Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Collaboration, Alliances &: The Coordination Spectrum

Collaboration, Alliances &: The Coordination Spectrum

Uploaded by

KashifMuhmoodOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Collaboration, Alliances &: The Coordination Spectrum

Collaboration, Alliances &: The Coordination Spectrum

Uploaded by

KashifMuhmoodCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSUE 1 2002 / 22

strategic partnership:

collaboration, alliances &

the coordination spectrum

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

By JAMES B. RICE JR., Director MIT Integrated Supply Chain Management Programme

and DR. STEFANO RONCHI, Politecnico di Milano

INTRODUCTION AND

MOTIVATION

Recent developments have increased the

importance of collaboration among

companies in supply networks. Several

drivers stand out among others, in

particular:

Supply chain integration now plays a

strategic role in industry ranging from

competitive necessity to potential

source of competitive advantage.

Close relationships are being

recognized as requirements for

successful supply chain integration. 1

Increased outsourcing and supply

network redesign require and are

emphasizing the necessity of

coordination among the parties that

comprise the supply network.

For many, the new requirements for close

relationships and coordination translate

into heightened need for collaboration

among companies.

SUPPLY CHAIN INTEGRATION:

CLOSER RELATIONSHIPS REQUIRED

As suggested above,having an integrated

supply chain is increasingly being seen as a

competitive weapon and a potential source

of competitive advantage. A critical

requirement for creating an integrated

supply chain is creating and maintaining

close relationships with other companies in

the supply network.

This need is apparent in Prof. Hau Lees

framework characterizing supply chain

integration as having three key dimensions:

Information integration; Coordination; and

Organizational linkage. Each of these

dimensions calls for deeper, more engaged

interaction among the companies of a

supply network ranging from coordinating

the use of information, to coordinating

work processes and resources,and finally to

creating a "tight linkage of the

organizational relationships between

companies" including communication

channels, performance measures, shared

and/or aligned incentives, shared risks and

gains.2

OUTSOURCING:

COORDINATION REQUIRED

The increasing market turbulence and

competition (in terms of quality, cost and

service level), the reduction in product life

cycles, the increased variety of products,

and services and technology evolution

have lead companies to search for higher

flexibility, in terms of mix, volume, products

and technologies. Because of the difficulty

to develop and manage all these different

technologies and competencies, many

organizations have redesigned their

THE REQUIRED CLOSE

RELATIONSHIPS AND

COORDINATION AMONG

COMPANIES ARE

POPULARLY REFERRED TO

AS COLLABORATIONS,

PARTNERSHIPS, AND

OCCASIONALLY AS

ALLIANCES

internal company supply chain by

outsourcing various parts of their supply

chain activities.

This popular trend in industry to

outsource components of business

operations entails narrowing business

scope in order to reduce working capital

requirements and focus the remaining

operations on core competencies. The

result is that previously vertically integrated

businesses have become dependent on

outside organizations3 to fulfill demand.

Often, a connected set of flows across the

functions of a single economic entity are

replaced by the same flows among

separate, independent companies in a

business-to-business relationship, each

business having separate objectives, goals,

measures, and financial fate. Frequently, a

company may find it more effective to use

other firms with special resources and

technical knowledge to perform these

business functions. Even if a firm has the

resources to execute a particular task,

another company could be better suited to

perform that task simply because of its

location,its resources,its expertise,its ability

to exploit economies of scale, and/or its

ability to bear risk thus reducing costs.

This new dependence on external

companies further increases the need to

coordinate processes and build close

relationships as the success of each

company is now connected to the

performance of the others in the network.

Ultimately, these independent companies

are turning to close relationships as ways to

approximate the benefits of vertical

integration (control, economies of scope,

relatively uninterrupted flows across the

business) without the onus of ownership,

management, and capital investments.

ISSUES

The required close relationships and

coordination among companies are

popularly referred to as collaborations,

partnerships, and occasionally as alliances.

These terms are not consistently used in

industry, with many different definitions

that are often lacking in clarity and

consistency.4 The lack of common

terminology leads to confusion and failure

to develop a deep understanding of the

underlying concepts. We propose a way to

segment and classify the various types of

collaboration among customer-supplier

(dyadic) relationships5 using economic and

coordination theory as a foundation.

DESCRIBING CLOSE

RELATIONSHIPS ALONG

A SPECTRUM OF

COORDINATION

MECHANISMS

It may be useful to start refining the

definitions of the various terms and their

use by starting with the definition of

coordination developed by Malone and

Crowston,6 where "Coordination is

managing

dependencies

between

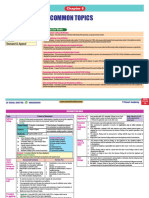

Figure 1: Spectrum of coordination mechanisms

(Adopted and synthesized by authors from various referenced authors)

Markets

Transactional

Relationships

Alliances (Hybrids)

Information

Sharing

Alliances

activities." They further state explain that

collaboration is only one type of

coordination.

From the economics literature, there are

fundamentally

two

alternative

coordination7

mechanisms

for

coordinating among business operations:

markets and hierarchies. Markets represent

cases where economic actors (both firms

and final users) coordinate with each other

in order to sustain the exchange of goods

or services among themselves. Hierarchies

entail cases where an entity coordinates

through ownership of production

resources, maintaining the authority to

exercise and impose as one single entity its

own decisions through a system of

incentives and disincentives (awards and

punishments).

The industrial economics literature

identifies a third type of coordination

mechanism between markets and

hierarchies. This is the so-called hybrid,

quasi-market or intermediate mode of

organization.

In hybrids, the firms

coordinate with each other through some

integration activities often including longterm contracts, without committing to a

particular hierarchic model (through, for

example, merger or acquisition).

Hybrids have been referred to in multiple

terms. De Maio and Maggiore call them

partnerships, in which the transaction also

entails cooperating and collaborating

together to improve both actors

performances (De Maio and Maggiore,

1992). Similarly, Simchi-Levi calls them

strategic alliances (Simchi-Levi et al., 2000)

where many forces drive companies

towards collaboration seeking win-win

situations between companies. Lynch calls

these relationships alliances, and

differentiates between partnerships by

suggesting that partnerships imply legally

binding obligations (Lynch, 1993).

All coordination mechanisms taken

together, they form a continuum or

spectrum of relationships that can also be

Collaborative

Operations

Alliances

(Design,

Engineering,

Logistics)

Hierarchies

Collaborative

Network

Alliances

observed in practice. Several academics

have characterized these in various ways:

Ellram identifies four levels of coordination

between market and hierarchy: short-term

contract, long-term contract, joint venture

and equity interest (Ellram, 1991); Macbeth

and Ferguson write about product life

relationship, shared destiny, minority shareholding, strategic alliance and joint venture

as intermediate types of relationship

(Macbeth and Ferguson, 1994). Rice and

Hoppe8 derived a set of three distinct

coordination activities9

required for

coordinating between different companies

of a supply network including coordinating

connected information and information

systems, coordinating logistics process and

operations, and coordinating network-level

decisions and tradeoffs (balancing financial

commitments (benefits, investments,

operational costs, equity) and risks).

Synthesizing these varying definitions

and conditions, we propose segmenting

the Market Mechanism Hybrid

Hierarchy spectrum of alternative

coordination mechanisms into six groups

Transactional Relationships, Information

Sharing Alliances, Collaborative Logistics

Alliances, Collaborative Network Alliances,

Partnerships, and Vertical Integration. Each

of these categories or segments has

different characteristics which are

presented in Figure 1.

The six categories or segments of

coordination mechanisms can be

described in the following ways:

Transactional Relationship

The simplest and most fundamental

market

coordination

mechanism,

transactional relationships entail only buyand-sell activities in a traditional armslength relationship. The activities are

typically

accomplished

in

single

transactions purchasing products using

open market processes to buy products at

market prices. Examples of this include

buying directly from vendors in retail

Partnerships

Hierarchies

Markets

ISSUE 1 2002 / 23

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

Vertical

Integration

outlets, through online marketplaces

(including but not limited to auctions), and

via catalogs. The goals and the objectives

of the two parties involved in the

transaction might not match; for this

reason the relationship is not exclusive

the buyer could find other suppliers and

the seller could find other customers.

Alliance

We propose using this term in general to

describe the hybrid relationships. These

market coordination mechanisms are not

pure market mechanisms in that they entail

more than buy-and-sell transaction

activities. In alliances, two companies share

some common interest, exchange value

through buy-and-sell activities, and also

perform some coordination activities.

This is typically a multi-dimensional and

goal-oriented relationship between two

firms in which both organizations do some

sharing, ranging from passive information

to sharing both risks and rewards. Similarly,

there are varying degrees of shared goals,

and a broad range for time horizon and

level of commitment. These will be

expanded in the respective sections below.

Depending on the coordination activities

performed, the alliance falls into one of two

categories:

Information Sharing Alliance This

entails only passive information sharing

as a coordination activity. Examples of

this are practices such as order tracking

or inventory visibility. E.g. Lucent

Technologies shares information about

inventory levels and forecasts with over

300 suppliers through its web-portal.

Collaborative Operations Alliance This

entails information sharing and active

process coordination in one or more

domains product design, engineering,

and/or logistics (supply chain). Some of

the likely activities include process

improvement, planning (such as vendor

managed inventory or CPFR). E.g.

Lucent Technologies collaborates on

ISSUE 1 2002 / 24

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

forecasts with 25 suppliers (not 300)

through its web-portal).

Collaborative Network Alliance This

entails information sharing, active

process coordination, and making

network-level financial decisions and

tradeoffs (including mutual investments

in joint assets, balancing financial risk

and rewards). Examples of this are

where a customer and supplier share

some of the costs for relationshipspecific assets such as a dedicated

warehouse that would normally be the

sole responsibility of only one of the

parties. E.g. Chrysler and Toyota may

serve as the best examples in practice

today as Dyer has illustrated .10

We purposely choose not to use the term

partnership

to

describe

hybrid

relationships (or partners to describe the

parties), as this term implies some measure

of a legal commitment or obligation.

Specifically, the term implies that two

ONE LARGE CORPORATION

WAS SUED BY A SUPPLIER

WHOS ORDERS WERE

CANCELLED AFTER THE

SUPPLIER MADE

SIGNIFICANT CAPITAL

INVESTMENTS BECAUSE THE

CUSTOMER INDICATED IT

WANTED TO CREATE A

PARTNERSHIP WITH THE

SUPPLIER

parties will be making a commitment that

entails sharing risk and rewards equally; the

term "has strong legal implications

regarding your ability to incur legally

binding commitments on the part of your

partner, and vice versa."11 One large

corporation was sued by a supplier whos

orders were cancelled after the supplier

made significant capital investments

because the customer indicated it wanted

to create a partnership with the supplier. 12

Information Sharing Alliance

This alliance describes a relationship

where market buy-and-sell transactions are

augmented with passive information

sharing (mainly performance and outcome

information

rather

than

process

information). The firms maintain their

respective information and planning

systems and incorporate information from

the other firm as possible. This may

represent a case where the firms are in the

early stages of developing a more

meaningful relationship, or where the firms

have limited commonality in goals. The

information is shared with the expectation

that this information may improve their

connected processes without significant

commitment or risk taken on by either firm.

Due to the limited commitment and

exposure, this relationship represents

typically a short-term commitment.

Collaborative Operations Alliance 13

This alliance describes a relationship

where the exchange of value occurs

through some market buy-and-sell

transactions but also long-term

agreements regarding material flows,

or through collaborative work on

product design or engineering. The

agreements and transactions are

augmented with active information

sharing (likely some efforts towards

common information systems and

planning processes) and supply

network process coordination and

improvement activities (the firms

decide to collaborate on inventory

management, demand fulfillment,

forecasting, new product development,

and/or marketing activities; and these

are only few examples). The two firms

share some stated common goals, and

there may be some dedicated

resources committed by each firm to

create and maintain a high degree of

integration. Due to the goals commonality

and the kind of information shared and

resources committed, this relationship

presents typically a medium-to-long term

commitment. Such a commitment and

collaboration often lead to strategic

benefits for both partners.

We

introduce

the

descriptor

collaborative to this relationship because

unlike the previous relationships, this

alliance calls for active engagement

between the firms, working towards some

shared common goal.

Collaborative Network Alliance

This alliance describes the most

committed level of alliance, where the

exchange of value occurs mainly through

long-term agreements and includes

financial, resource and/or risk sharing. The

agreements are supported with fairly open

and active information sharing, supply

network process coordination and

improvement activities, and making

network-level financial decisions and

tradeoffs (including mutual investments in

joint assets, balancing financial risk and

rewards). As with the collaborative

operations alliance, the two firms share

some stated common goals,but the level of

commitment in terms of dedicated

resources and risk sharing is significantly

higher and more complex.

Most

importantly, the two firms make mutual

investments in dedicated assets to improve

their supply network and develop creative

agreements and arrangements in order to

balance the risk across the firms. Due to the

common goals, dedicated resources and

mutual investments, this relationship

presents a long-term commitment. Such a

commitment and collaboration are often

intended to create shared strategic benefits

for both firms.

The level of process integration may be

described as virtual integration and

seamless. We introduce the descriptor

network to this relationship because

unlike the previous relationships, this

alliance calls for the firms to make decisions

on their respective supply network designs

rather than being limited to process

coordination and integration.

Partnership

As

we

categorize

coordination

mechanisms, we place partnerships

squarely in the domain of hierarchies. We

consider partnerships as hierarchies in the

sense that partnerships (as we define them)

entail some equity ownership. The equity

ownership enables the equity owner to

coordinate by exercising some control by

virtue of owning some of the business.14

This would include joint ventures and cases

where the ownership is less than 51 per

cent (which is the cusp of being able to

exercise full control).

The partnership would also entail all of

the previously described activities for

Collaborative Network Alliances, except the

ISSUE 1 2002 /25

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

level of commitment is significantly higher.

Goals and objectives of the two companies

are so similar that the financial structure of

the relationship changes the two firms

sharing equity interests are no longer two

completely separate entities. For this

reason collaboration and integration

become even stronger and the firms share

their destiny. Some examples can be found

in subsidiaries, joint ventures, and equity

interests cases.

One could argue that companies with less

than 51 per cent ownership may not be

able to exercise full control and therefore

the relationship would not technically

qualify as a pure hierarchical coordination

mechanism15 where control through

ownership is the critical coordination

benefit of ownership. We consider that the

part owner will be able to exercise some

control and therefore consider it a type of

hierarchical coordination mechanism,

although we recognize that this may not

always be the case. In those cases, the

relationship may be best described by the

kind of activities undertaken between the

firms, rather than by the type of ownership

structure.

Vertical Integration

Finally, vertical integration represents a

pure hierarchy ownership of all the valueadding entities and exercise of that

ownership to coordinate activities among

the entities. This solution enables the

owner to coordinate the supply network

through control. By virtue of having a

controlling interest in the firms, the owner

may exercise full control over all the

activities performed and the objectives

become all the same.16 The costs of

acquiring or merging another company

could be very high and the efforts in

making the cultures compatible could be

such high as well. Due to the characteristics

of this relationship, the time-horizon is very

long because the switching costs related to

the integration are relevant.

It is important to note that in literature

and in practice, authors and business

leaders often speak about strategic

alliances and partnerships as though they

have the same meaning. As suggested

before, we believe, like Lynch17, that

partnerships describe relationships where

there is some shared ownership, and that

alliance is the more appropriate descriptor

for close relationships where there is no

common or shared ownership. This may

seem like hair-splitting, but it is not

uncommon for two organizations to

interpret partnerships in very different

terms, leading to relationship damage and

lost opportunities.

Parties behave

differently when there is some measure of

ownership, as well as the party has greater

ability to coordinate as an owner.

CHARACTERISTICS OF

COORDINATION

MECHANISMS

To further delineate the alternative

coordination mechanisms, and in particular

the alliances, we have developed a matrix

that characterizes many of the salient

differences among the alternatives.

Important ways that we have segmented

the coordination and alliance types are:

Degree of common goals between the

two firms,

Time horizon of the relationship

between the two firms,

Structure of the relationship between

the two firms,

Description of the relationship between

the two firms,

Activities by coordination method

between the two firms, and

Instruments for coordinating and

balancing cost, benefits and risk

between the two firms.

See Figure 2 for a matrix outlining and

describing these various factors.

INSTRUMENTS FOR

MEDIATING RISK

The instruments for coordinating and

balancing cost, benefits, and risk in a

relationship represent an important way for

companies to potentially develop more

tangible deep relationships. Associated

with different types of coordination

mechanisms, the various instruments

provide alternatives to the firms for

mediating risk across the two firms in a

formal and predictable way. (By mediating

risk, we mean the process of balancing

costs, benefits, and risks associated when

buying or selling a good or service). Given

that the inherent limitation in coordinating

between two firms is that they are separate

economic entities, reducing the risk that

each firm bears in working together may

provide valuable benefits that have yet to

be quantified. For this reason, we believe it

is useful to examine the various ways of

mediating risk, particularly in the cases

where firms are intent on collaborating in

meaningful ways, yet still independent and

separate entities.

For transactional relationships and

information sharing alliances, price is the

only mediation instrument. All risk

associated with producing a product for a

customer is built into the price of the

product. The price will increase as the firm

takes on increased risk when making

products that require dedicated

investments or when the volume falls

below economic order quantities.

In collaborative alliances (collaborative

operations alliances and collaborative

network alliances), these instruments play

ISSUE 1 2002 / 26

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

Figure 2: Characteristics of Various Coordination Mechanisms

Transactional

Relationships

Information

Sharing

Alliances

Goals

Different

Some shared

interest in

improving

process

Some similar

Some,most goals

Some similar

are common

goals to improve goals to improve

network

logistics flows &

operation

new products

All goals are

common

Time Frame

Short-term, as

long as the

transaction

Short-term, as

long as the

process

Medium-to-LongTerm,dependent

on shared

investment in

mutual assets

and processes

Long-Term

Long-Term,

limited by

structure of

ownership

(possible to sell

minority share)

Long-Term

Structure

Two seperate

entities

Two seperate

entities

Two seperate

entities, some

shared assets

Multiple entities

with equity

One Owner

Description of

Relationship

Competitive

arms lenght

relationship

Make joint

Passively

Actively

investments in

collaborative collaborative mutual efforts to

assets and

sharing

resources

information only improve common

processes

High level of

risk sharing and

active

collaborative

effort

One integrated

entity

Activities by

Coord Method

Buy and Sell

Products &

Services

Buy and Sell

Buy and sell

Long-Term

Prods/Svcs Passive Prods/Svcs share agreements,

Info Sharing

info, Active

Share key info,

Coord & Plng

Active Coord,

systems &

Mutual

Processes

Investments &

Balanced Risk

Run the

Business with

other Part

Owners

(Partners)

Run the

Business as

Owner

Instr. for

Mediating Risk

Price

Partial Control

via Partial

Ownership

Control as

Owner

an important role. Generally, alliances use

price, non-price instruments such as

contingency and/or long-term contracts,

and what are known as hostages in the

economics literature. (A hostage is

anything that has a low value for the party

that is holding it, but a great value for the

party bestowing it).18 The exchange of

hostages between firms could prevent

possible opportunistic behaviors; for

example, the hostage could be an equity

investment made by both parties in the

case of a partnership or the hostage could

be transaction-specific investments made

by both parties. Alternatively, the firm that

makes an investment in physical assets that

are dedicated to the relationship, has

created a hostage that the other firm may

use to gain leverage unless the investing

firm protects themselves before making

the investment by arranging for offsetting

volume commitments or capital

contributions for instance. These hostages

may be conditions that already exist or may

be conditions that one of the parties

attempts to create. Additionally, each party

may actively seek out or leverage potential

hostages for further non-negotiated

mediation. Another example of a hostage

Two seperate

entities

Price

Collaborative

Operations

Alliances

Price, LongTerm contracts,

Contingency

Contracts,

Hostages

Collaborative

Network

Alliances

Shared goals,

Long-Term &

Contingency

Contracts,

Hostages

is provided by the relationship between a

consumer products manufacturer and a

3rd party logistics (3PL) provider, where the

3PL has all the competencies, the

distribution channel and the contacts with

the manufacturers customers. These are all

very valuable activities for the

manufacturer and therefore constitute a

sort of hostage in the hands of the 3PL.

Like trust, this appears to be an important

method for building close, collaborative

relationships; unlike trust, these methods

are tangible and provide clear non-price

methods for the two firms to not only

IT IS USEFUL TO

EXAMINE THE VARIOUS

WAYS OF MEDIATING

RISK, PARTICULARLY IN

THE CASES WHERE FIRMS

ARE INTENT ON

COLLABORATING IN

MEANINGFUL WAYS,YET

STILL INDEPENDENT AND

SEPARATE ENTITIES

Partnerships

Vertical

Intergration

balance but also possibly reduce risk across

the two firms. This may represent a

potentially powerful and under-utilized

method for building close relationships

that calls for further investigation. Instead

of using only price to offset the risk that a

firm takes when selling its products into a

channel, it is also possible to supplement

the pricing arrangement with non-price

terms, supporting processes and/or

contingency contracts. Examples of these

include:

Structuring a sale with a price based on a

guarantee volume purchase, affording

the customer some flexibility and

committed support, while at the same

time sparing the supplier from making

customer-specific commitments without

offsetting guarantees for volume.

Supporting customer fulfillment with

services (such as VMI or CRP) that

provide the supplier with some

demand visibility and control over

inventory, again offsetting risk

associated with uncertain demand

somewhat.

Structuring an agreement with

committed service levels in exchange

for volume of mix commitments,

possibly also menu pricing for different

service levels.

Structuring an agreement with

guaranteed return processes in

exchange for guaranteed volume

commitment.

The instruments described are explicit

and formal agreements, although in

practice some of these arrangements are

implicit.

An example is offered to illustrate. In

many cases a vendor may build a

production or distribution facility next to a

customer operation with a tacit

understanding and expectation that the

customer will provide certain levels of

volume. This arrangement works well

when the customer volume exists and

grows, and both firms benefit from highly

aligned operations that are effective and

efficient. This can be disastrous, however, if

the tacit agreement is not honored for a

variety of reasons. The reasons for the

failure cover a broad range:

Seemingly innocuous and predictable

changes in personnel ("Sorry, that

agreement was made with my

predecessor, not me."),

Service failures by the supplier ("You

failed to deliver volume per our need,

so we are giving half of the volume

now to competitor X."), and

Failures by the customer to provide

adequate volume (that were necessary

from the suppliers perspective) to

offset the risk taken on by the supplier

("Sorry that we didnt need as much

product as we forecast, but we wont

pay for the units you produced or for

the cost of underutilized labor.").

These cases leave both firms hurt with

and little recourse to the problem aside

from costly, relationship-damaging legal

battles.

Partnerships use the same instruments as

alliances with the added instrument of

ownership-associated control (power to

influence outcomes) and equity (incentive

via benefits to owners of the business

performance). Finally, vertical integration

uses control and equity ownership to

mediate the risk.

We believe further study of this will be a

productive exercise and may provide

insight into an as-yet-undiscovered key

success factor for developing collaborative

relationships. Some key questions we are

interested in learning about:

How do collaborating firms in a supply

network structure and arrange their

relationships and contracts to manage

risk & allocate system level benefits?

What are the key methods?

What are the benefits that each specific

method produces? What are the

appropriate conditions for utilizing the

various respective methods?

SUMMARY/NEXT STEPS

We have used the adopted definition that

collaboration is but one method of

coordination19, and we have proposed a

spectrum of coordination alternatives for

practitioners to select from when building

and designing their supply network.

Furthermore, collaboration was defined in

the context of market coordination

mechanisms and we offered various

alliances as distinct alternatives for

building close relationships between two

firms of a supply network. Hopefully, the

distinctions we have drawn and the

terminology proposed are useful, and will

enable firms to build deeper relationships

with selected companies in their

respective supply networks.

As suggested above, one of the ways we

have

distinguished

the

various

coordination alternatives is by the

instruments for making and coordinating

financial tradeoffs. We believe this holds

promise as a potential key success factor in

eliminating inherent and embedded risk in

the supply network.

The commonly used term partnerships

should be limited in use to cases where

there is shared equity ownership in the

firm, otherwise alliance may be a more

accurate and descriptive term. These

alliances are not all alike, and we have

proposed three distinct alliances, which if

put in practice, may enable firms to more

clearly define their interests in

collaborating as well as the potential

benefits associated with that specific effort.

One other area of study that would likely

be productive is the study and

identification of key success factors for

building collaborative alliances. While

collaboration is a commonly used and

generally accepted term today, it is unclear

how successful companies have been

developing successful collaborative

alliances, nor are the key success factors

clearly identified and understood. This too

would be a useful area of study. LS

ISSUE 1 2002 /27

WE HAVE DEFINED COLLABORATION AS ONE METHOD OF

COORDINATION, AND WE HAVE PROPOSED A SPECTRUM

OF COORDINATION ALTERNATIVES FOR PRACTITIONERS TO

SELECT FROM WHEN BUILDING AND DESIGNING THEIR

SUPPLY NETWORK

LOGISTICS SOLUTIONS

partnerships

This work was supported by research funding from the sponsors of the

Integrated Supply Chain Management (ISCM) Program at the MIT Center for

Transportation Studies.

James B.Rice,Jr.is Director of the Integrated Supply Chain Management

Program and graduate instructor at Massachusetts Institute of Technology,

Center for Transportation Studies. Correspondence should be sent to 77

Massachusetts Ave.,Room 1-235,Cambridge,MA 02139-1307. Phone

617.258.8584,fax 617.253.4560,email:jrice@mit.edu,website:

http://web.mit.edu/supplychain/www/ou-iscm/base.html

Dr.Stefano Ronchi was a visiting student from Politecnico di Milano in

Milan,Italy working at the MIT Center for Transportation Studies at the time

this research was conducted.

Refences

1 Lee,Hau "Creating Lasting Values in Supply Chain Collaboration" August 7,

2000,"Supply chain integration is considered to be a key element of

competitivenessintegration requires close collaboration."

2 The framework and quotes provided in this paragraph are taken from Prof.

Lees paper "Creating Lasting Values in Supply Chain Collaboration" August

7,2000

3 The outside organizations are often either third party contract

manufacturers that produce private label products and services to

specification,or separate operating businesses that design,produce and

market branded products or services.

4 Karl Mandrodt and Mike Fitzgerald,"Seven Propositions for Successful

Collaboration" SCMR July-August 2001. In this article,the authors suggest

"collaboration can be thought of as the act of leveraging supply chain

assets beyond the current set of customers and suppliers to include other

significant entities." In their framework,collaboration by definition entails

three companies,and alliances only deals with two companies.

5 This work does not address coordination across multiple tiers of the supply

network. That topic and its issues are addressed in the Sept-Oct 2001

SCMR article "Supply Chain versus Supply Chain" and in the August 2001

working paper "Network Master and Three Dimensions of Supply

Network Coordination" both works by Rice and Hoppe

6 Malone,Thomas W.,Crowston,Kevin "The Interdisciplinary Study of

Coordination" ACM Computing Surveys,Vol.26,No.1,March 1994,p.90.

7 This work refers to the definition of coordination mechanisms based on the

definition of governance structures provided by Williamson:"the

institutional framework within the integrity of a transaction is decided"

(Williamson,1979).

8 Rice,James B.,Jr.and Hoppe,Richard M."Network Master & Three

Dimensions of Supply Network Coordination:An Introductory Essay"

Working Paper August 24,2001

9 These may be considered a generic set of required coordination activities

that are specific to coordinating supply networks.

10 Dyer,Jeffrey H.,Collaborative Advantage:Winning Through Extended

Enterprise Supplier Networks,Oxford University Press 2000

11 Lynch,Robert Porter,Business Alliances Guide:The Hidden Competitive

Weapon,John Wiley & Sons,1993,page 28

12 Ibid.

13 For the purposes of this article,we are referring to collaborative alliances

between two firms in a supply network,or vertical collaborative alliances.

Specifically,collaborative alliances between co-customers or co-suppliers

(horizontal collaborative alliances),and between SBUs within a corporate

holding company are not directly addressed in this article. While there will

be some applicable learning,the referenced cases entail different

economics and warrant a separate discussion.

14 See comments on the partnership in the previous section entitled Alliance.

15 In some cases,the minority-stake owner may not elect to exercise control,

and instead treat this as an investment rather than a way to coordinate. In

those instances,one could argue that the relationship is more of an

alliance because the minority-stake owner does not coordinate through

its control. We do not fully address these instances,although we posit that

this would still be a hierarchical coordination mechanism that the

company chooses not to exercise. This is also the case where a company

has full ownership but is organized as a conglomerate and so does not

utilize its capability to control.

16 The case of a holding company may not meet this definition as the owner

typically does not exercise control and hence,there is no hierarchical

coordination delivered.

17 Lynch,Robert Porter,Business Alliances Guide:The Hidden Competitive

Weapon,John Wiley & Sons,1993,page 28

18 Williamson,O.E.,1983,Credible commitments:Using hostages to support

exchanges,American Economic Revoew,73,519-40.

19 Ibid.Malon and Crowston

You might also like

- Michael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageFrom EverandMichael Porter's Value Chain: Unlock your company's competitive advantageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Weekly Exercises On Pre-Contractual Instruments and MoU - June 2023Document15 pagesWeekly Exercises On Pre-Contractual Instruments and MoU - June 2023ABHISHEK IPRNo ratings yet

- Illy CafeDocument21 pagesIlly CafeVũ Trang M-tp100% (1)

- International Business Exam - SET1Document7 pagesInternational Business Exam - SET1Joanne Pan100% (2)

- Topic - External NetworkDocument31 pagesTopic - External NetworkMarina SpînuNo ratings yet

- UvA IFRS 1 Consolidation and Business Combinations BBDocument80 pagesUvA IFRS 1 Consolidation and Business Combinations BBpercioneNo ratings yet

- Panchami ShadakshariDocument8 pagesPanchami Shadaksharipanchami68No ratings yet

- Case Study 1Document6 pagesCase Study 1RIBABIRNo ratings yet

- Obstacles To Process Integration Along The Supply Chain: Manufacturing Firms PerspectiveDocument9 pagesObstacles To Process Integration Along The Supply Chain: Manufacturing Firms Perspectiveksamanta23No ratings yet

- Bagi Chapter 10 External RelationshipsDocument18 pagesBagi Chapter 10 External RelationshipsNanda Mulia SariNo ratings yet

- Exploring The Transaction Dimensions of Supply Chain ManagementDocument17 pagesExploring The Transaction Dimensions of Supply Chain ManagementbecliaNo ratings yet

- 90 172 5 PBDocument9 pages90 172 5 PBDragos-Neculai Terlita-RautchiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 20 - Transorganizational ChangeDocument3 pagesChapter 20 - Transorganizational ChangeAzael May PenaroyoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document48 pagesChapter 4Sofia VieroNo ratings yet

- The International Journal of Logistics Management Realities of Supply Chain CollDocument15 pagesThe International Journal of Logistics Management Realities of Supply Chain CollNadaNo ratings yet

- Networking and Collaborating With CorporatesDocument6 pagesNetworking and Collaborating With CorporatesJona D'johnNo ratings yet

- 1 J.witkowski B.rodawski The Essence...Document22 pages1 J.witkowski B.rodawski The Essence...johnSianturiNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Importance of Collaboration in Strategy Design and Efficiency of Supply Chain PartnershipDocument6 pagesA Review of The Importance of Collaboration in Strategy Design and Efficiency of Supply Chain PartnershipInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- 1.3.7. Inter-Firm Relationships - Overview: Why Relationships Matter in The Value Chain ApproachDocument3 pages1.3.7. Inter-Firm Relationships - Overview: Why Relationships Matter in The Value Chain ApproachErika PetersonNo ratings yet

- And Heightened Communication Described As "Two Way Street." The Intent of The HeightenedDocument3 pagesAnd Heightened Communication Described As "Two Way Street." The Intent of The Heightenedujjal khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Supplier Relationship and PartneringDocument12 pagesChapter 4 Supplier Relationship and PartneringDes Valdez27No ratings yet

- The Buddy System: Louise RossDocument4 pagesThe Buddy System: Louise RossAntara MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Building Joint Ventures in 6 Steps PDFDocument14 pagesBuilding Joint Ventures in 6 Steps PDFNathanael VanderNo ratings yet

- Collaboration Between Supply ChainsDocument42 pagesCollaboration Between Supply Chainsahmed100% (1)

- Assignment OF Global Logistics & Supply Chain OperationsDocument18 pagesAssignment OF Global Logistics & Supply Chain OperationsAmit Pal SinghNo ratings yet

- Kale Article SummaryDocument11 pagesKale Article SummaryCamilla CenciNo ratings yet

- Strategic Value-Chain Analysis of Indian Pharmaceutical AlliancesDocument20 pagesStrategic Value-Chain Analysis of Indian Pharmaceutical Alliancesarunbose576100% (1)

- 12 SporlederDocument11 pages12 SporledervenkateshNo ratings yet

- Ssrn-Id1012643 Strategic Cost ManagementDocument33 pagesSsrn-Id1012643 Strategic Cost Managementapi-285650720100% (1)

- Strategic AlliancesDocument27 pagesStrategic AlliancesBen LagatNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1 - DE LEON MICHY MARIEDocument6 pagesAssignment 1 - DE LEON MICHY MARIEdeleonmichymarieNo ratings yet

- Dunning Cap 5 - ResumenDocument29 pagesDunning Cap 5 - ResumenMicaela MartinezNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Strategies: Carlitos Jeric C. Corpuz OMT 1-2Document4 pagesCooperative Strategies: Carlitos Jeric C. Corpuz OMT 1-2Cora CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Transorganisational ChangeDocument26 pagesTransorganisational ChangeAshutosh ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Strategic AlliancesDocument22 pagesStrategic AlliancesAngel Anita100% (2)

- Encyclopedia Strategic Alliances JVsDocument11 pagesEncyclopedia Strategic Alliances JVsKrishma AfgNo ratings yet

- Week 6Document9 pagesWeek 6grandtheory7No ratings yet

- Claudious Gwaze AssignmentDocument14 pagesClaudious Gwaze AssignmentStandrick MuchiniNo ratings yet

- Della Corte - Resource Integration Management in Networks Value Creation An Empirical Analysis of High Quality Tourist Offer in Southern ItalyDocument16 pagesDella Corte - Resource Integration Management in Networks Value Creation An Empirical Analysis of High Quality Tourist Offer in Southern ItalyBhodzaNo ratings yet

- Successful and Sustainable Business Partnerships: How To Select The Right PartnersDocument11 pagesSuccessful and Sustainable Business Partnerships: How To Select The Right PartnersBenjamin NaulaNo ratings yet

- Importance of Strategic AllianceDocument8 pagesImportance of Strategic AllianceMary DickersonNo ratings yet

- Framework For Supply Chain Collaboration Agri Food IndustryDocument17 pagesFramework For Supply Chain Collaboration Agri Food IndustryCH Naveed AnjumNo ratings yet

- Value Chain Analysis and Competitive Advantage: Prescott C. EnsignDocument25 pagesValue Chain Analysis and Competitive Advantage: Prescott C. Ensignsitisinar dewiameliaNo ratings yet

- Mba - Group 5 - Cooperative Strategy FinalDocument21 pagesMba - Group 5 - Cooperative Strategy FinalAwneeshNo ratings yet

- The Competitive Advantage of Strategic AlliancesDocument9 pagesThe Competitive Advantage of Strategic Alliancesnimbusmyst100% (2)

- Sol Set GcsaDocument50 pagesSol Set Gcsajeet_singh_deepNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain ManagementDocument15 pagesSupply Chain ManagementMehak GuptaNo ratings yet

- CollaborationDocument10 pagesCollaborationayesha baberNo ratings yet

- IJRPR21631Document21 pagesIJRPR21631fady.shawky30No ratings yet

- Partnership and Strategic Alliance in Tourism and HospitalityDocument9 pagesPartnership and Strategic Alliance in Tourism and HospitalityJeffrey AyerasNo ratings yet

- ATSC Project Proposal Group-6 - Section B 1. Theory-Vertical Integration Theory 2. Project TopicDocument4 pagesATSC Project Proposal Group-6 - Section B 1. Theory-Vertical Integration Theory 2. Project TopicDivya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Vertical Integration and The Scope of The Firm - Cap 13Document15 pagesVertical Integration and The Scope of The Firm - Cap 13Elena DobreNo ratings yet

- Managing Across BoundariesDocument16 pagesManaging Across BoundariesPam UrsolinoNo ratings yet

- Inter CorporateDocument3 pagesInter CorporateSonia Lawson100% (1)

- The Power of Partnership Why Do Some Strategic Alliances Succeed, While Others Fail?Document6 pagesThe Power of Partnership Why Do Some Strategic Alliances Succeed, While Others Fail?Vinay KumarNo ratings yet

- Estimating Benefi Ts of Demand Sensing For Consumer Goods OrganisationsDocument17 pagesEstimating Benefi Ts of Demand Sensing For Consumer Goods OrganisationsIsmael SotoNo ratings yet

- Müller 2009Document25 pagesMüller 2009Dy MoreiraNo ratings yet

- CH:7 Supply Relationships: By: Ohud AltalhiDocument16 pagesCH:7 Supply Relationships: By: Ohud AltalhiReef AlhuzaliNo ratings yet

- Learning in Strategic AlliancesDocument9 pagesLearning in Strategic AlliancesADB Knowledge SolutionsNo ratings yet

- What Is LogisticsDocument5 pagesWhat Is LogisticsRamadurga PillaNo ratings yet

- Strategic Economic Relationships: Contracts and Production ProcessesFrom EverandStrategic Economic Relationships: Contracts and Production ProcessesNo ratings yet

- Case 6 - JCB in IndiaDocument3 pagesCase 6 - JCB in IndiaMauricio Bedon100% (1)

- Common Topics Quick RevisionDocument8 pagesCommon Topics Quick Revisionmaulesh bhattNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurship - MGT602 Power Point Slides Lecture 43Document10 pagesEntrepreneurship - MGT602 Power Point Slides Lecture 43Sourav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Diageo PLCDocument13 pagesDiageo PLCRitika BasuNo ratings yet

- Midterm Period Assignment 5 - Modes of Entering International BusinessDocument2 pagesMidterm Period Assignment 5 - Modes of Entering International Businessjoanna supresenciaNo ratings yet

- RFP - Ahmedabad - Dhulera - Pkg-IV-EPC342020Document87 pagesRFP - Ahmedabad - Dhulera - Pkg-IV-EPC342020SwanandNo ratings yet

- Joint Venture in India - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)Document3 pagesJoint Venture in India - Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)GURMUKH SINGHNo ratings yet

- SM Unit 3Document34 pagesSM Unit 3ANKUR CHOUDHARYNo ratings yet

- Compilation of Partnership CasesDocument13 pagesCompilation of Partnership CasesJanet FabiNo ratings yet

- Receipt and Opening of BidsDocument23 pagesReceipt and Opening of BidsJaron FranciscoNo ratings yet

- 39 File8545514810Document253 pages39 File8545514810SDE TRANS BSNLNo ratings yet

- Ch-3 IMDocument9 pagesCh-3 IMJohnny KinfeNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 148187 April 16, 2008 Philex Mining Corporation, Petitioner, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Decision Ynares-Santiago, J.Document6 pagesG.R. No. 148187 April 16, 2008 Philex Mining Corporation, Petitioner, Commissioner of Internal Revenue, Respondent. Decision Ynares-Santiago, J.Jhoi MateoNo ratings yet

- Counsel VP M&A Real Estate in Chicago IL Resume Roger BestDocument3 pagesCounsel VP M&A Real Estate in Chicago IL Resume Roger BestRogerBestNo ratings yet

- Corporate Strategies I: Moses Acquaah, Ph.D. 377 Bryan Building Phone: (336) 334-5305 Email: Acquaah@uncg - EduDocument34 pagesCorporate Strategies I: Moses Acquaah, Ph.D. 377 Bryan Building Phone: (336) 334-5305 Email: Acquaah@uncg - EduanvidhaNo ratings yet

- Strategic AllianceDocument30 pagesStrategic AlliancePranesh Khambe100% (2)

- Company IndexingDocument10 pagesCompany IndexingRushank ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Tender Documents For Mandira Small Hydro Electric Project (10Mw), Odisha Volume-1 of 4Document110 pagesTender Documents For Mandira Small Hydro Electric Project (10Mw), Odisha Volume-1 of 4nira365No ratings yet

- Nestle PresentationDocument32 pagesNestle PresentationNeoh WongNo ratings yet

- 2016 CORPORATE LAW Outline-RevisedDocument59 pages2016 CORPORATE LAW Outline-RevisedBenn DegusmanNo ratings yet

- Metro Bus ServiceDocument78 pagesMetro Bus ServiceZahid SarwerNo ratings yet

- Company PrequalificationDocument58 pagesCompany PrequalificationNazir HussainNo ratings yet

- Undp ProjectDocument44 pagesUndp ProjectliyaNo ratings yet

- Cases Set 2 - DigestsDocument17 pagesCases Set 2 - DigestsDelsie FalculanNo ratings yet

- Agency Case Digests 1. Yu v. NLRC, 224 SCRA 75, G.R. No. 97212, June 30, 1993 Yu v. NLRC GR No. 97212, June 30, 1993Document9 pagesAgency Case Digests 1. Yu v. NLRC, 224 SCRA 75, G.R. No. 97212, June 30, 1993 Yu v. NLRC GR No. 97212, June 30, 1993Leslie Ann DestajoNo ratings yet

- Financial Performance of Commercial Banks in NepalDocument117 pagesFinancial Performance of Commercial Banks in NepalBee RazNo ratings yet

- ADR For Joint Venture Construction ProjectsDocument21 pagesADR For Joint Venture Construction ProjectsAinul Jaria MaidinNo ratings yet