Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parul Parihar

Parul Parihar

Uploaded by

Anonymous CwJeBCAXpOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parul Parihar

Parul Parihar

Uploaded by

Anonymous CwJeBCAXpCopyright:

Available Formats

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION: A GROTESQUE FORM OF VIOLENCE

AGAINST WOMEN

Parul Parihar

M.A, M/Phil Sociology (J.N.U, New Delhi) PhD Scholar, Department of Sociology/Social

Work, Bharatividyapeeth University, Paud Road, Pune, India.

Abstract

Female Genital Mutilation is internationally recognised as a violation of the human rights of the girls

and women, reflecting deep rooted inequality between the sexes. Since FGM is almost carried out on

minors, it is also violation of the human rights of the children. Female Circumcision according to

WHO, includes procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female gentalia or

injury to them for non- medical reasons. A recent UNICEF report study states that more than 130

million girls are at risk of being cut before their 15th birthday if the current trend continues. Most

survivors are from African Countries, but it is also practiced in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia

and some countries in Middle East. A major motivation is that the practice is believed to ensure the

girl conforms to the key social norms related to sexual restraint, feminity, respectability and maturity.

Reasons for carrying out the practice range from ethnic and tribal cultures, family relations, tribal

connections, class, economic and social circumstances and education etc.The present study explores

this practice with an overview upon the societal and extra cultural factors prevalent and facilitating

such practice with psychological grave consequences on the victims. The study is based on secondary

data findings and research and uses a compressive sociological analysis based on dialectical

perspectives.

Keywords: Genital Mutilation, Circumcision, Dialectical, Femininity, Sociological, Human Rights

Scholarly Research Journal's is licensed Based on a work at www.srjis.com

INTRODUCTION:

Brutal, criminal, regressive.Mere adjectives cannot sum up what girls aged six and seven

go through in the name of religion and tradition. Female Genital Mutilation in India is like

Vagina monologue, barely audible and rarely heard. It is high time it became a dialogue!1

Female Genital Mutilation is an age old practice which dates back to several hundreds of

years ago. According to Okeke, Anyaehie&Ezenyeaku (2012), FGM is widely recognised as

1

Thomas Mini .P; The Cut and Hurt, http://www.the week.In/the week/cover/female-genital-mutilation-in,

November 09, 2014.

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2143

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

a violation of human rights, which is deeply rooted in cultural beliefs and perceptions over

decades and generations with no easy task for change. This practice is defined by World

Health Organisation (WHO) (2010) as, all procedures that involve partial or total injury to

the female genital organs for non- medical reasons. Female genital mutilation (FGM) or

female circumcision, according to the World Health Organisation, includes procedures that

involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or injury to the female genital

organs for non-medical reasons. A recent UNICEF report states that more than 130 million

girls and women alive today have undergone FGM in 29 countries where the practice is

prevalent. As many as 30 million girls are at risk of being cut before their 15th birthday if the

current trend continues. Most survivors are from African countries, but FGM is also practised

in India, Pakistan, Indonesia, Malaysia and some countries in the Middle East.

Historical Perspectives:

Kouba&Mausher (1985) states that though the exact date of female genital circumcision and

when female genital mutilation started is not very clear, existing documents and Greek

historians and geographers, such as Herodotus (425-23 AD) show that female circumcision

happened in Ancient Egypt and the time of the Pharaohs. Consequently, Egypt is considered

as the source country of female circumcision. Female Circumcision has prevailed during the

years of 1400 B.C to 2000 B.C in Egypt (Drumma, 2010), apparently it was done in religious

ceremonies and rites (Ahmadi, 2013). According to existing evidences, the Egyptians are

considered as the pioneers of this tradition although female circumcision has also moved to

other regions of the world especially Africa. Momoh (2005) states that female circumcision

was present a long time ago and among other nations of the world including the Romans who

in order to avoid their female slaves from pregnancy, installed some rings on the two sides of

the outer lips of the uterus. The procedure, according to AID (2013 b), is carried out at a

variety of ages, ranging from shortly after birth to sometime during the first pregnancy. It

most commonly occurs between the ages of 0 to 15 years and the age is decreasing in some

countries. The practice has been linked in some countries with rites of passage for women.

FGM is usually performed by traditional practitioners using a sharp object such as knife,

razor or broken glass.

According to Wikipedia (2014), FGM is practiced in Africa, the Middle East, Indonesia &

Malaysia as well by some migrants in Europe, United States and Australia. It is also seen in

some populations of South Asia namely Afghanistan (EWIC, 2005) , Maldives

(HRW,2012); Malaysia (Rahman,Isa, Shuib, Shukri and Oshman, 1998). The highest known

prevalence rates are in 30 African countries, in band that stretches from Senegal in west

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2144

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

Africa to Ethiopia in the north to Tanzania in the South. According to AID (2013b) ,

countries with high prevalence rates (> 85 %) are for example : Somalia, Egypt and Mali.

Low prevalence rates (< 30%) are found in Senegal, Central African Republic and Nigeria).

As a result of immigration, FGM has also spread to Ethiopia, Australia and the Unites States

with some families having their daughters undergo the procedure while on vacation overseas.

As Western Governments become more aware of FGM, legislation has come into effect in

western Countries to make the practice a Criminal Offence. In 2006, Khalid Adem became

the first man in the US to be persecuted for mutilating his daughter by cutting off her Clitoris

with a scissors (Gulf News 2012). According to Ahmadi (2013), a female genital mutilation

is presently carried out in vast regions of the African Continent and Some Asian Countries of

the sub Sahara, such as the countries located in the famous region of Horu Africa (Sudan,

Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Djibouti). It is obvious that some countries of the West Africa

(Niger, Nigeria, Togo, Benin, Ghana, Mali, Senegal, Cote divoririe (Ivory Coast), Cameron,

Burkina Faso, Mauritania, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea Bissau and Equatorial Guinea

have the highest percentage of FGM around the world.2

Both women and men can be complicit in reinforcing gender norms and practices that support

violence against women. FGM also differs from most often forms of violence against women

in that, in practicing communities, it is done routinely on almost all girls, usually minors and

is promoted as a highly valued cultural practice and social norm.

There are population based data on FGM prevalence from all African Countries in which the

practice has been documented. Estimates suggest that:

1. 100-140 million girls and women are at risk of FGM each year; and

2. In the 28 countries from which national prevalence data exists (27 in Africa and Yemen),

more than 101 million girls aged 10 years and older are living with effects of FGM.

3. FGM is known to be practiced in 27 countries in Asia and the Middle East; immigrants

from these countries wherever they live, including in Australia, Canada, Europe, New

Zealand and the USA; and

4. A few population groups in Central and South America

In the 28 countries in Africa and the Middle East for which data are available, national

prevalence among women aged 15 years and older ranges from 0.6% (Uganda, 2006) to

97.9% (Somalia, 2006). There are some regional patterns in FGM prevalence. According

2

Ofor, Marian Onomerhie, Ofle, Nididi Mercy; Female Genital Mutilation: The Place of Culture and the

debilitating Effects on the Dignity of the Female Gender, European Scientific Journal, May 2015 edition, Vol. 2

No. 14 .

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2145

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

to demographic Health Surveys done during 1989-2002, within north eastern Africa

(Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia and Northern Sudan), prevalence was estimated at 80-97%,

while in eastern Africa (Kenya and the United Republic of Tanzania) it was estimated to

be 18-38 %. However, prevalence can vary strikingly between different ethnic groups

within a single country. FGM has been documented in several countries outside Africa

but national prevalence data are not available. An estimated 90% of FGM cases involve

Clitoridectomy or excision and around 10% involve infibulations, which has the most

severe negative consequences.

Types of FGM:

Type 1 Clitoridectomy : partial or total removal of the clitoris ( a small, sensitive and

erectile part of the female genitals) and ( or in very rare cases only, the prepuce, the fold

of skin surrounding the clitoris).

Type 2- Excision: partial or total removal of the Clitoris and the labia minora, with or

without excision of the labia majors (the labia are the lips that surround the vagina

Type 3- Infibulation : narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering

seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the inner, outer, labia with or

without removal of the clitoris.

Type 4- Other: all other harmful procedures to the Female Genitalia for non- medical

purposes that is, pricking, piercing, incision, scrapping and cauterizing the genital area.

FGM differs from most forms of violence against girls and women in that women are not

only the victims but also involved in perpetration. A girls female relatives are normally

responsible for arranging FGM, which, in turn, is usually performed by traditional female

excisers. FGM is also increasingly being done by male and female health care providers.

Female Genital Mutilation is internationally recognised as a violation of the human rights

of girls and women, reflecting deep rooted inequality between the sexes. Since FGM is

almost always carried out on minors, it is also a violation of the rights of children.

FGM, which has been outlawed in many countries as a serious violation of human rights,

is still prevalent among the Dawoodi Bohra Community in India. An educated and

affluent group of people, DawoodiBohras are a sub-sect of ismaili Shias. India has a

rough estimate of 5 lakh Bohras around half of the 10 lakh strong Bohra community in

the world spread across Maharashtra, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Around 90 percent of

Bohri women still undergo the archaic ritual. Survivors of FGM, also known as Khatna

among Bohris, often compare it to rape. For Johari, who belongs to the same community,

the response to the trauma has been more of outright anger. She says the intention has

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2146

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

been to moderate pleasure. That is what the Bohris have been told for years, she says.

Cutting is done with the objective of subduing a girls sexual urges. Basically, the belief

is that if you get your daughters circumcision done, she will not have premarital or extra

marital affairs. In India, Khatna used to be carried out by traditional practitioners with no

medical training. Khatna is generally done at the age of six or seven the age when a girl

is old enough to remember what she went through and young enough not to question it,

says PriyaGoswami, Director of A Pinch of Skin, a documentary on genital cutting that

won special mention at the 60th National Film Awards. She remarked that FGM was

practised by Bohras settled abroad, too. There are a lot of expatriate Bohras, settled in

developed countries, who get their daughters to fly back to India to undergo genital

cutting, She further remarked. On further investigations undertaken by The week, it

was found that genital cutting is also done in premier multispecialty hospitals in metro

cities. A woman married to a Bohri is expected to undergo circumcision in order to be

considered a Bohri. There wont be blood loss or pain. Only a pinch of the clitoris is

removed, that too, under anaesthesia. The person has to be in the hospital for 4-6 hours

only, says the gynaecologist from one of the multispecialty Bohra hospitals in Mumbai.

The procedure costs Rs 15,000. Cutting is usually done on Tuesdays, Thursdays and

Fridays.Khatna can be performed only after a sanction from the religious head.

Unlike male circumcision, Khatna is a hush-hush affair. Bohris dont talk about it. Some

of the men in the community dont even know that this practice exists. But there is a

consensus among them on whether to continue the practice. Older women do not question

the practice; for them, it lies in the zone of unquestioning belief. Some are for the practice

and ensure that even their maids daughter get it done; others dont believe in the practice

but lack courage to speak against it. There are mothers who havent got it done on their

daughters, but lie about it for the fear of being ostracised. Those who choose not to

comply with the patriarchal directives have strong reasons to do so. Genital cutting can

have several health implications. Complications can be immediate such as shock,

bleeding and infection. Sometimes it can also lead to death. It can also cause sexual

dysfunction, infertility, urinary problems, vaginal tears during coitus and delivery. At

times, bleeding can be profuse, leading to morbidity and mortality. FGM victims often

complain that they dont feel attracted to men the way their peers do. Some of the women

are worried about how much effect Khatna will have on their sexual life since it is easier

to reach orgasm if she had not undergone khatna. Clitoris stimulation is what makes a

woman sexually excited. Khatna limits ones sexual pleasures. Dr. Prakash Kothari,

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2147

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

sexologist and founder advisor to the World Association for Sexology, partly agrees with

other protagonists of the awareness campaigns against Khatna and believes that in

females, clitoris is the most reliable orgasm trigger. Most of the women require sexual

stimulation of the clitoris to have orgasm. Examining cases from Africa the doctor

further laments that it leads to psychological trauma of the victims but the desire level and

orgasmic capacity were not hampered at all. The arousal sensations were very much

there. Female sexuality is dependent on the hormones produced by the ovaries, which are

deep inside. Whatever on gets done externally will not have an impact on your desire

level. The Bohra community is witnessing currently, a silent movement.

Mama Efua(Efua Dorkenoo), the mother of the global campaign against female genital

mutilation eventually died of cancer on October 18, fighting for three decades against

FGM. Originally from Ghana, Dorkenoo came to England in the 1960s, where she

started working as a nurse. It was here that she met a woman in labour, who had

undergone infibulations. And there began a long battle against this gruesome practice. In

1983, Dorkenoo founded the Foundation for Womens Health Research and

Development. She has also worked with the World Health Organisation and was

associated with several other organisations. Her work was instrumental in the passing of

the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act, 1985, in Britain.. Of course, prevention

must be central, but prosecution is the flip side of the same coin. Because in many cases if

a parent or guardian feels they can get away with it, they will. In 1994, Dorkenoo

received the Order of the British Empire and came out with a book, Cutting the Rose:

Female Genital Mutilation: The Practice and its Prevention. 3

Consequences of FGM:

Health Consequences: FGM has no health benefits. It involves removing and damaging

healthy and normal female genital tissue and interferes with the natural functions of girls

and womens bodies. Traditional excisers use a variety of tools to perform FGM,

including razor blades and knives and do not usually use anaesthetic. An estimated 18%

of all FGM is done by health care providers who use surgical scissors and anaesthetic. All

forms of FGM can cause immediate bleeding and pain and are associated with risk of

infection with the extent of the cutting.

Ibid, The Cut and the Hurt, The Week

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2148

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

Table:1 Immediate & Long Term Health Consequences of Female Genital

Mutilation

Immediate Health Risks

Longer Term Health Risks

Severe Pain

Shock

Haemorrhage (excessive bleeding)

Sepsis

Infections

Unintended Labia Fusion

Death

Psychological consequences

Difficulty in passing urine

Known Obstetric Complications

Caesarean section

Postpatrum Haemorrhage

Extended Maternal hospital stay

Still birth or early neo natal death

Infant resuscitation

Need for Surgery

Urinary and Menstrual problem

Painful sexual intercourse & poor

quality of sexual life

Infertility

Chronic pain

Infections (Cysts, abscesses and

genital

ulcers,

chronic

pelvic

infections, urinary tract infections

Keloids that is excessive scar tissues

& Increased risk of Cervical cancer

Reproductive tract infections

Psychological consequences like fear

of sexual intercourse, post traumatic

stress disorder, anxiety, depression

Conditions Often Considered to be

associated with FGM

HIV (in the short term)

Obsteric fistula

Incontinence

Research into health effects of FGM has progressed in recent years. A WHO led study of

more than 28000 pregnant women in 6 African countries found that those who had

undergone FGM had a significantly higher risk of child birth complications such as

caesarean section and post partum haemorrhage, than those without FGM. In addition the

death rate for babies during and immediately after birth was higher for mothers with FGM

than those without. 4 They are 1.5 times more likely to experience pain during sexual

intercourse, have significantly less sexual satisfaction and are twice as likely to report a

lack of sexual desire.

Social Consequences:

Amongst the factors that encourage families to circumcise their daughters is the familys

concern about the girls inability to marry if she is not circumscribed. La Barbera, (2010)

states that an important part of this goes back to the recognition of women who are not

circumscribed as indecent which has resulted in the fact that African women do strongly

support the action of FGM in spite of the pain and agony and consider it so vital for their

daughters future especially for their marriage. Some indigenous Africans believethat

circumcised girls might control their sexual desires accordingly after maturity and it

4

Ahmadi, Amir B.A (2013), An analytical Approach to Female Genital Mutilation in West Africa, International

Journal of Womens Research, Vol. 3, No.1.Spring 2013, pp- 37-56.

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2149

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

protects them from sins and faults, while a great number of Africans also believe that

women, who have not gone through circumcision in their childhood, face multiple

physical problems at birth(La Barbera 2010). It is further believed that uncircumcised

women have lower fertility power compared to circumcised women and are not able to

control their sexual desires (Ahmadi 2013). On the other hand, in the majority of West

African countries, female circumcision represents their purity and innocence (Erlich,

1986). Virginity in a lot of African countries is valued as a pre requisite fro marriage and

equated to female honour. FGM infibulations in particular, is defended in this context as

it is assumed to reduce a womans sexual desire and lessen temptation to have extra

marital sex therapy preserving a girls virginity (AID, 2013 e). Apart from this amongst

the gender based factors, FGM is often deemed necessarily in order for a girl to be

considered a s complete woman, and the practice marks the divergence of the sexes in

terms of their roles in life and marriage. The removal of clitoris and labia viewed by

some as the male parts of a womans body is thought to enhance the girls femininity,

often synonymous with docility and obedience (AID, 2013 e).

High Risk Factors for FGM:

The most common risk factor for either undergoing FGM or focussing a girl to undergo

the procedure are cultural, religious and social; these influences include:

1) Social pressure to conform with peers

2) The perception of FGM as necessary to raise a girl properly and prepare her for adulthood

and marriage

3) The assumption that FGM reduces womens sexual desire, and thereby preserves pre

marital virginity and prevents promiscuity

4) The association of FGM with ideas of cleanliness (Hygienic, aesthetic and moral);

including the belief that, left uncut, the clitoris would grow excessively

5) Womens belief, in some rare cases, that FGM improves male sexual pleasure and virility

and in even rarer cases, that FGM facilitates childbirth by improving a womens ability to

tolerate the pain of childbirth through the pain of FGM

6) The belief that FGM is supported or mandated by religion or that it facilitates living up to

religious expectations of sexual constraint.

7) The notion that FGM is an important cultural tradition that should not be questioned or

stopped especially not by people from outside the community.

8) Young age is a key risk factor for undergoing FGM, with most procedures carried out on

girls aged between infancy and 15 years.

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2150

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

9) Research also suggests that if a mother has more education, her daughter is less likely to

undergo FGM. Notably, this protective effect of education has also been seen in other

forms of violence against women. Research in Kenya has shown that secondary education

is associated with a four fold increase in disapproval of FGM.

FGM as a Human Rights Violation:

According to Wikipedia (2014), Sudan was the first country to outlaw FGM in 1946, under

the British, although there is currently no law forbidding it. The Togolese government in

1998 voted unanimously to outlaw the practice of FGM (US Deptt; 2001). Penalties ranging

from a prison term of two months to ten years and a fine of 100,000 francs to one million

francs (approx. US $ 160 to 1,600) are approved by the law. A person who had knowledge

that the procedure was going to take place and failed to inform public authorities can be

punished with one month to one year imprisonment or a fine of from 20,000 to 50,000 francs

(approx. US $ 32 to 800). In July 2003, at its second Summit, The African Union adopted the

Maputo Protocol promoting womens rights and calling for an end to FGM. The agreement

came into force in November 2005, and by December 2008; 25 member countries had

benefitted it (US Deptt, 2001). Togo ratified the Maputo Protocol in 2005 (Wikipedia 2014);

and as of 2013, 18 African Countries have outlawed FGM/Cutting practice, including Benin,

Burkina, Faso, Central African Republican, Chad, Cote dIvoire, Djibouti, Egypt, Ghana,

Guinea, Kenya, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo and Uganda

(Lazuta, 2013;FRS,2013).

Legal Repercussions: The Global view

Legal sanctions against FGM are the most common type of intervention at the national and

international levels, but there is strong evidence that laws alone are not enough. Nevertheless,

legislation creates an enabling environment for intervention at the local level, as illustrated in

Ghana and Senegal. A study in the European Union found that effective implementation of

laws related to FGM is associated with better knowledge including how to deal with an at risk

girl, and attitudes among health care providers who are in contact with these populations.

In Uganda, anyone convicted of carrying out FGM is subject to 10 years in prison. If the life

of the patient is lost during the operation, a life sentence is recommended (BBC News, 2009).

Uganda signed the Maputo Protocol in 2003 but has not ratified it (UG Pulse 2008). In early

July 2009, President Yomen Museveni stated that a law would be passed prohibiting the

practice, with alternative livelihoods found for its practitioners (The New Vision, 2007).

In Nigeria, of the six largest ethnic groups, the Yoruba, Hausa, Fulani, Ibo, Ijaw and Kanimi,

only the Fulani do not practice any form of female genital mutilation (Online News 2005).

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2151

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

Reasons for the increase have been attributed amongst others to the definition of FGM used,

which included Type 4 FGMs. In small parts of Nigeria, the vagina walls are cut in new born

girls or other traditional practitioners performed, such as the angora and gishiri cuts- which

fall under Type 4 FGM Classification of the World Health Organisation (FGECD, 2011).

Presenting Federal Law blaming the practice of FGM in Nigeria, although Nigeria ratified the

Maputo Protocol in 2005. Perpetrators of these dastardly acts usually dare any law

enforcement agent to arrest them as they go about carrying out their business. These laws

are being mocked by excisers who conduct FGMs, and they dare any law enforcement agent

to arrest them (UN, 2009). On Jan 26th ,2015 BBC News reported the jailing of an Egyptian

medical Doctor charged with manslaughter performing female genital mutilation operation on

teenage girls.

Few interventions aimed at preventing FGM have undergone high quality and systematic

evaluation; thus much more rigorous research is needed. A systematic review of Berg and

Denison (2012) found that there was little evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to

prevent FGM. The review highlights that the factors related to the continuation or

discontinuation of the practice were tradition, religion and concern with reducing womens

sexual desire. Conversely, health complications and lack of sexual satisfaction did not favour

support of the practice.Researchers and practitioners recommend that preventive

interventions include elements of community dialogue ; understanding of the importance of

local rewards and punishments and a method for coordinating change among social groups

that includes men and women from multiple generations within the community and related

communities.Research underscores the importance of working with communities, long term

investment and a focus on human rights as understood in the local context, to support

collective change. A systematic review of interventions to prevent FGM, however, concluded

that rights based messages showed variable results. A strong message from reviews and

studies is that multicomponent interventions that combine an array of approaches are more

effective than those focussed on single targets. Single issue campaigns, that is policies aimed

only at persuading excisers or health care providers to change their practices, have not been

successful in eliminating FGM. Similarly, single target campaigns focussed on health

messages have not resulted in widespread abandonment of FGM. The components of a

comprehensive, rights based strategy might include approaches focussed on reducing gender

discrimination, improving social justice and supporting human rights, community

development and empowerment and literacy among women and girls.

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2152

SRJIS/BIMONTHLY/ PARUL PARIHAR (2143-2153)

Conclusive Remarks:

The eventual, total eradication of FGM in the countries that practice it especially in the West

African Sub region and Sub Sahara Africa as a whole is still much of a mirage. The

enactment of appropriate laws and enforcement of sanctions may go a long way in helping to

reduce the prevalence of this menace, but it will not completely eradicate it. Creation of

awareness as to the obvious dangers of emanating from the practice will, in the long run, help

in curbing the excesses of parents and traditionalists who obviously do

not want to do away with this barbaric custom which, from all evidence does no good but

harm to the physical and psychological dignity of the female gender.

MAY-JUNE 2016, VOL-3/24

www.srjis.com

Page 2153

You might also like

- The Invisible Cure: Why We Are Losing the Fight Against AIDS in AfricaFrom EverandThe Invisible Cure: Why We Are Losing the Fight Against AIDS in AfricaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (29)

- House Rental Agreement FormatDocument4 pagesHouse Rental Agreement FormatArul Thangam Kirupagaran54% (37)

- Greg Boyd - Divine AikidoDocument56 pagesGreg Boyd - Divine AikidoAlisa WilliamsNo ratings yet

- NYC Public Advocate Corrections Committee DOCCS Testimony 12.2.15Document5 pagesNYC Public Advocate Corrections Committee DOCCS Testimony 12.2.15Rachel SilbersteinNo ratings yet

- Dampak COVID-19 Terhadap Peningkatan Jumlah Sunat Perempuan Di Afrika: Studi Di Tanzania Dan NigeriaDocument13 pagesDampak COVID-19 Terhadap Peningkatan Jumlah Sunat Perempuan Di Afrika: Studi Di Tanzania Dan Nigerianathasya nurulhayatiantyNo ratings yet

- Female Genital MutilationDocument10 pagesFemale Genital MutilationPauline Mæ AntoloNo ratings yet

- HIV/AIDS in Yoruba Perspectives: A Conceptual Discourse: Aderemi Suleiman AjalaDocument7 pagesHIV/AIDS in Yoruba Perspectives: A Conceptual Discourse: Aderemi Suleiman AjalafadligmailNo ratings yet

- Female Genital MutilationDocument20 pagesFemale Genital MutilationMinmaterNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Cutting:: Harmful and Un-IslamicDocument9 pagesFemale Genital Cutting:: Harmful and Un-IslamicEdogawa RakhmanNo ratings yet

- Female Genital MutilationDocument7 pagesFemale Genital MutilationAkinmade AyobamiNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) and Its Psycho-Social Implications On The Girl-Child in The Northern Senatorial District of Cross River State, NigeriaDocument11 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation (FGM) and Its Psycho-Social Implications On The Girl-Child in The Northern Senatorial District of Cross River State, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) : The Unspoken Truth: April 2018Document5 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation (FGM) : The Unspoken Truth: April 2018Anushka VakilNo ratings yet

- FGM Wac ProjectDocument30 pagesFGM Wac Projectshekhar singhNo ratings yet

- Anderson 2018Document34 pagesAnderson 2018Fausto BonavíaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER ONE - Doc..bakDocument27 pagesCHAPTER ONE - Doc..bakUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Gender and Hiv in South Africa 1St Ed Edition Courtenay Sprague Full ChapterDocument67 pagesGender and Hiv in South Africa 1St Ed Edition Courtenay Sprague Full Chapterbruce.glinski869100% (9)

- Textbook Gender and Hiv in South Africa Courtenay Sprague Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook Gender and Hiv in South Africa Courtenay Sprague Ebook All Chapter PDFbrittani.ibarra321100% (12)

- Consti Interpretation AssignmentDocument3 pagesConsti Interpretation Assignmentakhil karunanithiNo ratings yet

- High-Risk Behaviors and The Prevalence of Sexually TransmittedDocument11 pagesHigh-Risk Behaviors and The Prevalence of Sexually TransmittedJOSE LUCERONo ratings yet

- Strength, Beauty, Courage and Power! From The CEO's Desk Strength, Beauty, Courage and Power!Document6 pagesStrength, Beauty, Courage and Power! From The CEO's Desk Strength, Beauty, Courage and Power!deltawomenNo ratings yet

- Female Circumcision - Rite of Passage or Violation of RightsDocument5 pagesFemale Circumcision - Rite of Passage or Violation of RightsNaman ShahNo ratings yet

- Advances in Probability Stochastic ProceDocument12 pagesAdvances in Probability Stochastic Procecesar meloNo ratings yet

- Research Work For PHDDocument6 pagesResearch Work For PHDShalini SonkarNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Ending Female Genital Mutilation: in The State of EritreaDocument12 pagesCase Study On Ending Female Genital Mutilation: in The State of EritreaSamridhi PrakashNo ratings yet

- Female Genital MutilationDocument11 pagesFemale Genital MutilationRomanka Milagros BojdováNo ratings yet

- African Sleeping Disease Annette Slack: Africa 1Document5 pagesAfrican Sleeping Disease Annette Slack: Africa 1nolbert_jr_No ratings yet

- Essay On SomaliaDocument8 pagesEssay On SomaliaHAKEEM FINN ADJEINo ratings yet

- The African Muslim Perspective On Human Rights Final ENGDocument23 pagesThe African Muslim Perspective On Human Rights Final ENGsakhnaNo ratings yet

- Factors Responsible For Abortions Practices AmongDocument6 pagesFactors Responsible For Abortions Practices AmongKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument21 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Asked QuestionsfdskndNo ratings yet

- Durojaye The-Human-Rights 2016Document20 pagesDurojaye The-Human-Rights 2016k9863321No ratings yet

- Child-Witch Phenomenon and Its Social Implications in NigeriaDocument12 pagesChild-Witch Phenomenon and Its Social Implications in NigeriaCarolina Costa100% (1)

- Ruby Seminar PaperDocument11 pagesRuby Seminar PaperashiqueNo ratings yet

- Harmful Traditional PracticeDocument32 pagesHarmful Traditional PracticeSam AdeNo ratings yet

- HIV AIDS Gender Inequality and Cultural Perceptions and Behaviour of SexualityDocument171 pagesHIV AIDS Gender Inequality and Cultural Perceptions and Behaviour of SexualityYousuf AliNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument47 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation (FGM) Frequently Asked QuestionsfdskndNo ratings yet

- TheissueoffemalecondomDocument31 pagesTheissueoffemalecondomSaurabh SharmaNo ratings yet

- MEINI, Bruno. HIV-AIDS, CRIME AND SECURITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICADocument50 pagesMEINI, Bruno. HIV-AIDS, CRIME AND SECURITY IN SOUTHERN AFRICAVinícius RomãoNo ratings yet

- Techniques in Answering Bar Questions by Atty Rey Tatad JRDocument2 pagesTechniques in Answering Bar Questions by Atty Rey Tatad JRAubrey Marie VillamorNo ratings yet

- Final DraftDocument13 pagesFinal Draftapi-455378107No ratings yet

- Ajphes - Article 02Document11 pagesAjphes - Article 02Katy NelNo ratings yet

- 51137-Article Text-75707-1-10-20100215Document15 pages51137-Article Text-75707-1-10-20100215Some LaNo ratings yet

- AIDS in AfricaDocument6 pagesAIDS in AfricaJoel AmezcuaNo ratings yet

- Same-Sex Sexuality in AfricaDocument10 pagesSame-Sex Sexuality in AfricaFabioGaspariniNo ratings yet

- Female CircumcisionDocument6 pagesFemale Circumcisionapi-306804181No ratings yet

- Female Genitile Mutilation RPDocument8 pagesFemale Genitile Mutilation RPPalak GroverNo ratings yet

- (PDF) Nurses' Role in The Eradication of Female Genital CuttingDocument16 pages(PDF) Nurses' Role in The Eradication of Female Genital CuttingChristiana OnyinyeNo ratings yet

- Mother-To-Child Transmission (MTCT) of Hiv/AidsDocument23 pagesMother-To-Child Transmission (MTCT) of Hiv/AidsParamita ArdiyantiNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation: All Saints University School of Medicine Kehinde O. AkinmadeDocument9 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation: All Saints University School of Medicine Kehinde O. AkinmadeAkinmade AyobamiNo ratings yet

- Knowledge of Hiv Transmission and Sexual Behavior Among Zimbabwean Adolescent Females in Atlanta, Georgia: The Role of Culture and Dual SocializationFrom EverandKnowledge of Hiv Transmission and Sexual Behavior Among Zimbabwean Adolescent Females in Atlanta, Georgia: The Role of Culture and Dual SocializationNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Practice of Female Circumcision Among Women of Reproductive Ages in South West NigeriaDocument8 pagesKnowledge and Practice of Female Circumcision Among Women of Reproductive Ages in South West NigeriaRicardo Ivan Macias FuscoNo ratings yet

- FGM and It's ImpactDocument2 pagesFGM and It's Impactamy7dasNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation (Kehinde Akinmade)Document11 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation (Kehinde Akinmade)Akinmade AyobamiNo ratings yet

- Strategies For The Empowerment of WomenDocument38 pagesStrategies For The Empowerment of WomenADBGADNo ratings yet

- The Most Dangerous Places and Travel Destinations in The WorldDocument5 pagesThe Most Dangerous Places and Travel Destinations in The WorldAhmedNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation Among Iraqi Kurdish Women: A Cross-Sectional Study From Erbil CityDocument9 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation Among Iraqi Kurdish Women: A Cross-Sectional Study From Erbil CityAdis DuderijaNo ratings yet

- HIV AIDS HandoutDocument11 pagesHIV AIDS HandoutMarius BuysNo ratings yet

- Female FoeticideDocument6 pagesFemale FoeticidePranav Khanna67% (3)

- Reading Comprehension Read The Text Below and Answer The Questions That FollowDocument5 pagesReading Comprehension Read The Text Below and Answer The Questions That FollowBlankPageNo ratings yet

- Female Genital Mutilation in Egypt, Sudan and India: Maya El Azhary 900139136Document18 pagesFemale Genital Mutilation in Egypt, Sudan and India: Maya El Azhary 900139136Maya El AzharyNo ratings yet

- Final Project in Educ. 14 (Social Dimension of Education) : Gender InequalityDocument7 pagesFinal Project in Educ. 14 (Social Dimension of Education) : Gender InequalityDela Puerta RutchieNo ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive HealthcareDocument6 pagesSexual & Reproductive Healthcareardian jayakusumaNo ratings yet

- Proquest Jurnal 7Document19 pagesProquest Jurnal 7Winda PNo ratings yet

- 4.Dr Gagandeep KaurDocument13 pages4.Dr Gagandeep KaurAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 25.suresh ChenuDocument9 pages25.suresh ChenuAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 19.Dr Ibrahim Aliyu ShehuDocument29 pages19.Dr Ibrahim Aliyu ShehuAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Homesh RaniDocument7 pagesHomesh RaniAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 1.prof. Ajay Kumar AttriDocument8 pages1.prof. Ajay Kumar AttriAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 29.yuvraj SutarDocument4 pages29.yuvraj SutarAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Rights and Duties of Parents Towards Their Children Under Islamic Law in NigeriaDocument29 pagesAn Analysis of The Rights and Duties of Parents Towards Their Children Under Islamic Law in NigeriaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- 13.nasir RasheedDocument9 pages13.nasir RasheedAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- "The Effective Learning of English Grammar ' Tenses' Through Multi Media Package For The Students of Standard IxDocument10 pages"The Effective Learning of English Grammar ' Tenses' Through Multi Media Package For The Students of Standard IxAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Investigation of The Satus of The Social Development Programs Under Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana in Rajgoli Village in Kolhapur DistrictDocument12 pagesInvestigation of The Satus of The Social Development Programs Under Sansad Adarsh Gram Yojana in Rajgoli Village in Kolhapur DistrictAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Sociological Gaze of Tare Zameen ParDocument4 pagesSociological Gaze of Tare Zameen ParAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Financial Concerns and Requirements of Women EntrepreneursDocument10 pagesFinancial Concerns and Requirements of Women EntrepreneursAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Student Engagement and Goal Orientation, Resilience: A Study On Senior Secondary School StudentsDocument6 pagesStudent Engagement and Goal Orientation, Resilience: A Study On Senior Secondary School StudentsAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Empowerment and Education of Tribal Women in IndiaDocument12 pagesEmpowerment and Education of Tribal Women in IndiaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- A Study of Effect of Age and Gender On Stress of AdolescentsDocument5 pagesA Study of Effect of Age and Gender On Stress of AdolescentsAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Customers' Consciousness About Financial Cyber Frauds in Electronic Banking: An Indian Perspective With Special Reference To Mumbai CityDocument13 pagesCustomers' Consciousness About Financial Cyber Frauds in Electronic Banking: An Indian Perspective With Special Reference To Mumbai CityAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Depression Among Higher Education Students of KolkataDocument12 pagesCritical Analysis of Depression Among Higher Education Students of KolkataAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Technostress, Computer Self-Efficacy and Perceived Organizational Support Among Secondary School Teachers: Difference in Type of School, Gender and AgeDocument13 pagesTechnostress, Computer Self-Efficacy and Perceived Organizational Support Among Secondary School Teachers: Difference in Type of School, Gender and AgeAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- A Study On Pre-Investment Due Diligence by Capital Market Investors of Mumbai Suburban AreaDocument11 pagesA Study On Pre-Investment Due Diligence by Capital Market Investors of Mumbai Suburban AreaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Exploitation of The Ones Who Have No OneDocument15 pagesExploitation of The Ones Who Have No OneAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- A Study of Awareness About Online Information Resources of Student TeachersDocument7 pagesA Study of Awareness About Online Information Resources of Student TeachersAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Women - Right To Survive: Issues of Female Infanticide and FoeticideDocument11 pagesWomen - Right To Survive: Issues of Female Infanticide and FoeticideAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Context of Eco-Psychological ImbalanceDocument8 pagesContext of Eco-Psychological ImbalanceAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- The Need of Remote Voting Machine in Indian Voting SystemDocument7 pagesThe Need of Remote Voting Machine in Indian Voting SystemAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Aggression Among Senior Secondary School Students in Relation To Their Residential BackgroundDocument8 pagesAggression Among Senior Secondary School Students in Relation To Their Residential BackgroundAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Effect of Life Skill Training On Mental Health Among B.ed. Interns in Relation To Their Impulsive BehaviourDocument9 pagesEffect of Life Skill Training On Mental Health Among B.ed. Interns in Relation To Their Impulsive BehaviourAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Techno-Pedagogical Competency of Higher Secondary School Teachers in Relation To Their Work Motivation in Chengalpattu DistrictDocument5 pagesTechno-Pedagogical Competency of Higher Secondary School Teachers in Relation To Their Work Motivation in Chengalpattu DistrictAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Historical Development of Play Schools in IndiaDocument11 pagesHistorical Development of Play Schools in IndiaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- A Lookout at Traditional Games Played by Tribes in IndiaDocument4 pagesA Lookout at Traditional Games Played by Tribes in IndiaAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Mindfulness Exercise To Change The Body and MindDocument8 pagesThe Impact of Mindfulness Exercise To Change The Body and MindAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Henry C K LiuDocument158 pagesHenry C K Liuantix8wnNo ratings yet

- Labor Relations and Negotiations: Atty. Aimee Grace A. Garcia, CpaDocument8 pagesLabor Relations and Negotiations: Atty. Aimee Grace A. Garcia, CpaAA GNo ratings yet

- The 'Ndrangheta and Sacra Corona Unita - The History, Organization and Operations of Two Unknown Mafia Groups (PDFDrive)Document190 pagesThe 'Ndrangheta and Sacra Corona Unita - The History, Organization and Operations of Two Unknown Mafia Groups (PDFDrive)MohammadNo ratings yet

- National Power Corporation vs. Municipal Government of NavotasDocument11 pagesNational Power Corporation vs. Municipal Government of NavotasEvelyn TocgongnaNo ratings yet

- MulanDocument2 pagesMulanRodney ChenNo ratings yet

- History of Modern Maharashtra - University of Mumbai TextbookDocument235 pagesHistory of Modern Maharashtra - University of Mumbai TextbookRajesh JadhavNo ratings yet

- CR PCDocument15 pagesCR PCRiyaNo ratings yet

- GR 166470Document10 pagesGR 166470Dong OnyongNo ratings yet

- 01-Greater Balanga Development v. Mun. BalangaDocument6 pages01-Greater Balanga Development v. Mun. BalangaryanmeinNo ratings yet

- Chi Psi Former Affiliates LetterDocument2 pagesChi Psi Former Affiliates LetterthedailynuNo ratings yet

- TMO Preparation 3Document10 pagesTMO Preparation 3Abdul Saboor Khattak100% (3)

- Sibling RivalryDocument16 pagesSibling RivalrybadiiuzzamanNo ratings yet

- Mrcardmnt02 2 Alasanas Al 001Document5 pagesMrcardmnt02 2 Alasanas Al 001mahmoud blalNo ratings yet

- Atin ItoDocument2 pagesAtin ItoArielNo ratings yet

- IndictmentDocument4 pagesIndictmentHayden SparksNo ratings yet

- Romeo JulietDocument3 pagesRomeo JulietNotes4youNo ratings yet

- LORENZO vs. POSADAS JR.Document6 pagesLORENZO vs. POSADAS JR.Roswin MatigaNo ratings yet

- Naastik Brahmcharya - Google SearchDocument1 pageNaastik Brahmcharya - Google SearchpuniadeshhindNo ratings yet

- Free Editable Special Power of Attorney TemplateDocument2 pagesFree Editable Special Power of Attorney TemplateHiroshi DizonNo ratings yet

- People V Rodriguez July 2019Document8 pagesPeople V Rodriguez July 2019Anonymous dtceNuyIFINo ratings yet

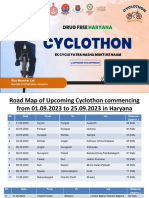

- Cyclothon RouteDocument29 pagesCyclothon RouteSurya ThakurNo ratings yet

- Kingdoms Live Cheat Sheet v2.5Document20 pagesKingdoms Live Cheat Sheet v2.5Jeje Cuba DuluNo ratings yet

- 11e AR ConfirmationsDocument12 pages11e AR ConfirmationsJL Huang0% (1)

- Introduction To International Trade Law Note 3 of 13 Notes: Dispute SettlementDocument40 pagesIntroduction To International Trade Law Note 3 of 13 Notes: Dispute SettlementMusbri MohamedNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 114286 - Consolidated Bank & Amp Trust Corp. v. Court ofDocument8 pagesG.R. No. 114286 - Consolidated Bank & Amp Trust Corp. v. Court ofAj SobrevegaNo ratings yet

- Torcuator vs. BernabeDocument15 pagesTorcuator vs. BernabeBelle ConcepcionNo ratings yet

- A Sumry Recurit Course 9 and 3 Month Eaglet 3 Term Ok Ok 22 Dec by DIGP Direct Recurit Police Constable CourseDocument10 pagesA Sumry Recurit Course 9 and 3 Month Eaglet 3 Term Ok Ok 22 Dec by DIGP Direct Recurit Police Constable CourseMuhammad HaneefNo ratings yet