Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

Uploaded by

Raida Uceda GarniqueCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Studio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFDocument214 pagesStudio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFMohammad J Haddad78% (9)

- LeptospirosisDocument9 pagesLeptospirosisDeepu VijayaBhanuNo ratings yet

- Answers Case 26 - ACUTE DIARRHEA X 2 VignettesDocument7 pagesAnswers Case 26 - ACUTE DIARRHEA X 2 VignettesRAGHVENDRANo ratings yet

- Tutors Short Cases 1 8 With Answers 2018Document5 pagesTutors Short Cases 1 8 With Answers 2018RayNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case 7Document7 pagesClinical Case 7Beni KelnerNo ratings yet

- Fever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashDocument4 pagesFever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Dr. Doni Priambodo Wijisaksono, Sppd-KptiDocument33 pagesLeptospirosis: Dr. Doni Priambodo Wijisaksono, Sppd-KptialbaazaNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesLeptospirosis in ChildrenPramod KumarNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever: Dr. Dur Muhammad Khan (Mrcp. FRCP)Document52 pagesTyphoid Fever: Dr. Dur Muhammad Khan (Mrcp. FRCP)Osama HassanNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis FinalDocument5 pagesLeptospirosis FinalufrieNo ratings yet

- Lepto SpirosDocument6 pagesLepto SpirosMar OrdanzaNo ratings yet

- 8.3 Medicine - Tropical Infectious Diseases Leptospirosis 2014ADocument7 pages8.3 Medicine - Tropical Infectious Diseases Leptospirosis 2014ABhi-An BatobalonosNo ratings yet

- Locally Endemic DiseasesDocument23 pagesLocally Endemic DiseasesERMIAS, ZENDY I.No ratings yet

- Lepto Spiros IsDocument7 pagesLepto Spiros IslansoprazoleNo ratings yet

- Jurding Nisya Interna DR ArifDocument16 pagesJurding Nisya Interna DR ArifnisyadefiaNo ratings yet

- Acute Fulminent Leptospirosis With Multi-Organ Failure: Weil's DiseaseDocument4 pagesAcute Fulminent Leptospirosis With Multi-Organ Failure: Weil's DiseaseMuhFarizaAudiNo ratings yet

- A. Biswas, R. Kumar, A. Chaterjee, A. PanDocument5 pagesA. Biswas, R. Kumar, A. Chaterjee, A. PanShofura AzizahNo ratings yet

- LeptospirosisDocument10 pagesLeptospirosisrommel f irabagonNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesLeptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsJackii DoronilaNo ratings yet

- Asculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Document54 pagesAsculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Miguel M. Melchor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- M.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HDocument49 pagesM.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HMona MostafaNo ratings yet

- General Data: G.E.L. Male 3 Yo Roman Catholic Brgy. Dungon C. Mandurrio Iloilo CityDocument75 pagesGeneral Data: G.E.L. Male 3 Yo Roman Catholic Brgy. Dungon C. Mandurrio Iloilo CityRhaffy Bearneza RapaconNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Where Is Leptospirosis Found?Document4 pagesLeptospirosis: Where Is Leptospirosis Found?Ariffe Ad-dinNo ratings yet

- leptospirosis钩体Document29 pagesleptospirosis钩体russonegroNo ratings yet

- Lionaki - The Various Forms of Nephrotic SyndromeDocument4 pagesLionaki - The Various Forms of Nephrotic SyndromedewiNo ratings yet

- Anak 1Document4 pagesAnak 1Vega HapsariNo ratings yet

- LepsDocument4 pagesLepslynharee100% (1)

- And-Asses-At-Spring-Break-Pt-1-3/?from VBWN: LeptospirosisDocument8 pagesAnd-Asses-At-Spring-Break-Pt-1-3/?from VBWN: LeptospirosisEjie Boy IsagaNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Nurul Hidayu - Nashriq Aiman - Audi AdibahDocument28 pagesLeptospirosis: Nurul Hidayu - Nashriq Aiman - Audi AdibahAkshay D'souzaNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdominal PainDocument14 pagesAcute Abdominal PainTali SteedNo ratings yet

- Splenic Tuberculosis - A Rare PresentationDocument3 pagesSplenic Tuberculosis - A Rare PresentationasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Henoch - Schonlein Purpura (HSP) : - It Is The Most Common Cause of Non-Thrombocytopenic Purpura in ChildrenDocument23 pagesHenoch - Schonlein Purpura (HSP) : - It Is The Most Common Cause of Non-Thrombocytopenic Purpura in ChildrenLaith DmourNo ratings yet

- Enteric FeverDocument7 pagesEnteric FeverkudzaimuregidubeNo ratings yet

- 04 - Typhoid FeverDocument35 pages04 - Typhoid Feversoheil100% (1)

- LeptospirosisDocument7 pagesLeptospirosisFarah Nadia MoksinNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever AND Paratyphoid Fever: Guoli Lin Department of Infectious Diseases The Third Affiliated Hospital of SYSUDocument70 pagesTyphoid Fever AND Paratyphoid Fever: Guoli Lin Department of Infectious Diseases The Third Affiliated Hospital of SYSUDrDeepak PawarNo ratings yet

- Pancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial SepsisDocument16 pagesPancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial Sepsisiamralph89No ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever AppendicitisDocument71 pagesTyphoid Fever AppendicitisDionisius KevinNo ratings yet

- A Case of Typhoid Fever Presenting With Multiple ComplicationsDocument4 pagesA Case of Typhoid Fever Presenting With Multiple ComplicationsCleo CaminadeNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesLeptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyaudyodyNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesLeptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyTio Prima SNo ratings yet

- 4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedDocument11 pages4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedLoges TobyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Complication of Typhoid FeverDocument10 pagesSurgical Complication of Typhoid FeverHelsa Eldatarina JNo ratings yet

- 012 LeptospirosisDocument8 pages012 LeptospirosisSkshah1974No ratings yet

- Dengue Fever Case StudyDocument5 pagesDengue Fever Case StudyJen Faye Orpilla100% (1)

- 伤寒英文教案 Typhoid Fever-应若素Document36 pages伤寒英文教案 Typhoid Fever-应若素Wai Kwong ChiuNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis (Agn)Document42 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis (Agn)Rowshon AraNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis CasosDocument2 pagesLeptospirosis CasosfelipeNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Cavite State University Indang, CaviteDocument9 pagesLeptospirosis: Cavite State University Indang, CavitePatricia Marie MojicaNo ratings yet

- Practice Based Learning (Grand Round)Document48 pagesPractice Based Learning (Grand Round)AnnumNo ratings yet

- 04 - Typhoid FeverDocument31 pages04 - Typhoid FeverGloria MachariaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Recent Advances in Sickle Cell Anemia Management: DR Sunil JondhaleDocument45 pagesSeminar: Recent Advances in Sickle Cell Anemia Management: DR Sunil JondhaleSunjon JondhleNo ratings yet

- HFRS Vs LeptospirosisDocument5 pagesHFRS Vs LeptospirosisSarah RepinNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Case 4 LeptospirosisDocument5 pagesTutorial Case 4 LeptospirosisStrawberry ShortcakeNo ratings yet

- Group 3 CPDocument108 pagesGroup 3 CPRedzel Joy B. PoperaNo ratings yet

- Prezentare Caz Leptospiroza PDF TTF 9501 1Document4 pagesPrezentare Caz Leptospiroza PDF TTF 9501 1suvaialaluciamadalinNo ratings yet

- Malaria and LeptospirosisDocument18 pagesMalaria and LeptospirosisRasYa DINo ratings yet

- Lascano, Joanne Alyssa - RheumatologyDocument13 pagesLascano, Joanne Alyssa - RheumatologyJoanne Alyssa Hernandez LascanoNo ratings yet

- Heart Valve Disease: State of the ArtFrom EverandHeart Valve Disease: State of the ArtJose ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- 3a. FODDocument3 pages3a. FODRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- Fever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashDocument4 pagesFever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- A 56-Year-Old Man From Peru With Prolonged Fever and Severe AnaemiaDocument3 pagesA 56-Year-Old Man From Peru With Prolonged Fever and Severe AnaemiaRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- 3a. FODDocument3 pages3a. FODRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- 1b. TBP & VIHDocument4 pages1b. TBP & VIHRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- SRS Medical ManagementDocument7 pagesSRS Medical ManagementAtharv KatkarNo ratings yet

- Safety Questions & AnswersDocument18 pagesSafety Questions & AnswersKunal Singh100% (2)

- Validation and Qualification of Heating, Ventilation, Air ConDocument18 pagesValidation and Qualification of Heating, Ventilation, Air ConJai MurugeshNo ratings yet

- QC Case StudyDocument77 pagesQC Case StudyBibhudutta mishraNo ratings yet

- ParkerStore Corp001 UkDocument516 pagesParkerStore Corp001 UkMarcelo Partes de Oliveira100% (1)

- 17 Ortega PBBDocument14 pages17 Ortega PBBMaría Paula TorresNo ratings yet

- AG Nessel AmicusDocument66 pagesAG Nessel AmicusGuy Hamilton-Smith100% (1)

- Textbook Ebook Must Know High School Biology 2Nd Edition Kellie Ploeger Cox All Chapter PDFDocument43 pagesTextbook Ebook Must Know High School Biology 2Nd Edition Kellie Ploeger Cox All Chapter PDFben.elliam133100% (11)

- Volume Changes of ConcreteDocument17 pagesVolume Changes of ConcreteAljawhara AlnadiraNo ratings yet

- Mina NEGRA HUANUSHA 2 ParteDocument23 pagesMina NEGRA HUANUSHA 2 ParteRoberto VillegasNo ratings yet

- SAFC Supply Solutions - ProClin® PreservativeDocument2 pagesSAFC Supply Solutions - ProClin® PreservativeSAFC-Global100% (1)

- Cep Sop KSKDocument11 pagesCep Sop KSKSonrat100% (1)

- AST JSA Excavations.Document3 pagesAST JSA Excavations.md_rehan_2No ratings yet

- Ergonomic Analysis of Train Driver Workplace of Train Pendolino Ics - ReferatDocument8 pagesErgonomic Analysis of Train Driver Workplace of Train Pendolino Ics - ReferathitfromNo ratings yet

- Chrissa Mae T. Catindoy BS Medical Technology 3A: Group Classification Pathologic SignificanceDocument5 pagesChrissa Mae T. Catindoy BS Medical Technology 3A: Group Classification Pathologic SignificanceChrissa Mae Tumaliuan CatindoyNo ratings yet

- Installation and Maintenance Manual: GT210, GT410 and GT610 Series Miniature I/P - E/P TransducersDocument8 pagesInstallation and Maintenance Manual: GT210, GT410 and GT610 Series Miniature I/P - E/P TransducersStefano Bbc RossiNo ratings yet

- 22100243-SGPP Thesis Proposal Draft-As Of20feb23Document26 pages22100243-SGPP Thesis Proposal Draft-As Of20feb23FzyNo ratings yet

- July H12 H13 H14 Mess MenuDocument2 pagesJuly H12 H13 H14 Mess MenuMarcus GuyNo ratings yet

- Vacuum and Pressure Gauges For Fire Proteccion System 2311Document24 pagesVacuum and Pressure Gauges For Fire Proteccion System 2311Anonymous 8RFzObvNo ratings yet

- Colorbond Ultra Datasheet New V8Document2 pagesColorbond Ultra Datasheet New V8Gireesh Krishna KadimiNo ratings yet

- Cardio Series: Crossfit RigsDocument2 pagesCardio Series: Crossfit RigskuldeepnagarNo ratings yet

- Control of Hospital Acquired Infection PDFDocument36 pagesControl of Hospital Acquired Infection PDFPrakashNo ratings yet

- 3 - Le Chateliers Principle Experiment Chemistry LibreTextsDocument11 pages3 - Le Chateliers Principle Experiment Chemistry LibreTextsReynee Shaira Lamprea MatulacNo ratings yet

- Kolmeks Pump Catalogue Low PDFDocument260 pagesKolmeks Pump Catalogue Low PDFMykola Titov50% (2)

- Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionDocument7 pagesElectrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionМирослав Кузишин100% (1)

- The Life of Saint CadogDocument66 pagesThe Life of Saint CadogDima TacaNo ratings yet

- Factor Affecting Quality of TimberDocument3 pagesFactor Affecting Quality of TimberJitesh AnejaNo ratings yet

- Xenon 21-22 Sheet Without Answer (EUDIOMETRY)Document3 pagesXenon 21-22 Sheet Without Answer (EUDIOMETRY)Krishna GoyalNo ratings yet

- PDF Advances in Neuropharmacology Drugs and Therapeutics 1St Edition MD Sahab Uddin Editor Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Advances in Neuropharmacology Drugs and Therapeutics 1St Edition MD Sahab Uddin Editor Ebook Full Chapterjessie.alvarez949100% (6)

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

Uploaded by

Raida Uceda GarniqueOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

A 16-Year-Old Boy From Sri Lanka With Fever, Jaundice and Renal Failure

Uploaded by

Raida Uceda GarniqueCopyright:

Available Formats

27

A 16-YEAR-OLD BOY FROM

SRI LANKA WITH FEVER,

JAUNDICE AND RENAL

FAILURE

Ranjan Premaratna

Clinical Presentation

HISTORY

A 16-year-old Sri Lankan boy presents to a local hospital with fever, frontal headache and severe

body aches for two days. He has vomited two to three times during the illness and has not passed

any urine for the previous 12 hours. He does not have a cough, coryza or shortness of breath. He has

been attending school until his illness. He had been fishing in an urban water stream five days prior

to falling ill.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

The boy looks ill and drowsy. He is jaundiced and has subconjunctival haemorrhages (Figure 27-1).

There is no neck stiffness, however there is severe muscle tenderness, mainly involving the abdominal

wall and in the calves so that the patient finds it difficult to walk. There is no lymphadenopathy. The

liver is palpable at 4cm below the right costal margin and is tender. The spleen is not palpable. There

is mild bilateral renal angle tenderness. Body temperature is 38.3C. The pulse rate is 100bpm and

is low in volume. The blood pressure is 90/60mmHg. The cardiac apex is not shifted. Examination

of the lungs and the CNS are normal.

FURTHER INVESTIGATIONS

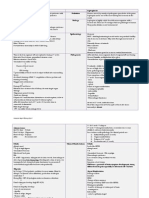

The laboratory findings are summarized in Table 27-1. The urine microscopy shows 20 red blood cells

per high-power field, proteins + and granular casts +. A chest radiograph is normal. An ECG shows

sinus tachycardia.

FIGURE 27-1 Jaundice and subconjunctival haemorrhages.

130

CASE 27 131

TABLE 27-1 Laboratory Results on Admission

Parameter

9

WBC (10 /L) (neutrophils : lymphocytes)

Haemoglobin (g/dL)

Platelets (109/L)

AST (IU/L)

ALT (IU/L)

ALP (IU/L)

Serum bilirubin total (mol/L)

Serum bilirubin direct (mol/L)

Blood urea nitrogen (mol/L)

Serum creatinine (mol/L)

C-reactive protein (mg/L)

Patient

Reference

5.7 (68%: 31%)

14.8

96

64

58

246

77

54.7

20.7

212.2

48

410

1216

150350

1333

325

40130

13.730.8

<5

2.56.4

71106

<5

QUESTIONS

1. What is the most likely diagnosis and what are your differentials?

2. What tests are indicated to confirm the diagnosis?

Discussion

A Sri Lankan teenage boy presents with fever, severe body aches and a reduced urine output. He is

jaundiced with subconjunctival haemorrhages and has a tender hepatomegaly. He has had contact with

a water stream prior to ill health.

His laboratory results show signs of cholestasis with only mildly elevated transaminases. The creatinine is increased twofold and there is thrombocytopenia. The leukocyte count is normal.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 1

What is the Most Likely Diagnosis and What Are Your Differentials?

An acute febrile illness accompanied by jaundice, renal failure and conjunctival haemorrhages should

raise the suspicion of leptospirosis, particularly in case of a history involving exposure to potentially

contaminated water.

Scrub typhus is another very common infection in South Asia. It may present with an acute onset

of fever, hepatomegaly and renal failure. There usually is lymphadenopathy and on careful examination

one may spot an eschar. Subconjunctival haemorrhages have been described but are less common than

in leptospirosis and complications such as renal failure tend to occur late in the infection (after about

seven days).

Hantavirus infection may cause a haemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome. It has a similar epidemiology to leptospirosis and is also associated with contact to rodent excreta.

Dengue haemorrhagic fever (DHF) is another differential diagnosis to consider. It also presents

with fever, severe myalgias, thrombocytopenia and haemorrhages. Jaundice is uncommon for DHF.

ANSWER TO QUESTION 2

What Tests Are Indicated to Confirm the Diagnosis?

A definitive diagnosis of leptospirosis is based upon the isolation of Leptospira spp. or a positive

microscopic agglutination test (MAT).

Isolation of the bacteria from blood or CSF is only possible during the first week of the disease.

Culture results may take 23 weeks and need to be examined weekly by dark field or phase-contrast

microscopy since the bacteria stain poorly. This technique is not routine practice in a standard microbiological laboratory.1

The MAT cannot differentiate between current or past infections. Therefore two consecutive serum

samples should be examined to look for seroconversion or an at least fourfold rise in titre. The significance of titres in single serum specimens is a matter of debate.

132 SECTION 2 CLINICAL CASES DISCUSSION AND ANSWERS

THE CASE CONTINUED

Severe leptospirosis was suspected and the patient was commenced on empirical benzylpenicillin.

Despite rehydration he developed acute renal failure warranting haemodialysis (HD). He developed

myocarditis and atrial fibrillation, but luckily tolerated further HD. He gradually recovered over ten

days with intensive care management.

SUMMARY BOX

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease that occurs worldwide. It is caused by pathogenic Leptospira spp.,13 which belong to the

spirochaetes. The most common species causing disease in humans and animals are L. interrogans and L. borgpetersenii.

Humans become infected through direct contact with urine of infected mammalian hosts, animal abortion products, or

contact with contaminated water. The major reservoirs are rodents, canines, livestock and wild mammals. The people most at

risk are slum dwellers and those with an occupational or recreational exposure involving animal contact or immersion in water.

Also, natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods may put people at risk.

The bacteria enter the human body through cuts or abrasions of the skin or through intact mucous membranes. The incubation period is 230 days. The spectrum of disease ranges from asymptomatic to severe infection.

The classical presentation of leptospirosis is that of a biphasic illness. The initial leptospiraemic phase usually starts abruptly.

Symptoms are nonspecific with fever, headache, sore throat, abdominal pain and a rash. Severe myalgias, most notably of the

calf and the lumbar area and conjunctival suffusions, have been mentioned as distinguishing physical findings.3 This first phase

lasts for a week and is followed by a second phase dominated by immune-mediated pathology.

Five to ten per cent of those with clinical infection will develop severe leptospirosis with cholestatic jaundice, acute kidney

injury and haemorrhagic diathesis (Weils syndrome). Further complications include pulmonary involvement, aseptic meningitis

and myocarditis.

A definitive diagnosis of leptospirosis is based upon the isolation of Leptospira spp. from blood or CSF, or the positive microscopic agglutination test (MAT). Both are laborious and not widely available.

Leptospirosis is usually treated with antibiotics, although the usefulness of antibiotic treatment in particular during the second,

immune-mediated phase of illness has been disputed.

For uncomplicated cases, oral doxycycline is the drug of choice. Alternatives include amoxicillin and azithromycin. In severe

infection benzylpenicillin, IV doxycycline, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime seem to have similar efficacy. Doxycycline 200mg weekly

has been suggested as exposure prophylaxis.

Further Reading

1. Chierakul KW. Leptospirosis. In: Farrar J, editor. Mansons Tropical Diseases. 23rd ed. London: Elsevier; 2013 [chapter

37].

2. WHO. Human leptospirosis: guidance for diagnosis, surveillance and control. In: World Health Organization and International Leptospirosis Society, editors. Geneva: WHO; 2003.

3. Bharti AR, Nally JE, Ricaldi JN, etal. Leptospirosis: a zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect Dis

2003;3(12):75771.

You might also like

- Studio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFDocument214 pagesStudio4 LEED v4 Green Associate 101 Questions & 101 Answers First Edition PDFMohammad J Haddad78% (9)

- LeptospirosisDocument9 pagesLeptospirosisDeepu VijayaBhanuNo ratings yet

- Answers Case 26 - ACUTE DIARRHEA X 2 VignettesDocument7 pagesAnswers Case 26 - ACUTE DIARRHEA X 2 VignettesRAGHVENDRANo ratings yet

- Tutors Short Cases 1 8 With Answers 2018Document5 pagesTutors Short Cases 1 8 With Answers 2018RayNo ratings yet

- Clinical Case 7Document7 pagesClinical Case 7Beni KelnerNo ratings yet

- Fever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashDocument4 pagesFever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Dr. Doni Priambodo Wijisaksono, Sppd-KptiDocument33 pagesLeptospirosis: Dr. Doni Priambodo Wijisaksono, Sppd-KptialbaazaNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis in ChildrenDocument5 pagesLeptospirosis in ChildrenPramod KumarNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever: Dr. Dur Muhammad Khan (Mrcp. FRCP)Document52 pagesTyphoid Fever: Dr. Dur Muhammad Khan (Mrcp. FRCP)Osama HassanNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis FinalDocument5 pagesLeptospirosis FinalufrieNo ratings yet

- Lepto SpirosDocument6 pagesLepto SpirosMar OrdanzaNo ratings yet

- 8.3 Medicine - Tropical Infectious Diseases Leptospirosis 2014ADocument7 pages8.3 Medicine - Tropical Infectious Diseases Leptospirosis 2014ABhi-An BatobalonosNo ratings yet

- Locally Endemic DiseasesDocument23 pagesLocally Endemic DiseasesERMIAS, ZENDY I.No ratings yet

- Lepto Spiros IsDocument7 pagesLepto Spiros IslansoprazoleNo ratings yet

- Jurding Nisya Interna DR ArifDocument16 pagesJurding Nisya Interna DR ArifnisyadefiaNo ratings yet

- Acute Fulminent Leptospirosis With Multi-Organ Failure: Weil's DiseaseDocument4 pagesAcute Fulminent Leptospirosis With Multi-Organ Failure: Weil's DiseaseMuhFarizaAudiNo ratings yet

- A. Biswas, R. Kumar, A. Chaterjee, A. PanDocument5 pagesA. Biswas, R. Kumar, A. Chaterjee, A. PanShofura AzizahNo ratings yet

- LeptospirosisDocument10 pagesLeptospirosisrommel f irabagonNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsDocument6 pagesLeptospirosis: Causes, Incidence, and Risk FactorsJackii DoronilaNo ratings yet

- Asculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Document54 pagesAsculitis Syndromes: Emily B. Martin, MD Rheumatology Board Review April 9, 2008Miguel M. Melchor RodríguezNo ratings yet

- M.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HDocument49 pagesM.D Pediatrics PH.D Pediatric Special Need and Nutrition Consultant Mansoura National Hospital Insurance H Fever H and Egyptian Liver HMona MostafaNo ratings yet

- General Data: G.E.L. Male 3 Yo Roman Catholic Brgy. Dungon C. Mandurrio Iloilo CityDocument75 pagesGeneral Data: G.E.L. Male 3 Yo Roman Catholic Brgy. Dungon C. Mandurrio Iloilo CityRhaffy Bearneza RapaconNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Where Is Leptospirosis Found?Document4 pagesLeptospirosis: Where Is Leptospirosis Found?Ariffe Ad-dinNo ratings yet

- leptospirosis钩体Document29 pagesleptospirosis钩体russonegroNo ratings yet

- Lionaki - The Various Forms of Nephrotic SyndromeDocument4 pagesLionaki - The Various Forms of Nephrotic SyndromedewiNo ratings yet

- Anak 1Document4 pagesAnak 1Vega HapsariNo ratings yet

- LepsDocument4 pagesLepslynharee100% (1)

- And-Asses-At-Spring-Break-Pt-1-3/?from VBWN: LeptospirosisDocument8 pagesAnd-Asses-At-Spring-Break-Pt-1-3/?from VBWN: LeptospirosisEjie Boy IsagaNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Nurul Hidayu - Nashriq Aiman - Audi AdibahDocument28 pagesLeptospirosis: Nurul Hidayu - Nashriq Aiman - Audi AdibahAkshay D'souzaNo ratings yet

- Acute Abdominal PainDocument14 pagesAcute Abdominal PainTali SteedNo ratings yet

- Splenic Tuberculosis - A Rare PresentationDocument3 pagesSplenic Tuberculosis - A Rare PresentationasclepiuspdfsNo ratings yet

- Henoch - Schonlein Purpura (HSP) : - It Is The Most Common Cause of Non-Thrombocytopenic Purpura in ChildrenDocument23 pagesHenoch - Schonlein Purpura (HSP) : - It Is The Most Common Cause of Non-Thrombocytopenic Purpura in ChildrenLaith DmourNo ratings yet

- Enteric FeverDocument7 pagesEnteric FeverkudzaimuregidubeNo ratings yet

- 04 - Typhoid FeverDocument35 pages04 - Typhoid Feversoheil100% (1)

- LeptospirosisDocument7 pagesLeptospirosisFarah Nadia MoksinNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever AND Paratyphoid Fever: Guoli Lin Department of Infectious Diseases The Third Affiliated Hospital of SYSUDocument70 pagesTyphoid Fever AND Paratyphoid Fever: Guoli Lin Department of Infectious Diseases The Third Affiliated Hospital of SYSUDrDeepak PawarNo ratings yet

- Pancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial SepsisDocument16 pagesPancytopenia Secondary To Bacterial Sepsisiamralph89No ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever AppendicitisDocument71 pagesTyphoid Fever AppendicitisDionisius KevinNo ratings yet

- A Case of Typhoid Fever Presenting With Multiple ComplicationsDocument4 pagesA Case of Typhoid Fever Presenting With Multiple ComplicationsCleo CaminadeNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesLeptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyaudyodyNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyDocument4 pagesLeptospirosis (Weil's Disease) : EpidemiologyTio Prima SNo ratings yet

- 4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedDocument11 pages4th Year Write Up 2 - Int. MedLoges TobyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Complication of Typhoid FeverDocument10 pagesSurgical Complication of Typhoid FeverHelsa Eldatarina JNo ratings yet

- 012 LeptospirosisDocument8 pages012 LeptospirosisSkshah1974No ratings yet

- Dengue Fever Case StudyDocument5 pagesDengue Fever Case StudyJen Faye Orpilla100% (1)

- 伤寒英文教案 Typhoid Fever-应若素Document36 pages伤寒英文教案 Typhoid Fever-应若素Wai Kwong ChiuNo ratings yet

- Acute Glomerulonephritis (Agn)Document42 pagesAcute Glomerulonephritis (Agn)Rowshon AraNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis CasosDocument2 pagesLeptospirosis CasosfelipeNo ratings yet

- Leptospirosis: Cavite State University Indang, CaviteDocument9 pagesLeptospirosis: Cavite State University Indang, CavitePatricia Marie MojicaNo ratings yet

- Practice Based Learning (Grand Round)Document48 pagesPractice Based Learning (Grand Round)AnnumNo ratings yet

- 04 - Typhoid FeverDocument31 pages04 - Typhoid FeverGloria MachariaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Recent Advances in Sickle Cell Anemia Management: DR Sunil JondhaleDocument45 pagesSeminar: Recent Advances in Sickle Cell Anemia Management: DR Sunil JondhaleSunjon JondhleNo ratings yet

- HFRS Vs LeptospirosisDocument5 pagesHFRS Vs LeptospirosisSarah RepinNo ratings yet

- Tutorial Case 4 LeptospirosisDocument5 pagesTutorial Case 4 LeptospirosisStrawberry ShortcakeNo ratings yet

- Group 3 CPDocument108 pagesGroup 3 CPRedzel Joy B. PoperaNo ratings yet

- Prezentare Caz Leptospiroza PDF TTF 9501 1Document4 pagesPrezentare Caz Leptospiroza PDF TTF 9501 1suvaialaluciamadalinNo ratings yet

- Malaria and LeptospirosisDocument18 pagesMalaria and LeptospirosisRasYa DINo ratings yet

- Lascano, Joanne Alyssa - RheumatologyDocument13 pagesLascano, Joanne Alyssa - RheumatologyJoanne Alyssa Hernandez LascanoNo ratings yet

- Heart Valve Disease: State of the ArtFrom EverandHeart Valve Disease: State of the ArtJose ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- 3a. FODDocument3 pages3a. FODRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- Fever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashDocument4 pagesFever With Jaundice and A Purpuric RashRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- A 56-Year-Old Man From Peru With Prolonged Fever and Severe AnaemiaDocument3 pagesA 56-Year-Old Man From Peru With Prolonged Fever and Severe AnaemiaRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- 3a. FODDocument3 pages3a. FODRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- 1b. TBP & VIHDocument4 pages1b. TBP & VIHRaida Uceda GarniqueNo ratings yet

- SRS Medical ManagementDocument7 pagesSRS Medical ManagementAtharv KatkarNo ratings yet

- Safety Questions & AnswersDocument18 pagesSafety Questions & AnswersKunal Singh100% (2)

- Validation and Qualification of Heating, Ventilation, Air ConDocument18 pagesValidation and Qualification of Heating, Ventilation, Air ConJai MurugeshNo ratings yet

- QC Case StudyDocument77 pagesQC Case StudyBibhudutta mishraNo ratings yet

- ParkerStore Corp001 UkDocument516 pagesParkerStore Corp001 UkMarcelo Partes de Oliveira100% (1)

- 17 Ortega PBBDocument14 pages17 Ortega PBBMaría Paula TorresNo ratings yet

- AG Nessel AmicusDocument66 pagesAG Nessel AmicusGuy Hamilton-Smith100% (1)

- Textbook Ebook Must Know High School Biology 2Nd Edition Kellie Ploeger Cox All Chapter PDFDocument43 pagesTextbook Ebook Must Know High School Biology 2Nd Edition Kellie Ploeger Cox All Chapter PDFben.elliam133100% (11)

- Volume Changes of ConcreteDocument17 pagesVolume Changes of ConcreteAljawhara AlnadiraNo ratings yet

- Mina NEGRA HUANUSHA 2 ParteDocument23 pagesMina NEGRA HUANUSHA 2 ParteRoberto VillegasNo ratings yet

- SAFC Supply Solutions - ProClin® PreservativeDocument2 pagesSAFC Supply Solutions - ProClin® PreservativeSAFC-Global100% (1)

- Cep Sop KSKDocument11 pagesCep Sop KSKSonrat100% (1)

- AST JSA Excavations.Document3 pagesAST JSA Excavations.md_rehan_2No ratings yet

- Ergonomic Analysis of Train Driver Workplace of Train Pendolino Ics - ReferatDocument8 pagesErgonomic Analysis of Train Driver Workplace of Train Pendolino Ics - ReferathitfromNo ratings yet

- Chrissa Mae T. Catindoy BS Medical Technology 3A: Group Classification Pathologic SignificanceDocument5 pagesChrissa Mae T. Catindoy BS Medical Technology 3A: Group Classification Pathologic SignificanceChrissa Mae Tumaliuan CatindoyNo ratings yet

- Installation and Maintenance Manual: GT210, GT410 and GT610 Series Miniature I/P - E/P TransducersDocument8 pagesInstallation and Maintenance Manual: GT210, GT410 and GT610 Series Miniature I/P - E/P TransducersStefano Bbc RossiNo ratings yet

- 22100243-SGPP Thesis Proposal Draft-As Of20feb23Document26 pages22100243-SGPP Thesis Proposal Draft-As Of20feb23FzyNo ratings yet

- July H12 H13 H14 Mess MenuDocument2 pagesJuly H12 H13 H14 Mess MenuMarcus GuyNo ratings yet

- Vacuum and Pressure Gauges For Fire Proteccion System 2311Document24 pagesVacuum and Pressure Gauges For Fire Proteccion System 2311Anonymous 8RFzObvNo ratings yet

- Colorbond Ultra Datasheet New V8Document2 pagesColorbond Ultra Datasheet New V8Gireesh Krishna KadimiNo ratings yet

- Cardio Series: Crossfit RigsDocument2 pagesCardio Series: Crossfit RigskuldeepnagarNo ratings yet

- Control of Hospital Acquired Infection PDFDocument36 pagesControl of Hospital Acquired Infection PDFPrakashNo ratings yet

- 3 - Le Chateliers Principle Experiment Chemistry LibreTextsDocument11 pages3 - Le Chateliers Principle Experiment Chemistry LibreTextsReynee Shaira Lamprea MatulacNo ratings yet

- Kolmeks Pump Catalogue Low PDFDocument260 pagesKolmeks Pump Catalogue Low PDFMykola Titov50% (2)

- Electrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionDocument7 pagesElectrical Conductivity of Carbon Blacks Under CompressionМирослав Кузишин100% (1)

- The Life of Saint CadogDocument66 pagesThe Life of Saint CadogDima TacaNo ratings yet

- Factor Affecting Quality of TimberDocument3 pagesFactor Affecting Quality of TimberJitesh AnejaNo ratings yet

- Xenon 21-22 Sheet Without Answer (EUDIOMETRY)Document3 pagesXenon 21-22 Sheet Without Answer (EUDIOMETRY)Krishna GoyalNo ratings yet

- PDF Advances in Neuropharmacology Drugs and Therapeutics 1St Edition MD Sahab Uddin Editor Ebook Full ChapterDocument53 pagesPDF Advances in Neuropharmacology Drugs and Therapeutics 1St Edition MD Sahab Uddin Editor Ebook Full Chapterjessie.alvarez949100% (6)