Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sustaining Operations With Low Oil Price

Sustaining Operations With Low Oil Price

Uploaded by

eandresmarCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sustaining Operations With Low Oil Price

Sustaining Operations With Low Oil Price

Uploaded by

eandresmarCopyright:

Available Formats

MANAGEMENT

Sustaining Economic Operations

With Low-Price Oil

Julian Pickering, CEO, Geologix Systems Integration, and Samit Sengupta, Managing Director, Geologix

What does USD 60/bbl crude mean to the

oil industry? We all know that oil prices

are volatile and that we have seen oil in

the USD 60/bbl price range before, but

not since 2008.

How did the upstream industry

respond then? The short answer is that

it did what it is doing now: Projects were

canceled, drilling and production were

cut, petroleum revenue taxes declined

significantly, and many staff in operator, service, and supporting companies

left the industry through redundancy or

early retirements. In short, the industry

felt extremely sorry for itself.

The big difference between 2008

and 2015 is the state of the global economy. In early 2008, global demand for

oil had been growing rapidly as countries such as China and India were evolving as major consumers and starting

to add significantly to the traditional

demand from highly developed countries. By the middle of the year, the

world oil market was thrown into financial chaos as many global economies

fell into recession. There was suddenly

a glut of oil as consumer demand plummeted. OPEC, which at the time controlled about 40% of global oil output,

responded by implementing its deepest ever cut in supply but even this did

not protect the price. There was just too

much oil available compared with global

consumption requirements.

By the end of 2012, statistics from

the US Energy Information Administration confirmed that the picture of global oil consumption had changed significantly. By this time, China had grown

to be the second-largest consumer of

world oil with Japan in third place and

India in fourth. This was a turning point

68

as the new world oil markets could no

longer accept major cuts in global production to bolster prices. So in 2015, it

looks as though the oil industry will have

to sustain production at a lower revenue

price, which means that it will have to

work smarter.

An important innovation since

2008 is the growth of integrated operations, also known as the "digital oil

field," which enables increased efficiency in operator companies. Integrated

operations allow businesses to optimize

their resources of staff, money, and facilities through enhanced collaboration,

improved workflows, and remote monitoring of critical operations in drilling

and production.

Adoption so far has been patchy:

Some companies have taken integrated operations fully on board while others have made only partial use of it and

some have not adopted it at all. In this

new low oil price climate, we believe

that integrated operations could be the

critical factor that enables sustainable

economic operations.

How Does Integrated

Operations Enable Success?

To function as a major enabler for

USD 60/bbl oil, an integrated operations

strategy must be engineered for success

right from the beginning, which means

following industry proven best practices.

They should include

t Clear deliverables with realistic

financial targets

t Technology definition based

on the corporate operating

philosophies

t Smart workflows to make the

best use of the technology

t A transition management plan

to define the people transition

process

The starting point is always a digital

oilfield strategy document. This is an open

and flexible document that companies

should expect to be constantly updated as

new technology is identified and operational priorities evolve. There is rarely a

clear endpoint to a digital oilfield project

because the factors are continually changing with time. It has been said that "a digital oilfield project starts but never ends!'

Once an operator is committed to integrated operations, it is constantly seeking new ways of increasing its efficiency in

more challenging environments.

Alongside the digital oilfield strategy document, there should be three

important project initiation documents

as follows:

t Maturity assessment. It

defines the current position

of the client organization in

digital oilfield adoption. The

maturity assessment should

be repeated at various intervals

in an implementation project

to measure progress. It takes

into account the human factors

and workflow issues in addition

to technology deployment.

t Information technology (IT)

readiness assessment. All

digital oilfield implementations

depend on the corporate

IT infrastructure and this

assessment is a measure of the

degree to which the current IT

infrastructure will support the

digital oilfield implementation

goals.

JPT AUGUST 2015

Process

People

Technology

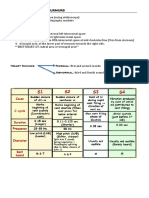

Fig. 1-The three-tier pyramid models depict the maturity levels of the people, process, and technology elements of a

digital oil field.

t Digital oilfield project

road map. It is a detailed

definition of how the digital

oilfield project will be

delivered. It covers technology

deployments, workflow

requirements, and people

transition management. The road

map must be based on the client's

functional requirements and

accounts for corporate priorities,

goals, and objectives.

It is widely accepted throughout the

industry that the three elements of people, process, and technology are all critical to a successful digital oilfield implementation. Fig. 1 shows these elements

as three-tier pyramids, with each layer

having a defined level of maturity. An

effective digital oilfield strategy should

aim to advance the maturity of all three

elements in parallel; any imbalance is an

indication of a weak strategy.

Geologix Systems Integration uses

the maturity assessment to build an

understanding of the maturity balance in

the pyramid model by interviewing operator staff and documenting "as is" work

processes and installed technology. We

then conduct a gap analysis to transition

JPT AUGUST 2015

the organization to a balanced maturity

including required people development,

"to be" work processes, and appropriate

technology. This enables a strategy to be

developed based on a process of continuous improvement, thus avoiding sudden

major changes to the organization.

The following case studies show the

results of stable and unstable maturity

pyramid models.

Case Study 1

In this case, all three areas were well balanced: The company understood its work

processes and had begun the process of

updating them to meet the new technology that would be introduced. Staff were

well engaged, recognized the potential

benefits of the digital oil field, and were

willing to adapt to new ways of working.

Here, it was easy for us to implement

integrated operations and move the company forward. The improvements in efficiencies took place in a relatively short

time frame and the company was able to

see a productivity benefit in fewer than

2 years.

Case Study 2

In this case, people, process, and technology were not in balance: The compa-

ny had invested in expensive technology

but only some staff were on board with

it; others were either wary of it or saw

it as a threat to their jobs. The management had a poor understanding of actual work practices and consequently had

not worked out how the new technology

would be used.

It is not uncommon for operator companies to demonstrate a much

higher maturity in the technology pyramid than in the people and process

pyramids and, as could be predicted,

this company was struggling to deliver

the expected value from its digital oilfield strategies.

In this case, we had to begin by

working with the company to get it to

understand its own work processes.

We also ran workshops to explain to

the staff the benefits of the digital oil

field and also to bring together different disciplines so that they could begin

to see how effective a collaborative way

of working might be.

Although it took a little longer, we

were eventually able to achieve a maturity balance and the company was not

only more profitable and efficient, but

also the staff were happier with how

things were being run.

69

'I

MANAGEMENT

Digital Oilfield Change

Requirements

The digital oil field has become a generic

term for the application of smart information technology to improve the safety, efficiency, and productivity of oil and

gas operations. It can deliver benefits

in many discipline functions including

reservoir characterization, well production, facilities optimization, and

export systems.

However, many oil and gas companies have failed to realize the true potential of the digital oil field because they

have overlooked one or more of the following prerequisites:

It The right staff for the job.

Digital oilfield processes

require people with different

skills from traditional oilfield

operations. There is a strong

focus on IT but the critical

factor is to merge IT skills with

discipline knowledge. Experience

has shown that it is relatively

easy to hire personnel who are

experts in IT or are experienced

in oilfield services, but it is much

more difficult to find experienced

oilfield workers who have a

mastery ofIT.

It Appropriate training. A

consequence of the above is

that many oil company personnel

will have to undergo training to

help them adapt to new ways

of working. For example, the

role of a site drilling manager is

very different from the role of a

drilling expert supporting many

drilling operations in a remote

collaboration center. Digital

oilfield implementation projects

must include a significant

element of training and

coaching of staff.

It One size does not fit all.

The design of a digital oilfield

solution must be matched to the

economics of the operation. In a

deepwater, tight gas well in the

US Gulf of Mexico, where labor

costs are high, it is easy to justify

smart well technology because

70

,I

the additional investment is

relatively small and the costs

can be recovered quickly.

However, in an onshore drilling

operation on a conventional well

in an area where labor costs are

relatively low, it becomes much

more difficult. It may be that

the investment is still economic

but almost certainly, it will

necessitate simpler technology.

It Internet access. It is easy to

assume that low-cost, highbandwidth access to the Internet

is readily available on a global

basis, but this is often not the

case in areas where oil and

gas resources are now being

developed. Poor communications

will degrade the value of digital

oilfield technology. This has

frequently resulted in the

need to develop a regional

communications infrastructure,

a time-consuming and very

expensive project in its own

right.

It New work processes.

Implementation of a digital

oil field requires new work

processes. There are many

cases in which significant

investment has been made

in technology such as smart

instrumentation in the field,

good communications, and a

well-designed collaboration

environment. But the

implementation is not a success

because the work processes are

not adapted to the technology.

Using good design practices,

changes in well performance

can be relayed to a collaboration

center on a continuous basis.

However, if support teams are

not organized to analyze this

information and take action

with minimum delay, the value is

lost totally. In fact, the situation

may be worse than not having

the technology at all, as field

personnel may make incorrect

assumptions about the level of

remote support. The danger is

that they do not pay the same

attention to the operation that

they would in the absence of

remote support.

Transition Management

and Training

The greatest challenge that most operators face in implementing a successful digital oilfield strategy is effective

people engagement. Many staff will not

have considered the consequences of the

digital oil field such as increased collaboration, remote working, information sharing, and "out of hours" decision making. It is important that staff

personalize the digital oil field and view

it from their own perspective, which

will probably be very different from the

company's perspective.

Normally, this transition is more significant for more experienced staff than

for younger staff. They should be asking

It What does my job look like in a

digital oilfield environment?

It Will I feel satisfied or will I feel as

though I am losing control?

It How will I relate to younger staff

who are likely to adapt much

more quickly?

It Will I be giving away personal

power by sharing information so

widely?

It Is this transition necessary as I

have been doing my job well for

the past 20-plus years?

It Am I willing to be a strong

advocate of the digital oil field

or will I take every opportunity

to show that it was the wrong

decision?

Training is a key component of all

digital oilfield implementation projects

and should be planned carefully. If an

operator company is new to digital oil

field, then the following topics must be

addressed in an introductory course:

It How do I start a project and who

will be involved?

It How do I engage all critical levels

in my company from senior

managers to field technicians?

JPT AUGUST 2015

t Does my company have the

necessary skills to support the

technology?

t Is my company prepared to suffer

reduced performance initially for

better returns later?

t Will the staff be responsive to

new work processes that may

be very different from the work

processes today?

Once the digital oilfield project is

established, the training requirements

shift toward design and operational

requirements. These may cover a broad

spectrum of knowledge depending on

the scope of the digital oilfield project

and the number of functional areas that

it will touch.

Can We Function Profitably

at Lower Oil Prices?

The next 2 years may present a more

financially challenging environment for

oil and gas operators. However, it does

provide an opportunity to smarten our

operations and to focus on increased

drilling and production efficiency, as well

as long-term recovery. This in turn will

help us to build a sustainable industry

exploiting both conventional and unconventional reserves and technologies

for the benefit of all our customers and

future generations.

If we can start viewing the digital oil field and the smart operations it

brings as "business as usual," then the

low oil price environment could be much

less threatening. JPT

Julian Pickering is the chief executive officer of Geologi x System s Integration, a

nonexecutive director of Geologix, and managing director of Digital Oilfield Solutions.

He has overseen the development of real-time operations centers and digital oilfield

workflow and transition management projects in several major oil and gas companies.

He was chairman of the Digital Energy Subcommittee of the 2011.j SPE Annual

Technology Conference and Exhibition and formerly the chairman of the WITS ML

Executive Team . He previously worked for BP for 32 years and was the head of the

global digital drilling and completions program and the head of BP's Field of the

Future facilities program .

Samit Sengupta, managing director of Geologix, has more than 30 years' experience

in the upstream sector of the oil and gas industry. He worked in the subsurface

data acquisition and analysis industry in Australasia, the US, Africa, and Europe with

Schlumberger, Gearhart, and Halliburton before creating Geologi x, an international

company providing integrated software and services that include well log authoring,

data management, and real-time monitoring. He holds a degree in civil engineering

from the Institute of Technology Bombay.

Society of Petroleum Engineers

Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition

Houston, Texas, USA 28-30 September 2015

George R. Brown Convention Center www.spe.org/go/atcelSj

"

JPT AUGUST 2015

71

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- CrystalMaker TutorialDocument38 pagesCrystalMaker TutorialCatPapperNo ratings yet

- Constant Flow Valves: Standard Features (Sizes 1/2" - 4") Sample SpecificationDocument5 pagesConstant Flow Valves: Standard Features (Sizes 1/2" - 4") Sample SpecificationeandresmarNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Pressure RegulationDocument7 pagesFundamentals of Pressure Regulationeandresmar100% (1)

- Constant Flow Valves: General DescriptionDocument4 pagesConstant Flow Valves: General DescriptioneandresmarNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Ceramic Sand Screens - 3M - Sand Control SASDocument19 pages2016 - Ceramic Sand Screens - 3M - Sand Control SASeandresmarNo ratings yet

- First Project of Auto-Injection in Patagonia Argentina: January 2017Document12 pagesFirst Project of Auto-Injection in Patagonia Argentina: January 2017eandresmarNo ratings yet

- Recuperacion SecundariaDocument40 pagesRecuperacion SecundariaeandresmarNo ratings yet

- 42-Zonal Water Injection Technology For Highly-Deviated Wells - PWRIDocument4 pages42-Zonal Water Injection Technology For Highly-Deviated Wells - PWRIeandresmarNo ratings yet

- Pressure Loss CorrelationsDocument57 pagesPressure Loss Correlationseandresmar100% (1)

- Artificial Lift For High Volume Production (Oilfield Review)Document15 pagesArtificial Lift For High Volume Production (Oilfield Review)eandresmarNo ratings yet

- Fiber Optic SensingDocument7 pagesFiber Optic SensingeandresmarNo ratings yet

- Advances in Artificial Lift TechnologyDocument3 pagesAdvances in Artificial Lift TechnologyeandresmarNo ratings yet

- TOC Cleaning ValidationDocument6 pagesTOC Cleaning Validationjljimenez1969100% (1)

- Pulkit Sharma TuesdayDocument29 pagesPulkit Sharma TuesdaysohailNo ratings yet

- Chemical EnergerticsDocument24 pagesChemical EnergerticsAnotidaishe ChakanetsaNo ratings yet

- Shadowrun - The Shadowrun Supplemental 09Document41 pagesShadowrun - The Shadowrun Supplemental 09Nestor Marquez-DiazNo ratings yet

- Lapidary Works of Art, Gemstones, Minerals and Natural HistoryDocument132 pagesLapidary Works of Art, Gemstones, Minerals and Natural HistoryWalterNo ratings yet

- Telepathy 101 Primer EnglishDocument285 pagesTelepathy 101 Primer EnglishDavid WalshNo ratings yet

- Problem: Wiring, Estimation and Costing of Architecture Block (First Floor)Document18 pagesProblem: Wiring, Estimation and Costing of Architecture Block (First Floor)Anand SinhaNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Word DocumentDocument18 pagesNew Microsoft Word DocumentSreekanth PagadapalliNo ratings yet

- Instron 3367 Frerichs GuideDocument9 pagesInstron 3367 Frerichs GuideNexhat QehajaNo ratings yet

- 1 Soal PrediksiDocument371 pages1 Soal PrediksiJanuar IrawanNo ratings yet

- J.saintifika Uji Bioavailabilitas Dan BioekivalensiDocument8 pagesJ.saintifika Uji Bioavailabilitas Dan BioekivalensiAhmad MujahidinNo ratings yet

- Learning Plan CLE-9Document5 pagesLearning Plan CLE-9Caren PondoyoNo ratings yet

- What Is Pure Substance?: Pure Substances Are Substances That Are Made Up of Only One Kind ofDocument3 pagesWhat Is Pure Substance?: Pure Substances Are Substances That Are Made Up of Only One Kind ofNi Made FebrianiNo ratings yet

- Consolidation (2) - 4th SEMDocument3 pagesConsolidation (2) - 4th SEMDipankar NathNo ratings yet

- TP-Link WiFi 6E AXE5400 PCIe WiFi Card - User GuideDocument23 pagesTP-Link WiFi 6E AXE5400 PCIe WiFi Card - User GuidehelpfulNo ratings yet

- Affinity DiagramDocument27 pagesAffinity DiagramIcer Dave Rojas PalmaNo ratings yet

- Analysis Wind Load Uniform Building Clode UbcDocument1 pageAnalysis Wind Load Uniform Building Clode UbcPapatsarsa SrijangNo ratings yet

- 7th Heart Sounds and MurmursDocument6 pages7th Heart Sounds and MurmursbabibubeboNo ratings yet

- GDM 24064 02Document31 pagesGDM 24064 02Fábio Vitor MartinsNo ratings yet

- Review On Animal Tissues PDFDocument7 pagesReview On Animal Tissues PDFTitiNo ratings yet

- NTN TR73 en P014Document6 pagesNTN TR73 en P014harshal161987No ratings yet

- Grade 3.strawberry Time - Posttest.silentDocument3 pagesGrade 3.strawberry Time - Posttest.silentJean Claudine Manday100% (1)

- Non Verbal CommunicationDocument26 pagesNon Verbal Communicationrooroli74No ratings yet

- Wall Colmonoy - Properties of Hard Surfacing Alloy Colmonoy 88 - July 2019Document8 pagesWall Colmonoy - Properties of Hard Surfacing Alloy Colmonoy 88 - July 2019joseocsilvaNo ratings yet

- T50e Replace DriveDocument24 pagesT50e Replace DrivevcalderonvNo ratings yet

- Swamy JPC-CDocument33 pagesSwamy JPC-Cvishnu shankerNo ratings yet

- TurbineDocument8 pagesTurbineJay Patel100% (1)

- Brunswick SuppliesDocument41 pagesBrunswick SuppliesNathan Bukoski100% (2)

- Lumina Homes PDFDocument1 pageLumina Homes PDFDestre Tima-anNo ratings yet