Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children: and K.L.N. Rao

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children: and K.L.N. Rao

Uploaded by

Donny Artya KesumaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children: and K.L.N. Rao

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children: and K.L.N. Rao

Uploaded by

Donny Artya KesumaCopyright:

Available Formats

Symposium on Pediatric Surgery I

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children

Prema Menon and K.L.N. Rao

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India

ABSTRACT

The most common surgery on the esophagus by pediatric surgeons the world over is performed in the newborn period in

babies with congenital esophageal atresia with tracheo-esophageal fistula. Post-operative complications like recurrent fistula,

anastomotic stricture and some patients with gastroesophageal reflux would also require surgical intervention. Apart from

esophageal dilatation, gastrostomy and feeding jejunostomy, children with strictures secondary to caustic ingestion, reflux or

previous esophageal anastomosis may require esophageal substitution. This operation may also be required in babies with

pure esophageal atresia as well as those with a long gap esophageal atresia with fistula. The entire stomach, stomach tubes,

colon or jejunum are often used but techniques preserving as much of the original esophagus as possible are preferable and

more physiological. Surgery is also required in children with congenital esophageal stenosis and duplication cyst. [Indian J

Pediatr 2008; 75 (5) : 939-943] E-mail : klnrao@hotmail.com

Key words : Esophageal surgery; Esophageal atresia; Esophageal replacement; Esophageal stricture; Thoracoscopy;

Esophagoplasty; Neonate; Child

Esophageal surgery is performed in all age groups in

children. The most common indication, esophageal atresia

(EA) is seen all over the world, especially so in our

country. In fact, surgery for EA is the most common

emergency surgery in neonates at our center, with about

180 cases per year. Healthy infants without pulmonary

complications or other major anomalies can undergo

primary repair in the first few days of life. Prompt

diagnosis with appropriate clinical management and

expeditious referral to a tertiary care center have led to

survival rates in this group of 100% percent.1 Due to the

sheer numbers, and inadequate intensive care facilities in

many parts of the country, overall results are not

comparable with western centers. Delayed presentations

are common but a lot of progress has been made over the

past few decades in units dedicated to neonatal surgery

even in this group.2 Long term follow-ups are available

even in babies who presented as late as on day 17 of life.3

While congenital anomalies form the bulk of the

indications for pediatric esophageal surgery, replacement

of the esophagus for acquired lesions like caustic strictures

are also performed, the techniques used being very

similar to those in adults.

forms an important part of the overall care.4 The baby

should be nursed with the chest in the upright position

and the oropharynx and upper pouch repeatedly

suctioned. Intravenous fluids, oxygen by hood and broadspectrum antibiotics are started. If there are features of

respiratory failure, the baby is intubated. Bag-mask

ventilation is not appropriate since it may cause acute

gastric distention requiring emergency gastrostomy.

Chest radiographs should be evaluated carefully for

skeletal abnormalities, cardiovascular malformations,

pneumonia, diaphragmatic hernia and a right aortic arch.

Before surgery, it is important to examine the babys

abdomen and perineum. An abdominal radiograph to

detect distal gas should be done as the surgical approach

would not involve a thoracotomy in babies with pure EA.

This is also evaluated for skeletal abnormalities, intestinal

obstruction and malrotation. A contrast upper

gastrointestinal series is not recommended. An

echocardiogram and renal ultrasonogram should be

obtained. The baby should be shifted to an intensive care

unit and operated after proper evaluation and

stabilization is achieved.

Correspondence and Reprint requests : Dr. K.L.N.Rao, Professor

and Head, Department of Pediatric Surgery, Advanced Pediatric

Center, P.G.I.M.E.R., Chandigarh, 160012, India. Ph: 0091-1722747585 Ext. 5320 (Off), 2715314 (Res), 09914208320 (M); Fax: 0091172-2744401, 2745078

The survival rate in babies with low birth weight,

pneumonia or other major anomalies is lower with cardiac

anomalies being the main cause of death. The Waterston

classification appears to be still relevant as a prognostic

indicator in our setup.5 These babies are managed with

parenteral nutrition, gastrostomy to prevent reflux of

gastric contents through the fistula into the trachea and

upper pouch suction until they are appropriate surgical

candidates.

Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 75September, 2008

939

Surgery in Neonate with Esophageal Atresia

Correct preoperative management of a baby with EA

Prema Menon and K.L.N. Rao

Bronchoscopy prior to starting of the procedure is

performed in many centers. A prospective study in our

department showed that it helped in identifying the

upper pouch fistula, distance of the lower pouch fistula

from the carina thereby helping placement of

endotracheal tube beyond the fistula during surgery as

well as identifying tracheomalacia. Although

postoperative pulmonary complications and ventilator

requirements were reduced, it did not alter the mortality

rate. 6

Surgical repair is performed under general anesthesia

with endotracheal intubation through a right

posterolateral thoracotomy. Frequent desaturation can

occur during surgery especially while retracting the lung.

An experienced anesthetist is therefore essential as these

babies should be manually ventilated with low

inspiration pressures and small tidal volumes. The azygos

vein is usually the first structure to be identified after

thoracotomy. As it lies over the tracheoesophageal fistula,

it is routinely ligated and divided. In a recent study, it has

been suggested that by preserving the azygos vein, early

postoperative edema of the esophageal anastomosis can

be prevented resulting in a significant reduction in the

number of anastomotic leaks.7

Post-operatively babies are nursed in a TEF chair, so

that elevation of the head end is always maintained at an

angle of 30-45o.8 We routinely start feeds on the 2nd postoperative day through a trans-anastomotic nasogastric

tube which has been inserted at the time of surgery.4

In long gap EA, babies often end up with an initial

gastrostomy and esophagostomy. Many complications

are encountered with a gastrostomy before the patient

gets an esophageal replacement. Although, it is routinely

advised to minimally dissect the lower pouch because of

its perceived deficiency of blood supply and to preserve

the vagal fibres, mobilization of the lower pouch can

bridge the defect in the first attempt and is far more

physiological than an esophageal replacement. In a

prospective, randomized study in our department, we

compared 20 neonates with long gap EA and TEF

managed by ligation of fistula, distal pouch mobilization

and primary repair versus ligation of fistula,

esophagostomy and gastrostomy followed by delayed

esophageal replacement. 9 The mean duration of

hospitalization as well as final survival was statistically

significant in favor of the first group (p<0.05).

difficulties occur. Recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula

would require surgical correction and is mostly seen at

the site of the primary anastomosis. Using a ventilating

bronchoscope, the fistula is cannulated with a ureteric

catheter which is then identified through

esophagoscopy. 10 Tissue damage of the poorly

vascularized distal esophagus and surgical dissection

performed too close to the trachea have been postulated

as risk factors.

Approximately one half of patients with surgically

corrected EA develop gastroesophageal reflux disease

(GERD). Of these, one half responds to routine medical

therapy with prokinetic agents, histamine H2 receptor

blockers, or both, while the other requires surgical

intervention in the form of fundoplication for correction.

Long-term endoscopic follow-up may be indicated in

these patients to look out for Barretts esophagus and its

sequelae. In a prospective study in our unit over a 2 year

period, 27 babies developed anastomotic leak. Creation of

a feeding jejunostomy in 71% of the patients allowed us to

maintain nutrition and also reduced the percentage of

feeds in intercostal chest drain on an average from 25% to

8 %, thus reducing chest contamination. There is a high

incidence of GER in these babies and an additional

gastrostomy gave better results than feeding jejunostomy

alone. (Monika Bawa, MCh thesis. Efficacy of

management protocol for anastomotic leak after repair of

EA and TEF, PGIMER. 2007).

Esophageal stricture

A contrast esophagogram is essential to know the

anatomy of the esophagus, presence of multiple strictures

as well as capacity and drainage of the stomach. In

patients with associated GER, this should be first

managed surgically before any definitive procedure on

the esophagus. Most respond well to further esophageal

dilatation. Localized strictures would require resection

and anastomosis. During dilatation, if an esophageal

opening cannot be found through endoscopy, a minilaparotomy and gastrostomy followed by retrograde

dilatation should be attempted before opting for organ

replacement / bypass procedures. Long strictures

especially secondary to caustic ingestion often require

esophageal replacement.

Esophageal Replacement

Most neonates who undergo repair of EA and TEF have

some degree of esophageal dysmotility which resolves

with time. Strictures at the site of the anastomosis are

common and may subsequently require dilatation. Serial

esophagography should be performed at two months, six

months and one year of age, or whenever swallowing

Esophageal replacement is indicated in children with pure

EA, long-gap EA when anastomosis is not possible,

corrosive strictures and other unusual causes. Type and

location of the graft depend on etiology and surgeon

preferences. Several options are now available with good

results, such as use of the native esophagus or

replacement with colon, stomach, or small bowel.

Common problems with all esophageal substitutions

include high stricture rate, leaks, GER and nutritional

problems. An optimal substitute for the esophagus should

940

Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 75September, 2008

Complications after esophageal atresia repair and their

management

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children

preserve the native esophagus, have normal caliber, no

space occupying lesion in the mediastinum, preserve

gastric reservoir function, should withstand acidity and

have a shorter suture line. Spitz et al recently published

their results of 173 gastric transpositions through the

posterior mediastinal route.13 They observed that stomach

functions as a conduit rather than as a reservoir.

Nutritional problems as well as restricted pulmonary

function appear to be common features.

Native esophageal reconstruction is the procedure of

choice rather than esophageal replacement. A long-term

retrospective review of 21 out of 26 infants with pure EA

who underwent delayed primary anastomosis between

1977 and 2004 showed that this provides excellent

functional results in spite of the high incidence of GER

(66%) with 43% of these needing fundoplication.12 Sixteen

children developed strictures at the anastomotic site; 10

responding to repeated dilatations while 6 needed

resection and reanastomosis. At the end of the study

period, 15 out of the 17 survivors (88%) were on normal

diet with no respiratory problems while 2 (12%) were

dependent on gastrostomy feeds. There were four deaths

(19%) in this group. This method of management is based

on the natural growth of the esophagus with the interim

period managed by upper pouch suctioning and

nutritional support. The median age at operation was 80

days and the median hospital stay was 5.5 months which

may not be feasible in our setup.

Reconstructive methods using gastric tubes are

popular. Preparation of patient for gastric tube

esophagoplasty includes pre-operative contrast study via

gastrostomy or barium swallow, dietary advice i.e. high

protein diet with evidence of weight gain, as well as

assessment and management of co-existent cardiac and

pulmonary lesions. Sham feeding should always be

started after esophagostomy to develop oral feeding

mechanisms early and shorten time to complete oral

feeding after delayed esophageal repair. Counseling of

parents regarding 2 procedures, i.e. gastric tube

esophagoplasty followed by closure of esophageal ends

approx 6 weeks later, duration of hospital stay which is

likely to be more after the 2nd surgery, likely anesthetic

complications, chest complications, as well as possibility

of esophageal dilatations after completion of all stages

should be done well in advance.

We first reported our technique of fundal tube

esophagoplasty in 2003 in 4 patients where the entire

native lower esophagus is retained with the remaining

required length created out of the fundus as a tube in

continuity.13 This is not possible with any other substitute

except interposition grafts. The tube is brought out

through the neck in a retrosternal fashion. Postoperatively a chest X-ray should be performed

immediately after surgery (day 0). A few weeks later, a

contrast study is done through the neck stoma followed

Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 75September, 2008

by esophago-esophageal anastomosis. Since native

esophagus is used, there is less chance of peptic ulceration

at the anastomotic site. More of the stomach is available

increasing intake and reducing chances of reflux. After

closure of the neck stomas, oral contrast study to see

caliber, stenosis, leak, stricture, reflux and stomach

capacity is performed. Clinically, patients should be

assessed for improvement in growth percentiles,

developmental milestones, respiratory tract assessment,

ability to take solids and liquids orally without difficulty

ad libitum. We have so far (2001-2007) performed this

procedure successfully in 28 patients having pure EA (9),

EA/ TEF with leak or long gap (16) and caustic strictures.3

Seven patients had prolonged salivary leak which was

managed conservatively with nutritional management

and esophageal dilatation with only one requiring

excision of fistula tract. Long-term complications have

included stricture in 3 cases requiring local resection in 2

and conversion to colon interposition in 1. Dysphagia (5)

mostly improved with time and 1-2 esophageal

dilatations. Reflux related problems were managed with

head up position, H2 blockers for 2 years at least and

fundoplication in all patients. Mobilization of esophagus

is sometimes difficult in patients with caustic strictures

and post leaking EA/TEF. Additional thoracotomy was

required in 2 children with caustic esophageal strictures.

Poorly placed gastrostomy tube with injury to

gastroepiploic arcade, odd location of cervical

esophagostomy, intraabdominal adhesions and small

capacity stomach create additional problems during

creation of the fundal tube.

Gastric tubes are simple to construct and long lengths

can be created. Neo angle of His can be created, and the

distal part of the tube remains in the high pressure

abdominal zone reducing chances of reflux.

Fundoplication can also be easily added to the procedure.

But anastomosis between cervical esophagus and antral

gastric mucosa increases likelihood of peptic ulceration at

anastomotic site. These reversed gastric tubes require

good stomach capacity so that sufficient length of tube to

reach the neck can be created, normal stomach drainage

and motility and availability of left gastroepiploic artery

and arcade. Advantages over colonic interposition include

rich blood supply, no tension on the interposed segment,

resistance of gastric mucosal tube to acid ulceration and

no bowel complications like diarrhea. Complications of

reversed gastric tube include cervical anastomotic leak,

stricture, narrowing at diaphragmatic hiatus, smaller

feeds due to reduced stomach capacity, acid reflux and

psychological difficulties. Our own long term results of

reversed gastric tube (n=10), show that although they

require multiple esophageal dilatations, and have

prolonged neck leak, ultimately almost all patients do

well and are able to take solids orally without difficulty.

In a series of 21 children who had isoperistaltic gastric

tube for varied indications, 16 could accept a normal diet,

941

Prema Menon and K.L.N. Rao

2 had significant dysphagia and 3 needed a feeding

jejunostomy. The esophagogastric anastomosis leaked in

2 cases, but both closed spontaneously. A temporary

dumping syndrome was encountered in two children.

Two patients had strictures of their upper anastomosis

responding to dilatations. The two patients who had a

pharyngogastric anastomosis developed either intractable

stricture or nonfunctioning anastomosis. One of them

died 9 months later from aspiration pneumonitis. Two

patients had cervical Barretts esophagus above the

anastomosis, indicating the need for lifelong endoscopic

follow-up. 14

Hadidi has developed a simple technique to improve

the results of colon replacement of the esophagus in

children. 15 In 5 neonates with long gap EA with or

without fistula and another 6 with long segment caustic

esophageal stricture, at the gastrostomy operation, the

segment of colon to be used for replacement was chosen

and the trunk of the corresponding vessel say middle

colic artery supplying the transverse colon was ligated

and divided proximal to the marginal artery. One to three

months later, this colon was used for esophageal

replacement. The follow-up ranged from 21-56 months.

By increasing the blood supply to the transverse colon

through the left upper colic and marginal vessels, the

success rate of colonic replacement improved and

minimized morbidity. Only 1 patient developed stricture

at the colo-esophageal anastomosis which required

resection and anastomosis six months later.

Thoracoscopy in EA and other esophageal surgery

The thoracoscopic approach to the treatment of EA is

being increasingly performed. Secondary effects like

thoracic cage deformities, winged scapula, or scoliosis are

reduced in comparison to the open technique. In a study

of 51 neonates with EA managed thoracoscopically, the

operative procedure took 90-390 minutes (mean 178

minutes) which is understandable. However, the stenosis

rate (45%) appears to be much higher than with the

conventional open technique. Postoperative leakage

occurred in 9 patients (18%). In this study, 6 patients also

underwent thoracoscopic aortopexy for tracheomalacia.

In 2 patients the thoracoscopic procedure had to be

converted to a thoracotomy.16

In a multi-institutional analysis of 104 newborns with

a mean weight of 2.6 kg (0.5), who underwent

thoracoscopic repair of EA, the mean operative time was

129.9 minutes 55.5 with 11.5% infants developing an

early leak or stricture at the anastomosis. 17 Thirty three

(31.7%) required esophageal dilatation at least once.

Conversion to an open thoracotomy was done in 5 cases.

However, 25 newborns (24.0%) later required a

laparoscopic fundoplication, the incidence of which

appears to be much higher than with the open technique.

Three patients died, one related to the EA/TEF on the

20th postoperative day. Although cosmetic results may be

942

better, no other major advantage has been demonstrated

by the laparoscopic route so far.

Compared to adults, achalasia is rare in children.

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy with a partial

fundoplication is presently the gold standard for

managing this condition in children.18

Other causes of esophageal obstruction

While evaluating a newborn with drooling of saliva and

respiratory distress, diagnosis other than EA should be

kept in mind. Traumatic instrumentation can produce

pharyngeal or upper esophageal perforation and an

attempt at passage of a catheter may produce a false

passage submucosally or a pseudodiverticulum.19 In the

absence of traumatic instrumentation a spontaneous

perforation of esophagus should be considered. Mostly

the mucosal tear heals spontaneously, however, the risk

of mediastinitis does exist. Rarely, thoracotomy may be

indicated. Esophagoscopy is contraindicated in these

cases as it may actually increase the size of the

perforation. Babies should be monitored for leukocytosis,

fever and swallowing abnormalities. Obstruction of the

lower end of esophagus can occur rarely due to congenital

esophageal stenosis which may respond to bouginage,

endoscopic excision of diaphragm or surgical resection

anastomosis. Enteric duplication cysts can occur in

relation to the wall of the esophagus rarely

communicating with its lumen. They can usually be

removed preserving the esophageal integrity by

thoracotomy or thoracoscopy. Esophageal intramural

pseudo-diverticulosis is another extremely rare entity in

children associated with hiatus hernia and benign

esophageal stricture secondary to GER. Patients present

with intermittent but slowly progressive dysphagia

especially for solids. They symptomatically respond to

esophageal dilatation and fundoplication.20

CONCLUSIONS

Esophageal surgery in neonates requires high degree of

surgical skills and good neonatal postoperative nursing

care. Post-operative problems are very common after any

form of esophageal replacement but success can be

achieved in almost all cases. However, the surgeon has to

be passionate towards the baby, tenacious and also give

moral support to parents who may get disillusioned with

the time taken for ultimate recovery. This is the most

important aspect for the surgeons who wish to care for

these children with esophageal substitutions.

REFERENCES

1. Bendi G, Chowdhary SK, Rao KLN. Esophageal atresia with

tracheoesophageal fistula: an audit. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg

2004; 9: 126-130

Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 75September, 2008

Esophageal Surgery in Newborns, Infants and Children

2. Narasimharao KL, Joglekar A, Mitra SK, Pathak IC.

Oesophageal atresia: delayed presentation and survival. J

Indian Med Assoc 1985; 83 : 284-285.

3. Menon P, Samujh R, Rao KLN. Esophageal atresia. Indian J

Pediatr 2005; 72 : 539.

4. Menon P, Rao KLN. Management of esophageal atresia and

tracheoesophageal fistula. Bulletin of Pediatr Gastroenterol

Hepatol Nutr 2003; 1: 5-12.

5. Eradi B, Narasimhan KL, Rao KLN et al. Waterston

classification revisited-Its relevance in developing countries. J

Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 2003; 8 : 58-63.

6. Pimpalwar A, Kaplish B, Rao KLN, Puri GD, Mitra SK.

Esophageal atresia: Is routine bronchoscopy before

thoracotomy useful? J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 1997; 2 : 60-62.

7. Sharma S, Sinha SK, Rawat JD, Wakhlu A, Kureel SN, Tandon

R. Azygos vein preservation in primary repair of esophageal

atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula. Pediatr Surg Int 2007;

23: 1215-1218.

8. Kalia R, Menon P, Rao KLN. Nursing care for the surgical

neonate. J Neonatology 2005; 19: 270-277.

9. Tripathy PK, Rao KLN, Chowdhary SK et al. Lower pouch

mobilization in long gap esophageal atresia. J Indian Assoc

Pediatr Surg 2004; 9 : 172-178.

10. Narasimhan KL, Rao KLN, Mitra SK. Management of

recurrent tracheoesophageal fistula. Indian Pediatr 1990; 27 :

1114-1116.

11. Sri Paran T, Decaluwe D, Corbally M, Puri P. Long-term

results of delayed primary anastomosis for pure oesophageal

atresia: a 27-year follow up. Pediatr Surg Int 2007; 23 : 647-651.

12. Rao KLN, Menon P, Samujh R, Chowdhary SK, Mahajan JK.

Fundal tube esophagoplasty for esophageal reconstruction in

atresia. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38 : 1723-1726.

13. Spitz L, Kiely E, Pierro A. Gastric transposition in children: a

21 year experience. J Pediatr Surg 2004; 39 : 276-281.

14. Borgnon J, Tounian P, Auber F et al. Esophageal replacement

in children by an isoperistaltic gastric tube: a 12-year

experience. Pediatr Surg Int 2004; 20 : 829-833.

15. Hadidi A. A technique to improve vascularity in colon

replacement of the esophagus. Eur J Pediatr Surg 2006; 16 : 3944.

16. van der Zee DC, Bax KN. Thoracoscopic treatment of

esophageal atresia with distal fistula and of tracheomalacia.

Semin Pediatr Surg 2007; 16 : 224-230.

17. Holcomb GW III, Rothenberg SS, Bax KMA et al.

Thoracoscopic repair of esophageal atresia and

tracheoesophageal fistula, a multi-institutional analysis. Ann

Surg 2005; 242 : 422-430.

18. Mattioli G, Esposito C, Prato AP et al. Results of the

laparoscopic Heller-Dor procedure for pediatric esophageal

achalasia. Surg Endosc 2003; 17: 1650.

19. Narasimharao KL, Sachdeva S, Narang A et al. Perforation of

pharynx mimicking esophageal atresia. Indian Pediatr 1985; 22

: 538-540.

20. Garg K, Katariya S, Narasimharao KL, Pathak IC. Esophageal

intramural pseudo-diverticulosis. Indian Pediatr 1985; 22 : 163166.

Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Volume 75September, 2008

943

You might also like

- To Make Flip Flop Led Flasher Circuit Using Transistor Bc547Document17 pagesTo Make Flip Flop Led Flasher Circuit Using Transistor Bc547ananyabedekar83No ratings yet

- The Essentials of Psychodynamic PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesThe Essentials of Psychodynamic PsychotherapyMarthaRamirez100% (3)

- Gastroschisis DNYDocument37 pagesGastroschisis DNYDonny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Lab2 PDFDocument3 pagesLab2 PDFMd.Arifur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Bullying, Stalking and ExtortionDocument17 pagesBullying, Stalking and ExtortionJLafge83% (6)

- Non Aero Revenue - MBA ProjectDocument68 pagesNon Aero Revenue - MBA ProjectSuresh Kumar100% (2)

- Postoperative Complications and Functional Outcome After Esophageal Atresia Repair: Results From Longitudinal Single-Center Follow-UpDocument9 pagesPostoperative Complications and Functional Outcome After Esophageal Atresia Repair: Results From Longitudinal Single-Center Follow-Upzivl1984No ratings yet

- Imaging of Congenital Anomalies of The Gastrointestinal TractDocument12 pagesImaging of Congenital Anomalies of The Gastrointestinal TractMateen ShukriNo ratings yet

- Pa Tho Physiology of HirschprungDocument4 pagesPa Tho Physiology of HirschprungRenz Javier Tuñacao LustreNo ratings yet

- Reflection For 79th Annual Clinical Congress 24th Asian Congress of SurgeryDocument4 pagesReflection For 79th Annual Clinical Congress 24th Asian Congress of Surgerysjmc.surgeryresidentsNo ratings yet

- Incarceratedpediatric Hernias: Sophia A. Abdulhai,, Ian C. Glenn,, Todd A. PonskyDocument17 pagesIncarceratedpediatric Hernias: Sophia A. Abdulhai,, Ian C. Glenn,, Todd A. PonskyPhytoplankton DiatomsNo ratings yet

- AfrJPaediatrSurg122119-3052943 082849 PDFDocument3 pagesAfrJPaediatrSurg122119-3052943 082849 PDFAndikaNo ratings yet

- Temporary Retrograde Occlusion of High-Flow Tracheo-Esophageal FistulaDocument6 pagesTemporary Retrograde Occlusion of High-Flow Tracheo-Esophageal FistulaGunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- De La TorreDocument11 pagesDe La TorreRAPTOR111No ratings yet

- New Developments in Anal Surgery Congenital Ano RectalDocument5 pagesNew Developments in Anal Surgery Congenital Ano RectalOctavianus KevinNo ratings yet

- Peg & TPNDocument23 pagesPeg & TPNapi-3722454100% (1)

- Basic Principles of Enteral Feeding: Hale AkbaylarDocument6 pagesBasic Principles of Enteral Feeding: Hale AkbaylarAbdul NazirNo ratings yet

- Management of Rectal Prolapse P WAGDocument19 pagesManagement of Rectal Prolapse P WAGWaNda GrNo ratings yet

- Supra-Transumbilical Laparotomy (STL) Approach For Small Bowel Atresia Repair: Our Experience and Review of The LiteratureDocument5 pagesSupra-Transumbilical Laparotomy (STL) Approach For Small Bowel Atresia Repair: Our Experience and Review of The LiteratureFebri Nick Daniel SihombingNo ratings yet

- GASTROSCHISISDocument4 pagesGASTROSCHISISVin Custodio100% (1)

- 10.7556 Jaoa.2011.111.1.44Document5 pages10.7556 Jaoa.2011.111.1.44DianaNo ratings yet

- Management of Rectal Prolapse in Children: Our Experience of Thiersch Stitch ProcedureDocument4 pagesManagement of Rectal Prolapse in Children: Our Experience of Thiersch Stitch Procedureade-djufrieNo ratings yet

- Tracheoesophageal Atresia: Mrs - Smitha.M Associate Professor Vijaya College of Nursing KottarakkaraDocument10 pagesTracheoesophageal Atresia: Mrs - Smitha.M Associate Professor Vijaya College of Nursing KottarakkarakrishnasreeNo ratings yet

- A Retrospective Clinical Study of Perforation Peritonitis in Rural Area in Andhra Pradesh November 2022 9921131660 120 PDFDocument9 pagesA Retrospective Clinical Study of Perforation Peritonitis in Rural Area in Andhra Pradesh November 2022 9921131660 120 PDFVijay KumarNo ratings yet

- Management of Jejunoileal Atresia: Our 5 Year ExperienceDocument4 pagesManagement of Jejunoileal Atresia: Our 5 Year ExperienceOvamelia JulioNo ratings yet

- Fistula Enterokutan 1Document8 pagesFistula Enterokutan 1Amalia GrahaniNo ratings yet

- OmphaloceleDocument23 pagesOmphaloceleFred PupeNo ratings yet

- Fistula Enterokutan 1Document8 pagesFistula Enterokutan 1Amalia GrahaniNo ratings yet

- Colonic Atresia Revision 1Document10 pagesColonic Atresia Revision 1HenggarAPNo ratings yet

- Atresia Esofágica Con Fistula Traqueoesofágica DistalDocument24 pagesAtresia Esofágica Con Fistula Traqueoesofágica DistalChristian PA100% (1)

- 2 Gastric and Duodenal Peptic Ulcer Disease 2Document35 pages2 Gastric and Duodenal Peptic Ulcer Disease 2rayNo ratings yet

- Paediatric AnsDocument142 pagesPaediatric AnsAbdulkadir HasanNo ratings yet

- Shalita Dastamuar Pediatric Surgery Subdivision, Surgery Department Mohammad Hoesin HospitalDocument18 pagesShalita Dastamuar Pediatric Surgery Subdivision, Surgery Department Mohammad Hoesin HospitalSoni TfacNo ratings yet

- Hernia Hiatal 3Document10 pagesHernia Hiatal 3María Alejandra García QNo ratings yet

- Common Pediatric Surgery ProblemsDocument141 pagesCommon Pediatric Surgery Problemssedaka26100% (4)

- Common Neonatal Surgical Conditions: Intensive Care Nursery House Staff ManualDocument6 pagesCommon Neonatal Surgical Conditions: Intensive Care Nursery House Staff ManualSayf QisthiNo ratings yet

- Common Complication: What Is It?Document5 pagesCommon Complication: What Is It?khalidicuNo ratings yet

- Chylous Ascites Following Kasai PortoentDocument3 pagesChylous Ascites Following Kasai PortoentАлександра КондряNo ratings yet

- Gastro SCH Is IsDocument13 pagesGastro SCH Is IsferoNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: Dealing With ComplicationsDocument9 pagesA Literature Review of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy: Dealing With ComplicationsHenry BarberenaNo ratings yet

- Enteral Feeding: Gastric Versus Post-Pyloric: Table 1Document22 pagesEnteral Feeding: Gastric Versus Post-Pyloric: Table 1tasmeow23No ratings yet

- Case Report On Spontaneous Restoration of Bowel ContinuityDocument5 pagesCase Report On Spontaneous Restoration of Bowel Continuityofficial.drjainNo ratings yet

- BaldwinDocument6 pagesBaldwinalexafarrenNo ratings yet

- Seminars in Pediatric Surgery: Short Bowel Syndrome in Children: Surgical and Medical PerspectivesDocument7 pagesSeminars in Pediatric Surgery: Short Bowel Syndrome in Children: Surgical and Medical PerspectivesrodyNo ratings yet

- Outcomes of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in ChildrenDocument7 pagesOutcomes of Percutaneous Endoscopic Gastrostomy in ChildrenHenry BarberenaNo ratings yet

- Pyloric Stenosis WDocument11 pagesPyloric Stenosis WKlaue Neiv CallaNo ratings yet

- Oesophageal Atresia by GabriellaDocument7 pagesOesophageal Atresia by GabriellaGabrielleNo ratings yet

- Intestinal Atresia: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesIntestinal Atresia: A Case ReportOvamelia JulioNo ratings yet

- Explor LaparotomyDocument14 pagesExplor LaparotomyGracia NievesNo ratings yet

- Adult Intussusception A Case ReportDocument4 pagesAdult Intussusception A Case ReportRahmanssNo ratings yet

- Minimallyinvasive Esophagectomyforbenign Disease: Blair A. JobeDocument10 pagesMinimallyinvasive Esophagectomyforbenign Disease: Blair A. JobeYacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- 3 Common Pediatric Surgery ContinuedDocument5 pages3 Common Pediatric Surgery ContinuedMohamed Al-zichrawyNo ratings yet

- Infant With Pentalogy of Cantrell and Tetralogy of Fallot Requiring Omphalocele RepairDocument6 pagesInfant With Pentalogy of Cantrell and Tetralogy of Fallot Requiring Omphalocele RepairThia SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Transanal Endorectal PullthroughDocument8 pagesTransanal Endorectal PullthroughMuhammad Harmen Reza SiregarNo ratings yet

- Tubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDocument5 pagesTubular Ileal Duplication Causing Small Bowel Obstruction in A ChildDiego Leonardo Herrera OjedaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S105585861200090X MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S105585861200090X Mainmchojnacki81No ratings yet

- j.jpedsurg.2019.12.020Document6 pagesj.jpedsurg.2019.12.020Cirugia pediatrica CMN RAZA Cirugia pediatricaNo ratings yet

- Intestinaltransplantin Children: Nidhi Rawal,, Nada YazigiDocument7 pagesIntestinaltransplantin Children: Nidhi Rawal,, Nada YazigimacedovendezuNo ratings yet

- Gastroesophageal Reflux With Relevance To Pediatric Surgery - Presentation TranscriptDocument4 pagesGastroesophageal Reflux With Relevance To Pediatric Surgery - Presentation TranscriptAbdul Ghaffar AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Hirschsprun G'S Disease: Dr. Manish Kumar Gupta Assistant Professor Department of Paediatric Surgery AIIMS, RishikeshDocument48 pagesHirschsprun G'S Disease: Dr. Manish Kumar Gupta Assistant Professor Department of Paediatric Surgery AIIMS, RishikeshArchana Mahata100% (1)

- 19-Pediatric SurgeryDocument39 pages19-Pediatric Surgerycallisto3487No ratings yet

- Neonatal Tracheostomy - JonathanWalsh 2018Document12 pagesNeonatal Tracheostomy - JonathanWalsh 2018Ismael Erazo AstudilloNo ratings yet

- AtresiaDocument5 pagesAtresiakirtiNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Hernia Repair in Neonates, Infants and ChildrenDocument9 pagesLaparoscopic Hernia Repair in Neonates, Infants and ChildrenErick OematanNo ratings yet

- Prune Belly SyndromeDocument39 pagesPrune Belly SyndromeHudaNo ratings yet

- Esophageal Preservation and Replacement in ChildrenFrom EverandEsophageal Preservation and Replacement in ChildrenAshwin PimpalwarNo ratings yet

- Fingertips Injury: Literature ReviewDocument24 pagesFingertips Injury: Literature ReviewDonny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Wound Infection SepsisDocument27 pagesWound Infection SepsisDonny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Green 2016Document6 pagesGreen 2016Donny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- AsianJNeurosurg82112-3813641 103536Document4 pagesAsianJNeurosurg82112-3813641 103536Donny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Bedah Saraf OscaDocument11 pagesBedah Saraf OscaDonny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- JCO 2005 Low 2726 34Document9 pagesJCO 2005 Low 2726 34Donny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Aponeurotomy and Lipofilling: A Regenerative Alternative To Flap Reconstruction?Document11 pagesPercutaneous Aponeurotomy and Lipofilling: A Regenerative Alternative To Flap Reconstruction?Donny Artya KesumaNo ratings yet

- Kon Trak TurDocument6 pagesKon Trak TurZico ParadigmaNo ratings yet

- EoI DocumentDocument45 pagesEoI Documentudi969No ratings yet

- Senwa Mobile - S615 - Android 3.5inDocument6 pagesSenwa Mobile - S615 - Android 3.5inSERGIO_MANNo ratings yet

- Product Data Sheet Ingenuity Core LRDocument16 pagesProduct Data Sheet Ingenuity Core LRCeoĐứcTrườngNo ratings yet

- Shaping The Way We Teach English:: Successful Practices Around The WorldDocument5 pagesShaping The Way We Teach English:: Successful Practices Around The WorldCristina DiaconuNo ratings yet

- Linkages and NetworkDocument28 pagesLinkages and NetworkJoltzen GuarticoNo ratings yet

- Piglia - Hotel AlmagroDocument2 pagesPiglia - Hotel AlmagroJustin LokeNo ratings yet

- Teacher Learning Walk Templates - 2017 - 1Document13 pagesTeacher Learning Walk Templates - 2017 - 1Zakaria Md SaadNo ratings yet

- Present Continuous - Present Simple Vs Present ContinuousDocument2 pagesPresent Continuous - Present Simple Vs Present ContinuouseewuanNo ratings yet

- PBL KaleidoscopeDocument3 pagesPBL KaleidoscopeWilson Tie Wei ShenNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence and Patent LawDocument4 pagesArtificial Intelligence and Patent LawSaksham TyagiNo ratings yet

- The Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeDocument6 pagesThe Quiescent Benefits and Drawbacks of Coffee IntakeVikram Singh ChauhanNo ratings yet

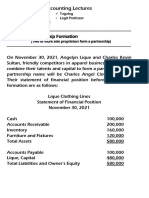

- 8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessDocument2 pages8 Lec 03 - Partnership Formation With BusinessNathalie GetinoNo ratings yet

- LEARNING THEORIES Ausubel's Learning TheoryDocument17 pagesLEARNING THEORIES Ausubel's Learning TheoryCleoNo ratings yet

- Proposal (Objective Jpurpose Jscope)Document3 pagesProposal (Objective Jpurpose Jscope)Lee ChloeNo ratings yet

- British Baker Top Bakery Trends 2023Document15 pagesBritish Baker Top Bakery Trends 2023kiagus artaNo ratings yet

- Comprehension Toolkit 1Document3 pagesComprehension Toolkit 1api-510893209No ratings yet

- Security and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduDocument12 pagesSecurity and Privacy Issues: A Survey On Fintech: (Kg71231W, Mqiu, Xs43599N) @pace - EduthebestNo ratings yet

- GIS Based Analysis On Walkability of Commercial Streets at Continuing Growth Stages - EditedDocument11 pagesGIS Based Analysis On Walkability of Commercial Streets at Continuing Growth Stages - EditedemmanuelNo ratings yet

- Tunis Stock ExchangeDocument54 pagesTunis Stock ExchangeAnonymous AoDxR5Rp4JNo ratings yet

- M HealthDocument81 pagesM HealthAbebe ChekolNo ratings yet

- Common AddictionsDocument13 pagesCommon AddictionsMaría Cecilia CarattoliNo ratings yet

- Asco Power Transfer Switch Comparison Features-3149 134689 0Document2 pagesAsco Power Transfer Switch Comparison Features-3149 134689 0angel aguilarNo ratings yet

- Metaverse Report - Thought Leadership 1Document17 pagesMetaverse Report - Thought Leadership 1Tejas KNo ratings yet

- Unit - 2 Sensor Networks - Introduction & ArchitecturesDocument32 pagesUnit - 2 Sensor Networks - Introduction & Architecturesmurlak37No ratings yet

- Print - Udyam Registration CertificateDocument2 pagesPrint - Udyam Registration CertificatesahityaasthaNo ratings yet