Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Social Cost of Carbon

Social Cost of Carbon

Uploaded by

Anh Le0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views8 pagesSocial cost of carbon

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentSocial cost of carbon

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views8 pagesSocial Cost of Carbon

Social Cost of Carbon

Uploaded by

Anh LeSocial cost of carbon

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 8

The social cost of carbon is an increasingly important, yet

controversial, concept in the policy discussion of climate

change. This term designates the economic damages of

an additional ton of carbon dioxide emitted into the

atmosphere, which implies the societal benefits of climate

actions aiming at reduce the emissions. The SCC is

intended to capture the changes in, inter alia, net

agricultural

productivity,

human

health,

property

damages and the value of the eco-systems. The concept

came into spotlight when the U.S Government published

its first estimates of the societal benefits of reducing

carbon dioxide emissions in 2010. However, economists

and scientists have heavily criticized the economic

models used to derive these values for their empirical

weaknesses. Other researchers have also presented

alternative estimates but there has been no consensus on

what the correct value of SCC should be. The process to

derive SCC is an extremely complex and laden with

uncertainties.

The

SCC

is

often

estimated

using

integrated models that combine the insights drawn from

science and economics to stimulate the real-word factors.

Most important input parameters that are shared across

models are socioeconomic and emissions trajectories,

climate sensitivity, and discount rates. They differ in the

underlying assumption and value judgments.

Discount rates (Aggregation across time)

The discount rate is used in benefit-cost analyses to

compare values over time. Choosing the appropriate

discount rate is crucial to the calculation of SCC. As the

economic consequences of carbon dioxide emissions

occur over an exceptionally long-time horizon (the halflife of carbon dioxide approximates a hundred years), the

stream of the damages needs to be converted to the

current value using the discount rate. Because the time

scales are on the order of decades or centuries, the

discount rate can become extremely powerful and the

outcomes of the BCA become highly sensitive to the

minuscule variation in the discount rate.

The choices of discount rate are ripe with scientific,

economic, ethical and legal complexities. Confounding

factors include: the investment horizon is longer than any

the conventional timeframe to derive the rate of return

on capital; future generations have no say in the decisionmaking process; in comparison with intergenerational

horizon, intergenerational investment horizons implicates

greater uncertainty (Spellman, 2015).

In

intergenerational

discounting,

researchers

often

determine the social discount rate from two perspectives:

descriptive and prescriptive (Arrow et al., 1996). In the

former approach, discount rates should be inferred from

actual market behaviors whereas in the later approach,

they are established from ethical criteria and behavioral

evidence. Many respected economists tend to agree

Ramsey formula is a useful starting framework to

establish SCC but dispute about how to estimate Ramsey

parameters (Arrow et al., 2012).

r = + g

r: discount rate; : pure rate of time preference

: elasticity of marginal utility; g: per capita rate of

growth in consumption

The choice of , which is defined as the marginal rate of

substitution between present and future consumption

under the same consumption levels, is an ethical one. In

practice, The U.S interagency working group assigned a

zero to while in the Stern review is equal to 0.01. Many

economists including Ramsey assert that at the societal

level, the appropriate value should be 0. They contend it

is ethically indefensible to assume a positive number

since it implies the humanity will be extinct. The major

counter-argument questions the entire survival of the

human race and we should account for the possibility of

human extinction. Those who apply a positive value to

the pure rate of time preference tends to assume the

same degree of impatience of an individual within lives

can hold for a society of individuals across lives (Bergh

and Botzen, 2015).

It is due to the parallels between

human generations and different periods of a humans

life.

Another,

more

straightforward,

rationale

for

positive , refuses to view use as a measure of

individuals

impatience

but

as

the

inter-temporal

preferences regarding the welfare of future generations:

we seem to care more about generation 100 years from

now than those from 1000 years (Pearson, 2011).

The second composition of the Ramsey equation captures

the wealth effect. The central meaning of parameter

represents the strength of the diminishing marginal utility

of consumption. It is also interpreted as an indicator of

our aversion in inter-temporal inequality in income

(Dasgupta 2008; Gollier et al. 2008): were judged to be

2, the maximum sacrifice group A whose income is 100

times higher than group B will make to increase group Bs

income by one dollar is $10,000. While is mathematical

equivalent to the individual risk aversion in the expected

utility approach, equating for risk aversion would lead to

paradoxical results: on the one hand, a high implies

higher risk aversion resulting in higher expected value of

damages; on the other hand, a high , working through

Ramsey equation, will reduce the present value of

damages.

disentangle

Some

the

researchers

risk

aversion

have

from

attempted

to

inter-temporal

substitutability (Ackerman et al., 2013; Cai et al., 2012).

The expected rate of growth of per-capita consumption,

g, is not a choice parameter but can be treated as

exogenous or endogenous in the analysis.

Equity weighting (Intra-generational equity)

BIBLOGRAPHY

Arrow, K. J., Cropper, M., Gollier, C., Groom, B., Heal, G.

M., Newell, R. G., ... & Weitzman, M. (2013). How should

benefits and costs be discounted in an intergenerational

context? The views of an expert panel.

Spellman,FrankR. EconomicsforEnvironmentalProfessionals.N.p.:

n.p.,2015.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Case Study LeasingDocument3 pagesCase Study LeasingNicolaus Chandra100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- KOmatsu P&H-trc-series-dipperDocument2 pagesKOmatsu P&H-trc-series-dipperhidrastar123No ratings yet

- National Medical Admission Test (NMAT)Document2 pagesNational Medical Admission Test (NMAT)ChedRegionVII0% (1)

- Module in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)Document11 pagesModule in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)felixreyes100% (3)

- FRIAS vs. ALCAYDEDocument2 pagesFRIAS vs. ALCAYDEJay Em75% (4)

- Babies Reborn 2008Document209 pagesBabies Reborn 2008cucutenilit100% (2)

- DDOT Work Zone Utility TypicalsDocument21 pagesDDOT Work Zone Utility TypicalsDistrict Department of TransportationNo ratings yet

- Corporation Cases FinalsDocument584 pagesCorporation Cases FinalsRochelle Ofilas LopezNo ratings yet

- Economics in Context Goals, Issues and BehaviorDocument27 pagesEconomics in Context Goals, Issues and Behaviorcristi313No ratings yet

- Secrets of The Da Vinci CodeDocument90 pagesSecrets of The Da Vinci CodeChandrashekhar Choudhari100% (1)

- Communication Past Exam 22 - 23 Answers - Done by Lugy-2Document8 pagesCommunication Past Exam 22 - 23 Answers - Done by Lugy-2Lugy AnanNo ratings yet

- Economic Impacts of Olympic Games - 09.07.09Document11 pagesEconomic Impacts of Olympic Games - 09.07.09Cristina TalpăuNo ratings yet

- Cosh TermsDocument8 pagesCosh TermsMike Vanjoe SeraNo ratings yet

- Fareme NotesDocument11 pagesFareme Notesmoyos2011No ratings yet

- Amended Translation of Final Act (Sino AS 70) 1 31 2015Document5 pagesAmended Translation of Final Act (Sino AS 70) 1 31 2015WORLD MEDIA & COMMUNICATIONS100% (2)

- 1963 Tribute To TunkuDocument187 pages1963 Tribute To TunkuAwan KhaledNo ratings yet

- GPS 4500 v2: Satellite Time Signal ReceiverDocument4 pagesGPS 4500 v2: Satellite Time Signal ReceiverCesar Estrada Estrada MataNo ratings yet

- Aparna Infrahousing Private Limited: Project - Aparna Sarovar Zenith at Nallagandla - A, B, C, D & E BlocksDocument1 pageAparna Infrahousing Private Limited: Project - Aparna Sarovar Zenith at Nallagandla - A, B, C, D & E BlockspundirsandeepNo ratings yet

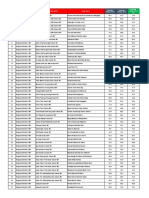

- No. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Document7 pagesNo. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Irfan JauhariNo ratings yet

- Omgeo ALERT® 56 Product Release InformationDocument16 pagesOmgeo ALERT® 56 Product Release InformationFritz BirchmayerNo ratings yet

- Read The Words and Their TranslationDocument14 pagesRead The Words and Their TranslationNataNo ratings yet

- Debate HistoryDocument4 pagesDebate Historyheri crackNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Procedure ScriptDocument4 pagesParliamentary Procedure ScriptPhoebe HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Santa Workshop - Tokens of Gratitude - 2012Document4 pagesSanta Workshop - Tokens of Gratitude - 2012Deepanjali RaoNo ratings yet

- Resume - Palak Pandey - 2002Document1 pageResume - Palak Pandey - 2002palaknarang.mNo ratings yet

- Unenforceable RecitDocument2 pagesUnenforceable RecitLoren Bea TulalianNo ratings yet

- THEO530 Book Critique 1 Heikkinen "Two Views On Women in MinistryDocument10 pagesTHEO530 Book Critique 1 Heikkinen "Two Views On Women in MinistryCrystal HeikkinenNo ratings yet

- Schineller JesuitGlossaryDocument40 pagesSchineller JesuitGlossaryKun Mindaugas Malinauskas SJNo ratings yet

- 23 Case Study Haeundae Ipark BusanDocument7 pages23 Case Study Haeundae Ipark Busancuroco pangalilaNo ratings yet

- BQ OverallDocument207 pagesBQ OverallhaniffNo ratings yet