Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Uploaded by

Ivan MendesOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Uploaded by

Ivan MendesCopyright:

Available Formats

RUNNING HEADER: FINANCIAL DERIVATIVES: A PERCEIVED VALUE

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Ivan N. Mendes

Eastern Nazarene College

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

2

Abstract

The usage of financial credit derivatives has allowed for increased competition, profitability and systemic

risk in todays financial markets, globally and domestically. These instruments if adequately used may

curb their negative externalities, while allowing positive externalities to flourish. This documentation

looks at the nature of credit derivatives, especially credit default swaps (CDS), collateral debt obligations

(CDO), special purpose vehicles (SPV), and systemic risks and accompanying policies. A brief outlook of

the 2008 global financial crisis is detailed, but the majority of this documentation will be focused on the

purposes, operations, and contractual engineering of CDSs and CDOs. Capped by regulatory policies

following the global financial crisis, this documentation concludes with the Dodd-Frank Act. This

documentation shows the neutrality of credit derivatives, the benefits thereof, and the consequences if

firms are not adequately measuring potential risk factors when contracting derivatives.

Keywords: derivatives, credit derivatives, CDS, CDO, SPV, Dodd-Frank Act, global financial

crisis, market regulation, systemic risk

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Derivatives have been in use, for commercial and investment purposes, for centuries, and they are

not new. Once used for bets on the future prices of agricultural commodities, such as rice and corn traded

in 15th century Japan, derivatives have evolved to include any and everything. Today these commodities

are traded on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, which still involve derivative usage. A derivative is a bet

either used in hedging or speculating. By 1990s, a mass explosion in other forms of derivatives (apart

from agricultural commodities) was on the verge with the introduction of both interest rate swaps, and

credit default swaps. By 1996 the notional value of the credit derivatives market, which is the value of

outstanding bets measured by the value of things being betted on, was roughly $180 billion. In contrast,

the year 2008 saw an estimated notional value of the derivative market of $600 trillioni. Ending June

2013, the notional value of the derivatives market was $668 trillion; this number was reported from

dealers across 13 countriesii. This vast increase in the notional value of the derivatives market can be

attributed to the legal status of speculative trading rather than innovative advancements. Lynn Stout

(2009) speculated that difference contracts made the difference when considering the legality of a

derivative contract, whether it was binding or not. A difference contract states that one may wager on

anything, but the rule required that if one wanted to enforce such a wager he or she had to demonstrate to

a judge that one party held title to the underlying bet. The betted entity is called, in financial derivative

terms, the underlying. Henceforth, bets on every financial instrument possible became available to

savvy investors, whom used the advantage promulgated by swaps to profit (Stout 1009). Credit

derivatives, being traded over-the-counter (OTC), were rarely regulated, causing the old common-law

principles, including difference contracts, to become the primary checks against speculations. Speculation

is the attempt to profit not from producing or even providing investment funds to another who is

producing something but rather from predicting the future better than others. In retrospect, betting on

future events, whether related or unrelated to ones investments. Although the notional value of credit

derivatives was in the trillions of dollars, the market value of these contracts only amassed to $3.9 trillion

at end-June 2013iii. This disparity between market value and notional value questions the amount of

speculation believed to have occurred during the global financial crisis and even now. These numbers

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

greatly support the ideology that speculative trading still occurs today. Unregulated, the global markets

would take a turn for the worst. Few knew of the implications that such regulations had on the limitedness

of corporate governance and financial power. When Congress repealed the Glass-Stiegel Act (the Act)

in 1999; that same act that was adopted during the crisis of the Great Depression in order to separate

commercial and investment banking activities. It allowed for the merger of the two long separated

entities. In the 1980s, the popularity of laissez-faire regulations began the deregulation reflected in the

U.S. economy until the housing market collapse in 2008-2009. Under the act, commercial banks could not

function as investment banks and underwrite corporate securities (bonds, stocks, options, derivatives) or

engage in brokerage activities. With that said, commercial banks found themselves at a disadvantage,

because the majority of money was being made in investment firms. When Congress repealed GlassStiegel, it enacted the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, and its that passage, the

functionality of commercial and investment banks were blurred. As a result of grand deregulation came

the global financial crisis. It is believed that various variables caused the global crisis, such as: high

corporate leverages, over-borrowing, deregulations, securitization, and complex securities. The focus of

this documentation will not be to examine the financial crisis itself, but to examine a key contributor to

the global financial crisis. The key contributor was known as credit derivatives (a complex security).

From its inception, credit derivatives allowed for corporations to provide high leverages with little risk,

thus producing a vast increase in profitability and cash-flow. A credit derivative is simply an investment

vehicle that derived its value from another financial instrument. It is through the introduction of credit

derivatives that the market, inevitably, plummeted to record lows, and the global market, well, shaken to

its core.

CREDIT DEFAULT SWAPS & COLLATERALIZED DEBT OBLIGATIONS

Credit derivatives are mainly used in credit risk management with the purpose of diversifying

across different sectors and geographical regions, or to bypass regulatory constraints. A credit default

swap (CDS) is simply an insurance contract against the cost of default of a company, particularly a

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

company that has issued debt. This company is referred to as the reference entity. The CDS insures the

protection-buyer payment in a credit event such as a default, or restructuring of debt from the

protection-seller, usually a firm more capable of managing such debts. In essence, a firm is hedging

against a risk if involved in a swap transaction. Regarding a credit event, the protection-seller

(counterparty) would provide payment in the form of a lump sum and return the loan that functioned as

collateral. For this risk, protection-sellers usually required a premium fee to be paid periodically for such

services. For example take Cincinnati based, Gibson Greetings, and Bankers Trust, derivatives contract

which worked like so: Gibson would pay Bankers Trust the six-month LIBOR, squared, then divided by 6

percent times $30 million for four years. In the event of a credit event, Bankers Trust would pay a

minimal payout of 5.50 percent times $30 million.iv When all was said and done, Gibson Greetings lost

more on the premiums paid to Bankers Trust compared to the fulfillment of the contract in a default. It is

because of these reasons that firms such as AIG and Bankers Trust contracted CDS on the hundreds of

collateralized debt obligations (CDO) they managed. In the event that there is not a default, the

protection-seller is not obligated to payout. With that said, unlike other credit derivatives (such as interest

rate swaps), CDS risk assumptions are not symmetrical. The protection-buyer, in essence, takes a short

position in the credit risk of the reference entity (debt-issuing firm), and by this the buyer is relieved of

exposure to default. Ultimately, by doing so the buyer surrenders the ability to profit on the respective

loan, because it is now in the possession of the protection-seller. But still, the protection-buyer is not

completely relieved of risk because it must now be conscience of the default-risk of the protection-seller,

in that it may not be able to payout if the reference entity defaults. This risk is known as the counter-party

reference risk. In addition, the protection-buyer must likewise assume other risks in relation to the

reference entity. In contrast, the protection-seller, ultimately, takes a long position in the credit risk of the

reference entity. Likewise, a counterparty risk is associated with the seller of insurance in regards to

premium revenue, in the event that the protection buyer defaults, which would annul the contract. In its

simplest form, a reference entity is usually a company or government enterprise, and it is in this market

that most CDS contracts are involved. Another form would be that of a basket CDS which is when two or

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

more reference entities exist. According to Ayadi & Berh (2009), a more common form of a basket CDS

is called first-to-default CDS, where as: the protection seller compensates the buyer of losses associated

with the first entity in the basket to default, after which the swap terminates and provides no further

protection (Rym Ayadi, 2009). CDSs that have higher numbers of reference entities are referred to as

portfolio products, which were used in connection to synthetic securitizations, and this transfers risk that

is associated with the CDS back to the CDO note holder. In such a transaction, a securitization, the legal

rights, or ownership of an asset (loan) is transferred to a special purpose vehicle (SPV). A CDO would be

considered a SPV. CDOs and CDSs are what in essence plummeted the markets in the global financial

crisis, in that CDOs would be structured of various financial instruments and then betted on. A CDO

involved transferred collateral loan obligations (loans, CLO) or collateral bond obligation (bonds, CBO)

or a combination of the two and these would be divided in tranches that would best attract investors.

Tranching allowed for sellers of CDO to specifically market and enlist their portfolios according to credit

ratings with the best being on top and working downward to junk-grade investments. As is evident, the

higher rating tranches had the lowest risk in comparison to lower rated tranches. Upon issuance, a report

would be provided to the derivative buyer that included the underlying obligations, scores, and ratings of

the tranches and this was seen as a form of regulation. A fairly common underlying portfolio of a CDO

could include assets such as corporate bonds, government bonds, commercial loans, and asset-backed

securities (ABS). These portfolios were managed at the discrepancy of the selling firms. Just like

preferred stocks the senior tranches the highest rated tranches had repayment priority over its lesser

counterparts (Ayadi & Berh 2009). Usually arranged in a way that an AAA rating was assigned to it, the

senior tranche accounted for most of the transaction volume, somewhere upwards of 90 percent.v

Another major source of growth in the OTC derivatives market came from index CDS, which

functioned like any other index fund, and these held tens, and hundreds of different CDS contracts. A

CDS index provides protection for all entities within the index. For instance, if a firm wanted to hedge

against the possible collapses of Lehman Brothers, Bear Sterns, LTCM, and AIG, rather than summoning

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

separate contracts, it could buy into an index that had these entities. This ultimately lowered transaction

costs and provided a speedier process in attaining protection against possible credit events. The two main

indices are the CDX indexvi, and the iTraxxvii index. In addition, CDSs were able to specify CDO as loan

and note obligations, giving a CDS the ability to be leveraged against a specific loan issued by another

firm. As a consequence, a CDS could be taken out against a loan that was not under the ownership of the

protection-buyer. This practice suffered great losses during the global financial crisis, because it caused

great stress and promulgated risk on firms unable to compensate for it.

DOCUMENTATION OF CREDIT TRANSACTIONS AND SETTLEMENTS

In constructing a CDS contract, several things must be associated and assigned. For instance,

various credit events must be agreed upon, and they could range from anything from failure to pay to

obligation default. The following are some of the most popularized credit events agreed upon during the

contractual stages of a CDS contract:

Default

Bankruptcy, is often associated with corporate reference entities more than governments

Debt restructuring can raise red flags for the parties of a CDS, especially if the reference entity is

a corporation. An example would be maturity extension in place of an imminent default. Often

referred to as an insignificant credit event, because a firm may simply want to restructure without

a case of defaulting. As a result motive is not always clear, thus it is given little recognition in

regards to other credit events.

Repudiation, when regarding government bonds, or investment activities. This provides for

speedy compensations after a specified action on behalf of the government reference entity.

Acceleration or defaulting on obligations, including such things as violation of a bond payment

covenant. (Transaction documentation and settlement, Ayadi & Berh 2009)

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

If the terms of a credit event are violated then the protection-seller must comply with regulations

and provide settlement. The two ways to provide payment in a CDS contract are physical settlement, and

cash settlement. A physical settlement involves the protection-buyer to readily deliver the defaulted debt

of the reference entity with the face value equal to the notional value specified to the protection-seller. In

return, the protection seller pays the par value: the face amount of the debt. If a credit event occurs and

the counterparties decide upon a cash settlement, the defaulted bond is then auctioned to determine the

post-default market value. Upon determination of the post-default market value of the bond, the

protection-seller pays the buyer the difference, which would give the protection-buyer the amount paid

for the CDS.viii

INHERENT CREDIT TRANSACTION RISKS

In addition to defining possible credit events and settlement procedures, firms desiring to entire

into CDS contracts must consider several inherent risks present in credit derivative transactions. If these

risks are improperly managed they may offset the assumed benefits of credit derivatives. The first of these

risks would be counterparty credit risk, which is usually seen as the most severe risk inherent with CDS

transactions because there is no promise of profitability. A simple way to measure counterparty credit risk

is to measure the current exposure risk at the current market value (this can also be conducted for future

exposure risk). This risk ultimately tells the parties of the contract, the likelihood of either party

defaulting, and is usually read in the firms credit rating. It is not unusual for firms to require collateral in

the agreements, to the affect that one party perceives future exposure that may be detrimental. For

instance, just days before its collapse, the financial conglomerate, Lehman Brothers, had fairly handsome

ratings that would allow for counterparties to favor contracts without collaterals. This turned out to be a

nightmare after Lehmans collapse. AIG, likewise, was given AAA ratings from various rating agencies,

allowing for favorable credit derivative contracts, without collaterals, but it too ultimately failed the

expectations of its counterparties.

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

Market liquidity risk is another risk in addition to counterparty credit risk inherent in credit

derivative transactions, and is a direct result of the failure of major financial institutions. A problem

present is the forced sales of positions in order to remain within the margin requirements. This would

conclusively drive down the price of the investment asset. If prices decline further, it may lead other

market participants to sell their positions, which could eventually dry out liquidity and produce an

unsatisfactory rating. This may introduce grounds for a default or recall. It is detrimental to the liquidity

of the market, if a market shock takes place, such as the default of a large reference entity or major market

maker.

Legal risk is the risk associated with the differentiation of parties involved in the contract. This is

more likely when the contract is poorly defined, such as terms and the misidentified reference entities. For

instance, J.P. Morgan has recently paid billions in order to have proper contracts that entail the

appropriate reference entities and terms. It can be detrimental when two firms conduct a CDS contract

and involve another untargeted reference. Even worse, is when the misappropriated entity has little to

no debt, which would make a CDS origination nearly impossible. Usually, documentation and legal risks

were readily overcome by major market-firms that developed common databases of all available

reference entities; thus creating necessary screening processes.

Operational risk would be another form of risk associated with CDS contracts. Backlogs of

unconfirmed trades, management trading reassignments, and settlement debacles are just some of the

issues created by ever-increasing complexity with new derivative products. But the priciest of risks

involved in a CDS contract was that of mis-pricing. Mis-pricing risk is inevitable in the derivative market,

especially in more complex derivative securities. The market for swaps include complex formulas created

by various corporations that would make one cringe. Formulas used to derive at a derivatives pricing

were not readily understood, and this caused risk for novice investors. If price distortions occur, this may

put the protection-buyer at a disadvantage because it could have to pay more in premium when prices are

set too high thus not properly reflecting the underlying risks. If an insuring firm misprices the CDS, this

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

10

will leave the counterparty at a disadvantage and vice-versa. It is not always possible to price the CDS at

a correct number according to the underlying risks. The rating of a firm heavily influenced the pricing of

CDS contracts. If the firm was rated AAA or even AAa, protection-sellers might misprice the derivative,

purposefully, in order to receive excess premiums to profit from secure firms. But that is not always the

most likely of events as is evident in the global financial crisis (Risks inherent in credit derivative

transactions, Ayadi & Berh 2009).

Ultimately, financial institutions enter into credit derivative transactions as a way to better

manage risk and become better leveraged. This was the main reason the global financial crisis occurred,

overleveraged, and the use of toxic instruments such as mortgage-backed-securities (MBS). In theory

credit derivatives provide firms with an optimal overall risk assessment (profile) and helps to improve

profitability, efficiency and credit ratings. If properly used credit derivatives allow financial institutions

access to a broader range of risk-return combinations and underlying risks. Again, if properly used,

derivatives can help alleviate risk and provide for adequate hedging of troubled assets, and reduce

exposure. If it were not for improper usage of credit derivatives, the markets would probably have not

collapsed, but that is only a speculation, the very thing that brought Wall Street to distraught.

GLOBAL COLLAPSE OF 2008

The global financial crisis was a direct consequence of the continued deregulation and unethical

stance of the U.S. economic systems. With blurred regulations, the function of commercial and,

investment banks, insurance companies and real estate mortgage banking firms were, in retrospect, made

one, in that they could conduct business likened to one another. With that, companies became more

creative in their business practices, introducing differing financial instruments, some even toxic. For

instance instruments were derived that included: mortgage-backed securities (MBS), structured

investment vehicles (SIVs) which were forms of CDOs. These instruments were used by firms to provide

leverage, cash, hedge, and the ability to speculate the movement of the markets. A mortgage-backed

security (MBS) is a derivative security because the value thereof was derived from the mortgages (assets)

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

11

in its portfolio, which would secure it, that is if monthly-mortgage payments were made. On the contrary,

a structured investment vehicle (SIV) was, technically, a virtual bank, which was operated by an

investment or commercial bank, but these operations were unrecorded in the firms balance sheet. The

purpose of a structured investment vehicle was to produce short-term funds to be propagated in long-term

investments of mortgage-backed securities, and by this, involving highly leveraged positions. Structured

investment vehicles usually invested in high-grade MBSs, which would provide detail into the risk-free

environment that it fostered. Ultimately, a SIV derived it value from the MBS it represented; thus if the

MBS lost value, the SIV followed suit. Collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) had also been a major

investor in MBS. According to Eun and Resnick (2014), an investor in a CDO is taking a position in the

cash flows of a particular trance, not in the fixed-income securities directly (Cheol S. Eun, 2014). In

retrospect, CDSs allowed for buyers of risky bonds the ability to convert the bond into a risk-free

investment. This allowed for companies to overly leverage themselves in hopes of producing higher

payouts. As a consequence, CDSs became the leading contract used against CDOs, which included things

such as bond and loan obligations, previously discussed (thus constituting MBSs as a CDO). The

emergence of CDS on the MBS market was rapid and as more mortgagees defaulted, the more attractive

bets on this form of derivatives became. From 2004 to 2008, the notional value of the credit default swap

market grew nearly ten-fold, from $6 trillion to $57 trillion (Stulz 2010). Credit default swap contracts

that insured default risk of a single firm was called single-name contracts, and likewise, of many firms,

multi-name contracts. Of the total credit default swap market, 80 percent of contracts were single-name

contracts, leading one to speculate specified targeting of failing firms. For instance, various firms betted

against Lehman brothers and expected to receive payments from Lehman on their derivatives. Targeted

and over-leveraged, Lehman crashed as soon as defaults occurred.

Key issues of the financial crisis included several things but at the top of the list would be the

misuse of credit derivatives and the poor understanding thereof. This led firms to reproduce derivative

risks on a more grand scale. Some key issues were:

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

12

According to Rene Stulz (2010), banks and other financial institutions unfortunately held

mortgage products on which they made large unexpected losses. These unexpected losses were

produced by the misunderstanding of derivatives, their mispricing, and an inadequate

understanding of credit risks. Likewise, regulators did not require financial institutions to amass

capital because these institutions had bought protection, through CDSs, on their investment assets

further duplicating risks.

Losses on CDS pertaining to subprime mortgage-backed-securities was lead by major defaults

producing less liquidity for the payout of such losses, thus originating firms assumed risks. This

was a direct consequence of the web that is produced by credit default swaps, entangling one SPV

to various firms. Thus, if an institution failed in this web, it would have lead other institutions to

fail as they recorded losses on exposure. Thus exposure became another issue because it

heightened systemic risk. The uncertainty about the solvency of financial institutes was issued as

major market-makers were affected via the domino-effect produced by securitization (Credit

Default Swaps on Subprime Mortgage-Backed Securities, Stulz 2010).

According to Stulz (2010) credit default swaps heighten the concern of securitization, the

combination of firms betting on the same SVP, made the value of CDS jump, often by very large

amounts, when default occurred (Stulz 2010). Lehman Brothers, at the time of default, had

roughly one million derivative contracts on record with various financial institutions. Thus when

it failed, the notional amount was far too great for the firm to payout, causing it to declare

bankruptcy. When a firm contracts with numerous firms, it increases the counterparty risk. Would

the creditors default? Would the mortgagees default? How would payment be supplied if

defaulted? Lehman did not have answers to these questions because it was extremely entangled,

and at one point over-leveraged 90:1, raising risks of great uncertainty.

Another issue explored by Stulz (2010) was that the value of a contract, upon default, would be

greatly increased. To illustrate, suppose the market expected that there was a 30 percent chance

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

13

that a dealer would default, and recovery would be 50 percent. If a default occurs, the value of the

bond falls to 50 percent, which was the recovery value, causing the bondholder to lose 50 percent.

The CDS would pay 50 percent. If the time value of money is ignored, the premium value of a

$20 million credit default swap contract for the protection-buyer would be $6 million (there was a

30 percent chance that the protection-seller would provide a payout, thus causing a premium of

$6 million to be required; this was a periodical total, most likely per annum). At default the value

of the credit default swap would be $14 million, leading the protection-seller to lose $8 million on

the day of. This was also another risk that protection-sellers did not fully grasp. Lehman did not

grasp this concept likewise because it could not payout on contracts days before its collapse. For

instance it cost only $700,000 to insure a $10 million contract. But upon default, Lehman would

payout over $9 million, a crippling number (Counterparty Risks and the Financial Crisis, Stulz

2010).

These are some of the risks presented when financial institutions do not properly regulate and

adequately understand the usage of financial derivatives. Improper use of credit derivatives led financial

institutions, such as Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns to amass great debt without concern for assets.

These firms were dealers, thus their books were largely balanced and collateralized. These failed because

of securitization and the web-like environment created by the grand usage of credit default swaps.

Although, it can be argued that derivatives were not the proximate reason for the defaults of these firms, it

is conceivable that it was. If it were not for the improper usage of these instruments, perhaps the outcome

might have been different, or perhaps the global financial crisis may have been averted.

REGULATORY ACTIONS

Since the global financial crisis of 2008, the United States Congress, along with other

governmental agencies has enacted various laws and practices that have helped create a more adequately

regulated market, at home and abroad. On July 21, 2010, President Barak Obama signed into law the

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (henceforth Dodd-Frank). The purposes of

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

14

the act were to provide for financial regulatory reform, consumer and investor protection, an end to toobig-to-fail, to regulate the OTC derivatives market, and ultimately to prevent another financial crisis

(Evanoff & Moeller 2012). Likewise, the oversight and supervision of financial institutions were affected

along with provisions for new resolution procedures, capital requirements, compliance efforts, and OTC

regulations for large market-participants. Dodd-Frank called for the development of various new

regulatory rules and mandates. Of these mandates are: the requirement to introduce and staff a number of

new entities (offices, bureaus, and councils) with the responsibility of studying, evaluating, and

promoting consumer protection, and financial stabilities in the markets. Likewise, regulators are now

obligated to identify and increase regulatory scrutiny of systemic risk factors produced by large marketparticipants. Unlike previous attempts to regulate the OTC derivatives market, and other such markets,

the Dodd-Frank greatly differed in that it gave regulators more flexibility to reform regulatory agencies

and practices (Financial Stability, Evanoff & Moeller, 2012).

With that said, the act also imposed deadlines by which reforms had to be in place or studies

conducted causing financial institutions to become more efficient in their dealings with credit derivatives.

This time constraint produces significant pressures for regulators to meet deadlines while considering the

potential ramifications that their actions may have on the industry, or other adverse impacts on the

industrys ability to carry out its role in the markets. According to the report published by the Federal

Reserve Bank of Chicago by Evanoff and Moeller (2012), the Dodd-Franks most important objective

would be to ensure a stable and secure financial system. The act brought to light the inadequacy of

microprudential regulation, in that it was thought to have been enough to keep the markets safe during the

era of the crisis. As a result, macroprudential regulation was introduced alongside microprudential, and

this focused on the overall market stability and systemic risk, which was a key factor. The flaws of a

purely microprudential approach was that it ignored interconnections (web-process) and externalities,

not being considerate of one firms actions in consequence to other firms in the event of a spillover

(Financial Stability, Evanoff & Moeller, 2012). The act, introduced a consultative group of financial

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

15

regulators known as the Financial Stability Oversight Council (the Council) along with the Office of

Financial Research (OFR), which helped regulators manage systemic risk. To accomplish this, the

Council had the authority to make appropriate macro-microprudential regulations, subscribe to collection

of information about market transactions, and institute important system activities that came under the

oversight of the Federal Reserve. The introduction of the Council was specifically designed to avoid

another regulatory bureaucracy, and instead bring together regulatory agencies together in a formal way

to contribute to public policy.ix The Council was a pivotal creation of the Dodd-Frank act in that it

enabled the supervision of risk-based capitals, leverages, liquidity and credit exposure, and ultimately

required firms to keep a tight-reign over such variables. The leading causes of failures, bankruptcies, and

market collapses were dealt with in the creation of the Financial Stability Oversight Council through

various mediums, ranging from leveraging, to capital requirements, to risk-management and debtobligations. The issue of Securitization was also dealt with and its transparency and risk factors mutually

debated. In that regard, credit risk retention policies were evident in curbing losses. In securitization

protection-buyers had to retain up to five percent of the risk involved in a contract; this rule applied to

CDOs and there was no longer a possibility to hedge or transfer risk (Morrison & Foerster). But firms that

used proper underwriting standards could be rewarded with a lower retention percentage. Financial

institutions dealing in securities had to provide required disclosures, which included: asset and data-level

details with material information regarding the loan brokers, originators, the nature of compensations, and

the amount of risk. In addition, credit rating agencies, such as Moodys and Standards & Poors, were

required to provide detail explanations into the nature of their ratings. This was something that they did

not do extensively during the global crisis. These are just some of the regulatory discrepancies that the

Dodd-Frank tackled and it is in no way the totality of the measure, which is far more extensive.x In

addition to providing for financial stability, the act allowed for the liquidity of troubled firms, of which

Lehman Brothers did not obtain and consequentially failed.xi Such bankruptcies had negative

externalities, of which the act favorably confronted.

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

16

In title VII of Dodd-Frank, the framework for regulating the OTC derivatives market was

designated. Before the crisis, many desired to regulate the OTC derivatives market because, it represented

a risk to the financial system in that it lacked oversight, and risk-management tools (including a central

clearinghouse). The act brought the derivative market, with the exception of some swapsxii, under the

joint-control of the SEC and CFTC to improve transparency, governance and oversight (Morrison &

Foerster). The SEC would regulate security swaps, while the CFTC regulated other swaps, producing

somewhat of a separation of powers. In retrospect, the legislation imposed new requirements for financial

vehicles such as swaps (derivatives), the market participants (protection-sellers and buyers), and the

facilities where the trades were conducted (execution facilities and clearing organizations) (Derivatives

Regulation, Morrison & Foerster). Entities that functioned in market swaps were designated swap dealers

while non-dealer entities who participated in the trading of the swaps were designated major swap

participants (SD and MSP, respectively). Both SDs and MSPs had to register with the governing

agencies, thus producing accountability, transparency and safety in the financial markets. If the SD or

MSP did not have adequate regulations, they may have been required to maintain ample capital to

compensate. Other rules may include a limited exposure to credit derivatives as a consequence of

inadequate regulations. The purpose of title VII of the act was to ensure a more stable financial market

through the providing of regulatory powers confined in both the SEC and the CFTC. The Dodd-Frank act

is considered the cornerstone for financial reformation; it is what future financial regulations will be

measured up to.

CONCLUSION

Warren Buffet quipped that credit derivatives were financial weapons of mass destruction,

carrying dangers that, while now latent, are potentially lethal. Some may argue that he was right while

others may not quite agree. In my view, if properly used and regulated derivatives may have bountiful

benefits to firms and investors contracting them. Credit derivatives, in theory are designed to make for a

more efficient and stable market. It therefore permits individuals and firms to achieve payoffs that would

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

17

otherwise not be achievable without the use of derivatives, or at increased costs. Likewise, the possibility

of hedging against future risks that would otherwise not be possible to hedge is made possible through

credit derivatives. As stated earlier, in theory, derivatives can make for a more efficient market by the

production of information. It is through swaps that some long-term interest rates are obtained because that

market is more active and liquid than the bond market. It levels the playing field by allowing investors to

invest on information that might otherwise have been expensive to acquire. For instance, when short

selling a stock, transaction times are slowed down because one has to borrow bought shares from another

investor, making it less efficient. With an option, which is a derivative that is essentially a short position,

the investor can more easily acquire these same stocks, with relevant information at the exact price

determined. This ultimately speeds up trading, improves market efficiencies and produces a more liquid

system.

Credit derivatives allow firms to hedge risks or at a bare minimum the costs of hedging such

risks. It cuts both ways; a derivative may greatly benefit through improved performance or may create

systemic risk, usually caused by firms that are unethical in the market. In an interconnected economy a

collapse of a large market-participant may imply greater systemic risk, and this was evident in the

collapse of large multinational enterprises, including Lehman Brothers, AIG, Bear Stearns, and Merrill

Lynch. It is imperative that both derivative users and regulators, especially with the introduction of the

Wall Street Reform Act, be cautious and vigilant about said transactions. Firms must be able to check off

on the risks previously presented (such as counterparty risks, legal risks, market exposure risks). It is

believed that the derivatives market is fairly regulated, although not as well as one would like, but

nonetheless regulated. Today, various derivatives are actively traded and major firms and clients profit

from their use. Interest rate swaps compile the largest portion traded for the derivatives market, with

hundreds of trillions in notional value. Options and insurance contracts (CDS) are still traded but with

more careful oversight by said agencies and federal regulations. In previous years a more interest-derived

instrument has gained popularity: namely, the Bit coin. The Bit coin is an electronic currency derivative

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

18

product, which has a value of its own produced by the activity of the market (Bit coin market). It is also

speculated that there appears to be another housing bubble, or credit bubble compiling now, and that the

usage of credit derivatives may imply another financial crisis. Should we fear credit derivatives? Should

we denounce them as completely unethical or as a nuisance? Perhaps not. We believe that planes are

fairly safe, and that it is economically sound to travel long distances via one, thus we board it without

giving another thought. This same logic should be given to credit derivatives; they are economically

sound and safe in the proper contexts. Although this form of derivatives is new and has posed great

threats to the global markets, it should not be resigned as, what Google decided to quip, as worst Wall

Street invention. A life without proper boundaries, and rules is reckless, and not civil, leading to great

damage, but with boundaries it can be a bounty of wealth and thus is the case with credit derivatives.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

19

Rym Ayadi, P. B. (2009). On the necessity to regulate credit derivative markets. Journal of Banking Regulation,

10(3), 179-201. Retrieved from www.palgrave-journals.com/jbr/

ii

BIS surveys of OTC derivatives market statistical release

iii

BIS survey of OTC derivatives market statistical release

iv

Stulz, R. M. (2005). Demystifying Financial Derivatives. The Milken Institute Review, 20-31.

Rym Ayadi, P. B. (2009). On the necessity to regulate credit derivative markets. Journal of Banking Regulation,

10(3), 179-201. Retrieved from www.palgrave-journals.com/jbr/

vi

CDX is the family CDS index products covering North America and emerging markets. The Markit Group

Limited owns, manages, compiles and publishes this index from the leading industry source for pricing and

valuation. The CDX consists of 125 North American investment-grade firms.

vii

iTraxx is the family CDS index products covering European and Asian markets. The rules-based indices comprise

the most liquidable entities in the European and Asian credit markets, and they consist of iTraxx Europe, iTraxx

Hivol, iTraxx Crossover, iTraxx Asia ex-Japan, iTraxx Japan, iTraxx Australia, and various others. This index was

primarily owned by the International Index Company (IIC), but is now jointly operated by the IIC and the Markit

Group Limited. It is considered the benchmark for European and Asian credit markets.

viii

Main Characteristics of CDS transactions

Cash Flows

Protection buyer pays regular premiums over the life of the swap

Protection seller pays amount (depending on the agreed

settlement procedures) following the credit event.

Reference Entity

Usually investment grade rated corporations, banks and

sovereigns from developed countries.

Risks Involved

Counterparty credit risks the risk that the transaction

counterparty defaults before the final settlement of the

transactions cash flow protection seller defaults on contingent

payouts and protection buyer defaults on premiums.

Legal risks credit event definitions do not cover all potential

risks (every potential).

Market liquidity risk A decline in asset market liquidity as a

direct failure of one or more major participants in the CDS

market.

Operational risks.

Types of CDS

Standardized Contracts

ISDA Master Agreements

Trigger Events

ISDA standard credit event default, failures, obligation

default, restructuring of debt.

Settlement in the case of a credit event

Physical Settlements

Cash Settlements

Source: Ayabi & Behr and own research on ISDA websites

ix

The Council consisted of ten members, each having voting powers, and five nonvoting members. This Council

was made up of federal and state regulators and an insurance expert appointed at the pleasure of the President. The

voting members are: (1) Secretary of the Treasury, who serves as chairman of the Council; (2) Chairman of the

Financial Derivatives: A Perceived Value

20

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; (3) Comptroller, OCC; (4) Director of the Bureau of Consumer

Financial Protection; (5) Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission; (6) Chairman of the FDIC; (7)

Chairman of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC); (8) Director of the Federal Housing Finance

Agency (FHFA); (9) Chairman of the NCUA board; and (10) Insurance expert appointed by the President. The

nonvoting members, who are serving as advisors are: (1)Director of the Office of Financial Research; (2) Director of

the Federal Insurance Office; (3) State insurance commissioner; (4) State banking supervisor; (5) State securities

commissioner (or officer).

x

The Dodd-Frank act includes other categories that cover reforms ranging from: investor protection, credit rating

agencies, the Volcker rule provisions, compensation and corporate governance, and capital requirements. In regards

to the use of derivatives, the section: Investor protection reformation included such topics as liability and

disclosures, custody and client request (relationship), conflicts of interest, short sales and SEC powers. Credit rating

agency reformation included a massive portion of liabilities and required disclosures on behalf of the credit rating

agencies. The three major rating agencies are: Moodys, Fitch, and Standards and Poor. The Volcker rule, named

after Chairman Paul Volcker, operated under the premise that speculative trading was a key contributor in the

financial crisis, thus it desired to prohibit such transactions. With that said Proprietary trading was outlawed. It is

defined as the engaging of trades on accounts of banking entities, or nonbank financial companies in transactions to

sell, acquire, dispose of any security, any derivative and any contract of sale of a commodity for future delivery. In

addition to prohibited trades, the rule does allow for some permitted activities including: transactions in U.S.

government bonds, underwritten transactions (of which the contracts are reasonable and do not exceed obscure

terms), risk-mitigating hedge activities so long that they are used with banking entities, contracts or holding firms

that are specifically designed to reduce risk, and SBIC investments, and organized hedge fund activities (private

equity). Finally, the act discusses the issue of capital requirement, which was kept at a bare-minimum by investment

firms during the financial crisis. This amendment required that banks or nonbanks companies that held total

consolidated assets of $50 billion or more to establish risk-based capital requirements, leverage limits, and liquidity

requirements. These were in essence bars against the dangers of firms becoming insolvent. These, and various other

rules, are incorporated in the Dodd-Frank Act.

xii

Forward contracts on commodities that are for physical delivery are exempt, along with foreign exchange swaps

and foreign exchange forwards. These are not defined as a swap.

Evanoff, D., & Moeller, W. (2012). Dodd-Frank: Content, purpose, implementation status, and issues. Economic

Perspectives, (0164-0682), 75-84. Retrieved March 1, 2015.

Morrison & Foerster. (n.d.). The Dodd-Frank Act: A cheat sheet. 4-25.

Stulz, R. (2010). Credit Default Swaps and the Credit Crisis. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24(1), 73-92.

Retrieved February 1, 2015.

You might also like

- Nomura CDS Primer 12may04Document12 pagesNomura CDS Primer 12may04Ethan Sun100% (1)

- Inside Job TermsDocument8 pagesInside Job TermsKavita SinghNo ratings yet

- Financial Risk Management AssignmentDocument8 pagesFinancial Risk Management AssignmentM-Faheem AslamNo ratings yet

- Chap 009Document19 pagesChap 009van tinh khucNo ratings yet

- Cat Bonds DemystifiedDocument12 pagesCat Bonds DemystifiedJames Shadowen-KurzNo ratings yet

- FA FS Front Arena 4.2Document2 pagesFA FS Front Arena 4.2Joanne ChungNo ratings yet

- Credit Derivatives - Basic Concepts Golaka C NathDocument19 pagesCredit Derivatives - Basic Concepts Golaka C NathGolaka NathNo ratings yet

- Financial Crisis GlossaryDocument5 pagesFinancial Crisis GlossaryficorilloNo ratings yet

- Credit Default SwapsDocument7 pagesCredit Default SwapsMạnh ViệtNo ratings yet

- Credit Derivatives Not InsuranceDocument59 pagesCredit Derivatives Not InsuranceGlobalMacroForumNo ratings yet

- What Is A Subprime Mortgage?Document5 pagesWhat Is A Subprime Mortgage?Chigo RamosNo ratings yet

- Credit Default Swaps and GFC-C2D2Document5 pagesCredit Default Swaps and GFC-C2D2michnhiNo ratings yet

- Mono 2009 M As09 1 DarcyDocument62 pagesMono 2009 M As09 1 DarcyKapil AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Credit Default Swaps: Project On Financial Management IiDocument27 pagesCredit Default Swaps: Project On Financial Management IiPratik ReshamwalaNo ratings yet

- Foreclosure Fraud Securitization ProcessDocument5 pagesForeclosure Fraud Securitization ProcessRoseNo ratings yet

- Credit Default SwapsDocument4 pagesCredit Default SwapsAbhijeit BhosaleNo ratings yet

- The Financial Crisis of 2007 - Roles of CDOs, CDSs and Subprime MortgagesDocument25 pagesThe Financial Crisis of 2007 - Roles of CDOs, CDSs and Subprime MortgagesSertaç Yay100% (1)

- Not InsuranceDocument3 pagesNot InsuranceKritiNo ratings yet

- Surety PricingDocument21 pagesSurety PricingMarian GrajdanNo ratings yet

- Research Paper For Credit CrisisDocument31 pagesResearch Paper For Credit CrisisShabana KhanNo ratings yet

- Credit Default Swaps and The Credit Crisis: René M. StulzDocument21 pagesCredit Default Swaps and The Credit Crisis: René M. StulzRenjie XuNo ratings yet

- Jahangirnagar University: Merchant and Investment Banking 1.0 Investment BankingDocument5 pagesJahangirnagar University: Merchant and Investment Banking 1.0 Investment BankingFarjana Hossain DharaNo ratings yet

- Ignou Mba MsDocument22 pagesIgnou Mba MssamuelkishNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument7 pagesProjectmalik waseemNo ratings yet

- TiconderogaDocument5 pagesTiconderogaJCGonzales100% (1)

- Financial Derivatives Lessons From The Subprime CrisisDocument13 pagesFinancial Derivatives Lessons From The Subprime CrisisTytyt TyyNo ratings yet

- Finshastra January 2011 Volume 1Document17 pagesFinshastra January 2011 Volume 1Sarthak ParnamiNo ratings yet

- Credit Default SwapsDocument18 pagesCredit Default SwapsBhawin PatelNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument3 pagesDocumentjasvindersinghsagguNo ratings yet

- Need Plans Are Now Included As Part of Securities, Even: Articles From Fr. GusDocument12 pagesNeed Plans Are Now Included As Part of Securities, Even: Articles From Fr. GusbittersweetlemonsNo ratings yet

- Umerchapra Global Fin Crisis-Can Islamic Finance HelpDocument6 pagesUmerchapra Global Fin Crisis-Can Islamic Finance HelpCANDERANo ratings yet

- Nordisk Försäkringstidskrift - A CAT Bond Primer For Investors and Insurers - 2009-12-02Document5 pagesNordisk Försäkringstidskrift - A CAT Bond Primer For Investors and Insurers - 2009-12-02afbasjkfjbkNo ratings yet

- Investment TermpaperDocument9 pagesInvestment TermpaperMichael HessNo ratings yet

- The Future of Securitization: Born Free, But Living With More Adult SupervisionDocument7 pagesThe Future of Securitization: Born Free, But Living With More Adult Supervisionsss1453100% (1)

- American International GroupDocument3 pagesAmerican International GroupJameil JosephNo ratings yet

- The Sub-Prime Mortgage Crisis & DerivativesDocument10 pagesThe Sub-Prime Mortgage Crisis & DerivativesChen XinNo ratings yet

- Counter Party Risk IntermediationDocument12 pagesCounter Party Risk IntermediationGunpreet ChahalNo ratings yet

- Securitization Us CrisisDocument56 pagesSecuritization Us CrisisRahul Gautam BhadangeNo ratings yet

- Synthetics and The Current AcctDocument6 pagesSynthetics and The Current AcctcsissokoNo ratings yet

- Credit Default SwapsDocument4 pagesCredit Default SwapsDmitriy YNo ratings yet

- Securitization FactsDocument60 pagesSecuritization FactsHelpin HandNo ratings yet

- NewMethodForGSE RiskTransfer-MalayBansalDocument10 pagesNewMethodForGSE RiskTransfer-MalayBansaldocs22No ratings yet

- What Is CDSDocument1 pageWhat Is CDSPrashant LandgeNo ratings yet

- Thesis Credit Default SwapsDocument7 pagesThesis Credit Default Swapsjessicaoatisneworleans100% (2)

- Insurance CompanyDocument54 pagesInsurance CompanyDhoni KhanNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of InterestDocument24 pagesConflicts of InterestXiang KangleiNo ratings yet

- Managing The Liquidity CrisisDocument8 pagesManaging The Liquidity CrisisRusdi RuslyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document23 pagesChapter 5Raymond Behnke [STUDENT]No ratings yet

- 5 - Eco749b - Ethics - 0 - Financial RegulationsDocument66 pages5 - Eco749b - Ethics - 0 - Financial Regulationsbabie naaNo ratings yet

- Iaqf Competition PaperDocument10 pagesIaqf Competition Paperapi-262753233No ratings yet

- SecuritizationDocument146 pagesSecuritizationSaurabh ParasharNo ratings yet

- Loan SyndicationDocument57 pagesLoan SyndicationSandya Gundeti100% (1)

- S L I A L: Ecuritization of IFE Nsurance Ssets AND IabilitiesDocument34 pagesS L I A L: Ecuritization of IFE Nsurance Ssets AND IabilitiesTejaswiniNo ratings yet

- Nature and Importance InsuranceDocument54 pagesNature and Importance Insurancejakowan0% (2)

- Steven Glaze Presented How Home Improvement Can Ease Your Pain.Document34 pagesSteven Glaze Presented How Home Improvement Can Ease Your Pain.StevenGlazeKansasCityNo ratings yet

- Lecture 7 - Structured Finance (CDO, CLO, MBS, Abl, Abs) : Investment BankingDocument10 pagesLecture 7 - Structured Finance (CDO, CLO, MBS, Abl, Abs) : Investment BankingJack JacintoNo ratings yet

- The Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationFrom EverandThe Great Recession: The burst of the property bubble and the excesses of speculationNo ratings yet

- FinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsFrom EverandFinTech Rising: Navigating the maze of US & EU regulationsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Leveraged Financial Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Loans, Bonds, and Other High-Yield InstrumentsFrom EverandLeveraged Financial Markets: A Comprehensive Guide to Loans, Bonds, and Other High-Yield InstrumentsNo ratings yet

- Life Settlements and Longevity Structures: Pricing and Risk ManagementFrom EverandLife Settlements and Longevity Structures: Pricing and Risk ManagementNo ratings yet

- Personal Finance BasicsDocument27 pagesPersonal Finance BasicsIvan MendesNo ratings yet

- A Kantian Approach To Recreational DrugsDocument10 pagesA Kantian Approach To Recreational DrugsIvan MendesNo ratings yet

- "Conscious Capitalism" - John Mackey of Whole Foods MarketDocument7 pages"Conscious Capitalism" - John Mackey of Whole Foods MarketIvan MendesNo ratings yet

- Conscious Capitalism WFMDocument7 pagesConscious Capitalism WFMIvan MendesNo ratings yet

- Topic 1 Introduction To Business FinanceDocument12 pagesTopic 1 Introduction To Business FinancechuacasNo ratings yet

- Project On Strategic Marketing: Saintgits Institute of Management KottayamDocument4 pagesProject On Strategic Marketing: Saintgits Institute of Management KottayamKAILAS S NATH MBA19-21No ratings yet

- CAPITAL MARKET-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesCAPITAL MARKET-WPS Officeprinceuduma2021No ratings yet

- DP 28011Document401 pagesDP 28011sandeepNo ratings yet

- Bombay Stock ExchangeDocument4 pagesBombay Stock Exchangesatwinder sidhuNo ratings yet

- Ch. 13 Financial Risk Management (Part 1)Document5 pagesCh. 13 Financial Risk Management (Part 1)Daud AminNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two The Financial Services Industry: Depository InstitutionsDocument10 pagesChapter Two The Financial Services Industry: Depository InstitutionsShahed AlamNo ratings yet

- CSXDocument130 pagesCSXmarcelluxNo ratings yet

- Final Report - Ankita SinhaDocument78 pagesFinal Report - Ankita SinhaAnonymous Pd1RunU28No ratings yet

- Quality Dividend Yield Stocks - 301216Document5 pagesQuality Dividend Yield Stocks - 301216sumit guptaNo ratings yet

- CFTC BinanceDocument74 pagesCFTC BinanceZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- Project ReportDocument91 pagesProject ReportSunil BhatiaNo ratings yet

- Reserve Bank of India: Systemically Important Core Investment CompaniesDocument19 pagesReserve Bank of India: Systemically Important Core Investment CompaniesBhanu prasanna kumarNo ratings yet

- Market RiskDocument22 pagesMarket RiskAkhil UchilNo ratings yet

- Sujide, Kendrew Statement of Comprehensive IncomeDocument5 pagesSujide, Kendrew Statement of Comprehensive IncomeKendrew SujideNo ratings yet

- Euronext Cash Markets - Optiq OEG Client Specifications - FIX 5.0 Interface - v1.7.0 - FOR FUTURE USE - 0Document212 pagesEuronext Cash Markets - Optiq OEG Client Specifications - FIX 5.0 Interface - v1.7.0 - FOR FUTURE USE - 0BobNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Intermediate Accounting 2 2021Document19 pagesSyllabus Intermediate Accounting 2 2021John Lucky MacalaladNo ratings yet

- Mock Test 3Document23 pagesMock Test 3Shyam KaithwasNo ratings yet

- Equity in The Time Series, Part 2: 15.433 Financial Markets October 3 & 5, 2017Document54 pagesEquity in The Time Series, Part 2: 15.433 Financial Markets October 3 & 5, 2017Joe23232232No ratings yet

- 03 - Interest Rate DerivativesDocument65 pages03 - Interest Rate DerivativesRonnie KurtzbardNo ratings yet

- FINMA Risikomonitor 2020Document20 pagesFINMA Risikomonitor 2020AleAleNo ratings yet

- 2020 Vision11Document98 pages2020 Vision11derektennant100% (2)

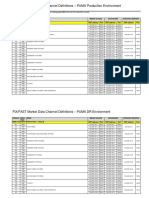

- FIX/FAST Market Data Channel Definitions - PUMA Production EnvironmentDocument3 pagesFIX/FAST Market Data Channel Definitions - PUMA Production EnvironmentVaibhav PoddarNo ratings yet

- Unit 1-Financial ManagementDocument66 pagesUnit 1-Financial ManagementAshwini shenolkarNo ratings yet

- 13 08 20 Final Capital Market ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITYDocument2 pages13 08 20 Final Capital Market ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITYchere100% (2)

- Paper 14 NewDocument655 pagesPaper 14 NewjesurajajosephNo ratings yet

- Library ListDocument6 pagesLibrary Listkiran5389No ratings yet

- AIMA Journal: Alternative Investment Management AssociationDocument32 pagesAIMA Journal: Alternative Investment Management Associationhttp://besthedgefund.blogspot.comNo ratings yet

- Crypto Exchanges in 2021 - ChainalysisDocument16 pagesCrypto Exchanges in 2021 - ChainalysisRedvirus2007No ratings yet