Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lobbying and Law - Digital Democrats Move On': October 18, 2003

Lobbying and Law - Digital Democrats Move On': October 18, 2003

Uploaded by

politix0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views6 pagesOriginal Title

00227-nationaljrnl1003

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views6 pagesLobbying and Law - Digital Democrats Move On': October 18, 2003

Lobbying and Law - Digital Democrats Move On': October 18, 2003

Uploaded by

politixCopyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 6

National Journal, October 18, 2003

Lobbying and Law - Digital Democrats ‘Move On’

Louis Jacobson

In the old days, political rebels took matters to the streets. These days, a low-key

revolutionary like Zack Exley can energize the electorate from a chair in a coffee shop.

Exley, 33, is the organizing director of MoveOn.org, the liberal e- mail network that has

taken the political establishment by storm. Before plunging into an interview with

National Journal, Exley pulled out his laptop, logged on to the wireless Internet

connection at the Starbucks on Washington’s Dupont Circle, punched a few keys, and

instantly sent an e- mail urging half a million MoveOn activists to fight against the recall

of California Democratic Gov. Gray Davis.

It’s the kind of mass mobilization that MoveOn has been perfecting, by trial and error,

ever since the impeachment proceedings against President Clinton—the event that lent

the organization its original name in 1998, “Censure and Move On.” Since then, MoveOn

has surfed a wave of Democratic frustration, over issues from the war in Iraq to the Texas

redistricting fight to the media-ownership squabble at the Federal Communications

Commission. In fits and starts, MoveOn has amassed an e- mail database of 1.6 million

Americans, plus another 700,000 people in other countries (primarily opponents of the

war).

John Hlinko, an early MoveOn staffer who recently became director of Internet strategy

for Wesley Clark’s presidential campaign, describes MoveOn as “a tool for aggregating

and channeling popular discontent in a productive fashion. For people in America who

are ticked off, but scattered, it provides a great mechanism to channel that ticked-

offedness back to members of Congress.”

Michael Cornfield, research director of the George Washington University Institute for

Politics, Democracy, and the Internet, calls the folks at MoveOn “political alchemists”

who “have shown that they can turn the reaction to news into political power.”

Experts say that MoveOn—founded by Wes Boyd and Joan Blades, a married couple

who made a small fortune in software during the 1990s—has succeeded less because of a

stunning technological insight than because of the accumulation of modest advances in

organizing technique and Internet presentation.

MoveOn has become expert at slicing and dicing its database by geographic area and

political interests, which allows it to swiftly funnel its members’ concerns, and their

money, to the most appropriate political figures. In some cases, the group has set up user-

friendly pages that let members give money to specific advertising campaigns, thus

heightening the transparency of donations and giving members a sense of control over

how their money is spent.

Most important, perhaps, has been the group’s ethos of experimentation and flexibility.

Having outlived the impeachment debate, MoveOn stays relevant by reinventing itself

whenever a political crisis resonates among liberal voters. Fittingly, MoveOn is able to

“move on” whenever the political landscape changes.

“Wes and Joan, in addition to being politically savvy, are dot-commers who understand

that the way to succeed is to keep tweaking and tinkering until you get it right,” Cornfield

says. “Now because of their work on Iraq and impeachment, they’re able to exert

significant muscle.” Other experts agree that MoveOn’s ability to become a vessel for a

variety of political efforts has helped broaden its appeal.

MoveOn chooses its projects by listening to its members. Organizers gather this

intelligence through unsolicited e- mails from participants as well as occasional questions

sent out to its members, Exley says.

For instance, MoveOn’s online Democratic primary earlier this year emerged after

organizers asked members whether they wanted one; more than 95 percent of those who

responded said yes. As it turned out, no candidate won the required 50 percent of votes to

earn MoveOn’s official endorsement. (Former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean—who had

by then become a master of online fundraising— finished first, with 44 percent of the

318,000 votes cast.)

Simon Rosenberg, president of the middle-of-the-road New Democrat Network, sees

MoveOn as part of the leading edge of a fundamental change in which politics “left the

broadcast era and entered the digital age.” The Internet is allowing millions to participate

in the political system as never before, he says, adding, “The 2004 election will look like

a massive battle scene from Star Wars, with tens of millions of people fighting the fight

every day. That’s what democracy should be about.”

Even Larry Purpuro, a conservative who runs the Internet marketing company Rightclick

Strategies, admires MoveOn’s accomplishments. MoveOn has “built an online army,”

Purpuro says. “Unlike a lot of organizations who are trying to use the Web, they clearly

understand that it’s about e- mail, not about a pretty Web site.”

MoveOn’s timing was right because the group entered the political fray just as voters’

confidence in political parties was declining, says Dan Carol, a Democratic political

strategist. “People are looking for trusted filters,” he says. Belatedly, such key liberal

organizations as the AFL-CIO and the Democratic National Committee are now playing

catch-up, attempting to boost their Internet organizing capabilities.

MoveOn’s success was hardly preordained. Ever since the Internet emerged as a major

medium in the mid-1990s, savvy politicos have figured that it would offer a cheap,

efficient way of mobilizing voters. But early efforts, such as Grassroots.com,

Speakout.com, and Voter.com, met with disappointment and either shut down or entered

new lines of business. Rather than using the “we-will-build- it-and-they-will-come”

model, Boyd says, MoveOn goes to the 1.6 million people “who know us already, and we

say, ‘We have a question—what do you think about Iraq?’ We’ll get tens of thousands of

people responding, and that’s real energy.”

MoveOn is also credited with attracting political- minded people who have little patience

for conventional forms of political trench warfare. MoveOn participants aren’t interested

“in the traditional, shoe- leather stuff,” says Ruy Teixeira, co-author of The Emerging

Democratic Majority and a rank-and-file participant in MoveOn. “To the extent they’re

roping in these types of people and pointing them toward politics, I think it’s just great

for the Democrats.”

Remarkably, MoveOn has accomplished all this on the cheap. The group boasts only

four staffers, plus its founders, who continue to guide MoveOn without pay. The group

has no fancy headquarters; staffers tend to work out of their homes, and much of the

technical support is outsourced as the need arises. “I think it’s impressive, and frightening

to established political organizations that have plenty of bureaucracy and little success”

on the Internet, Purpuro says.

The spirit of MoveOn is embodied in its founders, whose Northern California

unpretentiousness explains why the duo is universally known as “Wes and Joan.” The

couple is considered extremely casual. Hlinko says they seem to enjoy themselves the

most while hosting dance parties for friends at their home.

Boyd is the grandson of an autoworker and the son of a University of California

(Berkeley) political science professor who got his education through the GI Bill. As a

youngster, he remembers many political discussions around the dinner table. A lifelong

Democrat, Boyd calls himself “a progressive” with “a deep respect for the Framers of the

Constitution, and checks and balances.” His liberalism, however, is leavened with real-

world experience as an entrepreneur. In 1997, the couple sold Berkeley Systems—a

software company best-known for its “Flying Toasters” screensaver—to Cendant for

$13.8 million.

Within months of the sale, the Clinton impeachment became a national obsession. As

would be the case several years later with the war in Iraq, the couple detected a vacuum

where a place for critics to express their views was needed. So they provided one.

“We shared the frustration that a lot of people felt—that so much of our national time was

being spent on impeachment,” Boyd recalls. “So I put together a Web site that said that

we should move on, and I shared it with a few friends. It was clear that people were

passionate and frustrated, but couldn’t make contact with leaders in Washington, D.C.

From that point, we tried to help those people be effective in communicating [with] their

leaders.”

Exley credits Boyd and Blades with establishing just the right tone—passionate but

levelheaded. “We send out these e-mails just as if they’re going to our friends and

colleagues,” Exley says. “We’re not talking down to people, we’re assuming they are just

as angry as we are.”

Exley himself became a favorite among Web activists during the 2000 campaign when he

posted a parody on then-candidate George W. Bush, called GWBush.com. The site,

which had stories poking fun at some Bush missteps, caught the Bush campaign’s

attention. At a news conference, Bush attacked Exley as a “garbage man,” saying that

such Web sites show that “there ought to be limits to freedom.” Afterward, Exley’s site

logged even more visitors.

Whether these same folks or others are receiving MoveOn’s missives is not entirely clear,

because MoveOn has not undertaken sustained, sophisticated surveys. Outsiders

speculate that MoveOn’s minions are whiter, more liberal, and more likely to be

professionals than the Democratic Party as a whole. Boyd says that, from scattered

evidence, the member base appears to be roughly similar to the Democratic population as

a whole, but probably “a bit younger and a little bit more educated.”

Activists who have partnered with MoveOn say the group is uncompetitive when

cooperating with other groups. Part of that has to do with the fact that Boyd and Blades

do not want MoveOn to become a diversified advocacy organization. “They have very

little institutional ego,” says Chellie Pingree, the president and CEO of Common Cause,

which worked with MoveOn to stop an FCC effort to lift restrictions on media

ownership. “They’re far more dedicated to advancing the causes they’re concerned about

and giving the public a voice than they are about institution-building. And they don’t

keep closely guarded secrets. Any question we ask, they answer.”

MoveOn’s cooperative approach owes something to the fact that its small staff can’t do

everything by itself. “The best issue campaigns combine an online component with an

on-the-ground component,” says Ralph G. Neas, president of the liberal advocacy group

People for the American Way, which has partnered with MoveOn to fight some of

President Bush’s judicial nominees. “You have to have on-the-ground activists meeting,

physically, with members of Congress in their home districts. The combination of the two

is stronger than either one separately.”

In early 2003, People for the American Way and MoveOn joined with Working Assets,

another liberal group, to set up home-state meetings with almost 50 senators to discuss

the Bush administration’s judicial appointees. Common Cause partnered with MoveOn

on the FCC campaign, resulting in an online petition with 340,000 signatures, including

200,000 sent to the FCC over a two-day period.

MoveOn’s members don’t just contribute opinions to the group, they give money, too.

Boyd says that MoveOn spent $2.3 million on operations from July 2002 through June

2003, up from $250,000 in the previous 12- month period. He estimates MoveOn will

spend significantly more this year. At the height of the Iraq debate this spring, MoveOn

sent out an appeal to help pay for a $50,000 advertising campaign in The New York

Times. It received $400,000, almost overnight. Much of that total came in the form of

$40 contributions from rank-and-file participants. MoveOn’s political action committee,

which is a legally separate organization, raised $4.2 million in the 2002 election cycle, up

from $3.1 million in 2000.

Small, returning donors form the lifeblood of the organization, Boyd says. Boyd and

Blades have given roughly $50,000 of their own money to MoveOn. In addition, the San

Francisco Foundation Community Initiative Funds has funneled some of its funding from

the Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation to MoveOn. The Richard & Rhoda Goldman

Fund have lent financial support directly.

At least one campaign finance lawyer, Craig Engle, a specialist in political finance issues

at the law firm Arent, Fox, Kintner, Plotkin & Kahn and a former Republican Party

official, questions the legality of the funding MoveOn gets from the San Francisco

Foundation. As a 501©(4) organization, MoveOn can participate in most types of

political and lobbying activities, Engle says. But 501©(3) organizations such as

MoveOn’s foundation donors are tax-exempt and barred from many types of political and

lobbying efforts, he adds. The rules governing tax-exempt groups forbid a 501©(3) from

getting around the restriction by simply handing off money to a 501©(4), he says.

Boyd responds that campaign finance law also allows a 501©(3) to allocate a portion of

its budget to grassroots funding. Further, he notes that Greg Colvin, who wrote a book on

legal requirements for 501©(3) and 501©(4) groups, represents MoveOn and structured

the funding arrangement between the two organizations. Boyd estimates that the San

Francisco Foundation’s charitable lobbying allocations were about $100,000 during the

past fiscal year.

Even as it continues to raise funds, MoveOn.org must deal with whether it will continue

to expand its influence. While it has marshaled activists to stop a range of policies,

MoveOn has not become as adept at pushing affirmative solutions.

And because MoveOn has a small staff, some organizational details are left to rank-and-

file members, without close oversight from headquarters. In one case this summer,

MoveOn’s site hosted an issues backgrounder about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a

topic on which MoveOn doesn’t focus much attention. Jewish activists complained that

the page was heavily tilted toward the pro-Palestinian viewpoint.

After “a good back-and-forth,” one activist says, MoveOn added an explanatory note and

a disclaimer to the page. The page, it turned out, had been posted by volunteers and had

not been thoroughly vetted. While those who disagreed with the page’s political slant

praise MoveOn’s subsequent responsiveness, the group’s reliance on large numbers of

scattered volunteers—for setting up in-person meetings with politicians, for instance—

places stewardship of the group’s name in the hands of unsalaried people who may not be

closely watched by top officials.

And while listening to its members is a strength, MoveOn may

be acting on too many fronts. In the past few months,

e-mails have been sent to members no t only on the recall in California, the Texas

redistricting battle, and President Bush’s $87 billion request for Iraq, but also to push the

White House to reveal who leaked the name of a CIA agent to columnist Robert Novak,

and to urge the firing of Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld.

In another recent instance, MoveOn asked its members to blitz the offices of House

Speaker Dennis Hastert, R-Ill., and Majority Leader Tom DeLay, R- Texas, with phone

calls protesting the FCC’s media-ownership rules. DeLay’s office struck back by

forwarding the calls to the cellphone of MoveOn’s campaign director. The folks at

MoveOn “risk losing their focus if they are involved in too many things,” said one expert

on politics and the Internet who is generally supportive of MoveOn’s efforts.

Exley acknowledges the risks, but he adds that the group’s current structure offers

benefits as well. “This kind of organizing lets you communicate with every single

participant,” Exley says. “In other organizations, you have a hierarchy with regional

leaders and local leaders. With MoveOn, everyone who goes into meetings has read the

same materials as the leaders have.”

MoveOn has no plans to change its structure, mission, or overhead in any significant

way—except for the continued growth of its e- mail list. Republican Web expert Purpuro

compares MoveOn to the fast- multiplying coffee emporium from which Exley was able

to send out the California recall e- mail to a half- million people. “They’re probably like

Starbucks in 1992,” Purpuro says. “I don’t know if their growth rate will surpass what

they’ve done recently, but they still have plenty of terrain to cover.”

Staff Correspondent Bara Vaida contributed to this story.

You might also like

- MoveOn's 50 Ways to Love Your Country: How to Find Your Political Voice and Become a Catalyst for ChangeFrom EverandMoveOn's 50 Ways to Love Your Country: How to Find Your Political Voice and Become a Catalyst for ChangeRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (7)

- The Manipulators: Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Big Tech's War on ConservativesFrom EverandThe Manipulators: Facebook, Google, Twitter, and Big Tech's War on ConservativesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The AOC Way: The Secrets of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's SuccessFrom EverandThe AOC Way: The Secrets of Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez's SuccessRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- David W Moore Opinion MakersDocument217 pagesDavid W Moore Opinion MakersISSACG74No ratings yet

- Five To FourDocument28 pagesFive To FourThe Brennan Center for JusticeNo ratings yet

- The Financiers of Congressional Elections: Investors, Ideologues, and IntimatesFrom EverandThe Financiers of Congressional Elections: Investors, Ideologues, and IntimatesNo ratings yet

- Perry V Schwarzenegger - Vol-13-6-16-10Document164 pagesPerry V Schwarzenegger - Vol-13-6-16-10towleroadNo ratings yet

- Sfchron20903Document2 pagesSfchron20903politixNo ratings yet

- Political CampaigningDocument7 pagesPolitical CampaigningAustin MaplesNo ratings yet

- The Lie Detectives: In Search of a Playbook for Winning Elections in the Disinformation AgeFrom EverandThe Lie Detectives: In Search of a Playbook for Winning Elections in the Disinformation AgeNo ratings yet

- Chap 1Document17 pagesChap 1AnneSophie BoscNo ratings yet

- Participatory Culture and Politics Political Consumerism and Online Politics Civic Engagement ConclusionDocument8 pagesParticipatory Culture and Politics Political Consumerism and Online Politics Civic Engagement ConclusiongpnasdemsulselNo ratings yet

- Can Peer Pressure Defeat Trump?: in 2020, Democrats Need Millennials To Turn Out. Vote Shaming Apps Can HelpDocument6 pagesCan Peer Pressure Defeat Trump?: in 2020, Democrats Need Millennials To Turn Out. Vote Shaming Apps Can HelpfgsdfNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Related LiteratureDocument4 pagesChapter 2: Related LiteraturesjlayawenNo ratings yet

- Netroots Narrative: The Evolution of Liberal Candidates From 2004 To The Present by Diana Tracy CohenDocument28 pagesNetroots Narrative: The Evolution of Liberal Candidates From 2004 To The Present by Diana Tracy CohenMark PackNo ratings yet

- The Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionFrom EverandThe Voter’s Guide to Election Polls; Fifth EditionNo ratings yet

- Protest at The Center of American PoliticsDocument15 pagesProtest at The Center of American PoliticsJessica ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- XenosDocument23 pagesXenosapi-315322999No ratings yet

- Social Media in Elections: Echo Chamber or Crystal BallDocument33 pagesSocial Media in Elections: Echo Chamber or Crystal BallBrian LevinNo ratings yet

- Advocacy Group's Online Savvy Nets More Than DonationsDocument4 pagesAdvocacy Group's Online Savvy Nets More Than DonationspolitixNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: What Do We Know About Politics and Communication and How Do We Know It?Document20 pagesBook Reviews: What Do We Know About Politics and Communication and How Do We Know It?evasnenNo ratings yet

- Everyone Counts: Could "Participatory Budgeting" Change Democracy?From EverandEveryone Counts: Could "Participatory Budgeting" Change Democracy?Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Measuring America's Divide - It's Gotten Worse' - The New York TimesDocument5 pagesMeasuring America's Divide - It's Gotten Worse' - The New York TimesAudrey ShinNo ratings yet

- Barack Obama How Content Management and Web 2 0 Helped Win The White HouseDocument9 pagesBarack Obama How Content Management and Web 2 0 Helped Win The White HouseNishanth AshokNo ratings yet

- Summary: Obama Zombies: Review and Analysis of Jason Mattera's BookFrom EverandSummary: Obama Zombies: Review and Analysis of Jason Mattera's BookNo ratings yet

- CURS 1 - FB - Free Speech - 12 - Oct - 21Document4 pagesCURS 1 - FB - Free Speech - 12 - Oct - 21stefania bunilaNo ratings yet

- The Left's New MachineDocument11 pagesThe Left's New MachinenoahflowerNo ratings yet

- A.Dark MoneyDocument2 pagesA.Dark MoneyEileen HannaNo ratings yet

- Second Draft - Research PaperDocument14 pagesSecond Draft - Research Paperkhub819No ratings yet

- Final Paper For American DemocracyDocument6 pagesFinal Paper For American Democracyapi-549559353No ratings yet

- FINAL EXAM: HSS 653, Public Diplomacy, Fall 2015Document15 pagesFINAL EXAM: HSS 653, Public Diplomacy, Fall 2015WardhaNo ratings yet

- 01-12-09 Progressive-How To Push Obama by John NicholsDocument3 pages01-12-09 Progressive-How To Push Obama by John NicholsMark WelkieNo ratings yet

- Opinion - 3/23Document1 pageOpinion - 3/23lindsey_arynNo ratings yet

- Ranking The Mayoral Candidates - PensionsDocument1 pageRanking The Mayoral Candidates - PensionssaywhatuserNo ratings yet

- Through the Grapevine: Socially Transmitted Information and Distorted DemocracyFrom EverandThrough the Grapevine: Socially Transmitted Information and Distorted DemocracyNo ratings yet

- 2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveFrom Everand2016 Election and Beyond: What Did You Know? What You Need to Know: Educator’S PerspectiveNo ratings yet

- Bridging The Information Gap Legislative Member Organizations As Social Networks in The United States and The European Union (Coll.)Document164 pagesBridging The Information Gap Legislative Member Organizations As Social Networks in The United States and The European Union (Coll.)HikaruNo ratings yet

- Mad As Hell: How the Tea Party Movement Is Fundamentally Remaking Our Two-Party SystemFrom EverandMad As Hell: How the Tea Party Movement Is Fundamentally Remaking Our Two-Party SystemNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing ContentDocument21 pagesManufacturing ContentDel FidelityNo ratings yet

- The Vanishing Voting Booth Citizens United The Wholesale Purchase of The Presidential ElectionsDocument56 pagesThe Vanishing Voting Booth Citizens United The Wholesale Purchase of The Presidential ElectionsAnthony TurnerNo ratings yet

- Framing the Future: How Progressive Values Can Win Elections and Influence PeopleFrom EverandFraming the Future: How Progressive Values Can Win Elections and Influence PeopleNo ratings yet

- Tea Time?: The Rise of The Tea PartyDocument4 pagesTea Time?: The Rise of The Tea PartyMarcelo Alves Dos Santos JuniorNo ratings yet

- Taking Down The Tea Party Ten: Stopping Juvenile DetentionDocument8 pagesTaking Down The Tea Party Ten: Stopping Juvenile DetentionMatthew VadumNo ratings yet

- Wall Street's War On Workers Chapter 5: The Use and Abuse of PopulismDocument10 pagesWall Street's War On Workers Chapter 5: The Use and Abuse of PopulismChelsea Green PublishingNo ratings yet

- Con Job: How Democrats Gave Us Crime, Sanctuary Cities, Abortion Profiteering, and Racial DivisionFrom EverandCon Job: How Democrats Gave Us Crime, Sanctuary Cities, Abortion Profiteering, and Racial DivisionRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- DNC Rolls Out The Democratic Women's Alliance at Women's Leadership ForumDocument5 pagesDNC Rolls Out The Democratic Women's Alliance at Women's Leadership ForumMeghan HollowayNo ratings yet

- Sample Research Paper For Intro To Politics and Policy Studies - SMUDocument11 pagesSample Research Paper For Intro To Politics and Policy Studies - SMUEira ShahNo ratings yet

- David Shor's Unified Theory of The 2020 ElectionDocument19 pagesDavid Shor's Unified Theory of The 2020 ElectionShayok SenguptaNo ratings yet

- The Myth of Voter Suppression: The Left's Assault on Clean ElectionsFrom EverandThe Myth of Voter Suppression: The Left's Assault on Clean ElectionsNo ratings yet

- Putting People Back in Politics: The Revival of American DemocracyFrom EverandPutting People Back in Politics: The Revival of American DemocracyNo ratings yet

- The "Vast Left-Wing Conspiracy": George Soros's Democracy Alliance Remains A Potent Force in The 2014 ElectionsDocument12 pagesThe "Vast Left-Wing Conspiracy": George Soros's Democracy Alliance Remains A Potent Force in The 2014 ElectionsMatthew VadumNo ratings yet

- Obama Mobilizes Campaign Veterans To Push For Court Nominee - The New York TimesDocument6 pagesObama Mobilizes Campaign Veterans To Push For Court Nominee - The New York TimesadfjladjjkahdNo ratings yet

- Innovation, Infrastructure, and Organization in New Media CampaigningDocument30 pagesInnovation, Infrastructure, and Organization in New Media CampaigningAnthony AlesnaNo ratings yet

- Political Fandom in The Age of Social Media: Case Study of Barack Obama's 2008 Presidential CampaignDocument33 pagesPolitical Fandom in The Age of Social Media: Case Study of Barack Obama's 2008 Presidential Campaignstrongmarathon8157No ratings yet

- The Shadow Party: How George Soros, Hillary Clinton, and Sixties Radicals Seized Control of the Democratic PartyFrom EverandThe Shadow Party: How George Soros, Hillary Clinton, and Sixties Radicals Seized Control of the Democratic PartyNo ratings yet

- Fraud: How the Left Plans to Steal the Next ElectionFrom EverandFraud: How the Left Plans to Steal the Next ElectionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- How To Cover Electoral ConflictDocument10 pagesHow To Cover Electoral ConflictAnthony CaveNo ratings yet

- OMB Guidance Agency Use 3rd Party Websites AppsDocument9 pagesOMB Guidance Agency Use 3rd Party Websites AppsAlex HowardNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Inquiry Into The Matter of Senator John EnsignDocument75 pagesPreliminary Inquiry Into The Matter of Senator John EnsignpolitixNo ratings yet

- ElenaKagan PublicQuestionnaireDocument202 pagesElenaKagan PublicQuestionnairefrajam79No ratings yet

- Volume 10 Pages 2331 - 2583 UNITEDDocument254 pagesVolume 10 Pages 2331 - 2583 UNITEDG-A-YNo ratings yet

- Symbolic ObamaCare "Repeal" Bill by Rep. Steve King (R-IA)Document1 pageSymbolic ObamaCare "Repeal" Bill by Rep. Steve King (R-IA)politixNo ratings yet

- Republican PrezDocument72 pagesRepublican PrezZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- America's Healthy Future Act of 2009Document223 pagesAmerica's Healthy Future Act of 2009KFFHealthNewsNo ratings yet

- DOJ Memorandum: Status of Certain OLC Opinions Issued in The Aftermath of The Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001Document11 pagesDOJ Memorandum: Status of Certain OLC Opinions Issued in The Aftermath of The Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001politix100% (10)

- The Electoral College: How It WorksDocument15 pagesThe Electoral College: How It Workspolitix100% (7)

- Blagojevich ComplaintDocument78 pagesBlagojevich ComplaintWashington Post Investigations100% (56)

- 1 in The United States District Court For The District of MarylandDocument57 pages1 in The United States District Court For The District of Marylandpolitix100% (3)

- Webcast Feedback Form 071907Document1 pageWebcast Feedback Form 071907politixNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff,: in The United States District Court For The Southern District of Alabama Northern Division Bethany KarrDocument16 pagesPlaintiff,: in The United States District Court For The Southern District of Alabama Northern Division Bethany Karrpolitix100% (1)

- Form AJDocument6 pagesForm AJkatacumiNo ratings yet

- Uganda Constitution Ch4Document14 pagesUganda Constitution Ch4jadwongscribdNo ratings yet

- Drafting Pleading (Statement of Claim)Document8 pagesDrafting Pleading (Statement of Claim)Fatin Abd WahabNo ratings yet

- International Financial Management Chapter 3Document14 pagesInternational Financial Management Chapter 31954032027cucNo ratings yet

- TD Esc 02 de en 15 033 Rev000 Work Schedule Grid Connection E 101Document14 pagesTD Esc 02 de en 15 033 Rev000 Work Schedule Grid Connection E 101Felipe SilvaNo ratings yet

- Crystal Vs BpiDocument2 pagesCrystal Vs BpiTricia SandovalNo ratings yet

- The Personal Side of PolicingDocument2 pagesThe Personal Side of Policingsamilyrodriguez606060No ratings yet

- Descriptions of Ike and FranklinDocument1 pageDescriptions of Ike and FranklinPeace BridgesNo ratings yet

- Intention To Create Legal RelationsDocument4 pagesIntention To Create Legal Relationsماتو اریکاNo ratings yet

- High Current MOSFET Driver: FeaturesDocument16 pagesHigh Current MOSFET Driver: FeaturesmilivojNo ratings yet

- Application Under Order 39 Rule 1 &2 CPC Read With Sec 151 CPCDocument2 pagesApplication Under Order 39 Rule 1 &2 CPC Read With Sec 151 CPCMasood Bhatti100% (1)

- Boy Scouts of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesBoy Scouts of The PhilippinesJames PerezNo ratings yet

- Migration Certificate Application Form OLD PDFDocument2 pagesMigration Certificate Application Form OLD PDFtinkusk24No ratings yet

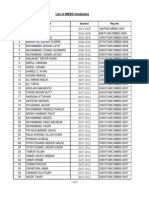

- List of MBBS Graduates StudentsDocument3 pagesList of MBBS Graduates StudentsAmjadNaseemNo ratings yet

- Friday Bulletin 689Document8 pagesFriday Bulletin 689Jamia MosqueNo ratings yet

- Essential Requisites of Contracts: Classes of Elements of ContractDocument8 pagesEssential Requisites of Contracts: Classes of Elements of ContractLimuel MacasaetNo ratings yet

- Partnership Formation ProblemsDocument3 pagesPartnership Formation Problemsai kawaiiNo ratings yet

- Tax II Part 2.1Document3 pagesTax II Part 2.1Gillian Caye Geniza BrionesNo ratings yet

- ) Daily Times - Site Edition (Printer Friendly Version)Document6 pages) Daily Times - Site Edition (Printer Friendly Version)Rameez_AhmedNo ratings yet

- Lesson 08 WorshipDocument7 pagesLesson 08 Worshipm28181920No ratings yet

- Basic CaseletsDocument3 pagesBasic CaseletsErika delos Santos0% (1)

- Explain Ethics Auditing and Explain The Different Steps in The Ethics Auditing ProcessDocument3 pagesExplain Ethics Auditing and Explain The Different Steps in The Ethics Auditing ProcessWaqar KhalidNo ratings yet

- 77 Phil 636 People V DinglasanDocument6 pages77 Phil 636 People V Dinglasanj guevarraNo ratings yet

- 44 MarceloDocument11 pages44 MarceloMyrna B RoqueNo ratings yet

- Iso Iec 10021-8-1999Document50 pagesIso Iec 10021-8-1999gamingfloppa055No ratings yet

- New YTVA BrochureDocument2 pagesNew YTVA BrochureYocheved HartmanNo ratings yet

- Society Against Human FreedomDocument15 pagesSociety Against Human FreedomArbizonNo ratings yet

- VSLA Linkage With MFDocument46 pagesVSLA Linkage With MFSamuel Dawit RimaNo ratings yet

- Presentation On EOUDocument24 pagesPresentation On EOUManish Kumar100% (1)

- CLAT 2013 PG Provisional ListDocument13 pagesCLAT 2013 PG Provisional ListBar & BenchNo ratings yet