Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ophelia De'Lonta v. Gene Johnson, 4th Cir. (2013)

Ophelia De'Lonta v. Gene Johnson, 4th Cir. (2013)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ophelia De'Lonta v. Gene Johnson, 4th Cir. (2013)

Ophelia De'Lonta v. Gene Johnson, 4th Cir. (2013)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

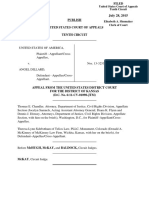

PUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

OPHELIA AZRIEL DELONTA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

GENE JOHNSON, Director of VDOC;

FRED SCHILLING, Director of Health

Services for VDOC; MEREDITH R.

CAREY, Chief Psychiatrist for

VDOC; GARY L. BASS, Chief of

Operations, VDOC; W. P. ROGERS,

Assistant Deputy Director of

Operations, VDOC; GERALD K.

WASHINGTON, Regional Director,

Central Regional Office for the

VDOC; EDDIE PEARSON, Warden of

Powhatan Correctional Center,

VDOC; ANTHONY SCOTT, Chief of

Security at Powhatan Correctional

Center; ROBERT L. HULBERT, PhD.,

Mental Health Director for the

VDOC; LARRY EDMONDS, Warden,

Buckingham Correctional Center,

VDOC; MAJOR C. DAVIS, Chief of

Security of Buckingham

Correctional Center;

No. 11-7482

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

LISA LANG, Staff Psychologist;

TONEY, Counselor at Buckingham

Correctional Center; LOU DIXON,

Registered Nurse Manager,

Buckingham Correctional Center,

Defendants-Appellees.

DC TRANS COALITION; AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF VIRGINIA,

INCORPORATED,

Amici Supporting Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Virginia, at Roanoke.

James C. Turk, Senior District Judge.

(7:11-cv-00257-JCT-RSB)

Argued: October 24, 2012

Decided: January 28, 2013

Before MOTZ, KING, and DIAZ, Circuit Judges.

Reversed and remanded by published opinion. Judge Diaz

wrote the opinion, in which Judge Motz and Judge King

joined.

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Bernadette Francoise Armand, VICTOR M.

GLASBERG & ASSOCIATES, Alexandria, Virginia, for

Appellant. Earle Duncan Getchell, Jr., OFFICE OF THE

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIRGINIA, Richmond, Virginia, for Appellees. ON BRIEF: Victor M. Glasberg, VICTOR M. GLASBERG & ASSOCIATES, Alexandria,

Virginia, for Appellant. Kenneth T. Cuccinelli, II, Attorney

General of Virginia, Michael H. Brady, Assistant Attorney

General, Charles E. James, Jr., Chief Deputy Attorney General, Wesley G. Russell, Jr., Deputy Attorney General,

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL OF VIRGINIA,

Richmond, Virginia, for Appellees. Jeffrey Light, LAW

OFFICE OF JEFFREY LIGHT, Washington, D.C., for DC

Trans Coalition, Amicus Supporting Appellant. Joshua Block,

AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION,

New York, New York; Rebecca K. Glenberg, AMERICAN

CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION OF VIRGINIA FOUNDATION,

INC., Richmond, Virginia, for American Civil Liberties

Union Inc., and American Civil Liberties Union of Virginia,

Inc., Amici Supporting Appellant.

OPINION

DIAZ, Circuit Judge:

Virginia inmate Ophelia Azriel Delonta (born Michael A.

Stokes) filed suit under 42 U.S.C. 1983 claiming that prison

officials denied her adequate medical treatment in violation of

the Eighth Amendment. The district court dismissed the complaint for failure to state a claim. Because we conclude that

Delontas complaint states a claim for relief that is plausible

on its face, we reverse and remand for further proceedings.

I.

On appeal from a dismissal for failure to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted, we accept as true all the factual

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

allegations contained in the complaint and construe them in

the light most favorable to the plaintiff. Flood v. New Hanover County, 125 F.3d 249, 251 (4th Cir. 1997).

A.

Delonta has been in the custody of the Virginia Department of Corrections ("VDOC") since 1983, serving a 73-year

sentence for bank robbery. She is a pre-operative transsexual

suffering from a diagnosed and severe form of a rare, medically recognized illness known as gender identity disorder

("GID"). GID is characterized by a feeling of being trapped

in a body of the wrong gender. This belief has caused

Delonta to suffer "constant mental anguish" and, on several

occasions, has caused her to attempt to castrate herself in

efforts to "perform[ ] [her] own makeshift sex reassignment

surgery." App. 14, 46, 48. Delonta has described these ongoing urges to perform self-surgery as "overwhelming." App.

31.

In 1999, Delonta filed a 1983 lawsuit alleging that

VDOC had instituted a policy that wrongfully prevented her

from receiving GID treatment in violation of the Eighth

Amendment. As in the instant case, the district court dismissed Delontas 1999 complaint for failure to state a claim.

We reversed and remanded, holding that Delontas need for

protection against continued self-mutilation constituted an

objectively serious medical need under the Eighth Amendment and that Delonta had sufficiently alleged VDOCs

deliberate indifference to that need. Delonta v. Angelone

("Delonta I"), 330 F.3d 630, 634 (4th Cir. 2003). The parties

subsequently reached a settlement in which VDOC acknowledged Delontas serious medical need and agreed to provide

continuing treatment.

Since that settlement, VDOC, in consultation with an outside Gender Identity Specialist, has provided Delonta with

GID treatment consisting of regular psychological counseling

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

and hormone therapy. Delonta has also been allowed to dress

and live as a woman to the full extent permitted by VDOC.

Despite these treatments, which have continued since 2004,

Delontas symptoms have persisted. In a series of formal

grievances and letters, Delonta notified prison officials of her

"extreme distress" with her treatment team. She complained

that although her treatment program had produced "growth

and stability[,]" she was still feeling strong, "imminent" urges

to self-castrate. In July 2010, Delonta was hospitalized following a self-castration attempt.

In a September 2010 letter, Delonta asserted that her urges

to self-castrate are particularly overwhelming immediately

following her therapy sessions with VDOC Psychologist Lisa

Lang. J.A. 31. Delonta asked to stop seeing Lang, and repeatedly requested sex reassignment surgery pursuant to the GID

treatment guidelines established by the "Benjamin Standards

of Care" ("Standards of Care").

The Standards of Care, published by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,1 are the generally

accepted protocols for the treatment of GID. They establish a

"triadic treatment sequence" comprised of (1) hormone therapy; (2) a real-life experience of living as a member of the

opposite sex; and (3) sex reassignment surgery. App. 15. The

Standards of Care explain that although the first two treatment

options provide sufficient relief for some patients, others with

more severe GID may require sex reassignment surgery. Pursuant to the Standards of Care, after at least one year of hormone therapy and living in the patients identified gender

role, sex reassignment surgery may be necessary for some

individuals for whom serious symptoms persist. App. 16. In

these cases, the surgery is not considered experimental or cos1

Formerly known as the Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, which is the name to which Delonta referred in her complaint.

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

metic; it is an accepted, effective, medically indicated treatment for GID.

Responding to Delontas letters and grievances, VDOCs

Chief Psychiatrist, Dr. Meredith Cary, replied that "in regards

to gender reassignment surgery, I would request that you continue to work with Ms. Lang in individual therapy at this

time." App. 37. Although VDOC consults with an outside

Gender Identity Specialist regarding Delontas care, she has

never been evaluated by a GID specialist concerning her need

for sex reassignment surgery.

B.

In 2011, Delonta filed suit against Gene Johnson, the former director of VDOC, as well as numerous VDOC administrators and members of her care team (collectively,

"Appellees"). Delontas complaint alleges that, in light of

their knowledge of her ongoing risk of self-mutilation, Appellees continued denial of consideration for sex reassignment

surgery constitutes deliberate indifference to her serious medical need in violation of the Eighth Amendment. On screening

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1915A(b)(1), the district court dismissed the complaint without prejudice for failure to state a

claim upon which relief could be granted.2 Delonta v. Johnson ("Delonta II"), No. 7:11-CV-00257, 2011 WL 5157262

(W.D. Va. Oct. 28, 2011).

The district court held that Delonta failed to allege deliberate indifference on the part of Appellees sufficient to state an

Eighth Amendment claim. The court explained that

2

Although a dismissal without prejudice is not normally appealable,

because the grounds provided by the district court for dismissal "clearly

indicate that no amendment in the complaint could cure the defects in the

plaintiffs case," we conclude that the order dismissing Delontas complaint is an appealable final order. Domino Sugar Corp. v. Sugar Workers

Local Union 392, 10 F.3d 1064, 1066-67 (4th Cir. 1993) (alteration &

internal quotation omitted).

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

Delontas own allegations contradict the conclusion that

Appellees are "persistently denying her treatment," since

Delonta acknowledges that VDOC has provided mental

health consultations, hormone therapy, and cross-dressing

allowances in accordance with the Standards of Care.

Delonta II, 2011 WL 5157262, at *5. "The only treatment

described by the Standards of Care that she has not yet

received," the court observed, "is the sex reassignment surgery." Id. But because Delonta has not been approved for

that surgery, the district court determined that she is "not entitled to" it. Id. In the view of the district court, Appellees are

permissibly denying Delonta "only her preferred therapy of

surgery." Id. at *5-6. Since Delonta has not presented "a situation where there is a total failure to give medical attention or

a policy prohibiting her treatment for GID," the court held

that "her current dissatisfaction with the progress or choice of

treatment" is insufficient to support an Eighth Amendment

claim. Id. at *6.

Delonta appeals, arguing that the district court erred in dismissing her Eighth Amendment claim.3

II.

The sole issue before us is whether Delontas complaint

states a plausible Eighth Amendment claim. We review de

novo a district courts dismissal under 28 U.S.C. 1915A for

failure to state a claim, applying the same standards as those

for reviewing a dismissal under Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6).

Slade v. Hampton Rds. Regl Jail, 407 F.3d 243, 248 (4th Cir.

2005); cf. Delonta I, 330 F.3d at 633. To survive a motion

to dismiss under that rule, a complaint must contain "suffi3

The district court also dismissed without prejudice an Equal Protection

claim and a separate Eighth Amendment claim asserting that Nurse Lou

Dixon improperly denied Delontas hormone treatment on one occasion.

Because Delonta does not press these claims on appeal, we do not address

them here.

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

cient factual matter, accepted as true, to state a claim to relief

that is plausible on its face." Ashcroft v. Iqbal, 556 U.S. 662,

678 (2009) (quoting Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly, 550 U.S.

544, 570 (2007)). In assessing the complaints plausibility, we

accept as true all the factual allegations contained therein.

Coleman v. Md. Court of Appeals, 626 F.3d 187, 190 (4th Cir.

2010), affd sub nom. Coleman v. Court of Appeals of Md.,

132 S. Ct. 1327 (2012). Additionally, we afford liberal construction to the allegations in pro se complaints raising civil

rights issues. Brown v. N.C. Dept of Corr., 612 F.3d 720, 722

(4th Cir. 2010).

A.

Delonta contends she has stated a valid constitutional

claim because the Appellees "denial of consideration for sex

reassignment surgery, when viewed against the backdrop of

her medical history and circumstances, constitutes a deliberate

indifference to her serious medical needs in violation of the

Eighth Amendment." Appellants Br. at 13.

Appellees counter that Delontas complaint fails to satisfy

Twomblys plausibility requirement. While conceding that

Delontas need for protection from self-mutilation is a serious medical need, Appellees assert that because Delonta has

never been prescribed sex reassignment surgery, she cannot

allege that sex reassignment surgery is a serious medical need

for the purposes of the Eighth Amendment. Because Delonta

has no constitutional right to her preferred form of treatment,

Appellees suggest that their refusal to provide her sex reassignment surgery is a matter of discretion that carries no constitutional implications.

Next, Appellees charge that "[b]y alleging that defendants

have actively participated in providing treatment directed to

[Delontas] urges to self-mutilate, [Delonta] has necessarily

failed to state a plausible claim that defendants were deliberately indifferent to that risk." Appellees Br. at 18. In other

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

words, Appellees contend that because they have provided

some treatment recognized as effective under the Standards of

Care, their conduct cannot be said to rise to the level of deliberate indifference.

Finally, Appellees argue that since Delontas GID treatment is governed by the settlement agreement that arose from

her 1999 lawsuit, she "cannot establish that [Appellees] acts

or omissions with regard to that treatment rise to the level of

a constitutional violation." Id. at 21.

B.

As we explained in Delonta I, "[i]n order to establish that

she has been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment, a

prisoner must prove (1) that the deprivation of [a] basic

human need was objectively sufficiently serious, and (2) that

subjectively the officials act[ed] with a sufficiently culpable

state of mind." 330 F.3d at 634 (internal quotations omitted)

(alterations in original). Only an extreme deprivation, that is,

a "serious or significant physical or emotional injury resulting

from the challenged conditions," or substantial risk thereof,

will satisfy the objective component of an Eighth Amendment

claim challenging the conditions of confinement. Id. The subjective component of such a claim is satisfied by a showing

of deliberate indifference by prison officials. This "entails

something more than mere negligence" but does not require

actual purposive intent. Id. "It requires that a prison official

actually know of and disregard an objectively serious condition, medical need, or risk of harm." Id. (quoting Farmer v.

Brennan, 511 U.S. 825, 837 (1994)).

C.

Applying this two-prong Eighth Amendment standard, we

first resolve that Delonta has alleged an objectively serious

medical need for protection against continued self-mutilation.

Indeed, we previously held as much in Delonta I. Id. at 634

10

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

("[P]rison officials have a duty to protect prisoners from selfdestruction or self-injury." (quoting Lee v. Downs, 641 F.2d

1117, 1121 (4th Cir. 1981)). In any case, Appellees concede

this point. Appellees Br. at 15.

Next, we conclude that Delontas complaint sufficiently

alleges Appellees deliberate indifference to her serious medical need, and consequently, that the district courts dismissal

was in error.

There is no dispute that Appellees have, at all relevant

times, been aware of Delontas GID and its debilitating

effects on her. Indeed, since the settlement of Delontas earlier lawsuit, Appellees have provided Delonta with hormone

treatment, mental health consultations, and have allowed her

to live and dress as a woman. It is also true, as Appellees and

the district court note, that these treatment options do accord

with the first two stages of the triadic protocol established by

the Standards of Care. However, the Standards of Care also

indicate that sex reassignment surgery may be necessary for

individuals who continue to present with severe GID after one

year of hormone therapy and dressing as a woman. App. 1617.

Delonta alleges that, despite her repeated complaints to

Appellees alerting them to the persistence of her symptoms

and the inefficacy of her existing treatment, she has never

been evaluated concerning her suitability for surgery. Instead,

despite their knowledge that Delontas therapy sessions with

Psychologist Lang actually provoked her "overwhelming"

urges to self-castrate, VDOCs medical staffs only response

to Delontas requests for surgery was a "request that you

continue to work with Ms. Lang in individual therapy at this

time." These factual allegations, taken as true, state a plausible claim that Appellees "actually kn[e]w of and disregard[ed]" Delontas serious medical need in contravention of the

Eighth Amendment. Delonta I, 330 F.3d at 634 (quoting Farmer, 511 U.S. at 837).

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

11

We reject Appellees conclusionone shared by the district courtthat "[b]y alleging that [Appellees] have actively

participated in providing treatment directed to [Delontas]

urges to self-mutilate, [Delonta] has necessarily failed to

state a plausible claim that [Appellees] were deliberately

indifferent to that risk." Appellees Br. at 18; see Delonta II,

2011 WL 5157262, at *5. We do, of course, acknowledge that

Appellees have provided Delonta with some measure of

treatment to alleviate her GID symptoms. But just because

Appellees have provided Delonta with some treatment consistent with the GID Standards of Care, it does not follow that

they have necessarily provided her with constitutionally adequate treatment. See Delonta I, 330 F.3d at 635-36; Langford

v. Norris, 614 F.3d 445, 460 (8th Cir. 2010) ("[A] total deprivation of care is not a necessary condition for finding a constitutional violation: Grossly incompetent or inadequate care

can [also] constitute deliberate indifference . . . ." (internal

quotation omitted) (second alteration in original)).

By analogy, imagine that prison officials prescribe a

painkiller to an inmate who has suffered a serious injury from

a fall, but that the inmates symptoms, despite the medication,

persist to the point that he now, by all objective measure,

requires evaluation for surgery. Would prison officials then be

free to deny him consideration for surgery, immunized from

constitutional suit by the fact they were giving him a painkiller? We think not. Accordingly, although Appellees and the

district court are correct that a prisoner does not enjoy a constitutional right to the treatment of his or her choice,4 the treat4

We have explained that in this context the "essential test is one of medical necessity and not simply that which may be considered desirable,"

Bowring v. Godwin, 551 F.2d 44, 48 (4th Cir. 1977). In this vein, Appellees and the district court take pains to point out that, absent a doctors

recommendation, Delonta cannot show a demonstrable need for sex reassignment surgery. However, we struggle to discern how Delonta could

have possibly satisfied that condition when, as she alleges, Appellees have

never allowed her to be evaluated by a GID specialist in the first place.

12

DELONTA v. JOHNSON

ment a prison facility does provide must nevertheless be

adequate to address the prisoners serious medical need.

Likewise, we find no merit to Appellees argument that

Delontas previous settlement with VDOC "logically operates to refute subsequent Eighth Amendment claims because

the settlement repels any plausible claim of willful indifference to the condition." Appellees Br. at 22. The mere fact

that VDOC has previously acknowledged Delontas condition and agreed to provide treatment in no way forecloses the

possibility that its performance under that agreement later

became constitutionally deficient. See Cooper v. Dyke, 814

F.2d 941, 945 (4th Cir. 1987) (stating that "government officials who ignore indications that a prisoners or pretrial

detainees initial medical treatment was inadequate can be liable for deliberate indifference to medical needs.").

We wish to be clear about our holding. We hold only that

Delontas Eighth Amendment claim is sufficiently plausible

to survive screening pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1915A. We do

not decide today the merits of Delontas claim. Nor, for that

matter, do we mean to suggest what remedy Delonta would

be entitled to should she prevail. In our view, the answers to

those questions have no bearing on whether Delonta has

stated a claim that Appellees have been deliberately indifferent to her serious medical need by refusing to evaluate her for

surgery, consistent with the Standards of Care.

III.

For the reasons set forth above, we reverse the district

courts dismissal of Delontas Eighth Amendment claim and

remand the case for further proceedings.

REVERSED AND REMANDED

You might also like

- HWH Book PDFDocument167 pagesHWH Book PDFJesus Aguilar100% (1)

- ORE Application FormDocument24 pagesORE Application FormNahelMoskvaNo ratings yet

- Sample Case Study Counselling Bachelor DegreeDocument16 pagesSample Case Study Counselling Bachelor Degreescholarsassist75% (4)

- Rethinking Sex and GenderDocument3 pagesRethinking Sex and GenderBibhash Vicky Thakur100% (1)

- JADT Vol18 n3 Fall2006 Bak Mullenix Rossini StriffDocument96 pagesJADT Vol18 n3 Fall2006 Bak Mullenix Rossini StriffsegalcenterNo ratings yet

- R.W. v. Georgia Board of Regents - Order On Motions For Summary JudgmentDocument54 pagesR.W. v. Georgia Board of Regents - Order On Motions For Summary JudgmentJames RadfordNo ratings yet

- (Advances in Genetics 75) Robert Huber, Danika L. Bannasch and Patricia Brennan (Eds.) - Aggression-Academic Press, Elsevier (2011) PDFDocument291 pages(Advances in Genetics 75) Robert Huber, Danika L. Bannasch and Patricia Brennan (Eds.) - Aggression-Academic Press, Elsevier (2011) PDFbujor2000ajaNo ratings yet

- Skin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroDocument15 pagesSkin Culture and Psychoanalysis-IntroAnonymous Dgn6TCsbB100% (1)

- Hospital Birth PlanDocument2 pagesHospital Birth PlanYuniar Cahyania IntaniNo ratings yet

- Cordellione V INDOCDocument10 pagesCordellione V INDOCIndiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- Taylor LawsuitDocument7 pagesTaylor LawsuitHouston ChronicleNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id2208033Document71 pagesSSRN Id2208033Marcus VinsonNo ratings yet

- O'Connor v. Donaldson CaseDocument1 pageO'Connor v. Donaldson CaseKoj LozadaNo ratings yet

- De'Lonta v. Angelone, 4th Cir. (2003)Document9 pagesDe'Lonta v. Angelone, 4th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Thomas, Cheney v. Georgia Department of Community Health, Et AlDocument36 pagesThomas, Cheney v. Georgia Department of Community Health, Et AlNewsChannel 9 StaffNo ratings yet

- Todd v. Bigelow, 10th Cir. (2012)Document6 pagesTodd v. Bigelow, 10th Cir. (2012)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesLiterature Reviewapi-580070141No ratings yet

- Advance Directive AccessibilityDocument34 pagesAdvance Directive Accessibilityamir ghasemifareNo ratings yet

- ACLU of Florida - DoC LawsuitDocument31 pagesACLU of Florida - DoC LawsuitUnited Press International100% (1)

- Research Reportwiener1998Document12 pagesResearch Reportwiener1998maglangitmarvincNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: On Rehearing en Banc PublishedDocument60 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: On Rehearing en Banc PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Civil Rights Complaint For LGBT Immigration DetaineesDocument32 pagesCivil Rights Complaint For LGBT Immigration DetaineesLGBT Asylum NewsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Annette Whitton v. Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 11th Cir. (2016)Document12 pagesAnnette Whitton v. Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 11th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- E. Michalak - Reserved Remedy Tribunal DecisionDocument44 pagesE. Michalak - Reserved Remedy Tribunal DecisionCaptain WalkerNo ratings yet

- Malpractice and Negligence - EditedDocument5 pagesMalpractice and Negligence - Editedwafula stanNo ratings yet

- Kimberly Kessler Competent To Stand TrialDocument10 pagesKimberly Kessler Competent To Stand TrialAnne SchindlerNo ratings yet

- Transgender Employee Sues Library, Insurance ProviderDocument14 pagesTransgender Employee Sues Library, Insurance ProviderJamesNo ratings yet

- Group 6Document7 pagesGroup 6api-348458995No ratings yet

- Legmed Case DigestsDocument12 pagesLegmed Case DigestsAngelica PulidoNo ratings yet

- VA Whistleblower Alleges Discrimination For Exposing EvidenceDocument39 pagesVA Whistleblower Alleges Discrimination For Exposing EvidenceWKYC.comNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument54 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Centro Tepeyac v. Montgomery County, 4th Cir. (2013)Document38 pagesCentro Tepeyac v. Montgomery County, 4th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 2016 Virginia Medical Law ReportDocument12 pages2016 Virginia Medical Law ReportMichael DuntzNo ratings yet

- Case 2:12-cv-02497-KJM-EFB Document 27 Filed 10/22/12 Page 1 of 18Document18 pagesCase 2:12-cv-02497-KJM-EFB Document 27 Filed 10/22/12 Page 1 of 18Equality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument7 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NOE - Sexual Abuse of Clients A Contiuning Concern in The Helping Professions PDFDocument2 pagesNOE - Sexual Abuse of Clients A Contiuning Concern in The Helping Professions PDFBerta RNo ratings yet

- David Rutherford v. Richard S. Schweiker, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Defendant, 685 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1982)Document9 pagesDavid Rutherford v. Richard S. Schweiker, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Defendant, 685 F.2d 60, 2d Cir. (1982)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Legal-2Document9 pagesResearch Paper Legal-2Jonathan TranNo ratings yet

- SPLC Ashley Diamond Demand LetterDocument4 pagesSPLC Ashley Diamond Demand LetterMatt HennieNo ratings yet

- Carter V. Canada (Attorney General) : 2.1 Terminology: "Physician-Assisted Dying" Versus "Physician Assisted Suicide"Document9 pagesCarter V. Canada (Attorney General) : 2.1 Terminology: "Physician-Assisted Dying" Versus "Physician Assisted Suicide"angelieeecNo ratings yet

- Not PrecedentialDocument19 pagesNot PrecedentialScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LEGMED CaseDocument16 pagesLEGMED CaseGabriel Jhick SaliwanNo ratings yet

- Assisted Suicide Debate Script For Legal ConceptsDocument3 pagesAssisted Suicide Debate Script For Legal ConceptsKohryuNo ratings yet

- Legal and Ethical Aspect of Medical Emergencies: DR - Herkutanto, SH, FACLMDocument50 pagesLegal and Ethical Aspect of Medical Emergencies: DR - Herkutanto, SH, FACLMAVG2011No ratings yet

- C.G., Et Al v. Walden, Geo Group, CorizonDocument15 pagesC.G., Et Al v. Walden, Geo Group, CorizoncjciaramellaNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument11 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Curtis Thrower v. Oscar Alvies, 3rd Cir. (2011)Document7 pagesCurtis Thrower v. Oscar Alvies, 3rd Cir. (2011)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 14 ResubmissionDocument7 pagesChapter 14 ResubmissionMahima SikdarNo ratings yet

- Dancy v. Gee, 4th Cir. (2002)Document5 pagesDancy v. Gee, 4th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Blood Transfusion and Jehovas WitnessesDocument5 pagesBlood Transfusion and Jehovas WitnessesNicole GonzalesNo ratings yet

- ParsonsDocument63 pagesParsonswashlawdailyNo ratings yet

- Case Synthesis: MEDICAL MALPRACTICEDocument5 pagesCase Synthesis: MEDICAL MALPRACTICERegina Via G. Garcia0% (1)

- Rosit and Borromeo CasesDocument2 pagesRosit and Borromeo CasesbertobalicdangNo ratings yet

- Dr. H. M. Don v. Okmulgee Memorial Hospital, A Charitable Institution, Defendants, 443 F.2d 234, 10th Cir. (1971)Document8 pagesDr. H. M. Don v. Okmulgee Memorial Hospital, A Charitable Institution, Defendants, 443 F.2d 234, 10th Cir. (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- What Can You Do If Someone Refuses Medication - Eft Update Mar 2011Document6 pagesWhat Can You Do If Someone Refuses Medication - Eft Update Mar 2011Pooja GuptaNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Eleventh CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Euthanasia Revisited: DVK Chao, NY Chan and WY ChanDocument7 pagesEuthanasia Revisited: DVK Chao, NY Chan and WY Chananna.critchellNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument54 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Dillard, 10th Cir. (2015)Document34 pagesUnited States v. Dillard, 10th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 31, Docket 92-7386Document2 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: No. 31, Docket 92-7386Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Valentine v. Nettles, 4th Cir. (2007)Document3 pagesValentine v. Nettles, 4th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- American College of Pediatricians ComplaintDocument81 pagesAmerican College of Pediatricians ComplaintMary Margaret OlohanNo ratings yet

- MTD DoyleDocument17 pagesMTD DoyleLindsey KaleyNo ratings yet

- Confidentiality In Clinical Social Work: An Opinion of the United States Supreme CourtFrom EverandConfidentiality In Clinical Social Work: An Opinion of the United States Supreme CourtNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lopez, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Lopez, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Communication Takes Many Forms: Communication-When We're Talking About Animal Behavior-Can Be Any Process WhereDocument7 pagesCommunication Takes Many Forms: Communication-When We're Talking About Animal Behavior-Can Be Any Process WhereOcky Nindy MonsrezNo ratings yet

- Minor Research Project On HISTORICAL STUDY OF PROSTITUTION TRADE IN INDIA PAST AND PRESENTDocument178 pagesMinor Research Project On HISTORICAL STUDY OF PROSTITUTION TRADE IN INDIA PAST AND PRESENTRahul K BurmanNo ratings yet

- pdf2222Document3 pagespdf2222Life Is AwesomeNo ratings yet

- Sexual Reproduction Advs and DisadvsDocument10 pagesSexual Reproduction Advs and DisadvsMakanaka SambureniNo ratings yet

- Chastity - Jason EvertDocument14 pagesChastity - Jason EvertEmmanuel EstabilloNo ratings yet

- The Dangers of Social MediaDocument15 pagesThe Dangers of Social Medialorein arroyoNo ratings yet

- Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create DifferenceDocument4 pagesCordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: How Our Minds, Society, and Neurosexism Create Difference156majamaNo ratings yet

- Atlas Normal Squamous CellsDocument34 pagesAtlas Normal Squamous CellsChristian Rodriguez100% (1)

- Charm The Pants Off Any WomanDocument93 pagesCharm The Pants Off Any WomanRonWells100% (1)

- Bonus Chapter 48a Young Girl Incest VictimDocument31 pagesBonus Chapter 48a Young Girl Incest VictimSTBWNo ratings yet

- Zucker2005-Gender Identity Disorder in Children and AdolescentsDocument28 pagesZucker2005-Gender Identity Disorder in Children and AdolescentsCellaNo ratings yet

- Reflect Engligh 12Document4 pagesReflect Engligh 12api-376023160No ratings yet

- Gulags Without Guards: BrownDocument36 pagesGulags Without Guards: BrownsalisoftNo ratings yet

- Attwood - 2007 - No Money Shot Commerce, Pornography and New Sex Taste CulturesDocument16 pagesAttwood - 2007 - No Money Shot Commerce, Pornography and New Sex Taste Culturesalmendras_amargasNo ratings yet

- Free Movies Young Porn Frazer That The Brain. Dr. NorDocument4 pagesFree Movies Young Porn Frazer That The Brain. Dr. NornancirippeonNo ratings yet

- Ways To Stop Child AbuseDocument9 pagesWays To Stop Child Abuseapi-254124410No ratings yet

- The Differences Between Asexual and Sexual ReproductionDocument2 pagesThe Differences Between Asexual and Sexual ReproductionAmirul IkhwanNo ratings yet

- Androgyny and Sex-Typing - Differences in Beliefs Regarding Gender Polarity in Ratings of Ideal Men and WomenDocument11 pagesAndrogyny and Sex-Typing - Differences in Beliefs Regarding Gender Polarity in Ratings of Ideal Men and WomenJean CarloNo ratings yet

- PrenatalDocument5 pagesPrenataljojettelabanonNo ratings yet

- Flowers & Insects, Lists of Visitors To 453 Flowers, 1928, RobertsonDocument234 pagesFlowers & Insects, Lists of Visitors To 453 Flowers, 1928, RobertsonVan_KiserNo ratings yet

- Complaint Affidavit AAADocument12 pagesComplaint Affidavit AAAJoedhel ApostolNo ratings yet

- Sex Clubs Non Monogamy and GameDocument120 pagesSex Clubs Non Monogamy and Gameyhcrxv6n3j13100% (1)

- Sexting Scripts in Adolescent Relationships: Is Sexting Becoming The Norm?Document22 pagesSexting Scripts in Adolescent Relationships: Is Sexting Becoming The Norm?yakugune21No ratings yet