Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Staying Power of Leveraged Buyouts

The Staying Power of Leveraged Buyouts

Uploaded by

Pepper CorianderOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Staying Power of Leveraged Buyouts

The Staying Power of Leveraged Buyouts

Uploaded by

Pepper CorianderCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal

of Financial

Economics

29 (1991) 287-313.

North-Holland

The staying power of leveraged buyouts*

Steven N. Kaplan

University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637, USA

Nationa! Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, ,tU 02138, tiSA

Received

February

1991, final version

received

May 1991

This paper documents

the organizational

status over time of 183 large leveraged

buyouts

completed

between 1979 and 1986. By August 1990. 62% of the LBOs are privately owned, 11%

are independent

public companies,

and 24% are owned by other public companies.

The

percentage

of LBOs returning

to public ownership

increases over time, with LBOs remaining

private for a median time of 6.82 years. The majority of LBOs, therefore,

are neither short-lived

nor permanent.

The moderate

fraction of LB0 assets owned by other companies

implies that

asset sales play a role, but are not the primary motivating force in LB0 transactions.

1. Introduction

In the 198Os, an unprecedented number of public corporations and their

divisions went private in leveraged buyout transactions (LBOs). LB0 activity

increased from $1.4 billion in 1979 to $77 billion in 198K1 In spite of the

large transaction volume, LBOs remain poorly understood. In particular,

there is a healthy debate about the longevity of LB0 organizations and their

distinguishing characteristics. The answer to this debate has implications for

the reasons LBOs occur and for sources of value in LB0 transactions.

*Michael Beane collected much of the data for this study as part of his MBA honors thesis.

Sang Han provided additional

research assistance.

George Baker (the referee), Eugene Fama,

Robert

Gertner,

Michael Jensen (the editor).

Mark Mitchell,

Kevin IM. Murphy,

Mitchell

Petersen, Andrei Shleifer, Jeremy Stein, Robert Vishny, and seminar participants

at Stanford

University

and the University

of Chicago have provided

helpful comments.

The Center for

Research in Security Prices provided research support.

See Jensen

(1989). Figures

are in 1988 dollars.

See Kaplan (1989a, b) for a discussion

buyouts of public companies.

0304~405X/91/$03.50

D 1991-Elsevier

of and evidence

Science

Publishers

on sources

of value

B.V. (North-Holland)

in management

23s

S.iV. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

Jensen (19891 argues that LB0 organizations solve the free cash flow

problem faced by companies in low-growth industries by providing superior

incentives to managers and their monitors. A large portion of the wealth

increases associated with LB0 transactions are directly attributable to incentives LBOs provide to pay out free cash flow. These include (1) large

debt-service payments required by debt-to-total-capital

ratios exceeding 85%,

(2) large equity stakes held by managers, and, often, (3) the monitoring of an

LB0 sponsor - labeled an active investor by Jensen - who structures the

transaction, owns the majority of the companys equity, and controls the

board of directors. Although public companies (and their managers) are

capable of obtaining the same benefits, they rarely have the incentive to do

so. In low-growth businesses, therefore, Jensen argues the public corporation

is inferior as an organizational form to the LBO.

Under Jensens view that LB0 incentives are a critical source of value,

LBOs should remain private for an unspecified, but significant period. When

and if they subsequently go public, Jensens view suggests that debt levels will

remain high and equity will still be largely held by managers and active

investors.

Jensens view is not the only one that predicts long-lived LB0 organizations. Kaplan (19S9a) and Schipper and Smith (198s) present evidence that

the tax deductibility of interest on buyout debt is potentially an important

source of value in management buyouts. The value of this deductibility

depends on how long the high LB0 debt load is maintained. Tax benefits of

debt are more valuable if the debt is permanent than if it is paid off within

two or three years. The maintenance of high debt levels over a long period,

therefore, would also be consistent with an important role for tax benefits.

The tax theory, however, makes no predictions about equity ownership.

Rappaport (1990) disagrees with Jensen that the LB0 organization is

superior to the public corporation. He argues that the discipline of debt and

concentrated

ownership impose costs of inflexibility to competition and

change. In addition, the typical active investor invests funds provided by

outside investors who expect to be repaid in five to ten years. For these two

reasons, Rappaport argues, buyouts are inherently transitory organizations.

Rappaport might have added that as their equity stakes increase in value,

managers bear an increasing amount of undiversified risk. Over time, one

way managers can reduce or diversify this risk is to return the company to

public ownership.

Although he does not say so explicitly, Rappaports position is consistent

with a buyout as shock therapy. According to this view, buyout incentives

lead managers to focus the organization on cash flow generation, to forego

unprofitable investment opportunities, and to sell unproductive assets. Many

of these changes, however, are one-time events. Once they have been

implemented, the benefits of the buyout incentives are necessarily smaller. At

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

289

some point, the costs of inflexibility, illiquidity, and risk-bearing exceed the

continuing benefits of buyout incentives and the company returns to public

ownership.3

Under Rappaports view, LBOs, needing the flexibility offered by access to

public markets as well as liquidity for managers and outside investors, will

return to public ownership relatively quickly through both initia1 public

offerings (IPOs) and sales to public companies. If managerial risk-bearing

concerns increase with buyout size, larger buyouts should return to public

ownership more often.

The results in Bhagat, Shleifer, and Vishny (1990) suggest that sales to

related public companies may be particularly important. They find that 72%

of the assets of large hostile takeovers are owned by corporations with similar

assets - related or strategic buyers - within three years of the takeover. The

analogous percentage is 43% for the six hostile LBOs in their sample. Only

20% of the assets in hostile takeovers are owned by raiders or buyout-type

organizations within two to three years. They conclude that incentive intensive organizations [i.e., LBOs] are not very important in the long run for

hostile takeovers. A similarly large role for (and rapid implementation of)

sales to related buyers in LBOs would not imply that ownership incentives

are unimportant, but would suggest different sources of buyout gains from

those implied by the Jensen, tax, or Rappaport explanations. Gains from

sales to related buyers could come from joint operating efficiencies between

buyers and sellers, market power, or buyers willingness to overpay for

divisions.

In this paper, I present evidence concerning the different views of LB0

organizations. I examine the post-buyout organizational form of 183 large

LBOs completed between 1979 and 1986 from the time of their completion

through August 1990. As of August 1990, 62% of the LB0 companies are

privately owned, 14% are publicly owned and still independent, and 24%

have been purchased by publicly owned U.S. or foreign companies. The 62%

reflects the current organizational status of the LB0 company, ignoring the

current organizational form of assets sold (and purchased) after the buyout.

The percentage of LB0 assets privately owned changes only slightly, decreasing to 59%, when assets sold (but not assets purchased) are considered.

The 62% and 59% figures are path-independent

percentages in that they

measure the current organizational status of the LB0 assets, ignoring the

path taken to reach that status. LBOs private as of August 1990 include those

that return to private ownership after first having returned to public ownership. Almost 45% of the 170 LBOs whose status can be identified through

3LBOs might also be expected to be short-lived

if buyouts provide a mechanism

for managers

to exploit information

advantages

over public shareholders.

Such information

advantages

would

be less acute in divisional buyouts.

290

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power

of LEOs

the entire period return to public ownership at some point. The median

time - conditional on returning public - these companies remain private is

only 2.63 years. However, the unconditional estimate of the median time

private is 6.82 years.

The likelihood of returning to public ownership is largest and roughly

constant in the second to fifth years after the LBO, and then declines

somewhat, but is again roughly constant thereafter. This pattern can be

interpreted as consistent with two underlying types of buyouts - the shocktherapy type and a longer-term incentive type.

Overall, the evidence suggests that the typical buyout is neither short-lived

nor permanent. Consistent with Rappaport, the large fraction of LBOs

returning to public ownership suggests that the private LB0 is often a

transitory organizational form, bridging periods of public ownership. Alternatively, consistent with the Jensen model and the importance of the incentiveintensive organization, a substantial fraction of LB0 assets are private and

still highly leveraged many years after the LBOs. In addition, the LBOs that

are currently independent public companies appear to be hybrid organizations, retaining some of the characteristics of the LB0 organization - equity

ownership by insiders (managers and buyout investors) and debt ratios that

are higher than their pre-buyout levels. The maintenance of high debt levels

by private LBOs and by independent public companies is also consistent with

a role for tax benefits.

The results also suggest a moderate, but not primary, role for asset sales to

buyers in related industries. Almost 29% of the LB0 companies and 34% of

the original LB0 assets are owned by companies with other operating assets.

This is lower than the 72% reported by Bhagat et al. for only three years

after the hostile takeovers, and somewhat lower than the 43% reported three

years after the six hostile LBOs in their sample. Furthermore, the time

pattern of asset sales in my sample suggests that the typical buyout will

remain independent for more that 15 years. Unlike the Bhagat et al. findings

for hostile takeovers, my results for LBOs are consistent with long-term

incentives playing a role in explaining value increases.

Finally, I report cross-sectional differences in the current public/private

status of the sample LBOs: (1) larger transactions are only moderately more

likely to be publicly owned, suggesting a correspondingly moderate role for

risk-bearing considerations; (2) buyouts sponsored by well-known LB0 associations - the focus of Jensens article - are no more likely to stay private

than other buyouts; and (3) there is no significant difference in the current

public/private status of buyouts of divisions and public companies.

Most of the LBOs considered here are followed by a growing economy in

the first few post-buyout years. In contrast, many of the LBOs completed

after 1986 have to contend with a weakening economy and, possibly, less

S.N Kaplan,

The staying power of LBOs

291

favorable stock and bond markets. At the same time, Kaplan and Stein (1991)

present evidence that buyout prices and financial structures are more aggressive in the 1986-1988 period than earlier. The effect of the increase in deal

aggressiveness and the weakening economy in 1990 on the organizational

experience of LBOs is an open and interesting question.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 describes the sample and the

data collection process. Section 3 presents a detailed analysis of the

private/public

organizational status of the LBOs over time. Section 4 describes other current characteristics of the LBOs. Section 5 examines the

cross-sectional determinants of organizational status, and section 6 concludes.

2. Sample and data

2.1. Sample

The sample includes those transactions identified as leveraged buyouts by

Securities Data Corporation (SD0 or Morgan Stanley & Company between

1979 and 1986. I exclude transactions completed after 1986 to ensure at least

3.67 post-buyout years for changes in organizational form to occur. To

increase the likelihood of identifying a companys current organizational

status, I include only those buyouts with a transaction value greater than

$100 million. This criterion potentially introduces a bias toward reversion to

public ownership, because the costs of risk-bearing to managers are likely to

be greater in larger buyouts.

These criteria generate a sample of 183 companies. The second column of

table 1 shows the number of transactions completed over time. These sample

buyouts were valued at $83.0 billion when they were completed. Over the

same period, W.T. Grimms Mergerstat Review reports $92.2 billion in

going-private and unit management buyout transactions. This sample, therefore, includes a large fraction of the dollar value of transactions completed

between 1979 and 1986.

2.2. Post-buyout information

I obtained post-buyout information on these companies from Lotus Datext

(public and private) databases, the NEXIS database, Wall Street Journal

articles from the year the LB0 was completed through August 1990, and,

when available, financial reports filed with the Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC). Whenever possible, the corporate treasurer or controller

of each sample company was called to confirm the information. The postbuyout information includes, and the telephone interviews attempted to

292

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

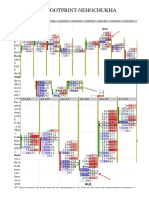

Table 1

Current ownership status of parent company by year of completion for 183 leveraged buyouts

valued at more than $100 million and completed in the period 1979-1986.

Total

Year

LBOsa

1979-1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1:

13

16

37

33

68

1979-1983

1984-1986

45

138

All deals

183

Status

not

knownb

LiquidatedC

Status

known

Percent

publicly

owned

August1990d

Percent

privately

owned

August 1990

11

13

14

31

30

66

40.0

45.5

46.2

64.3

29.0

40.0

31.8

60.0

54.5

53.8

35.7

43

127

51.2

33.1

48.8

66.9

170

37.6

62.4

71.0

60.0

68.2

Sample of leveraged buyouts identified as leveraged buyouts by either Securities Data

Corporation or Morgan Stanley.

bA buyouts status is not known if I could not contact the company or find any information

about it.

A buyout is considered liquidated if the company (1) has been completely sold in more than

one transaction to both public and private buyers, or (2) no longer exists.

dA buyout is considered a public entity if (I) it has issued equity to the public and is still a

public company as of August 30, 1990, or (2) the buyout company has been purchased by and is

still owned by any public company, either domestic or foreign.

A buyout is considered a private entity if the buyout company is still privately owned,either

by the buyout company or by a subsequent private buyer.

confirm, the following: (1) the date and dollar value of the original transaction, (2) whether assets had been sold since the LB0 and if so, their identity,

their dollar value, the acquirer, and the organizational form of the acquirer,

and (3) the current ownership status and organizational form of the company.

3. Post-buyout

status - Private or public assets?

3.1. Current organizational status - LB0 company

Table 1 presents the current status of the 183 buyout companies by year of

LBO. These companies are classified into one of four basic categories:

(1) unidentified, (2) liquidated, (3) still privately owned (including companies

in Chapter 111, or (4) publicly owned. Some post-buyout information is

available for 179 of the 183 companies. The remaining four could not be

identified; presumably, they have either changed their names, been sold, or

S.N Kaplan, Thr staying power of LBOs

293

gone bankrupt. At most, therefore, the analysis in the rest of the paper uses

these 179 companies. An additional nine companies have an ambiguous

organizational form because (1) they failed (and no longer exist) or (2) they

were sold in more than one transaction to both private and public buyers.

The remaining 170 companies have an August 1990 organizational form I

could identify. At a minimum, the analysis that follows uses these 170

companies.

As of August 1990, 62.4% (or 106) of the 170 LBOs of known status are

still privately owned. The remaining 37.6% (or 64) are publicly owned - 13.5%

(or 23) are independent public companies and 24.1% (or 41) are owned by

other public companies. The 62.4% result pertains to all of the LBOs in the

sample. LBOs completed at the end of 1986 have had as Iittle as 3.67 years to

change organizational forms since the buyout, compared with over 11 years

for LBOs completed in 1979. If LBOs are transitory organizations with

uncertain lives, one would expect fewer of the earlier LBOs to be privately

owned. The pattern in table 1 is roughly consistent with this. Only 48.8% of

LBOs completed by 1983 are still privately owned, compared with almost

67% of LBOs completed after 1983. But the pattern is by no means

monotonic: fewer than 36% of the LBOs completed in 1983 are still private,

compared with almost 55% of those completed in 1981.

3.2. Current organizational status - All assets

The previous results reflect the current organizational status of the LB0

company. They would be misleading if many of the buyout companies make

large divestitures and sell the divested assets to public companies. To address

this possibility, I calculate the fraction of a companys assets that are private

as of August 1990. For each sample LBO, I determine the current organizational form of all of the companys assets. If no assets have been sold, then all

of the companys assets are either public or private, depending on the

buyouts current organizational status. For LBOs that have sold assets, the

fraction of assets still private is calculated as the value-weighted average of

the public/private

status of both the retained and sold assets. In the few

cases in which all of the assets of the LB0 company have been sold, the sale

prices of the different assets are used as weights. In those cases in which

some assets are not sold (and, therefore, cannot be valued), accounting

numbers are applied as weights to all of the buyout-company assets. Operating incomes before interest, depreciation, and taxes of the different assets are

used as weights if they can be calculated. Book assets are used if operating

income results are not available, and, finally, sales, if book assets are not

available. In most cases, these accounting weights are based on the accounting results for the buyout company assets in the last pre-buyout fiscal year.

J.F.E.-

294

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

Table 2

Estimated current ownership status of average company assets by year of completion of 176

leveraged buyoutsa valued at more than $100 million and completed in the period 1979-1986.

Year

Number

LBOs

Percent assets

publicly owned

August 1990b

Percent assets

privately owned

August 1990

40.0

60.0

57.3

51.1

30.0

60.3

57.0

67.5

1979-1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

13

14

35

32

66

42.7

48.9

70.0

39.7

43.0

32.5

1979-1983

1984-1986

43

133

53.2

36.9

16.8

63.1

All deals

176

40.9

59.1

1;

aSample of leveraged buyouts identified as leveraged buyouts by either Securities Data

Corporation or Morgan Stanley. Seven of 183 LBOs are excluded because I could not contact

the company or find the required information about it.

bAssets of buyout company are considered public if they are owned by a publicly owned

company as of August 30, 1990. This column measures the average fraction of company assets

private for all LBOs completed in the given period.

Assets of a buyout company are considered private if they are still privately owned. either by

the buyout company or by a subsequent private buyer, as of August 30, 1990. This column

measures the average fraction of company assets private for all LBOs completed in the given

period.

Table 2 shows that the adjustment for asset sales decreases the fraction of

assets privately owned slightly - from 62.4% to 59.1%. The pattern over time

is similar to that for the current organizational form of the LBOs. The

number of LBOs that contribute to this table increases to 176 because the

assets of six of the nine companies with an ambiguous current organizational

form can be traced. It is worth adding that the 59.1% result is a lower bound

on the assets private because it does not adjust for post-buyout purchases of

public assets by the private companies.

3.3. OrganizationaE status by year after LB0

Instead of presenting the fraction of LBOs that are private by year of LB0

completion, table 3 presents the fraction of LBOs that are private by year

after the LBO. This is analogous to considering organizational status in event

Unfortunately, I did not collect information on asset purchases. Given the small effect asset

sales have on the percentage of privately owned assets, it seems likely that asset purchases would

increase the percentage of assets private by less than 5%.

295

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

Table 3

Ownership

Age of LB0

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

status of parent company

by age of leveraged

buyout for 179 leveraged

valued at more than SIOO million and completed in ther period 1979-1986.

Total LBOs status

known at year i

179

176

175

139

93

65

39

24

7

4

buyouts

Percentage

publicly ownedh

Percentage

privately ownedC

2.s

15.9

25.1

32.4

33.3

37.9

43.6

45.8

25.6

0.0

97.2

84.1

74.9

67.6

66.7

62.1

56.3

54.2

71.4

100.0

aSample

of leveraged

buyouts

identified

as leveraged

buyouts by either Securities

Data

Corporation

or Morgan Stanley. Four of 183 LBOs are excluded because I could not contact the

company or find any information

about it. Year i is the end of year i after the buyout.

bA buyout is considered

a public entity if (1) it has issued equity to the public and is still a

public company, or (2) the buyout company has been purchased

by and is still owned by any

public company, either domestic or foreign, i years after the buyout.

A buyout is considered

a private entity if the buyout company is still privately owned, either

by the buyout company or by a subsequent

private buyer i years after the buyout.

time. This table uses all 179 of the LBOs for which data are available. The

nine companies with an ambiguous current form are included for years in

which their forms are not ambiguous.

From year 1 to year 8 after the buyout, the fraction of LBOs that are

privately owned decreases monotonically from 97.2% to 54.2%. The fraction

increases in years 9 and 10, but the increases are based on a small number of

observations.

Tables l-3 show that LBOs return to public ownership at widely varying

times. Just over 25% are publicly owned three years after the buyout, rising

to almost 46% by eight years after the buyout. This pattern suggests that the

typical buyout is neither short-lived nor permanent.

3.4. Estimates of time spent pricate

The percentages given above are path-independent

percentages in that

they measure the current organizational status of the LB0 assets regardless

of how they reached that status. They do not distinguish between (1) LBOs

still private from the original LB0 and (2) LBOs that have gone private a

second time after returning to public ownership. Table 4 presents the time

pattern relative to the year of buyout completion by which LBOs return to

XV. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

296

Table 4

Percentage

leveraged

LBOS

private at

beginning of

Year i

Year

after

LB0

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

Year

of LBOs that

buyouts valued

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

170

164

142

124

80

48

32

20

12

5

4

return

to public ownership

by age of leveraged

buyout for 170

at more than $100 million and completed in the period 1979-1986.

LBOs

returning

to public

ownershipb

LBOs

censoredC

6

22

18

17

7

3

1

1

0

0

1

0

0

0

27

25

13

11

7

7

1

3

Cumulative

survival

rate (LBOs

privateJd

Cumulative

failure rate

(LBOs

publicjd

96.5

83.5

72.9

62.2

56.0

52.1

49.6

47.2

41.2

47.2

35.0

3.5

16.5

27.1

37.8

44.0

47.9

50.4

52.8

52.8

52.8

65.0

LBOs private at beginning of year i include those LBOs that (1) have not yet returned

to

some form of public ownership,

and (2) were completed

more than i - 1 years earlier. Includes

only the 170 LBOs whose organizational

status is known for all post-buyout

years.

A buyout is considered

a public entity if (1) it has issued equity to the public and is still a

public company, or (2) the buyout company has been purchased

by and is still owned by any

public company, either domestic or foreign, i years after the buyout.

LBOs censored are LBOs that (1) were completed between i - 1 and i years earlier. and (2)

are still private as of August 1990.

dThe cumulative

survival rate, S(f ), or product limit estimate equals:

S(r,) =

fr

&=I

(1 -d&/n,),

where d, is the number of LBOs that return public at I, and hk is the number of LBOs that

have (1) not yet returned public just prior to fj and (2) were completed at least t, years before.

The cumulative

failure rate, 1 - S(tj), is the estimated fraction of LBOs that have returned

to

public ownership

t, years after completing

an LBO.

public ownership. Almost 45% - 76 of 170 - of the LBOs whose status can

be identified through the entire period return to public ownership at some

point. Forty-two of these companies go public by issuing equity to public

shareholders. The remaining 34 are purchased by publicly owned companies,

both domestic and foreign. The median time - conditional on returning

public - these companies stayed private is only 2.63 years, and the conditional average is 2.85 years. This is similar to the median 2.42 and average

2.89 years spent under private ownership by the 76 firms examined by

Muscarella and Vetsuypens (1990).

The differences between the 45% result in this section and the smaller

percentage in the previous ones reflect the fact that 12 of the 76 companies

that return to public ownership subsequently go private again. Nine of these

S.;V. Kaplun, The staying power of LBOs

297

12 are independent public companies that complete a second LBO, suggesting that public ownership was not optimal. The remaining three are owned by

other public companies that subsequently go private. The 12 companies

remain public a median of 2.46 years (and an average of 2.34 years) before

going private again.

If all the LBOs in the sample had returned to public ownership at a known

time, it would be possible to calculate the unconditional median (and

average) time private directly. As table 4 shows, however, the majority of

LBOs in this sample are private as of August 1990 and must be considered

censored observations. LBOs are censored in year i after the LB0 if they are

still private as of August 1990, but were completed between i - 1 and i years

before August 1990.

It is possible to use the information about returns to public ownership and

censored observations to estimate both the median time and the overall

distribution of time it takes an LB0 to return to public ownership. The

product limit or Kaplan-Meier estimate of the survivor function is

s(l,)=kfil(l-d!c/,,,),

(1)

where d, is the number of LBOs that return public at tk and nk is the

number of LBOs that have 1) not yet returned public just prior to fk and

2) were completed at least t, years before. These estimates can be considered maximum-likelihood estimates [see ch. 1 of Kalbfleisch and Prentice

(1980)]. Here, 1 - .5(t) is the cumulative distribution function of the probability of returning to public ownership.

Table 4 shows that the median survival time or time to public ownership is

between six and seven years after the LBO. The estimated median time is

6.82 years. If the last observation were not private and the oldest LB0

returned public in September 1990, the estimated mean would equal 6.80

years. Because the last observation is censored, this estimated mean is clearly

downward biased. The estimated standard error using the 6.80 year mean is

0.36.j

The 6.82 year median time private is longer than the period supposedly

targeted by LB0

associations

for cashing out their initial investments.

Jensen (19891 claims that the goal is three

to five years. Returning

to public ownership,

however, is not the only way for investors to cash

out. As Jensen and Rappaport

note, LBOs can be releveraged

in a second LBO. In addition to

collecting data on buyout public/private

status, I attempted

to keep track of releveragings.

By

including releveragings

as well as returns to public ownership.

I can estimate the median time for

an investor to cash out. Almost 60% of the buyouts have cashed out in some way. The product

limit estimate of this median is 4.02 years. almost exactly midway through the goal of three to

five years.

298

S.N. Kaplan,

The staying power of LBOs

3.5. Duration dependence

The data used to construct table 4 can also be used to estimate the relation

between the likelihood of returning public and time. This relation is known

as duration dependence. Duration dependence is positive if the probability

that an LB0 returns to public ownership during the ith period, conditional

on being private at the beginning of the ith period, increases over time. and

negative if the probability decreases. The conditional likelihood is commonly

referred to as the hazard.

An examination of duration dependence provides important information

on the process by which LBOs return to public ownership. A finding of

negative duration dependence would imply that LBOs remaining private for

some time become increasingly likely to remain private. This could result if

initial uncertainty about the benefits of private ownership are resolved over

time. Companies that find the benefits of private ownership large become

increasingly Less likely to return to public ownership. Negative duration

dependence would be consistent with permanence for some LBOs.

Alternatively, negative duration dependence could reflect the existence of

unobserved heterogeneity. For example, suppose there are two vpes of

LBOs - shock-therapy LBOs and longer-term LBOs - both with constant

hazards. The shock-therapy types might be those for which the LB0 serves as

a change agent to shake up an inefficient organization, which is then better

organized as a public company because of flexibility or risk-bearing considerations. The longer-term types might be buyouts that more closely follow

Jensens characterization. Initially, a random LBOs likelihood of returning

public (conditional on being private) will be a weighted average of the

number of the two types in the sample. Over time, however. the short-term

LBOs will return to public ownership and only longer-term LBOs will

remain. As a result, estimated duration dependence will be negative. The

longer-term LBOs, however, will continue to return to public ownership at

their lower, but constant rate.

Negative duration dependence, therefore, would be consistent with permanence for some LBOs, but could also indicate the presence of unobserved

heterogeneity. In contrast, positive or no duration dependence would imply

that LBOs return to public ownership at some constant or increasing rate.6

Estimating the hazard function over time can also provide information on

the timing of possible flexibility, liquidity, and risk-bearing pressures. Although the shock-therapy view suggests that these pressures will lead LBOs

to return to public ownership after making one-time changes, it makes no

predictions about how long the changes take and how quickly the pressures

build.

6See Kiefer (1988,

pp. 671-672)

for a clear discussion

of these

issues.

299

S.:V. Kaplan, The sta.vingpower of LBOs

Following Lancaster (1990>, I estimate a piecewise-continuous

hazard

model.This specification lets the data tell us how the hazard behaves as a

function of time. This involves maximizing the log-likelihood function:

where di = 1 if the buyout returns to public ownership r; years after the

buyout, di = 0 if the buyout is still private in August 1990, ti years after the

buyout, and

S(ti;B) =exp i

P(G)=&+I

if

k bjPj-(ti_cy)Py+1

j=O

bj=cj-cj_,,

cy <tiIcL.+,,

where f< ) is the distribution function and S( 1 the survivor function. This

specification assumes that the hazard, pi, is constant during each interval,

ci_, to ci. These intervals are generally taken to be annual. The hazard

represents the likelihood that a buyout will return to public ownership in the

ith year after the LBO, given that the LB0 was still private at the beginning

of the ith year.

In addition to potential duration effects, year effects can exist. For example, LBOs completed in 1983 may have been different from LBOs completed

in 1986. Accordingly, some specifications include a set of dummy variables

based on the year the LB0 was completed (except for 1986). These dummy

variables should be compared with LBOs completed in 1986.5

Table 5 presents the model estimates. Regression 1 indicates that the

estimated probability of returning public (conditional on being private) is

lowest in the first post-buyout year, at 3.6%. The estimated probability peaks

in the fourth year, at 15.4%, declines in the fifth through seventh years, and

rebounds thereafter. Given the standard errors, the pattern is roughly consistent with constant duration dependence in years 2 through 5, and then a

lower, but constant, duration dependence in years 6 and after.

The previous version of this paper used logit estimates

rather than the duration-model

hazard estimates.

I have made this change for two reasons.

First, the duration

model can

incorporate

partial-year

censoring while the logit model cannot. This is particularly

important

for

estimating

the hazards for more than five years after the buyout, where there are fewer

observations.

Second, the coefficients are easier to interpret.

In the estimation.

this amounts to redefining

each p, to equal p,exp(4x),

vector of completion-);ear

diimmy variables and 4 is a vector of five coefficients

where x is the

to be estimated.

XIV. Kaplan,

300

7%e staying power of LBOr

Table 5

Maximum-likelihood estimates2 of the (conditional) probability of returning to public ownership

as a function of the time since the LB0 and of the LB0 completion year for 170 leveraged

buyouts valued at more than $100 million and completed in the period 1939-1986.

Probability/hazard

(1)

1st yearb

2nd year

3rd year

4th year

5th year

6th year

7th year

8th year

9th year and later

2nd to 5th year

6th year and later

2nd year and later

1981 and earlier

1982

1983

1984

1985

estimates of returning to public ownership

(2)

Coeff.

SE.

0.036e

0.144d

0.134d

0.154d

0.112d

0.072f

0.040

0.062

0.063

0.015

0.031

0.032

0.038

0.042

0.041

0.041

0.061

0.067

Coeff.

0.032d

0.130d

0.123d

0.143d

0.102e

0.073

0.040

0.065

0.080

- 0.262

0.018

0.578

- 0.196

0.493

No. of obs.

Log-likelihood

(3)

SE.

Coeff.

0.013

0.040

0.041

0.042

0.047

0.048

0.044

0.070

0.095

0.505

0.494

0.409

0.388

0.336

170

- 235.37

170

- 238.65

(4)

S.E.

0.032d

0.013

0.130d

0.066f

0.031

0.034

- 0.288

- 0.017

0.544

- 0.227

0.464

0.474

0.471

0.399

0.374

0.326

170

- 235.85

Coeff.

SE.

0.034d

0.014

0.129

- 0.529

-0.164

0.437

-0.315

0.455

0.031

0.432

0.442

0.377

0.366

0.326

170

- 237.12

The log-likelihood function is

L(P)=

Cd,lnf,(l,,p)+

C(l--d,)lnS(t,,/-J),

where d, = 1 if buyout returns to public ownership and 0 if censored, with distribution function

f,(f,>P) =P,+J(t,.P)>

and survivor function

S(ti,P)=exP

Cy<fiZZCCy+,,

-j~~j-(t-cy)Oy+l}3

Nt,)

= P,+1

if

cY < ri <cy_,.

bThe ith year coefficients estimate the hazard or likelihood of returning to public ownership in

the ith year after the buyout conditional on being private at the beginning of the year. The nth

year and later coefficients estimate the annual hazard in the n year or later after the LBO. The

second to fifth year coefficient estimates the annual hazard in the second to fifth year after the

LBO.

The variables 1982 to 1985 equal one if the LB0 is completed in that year and zero

otherwise. The 1981 and earlier variable equals one for LBOs completed in 1981 and earlier.

dSignificant at the 1% level.

Significant at the 5% level.

Significant at the 10% level.

S.,V. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

301

Regression 2 uses the same variables as regression 1, but controls for the

year the LB0 is completed. The basic pattern of the hazards is similar to that

of regression 1, but the coefficients in the second to fifth post-buyout years

decrease, while the coefficients for the sixth to ninth post-buyout years

increase. The likely explanation for the compression of these coefficients is

based on the negative coefficient (-0.262) on the 1981 and earlier variable.

The coefficient suggests that 1981 and earlier deals are 23% less likely in any

post-buyout year to return to public ownership than are 1986 buyouts.

Because a large fraction of the sixth to ninth post-buyout-year observations

are for LBOs completed in 1981 and earlier, not controlling for the LB0

completion year lowers the coefficients on the sixth to ninth post-buyout-year

variables relative to the earlier year variables. Consistent with table 1,

regression 2 also indicates that LBOs completed in 1983 are somewhat more

likely to return to public ownership in a given year than are LBOs completed

in other years.

The coefficients in regressions 1 and 2 suggest that there are two different

periods of constant duration dependence. To test explicitly for this, regression 3 replaces the eight post-buyout variables for the second year through

the ninth year and later with two variables: one for the second through fifth

year and one for the sixth year and later. The likelihood-ratio test statistic of

0.56 is not significant at conventional levels (chi-square distribution with six

degrees of freedom, p-value = 0.99). This breakdown suggests three different

likelihoods of returning to public ownership. The likelihood is small - at

3.2% - in the first post-buyout year, high - at 13.0% - in years 2 through 5,

and intermediate - at 6.6% - but constant, thereafter. As discussed above,

this pattern is potentially consistent with two underlying types of buyouts - a

shock-therapy type and a long-term type - if the shock-therapy LBOs have

largely returned to public ownership by the end of the fifth post-buyout year.

It is important to add that the hazards for the longer-term types do not

exhibit negative duration dependence. Although the probability that the

longer-term types return to public ownership is smaller, it does not decrease

over time, suggesting that these longer-term types will eventually go public

again.

The standard errors on the second through fifth year and sixth year and

later coefficients, however, are sufficiently large that the coefficients may not

be statistically different. Regression 4 tests this by replacing the two postbuyout-year variables with one variable that equals one if the observation is

for the second post-buyout year and after. The likelihood-ratio test statistic

of 2.54 is not significant at conventional levels (chi-square distribution with

one degree of freedom, p-value = 0.12). If one were to argue on purely

statistical grounds, therefore, the data fail to reject the hypothesis that after

the first year, the LB0 companies are equally likely to return to public

ownership. Economically, however, the difference between 13% and 6.6%

302

S.N. Kaplan,

The slaying power of LBOs

seems meaningful. The resolution of this discrepancy must await more

observations.

Overall, the results in this section suggest that LBOs are neither short-lived

nor permanent organizational forms. Neither the estimates in regression 3

with two LB0 types nor those in regression 4 with the constant hazard rate

find evidence for negative duration dependence.

4. Current LB0 characteristics

The analysis to this point distinguishes between privately and publicly

owned assets. It does not describe whether LB0 companies and assets are

still independently owned or have been purchased by other companies. In

addition, the private/public

dichotomy does not necessarily imply large

differences in post-buyout leverage or equity ownership. This section presents

evidence on post-buyout independence, leverage, and equity ownership.

4.1. Independent

or strategic assets?

As mentioned earlier, whether buyout companies remain independent or

are purchased by other companies has a strong bearing on the source of

value in LBOs. Although it would not imply that ownership incentives are

unimportant, a large role for and rapid implementation of asset sales in

LBOs would suggest different sources of buyout gains from those implied by

the Jensen, tax, or Rappaport explanations. Gains from asset sales to related

buyers could come from joint operating efficiencies between buyers and

sellers, market power, or buyers willingness to overpay for divisions, and not

from long-term changes in incentives.

Table 6 classifies the companies in my sample by their current private or

public status, and, within that status, by whether they are independent or

owned by another company. Of the 170 LBOs I can classify, 49 or 28.8% are

owned by companies with other operating assets. Because some of the

purchasers might be in unrelated businesses, 28.8% is an upper bound on the

percentage of LB0 companies that can be owned by related buyers. Most of

the companies that purchase LBOs - 41 of 49 - are public.

Although not presented in a table, a duration dependence analysis similar

to that reported for public/private status finds negative duration dependence

more than four years after the buyout. The estimates imply that the median

company will stay independently-owned

for more than 15 years.

9LB0 companies that are releveraged by a new LB0 investor group are considered to be

independently owned.

303

S..V, Kaplan, The slaying power of LBOs

Table 6

Number

Year

and ownership

Total

LBOs

status

known

status as of August 1990 of 170 leveraged buyouts

$100 million and completed in the period 1979-1986.

Publicly owned

Independent

August

1990b Privately

Owned by

other

ocompany

Total

Independent

owned August

valued

at more than

1990 often&

Owned by

other

company

Total

owned by

other

company

1979-1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

5

11

13

14

31

30

66

2

1

2

3

3

3

9

0

4

4

6

6

9

12

2

;:

9

9

12

21

2

6

6

4

20

I6

44

1

0

1

1

2

2

1

3

6

7

5

22

18

45

20.0

36.4

38.5

50.0

25.8

36.7

19.7

1979-1983

1984-1986

43

127

8

15

14

27

22

42

18

80

3

5

21

8.5

39.5

25.2

All deals

170

23

41

64

9s

106

28.8

%ample

of leveraged

buyouts identified

as leveraged

buyouts by either Securities

Data

Corporation

or Morgan Stanley. Includes only the 170 LBOs whose organizational

status is

known for all post-buyout

years. A buyouts status is not known if I could not contact the

company or find any information

about it.

bA buyout is considered

a public entity if (1) it has issued equity to the public and is still a

public company as of August 30, 1990, or (2) the buyout company has been purchased

by and is

still owned by any public company, either domestic or foreign.

A buyout is considered

a private entity if the buyout company is still privately owned, either

by the buyout company or by a subsequent

private buyer.

I also consider (but do not report in a table) the independent or nonindependent status of all original LB0 assets, including those that are divested. I

find that 33.6% are owned by other companies. Because I do not measure

post-LB0 asset purchases by the LB0 companies, the 33.6% overstates the

extent of sell-off activity.

These results imply a moderate role for asset sales to strategic buyers in

LBOs. Only 28.8% of the LB0 companies and 33.6% of the original LB0

assets are owned by companies with other operating assets at least 3.67 years

after the buyout. These are lower than the 72% reported by Bhagat et al. for

three years after hostile takeovers, and the 43% reported for the six LBOs in

their sample. Furthermore, the time pattern of independence suggests the

average life of independence is long.

It is possible that asset sales are more important for LBOs motivated by

hostile pressure. Accordingly, I divide the sample into hostile and friendly

LBOs. LBOs are considered hostile if: (1) the LB0 receives or is a response

to a hostile takeover bid; (2) the LB0 announcement follows the purchase of

at least 5% of the LB0 company equity by a hostile party in the prior six

months; or (3) the LB0 is a division of a company that satisfies the hostile

304

S.N. Kaplan, The rtayingpowr

of LBOs

definitions in (1) and (2). For LBOs classified as hostile, 26.2% of the

companies and 35.1% of the assets are owned by companies with other

operating assets; for LBOs classified as friendly, the percentages are 28.6%

and 32.8%. Neither of the differences between hostile and friendly LBOs is

significant. The extent of asset sales to strategic buyers. therefore, is not

related to the actual presence of hostile pressure. (It is possible, but not

testable, that this result would change if it were possible to measure unobserved, but perceived, hostile pressure.)

Overall, these results are consistent with the view that long-term incentives

are important in explaining the gains in LBOs.

4.2. Is high leverage maintained?

One of the distinguishing characteristics of an LB0 is high leverage.

Kaplan (1989b) reports a median debt to total capital ratio of 87.8% at

buyout completion for management buyouts announced between 1979 and

1985. This contrasts with a debt to total capital ratio of only 18.8% before the

buyout. LBOs that remain private need not retain their high leverage.

Similarly, LBOs that return to public ownership do not necessarily eliminate

their debt. This section considers the post-buyout capital structure, when

available, of the sample LBOs at the end of fiscal year 1989 (the last fiscal

year-end with such data).

I measure post-buyout capital structure or leverage in three ways. The first

measure is the book value of total debt (short-term and long-term) as a

fraction of the book value of total capital where total capital is the sum of

total debt, preferred stock, and common equity. The second measure is the

book value of total debt as a fraction of the LB0 transaction value reported

by SDC or Morgan Stanley. The third measure is the ratio of interest expense

to operating income before interest, depreciation, and taxes in fiscal year

1989. To serve as a benchmark, I compare the first and the third measures

for the LBOs with those for all nonfinancial public companies on COMPUSTAT with total assets of at least $100 million.

Capital structure data for the 1989 fiscal year are publicly available for 22

of the 23 LBOs that are independent public companies in August 1990. Such

data are available for only 33 of the 98 privately owned LBOs. Although the

relatively small fraction of data for privately owned LBOs leaves open the

possibility of ex post selection bias, the direction of that bias is not clear.

Panel A of table 7 shows that the 33 privately owned and independent

LBOs maintain high debt levels after the buyout. These companies have a

median percentage of total debt to total capital of 97.8% at the end of fiscal

yeas 1989. Total debt for these companies is 91% of the LB0 transaction

value. These values are similar to those found by Kaplan (1989b) at the time

S.&Y Kaplan. The staying power of LBOs

305

Table 7

Median debt to total capital, debt to initial transaction

value, interest to operating

income, and

equity ownership

by insiders at the end of the 1989 fiscal year by current organizational

status

for 90 leveraged

buyoutsa

valued at more than $100 million and completed

in the period

1979-1986 and for comparison

sample of public companies.

A. All independent

LBOs private

LBOs public

Total debt

to initial

deal valueC

Interest

expense to

operating

incorned

Inside

equity

ownership

fractione

33

22

0.978

0.718

0.910

0.607

0.719

0.276

N.A.

0.390

4

31

0.923

0.481

N.A.

N.A.

0.704

0.248

N.A.

0.066

0.435

N.A.

0.235

0.050

LBOsf

B. All purchased

LBOs

Private LB0 purchasers

Public LB0 purchasers

C. Comparison

companiesg

Number

of LBOs

Total debt to

total capital

(book valuejb

public

Sample

of leveraged

buyouts identified

as leveraged

buyouts by either Securities

Data

Corporation

(SDC) or Morgan Stanley.

bTotal debt is the book value of total debt for fiscal year 1989. Total capital (book value)

equals the book value of total debt, preferred

stock, and common equity for fiscal year 1989.

Initial deal value is the LB0 transaction

value given by SDC or Morgan Stanley.

Operating

income is before interest, depreciation,

and taxes.

eInsider equity ownership is the fraction of common stock owned by managers, directors, and

buyout sponsors of the independent

public LBOs and by managers and directors of the public

LB0 purchasers.

Shares of different classes of common stock are treated equally regardless of

voting rights.

LBOs are independent

if they have not been purchased

by another company with operating

assets. Assets of a buyout company are considered

public if they are owned by a publicly owned

company as of August 30, 1990, and private if they are owned by a privately owned company.

Debt to total capital and interest expense to operating

income are calculated

for fiscal year

1989 for all nonfinancial

public companies

on COMPUSTAT

with total assets exceeding $100

million. Insider equity ownership

is calculated

by 1McConnell and Servaes (1990) for 1,093 firms

tracked by the Value Line Investment

Survey in 1986.

LBOs are completed. The debt to total capital ratio is much greater than the

median ratio of 0.435 in fiscal year 1989 for the sample of nonfinancial public

companies. The median ratio of interest expense to ,operating income of

0.719 is also high relative to the median ratio of 0.235 for the nonfinancial

public companies. The 0.719 ratio, however, is somewhat less than the 0.833

ratio of projected post-buyout interest expense to pre-buyout operating

income found by Kaplan and Stein (1991) for 124 larger management buyouts

in the 1980s.

The 22 publicly owned and independent LBOs maintain substantial debt,

but less than the privately owned LBOs. The median percentage of tota debt

to total (book) capital is 71.8%, and total debt is 60.7% of the LB0

transaction value. The debt levels for the public LBOs are higher than the

306

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power

of LBOs

pre-buyout levels of 18.8% reported by Kaplan (1989b). Interest expense to

operating income, however, falls more sharply than for the private LBOs.

The ratio of 0.276 slightly exceeds the median 0.235 for the nonfinancial

public companies, but is much lower than the 0.833 found by Kaplan and

Stein for management buyouts in the 1980s at the time of the buyout.

The seeming discrepancy between the coverage and debt-ratio results is

probably caused by two factors. First, book values of equity do not necessarily

reflect market values. This is particularly true following a large stock market

increase like that experienced in much of the 1980s. Second, interest expense

to operating income will decline as short-term interest rates fall - as they did

from the early to the later 1980s - and as operating income increases. Such

operating-income increases will not immediately translate into large increases

in book equity.

As the previous section indicates, almost 29% of the LB0 companies have

been purchased by other companies. Leverage data for the 1989 fiscal year

are publicly available for 35 of these purchasers. Panel B of table 7 shows

that the median ratios of debt to total capital and interest expense to

operating income for the four private LB0 purchasers are similar to those of

the private and independent LBOs. The ratios for the 31 public LB0

purchasers are simiIar to those for the nonfinancia1 public companies presented in panel C.

The results in this section suggest that privately owned LBOs, both

independent and purchased, maintain debt levels similar to the levels when

the LB0 was compIeted. In contrast, publicly owned LBOs, both independent and purchased, maintain debt levels lower than the initial LB0 levels,

but somewhat higher than both pre-buyout levels and median pubIic-company levels.

4.3. Is high equity ownership maintained?

Another distinguishing characteristic of LBOs is concentrated equity ownership. Management and the LB0 promoter typically own or control 100% of

the post-buyout equity. According to the Jensen view, the concentrated

equity ownership provides strong incentives for managers and the LB0

promoter to maximize shareholder value. By definition, LBOs that remain

privately owned retain their concentrated equity ownership structure. It is an

empirical question whether LBOs that return to public ownership, either as

independent companies or as purchases of other companies, are stili characterized by concentrated equity ownership.

Stock ownership data are available for 18 of the 22 independent public

LBOs for fiscal year 1989. As panel A of table 7 indicates, insiders (buyout

sponsors and managers) hold a median of 39.0% (and an average of 41.6%)

of post-IPO equity in these 18 companies. McConnell and Servaes (1990)

S.IV Kaplan, The sruying power of LBOs

307

examine over 1,000 nonfinancial companies tracked by the Value Line

Investment Survey in 1986 and find a median insider ownership of 5.0% (and

an average of 11.8%). The much larger insider ownership percentages of

post-IPO equity suggest that significant incentives to maximize shareholder

value are still present in LBOs that return public but remain independent.

Stock ownership data are also available for the 31 public puchasers of LB0

companies for fiscal year 1989. Insiders own a median of 6.6% (and an

average of 17.1%) of the equity in these companies. These ownership

percentages are slightly higher than, but not significantly different from, the

corresponding percentages in McConnell and Servaes. Public LB0 purchasers, therefore, do not appear to be characterized by particularly concentrated equity ownership.

5. Cross-sectional

determinants

of public/private

status

The public/private

status results presented above control only for LB0

completion date and LB0 age. This section examines the relation between

public/private status and several other variables that may affect that status.

Univariate results are followed by multivariate results that also control for

the LB0 completion date.

5.1. The importance of size

As the market value of equity owned by undiversified LB0 equity owners

increases, the risk-bearing costs of these holdings also increase. The higher

these costs, the more likely should be the LB0 companys return to public

ownership. Similarly, an LB0 company may require access to public equity

markets to finance future investment after desired organizational changes are

implemented under the LB0 organization. If risk-bearing costs and the need

ultimately to gain access to public equity markets increase with the value of

the LB0 transaction, larger LBOs should be more likely to be publicly

owned.

Panel A of table 8 divides the sample approximately into size quartiles and

presents the current private or public status of LBOs in the different

quartiles. The percentages of privately owned buyouts from the smallest to

largest quartile are 68.2%, 64.3%, 54.5%, and 62.5%. Although fewer of the

larger buyouts are privately owned, the patterns are not monotonic, nor are

the differences significant at conventional levels. The chi-square statistic that

all quartiles have equal percentages is 1.85 with three degrees of freedom

(p-value = 0.61); the chi-square statistic that the smaller two quartiles have

the same percentage as the larger two quartiles is 1.46 with one degree of

freedom (p-value = 0.23). Surprisingly, this evidence implies at best a moderate role for the size of the LBO. One possible explanation is that risk-bearing

308

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOr

Table 8

Public or private status of (1) buyouts by transaction

size, (2) buyouts arranged

by LB0

partnerships,

merchant

banks, and all others, and (3) divisional and public company buyouts as

of August 1990 for 183 leveraged buyouts valued at more than St00 million and completed in the

period 1979- 1986.

Total

A. Smallest quartile, less than $150 M

Second quartile, $150 M-$244 M

Third quartile, $245 M-$459 M

Largest quartile, at least $460 M

B. LB0 partnership=

Merchant bankb

All others

C. Division

Public company

All buyouts

Status

unknown or

liquidated

as of

August

1990

Status

known

as of

August

1990

Percentage

publicly

owned

as of

August

1990

Percentage

privately

owned

as of

August

1990

47

46

45

45

3

4

1

5

44

42

44

40

31.8

35.7

45.5

37.5

68.2

64.3

54.5

62.5

50

24

109

4

0

9

46

24

100

45.7

29.2

36.0

54.3

70.8

64.0

9.5

88

7

6

88

82

38.6

34. I

61.4

65.9

183

13

170

37.6

62.4

aLBO partnership

LBOs are LBOs arranged

by Adler Shaykin, Clayton Dubilier, Forstmann

Little, Gibbons

Green, Hicks & Haas, Kelso, Kohlberg

Kravis Roberts,

Riordan

Freeman,

Thomas Lee, Warburg Pincus, and Wesray.

bMerchant

bank LBOs are LBOs arranged

by Allen & Company,

Bankers Trust, Citicorp,

Donaldson

Lufkin Jenrette, First Boston, Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley.

costs do not vary much once a buyout has reached $100 million in size. To

find an effect, one might have to look at smaller buyouts as well.

5.2. The importance of actLIe incestors

Although Jensens (1989) arguments are relevant for all LBOs, he focuses

on active investors and LB0 associations. The primary examples of these

organizations are LB0 partnerships and the merchant banking divisions of

investment banks and commercial banks. Accordingly, I classify the sample

LBOs as involving one of three types of buyout investors: LB0 partnership,

merchant banking division, and other. LB0 partnerships include Adler

Shaykin, Clayton Dubilier, Forstmann Little, Gibbons Green, Hicks & Haas,

Kelso, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts, Riordan Freeman, Thomas Lee, Warburg

Pincus, and Wesray. These organizations are devoted exclusively to arranging

LBOs. Merchant banking divisions of investment banks include Allen &

Company, Bankers Trust, Citicorp, Donaldson Lufkin Jenrette, First Boston,

Merrill Lynch, and Morgan Stanley. All other sample LBOs are classified as

other. These include LBOs organized entirely by management and by less

S.N. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

309

well-known LB0 partnerships. This classification, therefore, also distinguishes between the less well-known and the larger, better-known LB0

sponsors.

Panel B of table 8 shows the current private/public

status of LB0

companies by type of LB0 investor. A lower percentage of the LBOs

arranged by LB0 partnerships, 54.3%, are currently private while the percentage of LBOs arranged by merchant banks that are currently private,

70.8%, is slightly higher than the 64.0% for all others. None of the differences between any two of these groups, however, are significant at conventional levels. LBOs organized by well-known LB0 associations, therefore, are

no more likely to be permanent than are other LBOs.

5.3. DiGsions Cersus public companies

The sample includes approximately equal numbers of LBOs of divisions

and of public companies. Although it is possible that LBOs of the two groups

are driven by the same underlying causes, there are reasons that divisional

LBOs might be different. First, information differences between divisional

managers and parent-company managers are arguably smaller than those

between public-company managers and the stock market. The managers in

LBOs of public companies may be able to use their private information to

purchase the company at a price below its true value. If so, the gains in such

LBOs would come from information advantages rather than from any superiority of organizational form. If such differences are important, public companies should return to public ownership more often and more quickly than

divisional buyouts.

Alternatively, one could argue that the willingness of divisional managers

to do an LB0 indicates that they believe the parent corporation was

managing the business incorrectly. This is consistent with Kaplan and

Weisbach (forthcoming), who find that one common reason for divestitures is

that the divested division is not part of the parent companys core business.

Although the parent may understand this, it may be unable or unwilling to

sell the division to another company or to the public if the division has not

performed well recently. With a buyout, the parent gets a higher price, the

managers make the necessary changes, and then the buyout company returns

to public ownership. According to this view, divisional LBOs would be more

likely to return to public ownership than LBOs of public companies.

Panel C of table 8 presents the current private/public

status of both

divisional and public company LBOs. Slightly more public-company

LBOs - 65.9% - are still privately owned than divisional LBOs - 61.4%.

The difference, however, is not significant and does not indicate a strong

difference between divisional and public-company buyouts.

310

&V. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

Table 9

Ordinary-least-squares

and logit regressions of the probability that a leveraged buyout is publicly

owned as of August 1990 as a function of LB0 size, presence of LB0 partnership.

division or

public-company

status, and year of LB0 completion

for 170 leveraged buyouts valued at more

than $100 million and completed

in the period 1979-1986.

(Dependent

variable equals one if

LB0 company is publicly owned at the end of August 1990.)

(1)

Ordinary-leastsquares regression

Constant

$150 M to S244 M

$245 M to $459 Ma

At least $460 M

LB0 partnership

DivisionC

1981 and earlierd

1982

1983

1984

1985

Coeff.

SE.

Coeff.

-0.15

0.08

0.18

0.16

0.06

0.06

0.11

0.21

0.36

- 0.03

0.09

0.11

0.11

0.11

0.12

0.09

0.08

0.14

0.16

0.15

0.11

0.11

- 1.53

0.38

0.83g

0.74

0.28

0.29

0.49

0.91

1.56

-0 12f

0:39

170

0.07

No. of obs.

R/log-likelihood

(2)

Logit regression

S.E.

0.54

0.48

0.50

0.53

0.38

0.39

0.62

0.67

0.66

0.50

0.48

170

- 106.9

The variables $150 M to $244 M, $245 M to $459 M, and at least $460 M equal one if the

LB0 transaction

value falls in those ranges, and zero otherwise. The intercept refers to buyout

transaction

values of less than $150 M. These values divide the buyouts into transaction-size

quartiles.

bThe LB0 partnership

variable equals one if the LB0 is arranged by an LB0 partnership

and

zero otherwise.

The division variable equals one if the LB0 company is a division of another company and

zero if it is a public company before the LBO.

dThe variables

1982 to 1985 equal one if the LB0 is completed

in that year and zero

othetwise. The 1981 and earlier variable equals one for LBOs completed

in 1981 and earlier.

Significant

at the 1% level.

Significant at the 5% level.

Significant

at the 10% level.

5.4. Multicariate

estimates

The results in the previous subsections show that the current public/private

status of LBOs does not vary significantly by transaction value, by whether

the LB0 is organized by an LB0 partnership or a merchant bank, and by

whether the LB0 is of a public company or of a division. All three of these

are univariate results. Table 9 presents regression results that control for

these three types of variables and for the year the LB0 was completed.

Regression 1 is an ordinary-least-squares

regression in which the dependent

variable equals one if the LB0 is publicly owned at the end of August 1990

LV. Kaplan, The staying power of LBOs

311

and zero otherwise. This linear probability model is presented for ease of

interpretation. Regression 2 gives analogous estimates for a logit regression.

The multivariate results generally parallel the univariate results, except

perhaps for the role of transaction value. The two largest transaction-value

quartiles are, respectively, 18% and 16% more likely to be publicly owned

than LBOs in the smallest transaction-value quartile. The 18% value for the

third quartile is significant at the 10% level. Although the relationship

between transaction value and public/private

status is somewhat stronger

here than in the univariate analysis, it is still modest and only marginally

significant.

Consistent with the univariate results, regression 1 implies that LBOs of

divisions are no more likely to be publicly owned than LBOs of public

companies; and LBOs organized by LB0 partnerships are no more likely to

be publicly owned than other LBOs. The completion-year dummies have a

nonmonotonic pattern, with only LBOs completed in 1983 being significantly

different from the others. The 1983 LBOs are 36% more likely to be publicly

owned than LBOs completed in 1956.

Although not reported in the table, I also have estimated regressions that

control for (1) the industry of the LB0 at the two-digit SIC code level and (2)

post-buyout operating performance. The industry analysis uses dummy variables for the 15 two-digit SIC code industries that have at least three sample

LBOs. Only two of the coefficients for the industry variables are significant.

LBOs in rubber products WC code 30) and food stores (SIC code 54) are

more likely to be publicly owned. The results for the other variables are

qualitatively unaffected by the industry controls. Post-buyout performance is

measured as the percentage changes in operating income and operating

income to sales from the last pre-buyout year to the first or second post-buyout

year. These data are available for only 56 of the sample buyouts. None of

these performance variables is significantly related to buyout public/private

status.

6. Conclusion

This paper documents the organizational status over time of large leveraged buyouts (LBOs) completed between 1979 and 1986. As of August 1990,

62% of these LBOs are privately owned, 14% are independent public

companies, and 24% are owned by other public companies. As time since the

LB0 increases, the percentage of LBOs that have returned to public ownership increases. The (unconditional) median time an LB0 remains private is

6.82 years. These results and the time pattern by which LBOs return to

public ownership suggest that LBOs do not remain private permanently.

312

S..& Kaplan.

The sraying power of LBOs

These results are consistent with Rappaports view that buyouts are transitory organizational forms.

At the same time, the median life of 6.82 years implies that although LB0

organizations are not permanent, they are not short-lived. Furthermore,

private ownership is not the only distinguishing characteristic of an LB0

organization. The paper also considers post-buyout leverage and equity

ownership. LBOs that remain privately owned maintain debt levels similar to

the levels when the LB0 was completed. LBOs that are currently public,

both independent and purchased, maintain debt levels lower than the initial

LB0 levels, but higher than pre-buyout levels and median public-company

levels. The independent public LBOs also maintain relatively concentrated

equity ownership. These results are consistent with Jensens view and the

importance of long-term incentives.

The paper also finds a moderate role for asset sales to strategic buyers in

LBOs. Fewer than 29% of the LB0 companies and 34% of the original LB0

assets are owned by companies with other operating assets. This is much

lower than the 72% reported for hostile takeovers and somewhat lower than

the 43% reported for six LBOs by Bhagat et al. over a shorter period of three