Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mastro v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (2001)

Mastro v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (2001)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mastro v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (2001)

Mastro v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (2001)

Uploaded by

Scribd Government DocsCopyright:

Available Formats

UNPUBLISHED

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

PATRICIA A. MASTRO,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

KENNETH S. APFEL, COMMISSIONER OF

SOCIAL SECURITY,

Defendant-Appellee.

No. 00-1105

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of North Carolina, at Bryson City.

Lacy H. Thornburg, District Judge.

(CA-99-11-2-T)

Argued: November 1, 2000

Decided: July 5, 2001

Before LUTTIG and TRAXLER, Circuit Judges, and

Alexander WILLIAMS, Jr., United States District Judge

for the District of Maryland, sitting by designation.

Affirmed by unpublished per curiam opinion.

COUNSEL

ARGUED: Jimmy Alan Pettus, Charlotte, North Carolina, for Appellant. Joseph L. Brinkley, Assistant United States Attorney, Charlotte,

North Carolina, for Appellee. ON BRIEF: Mark T. Calloway, United

States Attorney, Charlotte, North Carolina, for Appellee.

MASTRO v. APFEL

Unpublished opinions are not binding precedent in this circuit. See

Local Rule 36(c).

OPINION

PER CURIAM:

Patricia Mastro, Appellant, challenges the decision of the Commissioner of Social Security ("Commissioner") denying her application

for disability insurance benefits and supplemental security income

benefits. Her claimed disability is Chronic Fatigue Immune Dysfunction Syndrome ("CFIDS"), also known as Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

("CFS"). After a hearing, the administrative law judge (ALJ) ruled

that Ms. Mastro was not entitled to a period of disability or disability

insurance under 216(1) and 223 of the Social Security Act ("the

Act"), nor was she eligible for supplemental security income under

1602 and 1614(a)(3)(A) of the Act. Ms. Mastros appeal of this

decision was denied by the Appeals Council. She then sought judicial

review. Upon reviewing cross-motions for summary judgment, the

District Court of North Carolina granted the Commissioners motion

and denied Ms. Mastros motion. For the reasons discussed below, we

affirm the ALJs findings and his determination that Ms. Mastro is not

disabled under the Act.

I. FACTUAL BACKGROUND

Patricia Mastro is a female over the age of 55. From 1978 to 1994,

Ms. Mastro worked in a number of occupations, including administrative, service, property and restaurant management positions. Her last

full-time position, as a secretary, ended in April 1992. Thereafter, she

was employed part-time as a driver and a store manager. In September 1994, she resigned from her position as a waitress after six weeks

on the job. Thereafter, Ms. Mastro stopped working completely. Ms.

Mastro first applied for social security disability benefits and supplemental security income on June 5, 1995. She alleged the disability of

CFS, with the date of disability commencing on April 1, 1992.

According to Ms. Mastro, she began experiencing symptoms of CFS

as early as October 1985. Her medical history is summarized below.

MASTRO v. APFEL

A. Medical History

In February 1986, Dr. Michael Morkis treated Ms. Mastro for a

benign adenoma which led to the surgical excision of a left facial

tumor. A year later, in March of 1987, Ms. Mastro was diagnosed

with menomenorrhagia, fibroids, adhesions, hydrosalpinx, and

chronic endometris. The medical records from these procedures

revealed no complaints of chronic fatigue or other symptoms of CFS

in the pre- or post-operative treatment.

From August 1988 through September 1993, Ms. Mastro sought

treatment at a Florida hospital on approximately six occasions. In

August 1988, Ms. Mastro complained of chest and neck soreness in

the aftermath of a motor vehicle accident. Upon her second visit, she

reported that her condition had improved. She was physically examined and diagnosed with degenerative arthritis. Two years later, in

June 1990, Ms. Mastro was treated by Dr. Edward Cabrera on two

occasions. Her reported complaints included being very tired, dull

chest pain, dizziness, and bilateral arm pain. Dr. Cabreras observations included scattered rhonchi, decreased breath sounds, and

midepigastric tenderness. He noted that Ms. Mastro experienced

decreased cognitive functioning and confusion as well. Based upon

his observations and Ms. Mastros reported symptoms, Dr. Cabrera

diagnosed Ms. Mastro with CFS by history. Dr. Cabreras examination also produced an abnormal thyroid test. Dr. Cabrera prescribed

Prozac and Klonopin. On a follow-up visit two weeks later, Ms.

Mastro did not complain of any further CFS symptoms. In October

1992, Ms. Mastro sought treatment for migraine headaches and was

prescribed medication. In a gynecological examination performed that

same month, Ms. Mastro complained of tiredness to a Dr. Phillips. In

December 1992, Ms. Mastro complained of abdominal discomfort

and was treated for diarrhea. A year later, in September 1993, Ms.

Mastro underwent another physical examination. She reported being

tired and having CFS.

In September 1994, Ms. Mastro was treated for dizziness and chest

pains. The tests performed revealed normal results. In January 1995,

Ms. Mastro sought treatment from Dr. J.F. Templeman. In the course

of her treatment, she reported symptoms that included: fatigue,

migraines, restless legs, depression, insomnia, rashes, sinus problems,

MASTRO v. APFEL

CFS, chest pains, yeast infections, and migratory joint pains. Dr.

Templeman diagnosed her with costochondritis, restless leg syndrome, and CFS. In June 1995, Ms. Mastro underwent another physical examination reporting symptoms such as chronic fatigue,

insomnia, and restless legs. The physical examination did not reveal

any abnormal conditions.

In November 1995, Ms. Mastro sought treatment for migraine

headaches, depression, and upper body discomfort aggravated by

movement or coughing. Dr. John S. Muller, a clinical psychologist,

performed a psychological examination on Ms. Mastro. The administered intelligence test revealed that Ms. Mastro was of average intelligence. Dr. Muller described Ms. Mastro as "alert and oriented" with

no noticeable depressive affect. However, Dr. Muller summarized her

condition as symptomatic of CFS. He noted that she suffered from a

low energy level and that she lost four jobs due to CFS symptoms,

such as fatigue, falling asleep on the job, and absenteeism. In 1996,

Ms. Mastro was treated by Dr. Rick Pekarek for cellulitis with lymphangitis that developed from a knee scratch. She reported symptoms

of CFS. In July 1996, Ms. Mastro was treated for gastritis, diarrhea,

and a yeast infection. Each of these conditions was treated by different medications.

In March 1997, Dr. Charles E. Fitzgerald examined Ms. Mastro.

He found that, although Ms. Mastros reported symptoms were consistent with CFS, she suffered from no physical impairment that

would limit her activities. In a letter dated that same year, Dr. Templeman reiterated his opinion that Ms. Mastro suffered from CFS and

that the condition prevented her from working productively. Dr. Templeman noted that, "based upon her history, [Ms. Mastro] would be

unable medically to work or study on a regular basis. A few hours of

effort at a time would be all she is capable of and this on an irregular

basis." (Appellants Br. at 6.) Dr. Templemans diagnosis was based

upon Ms. Mastros past medical history and her reported symptoms

over the course of her treatment.

B. Subjective Complaints and Daily Activities

In Dr. Mullers psychological evaluation, Ms. Mastro reported that

she suffered from depression due to her CFS. She claimed that, in

MASTRO v. APFEL

January 1986, she was diagnosed with Epstin-Barr disorder (a prior

term used to describe CFS). However, no medical records from the

1986 surgery substantiate this claim. Although her employment

included secretarial and management positions, she reported that she

could not retain her job as a secretary because she "found it difficult

to remember [tasks] and occasionally fell asleep at her desk." (J.A. at

218.) She described her sleep patterns as erratic with bouts of insomnia. On a typical day, she may read a book, write a letter, sew, or

watch television. However, Ms. Mastro claimed that she engages in

these activities less frequently and for shorter periods due to her

diminished concentration. She reported taking two naps a day lasting

approximately fifteen minutes to two hours. She occasionally cooks

simple meals for herself and her roommate. She can perform light

housework, such as dry mopping and dusting. In her testimony at the

ALJ hearing, Ms. Mastro stated that the extent of her daily activities

depends on whether she had a good day or a bad day. She testified

that, even if she has a "good" day, it is typically followed by two or

three "bad" days. According to her testimony, on her worst days, Ms.

Mastro does not have the energy to shower, read, or watch television.

She remains in bed and sleeps. She complained that she cannot sit for

more than thirty minutes or stand in excess of twenty minutes without

experiencing pain and fatigue.

C. ALJ Findings

The ALJ found that the medical examinations of Ms. Mastro prior

to 1995 did not support her subjective complaints of pain and fatigue.

The ALJ noted that Ms. Mastros history of CFS was based on her

own subjective complaints of pain and fatigue and no doctor found a

definitive basis for diagnosing her with CFS. From this, the ALJ

stated that "it is clear that the claimant has no impairment or combination of impairments" entitling her to social security disability benefits.

(J.A. at 27.) Further, the ALJ reasoned that the objective medical evidence and Ms. Mastros daily life activities indicated that she could

continue to perform past relevant work, particularly management

positions. Given these findings, the ALJ denied her disability claim.

Additionally, the ALJ found no evidence of a medically determinable

mental impairment.

As grounds for reversal, Ms. Mastro contends that the ALJ erroneously ignored the opinion of her treating physician and her subjective

MASTRO v. APFEL

complaints of chronic fatigue and pain. The Commissioner does not

dispute that Ms. Mastro suffers from a severe impairment. Rather, the

Commissioner maintains that the ALJs findings that Ms. Mastros

impairment was not among the listed impairments recognized as disabling and that the impairment did not limit her from engaging in certain past employment, such as real estate management, are supported

by substantial evidence and based upon the correct application of law.

II. DISCUSSION

This Court is authorized to review the Commissioners denial of

benefits under 42 U.S.C. 405(g) and 1383(c)(3). "Under the Social

Security Act, [a reviewing court] must uphold the factual findings of

the Secretary if they are supported by substantial evidence and were

reached through application of the correct legal standard." Craig v.

Chater, 76 F.3d 585, 589 (4th Cir. 1996). "Substantial evidence is . . .

such relevant evidence as a reasonable mind might accept as adequate

to support a conclusion." Richardson v. Perales, 402 U.S. 389, 401

(1971). "[I]t consists of more than a mere scintilla of evidence but

may be somewhat less than a preponderance." Laws v. Celebrezze,

368 F.2d 640, 642 (4th Cir. 1966). "In reviewing for substantial evidence, [the court should not] undertake to re-weigh conflicting evidence, make credibility determinations, or substitute [its] judgment

for that of the Secretary." Craig, 76 F.3d at 589.

Sections 216(i) and 1614(a)(3) of the Act define "disability" as the

inability to engage in any substantial gainful activity (SGA) by reason

of any medically determinable physical or mental impairment (or

combination of impairments) which can be expected to result in death

or which has lasted or can be expected to last for a continuous period

of not less than 12 months. 42 U.S.C. 423 (d)(1)(A). In Social

Security Ruling (SSR) 99-2p, the Commissioner definitively stated

that, when accompanied by appropriate medical signs or laboratory

findings, CFS can be a medically determinable impairment. SSR 992p, Titles II and XVI: Evaluating Cases Involving Chronic Fatigue

Syndrome (CFS), 64 Fed. Reg. 23380, 23381 (April 30, 1999) (hereinafter "SSR 99-2p"). The ruling defines CFS as:

a systemic disorder consisting of a complex of symptoms

that may vary in incidence, duration, and severity . . . char-

MASTRO v. APFEL

acterized in part by prolonged fatigue that lasts 6 months or

more and that results in substantial reduction in previous

levels of occupational, educational, social, or personal activities.

SSR 99-2p, 64 Fed. Reg. at 23381. The ruling instructs that, before

rejecting a claim based on CFS, the ALJ must first consider the medical evidence and evaluate the condition as any other unlisted impairment. Therefore, the CFS claim is analyzed under the same five step

framework applied to every social security disability claim. See 20

C.F.R. 416.920.

The five step analysis begins with the question of whether the

claimant engaged in substantial gainful employment. 20 C.F.R.

404.1520(b). If not, the analysis continues to determine whether,

based upon the medical evidence, the claimant has a severe impairment. 20 C.F.R. 404.1520(c). If the claimed impairment is sufficiently severe, the third step considers whether the claimant has an

impairment that equals or exceeds in severity one or more of the

impairments listed in Appendix I of the regulations. 20 C.F.R.

404.1520(d); 20 C.F.R. Part 404, subpart P, App.I. If so the claimant is disabled. If not, the next inquiry considers if the impairment

prevents the claimant from returning to past work. 20 C.F.R.

404.1520(e); 20 C.F.R. 404.1545(a). If the answer is in the affirmative, the final consideration looks to whether the impairment precludes the claimant from performing other work. 20 C.F.R.

404.1520(f).

While the Act and regulations require that an impairment be established by objective medical evidence that consists of signs, symptoms, and laboratory findings, and not only by an individuals

statement of symptoms, 42 U.S.C. 423(d)(5)(A), the Commissioner

recognizes that "no specific etiology or pathology has yet been established for CFS." SSR 99-2p, 64 Fed. Reg. at 23381. Still, the Commissioners directive in SSR 99-2p explicitly requires a CFS

disability claim to be accompanied by medical signs or laboratory

findings. SSR 99-2p, 64 Fed. Reg. at 23381. Recognized examples of

medical signs, clinically documented over a period of at least 6 consecutive months, that will establish the existence of a medically determinable impairment include: palpably swollen or tender lymph nodes

MASTRO v. APFEL

on physical examination; nonexudative pharyngitis; persistent, reproducible muscle tenderness on repeated examinations or any other

medical signs that are consistent with medically accepted clinical

practice and are consistent with the other evidence in the case record.

SSR 99-2p, 64 Fed. Reg. at 23382. Accordingly, to support an award

of benefits, the medical signs must fall within the listed physical

symptoms or be consistent with medically accepted clinical practice

and the other evidence in the record. Furthermore, these symptoms

must have been clinically documented over a period of at least six

consecutive months. In the present case, we conclude the ALJ properly took such issues into consideration in coming to his conclusion

that Ms. Mastro did not establish an entitlement to benefits.

A. Severity of Impairment

While the ALJ found that Ms. Mastro suffered from CFS, he concluded that her impairment was not sufficiently severe to equal or

exceed any impairment or combination of impairments listed in

Appendix I, Subpart P, Regulations No. 4. The ALJ based his decision on the fact that Ms. Mastros CFS history was based largely on

her own subjective complaints of muscle aches, pain, weakness, and

fatigue. The ALJ also pointed to the lack of a definitive basis for any

doctors diagnosis for CFS.

As initial grounds for error, Ms. Mastro maintains that the ALJ

erred in rejecting the testimony of her treating physician, Dr. Templeman. The Commissioner argues that the ALJ correctly afforded the

medical opinion of Dr. Templeman little weight given that he based

his opinion on the subjective complaints of Ms. Mastro without sufficient evidence to substantiate her claims. "Although the treating physician rule generally requires a court to accord greater weight to the

testimony of a treating physician, the rule does not require that the

testimony be given controlling weight." Hunter v. Sullivan, 993 F.2d

31, 35 (4th Cir. 1992) (per curiam). Rather, according to the regulations promulgated by the Commissioner, a treating physicians opinion on the nature and severity of the claimed impairment is entitled

to controlling weight if it is well-supported by medically acceptable

clinical and laboratory diagnostic techniques and is not inconsistent

with the other substantial evidence in the record. See 20 C.F.R

416.927. Thus, "[b]y negative implication, if a physicians opinion

MASTRO v. APFEL

is not supported by clinical evidence or if it is inconsistent with other

substantial evidence, it should be accorded significantly less weight."

Craig, 76 F.3d at 590. Under such circumstances, the ALJ holds the

discretion to give less weight to the testimony of a treating physician

in the face of persuasive contrary evidence. See Hunter, 993 F.2d at

35.

We find the record adequately supports the ALJs decision to attribute greater weight to Dr. Fitzgeralds opinion over Dr. Templemans

finding of disability. First, Dr. Templemans opinion was communicated a year after his last treatment of Ms. Mastro. Second, the Commissioners ruling on CFS advises that "a physician should make a

diagnosis of CFS only after alternative medical and psychiatric

causes of chronic fatiguing illness have been excluded." SSR 99-2p,

64 Fed. Reg. at 23381 (quoting Annals of Internal Medicine, 121:9539, 1994). Dr. Templemans diagnosis was based largely upon the

claimants self-reported symptoms. Ms. Mastros laboratory tests and

medical examinations were within normal parameters. No other doctor that examined Ms. Mastro was of the opinion that she was disabled. The specified reasons of the ALJ properly considered the

absence of clinically documented medical evidence. We find no error

in the ALJs consideration of the year delay between Dr. Templemans diagnosis of CFS and opinion of disability and the absence of

supporting clinical documentation of symptoms. Such factors provide

specific and legitimate grounds to reject a treating physicians opinion

in the face of the conflicting evidence and the more contemporaneous

medical opinion of Dr. Fitzgerald. Thus, we find no error in the ALJs

decision to not to give Dr. Templemans opinion controlling weight.

Along similar lines, we agree that the substantial evidence supports

the ALJs findings as to the severity of Ms. Mastros claimed impairment. Inasmuch as CFS is not a listed impairment, an individual with

CFS alone cannot be found to have an impairment that meets the

requirements of a listed impairment. SSR 99-p2, 64 Fed. Reg. at

23382. As Ms. Mastros condition is not a listed impairment, the ALJ

must determine whether her "symptoms, signs, and laboratory findings [were] medically equal to the symptoms, signs, and laboratory

findings of a listed impairment" under Appendix I. 20 C.F.R.

404.1529. Such impairments are "considered severe enough to prevent a person from doing any gainful activity." 20 C.F.R. 404.1525.

10

MASTRO v. APFEL

"Medical equivalence must be based on medical findings . . . supported by medically acceptable clinical and laboratory diagnostic

techniques." 20 C.F.R. 404.1526(b). An ALJs evaluation of a

claimants subjective complaints of pain must "consider all . . . symptoms, including pain, and the extent to which [the] symptoms can reasonably be accepted as consistent with the objective medical

evidence." 20 C.F.R. 404.1529. While Ms. Mastro argues that the

ALJs analysis is inconsistent with SSR 99p-2, the Commissioners

ruling on CFS still requires

appropriate documentation . . . includ[ing] a longitudinal

clinical record of at least 12 months prior to the date of

application . . . . The record should contain detailed medical

observations, treatment, the individuals response to treatment, and a detailed description of how the impairment limits the individuals ability to function over time.

SSR 99-2p, 64 Fed. Reg. at 23383. While Dr. Cabrera first diagnosed

Ms. Mastro with CFS in June 1990, the record shows significant gaps

in the claimants treatment records until January 1995 when Dr. Templeman diagnosed Ms. Mastro with CFS. The medical records in

October 1992, September 1993, and September 1994 show that Ms.

Mastros complaints of fatigue, insomnia and migraines had persisted

over five years prior to her application in May 1995. Still, the record

does not reveal the detailed clinical record contemplated for a medical

diagnosis based upon symptoms. Rather, the record discloses a

hodgepodge of medical observations and treatments with annual gaps

showing no progression in Ms. Mastros treatment. Furthermore,

although Ms. Mastro contends that she sought treatment from Dr.

Templeman 25 times, there is no detailed account of his medical

observations, prescribed treatment, and Ms. Mastros responses

thereto. "Where conflicting evidence allows reasonable minds to differ as to whether a claimant is disabled, the responsibility for that

decision falls on the Secretary (or the ALJ)." Walker v. Bowen, 834

F.2d 635, 640 (7th Cir. 1987). Considering the paucity of medical evidence supporting her claim, we find that the ALJ applied the correct

legal standard in assessing the extent of Ms. Mastros impairment and

finding that her condition was not equal to one or more impairments

warranting a finding of disability.

MASTRO v. APFEL

11

B. Past Relevant Work

If a claimants impairment is not sufficiently severe to equal or

exceed a listed impairment, the ALJ must assess the claimants residual function capacity ("RFC"). RFC assesses the "maximum degrees

to which the individual retains the capacity for sustained performance

of the physical-mental requirements of jobs." 20 C.F.R. 404, Subpart

P, App.2 200.00(c). Ms. Mastro argues that the ALJ erred in finding

that she could perform past relevant work. As support for his opinion

that Ms. Mastro could perform past relevant work, the ALJ noted that

Ms. Mastro was able to ride her bike, walk in the woods, and travel

to places such as Indiana, Texas, and Georgia without significant difficulty. The ALJ reasoned that, in light of the negative clinical and

laboratory findings, the daily life activities showed that Ms. Mastros

subjective complaints of pain and fatigue could not reasonably be

expected in terms of intensity, frequency, or duration. We find that

the ALJ correctly applied the law in concluding that Ms. Mastros

reported daily activities undermined her subjective complaints of

chronic fatigue. We also agree that the determination is supported by

the substantial evidence. The ALJ properly considered Ms. Mastros

reported activities, prior work history, and Dr. Fitzgeralds opinion in

concluding that CFS did not limit Ms. Mastros ability to work. See

Gross v. Heckler, 785 F.2d 1163, 1166 (4th Cir. 1986).

After reviewing the record, we hold that the substantial evidence

supports the ALJs determination that Ms. Mastro is not disabled

within the meaning of the Social Security Act. Accordingly, we

affirm the district courts grant of summary judgment in favor of the

Commissioner on the denial of disability benefits.

AFFIRMED

You might also like

- NCM 107 Module 2M Ethico Moral Aspects of NursingDocument18 pagesNCM 107 Module 2M Ethico Moral Aspects of NursingTrisha ApillanesNo ratings yet

- Report of Medical Examination and Vaccination RecordDocument14 pagesReport of Medical Examination and Vaccination RecordHrishi WaghNo ratings yet

- Neurology Fam Med CiricullumDocument381 pagesNeurology Fam Med CiricullumbajariaaNo ratings yet

- Janice Newell v. Commissioner of Social Security, 347 F.3d 541, 3rd Cir. (2003)Document12 pagesJanice Newell v. Commissioner of Social Security, 347 F.3d 541, 3rd Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Zumwalt v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2007)Document21 pagesZumwalt v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2007)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Miller v. Chater, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1996)Document10 pagesMiller v. Chater, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Irma G. Horney v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 927 F.2d 596, 4th Cir. (1991)Document6 pagesIrma G. Horney v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 927 F.2d 596, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Tsoulas v. Liberty Life, 454 F.3d 69, 1st Cir. (2006)Document14 pagesTsoulas v. Liberty Life, 454 F.3d 69, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Constance Guice-Mills v. Edward J. Derwinski, Secretary of The Department of Veterans Affairs, 967 F.2d 794, 2d Cir. (1992)Document6 pagesConstance Guice-Mills v. Edward J. Derwinski, Secretary of The Department of Veterans Affairs, 967 F.2d 794, 2d Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals: PublishedDocument16 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 32 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 482, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15893a Richard Matullo v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary, 926 F.2d 240, 3rd Cir. (1990)Document10 pages32 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 482, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15893a Richard Matullo v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary, 926 F.2d 240, 3rd Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Miracle v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2006)Document13 pagesMiracle v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Gerald L. Currier v. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 612 F.2d 594, 1st Cir. (1980)Document6 pagesGerald L. Currier v. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 612 F.2d 594, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 30 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 314, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15544a Janine A. Wagner v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 906 F.2d 856, 2d Cir. (1990)Document10 pages30 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 314, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15544a Janine A. Wagner v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 906 F.2d 856, 2d Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jones v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2013)Document24 pagesJones v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pearl Snell v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Society Security, 177 F.3d 128, 2d Cir. (1999)Document11 pagesPearl Snell v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Society Security, 177 F.3d 128, 2d Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 3 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 298, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15,007 George Mongeur v. Margaret Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 722 F.2d 1033, 2d Cir. (1983)Document12 pages3 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 298, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15,007 George Mongeur v. Margaret Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 722 F.2d 1033, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rios Vazquez v. SHHS, 1st Cir. (1995)Document15 pagesRios Vazquez v. SHHS, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Homosexuality Aversion Therapy: Case of Treated BYDocument3 pagesHomosexuality Aversion Therapy: Case of Treated BYIonelia PașaNo ratings yet

- 4 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 22, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15,021 Virginia Fiorello v. Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Defendant, 725 F.2d 174, 2d Cir. (1983)Document4 pages4 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 22, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 15,021 Virginia Fiorello v. Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, Defendant, 725 F.2d 174, 2d Cir. (1983)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument17 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 14 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 28, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,842 Linda Mason v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 791 F.2d 1460, 11th Cir. (1986)Document4 pages14 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 28, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,842 Linda Mason v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 791 F.2d 1460, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ellis v. Metropolitan Life, 4th Cir. (1997)Document19 pagesEllis v. Metropolitan Life, 4th Cir. (1997)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lareau v. Page, 1st Cir. (1994)Document29 pagesLareau v. Page, 1st Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Guilbe Santiago v. SHHS, 1st Cir. (1995)Document14 pagesGuilbe Santiago v. SHHS, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Roy Allen Murray v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 51 F.3d 267, 4th Cir. (1995)Document9 pagesRoy Allen Murray v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 51 F.3d 267, 4th Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jimmie Phillips v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 25 F.3d 1058, 10th Cir. (1994)Document8 pagesJimmie Phillips v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 25 F.3d 1058, 10th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 23 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 274, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 14235a Ramona Rivera-Figueroa v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 858 F.2d 48, 1st Cir. (1988)Document6 pages23 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 274, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 14235a Ramona Rivera-Figueroa v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 858 F.2d 48, 1st Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Merle C. Fowler v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, 596 F.2d 600, 3rd Cir. (1979)Document7 pagesMerle C. Fowler v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, 596 F.2d 600, 3rd Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sitara McGovern v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 953 F.2d 638, 4th Cir. (1992)Document3 pagesSitara McGovern v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 953 F.2d 638, 4th Cir. (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Taybron, Robert v. Patricia Harris, As Secretary of Health, Education & Welfare, 667 F.2d 412, 3rd Cir. (1981)Document6 pagesTaybron, Robert v. Patricia Harris, As Secretary of Health, Education & Welfare, 667 F.2d 412, 3rd Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rita Schaal v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Social Security, 1 Dockets 96-6212, 96-6316, 134 F.3d 496, 2d Cir. (1998)Document14 pagesRita Schaal v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Social Security, 1 Dockets 96-6212, 96-6316, 134 F.3d 496, 2d Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ben B. Beggs v. Anthony J. Celebrzze, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 356 F.2d 234, 4th Cir. (1966)Document4 pagesBen B. Beggs v. Anthony J. Celebrzze, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 356 F.2d 234, 4th Cir. (1966)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Madron v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2009)Document24 pagesMadron v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Renee S. Phillips v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, 357 F.3d 1232, 11th Cir. (2004)Document17 pagesRenee S. Phillips v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, 357 F.3d 1232, 11th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 17 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 497, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 17,354 Audette Kemp v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 816 F.2d 1469, 10th Cir. (1987)Document11 pages17 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 497, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 17,354 Audette Kemp v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 816 F.2d 1469, 10th Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 21 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 71, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 17,963 Lisa Tsarelka v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 842 F.2d 529, 1st Cir. (1988)Document9 pages21 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 71, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 17,963 Lisa Tsarelka v. Secretary of Health and Human Services, 842 F.2d 529, 1st Cir. (1988)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitDocument15 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Betty S. Coleman v. Caspar W. Weinberger, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare of The United States, 538 F.2d 1045, 4th Cir. (1976)Document4 pagesBetty S. Coleman v. Caspar W. Weinberger, Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare of The United States, 538 F.2d 1045, 4th Cir. (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Martinez v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2009)Document14 pagesMartinez v. Astrue, 10th Cir. (2009)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976)Document17 pagesEstelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- William Morales v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Social Security (D.c. Civ. No. 98-5022), 225 F.3d 310, 3rd Cir. (2000)Document14 pagesWilliam Morales v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner of Social Security (D.c. Civ. No. 98-5022), 225 F.3d 310, 3rd Cir. (2000)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Marjorie L. Stawls v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, 596 F.2d 1209, 4th Cir. (1979)Document7 pagesMarjorie L. Stawls v. Joseph A. Califano, JR., Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, 596 F.2d 1209, 4th Cir. (1979)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Ada M. Marshall v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 914 F.2d 248, 4th Cir. (1990)Document7 pagesAda M. Marshall v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 914 F.2d 248, 4th Cir. (1990)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Blea v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2006)Document26 pagesBlea v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 9 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 292, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,010 Henry F. Fulton, Jr. v. Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 760 F.2d 1052, 10th Cir. (1985)Document7 pages9 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 292, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,010 Henry F. Fulton, Jr. v. Margaret M. Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 760 F.2d 1052, 10th Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Justus v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1998)Document7 pagesJustus v. Apfel, Commissioner, 4th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledDocument13 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit: FiledScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dorothy McMillan v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Healthand Human Services, 35 F.3d 556, 4th Cir. (1994)Document4 pagesDorothy McMillan v. Donna E. Shalala, Secretary of Healthand Human Services, 35 F.3d 556, 4th Cir. (1994)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hanna Miles v. Patricia Harris, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 645 F.2d 122, 2d Cir. (1981)Document7 pagesHanna Miles v. Patricia Harris, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 645 F.2d 122, 2d Cir. (1981)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hollenbach v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2003)Document12 pagesHollenbach v. Barnhart, 10th Cir. (2003)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 14 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 140, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,864 Julia Dorf v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services of The United States, 794 F.2d 896, 3rd Cir. (1986)Document11 pages14 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 140, Unempl - Ins.rep. CCH 16,864 Julia Dorf v. Otis R. Bowen, Secretary of Health and Human Services of The United States, 794 F.2d 896, 3rd Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Genaro Quiles-Quiles v. William J. Henderson, Postmaster General, United States Postal Service, 439 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2006)Document10 pagesGenaro Quiles-Quiles v. William J. Henderson, Postmaster General, United States Postal Service, 439 F.3d 1, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Filed: Patrick FisherDocument22 pagesFiled: Patrick FisherScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Leigh Ayn D. Laurey v. Commissioner of Social Security, 11th Cir. (2015)Document25 pagesLeigh Ayn D. Laurey v. Commissioner of Social Security, 11th Cir. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Georgia C. Wyatt v. Caspar W. Weinberger, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 519 F.2d 1285, 4th Cir. (1975)Document5 pagesGeorgia C. Wyatt v. Caspar W. Weinberger, Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 519 F.2d 1285, 4th Cir. (1975)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 61 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 8, Unempl - Ins.rep. (CCH) P 16166b Hung Nguyen v. Shirley S. Chater, 172 F.3d 31, 1st Cir. (1999)Document6 pages61 Soc - Sec.rep - Ser. 8, Unempl - Ins.rep. (CCH) P 16166b Hung Nguyen v. Shirley S. Chater, 172 F.3d 31, 1st Cir. (1999)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Guilbe Santiago v. SHHS, 46 F.3d 1114, 1st Cir. (1995)Document6 pagesGuilbe Santiago v. SHHS, 46 F.3d 1114, 1st Cir. (1995)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Frances Sherman v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 141 F.3d 1185, 10th Cir. (1998)Document12 pagesFrances Sherman v. Kenneth S. Apfel, Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 141 F.3d 1185, 10th Cir. (1998)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Luis Guzman Diaz v. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 613 F.2d 1194, 1st Cir. (1980)Document10 pagesLuis Guzman Diaz v. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, 613 F.2d 1194, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Linda v. Cawthon v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 931 F.2d 886, 4th Cir. (1991)Document8 pagesLinda v. Cawthon v. Louis W. Sullivan, Secretary of Health and Human Services, 931 F.2d 886, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Shelley A. McGoffin v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 288 F.3d 1248, 10th Cir. (2002)Document8 pagesShelley A. McGoffin v. Jo Anne B. Barnhart, Commissioner, Social Security Administration, 288 F.3d 1248, 10th Cir. (2002)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesUnited States v. Garcia-Damian, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Olden, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- City of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Document21 pagesCity of Albuquerque v. Soto Enterprises, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesUnited States v. Muhtorov, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document50 pagesUnited States v. Roberson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Consolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Document22 pagesConsolidation Coal Company v. OWCP, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Document20 pagesUnited States v. Kieffer, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Apodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Document15 pagesApodaca v. Raemisch, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Harte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document100 pagesHarte v. Board Comm'rs Cnty of Johnson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Voog, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesPecha v. Lake, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- NM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesNM Off-Hwy Vehicle Alliance v. U.S. Forest Service, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument10 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument14 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government Docs100% (1)

- United States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Kearn, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument24 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document27 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document2 pagesUnited States v. Henderson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Document25 pagesUnited States v. Windom, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Document7 pagesUnited States v. Kundo, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Jimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesJimenez v. Allbaugh, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Magnan, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesPledger v. Russell, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Publish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitDocument17 pagesPublish United States Court of Appeals For The Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Northern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document10 pagesNorthern New Mexicans v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Coburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Document9 pagesCoburn v. Wilkinson, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Chevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document42 pagesChevron Mining v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Robles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Document5 pagesRobles v. United States, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- United States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Document4 pagesUnited States v. Purify, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Parker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Document24 pagesParker Excavating v. LaFarge West, 10th Cir. (2017)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Lecture Nursing Communicable Disease EpidemiologyDocument32 pagesLecture Nursing Communicable Disease EpidemiologyvolaaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On Peptic UlcerDocument7 pagesLesson Plan On Peptic UlcerVeenasravanthiNo ratings yet

- Curriculum VITAE Za Tesni Aplikacii Na Web.Document3 pagesCurriculum VITAE Za Tesni Aplikacii Na Web.mila vidinNo ratings yet

- Eapp M2Document10 pagesEapp M2lezner yamNo ratings yet

- Case Study-Chronic TonsillitisDocument7 pagesCase Study-Chronic TonsillitisJonalyn TumanguilNo ratings yet

- DDU (General) Syllabus: Diploma of Diagnostic Ultrasound (DDU)Document19 pagesDDU (General) Syllabus: Diploma of Diagnostic Ultrasound (DDU)MitchNo ratings yet

- Pediatric EndrocinologyDocument453 pagesPediatric Endrocinologyrayx323100% (2)

- Cervical Punch Biopsy PILDocument2 pagesCervical Punch Biopsy PILAna BicosNo ratings yet

- G. Vrbová (Auth.), Professor Dr. W. A. Nix, Professor Dr. G. Vrbová (Eds.) - Electrical Stimulation and Neuromuscular Disorders-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1986)Document148 pagesG. Vrbová (Auth.), Professor Dr. W. A. Nix, Professor Dr. G. Vrbová (Eds.) - Electrical Stimulation and Neuromuscular Disorders-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1986)Harshavardhan SNo ratings yet

- Tri Kartika Setyarini, Aisyah Lahdji, Isna Zalwa Noor FajriDocument7 pagesTri Kartika Setyarini, Aisyah Lahdji, Isna Zalwa Noor Fajrisurya gunawanNo ratings yet

- Daftar Pustaka Makalah Tahap IDocument2 pagesDaftar Pustaka Makalah Tahap IAulina Refri RahmiNo ratings yet

- Poli PerDocument544 pagesPoli Perfadhillah islamyahprNo ratings yet

- AD RealMind BiotechDocument4 pagesAD RealMind Biotechlinjinxian444No ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument16 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentDavid LeeNo ratings yet

- LidocaineDocument11 pagesLidocaineStanford AnesthesiaNo ratings yet

- Plant Micropropagation: Section (9) Lab (B) Number (50:60)Document14 pagesPlant Micropropagation: Section (9) Lab (B) Number (50:60)Nada SamiNo ratings yet

- For RRLDocument3 pagesFor RRLRiyn FaeldanNo ratings yet

- Parasitic Adaptation PDFDocument6 pagesParasitic Adaptation PDFmubarik Hayat50% (2)

- Reflection On Musculoskeletal SystemDocument3 pagesReflection On Musculoskeletal SystemRalph de la TorreNo ratings yet

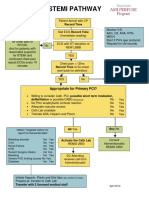

- Stemi Pathway: Record TimeDocument2 pagesStemi Pathway: Record TimeOlga Jadha CasmiraNo ratings yet

- What Is The Objective of Endurance TrainingDocument5 pagesWhat Is The Objective of Endurance TrainingNaveed WarraichNo ratings yet

- Insulin Pump SimulatorDocument13 pagesInsulin Pump SimulatorVivek KaliannanNo ratings yet

- Chapter One Project 5 PagesDocument5 pagesChapter One Project 5 PagesHIMANI PALAKSHANo ratings yet

- Corn Disease InfographicDocument1 pageCorn Disease InfographicbioseedNo ratings yet

- PSY1002 Psychological Disorders Sem2 2010-2011Document6 pagesPSY1002 Psychological Disorders Sem2 2010-2011dj_indy1No ratings yet

- Total LaryngectomyDocument15 pagesTotal LaryngectomyDenny Rizaldi AriantoNo ratings yet

- Mapeh First Quarter Notes: Foundation Pillars of Reproductive Health RH LAW 10354Document12 pagesMapeh First Quarter Notes: Foundation Pillars of Reproductive Health RH LAW 10354Frigid GreenNo ratings yet