Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Childhood Years and Youth

Childhood Years and Youth

Uploaded by

enoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Childhood Years and Youth

Childhood Years and Youth

Uploaded by

enoCopyright:

Available Formats

Childhood years and youth

Recep Tayyip Erdoan was born in Kasmpaa, a poor neighborhood of Istanbul. His family was originally from Rize,[1] a conservative town on the northeastern coast of the Black Sea, and

returned there when Erdoan was still an infant, coming back to Istanbul again when he was 13. He spent those years attending Istanbul mam Hatip school and selling lemonade and simit

(sesame rings) on the city's streets to make extra money.[2]

While studying business administration at what is today Marmara University's Faculty of Economics and Administrative Sciences and playing semi-professional football,[3] Erdoan also

engaged in politics by joining the National Turkish Student Union, an anti-communist action group. In 1976, he became the head of a local youth branch of the Islamist National Salvation

Party (MSP), led by Necmettin Erbakan, who would later go on to found the Felicity Party. This was the beginning of Erdoan's long career in politics.[4]

Mayor of Istanbul

After the 1980 coup, Erbakan's movement regrouped under the Welfare Party (RP), and Erdoan gradually became one of its stars. In 1991, Erdoan became a candidate for Parliament on the

party's ticket and won a seat, only to be kept from taking it on a technicality.

In 1994, Erdoan was elected Mayor of Istanbul to the shock of the city's more secular citizens, who thought he would ban alcohol and impose Islamic law. Instead, he emerged over the next

four years as a pragmatic mayor who tackled many chronic problems in the city, including pollution, water shortages and traffic.[5]

Meanwhile, the political environment was growing tense in Turkey, as the Welfare Party came to power in June 1996 in a coalition government with the center-right True Path Party (DYP). RP

head Necmettin Erbakan, who became Turkey's first openly Islamist prime minister, conflicted with the principle of the separation of religion and state in Turkey with his radical rhetoric. Six

months later, in February 1997, the military initiated what was later dubbed the "post-modern coup".[6] Soon, Erbakan was ousted from power and many Islamist groups were the subject of a

crackdown as part of a series of court cases opened by prosecutors.[7]

Erdoan was caught up in this crackdown in 1997, when he made a public speech in the southeastern province of Siirt denouncing the closure of his party and recited these lines of a poem

from the Turkish War of Liberation: "The mosques are our barracks, the domes our helmets, the minarets our bayonets and the faithful our soldiers."

A court held that this speech was an attack on the government and Islamist rhetoric, and sentenced Erdoan in September 1998 to a 10-month prison term, of which he served four months. He

was also banned from holding political office for life. "Erdoan's political career is over," some mainstream newspapers wrote at the time. "From now on, he can't even be a local governor." [8]

Between 1999 and 2001

Abdullah Gl, 2011

In the aftermath of the post-modern coup, Erdoan came to believe that a new political line, different from Erbakan's anti-Western demagoguery, was needed. This was something he hinted at

in the Siirt speech that netted him a prison term. As part of that speech, Erdoan also said: "The Western man has freedom of belief; in Europe, there is respect for worship, for the headscarf.

Why is there not in Turkey?"

This Western-oriented line would be the new vision of Erdoan and the more open-minded members of the Erbakan movement, such as Abdullah Gl. In their vision, authoritarian secularism

in Turkey should not be considered an extension of the West, as religious conservatives had done for decades. The West should rather be seen as a way to create a more liberal Turkey that

would respect religious liberty as well. Erdoan had personal reasons to make that choice: He could thus send his veiled daughters, Esra and Smeyye, not to Turkish universities, where there

is a headscarf ban, but to American ones, where the coverings can be worn.[9]

Erdoan and his colleagues thus put European Union membership, and EU-promoted political reforms, at the top of their agenda at the expense of being accused of "treason" by their old

comrades who stayed loyal to Erbakan.

The birth of the AK Party

In 2001, Erdoan and Gl established the Justice and Development Party (AK Party). The party chose as its emblem a modern light bulb, and Erdoan asserted that the AK Party was "not a

political party with a religious axis", but rather one that could be defined as a mainstream conservative party. Its message concentrated on political liberalization and economic growth gave the

party a sweeping victory in the general elections of November 2002.

Even though his party won the elections, Erdoan could not become prime minister right away, as he was still banned from politics by the judiciary for his speech in Siirt, and Gl thus became

the prime minister instead. In December 2002 the Supreme Election Board canceled the general election results from Siirt due to voting irregularities and scheduled a new election for

February 9, 2003. By this time, party leader Erdoan was able to run for Parliament thanks to a legal change made possible by the opposition Republican People's Party (CHP) and its leader,

Deniz Baykal. The AK Party listed Erdoan as a candidate for the rescheduled Siirt election, and he won, becoming prime minister after Gl subsequently handed over the post. [10]

References

1.

"BABAKAN ERDOAN "GRC" ASILLI MI!". Retrieved 2010-10-31.

"Turkey's charismatic pro-Islamic leader". BBC News. 2004-11-08. Retrieved 2009-11-12.

"Erdoan'n futbol oynad yllar". Haber3 (in Turkish). 2011-01-01. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

1.

"The making of Turkey's prime minister". Hrriyet Daily News. 2010-10-31. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

"Recep Tayyip Erdoan - World Leaders Forum". Columbia University. 2008-11-13. Retrieved 2010-10-31.

"Turkey and the art of the coup". Reuters. 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2010-12-21.

"In Defense Of Secularism, Turkish Army Warns Rulers". The New York Times. 1997-03-02. Retrieved 2011-01-18.

"Muhtar bile olamaz". Radikal (in Turkish). 1998-09-24. Retrieved 1998-09-24. Check date values in: |access-date= (help)

"The Erdogan Experiment". The New York Times. 2003-05-11. Retrieved 2010-09-21.

"Turkey: AKP leader Erdogan wins by-election in Siirt". wsws.org. 2003-03-15. Retrieved 2010-12-12.

External links

Lifestory of Recep Tayyip Erdoan (English)

Official biography of Recep Tayyip Erdoan (Turkish)

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Feedback On LeadsDocument1,979 pagesFeedback On LeadsPremkumar Velappan100% (1)

- Educational Theory A Qur' Anic Outlook PDFDocument382 pagesEducational Theory A Qur' Anic Outlook PDFPddf100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Quran For Young Adults Day 1Document4 pagesQuran For Young Adults Day 1Ali R BeatmakerNo ratings yet

- Review Mukhtasar Al-QuduriDocument2 pagesReview Mukhtasar Al-QuduriMansur Ali0% (1)

- Zainab and KarbalaDocument3 pagesZainab and KarbalaFaraz Haider100% (1)

- Panitia Quran Borang Hafazan 1-5Document11 pagesPanitia Quran Borang Hafazan 1-5Khairiah IsmailNo ratings yet

- RawalpindiDocument83 pagesRawalpindiEngr Saeed KhanNo ratings yet

- Merits of Omar Ibn Khattab (Radi - Allah Anhu)Document3 pagesMerits of Omar Ibn Khattab (Radi - Allah Anhu)zamama442No ratings yet

- Organ Transplant in IslamDocument17 pagesOrgan Transplant in IslamMichael WestNo ratings yet

- Markahthn52014 (Pat2013)Document17 pagesMarkahthn52014 (Pat2013)Shuhada AzmiNo ratings yet

- Kitab at Tauhid The Book of Monotheism Sh. Muhammad Bin Abdul WahhabDocument193 pagesKitab at Tauhid The Book of Monotheism Sh. Muhammad Bin Abdul Wahhabrehanchhipa243No ratings yet

- Amir Khusraw PDFDocument152 pagesAmir Khusraw PDFpranshu joshi100% (1)

- Election Officer Past PapersDocument13 pagesElection Officer Past Papersgcu974100% (1)

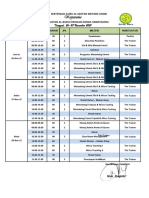

- Jadwal Sertifikasi Korda Blora Gel. IVDocument1 pageJadwal Sertifikasi Korda Blora Gel. IVVeri RiyantoNo ratings yet

- Konsep DiniDocument16 pagesKonsep DiniEndy ZQnoexNo ratings yet

- Learning About Islam Student NotebookDocument6 pagesLearning About Islam Student Notebookapi-233464494No ratings yet

- Medieval Societies The Central Islamic LDocument2 pagesMedieval Societies The Central Islamic LSk sahidulNo ratings yet

- Finding Nouf - Discussion GuideDocument4 pagesFinding Nouf - Discussion GuideHoughton Mifflin HarcourtNo ratings yet

- NilaiDocument3 pagesNilaiMaidy Khan NewDelhiNo ratings yet

- Sekularisme 01Document12 pagesSekularisme 01اعسىNo ratings yet

- Rafik Isaa BeekunDocument5 pagesRafik Isaa BeekunanggitaNo ratings yet

- The Creed of A Muslim in Light of The Quran and SunnahDocument37 pagesThe Creed of A Muslim in Light of The Quran and SunnahAnsariNo ratings yet

- Endless Lıfe Akhırah (Afterlıfe)Document1 pageEndless Lıfe Akhırah (Afterlıfe)tunaNo ratings yet

- Senarai Nama Kelas Tingkatan 2 Tahun 2023Document5 pagesSenarai Nama Kelas Tingkatan 2 Tahun 2023Siti AyuNo ratings yet

- Background: Radiyallahu 'Anhu Sallallahu Alayhi WasallamDocument6 pagesBackground: Radiyallahu 'Anhu Sallallahu Alayhi WasallamkenshinrkNo ratings yet

- Compendium of Islamic LawsDocument126 pagesCompendium of Islamic Lawsmusarhad100% (4)

- Kānpur, Uttar Pradesh, India (26° 28' N, 80° 20' E)Document2 pagesKānpur, Uttar Pradesh, India (26° 28' N, 80° 20' E)Mohd Zubair KhanNo ratings yet

- Speculative Partnership in IslamDocument6 pagesSpeculative Partnership in IslamVero100% (1)

- Sunnat-ul-Qawliyyah: This Sunnah Is The Sayings of The Holy: SignificanceDocument8 pagesSunnat-ul-Qawliyyah: This Sunnah Is The Sayings of The Holy: SignificancealiaNo ratings yet

- Global Islamism, Jihadism and Maulana Abul KalamDocument2 pagesGlobal Islamism, Jihadism and Maulana Abul Kalam58qsbt2zfyNo ratings yet