Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 85

Chapter 85

Uploaded by

Sri HariCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Smile Again CaseDocument28 pagesSmile Again CaseKeshav NautiyalNo ratings yet

- MCQs in DentistryDocument135 pagesMCQs in Dentistrysam4sl98% (85)

- Justice in Oral Health CareDocument371 pagesJustice in Oral Health CareSara Maria Menck SangiorgioNo ratings yet

- What Doctors Dont Tell You - The Dental HandbookDocument124 pagesWhat Doctors Dont Tell You - The Dental HandbookSeeTohKevin100% (1)

- Brushing and Flossing The Teeth of Conscious and Unconscious Client Procedure ChecklistDocument3 pagesBrushing and Flossing The Teeth of Conscious and Unconscious Client Procedure ChecklistMONIQUE GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Ubc ApplicationDocument3 pagesUbc Applicationapi-508959687No ratings yet

- Surgeon General'S Perspectives: Oral Health: The Silent EpidemicDocument2 pagesSurgeon General'S Perspectives: Oral Health: The Silent EpidemicArida BitanajshaNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument3 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Oral Health in AmericaDocument332 pagesOral Health in AmericaAdrian GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument3 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Policy Healthcare ReformDocument3 pagesPolicy Healthcare Reformsonia_groff6256No ratings yet

- The Oral Health Information Suite (OHIS) : Its Use in The Management of Periodontal DiseaseDocument12 pagesThe Oral Health Information Suite (OHIS) : Its Use in The Management of Periodontal DiseasejemmysenseiNo ratings yet

- Women'S: A Literature Review OnDocument14 pagesWomen'S: A Literature Review OnAudrey Kristina MaypaNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Nixon-Health Policy PaperDocument5 pagesNixon-Health Policy Paperapi-291204444No ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Leake2008 PDFDocument9 pagesLeake2008 PDFjhon killNo ratings yet

- Klein1938 CPODDocument16 pagesKlein1938 CPODAlejandro RuizNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint Synthesis Final DraftDocument5 pagesViewpoint Synthesis Final Draftapi-589364430No ratings yet

- Boyce, 2021Document32 pagesBoyce, 2021Matheus Souza Campos CostaNo ratings yet

- Professional: Why Do We Need An Oral Health Care Policy in Canada?Document11 pagesProfessional: Why Do We Need An Oral Health Care Policy in Canada?petewin0123No ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Dental Crisis in America: The Need To Address CostsDocument52 pagesSenate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Dental Crisis in America: The Need To Address CostsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The CareDocument5 pagesDental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The Carecarlina_the_bestNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Universal Health CareDocument8 pagesThesis Statement On Universal Health Caretammylacyarlington100% (2)

- Intro To Biological DentistryDocument7 pagesIntro To Biological DentistryFelipe LazzarottoNo ratings yet

- Economics Health CareDocument79 pagesEconomics Health CareLuiz CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Wahl 2006Document5 pagesWahl 2006anas dkaliNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries PandemicDocument5 pagesDental Caries PandemicKarla González GNo ratings yet

- Essay BlogDocument7 pagesEssay BlogWilliam W. LeeNo ratings yet

- Dental Implant Failure: A Clinical Guide to Prevention, Treatment, and Maintenance TherapyFrom EverandDental Implant Failure: A Clinical Guide to Prevention, Treatment, and Maintenance TherapyThomas G. Wilson Jr.No ratings yet

- Aids DissertationDocument5 pagesAids DissertationCustomPaperWritersUK100% (1)

- Alginate ImpressionDocument60 pagesAlginate ImpressionNugraha AnggaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Oral Health Conditions in Older People: OriginalarticleDocument8 pagesEpidemiology of Oral Health Conditions in Older People: OriginalarticleWJNo ratings yet

- BMC Oral Health: Biotech and Biomaterials Research To Reduce The Caries EpidemicDocument7 pagesBMC Oral Health: Biotech and Biomaterials Research To Reduce The Caries EpidemicKranti PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureDocument10 pagesOral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureJASPREETKAUR0410No ratings yet

- Periodicity DentalGuideDocument52 pagesPeriodicity DentalGuideSalam BataienehNo ratings yet

- State of DecayDocument8 pagesState of DecayWisdomToothOHANo ratings yet

- History of US Health Care System-Final ProjectDocument12 pagesHistory of US Health Care System-Final ProjectAntonio Abreu Jr.100% (1)

- Geriatric Oral Health Concerns A Dental Public Hea PDFDocument6 pagesGeriatric Oral Health Concerns A Dental Public Hea PDFفواز نميرNo ratings yet

- Akikut - Pride PaperDocument15 pagesAkikut - Pride Paperapi-486142180No ratings yet

- Planificacion en VIDocument16 pagesPlanificacion en VIGaby Tipan JNo ratings yet

- Health Care Crisis Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesHealth Care Crisis Thesis Statementsdeaqoikd100% (1)

- Dentistry in Post COVIDDocument3 pagesDentistry in Post COVIDsagrika groverNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Kindness: Reforming The Culture of HealthcareDocument7 pagesIntelligent Kindness: Reforming The Culture of Healthcarefarnaz_2647334No ratings yet

- Covid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint DisordersDocument5 pagesCovid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint Disordersbotak berjamaahNo ratings yet

- Final TintinDocument5 pagesFinal TintinRenier FloresNo ratings yet

- Universal Health Care Research PaperDocument5 pagesUniversal Health Care Research Paperwftvsutlg100% (1)

- Dental Amalgam and Mercury in Dentistry: Invited ReviewDocument11 pagesDental Amalgam and Mercury in Dentistry: Invited ReviewRichard Serrano Garcia OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., American Academy of Political and Social Science The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social ScienceDocument9 pagesSage Publications, Inc., American Academy of Political and Social Science The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Scienceassaini carinta padangNo ratings yet

- Rough Draft Health Care 4Document10 pagesRough Draft Health Care 4long_paula1No ratings yet

- SJ BDJ 2008Document1 pageSJ BDJ 2008idurdNo ratings yet

- Letter To Mrs. Clinton-May 1993-By Trudy Attenberg-Face ForwardDocument2 pagesLetter To Mrs. Clinton-May 1993-By Trudy Attenberg-Face ForwardNeil GillespieNo ratings yet

- Managementofedentulous Patients: Damian J. Lee,, Paola C. SaponaroDocument13 pagesManagementofedentulous Patients: Damian J. Lee,, Paola C. Saponarosnehal jaiswalNo ratings yet

- The Young Professions Australia Roundtable 2003 Achieving A Sustainable Future A Dental PerspectiveDocument7 pagesThe Young Professions Australia Roundtable 2003 Achieving A Sustainable Future A Dental PerspectiveAhmed GendiaNo ratings yet

- ND Annual: Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology ReviewDocument12 pagesND Annual: Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology Reviewsulai701280No ratings yet

- Oral Diseases - 2023 - JainDocument7 pagesOral Diseases - 2023 - JainGita PratamaNo ratings yet

- IMPORTANTE Promoc Educac Salud Adult MayorDocument4 pagesIMPORTANTE Promoc Educac Salud Adult MayorJorge BalzanNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics Public Health DentistryDocument5 pagesThesis Topics Public Health DentistryKristen Flores100% (2)

- Dental EducationDocument14 pagesDental EducationiwanntataNo ratings yet

- U O H S P 2016-2020: Topia RAL Ealth Urveillance LANDocument15 pagesU O H S P 2016-2020: Topia RAL Ealth Urveillance LANNoor Muddassir KhanNo ratings yet

- Gallium and Indium ScanDocument1 pageGallium and Indium ScanSri HariNo ratings yet

- 30 37Document8 pages30 37Sri HariNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document6 pagesLesson 1Sri HariNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Radionuclide ImagingDocument5 pagesChapter 2 Radionuclide ImagingSri HariNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute and Chronic Retention in MenDocument52 pagesManagement of Acute and Chronic Retention in MenSri HariNo ratings yet

- Usg in UrologyDocument25 pagesUsg in UrologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Renogram GuidelineDocument14 pagesRenogram GuidelineSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghDocument9 pagesContrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghSri HariNo ratings yet

- Uro DynamicsDocument64 pagesUro DynamicsSri HariNo ratings yet

- Intraluminal Navigation Through Any Hollow Viscus Is PossibleDocument3 pagesIntraluminal Navigation Through Any Hollow Viscus Is PossibleSri HariNo ratings yet

- Uro Dynamics 1Document22 pagesUro Dynamics 1Sri HariNo ratings yet

- UroflowDocument41 pagesUroflowSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Media: Dr.R.Abhiman Gautam, MCH Urology Prof - DR.RK Unit Stanley Medical CollegeDocument18 pagesContrast Media: Dr.R.Abhiman Gautam, MCH Urology Prof - DR.RK Unit Stanley Medical CollegeSri HariNo ratings yet

- Xray AbdomenDocument22 pagesXray AbdomenSri HariNo ratings yet

- Intravenous Radiographic Contrast Induced Adverse Reactions - Their Causes, Prevention and Relief MeasuresDocument7 pagesIntravenous Radiographic Contrast Induced Adverse Reactions - Their Causes, Prevention and Relief MeasuresSri HariNo ratings yet

- CT Angiography in UrologyDocument2 pagesCT Angiography in UrologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced NephropathyDocument2 pagesContrast Induced NephropathySri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Arteriography: Reasons Not As A Preliminary Screening ToolDocument3 pagesContrast Arteriography: Reasons Not As A Preliminary Screening ToolSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghDocument9 pagesContrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghSri HariNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Performa For Registration of Subject For DissertationDocument21 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Performa For Registration of Subject For DissertationSri HariNo ratings yet

- Clean Intermittent Catheterization (CIC) : IndicationsDocument2 pagesClean Intermittent Catheterization (CIC) : IndicationsSri HariNo ratings yet

- Impact of Endometrial Preparation Protocols For Frozen Embryo Transfer On Live Birth RatesDocument8 pagesImpact of Endometrial Preparation Protocols For Frozen Embryo Transfer On Live Birth RatesSri HariNo ratings yet

- Captopril Renography: Physiologic Principle - Loss of Preferential Vasoconstriction of The EfferentDocument3 pagesCaptopril Renography: Physiologic Principle - Loss of Preferential Vasoconstriction of The EfferentSri HariNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyDocument5 pagesEuropean Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Mccormick: Michael J. CoughlinDocument1 pageMccormick: Michael J. CoughlinSri HariNo ratings yet

- Access SheathDocument22 pagesAccess SheathSri HariNo ratings yet

- Maternal Mortality: Liliana Carvajal Vibeke Oestreich Nielsen Armando H. SeucDocument38 pagesMaternal Mortality: Liliana Carvajal Vibeke Oestreich Nielsen Armando H. SeucSri HariNo ratings yet

- 03 A025 5123Document13 pages03 A025 5123Sri HariNo ratings yet

- History of Articulators Part 1 2004Document13 pagesHistory of Articulators Part 1 2004ayduggal100% (4)

- Biomimetic AllemanDocument6 pagesBiomimetic AllemanAlireza RaieNo ratings yet

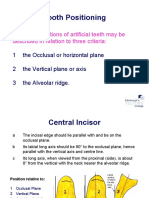

- Tooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaDocument19 pagesTooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaCherine SnookNo ratings yet

- Ahead FPD QuesDocument11 pagesAhead FPD QuesMostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- Cephalometric Distintion of Class II Division 2Document8 pagesCephalometric Distintion of Class II Division 2Diego SolaqueNo ratings yet

- KariesDocument4 pagesKariesSherlocknovNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene InstructionsDocument2 pagesOral Hygiene Instructionstepokpantat100% (1)

- Malkinson Et Al. 2012Document15 pagesMalkinson Et Al. 2012Nawaf RuwailiNo ratings yet

- Kep NursewndDocument18 pagesKep NursewndUntung Edi SaputraNo ratings yet

- SPSC 2018 Paper Type ADocument8 pagesSPSC 2018 Paper Type AMeenaNo ratings yet

- BIO C Repair With For Horizontal Root Fracture PDFDocument5 pagesBIO C Repair With For Horizontal Root Fracture PDFDaniel Vivas0% (1)

- Cementoblastoma and Periapical Cemento-Osseous DysplasiaDocument15 pagesCementoblastoma and Periapical Cemento-Osseous DysplasiaHessa AloliwiNo ratings yet

- Prost Ho Don TicsDocument172 pagesProst Ho Don Ticsسماح صلاحNo ratings yet

- Smile Arc Protection Part 2Document4 pagesSmile Arc Protection Part 2M.Laura100% (1)

- Annual Review of Selected ScientificDocument50 pagesAnnual Review of Selected Scientificpasber26No ratings yet

- Stability and RetentionDocument8 pagesStability and RetentionlizetNo ratings yet

- CHN Compre Exm 1Document8 pagesCHN Compre Exm 1Roy Salvador100% (1)

- Gingival Biotype Classification, Assessment, and Clinical Importance: A ReviewDocument7 pagesGingival Biotype Classification, Assessment, and Clinical Importance: A ReviewKetherin LeeNo ratings yet

- Davidovitch1995 PDFDocument6 pagesDavidovitch1995 PDFRahulLife'sNo ratings yet

- Dental Clinic (Job Description)Document10 pagesDental Clinic (Job Description)A'ihNo ratings yet

- Friday June 18, 2010 LeaderDocument47 pagesFriday June 18, 2010 LeaderSurrey/North Delta LeaderNo ratings yet

- Test - 10 Root (Radicular) CystsDocument5 pagesTest - 10 Root (Radicular) CystsIsak ShatikaNo ratings yet

- Project Practicum PresentationDocument37 pagesProject Practicum Presentationapi-652480224No ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Instruction Presentation Danielle WilsonDocument15 pagesOral Hygiene Instruction Presentation Danielle Wilsonapi-348271404No ratings yet

- Texas Medicaid and CHIP Provider FAQsDocument4 pagesTexas Medicaid and CHIP Provider FAQsangelina smithNo ratings yet

- Guide To BolognaDocument48 pagesGuide To Bolognamiry89No ratings yet

Chapter 85

Chapter 85

Uploaded by

Sri HariOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 85

Chapter 85

Uploaded by

Sri HariCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 85

Dental Insurance and Managed Care

in Periodontal Practice

Maxwell H. Anderson and S. Jerome Zackin

CHAPTER OUTLINE

HISTORY

Health Insurance

Dental Insurance

PRINCIPLES

CLASSIFICATION OF PROGRAMS

BENEFITS DESIGN

Time Limits

Balance Billing

HISTORY

Health Insurance

Health insurance emerged in the United States (US) as the country

was emerging from the great depression in the 1930s. Most of the

original insurance programs were offered by hospital systems or

groups of physicians and included diagnostic and radiographic

services, as well as room and board while patients were hospitalized. Insurance plans did not have great penetration in the US until

World War II.

World War II created a huge demand for labor in the US. The

labor force was significantly reduced by the Armed Forces as the

US fought the war. The posters of Rosie the Riveter were produced during this period as women moved into the wartime production economy to fulfill the needs for war materials in a depleted

labor market. At the same time, the US had frozen wartime wages

and prices. This wage freeze was put in place to prevent individuals

or groups from leveraging the shortage of goods and labor for

personal gain, thereby hurting the wartime production efforts.

To compete for labor in these wage-restricted markets, employers began to offer nonwage compensation, and health insurance

was a popular total compensation enticement to work for an

employer. The effects of this employment-based health insurance

system are still in place today, although its relevance to the current

economy and health systems is increasingly debated.

Some progressive employers in World War II even opened their

own clinics. This was seen as useful from a number of perspectives.

Coordination of Benefits

Alternate Benefits

Exclusions

Adjudication

Attachments

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

MOST COMMON ERRORS

CONCLUSION

In some cases, workers did not need to leave their workplace to

receive medical services, thereby reducing the amount of time lost

from production. The cost of the health system was also under the

direct control of the employer. The Kaiser Health system of today

is the evolutionary prodigy of Henry Kaisers vision for the health

care of the individuals employed in his shipyards.

Dental Insurance

Dental insurance has existed in one form or another for a substantial time. Figure 85-1 shows a proposal for a dental capitation plan

from 1850.

Formally, dental insurance in the US began in 1954 as collaboration between the International Longshoreman and Warehouse

Union (ILWU) and the three state dental associations on the West

coast. The ILWU suggested to the Washington, Oregon and California State Dental Associations that they help design a program

for the ILWUs children or following the World War II Kaiser

example, the ILWU would open its own clinics.2 At the time of

this collaboration, dental care was considered uninsurable. Caries

and periodontal diseases were pandemic, and edentulism was an

expected outcome by the time individuals reached middle age3

(Figures 85-2 and 85-3). Life expectancy at birth was 60 years.5

Against this backdrop, three dental service corporations were

formed in Washington, Oregon, and California within several

months of each other.

There is some debate as to whether dental benefits coverage is

insurance or prepaid health care. Typically, insurance covers large

costs for events that occur infrequently (e.g., fire insurance,

768.e43

768.e44

PART 9 Complementary Topics

THE DAILY REPORTER

Baton Rouge, La., Tuesday Morning, March 5, 1850.

ADDRESS:

To the Heads of Families, Guardians, and the Superiors of Institutions

LONG AND PRACTICAL experience prompts us to believe that the teeth of man can

be preserved to advanced age of life, provided he will give them that care and attention which their

use and importance demands. It is our object then to reform the state and bad condition of the teeth

and remove in a great measure the evils and sufferings of thousand, and more particularly the rising

generation.

Our desire is to impress the young with a sense of the worth and usefulness of beautiful and

sound teeth, and to accomplish this for the mutual good of all, we propose the following plan, viz:

To open a subscription book by which families can be served throughout the year, having all

operation performed appertaining to Dentistry in the most skillful manner for the following prices, viz:

For adults......................................................................................................................$15.00

For children from 10 to 16...............................................................................................10.00

For children from 5 to 10...................................................................................................5.00

In addition to the above allow us to mention some very important obversations which should be

brought to your consideration. It is the various periods in the formation of the teeth which require the

strictest observance and attention of some experienced and skillful dentist, and those periods in life

are first, the infantile disease caused by inattention in teething and to facilitate matters at this critical

time of life

Secondly, to the attention of the loss of the first denition and the proper arrangement and

treatment of the second or permanent set, and thirdly, the treatment they may require in a more

advanced time, for the importance of the teeth is such that they deserve our utmost care and

attention as well with respect to the preservation of them when in their healthy state, as to the

method of curing them when diseased. They required this attention. Not only for their preservation

as organs useful to the body, but also on account of their intimate connection with other parts, for

diseases of the teeth are apt to produce disease in the neighboring parts, frequently of very serious

consequences, and there is no doubt but that disease in the mouth often severely affect the constitution,

and are conducive to several diseases of the system, in fine many of you may be victims to these sad

misfortunes and know too well the miseries of bad teeth, and the importance of an early and judicious

attention to them, and such being the case many have been compelled to neglect them because they

could not afford the means for relief, consequently to the advantage of all we now adopt this plan, and

do most sincerely hope it will meet your approbation and gain your support.

Being permanently fixed at our office, where we have all the conveniences requisite, and where

due attention will be given to all the different branches in dentistry in the shortest notice.

Our subscription book is now open, and all those desirous of subscribing and will engage their

families, or single persons by the year will please call our office, corner of North Boulevard and Third

Street.

A.L. PLOUGH & SON

Baton Rouge, La.

Figure 85-1 Newspaper advertisement from 1850.

Periodontal distribution 1950s

35

Periodontal

30

15

10

5

0

Tooth loss

100

20

1944-1960 1971-1974 1978-1980 1986-1987 1988-1994

Figure 85-2 Decreasing incidence of caries in molar teeth. The probability

that an erupting molar tooth would be restored in the year after eruption.

% Population affected

Percent

25

Gingivitis

80

60

40

20

0

13 16 19 23 27 31 35 40 46 49 52 56 60

Age

Figure 85-3 Penetration by age of gingivitis, periodontal disease, and

tooth loss as recorded in 1950. (From Marshall-Day CD: J Periodontal Res

22:13, 1951.)

CHAPTER 85 Dental Insurance and Managed Care in Periodontal Practice

Current periodontal distribution

100

90

80

60

10% get 98%

50

40

Percent service

70

30

20

10

0

10

15

Percent of insured treated

20

Figure 85-4 Penetration of periodontal services rendered to an insured

population of approximately 2 million individuals. Treatments by general

practitioners and specialists were examined and include all periodontal

services, excluding implants.

automobile insurance). However, dental needs across large populations are uniform, and the costs are relatively small compared with

medical costs. The argument is actually one of perspective. For the

purchaser of dental services from a third-party payer, dental insurance is prepaid health care. The carrier or the purchaser assumes

the risk. The underwriting costs of dental care are very well known.

In fact, an employer with more than about 1000 employees will

probably be self-insured. That is, the employer will pay the benefits costs while paying a third party to adjudicate the claims and

manage the records. The employer assumes the risk, but actuaries

have determined, with great precision, what their costs will be for

the year. From the patients perspective, dental coverage spreads the

risk of incurring disease and its repair across a population and thus

acts as insurance.

Given the high incidence and prevalence of dentistrys two

primary diseases in the 1950s, dental insurance plans were written

to treat the entire population. At present, neither dental caries nor

periodontal diseases are pandemic, at least in populations covered

by commercial insurance. Using national data from both the second

National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES

II study)4 and dental insurance records5 (Figure 85-4), it is clear

that these diseases are sequestered in an increasingly smaller

number of individuals. The penetration of both diseases has been

declining for the past 50 years. This uneven distribution of disease

makes dentistry much more like risk insurance than when everyone

had dental diseases.1

PRINCIPLES

In principle when analyzing insurance by who assumes the payment

risk, there are only three major ways to provide dental benefits. In

traditional risk insurance, the dental insurance entity assumes the

risk and potential gains or losses from revenue spent or not spent

on treatment. This is the traditional view of dental insurance. A

less- [variation of the] traditional type of risk insurance is capitation or prepaid care (DHMO), in which the dentist is paid a fixed

amount per enrolled patient to provide a contractually specified

level of treatment. In this model the dentist assumes the risk.

The third type of dental payment is aptly called an administrative services contract (ASC). Employers, generally with 1000 or

768.e45

more employees, are self-insured and pay third-party administrators, dental services corporations, or insurance companies to provide

program management services. Employers have found that the

administrative services contractor has more expertise in this domain

and can perform these services better, faster, and cheaper than the

purchaser can self-administer these functions. These services generally include all the record keeping (administration) and adjudicative

practices (rules enforcement and professional determinations of the

extent of benefits), but there is no potential for a gain or loss on

the dental claims for the administrative company. For example,

regardless of whether a specific claim for services is approved or

denied by the ASC contractor, there is no impact on its revenues.

It is paid a flat administrative rate to manage these activities for

the self-insured business.

Within these three general insurance funding types, there are

numerous administrative strategies. These include full-service programs in which the administrative entity provides all the services

necessary to manage a dental plan. This involves suggesting and

developing plan designs, writing the services contracts, receiving

and keeping eligibility data, recruiting dentist networks, credentialing the dentists, and receiving, adjudicating, and paying claims for

services. There are variations on this theme, with a ratcheting back

of services until direct reimbursement is the remaining service. In

the most basic form of direct reimbursement, the administrator

manages only eligibility information, bookkeeping, and payment of

submitted claims. No professional review services are rendered (see

later discussion).

It should be noted that the purchasers of health care services make the

final decisions about what they will and will not put in their benefits

plans. Dental insurance companies advise purchasers about the costs of

individual benefits, but ultimately this is the purchasers decision. That

decision may be determined by labor contracts because dental benefits are often negotiated benefits. In these cases the union(s) also

has a voice in the benefits design. This is a complex process that is

not simply a coverage choice for the insurance company, the purchaser, or the represented groups.

CLASSIFICATION OF PROGRAMS

Dental payment programs may be classified in several different

ways. Traditionally, they have been classified by who assumes the

risk for loss. As discussed previously, the insurance company may

assume the risk, and this is often referred to as an indemnity plan.

When the dentist assumes the risk, the plan is generally called a

capitation or dental health maintenance organization (DHMO) plan.

Finally, when the employer assumes the risk, the plan is an administrative services or a self-insured plan.

In most of these types of plan designs, there is a system of

checks to ensure that appropriate services are being rendered.

Although no validated data exist to support the figures, some have

estimated that in the US, approximately 7% to 10% of health care

expenses are fraudulently claimed.6 With a $2.4 trillion annual

expenditure on health care, this means that at the high end, $240

billion would be fraudulently expended. With these staggering

numbers, purchasers of health care services want external validation that services have been rendered and that the services rendered were consistent with the benefits they desire to provide.

There is no evidence that the rate of fraud in dentistry is in this

percentage range or that the incentives are equivalent. Most dental

plans have annual maximums and patient co-insurance that do

not permit extensive fraud. However, the dental industry is still

part of the health care industry and is held to the same review

principles.

768.e46

PART 9 Complementary Topics

Indemnity plans allow the patient to seek care from any general

dentist or specialist of his or her choice. There is no contractual

relation between the dentist and the third party. The plan provides

benefits for covered services based on the plans determination of

some maximum plan allowance for a procedure or on a fee schedule

(table of allowances). The patient is responsible for any balance

beyond the benefit provided by the plan. Almost all of these plans

have a yearly or lifetime deductible and maximum payments for

specific procedures and involve payment by the patient of a percentage (co-insurance) of the fee. That percentage varies with the

type of treatment provided. For example, Class I treatment is generally diagnostic and preventive services and often has no required

co-insurance contribution. Class II services (e.g., basic restorative,

endodontics, periodontics, or extractions) usually involve a patient

payment of 20%. Fixed and removable prosthetics and major

restorative procedures such as crowns typically are classified as

Class III, with 50% co-insurance. Periodontal surgery, although

most often considered a Class II expense, is categorized as type III

by some plans.

Other plans offer a contractual relationship between the dentist

and the plan. They may involve a capitation (prepaid) plan, preferred

provider organization (PPO), individual practice association (IPA),

service corporation, or discount plan. These plans may be further

classified by access to dentists. In a point-of-service plan (POS),

patients may see any dentist. The insurance plan may or may not

pay a higher portion of the bill for a patient seeing dentists who

have joined their network. If the plan pays more of the bill (and

the patient less) when a patient sees a network dentist, the plan is

called a PPO. POS plans also include programs in which the

patient has a schedule of allowances. In this case, the plan pays

any dentist the amount listed on the schedule. Members agree by

contract to accept the allowance as their fee subject to the Class

system described above. If the dentist is not a member of the

network (also called a nonparticipating dentist), the patient will

be responsible for any additional fee the dentist requires.

Direct reimbursement (DR) is another type of POS program. In

this strategy, the employer sets aside a sum of money for each

employee and patients see the dentist of their choice, make payments directly to the dentist, and receive a statement demonstrating

those payments. The plan then reimburses patients up to the limits

of the plan. In this particular case, there is no review of treatment

for appropriateness or even whether any particular service was

actually rendered. This plan is attractive to many dentists and some

employers. However, most major purchasers of health services

desire external review.

When payment is restricted to only network dentists, the plan

is termed an exclusive provider organization (EPO). If a patient

chooses to see a dentist outside the network of dentists, the plan

pays nothing and the patient is responsible for all fees. Most

capitation plans fall into this category, with some exceptions for

specialty care.

In a prepaid DHMO or capitation plan, the contracting dentist

is paid a set fee each month for each enrolled patient, regardless of

whether the patient has received any treatment. The dentist agrees

to provide all needed covered services with no patient payment

except for specified co-payments for specified, usually more expensive, treatment such as periodontal surgery and crowns and bridges.

Although the contracting dentist usually is responsible for nonsurgical periodontal care, periodontal surgery typically is referred to a

specialist, who is reimbursed according to a fee schedule. If the

periodontist has contracted with the plan, the patient has no financial responsibility beyond a co-payment. If the specialist has not

contracted with the plan, the patient is responsible for the difference between the plan payment and the dentists fee. Payment for

non-covered services is the patients responsibility. The dentist

assumes the financial risk, so if the capitation fee, co-payments, and

patient payment for services are not sufficient to cover the cost of

treatment, the dentist, not the insurance company or the employer,

is responsible for that difference. Conversely, if the patient uses

fewer resources than the capitated amount, the dentist gains the

difference.

There are different economic incentives and potential deterrents

for dental offices to join panels, groups, or networks. With the PPO

the reimbursement may be discounted from the dentists usual fees.

If there is a discount, the plan is referred to as a fee-discounted

PPO. The advantage of belonging to a PPO is the increased access

to patients for the dental office. The increase in patients is driven

by the listing of the dentist in a directory of dentists available to

patients and by the patients economic incentive to see a network

dentist because the plan pays a greater portion of the bill. If a

dentist needs additional patients in the practice, this may be an

attractive program depending on the reimbursement offered or

allowed by the insurance entity. However, the additional income

generated by an increased patient load must be counterbalanced by

the increased expenses incurred for supplies and materials (see later

discussion on how to make this economic decision).

Participation in any dental program is a personal decision for

each dentist, but before signing any contract, the dentist should

obtain competent legal advice. The dentist also should read the

contract carefully to be aware of the obligations he or she is incurring. It never is sufficient to look only at the fee schedule to determine if participation in a particular plan will be beneficial.

Government-funded programs in the US, such as Medicaid and

Medicare, provide limited coverage for dental care. Medicaid is a

joint federal-state program. Benefits are determined by the states

and vary greatly among them. In some cases, benefits may be

limited to restorations and extractions for children. Medicare is the

federally sponsored program under the Social Security Act and

does not cover most routine dental services. In fact, it specifically

excludes services in conjunction with the care, treatment, filling,

removal of teeth or structures directly supporting teeth. There are

some limited benefits for treatment related to trauma or tumors.

SCIENCE TRANSFER

The reality of treating periodontal problems in the 21st century

is that clinicians need to have expertise in managing a variety of

reimbursement mechanisms that control payments and treatment

options. These mechanisms are constantly changing and are different for each practice locale. Clinicians must make patients

aware of all treatment possibilities and make therapeutic recommendations centered on the patients specific needs and not solely

on the available insurance coverage. This will give each patient a

reliable basis to consent to any given treatment plan and broaden

the availability of high quality periodontal care.

CHAPTER 85 Dental Insurance and Managed Care in Periodontal Practice

BENEFITS DESIGN

Time Limits

768.e47

allowance, the office should calculate the cash flow that will be

generated by the plans subscribers.

It is important to measure these numbers as dollars/ hour of

production and not the total days hours because unutilized chair

time is costly to an office and may warrant participating in a plan

to cover overhead, even with a reduced profit margin.

With the previous information, the following general equation

applies:

Time limits are imposed on various procedures to control costs by

holding the dentist responsible for his or her work for a finite

period of time or in some cases to permit a reevaluation period. An

example is the 2-year limitation on amalgam or resin restorations.

Most plans will not pay for the replacement of a restoration placed

within the preceding 24 months if the plan paid for the original

restoration.

In periodontics, these limitations are imposed on surgical and

nonsurgical services. Often, a plan will not pay for a second surgery

of the same type in the same site for 2 or 3 years. Some carriers

interpret this so that benefits are provided for osseous surgery, but

not for the bone grafts or guided tissue regeneration to repair or

regenerate defects. Benefit frequencies for scaling and root planing

are also limited in most plans. Many of these time limitations have

not been based on scientific evidence or individual patient risk

profiles in the past. Whether they will be based on such evidence

and the emerging personalized health care principles in the future

remains to be seen.

A separate example of time limitations is applicable to sitespecific therapies in treating localized periodontal defects. Some

carriers will not benefit the application of locally applied antibiotics, whereas others cover them with little or no restrictions. Others

will provide a benefit only after a finite healing period has elapsed

following scaling and root planing or periodontal surgery, and then

the plan will only reimburse for application to residual pockets that

show signs of active disease. The rationale is to allow a healing

response to occur, thereby reducing the number of sites that need

to be treated. This limitation is not validated (i.e., neither supported

or refuted) by evidence because most studies for the current, locally

delivered antibiotics have involved placement at the time of scaling

and root planing and not after a healing period.

For the purposes of this chapter, office overhead represents the

fixed costs of running the office, including heat, lights, rent, computers, insurance, and staff salaries. Additional expenses are the

variable costs associated with treating more patients and the mix

of services they receive.

If this equation yields a number greater than 1, the plans payments are at an acceptable level for the dentist.

If the number is less than 1, the dentist must determine whether

to modify the desired profit. If the dentist has unwanted empty

chair time, the calculation should be used to determine if the plans

allowable fees will cover the dentists overhead and additional

expenses.

More complex formulas exist to perform these calculations, but

the underlying principles remain the same.

The dentist should do more than determine if the additional

income is adequate. The contract itself must be analyzed to determine that all obligations imposed are acceptable to the dentist.

Advice should be obtained from advisors who are familiar with

dental benefits contracts.

Balance Billing

Coordination of Benefits

Balance billing is a term used to describe how fee differences

between a plans allowance and a dentists fees are handled. Depending on the dentists relationship with the plan, the dentist may be

unable to bill the patient for the fee difference.

Dentists who join a dental plans group and who have their

name listed in the directory and receive patients from among the

plans subscribers may be limited in their right to bill the patient

for fee differences between their usual fees and those permitted by

the plan. The dentist is trading this fee limitation for the additional

patients received. This may or may not make economic sense.

Determining whether it makes good business sense is quite simple

but does require a careful analysis of treatment provided, the

expenses incurred and the remuneration received. Using the general

equation provided below establishes whether this is an acceptable

dental plan for any specific office.

First, an office needs to examine its mix of services. For a periodontal office, the mix of time spent in providing nonsurgical

therapies, surgical services, and implant services needs to be calculated for a routine three-month period. The results should be

designed to show the percentage of time spent in each of the major

areas of practice, and each area should include the associated caseplanning and presentation times.

Using this percentage mix of services delivered, the dentist

should examine their fee schedule to determine the average hourly

gross income for the office. Using the same percentages and the

dental plans schedule of maximum fees or its preapproved fee

When patients have access to more than one source of dental insurance, the insurance benefits are coordinated (generally by state law)

to determine which plan pays first. Most states follow the lead of

the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) in

setting up the rules for how the benefits are paid. It is important

to know that in most cases, neither the insurance company nor the

purchaser of the health care benefit controls these rules. It is also

important to know what the rules are in your state.

In general, when the patient has dental coverage, his or her

policy is primary (pays first). If the patient is covered as a dependent

under two or more policies, the policyholder whose birthday is

earlier in the year usually is considered primary. In most cases the

secondary carrier will make a supplemental payment only to bring

total benefits up the amount it would have paid had it been primary.

Lack of coordination of benefits information on a claim is the

second most common claim problem encountered by dental insurance companies. If you know that there is only one form of coverage, make a note on the dental claim that there is no other coverage.

Even if the patient is the policyholder, omitting this information

may delay a claim because the insurance plan needs this information to determine the level of payment to make in a given

situation.

There are a number of nuances in how plans will pay, within the

states rules for payment. It is important to know this information

so that it can be discussed with the patient. An easy way to accomplish this with a new plan or when the situation is unclear is to

Fees generated per hour at the plans rates:

Office overhead + Additional expenses + Desired profit/hour

768.e48

PART 9 Complementary Topics

submit an estimate of benefits. This will allow both the dental

office and the patient to review the insurance companys preestimates before financial commitments are made.

A caution regarding pre-estimations in general is that they are

issued based on the claims that have been paid on the date of the

pre-estimation. If other claims are being processed but have not

been paid, or if additional treatment is received before the claim

for actual services is processed, a plans maximum may be exceeded

by the time a claim for the pre-estimated treatment is actually

received. The only rational solution to this dilemma is to work

closely with patients to determine whether they have recently

received or are planning to receive other services and if so, the

amount of those services. Pre-estimations also may not be valid if

the insured individual no longer is covered because of job change

or change in carrier.

As health care costs continue to escalate, an increasing number

of purchasers choose variations on coordination of benefits. For

example, when both members of a spousal pair are employed by

the same employer, the employer may choose to provide coverage

to only the employee and not provide secondary coverage from the

other spouses insurance. This is called nonduplication of benefits.

Alternatively, an employer may choose to provide coverage for only

the individual employee. Any additional coverage for a spouse or

children is elective, and the employee will pay all or a portion of

the additional costs. This listing is not all-inclusive and should be

used only as a cautionary guide.

Alternate Benefits

When several treatments can be used to treat a given situation,

plans may choose to pay for the least expensive, professionally

acceptable treatment. Dentists and their patients are free to choose

the therapy that they want, but the plan will limit payment to the

lower-cost procedure. The dentist and the patient must then determine how to settle the cost difference between the two

procedures.

A straightforward example is a plan paying for an amalgam

restoration in a posterior tooth. If the dentist and patient choose

to restore the tooth with a resin-based restorative material, the plan

will pay for the equivalent amalgam restoration. Because posterior

resin restorations are more labor and procedure intensive, the

dentist will typically charge one-third to half more for an equivalent resin restoration. The payment of the additional fee is the

patients responsibility. Coverage for implants also may be affected

by this contract provision. Although the dentist and patient may

agree that replacement of a missing tooth with an implant is appropriate, the plan may determine that it could be replaced by a removable partial denture. In these cases the plan may provide a benefit

to the restorative dentist equal to that for a removable partial

denture but no benefit for placement of the implant. In some cases,

however, benefits will be provided only for the treatment provided

so the patient would not receive any reimbursement.

Exclusions

Purchasers of dental benefits may exclude certain procedures or

classes of procedures as a mechanism for containing costs. For

example, a purchaser may choose to exclude orthodontic treatment

from its coverage or limit it to children under age 19 years. This

represents a whole service category that is not covered by the plan.

Purchasers could also choose to limit how they will pay for the

restoration of a bounded edentulous space. They may cover a threeunit bridge or a removable partial denture and not an implant.

Alternatively, they may cover either the bridge or the implant but

exclude preprosthetic procedures (e.g., sinus lift surgery).

Exclusions are generally considered totally outside the insurance

plan and not limited by the plan. However, this statement requires

a word of caution, particularly as it relates to implants. A number

of plans will not pay for the placement of an implant (it is clearly

excluded in the contract language), whereas the restoration of the

implant may receive coverage at the standard rate for a crown.

Although in this case the clinician placing the implant must be

remunerated for those services outside the insurance plan, the

patient should be advised to check with the plan to see if the

prosthesis that will be placed on the implant is a covered benefit.

Some contracts specify that payment for noncovered services (as

distinct from excluded benefits) is determined by the carrier. This

may occur even though that amount may not have been negotiated

and, in some cases, is not made known to the patient or dentist

before submission of a claim. In these cases, pre-estimation of

benefits is in everyones best interest.

Adjudication

Adjudication means acting as a judge or referee. This is a function

performed by a dental benefits carrier for the purchaser of health

care services. The purchaser wants to ensure that needed and appropriate services for their employees are benefited and that the thirdparty payer has the expertise to provide this service. This can be an

area of conflict between the periodontal office and the carrier in

that differences of opinion can exist regarding whether a specific

case meets the contract requirement for specific services. Most

dental benefit plans provide coverage for services and supplies that

are determined [by the carrier] to be necessary for the diagnosis,

care, or treatment of the condition involved. Because few, if any,

dentists provide services they do not believe are necessary for the

diagnosis, care, or treatment of the condition involved, there can

be a difference of opinion between the dentist and the payers dental

consultant.

Differences of opinion occur for a number of reasons, but the

most common reason is a lack of salient information being transferred between the dental office and the insuring entity. The key to

obtaining coverage, within the scope of the purchased benefits, is

providing the claims reviewer with enough information so that the

person can make an informed decision. When information is

lacking, the person adjudicating the claim is compelled to deny the

service because the contract with the purchaser defines the reviewers duties and responsibilities in this area. It would be a violation

of the contract between the insurance entity and the purchaser to

pay for services that do not meet the conditions of the contract.

Carriers are audited regularly by plan purchasers and must refund

moneys paid inappropriately.

To overcome this problem, the submitting dental office should

provide enough information so that a person with similar training

would be able to make the same treatment decision as the dental

office. This can be in the form of a narrative or attachments. The

narrative should be clinically descriptive rather than the expression

of an opinion. The submitter should briefly describe the clinical

condition in sufficient detail to allow a person who is not seeing

the patient to make an informed decision about the service the

clinician is performing or wants to perform. In most cases it is not

necessary to describe the procedure in detail; dental consultants

know what is done.

Attachments

Attachments such as periodontal charts, radiographs, and narratives

are a useful way to augment the information on a claim. They can

be submitted along with a paper claim or electronically. Electronic

claims have limitations on the length of a narrative, so attachments

CHAPTER 85 Dental Insurance and Managed Care in Periodontal Practice

can be provided either by mailing them to the insurance company

or by providing them by electronic means. Some insurance companies are set up to receive electronic attachments directly; however,

many do not have this capability.

To fill this electronic business need, a number of companies

have entered the business of receiving electronic dental attachments

and storing them for use by any insurance company or other professional. In general with these services, the dental office uses its direct

digital images (e.g., digital radiographs, electronic periodontal

charts) or converts existing documents (e.g., periodontal charts,

radiographs) into a digital format. This format can usually be any

of the standard formats that scanners or digital devices output. That

digital information is transmitted via the Internet to the electronic

attachment company using its software. In some cases these images

have been integrated into electronic dental records so that only one

data entry is required. When the electronic attachment company

receives the image, it immediately transmits a randomized unique

identification code for that image(s) back to the dental office. The

dental office then puts that unique code into the Comments box

on the claim form and transmits it to the dental benefits company.

Because the code is randomized and unique to the specific digital

information transmitted from the dental office to the online storage

facility, the carrier uses that code to view only that attachment. The

images are available for a preset amount of time, often up to 3 years,

so appeals and submissions for subsequent treatment or decision

appeals do not require added transmissions.

The cost of these services varies slightly, but for periodontal

offices, they may represent a significant cost reduction mechanism.

These stored images are available to the insurance company and

can be used to share patient information with a referring dentist,

thereby saving time, handling, and other costs associated with

moving information back and forth. It also eliminates the potential

for lost records.

Health Insurance Portability and

Accountability Act

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

(HIPAA) required the US Department of Health and Human

Services to adopt national standards for electronic submission of

all electronic administrative and financial health care transactions.

Dentists and all other health care providers who submit claims

electronically either directly or through a billing service (clearinghouse) are considered covered entities and must comply with all

HIPAA provisions. The law requires payers to accept and health

care providers to submit all electronic claims in the standard format,

but it does not require dentists to submit all (or any) claims electronically. Third parties still must accept paper claims. Because

paper claims are substantially more expensive to manage for the

benefits companies (as well as for dental offices), it is likely that

they will charge a premium for them in the future. In other words,

if the dental office chooses to submit paper claims, it will be

charged for the increased transaction costs. It is unclear when this

will occur, but it is being considered.

768.e49

MOST COMMON ERRORS

The three most common submission errors that dental offices make

when submitting claims to third-party payment systems are as

follows:

1. Incorrect recording of the patients birth date.

2. Providing no information about other potential insurance

coverage.

3. Incorrect entering of social security numbers.

If these elements are double-checked by the office staff before

submission, approximately 50% of all errors will be eliminated.

Third-party carriers also make errors, although electronic submission of claims lowers third-party error rates because the data

entry function occurs in the dental office. The most common thirdparty errors are as follows:

1. Loss of submitted documentation, leading to repeated

requests for the documentation and delay in adjudication of

claims. This can be mitigated, as noted earlier, by electronically filing documentation.

2. Requests for unnecessary documentation such as requesting

radiographs for soft tissue grafts.

3. Failure to check patients histories that document prior

treatment.

CONCLUSION

Dental benefits are part of many patients payment strategies for

dental services. Therefore it is useful to understand the nature of

dental insurance, why purchasers of benefits provide insurance for

their employees, and how insurance is changing as the incidence,

prevalence, and penetration of diseases change. These areas will

continue to change as we learn more about treating the primary

diseases of dentistry.

As in medicine, more individualized health plans, based on a

patients risk profile and the best currently available evidence will

begin to emerge in dental plans. These risk calculations will take a

number of forms and will evolve over time so that in the future,

patients at higher risk for either caries or periodontal diseases

will have increased access to proven preventive or interceptive

techniques.

It is the responsibility of the treating dentist to provide the

information on the best available therapies for patients regardless

of the limitations of the patients insurance. It is important always

to remember that the dentist is treating the patient, not the insurance

policy. Armed with this information, the patient and the dentist can

reach an individual decision about treatment. It is also in the

patients best interest for a dental office to submit a pre-estimation

of benefits for more expensive and nonroutine treatments. In this

way, the office is helping the patient maximize the use of available

benefits and is not making assumptions that may limit this

opportunity.

768.e50

PART 9 Complementary Topics

REFERENCES

1. Anderson MH, del Augila M: Treatment distribution in an

insured population, 1998 (Unpublished study of insurance data).

2. Goodman BF: Personal communication, 2000.

3. Marshall-Day CD: The epidemiology of periodontal disease,

J Periodontal Res 22:13, 1951.

4. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS): Second National

Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (Nhanes II), Hyattsville, MD, 1996, NCHS.

5. National Center for Health Statistics: Life expectancy at birth

and at 65 years of age by sex and race, 1900-2000, http://

www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/lifexpec.htm, 2005.

6. National Health Care Fraud Association: Health care fraud: a

serious and costly reality for all Americans, http://www.nhcaa.org/

pdf/all_about_hcf.pdf, 2005.

You might also like

- Smile Again CaseDocument28 pagesSmile Again CaseKeshav NautiyalNo ratings yet

- MCQs in DentistryDocument135 pagesMCQs in Dentistrysam4sl98% (85)

- Justice in Oral Health CareDocument371 pagesJustice in Oral Health CareSara Maria Menck SangiorgioNo ratings yet

- What Doctors Dont Tell You - The Dental HandbookDocument124 pagesWhat Doctors Dont Tell You - The Dental HandbookSeeTohKevin100% (1)

- Brushing and Flossing The Teeth of Conscious and Unconscious Client Procedure ChecklistDocument3 pagesBrushing and Flossing The Teeth of Conscious and Unconscious Client Procedure ChecklistMONIQUE GONZALESNo ratings yet

- Ubc ApplicationDocument3 pagesUbc Applicationapi-508959687No ratings yet

- Surgeon General'S Perspectives: Oral Health: The Silent EpidemicDocument2 pagesSurgeon General'S Perspectives: Oral Health: The Silent EpidemicArida BitanajshaNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument3 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Oral Health in AmericaDocument332 pagesOral Health in AmericaAdrian GheorgheNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument3 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Policy Healthcare ReformDocument3 pagesPolicy Healthcare Reformsonia_groff6256No ratings yet

- The Oral Health Information Suite (OHIS) : Its Use in The Management of Periodontal DiseaseDocument12 pagesThe Oral Health Information Suite (OHIS) : Its Use in The Management of Periodontal DiseasejemmysenseiNo ratings yet

- Women'S: A Literature Review OnDocument14 pagesWomen'S: A Literature Review OnAudrey Kristina MaypaNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Nixon-Health Policy PaperDocument5 pagesNixon-Health Policy Paperapi-291204444No ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Should NHS Dentistry Be FreeDocument4 pagesShould NHS Dentistry Be FreePranav SivakumarNo ratings yet

- Leake2008 PDFDocument9 pagesLeake2008 PDFjhon killNo ratings yet

- Klein1938 CPODDocument16 pagesKlein1938 CPODAlejandro RuizNo ratings yet

- Viewpoint Synthesis Final DraftDocument5 pagesViewpoint Synthesis Final Draftapi-589364430No ratings yet

- Boyce, 2021Document32 pagesBoyce, 2021Matheus Souza Campos CostaNo ratings yet

- Professional: Why Do We Need An Oral Health Care Policy in Canada?Document11 pagesProfessional: Why Do We Need An Oral Health Care Policy in Canada?petewin0123No ratings yet

- Senate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Dental Crisis in America: The Need To Address CostsDocument52 pagesSenate Hearing, 113TH Congress - Dental Crisis in America: The Need To Address CostsScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The CareDocument5 pagesDental Evolving Medical Scene: Care in The Carecarlina_the_bestNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Universal Health CareDocument8 pagesThesis Statement On Universal Health Caretammylacyarlington100% (2)

- Intro To Biological DentistryDocument7 pagesIntro To Biological DentistryFelipe LazzarottoNo ratings yet

- Economics Health CareDocument79 pagesEconomics Health CareLuiz CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Wahl 2006Document5 pagesWahl 2006anas dkaliNo ratings yet

- Dental Caries PandemicDocument5 pagesDental Caries PandemicKarla González GNo ratings yet

- Essay BlogDocument7 pagesEssay BlogWilliam W. LeeNo ratings yet

- Dental Implant Failure: A Clinical Guide to Prevention, Treatment, and Maintenance TherapyFrom EverandDental Implant Failure: A Clinical Guide to Prevention, Treatment, and Maintenance TherapyThomas G. Wilson Jr.No ratings yet

- Aids DissertationDocument5 pagesAids DissertationCustomPaperWritersUK100% (1)

- Alginate ImpressionDocument60 pagesAlginate ImpressionNugraha AnggaNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Oral Health Conditions in Older People: OriginalarticleDocument8 pagesEpidemiology of Oral Health Conditions in Older People: OriginalarticleWJNo ratings yet

- BMC Oral Health: Biotech and Biomaterials Research To Reduce The Caries EpidemicDocument7 pagesBMC Oral Health: Biotech and Biomaterials Research To Reduce The Caries EpidemicKranti PrajapatiNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureDocument10 pagesOral Health Disparities Among The Elderly: Interdisciplinary Challenges For The FutureJASPREETKAUR0410No ratings yet

- Periodicity DentalGuideDocument52 pagesPeriodicity DentalGuideSalam BataienehNo ratings yet

- State of DecayDocument8 pagesState of DecayWisdomToothOHANo ratings yet

- History of US Health Care System-Final ProjectDocument12 pagesHistory of US Health Care System-Final ProjectAntonio Abreu Jr.100% (1)

- Geriatric Oral Health Concerns A Dental Public Hea PDFDocument6 pagesGeriatric Oral Health Concerns A Dental Public Hea PDFفواز نميرNo ratings yet

- Akikut - Pride PaperDocument15 pagesAkikut - Pride Paperapi-486142180No ratings yet

- Planificacion en VIDocument16 pagesPlanificacion en VIGaby Tipan JNo ratings yet

- Health Care Crisis Thesis StatementDocument4 pagesHealth Care Crisis Thesis Statementsdeaqoikd100% (1)

- Dentistry in Post COVIDDocument3 pagesDentistry in Post COVIDsagrika groverNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Kindness: Reforming The Culture of HealthcareDocument7 pagesIntelligent Kindness: Reforming The Culture of Healthcarefarnaz_2647334No ratings yet

- Covid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint DisordersDocument5 pagesCovid-19 Impact An Oral Health With A Focus On Temporomandibular Joint Disordersbotak berjamaahNo ratings yet

- Final TintinDocument5 pagesFinal TintinRenier FloresNo ratings yet

- Universal Health Care Research PaperDocument5 pagesUniversal Health Care Research Paperwftvsutlg100% (1)

- Dental Amalgam and Mercury in Dentistry: Invited ReviewDocument11 pagesDental Amalgam and Mercury in Dentistry: Invited ReviewRichard Serrano Garcia OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Sage Publications, Inc., American Academy of Political and Social Science The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social ScienceDocument9 pagesSage Publications, Inc., American Academy of Political and Social Science The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Scienceassaini carinta padangNo ratings yet

- Rough Draft Health Care 4Document10 pagesRough Draft Health Care 4long_paula1No ratings yet

- SJ BDJ 2008Document1 pageSJ BDJ 2008idurdNo ratings yet

- Letter To Mrs. Clinton-May 1993-By Trudy Attenberg-Face ForwardDocument2 pagesLetter To Mrs. Clinton-May 1993-By Trudy Attenberg-Face ForwardNeil GillespieNo ratings yet

- Managementofedentulous Patients: Damian J. Lee,, Paola C. SaponaroDocument13 pagesManagementofedentulous Patients: Damian J. Lee,, Paola C. Saponarosnehal jaiswalNo ratings yet

- The Young Professions Australia Roundtable 2003 Achieving A Sustainable Future A Dental PerspectiveDocument7 pagesThe Young Professions Australia Roundtable 2003 Achieving A Sustainable Future A Dental PerspectiveAhmed GendiaNo ratings yet

- ND Annual: Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology ReviewDocument12 pagesND Annual: Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology Reviewsulai701280No ratings yet

- Oral Diseases - 2023 - JainDocument7 pagesOral Diseases - 2023 - JainGita PratamaNo ratings yet

- IMPORTANTE Promoc Educac Salud Adult MayorDocument4 pagesIMPORTANTE Promoc Educac Salud Adult MayorJorge BalzanNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics Public Health DentistryDocument5 pagesThesis Topics Public Health DentistryKristen Flores100% (2)

- Dental EducationDocument14 pagesDental EducationiwanntataNo ratings yet

- U O H S P 2016-2020: Topia RAL Ealth Urveillance LANDocument15 pagesU O H S P 2016-2020: Topia RAL Ealth Urveillance LANNoor Muddassir KhanNo ratings yet

- Gallium and Indium ScanDocument1 pageGallium and Indium ScanSri HariNo ratings yet

- 30 37Document8 pages30 37Sri HariNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document6 pagesLesson 1Sri HariNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Radionuclide ImagingDocument5 pagesChapter 2 Radionuclide ImagingSri HariNo ratings yet

- Management of Acute and Chronic Retention in MenDocument52 pagesManagement of Acute and Chronic Retention in MenSri HariNo ratings yet

- Usg in UrologyDocument25 pagesUsg in UrologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Renogram GuidelineDocument14 pagesRenogram GuidelineSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghDocument9 pagesContrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghSri HariNo ratings yet

- Uro DynamicsDocument64 pagesUro DynamicsSri HariNo ratings yet

- Intraluminal Navigation Through Any Hollow Viscus Is PossibleDocument3 pagesIntraluminal Navigation Through Any Hollow Viscus Is PossibleSri HariNo ratings yet

- Uro Dynamics 1Document22 pagesUro Dynamics 1Sri HariNo ratings yet

- UroflowDocument41 pagesUroflowSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Media: Dr.R.Abhiman Gautam, MCH Urology Prof - DR.RK Unit Stanley Medical CollegeDocument18 pagesContrast Media: Dr.R.Abhiman Gautam, MCH Urology Prof - DR.RK Unit Stanley Medical CollegeSri HariNo ratings yet

- Xray AbdomenDocument22 pagesXray AbdomenSri HariNo ratings yet

- Intravenous Radiographic Contrast Induced Adverse Reactions - Their Causes, Prevention and Relief MeasuresDocument7 pagesIntravenous Radiographic Contrast Induced Adverse Reactions - Their Causes, Prevention and Relief MeasuresSri HariNo ratings yet

- CT Angiography in UrologyDocument2 pagesCT Angiography in UrologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced NephropathyDocument2 pagesContrast Induced NephropathySri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Arteriography: Reasons Not As A Preliminary Screening ToolDocument3 pagesContrast Arteriography: Reasons Not As A Preliminary Screening ToolSri HariNo ratings yet

- Contrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghDocument9 pagesContrast Induced Nephropathy in Urology: Viji Samuel Thomson, Kumar Narayanan, J. Chandra SinghSri HariNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Performa For Registration of Subject For DissertationDocument21 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka. Performa For Registration of Subject For DissertationSri HariNo ratings yet

- Clean Intermittent Catheterization (CIC) : IndicationsDocument2 pagesClean Intermittent Catheterization (CIC) : IndicationsSri HariNo ratings yet

- Impact of Endometrial Preparation Protocols For Frozen Embryo Transfer On Live Birth RatesDocument8 pagesImpact of Endometrial Preparation Protocols For Frozen Embryo Transfer On Live Birth RatesSri HariNo ratings yet

- Captopril Renography: Physiologic Principle - Loss of Preferential Vasoconstriction of The EfferentDocument3 pagesCaptopril Renography: Physiologic Principle - Loss of Preferential Vasoconstriction of The EfferentSri HariNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologyDocument5 pagesEuropean Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive BiologySri HariNo ratings yet

- Mccormick: Michael J. CoughlinDocument1 pageMccormick: Michael J. CoughlinSri HariNo ratings yet

- Access SheathDocument22 pagesAccess SheathSri HariNo ratings yet

- Maternal Mortality: Liliana Carvajal Vibeke Oestreich Nielsen Armando H. SeucDocument38 pagesMaternal Mortality: Liliana Carvajal Vibeke Oestreich Nielsen Armando H. SeucSri HariNo ratings yet

- 03 A025 5123Document13 pages03 A025 5123Sri HariNo ratings yet

- History of Articulators Part 1 2004Document13 pagesHistory of Articulators Part 1 2004ayduggal100% (4)

- Biomimetic AllemanDocument6 pagesBiomimetic AllemanAlireza RaieNo ratings yet

- Tooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaDocument19 pagesTooth Positioning: The Basic Positions of Artificial Teeth May Be Described in Relation To Three CriteriaCherine SnookNo ratings yet

- Ahead FPD QuesDocument11 pagesAhead FPD QuesMostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- Cephalometric Distintion of Class II Division 2Document8 pagesCephalometric Distintion of Class II Division 2Diego SolaqueNo ratings yet

- KariesDocument4 pagesKariesSherlocknovNo ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene InstructionsDocument2 pagesOral Hygiene Instructionstepokpantat100% (1)

- Malkinson Et Al. 2012Document15 pagesMalkinson Et Al. 2012Nawaf RuwailiNo ratings yet

- Kep NursewndDocument18 pagesKep NursewndUntung Edi SaputraNo ratings yet

- SPSC 2018 Paper Type ADocument8 pagesSPSC 2018 Paper Type AMeenaNo ratings yet

- BIO C Repair With For Horizontal Root Fracture PDFDocument5 pagesBIO C Repair With For Horizontal Root Fracture PDFDaniel Vivas0% (1)

- Cementoblastoma and Periapical Cemento-Osseous DysplasiaDocument15 pagesCementoblastoma and Periapical Cemento-Osseous DysplasiaHessa AloliwiNo ratings yet

- Prost Ho Don TicsDocument172 pagesProst Ho Don Ticsسماح صلاحNo ratings yet

- Smile Arc Protection Part 2Document4 pagesSmile Arc Protection Part 2M.Laura100% (1)

- Annual Review of Selected ScientificDocument50 pagesAnnual Review of Selected Scientificpasber26No ratings yet

- Stability and RetentionDocument8 pagesStability and RetentionlizetNo ratings yet

- CHN Compre Exm 1Document8 pagesCHN Compre Exm 1Roy Salvador100% (1)

- Gingival Biotype Classification, Assessment, and Clinical Importance: A ReviewDocument7 pagesGingival Biotype Classification, Assessment, and Clinical Importance: A ReviewKetherin LeeNo ratings yet

- Davidovitch1995 PDFDocument6 pagesDavidovitch1995 PDFRahulLife'sNo ratings yet

- Dental Clinic (Job Description)Document10 pagesDental Clinic (Job Description)A'ihNo ratings yet

- Friday June 18, 2010 LeaderDocument47 pagesFriday June 18, 2010 LeaderSurrey/North Delta LeaderNo ratings yet

- Test - 10 Root (Radicular) CystsDocument5 pagesTest - 10 Root (Radicular) CystsIsak ShatikaNo ratings yet

- Project Practicum PresentationDocument37 pagesProject Practicum Presentationapi-652480224No ratings yet

- Oral Hygiene Instruction Presentation Danielle WilsonDocument15 pagesOral Hygiene Instruction Presentation Danielle Wilsonapi-348271404No ratings yet

- Texas Medicaid and CHIP Provider FAQsDocument4 pagesTexas Medicaid and CHIP Provider FAQsangelina smithNo ratings yet

- Guide To BolognaDocument48 pagesGuide To Bolognamiry89No ratings yet