Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Assessing The Implementation of Inclusive Education Among Children and Youth With Special Needs

Assessing The Implementation of Inclusive Education Among Children and Youth With Special Needs

Uploaded by

Amadeus Fernando M. PagenteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assessing The Implementation of Inclusive Education Among Children and Youth With Special Needs

Assessing The Implementation of Inclusive Education Among Children and Youth With Special Needs

Uploaded by

Amadeus Fernando M. PagenteCopyright:

Available Formats

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Assessing the Implementation

of Inclusive Education Among

Children and Youth with Special Needs

Olive Joy F. Andaya1

Adelaila J. Leao

andaya.ojf@pnu.edu.ph

leao.aj@pnu.edu.ph

Leticia N. Aquino

Richmond Zito T. Maguigad

aquino.ln@pnu.edu.ph

maguigad.rz@pnu.edu.ph

Marites A. Balot

Carlito G. Miguel

balot.ma@pnu.edu.ph

miguel.cg@pnu.edu.ph

Nicette N. Ganal

Donna B. Remigio

ganal.nn@pnu.edu.ph

remigio.db@pnu.edu.ph

Philippine Normal University

The Indigenous Peoples Education Hub

North Luzon Campus

ABSTRACT The study assessed the implementation

of Inclusive Education among children and youth with

special needs. It investigated how well the school

maintains the salient features of Inclusive Education,

how well it addresses the basic concern of parents of

non-disabled students, the inclusion potential benefits;

and how adequately key persons carry out their roles

during phases of implementation. In using the descriptive

method, 2 of the 3 administrators, 13 regular teachers,2

SPED teachers and 713 parents of disabled and nondisabled children from selected schools in Isabela were

considered. Checklist, guided interview/focused group

discussion, observations, weighted mean and standard

deviation were utilized. Overall computed mean of salient

features-2.76; potential benefits-2.97, and carrying out

of key persons roles-2.97, prove that implementation is

evident. Concerns of parents of non-disabled were less

Suggested Citation: Andaya, O.J. et al. (2015). Assessing of the Implementation of inclusive Education

Among Children and Youth with Special Needs . The Normal Lights, 9(2), 72 89.

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

evident with overall computed mean of 2.29. Results

imply provisions of appropriate materials, equipment, inservice trainings, medical data to determine impairment

categories/levels of special child; and Individualized

Educational Programs (IEP).

Keywords: Assessment, Children and Youth with Special

Needs, Implementation, Inclusive Education

Introduction

Special Schools alone can never achieve the goal of

Education for All (EFA) (Rocal, 2011). Participants of

the 1994 Conference on Special Needs education held in

Salamanca, Spain issued this statement and reaffirmed the

right to education of every individual, as enshrined in the 1984

Universal Declaration of Human Rights. This reaffirmation

served as renewal of pledge of the world community at the

1990 World Conference on Education for All (EFA), 2007.

Hence, the Department of Education (DepEd) adopted policy

of Inclusive Education as a basic service for all types of

exceptional children and youth; a handbook on Inclusive

Education as primary reference and guide for Special

Trainings and promotion of the ideas (Inciong, et.al., 2007).

The term inclusion, according to Farrell (2005), is

to establish understanding of concept between inclusion and

integration. Mainstream school systems remain the same, but

extra arrangements are made to provide for pupils with special

educational needs. Farrell (2005) further cited inclusion as

securing appropriate opportunities for learning, assessment

and qualifications enabling full and effective participation

of all pupils in the learning process. (Wade, 1999). Inciong,

et.al (2007), describe inclusion as the process by which a

school accepts children with special needs for enrolment in

regular classes where they can learn side by side with their

73

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

peers; arranges its special education program which involves

a special education teacher as one of the faculty members.

The school offers mainstream where regular and special

education teachers organize and implement appropriate

programs for special and regular students.

Farrel (2005) identified three aspects of inclusion: 1)

Social inclusion; 2) including pupils with special educational

needs already in mainstream school; and 3) balance of

pupils in mainstream and special schools. As a strategy,

social inclusion is likely to raise more standards pupil with

SEN (Special Education Needs) attains when in school than

when not educated at all. Included in the second thread are

pupils with (SEN) already enrolled in mainstream schools,

an approach that seems to be the purpose of documents on

inclusion of all those connected with the school, adults as

well as children, not only pupils with SEN. It addresses

three dimensions of schooling: a) creating inclusive cultures,

b) producing inclusive policies, and c) evolving inclusive

practices. (Booth, Ainscow & Black-Hawkins, 2000). The

third aspect of inclusion may result in increasing proportion

of pupils in mainstream schools with reference to specialist

provision or a pupil referral unit. No pupils would be

educated in special schools or other settings; and all pupils

with Special Educational Needs (SEN) would be educated in

mainstream schools.

A range of provision which Special Educational

Needs (SEN) could be met (such as mainstream school,

special school, pupil referral unit, home tuition) would not

be acceptable. Better yet, to have increased support and

resources in mainstream schools in proportion to the severity

and complexity of SEN (e.g., Gartner & Lipsky, 1989).

Farrel (2005) presents the document,Inclusive

Schooling: Children with Special Educational Needs,

Department for Education and Skills (DfES 2001b) provides

74

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

statutory guidance on the framework for inclusion within

the Education Act 1996. The Special Educational Needs and

Disability Act 2001 is said to deliver a strengthened right

to mainstream education for children with special needs by

amending the Education Act 1996. The law concentrates on

two aspects of the document: 1) The first concerns interface of

this right with the right of parents to express a preference

for school for their child 2) The second is the constrained

nature of right to inclusion apparent in the document.

The act seeks to enable more children

who have special education needs to be included

successfully within mainstream education. This

clearly signals that where parents want a mainstream

education for their child everything possible should

be done to provide it. Equally, where parents want a

special school place their wishes should be listened

to and taken into account (London, Department for

Education and Skills, 2001b).

Heubert (1994) outlines some of the major

philosophical assumptions that proponents and opponents

hold relative to their attitudes about inclusion. Those who

favor greater inclusion consider labeling and segregation of

students with disabilities as unfavorable. They do not view

these students as distinctly different from others, but only

have limitations in terms of abilities. They also believe that

students who are disabled can be best served in mainstream

classes because: teachers who have only low-ability students

have lower expectations; students in segregated programs tend

not to have individualized programs; most regular teachers

are willing and able to teach students with disabilities; and

the law supports inclusive practices. Whitbread (2014)

mentioned that education is the most important function

of the state and local government, a principal instrument

in awakening the child to cultural values, in preparing him

75

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

for later professional training, and in helping him adjust

normally to his environment. We conclude that in the field,

the doctrine separate and equal has no place. These same

arguments, originally applied to race, have been repeated on

behalf of children with disabilities, many of whom continue

to be educated separately from their non-disabled peers

despite legislation mandating otherwise (U.S. Department

of Education, 2003). In fact, as cited by Whitbread (2014),

children with intellectual disabilities educated in general

education settings have been found to score higher on literacy

measures than those educated in segregated settings (Buckley,

2000). Student academic achievement is higher when parents

are involved; the higher the level of parent involvement, the

higher the level of student achievement (Henderson & Mapp,

2002); (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001).

The Legal Mandate of Inclusive Education declares

basic right of every Filipino child with special needs to

education, habilitation, rehabilitation, support, training and

employment opportunities, community participation, and

independent living.

In the Philippines, the legal mandates of Inclusive

Education are anchored on The world declaration on

Education for All (EFA) held in Jomtiem, Thailand in March,

1990, giving primacy for expanded vision and a renewed

commitment to provide basic education to all children, youth

and adults (Rocal, 2011). Other legal mandates where Inclusive

Education is anchored include: 1)The World Conference on

Special Needs held at Salamanca, Spain on June 7, 2012,

recognizing necessity and urgency of providing education

for children, youth and adult with special educational needs

within the regular educational system; 2) The Agenda for

Action of Asian and Pacific Decade of Disabled Persons.

(1993-2002) declares that all children and young people have

the right to education, equality, opportunities and participation

in the society; 3) The Philippine Action Plan (1990-2000)

76

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

in support of EFA focused its policies and strategies to

specific groups of people: rural poor, those in urban slums,

cultural communities, disabled, educationally disadvantaged,

and the gifted; 4) Republic Act 7277, otherwise known as

Magna Carta for Disabled Person enacted in July 1991 and

approved 1995, upholds full participation, total integration,

protects and promotes independence and respect of persons

with disabilities.

Inciong et.al,. (2007) cited that the Special Education

Division of the Department of Education takes charge of all

programs and services in the country. It has the following

functions: 1) formulates policies, plans and programs 2)

develops standards of programs and services; 3) monitors and

evaluates efficiency of program and services; 4) conducts inservice training programs to upgrade competencies of SPED

administrators, teachers, and ancillary personnel; and 5)

establishes and strengthens linkages and network.

The Philippine Normal University, a leading Teacher

Education institution, strongly supports the promotion of

SPED. Its Research Agenda include assessing or evaluating of

implementation of SPED programs and services in the nearby

public or private schools in its area of responsibility. One of

these research agenda is the Assessment of the Implementation

of Inclusive Education of Children and Youth with Special

Needs. As advocates, the researchers embarked on this task

for they strongly believed that findings may help SPED

School Administrators, Regular Teachers, SPED Teachers and

parents strengthen their Inclusive Education Program.

The present study assessed the implementation of

Inclusive Education for children with special needs. Primarily,

it investigated: 1) to what extent are salient features of

Inclusive Education evident and maintained; 2) to what extent

does the school addresses the basic concerns of parents of

non-disabled students; 3) to what extent are potential benefits

77

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

of Inclusion evident or manifested in inclusive schools; and 4)

to what extent do Inclusive Education key persons carry out

their roles during the phases of implementation of inclusive

education: Administrator/Regular Teacher, SPED Teacher,

Parents. Involved in the study are school administrators,

regular teachers, SPED teachers, parents of special children

and youth and non-disabled children or youth (where the

special ones are mainstreamed) in selected mainstreamed

public schools in the Isabela, Northern Philippines.

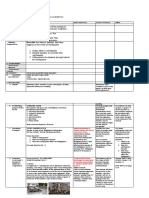

INPUT

PROCESS

1. Salient Features of

Inclusive Education

2. Basic Concerns of

Parents of Non-disabled Students

3. Noted/Potential

Benefits of Inclusion

Assessment of

the Implementation of Inclusive

Education among

Special Children

4. Key Persons Roles

during the Phases

of Implementing

Inclusive Education

OUTPUT

Increased Awareness among

School Administrators, Regular

Teachers, SPED Teachers and

Parents of Implementing Inclusive Education among Children

with Special Needs

Improved Plan for the Implementing of Inclusive Education

Based on their Strengths and

Weaknesses

Adequate Provision for the

Successful Implementation of

Inclusive Education

Figure 1. Research Paradigm

Methodology

Using the Descriptive method, the study involved two (2) of

the three (3) school administrators, thirteen (13) randomly

selected regular teachers, two (2) Special Education teachers

and 26 parents of disabled children and 187 parents of nondisabled children comprising the population from selected

schools in Isabela where inclusive education is fully

implemented. A research instrument or checklist to assess the

implementation of inclusive education in selected three (3)

schools in Isabela, subjected to validation by experts in the

78

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

field of Special Education was utilized. Results were validated

through guided interviews: for the principal/regular teachers/

Special Education teachers, parents of non-disabled children

and parents of disabled children, focused group discussions,

and class observations. Rating Scale and Weighted Mean

were also used.

Results and Discussion

Table 1. Extent by which Salient Features of Inclusive

Education Evident and Maintained

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. There is an

3.33

implementation

and maintenance of

warm and accepting

classroom communities that embraces

diversity and honor

differences.

3.17

3.08

3.15

3.15

2. Teachers implement 3.50

a multi-level,

multi-modality

curriculum

3.50

3.19

3.11

3.11

3. Teachers teach

interactively

2.50

3.25

2.54

2.70

2.70

4. There is a provision

of continuous support for teachers in

the classroom and

breaking of professional isolations.

3.75

3.00

2.46

2.35

2.36

5. Parents are actively 3.33

involved in the

planning process in

meaningful ways.

3.00

2.75

2.45

2.46

QD

Overall computed

average mean=2.76

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

79

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Computed average mean of 3.15 shows that the

Administration, SPED teachers, regular teachers and parents

agree that implementation and maintenance of warm and

accepting classroom communities that embrace diversity

and honor differences is evident to a great extent. Stated

by Giangreco et al, (2004), cited by Kliewer & KasaHendrickson (2014) peer support programs can also create

and extend hidden safety supports in the schools as one way

to counteract the problem of bullying. They suggest students

taught in inclusive safe learning environments become more

empathetic of others (U.S. Department of Education (nos.

H324D010031 & H324C040213).

Respondents claim that teaching and learning

processes observed multi-level, multi-modality, child

centered, interactive and participatory, as shown by the

computed average mean of 3.11 and 2.70. Supported by

Focus Group Discussion (FGD), parents claim frequent

involvement of both children and parents in all school

activities during regular programs and celebrations. Parents

suggest field trips to be part of social life of special children.

Business-type lessons (making Pastillas, Turon, etc.) need

integration; these help special children realize the value of

money and hard-work.

Computed average mean of 2.36 reveals no

support for teacher teaching inclusive education from

his/her colleague and usually, the inclusive education

teacher is isolated. Mentioned during FGD, there was no

consultation with parents as to offering or implementing of

SPED classes. Besides, no medical data were submitted to

support/help determine impairment categories or levels of

among special children.

80

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

A positive result was found in the fifth feature of

inclusive education with a computed average mean of 2.46

which is evident. It shows that parents were much involved

in planning processes.

Kasa-Hendrickson and Kliewer (2014), commented

collaboration which plays a key role in inclusive

classrooms. Reciprocal process of collaboration fosters

awareness and understanding of diversity existing within

classrooms and in broader communities (U.S. Department of

Education (nos. H324D010031 & H324C040213).

As a whole, implementation of inclusive education

is evident, based on identified features and overall computed

average mean of 2.76.

Table 2. Extent by which the School Addresses the Basic

Concerns of Parents of Non-disabled Children

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. Will Inclusion

reduce the academic progress

of non-disabled

children?

3.00

3.50

2.35

2.35

2.35

2. Will non-disabled

children lose

teacher time and

attention?

3.00

2.75

2.35

2.21

2.22

3. Will non-disabled

children learn undesirable behavior

from students with

disabilities?

3.00

3.25

2.08

2.29

2.29

QD

Overall

computed

average mean= 2.29

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

81

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Inclusive Education does not reduce the academic

progress of non-disabled children, based on the computed

average mean of 2.35 which is less evident. Presence of

students with disability does not affect attention and time

given to non-disabled children, as shown by the average

computed mean of 2.22 which is less evident. Non-disabled

children do not necessarily learn undesirable behavior

from children with disabilities, as revealed by the average

computed mean of 2.29 which is less evident.

Studies prove that placement in inclusive classrooms

does not interfere with the academic performance of students

without disabilities with respect to the amount of allocated

time and engaged instructional time (York, Vandercook,

MacDonald, Heise-Neff, & Caughey, 1992; cited by

Whitbread, 2014).

Table 3. Extent by which Potential Benefits are Evident/

Manifested

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. Reduced fear

of human

differences

accompanied by

increased

comfort and

awareness.

3.00

3.17

3.15

2.83

2.84

2. Growth in

the social

cognition.

2.63

3.50

2.77

3.03

3.03

3. Improvement

of self-concept

3.50

4.00

3.00

3.05

3.05

4. Development

of personal

principles

3.00

3.50

2.81

2.94

2.94

82

QD

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

5. Warm and

caring

friendship

2.25

4.00

2.92

3.07

3.07

Overall computed average

mean=2.97

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

Indicated by computed average mean of 2.84, nondisabled children show accepting behavior; appreciate

individuals contribution in the group and live with them

without fear of human differences with increase comfort and

awareness. Computed average mean of 3.03 confirm a more

tolerant and supportive behavior, positive feeling in dealing

with disabled classmates and communicate effectively;

feel proud having classmates with disabilities as friend or

partner and it fosters a healthy and better relationship for

both, as shown by computed average mean of 3.05. Sense of

commitment to personal, moral and ethical principle of nondisabled children strengthened life prejudice as they continue

to relate with disabled children succeeded by the average

computed mean of 2.94. The average computed mean of 3.07

strongly supports warm and caring friendship as children

work and play in and out of school.

Instructional strategies in inclusive classrooms, peer

tutoring, cooperative learning groups, and differentiated

instruction benefit all learners, hold Slavin, Madden, &

Leavy, (1984), cited by Whitbread, 2014). Peer tutoring

results in significant increase in spelling, social studies

and other academic areas for students with and without

disabilities (Maheady et al, 1988; Pomerantz et al, 1994;

cited by Whitbread, 2014). Children with intellectual

disabilities educated in general education settings were found

to score higher on literacy measures than students educated in

segregated settings (Buckley, 2000 cited by Whitbread, 2014).

83

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Table 4. Extent by which Key Persons Carry Out their Roles

during the Initial Phase of Implementation of

Inclusive Education

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. Administrator

3.50

4.00

3.21

2.93

2.94

2. Regular

Teacher

2.00

3.50

3.41

2.90

2.91

3. SPED

Teacher

2.00

4.00

2.83

2.72

2.72

4. Parents

2.50

3.00

2.85

3.01

2.94

QD

Overall computed average

mean=2.87

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

Administrators support to inclusive education is

clearly positive with an average computed mean of 2.94.

While regular teachers show full support to ideas, plans and

activities of the SPED teachers and administrators, indicated

by the average computed mean of 2.91. Computed average

mean of 2.72 proves SPED teachers are working well with

regular teachers and administrators. Equally, parents of both

disabled and non-disabled children have strongly supported

plans and activities of the teachers and administrators

through their active involvement in creating a committee

that directly supports the inclusive education marked by

an average computed mean of 2.94. Student academic

achievement is higher when parents are involved - the higher

the level of parent involvement, the higher the level of

student achievement (Henderson & Mapp, 2002; Christenson

& Sheridan, 2001; cited by Whitbread, 2014).

84

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Table 5. Extent by which Key Persons Carry Out their

Roles during the Transition Phase of Implementing

Inclusive Education

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. Administrator

4.00

3.88

2.67

2.76

2.76

2. Regular

Teacher

2.50

3.40

3.06

2.82

2.83

3. SPED

Teacher

2.50

3.70

2.65

2.62

2.62

4. Parents

3.25

3.00

2.50

2.72

2.72

QD

Overall computed average

mean=2.73

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

The administrators do their part in organizing,

observing, monitoring and facilitating the activities and

programs of teachers and children with special needs, as

supported by the average computed mean of 2.76. The regular

teachers show positive effort in identifying prospective

students for inclusion through the help of the school

physician, medical personnel and guidance counselor. They

constantly coordinate and consult stakeholders to ensure a

comprehensive understanding of its objectives, activities and

programs of inclusive education, as indicated in the computed

average mean of 2.83. SPED teachers have extensively

provided assistance to the regular teachers, parents, and

administrators in all the concerns of implementing a functional

inclusive education, as shown in the average computed mean

of 2.62. Comparably, parents of disabled and non-disabled

children visibly work with the inclusive education personnel

in monitoring and coordinating the plans, activities and

achievements of their children marked by a computed mean

of 2.72.

85

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Table 6. Extent by which Key Persons Carry Out their

Roles during the Inclusion Phase of Implementing

Inclusive Education

Administrator

QD

SPED

Teacher

Regular

Teacher

Parent

QD

QD

QD

Total

1. Administrator

3.75

4.00

2.82

2.60

2.61

2. Regular

Teacher

2.50

3.50

2.87

2.56

2.57

3. SPED

Teacher

2.50

4.00

2.21

2.72

2.71

4. Parents

2.25

3.13

2.13

3.04

3.02

QD

Overall

computed

average

mean=2.73

x = mean

QD=Qualitative Description

The administrators continue to enrich the curriculum,

instructional materials and teachers through in-service

training, cooperative planning and monitoring of activities.

They link with GOs and NGOs for their social, moral

and financial support and provide incentives to regular

students with a computed average mean of 2.61. However

regular teachers show positive response to the enrolment of

children with disabilities and treat them equally. They enrich

the program by monitoring, modifying and updating the

curriculum and instructional materials with consultations, as

indicated in the computed average mean of 2.57.

Special Education (SPED) teachers do not fail

either to provide assistance to both students and teachers,

as they continuously monitor the program. Regular teachers

are enhanced through a series of in-service trainings and

consultative planning with Special Education (SPED)

86

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

teachers and experts, confirmed with a computed average

mean of 2.71. The Focus Group Discussion (FGD) sustains

these data since respondents comment that there are

consultations done to solve/resolve problems/conflicts. In

fact, in Whitbread, (2014) research cited by Villa, & WaltherThomas, (1997) it shows that principals, special education

directors, superintendents, teachers, parents and community

members must all be involved and invested in the successful

outcome of inclusive education.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The salient features, noted potential benefits and the carrying

out of key persons roles are evident to a great extent. By

contrast, basic concerns of parents of non-disabled are not

evident, so inclusive schools need not to address them.

The following are recommended: Administrators

need to secure special equipment and customized

instructional materials for special children; that allocations

be provided for the vocational training, self-help activities

and life-long learning skills; that in-service trainings for

inclusive education teachers; medical data be submitted to

help teachers determine the categories/levels of impairments

of the special child; and Individualized Educational Programs

(IEP) for each special child be done.

87

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

References

Booth, T., Ainscow, M. & Black-Hawkins, K. (2000). Index

for Inclusion: Developing Learning and Participation in Schools. Bristol: Center for Studies for Inclusion in Education.

Department of Education. (2003). Education and Inclusion in the United States. ED Pubs, Education

Publication Center, U.S. Department of Education,

Washington, D.C.

Department for Education and Skills. (2001b). Inclusive

Schooling: Children with Special Educational Needs.

London: DfES

Farrel, M. (2005). Key Issues in Special Education: Raising

Standards of Pupils Attainment and Achievement.

270 Madison Ave, New York, NY: Routledge Taylor

& Francis Group.

Gartner, A. & Lipsky, D.K. (1989). New Conceptualizations

for Special Education. European Journal of Special

Needs Education, 4(1), 16-21.

Kliewer, C. & Kasa-Hendrickson, C. (2014) cited Giangreco,

M.F., Doyle, M.B., Suter, J.C. (2004). Every child

strengthens the literate community. Retrieved 2014

from Disability, Literacy & Inclusive Education for

the Young Children: Citizenship for all in the Early

Childhood of Literate Community, page 88, http://

p

www.uni.edu/inclusion/links.html

Heubert, J. (1994). Assumptions underlie arguments

about inclusion. Harvard Education Newsletter,

10(4), 4. Retrieved 2014 from Southwest Educational

Development Laboratory (SEDL): http;//www.sedl.org/

p;

g

Heward, L. (2006). Introduction to Special Education.

New York: McMillan Co.

88

The Normal Lights

Volume 9, No. 2 (2015)

Inciong, T.G., Capulong, Y.T., Quijano, Y.S., Gregorio,

J.A., & Gines, A. C. (2007). Introduction to Special

Education: A Text Book for College Students First

Edition. Manila, Philippines: Rex Book Store

Rocal, E. (2011). Inclusive Education: A Lecture delivered

in a Seminar-Workshop for Special Education

Teachers and Advocates at Merry Sunshine

Montessori, Cauayan City, Isabela, Philippines.

Wade, J. (1999). Including all learners: QCAs approach.

British Journal of Special Education, 26(2) 80-2.

Whitbread, K. (2014). What Does the Research Say About

Inclusive Education? The Inclusion Notebook. Retrieved March 9, 2014 from http://www.uconnucedd.

p

org/resources_publications.html.

g

p

89

You might also like

- Dr. Teresita G. InciongDocument20 pagesDr. Teresita G. InciongDhan Kenneth AmanteNo ratings yet

- Quijano Philippine ModelDocument5 pagesQuijano Philippine ModelKarla Gaygayy100% (1)

- Barangay Health Workers' Level of CompetenceDocument15 pagesBarangay Health Workers' Level of CompetenceAmadeus Fernando M. Pagente100% (9)

- Lesson Plan 7e's - Metals and Non-MetalsDocument2 pagesLesson Plan 7e's - Metals and Non-MetalsAilyn Soria Ecot71% (7)

- CHAPTER 2 - Lesson 1 - 3Document13 pagesCHAPTER 2 - Lesson 1 - 3Jan Aries Manipon100% (1)

- Chapter 4 ISSUES AND TRENDSDocument4 pagesChapter 4 ISSUES AND TRENDSJomar Bumidang100% (4)

- In The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesIn The PhilippinesWilliam Buquia100% (2)

- Activity 1 Special Education TimelineDocument5 pagesActivity 1 Special Education TimelinejaneNo ratings yet

- Interactionists TheoryDocument33 pagesInteractionists TheoryJelyne santosNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Roots of EducationDocument20 pagesPhilosophical Roots of EducationCheanndelrosario40% (5)

- Using Rewards and Sanctions in The Classroom: Pupils' Perceptions of Their Own Responses To Current Behaviour Management StrategiesDocument4 pagesUsing Rewards and Sanctions in The Classroom: Pupils' Perceptions of Their Own Responses To Current Behaviour Management StrategiesmarlazmarNo ratings yet

- Theories of LearningDocument12 pagesTheories of Learninggengkapak100% (2)

- Annotation Template For Teacher IDocument8 pagesAnnotation Template For Teacher IKareen Tapia PublicoNo ratings yet

- Attitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education inDocument7 pagesAttitudes of Teachers Towards Inclusive Education inabuhaymNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Inclusive EducationDocument6 pagesPhilosophy of Inclusive EducationAriel Bryan Casiquin100% (1)

- Non Formal EducationDocument6 pagesNon Formal EducationAngelie Fiel Ballena100% (2)

- Educational IssuesDocument14 pagesEducational Issuesjoreina ramosNo ratings yet

- Unit Ii. Inclusive EducationDocument26 pagesUnit Ii. Inclusive EducationZyra CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Institutionalization of CurriculumDocument53 pagesInstitutionalization of CurriculumJohn Albert SantosNo ratings yet

- Legal Basis of Sped in The Philippines and AbroadDocument28 pagesLegal Basis of Sped in The Philippines and AbroadShiela Juno100% (1)

- Finals Lesson 4 SAFETY AND SECURITY IN THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENTDocument16 pagesFinals Lesson 4 SAFETY AND SECURITY IN THE LEARNING ENVIRONMENTVivian Paula PresadoNo ratings yet

- Language Millenium and Development GoalsDocument6 pagesLanguage Millenium and Development GoalsNiellaNo ratings yet

- Ed 4 Module 2 ADDRESSING DIVERSITY THROUGHTHE YEARS SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATIONDocument40 pagesEd 4 Module 2 ADDRESSING DIVERSITY THROUGHTHE YEARS SPECIAL AND INCLUSIVE EDUCATIONVeronica Angkahan SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Models of DisabilityDocument22 pagesModels of Disabilitylagosjackie59No ratings yet

- The Philippine Educational System in Relation To John Dewey's Philosophy of EducationDocument18 pagesThe Philippine Educational System in Relation To John Dewey's Philosophy of EducationJude Boc Cañete100% (1)

- Enhanced Instructional Management For Parents, Community and TeachersDocument16 pagesEnhanced Instructional Management For Parents, Community and TeachersJasmine RoseNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - Science Education in The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesLesson 3 - Science Education in The PhilippinesGrizzel DomingoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 5 - On Becoming A Glocal TeacherDocument6 pagesCHAPTER 5 - On Becoming A Glocal TeacherCindy Claraise S. LoretoNo ratings yet

- 2 Inclusive Education in The PhilippinesDocument9 pages2 Inclusive Education in The PhilippinesBrenda BravoNo ratings yet

- Legal Bases of SpEd in PHDocument40 pagesLegal Bases of SpEd in PHKhristyl GuillenaNo ratings yet

- Inclusive EducationDocument2 pagesInclusive EducationShenna Mae Gosanes100% (1)

- History Timeline of Sped 1908 1952Document4 pagesHistory Timeline of Sped 1908 1952Yuan UyNo ratings yet

- Typical and Atypical Development Among ChildrenDocument30 pagesTypical and Atypical Development Among ChildrenDulnuan CrizamaeNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Care and DevelopmentDocument9 pagesEarly Childhood Care and DevelopmentJologs Jr Logenio100% (1)

- Practical Research IDocument180 pagesPractical Research INoelyn GalindezNo ratings yet

- SDG - What Have I LearnedDocument4 pagesSDG - What Have I LearnedDaniela GaradoNo ratings yet

- GRP 4 Inclusive Humanitarian and Multicultural EducationDocument14 pagesGRP 4 Inclusive Humanitarian and Multicultural Educationeira may floresNo ratings yet

- The Stages of Development and Developmental Tasks: Study Guide For Module No. 3Document3 pagesThe Stages of Development and Developmental Tasks: Study Guide For Module No. 3Darlene Dacanay David100% (1)

- Purposive Communication MODULE 2020 TEJIDODocument152 pagesPurposive Communication MODULE 2020 TEJIDOMiranda, Clare Diaz.No ratings yet

- MODULE - Making Schools InclusiveDocument11 pagesMODULE - Making Schools InclusiveJedelyn Arabia AlayonNo ratings yet

- Why Is Social Studies ImportantDocument3 pagesWhy Is Social Studies ImportantArwin Arnibal100% (1)

- Foundation of Special and Inclusive Education: An OverviewDocument51 pagesFoundation of Special and Inclusive Education: An OverviewDAVE ANDREW AMOSCO100% (2)

- Changing Trends and Career in Physical EducationDocument19 pagesChanging Trends and Career in Physical EducationSrishti Bhatia100% (1)

- Unit 7:: Professionalism and Transformative EducationDocument24 pagesUnit 7:: Professionalism and Transformative EducationRobert C. Barawid Jr.No ratings yet

- Educational Implications of ExistentialismDocument6 pagesEducational Implications of ExistentialismPrecious Agno100% (4)

- Social Media & Creation of Cyber Ghettos - Report ScriptDocument2 pagesSocial Media & Creation of Cyber Ghettos - Report ScriptMona Riza PagtabonanNo ratings yet

- Learner Centered Curriculum DesignDocument5 pagesLearner Centered Curriculum DesignMa. Elaiza G. Mayo100% (1)

- Special EducationDocument23 pagesSpecial EducationGuila MendozaNo ratings yet

- Social Change and EducationDocument15 pagesSocial Change and EducationOniwura Bolarinwa Olapade100% (2)

- A Global TeacherDocument18 pagesA Global TeacherElmor YumangNo ratings yet

- Action Research On Study Habits of Students in English-ANNA MDocument8 pagesAction Research On Study Habits of Students in English-ANNA MMariel Jewel F. Silva100% (1)

- There Are Various Models of Planning Depending On People Understanding and Description of The Concept of PlanningDocument2 pagesThere Are Various Models of Planning Depending On People Understanding and Description of The Concept of PlanningBrooke JoynerNo ratings yet

- Journeying Back To One's FamilyDocument45 pagesJourneying Back To One's FamilyJaymar MagtibayNo ratings yet

- Two Decades of Universal Basic Education Programme in Nigeria.1999-2019: UBE Implementation, Achievement, Challenges and Suggested SolutionsDocument8 pagesTwo Decades of Universal Basic Education Programme in Nigeria.1999-2019: UBE Implementation, Achievement, Challenges and Suggested SolutionsresearchparksNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Education PhilosophyDocument5 pagesComparison of Education PhilosophyMarc Fernand Roberts100% (3)

- Written Report Introduction To Non Formal EducationDocument5 pagesWritten Report Introduction To Non Formal EducationJackie DumaguitNo ratings yet

- Students With Severe or Multiple DisabilitiesDocument18 pagesStudents With Severe or Multiple Disabilitiespatrocenio gorgonia jrNo ratings yet

- Session 5 Trends and Issues in Inclusive EducationDocument16 pagesSession 5 Trends and Issues in Inclusive EducationRukhsana KhanNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUS 2nd Sem Foundations of Special and Inclusive EducationDocument8 pagesSYLLABUS 2nd Sem Foundations of Special and Inclusive EducationMichael Ron Dimaano100% (2)

- Transitions to K–12 Education Systems: Experiences from Five Case CountriesFrom EverandTransitions to K–12 Education Systems: Experiences from Five Case CountriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Assessing Inclusive Ed-PhilDocument18 pagesAssessing Inclusive Ed-PhilElla MaglunobNo ratings yet

- Challenges Facing Implementation of Inclusive Education in Public Secondary Schools in Rongo Sub - County, Migori County, KenyaDocument12 pagesChallenges Facing Implementation of Inclusive Education in Public Secondary Schools in Rongo Sub - County, Migori County, KenyaIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Challenges Facing Implementation of Inclusive Education in Public Primary Schools in Nyeri Town, Nyeri County, KenyaDocument9 pagesChallenges Facing Implementation of Inclusive Education in Public Primary Schools in Nyeri Town, Nyeri County, Kenyaalquin lunagNo ratings yet

- The Challenge of Enhancing Inclusive Education in Developing CountriesDocument15 pagesThe Challenge of Enhancing Inclusive Education in Developing CountriescheyangclairNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Learning ObjectivesDocument23 pagesLesson 1: Learning ObjectivesGRACE WENDIE JOY GRIÑONo ratings yet

- Automatic Recognition of Correctly Pronounced English Words Using Machine LearningDocument12 pagesAutomatic Recognition of Correctly Pronounced English Words Using Machine LearningAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Proficiency of Sophomore English Majors On The Pronunciation of The Structural Variants of "Read" Towards Improved Oral PerformanceDocument12 pagesProficiency of Sophomore English Majors On The Pronunciation of The Structural Variants of "Read" Towards Improved Oral PerformanceAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Caught in A Debt Trap? An Analysis of The Financial Well-Being of Teachers in The PhilippinesDocument28 pagesCaught in A Debt Trap? An Analysis of The Financial Well-Being of Teachers in The PhilippinesAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Articulating The Foundations of Philippine K To 12 Curriculum: Learner-CenterednessDocument12 pagesArticulating The Foundations of Philippine K To 12 Curriculum: Learner-CenterednessAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Social Science Teachers' Burnout in Selected State Universities in The PhilippinesDocument41 pagesFactors Affecting Social Science Teachers' Burnout in Selected State Universities in The PhilippinesAmadeus Fernando M. Pagente100% (1)

- Development of Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) in College StatisticsDocument28 pagesDevelopment of Computer Assisted Instruction (CAI) in College StatisticsAmadeus Fernando M. Pagente100% (2)

- Mobile Based Crime Mapping and Event Geography Analysis For CARAGADocument9 pagesMobile Based Crime Mapping and Event Geography Analysis For CARAGAAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Number Theory Worktext For Teacher Education ProgramDocument37 pagesNumber Theory Worktext For Teacher Education ProgramAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Compassion and Forgiveness - Based Intervention Program On Enhancing The Subjective Well-Being of Filipino Counselors: A Quasi-Experimental StudyDocument24 pagesCompassion and Forgiveness - Based Intervention Program On Enhancing The Subjective Well-Being of Filipino Counselors: A Quasi-Experimental StudyAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Why I Want To Teach: Exploring Factors Affecting Students' Career Choice To Become TeachersDocument28 pagesWhy I Want To Teach: Exploring Factors Affecting Students' Career Choice To Become TeachersAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Exploring Vietnamese Students' Attitude Towards Project Works in Enhancing Autonomous Learning in English Speaking ClassDocument23 pagesExploring Vietnamese Students' Attitude Towards Project Works in Enhancing Autonomous Learning in English Speaking ClassAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Environmental Sustainability Assessment of An Academic Institution in Calamba CityDocument29 pagesEnvironmental Sustainability Assessment of An Academic Institution in Calamba CityAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Outcome-Based Program Quality Assurance Accreditation Survey Instrument: Its Development and ValidationDocument30 pagesOutcome-Based Program Quality Assurance Accreditation Survey Instrument: Its Development and ValidationAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- FloodAlert: Automated Flood Warning System For DOST Region IV-A Project HaNDADocument9 pagesFloodAlert: Automated Flood Warning System For DOST Region IV-A Project HaNDAAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- The Use of Non-Math Analogies in Teaching MathematicsDocument25 pagesThe Use of Non-Math Analogies in Teaching MathematicsAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Reciprocal Teaching Approach With Self-Regulated Learning (RT-SRL) : Effects On Students' Reading Comprehension, Achievement and Self-Regulation in ChemistryDocument29 pagesReciprocal Teaching Approach With Self-Regulated Learning (RT-SRL) : Effects On Students' Reading Comprehension, Achievement and Self-Regulation in ChemistryAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Self - and Teacher-Assessment of Science Process SkillsDocument18 pagesSelf - and Teacher-Assessment of Science Process SkillsAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of Instructional Modules On Rational Expressions and Variations Evelyn TorrefrancaDocument31 pagesDevelopment and Validation of Instructional Modules On Rational Expressions and Variations Evelyn TorrefrancaAmadeus Fernando M. Pagente100% (2)

- Facilitating Learning Through Parent-Teacher Partnership ActivitiesDocument17 pagesFacilitating Learning Through Parent-Teacher Partnership ActivitiesAmadeus Fernando M. Pagente100% (2)

- Personal Computer (PC) - Based Flood Monitoring System Using Cloud ComputingDocument7 pagesPersonal Computer (PC) - Based Flood Monitoring System Using Cloud ComputingAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- Questions Students Ask As Indices of Their ComprehensionDocument32 pagesQuestions Students Ask As Indices of Their ComprehensionAmadeus Fernando M. PagenteNo ratings yet

- FS 2 - Episode 1 Principles of LearningDocument9 pagesFS 2 - Episode 1 Principles of LearningHenry Kahal Orio Jr.No ratings yet

- Sat-Rpms Development NeedsDocument2 pagesSat-Rpms Development NeedsRa MilNo ratings yet

- UTS - Reflection Multiple IntelligenceDocument2 pagesUTS - Reflection Multiple IntelligenceYeho ShuaNo ratings yet

- Deped Order 42 S 2016Document34 pagesDeped Order 42 S 2016dolly kate cagadas100% (2)

- MAM Roque Module 678 AnswerDocument5 pagesMAM Roque Module 678 Answerejay0% (1)

- Lesson11. The Deped K-12 Rating System DiscussionDocument3 pagesLesson11. The Deped K-12 Rating System DiscussionRiza PacaratNo ratings yet

- مقياس المهارات الاجتماعيةDocument44 pagesمقياس المهارات الاجتماعيةAymanahmad AymanNo ratings yet

- The Goals, Standards and Scope of The Teaching Science GoalDocument4 pagesThe Goals, Standards and Scope of The Teaching Science Goalrena jade mercado75% (4)

- Lesson Plan PlaydoughDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Playdoughapi-236946678No ratings yet

- Rubrics For ReportingDocument1 pageRubrics For ReportingAira MaeNo ratings yet

- Psychometrician 07-2015 Room AssignmentDocument21 pagesPsychometrician 07-2015 Room AssignmentPRC Baguio100% (1)

- Psychology: Cognition: Thinking, Intelligence, and LanguageDocument53 pagesPsychology: Cognition: Thinking, Intelligence, and LanguagemuhibNo ratings yet

- Alia Sultan Obaid Al Kaabi: ObjectiveDocument2 pagesAlia Sultan Obaid Al Kaabi: ObjectiveAlia AlkaabiNo ratings yet

- Dice Addition Subtraction Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesDice Addition Subtraction Lesson Planapi-474629690100% (1)

- Teaching AntigoneDocument2 pagesTeaching Antigoneapi-299531626No ratings yet

- Tubato, K. - Reflective JournalDocument2 pagesTubato, K. - Reflective JournalKate Alyzza TubatoNo ratings yet

- Mr. Abelardo B. Medes - Assessment and Rating of Learning Outcomes (Elementary Level)Document51 pagesMr. Abelardo B. Medes - Assessment and Rating of Learning Outcomes (Elementary Level)McDaryl MateoNo ratings yet

- U5 l2 Lesson PlanDocument5 pagesU5 l2 Lesson Planapi-324604427No ratings yet

- Ibrahim AssignmentDocument5 pagesIbrahim AssignmentSarbaz AyubNo ratings yet

- St. Angelus of Sicily Academy: Teacher'S Learning Plan Math 4Document4 pagesSt. Angelus of Sicily Academy: Teacher'S Learning Plan Math 4salc higher departmentNo ratings yet

- Cep Teacher Quality StandardsDocument17 pagesCep Teacher Quality Standardsapi-355082850No ratings yet

- Grade 9 First Quarter Summative AssessmentDocument2 pagesGrade 9 First Quarter Summative AssessmentMarilyn Ongkiko75% (12)

- Contextualized DLLDocument5 pagesContextualized DLLGaycel Mariño RectoNo ratings yet

- Cara Masukkan PLC (Ketua Kumpulan)Document27 pagesCara Masukkan PLC (Ketua Kumpulan)smks15006100% (2)

- Chapter 3Document7 pagesChapter 3Susan SamsonNo ratings yet