Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Supply Chain Readings

Supply Chain Readings

Uploaded by

tobyfutureOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Supply Chain Readings

Supply Chain Readings

Uploaded by

tobyfutureCopyright:

Available Formats

TECHNOLOGY

ADVANTAGE

LINKAGE

EXPERTISE

LESSONS

THE POWERFUL

POTENTIAL OF DEMAND

MANAGEMENT

By Michael Shea and Berry Gilleon

Michael Shea (mshea@

grifjinstrategicadvisors.com) is

President o f Griffin Strategic Advisors

LLC. Bern Gilleon (hgilleon @

vikingrange.com) is Director o f

Procurement at Viking Range Inc.

T h e a b ility to see c u s to m e r

d em a n d and a lig n it w ith y o u r

su p p ly ch a in w h a ts ca lle d

d em a n d m a n a g e m e n t has

b e co m e a tru ly c ru c ia l c a p a b ility .

B u t m any su p p ly c h a in m a n ag ers

still s tru g g le w ith b u ild in g th is

c a p a b ility in th e ir o rg a n iz a tio n s .

A new survey u n co v e rs the

c h a lle n g e s th e y ty p ic a lly fa c e

and p o in ts to o p p o rtu n itie s fo r

s u c c e s s fu lly o v e rc o m in g th e m .

ow well does your organization do at demand man

agement, and in particular demand forecasting? The

answer to this question is central to supply chain

and business success. Proficiency in demand man

agement is absolutely critical in developing the right

relationships with suppliers, producing the right

amount of product at the right time, and forging a

mutually beneficial and profitable relationship with customers. For this

article and related survey, we see demand management as the process

of assessing customer demand and matching that demand with the

supply chain capability to deliver against it in a cost effective manner.

For the most part, we exclude demand management processes focused

on influencing demand.

(Tiffin Strategic Advisors recently conducted a survey among sup

ply chain professionals to determine the challenges and success they

have experienced with demand management activities. (For more

details on the survey, see accompanying sidebar on page 20.) Based on

the respondents collective experiences, we hoped to identify the state

of demand management today, the recurring challenges that need to be

overcome, and the best practices. From the findings, we also developed

what we hope are useful insights for taking demand management activ

ities to a higher level. Importantly, in developing the survey we sought

the input of the supply chain professionals themselves. The idea was to

ensure that we had a real-world orientation.

Our survey focused on these key areas of inquiry: (1) most impor

tant demand-management challenges facing companies; (2) demand

management integration with other related business systems; (3) best

practices in demand management; and (4) key issues around demand

forecast accuracy. We discuss each in turn below.

l.The Key Challenges

To put our discussion in a highly practical context, we wanted to learn

the most important demand-related challenges supply chain profes

sionals were experiencing today. Reflecting obvious concerns about the

effectiveness of their forecasting capabilities, respondents put the chal

lenges of long lead times, stock-outs, and excess inventory at the top

18

S L I P I . V C H A I N

M a \ AG K M K N I

R I:V I E W *

Ma y /J u NE 20 11

vvvvw. sc in r.c o m

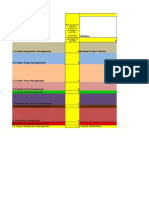

Single Most Important Demand Management Challenge

of the list (see Exhibit l). Two of the these top three

stock-outs and excess inventoryhave

direct financial

*

impact on organizations, either through the potential

loss of business (stock-outs) or the inefficient use of

capital (excess inventory). Long lead time, on the other

hand, is more of a cause than an effect. Specifically, long

lead time exacerbates the problems inherent in demand

management such as variation in demand and supply

and other external factors.

We probed further to determine the relative impor

tance placed on addressing the key challenges identi

fied. Stock-outs was considered to be the most pressing

issue, rated as very or extremely important by 79 percent

of respondents. Excess inventory and long lead times

followed closely at 71 percent and 67 percent respec

tively. There is some irony that stock-outs and excess

inventory lead the challenges, as they are diametrically

opposed in some sense. Isnt excess inventory the cure

for stock-outs? Such is the precarious balancing act we

vvvvvv.scm r.com

Long Lead Times

Stock-Outs

Excess Inventory

New Product Planning

Short Product Lifecycle

Obsolete Inventory

Other

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

call demand management.

We further asked the respondents to assess their

efforts at addressing the important challenges identi

fied. The results show that they were doing the best job

with regard to stock-outs and long lead times; 75 per

cent reported at least moderate success in tackling the

Su

ppl y

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v

ie w

M a y / J u n e 2c

19

Demand

stock-outs issue and 70 percent had a similar level of

success with lead times. Excess inventories proved to be

a slightly tougher challenge. Only 55 percent indicated

that they were moderately or extremely successful in

addressing that task.

2. Demand Management Integration

Systems integration is key to efficiently addressing the

kinds of challenges identified by our survey respondents.

Highly integrated systems allow companies to drive to a

one number state in which decisions made in the func

tional areas are all driven off a common data set. Other

benefits of integration include reduced manual transfer

of information from system to system, which has a posi

tive impact on speed and accuracy.

So we asked respondents how effectively their supply

chain activities were integrated with the demand man

agement software/systems. These software and systems

are used to manage information and form the basis of

planning, sourcing, producing, and delivering products.

The principal ones include demand management solu

tions, S&OP (Sales and Operations Planning), and ERF

(Enterprise Resource Planning). Survey participants

were asked to respond to these questions on integration

Slightly Integrated

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v ie w Ma y/Jl

ne

Degree of Integration: Supply Chain

Not At All Integrated

his survey was designed to gain an understanding of

current practices in demand management across a

broad spectrum of industries. The survey evaluated the

use of systems and their effectiveness, specific challenges

faced in demand management, and the degree of success

in tackling these challenges. It also sought to determine

the financial opportunity of improved demand manage

ment and to gauge the effect of the recent financial down

turn on demand management capability.

The survey attracted 190 respondents representing

companies in a wide variety of manufacturing and ser

vice industries. The respondents represented company

sizes from less than $100 million (25 percent) to greater

than $10 billion (13 percent). Every continent except

Antarctica is represented in the survey, with the majority

(70 percent) coming from the United States.The respon

dents represented all levels of the organization; 22 per

cent were at the vice president level or higher; 32 percent

at the director level; and 50 percent at the manager or

professional level. This diversity of roles and responsibili

ties among the participants enriched the follow-up discus

sions designed to elicit more specific understanding in key

areas.

Su ppl

EX HI BI T 2

and Demand Management System

Details o f the Demand

Management Survey

20

whether they were using an actual software package

or were performing these functions via a system" (for

example, meetings or spreadsheets). .Note that we were

not concerned with the specific type of solution or sys

tem, but rather with their integration with the supply

chain. In the vast majority of cases, though, respondents

were using software packages.

Integration proved to be somewhat problematical

across the different dimensions we measured. With

respect to the integration of the supply chain and the

demand management software/system, just under half of

the survey respondents reported that they were at least

moderately integrated. (See Exhibit 2.) Of that number,

however, only 6 percent considered their companies to

be "extremely integratedthe highest possible level of

integration. Most surprisingly, fully 25 percent said that

they were not at all integrated. T he findings indicate that

companies overall still have a long way to go on this key

integration activity. Effective supply chain management

requires and depends upon the outputs from demand

management.

2011

Moderately Integrated

Very Integrated

Extremely Integrated

Interestingly, the level of integration seemed to cor

relate positively with company size. For organizations

with annual revenues of less than S I00 million, the great

majority (around 72 percent) put their level of supply

chain-demand management integration as slight or non

existent; only 28 percent were moderately integrated or

better. For companies with annual revenues greater than

S50 billion, on the other hand, about 85 percent rated

themselves as moderately integrated or higher.

Integration of the demand management software

and S&OP is of fundamental importance, as the S&OP

process drives the execution of manufacturing and sales

activity. The needed integration could involve differ

ent modules of the same software package or separate

software solutions. Overall, the respondents reported

that the integration between demand management and

www. s c i t i r. c o in

Demand

S&OP was even less than that of the demand manage

ment software/systems and the supply chain. Only

15 percent said that the demand management-S&OP

integration was very integrated or extremely integrated.

( Phis compares to 20 percent for the supply chaindemand management integration reported at these high

levels.) We consider this finding particularly telling

because of the critical relationship that demand manage

ment has within the S&OP process.

to bring greater clarity to that distinction. In particular,

we looked for best practices in demand management in

such areas as metrics and incentives, customer involve

ment, and profitability.

As a backdrop to examining the best practices, let s

first look at some of the organizational issues surround

ing this activity. Demand management touches and

benefits other functions across the organizations entire

value chain But where does the ultimately responsibil

ity for demand management typically reside?

Our survey questionnaire gave respondents

the following possible choices: operations,

supply chain, sales, marketing, procurement,

from

and transportation/logistics. (See Exhibit 3.)

The survev results indicate that the

striving to achieve best practices in dem and

responsibility for demand management most

m anagem ent for greater profitability.

often resides in the supply chain function

as reported by one third of the respondents.

The next most reported function was opera

With regard to the necessary integration between tions (21 percent), followed by sales (18 percent), and

demand management and the ERP system, which forms procurement (14 percent). While these results may not

be surprising, it is clear that more companies view the

the overall architecture of the organizations core busi

ness functions, we again (bund only limited integration. activity of demand management as more of a supply

In fact, four out of five respondents reported that inte

chain or operations function than a pure sales function.

gration between demand management and ERP was

EX HI BI T 3

moderate at best (with 25 percent saying not at all).

Only 15 percent characterized their situation as very

Responsibility for Demand Management Process

integrated and a mere 5 percent as extremely integrated.

Again, this clearly points to an area of significant poten

tial improvement.

Supply Chain

Discussions with respondents and software suppliers

Operations

identified several factors that may help explain this relative

Sales

lack of integration. First, many companies ERP systems

Marketing

were installed with a strong focus on financial reporting

Procurement

and manufacturing, with demand management modules

either not purchased or activated. Second, demand man

Transportation

agement software systems often have been developed

Other

with an eye toward specific industry needs, retail demand

management being a good example. In general, getting

multiple systems to play well together in a seamless fash

As part of the organizational inquiry, we were espe

ion continues to challenge many companies.

cially/ curious about the interaction between demand

management and the procurement and the logistics/

3. Best Practices

transportation functions. (In our pre-research, a num

What currently constitutes best practices in demand ber of supply chain executives asked about this as well.)

management in a supply chain context? Almost by their Procurement and logistics play key roles in the suc

very- nature, best practices are relative rather than abso

cessful execution of demand management strategy. We

found that the interaction in both cases was relatively

lute. However, because they arise from the actual prac

titionersand the related processes, systems, and tools strongbut could be even stronger. Thirty percent of

that they usethe best practices are pragmatic and respondents reported that their purchasing function was

innately valuable. The trick is discerning common prac

very involved in demand management; for logistics/

tice from best practice. Our survey questions sought transportation the comparable number was 17 percent.

The important message here is

that everyone could benefit

22

Su ppl

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v ie w Ma y/Jl

ne

2011

www. s c i t i r. c o in

Demand

The majority of respondents characterized their involve

ment as moderate" with regard to both functions.

Companies would certainly benefit from a closer

integration between demand management and these two

functions. Regular input around supplier issues, capac

ity and mix, transportation or warehousing constraints,

for example, are invaluable for a solid demand plan.

Similarly, logistics needs accurate and timely input to

execute against the demand plan.

B est P ra c tic e : P erfo rm a n ce

M e tr ic s and S c o reca rd s

A recognized best practice of any supply chain improve

ment initiative are measures to gauge progress and to

incentivize the desired behaviors. As the saying goes,

What gets measured gets rewarded, and what gets

rewarded gets done." In that spirit, the survey asked if

companies had measurements (for example, scorecards)

and incentives around their demand management pro

cess, what were those metrics and incentives, and how

effective were thev.

Only about one fourth of the respondents surveyed

indicated that their companies had metrics for demand

management. The specific metrics mentioned most

often by this group focused on forecast accuracy, ontime delivery; and fill rate. Even fewer respondents (22

percent) have actually incorporated incentives into their

demand management process. The main incentive they

used was bonuses, with awards and salary increases a

distant second and third.

Among those respondents with demand manage

ment incentives in place, 42 percent rated them as veryeffective and another 46 percent called them moder

ately effective. These findings appear to make a strong

argument for using incentives as a best practice around

demand management. Its interesting that the great

majority of companies (80 percent) who did not have

demand management incentives felt that such incentives

would not be effective. So the logical questions become:

Have these companies tried incentives in the past but

were unhappy with the results? If they have never tried

incentives before, whats the reason for their pessimism?

In either case, they need to seriously consider the posi

tive response of those companies that have successfullyimplemented incentives.

j

Companies increasingly are adopting the practice of

using customer-provided forecasts, often as part of a for

mal customer relationship management (CRM) program.

We wanted to learn the extent to which this practice was

S l i m m .y C h a i n

Ma \

a g k m k n

I R i : v i i: w M

ay

/J

l n i:

EX HI BI T 4

Impact of Demand Management on Profitability

None

Up to 2%

2-4%

4-6%

6- 8%

8 - 10 %

B est P ra c tic e : C u sto m e r Involvem ent

24

being adopted, if the results were accurate, and whether

the sales or demand management function was the main

interface with the customer.

Half of the companies reporting said they did not use

a CRM system, 47 percent said they did, and 13 per

cent were not sure/did not know. Notably, the responses

showed a strong correlation between size of company

and CRM usage. In particular, companies with revenues

in excess of $2 billion are far more likely* to have a CRM

in place than companies under this revenue level.

Customer-provided forecasts on the whole were not

considered to be particularly accurate. Only 4 percent of

respondents said such forecasts were very accurate and

another 37 percent put them as moderately accurate.

(None said they were extremely accurate.) The remain

derclose to six of 10 respondentsviewed customerprovided forecasts as only slightly or not at all accurate.

This general characterization of customer-provided fore

casts holds true for all company sizes. Obviously, there is

significant room for improvement with regard to custom

er-provided forecasts. But based upon the survey results,

it would appear that the use of such forecasts in and of

themselves is not necessarily best practice.

Asked whether sales or demand management is

the main functional interface with the customer, more

respondents pointed to the former. Twenty-eight percent

said that the customer interface was completely through

sales, 27 percent said it was mostly through sales, and

28 percent said it was equally through sales and demand

management. By contrast, only 14 percent said the key

interface was mostly through demand management and

only 4 percent said it was completely through demand

management. This general pattern held true across all

company sizes.

2 01 1

Greater than 10%

Not Sure/Don't Know

30%

vvvvw. sc in r.c o m

In tern al and E xternal D ata S o u rce s

U sed in F orecasts

B est P ra c tic e : P ro fita b ility

From a purely business standpoint, perhaps that most impor

tant question of our survey asked about the perceived bottomline impact of using best practices in demand management.

We were surprised at the potential upside in profit indicated

by the respondents. Fully one fourth of them cited a profit

potential of greater than 10 percent through better demand

management. (See Exhibit 4.) Most respondents saw the

profit potential in excess of 4 percent, while fewer than one

in 10 put the potential margin improvement at 2 percent or

less. Interestingly respondents from smaller companies saw

a relatively greater profit potential in demand management.

The majority of respondents in the $2 billion and under cat

egory put the potential at 10 percent or more. (One executive

we interviewed told us that a demand management improve

ment project currently under way at his company will abso

lutely and significantly improve profitability.)

The findings point to a significant potential upside

that all companies should explore aggressively. The

important message here is that everyone could benefit

from striving to achieve best practices in demand man

agement for greater profitability. I bis finding obviously

merits further study to better understand in more detail

what needs to be done to uncover this potential profit,

the difficulty* and cost associated with that effort, and

bow to sustain the results.

Companies use a variety of internal data sources in devel

oping their forecasts. The most common data source was

customer ordersmentioned by close to three out of

four respondents. Another common data source comes

from customer shipments, reported by 42 percent. Point

of sale (POS) data has become an increasingly impor

tant source of forecast data as well. Close to one third

of respondents now say that these use POS data to help

drive their demand forecasts.

The use of POS data was not concentrated in any

particular business sector. However, we did see a cor

relation between the use of POS data and the level

of demand management systems integration. Of the

responding companies using POS data, 31 percent said

that they were very or extremely integrated; this com

pares to only 12 percent at this integration level among

companies not using POS data. Further, over 60 percent

of companies using POS data for forecasting rated their

demand systems integration to be moderately integrated

or better, compared to only 31 percent for the non-users.

External sources of data are also extensively used in

demand forecasting. Among the most commonly used gener

al indicators were the Consumer Price Index, Gross National

Product Growth, and the Consumer Confidence Index.

About one quarter of the respondents use industry-specific

indices or other information sources. As would be expected

given the number of industries represented in the survey,

these more specific indicators were far-rangingeverything

from hotel occupancy rates and import data to intuition.

4. Demand Forecast Components

Beyond the integration and best practice issues, the

survey sought to identify the key components asso

ciated with demand management forecast accuracy.

Specifically, we looked at frequency of forecast updates,

internal and external data sources used, forecast accu

racy and related impacts, and responsiveness of demand

management systems.

F orecast A c c u r a c y M e th o d U sed

Understanding the accuracy of any given demand forecast

is as important as conducting the demand forecast itself.

Determining forecast accuracy is the first step in a continu

ous improvement cycle that drives higher forecast accuracy.

The survey revealed that a high percentage of respondents

do measure their forecast accuracy using recognized statis

tical measures. Mean Absolute Percent Error (MAPE) was

the most popular measure (used by 47 percent of respon

dents), followed by Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD),

vvhich was used by 37 percent. Several respondents also

used bias and Weighted Absolute Percent Error (VVAPE).

Approximately one of 10 respondents said that their com

pany did not measure the accuracy of their forecasts.

F requ en cy o f D em a n d F o reca st U p d ates

First, we wanted to determine how frequently the demand

forecast data was updated. By far the most common fore

cast cycle was monthly (42 percent of respondents).

Weekly was next, reported by 18 percent, followed by

daily (13 percent), and quarterly (9 percent). One respon

dent told us that his company also updates their forecast

when there are serious management problems.

No clear correlation emerged between the fore

cast update cycle length and the specific industry of

the participant. For example, retailers generally did not

have more or less frequent forecast updates than, say,

respondents in the manufacturing sectors. Similarly, we

observed no correlation between frequency of update

cycle and level of systems integration.

vvvvvv.scm r.com

R esp on siven ess and Sensitivity o f

D em an d M a n a g e m e n t S o ftw a re /S y stem

The more sensitive and responsive a forecast is to trends,

the more value it has to supply chain management. The

Su

ppl y

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v

ie w

M a y / J u n e 2011

25

Demand

ability to rapidly detect changes in demand gives compa

nies greater flexibility to accommodate changes, or influ

ence overall demand. Most respondents clearly are not

satisfied with the ability of their demand management

systems to forecast short-term trends. Well over half of

those surveyed rated their demand management system

as either not at all or only slightly responsive to short

term trends, while only 20 percent described their sys

tem to be very or extremely responsive.

Most companies attempt to influence demand through

demand-shaping activities such as sales promotions or

new product introductions. A key question here, however,

is how accurately can the results of these demand shaping

activities be measured and can their effects be separated

from other sources of variation? Clearly, companies would

benefit from understanding the results of these activities.

For example, how much sales lift could come from a 15

percent discount? Does a 15 percent discount result in

more operating profit than a 10 percent discount?

The survey results show that most respondents

would have a difficult time answering these types of

questions. Fully 37 percent rated their systems as not at

all effective in measuring the impact of their demand

shaping activities. Another 2 percent rated their systems

as only slightly effective. At the other end of the spec

trum, 10 percent of respondents said their systems were

very effective at measuring demand-shaping initiatives.

(See Exhibit 5).

Im p a ct o f F o recast A c cu ra cy

Lead-time variability is an often cited detriment to

demand forecast accuracy. The negative impacts

which include supply chain risks and costsextend

across inventory management, logistics, engineering/

design changes, and new product development. In our

pre-survey research, the supply chain professionals

expressed to us their concern about lead time variability

EX H IB I T 5

Effectiveness of Demand Shaping

Very Effective

Not At A ll Effective

Moderately Effective

Slightly Effective

26

Su ppl

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v ie w Ma y/Jl

ne

2011

and asked us to quantify the related impacts in the sur

vey questionnaire.

Not surprisingly, we did find a strong statement of

impact from our respondents. Almost half (49 percent)

said that lead-time accuracy had a very important or

extremely important impact on demand forecast accu

racy. The remaining respondents were roughly equally

divided between moderate impact and slight or no

impact.

Biaspersistent under- or over-forecastingis anoth

er common problem for demand managers. Many of the

causes of bias are rooted in company culture and expec

tations (for example, unbridled optimism or persistent

pessimism). For those responsible for managing supply

chains, bias can be especially frustrating, resulting among

other things in repetitive stock-outs or excessive inven

tory Survey respondents considered bias to be a recurring

problem that seriously impacted demand management

performance. More than 45 percent found bias to be

either very or extremely impactful on inventory' levels or

fill rates. Only 5 percent of respondents felt that bias was

not a factor in inventory' levels or fill rates.

Im p act of E c o n o m ic R e c e ssio n on

F orecast A c c u r a c y

With the recent economic downturn and recovery in its

early stages, many companies have experienced extreme

shifts in demand. Often these shifts are overstated at any

given point in the supply chain because of the effects

of de-stocking/re-stocking, also known as the Bullwhip

Effect. We wanted to learn just how well demand man

agement systems performed in this unstable period.

The results were not particularly encouraging. A

majority (61 percent) of the respondents described their

systems as either not at all or only slightly responsive

to the recent economic volatility. And while 26 per

cent of the respondents rated their systems as moder

ately responsive, only 12 percent considered them to

be either very or extremely responsive. Not surprising

ly, then, when asked how overall forecast accuracy has

been affected by the current period of economic vola

tility, 41 percent of respondents felt that their forecast

accuracy had decreased while only 29 percent said it had

improved. (See breakdown in Exhibit 6.)

The responses to this question indicate that there is

still room for improvement and lessons to learn in terms

of minimizing the impact from future economic down

turns. lo be better prepared for future economic volatility,

companies could consider a couple of actions to improve

demand management processes. First, they could improve

sensitivity to leading indicators of upcoming demand

j

www. s cm r.c o m

that can flow from effective demand management? The

survey results lead us to a few key recommendations.

1. Get belter organized. Migrate to an organization

with a comprehensive supply chain view as opposed to

a functional view (of procurement, transportation, sales,

and so forth). Our survey showed that many compa

nies do not fully integrate or engage the various func

tional areas of the supply chain to effectively maximize

the value that can be delivered through capabilities like

demand management.

2. Make your systems and processes work for you.

Improve system and process integration. The objective

here is to use common information across the organiza

tion so that all team members are driving to the same

outcome. Note that we have no preference toward par

ticular software or systems. The key for improvement

is ensuring the use of consistent information across the

organization.

EX H IB I T 6

Economic Impact on Forecast Accuracy

Increased Significantly

Decreased Significantly

Increased Slightly

Decreased Slightly

No Change

shifts in order to give themselves better visibility and

time to adapt. Second, they could shorten their sup

ply chain in order to lessen the time needed to adapt to

demand changes. Moving from low cost country sourc

ing to near-shoring would be an example of this.

Finally, we looked at the types of demand manage

ment soft ware/systems in place to help companies with

their forecast accuracy. SAP was the provider mentioned

by most respondents at 39 percent, followed by Oracle/

People Soft/JD Edwards at 16 percent. Others solutions

providers mentioned included i2 Technologies, Logility,

JDA, and Infor. Variations of proprietary/in-house/custom software accounted for about 9 percent of the com

panies surveyed.

Asked about the effectiveness of these software pack

ages in managing demand, 20 percent said they were

extremely effective; 39 percent said moderately effec

tive; and 41 percent slightly or not at all effective. (See

Exhibit 7.) Larger companies in general tended to rate

the effectiveness of the soft ware/systems higher than the

smaller companies.

EX HI BI T 7

Rating Effectiveness of Software Packages

0%

3. Incorporate multiple inputs in managing demand.

Develop a robust forecasting and demand management

process that uses multiple inputs including history,

trends, external and internal data. (The survey made it

pretty clear that customer-provided forecasts alone may

not be the answer.) Incorporating multiple inputs will

pay dividends by addressing the key demand manage

ment challenges identified in the survey: stock-outs and

excess inventory*

4. Use metrics and incentives. Create metrics in such

areas as forecast accuracy, on-time deliver}; and fill rate

to gauge the effectiveness of your demand management

activities. Then build incentives that encourage people

to excel against those key metrics. The survey results

strongly support that creation of metrics and incentives

as a best practice in demand management, c ia o

C ap tu rin g the O p p o rtu n itie s

Our survey identified a host of potential benefits from

the successful implementation and integration of

demand management processes. Certainly, one of the

most significant of those is the profit potential from

demand management best practices identified by our

respondents. As we noted earlier, over 25 percent said

that better demand management could increase the

overall profitability of their organization by more than 10

percent.

What steps can companies take to begin capturing

the significant profit opportunities and other advantages

vvvvvv.scm r.com

5% 10% 15% 20% 25% 30% 35% 40%

Su

ppl y

Cha

in

Ma

n a g emen t

Re v

ie w

M a y / J u n e 2c

27

You might also like

- Process Group and Knowledge Area Interaction - Excel TemplateDocument4 pagesProcess Group and Knowledge Area Interaction - Excel TemplateHaroon Ahmed0% (1)

- Real-Time Data Analytics Case StudiesDocument37 pagesReal-Time Data Analytics Case StudiesHarrison HayesNo ratings yet

- SJC Cost Book May 19Document236 pagesSJC Cost Book May 19Dibyendu DuttaNo ratings yet

- Sop PDFDocument15 pagesSop PDFpolikopil0No ratings yet

- 2012 Compliance StudyDocument24 pages2012 Compliance StudyMarc BohnNo ratings yet

- ADL Worldclass Purchasing PDFDocument4 pagesADL Worldclass Purchasing PDFQuentin MazuyNo ratings yet

- EquaSiis Market Assessment, Outsourcing Governance Operational Efficiency, May 2009 (E2002)Document13 pagesEquaSiis Market Assessment, Outsourcing Governance Operational Efficiency, May 2009 (E2002)StinkyNo ratings yet

- GEP Value Trends: Procurement Strategy Industry Trends and ImplicationsDocument17 pagesGEP Value Trends: Procurement Strategy Industry Trends and ImplicationsDanyal ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Covid19 Impact On Digital Transformation IndustryDocument6 pagesCovid19 Impact On Digital Transformation IndustryMustafa MowafyNo ratings yet

- Mastering Strategy: Financial TimesDocument9 pagesMastering Strategy: Financial TimesValmir Maia Meneses JuniorNo ratings yet

- WP 1032 Wholesale Distribution Outlook 2014Document14 pagesWP 1032 Wholesale Distribution Outlook 2014Bogdan GrosuNo ratings yet

- Beyond ERP SCM: Supply-Chain AnalyticsDocument16 pagesBeyond ERP SCM: Supply-Chain AnalyticsBryan RollinsNo ratings yet

- In Supply Chain Planning: 2021: Digital TransformationDocument13 pagesIn Supply Chain Planning: 2021: Digital TransformationVineet MishraNo ratings yet

- Consumer Complaints ReportDocument16 pagesConsumer Complaints ReportEY VenezuelaNo ratings yet

- Superior Performance With S&OP PDFDocument14 pagesSuperior Performance With S&OP PDFmshantiNo ratings yet

- Delottite CPO SurveyDocument15 pagesDelottite CPO SurveyShareen LeeNo ratings yet

- AST-0060828 Improving Sales Effectiveness in A Buyers MarketDocument12 pagesAST-0060828 Improving Sales Effectiveness in A Buyers MarketLuis Jesus Malaver GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Us Deloitte Global Treasury Survey 2022Document22 pagesUs Deloitte Global Treasury Survey 2022kirill.barkhatovNo ratings yet

- CFO To Chief Future OfficerDocument24 pagesCFO To Chief Future OfficerSuccessful ChicNo ratings yet

- BDP International and Centrx - Managing Your International Supply Chain - The Affects of The RecessionDocument8 pagesBDP International and Centrx - Managing Your International Supply Chain - The Affects of The RecessionadipressoNo ratings yet

- Management Tools & Trends - Bain & CompanyDocument20 pagesManagement Tools & Trends - Bain & CompanyTeuku YusufNo ratings yet

- Information Management in Financial ServicesDocument18 pagesInformation Management in Financial Servicesf1sh01No ratings yet

- Measuring Innovation 2009Document17 pagesMeasuring Innovation 2009rataNo ratings yet

- PWC - SCM - NEXT GENDocument19 pagesPWC - SCM - NEXT GENPartha Patim GiriNo ratings yet

- The Outsourcing Vendor Management Program Office (VMPO) : Art, Science, and The Power of PerseveranceDocument36 pagesThe Outsourcing Vendor Management Program Office (VMPO) : Art, Science, and The Power of Perseverancevir_4uNo ratings yet

- Us M&A Trends ReportDocument45 pagesUs M&A Trends ReportAnushree RastogiNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Growth, Short-Term Differentiation and Profits From Sustainable Products and ServicesDocument12 pagesLong-Term Growth, Short-Term Differentiation and Profits From Sustainable Products and ServicespauldupuisNo ratings yet

- Selling in Turbulent TimesDocument24 pagesSelling in Turbulent TimesBogdanNo ratings yet

- PWC Global Supply Chain Survey 2013Document19 pagesPWC Global Supply Chain Survey 2013mushtaque61No ratings yet

- SCM AssignmentDocument8 pagesSCM AssignmentDe BuNo ratings yet

- InterSearch-Global Board Survey 2015Document16 pagesInterSearch-Global Board Survey 2015Ana BerNo ratings yet

- 2003 - SurveyofMgtAccting EYDocument24 pages2003 - SurveyofMgtAccting EYRiaz Rahman BonyNo ratings yet

- Total Quality Management Assignment June 2023Document14 pagesTotal Quality Management Assignment June 2023Kumar DiwakarNo ratings yet

- Key Drivers For Modern Procurement 1Document22 pagesKey Drivers For Modern Procurement 1setushroffNo ratings yet

- Planning: Foundation of Strategy: Reporter: Chiara Mari S. Manalo Subject: BA 108 - Business PolicyDocument34 pagesPlanning: Foundation of Strategy: Reporter: Chiara Mari S. Manalo Subject: BA 108 - Business PolicyChiara Mari ManaloNo ratings yet

- Aberdeen CHR Strategic Sourcing OrganizationDocument10 pagesAberdeen CHR Strategic Sourcing OrganizationWilson CasillasNo ratings yet

- Technology Development in 2012 PDFDocument13 pagesTechnology Development in 2012 PDFsivaganesh_7No ratings yet

- Supply-Chain and Logistics Management FOR Creating A Competitive Edge Part OneDocument21 pagesSupply-Chain and Logistics Management FOR Creating A Competitive Edge Part OneNixon PatelNo ratings yet

- Supply ChainDocument38 pagesSupply ChainJames Euler Villar EstradaNo ratings yet

- 2012 Sales and Operations PlanningDocument14 pages2012 Sales and Operations PlanningSachin BansalNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Procurement Ivalua ReportDocument7 pagesSustainable Procurement Ivalua ReportbusinellicNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Territory Design PDFDocument10 pagesThe Importance of Territory Design PDFCaleb ChaseNo ratings yet

- Strategic Sourcing: Lessons Learned: Report HighlightsDocument11 pagesStrategic Sourcing: Lessons Learned: Report HighlightsAron Ruben Flores ZarzosaNo ratings yet

- 2021-3579-fnd Supply Chain Risk Management-Report HighresfinalDocument16 pages2021-3579-fnd Supply Chain Risk Management-Report HighresfinalAbdel Ghader Oumar M'HayhamNo ratings yet

- Financial Close Benchmark ReportDocument26 pagesFinancial Close Benchmark ReportNam Duy VuNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain Management Assignment ExampleDocument7 pagesSupply Chain Management Assignment ExampleExpert Writing HelpNo ratings yet

- IM - Executive RIM Whitepaper - Gens and Associates - V - Fall 2012 EditionDocument19 pagesIM - Executive RIM Whitepaper - Gens and Associates - V - Fall 2012 Editionpedrovsky702No ratings yet

- Winning in A Business 4 0 World PDFDocument56 pagesWinning in A Business 4 0 World PDFLap Pham100% (1)

- Quality Management, 3 RD Smester-2Document21 pagesQuality Management, 3 RD Smester-2Syed Umair RizviNo ratings yet

- Macalinao, Rica Princess L. Project BackgroundDocument5 pagesMacalinao, Rica Princess L. Project BackgroundRica Princess MacalinaoNo ratings yet

- Competitive Advantage and Internal Organizational AssessmentDocument12 pagesCompetitive Advantage and Internal Organizational AssessmentVish VicNo ratings yet

- S&OP SCM WorldDocument18 pagesS&OP SCM Worldharis_ikram_51281621100% (1)

- Applying The Principles of Supplier Relationship Management To Human CapitalDocument9 pagesApplying The Principles of Supplier Relationship Management To Human CapitalValeriano KatayaNo ratings yet

- The Why, What and How of Supplier ManagementDocument8 pagesThe Why, What and How of Supplier ManagementZycusInc100% (1)

- Survey On Corporate Investment Practices in NepalDocument12 pagesSurvey On Corporate Investment Practices in NepalkapildebNo ratings yet

- The Top 25 Supply ChainsDocument10 pagesThe Top 25 Supply ChainsFarrukh AbbasNo ratings yet

- The Need For Smart Enough Systems: Chapter OneDocument30 pagesThe Need For Smart Enough Systems: Chapter OneRadu MarinescuNo ratings yet

- Custom Research: Trade Promotion ManagementDocument10 pagesCustom Research: Trade Promotion Managementpellicani9683No ratings yet

- Us Fas Sanctions 5 Questions 052215Document2 pagesUs Fas Sanctions 5 Questions 052215boyohe3171No ratings yet

- Winning the Cost War: Applying Battlefield Management Doctrine to the Management of GovernmentFrom EverandWinning the Cost War: Applying Battlefield Management Doctrine to the Management of GovernmentNo ratings yet

- Setting Up A Retail OrganizationDocument15 pagesSetting Up A Retail OrganizationSumantra BhattacharyaNo ratings yet

- Jonble-Hangzhou Maibang Technology Co.,LtdDocument2 pagesJonble-Hangzhou Maibang Technology Co.,LtdCarlosSánchezNo ratings yet

- Presentation On PRINCE 2 Project Management MethodologyDocument14 pagesPresentation On PRINCE 2 Project Management MethodologyEmmanuel Mends FynnNo ratings yet

- Group Research On Flipkart by Group 1Document23 pagesGroup Research On Flipkart by Group 1Bhavya BansalNo ratings yet

- Types of DecisionsDocument2 pagesTypes of DecisionsKirti Chandna100% (4)

- Zara Supply ChainDocument30 pagesZara Supply ChainUpasna HandaNo ratings yet

- Managerial Economics NotesDocument66 pagesManagerial Economics Notesrajeshwari100% (3)

- Topic 9 Case Study ADM510Document2 pagesTopic 9 Case Study ADM510haha kelakarNo ratings yet

- The Role of The HR Controlling in The Human Resource management-PhD Thesis PDFDocument24 pagesThe Role of The HR Controlling in The Human Resource management-PhD Thesis PDFAakanksha ChauhanNo ratings yet

- VP Finance Controller Accounting in San Diego CA Resume Paul KlingenbergDocument2 pagesVP Finance Controller Accounting in San Diego CA Resume Paul KlingenbergPaulKlingenbergNo ratings yet

- Unec 1701176528Document32 pagesUnec 1701176528Ber BezekNo ratings yet

- Business Leader Mr. Narayana MurthyDocument23 pagesBusiness Leader Mr. Narayana MurthyNidz BhatNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument24 pagesTheoretical FrameworkRafi DawarNo ratings yet

- Glossary of Project Management Terms & Acronyms PDFDocument8 pagesGlossary of Project Management Terms & Acronyms PDFzaeem_sidd5291No ratings yet

- Implementing Absence ManagementDocument184 pagesImplementing Absence ManagementmoslemksaNo ratings yet

- How Should Companies Interact in Business NetworkDocument26 pagesHow Should Companies Interact in Business NetworkMegat Shariffudin Zulkifli, DrNo ratings yet

- ANTENOR 10-Pages PublishableDocument10 pagesANTENOR 10-Pages PublishableMary Ann AntenorNo ratings yet

- CLASS XII Hui170727 - 0000.pdf - 20240524 - 184720 - 0000Document27 pagesCLASS XII Hui170727 - 0000.pdf - 20240524 - 184720 - 0000Sukhmeen KaurNo ratings yet

- CE3034E - Disaster Management - Syllabus NewDocument1 pageCE3034E - Disaster Management - Syllabus NewPrateek NegiNo ratings yet

- ELTU2012 - 1b - Job Application Letters (Student Version) - August 2017Document22 pagesELTU2012 - 1b - Job Application Letters (Student Version) - August 2017Donald TangNo ratings yet

- AligningIT PDFDocument13 pagesAligningIT PDFshenero1No ratings yet

- Pd2 May16 External PM ReportDocument5 pagesPd2 May16 External PM ReportNyeko Francis100% (1)

- Four Key It Service Management FrameworksDocument12 pagesFour Key It Service Management FrameworksChristianAntonioNo ratings yet

- Information Systems: Presented By: Neeraj Kumar Jain Institute of Technology & Science Mohan NagarDocument25 pagesInformation Systems: Presented By: Neeraj Kumar Jain Institute of Technology & Science Mohan Nagarpreetim1980No ratings yet

- PrinciplesofManagement (3rd Edition) - SampleDocument32 pagesPrinciplesofManagement (3rd Edition) - SampleVibrant Publishers100% (1)

- MATRIXDocument5 pagesMATRIXSerchecko JaureguiNo ratings yet

- Project RISEDocument2 pagesProject RISEvina theresa celzoNo ratings yet

- TC FC + (VC × Q) : Supply ChainDocument3 pagesTC FC + (VC × Q) : Supply ChainJeNo ratings yet