Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

Uploaded by

outdash2Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Talal Asad - Anthropology and The Colonial EncounterDocument4 pagesTalal Asad - Anthropology and The Colonial EncounterTania Saha100% (1)

- Melting Bone, Healing Tide: How to Reanimate Inertial Bone Tissue Through Therapeutic TouchFrom EverandMelting Bone, Healing Tide: How to Reanimate Inertial Bone Tissue Through Therapeutic TouchRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Research Ethics in The Arab WorldDocument390 pagesResearch Ethics in The Arab Worldnaghalfatih0% (1)

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommDocument5 pagesLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2No ratings yet

- Modern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah LererDocument4 pagesModern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah Lereroutdash2No ratings yet

- Scientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranDocument5 pagesScientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranMuhammad Zaheer IqbalNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same PathDocument17 pagesOrgan Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same Pathabduh_hafidzNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana KohanchiDocument3 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana Kohanchioutdash2No ratings yet

- The Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsDocument2 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsJoel Alan KatzNo ratings yet

- Kidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara KaszovitzDocument2 pagesKidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara Kaszovitzoutdash2No ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Jewish Bioethical Perspectives On The Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells and CloningDocument17 pagesJewish Bioethical Perspectives On The Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells and Cloningoutdash2No ratings yet

- Goup 6 EuthansiaDocument16 pagesGoup 6 EuthansiaAmalNo ratings yet

- Scientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranDocument5 pagesScientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranShadab AnjumNo ratings yet

- Other Bioethical IssuesDocument5 pagesOther Bioethical Issuesapi-247725573No ratings yet

- WholismDocument8 pagesWholismDayal nitaiNo ratings yet

- National Organ Donation Day: TH THDocument4 pagesNational Organ Donation Day: TH THFirasha ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics Assignment (SP18-BSO-101)Document5 pagesMedical Ethics Assignment (SP18-BSO-101)Tausif IqbalNo ratings yet

- f80261ca-443f-49c5-9df6-a3645a7d0669Document13 pagesf80261ca-443f-49c5-9df6-a3645a7d0669Nour Mohamed0% (1)

- Postmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachDocument3 pagesPostmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal Auerbachoutdash2No ratings yet

- Eng Organ Don Essay 2Document3 pagesEng Organ Don Essay 2api-285146170No ratings yet

- Trans HalachaDocument30 pagesTrans HalachaaokoyeNo ratings yet

- JOSEPH - MERLIN - Discuss The Social, Ethical and Legal Issues Related To Human Organ TransplantationDocument11 pagesJOSEPH - MERLIN - Discuss The Social, Ethical and Legal Issues Related To Human Organ TransplantationMerlinNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Prenatal Development From The Sunnah and Contemporary PsychologyDocument17 pagesFactors Affecting Prenatal Development From The Sunnah and Contemporary PsychologyTahir NazirNo ratings yet

- English Persuasive Essay TopicsDocument6 pagesEnglish Persuasive Essay TopicsaerftuwhdNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesOrgan Transplant Thesis Statementafcmayfzq100% (2)

- Hadith Presentation-hedaya Public FinalDocument303 pagesHadith Presentation-hedaya Public Finalmohommadgouse297.mgNo ratings yet

- Some Observations On Buddhist Thoughts On Human Cloning (Schlieter 2004)Document24 pagesSome Observations On Buddhist Thoughts On Human Cloning (Schlieter 2004)Naljorpa ChagmedNo ratings yet

- Re HWDocument1 pageRe HWJames Siva KumarNo ratings yet

- Biting The Bullet! A Discursive Approach Analysis of Masculinity in The Reproductive Health ClinicDocument8 pagesBiting The Bullet! A Discursive Approach Analysis of Masculinity in The Reproductive Health ClinicIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Scientists On The QuranDocument15 pagesScientists On The QuranMohammed faisalNo ratings yet

- ETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoDocument10 pagesETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoEvang G. I. IsongNo ratings yet

- End of Life Issues: For Technical Information Regarding Use of This Document, Press CTRL andDocument22 pagesEnd of Life Issues: For Technical Information Regarding Use of This Document, Press CTRL andoutdash2No ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Postmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachDocument3 pagesPostmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachssNo ratings yet

- Syed Muhammad Zuhair S.E EE-171 D Elevtrical Engg.: DepartmentDocument17 pagesSyed Muhammad Zuhair S.E EE-171 D Elevtrical Engg.: DepartmentSyed Muhammad ZohairNo ratings yet

- Isu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamDocument91 pagesIsu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamKhairul AzlyNo ratings yet

- Human Embryonic Stem Cell ResearchDocument7 pagesHuman Embryonic Stem Cell Researchapi-287743787No ratings yet

- A Discursive Analysis of Imperatives in The BibleDocument9 pagesA Discursive Analysis of Imperatives in The BibleJohn Michael Barrosa SaturNo ratings yet

- الهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةDocument115 pagesالهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةIslamHouseNo ratings yet

- Fatwas and Surgery How and Why A Fatwa MDocument6 pagesFatwas and Surgery How and Why A Fatwa MOmar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- The Modernity of Dongui Bogam: October 2013Document10 pagesThe Modernity of Dongui Bogam: October 2013Quỳnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Dental Traumatology - 2022 - Lin - Tooth Resorption Part 1 The Evolvement Rationales and Controversies of ToothDocument14 pagesDental Traumatology - 2022 - Lin - Tooth Resorption Part 1 The Evolvement Rationales and Controversies of ToothJavRojNo ratings yet

- الهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةDocument113 pagesالهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةIslamHouseNo ratings yet

- Intro To IslamDocument6 pagesIntro To IslamMuhammad Uzair BSSE2021No ratings yet

- Centric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfDocument3 pagesCentric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfManuel CastilloNo ratings yet

- RKUD2230General PerspectiveDocument27 pagesRKUD2230General Perspectivesyamimi ramlyNo ratings yet

- Ijmaa, Ihtihaad and QiyaassDocument5 pagesIjmaa, Ihtihaad and QiyaassUrgunoon Saleem KhanNo ratings yet

- Essay On Bill of RightsDocument4 pagesEssay On Bill of Rightseikmujnbf100% (1)

- Human Embryology, Research and EthicsDocument42 pagesHuman Embryology, Research and EthicsnorjannahhassanNo ratings yet

- Centric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfDocument3 pagesCentric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfjoaompradoNo ratings yet

- Sefotho Exploration 2016Document16 pagesSefotho Exploration 2016Thabiso EdwardNo ratings yet

- Tehillim Psalms For Special Occasions PDFDocument20 pagesTehillim Psalms For Special Occasions PDFSeth KunchebeNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionDocument19 pagesFundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionYoel Ben-AvrahamNo ratings yet

- Osteo - and Funerary Archaeology - The Influence of TaphonomyDocument12 pagesOsteo - and Funerary Archaeology - The Influence of TaphonomyLucas RossiNo ratings yet

- Temporary Marriage - A Possible Solution To The PRDocument44 pagesTemporary Marriage - A Possible Solution To The PRYann VecNo ratings yet

- Kosher Fat: Mony Almalech (NBU)Document47 pagesKosher Fat: Mony Almalech (NBU)HECTOR ORTEGANo ratings yet

- Transplantation-Ethical IssuesDocument17 pagesTransplantation-Ethical IssuesivkovictNo ratings yet

- Healing Secrets in Holy QuranDocument24 pagesHealing Secrets in Holy QuranSyed AhamedNo ratings yet

- Answers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationDocument2 pagesAnswers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationbrownieallennNo ratings yet

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Document4 pagesParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2No ratings yet

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterDocument3 pagesConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2No ratings yet

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 pagesChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879510Document14 pages879510outdash2No ratings yet

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonDocument3 pagesThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Document4 pagesThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelDocument2 pagesThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanDocument6 pagesPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2No ratings yet

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelDocument3 pagesWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzDocument2 pagesFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2No ratings yet

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 pagesShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2No ratings yet

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosDocument3 pagesReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2No ratings yet

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessDocument3 pagesLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2No ratings yet

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersDocument2 pagesI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauDocument3 pagesThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2No ratings yet

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelDocument2 pagesChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerDocument3 pagesExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2No ratings yet

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelDocument52 pagesTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelDocument2 pagesKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Document16 pagesJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2No ratings yet

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisDocument1 pageYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2No ratings yet

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitDocument1 pageNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2No ratings yet

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassDocument3 pagesA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879446Document5 pages879446outdash2No ratings yet

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelDocument5 pagesWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 pagesChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2No ratings yet

- Appreciating Moses' GreatnessDocument4 pagesAppreciating Moses' Greatnessoutdash2No ratings yet

- Eastron Electronic Co., LTDDocument2 pagesEastron Electronic Co., LTDasd qweNo ratings yet

- Glass Configurator Datasheet 2023 03 27Document1 pageGlass Configurator Datasheet 2023 03 27Satrio PrakosoNo ratings yet

- Teacher: Diana Marie V. Aman Science Teaching Dates/Time: Quarter: SecondDocument6 pagesTeacher: Diana Marie V. Aman Science Teaching Dates/Time: Quarter: SecondDiana Marie Vidallon AmanNo ratings yet

- DSF Course Curriculum 1305231045Document8 pagesDSF Course Curriculum 1305231045Gaurav BhadaneNo ratings yet

- Application of Buoyancy-Power Generator For Compressed Air Energy Storage Using A Fluid-Air Displacement System - ScienceDirectDocument7 pagesApplication of Buoyancy-Power Generator For Compressed Air Energy Storage Using A Fluid-Air Displacement System - ScienceDirectJoel Stanley TylerNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Past Paper QuestionsDocument174 pagesMathematics Past Paper Questionsnodicoh572100% (2)

- Emmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and TimeDocument308 pagesEmmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and Timeissamagician100% (3)

- 3700 S 24 Rev 0 ENDocument3 pages3700 S 24 Rev 0 ENJoão CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Report 1Document9 pagesReport 135074Md Arafat Khan100% (1)

- Cost Leadership Porter Generic StrategiesDocument7 pagesCost Leadership Porter Generic StrategiesRamar MurugasenNo ratings yet

- Shahetal.2022 TecGeomorpJhelumDocument21 pagesShahetal.2022 TecGeomorpJhelumAyesha EjazNo ratings yet

- Rear Drive Halfshafts: 2016.0 RANGE ROVER (LG), 205-05Document46 pagesRear Drive Halfshafts: 2016.0 RANGE ROVER (LG), 205-05SergeyNo ratings yet

- 3M CorporationDocument3 pages3M CorporationIndoxfeeds GramNo ratings yet

- Feasibility of Ethanol Production From Coffee Husks: Biotechnology Letters June 2009Document6 pagesFeasibility of Ethanol Production From Coffee Husks: Biotechnology Letters June 2009Jher OcretoNo ratings yet

- Whittington 22e Solutions Manual Ch14Document14 pagesWhittington 22e Solutions Manual Ch14潘妍伶No ratings yet

- Eng Pedagogy Class CTETDocument33 pagesEng Pedagogy Class CTETntajbun13No ratings yet

- SPE 163723 Pressure Transient Analysis of Data From Permanent Downhole GaugesDocument24 pagesSPE 163723 Pressure Transient Analysis of Data From Permanent Downhole GaugesLulut Fitra FalaNo ratings yet

- FermentationDocument23 pagesFermentationr_bharathi100% (2)

- Fundamentals of HydraulicsDocument101 pagesFundamentals of HydraulicswissamhijaziNo ratings yet

- Acute Gynaecological Emergencies-1Document14 pagesAcute Gynaecological Emergencies-1Anivasa Kabir100% (1)

- DMX DC Motor ControllerDocument23 pagesDMX DC Motor ControlleromargarayNo ratings yet

- In Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloDocument112 pagesIn Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Name:: Nyoman Gede Abhyasa Class: X Mipa 2 Absent: 25 AnswersDocument2 pagesName:: Nyoman Gede Abhyasa Class: X Mipa 2 Absent: 25 AnswersRetrify - Random ContentNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument4 pagesNursing Care PlanPutra AginaNo ratings yet

- BDM SF 3 6LPA 2ndlisDocument20 pagesBDM SF 3 6LPA 2ndlisAvi VatsaNo ratings yet

- Optimal Design of Low-Cost and Reliable Hybrid Renewable Energy System Considering Grid BlackoutsDocument7 pagesOptimal Design of Low-Cost and Reliable Hybrid Renewable Energy System Considering Grid BlackoutsNelson Andres Entralgo MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Form 137Document2 pagesForm 137Raymund BondeNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Fauzi-855677765-Fizz Hotel Lombok-HOTEL - STANDALONEDocument1 pageMuhammad Fauzi-855677765-Fizz Hotel Lombok-HOTEL - STANDALONEMuhammad Fauzi AndriansyahNo ratings yet

- Optimizing The Lasing Quality of Diode Lasers by Anti-Reflective CoatingDocument21 pagesOptimizing The Lasing Quality of Diode Lasers by Anti-Reflective CoatingDannyNo ratings yet

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

Uploaded by

outdash2Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

A Tooth For A Tooth: Not So Easy For Cohanim: Shiller

Uploaded by

outdash2Copyright:

Available Formats

A Tooth for a Tooth: Not So Easy for Cohanim

There is a clear history of false teeth and an emphasis of

dental aesthetics throughout Jewish literature. In Judaism,

teeth are viewed as an essential part of the body, just as

important as an eye. The pasuk (Exodus 21:23-24) states if

there is a fatality, you shall give a life for a life; an eye for

an eye, a tooth for a tooth, where the phrase a tooth for

a tooth is parallel to an eye for an eye [1]. Teeth were

even viewed as essential for maintaining the health of the

entire body [2]. Cohanim, Jewish priests, have an even

greater imperative to maintain their oral health. If a Cohen

lost a tooth, it was considered a mum, one of the defects

making a Cohen unsuitable to serve in the Temple [3].

There are many other medical restrictions regarding the

issue of tumah, or impurity, involving Cohanim. These

restrictions are due to the prohibition for a Cohen to come

into contact with a dead body. Ironically, a Cohens

obligation to refrain from coming into close proximity with

a dead body may prevent him from using dental implants

as a means to maintain his teeths aesthetics.

Today, most dental implants include cadaver

grafts. This poses an array of issues concerning Cohanim

coming into contact with such materials and could even

prohibit a Cohen from entering a dentists office. One of

the most common dental procedures is tooth extraction,

which is accompanied by tissue scaffolding. Tissue

scaffolding is a bone grafting procedure where a graft is

placed on an area, post-extraction, for stabilization of

surrounding teeth [4].

There are various kinds of scaffolds: (a)

autogenous grafts - living tissue from another area of the

patients body, (b) allografts - a graft of cadaver bone, and

(c) xenografts - tissue from animals, including synthetic

grafts. Most of these grafts, excluding allografts, may cause

harmful host responses, including various immune system

defense mechanisms upon grafting of foreign matter into a

host body. According to halacha, xenografts are most

preferable due to their safer healing period and absence of

impurity issues involving cadavers. However, multiple

advantages have been found using allografts including a

less drastic host response, better bone remodeling, and a

greater penetration of fibroblasts and osteoblasts for bone

renewal [4].

Besides for the issues of tumah (such as being in

the same building, carrying/lifting, and direct physical

contact with a dead body) there are additional halachik

issues that arise regarding the use of allografts. Specifically,

there is a prohibition of nivul hameit, which requires a

Jewish body to be buried intact. The source for this

prohibition is Deuteronomy (21:22-23) which forbids

leaving a body that was executed and hanged to remain

hanging overnight. The Talmud (Sanhedrin 46a-b) adds that

not burying individual body parts would also violate this

prohibition [4]. The main question behind these issues that

DERECH HATEVAH

By Tamar

Shiller

we need to address is whether or not allografts attain the

status of a dead body in the eyes of halacha.

There are several ways to address the posed

halachik barriers. Rabbi Unterman, Ashkenazic Chief Rabbi

of Israel from 1964-73, states that the transplanted organ is

considered to come back to life after transplantation, and

therefore would no longer have the status of dead. This

would allow for parts of a cadaver to be used especially

when benefitting a life, and would not halachikally be

considered desecration of a dead body. The transplanted

area will also eventually be buried with the transplant

recipient when he or she dies, resolving the issue of kevurat

hameit [4].

Regarding tumah and Cohanim, there are areas of

leniency considering the size and source of the bone. While

benefitting from the dead is a debate, benefitting from a

Gentile corpse is only a Rabbinic prohibition (based on

Talmud Yerushalmi, Shabbat 10:6) and may thus allow for

leniency in a case where it is used to benefit the life of

another. Furthermore, most of the bones in bone banks

originated from non-Jews simply because there are fewer

Jews in the world, and thus one can reasonably assume that

the bone graft originated from a non-Jewish corpse.

Halachik consideration of these multiple factors would

allow more leniency for bone graft use on a Cohen [4].

The measurement used to determine an impure

status of an object in the Talmud is the size of a piece of

barley. If the bone size is less than a piece of barley, which

is true for the amounts used in most dental grafts, then it

would not transmit any tumah. When the graft materials

originate from multiple corpses and bone is pulverized, it

does not convey tumah according to the Brisker Rav, Rabbi

Yitzchak Zev Halevi Soloveitchik (Chiddushei HaGriz Vol.5

Nazir 52a). The graft would not transmit tumah because the

ground individual pieces are much smaller than a grain of

barley and the bone is coming from multiple sources.

Additionally, when the bone is dry as flour, it is considered

by the Talmud (Niddah 56a) basar min hameit sheyavesh and

is thus considered tahor (ritually pure) and can be used for a

Cohen [4].

All allografts are treated with multiple solvents and

acids for sterilization to produce a healthy host response

upon transplantation. This changes the form of the bone

and transforms the grafts essence and is therefore not

considered to transmit tumah. Additionally, the pulverized

pieces are not reassembled into their original structure and

the graft now has a changed status, making it tahor and

acceptable to be used on a Cohen [4].

While there is a great amount of debate

concerning this issue among Poskim, many make the case

based on the above arguments that the materials used in

allografts do not have the status of transmitting tumah.

Included in this is the halachik rulings of Rabbi J. David

49

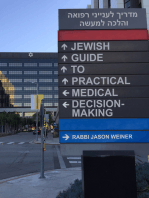

Bleich, Rabbi Moshe D. Tendler, and Rav Asher Weiss

(among others). Rabbi Dovid Feinstein and Rav Yisroel

Belsky say that it is permissible for a Cohen patient, but a

Cohen dentist must take certain precautions. The specific

conditions of their pesak can be read in the article by Rabbi

Dr. David J. Katz [4]. Practically, this relieves the issues of

tumah/tahara regarding a Cohen acting as a dental

practitioner, entering the office of a dentist, or receiving an

allograft treatment [4].

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my parents for their constant support

throughout my education. I would also like to thank Dr.

Babich who inspired me to write this article and helped me

with sources throughout the writing process. I would also

like to thank Rabbi Binyamin Blau and Rabbi Benjamin

Shiller for helping me review the halachik content as well as

providing insightful feedback.

References

[1] Rosner, F. (1994). Dentistry in the Bible, Talmud, and

Writings of Moses Maimonides. Bull. Hist. Dent.

42:109-112.

[2] Davidson, M. (1983). Ancient References to Dentistry

and Biblical Bites. Bull. Hist. Dent. 31:30-31.

50

[3] Stern, N. (1996). Prosthodontics-from Craft to

Science. J. Hist. Dent. 44:73-76.

[4] Katz, D. (2011). Halachik Considerations in the Use

of Biologic Scaffolding Materials. Bone Grafts. J.

Halacha Contemp. Soc. 63:55-82.

DERECH HATEVAH

You might also like

- Talal Asad - Anthropology and The Colonial EncounterDocument4 pagesTalal Asad - Anthropology and The Colonial EncounterTania Saha100% (1)

- Melting Bone, Healing Tide: How to Reanimate Inertial Bone Tissue Through Therapeutic TouchFrom EverandMelting Bone, Healing Tide: How to Reanimate Inertial Bone Tissue Through Therapeutic TouchRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Research Ethics in The Arab WorldDocument390 pagesResearch Ethics in The Arab Worldnaghalfatih0% (1)

- Lessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi RommDocument5 pagesLessons Learned From Conversion: Rabbi Zvi Rommoutdash2No ratings yet

- Modern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah LererDocument4 pagesModern Miracles: Surgery in The Talmud and Today: Rikah Lereroutdash2No ratings yet

- Scientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranDocument5 pagesScientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranMuhammad Zaheer IqbalNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same PathDocument17 pagesOrgan Transplant in Islam, Two Roads of The Same Pathabduh_hafidzNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana KohanchiDocument3 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ Transplantations: Eliana Kohanchioutdash2No ratings yet

- The Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsDocument2 pagesThe Jewish Stance On Organ TransplantationsJoel Alan KatzNo ratings yet

- Kidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara KaszovitzDocument2 pagesKidney Donation: It's Complicated: Sara Kaszovitzoutdash2No ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Jewish Bioethical Perspectives On The Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells and CloningDocument17 pagesJewish Bioethical Perspectives On The Therapeutic Use of Stem Cells and Cloningoutdash2No ratings yet

- Goup 6 EuthansiaDocument16 pagesGoup 6 EuthansiaAmalNo ratings yet

- Scientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranDocument5 pagesScientists' Comments On The Scientific Miracles in The Holy QuranShadab AnjumNo ratings yet

- Other Bioethical IssuesDocument5 pagesOther Bioethical Issuesapi-247725573No ratings yet

- WholismDocument8 pagesWholismDayal nitaiNo ratings yet

- National Organ Donation Day: TH THDocument4 pagesNational Organ Donation Day: TH THFirasha ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Medical Ethics Assignment (SP18-BSO-101)Document5 pagesMedical Ethics Assignment (SP18-BSO-101)Tausif IqbalNo ratings yet

- f80261ca-443f-49c5-9df6-a3645a7d0669Document13 pagesf80261ca-443f-49c5-9df6-a3645a7d0669Nour Mohamed0% (1)

- Postmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachDocument3 pagesPostmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal Auerbachoutdash2No ratings yet

- Eng Organ Don Essay 2Document3 pagesEng Organ Don Essay 2api-285146170No ratings yet

- Trans HalachaDocument30 pagesTrans HalachaaokoyeNo ratings yet

- JOSEPH - MERLIN - Discuss The Social, Ethical and Legal Issues Related To Human Organ TransplantationDocument11 pagesJOSEPH - MERLIN - Discuss The Social, Ethical and Legal Issues Related To Human Organ TransplantationMerlinNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Prenatal Development From The Sunnah and Contemporary PsychologyDocument17 pagesFactors Affecting Prenatal Development From The Sunnah and Contemporary PsychologyTahir NazirNo ratings yet

- English Persuasive Essay TopicsDocument6 pagesEnglish Persuasive Essay TopicsaerftuwhdNo ratings yet

- Organ Transplant Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesOrgan Transplant Thesis Statementafcmayfzq100% (2)

- Hadith Presentation-hedaya Public FinalDocument303 pagesHadith Presentation-hedaya Public Finalmohommadgouse297.mgNo ratings yet

- Some Observations On Buddhist Thoughts On Human Cloning (Schlieter 2004)Document24 pagesSome Observations On Buddhist Thoughts On Human Cloning (Schlieter 2004)Naljorpa ChagmedNo ratings yet

- Re HWDocument1 pageRe HWJames Siva KumarNo ratings yet

- Biting The Bullet! A Discursive Approach Analysis of Masculinity in The Reproductive Health ClinicDocument8 pagesBiting The Bullet! A Discursive Approach Analysis of Masculinity in The Reproductive Health ClinicIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Scientists On The QuranDocument15 pagesScientists On The QuranMohammed faisalNo ratings yet

- ETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoDocument10 pagesETHICS OF ORGAN DONATION - Part TwoEvang G. I. IsongNo ratings yet

- End of Life Issues: For Technical Information Regarding Use of This Document, Press CTRL andDocument22 pagesEnd of Life Issues: For Technical Information Regarding Use of This Document, Press CTRL andoutdash2No ratings yet

- Organ DonationDocument11 pagesOrgan DonationJakmensar Dewantara SiagianNo ratings yet

- Postmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachDocument3 pagesPostmortem Sperm Insemination: A Halachic Survey: Michal AuerbachssNo ratings yet

- Syed Muhammad Zuhair S.E EE-171 D Elevtrical Engg.: DepartmentDocument17 pagesSyed Muhammad Zuhair S.E EE-171 D Elevtrical Engg.: DepartmentSyed Muhammad ZohairNo ratings yet

- Isu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamDocument91 pagesIsu-Isu Kesihatan Terkini Dan Penyelesaiannya Menurut IslamKhairul AzlyNo ratings yet

- Human Embryonic Stem Cell ResearchDocument7 pagesHuman Embryonic Stem Cell Researchapi-287743787No ratings yet

- A Discursive Analysis of Imperatives in The BibleDocument9 pagesA Discursive Analysis of Imperatives in The BibleJohn Michael Barrosa SaturNo ratings yet

- الهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةDocument115 pagesالهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةIslamHouseNo ratings yet

- Fatwas and Surgery How and Why A Fatwa MDocument6 pagesFatwas and Surgery How and Why A Fatwa MOmar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- The Modernity of Dongui Bogam: October 2013Document10 pagesThe Modernity of Dongui Bogam: October 2013Quỳnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Dental Traumatology - 2022 - Lin - Tooth Resorption Part 1 The Evolvement Rationales and Controversies of ToothDocument14 pagesDental Traumatology - 2022 - Lin - Tooth Resorption Part 1 The Evolvement Rationales and Controversies of ToothJavRojNo ratings yet

- الهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةDocument113 pagesالهندوسية في توازن تعاليمها الأصلية وعقلها وشخصيتها الطبيعية السليمةIslamHouseNo ratings yet

- Intro To IslamDocument6 pagesIntro To IslamMuhammad Uzair BSSE2021No ratings yet

- Centric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfDocument3 pagesCentric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfManuel CastilloNo ratings yet

- RKUD2230General PerspectiveDocument27 pagesRKUD2230General Perspectivesyamimi ramlyNo ratings yet

- Ijmaa, Ihtihaad and QiyaassDocument5 pagesIjmaa, Ihtihaad and QiyaassUrgunoon Saleem KhanNo ratings yet

- Essay On Bill of RightsDocument4 pagesEssay On Bill of Rightseikmujnbf100% (1)

- Human Embryology, Research and EthicsDocument42 pagesHuman Embryology, Research and EthicsnorjannahhassanNo ratings yet

- Centric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfDocument3 pagesCentric Relation From Red Giant To White DwarfjoaompradoNo ratings yet

- Sefotho Exploration 2016Document16 pagesSefotho Exploration 2016Thabiso EdwardNo ratings yet

- Tehillim Psalms For Special Occasions PDFDocument20 pagesTehillim Psalms For Special Occasions PDFSeth KunchebeNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionDocument19 pagesFundamentals of Judaism 101: Oral TraditionYoel Ben-AvrahamNo ratings yet

- Osteo - and Funerary Archaeology - The Influence of TaphonomyDocument12 pagesOsteo - and Funerary Archaeology - The Influence of TaphonomyLucas RossiNo ratings yet

- Temporary Marriage - A Possible Solution To The PRDocument44 pagesTemporary Marriage - A Possible Solution To The PRYann VecNo ratings yet

- Kosher Fat: Mony Almalech (NBU)Document47 pagesKosher Fat: Mony Almalech (NBU)HECTOR ORTEGANo ratings yet

- Transplantation-Ethical IssuesDocument17 pagesTransplantation-Ethical IssuesivkovictNo ratings yet

- Healing Secrets in Holy QuranDocument24 pagesHealing Secrets in Holy QuranSyed AhamedNo ratings yet

- Answers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationDocument2 pagesAnswers To Section 3.7 Organ TransplantationbrownieallennNo ratings yet

- Parashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777Document4 pagesParashas Beha'aloscha: 16 Sivan 5777outdash2No ratings yet

- Consent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. SchacterDocument3 pagesConsent and Coercion at Sinai: Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacteroutdash2No ratings yet

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 pagesChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879510Document14 pages879510outdash2No ratings yet

- The Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli BelizonDocument3 pagesThe Surrogate Challenge: Rabbi Eli Belizonoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)Document4 pagesThe Meaning of The Menorah: Complete Tanach)outdash2No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny JoelDocument2 pagesThe Matan Torah Narrative and Its Leadership Lessons: Dr. Penny Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Performance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel ZylbermanDocument6 pagesPerformance of Mitzvos by Conversion Candidates: Rabbi Michoel Zylbermanoutdash2No ratings yet

- What Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery JoelDocument3 pagesWhat Happens in Heaven... Stays in Heaven: Rabbi Dr. Avery Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Flowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra SchwartzDocument2 pagesFlowers and Trees in Shul On Shavuot: Rabbi Ezra Schwartzoutdash2No ratings yet

- Shavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83lDocument2 pagesShavuot To-Go - 5777 Mrs Schechter - Qq4422a83loutdash2No ratings yet

- Reflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of BrachosDocument3 pagesReflections On A Presidential Chavrusa: Lessons From The Fourth Perek of Brachosoutdash2No ratings yet

- Lessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus ProcessDocument3 pagesLessons From Mount Sinai:: The Interplay Between Halacha and Humanity in The Gerus Processoutdash2No ratings yet

- I Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah NagarpowersDocument2 pagesI Just Want To Drink My Tea: Mrs. Leah Nagarpowersoutdash2No ratings yet

- The Power of Obligation: Joshua BlauDocument3 pagesThe Power of Obligation: Joshua Blauoutdash2No ratings yet

- Chag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. JoelDocument2 pagesChag Hasemikhah Remarks, 5777: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Experiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem PennerDocument3 pagesExperiencing The Silence of Sinai: Rabbi Menachem Penneroutdash2No ratings yet

- Torah To-Go: President Richard M. JoelDocument52 pagesTorah To-Go: President Richard M. Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Kabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther JoelDocument2 pagesKabbalat Hatorah:A Tribute To President Richard & Dr. Esther Joeloutdash2No ratings yet

- José Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37Document16 pagesJosé Faur: Modern Judaism, Vol. 12, No. 1. (Feb., 1992), Pp. 23-37outdash2No ratings yet

- Yom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel DavisDocument1 pageYom Hamyeuchas: Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davisoutdash2No ratings yet

- Nasso: To Receive Via Email VisitDocument1 pageNasso: To Receive Via Email Visitoutdash2No ratings yet

- A Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua FassDocument3 pagesA Blessed Life: Rabbi Yehoshua Fassoutdash2No ratings yet

- 879446Document5 pages879446outdash2No ratings yet

- Why Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of IsraelDocument5 pagesWhy Israel Matters: Ramban and The Uniqueness of The Land of Israeloutdash2No ratings yet

- Chavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתDocument28 pagesChavrusa: Chag Hasemikhah ז"עשתoutdash2No ratings yet

- Appreciating Moses' GreatnessDocument4 pagesAppreciating Moses' Greatnessoutdash2No ratings yet

- Eastron Electronic Co., LTDDocument2 pagesEastron Electronic Co., LTDasd qweNo ratings yet

- Glass Configurator Datasheet 2023 03 27Document1 pageGlass Configurator Datasheet 2023 03 27Satrio PrakosoNo ratings yet

- Teacher: Diana Marie V. Aman Science Teaching Dates/Time: Quarter: SecondDocument6 pagesTeacher: Diana Marie V. Aman Science Teaching Dates/Time: Quarter: SecondDiana Marie Vidallon AmanNo ratings yet

- DSF Course Curriculum 1305231045Document8 pagesDSF Course Curriculum 1305231045Gaurav BhadaneNo ratings yet

- Application of Buoyancy-Power Generator For Compressed Air Energy Storage Using A Fluid-Air Displacement System - ScienceDirectDocument7 pagesApplication of Buoyancy-Power Generator For Compressed Air Energy Storage Using A Fluid-Air Displacement System - ScienceDirectJoel Stanley TylerNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Past Paper QuestionsDocument174 pagesMathematics Past Paper Questionsnodicoh572100% (2)

- Emmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and TimeDocument308 pagesEmmanuel Levinas - God, Death, and Timeissamagician100% (3)

- 3700 S 24 Rev 0 ENDocument3 pages3700 S 24 Rev 0 ENJoão CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Report 1Document9 pagesReport 135074Md Arafat Khan100% (1)

- Cost Leadership Porter Generic StrategiesDocument7 pagesCost Leadership Porter Generic StrategiesRamar MurugasenNo ratings yet

- Shahetal.2022 TecGeomorpJhelumDocument21 pagesShahetal.2022 TecGeomorpJhelumAyesha EjazNo ratings yet

- Rear Drive Halfshafts: 2016.0 RANGE ROVER (LG), 205-05Document46 pagesRear Drive Halfshafts: 2016.0 RANGE ROVER (LG), 205-05SergeyNo ratings yet

- 3M CorporationDocument3 pages3M CorporationIndoxfeeds GramNo ratings yet

- Feasibility of Ethanol Production From Coffee Husks: Biotechnology Letters June 2009Document6 pagesFeasibility of Ethanol Production From Coffee Husks: Biotechnology Letters June 2009Jher OcretoNo ratings yet

- Whittington 22e Solutions Manual Ch14Document14 pagesWhittington 22e Solutions Manual Ch14潘妍伶No ratings yet

- Eng Pedagogy Class CTETDocument33 pagesEng Pedagogy Class CTETntajbun13No ratings yet

- SPE 163723 Pressure Transient Analysis of Data From Permanent Downhole GaugesDocument24 pagesSPE 163723 Pressure Transient Analysis of Data From Permanent Downhole GaugesLulut Fitra FalaNo ratings yet

- FermentationDocument23 pagesFermentationr_bharathi100% (2)

- Fundamentals of HydraulicsDocument101 pagesFundamentals of HydraulicswissamhijaziNo ratings yet

- Acute Gynaecological Emergencies-1Document14 pagesAcute Gynaecological Emergencies-1Anivasa Kabir100% (1)

- DMX DC Motor ControllerDocument23 pagesDMX DC Motor ControlleromargarayNo ratings yet

- In Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloDocument112 pagesIn Re Plagiarism Case Against Justice Del CastilloRaffyLaguesmaNo ratings yet

- Name:: Nyoman Gede Abhyasa Class: X Mipa 2 Absent: 25 AnswersDocument2 pagesName:: Nyoman Gede Abhyasa Class: X Mipa 2 Absent: 25 AnswersRetrify - Random ContentNo ratings yet

- Nursing Care PlanDocument4 pagesNursing Care PlanPutra AginaNo ratings yet

- BDM SF 3 6LPA 2ndlisDocument20 pagesBDM SF 3 6LPA 2ndlisAvi VatsaNo ratings yet

- Optimal Design of Low-Cost and Reliable Hybrid Renewable Energy System Considering Grid BlackoutsDocument7 pagesOptimal Design of Low-Cost and Reliable Hybrid Renewable Energy System Considering Grid BlackoutsNelson Andres Entralgo MaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Form 137Document2 pagesForm 137Raymund BondeNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Fauzi-855677765-Fizz Hotel Lombok-HOTEL - STANDALONEDocument1 pageMuhammad Fauzi-855677765-Fizz Hotel Lombok-HOTEL - STANDALONEMuhammad Fauzi AndriansyahNo ratings yet

- Optimizing The Lasing Quality of Diode Lasers by Anti-Reflective CoatingDocument21 pagesOptimizing The Lasing Quality of Diode Lasers by Anti-Reflective CoatingDannyNo ratings yet