Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cool

Cool

Uploaded by

Priyanka DargadCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cool

Cool

Uploaded by

Priyanka DargadCopyright:

Available Formats

Portfolios of Political

Ties and Business

Group Strategy in

Emerging Economies:

Evidence from Taiwan

Administrative Science Quarterly

59 (4)599638

The Author(s) 2014

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.com/

journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0001839214545277

asq.sagepub.com

Hongjin Zhu1 and Chi-Nien Chung2

Abstract

Using data on 290 business groups, this study examines how ties with rival

political parties maintained by Taiwanese firms from 1998 through 2006

affected business strategies, specifically the unrelated diversification into new

industries. Taiwans recent democratization and emerging economy provide an

ideal setting for studying the economic impact of firms ties with rival political

parties. By focusing on a firms entire portfolio of ties instead of strictly dyadic

businessgovernment ties, we offer a novel model that demonstrates how the

interplay of various ties affects a firms strategy differently under different

forms of government. Our analysis shows that under a united government, ties

to the ruling party facilitate entries of business groups into unrelated industries,

while ties to the opposition parties inhibit such moves. Portfolios of ties to both

the ruling and opposition parties impose additional obstacles to market entry.

Under a divided government, however, ties to the ruling party are conducive to

market entry, and portfolios of ties to both the ruling party and the opposition

party with legislative authority offer a further boost. Regardless of type of government, the effect of having a portfolio of political ties tends to be mitigated

by a firms internal resources and capabilities: a firm with sufficient resources

and market entry experience has a better chance of achieving its goals even

when a dominant political party withholds its support. Our study highlights the

tradeoffs that politically connected firms confront in emerging economies with

underdeveloped political and market institutions.

Keywords: political ties, portfolios of political ties, political parties, market

entry, democratic emerging economies

Previous research has demonstrated that political ties influence firms market

value and performance (Peng and Luo, 2000; Fisman, 2001; Johnson and

Mitton, 2003). Relatively less attention has been paid to whether and how

1

2

DeGroote School of Business, McMaster University

National University of Singapore Business School

600

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

political ties influence firms strategy. More importantly, previous studies

mainly examined businessgovernment (i.e., administrative or legislative) ties

(e.g., Fisman, 2001; Hillman, 2005), leaving another key component of political

ties, the relationships between firms and political parties, largely untouched.

Research shows that firms build ties and make campaign contributions to political parties (Cooper, Gulen, and Ovtchinnikov, 2010), but why they decide to

create ties, with which political parties, and how such choices affect firms strategic decision making remain unclear. This gap is critical, given political parties

significant role in setting policy agendas, nominating candidates, monitoring

elected representatives, and controlling government institutions when they are

in power.

Furthermore, the unit of analysis in previous studies has been dyadic ties

between firms and the political regime, which assumes that ties to

different political actors are independent of each other and that their influence on the focal firm is the aggregated effect of all ties. In democracies,

however, competition among political parties affects their dependence on

firms for resources such as campaign contributions (Bonardi, Holburn, and

Vanden Bergh, 2006), as well as their subsequent provision of administrative

favors to the firms (Baron, 1994). Firms connected to rival political parties are

thus exposed to opportunities and constraints that stem not only from individual political parties but also from competition among the parties. For

example, ties to both ruling and rival political parties may bring tertius gaudens advantages (Simmel, 1922; Burt, 1992) and political flexibility to the

firm. Focusing on individual dyadic ties would not capture such synergies or

conflicts among the ties that may make the overall effect on the focal firm

greater or smaller than the sum of the effect generated by each dyadic tie

(Vassolo, Anand, and Folta, 2004; Wassmer, 2010). Such a portfolio effect is

an aggregate property that can be captured only at the level of the collectivity

of ties.

Firms can build portfolios of political ties with various political parties, including opposing parties. An egocentric portfolio of political ties consists of the

focal firm (ego), its set of partners (alters), and their connecting ties

(Wasserman and Faust, 1994). The portfolio is hence a collection of dyadic ties

to different alters that can affect a firms strategy. A diverse portfolio of ties

with different political parties suggests that the focal firms target is multiple

political parties, whereas a focused portfolio implies more concentrated political

tactics. Dyadic ties and portfolio diversity can affect a focal firms strategy

under different forms of government: united government, in which a political

party controls both executive and legislative branches, and divided government,

in which different parties control the legislative and executive branches (Alt and

Lowry, 1994). Moreover, the focal firms internal resources and capabilities

may influence the strategic efficacy of resources acquired from portfolios of

political ties.

The portfolio effect is particularly important in dynamic and uncertain environments such as those in newly democratized emerging economies, where

competition among political parties is intense, regime change is frequent and

hard to predict, and market institutions are underdeveloped (Huntington, 1991;

Hoskisson et al., 2000). Taiwan presents such an environment and thereby

offers an ideal setting in which to investigate our research questions. As a typical case in the third wave of democratization (Huntington, 1991), Taiwan has

Zhu and Chung

601

experienced large-scale democratization since 1987 and realized the first electoral turnover from the dominant Nationalist Party, Kuomintang (KMT), to the

opposition, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), in 2000. Because of its

short democratic history, Taiwans political party institutions are more personalized, weak in policy accountability, and characterized by floating voters

and greater electoral volatility than those in established democracies such as

the United States (Mainwaring, 1999; Chu, 2006). Meanwhile, like other

emerging economies, Taiwan features underdeveloped market intermediaries, substantial information asymmetries and high transaction costs, dominant business groups, and evident state involvement in the market

(Hoskisson et al., 2000; Luo and Chung, 2005). As a result, firms tend to rely

on personal political ties to gain access to resources and information that are

otherwise difficult or costly to obtain from the market. Further, the dynamic

political environment, as demonstrated by the unanticipated regime change

in 2000, makes it imperative for political elites to seek support from firms

and drives firms to adjust their relationships with political parties in response

to regime changes. The evolution of diversity in a portfolio of ties along with

electoral results allows us to examine the strategic role of the evolution of

tie portfolios. More importantly, the democratization in Taiwan is typical of

many other emerging economies in terms of timing, causes, process, and

characteristics (Huntington, 1991), making our results potentially generalizable to more than a dozen newly democratized emerging economies, such

as Brazil, Poland, and South Korea (Chung, 2003; McMenamin and

Schoenman, 2007).

Our study also has implications for the research on portfolios of interorganizational ties (Wassmer, 2010). Lavie (2007) suggested that an alliance portfolio

with competing partners benefits the focal firm by enhancing its bargaining

power vis-a`-vis its partners. Our research on the portfolio of ties to political parties sheds light on two important and understated contingencies of such benefits. First, the third-party advantages to the focal firm depend on the relative

competitive status of partners. The benefits increase with comparable competitive status, whereas they decrease or even turn into costs with a disparate

competitive status between partners. Second, political parties have the punitive

power to direct discrimination and retaliation at focal firms (Siegel, 2007), but

business partners do not. Although large business partners may play against

small firms with their market power, their actions are not institutionally based

and are less detrimental. Clarifying the tradeoff of benefits and costs of portfolio diversity in portfolios of political ties helps build a more comprehensive theory of network portfolios.

RIVAL POLITICAL PARTIES, PORTFOLIOS OF POLITICAL TIES,

AND FIRM STRATEGY

The conventional research on dyadic political ties analyzes ties as if they were

independent. A firms portfolio of political ties, however, is composed of ties to

different political parties, and the relative competitive status of the parties

shapes the dynamics of ties between the firm and those parties and thus the

functioning of the ties. In general elections in democratic systems, two or more

political parties compete for the control of government institutionsexecutive

and legislative branchesand the party that wins the majority of votes gains

602

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

control of the government.1 If a political party controls both executive and legislative branches, it achieves dominant political power, and if different parties

control the legislative and executive branches, political power is relatively

evenly distributed.

In democratic systems, the effects of dyadic political ties on the focal firms

strategy are influenced by the prominence of political partiesthe resources

and privileges at their disposalas well as by the focal firms bargaining

powerits ability to acquire resources and privileges from the parties. The ruling party of a united government is a high-power and prominent partner for

firms because it allocates resources and shapes the regulatory environment

(Schuler, Rehbein, and Cramer, 2002; Holburn and Vanden Bergh, 2008). It also

confers legitimacy on focal firms that helps them manage constraints in the

external environment (Pfeffer, 1987). In contrast, opposition parties under a

united government are low-power partners because of the lack of mandatory

influence. In a divided government, however, the ruling party and the opposition party with legislative authority are comparably powerful and prominent

because the former sets and executes policies and regulations, whereas the

latter affects laws and rules via legislative power (Elgie, 2001). Ties to both parties can also confer legitimacy on a focal firm by signaling to stakeholders the

firms ability to maintain key relationships.

The competitive status of different political parties also shapes the focal

firms bargaining power: its ability to favorably change the terms of agreements, obtain accommodations from a party, and influence the outcomes of

negotiations (Yan and Gray, 1994). Unlike alliances or other business relationships between firms, ties between firms and political parties do not involve formal agreements and judicial enforcement, and hence the risks to firms of

opportunism are high (Dixit, 1996: 53). The focal firm has to leverage its bargaining power to initiate desired exchanges and ensure that politicians keep

their promises. Resource dependence theory (Pfeffer and Salancik, 1978;

Bacharach and Lawler, 1984) suggests that the bargaining power of a politically

connected firm over political parties depends on the firms stakes in the political ties, as well as the availability of alternatives. More alternatives enhance the

firms bargaining power over its political partners (Yan and Gray, 1994). The

firm is likely to enjoy stronger bargaining power under divided government than

under united government because of the availability of alternative political parties as allies. The alternative enhances the firms position in negotiations, rendering political parties more willing to satisfy its demands in exchange for

electoral support (Baron, 1994). By contrast, in a united government, alternative

1

The scope of government institutions controlled by the winning party differs among electoral systems. In parliamentary countries such as the United Kingdom and Canada, the executive branch is

typically a constituent part of the legislative branch (Moe and Caldwell, 1994). The majority party

that wins legislative elections controls both executive and legislative branches. In countries with

chief executives, or presidents, such as the United States, there is a greater separation of political

power between the executive and legislative branches (Hillman and Keim, 1995). Political control of

the legislature does not guarantee control of the executive branch because the chief executive is

elected separately and may represent another party. To the extent that political power is more concentrated in parliamentary systems (Hillman and Keim, 1995), our theoretical framework, which

focuses on the strategic interaction between firms and rival political parties, applies better to firms

operating in countries with a chief executive.

Zhu and Chung

603

political partners are not available and the firm is in a weak bargaining position,

compelling it to accept the ruling partys demands.

In addition to influencing dyadic ties, the competitive status of political parties may also influence the effects of the tie portfolio on firms by providing

tertius gaudens advantages and political flexibility that produces insurance

benefits. The competition among political parties for the firms electoral support

enables the firm to mediate among political parties and better control the

exchange of information and resources with them. The discretion in choosing

partners for pursuing particular strategic objectives and juggling among competing partners enhances the firms leverage on its partners and its access to partners resources (Burt, 1992). Further, the lack of full collaboration among

political parties creates an insularity that renders them unable to coordinate their

actions toward the firm, allowing the firm to maintain separate identities and

positions with each political party (Burt, 2000). Competing political parties are

likely to bring pronounced tertius gaudens advantages to the focal firm because

major political parties do not usually engage in collaboration in general elections.

This situation contrasts with strategic alliances in which partners engage in coopetition (Hamel, Doz, and Prahalad, 1989), which may compromise the focal

firms tertius gaudens advantages (Bae and Gargiulo, 2004; Lavie, 2007).

Furthermore, a diverse portfolio of political ties under a divided government

can benefit the focal firm by producing political flexibility, which allows firms to

sustain powerful political allies regardless of the electoral results and regime

changes. Connections to both the ruling and the opposition party reduce the

possibility of discrimination and retribution because both sides are the firms

allies, and their competitive status makes them dependent on firms electoral

support. This diversity of ties makes it possible for the firm to exchange information and resources continuously with the government regardless of regime

changes and thus facilitates its long-term strategic planning (Meyer and

Rowan, 1977; Cattani et al., 2008), such as for restructuring and entering new

markets. Such an insurance effect is akin to the concept of a diversified stock

portfolio in financial investment (Evans and Archer, 1968). Table 1 summarizes

our conceptual framework.

Dynamic electoral results make the value of a diverse portfolio contingent on

the status change of political parties, with the possibility that an initially valuable

Table 1. Conceptual Framework: Portfolios of Political Ties with Political Parties under United

and Divided Governments

United Government (limited party competition)

Divided Government (intense party competition)

Ruling party competitive status

Most powerful: administrative and legislative authority

Strong bargaining power over firms

Ability to implement discrimination and retribution toward

firms with diverse portfolios of political ties

Moderately powerful: administrative authority

Medium bargaining power over firms

May provide tertius gaudens benefits and political

flexibility to firms with diverse portfolios of political ties

Opposition party competitive status

Least powerful: no political power

Weak bargaining power over firms

May trigger discrimination and retribution from ruling

party toward firms with diverse portfolios of political ties

Moderately powerful: legislative authority

Medium bargaining power over firms

May provide tertius gaudens benefits and political

flexibility to firms with diverse portfolios of political ties

604

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

portfolio could turn into a liability overnight and vice versa (Siegel, 2007). This

possibility is particularly salient in newly democratized states because their nascent political institutions make the competition of political parties more

dynamic, regime change more disruptive, and potential retaliation by dominant

political parties more plausible (Huntington, 1991; Mainwaring, 1999). In addition, the effectiveness of political parties in providing resources, information,

and administrative privilege, as well as in conferring legitimacy on focal firms, is

likely to be stronger in emerging economies because of weak market institutions and strong state involvement in the market (Peng and Luo, 2000). Under

such circumstances, being connected to the right political party (or parties) and

maintaining a facilitating portfolio are critical for firms in pursuing strategic

goals.

In addition, the literature on the resource-based view of business groups

indicates that the effects of external resources on strategic maneuvers such as

market entry may depend on groups internal resources and capabilities (Kock

and Guillen, 2001). A groups ability to enter new industries depends on its

access to production factors and its coordination skills to set up new

plants (Guillen, 2000: 365). Because portfolios of political ties shape resource

and information flows to business groups, their impacts on market entries are

likely to vary across business groups with different levels of dependence on

resources such as financial capital and capabilities such as experience in market entry. These organizational attributes may amplify or reduce the significance of resources acquired through political ties, as well as the opportunities

and risks arising from such ties.

Portfolios of Political Ties in Newly Democratized Emerging Economies

Although critical, the forming of political ties and portfolios may not be completely intentional. The composition of a portfolio is often the product of a

firms initial social embeddedness in its environment, resource needs, and strategic response to the changing environment. Firms executives may be connected to political party leaders simply because they are family members,

classmates, or neighbors or share the same political beliefs (Johnson and

Mitton, 2003; Siegel, 2007). For instance, a few firms had political ties to the

Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) before it came into power in Taiwan in

2000. The innate social embeddedness serves as a seedbed that facilitates the

growth and evolution of ties between firms and political parties. At the same

time, firms may purposefully try to build ties with political parties to meet their

resource needs and terminate ties that have adverse impacts. Not all purposeful attempts succeed, however, because executives may not be able to establish connections with political actors who are on the other side of a significant

social divide or embrace a different or even opposite political ideology. For

instance, prior to 1987, when democratization began in Taiwan, the KMT, an

authoritarian ruling party, had long refused to interact with business group leaders holding different political views (Hsu, 1991; Chung, 2006). Likewise, it is difficult, if not impossible, for firms to cut their innate connections (e.g., kinship

relationships) to certain political parties despite their adverse impacts. The fact

that firms can proactively change portfolio diversity only to a certain extent suggests that political ties can be exogenous to firms strategic actions.

Zhu and Chung

605

Moreover, interviews we conducted with executives in Taiwan in connection

with this study indicate that almost all businessmen engage in building and

maintaining good relationships with politicians, even if they are unsure about

the specific benefits they will derive from such relationships. Many of them

view political ties as social capital that should be accumulated in advance for

future use (Lin, 2001). Such behavior tends to create political ties that then

exist before the firm pursues specific strategies. In this respect, the forming of

a portfolio of political ties likely follows a path-dependent process and coevolves with business executives social capital and the focal firms dependence on resources accessible from political partners, as well as strategic

actions taken by the firm in response to the changing market and political environment (Koza and Lewin, 1998; Lavie and Singh, 2012). The intensified party

competition during democratization and subsequent regime change around

2000 in Taiwan provided a setting similar to that of a natural experiment to

investigate the evolution of portfolios of political ties and their effects on firm

strategy.

Party Competition in Taiwan, 19982004

The KMT dominated Taiwans politics and economy from 1949 until 1987

(Gold, 1985), when the greatest wave of democratization in Taiwans modern

history took place. Martial law was lifted in 1987, allowing for new political parties, labor protests, and private mass media. Until 2000, the KMT remained the

dominant power in Taiwan, controlling not only government agencies but also

the Legislative Yuan (the Taiwanese legislature) and judiciary. The establishment of a major opposition party, the DPP, in 1987 intensified competition for

political power. Facing the competition, the KMT started seeking electoral support from enterprises in the 1990s, transforming the statebusiness relationship from a top-down structure into a more-balanced strategic partnership

(Huang, 2004). Political parties provide regulatory privileges and resources to

connected firms, and in return firms make campaign contributions to political

parties to cover huge electoral expenditures such as campaign-office rental and

charges for TV advertisements.2 Firms also mobilize their employees and suppliers to vote for the party candidates to whom they are connected, which can

affect the voting behavior of swing voters.

In the 2000 presidential election, Chen Shui-Bian, of the DPP, was victorious, putting an end to more than a half century of KMT domination. Although

Chen Shui-Bian was reelected in 2004, the DPPs success in the presidential

elections did not guarantee its control of the Legislative Yuan. The KMT still

held a majority of seats in the legislature between 2000 and 2008, a power

landscape parallel to that of the Democratic and Republican parties in the

United States from 1994 to 2000. This separation of legislative and executive

power further intensified political competition. In response to the political

regime changes, firms changed their portfolios of political ties with the KMT to

diverse portfolios consisting of ties to both the DPP and the KMT. For example,

our coding shows that Taiwan Cement Groups portfolio in 1998 included 39

2

It is estimated that a campaign in Taiwan might have cost $US 24 million in the late 1990s,

whereas successful candidates in U.S. congressional races would spend only $US 600,0001 million, even though American constituencies were twice as large (Robinson, 1999).

606

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

ties with the KMT and zero ties with the DPP. In 2004, it had changed to 33

ties with the KMT and 4 ties with the DPP, reflecting the impact of regime

change on the groups political ties portfolio. The diversity of portfolios of political ties has implications for firms strategy, particularly for entry into unrelated

industries, which involves considerable resources, investments, and risks.

Although unrelated diversification is regarded as undesirable in developed

markets because the costs arising from the lack of synergies between unrelated industries outweigh the benefits of general resources and capabilities

(Teece et al., 1994), the tradeoff of unrelated diversification features a different

balance for business groups in emerging markets because of their organizational structure and the distinct market institutions (Leff, 1978; Amsden and

Hikino, 1994; Kock and Guillen, 2001). Confronting underdeveloped market

infrastructures, business groups use their broad scope to create internal markets and gain access to capital, product, talent, and technology that are otherwise unavailable or difficult to obtain (Khanna and Palepu, 2000a; Khanna and

Yafeh, 2007). The benefits of having access to these resources increase with

the extent of unrelated diversification (Chang and Hong, 2000; Khanna and

Palepu, 2000b; Khanna and Rivkin, 2001), making the benefits of unrelated

diversification outweigh the costs. Moving into new industries is thus a sensible strategy for the growth of business groups in emerging markets. Moreover,

the wave of deregulation and privatization sweeping through emerging economies in the 1980s (Sachs and Warner, 1995) provided new opportunities for

business groups and made entry into new industries an institutionalized imperative for groups to remain competitive (Aldrich and Fiol, 1994). In addition, business groups capability to enter new markets, which hinges on the

combination of requisite resources for setting up new plants and is not industry-specific, enables them to seize opportunities arising from the deregulation

of various unrelated industries.

There is some evidence that being affiliated with diversified business groups

contributes to firm profitability. Khanna and Rivkin (2001) showed that group

membership enhanced member firms return on assets in several emerging

economies, including Taiwan. This finding, which contradicts the conventional

wisdom in developed economies, such as in the United States, that unrelated

diversification is detrimental, suggests that unrelated diversification might entail

differential financial performance that varies across institutional contexts.

Political Ties and Entry into New Industries

Because the politicaleconomic contexts of emerging economies make access

to privileged resources critical for market entry (Guillen, 2000), ties to political

parties with different competitive statuses substantially enable or constrain

market entries. Such political influence on market entry is less likely to exist in

developed economies because their relatively well-developed market institutions and the limited involvement of the state in the economy confine the strategic impact of political ties. Political ties and tie portfolios shape business

groups market entry under united and divided government in emerging economies in four particular ways.

First, under a united government, political ties to the ruling party facilitate

firms entry into new industries through the provision of information, resources,

administrative privileges, and legitimacy. Information transferred through

Zhu and Chung

607

political ties keeps firms updated about industrial policies and regulations that

help firms forecast changes in the environment and identify novel market

opportunities (Schuler, Rehbein, and Cramer, 2002; Luo, 2003). Studies have

shown that information acquired through boundary-spanning relations can

shape corporate strategic choices such as mergers and acquisitions

(Haunschild, 1993). Such information frames managers views of the external

environment and constructs the set of strategic options available for selection

(Geletkanycz and Hambrick, 1997). This information is particularly valuable for

firms in emerging economies, where information asymmetry is prevalent and

changes in policies and regulations are difficult to foresee (Khanna and Palepu,

1999). Because of the ruling partys dominant role in formulating and implementing economic and industrial policies, the information obtained from political ties with the ruling party tends to be more timely, tacit, and accurate than

that acquired from other sources (Potter, 2002; Li and Zhang, 2007). Insiders of

the Legislative Yuan remarked in our interviews that Taiwans legislative body

is a center of information flows about economic policies and industry regulations. Under the KMTs rule prior to 2000, business leaders connected to the

KMT were better able than those without such ties to access the latest information and used this advantage to plan new market strategies.

Second, the ruling party is able to steer resources such as financial credits

and foreign technology to politically connected firms through a variety of state

agencies. In particular, it has power to allocate financial resources via

government-owned banks. Politicians of the ruling party often channel funds to

favored firms to maintain and increase their political power (Rajan and Zingales,

2003). Khwaja and Mian (2005) found that politically connected firms in

Pakistan borrowed 45 percent more than nonconnected counterparts from government banks. Dinc

x (2005) showed that, compared with private banks,

government-owned banks increase their lending particularly in election years to

assist the ruling party in obtaining votes and campaign contributions from businesses. Financial resources facilitate strategic maneuvers such as new market

entry, particularly for firms in emerging economies where capital market intermediaries are missing or underdeveloped.

Third, firms tied to the ruling party likely have superior access to licenses,

permits, administrative privileges, and favors that facilitate market entry.

Research shows that firms connected to the winning party in the 2000 U.S.

presidential election experienced an increase in government procurement contracts (Goldman, Rocholl, and So, 2013). Such privileges are likely to be more

salient in emerging economies because of the prevailing state involvement in

the market (Peng and Luo, 2000). A well-known case is Yulon Motor Group,

founded by Yen Ching-Ling, whose original business was textiles. Backed by

his wifes friendship with Madame Chiang Kai-shek, in 1953 Yen established

the first automobile manufacturing company of Taiwan, Yulon Motor, which

was subsidized by the KMT government and protected by high tariffs throughout its various developmental stages. In 2000, Yulon Motor Group owned 121

subsidiaries, operated in 26 broad industries, and was ranked 28th among the

100 largest business groups in Taiwan (China Credit Information Service,

Business Groups in Taiwan, 2002).

Fourth, political ties to the ruling party promote firm legitimacy.

Organizations embedded in social and normative contexts are under pressure

to justify their strategic actions to a range of constituents in society, including

608

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

the government, suppliers, and shareholders (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983). An

effective means of legitimation is to establish ties to prominent and legitimate

actors and institutions because the ties signal the focal organizations conformance with taken-for-granted institutional prescriptions that promote stakeholders endorsement and receptiveness (Meyer and Rowan, 1977; Baum and

Oliver, 1991). Previous studies have demonstrated that enhanced legitimacy

through ties to government agencies enables firms to better access support

and resources and in turn brings about competitive advantages, such as higher

survival rates (Baum and Oliver, 1991).

In emerging economies, legitimacy offers even more significant benefits

because of the lack of market intermediaries that can provide open, timely, and

sufficient valuation and assessment of firms. Peng, Lee, and Wang (2005) indicated that network ties to dominant institutions (e.g., financial institutions, government) in emerging economies serve as sources of legitimacy and that such

ties are generic and nonindustry-specific, enabling business groups to diversify

into different industries. Because the ruling party forms the core of the dominant institution, business groups likely enjoy increased legitimacy because of

their ties to the party, which facilitates resource acquisition and market entry.

In addition to facilitating entry, the ruling party may persuade connected

firms to enter new industries that these firms would otherwise avoid. States in

emerging economies often formulate policies to develop specific sectors that

are of strategic importance to the national economy (Amsden, 2001), and the

government might request affiliated firms to take a lead in such initiatives.

During the early industrialization of South Korea, the government designated

capital-intensive industries such as steel and shipbuilding strategic sectors

and encouraged politically connected firms to diversify into these sectors by

providing them with foreign technology, bank loans, and administrative privileges (Amsden, 1989). The above arguments lead to our first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The more political ties a business group has to the ruling party under

united government, the more unrelated industries it enters.

In contrast, ties to opposition parties under united government tend to

impede business groups market entry. Opposition parties without control of

the legislature can hardly provide information, resources, and privileges that

facilitate new market entry, and their failure in elections implies that their political agendas or candidates are less appealing and socially appropriate vis-a`-vis

the ruling partys. As a result, firms connected to opposition parties suffer from

impaired legitimacy, making it difficult for them to acquire from external stakeholders the information and resources necessary to implement their strategies.

Chi-Mei Group, a well-known loyal supporter of the DPP, suffered from a shortage of capital in its early years because banks, both state-owned and privately

owned, were reluctant to provide it with credit despite the healthy financial

standing of the group (Ju, 2003). As signals of focal firms distinct political position, ties to opposition parties are likely to result in the exclusion of resources,

information, and privileges and in impaired legitimacy, which inhibits focal firms

from entering targeted industries:

Hypothesis 2: The more political ties a business group has to an opposition party

under united government, the fewer unrelated industries it enters.

Zhu and Chung

609

The scenario is different under divided government. When the ruling party

controls only the executive branch, the resources it can steer to connected

firms are restricted. At the same time, facing power competition with the opposition party, the ruling party tends to rely on firms for electoral support and is

likely to try to satisfy their requests. Compared with the situation under united

government, firms are in a stronger bargaining position with the ruling party,

which improves their ability to extract desirable resources and privileges from

the executive branch. Our interviews in Taiwan indicated that after the DPP

came into power in 2000, most group leaders found it easier to make meeting

appointments with both the DPP and the KMT politicians, including President

Chen Shui-Bian. Chen, Shen, and Lins (2013) regression analysis of more than

69,000 bank-loan contracts showed that firms connected to the DPP received

more loan contracts and lower interest rates than firms connected to other

political parties. Although the ruling party under divided government is not as

powerful as its counterpart under united government, its success in a presidential election suggests that the majority of voters embrace its policy agenda and

administrative capability, rendering legitimacy to its governance and firms connected to it. Thus we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 3: The more political ties a business group has to the ruling party with

executive authority under divided government, the more unrelated industries it

enters.

Under a divided regime, ties to the opposition party with legislative authority

may also be conducive to new market entry. The opposition party can take

advantage of its legislative powers and propose bills that favor the connected

firms (Shaffer, 1995). It may also modify existing rules and regulations to

improve the firms competitive positions, such as by raising the costs for rivals

or lowering entry barriers for the firm (Siegel, 2004; Frynas, Mellahi, and

Pigman, 2006). Prior to 2001 in Taiwan, two large petrochemical corporations

dominated the petroleum industry. To enter this profitable field, Ho Tung, a

small petrochemical group, leveraged its political ties with the KMT legislators,

who lowered the requirements for daily oil-refining volume from 15,000 cubic

meters to 2,000, allowing the small group to enter the industry (Wealth

Magazine, 2001). Moreover, because the budget bill has to be passed each

year by the legislature, the opposition party with a majority in the legislature

may take this opportunity to make requests to the executive branch and divert

resources and privileges to favored firms. Thus we hypothesize:

Hypothesis 4: The more political ties a business group has to an opposition party

with legislative authority under divided government, the more unrelated industries

it enters.

Portfolio Diversity and Entry into New Industries

The hypotheses above treat political ties in a portfolio separately and emphasize their independent effects on the firm. But when a firm simultaneously connects to different political parties, the portfolio effectssynergies and conflicts

arising from the relationships among political parties, as well as those between

political parties and the firm (Vassolo, Anand, and Folta, 2004; Wassmer,

2010)may also influence the firms strategic actions. The paradox of such

610

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

portfolio effects is that a diverse portfolio that stands to produce tertius gaudens advantages and political flexibility for the focal firm may also induce discrimination and retribution from the ruling party and consequently constrain the

firms pursuit of strategies. The net effect of portfolio diversity is likely to vary

across different types of government, each of which represents a distinct competitive status of political parties.

Under united government, a diverse portfolio of political ties tends to inhibit

market entry by reducing the information and resources derived from ties to

the ruling party. Although ties to the ruling party facilitate market entry, being

friendly to rival political parties may reduce the level of trust granted by the ruling party so that the ties to the ruling party become less functional in accessing

resources. Research indicates that trust facilitates interorganizational

exchanges by motivating sharing, easing negotiations, and reducing conflicts

and opportunistic behavior (Gulati, 1995; Zaheer, McEvily, and Perrone, 1998).

The ruling partys distrust will adversely affect its exchange relationship with

the focal firm and the benefits offered to it. More importantly, maintaining ties

to opposition parties tends to be construed as disloyalty to the ruling party,

especially in new democracies where the prior authoritarian regime hardly tolerated opposition forces. Given the focal firms relatively weak bargaining power

under united government, diverse portfolios increase the probability that the

ruling party will direct discrimination and retribution toward the focal firm. In

South Korea, firms connected to the political enemies of the dominant parties

have difficulty in forming cross-border strategic alliances with foreign firms,

which offer advanced technological and managerial know-how, because of the

discrimination and resource exclusion imposed by the dominant political power

(Siegel, 2007). In Taiwan, Continental Engineering Group, which had been

linked to the KMT since its founding stage, started to build ties to and support

the DPP after the founders daughter took the helm. The group thereafter

found it increasingly difficult to bid successfully on government projects despite

its enduring ties with the KMT through its other senior family members.

Ultimately, it had to switch to foreign niche markets such as Saudi Arabia for

growth (Wealth Magazine, 2000). Under united government, while a focused

portfolio tied to the ruling party maintains continuous resource flow and facilitates new market entries of business groups, a diverse portfolio tends to constrain resource flow and reduce new market entries:

Hypothesis 5: The more diverse the portfolio of political ties a business group has to

political parties under united government, the fewer unrelated industries it enters.

Under a divided government, however, a portfolio of ties to both the ruling

party with executive authority and the opposition party with legislative authority

can promote market entry by providing tertius gaudens advantages, resource

diversity, and political flexibility while insulating the focal firm from political retribution. Unlike the case under united government, portfolio diversity under

divided government is less likely to motivate powerful political parties to punish

the focal firm because the firms bargaining position improves when its political

partners compete with each other. Each political party is more receptive to the

firms demands in return for electoral resources. Taking advantage of its role as

tertius gaudens (Simmel, 1922; Burt, 1992), the focal firm is able to secure a

variety of valuable resources and support, such as entry licenses and regulatory

Zhu and Chung

611

policies; cheap labor, land, and capital; and enhanced legitimacy, all of which

ease its market entries. Moreover, the focal firm may strategically allocate its

electoral resources, negotiate among competing parties to enhance its leverage on them, and maximize the return of its political capital. For instance, it is

alleged that prior to the 2004 presidential election, Formosa Plastic Group

secured promised policy favors from both the KMT and DPP candidates by

offering campaign contributions to both sides and providing the same information and policy recommendations for the chemicals industry (Wealth Magazine,

2004).

The political flexibility stemming from a diverse portfolio becomes particularly critical to successful market entry during the potential political turbulence

of divided government. By befriending politicians of different parties, the focal

firm is less likely to be targeted for retaliation by a new ruling party. As a result,

the firm can maintain a relatively stable and continuous flow of resources and

information from its portfolio of political ties during power transition.

Conversely, maintaining good relations with only one political party makes the

focal firm vulnerable to the adverse effects of regime change (Siegel, 2007).

Pacific Construction Group, an adherent of the KMT, experienced difficulty in

expanding its business portfolio because of the lack of financial resources after

the electoral turnover in 2000, with the average number of new market entries

dropping from 7 during 19941998 to only 1.6 during 20002004 and the ranking of its total assets among the largest business groups dropping from 31st in

1998 to 99th in 2004. In contrast, Formosa Plastic Group, once connected only

to the KMT, gradually diversified its political ties to both the KMT and the DPP

and continued to enter on average six new markets in the same periods. Its

ranking of total assets also remained stable (fourth in 1998 and fifth in 2004),

and it avoided adverse impacts when the DPP came to power in 2000 (Wealth

Magazine, 2002). Taken together, the favorable exchange conditions, tertius

gaudens advantages, and political flexibility afforded by diverse portfolios

enabled business groups to enter more unrelated industries:

Hypothesis 6: The more diverse the portfolio of political ties a business group has to

political parties under divided government, the more unrelated industries it enters.

Internal Resources and Capabilities, Portfolio Diversity, and Entry into

New Industries

Debt ratio as a contingency. The debt ratio of a firm indicates its dependence on external financial resources (Pfeffer, 1987; Baker, 1990). Highly leveraged firms have greater dependence on such resources relative to

counterparts with low debt ratios. Because political ties serve as an important

channel for external financial resources (Johnson and Mitton, 2003; Khwaja and

Mian, 2005), connections to the political power that controls sources of credit

are more valuable to highly leveraged groups than to less leveraged ones.

Under united government, the ruling party is likely to reward allies and constrain opponents by allocating bank loans to firms connected only to it but not

to firms tied also to other parties. Opposition parties are not able to provide

financial resources because of the lack of political power. As a result, a diverse

portfolio of political ties makes it more difficult for the focal firm to acquire bank

loans than for peers with focused portfolios and negatively affects the firms

612

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

strategic maneuvers. This negative effect on new market entry tends to be

greater for groups with a higher debt ratio because they have a more urgent

need for financial resources than groups with a low debt ratio:

Hypothesis 7a: The negative relationship between the diversity of a business groups

portfolio of political ties and its entry into unrelated industries under united government will be stronger as its debt ratio increases.

Under divided government, groups with a diverse portfolio of political ties

have opportunities to tap multiple sources of capital. On the one hand, the

ruling party can offer funds through state-owned banks. The DPP president

of Taiwan, Chen Shui-Bian, provided large amounts of preferential loans

through government-controlled financial institutions to groups that played an

important role in his reelection in 2004 (Wealth Magazine, 2004). On the

other hand, the opposition party with legislative authority may propose or

modify legislative bills in favor of the fundraising of connected groups.

Groups with diverse portfolios are able to enjoy greater financial flexibility

than counterparts with focused portfolios, and this benefit tends to be more

salient for highly leveraged groups than for those with lower debt ratios

because it relaxes the budget constraints of these groups and enables them

to invest in unrelated industries:

Hypothesis 7b: The positive relationship between the diversity of a business groups

portfolio of political ties and its entry into unrelated industries under divided government will be stronger as its debt ratio increases.

Experience in market entry as a contingency. Market entry is a learningby-doing process that allows firms to develop the internal capability to execute

projects and to accumulate and deploy tacit knowledge for setting up new

operations across different industries (Amsden and Hikino, 1994). Experience

in market entry therefore represents a firms internal capability of market entry

that can reduce its dependence on political ties to acquire resources and privileges for expansion. First, experienced firms are able to use available resources

efficiently to enter new markets by applying learned technologies and managerial skills (Amsden and Hikino, 1994; Kock and Guillen, 2001). They are able to

deploy fewer resources than less-experienced firms in entering new industries.

Second, besides political ties, experienced firms usually have multiple channels

for acquiring resources, including strategic alliances with foreign providers of

technology and finance (Khanna and Palepu, 1997). For instance, Formosa

Plastics, a petrochemical group with rich experience in market entry, had 21

external linkages with foreign companies and venture capitalists in 1998, while

a less-experienced counterpart, Chang Chun Petrochemical, had only six external linkages (Sheng, 2003).

When the ruling party dominates in political power, firms experienced in

market entry may be damaged less by diverse portfolios of political ties than

less-experienced ones. Because of their superior efficiency in deploying

resources, as well as more alternative sources of resources, experienced

groups suffer less from the resource exclusion imposed by the ruling party:

Zhu and Chung

613

Hypothesis 8a: The negative relationship between the diversity of a business groups

portfolio of political ties and its entry into unrelated industries under united government will be weaker as its experience in market entry increases.

By the same token, under divided government, experienced groups are less

susceptible to the political flexibility and tertius gaudens benefits of diverse

political ties than less-experienced groups when entering new markets.

Because of their highly efficient use of resources to set up operations in new

industries and their extensive links to various external organizations, groups

with rich experience in market entry do not necessarily rely on political ties

to gain access to desirable resources. Therefore they are likely to benefit to a

lesser extent from the stable and diverse flows of resources provided by

diverse portfolios of political ties than groups with scant experience in market entry:

Hypothesis 8b: The positive relationship between the diversity of a business groups

portfolio of political ties and its entry into unrelated industries under divided government will be weaker as its experience in market entry increases.

METHODS

Data Source and Sample

Our empirical analysis is based on a unique dataset of 290 distinct business

groups and their 5,997 member firms in Taiwan over two periods: 19982000

and 20042006. Our design captures rivalry situations in which the ruling and

opposition parties switched (i.e., before and after the 2000 presidential election). Because the regime change in 2000 was unexpected and driven by political and social forces largely exogenous to business groups (Yeh, Shu, and

Chiu, 2013), it was an external shock that helped identify the contingent role of

political ties in turbulent environments. By collecting information about political

ties in 1998 and 2004, we estimated the market entry activities of business

groups during 19982000 and 20042006.

Our main data source was the Business Groups in Taiwan (BGT) directory,

compiled by the China Credit Information Service (CCIS), the oldest and most

prestigious credit-checking agency in Taiwan and an affiliate of Standard &

Poors. The BGT lists information about the top groups, on the basis of sales,

whose principal firms are registered in Taiwan. The number of business groups

in the BGT differed slightly over the years: 180 in 1998 and 250 in 2004. The

CCIS defines a business group as a coherent business organization including

several independent enterprises, and it has long used the following criteria in

its selection of business groups to include in the BGT: (1) more than 51 percent

of ownership must be native capital; (2) the group includes three or more independent firms; (3) the group achieves more than NT$5 billion in total sales

(though this value has changed as business groups grew larger); and (4) the

core firm of the group is registered in Taiwan. This directory is the most comprehensive and reliable source of business groups in Taiwan and has been used

in previous studies (Guillen, 2000; Khanna and Rivkin, 2001; Luo and Chung,

2005). To our knowledge, our research covers the largest number of business

groups in Taiwan. In addition, we referred to the Largest Corporations in

614

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

Taiwan, also published by CCIS, to collect data on sales and return on assets

(ROA) at the industry level.

For each business group, the directory provides information about top management, size, history, and financial performance. For each member firm, it

also provides information about the line of business, which we used to identify

its industry. Because no ready-to-use industry coding is available in the BGT,

the first author assigned the 4-digit Standard Industrial Classification (SIC) code

to the industry of the firm by matching the product/service information and the

description of the 4-digit SIC industry in the Standard Industrial Classification

published by the Economic Ministry of Taiwan in 2006. The second author independently coded 10 percent of randomly selected cases and located 1 percent

as cases of divergent coding. According to the consensus of the two authors,

the first author then recoded all the cases with divergent coding. In total, a

4-digit SIC code was assigned for 2,454 group member firms in 1998, 5,865 in

2000, 7,534 in 2004, and 8,804 in 2006. We then used the first two digits of

the 4-digit codes as our 2-digit coding to denote unrelated industries. By aggregating the industry information of all member firms at the group level, we

determined the industrial portfolio of each group. We tracked entry activities by

comparing the groups industrial portfolios across the two-year spans (1998

2000 and 20042006). Groups entered unrelated industries if those 2-digit

industries that were not present at time t appeared at time t + 2 in their industrial profiles. We included groups that appeared in two consecutive issues of

the BGT. There were 167 observations in the 1998 sample and 227 in the 2004

sample.

For political ties, we relied on matching names from a wide range of publicly

available data sources. The names of group leaders, including board chairs,

CEOs, and major shareholders of the group affiliates, came from the BGT. For

group firms listed in the Taiwan Stock Exchange, we also collected the names

of CEOs, major shareholders, directors, and auditors of the board from the

Taiwan Economic Journal (TEJ) database. To the extent that Taiwanese firms

prefer to nominate family members, trusted persons, or business associates as

directors and auditors, it is the people in these positions who are likely to provide the conduits for firms to connect to their external environment. In total,

we collected 2,716 names in 1998 and 3,086 in 2004.

For political party figures, we gathered the names of the KMT and DPP central committee members from their websites (http://www.kmt.org.tw and

http://www.dpp.org.tw) and the proceedings of party conventions.3 We also

collected lists of national and provincial administrators (e.g., ministers and viceministers of different ministries, directors and deputy directors of departments,

major officers in provincial government) from the website of the Taiwanese

government directory (http://twinfo.ncl.edu.tw). We found members of the

national and provincial legislatures and judiciary, together with their party affiliations, on the legislative website (http://www.ly.gov.tw) and the website of the

judicial institution, the Judicial Yuan (http://www.judicial.gov.tw). In total, we

gathered 3,725 politicians names in 1998 and 3,905 names in 2004.

3

We did not include ties to other political parties because of their trivial influence on Taiwans politics. Other political parties collectively obtained 0.8 percent of the votes in the 2000 presidential

election, and their combined influence in the Legislative Yuan was limited to 10 to 14 percent of

the seats.

Zhu and Chung

615

We turned to three additional sources to identify the social relationships

between business group leaders and political actors. First, we checked the

Excellent Business Database System (EBDS) (http://ebds.anyan.com.tw),

which covers more than 200 periodicals and newspapers published in Taiwan

and provides full-text searching. Second, we searched Wealth Magazines database, which provides extensive periodical reports on interactions between

large business groups and political actors. The breadth and depth of these

reports is comparable to those published in Business Week, Fortune, the New

York Times, and the Wall Street Journal. Third, we examined research articles,

dissertations, autobiographies of group founders, and books devoted to this

topic (e.g., Xu, 1992; Chen, 1994; Wang, 2006).

Considering the various ways business leaders and political actors connect

in Taiwan, we differentiated two types of political ties: formal position interlocks and informal ties. For the formal ties, we matched the list of names of

business group leaders with that of political actors. The number of overlaps

indicated the number of formal political ties maintained by the business group.

For informal ties, we considered family and social relationships between group

executives and political party leaders. We coded three types of prevalent informal ties in Taiwan: (1) familial and marital ties, (2) close friendships and samehometown relationships, and (3) trade associations and social club memberships. We coded specific informal relationships that had been identified and

reported in the data sources rather than using demographic information (i.e.,

birthplace) or membership of social clubs to infer relationships between leaders

and politicians (Useem, 1979), as people from the same hometown or who join

the same social club do not necessarily know each other. We searched reports

in our data sources regarding each of the business groups by using group

names and group leaders names, as well as key words such as relationships

(guanxi) and businessgovernment relationships (cheng shang guanxi). Both

authors then read the entire article or monograph to identify and code the informal ties separately and subsequently exchanged the coding for doublechecking and confirmation.

A business group has a family/intermarriage tie if one of its top managers or

major shareholders has a tie of kinship or marriage with a political actor. For

example, Wang Yu-Chen, the top officer of Hwa Eng Wire & Cable Group, is

the younger brother of Wang Yu-Yun, who was once the mayor of Kaoshiung

City and a member of the KMTs central committee. Thus we coded Hwa Eng

Wire & Cable Group as having one informal political tie connected to the KMT.

Another example comes from Ho Tung Group: the eldest daughter of the former chairman of the KMT, Lien Chan, married the son of Ho Tungs deputy

chair of the board, Chen Ching-Chung.

A second type of informal political tie forms when top managers or major

shareholders of a business group are close friends with or are from the same

hometown as political actors. An example is the long-established friendship

between a major shareholder of Lin Yuan Group, Tsai Hung-Tu, and the president of Taiwan, Chen Shui-Bian. They were classmates at Taiwan National

University and have remained close.

Finally, informal political ties may be established when top managers or large

shareholders of business groups join national trade associations or elite social

clubs. For example, China Rebar Group was politically connected to the KMT

because its president, Wang Yu-Tseng, was the chairman of the National

616

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

Federation of Commerce, an important trade association through which the

KMT consulted and executed its economic policies. Chen Sheng-Tien, the top

officer of Sampo Group, was a member of a prestigious golf club where business magnates and political leaders often gathered to play golf.

After combining formal and informal political ties, we counted the number of

political ties with each political party according to the party affiliation of each

connected politician. We further supplemented our quantitative data with 15

interviews with political insiders such as legislators, journalists, management

scholars, and political scientists in Taipei during 2010 to 2011 to gain a better

understanding of the functioning of political ties.

Our coding and measure of political ties is unique in two respects. First,

instead of adopting indirect approaches, such as subject ratings or reports by

other agencies (e.g., Fisman, 2001; Bertrand et al., 2004), we used a direct

approach to locate specific ties between business executives and politicians.

Second, most existing studies have adopted synchronized research designs

that examine political ties and firm strategy at the same point in time. We collected data from two time periods (1998 and 2004), which not only enabled us

to identify the role of political ties in a changing political landscape but also

helped us address the causal ambiguity between political ties and firm

strategy.

Dependent Variable: Entry into New Industries

To test the proposed relationships between political ties and market entry activities, we counted the number of entries into new 2-digit SICs in two two-year

periods, from 1998 to 2000 and from 2004 to 2006. We also used a continuous

measure for unrelated entry by using the data of interindustry relatedness from

the inputoutput table, and our results were unchanged. Additionally, extending

the time span to four years (19982002 and 20042008) did not change our

results qualitatively.

Independent Variables

We counted the number of ties between a group and political parties, distinguishing ties with the KMT from ties with the DPP. We then measured the

diversity of portfolios using the Blau Index of Variability, which computes portfolio diversity as one minus the sum of the squared proportions of a focal business groups ties with each of the political parties (Blau, 1977). Specifically, the

diversity of a portfolio of political ties is given by

D =1

k

X

Pi2

i =1

where D represents the diversity measure, P represents the proportion of political ties with a particular political party out of all the political ties, and i is the

number of different political parties. The index ranges from 0 (a completely

homogeneous portfolio) to 1 (a perfectly heterogeneous portfolio with political

ties evenly distributed among all political parties). This measure has been

widely used in the social network literature to measure the heterogeneity of

Zhu and Chung

617

portfolios of ties (e.g., Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman, 2000; Jiang, Tao, and

Santoro, 2010).

Control Variables

As in previous studies (Chang, 1996; Khanna and Palepu, 2000a), we controlled

for group characteristics that may affect a groups entry activities. Group size

was the logged total group assets adjusted by the 2000 consumer price index

(Taiwan Statistical Data Book, 2000: 179). Group age was the number of years

since the first member firm of a group was established. Group ROA referred to

the annual return on assets for the group, and debt ratio was the ratio of liability

to

P total assets. For group diversification, we used the entropy formula

Pj 1n(1=Pj ), with Pj as the percentage of group sales in industry sector j

(Palepu, 1985). We identified the industry sector based on the 2-digit product

categories detailed in the 2006 SIC listing. Experience in market entry reflected

the total number of market entries conducted by the group since 1990, the

onset of large-scale economic liberalization in Taiwan.

The majority of Taiwanese business groups are family owned, and the controlling family plays a critical role in strategic decision making (Luo and Chung,

2005). We controlled for family ownership in a business group, calculated as a

weighted average (affiliate assets as a percentage of group assets) of family

ownership in all group affiliates. Family ownership in an affiliate is the percentage of shares owned by family members and other affiliates that are directly or

indirectly controlled by family members (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and

Shleifer, 1999). Previous studies have shown a significant association between

a firms political ties and the industries in which the firm operates (Agrawal and

Knoeber, 2001; Hillman, 2005; Li, Poppo, and Zhou, 2008). We calculated sales

from regulated sectors as the percentage of sales from regulated sectors relative to the total group sales. We identified the regulated sectors on the basis of

the industrial policies of the Ministry of Economic Affairs of the Taiwanese government (http://www.moea.gov.tw/Mns/populace/home/Home.aspx). Group

patents indicate the innovativeness of groups, which may affect their ability to

enter new industries and to establish political ties with political parties. We collected the number of successful patent applications of each member firm in

each group by referring to the Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (http://

www.patent.org.tw) and then aggregated the number of patents of each member firm to the group level. We also controlled for the main industry of the

group in 13 industriesagriculture, food, textile, wood, chemical, nonmetallic,

metals, machinery, electrical/electronic, construction, real estate and financial

services, wholesale and retail, and other service industriesusing the industry

with the largest proportion of group sales. On average, the major business line

contributed 67 percent to group sales. To the extent that entry and exit activities correlated, such as when business groups exited less-profitable industries

to focus on more-profitable ones (Chang, 1996; Chung and Luo, 2008), we controlled for the number of exits from incumbent 2-digit SIC industries.

Finally, we created two industry-level variables to capture the attractiveness

of entered industries (Porter, 1980). Industry profitability aggregated the ROA

of industries that business groups entered, weighted by the percentage of

group sales in the entered industries. Industry sales, indicating industry attractiveness in terms of sales volume, used the aggregate sales in industries that

618

Administrative Science Quarterly 59 (2014)

groups entered, weighted by the percentage of group sales in the entered

industries.

RESULTS

Tables 2a and 2b show the summary statistics for the variables and their correlation matrix for 1998 and 2004, respectively. We find significant variance in the

entry activities of business groups, as well as in their political ties to the KMT

and the DPP, in both periods. The mean of portfolio diversity increases from

0.04 in 1998 to 0.18 in 2004, suggesting that business groups diversified their

portfolios of political ties during 19982004. We also find significant correlations among political tie variables and between political tie variables and group

characteristic variables. Yet the variance inflation factor (VIF) for each explanatory variable is less than 10, indicating that the multicollinearity problem might

Table 2a. Correlation Matrix (1998)

Variable

Mean

S.D.

1. Number of entries

2. Number of exits

3. Number of political ties with KMT

4. Number of political ties with DPP

5. Portfolio diversity

6. Group diversification

7. Group size (logged assets)

8. Group age

9. Group ROA

10. Group patents

11. Debt ratio

12. Experience in market entry

13. Family ownership

14. % of sales from regulated sectors

15. Industry profitability

16. Industry sales

17. Portfolio diversity Debt ratio

18. Portfolio diversity Experience

in market entry

4.33

1.38

4.43

.13

.04

.84

9.97

3.85

3.25

6.78

50.00

3.96

10.04

19.20

4.08

23.19

12.01

1.13

3.18

0

18

1.27

0

7

8.78

0

69

.50

0

5

.11

0

.50

.58

0

2.46

1.54

6.40 13.82

12.77

8

80

10.41 66.27 45.56

25.99

0

234

17.37 14.61 89.07

2.65

0

18

13.42

.61 84.41

33.14

.00 100.00

2.11 4.16 14.22

13.44 6.25 70.68

15.74

.00 34.01

1.43

.00 12.07

Variable

9. Group ROA

10. Group patents

11. Debt ratio

12. Experience in market entry

13. Family ownership

14. % of sales from regulated sectors

15. Industry profitability

16. Industry sales

17. Portfolio diversity Debt ratio

18. Portfolio diversity Experience

in market entry

p < .05.

Min.

Max.

.26

.57

.01

.14

.51

.61

.27

.01

.03

.13

.21

.23

.08

.17

.05

.24

.23

.08

.15

.14

.10

.08

.28 .42

.17 .45

.31 .26

.21 .08

.05

.00

.10

.31

.15

.36

.14 .21

.04

.17

.06

.11

.12

.01

.03 .20

.09

.03

.59

.09

.24

.04

.03

.07

.11

.03

.06

.14

.06

.07

.18

.25

.08

.06

.11

.09

.11

.16

.13

.06

.05

.06

.04

.07

.32

.49

.45

.12

.02

.23

.38

.44

.07

.09

.08

.21

.06

.30

.11

.24

.43

.26

.40

.32

.01

.03

.24

.06

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

.17

.13

.11

.08

.24

.02

.04

.06

.08

.16

.02

.41

.04

.03

.21

.01

.01

.05

.08

.11

.01

.01

.10

.10

.12

.09

.06

.18

.18

.48

.01

.05

.30

.06

.08

.08

.16

.01

.13

.32

.15

.08

.12

.10

.02

.08

.06

.14

.06

.08

.01

.07

.03

.08

.10

Zhu and Chung

619

Table 2b. Correlation Matrix (2004)

Variable

Mean

1. Number of entries

2. Number of exits

3. Number of political ties with KMT

4. Number of political ties with DPP

5. Portfolio diversity

6. Group diversification

7. Group size (logged assets)

8. Group age

9. Group ROA

10. Group patents

11. Debt ratio

12. Experience in market entry

13. Family ownership

14. % of sales from regulated sectors

15. Industry profitability

16. Industry sales

17. Portfolio diversity Debt ratio

18. Portfolio diversity Experience

in market entry

1.84

2.29

0

15

1.44

1.73

0

10

.47

2.81

7.27

0

65

.55 .62

.83

1.78

0

10

.38 .25 .34

.18

.20

0

.50 .32 .07

.12

.52

.95

.55

0

2.58 .34 .52 .42 .24

10.46

1.49

8.64

14.84 .40 .48 .30 .53

26.67 13.94

0

59

.29 .29 .28 .07

4.33

6.25 14.87

31.50 .10

.21 .12 .05

79.35 307.03

0

2805

.23 .03

.01

.15

56.42 18.41

6.89

96.24 .17 .25 .27 .26

6.71

5.68

0

44

.12

.27 .31 .21

8.46

7.85

.67

70.07 .19 .22 .22 .14

21.36 32.08

.00 100.00 .20 .26 .29 .34

7.77

3.89 4.76

33.53 .10

.13 .11 .02

27.59 15.23

2.04 107.13 .01 .07

.01

.09

11.85 14.22

.00

47.40 .19

.02

.07

.27

1.45

2.67

.00

15.45 .23 .09 .04 .04

Variable

9. Group ROA

10. Group patents

11. Debt ratio

12. Experience in market entry

13. Family ownership

14. % of sales from regulated sectors

15. Industry profitability

16. Industry sales

17. Portfolio diversity Debt ratio

18. Portfolio diversity Experience

in market entry

S.D.

Min.

Max.

.12

.44 .52

.04

.28

.01 .24

.02

.13

.12

.20

.08

.24

.09 .21

.25 .26

.05

.08

.01 .06

.34 .06

.08

.04

.05

.15

.32

.38

.20

.21

.54

.10

.12

.22

.07

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

.08

.04

.05

.04

.10

.13

.06

.03

.14

.22

.14

.51

.02

.10

.13

.01

.11

.15

.10

.10

.05

.10

.04

.04

.07

.02

.02

.10

.12

.41

.05

.28

.29

.08

.17

.09

.10

.08

.05

.20

.13

.00

.01

.01

.03

.10

.12

.15

.02

.14

.16

.06

.17

.02

.04

p < .05.

not be serious in the estimation (Neter, Wasserman, and Kunter, 1990). Among

the 103 politically connected business groups in 1998, 87 were connected only

to the KMT, and the remaining 16 were connected to both the KMT and the

DPP. In 2004, however, among the 103 business groups with political ties, 36

groups were tied solely to the KMT, 16 groups were connected only to the

DPP, and 51 were connected to both the KMT and the DPP.

Regression Results

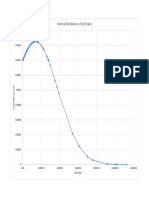

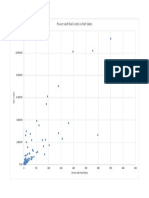

Given that the number of market entries, our dependent variable, is a count

variable and that our market entry data are overdispersed, the Poisson model is