women were distributed into the

evening-type and morning-type groups. This is problematic because men

generally score higher than women in all measures of risk-taking (e.g., Byrnes, Miller, & Shafer, 1999; Figner & Weber, 2011). If men were over-represented in the evening-type group and under-represented in the morningtype group, then dierences in risk-taking in relation to sleep pattern may

have been confounded by sex.

Maestripieri (2014) reported that in a population of MBA students,

men scored higher than women in self-reported risk-taking, but eveningtype women scored as high as men and significantly higher than morningtype women. In this study, risk-taking was measured with a single selfreported item in which participants were asked to state, on a scale from

1 to 10, how willing or prepared they were to take risks in general, while

chronotype was assessed with a single-item self-identification as evening

type, morning type, or neither. In this study, there were no dierences in

risk-taking between evening- and morning-type men, but the number of

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 934

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

935

morning-type men in the sample was small (n = 21). Two additional limitations of this study were the particular nature of the sample (all MBA students with an unusual distribution of chronotypes) and the fact that the

analysis of risk-taking in relation to chronotype did not control for personality variables.

Wang and Chartrand (in press) investigated the relationship between

chronotype and risk preferences in six domains of life using the DomainSpecific Risk Taking Scale (DOSPERT; Weber, et al., 2002). They found that,

after controlling for age and sex, morningness was significantly correlated only with the financial domain of risky decision making, indicating that morning types are less likely to take financial risks. The negative

relationship between morningness and financial risk-taking was mediated by higher self-control in morning types, a finding that has been independently confirmed by another study (Milfont & Schwarzenthal, 2014).

However, one limitation of Wang and Chartrand's study is that they did

not control for the influence of personality, which may have confounded

their results (Tsaousis, 2010). Moreover, they did not control for individual

dierences in risk perception and did not report if risk perception in different domains was associated with chronotype.

In this study, the hypothesis that eveningness is associated with higher

risk-taking propensities was tested using an approach that addressed the

limitations of these previous studies. Chronotype was assessed with a

well-established scale, the reduced Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (rMEQ; Adan & Almirall, 1991), and included not only people who

were classified as evening or morning types, but also people who did not

fit into either group. Second, similar to Wang and Chartrand (in press),

the DOSPERT scale was used (Weber, et al., 2002), which allows for an assessment of both risk-taking and risk-perception across five dierent domains (ethical, financial, health-safety, recreational, and social). Third, the

Big Five Inventory (John, Donahue, & Kentle, 1991; Costa & McCrae, 1992)

was used to assess personality traits and the authors controlled for this

variable when examining the relationship between chronotype and risk

preferences.

METHOD

Participants

Study participants were 86 women and 86 men between 20 and 40

years of age (M = 28.8 yr., SD = 0.4). They were recruited through the Qualtrics Panels online survey system on the basis of specific selection criteria.

Additional criteria were possession of a high school diploma or a higher

degree, and being native English speakers. The online questionnaires were

designed so that the respondents could not skip any questions. Qualtrics

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 935

15/12/14 8:51 AM

936

D. PONZI, ET AL.

selects potential study participants from traditional, actively managed

market research panels; to ensure validity, the respondents' IP addresses

are verified, and their answers to the surveys are checked using digital fingerprint technology. Each sample from the panel base is proportioned to

the general population and then randomized before the survey is administered. Finally, Qualtrics does not disclose the nature of the study to the

potential participants at the time they are recruited. Participants (n = 110)

self-identified as Euro-American, 31 as Asian, 9 as Hispanic, 2 as Pacific Islanders, 10 as Native American, and 7 as of unidentified ethnicity; 3 failed

to report their ethnicity. Of the 172 participants, 88 were unmarried, 71

currently married, 5 divorced, 4 separated, and 1 widowed. This study

and the use of human subjects were approved by the Social Sciences Institutional Review Board of the University of Chicago.

Questionnaires

Morningness-eveningness.The reduced version of Horne and stberg's Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire (rMEQ; Adan & Almirall, 1991) is a validated 5-item questionnaire for chronotype assessment.

The items identify the participants' preferences in relation to sleeping and

waking time, the time of day when they experience maximal eciency,

their tiredness within half an hour of awakening, and their self-perceived

chronotype. Scores for the rMEQ range from 4 to 25. Scores below 12 identify participants as evening types and scores above 17 as morning types.

The psychometric properties of the rMEQ have recently been reviewed by

Di Milia, Adan, Natale, and Randler (2013), who concluded that this scale

has high reliability and produces results that are highly correlated with

those of the original MEQ and other commonly used scales.

Risk-taking.The Domain-Specific Risk-Taking Scale (DOSPERT;

Weber, et al., 2002) is a 30-item self-report questionnaire measuring participants' likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors/activities in 5 dierent

domains: ethical, financial, health/safety, recreational, and social. Each

item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1: Extremely Unlikely; 7: Extremely

Likely). A second section also provides information on how risky the participants perceive each behavior/activity to be (1: Not at all risky; 7: Extremely risky). In the present study, domain-specific risk-taking and riskperception were obtained by averaging the total score of risk-taking and

risk-perception items in each domain.

Personality.Personality was assessed using the Big Five Inventory

(BFI; John, et al., 1991), a 44-item questionnaire measuring personality

traits along five dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 936

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

937

Statistical Analyses

Exploratory analyses were conducted using chi-squared tests and Pearson's correlations. The influence of chronotype on risk-taking was investigated using hierarchical multiple regression analyses. These analyses involved three steps. In the first step, sex, age, and perceived risk for each

specific domain of risk were entered. In the second step, the Big Five personality was entered, and in the third step the continuous rMEQ score was

entered (see Mecacci & Rocchetti, 1998). In the model testing the eect of

chronotype on general risk-taking, general risk-taking and general risk perception were calculated as the average risk-taking and perception scores

across all the 30 DOSPERT items. All statistical analyses were performed

using SPSS 22. All tests are two-tailed and probabilities < .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Exploratory Analyses

Morning and evening types accounted for 13% and 17% of the sample, respectively, while 70% of the sample did not fit either pattern. There

were no significant sex dierences in chronotype (2 = 2.47, df = 2, p > .05;

Fig. 1) and no significant correlation between age and the total rMEQ

score (r = .03, p > .05). Finally, there was no significant association between

ethnicity and chronotype (2 = 5.39, df = 6, p > .05).

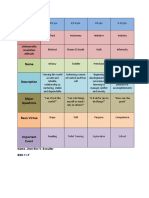

Table 1 presents the distribution of chronotype within each sex and

the mean ( SE) scores of risk-taking and risk-perception in the five risk

domains of the DOSPERT scale for male and female participants. Table 2

presents zero-order correlations between age, sex, chronotype, risk-taking,

and risk-perception scores in each of the five DOSPERT domains and in relation to the Big Five personality dimensions. There were no significant sex

dierences in any of the five domains of risk-taking (Wilks's lambda = 0.96,

F4, 167 = 1.34, p > .05) or risk-perception (Wilks's lambda = 0.98, F4, 167 = 0.55,

p > .05). There was no significant correlation between age and risk-taking

or risk-perception scores (Table 2), but there was a negative correlation between age and risk-taking in the ethical domain (r = .18, p < .05). Ethnicity

was not associated with risk-taking (Wilks's lambda = 0.81, F24, 555.89 = 1.39,

p > .05) or risk-perception (Wilks's lambda = 0.83, F24, 555.89 = 1.21, p > .05). The

risk-taking scores in the five domains were all positively correlated. However, risk-taking in the social domain showed low-to-medium size correlations with the other risk domains. Similar results were found for risk

perception. There were large eect size correlations between the ethical, financial, and recreational risk domains both for risk perception (R2 ranging

from .31 to .44) and for risk preference (R2 ranging from .33 to .47), while

the correlations between risk-taking and risk perception were all negative.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 937

15/12/14 8:51 AM

938

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 938

TABLE 1

DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS OF STUDY VARIABLES (M SE)

Chronotype

Early Morning

DOSPERT Scale

Neither

Night Owl

All

M (n = 15)

F (n = 8)

M (n = 57)

F (n = 62)

M (n = 14)

F (n = 16)

M (N = 86)

F (N = 86)

SE

SE

SE

SE

SE

SE

SE

SE

Risk-taking

2.61

0.27

1.95

.19

2.45

.18

2.30

.15

2.72

.43

3.59

.56

2.53

0.14

2.50

0.16

Financial

2.96

0.33

2.70

.39

3.02

.18

2.54

.14

3.32

.40

3.73

.54

3.06

0.14

2.78

0.15

Health/Safety

3.88

0.31

2.45

.33

3.26

.18

3.02

.17

3.72

.35

3.94

.46

3.45

0.14

3.14

0.16

Recreational

3.40

0.39

3.18

.52

3.36

.20

3.17

.17

4.11

.28

4.07

.50

3.49

0.16

1.34

0.16

Social

5.38

0.21

4.83

.30

4.72

.14

4.80

.12

4.89

.33

4.91

.40

4.86

0.11

4.82

0.11

Risk-perception

Ethical

4.78

0.27

4.70

.46

5.11

.15

5.13

.14

4.41

.37

5.46

.28

4.94

0.13

5.16

0.12

Financial

4.97

0.38

4.97

.47

5.04

.15

5.38

.14

4.72

.34

5.60

.25

4.98

0.13

5.38

0.12

Health/Safety

4.91

0.33

5.02

.47

5.03

.16

5.10

.14

4.39

.32

5.32

.25

4.91

0.13

5.13

0.12

Recreational

4.66

0.36

4.50

.57

4.65

.17

4.69

.13

4.36

.27

5.17

.28

4.61

0.13

4.76

0.12

Social

3.24

0.38

3.35

.31

3.36

.17

3.14

.13

2.95

.31

4.21

.34

3.27

0.14

3.36

0.12

Note.M = Males; F = Females.

D. PONZI, ET AL.

Ethical

15/12/14 8:51 AM

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 939

TABLE 2

ZERO-ORDER CORRELATIONS AMONG THE STUDY VARIABLES

1

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

1. Age

Variable

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

1.00

2. Sex

.10

.10

.05

.67

.60

.64

.03

.09

.01

.65

.56

.35 .12

4. Ethical

.05

.16*

.01

.47

.16* .33 .16*

5. Financial

.05

.09

.01

.22 .38 .27 .24

6. Health/Safety

.00

.06

.12

7. Recreational

.04

.03

.19* .32 .24 .19*

.00

.06

.12

.00

.17* .28 .16*

.09

.08

3. rMEQ

.37

.28

.69

.58

.60

.37

.25

.64

.58

.36

.33 .01

.22*

.07

.53 .39 .19*

.19* .35

.27

DOSPERT Risk-taking

.52

.22

.19*

.12

.47 .35 .19*

.00

.02

.13

9. Ethical

.18* .09

.09

.14

.09

.26 .20

.05

.10

.20

.02

.15*

.34

.10

.16* .10

11. Health/Safety

.09

.05

.09

.14

.40

.22**

.03

.16*

12. Recreational

.13

.01

.08

.42

.24

.01

.14

.01

.08

.02

.36

14. Extraversion

.06

.05

.09

.07

15. Agreeableness

.08

.09

.04

.17*

.20 .00

.04

.20

Big Five Inventory

16. Conscientiousness

17. Neuroticism

.20 .05

18. Openness to

experience

.02

.23

.36

.34 .27 .08

.51 .01

10. Financial

13. Social

.16* .28

.50 .27 .01

DOSPERT Risk-perception

.14

.01

.28 .16* .12

.03

.04

.15*

.35

.25

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

8. Social

.46 .51

.03

.15*

.20

.26

15/12/14 8:51 AM

939

Note.rMEQ = overall score; Male = 0. *p < .05. p < .01. p < .001.

940

D. PONZI, ET AL.

TABLE 3

HIERARCHICAL MULTIPLE REGRESSION ON THE ETHICAL, FINANCIAL, AND HEALTH/SAFETY

DOMAIN OF RISK

Variable

Ethical

Financial/Gambling

Health/Safety

Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Sex

0.01

0.07

0.05

0.01

0.02

0.00

0.07

0.04

0.05

Age

.15* 0.11

0.09

0.03

0.01

0.00

0.10

0.08

0.07

Perceived risk

.45 .26

.27

.51

.47

.47

.46

.44

.43

Big Five Inventory

Extraversion

0.09

0.07

Agreeableness

.26

.25

Conscientiousness

.34

.36

Neuroticism

Openness to

experience

.17*

0.12

.20

0.12

0.11

0.10

0.07

0.08

0.13

rMEQ

.22

.15*

.20

0.11

0.08

.22

.20*

0.09

.14*

.19

0.07

.21

0.05

0.05

0.12

0.12

.19

0.09

.49

.65

.69

.51

.60

.63

.49

.58

.58

R2adj

.22

.40

.45

.25

.34

.37

.22

.30

.31

.19

.05

.10

.03

.09

0.008

R2

Note.Regression coecients are presented as s. *p < .05. p < .01. p < .001.

Chronotype was not correlated with any personality traits, while weak

correlations were found between personality traits and risk preference

and perception.

Regression Analyses: Chronotype, Risk, and Personality

The results of hierarchical multiple regressions are shown in Table 3

and Table 4. Chronotype was negatively associated with overall risk-taking (R2adj = .33, R2 = .03, = 0.81, p < .01) and explained 3% of the overall variance in risk preference. All the personality measures were associated with overall risk preference, while there were no significant eects of

sex and age. The association between eveningness and greater risk-taking

propensities across the five risk domains was independent of the eects

of personality, sex, or age. In terms of domain-specific risk preferences,

chronotype was negatively associated with risk-taking in the domains of

ethical (R2adj = .45, R2 = .05, = .22, p < .001), financial (R2adj = .37, R2 = .03,

= 0.19, p < .01), and recreational risk (R2adj = .35, R2 = .03, = 0.81, p < .01),

but failed to explain a significant portion of variance in the health/safety

and social domains. The significant relationship between eveningness and

greater risk-taking in these three domains was above and beyond the effects of personality and of risk perception, which was negatively associated with risk-taking in all of the five risk domains. Conscientiousness

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 940

15/12/14 8:51 AM

941

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

TABLE 4

HIERARCHICAL MULTIPLE REGRESSION ON THE RECREATIONAL AND SOCIAL DOMAIN OF RISK

Variable

Recreational

Social

General

Step 1

Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 1 Step 2 Step 3

Sex

0.04

0.00

0.02

0.01

0.05

0.05

0.05

0.01

0.00

Age

0.13

0.12

0.11

0.00

0.01

0.00

0.13 0.09

0.08

.30

.30

Perceived risk

.34

.32

.31

.19*

.27 .20

.21

Big Five Inventory

Extraversion

Agreeableness

.33

.31

0.10

0.11

.22

.21

.21

.20

0.09

0.09

.27

.26

.16*

0.17

0.16

.28

.30

0.07

0.07

.15* 0.14

Conscientiousness

0.14

Neuroticism

0.12

Openness to

experience

.14*

rMEQ

0.11

.15*

.43

.18

.42

.19

0.05

.20

.18

.37

.59

.62

.19

.49

.49

.09

.34

.37

R2adj

.12

.32

.35

.02

.20

.20

.08

.31

.33

.21

.03**

.20

.00

.24

.03

R2

Note.Regression coecients are presented as s. *p < .05. p < .01. p < .001.

was the personality trait that most consistently predicted risk preferences

since it was negatively correlated with risk-taking in all but the social domain.

DISCUSSION

Both intra- and inter-individual variability were observed in self-reported risk preferences, and such variability seems to be independent of

age, sex, or ethnicity. Some study participants scored high on risk-taking in

some domains but low in others, while others were consistent in their risk

preferences across dierent domains. Although the study did not address

the sources of intra-individual variation in risk-taking, it has been suggested that variation in sensation seeking may explain why some people

are risk seekers in one domain, such as sports, but not in others (Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000). In terms of inter-individual variability in risk-taking, this study provides evidence that it can be accounted for by individual dierences in perception of risk and stable individual traits such as

personality (Johnson, Wilke, & Weber, 2004; Soane & Chmiel, 2005) and

chronotype (see also Wang & Chartrand, in press). Studies of personality

and risk preferences have been consistent in showing that people low in

neuroticism and high in agreeableness and conscientiousness tend to be

risk averse (e.g., Soane & Chmiel, 2005). Among the current study' par-

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 941

15/12/14 8:51 AM

942

D. PONZI, ET AL.

ticipants, overall risk-taking was negatively associated with risk perception, negatively associated with conscientiousness, and positively associated with extraversion and openness to experience (for similar findings,

see Nicholson, et al., 2005; Soane & Chmiel, 2005). Moreover, it is clear that

stable behavioral characteristics other than personality, such as chronotype, can account for a significant portion of inter-individual variation in

risk-taking.

The results supported the hypothesis that eveningness is associated

with a greater propensity for general risk-taking (see also Killgore, 2007;

Maestripieri, 2014). Study participants who scored higher in eveningness,

and regardless of their age, sex, ethnicity, or personality traits, had higher

overall risk-taking scores on the DOSPERT scale. Unlike previous studies

of chronotype and general risk-taking, the findings were obtained with a

non-student sample with a typical chronotype distribution and after controlling for the eects of confounding variables. Thus, the findings make a

novel and significant contribution to research on chronotype and general

risk-taking.

When dierent risk domains were analyzed separately, evening types

reported higher risk-taking than other individuals in the ethical, financial,

and recreational domains. Although the mechanisms underlying the association between eveningness and risk-taking in these domains remain

to be elucidated, it is likely that psychological processes such as sensation seeking, novelty seeking, impulsiveness, self-control, or disinhibition

and their biological substrates are involved (Caci, et al., 2004; Caci, Mattei, Bayale, Nadalet, Dossios, Robert, et al., 2005; Tonetti, et al., 2010; Muro,

Goma-i-Freixanet, & Adan, 2012; Milfont & Schwarzenthal, 2014; Wang &

Chartrand, in press). These processes are known to be strongly associated

with financial risk-taking and gambling (Wong & Carducci, 1991; Won

& Grant, 2001), risk-taking in sexual behavior (Donohew, Zimmerman,

Cupp, Novak, Colon, & Abell, 2000), and risk-taking in extreme sports

(Wagner & Houlihan, 1994; Monasterio, 2013). The associations between

eveningness, risk-taking, novelty seeking, sensation seeking, and impulsivity in ethical, financial, and recreational domains make functional sense

from an evolutionary perspective, as all these traits seem to be part of a

cluster of traits, which also includes sexual promiscuity and Dark Triad

personality (Randler, et al., 2012; Jonason, Jones, & Lyons, 2013), that reflects fast life history strategies (Figueredo, Vasquez, Brumbach, Sefcek,

Kirsner, & Jacobs, 2005; Ponzi, Henry, Kubicki, Nickels, Wilson, & Maestripieri, in press). Fast life history strategies are adaptations to stressful

or unpredictable environments, in which risk of adult mortality is high;

they involve rapid growth and sexual maturation, frequent reproduction

with multiple partners, and exploitative social styles with low investment

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 942

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

943

in long-term social relationships or child-rearing (Figueredo, et al., 2005).

The hypothesis that eveningness evolved as a fast life history adaptation

has already received some support (e.g., Randler, et al., 2012; Ponzi, et al.,

in press), and could be further supported by future studies showing that

the psychological and behavioral characteristics of evening types are designed to improve survival and reproduction in particular ecological and

social environments.

In the present study, chronotype was not associated with significant

variation in risk-taking in the health/safety and social domains. The reason for this negative result is not immediately clear. Social risk items seem

to equate risk with nonconformity (e.g., Admitting that your tastes are

dierent than those of a friend or Speaking your mind about an unpopular issue in a meeting at work), while most items in the other risk domains imply danger for one's safety/health (e.g., Going down a ski run,

i.e., beyond your ability) or breaking laws or moral codes (e.g., Passing o some else's work as your own). The weak correlation between

risk preferences in the social domain and in the other four domains suggests that risk-taking in the social domain may be regulated by dierent

biological and psychological mechanisms (e.g., Zuckerman & Kuhlman,

2000). The lack of a significant association between eveningness and risktaking in the health/safety domain replicates Wang and Chartrand's findings (in press). Similar to Wang and Chartrand's study, a positive association was found between eveningness and risk-taking in the financial

domain. However, while Wang and Chartrand did not control for the effects of personality traits, in the current study the domain-specific associations between chronotype and risk-taking were independent of personality. Therefore, this study makes a novel and significant contribution to

research on chronotype and domain-specific risk-taking.

However, there were some methodological limitations, including the

relatively narrow age range (20-40 years) of the participants and the small

sample size, which reduced the number of individuals at the two extremes

of the chronotype distribution. These limitations may have contributed

to the failure to replicate the previously reported sex dierences in chronotype (e.g., Randler, 2007) and the previously reported association between chronotype and personality (see Tsaousis, 2010, for a meta-analysis). No sex dierences in risk-taking were observed, which is at odds

with other studies that used the same scale to measure risk (Weber, et al.,

2002; Nicholson, et al., 2005; Stenstrom, Saad, Nepomuceno, & Mendenhall, 2011; Keynan & Bereby-Meyer, 2012; Wang & Chartrand, in press).

In these previous studies, men reported significantly more overall and

domain-specific risk-taking than women. However, all but Keynan and

Bereby-Meyer's (2012) study had larger sample sizes, and this may be part

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 943

15/12/14 8:51 AM

944

D. PONZI, ET AL.

of the reason for the discrepancy. Hopefully, the study will stimulate further research on the association between chronotype and risk-taking, and

such research will further elucidate both the mechanisms underlying this

association and their functional significance.

REFERENCES

ADAN, A., & ALMIRALL, H. (1991) Horne and stberg Morningness-Eveningness Questionnaire: a reduced scale. Personality and Individual Dierences, 12, 241-253.

ADAN, A., ARCHER, S. N., HIDALGO, M. P., DI MILIA, L., NATALE, V., & RANDLER, C. (2012)

Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiology International, 29, 11531175.

BYRNES, J. P., MILLER, D. C., & SCHAFER, W. D. (1999) Gender dierences in risk taking: a

meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 367.

CACI, H., MATTEI, V., BAYALE, F. J., NADALET, L., DOSSIOS, C., ROBERT, P., & BOYER, P. (2005)

Impulsivity but not venturesomeness is related to morningness. Psychiatry Research,

134, 259-265.

CACI, H., ROBERT, P., & BOYER, P. (2004) Novelty seekers and impulsive subjects are low

in morningness. European Psychiatry, 19, 79-84.

COSTA, P. T., & MCCRAE, R. R. (1992) Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and

Individual Dierences, 13, 653-665.

DAHLBACK, O. (1990) Personality and risk-taking. Personality and Individual Dierences,

12, 1235-1242.

DI MILIA, L., ADAN, A., NATALE, V., & RANDLER, C. (2013) Reviewing the psychometric

properties of contemporary circadian typology measures. Chronobiology International, 30, 1261-1271.

DAZ-MORALES, J. F. (2007) Morning and evening-types: exploring their personality

styles. Personality and Individual Dierences, 43, 769-778.

DONOHEW, L., ZIMMERMAN, R., CUPP, P. S., NOVAK, S., COLON, S., & ABELL, R. (2000) Sensation

seeking, impulsive decision making, and risky sex: implications for risk-taking

and design of interventions. Personality and Individual Dierences, 28, 1079-1091.

EYSENCK, S. B. G., & EYSENCK, H. J. (1977) The place of impulsiveness in a dimensional

system of personality description. British Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology,

16, 57-68.

FIGNER, B., & WEBER, E. U. (2011) Who takes risk when and why? Determinants of risktaking. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20, 211-216.

FIGUEREDO, A. J., VASQUEZ, G., BRUMBACH, B. H., SEFCEK, J. A., KIRSNER, B. R., & JACOBS, J.

(2005) The K-factor: individual dierences in life history strategies. Personality and

Individual Dierences, 39, 1349-1360.

HANOCH, Y., JOHNSON, J. G., & WILKE, A. (2006) Domain specificity in experimental measures and participant recruitment: an application to risk-taking behavior. Psychological Science, 17, 300-304.

HUR, Y. M. (2007) Stability of genetic influence on morningnesseveningness: a crosssectional examination of South Korean twins from preadolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Sleep Research, 16, 17-23.

HUR, Y. M., & LYKKEN, D. T. (1998) Genetic and environmental influence on morningnesseveningness. Personality and Individual Dierences, 25, 917-925.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 944

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

945

JOHN, O. P., DONAHUE, E. M., & KENTLE, R. L. (1991) The Big Five InventoryVersions 4a and

54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and

Social Research.

JOHNSON, G. J., WILKE, A., & WEBER, E. U. (2004) Beyond a trait view of risk-taking: a

domain-specific scale measuring risk perceptions, expected benefits, and perceived-risk attitudes in German-speaking populations. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 35, 153-163.

JONASON, P. K., JONES, A., & LYONS, M. (2013) Creatures of the night: chronotypes and the

Dark Triad traits. Personality and Individual Dierences, 55, 538-541.

KAHNEMAN, D., & TVERSKY, A. (1979) Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk.

Econometrica, 47, 263-291.

KEYNAN, R., & BEREBY-MEYER, Y. (2012) Leaving it to chancePassive risk taking in

everyday life. Judgment and Decision Making, 7, 705-715.

KILLGORE, W. D. S. (2007) Eects of sleep-deprivation and morningness-eveningness

traits on risk-taking. Psychological Reports, 100, 613-626.

KLEI, L., REITZ, P., MILLER, M., WOOD, J., MAENDEL, S., GROSS, D., WALDNER, T., EATON, J.,

MONK, T. H., & NIMGAONKAR, V. L. (2005) Heritability of morningness-eveningness

and self-report sleep measures in a family-based sample of 521 Hutterites. Chronobiology International, 22, 1041-1054.

KOWERT, P. A., & HERMANN, M. G. (1997) Who takes risks? Daring and caution in foreign

policy making. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 41, 611-637.

LAURIOLA, M., & LEVIN, I. P. (2001) Personality traits and risky decision-making in a

controlled experiment task: an exploratory study. Personality and Individual Differences, 31, 215-226.

LEONHARD, C., & RANDLER, C. (2009) In sync with the family: children and partners influence the sleep-wake circadian rhythm and social habits of women. Chronobiology

International, 26, 510-525.

LEVENSON, M. R. (1990) Risk taking and personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58, 1073-1080.

MACCRIMMON, K. R., & WEHRUNG, D. A. (1985) A portfolio of risk measures. Theory and

Decision, 19, 1-29.

MAESTRIPIERI, D. (2014) Night owl women are similar to men in their relationship orientation, risk-taking propensities, and cortisol levels: implications for the adaptive

significance and evolution of eveningness. Evolutionary Psychology, 12, 130-147.

MATTHEWS, G. (1988) Morningnesseveningness as a dimension of personality: trait,

state and psychophysiological correlates. European Journal of Personality, 2, 277293.

MECACCI, L., & ROCCHETTI, G. (1998) Morning and evening types: stress-related personality aspects. Personality and Individual Dierences, 25, 537-542.

MILFONT, T. L., & SCHWARZENTHAL, M. (2014) Explaining why larks are future-oriented

and owls are present-oriented: self-control mediates the chronotype-time perspective relationship. Chronobiology International, 31, 581-588.

MISHRA, S., & LALUMIERE, M. (2009) Is the crime drop of the 1990s in Canada and the USA

associated with a general decline in risky and health-related behavior? Social Sciences & Medicine, 68, 39-48.

MISHRA, S., LALUMIERE, M., & WILLIAMS, R. J. (2010) Gambling as a form of risk-taking:

individual dierences in personality, risk-accepting attitudes, and behavioral

preferences for risk. Personality and Individual Dierences, 49, 616-621.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 945

15/12/14 8:51 AM

946

D. PONZI, ET AL.

MONASTERIO, E. (2013) Personality characteristics in extreme sports athletes: morbidity and mortality in mountaineering and BASE jumping. In O. Mei-Dan & M. R.

Carmont (Eds.), Adventure and extreme sports injuries. Berlin, Germany: Springer.

Pp. 303-314.

MURO, A., GOMA-I-FREIXANET, M., & ADAN, A. (2012) Circadian typology and sensation

seeking in adolescents. Chronobiology International, 29, 1376-1382.

NATALE, V., ADAN, A., & FABBRI, M. (2009) Season of birth, gender, and social-cultural

eects on sleep timing preferences in humans. Sleep, 32, 423-426.

NICHOLSON, N., SOANE, E., FENTON-O'CREEVY, M., & WILLMAN, P. (2005) Personality and

domain-specific risk taking. Journal of Risk Research, 8, 157-176.

PONZI, D., HENRY, A., KUBICKI, K., NICKELS, N., WILSON, M. C., & MAESTRIPIERI, D. (in press)

The slow and fast life histories of early birds and night owls: their future- or present-orientation accounts for their sexually monogamous or promiscuous tendencies. Evolution & Human Behavior.

PRAT, G., & ADAN, A. (2011) Influence of circadian typology on drug consumption, hazardous alcohol use, and hangover symptoms. Chronobiology International, 28, 248257.

RANDLER, C. (2007) Gender dierences in morningnesseveningness assessed by selfreport questionnaires: a meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Dierences, 43,

1667-1675.

RANDLER, C., EBENHH, N., FISCHER, A., HCHEL, S., SCHROFF, C., STOLL, J. C., VOLLMER, C.,

& PIFFER, D. (2012) Eveningness is related to men's mating success. Personality and

Individual Dierences, 53, 263-267.

ROENNEBERG, T., KUEHNLE, T., PRAMSTALLER, P. P., RICKEN, J., HAVEL, M., GUTH, A., & MERROW, M. (2004) A marker for the end of adolescence. Current Biology, 14, 1038-1039.

SOANE, E., & CHMIEL, N. (2005) Are risk preferences consistent?: the influence of decision

domain and personality. Personality and Individual Dierences, 38, 1781-1791.

STENSTROM, E., SAAD, G., NEPOMUCENO, M. V., & MENDENHALL, Z. (2011) Testosterone and

domain specific risk: digit ratios (2D:4D and rel2) as predictors of recreational,

financial, and social risk-taking behaviors. Personality and Individual Dierences,

51, 412-416.

TONETTI, L., ADAN, A., CACI, H., DE PASCALIS, V., FABBRI, M., & NATALE, V. (2010) Morningness-eveningness preference and sensation seeking. European Psychiatry, 25,

111-115.

TSAOUSIS, I. (2010) Circadian preferences and personality traits: a meta-analysis. European Journal of Personality, 24, 356-373.

WAGNER, A. M., & HOULIHAN, D. D. (1994) Sensation seeking and trait anxiety in hangglider pilots and golfers. Personality and Individual Dierences, 16, 975-977.

WANG, L., & CHARTRAND, T. L. (in press) Morningness-eveningness and risk-taking. The

Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied.

WEBER, E. U., BLAIS, A., & BETZ, N. E. (2002) A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making,

15, 263-290.

WELLER, J. A., & TIKIR, A. (2011) Predicting domain-specific risk taking with the HEXACO

personality structure. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 24, 180-201.

WON, K. S., & GRANT, J. E. (2001) Personality dimensions in pathological gambling disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Research, 104, 205-212.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 946

15/12/14 8:51 AM

EVENINGNESS AND RISK-TAKING

947

WONG, A., & CARDUCCI, B. J. (1991) Sensation seeking and financial risk taking in everyday money matters. Journal of Business and Psychology, 5, 525-530.

ZUCKERMAN, M., & KUHLMAN, D. M. (2000) Personality and risk-taking: common biosocial factors. Journal of Personality, 68, 999-1029.

Accepted October 21, 2014.

26_PR_Ponzi_140134.indd 947

15/12/14 8:51 AM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5824)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- McDonald's Decision Making ProcessDocument5 pagesMcDonald's Decision Making ProcessSyed Adnan Shah75% (4)

- Solution Manual For Children A Chronological Approach 5th Canadian Edition Robert V Kail Theresa ZolnerDocument26 pagesSolution Manual For Children A Chronological Approach 5th Canadian Edition Robert V Kail Theresa ZolnerAngelKelleycfayo99% (92)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- DocxDocument5 pagesDocxYuyun Purwita SariNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Bender Gestalt Visual Motor TestDocument41 pagesBender Gestalt Visual Motor TestJennifer CaussadeNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lesson Plan Template Slippery FishDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Template Slippery Fishapi-550546162No ratings yet

- Allegory Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesAllegory Lesson Planapi-269729950No ratings yet

- Escultor - Non Nursing TheoriesDocument2 pagesEscultor - Non Nursing TheoriesDaniela Claire FranciscoNo ratings yet

- AIP Presentation DraftDocument26 pagesAIP Presentation DraftUmme AbeehaNo ratings yet

- Journal Critique GuidelinesDocument4 pagesJournal Critique GuidelinesNadia MoralesNo ratings yet

- SummativeDocument2 pagesSummativeZack Diaz100% (1)

- Employee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Investigation On The RelationshipDocument4 pagesEmployee Empowerment, Job Satisfaction and Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Investigation On The Relationshipvolvo HRNo ratings yet

- 40 Years of Design Research Cross2007Document4 pages40 Years of Design Research Cross2007EquipoDeInvestigaciónChacabucoNo ratings yet

- Research Learning StylesDocument21 pagesResearch Learning Stylesanon_843340593100% (1)

- Q7 - Post BureaucracyDocument2 pagesQ7 - Post BureaucracyJooYi OngNo ratings yet

- Family Law and Policy SpeechDocument4 pagesFamily Law and Policy Speechapi-539169687No ratings yet

- Hints On Writing - Jordan Peterson PDFDocument2 pagesHints On Writing - Jordan Peterson PDFSantiagoNo ratings yet

- Identi-T Stress Program QuestionnaireDocument2 pagesIdenti-T Stress Program QuestionnairepenguinlovecandyNo ratings yet

- Exploring Symbols Lesson 1 Class 3Document4 pagesExploring Symbols Lesson 1 Class 3api-535552931No ratings yet

- Theory of Translation ModulDocument120 pagesTheory of Translation ModulTri Indri YaniNo ratings yet

- A Review On Multidisciplinary Personality of Private and Government Academic StaffDocument16 pagesA Review On Multidisciplinary Personality of Private and Government Academic StaffInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Speak English: Fluently & ConfidentlyDocument12 pagesSpeak English: Fluently & ConfidentlyMBBS MBBS91% (11)

- Summary Experimental Psychology Chapter 1 Until 8 + 10: MlvkustersDocument53 pagesSummary Experimental Psychology Chapter 1 Until 8 + 10: MlvkustersAnonymous J2Ld5LM5lNo ratings yet

- Unit 7: Observation and Inference: ObjectivesDocument7 pagesUnit 7: Observation and Inference: ObjectivesmesaprietaNo ratings yet

- B2+ UNIT 3 CultureDocument2 pagesB2+ UNIT 3 CultureJuan Pablo Rincon100% (1)

- Training Evaluation Form TemplatesDocument2 pagesTraining Evaluation Form TemplatesahmadNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Chantal Smeekens, Margaret S. Stroebe, Georgios AbakoumkinDocument8 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Chantal Smeekens, Margaret S. Stroebe, Georgios AbakoumkinDoriana JdioreantuNo ratings yet

- Presentation and Facilitation Skills Module 1: WorkshopDocument6 pagesPresentation and Facilitation Skills Module 1: WorkshopnoorhidayahismailNo ratings yet

- Cartas de Blyenberg-Spinoza-Reason - Daniel SchneiderDocument18 pagesCartas de Blyenberg-Spinoza-Reason - Daniel SchneiderAntonio AlcoleaNo ratings yet

- Locus of ControlDocument3 pagesLocus of ControlAmisha MehtaNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument4 pages1 PDFKashyap Chintu100% (1)