Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TEST

TEST

Uploaded by

CTV NewsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TEST

TEST

Uploaded by

CTV NewsCopyright:

Available Formats

Maternal Risk Factors for Gastroschisis in Canada

Erik D. Skarsgard*1, Christopher Meaney2, Kate Bassil3, Mary Brindle4, Laura Arbour5,

Rahim Moineddin2, and the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet)

Background: Gastroschisis is a congenital abdominal wall defect that occurs

in one per 2200 pregnancies. Birth defect surveillance in Canada has shown

that the prevalence of gastroschisis has increased threefold over the past 10

years. The purpose of this study was to compare maternal exposures data

from a national gastroschisis registry with pregnancy exposures from vital

statistics to understand maternal risk factor associations with the occurrence

of gastroschisis. Methods: Using common definitions, pregnancy cohorts were

developed from two databases. The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

database, a population-based dataset was used to record maternal exposures

for women who experienced a gastroschisis pregnancy, while a

contemporaneous, geographically cross-sectional control cohort of pregnant

women and their exposures was developed from Canadian Community Health

Survey data. Groups comparison of maternal risk factors was performed using

univariate and multivariate logistic generalized estimating equation techniques.

Results: A total of 692 gastroschisis pregnancies (from Canadian Pediatric

Surgery Network) and 4708 pregnancies from Canadian Community Health

Survey were compared. Younger maternal age (odds ratio, 0.85; 95%

confidence interval, 0.830.87; p < 0.0001), smoking (odds ratio, 2.86; 95%

confidence interval, 2.223.66; p < 0.0001), a history of pregestational or

gestational diabetes (odds ratio, 2.81; 95% confidence interval, 1.425.5;

p 5 0.0031), and use of medication to treat depression (odds ratio, 4.4; 95%

confidence interval, 1.3811.8; p 5 0.011) emerged as significant

associations with gastroschisis pregnancies. Conclusion: Gastroschisis in

Canada is associated with maternal risk factors, some of which are

modifiable. Further studies into sociodemographic birth defect risk are

necessary to allow targeted improvements in perinatal health service delivery

and health policy.

Introduction

The Public Health Agency of Canada has documented a

threefold rise in prevalence of GS over the last 10 years,

to approximately 1 per 2200 births (Moore et al., 2013). A

similarly observed increase in GS prevalence has been

made in many other countries, including the United States

and several European nations (Laughon et al., 2003; International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and

Research, 2009; Langlois et al., 2011), prompting references to a Gastroschisis Epidemic (Kilby, 2006; Mastroiacovo et al., 2006; Keys et al., 2008). Epidemiologic studies

of causation of GS have emerged from single state/region/

country birth defect registries, to pooled data from a network of population-based congenital anomaly reporting

registries, all with an intent to better understand modifiable risk factors for GS.

Since 2006, the Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

(CAPSNet) has collected standardized pre and postnatal

data on all cases of GS admitted to each of the 17 hospitals in Canada that provide specialty pediatric care for

birth defects. The collected data include maternal demographic (age, home postal code) and exposures (e.g., smoking, alcohol, recreational drug use) data for all GS

pregnancies. The purpose of this study was to explore the

association between maternal factors and GS in Canada by

comparing maternal exposures data for GS cases identified

in CAPSNet with household exposures data for a geographically cross-sectional group of pregnant women from a

Canadian Vital Statistics database.

Gastroschisis (GS) is a congenital abdominal wall defect

which results in the extrusion of the developing fetal intestines into the amniotic space. It is usually detected prenatally by maternal serum screening and ultrasound, and

tends to occur as an isolated congenital anomaly. When a

prenatal diagnosis of GS is made, arrangements are made

for delivery at an obstetrical center that is functionally

linked to a specialty pediatric hospital with the capability

of providing surgical treatment after birth as well as essential neonatal intensive care. Survival following birth of an

infant with GS exceeds 90%, however, survivors may

require prolonged hospitalization in high intensity nurseries, which makes them among the most expensive of congenital anomalies to treat (Sydorak et al., 2002; Skarsgard

et al., 2008). The specific cause of GS remains unknown,

although the available evidence suggests interactions of

multiple maternal risk factors lead to occurrence.

Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada

Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto,

Toronto, Canada

3

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

4

Department of Surgery, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada

5

Department of Medical Genetics, University of British Columbia, Vancouver,

Canada

2

This work was Supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research

(CIHR) Funding Reference # Sec 117139.

*Correspondence to: Erik D. Skarsgard, K0110 ACB, 4480 Oak Street, Vancouver, BC, V6H 3V4 Canada. E-mail: eskarsgard@cw.bc.ca

Published online 12 February 2015 in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.

com). Doi: 10.1002/bdra.23349

C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

V

Birth Defects Research (Part A) 103:111118, 2015.

C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

V

Key words: gastroschisis; population-based registry; maternal risk factors;

maternal age; teratogenesis

Materials and Methods

The two primary data sources for this study consisted of

the CAPSNet registry, and the Canadian Community Health

Survey (CCHS, which is administered by Statistics Canada),

112

a cross-sectional survey which collects information related

to health status and health determinants of Canadians at

the household level, across all geographic regions (dissemination areas) in Canada (Canadian Community Health Survey [CCHS], 2014). Through integration of data from these

two sources, we were able to develop health and maternal

exposure risk profiles of mothers who gave birth to infants

with GS (from CAPSNet), to pregnant women sampled

from the CCHS. The variables that were consistently collected across the two data sources include: history of alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, cocaine, methamphetamine and

heroin use during pregnancy, history of diabetes (type 1,

type 2, or gestational), use of depression medication during pregnancy, and use of folic acid during pregnancy.

CAPSNet

The CAPSNet consists of the 17 perinatal/surgical centers

that provide population-based pre- and postnatal care for

GS in Canada (The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network

[CAPSNet], 2014). The CAPSNet registry was designed specifically for outcomes research and contains rigorously

defined fields that allow discrimination of risk variables

and treatment, as well as relevant clinical outcomes from

the birth hospitalization to death or discharge. Data are

collected from maternal and infant charts by trained

abstractors using a customized data entry program with

built-in error checking and a standard manual of operations and definitions. Abstracted prenatal information

details maternal risk variables including demographics

(postal code of residence), prenatal exposures including

smoking, alcohol, and a variety of nonprescription drugs;

medical comorbidities, quantitative ultrasound and other

prenatal diagnostic data, and information on all pregnancy

outcomes including stillbirths. All data collection is

observational and is not used to influence the care of

any individual patient.

Data from each CAPSNet center are de-identified and

transmitted electronically to a centralized repository for

cleaning, quality assurance and storage. Thereafter, the

aggregate dataset is overseen by a research coordinator

and a geographically representative, multidisciplinary

steering committee comprised of pediatric surgeons, neonatologists, maternal-fetal medicine specialists, and an epidemiologist. Aggregate data use for research purposes is

enabled by inter-institutional data sharing agreements,

and requires that each CAPSNet center maintain institutional review board approval for data collection. Aggregate

data release requires project-specific institutional review

board approval from the principal investigators institution, and complies with Health Information Portability and

Accountability Act (HIPPA) requirements.

CCHS

CCHS is a cross-sectional household survey administered

by Statistics Canada on an annual basis (before 2007 the

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

survey was conducted in alternate years). The CCHS survey of 65,000 Canadians per year, targets persons aged 12

years or older who are living in private dwellings in the

ten provinces and the three territories. Persons living on

Indian Reserves or Crown lands, clientele of institutions,

full-time members of the Canadian Armed Forces, and residents of certain remote regions are excluded from this

survey. The sampling method ensures that all provinces

health regions (provincially designated health service

areas) are sampled in proportion to the size of their

respective populations.

The CCHS covers approximately 98% of the Canadian

population aged 12 or older, and collects information

related to health status, health care usage, and health

determinants. These data can then be used to estimate, on

a health regional basis, potential relationships between

health outcomes and economic, demographic, occupational,

and environmental factors. Ultimately, the data are meant

to provide a better understanding of the health of Canadians and inform public policy, through health surveillance

and the facilitation of population health research.

Study Design

This study used a cross-sectional design. In this design,

the GS (case) sample consisted of all mothers identified

from the CAPSNet database between 2006 and 2012, who

had a GS pregnancy resulting in a live birth, stillbirth or

termination of pregnancy, while the non-GS (control) sample consisted of all pregnant mothers responding to the

CCHS surveys (Cycle 1.1 [2001], Cycle 2.1 [2003], Cycle

3.1 [2005], CCHS 2007, and CCHS 2010). Although CCHS

data do not differentiate women whose pregnancy was or

was not complicated by GS (or any other birth defect), it

is assumed that the CCHS cohort represents a reasonable

control group because the sample is large and the overall

birth defect rate is known to be rare, and because controls

misclassification causes bias toward the null for the risk

factors.

The comparison variables of interest between cases

and controls are summarized in Table 1. Definitions of

exposure in both databases included any use, on at least

one occasion of the listed substances, during a time when

the woman was pregnant, whether known or unknown

(Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network, 2013). A coincident

history of diabetes, could mean that the woman had preexisting diabetes (type 1 or 2) diagnosed by a health professional or had gestational diabetes requiring medication

or dietary modification. A history of depression requiring

medication meant that the woman had a mood disorder

diagnosed by a health professional and received antidepressive medication at any time in CAPSNet, (or within

past month for CCHS), for any duration during her pregnancy. Folic acid use meant that the woman used a multivitamin containing folic acid before or upon realization of

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111118 (2015)

113

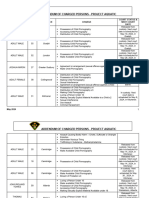

TABLE 1. CCHS and CAPSNet Variables Definitions

CAPSNet data definitionsa

CCHS questions

Alcohol

Did you drink any alcohol during your last

Record if any alcohol use during pregnancy

pregnancy?

1 Yes 2 No

Cigarette smoking

Did you smoke during your last pregnancy?b

Record if cigarettes were smoked during this preg-

1 Yes 2 No

nancy. If unknown or if no cigarettes were

During your last pregnancy, did you smoke daily,

occasionally or not at all?

smoked during pregnancy, leave the box

unchecked.

1 Daily 2 Occasionally 3 Not at all

Marijuana

Cocaine

Methamphetamine

Have you used marijuana in the past 12 months?

Record whether or not the mother used any of the

1 Yes 2 No

following during this pregnancy.

Have you used cocaine or crack in the past 12

Marijuana

months?

Cocaine

1 Yes 2 No

Methamphetamine or crystal meth

Have you used speed (amphetamines) in the past 12

Heroin: includes methadone

months?

1 Yes 2 No

Heroin

Have you used heroin in the past 12 months?

1 Yes 2 No

History diabetes

Do you have diabetes?

Record the mothers status as a diabetic during this

1 Yes 2 No

pregnancy.

None

Pre-existing DM diagnosed prior to conception

Gestational diabetes

Unknown

Depression meds

In the past month, did you take anti-depressants

such as Prozac, Paxil or Effexor?:

nancy: includes selective-serotonin reuptake

1 Yes 2 No

Folic acid

Record use of antidepressants during this preg-

inhibitors (SSRI) (i.e. Zoloft, Paxil or Prozac)

Did you take a vitamin supplement containing folic

Record whether the mother has been taking regular

acid before your pregnancy, that is, before you found

prenatal vitamins during this pregnancy.

out that you were pregnant?

None: no folic acid nor prenatal vitamins taken

1 Yes 2 No

before the start of the second trimester.

Folic acid: initiated prior to pregnancy or within the

first trimester.

Vitamins: initiated prior to pregnancy or within the

first trimester

Unknown

From CAPSNet Abstractors Manual vol 5.1.0, April 2013.

Question from CCHS 1.1.

Question from CCHS 2.1, 3.1, 2007, 2010.

her pregnancy. Age was estimated from maternal date of

birth, as reported through both datasets, and was analyzed

as a continuous variable. Geographic location of home

residence was assigned using dissemination area (DA), a

small, relatively stable geographic unit composed of one or

more adjacent dissemination blocks. It is the smallest

114

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

FIGURE 1. Inclusion/exclusion flow diagram of patients

analyzed in this study.Patients were collected from

five cycles of the CCHS (1.1, 2.1, 3.1, 2007 and

2010). Patients who were pregnant during the time of

the survey were included. The CAPSNet registry was

used to identify women who had gastroschisis pregnancies between 2006 and 2012, and those with

complete data were included.

standard geographic area for which all census data are

disseminated within Canada, and can be assigned using

the Postal Code Conversion File software (Wilkins and

Khan, 2010).

Initially, we intended to perform a 1:1 matched case

control study where mothers were matched on age (a

known GS risk factor) and DA, which would have allowed

us to control for some predisposing environmental factors.

When analysis was completed under the proposed design

many associations between categorical risk factors and

outcome of a GS pregnancy had low counts in some cells

of the contingency tables. As a result, these data could not

be released from Statistics Canada due to anonymity concerns and an alternative design was necessary.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

To avoid issues related to low cell counts, we chose not to

match based on any demographic variables a priori. Rather

we treated GS mothers and CCHS controls as being

clustered within DAs and used logistic generalized estimating equation methods to account for this design feature. Moreover, we treated maternal age, (a known risk

factor for GS occurrence) as a covariate in each model and

estimated the adjusted odds of a GS birth, as a function of

other hypothesized maternal risk factors after controlling

for age. Where sample size allows we have summarized

the association between maternal factors (all categorical

variables) and GS occurrence using contingency tables.

Results

The process of deriving the case (GS pregnancies from

CAPSNet) and control (non-GS pregnancies from CCHS)

maternal cohorts is illustrated in Figure 1. After exclusions

for incomplete data there were a total of 692 GS pregnan-

cies (from CAPSNet) and 4708 control pregnancies from

CCHS.

The 692 GS mothers came from a total of 465 DAs and

the 4708 control mothers came from a total of 1285 DAs.

The mean age of the GS mothers was significantly lower

than that of the controls (23.64 years; SD 5 4.79 years vs.

28.84 years; SD 5 6.11 years; p < 0.0001). When maternal

age was interrogated as a predictive variable using bivariate and multivariate generalized estimating equation models, it emerged as independently predictive of the

occurrence of a GS pregnancy (odds ratio [OR], 0.85; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 0.830.87; p < 0.0001).

The relationships between maternal risk factors during

pregnancy and the occurrence of GS are summarized in

Tables 2 and 3. Table 2 displays 2x2 tables, estimated

odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals and p-values associated with a variety of maternal substance exposures during pregnancy, folic acid use, depression medication use or

a history of diabetes. Due to low cell counts, exposures

data for cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine were suppressed, and so an aggregate variable (any illicit drug use

inclusive of marijuana) was created. Table 2 suggests that

exposure to alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, illicit drugs or

medication for depression during pregnancy, as well as a

history of diabetes increases the likelihood of a GS pregnancy. Conversely, the use of folic acid appears to be protective against a GS pregnancy.

Given the awareness of young maternal age as a risk

factor for GS, age adjustment was performed in the logistic

generalized estimating equation risk modeling, as summarized in Table 3. After adjustment for maternal age, the

association between maternal exposures to cocaine and

marijuana individually, (and illicit drugs collectively) and

the occurrence of GS persists. In the multivariate model,

the composite illicit drug variable, emerges as a

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111118 (2015)

115

TABLE 2. 2 x 2 Contingency Tables with Odds Ratios, 95% Confidence Intervals, and p-Values Describing the Relationship between the Association

between Maternal Risk Factors and the Occurrence of a Gastroschisis

Pregnancy

GS

(N, %)

Controls

(N, %)

Odds

ratio

95% CI

p-Value

Alcohol

Yes

No

44 (7.02)

203 (4.36)

1.66 1.18, 2.32

0.0031

583 (92.98) 4454 (95.64)

Tobacco

Yes

231 (33.38) 610 (13.06) 3.34 2.79, 3.99 <0.0001

No

461 (66.62) 4061 (86.94)

Marijuana

Yes

78 (11.27)

55 (1.56)

No

614 (88.73) 3477 (98.44)

8.03 5.63, 11.46 <0.0001

Cocaine

Yes

No

Methamphetamine

Yes

No

Heroin

Yes

No

Any illicit drug

Yes

92 (13.29)

57 (1.61)

No

600 (86.71) 3475 (98.39)

9.35 6.64, 13.15 <0.0001

History diabetes

Yes

No

19 (2.75)

56 (1.19)

2.34 1.39, 3.98

0.0011

672 (97.25) 4651 (98.81)

Depression meds

Yes

No

22 (3.18)

26 (0.70)

4.65 2.61, 8.30 <0.0001

670 (96.82) 3544 (99.30)

Folic acid

Yes

134 (19.36) 1289 (27.83) 0.62 0.51, 0.76 <0.0001

No

558 (80.64) 3342 (72.17)

Empty cells, suppressed due to low counts.

significant predictor of GS occurrence. Similarly, although

alcohol exposure remained predictive after age adjustment,

its predictive association with GS occurrence disappeared

with multivariate analysis. The other significant variable

change associated with age-adjustment was the loss of the

apparent protection associated with folic acid use.

Younger maternal age, smoking (OR, 2.86; 95% CI,

2.223.66; p < 0.0001), a history of diabetes (OR, 2.81;

95% CI, 1.425.5; p 5 0.0031), history of illicit drug use

(OR, 3.54; 95% CI, 2.225.63; p < 0.0001), and use of medication to treat depression (OR, 4.4; 95% CI, 1.3811.8;

p 5 0.011) remained independently predictive of GS

occurrence.

Discussion

Gastroschisis is among the most common structural birth

defects, and its cause remains unknown. The phenomenon

of increased prevalence has been observed in several jurisdictions, and continues to be a stimulus for epidemiologic

evaluation of risk factors, both maternal (physiological,

teratogens, socioeconomic) and environmental (Torfs et al.,

1994; Reefhuis and Honein, 2004; Rittler et al., 2007; Castilla et al., 2008; Salemi et al., 2009; Waller et al., 2010;

Agopian et al., 2013).

The most widely observed association in GS pregnancy

occurrence is its inverse relationship with maternal age.

The risk seems to be highest in the teenage cohort. Aggregate data from EUROCAT (a consortium of birth defect

registries which combines registry data from 23 countries)

report a relative risk of 7.0 in the under 20 age cohort,

and a RR of 2.4 in the 20 to 24 age cohort, compared with

the age 25 to 29 reference group (Reefhuis and Honein,

2004). While a strong association with maternal age is

certain, what is less clear is whether the increased prevalence of GS is due exclusively to an increased prevalence

within the teenage mother population, or to a GS prevalence increase across all maternal age strata (Kazaura

et al., 2004; Loane et al., 2007). Regardless of the exact

nature of this association, the relationship between maternal age and GS should be factored in to all studies of GS

epidemiology, with analyses of all putative risk factors

being subject to age-adjustment.

Several epidemiologic studies of causation suggest a

moderate risk of GS associated with smoking during pregnancy (Haddow et al., 1993; Draper et al., 2008; Feldkamp

et al., 2008), and data from Canada identify a higher rate

of smoking during pregnancy in mothers with GS (Weinsheimer et al., 2008). Not only is there a maternal smoking

association with GS prevalence, there is also an association

with clinical outcome, with GS infants of smoking mothers

having more severe bowel injury at birth (Weinsheimer

et al., 2008; Brindle et al., 2012). In addition to smoking,

illicit drug use is another purported risk factor for GS,

with cocaine, marijuana, and methamphetamine observed

to have a significant age-adjusted association with GS

occurrence (Draper et al., 2008; Weinsheimer et al., 2008;

Brindle et al., 2012).

The current study provides further insight into GS epidemiology through integration of a contemporary, Canadian population-based GS dataset with Vital Statistics data

from a cross-sectional, representative cohort of pregnant

mothers from the Canadian Community Health Survey.

Critical to the accuracy and reliability of this dataset

116

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

TABLE 3. Bivariate, Age-Adjusted, and Multivariate Logistic Regression Models Evaluating Risk Factor Prediction of a Gastroschisis Pregnancy

Bivariate logistic gee model

OR

95% CI

p-value

Age-adjusted logistic GEE model

OR

95% CI

p-value

Multivariate logistic GEE model

OR

95% CI

p-value

Age (years)

0.84

0.83, 0.86

<0.0001

0.85

0.83, 0.87

<0.0001

Alcohol

1.65

1.20, 2.29

0.0023

1.67

1.22, 2.30

0.0016

0.82

0.57, 1.18

0.2885

Tobacco

3.32

2.77, 3.98

<0.0001

2.53

2.08, 3.06

<0.0001

2.86

2.22, 3.66

<0.0001

Marijuana

7.94

5.50, 11.48

<0.0001

4.58

3.05, 6.90

<0.0001

Cocaine

11.32

5.10, 25.13

<0.0001

8.02

3.41, 18.83

<0.0001

Methamphetamine

2.90

0.83, 10.15

0.0950

1.16

0.32, 4.21

0.8236

Heroin

10.05

1.88, 53.79

0.0070

5.39

0.73, 39.87

0.0990

Any illicit drug

9.24

6.47, 13.21

<0.0001

5.46

3.69, 8.07

<0.0001

3.54

2.22, 5.63

<0.0001

History diabetes

2.29

1.39, 3.78

0.0011

3.40

1.97, 5.88

<0.0001

2.81

1.42, 5.57

0.0031

Depression meds

4.69

2.60, 8.45

<0.0001

6.09

2.97, 12.49

<0.0001

4.04

1.38, 11.80

0.0108

Folic Acid

0.62

0.51, 0.76

<0.0001

0.95

0.77, 1.17

0.6448

0.88

0.69, 1.14

0.3514

, not used in multivariate model, rather combined in composite illicit drug variable.

GEE, general estimating equation.

integration, is the accuracy of case and control ascertainment, and equivalence of risk factor definitions. One of the

limitations of birth defect registry ascertainment (for

example EUROCAT) is the accuracy of discharge diagnosis

abstraction from hospital charts. The diagnostic code for

GS (International Classification of Disease, ICD-9 756.7) is

shared with another congenital defect of the abdominal

wall (omphalocele), which differs dramatically from GS

and is frequently associated with genetic patterns of inheritance. The British Pediatric Association modification of

ICD-9 is used by some registries, and allows differentiation

of gastrochisis from omphalocele, however it is not used

uniformly. The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet) database, on the other hand, is a research database,

for which cases are ascertained by clinicians who are

directly involved in either prenatal diagnosis or postnatal

treatment of GS, which improves diagnostic accuracy

considerably.

Our study reinforces the inverse relationship between

maternal age and GS occurrence, as well as associations

with maternal smoking and illicit drug use, which were

both independently predictive of occurrence on multivariate logistic regression modeling. Although it was observed

to be protective on univariate analysis, use of folic acid

lost its predictive effect following adustment for maternal

age. We also observed that treatment of depression with

any anti-depressive medication was associated with an

increased risk of GS (OR, 4.04; 95% CI, 1.38 5 11.8). A

recent report from the National Birth Defects Prevention

Study using a case control methodology, looked at the

effect of periconceptual use of the anti-depressant venlafaxine on the occurrence of birth defects, and observed a

statistically significant association with GS, after adjusting

for maternal age and race (Polen et al., 2013). Conversely,

two other studies looking at associations between selective

serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy did not demonstrate a significantly increased rate of common structural

birth defects among exposed infants (Alwan et al., 2007;

Louik et al., 2007). It is likely that an association between

depression and/or its treatment and the occurrence of GS

has many confounders, and, therefore, caution should be

exercised in inferring a direct relationship in the absence

of other supportive studies.

Our data identify a maternal history of pregestational

type 1 or type 2 or gestational diabetes mellitus as being

independently predictive of a GS pregnancy. While a relationship between pregestational/gestational diabetes and

increased rates of several birth defects (specifically, cardiovascular defects), is well established, no specific association with human GS has been reported previously.

Although the concept of abdominal wall malformations

associated with a hyperglycemic state is plausible and supported by observations of GS in pregnant rats who were

made diabetic by intraperitoneal streptozotocin (Padmanabhan and al-Zuhair, 19871988), this relationship is

intuitively at odds with the observed protective effect of

overweight or obese prepregnancy BMI on the risk of having a GS pregnancy (Lam et al., 1999; Waller et al., 2007;

Stothard et al., 2009). A potential explanation for our findings is an underreporting of gestational diabetes in the

CCHS cohort. A population-based study of rates of biochemically validated gestational diabetes in the province

of Ontario, showed a doubling of age-adjusted rate from

2.7 to 5.6% between 1996 and 2010 (Feig et al., 2014),

which is substantially higher than the rate of 1.2%

observed in our CCHS cohort, and suggests the possibility

BIRTH DEFECTS RESEARCH (PART A) 103:111118 (2015)

that a diagnosis of gestational diabetes was unknown to

many pregnant women at the time they were surveyed.

We are reluctant to ascribe much significance to this

observation, other than to note its statistical significance,

and suggest that future studies of GS epidemiology should

evaluate this potential association further.

While this study has some unique strengths, it also has

limitations. Combining unrelated sources of data (despite

common definitions) for cases and controls raises concern

over the comparability of maternal exposures between

groups. Both data sources reflect self-reporting and are,

therefore, subject to recall bias, and potentially, a reluctance to admit to risky behavior during pregnancy. Neither

source specifically identifies pre or peri-conceptual exposure from exposure during pregnancy. The inquiry around

timing of exposure in the CCHS database is variable, ranging from past month (antidepressant use), during pregnancy (alcohol, smoking), or past 12 months (illicit

drugs, which could capture exposures before pregnancy).

As previously acknowledged, the occurrence of birth

defects, including GS within the control CCHS cohort cannot be excluded, yet we contend that it represents a reasonable control sample based on its size and the low birth

defect rate.

Finally, the time periods reflected by the two databases

are different: the CCHS controls represent an aggregate

cohort from surveys done in 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, and

2010, while the CAPSNet cases were accrued between

2006 and 2012). Another limitation is the inability to control for geographic factors (location of maternal residence). Although our initial intent was to undertake case/

control matching by maternal age and dissemination area,

the low counts in many of the DA cells meant that these

data could not be released. We have, therefore, had to

assume, for the purpose of this study, that GS occurs with

the same prevalence across Canada, which we know is not

the case, based on spatial mapping analysis of GS cases

across Canada (K. Bassil, personal communication, 2014).

We are also unable to make any observations of potential

associations between maternal race and GS. In another

CAPSNet study of GS epidemiology, we have observed a

higher than expected prevalence of GS pregnancies in Aboriginal women, although maternal ethnicity does not

emerge as independently predictive of occurrence (Brindle

et al., 2012). The fact that the CCHS excludes Canadians

living on Indian reserves means that Aboriginals may be

underrepresented in our control group.

Future studies on causation of GS and other high

impact structural birth defects will be enabled by our ability to integrate data from different sources, and speak to

the necessity of having access to and linkages for a variety

of clinical and administrative datasets. Improvements in

perinatal health service delivery and health policy represent some of our greatest opportunities for outcome

improvement for birth defects like GS.

117

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Alison Butler, CAPSNet coordinator, for

her administrative efforts in support of this work

References

Agopian AJ, Langlois PH, Cai Y, et al. 2013. Maternal residential

atrazine exposure and gastroschisis by maternal age. Matern

Child Health J 17:17681775.

Alwan S, Reefhuis J, Rasmussen SA, et al. 2007. Use of selective

serotonin-reuptake inhibitors in pregnancy and the risk of birth

defects. N Engl J Med 356:26842692.

Brindle ME, Flageole H, Wales PW, et al. 2012. Influence of

maternal factors on health outcomes in gastroschisis: a Canadian

population-based study. Neonatology 102:4552.

Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). 2014. Available at:

http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function5getSurvey&

SDDS53226. Accessed August 29, 2014.

Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network. 2013. CAPSNet Data

Abstractors Manual. V 5.1.0. Available at: http://www.capsnetwork.org. Accessed August 29, 2014.

Castilla EE, Mastroiacovo P, Orioli IM. 2008. Gastroschisis: international epidemiology and public health perspectives. Am J Med

Genet C Semin Med Genet 148C:162179.

Draper ES, Rankin J, Tonks AM, et al. 2008. Recreational drug

use: a major risk factor for gastroschisis? Am J Epidemiol 167:

485491.

Feig DS, Hwee J, Shah BR, et al. 2014. Trends in incidence of diabetes in pregnancy and serious perinatal outcomes: a large,

population-based study in Ontario, Canada, 19962010. Diabetes

Care 37:15901596.

Feldkamp ML, Alder SC, Carey JC. 2008. A case control

population-based study investigating smoking as a risk factor for

gastroschisis in Utah, 19972005. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol

Teratol 82:768775.

Haddow JE, Palomaki GE, Holman MS. 1993. Young maternal age

and smoking during pregnancy as risk factors for gastroschisis.

Teratology 47:225228.

International Clearinghouse for Birth Defects Surveillance and

Research. 2009. Annual Report 2009 with data for 2007. Rome, Italy:

International Center on Birth Defects. Available at: http://www.

icbdsr.org/filebank/documents/ar2005/Report2009.pdf. Accessed

Month day, year.

Kazaura MR, Lie RT, Irgens LM, et al. 2004. Increasing risk of

gastroschisis in Norway: an age-period-cohort analysis. Am J Epidemiol 159:358363.

Keys C, Drewett M, Burge DM. 2008. Gastroschisis: the cost of an

epidemic. J Pediatr Surg 43:654657.

Kilby MD. 2006. The incidence of gastroschisis. BMJ 332:250

251.

118

RISK FACTORS FOR GASTROSCHISIS IN CANADA

Lam PK, Torfs CP, Brand RJ. 1999. A low pregnancy body mass

index is a risk factor for an offspring with gastroschisis. Epidemiology 10:717721.

Rittler M, Castilla EE, Chambers C, et al. 2007. Risk for gastroschisis in primigravidity, length of sexual cohabitation, and change in

paternity. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 79:483487.

Langlois PH, Marengo LK, Canfield MA. 2011. Time trends in the

prevalence of birth defects in Texas 19992007: real or artifactual? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 91:902917.

Salemi JL, Pierre M, Tanner JP, et al. 2009. Maternal nativity as a

risk factor for gastroschisis: a population-based study. Birth

Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 85:890896.

Laughon M, Meyer R, Bose C, et al. 2003. Rising birth prevalence

of gastroschisis. J Perinatol 23:291293.

Skarsgard ED, Claydon J, Bouchard S, et al. 2008. Canadian Pediatric Surgical Network: a population-based pediatric surgery network and database for analyzing surgical birth defects. The first

100 cases of gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 43:3034.

Loane M, Dolk H, Bradbury I; EUROCAT Working Group. 2007.

Increasing prevalence of gastroschisis in Europe 19802002: a

phenomenon restricted to younger mothers? Paediatr Perinat

Epidemiol 21:363369.

Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, et al. 2009. Maternal overweight

and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic

review and meta-analysis. JAMA 301:636650.

Louik C, Lin AE, Werler MM, et al. 2007. First-trimester use of

selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors and the risk of birth

defects. N Engl J Med 356:26752683.

Sydorak RM, Nijagal A, Sbragia L, et al. 2002. Gastroschisis: small

hole, big cost. J Pediatr Surg 37:669672.

Mastroiacovo P, Lisi A, Castilla EE. 2006. The incidence of gastroschisis: research urgently needs resources. BMJ 332:423424.

The Canadian Pediatric Surgery Network (CAPSNet). 2014. Available at: http://www.capsnetwork.org. Accessed August 29, 2014.

Moore A, Rouleau J, Skarsgard ED. 2013. Chapter 7: Gastroschisis. In: Public Health Agency of Canada. Congenital anomalies in

Canada 2013: a perinatal health surveillance report. Ottawa, Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada. pp. 5764. Available at:

http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2014/aspc-phac/

HP3540-2013-eng.pdf. Accessed Month day, year.

Torfs CP, Velie EM, Oechsli FW, et al. 1994. A population-based

study of gastroschisis: demographic, pregnancy, and lifestyle risk

factors. Teratology 50:4453.

Padmanabhan R, al-Zuhair AG. 19871988. Congenital malformations and intrauterine growth retardation in streptozotocin

induced diabetes during gestation in the rat. Reprod Toxicol 1:

117125.

Polen KN, Rasmussen SA, Riehle-Colarusso T, et al. 2013. Association between reported venlafaxine use in early pregnancy and

birth defects, national birth defects prevention study, 1997

2007. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 97:2835.

Reefhuis J, Honein MA. 2004. Maternal age and nonchromosomal birth defects, Atlanta 19682000: teenager or

thirty-something, who is at risk? Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol

Teratol 70:572579.

Waller DK, Shaw GM, Rasmussen SA, et al. 2007. Prepregnancy

obesity as a risk factor for structural birth defects. Arch Pediatr

Adolesc Med 161:745750.

Waller SA, Paul K, Peterson SE, et al. 2010. Agricultural-related

chemical exposures, season of conception, and risk of gastroschisis in Washington State. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202:241 e1e6.

Weinsheimer RL, Yanchar NL, Canadian Pediatric Surgical Network. 2008. Impact of maternal substance abuse and smoking

on children with gastroschisis. J Pediatr Surg 43:879883.

Wilkins R, Khan S. Automated geographic coding based on the

statistics Canada postal code conversion files. Including postal

codes through October 2010. Available at: http://www.sas.com/

offices/NA/canada/downloads/presentations/HUG10/Bonus.pdf.

Accessed Month day, year.

You might also like

- Epstein Documents (Jan. 3)Document943 pagesEpstein Documents (Jan. 3)CTV News81% (42)

- Epstein Documents (Jan. 4)Document341 pagesEpstein Documents (Jan. 4)CTV News75% (8)

- Defamation ClaimDocument13 pagesDefamation ClaimCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Victim Impact Statement From The Mahaffy FamilyDocument6 pagesVictim Impact Statement From The Mahaffy FamilyCTV News100% (2)

- Coronation Order of ServiceDocument50 pagesCoronation Order of ServiceCTV News100% (5)

- Neonatal Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandNeonatal Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Laundress Recall NoticeDocument5 pagesThe Laundress Recall NoticeCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandCardiovascular Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Victim Impact Statement From Donna and Doug FrenchDocument4 pagesVictim Impact Statement From Donna and Doug FrenchCTV News100% (2)

- Nova Scotia Mass Killing ITO 1Document40 pagesNova Scotia Mass Killing ITO 1Jenn Hoegg100% (1)

- Nova Scotia Mass Killing ITO 1Document40 pagesNova Scotia Mass Killing ITO 1Jenn Hoegg100% (1)

- Humboldt Broncos Jaskirat Singh Sidhu SentencingDocument35 pagesHumboldt Broncos Jaskirat Singh Sidhu SentencingDavid A. Giles100% (2)

- Bowerman 2ce SSM Ch13Document5 pagesBowerman 2ce SSM Ch13Sara BayedNo ratings yet

- Global CDMR TrendDocument25 pagesGlobal CDMR TrendjdmaneNo ratings yet

- Early Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesDocument6 pagesEarly Prediction of Preterm Birth For Singleton, Twin, and Triplet PregnanciesNi Wayan Ana PsNo ratings yet

- Halliday 1997Document8 pagesHalliday 1997JohnnyNo ratings yet

- The National Birth Center Study IIDocument12 pagesThe National Birth Center Study IIapi-38108107No ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Management of Pregnant Women With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Management of Pregnant Women With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewMichael ThomasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Risk FX SepsisDocument7 pagesJurnal Risk FX SepsiswilmaNo ratings yet

- Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia in Living Kidney DonorsDocument7 pagesGestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia in Living Kidney DonorsMichelNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Cesarean Delivery Practice in The United StatesDocument17 pagesContemporary Cesarean Delivery Practice in The United StatesdedypurnamaNo ratings yet

- Cervicitis in Adolescents - Do Clinicians Understand Diagnosis and Treatment?Document6 pagesCervicitis in Adolescents - Do Clinicians Understand Diagnosis and Treatment?brookswalshNo ratings yet

- s12884 016 1137 ZDocument10 pagess12884 016 1137 Zmohd bakarNo ratings yet

- Kangaroo Mother Care and Neonatal Outcomes A Meta-AnalysisDocument18 pagesKangaroo Mother Care and Neonatal Outcomes A Meta-AnalysisImtiyazi NabilaNo ratings yet

- Obstetric Care Consensus No2Document14 pagesObstetric Care Consensus No2Marco DiestraNo ratings yet

- Abortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1Document10 pagesAbortion, Stillbirth, Miscarriage in Ghana-1brijitcujoNo ratings yet

- Hernandez, Et Al.Document11 pagesHernandez, Et Al.Yet Barreda BasbasNo ratings yet

- Jurnal ObgynDocument10 pagesJurnal ObgynUgi RahulNo ratings yet

- Pregnancy Complications Among Women Born Preterm: Abst TDocument12 pagesPregnancy Complications Among Women Born Preterm: Abst TAnzory ErvanNo ratings yet

- New Study Finds That Taking Supplements Halves The Risk of Breast Cancer (Pan 2011)Document12 pagesNew Study Finds That Taking Supplements Halves The Risk of Breast Cancer (Pan 2011)EMFsafetyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Obesity and Gallstone Disease.18Document6 pagesPediatric Obesity and Gallstone Disease.18Merari Lugo OcañaNo ratings yet

- Delays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional StudyDocument15 pagesDelays in Receiving Obstetric Care and Poor Maternal Outcomes: Results From A National Multicentre Cross-Sectional Studykaren paredes rojasNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityMutia FatinNo ratings yet

- Integrating Genomics Into Healthcare: A Global ResponsibilityDocument14 pagesIntegrating Genomics Into Healthcare: A Global ResponsibilityMattNo ratings yet

- Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityDocument8 pagesRelationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal MortalityJenny YenNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A Questionnaire To Identify Severe Maternal Morbidity in Epidemiological SurveysDocument9 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A Questionnaire To Identify Severe Maternal Morbidity in Epidemiological SurveysZieft MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Cohort Profile: NICHD Fetal Growth Studies - Singletons and TwinsDocument13 pagesCohort Profile: NICHD Fetal Growth Studies - Singletons and Twinselin luhulimaNo ratings yet

- Rss Abstracts Booklet 2019 A4 PDFDocument324 pagesRss Abstracts Booklet 2019 A4 PDFSlice LeNo ratings yet

- Ghidini Et Al-2018-Prenatal DiagnosisDocument18 pagesGhidini Et Al-2018-Prenatal Diagnosismeaad kahtanNo ratings yet

- Journal Pmed 1000337Document9 pagesJournal Pmed 1000337Kristine BradyNo ratings yet

- P ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Document10 pagesP ('t':'3', 'I':'670968655') D '' Var B Location Settimeout (Function ( If (Typeof Window - Iframe 'Undefined') ( B.href B.href ) ), 15000)Septi RahadianNo ratings yet

- World Health Organization's Growth ReferenceDocument12 pagesWorld Health Organization's Growth Referenceemilce beltranNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument17 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDyah Gaby KesumaNo ratings yet

- McKay Et Al PAFs Complete Cases PDFDocument10 pagesMcKay Et Al PAFs Complete Cases PDFAnonymous oAoEj7pzNo ratings yet

- Congenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European JournaDocument1 pageCongenital Anomalies Parents Concerns and Opinions To - 2018 - European Journaburak yolcuNo ratings yet

- Fibroza 1Document8 pagesFibroza 1Popa ElenaNo ratings yet

- Perinatal Factor Journal PediatricDocument8 pagesPerinatal Factor Journal PediatricHasya KinasihNo ratings yet

- Use of Health System Data To Study Morbidity Related Pregnancy Loss, Schiavos, GUTTMACHER InstituteDocument18 pagesUse of Health System Data To Study Morbidity Related Pregnancy Loss, Schiavos, GUTTMACHER Institutejrodriguezcruz2023No ratings yet

- Factors Constraining Adherence SDocument20 pagesFactors Constraining Adherence SayangsarulNo ratings yet

- IJHS Robson PublicationDocument9 pagesIJHS Robson PublicationVinod BharatiNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Risk Factors of Neonatal Infections in A Rural Bangladeshi Population: A Community-Based Prospective StudyDocument11 pagesIncidence and Risk Factors of Neonatal Infections in A Rural Bangladeshi Population: A Community-Based Prospective Studyhasri ainunNo ratings yet

- Ectopic Pregnancy Rates in The Medicaid PopulationDocument7 pagesEctopic Pregnancy Rates in The Medicaid Populationistiiryan1No ratings yet

- JWH 2006 0295 LowlinkDocument7 pagesJWH 2006 0295 LowlinkRiskhan VirniaNo ratings yet

- One-Step Approach To Identifying Gestational Diabetes MellitusDocument12 pagesOne-Step Approach To Identifying Gestational Diabetes MellitusgracevitalokaNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatrick Et Al-2015-BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyDocument10 pagesFitzpatrick Et Al-2015-BJOG An International Journal of Obstetrics & GynaecologyCaroline SidhartaNo ratings yet

- Infant Mortality Rate and Medical Care in Kaliro District, UgandaDocument9 pagesInfant Mortality Rate and Medical Care in Kaliro District, UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Model PersalinanDocument9 pagesModel PersalinanAri Wahyu DewantiNo ratings yet

- Materi 8.2 Artikel 1Document8 pagesMateri 8.2 Artikel 1IndahPutri RamadhantiNo ratings yet

- 1Document11 pages1PSIK sarimuliaNo ratings yet

- Clinicians and Mothers Decision On Caeserean Section RevisedDocument34 pagesClinicians and Mothers Decision On Caeserean Section RevisedHoly Family NMTC Library, BerekumNo ratings yet

- Epidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.Document9 pagesEpidemiologic Study of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis in Children.marioNo ratings yet

- Depression Among CD and VDDocument7 pagesDepression Among CD and VDnoam tiroshNo ratings yet

- 9 JurnalDocument83 pages9 JurnalWanda AndiniNo ratings yet

- App Acog 2012Document10 pagesApp Acog 2012jimedureyNo ratings yet

- Maternal and Infant HealthDocument7 pagesMaternal and Infant Healthintellectual_masterNo ratings yet

- 2015 Article 43Document10 pages2015 Article 43Ebenezer AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Journal Pmed 1003686Document22 pagesJournal Pmed 1003686Nguyễn Đặng Tường Y2018No ratings yet

- Global Incidence of Necrotizing Enterocolitis A SyDocument15 pagesGlobal Incidence of Necrotizing Enterocolitis A SyJihan AnisaNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Fetal AssessmentDocument7 pagesAntenatal Fetal AssessmentFitriana Nur RahmawatiNo ratings yet

- Contraception for the Medically Challenging PatientFrom EverandContraception for the Medically Challenging PatientRebecca H. AllenNo ratings yet

- Multi-Cancer Early Detection: Incorporating Blood-Based Screening Tools into Primary Care PracticeFrom EverandMulti-Cancer Early Detection: Incorporating Blood-Based Screening Tools into Primary Care PracticeNo ratings yet

- OCPC Letter July 5, 2024Document3 pagesOCPC Letter July 5, 2024CTV NewsNo ratings yet

- CV-23-13 - Order - 26 Feb 2024Document3 pagesCV-23-13 - Order - 26 Feb 2024CTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Bros' DeclarationDocument3 pagesBros' DeclarationCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- The Liturgy For The Coronation Rite of King Charles IIIDocument42 pagesThe Liturgy For The Coronation Rite of King Charles IIICTV News100% (2)

- Addendum of Charged PersonsDocument10 pagesAddendum of Charged PersonsCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Opinions of Canada's Partnerships With Other CountriesDocument1 pageOpinions of Canada's Partnerships With Other CountriesCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Gov - Uscourts.flsd.618763.39.1 5Document8 pagesGov - Uscourts.flsd.618763.39.1 5Brandon Conradis100% (8)

- Wildfire Ready Community ConceptDocument1 pageWildfire Ready Community ConceptCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Vaccinated Against Covid 19 Public Health MeasuresDocument1 pageVaccinated Against Covid 19 Public Health MeasuresCTV News75% (12)

- Order/Address of The House of CommonsDocument5 pagesOrder/Address of The House of CommonsCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Near The Breaking Point - Mental Health in Small BusinessDocument25 pagesNear The Breaking Point - Mental Health in Small BusinessCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- EGC To OIPRD Report Back March 2022Document43 pagesEGC To OIPRD Report Back March 2022CTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Read A Summarized Version of The Report HereDocument48 pagesRead A Summarized Version of The Report HereKatelyn ThomasNo ratings yet

- AG March 24 2019 Letter To House and Senate Judiciary CommitteesDocument4 pagesAG March 24 2019 Letter To House and Senate Judiciary Committeesblc8893% (70)

- Letter To EnbridgeDocument2 pagesLetter To EnbridgeCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Gerald Butts Document SubmissionDocument39 pagesGerald Butts Document SubmissionCTV News100% (1)

- Read The New Evidence Submitted by Jody Wilson-RaybouldDocument43 pagesRead The New Evidence Submitted by Jody Wilson-RaybouldCTV News100% (2)

- Dec 30 2017 Interview TranscriptDocument5 pagesDec 30 2017 Interview TranscriptCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- An Open Letter From Families and Victims of The Danforth ShootingDocument2 pagesAn Open Letter From Families and Victims of The Danforth ShootingCTV NewsNo ratings yet

- JWR Letter Feb 12 2019Document1 pageJWR Letter Feb 12 2019CTV NewsNo ratings yet

- Program Data Mining With Business Analytics PDFDocument5 pagesProgram Data Mining With Business Analytics PDFAntonio AlvarezNo ratings yet

- MYP4-SA BALANCE Criterion DDocument3 pagesMYP4-SA BALANCE Criterion DMartin LevkovskiNo ratings yet

- Kai Peirce 2023Document84 pagesKai Peirce 2023VALERIA LUCERO AGUERONo ratings yet

- P. Siaperas Teacch Autism 10 (4) 2006Document14 pagesP. Siaperas Teacch Autism 10 (4) 2006Rania ChioureaNo ratings yet

- DocumentDocument10 pagesDocumentimNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document5 pagesAssignment 2Ali AzmatNo ratings yet

- Desertification and Land Degradation: Origins, Processes and Solution - A Literature ReviewDocument105 pagesDesertification and Land Degradation: Origins, Processes and Solution - A Literature ReviewAnubhav singhNo ratings yet

- Miscue FormDocument20 pagesMiscue FormAmin MofrehNo ratings yet

- Acupressure On Self-Reported Sleep Quality During Pregnancy: Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian StudiesDocument5 pagesAcupressure On Self-Reported Sleep Quality During Pregnancy: Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian StudiesSofia SagitaNo ratings yet

- Learning Environmental Ethics From Sebuah Wilayah Yang Tidak Ada Di Google Earth Novel by Pandu HamzahDocument14 pagesLearning Environmental Ethics From Sebuah Wilayah Yang Tidak Ada Di Google Earth Novel by Pandu HamzahayususantinaNo ratings yet

- Chapter III SampleDocument7 pagesChapter III SampleGlee Gray FrauletheaNo ratings yet

- EGAC RegulationDocument20 pagesEGAC RegulationHanaw MohammedNo ratings yet

- THE COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE VARIOUS TEACHING ACTIVITIES IN SELECTED PRESCHOOLS AT HAMIRPUR TEHSIL (U.P) INDIA: A COHORT STUDYDr. Kamlesh RajputDocument5 pagesTHE COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE VARIOUS TEACHING ACTIVITIES IN SELECTED PRESCHOOLS AT HAMIRPUR TEHSIL (U.P) INDIA: A COHORT STUDYDr. Kamlesh Rajputscience worldNo ratings yet

- Stat - Prob 11 - Q3 - SLM - WK6-8Document34 pagesStat - Prob 11 - Q3 - SLM - WK6-8Angelica CamaraoNo ratings yet

- Radiology Request Forms ResearchDocument8 pagesRadiology Request Forms Researchtruevine_ministryNo ratings yet

- The Barthel ADL Index: A Reliability Study : Rivermead Rehabilitation Centre, Bingdon Road, Oxford, Great BritainDocument3 pagesThe Barthel ADL Index: A Reliability Study : Rivermead Rehabilitation Centre, Bingdon Road, Oxford, Great BritainLuis Carlos Venegas SanabriaNo ratings yet

- Intro To QMMDocument14 pagesIntro To QMMFazal100% (1)

- Perception of Teachers' Towards Extensive Utilization of Information and Communication TechnologyDocument13 pagesPerception of Teachers' Towards Extensive Utilization of Information and Communication TechnologyJenny TiaNo ratings yet

- EBP 3013 Project Portfolio - Marketing Plan 2020-2021Document2 pagesEBP 3013 Project Portfolio - Marketing Plan 2020-2021LokaNo ratings yet

- Regulatory AffairsDocument29 pagesRegulatory Affairsmunny000No ratings yet

- Analysis of Slope Instability Factors and ProtectionDocument2 pagesAnalysis of Slope Instability Factors and ProtectionUmairKhalidNo ratings yet

- DLL Tle-6 Q2 W7Document2 pagesDLL Tle-6 Q2 W7Queen Labado DariaganNo ratings yet

- FALL 2012 - PSYC305 - Statistics For Experimental Design - SyllabusDocument4 pagesFALL 2012 - PSYC305 - Statistics For Experimental Design - SyllabuscreativelyinspiredNo ratings yet

- CEE 203 Syllabus PDFDocument3 pagesCEE 203 Syllabus PDFbinoNo ratings yet

- Vasudha Project: Theme-Smart Farming AimDocument5 pagesVasudha Project: Theme-Smart Farming Aimdivyom anandNo ratings yet

- Literature SurveyDocument3 pagesLiterature SurveyEzhilarasiNo ratings yet

- The ProblemDocument26 pagesThe ProblemNizelle Amaranto ArevaloNo ratings yet

- Mame LastDocument84 pagesMame LastlulumokeninNo ratings yet

- Pharma Facilities EbookDocument17 pagesPharma Facilities EbookJorge Humberto HerreraNo ratings yet