Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robert Goldberger v. Paul Revere Life Insurance Co., 165 F.3d 180, 2d Cir. (1999)

Robert Goldberger v. Paul Revere Life Insurance Co., 165 F.3d 180, 2d Cir. (1999)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robert Goldberger v. Paul Revere Life Insurance Co., 165 F.3d 180, 2d Cir. (1999)

Robert Goldberger v. Paul Revere Life Insurance Co., 165 F.3d 180, 2d Cir. (1999)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

165 F.

3d 180

Robert GOLDBERGER, Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

PAUL REVERE LIFE INSURANCE CO., Defendant-Appellee.

No. 98-7707.

United States Court of Appeals,

Second Circuit.

Argued Oct. 20, 1998.

Decided Jan. 22, 1999.

1

ROBERT E. GOLDBERGER, M.D., pro se, Roslyn, NY, for PlaintiffAppellant.

THOMAS J. MULLIGAN and JOSEPH P. AUGUSTINE, New York, N.Y.

(Windels, Marx, Davies & Ives, on the brief), for Defendant-Appellee.

Before: OAKES and WALKER, Circuit Judges, and KNAPP, Senior District

Judge.*

KNAPP, Senior District Judge:

In this diversity case, Plaintiff Robert Goldberger, M.D. ("Plaintiff"), held an

occupational disability policy entitled "The Professional Executive Insurance

Policy" (the "Policy") issued by the Defendant, Paul Revere Insurance

Company ( the "Company"), and made a claim thereunder. The District Court

(Jack B. Weinstein, Senior District Judge ) granted the Company's motion for

summary judgment and dismissed the complaint. For reasons that follow, we

set aside the order dismissing the complaint and remand the case for trial. In

considering this matter we shall, as we must, accept all of Plaintiff's allegations

as valid and draw all reasonable inferences in his favor.

The Policy

5

The Policy, which was issued by the Company to Plaintiff on June 18, 1973,

consists of four separate documents: (1) the Policy itself; (2) the application for

insurance; (3) an amendment attached to the Policy which defines the term

"Total Disability"; and (4) an explanatory letter similarly attached further

defining those words. A provision of the Policy itself specifically incorporates

the other three documents.

6

As so expanded, the Policy insures "against loss commencing on or after the

Date of Issue and while this policy is in force from injury or sickness as defined

herein." It cannot be canceled nor its premiums increased until the insured

reaches the age of sixty-five. No restrictive riders or changes in its provisions

are permitted. The "Policy Schedule" sets out the benefits and premiums. For

the Plaintiff, the Schedule specifies that for total disability from sickness, his

benefit is $2,000 per month, beginning on the 91 st day of disability, with a

maximum benefit period to age sixty-five. Further, because Plaintiff opted for

supplementary coverage for disability due to sickness after age sixty five, he

has additional benefits of $1,000 per month, beginning at age sixty-five, with a

lifetime maximum benefit period.

According to the Policy, "sickness" means "sickness or disease which first

manifests itself while this policy is in force." The Policy further provides that

total disability due to sickness exists "[i]f such sickness results in continuous

total disability while this policy is in force and requires the regular and personal

attendance of a licensed physician." The Policy states that " 'Total Disability'

means that, as a result of such injury or sickness, the Insured is completely

unable to engage in his regular occupation."

Plaintiff's "Application for Insurance" shows his "Occupation and Description

of Duties" to be "General and Vascular Surgery"; and elsewhere in the

Application under "Occupation," it specifies "Physician-General

Surgeon/Vascular Surgeon." The amendment defining the term "Total

Disability" is in two parts, one dealing with insureds under the age of sixty-five,

and the other with insureds over that age. The first of these parts, here

applicable, merely repeats the provision as stated in the Policy itself: " 'Total

Disability' means that, as a result of such injury or sickness, the Insured is

unable to perform the duties of his regular occupation."

The explanatory letter consists of a printed form with a blank to be filled in

when the Policy is issued to a particular insured. In the following quotation

from this letter, the words filled into that blank are emphasized:

10

During

the initial period of disability, total disability is defined as the inability of the

insured to perform the duties of his regular occupation due to injury or sickness.

When the insured is engaged in a specialty, such as General Surgery-Vascular

Surgery and is unable because of injury or sickness to perform the duties of his

specialty, we consider him to be totally disabled. This definition is applicable until

you reach the age of sixty-five.

11

In summary: For a claimant under sixty-five years of age, the Policy requires

only that it be established that when a claim is made the claimant is under the

care of a licensed physician and is suffering from an illness, first manifested

while the Policy was in force, which renders the claimant "unable to perform

the duties of his regular occupation." For a claimant engaged in a specialty, that

specialty is considered to be his or her "regular occupation."Plaintiff's Activities

12

In June 1973, three years into his surgical practice, Plaintiff purchased the

Policy. He was then 36 years old. The Policy was not issued in connection with

any hospital or clinic where the Plaintiff performed surgery; rather it was a

private policy purchased by the Plaintiff. On the Application for Insurance

(which, as we have noted, was made a part of the Policy itself), he stated his

occupation to be "Physician-general surgeon/vascular surgeon."

13

Plaintiff practiced surgery continuously until 1986. Then, at age 50, he began to

experience premature atrial contractions, and took a "sabbatical" from surgery,

which lasted for two years and two months. In 1988 he returned to the practice

of surgery, specializing in breast cancer surgery. In 1989 he was diagnosed as

having atrial fibrillation, paroxysms of rapid irregular heartbeat causing

shortness of breath. In September of that year-due to this heart condition-he

again left surgery and secured a position as Acting Medical Director at Choice

Care, an HMO. He served in that position for two years and four months,

resigning effective January 3, 1992. During his tenure at Choice Care, his heart

condition worsened. From 1989 when the condition was first diagnosed until

1993, Plaintiff was under the care of cardiologist Halbert Feinberg, M.D. Since

then, he has been under the care of cardiologist Alan Rosenberg, M.D., who

once hospitalized him in an unsuccessful attempt to convert his heart to a

normal rhythm. Plaintiff asserts that "[b]y November 1994, the frequency and

severity of the attacks had progressed to the point where I realized I could

never return to surgery."

14

On January 25, 1995, when 58 years old, Plaintiff applied to the Company for

total disability benefits due to sickness. On the Attending Physician's

Statement, one of the documents required by the Company to be submitted with

this claim, Dr. Rosenberg described Plaintiff's medical condition, and stated

that he was "totally disabled." The Company, apparently finding in the Policy a

latent requirement that the insured be engaged in his or her regular occupation

at the time of a claim, denied Plaintiff's claim solely on that ground. At page 6

of its brief to this Court it states that "Paul Revere denied Plaintiff's claim, since

Plaintiff was not engaged in, or regularly occupied as, a general/vascular

surgeon at the time of claim...."

New York Insurance Law

15

In this diversity case, New York substantive law controls. Erie R. Co. v.

Tompkins, (1938) 304 U.S. 64, 78-80, 58 S.Ct. 817, 82 L.Ed. 1188.

16

As to New York insurance law, "In New York State, an insurance contract is

interpreted to give effect to the intent of the parties as expressed in the clear

language of the contract. If the provisions are clear and unambiguous, courts

are to enforce them as written. However, if the policy language is ambiguous,

particularly the language of an exclusion provision, the ambiguity must be

interpreted in favor of the insured." Village of Sylvan Beach v. Travelers

Indemnity Co., (2d Cir.1995) 55 F.3d 114, 115. See also Blasbalg v.

Massachusetts Casualty Ins. Co., (E.D.N.Y.1997) 962 F.Supp. 362, 368

("Disability policies are to be given practical application, consistent with New

York's declared policy that 'the terms of an insurance policy will receive the

construction most favorable to the insured.' ") citing Niccoli v. Monarch Life

Ins. Co., (Sup.Ct. Kings Co.1972) 70 Misc.2d 147, 332 N.Y.S.2d 803, 806,

aff'd, 45 A.D.2d 737, 356 N.Y.S.2d 677 (2d Dep't 1974), aff'd, 36 N.Y.2d 892,

372 N.Y.S.2d 645, 334 N.E.2d 594 (1975); Magee v. Paul Revere Life Ins. Co.,

(E.D.N.Y.1997) 172 F.R.D. 647, 652-53 (The court refused to consider the

Company's claim that a policy similar to the one at bar had been obtained by

fraud because: "Defendant [had] an opportunity to insert an incontestability

clause enabling it to contest fraudulent misstatements after two years .... [and]

Defendant ... did not avail itself of the opportunity."); Monarch Life Ins. Co. v.

Brown, (1st Dep't 1987) 125 A.D.2d 75, 512 N.Y.S.2d 99, 103 ("A policy

which is subject to more than one reasonable interpretation must be interpreted

to resolve the ambiguity against the insurer and in favor of the policyholder. It

is black letter law that if the insurer intends to exclude liability, such intention

must be clearly expressed." (Emphasis ours.)).

17

Guided by such "black letter law," a finder of fact applying the provisions of

the Policy, accepting all Plaintiff's assertions as true and making all reasonable

inferences in his favor could conclude that Plaintiff was entitled to prevail on

his assertion that he was suffering from a sickness which had "first manifest[ed]

itself while [the Policy was] in force" and that at the time of making his claim,

he was under the "regular and personal attendance of a licensed physician" who

found him to be "totally disabled." It follows that summary judgment in the

Company's favor cannot stand.

18

In coming to an opposite conclusion, the District Court cited two cases

Kunstenaar v. Connecticut Gen. Life Ins. Co., (2d Cir.1990) 902 F.2d 181 and

Brumer v. National Life of Vermont, (E.D.N.Y.1995) 874 F.Supp. 60,

reconsideration denied, 899 F.Supp. 120, aff'd by summary order sub nom.

Brumer v. Paul Revere Life Ins. Co., (2d Cir.1998) 133 F.3d 906. The court

also referred to "many other cases." Neither of the two cited cases is here

applicable. In Kunstenaar, the policy-unlike the one before us-was not a

personal policy, but one purchased by the claimant's employer, which provided

that it would terminate at "Termination of Employment," and would cover only

disability commencing before such Termination. The claimant was denied

benefits because he was found not to have been disabled before Termination.

Brumer dealt with policies which specifically required a policyholder claiming

disability to establish that he or she was actively engaged in his or her regular

occupation "at the time such disability begins." 874 F.Supp. at 62. As we have

seen, the Policy before us has no language suggesting such a requirement. With

respect to the "many other cases" to which the District Court referred, assuming

them to have been the ones the Company has cited to us, none is here

applicable. Not one of them deals with an insurance policy even remotely like

the one before us, which so far as concerns the timing of a sickness suffered by

an insured, requires only that his or her "sickness first manifest[ed] itself while

this [P]olicy [was] in force."

Conclusion

19

We set aside the grant of summary judgment in favor of the Company, and

remand for further proceedings not inconsistent herewith.

Honorable Whitman Knapp, of the United States District Court for the

Southern District of New York, sitting by designation

You might also like

- Brenda M. Coppard, Helene Lohman Introduction To Splinting A Clinical Reasoning and Problem-Solving ApproachDocument539 pagesBrenda M. Coppard, Helene Lohman Introduction To Splinting A Clinical Reasoning and Problem-Solving ApproachAndrei R Lupu75% (8)

- Holistic Health and Healing PDFDocument338 pagesHolistic Health and Healing PDFdoctorshere100% (5)

- Ph&x152nix Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Connelly, 188 F.2d 462, 3rd Cir. (1951)Document7 pagesPh&x152nix Mut. Life Ins. Co. v. Connelly, 188 F.2d 462, 3rd Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 15 - Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp., vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda v. LeuterioDocument4 pages15 - Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp., vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda v. LeuterioClaudine Christine A. VicenteNo ratings yet

- Second DivisionDocument9 pagesSecond DivisionYollaine GaliasNo ratings yet

- Second DivisionDocument7 pagesSecond DivisionJoan MacedaNo ratings yet

- GrepaLife v. CADocument14 pagesGrepaLife v. CAmonagbayaniNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of AppealsDocument8 pagesGreat Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of AppealsJaja Ordinario Quiachon-AbarcaNo ratings yet

- Cordova v. Scottsdale Ins Co, 4th Cir. (2001)Document11 pagesCordova v. Scottsdale Ins Co, 4th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Grepalife Vs CADocument8 pagesGrepalife Vs CAChiara JayneNo ratings yet

- Philippine Supreme Court Jurisprudence Year 1999 October 1999 DecisionsDocument4 pagesPhilippine Supreme Court Jurisprudence Year 1999 October 1999 Decisionsbenjo2001No ratings yet

- GrepaLife v. CA For 7in TabDocument18 pagesGrepaLife v. CA For 7in TabWilfredo MolinaNo ratings yet

- Grepalife vs. CA. 303 SCRA 113 October 13 1999Document5 pagesGrepalife vs. CA. 303 SCRA 113 October 13 1999wenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- Insu GrepaDocument6 pagesInsu Grepacindy mateoNo ratings yet

- United States Fire Insurance Company, As Assignee and Subrogee of Its Insured, South Nassau Communities Hospital v. General Reinsurance Corporation, 949 F.2d 569, 2d Cir. (1991)Document11 pagesUnited States Fire Insurance Company, As Assignee and Subrogee of Its Insured, South Nassau Communities Hospital v. General Reinsurance Corporation, 949 F.2d 569, 2d Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ins 418 - Life and Health Insurance Slide NotesDocument53 pagesIns 418 - Life and Health Insurance Slide Notesolaifa TomisinNo ratings yet

- Digest 2 Insurance 4Document5 pagesDigest 2 Insurance 4Richelle GraceNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Vs CADocument6 pagesGreat Pacific Vs CAWindy RoblesNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Respondents GA Fortun & Associates Noel S. BejaDocument9 pagesPetitioner Respondents GA Fortun & Associates Noel S. Bejalorfes rickpatNo ratings yet

- Grepalife Vs CADocument8 pagesGrepalife Vs CACAJNo ratings yet

- St. Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Company v. The Medical Protective Company, 691 F.2d 468, 10th Cir. (1982)Document4 pagesSt. Paul Fire & Marine Insurance Company v. The Medical Protective Company, 691 F.2d 468, 10th Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- (B. Parties To The Contract) Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals, 316 SCRA 677, G.R. No. 113899 October 13, 1999Document9 pages(B. Parties To The Contract) Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals, 316 SCRA 677, G.R. No. 113899 October 13, 1999Alexiss Mace JuradoNo ratings yet

- Middle Georgia Neurological Specialists, P.C., Cross-Appellants v. Southwestern Life Insurance Company, Cross-Appellee, 967 F.2d 536, 11th Cir. (1992)Document6 pagesMiddle Georgia Neurological Specialists, P.C., Cross-Appellants v. Southwestern Life Insurance Company, Cross-Appellee, 967 F.2d 536, 11th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitDocument13 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Fourth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Digest - Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp Vs Ca 316 Scra 677Document4 pagesDigest - Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp Vs Ca 316 Scra 677api-263595583No ratings yet

- Lelia Grace Fisher v. The United States Life Insurance Company in City of New York, A Body Corporate, 249 F.2d 879, 4th Cir. (1957)Document9 pagesLelia Grace Fisher v. The United States Life Insurance Company in City of New York, A Body Corporate, 249 F.2d 879, 4th Cir. (1957)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Ninth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shirley B. Suskind v. North American Life & Casualty Company, 607 F.2d 76, 3rd Cir. (1979)Document13 pagesShirley B. Suskind v. North American Life & Casualty Company, 607 F.2d 76, 3rd Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Phil E. White v. The North American Accident Insurance Company, A Corporation, 316 F.2d 5, 10th Cir. (1963)Document3 pagesPhil E. White v. The North American Accident Insurance Company, A Corporation, 316 F.2d 5, 10th Cir. (1963)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tan V CADocument6 pagesTan V CAMara ClaraNo ratings yet

- Cases of Insurable InterestDocument10 pagesCases of Insurable InterestVanny Joyce BaluyutNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda V. LeuterioDocument3 pagesGreat Pacific Life Assurance Corp. vs. Court of Appeals and Medarda V. LeuterioKristine Hipolito SerranoNo ratings yet

- 36 - Great Pacific Life v. CADocument1 page36 - Great Pacific Life v. CAperlitainocencioNo ratings yet

- Velez Gomez v. SMA Life Assurance, 8 F.3d 873, 1st Cir. (1993)Document8 pagesVelez Gomez v. SMA Life Assurance, 8 F.3d 873, 1st Cir. (1993)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- American Progressive Life and Health Insurance Company of New York v. James Corcoran, As Superintendent of Insurance of The State of New York, 715 F.2d 784, 2d Cir. (1983)Document5 pagesAmerican Progressive Life and Health Insurance Company of New York v. James Corcoran, As Superintendent of Insurance of The State of New York, 715 F.2d 784, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Life Assurance vs. CA (Case)Document6 pagesGreat Pacific Life Assurance vs. CA (Case)jomar icoNo ratings yet

- Insurance DigestDocument8 pagesInsurance DigestNrnNo ratings yet

- 123713-1999-Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. v. Court20231215-12-Ilkg7sDocument9 pages123713-1999-Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. v. Court20231215-12-Ilkg7sARCHIE AJIASNo ratings yet

- Insurance Case 1 11 and 15Document7 pagesInsurance Case 1 11 and 15Jeru SagaoinitNo ratings yet

- Tan v. CA - Rescission of The Contract of Insurance: 174 SCRA 403 FactsDocument38 pagesTan v. CA - Rescission of The Contract of Insurance: 174 SCRA 403 FactsacesmaelNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 113899, October 13, 1999Document9 pagesG.R. No. 113899, October 13, 1999Email DumpNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Barrameda vs. ECC, GR L-50142, August 17, 1981Document4 pagesBarrameda vs. ECC, GR L-50142, August 17, 1981Judel MatiasNo ratings yet

- 135747-1983-Ng Gan Zee v. Asian Crusader Life AssuranceDocument5 pages135747-1983-Ng Gan Zee v. Asian Crusader Life AssuranceJessica Magsaysay CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- New India Assusrance vs. Akshoy Kumar PaulDocument6 pagesNew India Assusrance vs. Akshoy Kumar PaulAvneet KaurNo ratings yet

- Joseph H. Beaman v. Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company, 369 F.2d 653, 4th Cir. (1966)Document5 pagesJoseph H. Beaman v. Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company, 369 F.2d 653, 4th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Musngi V West Coast LifeDocument1 pageMusngi V West Coast LifeMarkonitchee Semper FidelisNo ratings yet

- O.F. Santos & P.C. Nolasco For Petitioners. Ferry, de La Rosa and Associates For Private RespondentDocument5 pagesO.F. Santos & P.C. Nolasco For Petitioners. Ferry, de La Rosa and Associates For Private Respondentwenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. V CA and MedardaDocument5 pagesGreat Pacific Life Assurance Corp. V CA and MedardaEstelle Rojas TanNo ratings yet

- Musngi V West Coast LifeDocument1 pageMusngi V West Coast LifemendozaimeeNo ratings yet

- Julie M. Winchester v. Prudential Life Insurance Company of America, and Life Insurance Company of North America, 975 F.2d 1479, 10th Cir. (1992)Document12 pagesJulie M. Winchester v. Prudential Life Insurance Company of America, and Life Insurance Company of North America, 975 F.2d 1479, 10th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Insurance Cases For WednesdayDocument13 pagesInsurance Cases For WednesdayYolanda Janice Sayan FalingaoNo ratings yet

- American International Assurance Co LTD V See Ah Yu: 566 (1996) 3 CLJ Current Law JournalDocument7 pagesAmerican International Assurance Co LTD V See Ah Yu: 566 (1996) 3 CLJ Current Law JournalNick TanNo ratings yet

- Audrey Shaps v. Provident Life & Accident Insurance Company, Provident Life and Casualty Insurance Company, A Foreign Corporation, 244 F.3d 876, 11th Cir. (2001)Document16 pagesAudrey Shaps v. Provident Life & Accident Insurance Company, Provident Life and Casualty Insurance Company, A Foreign Corporation, 244 F.3d 876, 11th Cir. (2001)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NG Gan Zee V Asia Crusader Life Assurance CorpDocument4 pagesNG Gan Zee V Asia Crusader Life Assurance CorpEstelle Rojas TanNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 InsuranceDocument33 pagesAssignment 3 InsuranceKing AlduezaNo ratings yet

- NG Gan Zee Vs Asian CrusaderDocument3 pagesNG Gan Zee Vs Asian CrusaderWatz RebanalNo ratings yet

- Policy Case DigestsDocument12 pagesPolicy Case DigestsCarla January OngNo ratings yet

- Emilio Tan, Juanito Tan, Alberto Tan and Arturo TAN, Petitioners, vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS and THE Philippine American Life Insurance COMPANY, RespondentsDocument7 pagesEmilio Tan, Juanito Tan, Alberto Tan and Arturo TAN, Petitioners, vs. THE COURT OF APPEALS and THE Philippine American Life Insurance COMPANY, RespondentsYollaine GaliasNo ratings yet

- Life, Accident and Health Insurance in the United StatesFrom EverandLife, Accident and Health Insurance in the United StatesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Document24 pagesParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Baptist SouvenirDocument70 pagesBaptist SouvenirPrimalogue0% (1)

- Medicine Herb and Herbal Pills PowerPoint Templates StandardDocument4 pagesMedicine Herb and Herbal Pills PowerPoint Templates StandardAlena StuparNo ratings yet

- Pharma Computation Assignment PDFDocument2 pagesPharma Computation Assignment PDFKasnhaNo ratings yet

- Idrn12jxl0lsldhq3sdljlfkDocument2 pagesIdrn12jxl0lsldhq3sdljlfkdevanshupal0101No ratings yet

- Assessing Normal and Abnormal Pregnancy From 4-10 Weeks: Monique HaakDocument49 pagesAssessing Normal and Abnormal Pregnancy From 4-10 Weeks: Monique Haakjen marbunNo ratings yet

- Nursing Practice LLLDocument10 pagesNursing Practice LLLKimberly ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Portofolio Mata Kuliah Bahasa Inggris Dalam Keperawatan IiDocument5 pagesPortofolio Mata Kuliah Bahasa Inggris Dalam Keperawatan IidiahayumustikaNo ratings yet

- TanongDocument19 pagesTanongViena Mae MaglupayNo ratings yet

- Joshi2008 PDFDocument8 pagesJoshi2008 PDFNguyễn Đức Tri ThứcNo ratings yet

- Mapeh Grade 6 4TH QDocument6 pagesMapeh Grade 6 4TH QSaida Bautil SubradoNo ratings yet

- Surgical Site InfectionDocument14 pagesSurgical Site InfectionSri AsmawatiNo ratings yet

- Paracetamol - DSDocument3 pagesParacetamol - DSEnoch LabianoNo ratings yet

- Microbial Limit TestDocument33 pagesMicrobial Limit TestSurendar KesavanNo ratings yet

- Obat RacikDocument4 pagesObat RacikBimo Aryo TejoNo ratings yet

- How Patent Law Reform Can Improve Affordability AnDocument5 pagesHow Patent Law Reform Can Improve Affordability AnHopewell MoyoNo ratings yet

- Referral Letter To Hsijb Ortho Onco JurimiDocument2 pagesReferral Letter To Hsijb Ortho Onco JurimiLee Chee SengNo ratings yet

- (1160) Pharmaceutical Calculations in Pharmacy PracticeDocument25 pages(1160) Pharmaceutical Calculations in Pharmacy Practiceprissila prindaniNo ratings yet

- LEC 4 Antibody Screening & IdentificationDocument5 pagesLEC 4 Antibody Screening & IdentificationTintin MirandaNo ratings yet

- Introducing The Leadership in Enabling Occupation (LEO) ModelDocument6 pagesIntroducing The Leadership in Enabling Occupation (LEO) ModelPatricia Jara Reyes100% (1)

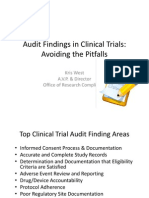

- Audit Findings in Clinical TrialsDocument21 pagesAudit Findings in Clinical TrialsMohit SinghNo ratings yet

- Manual For Inc Ac100 200Document32 pagesManual For Inc Ac100 200Ruben Dario Arregoces Miranda100% (1)

- Zinc Oxide - Zno - PubchemDocument91 pagesZinc Oxide - Zno - PubchemWiri Resky AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Stretch Break For Computer UsersDocument1 pageStretch Break For Computer UsersDjordje SavićNo ratings yet

- Syllabus BME 411Document5 pagesSyllabus BME 411someonefromsomwhere123No ratings yet

- Openmark 5000 User ManualDocument76 pagesOpenmark 5000 User ManualAzul VP0% (1)

- Darley Et Al-1969-Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing ResearchDocument24 pagesDarley Et Al-1969-Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing ResearchtijitonaNo ratings yet

- Edentulism and Comorbid FactorsDocument10 pagesEdentulism and Comorbid FactorsDaniel AnguloNo ratings yet

- Reproductive PhysiologyDocument40 pagesReproductive PhysiologyBaiq Trisna Satriana100% (1)