Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inject Able S

Inject Able S

Uploaded by

quirinalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inject Able S

Inject Able S

Uploaded by

quirinalCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Article

New frontiers in urethral reconstruction: injectables and

alternative grafts

Alex J. Vanni

Department of Urology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Burlington, MA, USA

Correspondence to: Alex J. Vanni, MD. Department of Urology, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, 41 Mall Rd, Burlington, MA 01805, USA.

Email: Alex.J.Vanni@lahey.org.

Abstract: Contemporary management of anterior urethral strictures requires both endoscopic as well as

complex substitution urethroplasty, depending on the nature of the urethral stricture. Recent clinical and

experimental studies have explored the possibility of augmenting traditional endoscopic urethral stricture

management with anti-fibrotic injectable medications. Additionally, although buccal mucosa remains

the gold standard graft for substitution urethroplasty, alternative grafts are necessary for reconstructing

particularly complex urethral strictures in which there is insufficient buccal mucosa or in cases where it may

be contraindicated. This review summarizes the data of the most promising injectable adjuncts to endoscopic

stricture management and explores the alternative grafts available for reconstructing the most challenging

urethral strictures. Further research is needed to define which injectable medications and alternative grafts

may be best suited for urethral reconstruction in the future.

Keywords: Urethroplasty; lingual graft; skin graft; colonic graft; anti-fibrotic agent; alternative graft; tissueengineered graft

Submitted Oct 16, 2014. Accepted for publication Jan 19, 2015.

doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.01.09

View this article at: http://dx.doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.01.09

Introduction

The management of urethral strictures is varied and

includes both endoscopic and open urethral reconstruction,

with the goal of improving urinary flow. Urethral

strictures resulting from trauma, iatrogenic injury, prior

hypospadias surgery, lichen sclerosis and previous urethral

reconstruction often result in long segments of urethra that

require extensive reconstruction. The optimal management

of a urethral stricture is dependent on a multitude of factors

including the location, length, and etiology of stricture,

as well as the surgeons experience and reconstructive

preference. Urethral strictures are often managed in a

progressive manner in which shorter strictures are managed

endoscopically or with excision and anastomosis, while

augmentation with oral mucosa grafts or fasciocutaneous

flaps are necessary for longer defects.

While the buccal mucosa graft is the workhorse of

urethral reconstruction, a need exists for alternative grafts

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

for augmentation urethroplasty in patients in whom

obtaining adequate graft material is difficult; namely long

segment, panurethral strictures or recurrent strictures in

patients who have had prior buccal mucosa graft retrieval.

Buccal mucosa is now used so frequently, and with such high

success, that many of the grafts we used in the past (genital

and extragenital skin), are a great source to re-examine in

the future. Additionally, tissue engineering and regenerative

medicine offers the potential to significantly reduce the

invasiveness and morbidity of urethral reconstruction by

having off the shelf material available, with the goal of

improving patient outcomes.

Injectables

The goal of treating any urethral stricture is to provide

a durable, patent urethra with minimal morbidity. While

open urethroplasty is the gold standard treatment for

anterior urethral strictures, endoscopic management does

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

Translational Andrology and Urology, Vol 4, No 1 February 2015

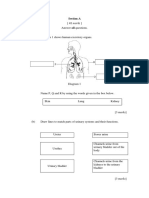

Figure 1 Ureteral stricture.

Figure 2 Direct vision internal urethrotomy (DVIU).

Figure 3 Injection of MMC. MMC, mitomycin C.

have a role in highly select patients. Since the outcomes of

endoscopic treatment are vastly inferior to urethroplasty,

improving our current endoscopic treatments is important,

and if successful, has the potential to greatly reduce

patient morbidity. There have been a number of different

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

85

techniques and anti-fibrotic agents used in the hope of

blunting wound contraction and scar formation.

The optimal therapeutic intervention is to augment a

traditional urethrotomy with an antiproliferative, antiscar forming agent (Figures 1-3). Steroids (triamcinolone),

mitomycin C (MMC), and hyaluronidase are all antifibrotic

agents that have the potential to reduce stricture recurrence.

Steroids have well known anti-fibrotic and anti-collagen

properties. MMC has been shown in both in vitro and

animal studies to inhibit fibroblast proliferation, collagen

deposition, and scar formation (1-3). Additionally, MMC

has been used in numerous medical specialties for its antiscar properties. It is used for glaucoma and pterygium

excision, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, laryngeal and

tracheal stenosis, and vaginal and anal stenosis (4-12).

Hyaluronidase is an antifibrotic agent used in hypertrophic

scar, keloid, and pulmonary fibrosis. This agent suppresses

wound healing inflammatory mediators, decreases fibroblast

proliferation, and decreases collagen and glycosaminoglycan

synthesis (13).

The current urologic literature demonstrates few

high quality studies investigating the use of antifibrotic

injectables for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures.

Triamcinolone is the agent that has been studied the

most extensively, with original reports going back to

the 1960s and 1970s (14,15). Steroid injection following

urethrotomy has been advocated in a number of small

studies to be safe and efficacious (16,17). There has been

two small randomized, controlled trials looking at bulbar

strictures <1.5 cm treated with urethrotomy with and

without triamcinolone (16,18). With a mean follow-up of

13.7 months (range, 1-25 months), Mazdak et al. found

the triamcinolone group had a stricture recurrence rate of

21.7% as compared to 50% in the control arm. In contrast,

the study by Tavakkoli et al. did not find a statistically

significant difference in the rate of stricture recurrence (16).

MMC is another antifibrotic agent that has recently

been studied. A small randomized, controlled trial of 40

patients with bulbar urethral strictures <1.5 cm was the

first study looking at the effects of MMC on urethrotomy.

Stricture recurrence was 10% in patients with urethrotomy

and MMC versus 50% with urethrotomy alone. However,

these results are to be taken with caution, as the follow-up

was only 6-24 months and the end point for success poorly

defined (19).

Hyaluronic acid and caroboxymethylcellulose have been

proposed to minimize stricture recurrence in one small

randomized controlled trial, but no conclusions about the

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

86

efficacy of this drug can be made as the trial only had a

6 month follow-up (20).

Lastly, the combination of all three of these drugs

has recently been proposed as a means of improving

urethrotomy outcomes. In a study of 103 patients with

strictures of both the bulbar and penile urethra, the authors

performed an urethrotomy and injected a mixture of 40 mg

triamcinolone, 2 mg MMC, and 3,000 units of hyaluronic

acid into the urethrotomy site (21). They report a stricture

recurrence rate of 19.4% at a median follow-up of 14 months

(range, 3-18 months), with no control group (21).

While all of these studies are an important step in

progressing the science and knowledge of endoscopic

stricture management, longer follow-up and more rigid

outcomes measures will be critical to properly evaluate

the role these adjuncts play with regards to traditional

treatment. Well-controlled clinical trials with a minimum

2-year follow-up are needed to determine the optimal

antifibrotic agent and technical approach for these novel

adjuncts to endoscopic management.

Alternative grafts

While the success rate of both grafts and penile skin flaps

has been established in the literature to be of similar

efficacy, there is also significantly higher morbidity

associated with the use of such flaps (22,23). The increased

complexity in harvesting penile skin flaps requires technical

expertise and has resulted in the use of full thickness grafts

as the augmentation tissue of choice among reconstructive

surgeons. There are a number of alternative grafts that

can be effectively implemented into the reconstructive

urologists armamentarium for use in particularly complex

cases, when there is insufficient buccal mucosa available

for augmentation urethroplasty. Lingual grafts, penile

and extragenital skin, bladder epithelium, small intestinal

submucosa, colonic mucosa, and tissue engineered

grafts are all existing potential sources of graft material

for patients needing additional tissue for augmentation

urethroplasty.

Lingual grafts

Oral mucosa grafts are the standard grafting material for

augmentation urethroplasty as they are accustomed to

being wet, and may be resistant to lichen sclerosis (24,25).

While there is little data regarding lingual mucosa grafts,

the characteristics that make buccal mucosa appealing apply

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

Vanni. New frontiers in urethral reconstruction

to lingual mucosa grafts as well. These full thickness grafts

have a thick epithelium, thin lamina propria, and rich,

panlaminar vascular plexus, which allows excellent graft take

with minimal contracture. The macroscopic architecture of

these grafts is identical to buccal mucosa, making this the

graft of choice when additional material is needed (26).

There are notable advantages to harvesting lingual grafts.

They are readily available for harvest, have a concealed

donor site scar, and can yield two grafts ranging between 7

and 16 cm in length. During graft harvesting, care is taken

to dissect between the mucosa and submucosal fat. Both

Whartons duct and the lingual nerve are identified, and

care is taken to avoid harvesting mucosa from the floor of

the mouth to maintain tongue mobility (27). Lingual grafts

can be harvested from any of three locations on the tongue,

the lateral surface, ventral surface, or both the ventral

and lateral surface (26-28). Harvesting from the ventral

location allows the potential for two grafts to be harvested

if necessary. After graft harvest, the donor site is closed with

absorbable suture and the graft prepared by removing the

underlying fibrovascular tissue.

The urethroplasty techniques used with lingual mucosa

grafts are similar to buccal grafts, with published reports

of one-stage dorsal onlay, dorsal inlay, ventral onlay grafts,

as well as a two-stage approach. The short-term outcomes

of lingual mucosa grafts appear to be equivalent to buccal

mucosa, although there are only a few published reports

in the literature (26,27,29,30). Sharma et al. performed

a prospective comparative analysis of lingual mucosa

grafts compared to buccal mucosa grafts in 30 patients

who underwent a dorsal onlay urethroplasty (31). The

stricture free outcomes were similar at a mean follow-up of

14.5 months. Additionally, there have been a few additional

small studies demonstrating success rates of 79-90% with

lingual grafts. However the stricture etiology and surgical

techniques were heterogeneous in these small studies and

follow-up was less than 2 years (26-30). Lingual mucosa

grafts are an excellent graft material for patients with long

strictures due to lichen sclerosis, when there may be an

inadequate amount of buccal mucosa available. Das et al.

was the first to describe short-term results in 18 patients

with lichen sclerosis, and demonstrated an 83.3% success

rate in patients with a mean stricture length of 10.2 cm (29).

Similarly, Xu et al. described their experience with onestage lingual mucosa grafts in 22 patients with lichen

sclerosis strictures and demonstrated an 88.9% success rate

(mean stricture length 12.5 cm) with a mean follow-up of

38.7 months (32).

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

Translational Andrology and Urology, Vol 4, No 1 February 2015

87

One of the important factors needing validation is the

donor site morbidity associated with lingual mucosa harvest.

It appears from the small number of studies published,

that complications are rare. Initial reports by Simonato et al.

reported that patients only complained of slight donor

sight pain for 1-2 days, while Das et al. found minimal

complications with no functional or esthetic deficiency

(29,33). Kumar et al. found that all patients were pain free

by 6 days, while in patients with bilateral tongue harvest,

they temporarily had a higher rate of slurred speech (34).

Sharma et al. published donor site morbidity with longterm changes in speech in patients who underwent bilateral

lingual harvest for strictures >7 cm (31).

Lingual grafts represent an excellent choice as an

alternative graft to buccal mucosa in patients requiring

long-segment substitution urethroplasty, in patients who

have previously had buccal mucosa harvest, or in patients in

whom cheek harvest would otherwise be contraindicated.

While lingual grafts share all the important characteristics

of buccal mucosa, the long-term outcomes of lingual

grafts have not been established, as the longest followup published to date is 38.7 months. Additionally, while

harvesting lingual grafts appears safe, the optimal graft

size and location on the tongue has not been established to

minimize potential long-term morbidity.

term durability of penile skin grafts could not be assessed in

this analysis, as the follow-up was only 64 months. However,

a recent publication by Barbagli et al. demonstrated the

long-term outcomes of 359 patients who had either an oral

mucosa or penile skin graft urethroplasty. With a minimum

follow-up of 6 years, patients with penile skin grafts had

a success rate of 59.7% as compared to 77.7% of patients

with an oral mucosa graft (39).

Postauricular skin is a full thickness graft that can be

used for the treatment of anterior urethral strictures when

oral mucosa and genital skin are not available. The skin is

harvested from the lower half of the mastoid, and should

not cross beyond the lower end of the tragus. Manoj et al.

has demonstrated the ability to harvest 7-8 cm of fullthickness graft per side, allowing 14-16 cm of graft material

if necessary. In 35 patients with a follow-up of 21 months,

they demonstrated an 89% success rate, and reported

no donor site complications (40). If harvesting this graft,

consideration of the donor site scar should be taken into

consideration.

Abdominal skin is another full-thickness skin graft

alternative to postauricular skin. This graft should be taken

from a hairless area in either the flank or right or left lower

quadrant, near the level of the anterior iliac spine. The

donor site is closed and the graft prepared by removing

all the areolar tissue. The indications for use are similar to

postauricular grafts, namely patients without lichen sclerosis

in whom oral mucosa and genital skin are not available.

A potential use of full thickness skin was described Chen

et al. who used a combination of full-thickness skin grafts

dorsally in combination with ventral buccal mucosa graft

for long segment strictures and reported a 100% success

rate in patients with strictures >6 cm with the double graft

technique (41). Further evaluation and longer follow-up will

be needed to confirm the preliminary findings of this study.

Another extragenital skin graft option for the treatment

of particularly complex, long strictures with severe

spongiofibrosis is the use of a meshed split-thickness skin

graft. Popularized by Schreiter, these grafts are used in

a two-stage approach (42). In expert hands, these grafts

perform exceedingly well in the most complex of cases,

with a 79% success rate at 6.5 years follow-up (43). The

overall complication rate with a two stage meshed graft

urethroplasty is low, with erectile dysfunction and penile

curvature rates reported to occur in 4% and 9% of patients

respectively (44). While these grafts were used before the

modern era of buccal mucosa, they currently represent a

tiny fraction of urethroplasties performed. However, the

Genital and extragenital skin

While skin grafts are certainly not a New frontier in

urethral reconstruction, there is an important use in

modern urethral reconstruction for these grafts in patients

without lichen sclerosis. Substitution urethroplasty with a

penile skin graft was first described in 1953 by Presman and

Greenfield, and was ultimately promoted by Devine and

Horton using preputial skin for hypospadias repairs (35-37).

Although the use of penile and extragenital skin grafts has

been declining since early 1990s, the use of full thickness

skin grafts remains an integral part of the reconstructive

urologists armamentarium. Certain conditions exist which

ideally suit the harvest of skin (oral leukoplakia, heavy

tobacco use, chewing tobacco, betel nut or pan masala,

previous oral radiotherapy, previous oral mucosa grafting,

insufficient oral mucosa) for substitution urethroplasty.

Penile skin grafts are hairless, elastic, and easy to harvest

with minimal donor site morbidity. A recent meta-analysis

be Lumen et al. comparing urethral reconstruction with

either a penile skin or buccal mucosa demonstrated a success

rate of 81.8% vs. 85.9% respectively, P=0.01 (38). The long-

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

88

Vanni. New frontiers in urethral reconstruction

Figure 6 TEMS setup. TEMS, transanal endoscopic micro-surgical

technique.

Figure 4 Recurrent lichen sclerosis in previous 1 st stage buccal

mucosa graft.

used primarily in the setting of hypospadias surgery. This

graft has fallen out of favor both because of the invasive

nature of harvest required to obtain the graft, as well as

the high rate of stricture recurrence. In particular, meatal

problems occur in up to 68% of patients when the graft was

exposed to air, and up to 66% of patients required multiple

operations to achieve a good result (45).

Colonic mucosa

Figure 5 TEMS instruments. TEMS, transanal endoscopic microsurgical technique.

mesh graft technique is a useful alternative for the most

complex urethral stricture.

Bladder mucosa

Bladder mucosa is a free graft that is available and has been

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

While Mundy et al. has described the successful use of

intestinal flaps as a salvage procedure for bulbomembranous

urethral strictures, colonic mucosa has also been used

as a circumferential graft in patients with long segment

urethral strictures (46,47). Xu et al. reported an 85.7%

success rate in 36 patients with a follow-up of 53.6 months

(mean stricture length 15.1 cm). However, these patients

all underwent a sigmoid resection in order to obtain the graft,

raising questions about the practicality of such a technique (47).

We have found that retrieving colonic mucosa for salvage

urethroplasty is possible without a bowel resection with a

transanal endoscopic micro-surgical technique (TEMS)

(Figures 4-8). The TEMS technique was developed by

colorectal surgeons for the minimally invasive treatment

of early stage rectal tumors and benign polyps high in the

rectum (up to 20 cm). We have successfully performed this

technique safely in four patients for salvage urethroplasty,

with no perioperative complications (Vanni and Zinman

unpublished data). At a mean follow-up 13 months (range,

5-19 months), three of the four patients have had a

successful outcome, while one patient has required a

urethral dilation for recurrent stricture. All four patients

have normal bowel function. However, larger patient

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

Translational Andrology and Urology, Vol 4, No 1 February 2015

Figure 7 Colonic mucosa grafts prior to preparation.

89

urethras (51). Additionally, synthetic scaffolds have been

studied as an off the shelf alternative to human or animal

collagen scaffolds. In a study by Raya-Rivera et al., five boys

had muscle and epithelial cells seeded onto tubularized

polyglycolic acid:poly (lactide-co-glycolide acid) scaffolds.

Patients then underwent urethral reconstruction of the

tubularized urethras. At a median follow-up of 71 months,

all patients had a patent urethra (52).

Although there has been a tremendous amount of basic

science and animal research for tissue engineered grafts,

few platforms have advanced to human clinical trial.

The problem for any graft in treating a complex urethral

stricture is related to the issues of ischemia, fibrosis, and

wound contracture. Further study is needed to better

elucidate the optimal scaffolds and cell sources to overcome

the inherent issues of tissue fibrosis associated with complex

urethral strictures.

Conclusions

Figure 8 Ventral colonic graft onlay.

numbers and long-term follow-up will be important in

determining what, if any, role colonic mucosa has in salvage

urethroplasty.

Acellular matrix/tissue engineering

There is great promise in the field of tissue engineering

for the development of an off the shelf graft suitable for

urethral reconstruction. While oral mucosa grafts are

readily available and adequate for the vast majority of

strictures, alternative grafts are needed in the most complex

cases. Small intestinal submucosa is a prefabricated,

acellular, collagen matrix manufactured from porcine

intestinal submucosa. Initial, short-term results in two

pilot studies demonstrated success rates between 90-100%

(48,49). However, at longer follow-up in 25 patients, success

was 86% for strictures <4 cm, while in strictures >4 cm no

patient had a successful reconstruction (50). Much research

has been performed trying to identify the best scaffold and

cell for replacing strictures of the urethra. Autologous tissue

engineered buccal mucosa is a promising substitute, and in

a pilot study of five patients, all had an initial good result,

and at 3 years follow-up, three of the patients had patent

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

Anti-fibrotic injectables are an intriguing attempt at

improving endoscopic stricture management. While

preliminary data is encouraging, more rigid outcomes

measures will be critical to properly evaluate the role these

adjuncts play with regards to traditional treatment. Wellcontrolled clinical trials with long-term follow-up are

needed to determine the optimal antifibrotic drug and

technical approach for these novel agents.

Urethral reconstruction continues to be an evolving

specialty due to the uniform difficulty in treating complex

urethral strictures. The reconstructive urologist needs to be

comfortable with a number of grafts in order to best treat

each individual patients condition. Tissue engineered grafts

continue to show promise, but further study is needed to

improve upon existing platforms.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The author has no conflicts of interest to

declare.

References

1. Simman R, Alani H, Williams F. Effect of mitomycin C

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

90

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

Vanni. New frontiers in urethral reconstruction

on keloid fibroblasts: an in vitro study. Ann Plast Surg

2003;50:71-6.

Ferguson B, Gray SD, Thibeault S. Time and dose effects

of mitomycin C on extracellular matrix fibroblasts and

proteins. Laryngoscope 2005;115:110-5.

Ayyildiz A, Nuhoglu B, Glerkaya B, et al. Effect of

intraurethral Mitomycin-C on healing and fibrosis in rats

with experimentally induced urethral stricture. Int J Urol

2004;11:1122-6.

Ubell ML, Ettema SL, Toohill RJ, et al. Mitomycin-c

application in airway stenosis surgery: analysis of safety

and costs. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2006;134:403-6.

Smith ME, Elstad M. Mitomycin C and the endoscopic

treatment of laryngotracheal stenosis: are two applications

better than one? Laryngoscope 2009;119:272-83.

Simpson CB, James JC. The efficacy of mitomycin-C in

the treatment of laryngotracheal stenosis. Laryngoscope

2006;116:1923-5.

Reibaldi A, Uva MG, Longo A. Nine-year follow-up of

trabeculectomy with or without low-dosage mitomycin-c

in primary open-angle glaucoma. Br J Ophthalmol

2008;92:1666-70.

Murakami M, Mori S, Kunitomo N. Studies on the

pterygium. V. Follow-up information of mitomycin C

treatment. Nihon Ganka Gakkai Zasshi 1967;71:351-8.

Mueller CM, Beaunoyer M, St-Vil D. Topical

mitomycin-C for the treatment of anal stricture. J Pediatr

Surg 2010;45:241-4.

Dolmetsch AM. Nonlaser endoscopic endonasal

dacryocystorhinostomy with adjunctive mitomycin C in

nasolacrimal duct obstruction in adults. Ophthalmology

2010;117:1037-40.

Bindlish R, Condon GP, Schlosser JD, et al. Efficacy

and safety of mitomycin-C in primary trabeculectomy:

five-year follow-up. Ophthalmology 2002;109:1336-41;

discussion 1341-2.

Betalli P, De Corti F, Minucci D, et al. Successful topical

treatment with mitomycin-C in a female with postbrachytherapy vaginal stricture. Pediatr Blood Cancer

2008;51:550-2.

Wolfram D, Tzankov A, Plzl P, et al. Hypertrophic

scars and keloids--a review of their pathophysiology, risk

factors, and therapeutic management. Dermatol Surg

2009;35:171-81.

Poynter JH, Levy J. Balanitis xerotica obliterans: effective

treatment with topical and sublesional corticosteroids. Br J

Urol 1967;39:420-5.

Hebert PW. The treatment of urethral stricture:

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

transurethral injection of triamcinolone. J Urol

1972;108:745-7.

Tavakkoli Tabassi K, Yarmohamadi A, Mohammadi S.

Triamcinolone injection following internal urethrotomy

for treatment of urethral stricture. Urol J 2011;8:132-6.

Kumar S, Kapoor A, Ganesamoni R, et al. Efficacy

of holmium laser urethrotomy in combination with

intralesional triamcinolone in the treatment of anterior

urethral stricture. Korean J Urol 2012;53:614-8.

Mazdak H, Izadpanahi MH, Ghalamkari A, et al. Internal

urethrotomy and intraurethral submucosal injection of

triamcinolone in short bulbar urethral strictures. Int Urol

Nephrol 2010;42:565-8.

Mazdak H, Meshki I, Ghassami F. Effect of mitomycin

C on anterior urethral stricture recurrence after internal

urethrotomy. Eur Urol 2007;51:1089-92; discussion 1092.

Chung JH, Kang DH, Choi HY, et al. The effects of

hyaluronic acid and carboxymethylcellulose in preventing

recurrence of urethral stricture after endoscopic internal

urethrotomy: a multicenter, randomized controlled, singleblinded study. J Endourol 2013;27:756-62.

Kumar S, Garg N, Singh SK, et al. Efficacy of Optical

Internal Urethrotomy and Intralesional Injection

of Vatsala-Santosh PGI Tri-Inject (Triamcinolone,

Mitomycin C, and Hyaluronidase) in the Treatment of

Anterior Urethral Stricture. Adv Urol 2014;2014:192710.

Wessells H, McAninch JW. Current controversies in

anterior urethral stricture repair: free-graft versus pedicled

skin-flap reconstruction. World J Urol 1998;16:175-80.

Dubey D, Vijjan V, Kapoor R, et al. Dorsal onlay buccal

mucosa versus penile skin flap urethroplasty for anterior

urethral strictures: results from a randomized prospective

trial. J Urol 2007;178:2466-9.

Palminteri E, Brandes SB, Djordjevic M. Urethral

reconstruction in lichen sclerosus. Curr Opin Urol

2012;22:478-83.

Dubey D, Sehgal A, Srivastava A, et al. Buccal mucosal

urethroplasty for balanitis xerotica obliterans related

urethral strictures: the outcome of 1 and 2-stage

techniques. J Urol 2005;173:463-6.

Simonato A, Gregori A, Ambruosi C, et al. Lingual

mucosal graft urethroplasty for anterior urethral

reconstruction. Eur Urol 2008;54:79-85.

Barbagli G, De Angelis M, Romano G, et al. The use

of lingual mucosal graft in adult anterior urethroplasty:

surgical steps and short-term outcome. Eur Urol

2008;54:671-6.

Xu YM, Fu Q, Sa YL, et al. Treatment of urethral

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

Translational Andrology and Urology, Vol 4, No 1 February 2015

91

strictures using lingual mucosas urethroplasty: experience

of 92 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2010;123:458-62.

Das SK, Kumar A, Sharma GK, et al. Lingual mucosal

graft urethroplasty for anterior urethral strictures. Urology

2009;73:105-8.

Sharma GK, Pandey A, Bansal H, et al. Dorsal onlay

lingual mucosal graft urethroplasty for urethral strictures

in women. BJU Int 2010;105:1309-12.

Sharma AK, Chandrashekar R, Keshavamurthy R, et

al. Lingual versus buccal mucosa graft urethroplasty for

anterior urethral stricture: a prospective comparative

analysis. Int J Urol 2013;20:1199-203.

Xu YM, Feng C, Sa YL, et al. Outcome of 1-stage

urethroplasty using oral mucosal grafts for the treatment of

urethral strictures associated with genital lichen sclerosus.

Urology 2014;83:232-6.

Simonato A, Gregori A. Oral complications after lingual

mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty. ANZ J Surg

2008;78:933-4.

Kumar A, Goyal NK, Das SK, et al. Oral complications

after lingual mucosal graft harvest for urethroplasty. ANZ

J Surg 2007;77:970-3.

Presman D, Greenfield DL. Reconstruction of the

perineal urethra with a free full-thickness skin graft from

the prepuce. J Urol 1953;69:677-80.

Devine PC, Horton CE, Devine CJ Sr, et al. Use of full

thickness skin grafts in repair of urethral strictures. J Urol

1963;90:67-71.

Devine CJ Jr, Horton CE. A one stage hypospadias repair.

J Urol 1961;85:166-72.

Lumen N, Oosterlinck W, Hoebeke P. Urethral

reconstruction using buccal mucosa or penile skin

grafts: systematic review and meta-analysis. Urol Int

2012;89:387-94.

Barbagli G, Kulkarni SB, Fossati N, et al. Long-term

followup and deterioration rate of anterior substitution

urethroplasty. J Urol 2014;192:808-13.

Manoj B, Sanjeev N, Pandurang PN, et al. Postauricular

skin as an alternative to oral mucosa for anterior onlay

graft urethroplasty: a preliminary experience in patients

with oral mucosa changes. Urology 2009;74:345-8.

Chen ML, Odom BD, Johnson LJ, et al. Combining

ventral buccal mucosal graft onlay and dorsal full thickness

skin graft inlay decreases failure rates in long bulbar

strictures (6 cm). Urology 2013;81:899-902.

Schreiter F, Noll F. Mesh graft urethroplasty using split

thickness skin graft or foreskin. J Urol 1989;142:1223-6.

Kessler TM, Schreiter F, Kralidis G, et al. Long-term

results of surgery for urethral stricture: a statistical

analysis. J Urol 2003;170:840-4.

Pfalzgraf D, Olianas R, Schreiter F, et al. Two-staged

urethroplasty: buccal mucosa and mesh graft techniques.

Aktuelle Urol 2010;41 Suppl 1:S5-9.

Kinkead TM, Borzi PA, Duffy PG, et al. Long-term

followup of bladder mucosa graft for male urethral

reconstruction. J Urol 1994;151:1056-8.

Mundy AR, Andrich DE. Entero-urethroplasty for the

salvage of bulbo-membranous stricture disease or trauma.

BJU Int 2010;105:1716-20.

Xu YM, Qiao Y, Sa YL, et al. Urethral reconstruction

using colonic mucosa graft for complex strictures. J Urol

2009;182:1040-3.

Fiala R, Vidlar A, Vrtal R, et al. Porcine small intestinal

submucosa graft for repair of anterior urethral strictures.

Eur Urol 2007;51:1702-8; discussion 1708.

Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Colombo F, et al. Small

intestinal submucosa (SIS) graft urethroplasty: short-term

results. Eur Urol 2007;51:1695-701; discussion 1701.

Palminteri E, Berdondini E, Fusco F, et al. Long-term

results of small intestinal submucosa graft in bulbar

urethral reconstruction. Urology 2012;79:695-701.

Bhargava S, Patterson JM, Inman RD, et al. Tissueengineered buccal mucosa urethroplasty-clinical outcomes.

Eur Urol 2008;53:1263-9.

Raya-Rivera A, Esquiliano DR, Yoo JJ, et al. Tissueengineered autologous urethras for patients who

need reconstruction: an observational study. Lancet

2011;377:1175-82.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

Cite this article as: Vanni AJ. New frontiers in urethral

reconstruction: injectables and alternative grafts. Transl Androl

Urol 2015;4(1):84-91. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.01.09

Translational Andrology and Urology. All rights reserved.

www.amepc.org/tau

Transl Androl Urol 2015;4(1):84-91

You might also like

- Atlas of Operative Procedures in Surgical OncologyFrom EverandAtlas of Operative Procedures in Surgical OncologyNo ratings yet

- Component SeparationDocument23 pagesComponent Separationismu100% (2)

- Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDocument20 pagesBenign Prostatic HyperplasiaMohammed AadeelNo ratings yet

- Managing The Bladder and Bowel in Spina BifidaDocument77 pagesManaging The Bladder and Bowel in Spina BifidaSeptinaAyuSamsiati100% (1)

- List of Hospitals/Diagnostic Centres Empanelled Under Cghs Delhi &Document29 pagesList of Hospitals/Diagnostic Centres Empanelled Under Cghs Delhi &Varun MehrotraNo ratings yet

- TOG Manchester RepairDocument6 pagesTOG Manchester RepairNalin AbeysingheNo ratings yet

- Proximal Hypospadias Repair With Bladder Mucosal Graft: Our 10 Years ExperienceDocument6 pagesProximal Hypospadias Repair With Bladder Mucosal Graft: Our 10 Years ExperienceLastri HillaryNo ratings yet

- Cutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseDocument6 pagesCutaneous Needle Aspirations in Liver DiseaseRhian BrimbleNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00464 019 06670 9Document17 pages10.1007@s00464 019 06670 9Francisco Javier MacíasNo ratings yet

- Omentum OverlayDocument10 pagesOmentum OverlayAlin MihetiuNo ratings yet

- CDN JU27-I4 13 FREE DrEltermanDocument7 pagesCDN JU27-I4 13 FREE DrEltermanMARIA RIZWANNo ratings yet

- Suzuki K 2020. 3-6 MesesDocument11 pagesSuzuki K 2020. 3-6 MesesMARIA ANTONIETA RODRIGUEZ GALECIONo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument5 pagesDownloadAnonymous nRufcMpvNNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Anterior Urethral Stricture DiseasesDocument9 pagesSurgical Treatment of Anterior Urethral Stricture DiseasesOmomomo781No ratings yet

- Prevention of Adhesions by Omentoplasty: An Incisional Hernia Model in RatsDocument5 pagesPrevention of Adhesions by Omentoplasty: An Incisional Hernia Model in RatsbogdanotiNo ratings yet

- ROOT COVERAGE WITH PERIOSTEUM PEDICLE GRAFT - A NOVEL APPROACH DR Vineet VinayakDocument3 pagesROOT COVERAGE WITH PERIOSTEUM PEDICLE GRAFT - A NOVEL APPROACH DR Vineet VinayakDr Vineet VinayakNo ratings yet

- Tau 06 03 510Document7 pagesTau 06 03 510Eko NoviantiNo ratings yet

- 3 PBDocument6 pages3 PBAulia Rizqi MulyaniNo ratings yet

- Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and GynaecologyDocument17 pagesBest Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecologymusyawarah melalaNo ratings yet

- Endosponge Treatment Anaspomotis LeakageDocument5 pagesEndosponge Treatment Anaspomotis LeakagepalfiataNo ratings yet

- Incisional HerniaDocument9 pagesIncisional HerniaAdelina Martinica0% (1)

- Annals of Surgical Innovation and Research: Emergency Treatment of Complicated Incisional Hernias: A Case StudyDocument5 pagesAnnals of Surgical Innovation and Research: Emergency Treatment of Complicated Incisional Hernias: A Case StudyMuhammad AbdurrohimNo ratings yet

- Management of Anastomotic Leaks After Esophagectomy and Gastric Pull-UpDocument9 pagesManagement of Anastomotic Leaks After Esophagectomy and Gastric Pull-UpSergio Sitta TarquiniNo ratings yet

- Delatorre 2020Document5 pagesDelatorre 2020Rizky AmaliahNo ratings yet

- Review StrikturDocument13 pagesReview StrikturFryda 'buona' YantiNo ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument5 pages1 PDFBangladesh Academy of SciencesNo ratings yet

- 05 Ijss Mar 21 Oa05 - 2021Document5 pages05 Ijss Mar 21 Oa05 - 2021LavanyaNo ratings yet

- Tunica Vaginalis Flap Reinforcement in Staged Hypospadias RepairDocument11 pagesTunica Vaginalis Flap Reinforcement in Staged Hypospadias RepairDrMadhu AdusumilliNo ratings yet

- Elkhoury 2015Document5 pagesElkhoury 2015mod_naiveNo ratings yet

- Open Versus Laparoscopic Mesh Repair of Ventral Hernias: A Prospective StudyDocument3 pagesOpen Versus Laparoscopic Mesh Repair of Ventral Hernias: A Prospective Study'Adil MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Ureteral ReconstructionDocument6 pagesUreteral ReconstructiongumNo ratings yet

- Use Only: Intracorporeal Hybrid Single Port Conventional Laparoscopic Appendectomy in ChildrenDocument4 pagesUse Only: Intracorporeal Hybrid Single Port Conventional Laparoscopic Appendectomy in ChildrenYelisa PatandiananNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Jamcollsurg 2020 02 031Document34 pages10 1016@j Jamcollsurg 2020 02 031Residentes Cirugia Udea 2016No ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Umbilical Hernia Repair Technique PapDocument6 pagesLaparoscopic Umbilical Hernia Repair Technique PapEremeev SpiridonNo ratings yet

- Types of Gingival GraftsDocument34 pagesTypes of Gingival GraftsAhmad KurukchiNo ratings yet

- 2014 172 0 Retroperitoneal and Retrograde Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy As A Standard Treatment in A Community Hospital 97 101 1Document5 pages2014 172 0 Retroperitoneal and Retrograde Total Laparoscopic Hysterectomy As A Standard Treatment in A Community Hospital 97 101 1Sarah MuharomahNo ratings yet

- Current Concepts of UrethroplastyDocument226 pagesCurrent Concepts of Urethroplastywasis0% (1)

- Surgical Approaches To Esophageal CancerDocument6 pagesSurgical Approaches To Esophageal CancerYacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- Editorial: Percutaneous Drainage of Liver Hydatid Cysts: Is Evidence Enough To Accept It As First Modality of Choice?Document3 pagesEditorial: Percutaneous Drainage of Liver Hydatid Cysts: Is Evidence Enough To Accept It As First Modality of Choice?David CerrónNo ratings yet

- Abstracts BookDocument186 pagesAbstracts BookGabriel Laurentiu CucuNo ratings yet

- THT Jaga IiDocument2 pagesTHT Jaga IiZakkyMaulanaRahmatNo ratings yet

- Congenital TEF - A Modified Technique of Anastomosis Using Pleural FlapDocument4 pagesCongenital TEF - A Modified Technique of Anastomosis Using Pleural FlapGunduz AgaNo ratings yet

- Desdiferenciacion Epitelial Qeratoquiste Marsupializacion 03Document6 pagesDesdiferenciacion Epitelial Qeratoquiste Marsupializacion 03Daniel BermeoNo ratings yet

- Flap Surgical Techniques For Incisional Hernia Recurrences. A Swine Experimental ModelDocument9 pagesFlap Surgical Techniques For Incisional Hernia Recurrences. A Swine Experimental ModelFlorina PopaNo ratings yet

- Encapsulamiento PancriaticoDocument15 pagesEncapsulamiento PancriaticoTaguis VelascoNo ratings yet

- Shifting Paradigms in Minimally Invasive SurgeryDocument13 pagesShifting Paradigms in Minimally Invasive Surgeryflorence suyiNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PlastiksDocument5 pagesJurnal PlastiksbdhNo ratings yet

- Modified Rives StoppaDocument8 pagesModified Rives StoppaAndrei SinNo ratings yet

- Small Nowel Emergency SurgeryDocument8 pagesSmall Nowel Emergency SurgerySurya Nirmala DewiNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of A Harvest Graft Substitute For Recession Coverage and Soft Tissue Volume Augmentation. A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument21 pagesEfficacy of A Harvest Graft Substitute For Recession Coverage and Soft Tissue Volume Augmentation. A Randomized Controlled TrialGabriela Lou GomezNo ratings yet

- 2016 Ovarian Mature Cystic TeratomDocument7 pages2016 Ovarian Mature Cystic Teratompaula rangelNo ratings yet

- 71 - EpisiotomyDocument6 pages71 - Episiotomyiker santiago castilloNo ratings yet

- Dis Colon Rectum - Endoscopic Mucosal Resection of Large Sessile Colorectal PolypsDocument10 pagesDis Colon Rectum - Endoscopic Mucosal Resection of Large Sessile Colorectal PolypsChargerNo ratings yet

- Surg Apprach EsophagectomyDocument3 pagesSurg Apprach EsophagectomyDumitru RadulescuNo ratings yet

- A New Facilitating Technique For Postpartum Hysterectomy at Full Dilatation: Cervical ClampDocument4 pagesA New Facilitating Technique For Postpartum Hysterectomy at Full Dilatation: Cervical ClampJani SheNo ratings yet

- Current Status in Female Urology and GynDocument6 pagesCurrent Status in Female Urology and GynConsultorio Ginecología y ObstetriciaNo ratings yet

- Colic Surgery Recent Upda - 2023 - Veterinary Clinics of North America EquineDocument14 pagesColic Surgery Recent Upda - 2023 - Veterinary Clinics of North America EquinediazsunshineNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Effectiveness of Collagen Membrane in The Management of Oro Antral FistulaCommunication A Clinical StudyDocument8 pagesEvaluation of The Effectiveness of Collagen Membrane in The Management of Oro Antral FistulaCommunication A Clinical StudyAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Transvaginal MorcellationDocument8 pagesTransvaginal Morcellationsanjayb1976gmailcomNo ratings yet

- Past, Present and Future of Surgical Meshes: A ReviewDocument2 pagesPast, Present and Future of Surgical Meshes: A ReviewEldonVinceIsidroNo ratings yet

- Repair of Bowel Perforation Endoscopic State of The ArtDocument6 pagesRepair of Bowel Perforation Endoscopic State of The ArtAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Retroperitoneal Tumors: Clinical ManagementFrom EverandRetroperitoneal Tumors: Clinical ManagementCheng-Hua LuoNo ratings yet

- Management of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondFrom EverandManagement of Peritoneal Metastases- Cytoreductive Surgery, HIPEC and BeyondAditi BhattNo ratings yet

- Measure PDFDocument9 pagesMeasure PDFquirinalNo ratings yet

- Kulkarni 2016 PDFDocument21 pagesKulkarni 2016 PDFquirinalNo ratings yet

- Uretrostomia AtlasDocument10 pagesUretrostomia AtlasquirinalNo ratings yet

- Neuro Oncol 2014Document9 pagesNeuro Oncol 2014quirinalNo ratings yet

- Form No. 10iDocument2 pagesForm No. 10iTempuserNo ratings yet

- Gabr, Taha, Lab 15, Period 4Document5 pagesGabr, Taha, Lab 15, Period 4TAHA GABRNo ratings yet

- Phimosis and Paraphimosis: February 2017Document8 pagesPhimosis and Paraphimosis: February 2017Rollin SidaurukNo ratings yet

- Submited by Chitirala Naveen Y22HA20005Document25 pagesSubmited by Chitirala Naveen Y22HA20005naveen chitiralaNo ratings yet

- 3 4 PERTEMUAN 3 - 4 Far RangkiDocument35 pages3 4 PERTEMUAN 3 - 4 Far RangkiNoerhayatea SibaraniNo ratings yet

- 28.03.23 Nephrology SeminarDocument5 pages28.03.23 Nephrology SeminarJerin XavierNo ratings yet

- Urinary Catheter Care Skills & AsepsisDocument59 pagesUrinary Catheter Care Skills & AsepsisTummalapalli Venkateswara RaoNo ratings yet

- Consolidated List of NDMC HospitalDocument12 pagesConsolidated List of NDMC HospitalgargatworkNo ratings yet

- Nephrology Underpinning For The Young DoctorsDocument7 pagesNephrology Underpinning For The Young DoctorsMahmoud DiaaNo ratings yet

- ICS Standards 2019Document936 pagesICS Standards 2019Gleiciane AguiarNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris 1.13Document5 pagesBahasa Inggris 1.13Rizky AdiNo ratings yet

- Sistem Urinaria: Dr. AL-MUQSITH, M.SiDocument43 pagesSistem Urinaria: Dr. AL-MUQSITH, M.SiAndrey DwiNo ratings yet

- Drug-Induced Urinary RetentionDocument2 pagesDrug-Induced Urinary RetentionMiranda MetriaNo ratings yet

- Comparitive Study of Fifty Cases of Open Pyelolithotomy and Ureterolithotomy With or Without Double J Stent InsertionDocument4 pagesComparitive Study of Fifty Cases of Open Pyelolithotomy and Ureterolithotomy With or Without Double J Stent InsertionSuril VithalaniNo ratings yet

- Bladder PDFDocument22 pagesBladder PDFSuci Mega SariNo ratings yet

- Section A: Jawab Semua SoalanDocument3 pagesSection A: Jawab Semua SoalanAzreen IzetNo ratings yet

- Multi OrgasmusDocument29 pagesMulti Orgasmus4gen_30% (1)

- Updated ICD 10 Codes 2018Document1 pageUpdated ICD 10 Codes 2018Lucian0691No ratings yet

- Laboratory 15Document5 pagesLaboratory 15Isabel Maxine DavidNo ratings yet

- Professional AffiliationsDocument1 pageProfessional AffiliationsDanya Riaz QureshiNo ratings yet

- Bladder Cancer and Its MimicsDocument16 pagesBladder Cancer and Its MimicsmedicoscantareiraNo ratings yet

- Director Marketing Product Manager in Minneapolis MN Resume Judy EastmanDocument3 pagesDirector Marketing Product Manager in Minneapolis MN Resume Judy EastmanJudyEastmanNo ratings yet

- Merck Manual: OF Diagnosis and TherapyDocument22 pagesMerck Manual: OF Diagnosis and TherapyScholl_201133% (3)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology: JournalsDocument5 pagesObstetrics and Gynecology: JournalsNaufalNo ratings yet

- Congenital Anomalies of Ureter BladderDocument17 pagesCongenital Anomalies of Ureter BladderAfiq SabriNo ratings yet

- DysuriaDocument4 pagesDysuriasalamredNo ratings yet

- Chapter 48Document7 pagesChapter 482071317No ratings yet