Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hands On: Pgals

Hands On: Pgals

Uploaded by

Awatef AbushhiwaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hands On: Pgals

Hands On: Pgals

Uploaded by

Awatef AbushhiwaCopyright:

Available Formats

REPORTS

ON

THE

RHEUMATIC

DISEASES

SERIES

Hands On

Practical advice on management of rheumatic disease

pGALS A SCREENING EXAMINATION OF THE MUSCULO-

SKELETAL SYSTEM IN SCHOOL-AGED CHILDREN

Helen E Foster, MD, MBBS(Hons), FRCP, FRCPCH, CertMedEd, Professor in Paediatric Rheumatology

Sharmila Jandial, MBChB, MRCPCH, CertMedEd, arc Educational Research Fellow

Musculoskeletal Research Group, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne

Why do primary care doctors need

to know about musculoskeletal

assessment in children?

Children with musculoskeletal (MSK) problems are common

and often present initially to primary care where GPs

have an important role as gatekeepers to secondary care

and specialist services. The majority of causes of MSK

presentations in childhood are benign, self-limiting and

often trauma-related; referral is not always necessary, and

in many instances reassurance alone may suffice. However,

MSK symptoms can be presenting features of potentially lifethreatening conditions such as malignancy, sepsis, vasculitis

and non-accidental injury, and furthermore are commonly

associated features of many chronic paediatric conditions

such as inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, arthritis

and psoriasis. Clinical assessment skills (history-taking and

physical examination), knowledge of normal development,

and clinical presentations at different ages, along with

knowledge of indicators to warrant referral, are important

and facilitate appropriate decision-making in the primary

care setting. This article focuses on pGALS (paediatric Gait,

Arms, Legs, Spine), which is a simple screening approach

to MSK examination in school-aged children and may be

successfully performed in younger ambulant children

the approach to the examination of the toddler and baby

requires a different approach and is not described here.

How is musculoskeletal assessment

of children different to that of

adults?

It is stating the obvious that children are not small adults

in many ways, and here we focus on MSK history-taking

June 2008 No 15

and physical examination. The history is often given by

the parent or carer, may be based on observations and

interpretation of events made by others (such as teachers),

and may be rather vague with non-specific complaints such

as My child is limping or My child is not walking quite

right. Young children may have difficulty in localising or

describing pain in terms that adults may understand. It is not

unusual for young children to deny having pain when asked

directly, and instead present with changes in behaviour (e.g.

irritability or poor sleeping), decreasing ability or interest in

activities and hand skills (e.g. handwriting), or regression of

motor milestones. Some children are shy or frightened and

reluctant to engage in the consultation.

Practical Tip when inflammatory joint disease is

suspected

The lack of reported pain does not exclude arthritis

There is a need to probe for symptoms such as

gelling (e.g. stiffness after long car rides)

altered function (e.g. play, handwriting skills,

regression of motor milestones)

deterioration in behaviour (irritability, poor

sleeping)

There is a need to examine all joints as joint involvement

is often asymptomatic

It is important to probe in the history when there are

indicators of potential inflammatory MSK disease. A delay

in major motor milestones warrants MSK assessment as well

as a global neuro-developmental approach. However, in acquired MSK disease such as juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA)

a history of regression of achieved milestones is often more

significant e.g. the child who was happy to walk unaided

but has recently been reluctant to walk or is now unable to

dress himself without help. In adults the cardinal features

of inflammatory arthritis are pain, stiffness, swelling and

reduced function. However, in children these features may

Medical Editor: Louise Warburton, GP. Production Editor: Frances Mawer (arc). ISSN 1741-833X.

Published 3 times a year by the Arthritis Research Campaign, Copeman House, St Marys Court, St Marys Gate

Chesterfield S41 7TD. Registered Charity No. 207711.

be difficult to elucidate. Joint swelling, limping and reduced

mobility, rather than pain, are the most common presenting

features of JIA.1 The lack of reported pain does not exclude

arthritis the child is undoubtedly in discomfort but, for the

reasons described, may not verbalise this as pain. Swelling is

always significant but can be subtle and easily overlooked,

especially if the changes are symmetrical, and relies on

the examiner being confident in their MSK examination

skills and having an appreciation of what is normal and

abnormal (see below). Rather than describing stiffness, the

parents may notice the child is reluctant to weight-bear or

limps in the mornings or gels after periods of immobility

(e.g. after long car rides or sitting in a classroom). Systemic

upset and the presence of bone rather than joint pain may

be features of MSK disease and are red flags that warrant

urgent referral. More indolent presentations of MSK disease

can also impact on growth (either localised or generalised)

and it is important to assess height and weight and review

growth charts as necessary.

lar, respiratory, gastrointestinal, neurological, skin and eyes,

and, given the broad spectrum of MSK presentations in children, a low threshold for performing pGALS is suggested and

of particular importance in certain clinical scenarios.

Practical Tip when to perform pGALS in the

assessment

How does pGALS differ from adult

GALS?

The sequence of pGALS is essentially the same as adult GALS

with additional manoeuvres to screen the foot and ankle

(walk on heels and then on tiptoes), wrists (palms together

and then hands back to back) and temporomandibular joints

(open mouth and insert three of the childs own fingers),

and with amendments at screening the elbow (reach up

and touch the sky) and neck (look at the ceiling). These additional manoeuvres were included because when adult

GALS was originally tested in school-aged children4 it missed

significant abnormalities at these sites.

RED FLAGS

(Raise concern about infection, malignancy or nonaccidental injury)

Child with muscle, joint or bone pain

Unwell child with pyrexia

Child with limp

Delay or regression of motor milestones

The clumsy child in the absence of neurological

disease

Child with chronic disease and known association with

MSK presentations

Fever, malaise, systemic upset (reduced appetite,

weight loss, sweats)

Bone or joint pain with fever

Refractory or unremitting pain, persistent night-waking

Incongruence between history and presentation (such

as the pattern of the physical findings and a previous

history of neglect)

How to distinguish normal from

abnormal in the musculoskeletal

examination

What is pGALS?

Paediatric GALS (pGALS) is a simple evidence-based approach to an MSK screening assessment in school-aged children, and is based on the adult GALS (Gait, Arms, Legs,

Spine) screen.2 The adult GALS screen is commonly taught

to medical students, and emerging evidence shows an

improvement in doctors confidence and performance

in adult MSK assessment. Educational resources to

support learning of GALS are available.3 pGALS is the only

paediatric MSK screening examination to be validated, and

was originally tested in school-aged children. pGALS has

been demonstrated to have excellent sensitivity to detect

abnormality (i.e. with few false negatives), incorporates

simple manoeuvres often used in clinical practice, and is

quick to do, taking an average of 2 minutes to perform.4

Furthermore, when performed by medical students and

general practitioners pGALS has been shown to have high

sensitivity and is easy to do, with excellent acceptability by

children and their parents (papers in preparation). Younger

children can often perform the screening manoeuvres quite

easily, although validation of pGALS in the pre-school age

group has yet to be demonstrated.

Key to distinguishing normal from abnormal are knowledge

of ranges of movement, looking for asymmetry and

careful examination for subtle changes. In addition, it is

important that GPs are aware of normal variants in gait,

leg alignment and normal motor milestones (Tables 1,2) as

these are a common cause of parental concern, especially

in the pre-school child, and often anxieties can be allayed

with explanation and reassurance. There is considerable

variation in the way normal gait patterns develop; these

may be familial (e.g. bottom-shufflers often walk later) and

subject to racial variation (e.g. African black children tend to

walk sooner and Asian children later than average).

Joint abnormalities can be subtle or difficult to appreciate

in the young (such as chubby ankles, fingers, wrists and

knees). Looking for asymmetrical changes is helpful

although it can be falsely reassuring in the presence of

symmetrical joint involvement. Muscle wasting, such as

of the quadriceps or calf muscles, indicates chronicity of

joint disease and should alert the examiner to knee or

ankle involvement respectively. Swelling of the ankle is

often best judged from behind the child. Ranges of joint

movement should be symmetrical and an appreciation of

the normal range of movement in childhood can be gained

with increased clinical experience. Hypermobility may be

generalised or limited to peripheral joints such as hands

When should pGALS be performed?

MSK presentations are a common feature of many chronic

diseases of childhood and not just arthritis. An MSK examination is one of the core systems along with cardiovascu2

and feet, and, generally speaking, younger female children

and those of non-Caucasian origin are more flexible. Benign

hypermobility is suggested by symmetrical hyperextension

at the fingers, elbows and knees and by flat pronated feet,

with normal arches on tiptoe.5

TABLE 1. Normal variants in gait patterns and leg

alignment.

Toewalking

Habitual toe-walking is common in

young children up to 3 years

In-toeing

Can be due to:

persistent femoral anteversion

(characterised by child walking with

patellae and feet pointing inwards;

common between ages 38 years)

internal tibial torsion (characterised

by child walking with patellae facing

forward and toes pointing inwards;

common from onset of walking to

3 years)

metatarsus adductus (characterised

by a flexible C-shaped lateral border

of the foot; most resolve by 6 years

Bow legs

(genu

varus)

Common from birth to the early toddler,

often with out-toeing (maximal at approx.

1 year); most resolve by 18 months

Knock

knees

(genu

valgus)

Common and often associated with

in-toeing (maximal at approx. 4 years);

most resolve by 7 years

Flat feet

Most children have flexible flat feet with

normal arches on tiptoeing; most resolve

by 6 years

Crooked

toes

Most resolve with weight-bearing

(assuming shoes and socks fit

comfortably)

Practical Tip normal variants: indications for referral

Children with hypermobility may present with mechanical

aches and pains after activity or as clumsy children, prone

to falls. It is important to consider non-benign causes of

hypermobility such as Marfans syndrome (which may be

suggested by tall habitus with long thin fingers, and higharched palate), and EhlersDanlos syndrome (which may

be suggested by easy bruising and skin elasticity, with poor

healing after minor trauma). Non-benign hypermobility is

genetically acquired and probing into the family history may

be revealing (e.g. cardiac deaths in Marfans syndrome).

The absence of normal arches on tiptoe suggests a nonmobile flat foot and warrants investigation (e.g. to exclude

tarsal coalition) and high fixed arches and persistent toewalking may suggest neurological disease. Conversely,

lack of joint mobility, especially if asymmetrical, is always

significant. Increased symmetrical calf muscle bulk associates with types of muscular dystrophy, and proximal myopathies may be suggested by delayed milestones such as

walking (later than 18 months) or inability to jump (in the

school-aged child).

TABLE 2. Normal major motor milestones.

Sit without support

68 months

Creep on hands and knees

911 months

Cruise when holding on to

furniture and standing upright,

or bottom shuffle

1112 months

Walk independently

1214 months

Climb up stairs on hands and

knees

approx. 15 months

Run stiffly

approx. 16 months

Walk down steps (non-reciprocal)

2024 months

Walk up steps, alternate feet

3 years

Hop on one foot, broad jump

4 years

Skip with alternate feet

5 years

Balance on one foot 20 seconds

67 years

Persistent changes (beyond the expected age ranges)

Progressive or asymmetrical changes

Short stature or dysmorphic features

Painful changes with functional limitation

Regression or delayed motor milestones

Abnormal joint examination elsewhere

Suggestion of neurological disease or developmental

delay

What to do if the pGALS screen is

abnormal

pGALS has been shown to have high sensitivity to detect

significant abnormalities. Following the screening examination, the observer is directed to a more detailed examination of the relevant area, based on the look, feel, move

principle as in the adult Regional Examination of the

Musculoskeletal System (called REMS).3 To date a validated

regional MSK examination for children does not exist, but

an evidence- and consensus-based approach to a childrens

regional examination (to be called pREMS) is currently being

developed by our research team; this project is funded by

arc and further educational resources are to follow.

The components of the pGALS musculoskeletal screen

The pGALS screen6 (see pp 46) includes three questions

relating to pain and function. However, a negative response

to these three questions in the context of a potential MSK

problem does not exclude significant MSK disease, and

3

The pGALS musculoskeletal screen

Screening questions

Do you (or does your child) have any pain or stiffness in your (their) joints, muscles or back?

Do you (or does your child) have any difficulty getting yourself (him/herself) dressed without any help?

Do you (or does your child) have any problem going up and down stairs?

FIGURE

SCREENING MANOEUVRES

WHAT IS BEING ASSESSED?

(Note the manoeuvres in bold are

additional to those in adult GALS2)

Observe the child standing

(from front, back and sides)

Posture and habitus

Skin rashes e.g. psoriasis

Deformity e.g. leg length

inequality, leg alignment

(valgus, varus at the knee

or ankle), scoliosis, joint

swelling, muscle wasting,

flat feet

Observe the child walking

and

Walk on your heels and

Walk on your tiptoes

Ankles, subtalar, midtarsal

and small joints of feet

and toes

Foot posture (note if

presence of normal

longitudinal arches of feet

when on tiptoes)

Hold your hands out

straight in front of you

Forward flexion of

shoulders

Elbow extension

Wrist extension

Extension of small joints

of fingers

Turn your hands over and

make a fist

Wrist supination

Elbow supination

Flexion of small joints of

fingers

Pinch your index finger and

thumb together

Manual dexterity

Coordination of small

joints of index finger and

thumb and functional

key grip

(continued)

4

FIGURE

SCREENING MANOEUVRES

WHAT IS BEING ASSESSED?

Touch the tips of your

fingers

Manual dexterity

Coordination of small

joints of fingers and

thumbs

Squeeze the metacarpophalangeal joints for

tenderness

Metacarpophalangeal

joints

Put your hands together

palm to palm and

Put your hands together

back to back

Extension of small joints

of fingers

Wrist extension

Elbow flexion

Reach up, touch the sky

and

Look at the ceiling

Put your hands behind your

neck

Shoulder abduction

External rotation of

shoulders

Elbow flexion

Elbow extension

Wrist extension

Shoulder abduction

Neck extension

(continued)

5

FIGURE

SCREENING MANOEUVRES

WHAT IS BEING ASSESSED?

Try and touch your shoulder

with your ear

Cervical spine lateral

flexion

Open wide and put three

(childs own) fingers in your

mouth

Temporomandibular joints

(and check for deviation of

jaw movement)

Feel for effusion at the

knee (patella tap, or crossfluctuation)

Knee effusion (small

effusion may be missed

by patella tap alone)

Active movement of knees

(flexion and extension) and

feel for crepitus

Knee flexion

Knee extension

Passive movement of hip

(knee flexed to 90, and

internal rotation of hip)

Hip flexion and internal

rotation

Bend forwards and touch

your toes?

Forward flexion of

thoraco-lumbar spine (and

check for scoliosis)

Documentation of the pGALS screen

Documentation of the pGALS screening assessment is important and a simple pro forma is proposed with

the following example a child with a swollen left knee with limited flexion of the knee and antalgic gait.

pGALS screening questions

Any pain?

Left knee

Problems with dressing?

No difficulty

Problems with walking?

Some difficulty on walking

Appearance

Gait

Movement

7

Arms

Legs

Spine

Summary

therefore at a minimum pGALS should be performed. In

children, it is not uncommon to find joint involvement

that has not been mentioned as part of the presenting

complaint; it is therefore essential to perform all parts of

the pGALS screen and check for verbal and non-verbal clues

of joint discomfort (such as facial expression, withdrawal of

limb, or refusal to be examined further).

The pGALS examination is a simple MSK screen that should

be performed as part of systems assessment of children.

Improved performance of MSK clinical skills and knowledge

of normal variants in childhood, common MSK conditions

and their mode of presentation, along with knowledge

of red flags to warrant concern, will facilitate diagnosis,

management and appropriate referral.

Observation with the child standing should be done from the

front, behind the child and from the side. Scoliosis may be

suggested by unequal shoulder height or asymmetrical skin

creases on the trunk, and may be more obvious on forward

flexion. From the front and back, leg alignment problems

such as valgus and varus deformities at the knee can be

observed; leg-length inequality may be more obvious from

the side and suggested by a flexed posture at the knee, and,

if found, then careful observation of the spine is important

to exclude a secondary scoliosis. For specific manoeuvres,

the child can copy the various screening manoeuvres as

they are performed by the examiner. Children often find

this fun and this can help with establishing rapport. It is

important to keep observing closely as children may only

cooperate briefly! The examination of the upper limbs and

neck is optimal with the child sitting on an examination

couch or on a parents knee, facing the examiner. The child

should then lie supine to allow the legs to be examined and

then stand again for spine assessment.

Further information and reading

A full demonstration of the pGALS screen is available from the Arthritis

Research Campaign (arc) as a free resource as a DVD and soon will

be available as a web-based resource: www.arc.org.uk/arthinfo/

emedia.asp. A video-clip of the screening manoeuvres can also be

accessed via the web version of this report: www.arc.org.uk/arthinfo/

medpubs/6535/6535.asp.

Jandial S, Foster HE. Examination of the musculoskeletal system in children: a simple approach. Paediatr Child Health 2008;18(2):47-55.

Szer I, Kimura Y, Malleson P, Southwood T (ed). Arthritis in adolescents

and children (juvenile idiopathic arthritis). Oxford University Press;

2006.

References

1. McGhee JL, Burks FN, Sheckels JL, Jarvis JN. Identifying children with

chronic arthritis based on chief complaints: absence of predictive

value for musculoskeletal pain as an indicator of rheumatic disease

in children. Pediatrics 2002;110(2 Pt 1):354-9.

Practical Tip while performing the pGALS screening

examination

2. Doherty M, Dacre J, Dieppe P, Snaith M. The GALS locomotor

screen. Ann Rheum Dis 1992;51(10):1165-9.

3. Clinical assessment of the musculoskeletal system: a handbook

for medical students (includes DVD Regional examination of the

musculoskeletal system for students). Arthritis Research Campaign;

2005. www.arc.org.uk/arthinfo/medpubs/6321/6321.asp.

Get the child to copy you doing the manoeuvres

Look for verbal and non-verbal clues of discomfort

(e.g. facial expression, withdrawal)

Do the full screen as the extent of joint involvement may

not be obvious from the history

Look for asymmetry (e.g. muscle bulk, joint swelling,

range of joint movement)

Consider clinical patterns (e.g. non-benign hypermobility

and Marfanoid habitus or skin elasticity) and association

of leg-length discrepancy and scoliosis)

4. Foster HE, Kay LJ, Friswell M, Coady D, Myers A. Musculoskeletal

screening examination (pGALS) for school-aged children based on

the adult GALS screen. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55(5):709-16.

5. Oliver J. Hypermobility. Reports on the Rheumatic Diseases (Series

5), Hands On 7. Arthritis Research Campaign; 2005 Oct.

6. pGALS Paediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, Spine. DVD. Arthritis Research

Campaign; 2006. www.arc.org.uk/arthinfo/emedia.asp.

COMMENT

Elspeth M Wise, MA, MBBChir, MRCGP, DRCOG

General Practitioner, Durham/former arc Education Fellow

This is an excellent report highlighting some important

areas in paediatric musculoskeletal disorders: clinical

skills and normal variants. Studies have shown that

children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are often

delayed in accessing appropriate, specialist rheumatology services. This delay can occur both in primary

care, where we may not recognise the symptoms early,

and in secondary care, where children may be under the

care of general paediatricians or orthopaedic surgeons

for a while before being referred. It is therefore important

that, as GPs, we know our local services and how best to

access them.

check the wrists (ask child to form the prayer sign

and then place their hands back to back)

screen the elbow and neck (ask child to touch the

sky and then look at the ceiling)

check the temporomandibular joints (ask child to

open their mouth and insert 3 fingers).

Normal variants are a common paediatric musculoskeletal presentation in primary care and can be a great

source of concern for both parents and doctor. One way

of remembering the variations in knee alignment is by

the rule of 6:* If the child is under 6 years old and

there is less than 6 cm between the knees (if has bow

legs) or 6 cm between the ankles (if has knock knees)

then the problem is likely to be self-limiting. If unsure

review and follow up the child.

Having used pGALs in primary care, I find the differences

between GALS and pGALS useful to remember, i.e.

screen the foot and ankle (ask child to walk on heels

and then tiptoes)

* Panayi G, Dickson DJ. Arthritis. In Clinical Practice Series. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004. pp 85-6.

This issue of Hands On can be downloaded as html or a PDF file from the Arthritis Research

Campaign website (www.arc.org.uk/about_arth/rdr5.htm and follow the links).

Hard copies of this and all other arc publications are obtainable via the on-line ordering system

(www.arc.org.uk/orders), by email (arc@bradshawsdirect.co.uk), or from: arc Trading Ltd,

James Nicolson Link, Clifton Moor, York YO30 4XX.

You might also like

- Narrative Reports On Seminar AttendedDocument10 pagesNarrative Reports On Seminar AttendedJaja63% (8)

- Diabetic KetoacidosisDocument38 pagesDiabetic KetoacidosisAwatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Benefits and Costs of Social Media in AdolescenceDocument7 pagesBenefits and Costs of Social Media in AdolescenceFlorina Anichitoae0% (1)

- Hands On pGALS Complete PDF 17 6 08Document8 pagesHands On pGALS Complete PDF 17 6 08Fakhre IbrahimNo ratings yet

- The Limping Child Pediatrics in Review 2015 Herman 184-97-0Document16 pagesThe Limping Child Pediatrics in Review 2015 Herman 184-97-0blume diaNo ratings yet

- #8 Evaluation of The Child With A Limp - UpToDateDocument45 pages#8 Evaluation of The Child With A Limp - UpToDatedagmawiNo ratings yet

- pGALS - Paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine A PDFDocument7 pagespGALS - Paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine A PDFTeodor ŞişianuNo ratings yet

- Knock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Document4 pagesKnock Kneed Children: Knee Alignment Can Be Categorized As Genu Valgum (Knock-Knee), Normal or Genu Varum (Bow Legged)Anna FaNo ratings yet

- AIJ - ClínicaDocument7 pagesAIJ - ClínicamonseibanezbarraganNo ratings yet

- Ortopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSDocument11 pagesOrtopedia Pediatrica en Recien Nacidos JAAOSjohnsam93No ratings yet

- Benard2020 PDFDocument26 pagesBenard2020 PDFArthur TeixeiraNo ratings yet

- Acute Childhood LimpDocument32 pagesAcute Childhood LimpStephanie R. S. HsuNo ratings yet

- Tuli Kongenital PDFDocument4 pagesTuli Kongenital PDFfauziahandnNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, and Spine AssessmentDocument74 pagesPediatric Gait, Arms, Legs, and Spine AssessmentCharisse Ann GasatayaNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric Physical Examination - Back, Extremities, Nervous System, Skin, and Lymph Nodes - UpToDateDocument12 pagesThe Pediatric Physical Examination - Back, Extremities, Nervous System, Skin, and Lymph Nodes - UpToDateNedelcu MirunaNo ratings yet

- PciDocument28 pagesPciLorenaSeclénNishiyamaNo ratings yet

- LimpDocument7 pagesLimpRakesh DudiNo ratings yet

- RCH Textbook of Paediatric OrthopaedicsDocument392 pagesRCH Textbook of Paediatric OrthopaedicsTimothy ChungNo ratings yet

- Rine 2018Document11 pagesRine 2018Edith SandovalNo ratings yet

- 09 Janalee TaylorDocument37 pages09 Janalee TaylorAsri RachmawatiNo ratings yet

- Williams2014Document10 pagesWilliams2014Eugeni Llorca BordesNo ratings yet

- 31.bone & Joint DisordersDocument128 pages31.bone & Joint DisordersSulistyawati WrimunNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice: The Spine From Birth To AdolescenceDocument6 pagesClinical Practice: The Spine From Birth To Adolescencechristian roblesNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology: Duchenne Muscular DystrophyDocument10 pagesPathophysiology: Duchenne Muscular DystrophyMukesh YadavNo ratings yet

- Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Young Athletes: Eric Small, MDDocument8 pagesChronic Musculoskeletal Pain in Young Athletes: Eric Small, MDАлексNo ratings yet

- Deslizamiento Epifisiario Femur OvidDocument7 pagesDeslizamiento Epifisiario Femur Ovidnathalia_pastasNo ratings yet

- 5 Different Type of SyndromeDocument6 pages5 Different Type of SyndromeAdnan RezaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Gait Disorders in ChildrenDocument3 pagesAssessment of Gait Disorders in ChildrenMadalina RarincaNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument5 pagesIntroductionmeowzi floraNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Hip ConditionsDocument2 pagesAdolescent Hip ConditionsJoão Pedro Ramos Sampaio Rocha João PedroNo ratings yet

- Symptoms of Talipes DiseaseDocument6 pagesSymptoms of Talipes DiseaseJustine DumaguinNo ratings yet

- Minimal Brain Dysfunctions MBD Causes Clinical Symptoms Deformity of The Feet Knees Hips Pelvis and Spine PhysiotherapyDocument9 pagesMinimal Brain Dysfunctions MBD Causes Clinical Symptoms Deformity of The Feet Knees Hips Pelvis and Spine PhysiotherapyAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- 1 Pediatric Musculoskeletal Disorders-2Document57 pages1 Pediatric Musculoskeletal Disorders-2naeemullahNo ratings yet

- Site Accessibility Contact Mychild Sitemap Select Language Create AccountDocument42 pagesSite Accessibility Contact Mychild Sitemap Select Language Create Accountretno widyastutiNo ratings yet

- 02 Developmental Dysplasia of The Hip - Clinical Features and Diagnosis PDFDocument41 pages02 Developmental Dysplasia of The Hip - Clinical Features and Diagnosis PDFAlexandra SotoNo ratings yet

- Dismorfología GeneralidadesDocument6 pagesDismorfología GeneralidadesLesley GalindoNo ratings yet

- A Sonographic Approach To The Prenatal Diagnosis of Skeletal DysplasiasDocument19 pagesA Sonographic Approach To The Prenatal Diagnosis of Skeletal DysplasiasminhhaiNo ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy: I. Definition/ DescriptionDocument4 pagesCerebral Palsy: I. Definition/ Descriptionfaye kim100% (1)

- Case Study PHDDocument42 pagesCase Study PHDJoy AntonetteNo ratings yet

- Pediatricspinalcordinjury: A Review by Organ SystemDocument24 pagesPediatricspinalcordinjury: A Review by Organ SystemDana DumitruNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric Neurological Exam Chapter by W LoganDocument34 pagesThe Pediatric Neurological Exam Chapter by W LoganStarLink1No ratings yet

- Cerebral Palsy: Recommended ReadingDocument5 pagesCerebral Palsy: Recommended ReadingJoey Ivan CristobalNo ratings yet

- Coxa PlanaDocument15 pagesCoxa PlanaAngelyn MoralNo ratings yet

- Arthritis FulltextDocument6 pagesArthritis FulltextAnuj Gupta100% (1)

- Pediatric Orthopedic ExaminationDocument21 pagesPediatric Orthopedic Examinationmmribeiroo51No ratings yet

- Refer - Pdfped PracticalDocument10 pagesRefer - Pdfped PracticalNana BananaNo ratings yet

- Give A 3-Sentence Summary of The Pertinent Features of The Case. What Other Details in TheDocument4 pagesGive A 3-Sentence Summary of The Pertinent Features of The Case. What Other Details in TheMiguel Andrei MedinaNo ratings yet

- COMPLICAÇÕES LESÃO CEREBRAL 1-S2.0-S1047965114001065-MainDocument8 pagesCOMPLICAÇÕES LESÃO CEREBRAL 1-S2.0-S1047965114001065-MainYury FelicianoNo ratings yet

- American Academy of Pediatrics: Developmental Dysplasia of The Hip Is TheDocument10 pagesAmerican Academy of Pediatrics: Developmental Dysplasia of The Hip Is Thelolamusic90No ratings yet

- Trastornos Del Movimiento Articulo 2Document7 pagesTrastornos Del Movimiento Articulo 2cfernandfuNo ratings yet

- Harris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootDocument33 pagesHarris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- ClubfootDocument9 pagesClubfootLorebell100% (5)

- GERIATRICDocument25 pagesGERIATRICDishani DeyNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Management For Cerebral PalsyDocument27 pagesNutrition Management For Cerebral PalsyPCMC Dietitians NDDNo ratings yet

- The Limping ChildDocument10 pagesThe Limping Childlybzia1No ratings yet

- Mayston People With Cerebral Palsy Effects of and Perspectives For TherapyDocument20 pagesMayston People With Cerebral Palsy Effects of and Perspectives For TherapyΒασίλης ΒασιλείουNo ratings yet

- 2.7.12 SpondylolisthesisDocument4 pages2.7.12 SpondylolisthesisArfadin YusufNo ratings yet

- Examination of The GaitDocument3 pagesExamination of The GaitBeenish IqbalNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument8 pagesArticleLusian VissNo ratings yet

- Peds 2013Document103 pagesPeds 2013cooperorthopaedicsNo ratings yet

- Normal Lower Limb Variants in ChildrenDocument11 pagesNormal Lower Limb Variants in ChildrenIulia MoldovanNo ratings yet

- Disorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementFrom EverandDisorders of the Patellofemoral Joint: Diagnosis and ManagementNo ratings yet

- HypoglycaemiaDocument36 pagesHypoglycaemiaAwatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Child With Bruises 00Document36 pagesChild With Bruises 00Awatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Nutrional Assessment and FFT SemifinalDocument39 pagesNutrional Assessment and FFT SemifinalAwatef Abushhiwa100% (1)

- Childhood Diabetes 2016Document64 pagesChildhood Diabetes 2016Awatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- PGALs Screening Questions 6965Document2 pagesPGALs Screening Questions 6965Awatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Jaundice-Neonatal 2016Document45 pagesJaundice-Neonatal 2016Awatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- PallorDocument27 pagesPallorAwatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Newborn ExaminationDocument72 pagesNewborn ExaminationAwatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Newborn ExaminationDocument72 pagesNewborn ExaminationAwatef AbushhiwaNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 2Document16 pagesAssessment Task 2Parveen KumariNo ratings yet

- Speech CommunicationDocument3 pagesSpeech CommunicationDAWA JAMES GASSIMNo ratings yet

- 1thesis Statement AnthroDocument3 pages1thesis Statement AnthroanaspirantNo ratings yet

- The Real Number System 1: Study SkillsDocument5 pagesThe Real Number System 1: Study SkillsDaniel VargasNo ratings yet

- IELTS - Researchers - Test Taker Performance 2012Document4 pagesIELTS - Researchers - Test Taker Performance 2012Nanda KumarNo ratings yet

- (Supplements To Novum Testamentum 012) John Hall Elliott - The Elect and The Holy 1966Document274 pages(Supplements To Novum Testamentum 012) John Hall Elliott - The Elect and The Holy 1966Novi Testamenti Lector100% (2)

- 1 - Lecture - What Is BiochemistryDocument24 pages1 - Lecture - What Is BiochemistrybotanokaNo ratings yet

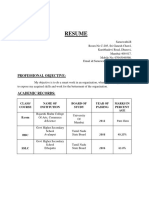

- Resume: Professional ObjectiveDocument3 pagesResume: Professional Objectivevinayak tiwariNo ratings yet

- 5 Minute Productivity HacksDocument8 pages5 Minute Productivity HacksPaul Samson TopacioNo ratings yet

- Total Number of Items Total Teaching Time For Quarter: Tuy National High SchoolDocument17 pagesTotal Number of Items Total Teaching Time For Quarter: Tuy National High SchoolBenzon MulingbayanNo ratings yet

- How Do Children Acquire Their Mother TongueDocument5 pagesHow Do Children Acquire Their Mother TongueGratia PierisNo ratings yet

- دليل اعداد الرساله للماسترDocument18 pagesدليل اعداد الرساله للماسترhamdy radyNo ratings yet

- Peer PressureDocument21 pagesPeer PressureLalisa's PetNo ratings yet

- Assignment GuidelineDocument6 pagesAssignment GuidelineZI YUEN PHANGNo ratings yet

- Certificate of BASKETBALLDocument4 pagesCertificate of BASKETBALLwilmerdirectoNo ratings yet

- Mathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students' Potential Through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching - Jo BoalerDocument5 pagesMathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students' Potential Through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching - Jo Boalergotufine0% (1)

- 2 Bejarano Benko - White Boards and PainDocument1 page2 Bejarano Benko - White Boards and Painapi-344178960No ratings yet

- CSB MST Test-III Project Management CS-604 (B) 1 - Google FormsDocument5 pagesCSB MST Test-III Project Management CS-604 (B) 1 - Google Formssumit jainNo ratings yet

- Group 4 Final ResearchDocument73 pagesGroup 4 Final ResearchChesca SalengaNo ratings yet

- Action Plan 21 22 English ClubDocument2 pagesAction Plan 21 22 English ClubCarolyn Dela RosaNo ratings yet

- Managing Your Team'S Csfs and GoalsDocument14 pagesManaging Your Team'S Csfs and GoalsMayFigueroaNo ratings yet

- Worksheets: The White Oryx - Penguin Readers (TESL) Starter LevelDocument2 pagesWorksheets: The White Oryx - Penguin Readers (TESL) Starter LevelMatthew IrwinNo ratings yet

- Radiohead - Ok Computer - ThesisDocument216 pagesRadiohead - Ok Computer - Thesisloadmess100% (3)

- Exercises For Task 2Document5 pagesExercises For Task 2Guarionex PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Ico International Fellowship Program 4089Document94 pagesIco International Fellowship Program 4089Devdutta NayakNo ratings yet

- Mysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryDocument326 pagesMysticism and Meaning MultidisciplinaryWiedzminNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus - Basic Grammar 2Document13 pagesCourse Syllabus - Basic Grammar 2Thúy HiềnNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH5 QUARTER4 MODULE1 WEEK1-3 How Visual and Multimedia ElementsDocument117 pagesENGLISH5 QUARTER4 MODULE1 WEEK1-3 How Visual and Multimedia ElementsLAWRENCE JEREMY BRIONESNo ratings yet