Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Adult Health and Relationship Outcomes Among Women With Abuse Experiences During Childhood

Adult Health and Relationship Outcomes Among Women With Abuse Experiences During Childhood

Uploaded by

Nurul ShahirahOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Adult Health and Relationship Outcomes Among Women With Abuse Experiences During Childhood

Adult Health and Relationship Outcomes Among Women With Abuse Experiences During Childhood

Uploaded by

Nurul ShahirahCopyright:

Available Formats

Violence and Victims, Volume 25, Number 3, 2010

Adult Health and Relationship

Outcomes Among Women With

Abuse Experiences During Childhood

Elizabeth A. Cannon, MS

Amy E. Bonomi, PhD, MPH

The Ohio State University

Melissa L. Anderson, MS

Group Health Cooperative

Frederick P. Rivara, MD, MPH

Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center and

the University of Washington

Robert S. Thompson, MD

Group Health Cooperative

Associations between child abuse and/or witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) during

childhood and womens health, adult IPV exposure, and health care use were examined.

Randomly sampled insured women ages 1864 (N = 3,568) completed a phone interview

assessing childhood exposure to abuse and witnessing IPV, current health, and adult IPV

exposure. Womens health care use was collected from automated health plan databases.

Poor health status, higher prevalence of depression and IPV, and greater use of health care

and mental health services were observed in women who had exposure to child abuse and

witnessing IPV during childhood or child abuse alone, compared with women with no

exposures. Women who had witnessed IPV without child abuse also had worse health and

greater use of health services. Findings reveal adverse long-term and incremental effects of

differing child abuse experiences on womens health and relationships.

Keywords: adult health; health care utilization; intimate partner violence; child abuse;

witnessing intimate partner violence

hild abuse history is prevalent among women (Arnow, 2004; Chartier, Walker, &

Naimark, 2007; Newman et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2006)

and is associated with poor health across the lifespan (Batten, Aslan, Maciejewski,

& Mazure, 2004; Bensley, Van Eenwyk, & Wynkoop Simmons, 2003; Carlson, McNutt,

& Choi, 2003; McCauley et al., 1997; Moeller, Bachmann, & Moeller, 1993; Nicolaidis,

Curry, McFarland, & Gerrity, 2004; Thurston et al., 2008; Walker et al., 1999). As well,

witnessing intimate partner violence (IPV) in childhooda stressful, adverse experience (Felitti et al., 1998)is associated with poor health well into adulthood (Dube,

2010 Springer Publishing Company

291

DOI: 10.1891/0886-6708.25.3.291

Article-01.indd 291

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

292

Cannon et al.

Anda, Felitti, Edwards, & Williamson, 2002). Studies suggest a doseresponse relationship between adverse childhood exposures (such as child abuse and witnessing IPV) and

poor self-rated health in adulthoodthe more traumatic exposures in childhood, the poorer

ones self-rated health in adulthood (Bensley et al., 2003; Dube, Felitti, Dong, Giles, &

Anda, 2003; Edwards, Holden, Felitti, & Anda, 2003; Felitti et al., 1998).

Studies have also shown an association between childhood abuse and adverse relationship outcomes in adulthood, including IPV victimization (Bensley et al., 2003; Coid et al.,

2001; Nicolaidis et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 2006; Whitfield, Anda, Dube, & Felitti,

2003). This relationship has also been shown for witnessing IPV during childhood and

IPV exposure in adulthood (Bensley et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2006; Whitfield et al.,

2003). Moreover, a graded relationship has been found between the number of child abuse

exposures and IPV (Bensley et al., 2003; Whitfield et al., 2003).

In addition, the extant literature points to higher health care use for women with exposure to childhood physical and sexual abuse (Anda, Brown, Felitti, Dube, & Giles, 2008;

Arnow, 2004; Arnow et al., 2000; Bonomi, Anderson, et al., 2008; Chartier et al., 2007;

Finestone et al., 2000; Newman et al., 2000; Tang et al., 2006). For example, one recent

study found that adverse childhood experiences (such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, and

witnessing IPV) were associated with increased prescription drug use (Anda et al., 2008).

In addition, the same study found a graded relationship between number of adverse childhood experiences and risk for number of classes of drugs used.

Although some studies have examined the individual and combined effects of child abuse

and witnessing IPV on adult health status, IPV exposure (i.e., Bensley et al., 2003) and adult

health care utilization, they have examined only a couple of outcomes, such as IPV victimization and self-reported overall health, and none to our knowledge have examined more than one

objective indicator of health care use by these exposures. In addition, prior studies did not conceptualize IPV as including physical, sexual, and nonphysical types of abuse (Bensley et al.,

2003)covering the range of abuse experiences acknowledged by key violence prevention

organizations such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Saltzman, 2004). The

present investigation examines a wide range of self-reported health and relationship outcomes

(i.e., IPV victimization in adulthood) and health care use (derived from automated health plan

data) associated with exposure to child abuse (physical and/or sexual) only, witnessing IPV

during childhood, or exposure to both child abuse and witnessing IPV during childhood using

data from women enrolled in a large health care delivery system.

Based on prior research that points to a doseresponse relationship between adverse

childhood experiences and self-rated health (e.g., Dube et al., 2003), IPV victimization

(e.g., Bensley et al., 2003), and health care utilization (Anda et al., 2008), we hypothesized that the most pronounced adverse health indicators (e.g., poor self-rated health, IPV

occurrence, and health care use) would be observed in women who had been exposed to

both child abuse and witnessing IPV during childhood compared with nonabused women.

However, we also expected increased rates of adverse health outcomes in women who had

one exposure only (e.g., witnessing IPV, child abuse) compared with nonabused women.

METHODS

Participants

The sample comprised 3,568 randomly sampled, English-speaking women aged 1864

enrolled for 3 years or longer at Group Health Cooperative between 1991 and 2001, who

Article-01.indd 292

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

293

participated in a telephone survey between December 2003 and August 2005 to assess

abuse exposure and health outcomes. Group Health provides health services to more than

550,000 mostly urban residents of Washington State and northern Idaho. Of 6,666 women

selected, 345 were excluded because they were found to be ineligible once they were contacted (209; e.g., they no longer belonged to Group Health Cooperative), deceased (3), too

ill (15), or had a language barrier or hearing impairment (118). Of the 6,321 remaining

women, 1,829 (28.9%) refused participation, 539 (8.5%) were located but did not complete

the interview, 385 (6.1%) could not be located, and 3,568 (56.4%) completed the survey.

The study was approved by Group Healths Institutional Review Board.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcomes were self-reported general health, physical, social, and mental functioning; depression and physical symptoms; and IPV experienced since age 18, as well as

health care utilization determined from automated databases to corroborate womens selfreports of health indicators. Health indicators were probed before abuse exposures in order

to reduce response bias due to the order of the questions.

General Health, Physical, Social, and Mental Functioning. Twenty questions from

the Short Form-36 (SF-36) Health Survey, version 2 were used to assess womens general

health, vitality, mental health, emotional functioning, and social functioning in the past 4

weeks (Ware, Kosinski, & Dewey, 2000). The Physical Component Summary (PCS) and

Mental Component Summary (MCS) scoresaggregate measures of physical and mental

functioningwere also determined using a subset of the 20 questions from each SF-36 area.

The SF-36 subscale scores and the PCS and MCS scores were standardized to have a mean

of 50 and standard deviation of 10, with higher scores indicating better functioning. These

standardized scores allowed for easy comparisons across subscales and clinical populations

(Ware et al., 2000). The general health item from the SF-36 was dichotomized (fair/poor

vs. good/very good/excellent health; Diehr & Patrick, 2003; Diehr, Patrick, McDonell, &

Fihn, 2003).

Depression. Women rated the frequency of depressive symptoms (0 = less than 1 day

per week to 3 = five or more days per week) using five questions from the Center for

Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale (Shrout & Yager, 1989). Scores for

each of the five items are summed; a score of four or greater (range: 015) indicates minor

depressive symptoms (Shrout & Yager, 1989), and a score of six or greater, severe depressive symptoms (Bonomi, Kernic, Anderson, Cannon, & Slesnick, 2008).

Physical Symptoms. Women indicated how bothered they were by 14 common physical

symptoms in the past 6 months (range: 1 = none of the time to 5 = all of the time; Robins,

Helzer, Croughan, & Ratcliff, 1981). The symptoms included joint pain, back pain, insomnia, fatigue, abdominal pain, severe headache, numb hands or feet, diarrhea, constipation,

shortness of breath, pain in jaw or ears, dizziness, nausea or vomiting, and chest pain. The

number of symptoms bothering respondents at least some of the time (a 3 on the 15

scale) was counted (Robins et al., 1981).

Health Care Utilization. We collected data on womens health care utilizationincluding any mental health, inpatient, outpatient, and emergency department visits; number of

visits to primary and specialty health care; and number of prescription fillsfrom January

1, 1992, to December 31, 2002, using Group Healths automated databases (Bonomi,

Anderson, et al., 2008; Rivara et al., 2007). Group Health databases precisely capture

health services provided by Group Health and other health care providers with whom

Group Health contracts (Boudreau, Doescher, Saver, Jackson, & Fishman, 2005).

Article-01.indd 293

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

294

Cannon et al.

Intimate Partner Violence. Women were asked about exposure to physical, sexual, or

nonphysical IPV by a heterosexual or homosexual partner since age 18. As previously

described (Bonomi, Cannon, Anderson, Rivara, & Thompson, 2008), two well-validated

questionnaires were used to assess IPV exposure: five questions from the Behavioral Risk

Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), which assessed exposure to physical, sexual, or

nonphysical abuse such as threats and chronic controlling behavior (Saltzman, Fanslow,

McMahon, & Shelley, 1999; Vest, Catlin, Chen, & Brownson, 2002); and 10 questions

from the Womens Experience with Battering Scale (WEB), which assessed the underlying

experience of fear and loss of power and control that may accompany exposure to abusive behavioral tactics (Smith, Earp, & DeVellis, 1995). Consistent with published scoring precedents, women who said they experienced any type of violence according to the

BRFSS questions or who had WEB scores that were 20 or higher (score range, 1060) were

considered positive for IPV (Bonomi et al., 2006; Thompson et al., 2006).

Child Abuse Exposures

Women were asked about their exposure to child physical abuse and child sexual abuse

using two questions from the BRFSS (Thompson et al., 2006). Women were also asked

whether they ever witnessed IPV between their parents or guardians and their spouses or

partners before age 18. For exact wording of these questions, see Table 1. Women who indicated they had experienced any of these abuse types were considered exposed to that

particular abuse type. From these questions, four exposure groups were constructed: (1) no

childhood exposures; (2) exposure to child abuse only; (3) witnessing IPV only; or (4) both

exposure to child abuse and witnessing IPV.

Statistical Analysis

Chi-square tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA) methods were used to compare the

demographic characteristics of women by child abuse exposure. Unadjusted means and

frequencies were estimated for each of the health indicators across abuse exposure groups.

For our multivariate analysis involving self-reported health outcomes: (1) generalized linear models with a log link were used to obtain prevalence ratios (PR) for each dichotomous

health outcome and for exposure to IPV in adulthood for exposed women compared with

unexposed women; and (2) ordinary least squares regression was used to estimate mean

TABLE 1.

Questions Assessing Childhood Exposure

Exposure

Question

Child physical abuse

Before you were 18, was there any time when you were

punched, kicked, choked, or received a more serious physical

punishment from a parent or other adult guardian?

Child sexual abuse

Before you were 18, did anyone ever touch you in a sexual

place or make you touch them when you did not want them

to?

Witness IPV as a child

As a child, did you ever see or hear one of your parents or

guardians being hit, slapped, punched, shoved, kicked, or

otherwise physically hurt by their spouse or partner?

Article-01.indd 294

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

295

differences in SF-36 subscale and PCS and MCS scores. The multivariate models compare

the health of women with child abuse only (physical and/or sexual), witnessing IPV as a

child only, or child abuse and witnessing IPV to the health of women without these histories (reference group).

To compare annual health care utilization across the exposure groups, we used generalized estimating equations (GEE) with robust standard error estimates assuming an independent working correlation to account for correlation between multiple years of annual

health care utilization from the same woman. For binary outcomes assessing any use

of health services, GEE models with a log link were used to estimate relative risks (RR).

For counts of health care utilization (primary and specialty care visits and pharmacy fills),

regression models were used to estimate incident rate ratios (IRR).

The multivariate models were controlled for age and education. While both education

and income differed by exposure group, we chose to adjust for education as a representative measure of socioeconomic status because education was most strongly associated with

exposure group, and because there were more missing values for the household income

measure. We did not adjust for race/ethnicity since for nonbiologic outcomes, race/ethnicity associations are often due to confounding by socioeconomic status, and because

our sample did not afford a wide racial/ethnic distribution (82% White). As a sensitivity

analysis, we refit all models adjusting for age, education, income, and race. The main study

results were unchanged; therefore, we report the results of the primary data analysis.

RESULTS

Characteristics of Women

Forty percent (n = 1,434/3,568) of women reported exposure to child abuse and/or witnessing IPV before age 18; 23% (802/3,568) were exposed to child abuse only, 7% (265/3,568)

witnessed IPV only, and 10% (367/3,568) had an exposure to abuse and witnessing IPV before age 18. Some significant group differences emerged between the exposure groups and

the no exposures group for age, income, education, and race, and are denoted in Table 2.

Women in the child abuse only group (Mean = 46.7 years) and the combined exposures

group (Mean = 46.3 years) were older than women in the no exposures group (Mean = 44.6

years). Women in the witness IPV only group were more likely to have a lower household

income and to be a high school graduate or less than the no exposures group. Furthermore,

women in both the witness IPV only group and the combined exposures group were less

likely to be White than women in the no exposures group.

Multivariate Models of Self-Reported Adult Health

by Childhood Abuse Exposure

Table 3 reports mean SF-36 scores and frequencies of the dichotomous health indicators (prevalence of fair/poor health, depressive symptoms, and social connectedness) by

child abuse exposure. After adjustment for age and education, women with exposure to

child abuse and/or witnessing IPV had significantly lower SF-36 subscale and summary

scores compared with unexposed women, with the most pronounced differences reported

between unexposed women and women with exposure to both child abuse and witnessing IPV. Specifically, women with both exposures had SF-36 subscale scores ranging

from 3.49 points lower (emotional functioning) to 4.12 points lower (mental health) than

Article-01.indd 295

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

296

TABLE 2.

Cannon et al.

Characteristics of Women at Time of Survey

No Childhood

Exposures

Childhood

Abuse Only

Witness

IPV Only

Childhood Abuse

and Witness IPV

N = 2,134

N = 802

N = 265

N = 367

46.7 (11.3)

44.7 (12.3)

46.3 (11.0)

Mean age at survey (SD) 44.6 (13.1)

Household income (%)

<$25,000

12.0

11.0

14.7

12.0

$25,000$49,999

26.5

29.3

33.3

26.0

$50,000$74,999

25.7

24.5

24.4

31.8

>$75,000

35.7

35.2

27.5

30.2

Employed at least part

time (%)

80.1

79.7

80.4

81.2

High school graduate

or less (%)

12.4

11.7

19.3

13.9

White (%)

83.3

84.1

74.6

76.3

Have children in the

home (%)

31.7

32.8

31.3

35.4

p < .05; comparison to no childhood exposure group.

p < .01; comparison to no childhood exposure group.

women with no childhood exposures. Moreover, women in the combined exposures group

had SF-36 summary scores ranging from 2.70 points lower (physical component) to 3.75

points lower (mental component) than women in the no exposure group. Women with

both exposures had 1.34 more symptoms and a higher body mass index (difference in

BMI = 1.94), and they were 1.76 times as likely to report fair/poor health, 1.96 times as

likely to report depressive symptoms, and 2.55 times as likely to report severe depressive

symptoms as women with neither exposure. Finally, women with both exposures were

1.55 times as likely to report that they did not trust people in their residential community.

In fact, for women in the combined exposures group, the only health indicator that was

not significantly different from women with no exposures was involvement in voluntary

groups.

The trends in the childhood abuse only group were similar to those in the combined

exposure group, but the point estimates were slightly attenuated. The estimates for these

two groups were not significantly different from each other, with the exception of the mean

number of symptoms reported by each group.

Women who witnessed IPV only during childhood had SF-36 subscale scores that were

lower than those for unexposed women (range: 1.90 points lower for mental health to 2.72

points lower for social functioning) and an MCS score that was, on average, 2.63 points

lower than women without either exposure. Furthermore, the witness IPV only group

reported 0.60 more symptoms and was 1.64 times as likely to report depressive symptoms

as the no exposures group.

Article-01.indd 296

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

Article-01.indd 297

49.3 (10.2)

49.5 (9.5)

2.79 (2.40)

51.0 (8.4)

51.3 (8.7)

51.9 (8.5)

2.03 (2.11)

26.9 (6.3)

Social functioning

Physical component

summary

Mental component

summary

Number of symptoms*

Body mass index (kg/m2)

28.2 (7.4)

47.9 (10.2)

50.2 (9.1)

53.0 (8.1)

Mental health

49.7 (10.0)

52.4 (8.8)

Vitality

48.3 (8.8)

Mean (SD)

Mean (SD)

50.5 (7.5)

Childhood

Abuse Only

(N = 802)

No Childhood

Exposures

(N = 2,134)

27.7 (6.5)

2.71 (2.57)

49.2 (9.8)

50.0 (10.0)

48.1 (9.9)

51.0 (8.9)

49.8 (9.7)

48.4 (8.5)

Mean (SD)

Witness

IPV Only

(N = 265)

29.1 (8.1)

3.43 (2.80)

48.2 (10.8)

48.4 (10.1)

46.9 (10.4)

48.9 (10.9)

48.5 (10.0)

47.1 (9.6)

Mean (SD)

Childhood

Abuse and

Witness IPV

(N = 367)

2.31 (2.97,

1.65)

2.66 (3.42,

1.91)

2.89 (3.60,

2.19)

3.00 (3.75,

2.26)

1.72 (2.46,

0.97)

2.59 (3.32,

1.85)

0.71 (0.53,

0.89)

1.06 (0.52,

1.62)

B (95% CI)

Childhood

Abuse Only vs.

No Childhood

Exposures

Child Abuse Exposures

Self-Reported Health and Adult Exposure to IPV by Child Abuse Exposures

SF-36 subscale scores

Role emotional

TABLE 3.

2.01 (3.05,

0.97)

2.41 (3.60,

1.22)

1.90 (3.01,

0.79)

2.72 (3.89,

1.55)

1.07 (2.24,

0.10)

2.63 (3.78,

1.47)

0.60 (0.31,

0.89)

0.61 (0.25,

1.47)

B (95% CI)

Witness IPV

Only vs. No

Childhood

Exposures

(Continued)

3.49 (4.39,

2.58)

3.79 (4.82,

2.76)

4.12 (5.09,

3.16)

3.98 (5.00,

2.96)

2.70 (3.72,

1.69)

3.75 (4.76,

2.75)

1.34 (1.09,

1.59)

1.94 (1.19,

2.68)

B (95% CI)

Childhood

Abuse and

Witness IPV vs.

No Childhood

Exposures

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

297

4/29/2010 2:40:56 PM

Article-01.indd 298

29.0

58.0

24.4

35.1

49.0

31.3

42.6

12.1

26.9

10.6

Witness

IPV Only

(N = 265)

67.3

36.5

43.6

21.0

31.1

13.1

Childhood

Abuse and

Witness IPV

(N = 367)

1.03 (0.91,

1.17)

1.26 (1.07,

1.47)

1.59 (1.42,

1.79)

1.55 (1.30,

1.85)

1.63 (1.28,

2.08)

1.37 (1.05,

1.80)

PR (95% CI)

Childhood

Abuse Only vs.

No Childhood

Exposures

Child Abuse Exposures

1.03 (0.84,

1.25)

1.24 (0.98,

1.56)

1.37 (1.13,

1.65)

1.64 (1.27,

2.12)

1.42 (0.97,

2.07)

1.39 (0.93,

2.08)

PR (95% CI)

Witness IPV

Only vs. No

Childhood

Exposures

1.08 (0.91,

1.28)

1.55 (1.28,

1.88)

1.84 (1.59,

2.12)

1.96 (1.58,

2.43)

2.55 (1.95,

3.34)

1.76 (1.27,

2.44)

PR (95% CI)

Childhood

Abuse and

Witness IPV vs.

No Childhood

Exposures

Note. Models adjusted for age and education.

*Symptoms included joint pain, back pain, insomnia, fatigue, abdominal pain, severe headache, numb hands or feet, diarrhea, constipation,

shortness of breath, pain in jaw or ears, dizziness, nausea or vomiting, and chest pain.

41.3

13.1

24.3

40.3

8.1

Severely depressed

Social connectedness

Not active in voluntary

groups

Do not trust people in

community

Exposure to IPV since

age 18

15.9

Depression, CES-D

Depressive symptoms

10.0

Childhood

Abuse Only

(N = 802)

No Childhood

Exposures

(N = 2,134)

7.0

(Continued)

General health

Fair/Poor

TABLE 3.

298

Cannon et al.

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

299

Prevalence of IPV by Child Abuse Exposure Group

Table 3 also reports lifetime adult IPV prevalence (since age 18) by child abuse exposures.

After adjusting for age and education, women who were exposed to both child abuse and

witnessing IPV were 1.84 times as likely to report IPV victimization in adulthood compared to women with no exposures. Women who had exposure to child abuse only were

1.59 times more likely to report adult IPV, and women who had witnessed IPV only were

1.37 times more likely to report adult IPV than women with neither exposure.

Adjusted Annual Health Care Utilization

Table 4 reports health services utilization by child abuse exposures. Women contributed

an average of 7.4 women-years to the analysis (range 111). In models adjusted for age,

education, and calendar year, women with exposure to child abuse with or without witnessing IPV utilized significantly more health services than women with no exposures.

Specifically, women with exposures to both child abuse and witnessing IPV had higher

health services use across 4 areas: mental health (RR = 1.84; 95% CI = 1.512.23); emergency department (RR = 1.77; 95% CI = 1.432.18); primary care (RR = 1.17; 95% CI =

1.091.25); and pharmacy fills (RR = 1.26; 95% CI = 1.131.41).

The estimated increase in health care utilization for women in the child abuse only group

was similar to the combined exposures group, with the point estimates slightly attenuated

for women with child abuse only. However, women with exposure to child abuse only had

significantly higher health services use than women with no exposures in two additional

areas that were not significant for the combined exposures group: hospital outpatient (RR

= 1.21; 95% CI = 1.061.38); and specialty care (RR = 1.18; 95% CI = 1.091.28).

The witnessing IPV only group used more health services than the no exposure group in

two areas: emergency department (RR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.101.85); and primary care (RR

= 1.09; 95% CI = 1.011.17).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first, to our knowledge, to examine the long-term effects of child abuse

and witnessing IPV before age 18 on multiple indicators of adult health status, substantiated by a range of objective health care utilization indicators, as well as the effects of these

adverse child abuse exposures on the relationship outcome of IPVusing a broad definition of IPV that includes physical, sexual, and nonphysical types of abuse. Results of this

study show clear, long-lasting, adverse health status, relationship, and health utilization

effects of child abuse exposure and witnessing IPV as a child.

In accordance with other studies (Dube et al., 2002) and as we had hypothesized, we did

find evidence for the effects of witnessing IPV only before age 18 on adult health status.

Though the differences for these women were fewer and less pronounced than for those

who had exposure to child abuse (in either the child abuse only or combined groups), it

is important to note that merely witnessing IPV during childhood can have adverse health

outcomes well into adulthood.

As we had predicted, childhood abuse (with or without exposure to witnessing IPV) was

associated with lower self-rated health in adulthood on multiple indicators. Other studies

have documented the adult health effects of child physical and/or sexual abuse experienced

before age 18 (Batten et al., 2004; Bensley et al., 2003; Bonomi, Cannon, et al., 2008;

Article-01.indd 299

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Article-01.indd 300

11.7 (15.0)

Pharmacy (no. of fills)

14.8 (18.8)

1.7 (3.0)

3.5 (3.4)

Mean (SD)

5.2

10.3

5.0

14.3

7.35 (3.69)

5,690

774

Childhood

Abuse Only

12.3 (14.6)

1.4 (2.6)

3.3 (3.0)

Mean (SD)

5.9

9.6

5.5

7.5

7.38 (3.67)

1,830

248

Witness

IPV Only

Note. Models adjusted for age, education, and calendar year.

1.4 (2.6)

4.0

ED

Specialty care (no. of

visits)

8.6

Hospital outpatient

2.9 (2.8)

4.7

Inpatient

Primary care (no. of

visits)

8.2

Mental health services

Mean (SD)

Any service utilization

Ambulatory services

7.43 (3.74)

14,532

Number of women-years

Follow-up time, mean

(SD)

1,957

Number of women

No

Childhood

Exposures

15.4 (18.7)

1.5 (2.6)

3.5 (3.2)

Mean (SD)

7.1

9.8

5.6

15.0

7.42 (3.62)

2,626

354

Childhood

Abuse and

Witness IPV

1.22 (1.12, 1.34)

1.18 (1.09, 1.28)

1.16 (1.10, 1.23)

IRR (95% CI)

1.32 (1.11, 1.57)

1.21 (1.06, 1.38)

1.08 (0.92, 1.26)

1.73 (1.48, 2.03)

RR (95% CI)

Childhood

Abuse Only vs.

No Childhood

Exposures

Child Abuse Exposures

TABLE 4. Adjusted Health Services Utilization by Child Abuse Exposures

1.01 (0.89, 1.15)

0.96 (0.84, 1.09)

1.09 (1.01, 1.17)

IRR (95% CI)

1.42 (1.10, 1.85)

1.11 (0.91, 1.37)

1.11 (0.84, 1.47)

0.93 (0.70, 1.24)

RR (95% CI)

Witness IPV

Only vs. No

Childhood

Exposures

1.26 (1.13, 1.41)

1.00 (0.95, 1.11)

1.17 (1.09, 1.25)

IRR (95% CI)

1.77 (1.43, 2.18)

1.14 (0.96, 1.36)

1.15 (0.94, 1.41)

1.84 (1.51, 2.23)

RR (95% CI)

Childhood Abuse

and Witness IPV

vs. No Childhood

Exposures

300

Cannon et al.

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

301

Carlson et al., 2003; McCauley et al., 1997; Moeller et al., 1993; Nicolaidis et al., 2004;

Walker et al., 1999). While not significantly different from the child abuse only group,

the most pronounced differences in health status in our study were seen for women who

had exposure to both child abuse and witnessing IPV before age 18a finding in support

of both our hypothesis and of the graded association between multiple adverse events in

childhood and poor adult health (Bensley et al., 2003; Bonomi, Anderson, et al., 2008;

Bonomi, Cannon, et al., 2008; Dong, Anda, Dube, Giles, & Felitti, 2003; Dube et al., 2003;

Edwards et al., 2003; Felitti et al., 1998). Irving and Ferraro (2006) suggest that the detrimental health effects of multiple types of childhood abuse exposures accrue over time, thus

leading to poorer adult health than if exposed to only one adverse childhood experience

(Irving & Ferraro, 2006). Other researchers suggest that the amplified health effects that

result from multiple adverse childhood experiences are due to the exposure of the developing brain to the stress response, which thus impairs multiple brain structures and functions

(Bremner, 2003).

Two more recent studies found that childhood maltreatment experiences can exert powerful influences even on perceptions of well-being in adulthood. Namely, Edwards, Anda,

Felitti, and Shanta (2004) found that traumatic experiences during childhood affected adult

perceptions of health-related quality of life decades later. Corso, Edwards, Fang, and Mercy

(2008) found the same, but moreover, they reported that losses in health-related quality of

life were sustained; adults in their study who self-reported any form of childhood maltreatment had an average loss of 0.03 quality adjusted life years, or a loss of 11 days over

their remaining life expectancy.

Like other studies (Bensley et al., 2003; Thompson et al., 2006; Whitfield et al., 2003),

we found that women who had witnessed IPV only during childhood were more likely to

report adult IPV victimization than women with no abuse exposures. Also in support of

prior research, women with exposure to childhood abuse only also were more likely to

report IPV victimization (Bensley et al., 2003; Coid et al., 2001; Nicolaidis et al., 2004;

Thompson et al., 2006; Whitfield et al., 2003). Though we found similar health effects

across the exposure groups compared with nonabused women, women with both exposures

had the largest increased risk of adult IPV victimizationa finding that corroborates prior

research (Bensley et al., 2003; Whitfield et al., 2003).

Finally, concurrent with the extant literature (Chartier et al., 2007; Tang et al., 2006), we

found that women who had experienced child abuse had higher rates of health care utilization. To our knowledge, we are the first to report that women who had witnessed IPV during childhood (without the presence of child abuse) used more emergency department and

primary care services than women with no abuse exposure. As for women who experienced

both child abuse and witnessing IPV, we found that they also had higher rates of health care

utilization, a finding that supports existing research (Anda et al., 2008). However, we did

not find the most pronounced service use in women with both exposures, a finding that runs

contrary to the graded relationship that Anda et al. (2008) found between the number of

adverse childhood experiences and risk for number of classes of drugs used.

This study was not without limitations. First, our child abuse measurement approach

was limited. Specifically, we relied on self-reports of abuse and witnessing IPV before

age 18reliance on retrospective reports may lead to conservative findings because of

nondisclosed abuse (Widom, DuMont, & Czaja, 2007). However, self-reported abuse is an

extremely common method for gathering abuse exposure information. Moreover, because

our primary study was focused on IPV exposure after age 18, we did not ask about the full

range of child maltreatment (e.g., neglect, verbal abuse), nor the severity or frequency of

Article-01.indd 301

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

302

Cannon et al.

the abuse types we investigated; it is therefore unclear to what extent or with what regularity women suffered physical and sexual abuse, as well as other types of abuse. Limitations

in our child abuse measurement approach preclude seamless comparison with other studies

whose assessment was more comprehensive (e.g., Felitti et al., 1998). In addition to child

abuse measurement limitations, study generalizability may be limited by the prevailing

characteristics of the sample; the sample was mostly employed, highly educated, White,

and entirely insured. Furthermore, combining childhood physical and sexual abuse into one

analytic group results in a loss of specificity, as the two types of abuse have been shown

to have differing impacts on health and health utilization (e.g., Bonomi, Anderson, et al.,

2008; Bonomi, Cannon, et al., 2008). However, the results of the current article can be

interpreted with the knowledge of these previous reports of health effects by child abuse

type. Lastly, our response rate was relatively low, but a propensity score analysis showed

that women with and without abuse histories were equally likely to participate in the telephone survey (Bonomi, Cannon, et al., 2008; Rivara et al., 2007).

Notwithstanding these limitations, the results of this study have important primary

and secondary prevention implications. Primary prevention efforts within the health care

system to provide support to parents with young children (including prenatal home visits; education about healthy discipline strategies; and skill building in problem solving,

anger management, communication, and relationships with adults) can significantly improve parenting skills, reduce parenting stress, improve the parental relationship, and

thus reduce the risk of child abuse and/or witnessing IPV and ensuing consequences, not

only for childrens adult health status, health care utilization, and social functioning but

also for the health of their relationships (Huebner, 2002; Johnston, Huebner, Anderson,

Tyll, & Thompson, 2006; Olds et al., 1997). Furthermore, screening adults within the

health care setting for child abuse exposures as part of a risk assessment for IPV may

help to primarily prevent negative relationship outcomes (Whitfield et al., 2003). Lastly,

screening adults for child abuse exposures and implementing subsequent individual and

group psychotherapeutic interventions can be an integral part of secondary prevention

of long-term health effects of adverse childhood experiences. Indeed, such interventions

have been shown to improve mental health, curb symptomalogy, and improve the quality

of life of adults with child abuse exposures (Kessler, White, & Nelson, 2003; Martsolf

& Draucker, 2005).

REFERENCES

Anda, R. F., Brown, D. W., Felitti, V. J., Dube, S. R., & Giles, W. H. (2008). Adverse childhood

experiences and prescription drug use in a cohort study of adult HMO patients. BMC Public

Health, 8, 198.

Arnow, B. A. (2004). Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric

outcomes, and medical utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(Suppl. 12), 1015.

Arnow, B. A., Hart, S., Scott, C., Dea, R., OConnell, L., & Taylor, C. B. (2000). Childhood sexual

abuse, psychological distress, and medical use among women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(6),

762770.

Batten, S. V., Aslan, M., Maciejewski, P. K., & Mazure, C. M. (2004). Childhood maltreatment as

a risk factor for adult cardiovascular disease and depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry,

65(2), 249254.

Bensley, L., Van Eenwyk, J., & Wynkoop Simmons, K. (2003). Childhood family violence history

and womens risk for intimate partner violence and poor health. American Journal of Preventive

Medicine, 25, 3844.

Article-01.indd 302

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

303

Bonomi, A. E., Anderson, M. L., Rivara, F. P., Cannon, E. A., Fishman, P. A., Carrell, D., et al.

(2008). Health care utilization and costs associated with child abuse. Journal of General Internal

Medicine, 23(3), 294299.

Bonomi, A. E., Cannon, E. A., Anderson, M. L., Rivara, F. P., & Thompson, R. S. (2008). Association

between self-reported health and physical and/or sexual abuse experienced before age 18. Child

Abuse & Neglect, 32(7), 693701.

Bonomi, A. E., Kernic, M. A., Anderson, M. L., Cannon, E. A., & Slesnick, N. (2008). Use of brief

tools to measure depressive symptoms in women with a history of intimate partner violence.

Nursing Research, 57(3), 150156.

Bonomi, A. E., Thompson, R. S., Anderson, M. L., Reid, R. J., Carrell, D., Dimer, J. A., et al. (2006).

Intimate partner violence and womens physical, mental, and social functioning. American

Journal of Preventive Medicine, 30, 458466.

Boudreau, D. M., Doescher, M. P., Saver, B. G., Jackson, J. E., & Fishman, P. A. (2005).

Reliability of Group Health Cooperative automated pharmacy data by drug benefit status.

Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety, 14(12), 877884.

Bremner, J. D. (2003). Long-term effects of childhood abuse on brain and neurobiology. Child and

Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 12(2), 271292.

Carlson, B. E., McNutt, L., & Choi, D. Y. (2003). Childhood and adult abuse among women in primary health care: Effects on mental health. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(8), 924941.

Chartier, M. J., Walker, J. R., & Naimark, B. (2007). Childhood abuse, adult health, and health care utilization: Results from a representative community sample. American Journal of Epidemiology,

165(9), 10311038.

Coid, J., Petnuckevitch, A., Feder, G., Chung, W. S., Richardson, J., & Moorey, S. (2001). Relation

between childhood sexual and physical abuse and risk of revictimization in women: A crosssectional survey. Lancet, 358, 450454.

Corso, P. S., Edwards, V. J., Fang, X., & Mercy, J. A. (2008). Health-related quality of life among

adults who experienced maltreatment during childhood. American Journal of Public Health,

98(6), 1094100.

Diehr, P., & Patrick, D. L. (2003). Trajectories of health for older adults over time: Accounting fully

for death. Annals of Internal Medicine, 139, 416420.

Diehr, P., Patrick, D. L., McDonell, M. B., & Fihn, S. D. (2003). Accounting for deaths in longitudinal studies using the SF-36: The performance of the Physical Component Scale of the Short

Form 36-item health survey and the PCTD. Medical Care, 41, 10651073.

Dong, M., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., Giles, W. H., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). The relationship of exposure

to childhood sexual abuse to other forms of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction during

childhood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 27(6), 625639.

Dube, S. R., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Edwards, V. J., & Williamson, D. F. (2002). Exposure to abuse,

neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as

children: Implications for health and social services. Violence and Victims, 17(1), 318.

Dube, S. R., Felitti, V. J., Dong, M., Giles, W. H., & Anda, R. F. (2003). The impact of adverse childhood experiences on health problems: Evidence from four birth cohorts dating back to 1900.

Preventive Medicine, 37(3), 268277.

Edwards, V. J., Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., & Shanta, R. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and

health-related quality of life as an adult. In K. A. Kendall-Tackett (Ed.), Health consequences of

abuse in the family: A clinical guide for evidence-based practice (pp. 8194). Washington, DC:

American Psychological Association.

Edwards, V. J., Holden, G. W., Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2003). Relationship between multiple forms

of childhood maltreatment and adult mental health in community respondents: Results from the

adverse childhood experiences study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(8), 14531460.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., et al. (1998).

Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes

of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of

Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245258.

Article-01.indd 303

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

304

Cannon et al.

Finestone, H. M., Stenn, P., Davies, F., Stalker, C., Fry, R., & Koumanis, J. (2000). Chronic pain

and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse &

Neglect, 24(4), 547556.

Huebner, C. E. (2002). Evaluation of a parent education program to reduce the risk of infant and toddler maltreatment. Public Health Nursing, 19(5), 377389.

Irving, S. M., & Ferraro, K. F. (2006). Reports of abusive experiences during childhood and adult

health ratings: Personal control as a pathway? Journal of Aging and Health, 18(3), 458485.

Johnston, B. D., Huebner, C. E., Anderson, M. L., Tyll, L. T., & Thompson, R. S. (2006). Healthy

steps in an integrated delivery system: Child and parent outcomes at 30 months. Archives of

Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 160, 793800.

Kessler, M. R., White, M. B., & Nelson, B. S. (2003). Group treatments for women sexually abused

as children: A review of the literature and recommendations for future outcome research. Child

Abuse & Neglect, 27(9), 10451061.

Martsolf, D. S., & Draucker, C. B. (2005). Psychotherapy approaches for adult survivors of childhood

sexual abuse: An integrative review of outcomes research. Issues in Mental Health Nursing,

26(8), 801825.

McCauley, J., Kern, D. E., Kolodner, K., Dill, L., Schroeder, A. F., DeChant, H. K., et al. (1997).

Clinical characteristics of women with a history of childhood abuse: Unhealed wounds. Journal

of the American Medical Association, 277(17), 13621368.

Moeller, T. P., Bachmann, G. A., & Moeller, J. R. (1993). The combined effects of physical, sexual,

and emotional abuse during childhood: Long-term health consequences for women. Child Abuse

& Neglect, 17, 623640.

Newman, M. G., Clayton, L., Zuellig, A., Cashman, L., Arnow, B., Dea, R., et al. (2000). The relationship of childhood sexual abuse and depression with somatic symptoms and medical utilization. Psychological Medicine, 30, 10631077.

Nicolaidis, C., Curry, M., McFarland, B., & Gerrity, M. (2004). Violence, mental health, and physical symptoms in an academic internal medicine practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine,

19, 819827.

Olds, D. L., Eckenrode, J., Henderson, C. R., Jr., Kitzman, H., Powers, J., Cole, R., et al. (1997). Longterm effects of home visitation on maternal life course and child abuse and neglect: Fifteen-year

follow-up of a randomized trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278(8), 680681.

Rivara, F. P., Anderson, M. L., Fishman, P., Bonomi, A. E., Reid, R. J., Carrell, D., et al. (2007).

Healthcare utilization and costs for women with a history of intimate partner violence. American

Journal of Preventive Medicine, 32(2), 8996.

Robins, L. N., Helzer, J. E., Croughan, J., & Ratcliff, K. S. (1981). National Institute of Mental

Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Archives of

General Psychiatry, 38, 381389.

Saltzman, L. E. (2004). Issues related to defining and measuring violence against women: Response

to Kilpatrick. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(11), 12351243.

Saltzman, L. E., Fanslow, J. L., McMahon, P., & Shelley, G. A. (1999). Intimate partner violence

surveillance: Uniform definitions and recommended data elements (Version 1.0). Atlanta, GA:

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Shrout, P. E., & Yager, T. J. (1989). Reliability and validity of screening scales: Effect of reducing

scale length. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 42, 6978.

Smith, P. H., Earp, J. A., & DeVellis, R. (1995). Measuring battering: Development of the Womens

Experience with Battering (WEB) scale. Womens Health, 1, 273288.

Tang, B., Jamieson, E., Boyle, M., Libby, A., Gafni, A., & MacMillan, H. (2006). The influence of

child abuse on the pattern of expenditures in womens adult health service utilization in Ontario,

Canada. Social Science & Medicine, 63(7), 17111719.

Thompson, R. S., Bonomi, A. E., Anderson, M., Reid, R. J., Dimer, J. A., Carrell, D., et al. (2006).

Intimate partner violence: Prevalence, types, and chronicity in adult women. American Journal

of Preventive Medicine, 30, 447457.

Article-01.indd 304

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Health and Relationship Outcomes of Childhood Abuse

305

Thurston, R. C., Bromberger, J., Chang, Y., Goldbacher, E., Brown, C., Cyranowski, J. M., et al.

(2008). Childhood abuse or neglect is associated with increased vasomotor symptom reporting

among midlife women. Menopause, 15(1), 1622.

Vest, J. R., Catlin, T. K., Chen, J. J., & Brownson, R. C. (2002). Multistate analysis of factors associated with intimate partner violence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 22, 156164.

Walker, E. A., Unutzer, J., Rutter, C., Gelfand, A., Saunders, K., VonKorff, M., et al. (1999). Costs

of health care use by women HMO members with a history of childhood abuse and neglect.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 56(7), 609613.

Ware, J. E., Kosinski, M., & Dewey, J. E. (2000). How to score version two of the SF-36 health survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric Inc.

Whitfield, C. L., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). Violent childhood experiences and

the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166185.

Widom, C. S., DuMont, K., & Czaja, S. J. (2007). A prospective investigation of major depressive disorder and comorbidity in abused and neglected children grown up. Archives of General

Psychiatry, 64(1), 4956.

Acknowledgments. This manuscript was developed with support from the Agency for Healthcare

Research and Quality and the Group Health Foundation. The authors thank the study interviewers for

interviewing thousands of women.

Correspondence regarding this article should be directed to Amy E. Bonomi, PhD, MPH, Human

Development and Family Science, The Ohio State University, 135 Campbell Hall, 1787 Neil Ave.,

Columbus, OH 43210. E-mail: bonomi.1@osu.edu

Article-01.indd 305

4/29/2010 2:40:57 PM

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Aces EssayDocument10 pagesAces Essayapi-549331512No ratings yet

- Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesHealth Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Systematic ReviewCocia Podina Ioana RoxanaNo ratings yet

- Artigo Apa PDFDocument40 pagesArtigo Apa PDFErnângela CoelhoNo ratings yet

- The in Uence of Child Abuse On The Pattern of Expenditures in Women's Adult Health Service Utilization in Ontario, CanadaDocument9 pagesThe in Uence of Child Abuse On The Pattern of Expenditures in Women's Adult Health Service Utilization in Ontario, CanadaPriss SaezNo ratings yet

- 2014 Baglivio Et Al. The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in The Lives of Juvenile OffendersDocument23 pages2014 Baglivio Et Al. The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) in The Lives of Juvenile OffenderskakonautaNo ratings yet

- Adverse Childhood Experiences and Coping Strategies: Identifying Pathways To Resiliency in AdulthoodDocument17 pagesAdverse Childhood Experiences and Coping Strategies: Identifying Pathways To Resiliency in AdulthoodAndreea PalNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Associations Among Peer Victimization andDocument10 pagesLongitudinal Associations Among Peer Victimization andCristiana ComanNo ratings yet

- Gift 935 AsignmentDocument11 pagesGift 935 Asignmenttaizya cNo ratings yet

- Childhood Attachment and Abuse Long-Term Effects On Adult Attachment Depression and Conflict ResolutionDocument15 pagesChildhood Attachment and Abuse Long-Term Effects On Adult Attachment Depression and Conflict Resolutionolgabelei_675822878No ratings yet

- Palmisano 2016Document21 pagesPalmisano 2016RavennaNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & Neglect: David Finkelhor, Anne Shattuck, Heather Turner, Sherry HambyDocument9 pagesChild Abuse & Neglect: David Finkelhor, Anne Shattuck, Heather Turner, Sherry HambyMaría Pía UlloaNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse NeglectDocument12 pagesChild Abuse NeglectKii IwanaNo ratings yet

- Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Systematic ReviewDocument9 pagesHealth Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Systematic Reviewana raquelNo ratings yet

- Child Maltreatment, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and The Public Health Approach: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument31 pagesChild Maltreatment, Adverse Childhood Experiences, and The Public Health Approach: A Systematic Literature ReviewRebecca GlennyNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Sexual Behavior Patterns Mental Health and Early Life Adversities in A British Birth CohortDocument13 pagesAdolescent Sexual Behavior Patterns Mental Health and Early Life Adversities in A British Birth CohortHanya AhsanNo ratings yet

- Synopsis - NEW Project Psychology NEW (F)Document21 pagesSynopsis - NEW Project Psychology NEW (F)Ankita TyagiNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Parenting Styles and Adult Mental HealthDocument13 pagesRelationship Between Parenting Styles and Adult Mental HealthLindsey ClausenNo ratings yet

- Cara Membuat IDM Menjadi PermanenDocument12 pagesCara Membuat IDM Menjadi Permanenalifia maharaniNo ratings yet

- Body Mass Index and Anxiety/depression As Mediators of Theeffects of Child Sexual and Physical Abuse On Physical Healthdisorders in WomenDocument14 pagesBody Mass Index and Anxiety/depression As Mediators of Theeffects of Child Sexual and Physical Abuse On Physical Healthdisorders in WomenBadger6No ratings yet

- Growing Up With Parental Alcohol Abuse, Exposure To Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household DysfunctionDocument14 pagesGrowing Up With Parental Alcohol Abuse, Exposure To Childhood Abuse, Neglect, and Household DysfunctionAndreea PalNo ratings yet

- Zinatniskais Raksts Par VardarbibuDocument9 pagesZinatniskais Raksts Par VardarbibuAnnija Vecuma-VecoNo ratings yet

- Violence Against Pregnant Women Can Increase The Risk of Child Abuse A Longitudinal StudyDocument29 pagesViolence Against Pregnant Women Can Increase The Risk of Child Abuse A Longitudinal StudyLangkah PercobaanNo ratings yet

- Helen Gavin Sticks and Stones, Effects of Childhood Emotional Abuse in AdulthoodDocument43 pagesHelen Gavin Sticks and Stones, Effects of Childhood Emotional Abuse in AdulthoodSuzieWylieNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0005796711001306 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0005796711001306 MainMaria CoelhoNo ratings yet

- Child Abuse & NeglectDocument20 pagesChild Abuse & Neglectrosan quimcoNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Adult Attachment Ratings and Health ConditionsDocument8 pagesAssociations Between Adult Attachment Ratings and Health ConditionsAzzurra AntonelliNo ratings yet

- Paper 8Document19 pagesPaper 8DrAqeel AshrafNo ratings yet

- Artigo SobreDocument16 pagesArtigo SobreMarina HeinenNo ratings yet

- NJAfZMJDyIBlJlQTexto Clase 9. Antenatal Depression. Olhaberry Et Al, 2014.Document12 pagesNJAfZMJDyIBlJlQTexto Clase 9. Antenatal Depression. Olhaberry Et Al, 2014.Andrea RamírezNo ratings yet

- Pelecehan Terhadap AnakDocument7 pagesPelecehan Terhadap Anakratna puspitasariNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument19 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptMaríaA.SerranoNo ratings yet

- Brunton y Dryer (2022)Document10 pagesBrunton y Dryer (2022)Angela Matito QuesadaNo ratings yet

- Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access JournalDocument20 pagesHealth Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access JournalViviana PueblaNo ratings yet

- Somatic Symptoms Among US Adolescent FemalesDocument10 pagesSomatic Symptoms Among US Adolescent Femalesvgaravito35No ratings yet

- Child Abuse Research Paper - Draft 20191020 PDFDocument5 pagesChild Abuse Research Paper - Draft 20191020 PDFJerry EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Domestic ViolenceDocument19 pagesDomestic ViolenceGustavo Enrique Tovar RamosNo ratings yet

- SSM - Population Health: ArticleDocument10 pagesSSM - Population Health: ArticlemahsusiyatiNo ratings yet

- WHB - Volume 2 - Issue 3 - Pages 1-5Document5 pagesWHB - Volume 2 - Issue 3 - Pages 1-5Logic MagicNo ratings yet

- Long Term Effects of Child Sexual AbuseDocument32 pagesLong Term Effects of Child Sexual AbuseKimberly Parton Bolin100% (2)

- ACE Finished - Docx1234Document10 pagesACE Finished - Docx1234Nadia umwaliNo ratings yet

- Promoting Physical Activity in Preschoolers To Prevent Obesity: A Review of The LiteratureDocument17 pagesPromoting Physical Activity in Preschoolers To Prevent Obesity: A Review of The LiteratureSufi IndrainiNo ratings yet

- Sosiology AnzaityDocument8 pagesSosiology AnzaityHelmi RaisNo ratings yet

- Gabalcand TerziogluDocument11 pagesGabalcand TerziogluElla B. CollantesNo ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: Janet U. Schneiderman, Jordan P. Davis, Sonya NegriffDocument9 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: Janet U. Schneiderman, Jordan P. Davis, Sonya NegriffNadia Cenat CenutNo ratings yet

- CTQ To Aces Preprint 20221107 PDFDocument21 pagesCTQ To Aces Preprint 20221107 PDFTuấn KhangNo ratings yet

- Zebhauser Et Al-2014-International Journal of Geriatric PsychiatryDocument8 pagesZebhauser Et Al-2014-International Journal of Geriatric PsychiatryastrogliaNo ratings yet

- Peer Victimization PaperDocument21 pagesPeer Victimization Paperapi-249176612No ratings yet

- PSIHOLOGIEDocument15 pagesPSIHOLOGIEMihaela IftodeNo ratings yet

- Research Methods - Final Research ProposalDocument10 pagesResearch Methods - Final Research Proposalapi-583124304No ratings yet

- Physical Health and DelinquencyDocument28 pagesPhysical Health and DelinquencyMARIFE LUCIANA COSAVALENTE VILLARNo ratings yet

- Adverse Childhood Experiences and Repeat Induced Abortion: General GynecologyDocument6 pagesAdverse Childhood Experiences and Repeat Induced Abortion: General Gynecologychie_8866No ratings yet

- Children and Youth Services Review: A B A C D ADocument9 pagesChildren and Youth Services Review: A B A C D ARiski NovitaNo ratings yet

- Adverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma-Informed CareDocument11 pagesAdverse Childhood Experiences and Trauma-Informed CaremittagbellaNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse by Gender of VictimDocument9 pagesLong-Term Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse by Gender of VictimMalyasree BasuNo ratings yet

- Sexual Dysfunction Among Women With Diabetes in A Primary Health Care at Semarang, Central Java Province, IndonesiaDocument8 pagesSexual Dysfunction Among Women With Diabetes in A Primary Health Care at Semarang, Central Java Province, IndonesiaTantonio Tri PutraNo ratings yet

- Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal Risk of Physical Impairment in A Cohort of Postmenopausal Women Who Experience Physical and Verbal AbuseDocument11 pagesCross-Sectional and Longitudinal Risk of Physical Impairment in A Cohort of Postmenopausal Women Who Experience Physical and Verbal AbuseJuliana Sol RabagoNo ratings yet

- Safari - 16 Aug 2019 18.28Document1 pageSafari - 16 Aug 2019 18.28Yoan Caroline Saron KapressyNo ratings yet

- Psychological Consequences of Sexual TraumaDocument11 pagesPsychological Consequences of Sexual Traumamary engNo ratings yet

- Behavioral and Psychological Assessment of Child Sexual Abuse in Clinical PracticeDocument12 pagesBehavioral and Psychological Assessment of Child Sexual Abuse in Clinical PracticeCzarina Mae Quinones TadeoNo ratings yet

- Validation and Psychometric Evaluation of A 5-Item Measure of Perceived Social SupportDocument1 pageValidation and Psychometric Evaluation of A 5-Item Measure of Perceived Social SupportNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Q o LDocument5 pagesQ o LNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Working With MARGINALISED Communities:: Professional Practice in ActionDocument24 pagesWorking With MARGINALISED Communities:: Professional Practice in ActionNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Help Patients Understand: Manual For CliniciansDocument62 pagesHelp Patients Understand: Manual For CliniciansNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Supervision Standards 2013Document36 pagesSupervision Standards 2013Nurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Competence in Health and Mental Health: SSS 3084 Professional DevelopmentDocument35 pagesCompetence in Health and Mental Health: SSS 3084 Professional DevelopmentNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Maternal Health - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument13 pagesMaternal Health - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Malaysian Primary Care Doctors ' Views On Men's Health: An Unresolved Jigsaw PuzzleDocument10 pagesMalaysian Primary Care Doctors ' Views On Men's Health: An Unresolved Jigsaw PuzzleNurul ShahirahNo ratings yet

- Forming Real Estate SyndicatesDocument252 pagesForming Real Estate SyndicatesRamani Krishnamoorthy100% (2)

- 3WC COMSOC1 Course OutlineDocument2 pages3WC COMSOC1 Course OutlineDannyNo ratings yet

- Article Review Individual AssignmentDocument6 pagesArticle Review Individual AssignmentTong0% (1)

- 2018 AGAM06-18 Processes Defining and Understanding Asset Requirements PDFDocument72 pages2018 AGAM06-18 Processes Defining and Understanding Asset Requirements PDFVictor Lubambo Peixoto AcciolyNo ratings yet

- The Role of Microbiology in The Design and Development of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing ProcessesDocument4 pagesThe Role of Microbiology in The Design and Development of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing ProcessesHari RamNo ratings yet

- E-Cosh Manual 073020Document154 pagesE-Cosh Manual 073020Evaresto Cole MalonesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 AuditDocument62 pagesChapter 5 Auditmaryumarshad2No ratings yet

- Insurance Manual Ver 1Document82 pagesInsurance Manual Ver 1api-3743824No ratings yet

- Belison CDRA ReportDocument193 pagesBelison CDRA ReportTherese Mae MadroneroNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Capital Adequacy Ratio of Commercial Banks in NepalDocument48 pagesDeterminants of Capital Adequacy Ratio of Commercial Banks in NepalSabinaNo ratings yet

- Samara University College of Business and Economics: Department of Management EntrepreneurshipDocument54 pagesSamara University College of Business and Economics: Department of Management Entrepreneurshipfentaw melkie100% (1)

- GRI 3 Material Topics 2021Document30 pagesGRI 3 Material Topics 2021chidu chiduNo ratings yet

- Operations & Training Risk Management Plan: ObjectiveDocument3 pagesOperations & Training Risk Management Plan: ObjectiveSagar JadhavNo ratings yet

- The Technical Basis Forthe NRC's Guidelines Forexternal Risk CommunicationDocument112 pagesThe Technical Basis Forthe NRC's Guidelines Forexternal Risk CommunicationEnformableNo ratings yet

- SI Maturity ClaimDocument4 pagesSI Maturity Claimmanishclass01 01No ratings yet

- Credit and Recover Management in HDFCDocument65 pagesCredit and Recover Management in HDFCAarthi SinghNo ratings yet

- Job Safety Analysis and Risk AssessmentDocument12 pagesJob Safety Analysis and Risk Assessmentsayuj karuvathil100% (1)

- Bird Strike Risk and Avoidance PDFDocument2 pagesBird Strike Risk and Avoidance PDFRémi WatineNo ratings yet

- Batch2 - Shruti SharmaDocument22 pagesBatch2 - Shruti Sharmashivendra singhNo ratings yet

- RMS (40931) Final Exam PaperDocument5 pagesRMS (40931) Final Exam PaperAbdurehman Ullah khanNo ratings yet

- IDFC FIRST Bank AnnualReport 2022 23Document316 pagesIDFC FIRST Bank AnnualReport 2022 23Anuja GupteNo ratings yet

- Free PMP Exam Questions Answers 2022Document56 pagesFree PMP Exam Questions Answers 2022PradeepNo ratings yet

- 7.GARP Code of ConductDocument2 pages7.GARP Code of ConductImran ShikdarNo ratings yet

- CH 4-1 To 4-4 Risk Metrics PDFDocument31 pagesCH 4-1 To 4-4 Risk Metrics PDFSoniaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Attitude and Practice of Occupational Safety Among Health Workers in Tertiary Hospital Mogadishu-SomaliaDocument6 pagesKnowledge Attitude and Practice of Occupational Safety Among Health Workers in Tertiary Hospital Mogadishu-Somalialimap5No ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - PowerPoint - In-ClassDocument36 pagesChapter 3 - PowerPoint - In-ClassNick HaldenNo ratings yet

- Blockaura Token 3.1: Serial No. 2022100500012015 Presented by Fairyproof October 5, 2022Document17 pagesBlockaura Token 3.1: Serial No. 2022100500012015 Presented by Fairyproof October 5, 2022shrihari pravinNo ratings yet

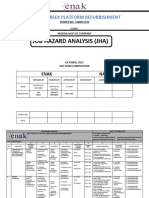

- Jha For Clough Creek Platform RefurbishmentDocument11 pagesJha For Clough Creek Platform RefurbishmentTheophilus OrupaboNo ratings yet

- Intro To Data EthicsDocument63 pagesIntro To Data EthicsRishabh BatraNo ratings yet

- Education Sector AnalysisDocument416 pagesEducation Sector AnalysisYisehaq Abraham100% (1)