Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bespreking Cronocaos NY 2011

Bespreking Cronocaos NY 2011

Uploaded by

VIOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bespreking Cronocaos NY 2011

Bespreking Cronocaos NY 2011

Uploaded by

VICopyright:

Available Formats

Review

Author(s): Esther da Costa Meyer

Review by: Esther da Costa Meyer

Source: Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 71, No. 2 (June 2012), pp. 248249

Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the Society of Architectural

Historians

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/jsah.2012.71.2.248

Accessed: 20-01-2016 20:42 UTC

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/

info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content

in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship.

For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Society of Architectural Historians and University of California Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Wed, 20 Jan 2016 20:42:25 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

changing aspects of Burle Marxs (and of

most) landscapes across time, with the

modulation of light and shadow, wind and

sound, and to the timelessness of their

compositions. Aiming to present a holistic

vision of Burle Marxs landscape production, the exhibition touches upon his contributions as an artist, plantsman, and

shaper of urban spaces. Although the

accompanying publicationa translation

of the Brazilian cataloguesheds light on

Burle Marxs perception of native flora and

his interaction with fellow plants collectors and botanists, the same cannot be said

of the exhibition. No commentary accompanied the planting plans exhibited,

whether they listed luscious tropical vegetation or, as in the case of the UNESCO

courtyards, common species. If Burle

Marx is to be viewed as a landscape artist

one in control of the design and natural

environmenthis gardens should not be

merely described as in resonance, harmony, or contrast with architecture, but

also assessed as ecological systems. An

inquiry into the making and sustaining of

Burle Marxs planted tableaux and terrains

would have informed this less-investigated

aspect of his contribution and completed

the narrative of the total designer.

dorothe imbert

Washington University

Related Publication

Lauro Cavalcanti, Fars el-Dahdah, and

Francis Rambert, eds., Roberto Burle Marx:

The Modernity of Landscape, Barcelona:

Actar, 2011, 344 pp., 178 color and 30 b/w

illus. $49.95 (paper), ISBN 8492861673

Notes

1. Henry Russell-Hitchcock, Latin American Architecture since 1945 (New York: Arno, 1972) 30, 33, 35.

2. Pietro Maria Bardi, The Tropical Gardens of Burle

Marx (London: Architectural Press, 1964) 1415.

Cronocaos

Biennale, Venice

29 August21 November 2010

New Museum, New York

7 May5 June 2011

Managing change is an ongoing challenge

for citiesand architectsaround the

248 j s a h

world. As some of our megalopolises

exceed populations of 35 million through

conurbation, they must learn how to deal

with aging historical cores that have so

often been frozen into inert museum

pieces. At the same time, ever-increasing

numbers of modernist buildings fall prey

to the wrecking ball. Preservation of the

past and destruction of the newthe time

warp invoked by the titleare at the heart

of Cronocaos, curated by Rem Koolhaas

and Shohei Shigematsu from the Office

for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA),

and staged first at the Venice Biennale in

2010 and then at the New Museum in

New York in 2011. The issues it raises are

timely and provocative, as we have come

to expect of Koolhaas. Cleverly installed

in New York in a decrepit building in the

Bowery, the show used plan and elevation

to contrast different strategies of preservation and conservation and question

received ideas on these topics.

In this exhibition, preservation appears

largely as a destructive force that embalms

our historic centers, deprives them of use

value, and packages them for consumption. We are all too familiar with the

dreary commercial zones where old buildings have been restored only to house the

ubiquitous franchises that transform historic downtowns into pedestrian strip

malls. The same uncritical tendency is

used to justify buildings veneered with

historic faades that conceal the gutted

structures behind. There is no doubt that

preservation has often been instrumentalized as a profit-making ploy that sells its

reified products to a mass public: the

administered past. However, preservation

covers a much wider range of practices

than is acknowledged here and can be

prompted by complex and legitimate moti

vations including issues of self-identity,

loss, or violence. Cultural genocide, a

tragic presence in our modern world, triggers a deep-seated impulse to preserve

what remains of a heritage threatened with

extinction. From the Bridge at Mostar to

the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, our

age has seen its share of wanton destruction of monuments of world significance.

As for the pervasive misuse of preservation, we must look for causes and not content ourselves with denouncing effects.

Disenchantment with the affectless architecture that stamps streets and cities with

banality, fears of being swallowed up in a

metropolitan sprawl increasingly defined

by synchronic sameness rather than diachronic difference are some of the concerns that strengthen the drive to retain

the past. That past, of course, is never a

given: it is always being constructedor

inventedpressured by contemporary

events. Historic landmarks are unstable

referents subject to both genuine change

and manipulation. Extant old buildings do

not speak to us solely through the debased

language of commodification.

In their sweeping indictment of preservation, the curators make the astonishing

assertion, unsubstantiated by sources, that

at present 12 percent of the worlds surface is preserved, a figure, we are told, that

is about to undergo a massive increase.

Given the fact that 71 percent of the globes

surface is covered by water, this would

mean that the equivalent of almost half of

our landmass is currently covered by historic preservation, a questionable sum

even if it includes environmental zones on

land or sea. Cronocaos, however, aims at

stimulating discussion, not attaining closure, and it abounds in contradictions and

refreshing Rashomon-like scenarios.

A second important topic pursued by

Cronocaos, which seems, almost perversely,

to negate the first, concerns the need to

protect postwar architecture under siege

by what the organizers see as a global

rage to destroy modern buildings. In this

case, the curators indulge in special pleading on behalf of preservation. But this

position is deliberately undercut by a contrasting proposal: the systematic demolition of all modern buildings erected fifty

years ago to make way for new construction and avoid the rigor mortis of heritage

sites. Cities like Istanbul, Tokyo, Moscow,

and Chicago, for example, would demolish

that same postwar architecture that they

think is threatened by imminent ruin.

Outlandish proposals such as this do a real

service to the field: Koolhaas is always

ready to think the unthinkable and jolt us

out of our complacency.

Yet another idea along these lines,

inspired by carbon trading, speculates about

whether one industrious nation might forge

/ 7 1 : 2 , j u n e 2 01 2

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Wed, 20 Jan 2016 20:42:25 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ahead, whatever the cost to its historic past,

and pay for preservation elsewhere. This

is audacious: we desperately need to think of

new alternatives to deal with the past. But

the terms in which this suggestion is

couched are chilling: Could backwardness

become a resource, like Costa Ricas rainforest? Should China save Venice? Why

should the heritage of one of the worlds

oldest civilizations be sacrificed to save a

single European city? This argument falls

back on essentialist conceptions of nationhood that ask the East and the Global South

to indemnify the west yet again.

Cronocaos also perpetuates stereotypes

concerning gender. One panel shows the

architects featured on the cover of Time:

Buckminster Fuller, Wright, Neutra, and

Le Corbusier, among many others (Zaha

Hadid, named by Time as one of the

worlds one hundred most influential people in 2010, is not mentioned). In this

exhibition, women shine by their absence,

and architecture is narrowly construed as

a noble male pursuit. At first sight, the

show appears to be predicated on a maddeningly messianic conception of the

hero-architect (Architectswe who

change the world), and the public is

expected to take everything on faith: maps,

arguments, figures (like that 12 percent).

In fact, the words and images reveal an

aching nostalgia for the good old days

when this obsolescent concept of the

architect received even greater recognition and representatives of the profession

like Philip Johnson appeared on the cover

of the corporate media magazines: By

disconnecting (the role of the architect)

from the public sector, the market economy severed the connection between

architecture and idealism and condemned

the contemporary architect to a limbo of

lesser seriousness. In this formulation,

those who change the world appear

strangely passive, at the command of

forces they cannot control. Conveniently

displacing blame to the market economy

exonerates architects from decisionmaking. They, after all, choose their

patrons, including (in Koolhaas/OMAs

case) luxury labels like Prada or unelected

authorities in Beijing. Cronocaos bristles

with ideassmall, medium, large, and

extra-largebut its wall texts rely too

often on reductive dichotomies that foreclose the possibility of a more nuanced

dialectical approach. A weary subtext runs

in counterpoint to stimulating insights,

recycling old chestnuts that preserve the

status quo while preaching destruction of

historic or even modern buildings that it

treats as fungible structures.

Koolhaass tone is that of a detached

observer who speaks for the common good,

but as one of architectures most important

cultural brokers, he is far from being a disinterested protagonist. This unusually successful practitioner, actively involved in all

sides of this debate, is at his best as our

iconoclast-in-chief; we need him to unsettle certainties, revisit dogmas, up-end theories, and interpellateeven irritatethe

institution of architecture. We would do

him a disservice if we allowed this initiative

to go by without challenging him in turn.

esther da costa meyer

Princeton University

The Houses of William Wurster:

Frames for Living

Wurster Gallery, University of California, Berkeley

30 September15 November 2011

Crossing into Wurster Hall on the University of California, Berkeley campus,

the path to the Wurster Gallery branches

under a staircase and skirts a couple of

bathrooms. By this point, the ponderous

concrete building, designed by Joseph

Esherick, Vernon DeMars, and Donald

Olsen in 1964, the year after William

Wurster retired as dean of the College of

Environmental Design at Berkeley, has

extinguished natural light or the sight of

nature. Gallery visitors find themselves in

a room floored by linoleum, framed by

white drywall, topped by black-painted

concrete, and occupied by mechanical

equipment and a grid of thin fluorescent

filaments. Such a space would doubtless

have defeated the best efforts of Wurster,

the architect, to create a rapport with its

site. Thankfully, the exhibits curators,

Richard C. Peters and Caitlin Lempres

Brostrom, have splashed the gallery so thoroughly with photographs of Wursters

houses that visitors quickly find themselves

contemplating architectural form and

space alongside Northern Californias

coulisses of dark trees, rocky coasts, and

mountain escarpments.

The curators divided the smallish 25-by50-foot space into three parts: an entry zone

introducing the scope of the exhibit and

background on Wursters Stockton childhood and training as an architect in the

beaux-arts tradition at Berkeley; a prominent mid-section documenting the houses;

and a rear area providing a couple of panels

on the non-residential highlights of Wursters own practice, such as the Schuckl

Cannery Offices (Sunnyvale, California,

194142), his practice at Wurster, Bernardi

& Emmons, and his career as an educator

at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and at Berkeley. On the back wall,

photographs show Wurster and his wife

Catherine Bauer and their family, as well

as other architects such as Thomas Church

and photographers such as Morley Baer.

Not surprisingly for an exhibition of

architectural photographs, this is the only

place in the room where we see images of

people.

Out of approximately two hundred

houses designed by the architect, we are

shown the highlightsa little more than a

score of buildings from the late 1920s

through the early 1960s. Illustrations of

fifteen of the most illustrious of them

appear on freestanding, two-sided panels

(held aloft by metal stanchions) that

occupy the middle of the gallery. The panels are smartly divided into grids of differently sized rectangles. At the top right, red

letters announce the houses name and

year and are followed by descriptive wall

text. Aside from one or two drawn plans or

perspective renderings, photographs carry

the weight of depicting Wursters epic

engagement with the California landscape. Among the many images, it is rare

to find one bereft of an exterior view.

Black-and-white shots, usually taken

shortly after the houses completion, alternate with recent color photographs by

Lempres Brostrom or others, including

Richard Barnes. Set against Wursters

muted whitish or brownish building

colors, the chromatic contrast works particularly well; sensations of California

dominated by deep blue skies and a wide

e x h i b i t i o n s

This content downloaded from 134.58.253.30 on Wed, 20 Jan 2016 20:42:25 UTC

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

249

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5824)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hayagriva Most Secret Long SadhanaDocument51 pagesHayagriva Most Secret Long SadhanaSezgin Alişoğlu88% (8)

- 3-Christs Different SourceDocument5 pages3-Christs Different SourceEl-Elohei Yeshua Jesheua100% (4)

- The Enlisted Force StructureDocument23 pagesThe Enlisted Force StructurestraightshooterNo ratings yet

- Wölfflin - Problem Stil 1911Document4 pagesWölfflin - Problem Stil 1911VINo ratings yet

- Simmel - RomeDocument8 pagesSimmel - RomeVINo ratings yet

- SIMMEL - FlorenceDocument4 pagesSIMMEL - FlorenceVINo ratings yet

- KOOLHAAS 2013 New Perspectives QuarterlyDocument7 pagesKOOLHAAS 2013 New Perspectives QuarterlyVI100% (1)

- Koolhaas - Cronocaos in LogDocument5 pagesKoolhaas - Cronocaos in LogVINo ratings yet

- RPT Add Math Form 5Document9 pagesRPT Add Math Form 5Suziana MohamadNo ratings yet

- Bihar CollageDocument48 pagesBihar CollageSuraj SinghNo ratings yet

- ICAR IARI Assistant Exam Syllabus ICAR IARI Assistant Exam Syllabus ICAR IARI Assistant Exam SyllabusDocument3 pagesICAR IARI Assistant Exam Syllabus ICAR IARI Assistant Exam Syllabus ICAR IARI Assistant Exam SyllabusAbhishek VermaNo ratings yet

- 10 Accident InvestigationDocument9 pages10 Accident InvestigationEris John Peletina DomingoNo ratings yet

- Severity Rating ScalesDocument7 pagesSeverity Rating ScalesCerasela Daniela BNo ratings yet

- NLP GlossaryDocument11 pagesNLP Glossaryandapanda1100% (1)

- Advanced GeometryDocument7 pagesAdvanced GeometryGenelle Mae MadrigalNo ratings yet

- Dr. Mikao UsuiDocument1 pageDr. Mikao Usuinickdegler100% (1)

- Heading A Soccer Ball Can Injure BrainDocument9 pagesHeading A Soccer Ball Can Injure BrainThao NguyenNo ratings yet

- ZTE WCDMA NPO Primary02-200711 WCDMA Radio Network Planning and OptimizationDocument277 pagesZTE WCDMA NPO Primary02-200711 WCDMA Radio Network Planning and OptimizationIndrasto JatiNo ratings yet

- Curriculam Vitae S.Heena: ObjectivesDocument3 pagesCurriculam Vitae S.Heena: Objectivesvizay237_430788222No ratings yet

- Understanding Gadamer and The Hermeneutic CircleDocument6 pagesUnderstanding Gadamer and The Hermeneutic CircleduaneNo ratings yet

- Raymond J. Corsini - Handbook of Innovative Therapy, Second Edition (Wiley Series On Personality Processes) (2001) PDFDocument764 pagesRaymond J. Corsini - Handbook of Innovative Therapy, Second Edition (Wiley Series On Personality Processes) (2001) PDFFelipe Concha Aqueveque100% (3)

- Psychology and Criminal Behaviour Definitions1Document24 pagesPsychology and Criminal Behaviour Definitions1YunusNo ratings yet

- INFOSYS GRAND TEST-3-verbalDocument4 pagesINFOSYS GRAND TEST-3-verbalsaieswar4uNo ratings yet

- Diss Quarter 2 Hand OutsDocument5 pagesDiss Quarter 2 Hand OutsMary Baluca100% (1)

- Khajuraho-The Erotic Temples Group in IndiaDocument8 pagesKhajuraho-The Erotic Temples Group in IndiaHidden Treasures of IndiaNo ratings yet

- Martin Stokes, The Republic of Love. Cultural Intimacy in Turkish Popular MusicDocument3 pagesMartin Stokes, The Republic of Love. Cultural Intimacy in Turkish Popular Musicnicoleta5aldeaNo ratings yet

- 3.5 ArchimedesDocument16 pages3.5 ArchimedessheyzulkifliNo ratings yet

- PHD Writing Template AW 2020 V3Document1 pagePHD Writing Template AW 2020 V3Alexandru INo ratings yet

- @enmagazine 2019-01-01 Teen Breathe PDFDocument68 pages@enmagazine 2019-01-01 Teen Breathe PDFSheila Jamil100% (2)

- Classics Catalogue 2012Document36 pagesClassics Catalogue 2012bella_williams7613No ratings yet

- AssignmentDocument4 pagesAssignmentKhyzer HayyatNo ratings yet

- Super Banana OrbitDocument4 pagesSuper Banana OrbitWill CunninghamNo ratings yet

- Pioneers of Photography (Art Ebook)Document196 pagesPioneers of Photography (Art Ebook)Vinit Gupta100% (3)

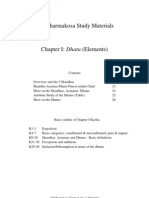

- Chapter 1 DhatuDocument6 pagesChapter 1 Dhatusbec96860% (1)

- 1 - 23 and 1 - 25 KleinmanDocument19 pages1 - 23 and 1 - 25 KleinmanLeilaVoscoboynicovaNo ratings yet