Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ursula Franklin 1

Ursula Franklin 1

Uploaded by

Samwise DabraveCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grandpas Farm (Possible Worlds Games) - UV6yOlDocument28 pagesGrandpas Farm (Possible Worlds Games) - UV6yOlhjorhrafnNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Luis Barragán, de Antonio RiggenDocument83 pagesLuis Barragán, de Antonio RiggenJorge Octavio Ocaranza VelascoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ursula FranklinDocument1 pageUrsula FranklinSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Le Port-Marly Château de Monte-Cristo: GeorgesDocument1 pageLe Port-Marly Château de Monte-Cristo: GeorgesSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- The Count of Monte Cristo The Three Musketeers Twenty Years After The Vicomte de Bragelonne: Ten Years Later The Knight of Sainte-HermineDocument1 pageThe Count of Monte Cristo The Three Musketeers Twenty Years After The Vicomte de Bragelonne: Ten Years Later The Knight of Sainte-HermineSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 1Document1 pageMachu Picchu 1Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 7Document1 pageMachu Picchu 7Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Revolution Charles X Duke of Orléans Louis-PhilippeDocument1 pageRevolution Charles X Duke of Orléans Louis-PhilippeSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 4Document1 pageMachu Picchu 4Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice and Mysticism: GeographyDocument1 pageHuman Sacrifice and Mysticism: GeographySamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 5Document1 pageMachu Picchu 5Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Ratnagari, Kumud's Village, and Visits Her House. However, As Time Goes On, Saras Begins ToDocument1 pageRatnagari, Kumud's Village, and Visits Her House. However, As Time Goes On, Saras Begins ToSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Qualified Teams: Team Qualified For Finals Team Failed To QualifyDocument1 pageQualified Teams: Team Qualified For Finals Team Failed To QualifySamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu (In Hispanicized Spelling, Pikchu (: Inti WatanaDocument1 pageMachu Picchu (In Hispanicized Spelling, Pikchu (: Inti WatanaSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Henrik Stenson 2Document1 pageHenrik Stenson 2Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- 1976 Summer Olympics MontrealDocument1 page1976 Summer Olympics MontrealSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Bless The Beasts and Children: Robert RigerDocument1 pageBless The Beasts and Children: Robert RigerSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Parinda 1942: A Love Story Kareeb Khamoshi: The Musical Hum Dil de Chuke SanamDocument1 pageParinda 1942: A Love Story Kareeb Khamoshi: The Musical Hum Dil de Chuke SanamSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Changes and Adaptations: Konstantinos Zappas George AveroffDocument1 pageChanges and Adaptations: Konstantinos Zappas George AveroffSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Nadia ComaneciDocument1 pageNadia ComaneciSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Weather Forecast: by Vass Tunde Juen, 1 Verbal and Non-Verbal CommunicationDocument5 pagesWeather Forecast: by Vass Tunde Juen, 1 Verbal and Non-Verbal CommunicationAlina-Cristina CotoiNo ratings yet

- Banking Law On Secrecy of Bank DepositsDocument29 pagesBanking Law On Secrecy of Bank DepositsbrendamanganaanNo ratings yet

- Notch 8 Status - Jan 23 - v2Document1 pageNotch 8 Status - Jan 23 - v2qhq9w86txhNo ratings yet

- Floyd Edwrads Memorial Scholarship Terms of Reference 2017Document3 pagesFloyd Edwrads Memorial Scholarship Terms of Reference 2017Aswin HarishNo ratings yet

- Ca17 Activity 1Document2 pagesCa17 Activity 1Mark Kenneth CeballosNo ratings yet

- Members Members Shohanur Rahman Rahnuma Nur Elma Adnan Sami Khan Fatema Tuz Zohora Hasan UZ Zaman Safika Mashiat Sunjana Alam SamaDocument11 pagesMembers Members Shohanur Rahman Rahnuma Nur Elma Adnan Sami Khan Fatema Tuz Zohora Hasan UZ Zaman Safika Mashiat Sunjana Alam SamaShohanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- ABB Fittings PlugsDocument204 pagesABB Fittings PlugsjohnNo ratings yet

- Film - The GuardianDocument1 pageFilm - The GuardianfisoxenekNo ratings yet

- The Oriental Insurance Company LimitedDocument3 pagesThe Oriental Insurance Company Limitedrajeevjayan18No ratings yet

- Bir Regulations MonitoringDocument87 pagesBir Regulations MonitoringErica NicolasuraNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Vs GellaDocument33 pagesRodriguez Vs GellaRozaiineNo ratings yet

- Status of Led Lighting World Market 2020 Final Rev 2Document82 pagesStatus of Led Lighting World Market 2020 Final Rev 2javadeveloper lokeshNo ratings yet

- Laurie Baker: (The Brick Master of Kerala)Document8 pagesLaurie Baker: (The Brick Master of Kerala)Malik MussaNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Kitchen EssentialsDocument45 pagesReviewer Kitchen EssentialsMiren ParrenoNo ratings yet

- FILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20Document28 pagesFILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20ArpoxonNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Lesson 2 Tongue TwistersDocument14 pagesWeek 1 Lesson 2 Tongue Twistersapi-246058425No ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument9 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelharpritahingoraniNo ratings yet

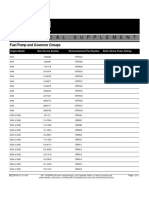

- FuelPump&GovernorGroups SELD0135 11Document11 pagesFuelPump&GovernorGroups SELD0135 11narit00007No ratings yet

- PHD Thesis Library Science DownloadDocument8 pagesPHD Thesis Library Science Downloadyvrpugvcf100% (2)

- Calculate Size of SolarDocument2 pagesCalculate Size of SolarMuhammad SalmanNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Fourtower Bridge: A Paths Peculiar Module For Fantasy Roleplaying GamesDocument7 pagesWelcome To Fourtower Bridge: A Paths Peculiar Module For Fantasy Roleplaying GamesTapanco BarerraNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order: NPWP: 03.343.037.2-047.000 12208599Document2 pagesPurchase Order: NPWP: 03.343.037.2-047.000 12208599Oscar OkkyNo ratings yet

- Draft of The Newsletter: Trends in LeadershipDocument3 pagesDraft of The Newsletter: Trends in LeadershipAgus BudionoNo ratings yet

- CodaDocument15 pagesCodaShashi KartikyaNo ratings yet

- Cut 120Document128 pagesCut 120Jimmy MyNo ratings yet

- The 7 SealDocument11 pagesThe 7 Sealendalkachew gudeta100% (1)

- CGR Project Report DDGGDDDocument21 pagesCGR Project Report DDGGDDTanvi KodoliNo ratings yet

- MSDS - Prominent-GlycineDocument6 pagesMSDS - Prominent-GlycineTanawat ChinchaivanichkitNo ratings yet

Ursula Franklin 1

Ursula Franklin 1

Uploaded by

Samwise DabraveCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ursula Franklin 1

Ursula Franklin 1

Uploaded by

Samwise DabraveCopyright:

Available Formats

Early life[edit]

Ursula Maria Martius[12] was born in Munich, Germany on September 16, 1921.[3][13][14] Her mother

was Jewish and an art historian[15] and her father, an ethnographer,[15] came from an old German

Protestant family.[12] Because of the Nazi persecution of the Jews, her parents tried to send their

only child to school in Britain when World War II broke out, but the British refused to issue a

student visa to anyone under 18. Ursula studied chemistry and physics at Berlin University until

she was expelled by the Nazis.[12] Her parents were interned in concentration camps while

Franklin herself was sent to a forced labour camp. The family survived The Holocaust and was

reunited in Berlin after the war.[16]

Academic career[edit]

Franklin decided to study science because she went to school during a time when the teaching of

history was censored. "I remember a real subversive pleasure," she told an interviewer many

years later, "that there was no word of authority that could change either the laws of physics or

the conduct of mathematics."[16] In 1948, Franklin received herPh.D. in experimental physics at

the Technical University of Berlin.[17] She began to look for opportunities to leave Germany after

realizing there was no place there for someone fundamentally opposed to militarism and

oppression. Franklin moved to Canada after being offered the Lady Davis postdoctoral fellowship

at the University of Toronto (U of T) in 1949.[12][15] She then worked for 15 years (from 1952 to

1967) as first a research fellow and then as a senior research scientist at the Ontario Research

Foundation.[15][16][12] In 1967, Franklin became a researcher and associate professor at the

Department of Metallurgy and Materials Science University of Toronto's Faculty of Engineering

where she was an expert in metallurgy and materials science.[12] She was promoted to full

professor in 1973 and was given the designation of University Professor in 1984, becoming the

first female professor to receive the university's highest honour.[1][16][12][18] She was

appointed professor emerita in 1987,[12] a title she retained until her death.[15] She served as

director of the universitys Museum Studies Program from 1987 to 1989, was named a Fellow of

the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education in 1988, and a Senior Fellow ofMassey College in

1989.[12]

Scientific research[edit]

Franklin was a pioneer in the field of archaeometry, which applies modern materials analysis

to archaeology. She worked for example, on the dating of prehistoric bronze, copper and ceramic

artifacts.[19] In the early 1960s, Franklin investigated levels of strontium-90

aradioactive isotope in fallout from nuclear weapons testingin children's teeth.[19] Her research

contributed to the cessation ofatmospheric weapons testing.[16][15] Franklin published more than a

hundred scientific papers and contributions to books on the structure and properties of metals

and alloys as well as on the history and social effects of technology.[20]

As a member of the Science Council of Canada during the 1970s, Franklin chaired an influential

study on conserving resources and protecting nature. The study's 1977 report, Canada as a

Conserver Society, recommended a wide range of steps aimed at reducing wasteful

consumption and the environmental degradation that goes with it.[21] The work on that study

helped shape Franklin's ideas about the complexities of modern technological society.[22]

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grandpas Farm (Possible Worlds Games) - UV6yOlDocument28 pagesGrandpas Farm (Possible Worlds Games) - UV6yOlhjorhrafnNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Luis Barragán, de Antonio RiggenDocument83 pagesLuis Barragán, de Antonio RiggenJorge Octavio Ocaranza VelascoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ursula FranklinDocument1 pageUrsula FranklinSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Le Port-Marly Château de Monte-Cristo: GeorgesDocument1 pageLe Port-Marly Château de Monte-Cristo: GeorgesSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- The Count of Monte Cristo The Three Musketeers Twenty Years After The Vicomte de Bragelonne: Ten Years Later The Knight of Sainte-HermineDocument1 pageThe Count of Monte Cristo The Three Musketeers Twenty Years After The Vicomte de Bragelonne: Ten Years Later The Knight of Sainte-HermineSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 1Document1 pageMachu Picchu 1Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 7Document1 pageMachu Picchu 7Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Revolution Charles X Duke of Orléans Louis-PhilippeDocument1 pageRevolution Charles X Duke of Orléans Louis-PhilippeSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 4Document1 pageMachu Picchu 4Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice and Mysticism: GeographyDocument1 pageHuman Sacrifice and Mysticism: GeographySamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu 5Document1 pageMachu Picchu 5Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Ratnagari, Kumud's Village, and Visits Her House. However, As Time Goes On, Saras Begins ToDocument1 pageRatnagari, Kumud's Village, and Visits Her House. However, As Time Goes On, Saras Begins ToSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Qualified Teams: Team Qualified For Finals Team Failed To QualifyDocument1 pageQualified Teams: Team Qualified For Finals Team Failed To QualifySamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Machu Picchu (In Hispanicized Spelling, Pikchu (: Inti WatanaDocument1 pageMachu Picchu (In Hispanicized Spelling, Pikchu (: Inti WatanaSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Henrik Stenson 2Document1 pageHenrik Stenson 2Samwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- 1976 Summer Olympics MontrealDocument1 page1976 Summer Olympics MontrealSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Bless The Beasts and Children: Robert RigerDocument1 pageBless The Beasts and Children: Robert RigerSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Parinda 1942: A Love Story Kareeb Khamoshi: The Musical Hum Dil de Chuke SanamDocument1 pageParinda 1942: A Love Story Kareeb Khamoshi: The Musical Hum Dil de Chuke SanamSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Changes and Adaptations: Konstantinos Zappas George AveroffDocument1 pageChanges and Adaptations: Konstantinos Zappas George AveroffSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Nadia ComaneciDocument1 pageNadia ComaneciSamwise DabraveNo ratings yet

- Weather Forecast: by Vass Tunde Juen, 1 Verbal and Non-Verbal CommunicationDocument5 pagesWeather Forecast: by Vass Tunde Juen, 1 Verbal and Non-Verbal CommunicationAlina-Cristina CotoiNo ratings yet

- Banking Law On Secrecy of Bank DepositsDocument29 pagesBanking Law On Secrecy of Bank DepositsbrendamanganaanNo ratings yet

- Notch 8 Status - Jan 23 - v2Document1 pageNotch 8 Status - Jan 23 - v2qhq9w86txhNo ratings yet

- Floyd Edwrads Memorial Scholarship Terms of Reference 2017Document3 pagesFloyd Edwrads Memorial Scholarship Terms of Reference 2017Aswin HarishNo ratings yet

- Ca17 Activity 1Document2 pagesCa17 Activity 1Mark Kenneth CeballosNo ratings yet

- Members Members Shohanur Rahman Rahnuma Nur Elma Adnan Sami Khan Fatema Tuz Zohora Hasan UZ Zaman Safika Mashiat Sunjana Alam SamaDocument11 pagesMembers Members Shohanur Rahman Rahnuma Nur Elma Adnan Sami Khan Fatema Tuz Zohora Hasan UZ Zaman Safika Mashiat Sunjana Alam SamaShohanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- ABB Fittings PlugsDocument204 pagesABB Fittings PlugsjohnNo ratings yet

- Film - The GuardianDocument1 pageFilm - The GuardianfisoxenekNo ratings yet

- The Oriental Insurance Company LimitedDocument3 pagesThe Oriental Insurance Company Limitedrajeevjayan18No ratings yet

- Bir Regulations MonitoringDocument87 pagesBir Regulations MonitoringErica NicolasuraNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez Vs GellaDocument33 pagesRodriguez Vs GellaRozaiineNo ratings yet

- Status of Led Lighting World Market 2020 Final Rev 2Document82 pagesStatus of Led Lighting World Market 2020 Final Rev 2javadeveloper lokeshNo ratings yet

- Laurie Baker: (The Brick Master of Kerala)Document8 pagesLaurie Baker: (The Brick Master of Kerala)Malik MussaNo ratings yet

- Reviewer Kitchen EssentialsDocument45 pagesReviewer Kitchen EssentialsMiren ParrenoNo ratings yet

- FILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20Document28 pagesFILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20ArpoxonNo ratings yet

- Week 1 Lesson 2 Tongue TwistersDocument14 pagesWeek 1 Lesson 2 Tongue Twistersapi-246058425No ratings yet

- Cambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelDocument9 pagesCambridge International Advanced Subsidiary and Advanced LevelharpritahingoraniNo ratings yet

- FuelPump&GovernorGroups SELD0135 11Document11 pagesFuelPump&GovernorGroups SELD0135 11narit00007No ratings yet

- PHD Thesis Library Science DownloadDocument8 pagesPHD Thesis Library Science Downloadyvrpugvcf100% (2)

- Calculate Size of SolarDocument2 pagesCalculate Size of SolarMuhammad SalmanNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Fourtower Bridge: A Paths Peculiar Module For Fantasy Roleplaying GamesDocument7 pagesWelcome To Fourtower Bridge: A Paths Peculiar Module For Fantasy Roleplaying GamesTapanco BarerraNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order: NPWP: 03.343.037.2-047.000 12208599Document2 pagesPurchase Order: NPWP: 03.343.037.2-047.000 12208599Oscar OkkyNo ratings yet

- Draft of The Newsletter: Trends in LeadershipDocument3 pagesDraft of The Newsletter: Trends in LeadershipAgus BudionoNo ratings yet

- CodaDocument15 pagesCodaShashi KartikyaNo ratings yet

- Cut 120Document128 pagesCut 120Jimmy MyNo ratings yet

- The 7 SealDocument11 pagesThe 7 Sealendalkachew gudeta100% (1)

- CGR Project Report DDGGDDDocument21 pagesCGR Project Report DDGGDDTanvi KodoliNo ratings yet

- MSDS - Prominent-GlycineDocument6 pagesMSDS - Prominent-GlycineTanawat ChinchaivanichkitNo ratings yet