Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Canon of Exhibition

Canon of Exhibition

Uploaded by

Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Peter Van Mensh On ExhibitionsDocument16 pagesPeter Van Mensh On ExhibitionsAnna LeshchenkoNo ratings yet

- Community and Communication in Modern Art PDFDocument4 pagesCommunity and Communication in Modern Art PDFAlumno Xochimilco GUADALUPE CECILIA MERCADO VALADEZNo ratings yet

- Main IdeaDocument13 pagesMain IdeaPatthamaporn Khemma50% (2)

- The Fisher King WoundDocument6 pagesThe Fisher King WoundEdward L Hester100% (2)

- Hoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroDocument4 pagesHoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroVal RavagliaNo ratings yet

- Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary ArtFrom EverandCollecting the New: Museums and Contemporary ArtRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Rosalind Krauss - Sense and Sensibility. Reflection On Post '60's SculptureDocument11 pagesRosalind Krauss - Sense and Sensibility. Reflection On Post '60's SculptureEgor Sofronov100% (1)

- A Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingDocument10 pagesA Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingLarisa Crunţeanu100% (1)

- PAFA's Deaccessions' Exhibition HistoriesDocument3 pagesPAFA's Deaccessions' Exhibition HistoriesLee Rosenbaum, CultureGrrlNo ratings yet

- A Subjective Take On Collective CuratingDocument8 pagesA Subjective Take On Collective CuratingCarmen AvramNo ratings yet

- Rugoff EDSDocument4 pagesRugoff EDSTommy DoyleNo ratings yet

- Respini Slippery Delays PDFDocument11 pagesRespini Slippery Delays PDFJuan Esteban Arias A.No ratings yet

- Vidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldDocument5 pagesVidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldTeodora IojibanNo ratings yet

- Issues of Culture, Nationhood & Identity in Modern Malaysia ArtDocument22 pagesIssues of Culture, Nationhood & Identity in Modern Malaysia ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi50% (2)

- AR& Inventory Management AR& Inventory ManagementDocument11 pagesAR& Inventory Management AR& Inventory Managementchesca marie penarandaNo ratings yet

- 5D Model of The Counselling ProcessDocument9 pages5D Model of The Counselling ProcessAthira SurendranNo ratings yet

- High Concept Scorecard WDDocument3 pagesHigh Concept Scorecard WDViruss Xian SpearNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan-Chapter 12-Antebellum Culture and ReformDocument39 pagesUnit Plan-Chapter 12-Antebellum Culture and Reformapi-237585847No ratings yet

- History of Exhibitions Curatorial Models PDFDocument9 pagesHistory of Exhibitions Curatorial Models PDFregomescardosoNo ratings yet

- The Evolving Role of The Exhibition and Its Impact On Art and Cul PDFDocument116 pagesThe Evolving Role of The Exhibition and Its Impact On Art and Cul PDFIolanda Anastasiei100% (2)

- Structure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldFrom EverandStructure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldNo ratings yet

- The Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumFrom EverandThe Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Toward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtDocument20 pagesToward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtDanial Shoukat100% (1)

- When Attitudes Became FormDocument5 pagesWhen Attitudes Became FormMihai SpacovschiNo ratings yet

- ENLIGHTENING THE BRITISH Knowledge, Discovery and The Museum in The Eighteenth Century Edited by R.G.W. Anderson, M L - Caygill, A.G. MacGregor and L Syson (2004) - (Just The Table of Contents)Document3 pagesENLIGHTENING THE BRITISH Knowledge, Discovery and The Museum in The Eighteenth Century Edited by R.G.W. Anderson, M L - Caygill, A.G. MacGregor and L Syson (2004) - (Just The Table of Contents)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Otto PachtDocument18 pagesOtto PachtLorena AreizaNo ratings yet

- Art History After Modernism BeltingsDocument1 pageArt History After Modernism BeltingsIrena Lazovska100% (1)

- Burger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4Document15 pagesBurger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4monkeys8823No ratings yet

- Grundberg The Crisis of The RealDocument21 pagesGrundberg The Crisis of The Realsathis_nsk100% (3)

- Carol Duncan Who Rules The Art World 1983Document11 pagesCarol Duncan Who Rules The Art World 1983Lillian TrinhNo ratings yet

- Leo Bersani Subject and PowerDocument21 pagesLeo Bersani Subject and PowerNikola At Niko100% (1)

- JJ 14 EightiesDocument79 pagesJJ 14 Eightiesshenkle9338No ratings yet

- The Exhibitionary Complex-SiddhiDocument4 pagesThe Exhibitionary Complex-Siddhisiddhi patilNo ratings yet

- Positively White Cube RevisitedDocument4 pagesPositively White Cube RevisitedeleendeprezNo ratings yet

- P4 Aroon Puritat PDFDocument14 pagesP4 Aroon Puritat PDFLê KhánhNo ratings yet

- Mitchell - World As ExhibitionDocument21 pagesMitchell - World As Exhibitionjen-leeNo ratings yet

- CCA, Lagos Newsletter N°11 (@version)Document7 pagesCCA, Lagos Newsletter N°11 (@version)Oyindamola Layo FakeyeNo ratings yet

- Operating As A Curator: An Interview With Maria LindDocument7 pagesOperating As A Curator: An Interview With Maria LindtomisnellmanNo ratings yet

- 2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMDocument187 pages2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Dark Heritage Tourism and The Sarajevo SiegeDocument16 pagesDark Heritage Tourism and The Sarajevo SiegeTakuya MommaNo ratings yet

- K Gaskill - Curatorial CulturesDocument9 pagesK Gaskill - Curatorial Culturesaalexx17No ratings yet

- FOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsDocument30 pagesFOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsjanNo ratings yet

- The German Werkbund and Development of Bauhaus - Nalin Bhatia, 3-B Roll, No. 21Document7 pagesThe German Werkbund and Development of Bauhaus - Nalin Bhatia, 3-B Roll, No. 21Nalin Bhatia100% (2)

- The Postcolonial Constellation Contemporary Art in A State of Permanent TransitionDocument27 pagesThe Postcolonial Constellation Contemporary Art in A State of Permanent TransitionRoselin R Espinosa100% (1)

- The Curator As Arts Administrator? Comments On Harald Szeemann and The Exhibition "When Attitudes Become Form"Document18 pagesThe Curator As Arts Administrator? Comments On Harald Szeemann and The Exhibition "When Attitudes Become Form"Cecilia LeeNo ratings yet

- Manifesta Journal PDFDocument71 pagesManifesta Journal PDFmarkoNo ratings yet

- Hippies and Their Impact On Nepalese SocietyDocument4 pagesHippies and Their Impact On Nepalese SocietyKushal DuwadiNo ratings yet

- Cindy Sherman IntroDocument21 pagesCindy Sherman IntroSandro Alves Silveira100% (1)

- 2022 Reflections For Reframing The TabooDocument144 pages2022 Reflections For Reframing The Taboo722sd2ftyjNo ratings yet

- MUITO IMPORTANTE L - STEEDS - What - Is - The - Future - of - Exhibition - HistorDocument15 pagesMUITO IMPORTANTE L - STEEDS - What - Is - The - Future - of - Exhibition - HistorMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFDocument64 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFFelipe PrandoNo ratings yet

- !.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1Document4 pages!.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1tendermangomangoNo ratings yet

- A World Art History and Its ObjectsDocument5 pagesA World Art History and Its ObjectschnnnnaNo ratings yet

- From The Cabinet of Curiosities, To The MuseumDocument6 pagesFrom The Cabinet of Curiosities, To The Museumarchificial100% (2)

- Gardner-Green - South As MethodBiennials Past and PresentDocument9 pagesGardner-Green - South As MethodBiennials Past and PresentFriezsONo ratings yet

- 18s 1806 Curating SYLLABUS FinalDocument11 pages18s 1806 Curating SYLLABUS FinalccapersNo ratings yet

- Decentering Modernism - Art History and Avant-Garde Art From The PeripheryDocument19 pagesDecentering Modernism - Art History and Avant-Garde Art From The Peripheryleaaa51100% (1)

- OrdinaryDocument29 pagesOrdinaryijfortunoNo ratings yet

- John Dewey and Museum EducationDocument15 pagesJohn Dewey and Museum EducationJoão Paulo AndradeNo ratings yet

- Art and PoliticsDocument15 pagesArt and Politicsis taken readyNo ratings yet

- Alloway, Rosler, Et Al - The Idea of The Post-ModernDocument32 pagesAlloway, Rosler, Et Al - The Idea of The Post-ModernAndrea GyorodyNo ratings yet

- A New World Art? Documenta 11Document13 pagesA New World Art? Documenta 11Mihail Eryvan100% (1)

- 2015 Hal Foster Exhibitionists (LRB)Document6 pages2015 Hal Foster Exhibitionists (LRB)Iván D. Marifil Martinez100% (1)

- Kitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsDocument15 pagesKitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsAna Sánchez Trolliet100% (1)

- Moulding The Museum MediumDocument154 pagesMoulding The Museum MediumHelena Santiago VigataNo ratings yet

- Artist's Work Artist's Voice PicassoDocument35 pagesArtist's Work Artist's Voice PicassoTrill_MoNo ratings yet

- Urban Experiences Museumification and TDocument45 pagesUrban Experiences Museumification and TWeronika CiosekNo ratings yet

- What Is This Music? Auteur Music in The Films of Wes AndersonDocument263 pagesWhat Is This Music? Auteur Music in The Films of Wes AndersonAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Biennalogy:Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal & Solveig Ovstebo PDFDocument10 pagesBiennalogy:Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal & Solveig Ovstebo PDFAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Shooshie SulaimanDocument14 pagesShooshie SulaimanAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- MullerDocument13 pagesMullerAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Decentralized PDFDocument38 pagesDecentralized PDFAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Document16 pagesNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Art of CurationDocument6 pagesThe Art of CurationAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Authentic: Adulterated Artifacts - Material Culture and Ethnicity in Contemporary Java and IfugaoDocument23 pagesAuthentic: Adulterated Artifacts - Material Culture and Ethnicity in Contemporary Java and IfugaoAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Ismail Zain Art - A Different Vision On Malaysian Contemporary ArtDocument22 pagesThe Nature of Ismail Zain Art - A Different Vision On Malaysian Contemporary ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi100% (2)

- Modern & Contemporary Asian Art - A Working BibiliographyDocument211 pagesModern & Contemporary Asian Art - A Working BibiliographyAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Asia Pacific Art Museums A BibliographyDocument30 pagesContemporary Asia Pacific Art Museums A BibliographyAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi100% (1)

- Cocktails Will Be Served - Observing The Dynamics of The Southeast Asian Art MarketDocument17 pagesCocktails Will Be Served - Observing The Dynamics of The Southeast Asian Art MarketAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Play in Malaysian ArtDocument6 pagesThe Politics of Play in Malaysian ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Writing Grant ProposalDocument2 pagesWriting Grant ProposalAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- 8 Nov 2014Document152 pages8 Nov 2014Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Ethics & Politics of Curating in Southeast AsiaDocument6 pagesEthics & Politics of Curating in Southeast AsiaAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To AnarchismDocument7 pagesIntroduction To AnarchismAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Tariff: Negative Consequences of TarrifDocument9 pagesTariff: Negative Consequences of TarrifAbby NavarroNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Tools For Business Decision Making 7th Edition Kimmel Test BankDocument36 pagesFinancial Accounting Tools For Business Decision Making 7th Edition Kimmel Test Bankhopehigginslup31100% (25)

- Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4: School Grade Level Teacher Teaching Date Sections Learning AreaDocument13 pagesDay 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4: School Grade Level Teacher Teaching Date Sections Learning AreaarlenestamariaNo ratings yet

- Density Functional Theory QuantumDocument282 pagesDensity Functional Theory QuantumMichael Parker50% (2)

- Characteristics of Transportation As A ProductDocument10 pagesCharacteristics of Transportation As A ProductSushmita Hatulan50% (2)

- 0.1 Simple Pump Model Theory: n+1 N N n+1 NDocument4 pages0.1 Simple Pump Model Theory: n+1 N N n+1 NJack CavaluzziNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Neo Platonic Artist As An IdDocument33 pagesRenaissance Neo Platonic Artist As An IdRm ResurgamNo ratings yet

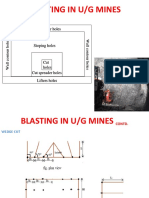

- Blasting in U/G Mines: Roof Contour Holes Roof Contour HolesDocument10 pagesBlasting in U/G Mines: Roof Contour Holes Roof Contour HolesSiddharth MukhillaNo ratings yet

- Control M em MigrationDocument76 pagesControl M em Migrationis3khar0% (1)

- General Explanation of The Straight Wire Appliance in The Treatment of Young People and AdultsDocument8 pagesGeneral Explanation of The Straight Wire Appliance in The Treatment of Young People and AdultsIrina PiscucNo ratings yet

- Master Your Minutes Mini - UpdatedDocument12 pagesMaster Your Minutes Mini - UpdatedPongnateeNo ratings yet

- Mahalakshmi Ashtakam Stotra in HindiDocument3 pagesMahalakshmi Ashtakam Stotra in HindiAnuja BakareNo ratings yet

- Rizal Module 3Document3 pagesRizal Module 3Geleu PagutayaoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Processes: Bucky J. DoddDocument14 pagesCurriculum Design Processes: Bucky J. DoddPatty BoneoNo ratings yet

- National Certificate Ii - Optional Skill Module - Bread and Pastry Production PDFDocument116 pagesNational Certificate Ii - Optional Skill Module - Bread and Pastry Production PDFMicol Villaflor ÜNo ratings yet

- AWNMag6 02Document57 pagesAWNMag6 02Michał MrózNo ratings yet

- Demo Company - Security Assessment Findings ReportDocument14 pagesDemo Company - Security Assessment Findings ReportShashankRaghavNo ratings yet

- 4 SignsDocument3 pages4 SignsJonathan GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Mechanics of Writing (Punctuation)Document15 pagesLesson 1 - Mechanics of Writing (Punctuation)Arvin NovalesNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Manner and Adverbs Used in ComparisonsDocument10 pagesAdverbs of Manner and Adverbs Used in Comparisonsbáh_leeNo ratings yet

- Bawang Merah Bawang PutihDocument3 pagesBawang Merah Bawang Putihzulfarahma50% (2)

- Primer Access To Justice PDFDocument17 pagesPrimer Access To Justice PDFaddieNo ratings yet

- Present Simple Vs Present Continuous - 81456Document2 pagesPresent Simple Vs Present Continuous - 81456FlorinCristudorNo ratings yet

- Inspirations Fall 2013-11-04Document40 pagesInspirations Fall 2013-11-04karen_gn78786No ratings yet

Canon of Exhibition

Canon of Exhibition

Uploaded by

Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Canon of Exhibition

Canon of Exhibition

Uploaded by

Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiCopyright:

Available Formats

XV.

C

A CANON OF EXHIBITIONS (excerpts) published in Manifesta Journal 11: The Canon of Curating, 2011

Discussion of an exhibitionary canon is something new. And it is new because the serious study of exhibitions is

something new, or at least relatively new. Two factors have driven recent research and publication on exhibitions: the changing landscape of art history, with its expanding interests in social and institutional histories, and,

perhaps more importantly, the curatorial boom of the late 1980s and 1990s. With the latter has come interest in

historical exemplars, along with the creation of academic programs in curatorial practice that demand historical

cases to study. Certainly there had been books that presented the history of particular exhibitions, such as Milton

Browns volume on The Armory Show, or histories of a group of exhibitions, such as Ian Dunlops account of seven important modern art shows. 1 But these studies were relatively few in number, and the remaining literature,

which was not large, was found primarily in academic journals and volumes aimed at a specialist audience 2.

It was this scarcity of information that prompted my own research on exhibitions while working at Zabriskie

Gallery, New York, where I found my curiosity frustrated during our show of surrealist objects from 1936. That

year was marked by three important exhibitions of Surrealism, shows mounted at the New Burlington Galleries in

London, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Galerie Charles Ratton in Paris. But while these shows

often were mentioned in discussions of Surrealism, I was unable to find detailed information on them. My interest

in these exhibitions and others, prompted by the gallerys turn of its attention to the work of the French Nouveaux

Ralistes, eventually led to my writing a book on twentieth-century art presented through accounts of major

exhibitions. 3 And in publishing The Avant-Garde in Exhibition, unbeknownst to myself, I was participating in the

creation of a canon of exhibitions. (...)

The idea of a canon is that of a standard against which objects of a given kind are measured or evaluated. 4 But

before discussing why a show would, or should, be included in an exhibitionary canon, it is important to consider

how such a canon is used, to consider the purposes of designating certain exhibitions as canonical. And when we

consider purposes, we must consider purposes for whom. In 1983 the editor of an issue of Critical Inquiry that

was devoted to the literary canon identified a number of ways in which canons would be discussed: as determined

by artists through choice of stylistic models and figures of emulation, as constructed by literary and academic

critics, and as governing intellectual and scholastic study. 5

These perspectives are not unrelated, as we see in the stimulus that the establishment of curatorial training programs has given to the historical study of exhibitions. But just as artists look at artworks from a different angle

than do art historiansnot ignoring what historians note and appreciate, but thinking also about how they can

employ what they see in their artistic practiceso curators are concerned to take from the experience and study

of exhibition ideas to be incorporated in their curatorial work. In considering a canon of exhibitions, then, a given

exhibition might be marked as canonical for, say, exhibition-makers as practitioners but not for those assessing

these shows as historians or critics. Here canons would be viewed as relative to the uses to which they are put,

with different canons constructed to serve different interests, just as it has been suggested that there could be

separate feminist, Marxist, or postcolonial canons of art. 6

This point about use complements the distinction between exhibitions taken to be canonical in terms of their

art historical significance and those that are judged to be canonical with regard to curatorial innovation. 7 One

natural way of making this distinction is to view the former as central to the history of art in their presentation of

noteworthy artworks; such exhibitions often are connected with the introduction to various publics of works by

particular artists or of new kinds of artistic practice. 8 One thinks immediately of such classic group shows of

modern art as the concentration of the Fauves in room seven of the 1905 Salon dAutomne, the first Blaue Reiter

exhibition in Munich in 1911, the 1913 Armory Shows presentation of European modern art in New York, Chicago,

and Boston, and 010: The Last Futurist Exhibition of Pictures, which included distinctive displays of Malevichs

Suprematist paintings and Tatlins corner counter-reliefs, in Saint Petersburg (1915); one then also thinks of

later exhibitions such as, to mention only some New York postwar examples, Dorothy Millers Sixteen Americans at the Museum of Modern Art in 1959, which introduced Frank Stellas black paintings, Kynaston McShines

Primary Structures at the Jewish Museum, Lucy Lippards Eccentric Abstraction at Fischbach Gallery in 1966,

and Douglas Crimps 1977 Pictures exhibition at Artists Space. And of course many single-artist exhibitions fall

into this category. Shows that are judged to be canonical with regard to curatorial considerations, on the other

hand, are marked as important for introducing or developing new ways in which artworks are presented, and they

exemplify different varieties of innovation. Most general are changes in how we conceive of what an exhibition is,

such as the notion often associated with Harald Szeemann of exhibitions as creative works in their own right. 9

But curatorial innovation usually is more specific, relating, to mention only a few modes, to forms of display (the

Abstraktes Kabinett commissioned by Alexander Dorner and designed in 19271928 by El Lissitzky for the Landesmuseum in Hannover, and the 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surralisme in Paris), to expanded notions of

the Despite the association of the idea of the canonical with much-critiqued traditional art history, and no matter

how committed one is to a critical standpoint, a canon of exhibitions is not something that we should, avoid.

This is for the simple reason that if we are to teach courses about exhibitions, if we are to include their study

in a broader art and cultural history, then we must select particular exhibitions on which to focus. exhibitionary site (First Gutai Outdoor Exhibition, Ashiya, Japan, 1955, and Seth Siegelaubs catalogue exhibitions

of 19681969), to temporal structure (Hans Ulrich Obrist and Hou Hanrus developing Cities on the Move,

19971999, and Okwui Enwezors multiple platform Documenta 11, 20012002), and to the curatorial process

itself (Andy Warhols 1970 indiscriminate mining of the storage rooms of the Rhode Island School of Design

Museum of Art for Raid the Icebox, and Francesco Bonamis delegation to others the curating of the nonnational section of the 2003 Venice Biennale). And some exhibitions, for example the 1920 Berlin Dada-Messe

(Dada fair), can be considered to be canonical for both art historical and curatorial reasons. 10 (...)

Since I began writing about the history of exhibitions, and especially while selecting shows to be documented

in the two volumes of Salon to Biennial, I have been asked about my reasons for focusing on these particular cases. While I recognize that my work has contributed to a process of canon formation, I am unable to

construct a fixed set of criteria for designating an exhibition as canonical. Because exhibitions function across

multiple dimensions, linking individuals and objects that play diverse roles within many complex networks,

the attempt to formulate a rigorous system of comparison seems futile. Instead, and simply put, canonical

exhibitions for me are those whose study yields the richest narratives. These are the narratives that connect

in the most illuminating way interesting and important artworks and institutions, artists and other actors,

personal and formal stories, and economic and political structures and events, displaying the centrality of

exhibitions in the public and the private life of culture.

While it can be used for purposes of constraint and limitation, the designating of particular exhibitions as

canonical is expansive as well. We can see this in the way that accounts of major shows have stimulated research on other exhibitions and inspired creative curatorial efforts. But, in addition, such expansiveness appears

when study and new ideation react against an existing canon instead of reinforcing it. For canons are dynamic

constructs, their identification taking the form of absolute judgments but functioning also as springboards to

further conversation and inquiry. Like exhibitions, they are nodes in structures of transaction and value. And

the study of canons, like that of exhibitions, has much to teach us about the systems of which they are a part.

But that is another story.

NOTES

1. Milton Brown, The Story of the Armory Show (New York: Abbeville Press, 1988); and Ian Dunlop, The Shock of the

New: Seven Historic Exhibitions of Modern Art (London: Weidenfield and Nicolson, 1972). An earlier example is Kenneth W. Luckhurst, The Story of Exhibitions (London: Studio Publications, 1951).

2. A scholarly resource of particular significance is Donald E. Gordons Modern Art Exhibitions: 19001916, 2 vols.

(Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1974), a monumental effort seeking to list every work shown in exhibitions of modern art

during these years. Among specialist works on early modern exhibition history, exemplary are those of Patricia

Mainardi and Martha Ward; the work of Walter Grasskamp on Documenta is an important precedent for research on

more recent shows. A noteworthy exception to the lack of material available for both specialist and general public was

the 1988 exhibition at the Martin Gropius Bau in Berlin and the accompanying publication, Stationen der Moderne: Die

bedeutendsten Kunstausstellungen des 20. Jahrhunderts in Deutschland (Berlin: Berlinische Galerie, 1988), which

documented twenty exhibitions held in Germany from 1910 to 1969.

3. Bruce Altshuler, The Avant-Garde in Exhibition: New Art in the 20th Century (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1994).

Appearing a few years earlier was an anthology of essays by scholars and curators on selected exhibitions: Bernd

Klser and Katharina Hegewisch, eds., Die Kunst der Ausstellung (Frankfurt: Insel Verlag, 1991).

4. Gill Perry and Colin Cunningham (eds.), Academies, Museums and Canons of Art (New Haven, CT: Yale University

Press, 1999), 12.

5. Robert von Hallberg, Editors Introduction, Critical Inquiry 10, no. 1 (September 1983): iiiiv.

6. Keith Moxey, Motivating History, Art Bulletin 77, no. 3 (September 1995): 400.

7. I thank Claire Bishop for emphasizing this distinction in conversation.

8. Here I focus on exhibitions of contemporary art, ignoring historical exhibitions that have been important to the field

of art history by assembling older works never seen alongside one another (or not united for many years), exploring

particular influences, displaying artworks previously unknown or little known, and so on.

9. Exhibitions instantiating this idea in the curatorial realm, of course, must be distinguished from those of artists who

have employed the exhibition as an artistic form, such as Marcel Broodthaerss Museum of Modern Art, Department

of Eagles (19681972), Douglas Blaus Fictions (1987), and Fred Wilsons Mining the Museum (19921993).

10. Many exhibitions that fall into both of these canonical groupings employ a form of display that is related in a

particularly close way to the works presented. On such shows, see my introduction to Salon to Biennial, Volume I:

18631959 (London: Phaidon, 2008), 18.

Fondazione Antonio Ratti, Villa Sucota, Via per Cernobbio, 19, 22100 Como, Italia. www.fondazioneratti.org

Tuesday, 29th November 2011 from 10 am to 7 pm

XV. CURATING THE MOST BEAUTIFUL KUNSTHALLE IN THE WORLD

BRUCE ALTSHULER

This presentation will discuss the idea of a canon of exhibitions and of the curators who create

them. First Bruce Altshuler will distinguish between exhibitions that are canonical for reasons

of their art-historical importance and those considered canonical for reasons of curatorial

innovation. The coherence of this distinction then will be questioned by looking at the history of

exhibitions as an essential part of Art History, and by considering the way in which exhibitions

play into broader accounts of culture and politics. With respect to the history of curating, and

the construction of a set of canonical curators, Bruce Altshuler will sketch a general account

of curating in the 20th century, and discuss the way in which curatorial practice is influenced

by awareness of moments of this history. Finally, he will discuss ways in which exhibitions and

curatorial activity might be evaluated for possible inclusion into a fluid canon.

Currently director of the Program in Museum

Studies at New York University, since some years

Bruce Altshuler has focused his interests on the

history of exhibitions and on analysis of the best

practices of museum management.

After earning a Ph.D. in Philosophy from Harvard

University, in the 1980s is introduced into the

world of contemporary art as associate director of

the Zabriskie Gallery in New York. These are the

years when Altshuler consolidates his knowledge

of art history in the twentieth century, a quality

that leads him first to become a member of the

Board of Directors of the Isamu Noguchi Foundation and later director of the museum until 1998.

From 1998 to 2000 he hold the position of Director

of Studies for the Graduate Programs and Vice

President of Christies Education in New York,

and in the same period he is Member of Board of

Directors for the International Association of Art

Critics / United States Section.

During his professional activity he has initially

concentrated his researches on both historical

avant-garde movements and postwar American

art, although in these last years he devote more

attention to curatorial issues and museum studies.

Especially relevant his close examinations on

exhibition that have made the history of the 900,

which was inaugurated with the release of the volume The Avant-Gard in Exhibition: New Art in the

Twentieth Century (N.Y., Harry N. Abrams 1994.

Berkeley, University of California Press, 1998).

The book published by Phaidon in 2008

Salon to Biennial: Exhibitions That Made Art

History, Volume 1: 1863 -1959 is the starting point of a story that will come to some

crucial moments of our days. Few years

before, in the volume Colletting the New:

Museums and Contemporary Art (2006,

Princeton University Press), Altshulers

attention is focused on the challenges of

museums to acquire and preserve contemporary art.

These issues are also briefly explored in

several essays in some magazines, such as

Manifesta Journal and Tate Etc.

You might also like

- Peter Van Mensh On ExhibitionsDocument16 pagesPeter Van Mensh On ExhibitionsAnna LeshchenkoNo ratings yet

- Community and Communication in Modern Art PDFDocument4 pagesCommunity and Communication in Modern Art PDFAlumno Xochimilco GUADALUPE CECILIA MERCADO VALADEZNo ratings yet

- Main IdeaDocument13 pagesMain IdeaPatthamaporn Khemma50% (2)

- The Fisher King WoundDocument6 pagesThe Fisher King WoundEdward L Hester100% (2)

- Hoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroDocument4 pagesHoffmann Jens - Other Primary Structures IntroVal RavagliaNo ratings yet

- Collecting the New: Museums and Contemporary ArtFrom EverandCollecting the New: Museums and Contemporary ArtRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Rosalind Krauss - Sense and Sensibility. Reflection On Post '60's SculptureDocument11 pagesRosalind Krauss - Sense and Sensibility. Reflection On Post '60's SculptureEgor Sofronov100% (1)

- A Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingDocument10 pagesA Brief Outline of The History of Exhibition MakingLarisa Crunţeanu100% (1)

- PAFA's Deaccessions' Exhibition HistoriesDocument3 pagesPAFA's Deaccessions' Exhibition HistoriesLee Rosenbaum, CultureGrrlNo ratings yet

- A Subjective Take On Collective CuratingDocument8 pagesA Subjective Take On Collective CuratingCarmen AvramNo ratings yet

- Rugoff EDSDocument4 pagesRugoff EDSTommy DoyleNo ratings yet

- Respini Slippery Delays PDFDocument11 pagesRespini Slippery Delays PDFJuan Esteban Arias A.No ratings yet

- Vidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldDocument5 pagesVidler - Architecture's Expanded FieldTeodora IojibanNo ratings yet

- Issues of Culture, Nationhood & Identity in Modern Malaysia ArtDocument22 pagesIssues of Culture, Nationhood & Identity in Modern Malaysia ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi50% (2)

- AR& Inventory Management AR& Inventory ManagementDocument11 pagesAR& Inventory Management AR& Inventory Managementchesca marie penarandaNo ratings yet

- 5D Model of The Counselling ProcessDocument9 pages5D Model of The Counselling ProcessAthira SurendranNo ratings yet

- High Concept Scorecard WDDocument3 pagesHigh Concept Scorecard WDViruss Xian SpearNo ratings yet

- Unit Plan-Chapter 12-Antebellum Culture and ReformDocument39 pagesUnit Plan-Chapter 12-Antebellum Culture and Reformapi-237585847No ratings yet

- History of Exhibitions Curatorial Models PDFDocument9 pagesHistory of Exhibitions Curatorial Models PDFregomescardosoNo ratings yet

- The Evolving Role of The Exhibition and Its Impact On Art and Cul PDFDocument116 pagesThe Evolving Role of The Exhibition and Its Impact On Art and Cul PDFIolanda Anastasiei100% (2)

- Structure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldFrom EverandStructure, Image, Ornament: Architectural Sculpture in the Greek WorldNo ratings yet

- The Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumFrom EverandThe Culture Factory: Architecture and the Contemporary Art MuseumRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Toward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtDocument20 pagesToward An Understanding of Sculpture As Public ArtDanial Shoukat100% (1)

- When Attitudes Became FormDocument5 pagesWhen Attitudes Became FormMihai SpacovschiNo ratings yet

- ENLIGHTENING THE BRITISH Knowledge, Discovery and The Museum in The Eighteenth Century Edited by R.G.W. Anderson, M L - Caygill, A.G. MacGregor and L Syson (2004) - (Just The Table of Contents)Document3 pagesENLIGHTENING THE BRITISH Knowledge, Discovery and The Museum in The Eighteenth Century Edited by R.G.W. Anderson, M L - Caygill, A.G. MacGregor and L Syson (2004) - (Just The Table of Contents)AbuAbdur-RazzaqAl-MisriNo ratings yet

- Otto PachtDocument18 pagesOtto PachtLorena AreizaNo ratings yet

- Art History After Modernism BeltingsDocument1 pageArt History After Modernism BeltingsIrena Lazovska100% (1)

- Burger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4Document15 pagesBurger - Theory of The Avant Garde Chap 4monkeys8823No ratings yet

- Grundberg The Crisis of The RealDocument21 pagesGrundberg The Crisis of The Realsathis_nsk100% (3)

- Carol Duncan Who Rules The Art World 1983Document11 pagesCarol Duncan Who Rules The Art World 1983Lillian TrinhNo ratings yet

- Leo Bersani Subject and PowerDocument21 pagesLeo Bersani Subject and PowerNikola At Niko100% (1)

- JJ 14 EightiesDocument79 pagesJJ 14 Eightiesshenkle9338No ratings yet

- The Exhibitionary Complex-SiddhiDocument4 pagesThe Exhibitionary Complex-Siddhisiddhi patilNo ratings yet

- Positively White Cube RevisitedDocument4 pagesPositively White Cube RevisitedeleendeprezNo ratings yet

- P4 Aroon Puritat PDFDocument14 pagesP4 Aroon Puritat PDFLê KhánhNo ratings yet

- Mitchell - World As ExhibitionDocument21 pagesMitchell - World As Exhibitionjen-leeNo ratings yet

- CCA, Lagos Newsletter N°11 (@version)Document7 pagesCCA, Lagos Newsletter N°11 (@version)Oyindamola Layo FakeyeNo ratings yet

- Operating As A Curator: An Interview With Maria LindDocument7 pagesOperating As A Curator: An Interview With Maria LindtomisnellmanNo ratings yet

- 2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMDocument187 pages2015 Publication Prospect - and - Perspectives ZKMMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Dark Heritage Tourism and The Sarajevo SiegeDocument16 pagesDark Heritage Tourism and The Sarajevo SiegeTakuya MommaNo ratings yet

- K Gaskill - Curatorial CulturesDocument9 pagesK Gaskill - Curatorial Culturesaalexx17No ratings yet

- FOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsDocument30 pagesFOSTER, Hal. An Art of Missing PartsjanNo ratings yet

- The German Werkbund and Development of Bauhaus - Nalin Bhatia, 3-B Roll, No. 21Document7 pagesThe German Werkbund and Development of Bauhaus - Nalin Bhatia, 3-B Roll, No. 21Nalin Bhatia100% (2)

- The Postcolonial Constellation Contemporary Art in A State of Permanent TransitionDocument27 pagesThe Postcolonial Constellation Contemporary Art in A State of Permanent TransitionRoselin R Espinosa100% (1)

- The Curator As Arts Administrator? Comments On Harald Szeemann and The Exhibition "When Attitudes Become Form"Document18 pagesThe Curator As Arts Administrator? Comments On Harald Szeemann and The Exhibition "When Attitudes Become Form"Cecilia LeeNo ratings yet

- Manifesta Journal PDFDocument71 pagesManifesta Journal PDFmarkoNo ratings yet

- Hippies and Their Impact On Nepalese SocietyDocument4 pagesHippies and Their Impact On Nepalese SocietyKushal DuwadiNo ratings yet

- Cindy Sherman IntroDocument21 pagesCindy Sherman IntroSandro Alves Silveira100% (1)

- 2022 Reflections For Reframing The TabooDocument144 pages2022 Reflections For Reframing The Taboo722sd2ftyjNo ratings yet

- MUITO IMPORTANTE L - STEEDS - What - Is - The - Future - of - Exhibition - HistorDocument15 pagesMUITO IMPORTANTE L - STEEDS - What - Is - The - Future - of - Exhibition - HistorMirtes OliveiraNo ratings yet

- The Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFDocument64 pagesThe Exhibitionist Issue 1 PDFFelipe PrandoNo ratings yet

- !.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1Document4 pages!.reading List - Curatorial Practice 1tendermangomangoNo ratings yet

- A World Art History and Its ObjectsDocument5 pagesA World Art History and Its ObjectschnnnnaNo ratings yet

- From The Cabinet of Curiosities, To The MuseumDocument6 pagesFrom The Cabinet of Curiosities, To The Museumarchificial100% (2)

- Gardner-Green - South As MethodBiennials Past and PresentDocument9 pagesGardner-Green - South As MethodBiennials Past and PresentFriezsONo ratings yet

- 18s 1806 Curating SYLLABUS FinalDocument11 pages18s 1806 Curating SYLLABUS FinalccapersNo ratings yet

- Decentering Modernism - Art History and Avant-Garde Art From The PeripheryDocument19 pagesDecentering Modernism - Art History and Avant-Garde Art From The Peripheryleaaa51100% (1)

- OrdinaryDocument29 pagesOrdinaryijfortunoNo ratings yet

- John Dewey and Museum EducationDocument15 pagesJohn Dewey and Museum EducationJoão Paulo AndradeNo ratings yet

- Art and PoliticsDocument15 pagesArt and Politicsis taken readyNo ratings yet

- Alloway, Rosler, Et Al - The Idea of The Post-ModernDocument32 pagesAlloway, Rosler, Et Al - The Idea of The Post-ModernAndrea GyorodyNo ratings yet

- A New World Art? Documenta 11Document13 pagesA New World Art? Documenta 11Mihail Eryvan100% (1)

- 2015 Hal Foster Exhibitionists (LRB)Document6 pages2015 Hal Foster Exhibitionists (LRB)Iván D. Marifil Martinez100% (1)

- Kitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsDocument15 pagesKitchin and Dodge - Rethinking MapsAna Sánchez Trolliet100% (1)

- Moulding The Museum MediumDocument154 pagesMoulding The Museum MediumHelena Santiago VigataNo ratings yet

- Artist's Work Artist's Voice PicassoDocument35 pagesArtist's Work Artist's Voice PicassoTrill_MoNo ratings yet

- Urban Experiences Museumification and TDocument45 pagesUrban Experiences Museumification and TWeronika CiosekNo ratings yet

- What Is This Music? Auteur Music in The Films of Wes AndersonDocument263 pagesWhat Is This Music? Auteur Music in The Films of Wes AndersonAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Biennalogy:Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal & Solveig Ovstebo PDFDocument10 pagesBiennalogy:Elena Filipovic, Marieke Van Hal & Solveig Ovstebo PDFAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Shooshie SulaimanDocument14 pagesShooshie SulaimanAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- MullerDocument13 pagesMullerAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Decentralized PDFDocument38 pagesDecentralized PDFAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Document16 pagesNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Art of CurationDocument6 pagesThe Art of CurationAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Authentic: Adulterated Artifacts - Material Culture and Ethnicity in Contemporary Java and IfugaoDocument23 pagesAuthentic: Adulterated Artifacts - Material Culture and Ethnicity in Contemporary Java and IfugaoAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Ismail Zain Art - A Different Vision On Malaysian Contemporary ArtDocument22 pagesThe Nature of Ismail Zain Art - A Different Vision On Malaysian Contemporary ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi100% (2)

- Modern & Contemporary Asian Art - A Working BibiliographyDocument211 pagesModern & Contemporary Asian Art - A Working BibiliographyAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Asia Pacific Art Museums A BibliographyDocument30 pagesContemporary Asia Pacific Art Museums A BibliographyAzzad Diah Ahmad Zabidi100% (1)

- Cocktails Will Be Served - Observing The Dynamics of The Southeast Asian Art MarketDocument17 pagesCocktails Will Be Served - Observing The Dynamics of The Southeast Asian Art MarketAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Play in Malaysian ArtDocument6 pagesThe Politics of Play in Malaysian ArtAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Writing Grant ProposalDocument2 pagesWriting Grant ProposalAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- 8 Nov 2014Document152 pages8 Nov 2014Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Ethics & Politics of Curating in Southeast AsiaDocument6 pagesEthics & Politics of Curating in Southeast AsiaAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Introduction To AnarchismDocument7 pagesIntroduction To AnarchismAzzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Tariff: Negative Consequences of TarrifDocument9 pagesTariff: Negative Consequences of TarrifAbby NavarroNo ratings yet

- Financial Accounting Tools For Business Decision Making 7th Edition Kimmel Test BankDocument36 pagesFinancial Accounting Tools For Business Decision Making 7th Edition Kimmel Test Bankhopehigginslup31100% (25)

- Day 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4: School Grade Level Teacher Teaching Date Sections Learning AreaDocument13 pagesDay 1 Day 2 Day 3 Day 4: School Grade Level Teacher Teaching Date Sections Learning AreaarlenestamariaNo ratings yet

- Density Functional Theory QuantumDocument282 pagesDensity Functional Theory QuantumMichael Parker50% (2)

- Characteristics of Transportation As A ProductDocument10 pagesCharacteristics of Transportation As A ProductSushmita Hatulan50% (2)

- 0.1 Simple Pump Model Theory: n+1 N N n+1 NDocument4 pages0.1 Simple Pump Model Theory: n+1 N N n+1 NJack CavaluzziNo ratings yet

- Renaissance Neo Platonic Artist As An IdDocument33 pagesRenaissance Neo Platonic Artist As An IdRm ResurgamNo ratings yet

- Blasting in U/G Mines: Roof Contour Holes Roof Contour HolesDocument10 pagesBlasting in U/G Mines: Roof Contour Holes Roof Contour HolesSiddharth MukhillaNo ratings yet

- Control M em MigrationDocument76 pagesControl M em Migrationis3khar0% (1)

- General Explanation of The Straight Wire Appliance in The Treatment of Young People and AdultsDocument8 pagesGeneral Explanation of The Straight Wire Appliance in The Treatment of Young People and AdultsIrina PiscucNo ratings yet

- Master Your Minutes Mini - UpdatedDocument12 pagesMaster Your Minutes Mini - UpdatedPongnateeNo ratings yet

- Mahalakshmi Ashtakam Stotra in HindiDocument3 pagesMahalakshmi Ashtakam Stotra in HindiAnuja BakareNo ratings yet

- Rizal Module 3Document3 pagesRizal Module 3Geleu PagutayaoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Design Processes: Bucky J. DoddDocument14 pagesCurriculum Design Processes: Bucky J. DoddPatty BoneoNo ratings yet

- National Certificate Ii - Optional Skill Module - Bread and Pastry Production PDFDocument116 pagesNational Certificate Ii - Optional Skill Module - Bread and Pastry Production PDFMicol Villaflor ÜNo ratings yet

- AWNMag6 02Document57 pagesAWNMag6 02Michał MrózNo ratings yet

- Demo Company - Security Assessment Findings ReportDocument14 pagesDemo Company - Security Assessment Findings ReportShashankRaghavNo ratings yet

- 4 SignsDocument3 pages4 SignsJonathan GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - Mechanics of Writing (Punctuation)Document15 pagesLesson 1 - Mechanics of Writing (Punctuation)Arvin NovalesNo ratings yet

- Adverbs of Manner and Adverbs Used in ComparisonsDocument10 pagesAdverbs of Manner and Adverbs Used in Comparisonsbáh_leeNo ratings yet

- Bawang Merah Bawang PutihDocument3 pagesBawang Merah Bawang Putihzulfarahma50% (2)

- Primer Access To Justice PDFDocument17 pagesPrimer Access To Justice PDFaddieNo ratings yet

- Present Simple Vs Present Continuous - 81456Document2 pagesPresent Simple Vs Present Continuous - 81456FlorinCristudorNo ratings yet

- Inspirations Fall 2013-11-04Document40 pagesInspirations Fall 2013-11-04karen_gn78786No ratings yet