Professional Documents

Culture Documents

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

Uploaded by

Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- FitazFK - FitazFK in 8 Weeks PDFDocument93 pagesFitazFK - FitazFK in 8 Weeks PDFcharice styles100% (1)

- Turn Up The Heat - Unlock The Fat-Burning Power of Your MetabolismDocument378 pagesTurn Up The Heat - Unlock The Fat-Burning Power of Your MetabolismElvis Florentino96% (24)

- Ketogenic Diet For Type 2 Diabetes: Dr. Sarah Hallberg DO, MSDocument95 pagesKetogenic Diet For Type 2 Diabetes: Dr. Sarah Hallberg DO, MSRadwan AjoNo ratings yet

- 1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainDocument7 pages1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG0% (1)

- 101 - Ways PDF Yuri ElkainDocument208 pages101 - Ways PDF Yuri ElkainStudentMadHouse100% (4)

- Ben and Jerry Situation Analysis 1Document30 pagesBen and Jerry Situation Analysis 1api-238369021100% (1)

- Cooking From The HeartDocument49 pagesCooking From The Heartllow100% (2)

- Meta AnalysisDocument7 pagesMeta AnalysisAliyahRajutButikNo ratings yet

- 10 FullDocument9 pages10 Fullraksneck23No ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of A Low-Carbohydrate Diet For Obesity - NEJMDocument16 pagesA Randomized Trial of A Low-Carbohydrate Diet For Obesity - NEJMMateo PeychauxNo ratings yet

- Neuhouser 2011Document6 pagesNeuhouser 2011Luii GomezNo ratings yet

- Low-Fat Vs Low-CarbDocument8 pagesLow-Fat Vs Low-CarbTrismegisteNo ratings yet

- Glucemic IndexDocument52 pagesGlucemic IndexMayra de CáceresNo ratings yet

- DC 0803002466Document3 pagesDC 0803002466J moralesNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index LoadDocument52 pagesGlycemic Index Loadchennai1stNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Low Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Foods As Panacea For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Prospects, Challenges and SolutionsDocument12 pagesThe Concept of Low Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Foods As Panacea For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Prospects, Challenges and SolutionsEva NoviantiNo ratings yet

- Esfahani Et al-2011-IUBMB Life PDFDocument7 pagesEsfahani Et al-2011-IUBMB Life PDFLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- 10 3390@nu12072005Document19 pages10 3390@nu12072005Maria Isabel LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Review Open Access: Lukas Schwingshackl, Lisa Patricia Hobl and Georg HoffmannDocument10 pagesReview Open Access: Lukas Schwingshackl, Lisa Patricia Hobl and Georg HoffmannLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Glycaemic Control Among Qatari Adults With Type 2 DiabetesDocument8 pagesDietary Patterns and Glycaemic Control Among Qatari Adults With Type 2 DiabetesHarol NegreteNo ratings yet

- Low Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Diets in Adults With Excess Weight: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Randomised Clinical TrialsDocument12 pagesLow Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Diets in Adults With Excess Weight: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Randomised Clinical TrialsLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Glycaemic Index of Various Staple Carbohydrate-Rich Foods in The UK DietDocument15 pagesDetermination of The Glycaemic Index of Various Staple Carbohydrate-Rich Foods in The UK DietJia Jun VooNo ratings yet

- Glikemik Indeks Pada DMDocument6 pagesGlikemik Indeks Pada DMAliyahRajutButikNo ratings yet

- Final 4Document11 pagesFinal 4api-722911357No ratings yet

- The Effects of A Low Glycemic Load Diet On Weight Loss and Key Health Risk IndicatorsDocument8 pagesThe Effects of A Low Glycemic Load Diet On Weight Loss and Key Health Risk IndicatorsAnonymous G6zDTD2yNo ratings yet

- Review of LituratureDocument12 pagesReview of Lituraturealive computerNo ratings yet

- Wiliam Yancy PDFDocument7 pagesWiliam Yancy PDFDeaz Fazzaura PutriNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 11 00586Document12 pagesNutrients 11 00586Meisya Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 Nutritional Assessment AssignmentDocument7 pagesUnit 9 Nutritional Assessment Assignmentoliviachappell13No ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan For Weight LossDocument8 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan For Weight Losszainab asalNo ratings yet

- Dietary Strategies For Patients With TypDocument8 pagesDietary Strategies For Patients With TypMalal QuechuaNo ratings yet

- Glycemic IndexDocument30 pagesGlycemic IndexLovina Falendini Andri100% (1)

- The Zone Diet: An Anti-Inflammatory, Low Glycemic-Load Diet: ReviewDocument15 pagesThe Zone Diet: An Anti-Inflammatory, Low Glycemic-Load Diet: ReviewHigor Henriques100% (1)

- Carbohydrates Research-5Document8 pagesCarbohydrates Research-5api-466416222No ratings yet

- The Effect of High-Protein, Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesThe Effect of High-Protein, Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialFirda Rizky KhoerunnissaNo ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededDocument6 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededConciencia CristalinaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: A Scientific Perspective of Personalised Gene-Based Dietary Recommendations For Weight ManagementDocument14 pagesNutrients: A Scientific Perspective of Personalised Gene-Based Dietary Recommendations For Weight ManagementMeisya Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index by Mwesige Ronald 19.U.0286Document8 pagesGlycemic Index by Mwesige Ronald 19.U.0286mwesige ronaldNo ratings yet

- A Battle Royale To Determine The Best Diet For Type 1 DiabetesDocument3 pagesA Battle Royale To Determine The Best Diet For Type 1 DiabetesIvan KulevNo ratings yet

- Dietary Fiber Intake and Glycemic Control: Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) StudyDocument8 pagesDietary Fiber Intake and Glycemic Control: Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) StudyLeonardo AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates - The Good, The Bad and The Wholegrain: Review ArticleDocument4 pagesCarbohydrates - The Good, The Bad and The Wholegrain: Review ArticleimeldafitriNo ratings yet

- Nfs 774 Case StudyDocument37 pagesNfs 774 Case Studyapi-533845626No ratings yet

- ASs 2 OriginalDocument13 pagesASs 2 OriginalArushi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Effect of A High-Protein Diet On Maintenance of Blood Pressure Levels Achieved After Initial Weight Loss: The Diogenes Randomized StudyDocument6 pagesEffect of A High-Protein Diet On Maintenance of Blood Pressure Levels Achieved After Initial Weight Loss: The Diogenes Randomized StudyDevi C'chabii ChabiiNo ratings yet

- Health Benefits of Barley PDFDocument4 pagesHealth Benefits of Barley PDFYusrinaNoorAzizahNo ratings yet

- Scientific Research On Basic DietDocument3 pagesScientific Research On Basic DietJacob del CeniaNo ratings yet

- Human Nutrition and MetabolismDocument7 pagesHuman Nutrition and MetabolismMisyani MisyaniNo ratings yet

- Effects of Wholegrain Compared To Refined Grain Intake On Cardiometabolic Risk Markers, Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children - A  Randomized Crossover TrialDocument11 pagesEffects of Wholegrain Compared To Refined Grain Intake On Cardiometabolic Risk Markers, Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children - A  Randomized Crossover TrialFransiska FranshuidNo ratings yet

- Barley ConwayarticleDocument8 pagesBarley ConwayarticleNur Hafizah Bee BitNo ratings yet

- Pistachio Nut Consumption and Serum Lipid Levels: Original ResearchDocument8 pagesPistachio Nut Consumption and Serum Lipid Levels: Original ResearchMônica BatalhaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFDocument18 pagesImpact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFUdien Jmc Tíga TìgaNo ratings yet

- Dairy Products and Metabolic SyndromeDocument4 pagesDairy Products and Metabolic SyndromeIsabella KyrillosNo ratings yet

- Melaniew PRP GdmpowerpointDocument38 pagesMelaniew PRP Gdmpowerpointapi-287717817No ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededDocument6 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededCem Tunaboylu (Student)No ratings yet

- Tabela IGDocument52 pagesTabela IGagata.lewickaaNo ratings yet

- Associations of Dietary Diversity Score, Obesity, and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein With Hba1CDocument8 pagesAssociations of Dietary Diversity Score, Obesity, and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein With Hba1Cokky assetyaNo ratings yet

- Viewarticle 899842 PrintDocument2 pagesViewarticle 899842 Printmuhammad rizkyNo ratings yet

- DASH Eating Plan: An Eating Pattern For Diabetes Management: From Research To PracticeDocument6 pagesDASH Eating Plan: An Eating Pattern For Diabetes Management: From Research To PracticeSari SaryonoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Diets Enriched in Almonds On Insulin Action and Serum Lipids in Adults With Normal Glucose Tolerance or Type 2 DiabetesDocument7 pagesEffect of Diets Enriched in Almonds On Insulin Action and Serum Lipids in Adults With Normal Glucose Tolerance or Type 2 DiabetesLyly SelenaNo ratings yet

- Should Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Be Considered in Dietary RecommendationsDocument22 pagesShould Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Be Considered in Dietary RecommendationsLilo LiliNo ratings yet

- 3 Dietary Carbohydrates in Type 2 DM and Metabolic DiseasesDocument8 pages3 Dietary Carbohydrates in Type 2 DM and Metabolic DiseasesFanny AgustiaWandanyNo ratings yet

- Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review From Clinicians Using The Approach in PracticeDocument18 pagesLow-Carbohydrate Diets in The Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review From Clinicians Using The Approach in PracticeAakash KoulNo ratings yet

- Diets Among Obese IndividualsDocument26 pagesDiets Among Obese IndividualsjuanpabloefNo ratings yet

- JCM 08 01645 PDFDocument11 pagesJCM 08 01645 PDFFranklin Howley-Dumit SerulleNo ratings yet

- Chester Et Al-2019-Diabetes Metabolism Research and ReviewsDocument10 pagesChester Et Al-2019-Diabetes Metabolism Research and ReviewsCem Tunaboylu (Student)No ratings yet

- Wet Mount Proficiency 2007A CritiqueDocument6 pagesWet Mount Proficiency 2007A CritiqueAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Wet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Document4 pagesWet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- King & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFDocument14 pagesKing & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Kennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeDocument16 pagesKennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Erwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Document7 pagesErwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- A Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceDocument8 pagesA Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG100% (1)

- National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationDocument12 pagesNational Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- LOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFDocument1 pageLOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- 2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesDocument28 pages2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- JNC8 HTNDocument2 pagesJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Clinical Pearl TalkDocument26 pagesClinical Pearl TalkAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Statin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideDocument6 pagesStatin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Nonhospital SettingDocument17 pagesNonhospital SettingAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- 1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutDocument34 pages1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Commonly Prescribed Insulin ProductsDocument1 pageCommonly Prescribed Insulin ProductsAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Finding The BalanceDocument8 pagesFinding The BalanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Kidney TransplantDocument6 pagesKidney TransplantAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG100% (1)

- Break Thru Nutrition PlanDocument26 pagesBreak Thru Nutrition PlanharbansalNo ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet - A Detailed Beginner's Guide To KetoDocument19 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet - A Detailed Beginner's Guide To Ketoradhika1992No ratings yet

- Hot Cocoa Bombs Cookbook - 150+ Delicious Hot Chocolate Recipes (2022)Document91 pagesHot Cocoa Bombs Cookbook - 150+ Delicious Hot Chocolate Recipes (2022)Gary TanNo ratings yet

- Physical Education: Quarter 4 - Module 4b: Other Dance FormsDocument20 pagesPhysical Education: Quarter 4 - Module 4b: Other Dance FormsJulius BayagaNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 - V1Document27 pagesUnit 7 - V1spmajishNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in ElderlyDocument55 pagesNutrition in ElderlyAccessoires Belle100% (1)

- 24-Hour Perinatal Dietary RecallDocument10 pages24-Hour Perinatal Dietary RecallAndromeda_19No ratings yet

- Recommended Dietary AllowanceDocument5 pagesRecommended Dietary AllowanceManuel KevogoNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda Book PDFDocument147 pagesAyurveda Book PDFradhaNo ratings yet

- The Beginner's Guide To Intermittent Fasting - and The Fascinating Science Behind This Hip Biohacking ToolDocument18 pagesThe Beginner's Guide To Intermittent Fasting - and The Fascinating Science Behind This Hip Biohacking ToolWilson GayoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in Exercise and SportsDocument3 pagesNutrition in Exercise and SportsMicah YapNo ratings yet

- Purpose Tone Point of View Intended Audience: ELC 501 Blended Learning Lesson Week 10Document31 pagesPurpose Tone Point of View Intended Audience: ELC 501 Blended Learning Lesson Week 10Nat zoldNo ratings yet

- Calories in Indian Food - Indian Food Calories - Calorie Chart of Indian FoodDocument2 pagesCalories in Indian Food - Indian Food Calories - Calorie Chart of Indian Foodvenkateshbabu2004No ratings yet

- Unadm Open and Distance University of Mexico UnadmDocument7 pagesUnadm Open and Distance University of Mexico UnadmLucy BritoNo ratings yet

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) - Symptoms, Causes, and TreatmentDocument19 pagesPolycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) - Symptoms, Causes, and TreatmentAkshay HarekarNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS Genap - Bing Wajib - Xi - 2023Document8 pagesSoal PTS Genap - Bing Wajib - Xi - 2023Nopi PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Smoothies For Weight Loss Health and Beauty by Holly JohnsonDocument151 pagesSmoothies For Weight Loss Health and Beauty by Holly JohnsonEnrique ArocaNo ratings yet

- Obesity and Mental HealthDocument28 pagesObesity and Mental HealthHv EstokNo ratings yet

- 50 Foods To Avoid To Lose Weigh - Malik Johnson PDFDocument391 pages50 Foods To Avoid To Lose Weigh - Malik Johnson PDFtotherethymNo ratings yet

- Irony Worksheet 2Document3 pagesIrony Worksheet 2TENZIN THINLAY0% (1)

- Exercise Physiology Theory and Application To Fitness and Performance Eleventh Edition Scott K Powers Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument70 pagesExercise Physiology Theory and Application To Fitness and Performance Eleventh Edition Scott K Powers Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFmary.leach681100% (14)

- Why Rice Is Not Good For You by Dr. ET Rasco JRDocument72 pagesWhy Rice Is Not Good For You by Dr. ET Rasco JRCyrose Silvosa MilladoNo ratings yet

- Dietary Intake, Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure of Malaysian AdolescentsDocument8 pagesDietary Intake, Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure of Malaysian Adolescentsdila_712No ratings yet

- GED Practice 1Document3 pagesGED Practice 1FREEZE YGNo ratings yet

- Month End WorksheetDocument5 pagesMonth End WorksheetMihaela RussellNo ratings yet

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

Uploaded by

Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

U G I D M: Sing The Lycemic Ndex IN Iabetes Anagement

Uploaded by

Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGCopyright:

Available Formats

By Nora Saul, MS, RD, and Melinda D.

Maryniuk, MEd, RD, CDE

USING THE GLYCEMIC INDEX

IN DIABETES MANAGEMENT

Consider carbohydrate quality to achieve blood glucose control.

lthough nutritional management is well

recognized as the cornerstone of diabetes treatment, theres no consensus on

the type of diet or the nutrient composition thats most effective for glycemic

control.1-5 Until recently, most American health care

providers have focused on keeping carbohydrate intake consistent while downplaying the influence of

carbohydrate quality. Exactly how different types of

carbohydrate foods affect blood glucose and whether

the differences are clinically significant have been the

subjects of much debate. This article summarizes

the findings of a recent Cochrane Collaboration review of the efficacy of using the glycemic index (GI)

to modulate blood glucose response.6

The term glycemic index refers to the relative ranking of different carbohydrate foods according to

how they affect the blood glucose level.7 To determine a foods GI, its effect on blood glucose levels

in healthy volunteers is compared with that of 50 g

of glucose. First healthy volunteers ingest a portion

of the food containing 50 g of digestible carbohydrate. Blood glucose levels are measured every half

hour for two hours and a glucose response curve is

calculated. The GI of the food is calculated by dividing the area under the curve for the food by that for

glucose, which is valued at 100. A foods GI is then

ranked as high (70 or more), medium (56 to 69), or

low (55 or less). Carbohydrates with high GI values

cause blood glucose levels to rise more quickly than

those with low GI values. For example, eating a boiled

white potato, which has a GI of 96, raises blood glucose more rapidly than eating a serving of black

beans, which has a GI of 30. However, there can be

variability in GI values within the same food category

depending on where the food was grown, how it was

cooked, and slight differences in the plant itself. In general, foods that have higher fiber or fat content have

lower GI values, but this doesnt always apply. A baked

potato with skin is a good fiber source, yet it doesnt

have a low GI.

The GI value doesnt take into account the amount

of carbohydrate in different standard food portions.

68

AJN July 2010

Vol. 110, No. 7

This can lead to confusion about the relative effects

of certain foods on glycemic control. For example,

the University of Sydneys online GI database (available at www.glycemicindex.com) reports that although watermelon has a GI of 72, a standard portion

contains very little carbohydrate and therefore doesnt

significantly raise blood glucose levels. To resolve this

discrepancy, researchers developed a secondary measure called the glycemic load (GL). Its calculated by

multiplying a foods GI by the number of grams of

carbohydrate present in a standard portion and dividing that by 100. A GL of 20 or more is high, 11 to 19

is medium, and 10 or less is low. For example, the GL

of watermelon, which has 6 g of carbohydrate in a

120 g portion, is calculated as:

72 6 / 100 = 4.3

This is then rounded to a GL of 4. Table 17 presents

the GIs and GLs of a variety of foods.

The most recent recommendations on nutrition

released by the American Diabetes Association

(ADA)8 state, The use of glycemic index and load

may provide a modest additional benefit [for glycemic control] over that observed when total carbohydrate is considered alone. The ADA considers

the evidence for this to be supportive rather than

clear, indicating that additional research in this area

is needed.

The Cochrane Collaboration review looked at 10

randomized controlled studies comparing low GI

with high GI diets. An 11th study compared a low

GI diet with a measured carbohydrate exchange program. The trials varied in length from four weeks to

one year.6 The primary end point in studies of longer

than six weeks was glycemic control as measured by

glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c). In studies of less

than six weeks in length, glycemic control as measured by fructosamine level (which measures changes

in blood glucose control over a two-to-three-week

period) or glycated serum albumin level (a measure

of the binding of the glucose molecule to serum albumin) was the primary end point. The review included

402 participants between the ages of 10 and 63 with

ajnonline.com

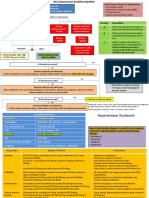

Table 1. Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load of Selected Carbohydrate Foods7

Glycemic Index

Glycemic Load

Low (55 or less)

Medium (5669)

Low (10 or less)

Whole wheat bread, rye bread, sourdough

bread, Kelloggs All-Bran cereal, green

peas, kidney beans, apple, grapefruit,

strawberries

Vanilla yogurt, cantaloupe,

French bread, whole wheat

pita

White bread, watermelon

Medium (1119)

Oatmeal, banana, chickpeas

Shredded wheat cereal,

sweet corn

Boiled red potato, bran flakes

High (20 or more)

Pasta (white flour)

Bagel, raisins, brown rice

Boiled white potato, white rice

either type 1 or type 2 diabetes. Six studies including 247 participants reported HbA1c values. Among

these participants, HbA1c decreased by 0.5% (95%

confidence interval of 0.8 0.2)a significant effect comparable to that produced by the less potent

oral antihyperglycemic agents. The studies reviewing

fructosamine and glycated serum albumin also attributed positive results to low glycemic diets. The study

that compared a low GI diet to a measured carbohydrate exchange diet didnt report statistical differences; however, compared to the exchange group,

twice the percentage of participants in the low GI

group reached acceptable HbA1c levels.

Since none of the studies reported the total carbohydrate content of the diets or whether this parameter

was controlled for, its difficult to analyze their outcomes. In addition, each of the studies defined high

and low GI diets differently and sometimes ones low

GI value was anothers high value and vice versa

although there was a significant difference between the

high and low GI values within each study.

Many factors affect a foods glycemic effect: its soluble fiber content, the type of starch it contains, its fat

and protein content, its acid content, its physiologic

state (liquid versus solid), the cooking method used,

and the glycemic condition of the person eating it.

The GI focuses on one parameter onlyhow quickly

blood glucose rises in response to a particular food

and provides no guidance in terms of serving size or

nutrient balance, two parameters that many patients

lack the skill to consider when they plan their meals.

The ADA recommends that a registered dietitian play

the primary role in teaching patients about nutrition

care.8 When patients are interested in moving beyond

basic meal planning, a registered dietitian can help

them use the GI to fine-tune their dietary patterns to

improve their metabolic control.

Nora Saul is manager of nutrition services at the Joslin

Diabetes Center in Boston, where Melinda D. Maryniuk is

director of clinical education programs in strategic initiatives.

Contact author: Nora Saul, nora.saul@joslin.harvard.edu.

ajn@wolterskluwer.com

High (70 or more)

PATIENT RESOURCES

Brand-Miller J, et al. The New Glucose Revolution: Low GI

Eating Made Easy. New York: Marlowe; 2005.

Brand-Miller J, Foster-Powell K. The New Glucose Revolution

Shoppers Guide to GI Values 2009. Cambridge, MA: Da

Capo Press; 2008.

Brand-Miller J, et al. Low GI Diet Cookbook: 100 Simple,

Delicious Smart-Carb Recipes. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo

Press; 2005.

Brand-Miller J, et al. The New Glucose Revolution: The

Authoritative Guide to the Glycemic IndexThe Dietary

Solution for Lifelong Health. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press;

2006.

Harvard School of Public Health. The Nutrition Source:

carbohydrates: the bottom line. http://bit.ly/11YpSq.

REFERENCES

1. Gerhard GT, et al. Effects of a low-fat diet compared with

those of a high-monounsaturated fat diet on body weight,

plasma lipids and lipoproteins, and glycemic control in type 2

diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80(3):668-73.

2. Esposito K, et al. Effects of a Mediterranean-style diet on

the need for antihyperglycemic drug therapy in patients with

newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann

Intern Med 2009;151(5):306-14.

3. Kodama S, et al. Influence of fat and carbohydrate proportions on the metabolic profile in patients with type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2009;32(5):959-65.

4. Parker B, et al. Effect of a high-protein, high-monounsaturated fat weight loss diet on glycemic control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25(3):425-30.

5. Brehm BJ, et al. One-year comparison of a highmonounsaturated fat diet with a high-carbohydrate diet in

type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2009;32(2):215-20.

6. Thomas D, Elliott EJ. Low glycaemic index, or low glycaemic load, diets for diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database

Syst Rev 2009(1):CD006296.

7. Atkinson FS, et al. International tables of glycemic index

and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care 2008;

31(12):2281-3.

8. Bantle JP, et al. Nutrition recommendations and interventions for diabetes: a position statement of the American

Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2008;31 Suppl 1:

S61-S78.

AJN July 2010

Vol. 110, No. 7

69

You might also like

- FitazFK - FitazFK in 8 Weeks PDFDocument93 pagesFitazFK - FitazFK in 8 Weeks PDFcharice styles100% (1)

- Turn Up The Heat - Unlock The Fat-Burning Power of Your MetabolismDocument378 pagesTurn Up The Heat - Unlock The Fat-Burning Power of Your MetabolismElvis Florentino96% (24)

- Ketogenic Diet For Type 2 Diabetes: Dr. Sarah Hallberg DO, MSDocument95 pagesKetogenic Diet For Type 2 Diabetes: Dr. Sarah Hallberg DO, MSRadwan AjoNo ratings yet

- 1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainDocument7 pages1990-Fleming Suturing Method and PainAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG0% (1)

- 101 - Ways PDF Yuri ElkainDocument208 pages101 - Ways PDF Yuri ElkainStudentMadHouse100% (4)

- Ben and Jerry Situation Analysis 1Document30 pagesBen and Jerry Situation Analysis 1api-238369021100% (1)

- Cooking From The HeartDocument49 pagesCooking From The Heartllow100% (2)

- Meta AnalysisDocument7 pagesMeta AnalysisAliyahRajutButikNo ratings yet

- 10 FullDocument9 pages10 Fullraksneck23No ratings yet

- A Randomized Trial of A Low-Carbohydrate Diet For Obesity - NEJMDocument16 pagesA Randomized Trial of A Low-Carbohydrate Diet For Obesity - NEJMMateo PeychauxNo ratings yet

- Neuhouser 2011Document6 pagesNeuhouser 2011Luii GomezNo ratings yet

- Low-Fat Vs Low-CarbDocument8 pagesLow-Fat Vs Low-CarbTrismegisteNo ratings yet

- Glucemic IndexDocument52 pagesGlucemic IndexMayra de CáceresNo ratings yet

- DC 0803002466Document3 pagesDC 0803002466J moralesNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index LoadDocument52 pagesGlycemic Index Loadchennai1stNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Low Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Foods As Panacea For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Prospects, Challenges and SolutionsDocument12 pagesThe Concept of Low Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Foods As Panacea For Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Prospects, Challenges and SolutionsEva NoviantiNo ratings yet

- Esfahani Et al-2011-IUBMB Life PDFDocument7 pagesEsfahani Et al-2011-IUBMB Life PDFLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- 10 3390@nu12072005Document19 pages10 3390@nu12072005Maria Isabel LondoñoNo ratings yet

- Review Open Access: Lukas Schwingshackl, Lisa Patricia Hobl and Georg HoffmannDocument10 pagesReview Open Access: Lukas Schwingshackl, Lisa Patricia Hobl and Georg HoffmannLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Dietary Patterns and Glycaemic Control Among Qatari Adults With Type 2 DiabetesDocument8 pagesDietary Patterns and Glycaemic Control Among Qatari Adults With Type 2 DiabetesHarol NegreteNo ratings yet

- Low Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Diets in Adults With Excess Weight: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Randomised Clinical TrialsDocument12 pagesLow Glycaemic Index and Glycaemic Load Diets in Adults With Excess Weight: Systematic Review and Meta Analysis of Randomised Clinical TrialsLisiane PerinNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Glycaemic Index of Various Staple Carbohydrate-Rich Foods in The UK DietDocument15 pagesDetermination of The Glycaemic Index of Various Staple Carbohydrate-Rich Foods in The UK DietJia Jun VooNo ratings yet

- Glikemik Indeks Pada DMDocument6 pagesGlikemik Indeks Pada DMAliyahRajutButikNo ratings yet

- Final 4Document11 pagesFinal 4api-722911357No ratings yet

- The Effects of A Low Glycemic Load Diet On Weight Loss and Key Health Risk IndicatorsDocument8 pagesThe Effects of A Low Glycemic Load Diet On Weight Loss and Key Health Risk IndicatorsAnonymous G6zDTD2yNo ratings yet

- Review of LituratureDocument12 pagesReview of Lituraturealive computerNo ratings yet

- Wiliam Yancy PDFDocument7 pagesWiliam Yancy PDFDeaz Fazzaura PutriNo ratings yet

- Nutrients 11 00586Document12 pagesNutrients 11 00586Meisya Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- Unit 9 Nutritional Assessment AssignmentDocument7 pagesUnit 9 Nutritional Assessment Assignmentoliviachappell13No ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan For Weight LossDocument8 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of The Medifast 5 & 1 Plan For Weight Losszainab asalNo ratings yet

- Dietary Strategies For Patients With TypDocument8 pagesDietary Strategies For Patients With TypMalal QuechuaNo ratings yet

- Glycemic IndexDocument30 pagesGlycemic IndexLovina Falendini Andri100% (1)

- The Zone Diet: An Anti-Inflammatory, Low Glycemic-Load Diet: ReviewDocument15 pagesThe Zone Diet: An Anti-Inflammatory, Low Glycemic-Load Diet: ReviewHigor Henriques100% (1)

- Carbohydrates Research-5Document8 pagesCarbohydrates Research-5api-466416222No ratings yet

- The Effect of High-Protein, Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialDocument10 pagesThe Effect of High-Protein, Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes: A 12 Month Randomised Controlled TrialFirda Rizky KhoerunnissaNo ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededDocument6 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededConciencia CristalinaNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: A Scientific Perspective of Personalised Gene-Based Dietary Recommendations For Weight ManagementDocument14 pagesNutrients: A Scientific Perspective of Personalised Gene-Based Dietary Recommendations For Weight ManagementMeisya Nur'ainiNo ratings yet

- Glycemic Index by Mwesige Ronald 19.U.0286Document8 pagesGlycemic Index by Mwesige Ronald 19.U.0286mwesige ronaldNo ratings yet

- A Battle Royale To Determine The Best Diet For Type 1 DiabetesDocument3 pagesA Battle Royale To Determine The Best Diet For Type 1 DiabetesIvan KulevNo ratings yet

- Dietary Fiber Intake and Glycemic Control: Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) StudyDocument8 pagesDietary Fiber Intake and Glycemic Control: Coronary Artery Calcification in Type 1 Diabetes (CACTI) StudyLeonardo AzevedoNo ratings yet

- Carbohydrates - The Good, The Bad and The Wholegrain: Review ArticleDocument4 pagesCarbohydrates - The Good, The Bad and The Wholegrain: Review ArticleimeldafitriNo ratings yet

- Nfs 774 Case StudyDocument37 pagesNfs 774 Case Studyapi-533845626No ratings yet

- ASs 2 OriginalDocument13 pagesASs 2 OriginalArushi GuptaNo ratings yet

- Effect of A High-Protein Diet On Maintenance of Blood Pressure Levels Achieved After Initial Weight Loss: The Diogenes Randomized StudyDocument6 pagesEffect of A High-Protein Diet On Maintenance of Blood Pressure Levels Achieved After Initial Weight Loss: The Diogenes Randomized StudyDevi C'chabii ChabiiNo ratings yet

- Health Benefits of Barley PDFDocument4 pagesHealth Benefits of Barley PDFYusrinaNoorAzizahNo ratings yet

- Scientific Research On Basic DietDocument3 pagesScientific Research On Basic DietJacob del CeniaNo ratings yet

- Human Nutrition and MetabolismDocument7 pagesHuman Nutrition and MetabolismMisyani MisyaniNo ratings yet

- Effects of Wholegrain Compared To Refined Grain Intake On Cardiometabolic Risk Markers, Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children - A  Randomized Crossover TrialDocument11 pagesEffects of Wholegrain Compared To Refined Grain Intake On Cardiometabolic Risk Markers, Gut Microbiota and Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Children - A  Randomized Crossover TrialFransiska FranshuidNo ratings yet

- Barley ConwayarticleDocument8 pagesBarley ConwayarticleNur Hafizah Bee BitNo ratings yet

- Pistachio Nut Consumption and Serum Lipid Levels: Original ResearchDocument8 pagesPistachio Nut Consumption and Serum Lipid Levels: Original ResearchMônica BatalhaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFDocument18 pagesImpact of Dietary Macronutrient Distribu PDFUdien Jmc Tíga TìgaNo ratings yet

- Dairy Products and Metabolic SyndromeDocument4 pagesDairy Products and Metabolic SyndromeIsabella KyrillosNo ratings yet

- Melaniew PRP GdmpowerpointDocument38 pagesMelaniew PRP Gdmpowerpointapi-287717817No ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededDocument6 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet: Evidence For Optimism But High-Quality Research NeededCem Tunaboylu (Student)No ratings yet

- Tabela IGDocument52 pagesTabela IGagata.lewickaaNo ratings yet

- Associations of Dietary Diversity Score, Obesity, and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein With Hba1CDocument8 pagesAssociations of Dietary Diversity Score, Obesity, and High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein With Hba1Cokky assetyaNo ratings yet

- Viewarticle 899842 PrintDocument2 pagesViewarticle 899842 Printmuhammad rizkyNo ratings yet

- DASH Eating Plan: An Eating Pattern For Diabetes Management: From Research To PracticeDocument6 pagesDASH Eating Plan: An Eating Pattern For Diabetes Management: From Research To PracticeSari SaryonoNo ratings yet

- Effect of Diets Enriched in Almonds On Insulin Action and Serum Lipids in Adults With Normal Glucose Tolerance or Type 2 DiabetesDocument7 pagesEffect of Diets Enriched in Almonds On Insulin Action and Serum Lipids in Adults With Normal Glucose Tolerance or Type 2 DiabetesLyly SelenaNo ratings yet

- Should Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Be Considered in Dietary RecommendationsDocument22 pagesShould Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Be Considered in Dietary RecommendationsLilo LiliNo ratings yet

- 3 Dietary Carbohydrates in Type 2 DM and Metabolic DiseasesDocument8 pages3 Dietary Carbohydrates in Type 2 DM and Metabolic DiseasesFanny AgustiaWandanyNo ratings yet

- Low-Carbohydrate Diets in The Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review From Clinicians Using The Approach in PracticeDocument18 pagesLow-Carbohydrate Diets in The Management of Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes: A Review From Clinicians Using The Approach in PracticeAakash KoulNo ratings yet

- Diets Among Obese IndividualsDocument26 pagesDiets Among Obese IndividualsjuanpabloefNo ratings yet

- JCM 08 01645 PDFDocument11 pagesJCM 08 01645 PDFFranklin Howley-Dumit SerulleNo ratings yet

- Chester Et Al-2019-Diabetes Metabolism Research and ReviewsDocument10 pagesChester Et Al-2019-Diabetes Metabolism Research and ReviewsCem Tunaboylu (Student)No ratings yet

- Wet Mount Proficiency 2007A CritiqueDocument6 pagesWet Mount Proficiency 2007A CritiqueAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Wet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Document4 pagesWet Mount Proficiency 2008A Critique2Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- King & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFDocument14 pagesKing & Pinger, Pearls of Midwifery PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Kennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeDocument16 pagesKennedy-Model of Exemplary Midwifery PracticeAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Erwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Document7 pagesErwin-Demystifying The Nurse-Midwifery MGMT Process 1987Anonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- A Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceDocument8 pagesA Healthy Menopause: Diet, Nutrition and Lifestyle GuidanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG100% (1)

- National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationDocument12 pagesNational Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011: Diabetes Affects 25.8 Million People 8.3% of The U.S. PopulationAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- LOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFDocument1 pageLOC Certificate For 'Assessing COPD in Primary Care - 0.5 Credit PDFAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- 2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesDocument28 pages2017 JNC 8 Lipid and HTN GuidelinesAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- JNC8 HTNDocument2 pagesJNC8 HTNTaradifaNurInsi0% (1)

- Clinical Pearl TalkDocument26 pagesClinical Pearl TalkAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Statin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideDocument6 pagesStatin Drug Interaction Pocket GuideAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Nonhospital SettingDocument17 pagesNonhospital SettingAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- 1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutDocument34 pages1APHA2012HVNAslide2012 10 23handoutAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Commonly Prescribed Insulin ProductsDocument1 pageCommonly Prescribed Insulin ProductsAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Finding The BalanceDocument8 pagesFinding The BalanceAnonymous bq4KY0mcWGNo ratings yet

- Kidney TransplantDocument6 pagesKidney TransplantAnonymous bq4KY0mcWG100% (1)

- Break Thru Nutrition PlanDocument26 pagesBreak Thru Nutrition PlanharbansalNo ratings yet

- The Ketogenic Diet - A Detailed Beginner's Guide To KetoDocument19 pagesThe Ketogenic Diet - A Detailed Beginner's Guide To Ketoradhika1992No ratings yet

- Hot Cocoa Bombs Cookbook - 150+ Delicious Hot Chocolate Recipes (2022)Document91 pagesHot Cocoa Bombs Cookbook - 150+ Delicious Hot Chocolate Recipes (2022)Gary TanNo ratings yet

- Physical Education: Quarter 4 - Module 4b: Other Dance FormsDocument20 pagesPhysical Education: Quarter 4 - Module 4b: Other Dance FormsJulius BayagaNo ratings yet

- Unit 7 - V1Document27 pagesUnit 7 - V1spmajishNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in ElderlyDocument55 pagesNutrition in ElderlyAccessoires Belle100% (1)

- 24-Hour Perinatal Dietary RecallDocument10 pages24-Hour Perinatal Dietary RecallAndromeda_19No ratings yet

- Recommended Dietary AllowanceDocument5 pagesRecommended Dietary AllowanceManuel KevogoNo ratings yet

- Ayurveda Book PDFDocument147 pagesAyurveda Book PDFradhaNo ratings yet

- The Beginner's Guide To Intermittent Fasting - and The Fascinating Science Behind This Hip Biohacking ToolDocument18 pagesThe Beginner's Guide To Intermittent Fasting - and The Fascinating Science Behind This Hip Biohacking ToolWilson GayoNo ratings yet

- Nutrition in Exercise and SportsDocument3 pagesNutrition in Exercise and SportsMicah YapNo ratings yet

- Purpose Tone Point of View Intended Audience: ELC 501 Blended Learning Lesson Week 10Document31 pagesPurpose Tone Point of View Intended Audience: ELC 501 Blended Learning Lesson Week 10Nat zoldNo ratings yet

- Calories in Indian Food - Indian Food Calories - Calorie Chart of Indian FoodDocument2 pagesCalories in Indian Food - Indian Food Calories - Calorie Chart of Indian Foodvenkateshbabu2004No ratings yet

- Unadm Open and Distance University of Mexico UnadmDocument7 pagesUnadm Open and Distance University of Mexico UnadmLucy BritoNo ratings yet

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) - Symptoms, Causes, and TreatmentDocument19 pagesPolycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) - Symptoms, Causes, and TreatmentAkshay HarekarNo ratings yet

- Soal PTS Genap - Bing Wajib - Xi - 2023Document8 pagesSoal PTS Genap - Bing Wajib - Xi - 2023Nopi PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Smoothies For Weight Loss Health and Beauty by Holly JohnsonDocument151 pagesSmoothies For Weight Loss Health and Beauty by Holly JohnsonEnrique ArocaNo ratings yet

- Obesity and Mental HealthDocument28 pagesObesity and Mental HealthHv EstokNo ratings yet

- 50 Foods To Avoid To Lose Weigh - Malik Johnson PDFDocument391 pages50 Foods To Avoid To Lose Weigh - Malik Johnson PDFtotherethymNo ratings yet

- Irony Worksheet 2Document3 pagesIrony Worksheet 2TENZIN THINLAY0% (1)

- Exercise Physiology Theory and Application To Fitness and Performance Eleventh Edition Scott K Powers Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFDocument70 pagesExercise Physiology Theory and Application To Fitness and Performance Eleventh Edition Scott K Powers Online Ebook Texxtbook Full Chapter PDFmary.leach681100% (14)

- Why Rice Is Not Good For You by Dr. ET Rasco JRDocument72 pagesWhy Rice Is Not Good For You by Dr. ET Rasco JRCyrose Silvosa MilladoNo ratings yet

- Dietary Intake, Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure of Malaysian AdolescentsDocument8 pagesDietary Intake, Physical Activity and Energy Expenditure of Malaysian Adolescentsdila_712No ratings yet

- GED Practice 1Document3 pagesGED Practice 1FREEZE YGNo ratings yet

- Month End WorksheetDocument5 pagesMonth End WorksheetMihaela RussellNo ratings yet