Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beyond Just Books: Sparking Children's Interest in Reading: ISSN 1948-5476 2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Beyond Just Books: Sparking Children's Interest in Reading: ISSN 1948-5476 2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Uploaded by

hoguptacmoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beyond Just Books: Sparking Children's Interest in Reading: ISSN 1948-5476 2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Beyond Just Books: Sparking Children's Interest in Reading: ISSN 1948-5476 2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Uploaded by

hoguptacmoCopyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Education

ISSN 1948-5476

2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Beyond Just Books:

Sparking Childrens Interest in Reading

Evan T. Ortlieb, Ph.D.

Assistant Professor

Texas A&M University Corpus Christi

Early Childhood Development Center 219H

6300 Ocean Drive Unit 5834, Corpus Christi, Texas 78412-5834, USA

Tel: 361-825-3661 Fax (361) 825-2562

E-mail: evan.ortlieb@tamucc.edu

Abstract

It is imperative that teachers use non-traditional texts to engage readers so that children do

not become disinterested in the reading process. Too many times, young children develop a

dislike toward reading, which can last a lifetime. Beneath layers of frustration and previous

failures, there lies an urge to read within every child. Often, students love to read other types

of printed text such as magazines and newspapers while they would not even consider

reading a book. After surveying my class of 25 students to determine their reading interests, I

gained administrative approval to subscribe to several magazines and newspapers specifically

geared towards children. Once these reading materials arrived, I acted as a salesman, trying to

convince my class to read the new types of print. Using centers, my students rotated between

reading magazines, newspapers, and hypertext on a daily basis for 15 minutes. As a result,

my students no longer complained that reading time was work; instead, reading became a fun

activity. The non-traditional texts acted as springboards towards reading meaningful books.

Keywords: Reading, Elementary, Interest, Alternate texts

www.macrothink.org/ije

International Journal of Education

ISSN 1948-5476

2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

In a society surrounded by immediate gratification, some children dislike reading because

they find books to be uninteresting. It is well known that motivating students to read by

providing texts of interest is an integral part of any effective reading program. As

comprehension research has made quite clear, students need to be able to identify with the

reading material either experientially or ideologically. After all, when texts make little or no

sense to children, they become disinterested. If this lack of interest remains for even a short

period of time, many students will no longer want to read. Reading will not be a fun activity;

instead, it will be considered work.

1. Untapped interests

From teaching first graders, I learned that sometimes hidden beneath layers of frustration,

previous failures, and disinterest in readings, there lies an urge to read. A recent conversation

with one student, Melanie, sparked this realization. She commented that she hates reading in

school because it is boring; however, when she gets home, she loves to read. That made me

think that the classroom setting was the determinant in her reading difficulties at school, yet it

was not. She continued, As soon as me [sic] and my sister get home, we read a lot of

magazines. Furthermore, There isnt cool stuff to read at school. I asked, Why do you all

enjoy reading magazines? According to Melanie, We like to pick up magazines, start

looking at the pages, and find spots with cool stuff to read about.

Melanie had an intense desire to read, but only texts of her choice. If this type of feeling is

widespread within children, why do schools, school libraries, and classrooms have so many

books compared to the other cool stuff that Melanie discussed? Could those other types of

print be used to expand students reading interests? Finding this answer seemed crucial to

determining how to spark interest in reading within first graders.

2. Background

Since first grade students are just beginning to learn the complexities of the reading process,

they need an awareness of other reading materials, besides books, that are also meaningful.

Additionally, first grade is when struggling readers may become easily frustrated and begin to

dislike reading all together. Rather than setting the stage for students to establish low

tolerance towards printed text, indeed it seems logical to give them material that is of high

interest that is reading materials that keep their attention, appeal to them, and allow them

to make sense of text (Johnson & Keier, 2010; Walker, 2003).

3. Methods

The conversation with Melanie prompted me to issue a questionnaire to my 25 first graders to

determine which types of text were most appealing to them. The survey asked students to

circle their answers to questions related to interest and preferences associated with multiple

forms of text. Each question was read aloud to minimize their confusion associated with

taking the survey. Responses that were not clearly depicted were not recorded nor tallied as

part of the data analysis process. Students were allowed to ask questions during the survey

completion.

www.macrothink.org/ije

International Journal of Education

ISSN 1948-5476

2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

4. Results

The findings were quite unanimous, prompting me to change my conceptualization about

teaching reading. A vast majority of the students (17 of 25, or 68%) liked other materials like

pamphlets, magazines, and cartoon strips more than books. Reading digital texts (hypertext)

was noted as the second most popular medium for reading, as 15 of 25 respondents (60%)

noted their preference of reading texts on a computer. Although the data indicate an array of

student interest, there were no other survey items with which a majority of students agreed.

After analyzing the data, it was obvious that I should adapt my classroom environment

towards alternate texts and digital literacies to suit the childrens interests. Soon, I gained

approval from administration to subscribe to several magazines and newspapers specifically

tailored for young children. Additionally, I added interesting opportunities for students to be

encouraged to read print-rich texts. As children become engaged, they more actively

participate in reading activities within print-rich environments (Manyak, 2008; Zucker et al.,

2009). By setting up three computers in the classroom on childrens informational websites,

students could read online as well. Now that there were other forms of text for children to

read, would it in fact make any difference in engaging them to read at school?

5. Selling the text

Describing the particular magazines related to sports, news, and discoveries seemed

influential in sparking an interest to read. Vasquez (2010) concluded that children read what

is interesting to them. Furthermore, researchers have found that varied media assist in literacy

development (Considine et al., 2009). Still, just because new magazines and newspapers were

added to my classroom did not mean that the students would be automatically interested. I

had to sell these products and persuade them to read these materials. Prior to telling the

students about the available texts, I pulled what I thought were the most exciting articles

within them so I could convince them how fun it was to read these texts. After a brief

introduction and discussion about the additional texts which were available, my students were

excited about having the opportunity to use them. To provide students adequate time, I

allocated 15 minutes within the language arts period solely for the act of reading using these

types of media. Since there were a limited number of magazines, newspapers, and computers,

I established a system in which students rotated between the different stations to ensure every

student had equal access to the materials.

6. Changing students conceptions of reading

Since the new types of texts (magazines, newspapers, and hypertext) were added to the

classroom, my students rarely, if ever, complained about reading time. They had reading

materials that truly interested and excited them. Guthrie (2000) found similar results,

claiming that teachers create contexts for engagement by allowing for meaningful choices as

well as interesting texts that are relevant. Although this may seem obvious, many times

teachers get caught up in meeting grade-level-expectations or planning elaborate lessons.

They forget about the power of allotting time and interesting materials for students to read in

class. Others have given up on the idea because students get off task easily; yet, most likely,

3

www.macrothink.org/ije

International Journal of Education

ISSN 1948-5476

2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

those classrooms are not filled with reading materials of the students choice. I cannot

emphasize enough the power and result of asking students what they would like to read. If

and when the students say nothing, prompt their thinking by giving an interest inventory

containing questions like: What do you do after school?, What types of sports, music, and

activities do you like?, and If you had a wish, what would it be? This exercise will allow

students to recognize their interests, and thus, stimulate them to read materials related to these

topics.

7. Reflections

In all, my class became interested readers because I gave my students something that they

wanted to read texts of their choice. This is crucial within every classroom, especially

where the students are emerging readers. Reading materials or texts are often the determinant

in whether students enjoy reading for self-fulfillment or lose interest in reading all together.

My class responded well to the approach because they no longer felt that reading was a chore;

it was an opportunity to do something fun while they were at school. Unbeknownst to many

of the students, they learned to comprehend better, as Malloy et al. (2010) iterate, because

they read more often and for longer periods of time while engaged in the material. Essentially,

magazines, newspapers, and hypertext provided my students with resources that sparked their

interest in reading. Utilizing these reading materials acted as a springboard for enticing

students to read books. The overall goal was indeed achieved students enjoyed reading in

the classroom and in turn, learning occurred.

References

Considine, D., Horton, J., & Moorman, G. (2009, March). Teaching and reaching the

millennial generation through media literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 52(6),

471481. doi: 10.1598/JAAL.52.6.2

Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M.L.

Johnson, P., & Keier, K. (2010). Catching readers before they fall: Supporting readers who

struggle, K-4. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Kamil, P.B. Mosenthal, P.D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research:

Volume III, 403- 422. New York: Erlbaum.

Malloy, J. A., Marinak, B., & Gambrell, L. (Eds). (2010). Essential readings on motivation.

Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Manyak, P. C. (2008, March). What's your news? Portraits of a rich language and literacy

activity for English-Language Learners. The Reading Teacher, 61(6), 450458. doi:

10.1598/RT.61.6.2

Vasquez, V. (2010, April). Critical literacy isn't just for books anymore. The Reading

Teacher, 63(7), 614616. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.7.11

Walker, B. J., & Rivers, D. (2003). Supporting struggling readers. Toronto, Ontario: Pippin

Publishing.

4

www.macrothink.org/ije

International Journal of Education

ISSN 1948-5476

2010, Vol. 2, No. 2: E9

Zucker, T.A., Ward, A.E., & Justice, L.M. (2009, September). Print referencing during

read-alouds: A technique for increasing emergent readers' print knowledge. The Reading

Teacher, 63(1), 6272. doi: 10.1598/RT.63.1.6

www.macrothink.org/ije

You might also like

- ENGLISH 16: Overview Factors Affecting Interest in LiteratureDocument3 pagesENGLISH 16: Overview Factors Affecting Interest in LiteratureNicole S. Jordan91% (11)

- Frankenstein Unit PDFDocument24 pagesFrankenstein Unit PDFapi-240344616100% (1)

- Common 1. Develop and Update Industry KnowledgeDocument77 pagesCommon 1. Develop and Update Industry KnowledgeCrisostomo Mateo50% (2)

- Topic and Purpose: Research Process) - The Third Phase Requires That Solid Questions Are Written and An ActionDocument13 pagesTopic and Purpose: Research Process) - The Third Phase Requires That Solid Questions Are Written and An Actionapi-288073522No ratings yet

- Action Report Research PaperDocument6 pagesAction Report Research Paperapi-710156794No ratings yet

- Erics Senior Project 2Document16 pagesErics Senior Project 2api-288073522No ratings yet

- Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Information Literacy But Were Afraid to GoogleFrom EverandEverything You Always Wanted to Know About Information Literacy But Were Afraid to GoogleNo ratings yet

- At A Loss For Words PrintableDocument31 pagesAt A Loss For Words PrintablejessicaNo ratings yet

- Samb rr1Document6 pagesSamb rr1api-280552667No ratings yet

- Motivating Year 4 Pupils To Read English Materials by Using Comic Strips and CartoonsDocument9 pagesMotivating Year 4 Pupils To Read English Materials by Using Comic Strips and CartoonsMashitah Abdul HalimNo ratings yet

- Community of Readers - Josh YargeauDocument2 pagesCommunity of Readers - Josh Yargeauapi-606946402No ratings yet

- Thesis Student Reading BehaviorDocument30 pagesThesis Student Reading Behavior达华林0% (1)

- MMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsDocument28 pagesMMSD Classroom Action Research Vol. 2010 Adolescent Literacy InterventionsAulia DhichadherNo ratings yet

- Polizzi - Action Research ProjectDocument21 pagesPolizzi - Action Research Projectapi-322025855No ratings yet

- Ela Framing StatementDocument6 pagesEla Framing Statementapi-722424133No ratings yet

- The Importance of Recreational Reading and Its Impact On ChildreDocument48 pagesThe Importance of Recreational Reading and Its Impact On ChildreNemwel Quiño CapolNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument5 pagesResearch Proposalapi-302049524100% (1)

- Emma Laplante - Aoi FinalDocument11 pagesEmma Laplante - Aoi Finalapi-676039012No ratings yet

- Finalproject KBJ 595Document4 pagesFinalproject KBJ 595api-287495514No ratings yet

- Project RWLS G4Document7 pagesProject RWLS G4Nadiyya Anis khairaniNo ratings yet

- Cover LetterDocument19 pagesCover Letterapi-754356903No ratings yet

- Education 580 Artifact DescriptionDocument5 pagesEducation 580 Artifact Descriptionapi-304529596No ratings yet

- 6th Grade Reading Interest SurveyDocument6 pages6th Grade Reading Interest Surveyapi-385553468No ratings yet

- Reading Engagement Opportunities of Education StudentsDocument12 pagesReading Engagement Opportunities of Education Studentskai manNo ratings yet

- Rachel Upholzer Matc SynthesisDocument11 pagesRachel Upholzer Matc Synthesisapi-235502348No ratings yet

- gs02 Final Reflection 2Document15 pagesgs02 Final Reflection 2api-301814394No ratings yet

- Motivation For Content ReadersDocument29 pagesMotivation For Content Readersjena21885100% (1)

- Improving Reading Skills ThroughDocument8 pagesImproving Reading Skills ThroughKanwal RasheedNo ratings yet

- History As A Hands-On Subject 1Document9 pagesHistory As A Hands-On Subject 1api-644512636No ratings yet

- Final PaperDocument18 pagesFinal Paperapi-339236484No ratings yet

- The Teaching of Literature PDFDocument6 pagesThe Teaching of Literature PDFReyna Ediza Adelina EstremosNo ratings yet

- The Teaching of LiteratureDocument6 pagesThe Teaching of LiteratureReyna Ediza Adelina EstremosNo ratings yet

- Interest InventoriesDocument7 pagesInterest Inventoriesandrewwilliampalileo@yahoocomNo ratings yet

- Reading Communities:: Why, What and How?Document5 pagesReading Communities:: Why, What and How?Chong Beng LimNo ratings yet

- Following The Headlines ArticleDocument10 pagesFollowing The Headlines Articleapi-262786958No ratings yet

- Cultivating A Love of Reading in StudentsDocument21 pagesCultivating A Love of Reading in StudentsRose Ann DingalNo ratings yet

- Student Teaching Final ReflectionDocument7 pagesStudent Teaching Final Reflectionapi-267622066No ratings yet

- Tita CoryDocument6 pagesTita CoryHERNA PONGYANNo ratings yet

- Lae 3333 Case StudyDocument10 pagesLae 3333 Case Studyapi-273439539No ratings yet

- Ya Literature Past and PresentDocument10 pagesYa Literature Past and Presentapi-296864651No ratings yet

- Unlocking the Schoolhouse Door: Essays on the Misunderstandings of Public EducationFrom EverandUnlocking the Schoolhouse Door: Essays on the Misunderstandings of Public EducationNo ratings yet

- Creel Impact of Assigned ReadingDocument25 pagesCreel Impact of Assigned ReadingAlmas YeskenovNo ratings yet

- Synthesis of ArtifactsDocument9 pagesSynthesis of Artifactsapi-364531747No ratings yet

- Chapter 2!Document19 pagesChapter 2!Costales Fea Franzielle C.No ratings yet

- 1 Running Head: Reading Engagement Activities For BrsDocument16 pages1 Running Head: Reading Engagement Activities For Brsapi-268838543No ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument8 pagesAction Researchapi-490354973No ratings yet

- Case StudyDocument9 pagesCase Studyapi-257634244No ratings yet

- PLC MotivationDocument25 pagesPLC Motivationjschmudlach7No ratings yet

- 3 Reading Needs Assessment and Survey 810Document11 pages3 Reading Needs Assessment and Survey 810elaineshelburneNo ratings yet

- Article ReviewDocument4 pagesArticle Reviewapi-260791658No ratings yet

- Pertaining To Students Interests To Increase ReadingDocument12 pagesPertaining To Students Interests To Increase Readingapi-644240421No ratings yet

- ReadingDocument165 pagesReadingapi-3705112100% (1)

- The Role of Print Media in Educational Development (A Study of Ikorodu High School and Homat Secondary School OdogunyanDocument56 pagesThe Role of Print Media in Educational Development (A Study of Ikorodu High School and Homat Secondary School OdogunyanOffiaNo ratings yet

- Observations at Sunset Park High School Decastro, Daniel Teacher'S College at Columbia UniversityDocument7 pagesObservations at Sunset Park High School Decastro, Daniel Teacher'S College at Columbia UniversitysarahschlessNo ratings yet

- Bridgets Final Synthesis PaperDocument10 pagesBridgets Final Synthesis Paperapi-268999345No ratings yet

- Teaching Philosophy: Dan Zhong HI ED 546 College Teaching Assignment 4-Teaching PhilosophyDocument4 pagesTeaching Philosophy: Dan Zhong HI ED 546 College Teaching Assignment 4-Teaching PhilosophypurezdNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Beginnings: P. Schmidt (1951) - Hitler's Interpreter. London: Heinemann. 1Document3 pagesChapter 1: Beginnings: P. Schmidt (1951) - Hitler's Interpreter. London: Heinemann. 1Ange Joey LauNo ratings yet

- Is This the End of Reading?Document24 pagesIs This the End of Reading?Bayram J Gascot HernandezNo ratings yet

- How To Study and Teaching How To StudyDocument117 pagesHow To Study and Teaching How To StudyHabby Pearson100% (1)

- Courtneeng 495 ThesispaperDocument29 pagesCourtneeng 495 Thesispaperapi-211294917No ratings yet

- A Commonplace Book on Teaching and Learning: Reflections on Learning Processes, Teaching Methods, and Their Effects on Scientific LiteracyFrom EverandA Commonplace Book on Teaching and Learning: Reflections on Learning Processes, Teaching Methods, and Their Effects on Scientific LiteracyNo ratings yet

- CLASS 9 MATERIAL 1238_1243_dt_14032018Document1 pageCLASS 9 MATERIAL 1238_1243_dt_14032018hoguptacmoNo ratings yet

- Classix: Jr. Jr. JRDocument5 pagesClassix: Jr. Jr. JRhoguptacmoNo ratings yet

- DP Unit Plan-Identity by SripalDocument6 pagesDP Unit Plan-Identity by SripalhoguptacmoNo ratings yet

- Fnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj: Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPHDocument1 pageFnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj Fnxurj: Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPH Izdk'Ku LWPHhoguptacmoNo ratings yet

- Perspectives of Two Ethnically Different Preservice Teacher Populations As They Learn About Folk LiteratureDocument19 pagesPerspectives of Two Ethnically Different Preservice Teacher Populations As They Learn About Folk LiteraturehoguptacmoNo ratings yet

- Freedom of PressDocument13 pagesFreedom of PressZainul Abedeen100% (1)

- Grade 8 Lecture q3Document2 pagesGrade 8 Lecture q3XndeirouNo ratings yet

- Ethiopia CultureDocument54 pagesEthiopia CulturegetnetNo ratings yet

- Doc7 - Marketing Refers To Activities A Company Undertakes To Promote The Buying or Selling of A Product or ServiceDocument3 pagesDoc7 - Marketing Refers To Activities A Company Undertakes To Promote The Buying or Selling of A Product or ServicerobertNo ratings yet

- Advertising Management Concepts Theories Research and Trends Manukonda Rabindranath Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesAdvertising Management Concepts Theories Research and Trends Manukonda Rabindranath Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFshawn.clantz119100% (16)

- Outlook India Report (Ashu)Document107 pagesOutlook India Report (Ashu)ashugoyalNo ratings yet

- Course: Diploma in Broadcast Journalism Unit: Media Convergence and Journalism LecturerDocument118 pagesCourse: Diploma in Broadcast Journalism Unit: Media Convergence and Journalism Lecturerkipkemei cyrusNo ratings yet

- 03b-PPRA Public Procurement Rules 2004Document22 pages03b-PPRA Public Procurement Rules 2004Misama NedianNo ratings yet

- Fraudcast NewsDocument238 pagesFraudcast NewsPatrickChalmersNo ratings yet

- Grup 13 Requesting InformationDocument12 pagesGrup 13 Requesting InformationAliffia GanisNo ratings yet

- Paper Transfer PDFDocument270 pagesPaper Transfer PDFcarloadugNo ratings yet

- Functional Styles of The English LanguageDocument6 pagesFunctional Styles of The English LanguageValeria MicleușanuNo ratings yet

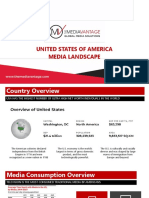

- US Media Landscape 2021Document26 pagesUS Media Landscape 2021M. Waqas AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi On MediaDocument39 pagesMahatma Gandhi On Mediasuryaprakash013No ratings yet

- Olimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 11B PDFDocument6 pagesOlimpiada Engleza 2017 CL A 11B PDFAnthony AdamsNo ratings yet

- B.Ed.S4, P-23, U1, Eng Med.Document30 pagesB.Ed.S4, P-23, U1, Eng Med.Sacred SacredNo ratings yet

- Charlie Munger - Art of Stock PickingDocument18 pagesCharlie Munger - Art of Stock PickingsuniltmNo ratings yet

- Lowubidv IuaerDocument25 pagesLowubidv IuaerTISHANPRAKASH A/L SIVARAJAH MoeNo ratings yet

- Romanian NewspaperDocument2 pagesRomanian NewspaperAnna-Maria DomanNo ratings yet

- News PaperDocument35 pagesNews PaperPramod ZoleNo ratings yet

- What Does Media Do For UsDocument4 pagesWhat Does Media Do For UsfaizanelahiNo ratings yet

- Untitled 1Document4 pagesUntitled 1okello simon peterNo ratings yet

- Media Representations of Immigration in The Chilean Press: To A Different Narrative of Immigration?Document23 pagesMedia Representations of Immigration in The Chilean Press: To A Different Narrative of Immigration?ISMAEL CODORNIU OLMOSNo ratings yet

- EcoPure Business PlanDocument28 pagesEcoPure Business PlanAyieNo ratings yet

- English q4w7d1Document5 pagesEnglish q4w7d1Jo MarNo ratings yet

- AdvertisingDocument9 pagesAdvertisingpecobanNo ratings yet

- Ielts 42 Topics For Speaking Part 1Document32 pagesIelts 42 Topics For Speaking Part 1Zaryab Nisar100% (1)

- Victorias National High School: I. Directions: Read The Questions Carefully and Choose The Letter of The Correct AnswerDocument2 pagesVictorias National High School: I. Directions: Read The Questions Carefully and Choose The Letter of The Correct AnswerGladys CastroNo ratings yet

- Role of TV in National IntegrationDocument8 pagesRole of TV in National IntegrationaleenaahmedNo ratings yet