Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and An

Jasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and An

Uploaded by

derfghOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and An

Jasonis Et Papisti, A Dialogue Between A Jewish Christian (Jason) and An

Uploaded by

derfghCopyright:

Available Formats

THE ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCl PHILO, AND

ANASTASIOS THE SINAITE

I

One of the lost Christian works of the second century is the Altercatio

Jasonis et Papisti, a dialogue between a Jewish Christian (Jason) and an

Alexandrian Jew (Papiscus) which ends with the conversion of the latter.

Our earliest reference to it is in Origen's Contra Celsum.1 Celsus singles

it out for ridicule (for "pity and hatred" are his words) but Origen

describes it as undeserving of his adversary's contempt: "In it a Christian is described as disputing with a Jew from the Jewish Scriptures and

as showing that the prophecies about the Messiah fit Jesus; and the

reply with which the other man opposes the argument is at least neither

vulgar nor unsuitable to the character of a Jew." Nevertheless, Origen

had no great opinion of the work; for he also says that "although it could

be of some help to the simple-minded multitude in respect of their

faith," it "certainly could not impress the more intelligent." It must,

however, have indeed become popular, since it was translated into Latin

and we have the preface to that Latin version2 in which the dialogue is

called famous and splendid. It is from this preface that we learn that the

Christian was Jewish and the Jew Alexandrian, which suggests an

Alexandrian provenance for the work, though Maximus the Confessor,

writing in the seventh century, attributes it to Aristo of Pella, adding,

tantalizingly, that Clement of Alexandria attributed it to Luke the

Evangelist in his sixth book of the Hypotyposes (also, of course, lost).8

We may have another reference to this work and its author in the

Chronicon Paschale for the year 134.4

Contra Celsum 4, 52 (GCS, Orgenes 1, 325; Chadwick 226-27).

Ad Vigilium 8 (CSEL, Cypriani opera 3, 128-29).

3

Scholia in Lib. de mystica theologia 1 (PG 4, 421-22). There are some scattered and not

very impressive witnesses to a tradition that Luke evangelized Egypt and/or Alexandria,

such as the Constitutiones apostolicae 7, 46, and a number of ms. titles and scholia which

specify a sojourn in Alexandria {PG 1, 1051-52). Symeon Metaphrastes gives more details,

but he is generally thought to have misunderstood the traditions about Luke's activity (PG

115, 1136). It must be noted that Maximus may have misread Clement or that we may be

misreading Maximus, whose text, if but slightly amended (hon for hn), would yield: "Now

I read 'seven heavens' in the dispute between Papiscus and Jason which was written by

Aristo of Pella, [the Jason] whom Clement of Alexandria says, in the sixth book of Hypotyposes, St. Luke wrote about (in Acts 17, 5-9)."

*PG 92, 620. The text reads: "In this year Apelles and Aristo, whom [plural] Eusebius

the son of Pamphilus mentions in his ecclesiastical history, presents [sic: in the singular] a

carefully prepared defense (apologias syntaxin) concerning our religion to the emperor

Adrian." Eusebius does not mention anyone named Apelles and it has been suggested that

the text originally read not Apelles but ho Pellaios . . . hou.

2

287

288

THEOLOGICAL STUDIES

There are only three certain citations extant from the dialogue:5

Jerome refers to it twice and Maximus once. Eusebius, who never

mentions the dialogue itself, notes that Aristo of Pella tells about

Hadrian's decree forbidding the Jews further access to Jerusalem,6 but

this is not sufficient reason to suppose that the dialogue contained an

account of this event, since Aristo may well have written more than one

work. The citations in Jerome and Maximus are very brief. In his

Commentary on Galatians Jerome wrote: "Memini me in Altercatione

Jasonis et Papisci, quae Graeco sermone conscripta est, ita reperisse

Loidoria Theou ho kremamenos, id est, maledictio Dei qui appensus

est." In the Questions about Genesis Jerome again refers to the work by

title and says that it read Gn 1:1 as "In Filio fecit Deus coelum et

terrain," which he rejects as a reading, and he notes that Tertullian in

the Contra Praxean and Hilary "in expositione cuiusdam psalmi" also

give the reading found in the dialogue. Jerome is mistaken in what he

says about these other authors, and it is well to keep in mind that when

he refers to the dialogue in the Commentary on Galatians, he explicitly

says that he "remembers" reading what follows. His memory was not

always exact and therefore we cannot be certain that the citations are

exact. Maximus, in his Scholia on the Pseudo-Areopagite's Mystical

Theology, states that he read the phrase hepta ouranous in the dialogue

of Papiscus and Jason.

From the passage in which Origen describes the dialogue one might

assume that the Christian speaks first and then the Jew, though we would

have to suppose another similar cycle if, as the Latin preface tells us,

Papiscus received the grace of faith. That same preface, however, inti

mates that the order of speaking was Papiscus first and then Jason:

"Probat hoc scriptura concertationis ipsorum, quae collidentium inter se

Papisci adversantis ventati et Iasonis adserentis et vindicantis dispositionem et plenitudinem Christi Graeci sermonis opere signata est." Both

descriptions seem to suggest that each party spoke uninterruptedly.

II

7

The lost dialogue may yet be recovered from oblivion. At the end of

the nineteenth century it seemed as though perhaps it had been.

Between 1880 and 1900 notice of the existence of several copies of "a

dialogue between the Jews Papiscus and Philo and a Christian monk"

(named Anastasius in some mss.) was brought to the attention of the

5

All these citations may conveniently be found in PG 5, 1277-86.

Historia ecclesiastica 4, 6, 3.

7

As A. Lukyn Williams notes, "it may still be hidden in some library" (Adversus

Judaeos [Cambridge, 1935] p. 30).

ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCI

289

scholarly world by Th. Zahn,8 A. Harnack,9 A. C. McGiffert,10 and E. J.

Goodspeed.11 The various manuscripts are located in Venice, Paris,

Moscow, Dresden, and Mt. Athos, or were at the time of Goodspeed's

article, which was, to my knowledge, the last contribution to the

discussion.12 The Venice and Dresden mss. are considered to be the

earlier witnesses to the original text, though they too differ from one

another in some respects. However, it is agreed that although the title of

this dialogue certainly owes something to the second century Altercatio,

the contents do not. The later dialogue is dated to the sixth or seventh

centuries. McGiffert sets the fifth century as the terminus a quo on the

basis of the use of the epithet aei parthenou for the mother of Jesus.13

None of the citations given by Jerome or Maximus appear in it nor any

approximations of them. Of interest, however, is the fact that throughout the dialogue there are only two speakers, Papiscus and the Christian

monk. Philo, whose name appears in the title, has no part in the

dialectical exchange.

What explanation can be given for this strange fact? Zahn and

Harnack see in the addition of Philo's name merely a desire to associate

Papiscus (an Alexandrian Jew, as we know from the Latin preface to the

Altercatio) with that other Alexandrian Jew whose fame was

widespread.14 McGiffert, taking his clue from the fact that there are but

two speakers and that the Christian was unnamed in the original edition

of the dialogue, thinks that the original title was Antibole Papiskou kai

Philnos, Philo being a Christian and not the renowned Jewish philosopher: "we know of a number of Christian Philos of the fourth and

following centuries . . . . When the Christian Philo meant in the title had

dropped out of memory, it would be quite natural to think, in connection

with this name, of the great Jewish philosopher and later editors or

copyists would then have before them the singular spectacle of an

*Acta Joannis (1880) p. liv, n. 2; cf. Forschungen zur Geschichte des neutestamentlichen Kanons 4 (1891) 321 ff.

9

Die berlieferung der griechischen Apologeten des zweiten Jahrhunderts in der alten

Kirche und im Mittelalter (TU 1 [1883] 115-30); Geschichte der altchristlichen

Literatur

bis Eusebius 1, 1, 95-96.

10

Dialogue between a Christian and a Jew Entitled Antibole Papiskou kai Philnos

Ioudain pros monachon tina (Marburg, 1889).

11

"Pappiscus and Philo," American Journal of Theology 4 (1900) 796-802.

12

Not, of course, that notice of it has been neglected (Lukyn Williams, cited above [n.

7], for instance, devotes a chapter to it), but in the sense that there has been no new light or

discovery brought to bear upon the existing material.

13

Op. cit., p. 43.

14

As Zahn (Acta Joannis, cf. . 8 above) puts it, Papiscus "mit seinem noch berhmteren Mitbrger und Glaubensgenossen Philo als Polemiker gegen das Christenthum

zusammengestellt. ' '

290

THEOLOGICAL STUDIES

anti-Jewish dialogue held between two Jews. The extension of the title,

when it was once thus interpreted, became of course a necessity."16 There

is another possibility which McGiffert did not consider: that the Philo

intended is the Alexandrian philosopher in his Christian guise;16 but I do

not wish to examine this possibility, because it seems very unlikely and

cannot be considered apart from the material yet to be dealt with in this

paper. The presence of Philo's name creates something of a problem,

whereas no one who has written on this dialogue doubts that the name

Papiscus is taken from the second century Altercatio,

III

No oneagain to the best of my knowledgehas introduced into the

discussion of the two dialogues (that of the second and that of the sixth

century) an excerpt from the Hodgos of Anastasius the Sinaite, which is

surely very relevant to it. I refer to that passage in chap. 14 in which

Anastasius reproduces part (the Jew's part) of a dialogue between

Mnason the disciple of the apostles and Philo "the philosopher and

unbelieving Jew."17 I present it here in my English translation of the

Greek given in Migne's faulty but not yet replaced edition of the text.

The translation is occasionally a bit free but always closer to the Greek

than the Latin version accompanying it in Migne.

I am going to adopt and appropriate the role of Paul of Samosata 18 for you, or,

better, that of the unbelieving Jew Philo, the philosopher; for he argued against

the divinity of Christ with Mnason, the disciple of the apostles, and called

Mnason dichrota:19 What argument, what sort of argument, and from what

15

Op. cit., pp. 39-40.

Photius is our principal source for the legend that Philo was converted to Christianity

(Bibliotheca, cod. 105), though it is implied by Eusebius (Hist. eccl. 2, 4, 2) and, very

clearly, by Anastasius the Sinaite (In Hexaemeron 1, 7), which, as we shall see, poses a

problem for this paper. An account of Philo's baptism is given in the Acta Joannis (Zahn,

pp. 110-12), though it is evident that pseudo-Prochorus knew nothing about Philo beyond

the fact that he was a learned Jew.

17

PG 89, 244-48.

18

Given the facts that Anastasius is relying upon his memory and that he begins this

passage with the intention of citing Paul of Samosata, one might suspect that the

statements he subsequently attributes to "Philo" are really those of Paul of Samosata; but

this seems to be impossible, because the fragments we have of the latter's writings (and I

refer the reader to H. J. Lawlor's "The Sayings of Paul of Samosata," JTS 19 [1917 ] 20-45,

115-20, which has not been surpassed as a basic presentation) make it clear that he could

never have attacked the divinity of Christ in the way "Philo" does here. The strongest

evidence of this lies in the fact that Patii of Samosata quite readily concedes that Jesus was

superior in every way to any other human being, specifically superior to Moses.

"Literally, "two-colored." The exact sense in this context is obscure. We can surmise

that "Philo" meant a "fence straddler," i.e., someone who claimed to believe in the God of

16

ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCI

291

source (comes) any argument to the effect that the Christ is God? Should you

adduce his birth from a virgin, without seed as they say, the begetting of Adam

(appears) more noble and more striking, a formation by the very hands of God

and a vivifie ation through God's own breath, and it was purer than the

nine-month fetation of Jesus in his mother (terminating in) filth and wails and

mess. Should you adduce the signs he performed after his baptism, I would say to

you that no one on earth ever performed such signs and wonders as did Moses for

a period of forty years. Should you then point out that Jesus raised the dead, well,

the prophet Ezekiel raised up from the dry bones of the army of dead men a

numberless people. Moreover, Jesus himself said that some men would perform

greater works than he.

Now if you tell us that Jesus was taken up into the heavens as God, surely the

prophet Elias was taken up more gloriously in a blazing chariot and with horses of

fire. Calling Jesus the God of heaven must be reckoned as the most outrageous of

your blasphemies, for God Himself said to Moses that "No man shall see my face

and live." Further, our Scripture witnesses that "No one has ever seen God.20 No

man has seen or is able to see God." How is it that Christian preachers are not

ashamed to proclaim Jesus as God? For it is said that God is a consuming fire.

Tell me, then, does a God of fire hunger? Does a God of fire thirst? Does a God of

fire spit? Is a God of fire circumcised and does he bleed? And does he cast on the

ground bits of flesh and blood and the refuse of the stomach? All such things were

cast to the ground by Jesus and were eaten up and consumed by dogs, sometimes

by wild beasts and birds, and trampled on by cattle. Every bit of his flesh that

was cast off and discarded, whether it was sputum or nail-cuttings or blood or

sweat or tears, was a part and portion naturally associated with the body and

sloughed off or discarded in due process of growth. Indeed you say that he was

like men in all things according to the flesh apart from sin. Yet you preach that

he who was dead for three days was God. And what sort of a God who is a

consuming fire can die? Why his very servants, the angels, cannot die, neither

can the evil spirits of the demons, nor, for that matter, the souls of men.

To press the matter, I ask: What sort of God, having the power of life and death,

would take to flightas Jesus fled from Herod lest he be put to death as an

infant? What sort of God is tempted by the devil for forty days? What sort of God

becomes a curse, which is what Paul says of Jesus? What sort of sinless God

commits sin? For, according to you, Jesus became sin for our sake. And if he is

God, how is it that he prayed to escape the cup of death? And his prayer was not

heard. If he is God, how can he speak as one abandoned by God: "O God, my

God, why have you forsaken me?" Is God abandoned by God? Does God need

God (as would appear) when he says "Do not abandon my soul to the nether

the Old Testament but who, nevertheless, attributed to this God attributes and activities

that were incompatible with His essence. The editor of this passage in Migne found the

word incomprehensible, but it is perfectly good Greek.

20

The Latin translation in Migne reads here "your Scripture," and surely with reason,

since the text given is from the fourth Gospel.

292

THEOLOGICAL STUDIES

world"? Is God (such as to be) tied up, and abused and despised and put to

death? If he was indeed God, he should have crushed those intending to take him

prisoner, just as the angel crushed the Sodomites (who threatened) Lot. But you

call the helplessness of Jesus "long-suffering."

There are many things to be said about this passage. First, that it

comes from the pen of a man whose work has been too long neglected and

about whom we know very little save that he lived in Alexandria during

the latter half of the seventh century and earned for himself the

reputation of a great theologian and polemicist. 21 The Hodgos was

written about 685 in the desert, where Anastasius had to rely on his

memory for the many patristic and conciliar texts he cites and which are

often enough, not surprisingly, found to be inaccurate. Nevertheless, it

is clear that his learning was vast and that he had read many works now

lost to us.

What is the work from which he has drawn this attack on the divinity

of Jesus? I suggest that it may have been the lost Altercatio Jasonis et

Papisci, One cannot but be struck by the fact that Anastasius is

reporting a dialogue between a Christian of the early second century (a

"disciple of the apostles," like Polycarp) who is otherwise completely

unknown but whose name is remarkably similar to Jason, and an

Alexandrian Jew whom Anastasius identifies with the great Philo. Only a

portion of the dialogue is given, but if we keep in mind that Anastasius is

quoting from memory, we may find in it two of the three phrases known

to have appeared in the lost Altercatio: "Philo" here alludes directly to

Gal 3:13 and uses Paul's word katara according to Anastasius. Jerome's

reference to the dialogue, which also assumes an allusion to Galatians,

gives a rather singular Greek translation of Dt 21:23 which does not

appear in Anastasius, but "Philo" does not here refer to the Old

Testament text, though it would be reasonable to suppose that the

passage Anastasius is attempting to recall read "What sort of God

becomes a curse, which is what Paul says of Jesus? Does not the

Scripture say that he who is hanged is the reproach of God?"

Maximus says that he read the phrase "seven heavens" in the

Altercatio. Anastasius reports Philo as stating: "Now if you tell us that

Jesus was taken up into the heavens as God, etc." The possibility that

Anastasius simply omitted the word "seven" here is very real. The notion

of seven heavens was a popular one in Jewish-Christian and Hellenistic

circles in the early centuries of this era.22

21

Cf. O. Bardenhewer, Geschichte der altkirchlichen Literatur 5 (Freiburg, 1932) 4146; M. Jugie, "Anastasio Sinaita," Enciclopedia cattolica 1, 1157-58.

22

Cf. J. Danilou, A History of Early Christian Doctrine 1 (London, 1964) 173-81.

ALTERCATIO JASONIS ET PAPISCI

293

The third phrase we know to have existed in the Altercatio, "In Filio

fecit Deus coelum et terram," does not appear in the passage from

Anastasius, but clearly it would be part of the Christian respondent's

argument, and none of that is given by the Sinaite.

I may be mistaken, but I do not think this passage, as a whole, bears

any resemblance, as an anti-Christian polemic, to other existing examples of the genre. Certainly it is very unlike the later dialogue published

by McGiffert. In terms of scornfulness, it is redolent of the attacks of

Celsus and Porphyry,23 and indeed, if it does derive from the Altercatio,

it could not have been this part of it which aroused Celsus' detestation

and pity. On the other hand, it conforms to Origen's judgment that the

arguments of Papiscus were not "unsuitable to the character of a Jew."

One wonders, too, if there is any significance to the fact that many of

the arguments used against the divinity of Jesus here are taken up by

Melito of Sardis as examples of the paradox inherent in the fact of

incarnation: "to take on flesh from the holy virgin"; "the invisible one is

seen"; "the impassable one suffers and does not take vengeance"; "the

deathless one dies."24 Are the paradoxes of such a nature that a Christian

writer who wanted to invent a dialogue between a coreligionist and a Jew

would easily seize upon them as objections to be placed in the mouth of

the latter? Very likely, but this is not to suggest that the invention was

Anastasius'. We are, I think, guaranteed that the Sinaite had read the

dialogue which he is excerpting by the reference he makes to "Philo's"

having called "Mnason" dichrota. This is too circumstantial and too

isolated a detail to be attributed to the whim and fancy of Anastasius.

If this identification of the passage from the Hodgos with part of the

lost Altercatio is correct, there nevertheless remain two problems that

call for some attempt at a solution. They are: (1) How do we reconcile the

Sinaite's acceptance here of Philo the philosopher with his inclusion of

Philo among the earliest Church writers in his exegetical work on the

Hexameron?25 (2) How are we to account for the various shifts and

displacements of the names of the disputants witnessed to by Anastasius

and the later, substitute dialogue?

With respect to the first problem, it must be remembered that if

Anastasius is calling upon his memory of the Altercatio, then he knows

that the Jewish disputantwhom he here identifies with Philowas

converted by the arguments of Jason (Mnason). In this respect the Philo

of this passage in the Hodgos is no different from the Philo of the Acta

Joannis who, before his baptism, prays that the Christian God forgive

23

Cf. P. de Labriolle, La reaction paenne (Paris, 1934).

Cf. R. M. Grant, Second-Century Christianity (London, 1957) pp. 75-76.

28

In Hexaemeron 1, 7; Greek text in E. Preuschen, Antilegomena (Giessen, 1901) p. 60.

24

294

THEOLOGICAL STUDIES

him "for all the things said by me against your (apostolic) preaching."26

The legend of Philo's conversion was known to Eusebius, Pseudo-Prochorus, and Photius;27 we may assume it was also known to Anastasius.

This readily explains how the same Philo can appear in his works both as

an anti-Christian polemicist and as a Christian apologist.

Howeverand now we enter into the problematic of the second

questionthere are at least two possible explanations for the substitution of Philo for Papiscus in the passage from Anastasius. The first, and

prima facie the simplest, is that just as Anastasius' memory was vague

about the name Jason, it completely faltered over the name of the Jewish

antagonist and could only recall that he was an Alexandrian. The

recollection that the great Philo, who was a contemporary of the apostles,

was a prominent Alexandrian Jewbefore his "conversion"would

remedy that lapsus memoriae. But we cannot prescind here from the

fact that by the seventh century there was a "'new" Altercatio in circulation which in its title combined the names of Papiscus and Philo without

giving the latter any role to play and without naming Jason at all. This

suggests that Anastasius is witnessing to an intermediate stage in the

history of the Altercatioone in which the name Jason still appeared

but in which Papiscus had been joined by Philo as another adversary,

for the obvious reason given by Zahn and Harnack. Anastasius, however, would have had before him in Alexandria both the old text and the

new title. Since it is obvious that the second-century dialogue disappeared and that a new one was probably created on the basis of the

partially remembered title of its predecessor, we can reasonably reconstruct the stages in the history of our documents:

1) The original Antibole between Jason and Papiscus, known to

Clement of Alexandria, Celsus, Origen, Celsus Africanus (who translated

it into Latin), Jerome, and Maximus Confessor.

2) The original Antibole with title altered to include Philo. Known to

Anastasius the Sinaite (?).

3) A new Antibole omitting the name of Jason but retaining the names

of Papiscus and Philo. The Christian disputant becomes "a certain

monk" subsequently given the name of Anastasius.

St. Michael's College

University of Toronto

J.

EDGAR BRUNS

26

Op. cit., p. 112: m orgisths epi t so theraponti pe pontn ton logon tn lalthentn hyp1 emou eis antilexin tes ses didaskalias.

27

See . 16 above.

You might also like

- The Jewish-Christian Dialogue Jason and Papiscus in Light of The Sinaiticus FragmentDocument26 pagesThe Jewish-Christian Dialogue Jason and Papiscus in Light of The Sinaiticus FragmentJonathan100% (2)

- Transcript of Records (Kováč)Document1 pageTranscript of Records (Kováč)martin_kovac9772No ratings yet

- New BCLP Speaker's OutlinesDocument63 pagesNew BCLP Speaker's OutlinesPalacio JeromeNo ratings yet

- Chrysostom - An Address On Vainglory and The Right Way For Parents To Bring Up Their ChildrenDocument38 pagesChrysostom - An Address On Vainglory and The Right Way For Parents To Bring Up Their ChildrenthesebooksNo ratings yet

- The Speeches of Acts - FF BruceDocument15 pagesThe Speeches of Acts - FF BruceTeofanes ZorrillaNo ratings yet

- FENTON, Terry ODED, B. - The Invention of Ancient Palestinians Silencing of The History of Ancient Israel - 2003Document20 pagesFENTON, Terry ODED, B. - The Invention of Ancient Palestinians Silencing of The History of Ancient Israel - 2003AhnjonatasNo ratings yet

- Etienne Gilson Terrors of 2000Document14 pagesEtienne Gilson Terrors of 2000derfghNo ratings yet

- Worship Song LyricsDocument6 pagesWorship Song LyricskupaloidNo ratings yet

- The Instruction You Obey Is Future You Create-Part 1 043Document6 pagesThe Instruction You Obey Is Future You Create-Part 1 043James SokhuniNo ratings yet

- Translation of Genesis Chapter 1 From English To Jamaican Dialect With HebrewDocument5 pagesTranslation of Genesis Chapter 1 From English To Jamaican Dialect With HebrewIAlderNo ratings yet

- Rigg1957 PAPIAS ON MARK PDFDocument23 pagesRigg1957 PAPIAS ON MARK PDFHaeresiologistNo ratings yet

- Pelikan Jaroslav The Odyssey of DionysianDocument14 pagesPelikan Jaroslav The Odyssey of DionysianM4R1U5iKNo ratings yet

- Ferrar. Eusebius: The Proof of The Gospel, Being The Demonstratio Evangelica. 1920. Volume 1.Document336 pagesFerrar. Eusebius: The Proof of The Gospel, Being The Demonstratio Evangelica. 1920. Volume 1.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (4)

- The Jewish Life of Christ being the SEPHER TOLDOT JESHU or Book of the Generation of Jesus: Translated from the HebrewFrom EverandThe Jewish Life of Christ being the SEPHER TOLDOT JESHU or Book of the Generation of Jesus: Translated from the HebrewRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Apocalypse of Daniel A Newly Discovered Syriac PseudepigraphonDocument10 pagesThe Apocalypse of Daniel A Newly Discovered Syriac PseudepigraphonAnonymous cvec0aNo ratings yet

- Tynbul 45 1 01 Fairweatherwm DoiDocument38 pagesTynbul 45 1 01 Fairweatherwm DoiPsalmist SpursNo ratings yet

- The Jewish Life of Christ being the SEPHER TOLDOT JESHU or Book of the Generation of JesusFrom EverandThe Jewish Life of Christ being the SEPHER TOLDOT JESHU or Book of the Generation of JesusG. W. FooteNo ratings yet

- Exposito Rs Greek T 02 NicoDocument970 pagesExposito Rs Greek T 02 NicodavidhankoNo ratings yet

- The Problem of Hebrews and OT InterpretationDocument5 pagesThe Problem of Hebrews and OT InterpretationOwenKermitEdwardsNo ratings yet

- High and LowDocument23 pagesHigh and LowCelso MangucciNo ratings yet

- Ur of The ChaldeansDocument12 pagesUr of The ChaldeansDavid Salazar100% (2)

- Late Antique Divi and Imperial Priests oDocument23 pagesLate Antique Divi and Imperial Priests oibasic8-1No ratings yet

- The Dead Sea Scrolls and The Hasmonean State. by HANAN ESHEL. (The Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. 60, Issue 2) (2009)Document3 pagesThe Dead Sea Scrolls and The Hasmonean State. by HANAN ESHEL. (The Journal of Theological Studies, Vol. 60, Issue 2) (2009)Joshua AlfaroNo ratings yet

- Strangers on the Earth: Philosophy and Rhetoric in HebrewsFrom EverandStrangers on the Earth: Philosophy and Rhetoric in HebrewsNo ratings yet

- The Epistolary Framework of Revelation: Can An Apocalypse Be A Letter?Document15 pagesThe Epistolary Framework of Revelation: Can An Apocalypse Be A Letter?Sam HadenNo ratings yet

- The Oxyrhynchus Logia and The Apocryphal GospelsDocument126 pagesThe Oxyrhynchus Logia and The Apocryphal GospelsthrockmiNo ratings yet

- Lorton 2011 PDFDocument4 pagesLorton 2011 PDFFrancesca IannarilliNo ratings yet

- Thomas Simcox Lea & Frederick Bligh Bond - Materials For The Study of The Apostolic GnosisDocument110 pagesThomas Simcox Lea & Frederick Bligh Bond - Materials For The Study of The Apostolic GnosisAugusto DerpoNo ratings yet

- Paradoxes of Solomon - Learning in The English RenaissanceDocument33 pagesParadoxes of Solomon - Learning in The English RenaissanceAmos Rothschild100% (1)

- Rofe - Historical Significance of SecondaryDocument10 pagesRofe - Historical Significance of SecondarySergey MinovNo ratings yet

- Universalism in Second IsaiahDocument22 pagesUniversalism in Second IsaiahRicardo Santos SouzaNo ratings yet

- Review of The New Testament: A Translation by David Bentley HartDocument5 pagesReview of The New Testament: A Translation by David Bentley HartEmad Samir FarahatNo ratings yet

- Und Seine Stelle in Der ReligionsgeschichteDocument17 pagesUnd Seine Stelle in Der ReligionsgeschichteYehuda GiraldoNo ratings yet

- Wilson, Rev. of Alpers, Untersuchungen Zu Johannes SardianusDocument2 pagesWilson, Rev. of Alpers, Untersuchungen Zu Johannes SardianusSanja RadovicNo ratings yet

- Authenticity of Mani's "Letter To Menoch"Document45 pagesAuthenticity of Mani's "Letter To Menoch"applicativeNo ratings yet

- The Jesus ForgeryDocument12 pagesThe Jesus ForgeryJeremy Johnson0% (1)

- Traditions. Volume I: Alternatives To The Classical Past in Late AntiquityDocument4 pagesTraditions. Volume I: Alternatives To The Classical Past in Late AntiquityRenan Falcheti PeixotoNo ratings yet

- Woodstock College and The Johns Hopkins UniversityDocument56 pagesWoodstock College and The Johns Hopkins UniversityvalentinoNo ratings yet

- The Johannine CommaDocument8 pagesThe Johannine Commalibreria elimTarijaNo ratings yet

- HebrewsDocument146 pagesHebrewsmarfosd100% (1)

- The Mystery of The Greek Letters A ByzanDocument9 pagesThe Mystery of The Greek Letters A ByzanExequiel Medina100% (2)

- The Epistle of James Authorship and Date PaperDocument49 pagesThe Epistle of James Authorship and Date Paperhowsoonisnow234100% (2)

- Second Epistle of ClementDocument32 pagesSecond Epistle of ClementBarry Opseth100% (1)

- Documentary HypothesisDocument9 pagesDocumentary HypothesisPaluri JohnsonNo ratings yet

- QumramDocument7 pagesQumramtecnico.carlosaguilarpNo ratings yet

- Derveni Papyrus New TranslationDocument33 pagesDerveni Papyrus New TranslationDaphne Blue100% (2)

- Lorein2003 The Antichrist in The Fathers and Their Exegetical Basis PDFDocument56 pagesLorein2003 The Antichrist in The Fathers and Their Exegetical Basis PDFApocryphorum LectorNo ratings yet

- Andrews University Seminary StudiesDocument13 pagesAndrews University Seminary StudiesSem JeanNo ratings yet

- Paul and The Popular Philosophers (Review) - Abraham J. Malherbe.Document2 pagesPaul and The Popular Philosophers (Review) - Abraham J. Malherbe.Josue Pantoja BarretoNo ratings yet

- Lettera AristeaDocument15 pagesLettera AristeadanlackNo ratings yet

- 2419 The Name of The Goddess of Ekron A New ReadingDocument5 pages2419 The Name of The Goddess of Ekron A New ReadingRoswitha GeyssNo ratings yet

- 2012-02-29 Amazing Proofs of Jesus! (Richardcarrier - Info)Document21 pages2012-02-29 Amazing Proofs of Jesus! (Richardcarrier - Info)Yhvh Ben-ElohimNo ratings yet

- Why Did Jesus Talk in ParablesDocument33 pagesWhy Did Jesus Talk in ParablesshowerfallsNo ratings yet

- Afonasin Religious MindDocument11 pagesAfonasin Religious MindMarco LucidiNo ratings yet

- Journey To Bethlehem. New York: Harperone, 2010. X + 157 PPDocument5 pagesJourney To Bethlehem. New York: Harperone, 2010. X + 157 PPAlessandro MazzucchelliNo ratings yet

- The Grammar of ProphecyDocument103 pagesThe Grammar of ProphecyDieter Leon Thom100% (1)

- The Secret Gospel of MarkDocument14 pagesThe Secret Gospel of MarkCorey Lee Buck100% (2)

- Apocrypha ArielDocument25 pagesApocrypha ArielEnokmanNo ratings yet

- Bright. St. Augustine 'De Spiritu Et Littera'. 1914.Document106 pagesBright. St. Augustine 'De Spiritu Et Littera'. 1914.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- Documentary Hypothesis Bible OnlineDocument6 pagesDocumentary Hypothesis Bible Onlineashleyfishererie100% (2)

- Paul DupontDocument18 pagesPaul DupontAbdoukadirr SambouNo ratings yet

- The Philosophy of Clement of Alexandria: E. F. OsbornDocument196 pagesThe Philosophy of Clement of Alexandria: E. F. OsbornnsbopchoNo ratings yet

- The Actual Achievements of Early Indo-Europeans, in Accurate Historical ContextDocument11 pagesThe Actual Achievements of Early Indo-Europeans, in Accurate Historical ContextderfghNo ratings yet

- Critical Review: Common Themes and Variations in The Rhodanese SuperfamilyDocument9 pagesCritical Review: Common Themes and Variations in The Rhodanese SuperfamilyderfghNo ratings yet

- Lucilia Sericata (Green Bottle Fly) of 87.5%, The Vinegar Fly (Drosophyla SP.) of 70% and TheDocument4 pagesLucilia Sericata (Green Bottle Fly) of 87.5%, The Vinegar Fly (Drosophyla SP.) of 70% and ThederfghNo ratings yet

- Tbeo/ogicaf Studies: Cont EntsDocument14 pagesTbeo/ogicaf Studies: Cont EntsderfghNo ratings yet

- Et Théorie Des Cordes: Quelques Applications Cours XIII: 18 Mars 2011Document24 pagesEt Théorie Des Cordes: Quelques Applications Cours XIII: 18 Mars 2011derfghNo ratings yet

- Et Théorie Des Cordes: Quelques Applications Cours III: 11 Février 2011Document32 pagesEt Théorie Des Cordes: Quelques Applications Cours III: 11 Février 2011derfghNo ratings yet

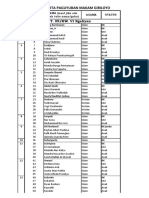

- Data PPPK GURU 2023Document64 pagesData PPPK GURU 2023Mang RiyadiNo ratings yet

- Fidelity To The Religious LifeDocument2 pagesFidelity To The Religious LifeQuo PrimumNo ratings yet

- World Religion 2Document8 pagesWorld Religion 2Angelyn LingatongNo ratings yet

- What Does It Mean To Be Born AgainDocument3 pagesWhat Does It Mean To Be Born AgainJohn Clifford MantosNo ratings yet

- ESSAY2 LifeDocument1 pageESSAY2 LifeRicky Jay PadasasNo ratings yet

- Nishant Navin - Inspirational QuotesDocument20 pagesNishant Navin - Inspirational QuotesnishantnavinNo ratings yet

- Tarkowski - Origins of Pre-Trib5 - Margaret Macdonald's Original Secret Coming VisionDocument5 pagesTarkowski - Origins of Pre-Trib5 - Margaret Macdonald's Original Secret Coming VisionMick RynningNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 - FaithDocument4 pagesLesson 1 - FaithJudyNo ratings yet

- W00-05 Introduction PDFDocument4 pagesW00-05 Introduction PDFRaymondMendiolaNo ratings yet

- Finding A Purpose in Your PainDocument11 pagesFinding A Purpose in Your PainFerdinand RegojosNo ratings yet

- Love Is Greater Than The Extraordinary Gifts of The SpiritDocument6 pagesLove Is Greater Than The Extraordinary Gifts of The SpiritGrace Church ModestoNo ratings yet

- Becoming Spiritually MindedDocument3 pagesBecoming Spiritually MindedChristopher LightwayNo ratings yet

- Triduum OfficeDocument33 pagesTriduum OfficeWhg JonesNo ratings yet

- Eschatology of Origen and MaximusDocument25 pagesEschatology of Origen and Maximusakimel67% (3)

- Youth Discipleship Level 1 - Pastor Kevin TzibDocument39 pagesYouth Discipleship Level 1 - Pastor Kevin TzibKevin Tzib100% (1)

- Psalm 133 OutlineDocument1 pagePsalm 133 Outlinealan shelbyNo ratings yet

- Novena To Blessed Thomas Maria FuscoDocument5 pagesNovena To Blessed Thomas Maria Fuscoanniealferez66No ratings yet

- Hausted - Wayne Grudem's Trinitarian Subordinationism - ATS 2016Document24 pagesHausted - Wayne Grudem's Trinitarian Subordinationism - ATS 2016javierNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of Qur'an - 1Document36 pagesBasic Concepts of Qur'an - 1tank ANo ratings yet

- Bishops Homily - 6th Sunday of EasterDocument24 pagesBishops Homily - 6th Sunday of EasterMinnie AgdeppaNo ratings yet

- Gorman - Seamless GarmentDocument13 pagesGorman - Seamless Garmentkansas07No ratings yet

- Module 6 CLE G7Document2 pagesModule 6 CLE G7ninreyNo ratings yet

- Keep Yourself From IdolsDocument11 pagesKeep Yourself From IdolsDeo Rafael100% (1)

- RW Vi RT 9 NgaliyanDocument3 pagesRW Vi RT 9 NgaliyanAnonymous o6JGM5HNo ratings yet

- Catechism 101:: Basic Catechism and The Sacrament of ConfirmationDocument53 pagesCatechism 101:: Basic Catechism and The Sacrament of ConfirmationBlue macchiatoNo ratings yet