Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lambert 2009

Lambert 2009

Uploaded by

Ivan LiwuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lambert 2009

Lambert 2009

Uploaded by

Ivan LiwuCopyright:

Available Formats

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

ListenCarefully:TheRiskofErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

BruceL.Lambert,Ph.D.1,2,LauraWalshDickey,Ph.D.3,WilliamM.Fisher,Ph.D.4,RobertD.Gibbons,

Ph.D.5,SwuJaneLin,Ph.D.1,PaulA.Luce,Ph.D.6,ConorT.McLennan,Ph.D.7,JohnW.Senders,Ph.D.8,

ClementT.Yu,Ph.D.9

DepartmentofPharmacyAdministration,UniversityofIllinoisatChicago;2DepartmentofPharmacy

Practice,UniversityofIllinoisatChicago;3DepartmentofCommunicationScienceandDisorders,

UniversityofPittsburgh;4WilliamM.FisherConsulting,Inc.,Gaithersburg,MD;5CenterforBiomedical

Statistics,DepartmentofPsychiatry,UniversityofIllinoisatChicago;6DepartmentofPsychology,

UniversityatBuffalo;7DepartmentofPsychology,ClevelandStateUniversity;8FacultyofApplied

Science,UniversityofToronto,Toronto,Ontario,Canada;9DepartmentofComputerScience,University

ofIllinoisatChicago.Afterthefirstauthor,theorderoftheremainingauthorsisalphabetical.

CorrespondingAuthor:BruceL.Lambert,Ph.D.

Address:

DepartmentofPharmacyAdministration,

833S.WoodStreet(M/C871),Chicago,IL606127231

Phone:

3129962411

Fax:

3129960868

Email:

lambertb@uic.edu

WordCount:

7991

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Abstract

Cliniciansandpatientsoftenconfusedrugnamesthatsoundalike(Hicks,Becker,&Cousins,

2008).Weconductedauditoryperceptionexperimentstoassesstheimpactofsimilarity,familiarity,

backgroundnoiseandotherfactorsoncliniciansandlaypersonsabilitytoidentifyspokendrugnames.

Accuracyincreasedsignificantlyasthesignaltonoise(S/N)ratioincreased,assubjectivefamiliaritywith

thenameincreasedandasthenationalprescribingfrequencyofthenameincreased.Forcliniciansonly,

similaritytootherdrugnamesreducedidentificationaccuracy,especiallywhentheneighboringnames

werefrequentlyprescribed.Whenonenamewassubstitutedforanother,thesubstitutednamewas

almostalwaysamorefrequentlyprescribeddrug.Objectivelymeasurablepropertiesofdrugnamescan

beusedtopredictconfusability.Themagnitudeofthenoiseandfamiliarityeffectssuggeststhatthey

maybeimportanttargetsforintervention.

SingleSentenceSummary:Theabilityofcliniciansandlaypeopletoidentifyspokendrugnamesis

influencedbysignaltonoiseratio,subjectivefamiliarity,prescribingfrequency,andthesimilarity

neighborhoodsofdrugnames.

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Introduction

Inclinicalmedicine,therisksofmisinterpretationoftelephoneordersarewidelyrecognized

(Koczmara,Jelincic,&Perri,2006;PennsylvaniaPatientSafetyAuthority,2006;TheJointCommission,

2008).Theuseofthetelephonetocommunicatemedicationordersleadstoerrorbecauseofboth

ambientnoiseandthelimitedbandwidthofmosttelephones(Aronson,2004;Hoffman&Proulx,2003;

Lambert,2008;Rodman,2003;Wiener,Liu,Nelson,&Hoffman,2004).Telephonestypicallycarrysignals

between300Hzand3kHz,amuchnarrowerbandwidththanthatofFMradio(30Hzto15kHz)orCD

audio(20Hzto20kHz);whereas,muchoftheimportantacousticinformationthatallowspeopleto

distinguishbetweensimilarconsonantsoundsliesabove3kHzandismissingentirelyfromthe

telephonesignal(Rodman,2003).Thereare3.8billionprescriptionsdispensedinoutpatientpharmacies

annuallyintheUnitedStates(IMSHealth,2008).Telephoneordersaccountfor34%ofretail

prescriptionvolume.Thistranslatesto114milliontelephoneprescriptionsannually,or312,000perday.

Onestudyof813telephoneorderstotwochainpharmaciesfoundthatthewrongmedicationnamewas

transcribedin1.4%oftheorders(Camp,Hailemeskel,&Rogers,2003).The1.4%ratemaynotbea

generalizableestimate,butgiventhenumberofopportunities,evenaverylowerrorratewould

translateintoalargenumberoferrors.

Spokenorderswereoncecommonininpatientsettingsalso,althoughlesssoafteraccrediting

agenciespressedfortheirelimination.One346bedhospitalcounted4197medicationrelatedverbal

ordersinasevendayperiod(Wakefield,etal.,2008).Hospitalpharmacistsreported35minutesofevery

8hourshiftwerespentresolvingproblemswithspokenorders(Allinson,Szeinbach,&Schneider,2005).

Respondentsidentifiedpeopletalkinginthebackgroundandbackgroundnoiseasthegreatest

barrierstothecorrectprocessingofspokenorders.Otherfactorsincludedlackoffamiliaritywiththe

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

patientsclinicalconditionorthemedication,badconnectionsandexcessivelyrapidspeech(Allinson,et

al.,2005).

Theuseofcellphonesandvoicemailandthenoisyenvironmentsinwhichordersaresentand

received,increasetheriskofspokenprescriptionordersbeingmisperceived.Therearemanyexamples

ofauditoryperceptionerrors,somewithfatalconsequences(e.g.,Liquibidvs.Lithobid,Cardenevs.

codeine,Lopidvs.Slobid,erythromycinvs.azithromycin,Klonopinvs.clonidine,Viscerolvs.vistaril,

Orgaranvs.argatroban)(Allinson,etal.,2005;Dr.ordersLiquibidLithobiddispenseddeathresults.

Caseonpoint:Cliffordv.GeritomMed.,Inc.,681N.W.2d680MN(2004),"2004;Koczmara,etal.,2006;

PennsylvaniaPatientSafetyAuthority,2006;Vivian,2004).

Identifyingthefactorsthatinfluenceaccuracyintheperceptionofspokendrugnamesmay

facilitateinterventionsdesignedtomaketelephoneorderssafer.TheU.S.FoodandDrugAdministration

andthepharmaceuticalindustryhavestruggledtodevelopmethodsforevaluatingtheconfusabilityof

newdrugnames(U.S.FoodandDrugAdministration,2008).Wehaveshownthatobjectivemeasuresof

similarityandprescribingfrequencycanreliablypredicttheprobabilitythattwonameswillbeconfused

invisualperceptionandshorttermmemory(Lambert,1997;Lambert,Chang,&Gupta,2003;Lambert,

Chang,&Lin,2001b;Lambert,Donderi,&Senders,2002;Lambert,Lin,Gandhi,&Chang,1999;Lambert,

Yu,&Thirumalai,2004),andwehavedescribedprocessesfordesigningsaferdrugnames(Lambert,Lin,

&Tan,2005).Oneimportantpartofthatprocessistouseestablishedexperimentalparadigmsfrom

psycholinguisticstoevaluatetheconfusabilityofproposeddrugnamesinrelevanttasks(e.g.,auditory

perception,visualperception,andshorttermmemory).Anearlierstudyofnoiseandpharmacy

dispensingerrorsfound,counterintuitively,thatnoiseimprovedperformance,butrecommendedthat

morecontrolledexperimentsbedonetoclarifytherelationshipbetweennoiseanderrorrates(Flynn,

Barker,Gibson,&others,1996).Inthisstudy,wesoughttodemonstratehowthistypeof

4

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

experimentationcouldshedlightonthefactorsthatinfluenceauditoryperceptionofdrugnames.Thus

oneofthekeychallengesweaddressedwastotranslatethebasicscienceofauditorywordperception

intotheapplieddomainofdrugnameconfusion.Theworkwasdesignedtodeterminehowandtowhat

extentcharacteristicsofdrugnames,ofordertakers,andofpracticeenvironmentsaffectalisteners

abilitytoidentifyspokendrugnames.

AuditoryWordPerception

Toexplainauditoryperceptualconfusions,weuseLucesNeighborhoodActivationModel

(NAM)(Grossberg,1986;Luce,Goldinger,Auer,&Vitevitch,2000;Luce&Pisoni,1998;Vitevitch&Luce,

1999).Accordingtothismodel,stimulusinputactivatesasetofsimilarsoundingacousticphonetic

patternsinmemory.Theactivationlevelsoftheacousticphoneticpatternsareafunctionoftheir

degreeofmatchwiththeinput.Inturn,thesepatternsactivateasetofworddecisionunitstunedtothe

acousticphoneticpatterns.Theworddecisionunitscomputeprobabilitiesforeachpatternbasedonthe

intelligibilityandfrequencyofoccurrenceofthewordtowhichthepatterncorrespondsandthe

activationlevelsandfrequenciesofoccurrenceofallothersimilarsoundingwordsinthesystem.The

worddecisionunitthatcomputesthehighestprobabilitywins,anditswordiswhatisheard.Inshort,

worddecisionunitscomputeprobabilityvaluesbasedontheacousticphoneticsimilarityofthewordto

theinput,thefrequencyoftheword,andtheactivationlevelsandfrequenciesofallothersimilarwords

activatedinmemory.

TheNAMpredictsthatmultipleactivationhasconsequences:Spokenwordswithmanysimilar

sounding,higherfrequency(ormorecommonlyoccurring)neighborswillbeprocessedmoreslowlyand

lessaccuratelythanwordswithfewneighbors.Thesepredictionshavebeenconfirmedin

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

manystudies:Wordsindenselypopulated,highfrequencysimilarityneighborhoodsareindeed

processedlessquicklyandlessaccuratelythanwordsinlowdensity,lowerfrequencyneighborhoods,

andwordswithhigherfrequencyofoccurrenceareprocessedmorerapidlyandaccuratelythanlower

frequencywords(Jusczyk&Luce,2002;Lambert,etal.,2003).

TheNAMemploysanexplicitmathematicalfunctionthatattemptstopredictauditory

perceptualerrorsbasedontheintelligibilityofstimulusword,thefrequencyofoccurrenceofthe

stimulusword,andthesimilarityandfrequencyofneighboringwords.Thisfunctionisknownas

frequencyweightedneighborhoodprobability(FWNP).Detailedmathematicaldescriptionsofthe

functionusedtocomputeFWNPforeachnamearegivenelsewhere(Jusczyk&Luce,2002;Lambert,Lin,

Toh,etal.,2005).Otherthingsbeingequal,FWNPwillincreaseasthenumber,similarity,and

prescribingfrequencyofneighborsdecrease.TheNAMprovidedtheframeworkforthedevelopmentof

severalhypothesesaboutauditoryperception:(1)AccuracywillincreaseasFWNPincreases.(2)

Accuracywillincreaseasthesignaltonoise(S/N)ratioincreases.(3)Accuracywillincreaseasobjective

prescribingfrequencyofthetargetnameincreasesand(4)Accuracywillincreaseassubjective

familiaritywiththetargetnameincreases.

Althoughfrequencyandneighborhoodeffectsarewellestablishedinthestudyofordinary

words,wesoughttoextendthisunderstandinginthreeways.First,weplannedtostudypropernames

fromlarge,closedsetlexicon(drugnames).Mostpreviousworkhasbeendoneinopensetconditions,

anditwasnotclearwhethertypicalneighborhoodeffectswouldbepresentinalarge,closedsetlexicon

condition(Clopper,Pisoni,&Tierney,2006;Sommers,Kirk,&Pisoni,1997).Second,wewishedtostudy

multisyllabicwordsratherthanthemonosyllabic(oftenconsonantvowelconsonant)wordsthathave

typicallybeenusedinstudiesofneighborhoodeffects.Thatrequiredustodevelopmeasuresof

similarityandnewmeasuresofFWNPformultisyllabicwords(Lambert,Lin,Toh,etal.,2005).Third,we

6

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

wishedtoseewhethertheneighborhoodeffectswouldbepresentinbothexperts(clinicians)and

novices(laypeople).Weexpectedneighborhoodeffectsinexpertsbecause,presumably,theywould

possesslexicalrepresentationsoflargenumbersofdrugnames,andtheserepresentationswould

competeinthemannerdescribedabove.Wethoughtneighborhoodeffectsmightbeattenuatedor

absentinlaypeople,whomaylackrepresentationsformostdrugnamesandhencewouldnot

experiencethecompetitionthatcausesneighborhoodeffects.

Evenifwewerenotmakinganyoriginalcontributiontothebasicscienceofauditoryperception,

webelievethattheNAMprovidesapowerfulconceptualandexperimentalframeworkfor

understandingdrugnameconfusion,onewhichcouldadvanceworldwideeffortstopredictandprevent

sucherrors.Thusthepresentpaperisofferedasanexemplaroftranslationalresearch,whereconcepts

wellknowntoonecommunityareappliedtoproblemsinadifferentdomain(Woolf,2008).

Weattemptedtocontrolforalargesetoffactorsthatmightbeassociatedwithnameconfusion

errorrates.Amongthesewasthetypeofname(brandorgeneric).Onemightexpectbrandnamestobe

moreconfusingsincetheyaretypicallyshorter(Lambert,Chang,&Lin,2001a),andshorternamestend

tohavemoreneighbors(Andrews,1997;Luce&Pisoni,1998;Storker,2004).Conversely,genericnames

useacommonsystemofstems(i.e.,suffixes)whichtendstoincreasetheiraveragesimilaritytoone

another,therebyincreasingtheirconfusability(Lambert,etal.,2001a).Eitherway,thedistinction

betweenbrandandgenericnamesisanimportantoneinpractice,sowedesignedourexperimentsto

takeitintoaccount.

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

MaterialsandMethods

Design

WeusedawithinparticipantsdesigntoexaminetheeffectofS/Nratio,prescribingfrequency,

subjectivefamiliarity,andsimilarityneighborhoodsontheabilitytocorrectlyidentifyspokendrug

names.AllparticipantsheardanequalnumberofdrugnamesatallthreeS/Nratiosandallofthedrug

namesappearedatallthreeS/Nratios.Threeversionsoftheexperimentensuredthatdrugnamesand

S/NratioswerecounterbalancedacrossparticipantsandthatparticipantsonlyheardoneS/Nratio

versionofeachdrug.

Participants

Participantswerepaidforparticipating.Theexperimentwasapprovedbytheinstitutional

reviewboardsattheUniversityofIllinoisatChicagoandatClevelandStateUniversity.Sixtyseven

pharmacistswererecruitedatthe2005meetingoftheAmericanPharmacistsAssociation,76family

physiciansatthe2005meetingoftheAmericanAssociationofFamilyPhysicians,and74nursesatthe

2005meetingoftheAcademyofMedicalSurgicalNurses.Duetoequipmentmalfunctionornonnative

languageaccents,5pharmacists,2physicians,and4nurseswereexcluded,leavingN=62pharmacists,

N=74physiciansandN=70nursesforthemainanalysis.Fortythreelaypeoplewererecruitedfromthe

communitysurroundingClevelandStateUniversity.1 Allclinicianswerelicensedandactivelypracticing

atthetimeofthedatacollection.NonnativespeakersofAmericanEnglish,lefthandedindividuals, 2

Infact60laypeoplewererecruited,butfundswereavailabletotranscribeonlythefirst43setsofresponsesfor

themainanalysis.

Itiscustomarytoexcludelefthandedparticipantsfromlanguageresearchbecauserighthanderstypically

representandprocesslanguageintheirlefthemisphere,andthereismorevariabilityinhowlefthanders

representandprocesslanguage.Hemisphericdifferencescouldhaveconsequencesforthespeedand/oraccuracy

withwhichlanguageisprocessed.So,toreduceunnecessarynoiseinthedata,lefthandersareoftenexcluded.

8

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

andanyonewithseriousspeechorhearingproblemswereexcluded(Gonzalez&McLennan,2007;

Hagmann,etal.,2006).

StimulusMaterials

Weselected99brandand99genericdrugnames.Namesandprescribingfrequency

informationweredrawnfromfoursources:(1)theNationalAmbulatoryMedicalCareSurvey

(NAMCS),(NationalCenterforHealthStatistics,2001a).(2)theNationalHospitalAmbulatoryMedical

CareSurvey(HAMCS)(NationalCenterforHealthStatistics,2001b), (3)theIMSHealthNational

PrescriptionDrugAudit(NPDA)(IMS,2001),and(4)theSolucientHospitalDrugUtilizationDatabase

(SolucientInc.,2003).

Afrequencyweightedneighborhoodprobability(FWNP)wascomputedforeachname,

accordingtoaproceduredescribedelsewhere(Lambert,Lin,Toh,etal.,2005).Nameswerestratifiedby

FWNP,withtenbrandandtengenericnamesfromeachdecileofFWNP.Onebrandnameandone

genericnamewereremovedtomakethetotalevenlydivisibleintothreeS/Nconditions.Thenames

wereprofessionallyrecordedbyatrainedphonetician/phonologist.Thesereferencepronunciations

werebasedonphonemictranscriptionsfromexperiencedclinicians,collectedforadifferentproject.

EachrecordednamewaseditedintoanAIFFaudiofile.Tomimicthebandwidthlimitationsoftelephone

audio,frequenciesbelow300Hzandabove3kHzwerethendigitallyfiltered(Rodman,2003).

Stimulusdegradation.Drugnameswereplayedbackagainstabackgroundofstandard20

speakerbabble(obtainedfromAuditecofSt.Louis).Thenoisewasplayedatameanamplitudeof65dB

andwasnotbandwidthlimited(Flynn,etal.,1996).Thestimuliwereplayedateither63dB,68dB,or

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

73dB,resultinginthreeS/Nconditionsof2dB,+3dB,and+8dBrespectively. 3 Asubgroupof10lay

participantscompletedtheexperimentintheclearwithnoaddednoise.

ExperimentalProcedure

Lettersweremailedtoattendeesinadvance,andindividualswereapproachedatthe

conventioncenterandasked:(a)iftheywerelicensed,practicingcliniciansintheU.S.and(b)ifthey

wereinterestedinparticipatinginastudyofdrugnameconfusion.Participantsconsented,completeda

demographicquestionnaire,andtookapuretonehearingthresholdtest(puretonethresholdsof50dB

orlowerwereaccepted).ParticipantswereseatedataMacintoshPowerBookcomputerandfittedwith

headphoneswithanattachedmicrophone(BeyerdynamicBT190).Theparticipantthenreadthe

instructions.Playbackofthe20speakerbabblewasinitiatedandcontinuedforthedurationofthe

experiment.

ThePsyScopeexperimentprogram(Cohen,MacWhinney,Flatt,&Provost,1993)wasusedto

runthemainexperiment.Thetaskbeganwith21practicetrialsandcontinuedwith198trialsinrandom

orderasthemainexperiment.Onenamewassubsequentlydroppedfromtheanalysisduetoanerrorin

recording.Oneachtrial,participantswereaskedtorepeatbackthenametheyhadheard.Spoken

responseswererecordedthroughthelaptopsbuiltinmicrophone.Aftercompletingthemain

experiment,participantsmovedtoanothercomputerandreadaloudthe198experimentalnamesas

theywerevisuallypresentedonacomputerscreen.Participantsratedtheirfamiliaritywitheachname

ona7pointscale(extremelyfamiliarextremelyunfamiliar).

Duringpilottestingonpracticingpharmacists,theseS/Nratiosproducederrorratesofroughly25%,50%,and

75%atthelow,mediumandhighS/Nlevels.

10

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

ScoringSpokenResponses

SpokenresponsesweretranscribedintotheARPAbet(Jurafsky&Martin,2000).phonetic

alphabetbyanexperiencedlinguist(e.g.,Zyvoxwastranscribedas/Z1AYV2AAKS/,wherethe

numerals1and2indicatestresslevel).Responseswerescoredascorrectorincorrectbycomparing

thetranscribedresponsestothereferencetranscriptionsforeachofthe197stimulusnames.Because

variationinpronunciationmadeverbatimmatchingtothereferencetranscriptiontoostrictacriterion,

wedevelopedadditionalprocedurestocapturelegitimatepronunciationvariants.Thefirstwasa

computerprogramthatappliedgenerallyacceptedrulesforpronunciationvariationtothereference

pronunciations.Forexample,influentspeech,unstressedvowelsoundsarereducedtotheschwa

sound.(Schwaisashortneutralvowelsound,themostcommonvowelsoundinEnglish,e.g.thefirst

phonemeintheword/again/.)Responseswerescoredascorrectiftheycouldbeproducedbyapplying

thevariationrulestothereferencepronunciations.Evenafterapplyingtheserules,therestillappeared

tobelegitimatevariantsthatwerebeingscoredasincorrect.Sothelinguistexaminedallincorrectly

scoredresponses,identifiedthosedeemedtobelegitimatevariants,andprovidedlinguisticjustification

foreachcase.Intheend,aresponsewasscoredascorrectifitmatchedthereferencepronunciation

exactly,ifitcouldbeautomaticallygeneratedasarulegeneratedvariant,orifitwasrecognizedbyour

expertinphoneticsasalegitimatevariant.

AnalysisPlan

ThegoalofouranalysiswastoquantifythemaineffectsofFWNP,noise,frequencyand

familiarityonaccuracyinauditoryperception.DescriptiveanalysesweredoneusingSASversion9.1and

totestthehypotheses,mixedeffectslogisticregressionmodelswerebuiltwithSuperMix(Hedeker&

Gibbons,2008).

11

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Thedependentvariablewasaccuracy.Wordscorrectlyidentifiedwerescoredas1,andwords

incorrectlyidentifiedwerescoredas0.Theindependentvariableswere:(1)theFWNPscore,a

continuousvariableontheinterval0to1,reflectingthepredictedprobabilityofidentification;(2)signal

tonoiseratio,anordinalvariablewiththreelevels(2dB,+3dB,+8dB);(3)familiarity,anordinal

variablereflectingaparticipantssubjectivefamiliaritywiththename(rangingfrom1to7);(4)

prescribingfrequency,acontinuousvariablerepresentingthelog(base10)ofthemaximumfrequency

fromourmultiplesourcesofprescribingfrequencydata;(5)phonemefrequency,acontinuousvariable

representingthefrequencyofagivenconsonantorvowelinagivenpositionintheword,(6)biphone

frequency,acontinuousvariablerepresentingthefrequencyofatwophonemesequenceinagiven

positionintheword(Storker,2004).Thecontrolvariableswere(1)participantdemographics,including

age,gender,race,practicecontext,professionandyearsofexperience;(2)puretonethreshold,eight

continuousvariablesreflectingthesensitivityofaparticipantshearingineachearat500Hz,1kHz,2kHz

and3kHz;(3)length,anordinalvariablereflectingthenumberofphonemesintheword;and(4)trial,an

ordinalvariablerepresentingthesequentialpositionofagivenresponsewithinthesetof198

responses.

Totestourhypotheses,webuiltalogisticregressionmodelforthecombinedgroupof

clinicians(pharmacists,physiciansandnurses)andaseparatemodelforlaypeople,treatingthe

interceptsasarandomeffect.Wealsocarriedoutsubgroupanalysesforeachclinicalprofession,the

resultsofwhicharepresentedinselectedtablesandfigureswherespacepermits.Weidentifiedthe

correctscaleforeachindependentandcontrolvariablebyplottingthelogoddsoferrorasafunctionof

eachvariable.Iftheseplotswerelinear,termswereenteredaslinear.Iftheplotrevealedanobvious

nonlinearity,weselectedascaletofitthenonlinearformofthefunction(Hosmer&Lemeshow,1989;

Selvin,1996).WeusedKleinbaumsmethodofbackwardeliminationtodecidewhichvariablesto

includeinthefinalmodel(Kleinbaum,1994).Thismethodbeginswithafullmodelandproceedsto

12

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

eliminateasmanytermsaspossible,usinglikelihoodratioteststodecidewhichtermscontribute

significantlytothemodelsfit.Allstatisticaltestsused=0.05.Finally,weexaminedthefitbetween

observedandpredictedaccuracyratesforeachofthe197stimulusnames.Observedratesweretaken

directlyfromthedata.Foreachparticipant,weusedtheparameterestimatesfromthefittedmodeland

covariatevaluesfromthedatatogenerateapredictedproportionofcorrectidentificationsforeach

nameaveragedacrossallparticipants.

Results

Eachofthe239participantsrespondedto197stimuli,producing47,083totalresponses.Mean

accuracyontheperceptiontaskwas32.27%(s.d.=7.94,range=12.18%49.75%,alsoseeTable5).

Roughly77%ofcorrectresponseswereidentifiedbyverbatimmatching,9.5%bycomputerscoringof

alternativepronunciationsand13.5%byexpertscoringofalternatives.Thiserrorrateisroughlytwo

ordersofmagnitudegreaterthanwhatonewouldexpectinrealworldpractice(Flynn,Barker,&

Carnahan,2003).Thetaskwasintentionallydesignedtobedifficultandtoproducehigherrorrates

because(a)wewereinterestedinstudyingtheerrorsthemselves,andwewantedalargesampleof

errorstoanalyze,and(b)duetostatisticalpowerconsiderations,thenaturalisticerrorrate(perhaps

0.13%)(Flynn,etal.,2003)wouldhavemadeitimpossibletodetectanydifferencesinerrorrateacross

experimentalconditions.Thetaskwasnotdesignedtoestimaterealworlderrorrates(thatisbest

achievedbydirectobservation).Rather,ourgoalwastounderstandthefactorsthataffectedtheerror

rateinataskthatwasanalogousto,butmoredifficultthan,therealworldtask.

Table1describesparticipantdemographics.Table2givesthemeansandstandarddeviationsof

continuouspredictorsforcorrectandincorrectresponsesaswellasresultsofbivariatetestsof

associationbetweeneachpredictorandthelogoddsofacorrectresponse.Table2providestheinitial

indicationofthebeneficialeffectsoffamiliarityandprescribingfrequencyonaccuracyforboth

cliniciansandlaypeople.Forclinicians,frequencyweightedneighborhoodprobability(FWNP)andword

13

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

lengthwerealsoassociatedwithincreasedaccuracy.ForlaypeopleFWNPhadnoimpact,andlonger

nameswereactuallyperceivedlessaccuratelythanshorternames.Thenumberofphonemeshelped

cliniciansbecauseeachadditionalphonemeprovideddisambiguatinginformationthataidedthemin

discriminatingbetweensimilaralternativesinmemory.Forlaypeople,mostofwhomwereunfamiliar

withthestimulusnames,thetaskwasreallyabottomupidentificationtask,andadditionalphonemes

madethattaskharder.AsimilaranalysiscouldbemadeinrelationtoFWNP.FWNPpredictedclinician

performancebecauseFWNPmeasurestheextenttowhichanameisfreeofcompetitionfromsimilar

neighbors.Butsincelaypeoplelackedmentalrepresentationsformostofthesewords,FWNPwasnota

relevantmeasureforthem.Individualdifferencevariableslikehearingacuity,ageorexperiencehad

littleornoimpactonaccuracy(especiallyforclinicians),whereaspropertiesoftheenvironmentorthe

stimulusnamesdid.

Table12abouthere.

Table3givestheproportionofcorrectandincorrectresponsesinrelationtothenominal

predictors,aswellasresultsoftestsofthebivariateassociationbetweenpredictorsandaccuracy.For

clinicians,accuracymorethantripledfromthenoisiesttothequietestcondition.Inlaypeople,the

effectwasevenstronger.Forclinicians,gender,typeofname(brandvs.generic),raceandpractice

contextweresignificantlyassociatedwithaccuracyinbivariateanalyses,butmanyoftheseeffectswere

confoundedwithtypeofclinicianandwerenotsignificantinmultivariateanalyses.

Table3abouthere.

Figure1illustratesthepowerfuleffectoffamiliarityonaccuracy.Performanceonthemost

familiarnameswasroughlythreetimesbetterthanontheleastfamiliarnames.Thisisaconsequenceof

thewellknownwordfrequencyeffect,whichpredictsthatfamiliarwordswillbeperceivedmore

accuratelythanunfamiliarwordsdueeithertohigherrestingactivationlevelsortodecisionbiasesthat

14

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

favorfamiliaritemsinmemory(Howes,1957).Figure2showstheequallydramaticeffectsofnoiseon

accuracy,againwithperformanceimprovingbyafactorofthreeforcliniciansandbyafactorofmore

than5forlaypeopleasS/Nratioincreasedfrom2dBto+8dB.Figure2alsoshowsthatwithoutnoise,

laypeopleperformedaswellaspharmacistsinthe+8dBcondition.Therewasacleargradientin

accuracy,withpharmacistsbeingmostaccurate,followedbyphysicians,nursesandlaypeople.Asmight

beexpected,performanceappearedtobedeterminedbyeachgroupsfamiliaritywithdrugnames

greaterfamiliarityledtohigheraccuracy.

Figures1and2abouthere.

Table4givestheparameterestimatesforthefinalrandomeffectlogisticregressionmodels.

Cliniciansandlaypeopleproduceddifferentpatternsofresults,presumablybecauseclinicianshad

lexicalrepresentationsformanyofthenames,butlaypeopledidnot.Forclinicians,thetaskinvolved

(bottomup)identificationand(topdown)discriminationamongsimilarcompetingalternatives.Forlay

people,itwasprimarilyabottomupidentificationtask.S/Nratiowasassociatedwithsignificantly

improvedaccuracyinparticipantsauditoryperceptionofdrugnames.Forclinicians,frequency

weightedneighborhoodprobabilitywasassociatedwithincreasedaccuracy.Nameswithfewerandless

frequentlyprescribedneighborswereheardmoreaccuratelythannameswithgreaternumbersofmore

frequentlyprescribedneighbors.Forbothlaypeopleandclinicians,familiardrugnameswereperceived

moreaccuratelythanunfamiliarnames,althoughtherelationshipwasnonlinearforclinicians.For

cliniciansbutnotforlaypeople,nameswithhighprescribingfrequencywereperceivedmoreaccurately

thannameswithlowprescribingfrequency.Forclinicians,accuracyincreasedasthenumberof

phonemespernameincreasedwhiletheoppositewastrueforlaypeople(forthereasondescribed

above).Forbothcliniciansandlaypeople,biphonefrequencywaspositivelyassociatedwithaccuracy.

Forclinicianstheeffectofbiphonefrequencywasmodifiedsomewhatbyphonemefrequency.Thus,the

15

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

presenceofcommonsoundpatternsmadenameseasierrecognize.Forclinicians,S/Nratiointeracted

significantlywithfamiliarity,asdidphonemeandbiphonefrequency.

Cliniciansgotslightlybetteratthetaskastheycompletedmoretrials.Brandnamedrugswere

perceivedlessaccuratelybycliniciansthangenericnames,evenaftercontrollingfornamelengthand

numberofneighbors.Insubgroupanalyses(detailsnotshown)thiseffectwasrestrictedtophysicians.

Physiciansandnurseshadloweraccuracyscoresthanpharmacists.Forlaypeople,ageandhearing

acuitywereassociatedwithaccuracy.Forclinicians,onlyleftearpuretonethresholdat2000Hzwas

associatedwithaccuracy.

Table5abouthere.

Toassessgoodnessoffitofthemodel,wecomparedtheobservedandpredictedpercent

correctforeachofthe197drugnames.Therootmeansquareerrorofpredictionrangedfrom15.3%to

18.5%(seeTable5).Severalnameswererarelyidentifiedcorrectly(e.g.,sutilains,Kira,sparfloxacin,and

tromethamine),whileotherswererarelymissed(e.g.,hydrochlorothiazide,Zithromax,codeine).The

modelsaccountedforbetween32%and49%ofthevarianceinaccuracyattheleveloftheindividual

name.

Figure4abouthere.

Substitutionerrors.Themostcommontypeoferrorwasanincorrectpronunciationofthe

stimulusname(90%),butoneintenerrorswasasubstitutionerror,wheretheresponsecorresponded

toanotherrealdrugname.Substitutionsproducepotentiallyharmfulwrongdrugerrors.Modelsof

spokenwordrecognition,includingNAM,predictthatrarenameswillbemisheardascommonnames

butnotviceversa.Wetestedthishypothesis.Overwhelmingly,substitutionerrorswentinthedirection

ofthemorefrequentlyprescribedname.Therewere4692substitutionerrorsoverall.In2963(63.2%)of

theseerrors,thesubstitutednamehadahigherprescribingfrequencythanthestimulusname.In1411

16

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

cases(30.1%),thesubstitutednamewasnotinourprescribingfrequencydatabases.Consideringonly

thecaseswithknownprescribingfrequency,errorswentinthedirectionofthemorefrequently

prescribeddrug90.31%ofthetime.Forclinicians,themeandifferenceinlogprescribingfrequency

betweenthesubstitutednameandthetargetnamewas2.40(s.d.=1.82),meaningthesubstitutedname

was,onaverage,prescribed250timesmorefrequentlythanthetarget.Forerrorsthatwentinthe

directionofthemorefrequentlyprescribedname,themeandifferenceinlogfrequencywas2.75.For

errorsthatwentinthedirectionofthelowerfrequencyname,themeandifferenceinlogprescribing

frequencywasonly1.22.Thissuggeststhatconfusionsgointhedirectionofthelesscommonnameonly

whentheprescribingfrequenciesarerelativelysimilar.Asthedifferenceinprescribingfrequency

increasessodoesthetendencyfortheerrorstogointhedirectionofthehigherfrequencyname(see

Figure3).

Discussion

Ourgoalwastoidentifyfactorsthataffectaccuracyinauditoryperceptionofdrugnames.

Resultsofourexperimentssupportedourthreespecifichypothesesandourgeneralmodelofauditory

perception:(1)Accuracy(forclinicians)wasinfluencedbythesimilarityneighborhoodofeachdrug

name(i.e.,bythesimilarityandprescribingfrequenciesofneighboringnames).Nameswithlesssimilar

andlesscommonlyprescribedneighborsweremoreaccuratelyperceivedthannameswithmoresimilar

andmorefrequentlyprescribedneighbors.Nameswithfewerandlessfrequentlyprescribedneighbors

weresubjecttolesscompetitionduringwordrecognitionandwerethereforeperceivedmore

accurately.(2)AccuracyincreasedasS/Nratioincreased.And(3)familiar,morefrequentlyprescribed

nameswereperceivedmoreaccuratelythanunfamiliar,lessfrequentlyprescribednames.

Someoftheseassociationsweremorecomplexthanwehadpredicted.Therelationship

betweenFWNPandaccuracywasquadraticforclinicians,andtherelationshipbetweenfamiliarityand

accuracywascubicforclinicians.Inbothcasesthisislikelybecausesomewords(thelowfamiliarity

17

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

names)weresimplyunknowntotheparticipants.Theseunknownwordswereprocessedasiftheywere

nonwords,andtheeffectsofmanyofourpredictorsonwordsandnonwordsareknowntodiffer.For

analogousreasons,wesawinteractionsbetweenfamiliarityandotherpredictors(e.g.,S/Nratio,

phonemefrequency,andbiphonefrequency).Theserelationshipsneedtobeexploredmorethoroughly

insubsequentwork.

Ourmodelsaccountedforasubstantialamountoftheobservedvarianceinitemlevelaccuracy.

Webelievesuchmodelswouldbeusefultopolicymakersanddrugcompaniesastheyevaluatethe

confusabilityofnewandexistingdrugnames.Wefoundconfusionstobeasymmetrical,with

substitutionsoverwhelminglygoinginthedirectionofthemorefrequentname.Thus,whenpolicy

makersconsiderthepotentialforharmrelatedtoanameconfusion,theymustconsiderthedirectionof

theerror(i.e.,whichdrugwillbemistakenforwhich).Morefamiliarandmorefrequentlyprescribed

drugswilltendtohavelowererrorrates,butinthinkingaboutharm,thismustbeweighedagainsttheir

highernumberofopportunitiesforerror(Lambert,etal.,2003).

Limitations

Wemeasuredsubjectivefamiliarityaftertheparticipantscompletedtheauditoryperception

task.Therefore,itispossiblethatourmeasureofsubjectivefamiliaritymayhavebeeninfluencedby

experienceintheexperimentitself.Althoughpossible,weexpectthatthiseffect,ifitexistedatall,was

small,especiallyincomparisontothelongtermprimingeffectsoflifetimeexperience(orlackthereof)

withthesestimulusnames.Previousworkonsubjectivefamiliaritysuggeststhatitisanaccurate

measureoflifetimeexposuretowordsandthatitisbetterthanobjectivefrequencyforpredictingword

recognitionperformance(Balota,Pilotti,&Cortese,2001;Carroll,1971;Gernsbacher,1984).

Westudiedaconveniencesampleofrighthanded,nativeEnglishspeakingcliniciansandlay

people.Westudiedonly197drugnamesoutofperhaps11,000ormoredrugnamesinuseintheU.S.

18

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Generalizationstoothercliniciansandotherdrugnamesshouldbemadecautiously.Thelevelandtype

ofnoiseweusedmaynotreflectrealworkingconditions,especiallybecausethenoisewasofaconstant

typeandamplitude. 4 Realworldcontextsexperienceunpredictablenoiseofvaryingtypesand

intensities.Thelackofforeignlanguageaccents,distractions,interruptionsandofclinicalcontextwas

alsounrealistic.Thisworkshouldbereplicatedundermorerealisticconditions.

CONCLUSION

Objectivelymeasurablepropertiesofdrugnamescanbeusedtopredicttheirconfusability.The

abilitytoaccuratelyidentifyspokendrugnamesisinfluencedbysignaltonoiseratio,subjective

familiarity,prescribingfrequency,andthesimilarityneighborhoodsofdrugnames.Tominimizeerrors,

ordertakersshouldbeabletoincreasethesourcevolume,andshouldhavenoisecancelling

headphonesorquietareaswheretheycantakeorders.Althoughnotdirectlysupportedbythese

experiments,itisgenerallyagreedthatspokencommunicationofdrugnamescanbemadesaferby

usingstrategieslikereadback,spellingoutthename,providingtheindicationforthedrugorusingboth

brandandgenericnames(especiallyforphysicianswhoweremorelikelytomisperceivebrandthan

genericnames).Thefindingthatlaypersons,withnobackgroundnoise,achievedrecognitionscores

aboutequaltothoseachievedbyexpertcliniciansoperatingundermoderatesignaltonoiseratios,

underscorestheimportanceofreducinglocalandremotebackgroundnoiseandgivingordertakersthe

abilitytoincreasevoicesignalloudness.Sinceunfamiliardrugnamesaremorelikelytobemisperceived

thanfamiliarnames,itmaybepossibletoreducedrugnameconfusionsbyincreasingclinicians

familiaritywithawiderarrayofdrugnames.Itmayalsobepossibletoimproveperformancebyhaving

peoplelearnthedistinguishingpartsofsimilardrugnamesthroughrepeateddiscriminationtraining.

Neverthelessitmaybeofinteresttonotethatanumberoftheprofessionalscommentedthatthebabblenoise

wasrealistic.

19

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

However,theeffectivenessofbothsuggestedinterventionscouldhaveunintendedconsequencesand

haveyettobeevaluated.Theexperimentsandmodelsdescribedaboveshouldproveusefulto

regulatoryagenciesanddrugmanufacturerswhomustevaluatetheconfusabilityofdrugnamespriorto

allowingthemonthemarket.

20

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

References

Allinson,T.T.,Szeinbach,S.L.,&Schneider,P.J.(2005).Perceivedaccuracyofdrugorderstransmitted

verballybytelephone.AmericanJournalofHealthSystemPharmacy,62,7883.

Andrews,S.(1997).Theeffectoforthographicsimilarityonlexicalretrieval:Resolvingneighborhood

conflicts.PsychonomicBulletin&Review,4(4),439461.

Aronson,J.K.(2004).Medicationerrorsresultingfromtheconfusionofsimilarnames.ExpertOpinDrug

Saf,3,167172.

Balota,D.,Pilotti,M.,&Cortese,M.(2001).Subjectivefrequencyestimatesfor2,938monosyllabic

words.MemoryandCognition,29(4),639647.

Camp,S.C.,Hailemeskel,B.,&Rogers,T.L.(2003).Telephoneprescriptionerrorsintwocommunity

pharmacies.AmericanJournalofHealthSystemPharmacy,60,613614.

Carroll,J.B.(1971).Measurementpropertiesofsubjectivemagnitudeestimatesofwordfrequency.

JournalofVerbalLearningandVerbalBehavior,10,722729.

Clopper,C.,Pisoni,D.,&Tierney,A.(2006).Effectsofopensetandclosedsettaskdemandsonspoken

wordrecognition.JournaloftheAmericanAcademyofAudiology,17(5),331349.

Cohen,J.D.,MacWhinney,B.,Flatt,M.,&Provost,J.(1993).PsyScope:Anewgraphicinteractive

environmentfordesigningpsychologyexperiments.BehavioralResearchMethods,Instruments,

andComputers,25(2),257271.

Dr.ordersLiquibidLithobiddispenseddeathresults.Caseonpoint:Cliffordv.GeritomMed.,Inc.,681

N.W.2d680MN(2004)(2004).NursLawReganRep,45(2),4.

Flynn,E.A.,Barker,K.N.,&Carnahan,B.J.(2003).Nationalobservationalstudyofprescription

dispensingaccuracyandsafetyin50pharmacies.JAmPharmAssoc(Wash),43(2),191200.

Flynn,E.A.,Barker,K.N.,Gibson,J.T.,&others(1996).Relationshipsbetweenambientsoundsand

accuracyofpharmacists'prescriptionfillingperformance.HumanFactors,38,614622.

Gernsbacher,M.A.(1984).Resolving20yearsofinconsistentinteractionsbetweenlexicalfamiliarity

andorthography,concreteness,andpolysemy.JournalofExperimentalPsychology:General,

113,256281.

Gonzalez,J.,&McLennan,C.(2007).Hemisphericdifferencesinindexicalspecificityeffectsinspoken

wordrecognition.JournalofExperimentalPsychology:HumanPerceptionandPerformance,33,

410424.

Grossberg,S.(1986).Theadaptiveselforganizationofserialorderinbehavior:Speech,languageand

motorcontrol.InE.C.Schwab&H.C.Nusbaum(Eds.),Patternrecognitionbyhumansand

machines:Vol.1,Speechperception(pp.187294).NewYork:AcademicPress.

Hagmann,P.,Cammoun,L.,Martuzzi,R.,Maeder,P.,Clarke,S.,Thiran,J.P.,etal.(2006).Hand

preferenceandsexshapethearchitectureoflanguagenetworksHumanBrainMapping,27,

828835.

Hedeker,D.,&Gibbons,R.D.(2008).SuperMixMixedEffectsModels,from

http://www.ssicentral.com/supermix/index.html

Hicks,R.,Becker,S.,&Cousins,D.(Eds.).(2008).MEDMARXdatareport.Areportontherelationshipof

drugnamesandmedicationerrorsinresponsetotheInstituteofMedicinescallforaction.

Rockville,MD:USPharmacopeia.

Hoffman,J.M.,&Proulx,S.M.(2003).Medicationerrorscausedbyconfusionofdrugnames.DrugSaf,

26(7),445452.

Hosmer,D.W.,&Lemeshow,S.(1989).Appliedlogisticregression.NewYork:JohnWiley&Sons.

Howes,D.H.(1957).OntherelationbetweentheintelligibilityandfrequencyofoccurrenceofEnglish

words.JournaloftheAcousticalSocietyofAmerica,29,296305.

21

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

IMSHealth(2008).2007channeldistributionbyU.S.dispensedprescriptionsRetrievedNovember17,

2008,from

http://www.imshealth.com/deployedfiles/imshealth/Global/Content/Document/Top

Line%20Industry%20Data/2007%20Channel%20Distribution%20by%20RXs.pdf

IMS,I.(2001).NationalPrescriptionAuditPlus.Chicago,IL:IMS.Inc.

Jurafsky,D.,&Martin,J.H.(2000).Speechandlanguageprocessing:Anintroductiontonaturallanguage

processing,computationallinguistics,andspeechrecognition.UpperSaddleRiver,NJ:Prentice

Hall.

Jusczyk,P.W.,&Luce,P.A.(2002).Speechperception.InH.Pashler&S.Yantis(Eds.),Stevens

HandbookofExperimentalPsychology,Volume1:SensationandPerception(3rd.ed.)(Vol.1,pp.

493536).NewYork:JohnWileyandSons.

Kleinbaum,D.G.(1994).Logisticregression:aselflearningtext.NewYork:SpringerVerlag.

Koczmara,C.,Jelincic,V.,&Perri,D.(2006).Communicationofmedicationordersbytelephone"writing

itright".Dynamics,17(1),2024.

Lambert,B.L.(1997).Predictinglookandsoundalikemedicationerrors.AmericanJournalofHealth

SystemPharmacy,54,11611171.

Lambert,B.L.(2008).Recentdevelopmentsinthepreventionanddetectionofdrugnameconfusion.In

R.W.Hicks,S.C.Becker&D.D.Cousins(Eds.),MEDMARXdatareport.Areportonthe

relationshipofdrugnamesandmedicationerrorsinresponsetotheInstituteofMedicinescall

foraction(pp.1015).Rockville,MD:CenterfortheAdvancementofPatientSafety,US

Pharmacopeia.

Lambert,B.L.,Chang,K.Y.,&Gupta,P.(2003).Effectsoffrequencyandsimilarityneighborhoodson

pharmacists'visualperceptionofdrugnames.SocialScience&Medicine,57,19391955.

Lambert,B.L.,Chang,K.Y.,&Lin,S.J.(2001a).Descriptiveanalysisofthedrugnamelexicon.Drug

InformationJournal,35,163172.

Lambert,B.L.,Chang,K.Y.,&Lin,S.J.(2001b).Effectoforthographicandphonologicalsimilarityon

falserecognitionofdrugnames.SocialScience&Medicine,52,18431857.

Lambert,B.L.,Donderi,D.,&Senders,J.(2002).Similarityofdrugnames:Objectiveandsubjective

measures.PsychologyandMarketing,19(78),641661.

Lambert,B.L.,Lin,S.J.,Gandhi,S.K.,&Chang,K.Y.(1999).Similarityasariskfactorindrugname

confusionerrors:Thelookalike(orthographic)andsoundalike(phonological)model.Medical

Care,37(12),12141225.

Lambert,B.L.,Lin,S.J.,&Tan,H.K.(2005).Designingsafedrugnames.DrugSafety(28),495512.

Lambert,B.L.,Lin,S.J.,Toh,S.,Luce,P.A.,McLennan,C.T.,LaVigne,R.,etal.(2005).Frequencyand

neighborhoodeffectsonauditoryperceptionofdrugnamesinnoise.AcousticalSocietyof

AmericaJournal,118(3),1955.Retrievedfrom

http://tigger.uic.edu/~lambertb/con_proceed/n05_173.pdf

Lambert,B.L.,Yu,C.,&Thirumalai,M.(2004).Asystemformultiattributedrugproductcomparison.

JournalofMedicalSystems,28(1),2954.

Luce,P.A.,Goldinger,S.D.,Auer,E.T.,Jr.,&Vitevitch,M.S.(2000).Phoneticpriming,neighborhood

activation,andPARSYN.PerceptionandPsychophysics,62,615625.

Luce,P.A.,&Pisoni,D.B.(1998).Recognizingspokenwords:Theneighborhoodactivationmodel.Ear&

Hearing,19(1),136.

NationalCenterforHealthStatistics(2001a).AmbulatoryHealthCareData:NAMCSDescription

RetrievedMay31,2001,2001,from

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/namcsdes.htm

22

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

NationalCenterforHealthStatistics(2001b).AmbulatoryHealthCareData:NHAMCSDescription

RetrievedMay31,2001,2001,from

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/about/major/ahcd/nhamcsds.htm

PennsylvaniaPatientSafetyAuthority(2006).Improvingthesafetyoftelephoneorverbalorders.

Patientsafetyadvisory,3(2),1,37.Retrievedfrom

http://www.psa.state.pa.us/psa/lib/psa/advisories/v3n2june2006/junevol_3_no_2_article_b_sa

fety_of_telphone_orders.pdf

Rodman,J.(2003).TheeffectofbandwidthonspeechintelligibilityRetrievedJune17,2005,from

http://www.polycom.com/common/pw_cmp_updateDocKeywords/0,1687,1809,00.pdf

Selvin,S.(1996).Statisticalanalysisofepidemiologicaldata.NewYork:OxfordUniversityPress.

SolucientInc.(2003).HospitaldrugutilizationdatabaseRetrievedMarch5,2004,from

http://www.solucient.com/solutions/Solucients_Databases.shtml

Sommers,M.S.,Kirk,K.I.,&Pisoni,D.B.(1997).Someconsiderationsinevaluatingspokenword

recognitionbynormalhearing,noisemaskednormalhearingandcochlearimplantusersI:The

effectsofresponseformat.EarandHearing,18,8999.

Storker,H.L.(2004).Methodsforminimizingtheconfoundingeffectsofwordlengthintheanalysisof

phonotacticprobabilityandneighborhooddensity.JournalofSpeech,Language,andHearing

Research,47,14541468.

TheJointCommission(2008).Accreditationprogram:Ambulatoryhealthcare,NationalPatientSafety

Goals.Retrievedfromhttp://www.jointcommission.org/NR/rdonlyres/979098FA74FD4F25

AF41EDD48FBD300E/0/AHC_NPSG.pdf

U.S.FoodandDrugAdministration(2008).PDUFApilotprojectproprietarynamereview.Federal

Register,74(189),5080650809.

Vitevitch,M.S.,&Luce,P.A.(1999).Probabilisticphonotacticsandneighborhoodactivationinspoken

wordrecognition.JournalofMemoryandLanguage,40,374408.

Vivian,J.V.(2004).Thirdpartyactions.USPharmacist,11,7478.

Wakefield,D.S.,Ward,M.M.,Groath,D.,Schwichtenberg,T.,Magdits,L.,Brokel,J.,etal.(2008).

Complexityofmedicationrelatedverbalorders.AmericanJournalofMedicalQuality,23(1),7

17.

Wiener,S.W.,Liu,S.,Nelson,L.S.,&Hoffman,R.S.(2004).NutropinorNeupogen?Amedicationerror

resultinginleukocytosis.AnnalsOfPharmacotherapy,38(4),721721.

Woolf,S.(2008).Themeaningoftranslationalresearchandwhyitmatters.JAMA,299(2),211.

23

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Table1.Demographiccharacteristics

Variable

Age

Gender

Male

Female

Race

Asian

Pacific

Islander

Black

White

Multiracial

Other

PracticeContext

Hospital

Clinic

Retail

Community

Other

Pharmacists

(n=62)

Physicians

(n=74)

Nurses

(n=70)

LayPeople

(n=43)

39.1(10.7)

44.3(10.9)

43.2(7.7)

29.8(12.3)

26

36

3

1

40.9

58.1

4.8

1.6

50

24

16

0

67.6

32.4

21.9

0

1

69

1

0

1.4

98.6

1.4

0

11

32

0

3

25.6

74.4

0

7.1

5

50

1

2

7

13

33

9

0

8.1

80.7

1.6

3.2

11.3

21.0

53.2

14.5

0.0

2

54

0

1

6

61

0

0

7

2.7

74.0

0

1.4

8.1

82.4

0

0

9.5

0

66

1

2

69

1

0

0

0

0

94.3

1.4

2.9

98.6

1.4

0

0

0

11

24

4

1

26.2

57.1

9.5

0.2

24

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Table2.Mean(standarddeviation)ofcontinuousindependentvariablesforcorrectandincorrect

responses

Clinicians(N=206)

Variable

Incorrect

Correct

(n=26776)

(n=13806)

R500Hz

25.92 (8.32)

26.07 (8.60)

L500Hz

24.12 (10.91)

R1000Hz

LayPeople(N=33)

Incorrect

Correct

(n=5111)

(n=1390)

0.44

12.94 (4.74)

12.65 (4.87)

0.26

23.92 (10.53)

0.37

11.91 (4.56)

11.50 (4.63)

0.09

17.72 (7.10)

17.43 (7.06)

0.05

8.02 (5.93)

8.07 (6.35)

0.87

L1000Hz

16.03 (7.45)

15.86 (7.42)

0.26

6.92 (5.73)

6.45 (5.83)

0.14

R2000Hz

10.85 (8.75)

10.71 (8.17)

0.38

4.35 (6.41)

3.83 (6.40)

0.13

L2000Hz

10.89 (8.97)

10.64 (8.49)

0.15

4.66 (6.76)

4.83 (6.63)

0.57

R3000Hz

10.96 (10.47)

11.14 (10.12)

0.45

3.37 (8.19)

2.49 (7.94)

0.04

L3000Hz

11.72 (11.10)

11.73 (10.89)

0.95

5.20 (8.19)

4.97 (7.86)

0.65

PhonemeFreq.

-0.11 (1.19)

-0.01 (1.10)

0.00

-0.14 (1.21)

0.07 (1.01)

0.00

BiphoneFreq.

-0.14 (1.03)

0.04 (1.02)

0.00

-0.14 (1.03)

0.08 (1.01)

0.00

Age

42.43 (10.13)

42.18 (10.06)

0.25

30.62 (12.42)

30.41 (11.86)

0.81

Experience

14.79 (10.19)

14.63 (10.15)

0.42

Familiarity

2.73 (2.36)

4.57 (2.65)

0.00

1.61 (1.44)

2.63 (2.28)

0.00

FWNP

0.53 (0.34)

0.60 (0.36)

0.00

0.55 (0.35)

0.56 (0.35)

0.34

RxFrequency

3.14 (1.65)

3.94 (1.76)

0.00

3.37 (1.75)

3.58 (1.65)

0.00

No.Phonemes

8.06 (2.29)

8.25 (2.80)

0.00

8.25 (2.53)

7.67 (2.22)

0.00

121.95 (57.13)

123.62 (57.22)

0.01

99.40 (547.09)

100.22 (57.39)

0.63

Trial

Note.R500Hzisthelowestnumberofdecibelsatwhicha500Hztonecouldstillbeheardintheright

ear.L500Hzistheleftear,etc.FWNPisfrequencyweightedneighborhoodprobability.RxFrequencyis

thelog(base10)ofthenationalprescribingfrequencyofthestimulusnames.Mixedeffectslogistic

regressionmodelswerebuiltwithSupermixwithonlyaninterceptandoneindependentvariableinthe

model.PvaluescomefromWaldtestsontheparameterestimateforthevariableinquestion.Lay

resultsareforn=33layparticpantsintheconditionwithbackgroundnoise.Therewere197

25

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

observationsforeachparticipant,sotherewere12,214pharmacistresponses,14,578physician

responses,and13,790nurseresponses.Seetextfordetails.

26

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Table3.Percentcorrectandincorrectresponsesbynominalcovariates

Variable

Clinicians(N=206)

%Cor. %Inc.

LayPeople(N=33)

%Cor.

%Inc.

0.0000

S/NRatio

0.0000

2dB

16.03

83.97

6.83

93.17

+3dB

36.10

63.90

21.32

78.68

+8dB

49.93

50.07

35.99

64.01

0.0000

Gender

0.31

Male

36.09

63.91

23.13

76.87

Female

32.78

67.22

20.91

79.09

0.0000

NameType

0.83

Brand

31.30

68.70

21.27

78.73

Generic

36.76

63.24

21.49

78.51

0.0000

Race

0.09

White

34.44

65.56

22.73

77.27

NonWhite

32.05

67.95

19.76

80.24

0.0000

Context

Hospital

30.28

69.72

Clinic

35.42

64.58

Retail

38.70

61.30

Other

36.88

63.12

Note.Probabilities(P)comefromWaldtestsonparameterestimatesgeneratedbySuperMixmixed

effectsregressionmodelswithonlyonepredictorvariableenteredatatime.Layresultsareforn=33lay

particpantsintheconditionwithbackgroundnoise.Adashindicatesthatvariblewasnotincludedinthe

analysis.

27

Pharmacists

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Physicians

Nurses

LayPeople

Figure1.Auditoryperceptionaccuracyasafunctionoffamiliarity.Foreachleveloffamiliarity,thedark

barrepresentsthepercentofincorrectresponsesasapercentofthetotalnumberofresponsesforthat

participantgroup.Thelightbarrepresentsthepercentofcorrectresponsesatthatfamiliaritylevel.The

linerepresentsthepercentcorrectatagivenleveloffamiliarity.Forlaypeople,dataareshownonly

fromparticipantsintheconditionwithbackgroundnoise.

28

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Figure2.Effectofsignalstrengthonaccuracyforpharmacists,physicians,nursesandlaypeople.Noise

wasplayedatmean65dBamplitudeforallparticipantgroups,exceptwherenotedforlaypeople.Sothe

threesignaltonoiseconditionscorrespondedto2dB,+3dBand+8dB.Laypeopleweretheonly

subgrouptestedwithoutnoise.

29

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Table4.Parameterestimatesforrandomeffectslogisticregressionmodelofaccuracyinauditory

perceptionforcliniciansandlaypeople

Variable

Clinicians(n=206)

OR(95%CI)

LayPeople(n=33)

OR(95%CI)

Intercept

0.21(0.150.30)

0.0000

0.03(0.10.8)

0.0000

S/NRatio(dB)

1.23(1.221.24)

0.0000

1.23(1.211.25)

0.0000

0.83(0.411.68)

0.31(0.061.60)

4.34(1.5112.53)

0.60

0.16

0.01

FWNP

FWNP2

FWNP3

RxFrequency

RxFrequency2

0.99(0.941.04)

1.02(1.011.02)

0.69

0.0000

Familiarity

Familiarity2

Familairity3

2.09(1.652.66)

0.83(0.780.90)

1.02(1.011.02)

0.0000

0.0000

0.0000

1.40(1.351.46)

0.0000

Num.Phonemes

Num.Phonemes2

0.82(0.780.86)

1.01(1.011.01)

0.0000

0.0000

0.92(0.890.94)

0.0000

PhonemeFreq.

BiphoneFreq.

0.73(0.680.78)

1.69(1.581.82)

0.0000

0.0000

1.29(1.201.37)

0.0000

0.995(0.9930.998)

1.04(1.031.06)

0.95(0.930.96)

0.0001

0.0000

0.0000

Nonwhite

Trial

Brand

0.79(0.700.89)

1.0009(1.00051.0013)

0.93(0.880.98)

0.0001

0.0000

0.01

Physician

Nurse

0.91(0.821.01)

0.66(0.590.74)

0.08

0.0000

1.11(1.041.17)

0.999(0.9980.999)

0.0007

0.002

0.96(0.940.99

1.03(1.011.05)

0.97(0.950.99)

1.02(1.001.04)

0.98(0.960.99)

1.02(1.001.04)

0.003

0.01

0.01

0.03

0.02

0.02

FamiliarityxS/NRatio

FamiliarityxPhonemeFreq.

FamiliarityxBiphoneFreq.

Age

Age2

R500Hz

R1000Hz

R2000Hz

L2000Hz

R3000Hz

L3000Hz

0.99(0.980.99)

30

0.0000

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Note.FWNP=frequencyweightedneighborhoodprobability.RxFrequencyisthelogbase10ofthe

maximumfrequencyobservedacross4differentprescriptiondatabases.S/Nratioisthesignaltonoise

ratio.Forrace,thereferencegroupwasandwhite(Caucasian).R500Hzisthelowestnumberofdecibels

atwhicha500Hztonecouldstillbeheardintherightear.L500Hzistheleftear,etc.Adashmeansthe

variablewasnotsignificantinthemodel.Superscriptnumbersareexponents,e.g.,FWNP2=FWNP

squared.Seetextfordetails.

31

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Table5.Summaryofauditoryperceptionresultsforpharmacists,physicians,nursesandlaypeople.

Variable

AllClinicians

(n=206)

34.23(6.82)

13.7149.75

17.23%

Pharmacists

(n=62)

39.14(5.83)

16.7549.75

18.5%

Physicians

(n=74)

34.46(5.52)

19.847.2

17.5%

Nurses

(n=70)

29.02(5.15)

13.7138.58

17.8%

LayPeople

(n=33)

21.38(5.36)

12.1830.46

15.3%

Accuracy(%)

Mean(s.d.)

Range

GoodnessofFit

Rootmean

squarederror

Mean

14.22%

15.5%

14.7%

14.6%

11.7%

absolute

error

0.47

0.49

0.48

0.42

0.32

R2predicted

vs.observed

SubstitutionErrors

Number(%of

4449(10.96)

1780(14.6)

1404(9.66)

1265(9.17)

243(3.73)

allresponses)

%ofincorrect

16.62

23.95

14.69

12.92

4.75

responses

No.with

3128

1266

975

887

153

knownfreq.

No.(%)in

2849(91.1)

1163(91.9)

883(90.6)

803(90.5)

114(74.5)

directionof

higher

frequency

name

Mean(s.d.)

2.40(1.80)

2.57(1.80)

2.27(1.76)

2.30(1.83)

1.54(2.06)

logfreq.

difference

between

targetand

substituted

name

Note.Forlaypeople,dataareshownonlyparticipantsintheconditionwithbackgroundnoise.

32

ErrorinSpokenMedicationOrders

Pharmacists

Physicians

Nurses

LayPeople

Figure3.Directionofsubstitutionerrorsasafunctionofdifferenceinlogprescribingfrequency.Thebar

chartisahistogramoffrequencydifferencesbetweenstimulusnamesandsubstitutednames.The

bottompartofeachverticalcolumnrepresentsthenumberoftimesthesubstitutednamewasless

frequentlyprescribedthanthestimulusname(leftaxis).Thetopportionrepresentsthenumberof

timesthesubstitutednamewasmorefrequentlyprescribedthanthestimulusname.Theline

representsthepercentofsubstitutionerrorswhereinthesubstitutednamewasmorefrequently

prescribedthanthestimulusname(rightaxis).Thegraphsshowthatwhenonenameismistakenfor

another,thesubstitutednameisalmostalwaysmorefrequentlyprescribedthanthenamewhichwas

misheard.Theprobabilityoferrorisnotasymmetricalfunctionofsimilarity.Relativelylowfrequency

namesareliabletobemisheardastheirhigherfrequencyneighbors,butnotviceversa.

33

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Kurt Salmon Etude Digital Pharma - WEB-VersionDocument32 pagesKurt Salmon Etude Digital Pharma - WEB-VersionainogNo ratings yet

- 国际玻璃陶瓷切削机SKII产品手册(英文)终版1025Document16 pages国际玻璃陶瓷切削机SKII产品手册(英文)终版1025Ivan LiwuNo ratings yet

- A Modification of The Altered Cast Technique PDFDocument2 pagesA Modification of The Altered Cast Technique PDFIvan LiwuNo ratings yet

- Grey Card Sasha HeinDocument15 pagesGrey Card Sasha HeinIvan LiwuNo ratings yet

- Dental Alloys Processing ManualDocument26 pagesDental Alloys Processing ManualIvan LiwuNo ratings yet

- Madiya Shah CVDocument2 pagesMadiya Shah CVapi-482395814No ratings yet

- Clinical Pharmacy Thesis PDFDocument8 pagesClinical Pharmacy Thesis PDFBestOnlinePaperWritersSingapore100% (2)

- Chapter6 - ExercisesDocument18 pagesChapter6 - Exercisesabdulgani11No ratings yet

- h33300 Sandoz Sodium Valproate Tablets Assesment ReportDocument14 pagesh33300 Sandoz Sodium Valproate Tablets Assesment Reportraghuraj75No ratings yet

- Medicare HMO PPO Pharmacy Directory enDocument287 pagesMedicare HMO PPO Pharmacy Directory enUlyssesm90100% (1)

- The Parents of A 21-Year-Old Woman Challenged The FDA. They Took The Authority ToDocument1 pageThe Parents of A 21-Year-Old Woman Challenged The FDA. They Took The Authority To2123 cndpbcthuocNo ratings yet

- Dawn Viveash CVDocument4 pagesDawn Viveash CVapi-275311205No ratings yet

- Application Form For The Academic Year2022-2023 September IntakeDocument6 pagesApplication Form For The Academic Year2022-2023 September IntakeFrolence SindaniNo ratings yet

- Basic Pharmacology NotesDocument83 pagesBasic Pharmacology NotesSanujNo ratings yet

- 3att 1435070407870 Katura ResumeDocument2 pages3att 1435070407870 Katura Resumeapi-362299218No ratings yet

- Pharmacovigilance: FROMDocument46 pagesPharmacovigilance: FROMmeyhal17No ratings yet

- Pharmacovigilance - Sem VIIIDocument4 pagesPharmacovigilance - Sem VIIIkuttiappan anithaNo ratings yet

- Smart Pumps Adult ITU Library v3Document73 pagesSmart Pumps Adult ITU Library v3Aqsa Ahmed SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- How To Improve Clinical Pharmacy Practice Using Key Performance IndicatorsDocument5 pagesHow To Improve Clinical Pharmacy Practice Using Key Performance IndicatorsTaufik Qur RaufNo ratings yet

- SIOP22 - EPoster ViewingDocument1,855 pagesSIOP22 - EPoster ViewingmgNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Goes Mobile Evolution of Teleconsultation and e Pharmacy in New NormalDocument66 pagesHealthcare Goes Mobile Evolution of Teleconsultation and e Pharmacy in New NormalRahul AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Practice ProblemsDocument2 pagesPractice ProblemsShemaj GurchumaNo ratings yet

- Business Flow ChartDocument14 pagesBusiness Flow ChartJose Ramir LayeseNo ratings yet

- 13 - Erna Fitriany - KtiDocument9 pages13 - Erna Fitriany - KtichemistryunesaNo ratings yet

- Dangerous DrugsDocument13 pagesDangerous Drugsjames van naronNo ratings yet

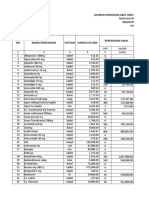

- Daftar Singkatan Nama Obat Puskesmas Tapos DepokDocument3 pagesDaftar Singkatan Nama Obat Puskesmas Tapos DepokSiti Anisa SaadahNo ratings yet

- Pharma NotesDocument8 pagesPharma NotesKylahNo ratings yet

- Internship Report Template - DPSDocument8 pagesInternship Report Template - DPSsiti nadzirahNo ratings yet

- Middle East and North Africa Pharmaceutical Industry WhitepaperDocument17 pagesMiddle East and North Africa Pharmaceutical Industry WhitepaperPurva ChandakNo ratings yet

- Do Ranap Untuk 11 Aug 21Document19 pagesDo Ranap Untuk 11 Aug 21farmasi rsud cilincingNo ratings yet

- Owen Osborn ResumeDocument2 pagesOwen Osborn Resumeapi-452848426No ratings yet

- Golongan Obat Casemix1Document31 pagesGolongan Obat Casemix1FiniNo ratings yet

- So Obat Depo IgdDocument65 pagesSo Obat Depo IgdIlham WJNo ratings yet

- Sno Grank Arno Name T.Mark Allotted To: CommunityDocument697 pagesSno Grank Arno Name T.Mark Allotted To: CommunityMohamed Imran ANo ratings yet