Professional Documents

Culture Documents

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

Uploaded by

Mohamed HussienCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Answer PDFDocument17 pagesAnswer PDFميلاد نوروزي رهبرNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8: Risk and ReturnDocument56 pagesChapter 8: Risk and ReturnMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Multiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiDocument4 pagesMultiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiShahid NaikNo ratings yet

- Always Trust The Customer How Zara Has Revolutionized The Fashion Industry and Become A Worldwide LeaderDocument27 pagesAlways Trust The Customer How Zara Has Revolutionized The Fashion Industry and Become A Worldwide LeaderbeatriceNo ratings yet

- Black-Litterman Portfolio Allocation Stability and Financial Performance With MGARCH-M Derived ViewsDocument65 pagesBlack-Litterman Portfolio Allocation Stability and Financial Performance With MGARCH-M Derived ViewsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Introduction & Research: Factor InvestingDocument44 pagesIntroduction & Research: Factor InvestingMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- TN1 Basic Pre-Calculus: AcronymsDocument11 pagesTN1 Basic Pre-Calculus: AcronymsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- TN 2 - Basic Calculus With Financial Applications: 1 Functions and LimitsDocument16 pagesTN 2 - Basic Calculus With Financial Applications: 1 Functions and LimitsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Passive Investing: White PaperDocument11 pagesThe Dark Side of Passive Investing: White PaperMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Index Smart BetaDocument44 pagesIndex Smart BetaMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Giorgio S. Questa Induction To Quantitative Methods in FinanceDocument2 pagesGiorgio S. Questa Induction To Quantitative Methods in FinanceMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- From Smart Beta To Hard Reality: Executive SummaryDocument8 pagesFrom Smart Beta To Hard Reality: Executive SummaryMohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Transportation Methods PDFDocument24 pagesTransportation Methods PDFMohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Factor Model Notes:: R α β f β f …+β f ϵ R α β ' f ϵDocument2 pagesFactor Model Notes:: R α β f β f …+β f ϵ R α β ' f ϵMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Week 1 NotesDocument72 pagesWeek 1 NotesMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- PerformanceAnalytics PDFDocument214 pagesPerformanceAnalytics PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Probability Distribution and Statistics: Key Points of LearningDocument24 pagesProbability Distribution and Statistics: Key Points of LearningMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Efficient Market Theory and Evidence Implications For Active Investment Management PDFDocument93 pagesThe Efficient Market Theory and Evidence Implications For Active Investment Management PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- VX Python For Finance EuroScipy 2012 Y HilpischDocument47 pagesVX Python For Finance EuroScipy 2012 Y HilpischMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- 16 Mexico18 Dorantes PDFDocument43 pages16 Mexico18 Dorantes PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Computational Finance and Financial Econometrics With RDocument527 pagesIntroduction To Computational Finance and Financial Econometrics With RMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Philip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Document117 pagesPhilip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Mohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Ec371 Topic 3Document13 pagesEc371 Topic 3Mohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Correction For Exercise 7.2Document2 pagesCorrection For Exercise 7.2Mohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Chaos Theory and The Science of Fractals, and Their Application in Risk ManagementDocument78 pagesChaos Theory and The Science of Fractals, and Their Application in Risk ManagementMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument48 pagesTime Value of MoneyMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- A Portfolio Selection and Capital Asset Pricing Model: Luigi Buzzacchi, Luca L. GhezziDocument15 pagesA Portfolio Selection and Capital Asset Pricing Model: Luigi Buzzacchi, Luca L. GhezziMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument29 pagesFinancial Statement AnalysisMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Geogonia v. Court of Appeals DigestDocument6 pagesGeogonia v. Court of Appeals DigestJoy RaguindinNo ratings yet

- (3.) Interphil Laboratories Employees Union (Digest)Document2 pages(3.) Interphil Laboratories Employees Union (Digest)Dom Robinson BaggayanNo ratings yet

- SOA TemplateDocument1 pageSOA TemplateNoorasyaLya RozikinNo ratings yet

- Responsibility CentresDocument9 pagesResponsibility Centresparminder261090No ratings yet

- FLENDER D20-1 English HELICAL AND BEVEL GEARDocument25 pagesFLENDER D20-1 English HELICAL AND BEVEL GEARParcela Pinares NorteNo ratings yet

- CH 1 To 8Document4 pagesCH 1 To 8John WickNo ratings yet

- DEP 37.91.10.11-Gen Mobile Mooring Systems (Endorsement of API RP 2SK, API RP 2SM and API RP 2I)Document9 pagesDEP 37.91.10.11-Gen Mobile Mooring Systems (Endorsement of API RP 2SK, API RP 2SM and API RP 2I)Sd MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Quiz Techno Group1 ECEEEMEDocument2 pagesQuiz Techno Group1 ECEEEMEJohn Mark BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Bbsu Graduate Directory2 2016 1Document45 pagesBbsu Graduate Directory2 2016 1Ehsaan NooraliNo ratings yet

- 5 Characteristics-Defined ProjectDocument1 page5 Characteristics-Defined ProjectHarpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- 10-11-2016 - The Hindu - Shashi ThakurDocument26 pages10-11-2016 - The Hindu - Shashi ThakurSunilSainiNo ratings yet

- Khyber City Fee ScheduleDocument2 pagesKhyber City Fee ScheduleMohsin KhanNo ratings yet

- NetApp SnapMirrorDocument4 pagesNetApp SnapMirrorVijay1506No ratings yet

- It 41Document2 pagesIt 41रवींद्र वैद्यNo ratings yet

- Name Shehnila Azam Registration No# 45736 Course Cost and Management Accounting DAY Sunday Timing 3 To 6 Practice#1Document6 pagesName Shehnila Azam Registration No# 45736 Course Cost and Management Accounting DAY Sunday Timing 3 To 6 Practice#1yousuf AhmedNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 - Multivariable FunctionsDocument3 pagesTutorial 4 - Multivariable FunctionssurojiddinNo ratings yet

- Conjoint AnalysisDocument17 pagesConjoint Analysismark david sabellaNo ratings yet

- 2.0 Element of Conversion (Latest)Document5 pages2.0 Element of Conversion (Latest)b2utifulxxxNo ratings yet

- Franchise ProjectDocument3 pagesFranchise ProjectNicollete Limguangco SablaonNo ratings yet

- Kongunadu College of Engineering and Technology: Quantitative Aptitude PartnershipDocument16 pagesKongunadu College of Engineering and Technology: Quantitative Aptitude PartnershipGnana Prakasam RNo ratings yet

- Aca 2024 PlannerDocument1 pageAca 2024 Planneryfarhana2002No ratings yet

- Definition of IrrDocument3 pagesDefinition of IrrRajesh ShresthaNo ratings yet

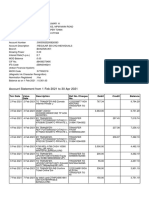

- Account Statement From 1 Feb 2021 To 30 Apr 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument11 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Feb 2021 To 30 Apr 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceUday AbhiNo ratings yet

- Touc Hin G Li Ves, Imp Ro Ving Life - Proc Ter & GambleDocument30 pagesTouc Hin G Li Ves, Imp Ro Ving Life - Proc Ter & Gamblechandni kundel75% (12)

- PCB Quote 1003Document1 pagePCB Quote 1003rhedmishNo ratings yet

- DBLDocument3 pagesDBLLeafe MendozaNo ratings yet

- Audit Non Conformance ReportDocument4 pagesAudit Non Conformance Reportbudi_alamsyah100% (2)

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

Uploaded by

Mohamed HussienOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

M09 Soln8117 06 SM C09

Uploaded by

Mohamed HussienCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 9

The Case for International Diversification

1. The domestic and foreign assets have annualized standard deviations of return of d = 15% and

f = 18%, respectively, with a correlation of = 0.5. The variance () of the portfolio invested

80% in the domestic asset and 20% in the foreign asset is

p2 = (0.82 d2 ) + (0.22 2f ) + (2 0.8 0.2 d f )

p2 = (0.82 152 ) + (0.2 2 182 ) + (2 0.8 0.2 0.5 18 15) = 200.16

p = 200.16, or 14.15%

2. a. For each portfolio, expected return is calculated using Equation 9.1, and portfolio standard

deviation is calculated using Equation 9.2. Expected returns and standard deviations for the

portfolios are listed in the following table.

Invested in

Asset 1

Invested in

Asset 2

Portfolio Expected

Return

Portfolio

Risk

100%

80%

0%

20%

10.00%

10.80%

10.00%

9.19%

60%

40%

11.60%

9.61%

50%

50%

12.00%

10.25%

40%

60%

12.40%

11.11%

20%

80%

13.20%

13.34%

0%

100%

14.00%

16.00%

b. The plot of the portfolios on a riskreturn graph is provided here:

Chapter 9

3. a.

The Case for International Diversification

For each portfolio, expected return is calculated using Equation 9.1, and portfolio standard

deviation is calculated using Equation 9.2. Expected returns and standard deviations for the

portfolios are listed in the following table.

When = 0.5:

Invested in

Asset 1

Invested in

Asset 2

Portfolio Expected

Return

Portfolio

Risk

100%

80%

0%

20%

10.00%

11.20%

14.00%

13.10%

60%

40%

12.40%

12.86%

50%

50%

13.00%

13.00%

40%

60%

13.60%

13.31%

20%

80%

14.80%

14.41%

0%

100%

16.00%

16.00%

b. For each portfolio, expected return is calculated using Equation 9.1, and portfolio standard

deviation is calculated using Equation 9.2. Expected returns and standard deviations for the

portfolios are listed in the following tables for various correlations.

When = 1.0:

Invested in

Asset 1

Invested in

Asset 2

Portfolio Expected

Return

Portfolio

Risk

100%

80%

0%

20%

10.00%

11.20%

14.00%

8.00%

60%

40%

12.40%

2.00%

50%

50%

13.00%

1.00%

40%

60%

13.60%

4.00%

20%

80%

14.80%

10.00%

0%

100%

16.00%

16.00%

49

50

Solnik/McLeavey Global Investments, Sixth Edition

When = 0:

Invested in

Asset 1

Invested in

Asset 2

Portfolio Expected

Return

Portfolio

Risk

100%

80%

0%

20%

10.00%

11.20%

14.00%

11.65%

60%

40%

12.40%

10.56%

50%

50%

13.00%

10.63%

40%

60%

13.60%

11.11%

20%

80%

14.80%

13.10%

0%

100%

16.00%

16.00%

When = 1.0:

Invested in

Asset 1

Invested in

Asset 2

Portfolio Expected

Return

Portfolio

Risk

100%

80%

0%

20%

10.00%

11.20%

14.00%

14.40%

60%

40%

12.40%

14.80%

50%

50%

13.00%

15.00%

40%

60%

13.60%

15.20%

20%

80%

14.80%

15.60%

0%

100%

16.00%

16.00%

Chapter 9

c.

4. a.

The Case for International Diversification

51

The graphs for Parts (a) and (b) illustrate that, holding all else constant, lower correlations

translate into lower levels of portfolio risk, without sacrificing expected return.

2f = 2 + s2 + 2 s = (8.5)2 + (5.5)2 + 2(0)(8.5)(5.5) = 102.5

f = 10.12%

Contribution of currency risk = 10.12 8.5 = 1.62%

b.

2f = 2 + s2 + 2 s = (8.5)2 + (5.5)2 + 2(0.25)(8.5)(2.5) = 125.9

f = 11.22%

Contribution of currency risk = 11.22 8.5 = 2.72%

c.

2f = 2 + s2 + 2 s = (8.5)2 + (5.5)2 + 2(0.45)(8.5)(5.5) = 60.4

f = 7.77%

Contribution of currency risk = 7.77 8.5 = 0.73%

d. When the correlation between the asset return, in local currency, and the exchange rate movement

is low enough, currency risk may actually reduce the asset risk measured in dollars. However, in

cases in which the correlation is zero or positive, asset risk in dollars is higher than asset risk in

local currency because of currency risk.

5. a.

If the correlation between stock market returns and exchange rate movements were equal to zero,

the dollar volatility of the German stock market would be

2f = 2 + s2 + 2 s = (18.2)2 + (11.7)2 + 2(0)(18.2)(11.7) = 468.13

f = 21.64%

b. Because the actual dollar volatility is only 20.4 percent, we conclude that the correlation between

stock market returns and exchange rate movements is negative.

6. a.

If the correlation between bond market returns and exchange rate movements were equal to zero,

the dollar volatility of the German bond market would be

2f = 2 + s2 + 2 s = (5.5)2 + (11.7)2 + 2(0)(5.5)(11.7) = 167.14

f = 12.93%

b. Because the actual dollar volatility is 13.6 percent, we conclude that the correlation between

bond market returns and exchange rate movements is positive. When the euro gets weaker, U.S.

investors lose on the exchange rate and also on bond market returns measured in euros. This can

be explained by the idea that a weak currency usually goes with rising interest rates (and negative

bond market return).

52

Solnik/McLeavey Global Investments, Sixth Edition

7. The best diversification vehicle is an asset whose value gets significantly higher when the rest of the

portfolios value is low, and thereby partially offsets the loss of other assets. The best vehicle is an

asset with a negative correlation (so it goes up when the portfolio goes down) and high volatility

(large upswings when the portfolio goes down). Thus the statement is correct.

8. a.

The markets that are highly correlated (currency-hedged) with Germany are the European

countries and, in particular, the French market (0.87) and the Swiss market (0.77). Both

Switzerland and France are countries bordering Germany, and their economies are highly

dependent on the German economy. Besides, Swiss companies are mostly multinationals that are

very active on the German market. France and Germany belong to the EU, while Switzerland

does not (although it has numerous accords with the EU). The strong linkage between EU

countries clearly shows up in the Exhibit.

Hong Kong (0.39) and Japan (0.42) have relatively low correlations. This reflects the fact that

these are markets with loose links to the German economy.

b. The markets that are highly correlated (currency-hedged) with the United States are the Canadian

market (0.73) and some European markets (e.g., 0.74 for the British market).

Canada is obviously highly dependent on the U.S. economy. Switzerland is a small economic

power with very active multinational groups on the U.S. market. The U.K. economy is very open

to international investments. It has a great number of banks, insurance companies, and other

financial institutions investing on the U.S. market, which explains the high correlation.

Italy (0.55) and Japan (0.41) have low correlations with the United States. Italy is a South

European-oriented economy with a weaker link to the U.S. economy. Its development is

explained by local factors such as integration into Europe. Japan has traditionally been less

correlated with the United States, in part because of the importance of regional factors.

9. A review of the correlations in Exhibit 9.5 indicates that correlations of the U.S bond market with

foreign bond markets are well below 0.50, when measured in dollar terms. These low correlations

can be attributed to the fact that national monetary/budget policies are not fully synchronized. The

conclusions reached regarding the risk-reducing benefits of low correlations in global equity markets

also apply to global bond markets. Foreign bonds are therefore a good vehicle of diversification and

can significantly reduce the volatility of the portfolio. This makes foreign bonds attractive to a U.S.

investor, despite foreign exchange risk.

10. Exhibit 9.5 indicates that correlation of the U.S. equity market with global bond markets is quite low,

suggesting that adding bonds from foreign countries can reduce overall global portfolio risk. Thus,

from the viewpoint of a U.S. investor, Exhibit 9.5 provides strong justification for including global

bonds in a global portfolio strategy. In addition, empirical research shows that a portfolio of global

stocks and bonds dominates U.S. stock/bond portfolios.

11. In general, over the long run, the performance of stock markets is closely tied to national economic

factors. For example, in the case of Japan, real average annual GDP growth was 4.51 percent from

1971 to 1980, and 4.15 percent from 1981 to 1990 (see Exhibit 9.11). These real GDP growth rates

dominated growth rates for the United States, Europe, and the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD) for the same periods. This is reflected in stock market

performance numbers presented in Exhibit 9.10. For the period from 1971 to 1990, the average

annual mean return for Japanese stocks was 20.68 percent, much higher than stock returns in the

United States and Europe. From 1991 to 2000, it was the United States that had the highest real GDP

growth rates and best-performing stock market.

Chapter 9

The Case for International Diversification

53

Economic flexibility is another important factor. Countries such as France, Canada, and Sweden have

suffered from wage and employment rigidities not typically faced in many emerging countries. This

economic flexibility is likely to reflect itself in stock market performance in the long run. Many

countries are improving their global competitiveness, which should be reflected in market valuation.

12. Currency fluctuations have an impact on the total return and volatility of foreign currencydenominated

investments. However, there are at least four reasons why currency risk is not a barrier to international

investment:

Market and currency risks are not additive. This is because the correlation between currency and

market movements is quite weak and sometimes negative. Consequently, the contribution of

currency risk to the risk of a foreign investment is quite small.

Currency risk can be hedged away by selling currency futures or forward contracts.

If foreign assets represent a small portion of the portfolio, then the contribution of currency risk is

insignificant (Jorion, 1989). Also, if the portfolio consists of multiple currencies, some portion of

the risk is diversified away.

Currency risk decreases with the length of the investment horizon, because exchange rates tend to

revert to fundamentals.

13. There is no doubt that financial markets are becoming increasingly interconnected worldwide. Some

of the reasons for this are as follows:

Free trade. Because of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and as a result of regional

agreements such as NAFTA, ASEAN, and the EU, national economies are opening up to free

trade. This has caused national economies to become more integrated.

International capital flows. The amount of foreign investment is growing rapidly on all national

markets. Profit opportunities across markets are being arbitraged away.

Capital market deregulation. Deregulation has opened markets to foreign investors, and markets

that used to be segmented are becoming more integrated.

Corporations are becoming more global. As corporations become more global, they derive

significant portions of their income from overseas, and thus valuations are impacted more by

global factors and less by country factors. This has caused stock-price correlations to increase,

because corporate valuations are determined by a similar set of factors.

14. Correlation breakdown is a reference to the finding that during periods of crisis, when market

volatility is high, correlations across markets increase dramatically. This phenomenon has been

documented during major market events, such as the October 1987 crash and the Asian markets

crisis of 1997.

The increase in correlations across international financial markets during periods of crisis is

problematic because one of the primary reasons for diversifying overseas is risk reduction due to low

correlations. It appears, however, that correlations rise at the worst possible time, causing the benefits

of international diversification to disappear when they are most needed. Further exacerbating the

situation is the finding that distributions of returns tend to have fat tails rather than being normal.

Fat tails imply that the occurrence of market crashes is likely to be more frequent than under

normality. This, in turn, suggests that periods of high correlations are more likely to occur.

15. There are a number of barriers to international investment, including the following:

Familiarity with foreign markets. Many investors are not familiar with business customs overseas

and are therefore inclined to invest in domestic companies.

Political risk. This is a major concern, especially in emerging markets in which political and economic

instability have had a debilitating impact on security prices in local-currency and dollar terms.

54

Solnik/McLeavey Global Investments, Sixth Edition

Market efficiency. Liquidity risk is a major concern for investors venturing overseas because it

limits the ability of large investors to change asset allocations without signaling their actions to the

rest of the market. Capital controls are another source of liquidity risk because such controls limit

the repatriation of funds to the home country. In many countries, market efficiency is limited by

the fact that companies do not provide accurate and timely information. Price manipulation and

insider trading also limit market efficiency and benefit local investors at the expense of foreign

investors.

Regulations. Certain countries have regulations that inhibit foreign investment by limiting the

amount of overseas investment by local investors. Other countries limit the amount of foreign

ownership in domestic firms. These regulations generally limit the scope of international

investment.

Transactions costs. Transactions costs tend to be higher for international investments relative to

domestic investments. The higher transactions costs for international investments are due to higher

brokerage commissions and market impact, custody costs, and higher portfolio management fees.

Taxes. Taxes have a relatively small impact on the international investment decision. Withholding

taxes on dividends are typically reclaimed after a few months, but this represents an opportunity

cost because funds are tied up.

Currency risk. Although currency risk can be hedged, it does lead to additional administrative and

trading costs and thus adds to the overall cost of international investment.

16. In the past, pure country return correlations were much lower than pure industry return correlations.

Exhibit 9.14 shows that country correlations were lower than industry correlations between 1993 and

1999. Thus, for this period, the two-step procedure of first determining country allocations and then

industry allocations within each country was justified. However, Exhibit 9.14 also shows that since

mid-2000, industry correlations have been lower than country correlations. This means that while

diversification across countries is still important, diversification across industries has become more

important for risk-diversification purposes. In addition, when you consider that many corporations

now operate globally while still remaining focused in their core businesses, it becomes difficult to

determine the level of exposure to country factors. In this global environment, industries cut across

countries. Thus, a better approach to global portfolio selection, one that can capture full benefits of

international risk diversification, is a cross-industry, cross-country approach.

17. The distribution of returns in emerging markets is not symmetric. This calls into question the

applicability of the standard deviation as a measure of risk, because the standard deviation is

appropriate only if returns are normal. Emerging markets do have a higher standard deviation than

developed markets, because they are more volatile. But their return distribution also have fat tails,

meaning that there is a significant probability of a large shock, positive or negative. Emerging

markets go through periods of exuberance with huge positive returns and periods of crisis with huge

negative returns. The return distribution is also asymmetric (skewed), because there can be years

where the returns exceed 100 percent while the maximum loss is constrained to be less than

100 percent.

Furthermore, there are political risks in many emerging markets. The development of many emerging

markets is tied to political and economic reforms. However, economic growth can result in serious

imbalances that lead to political and social upheavals. Foreign investors could be subject to currency

and capital controls that limit their ability to repatriate invested capital or profits. Thus, political risk

must be taken into account when measuring risk in emerging markets.

Chapter 9

The Case for International Diversification

55

Studies have shown that emerging markets are subject to periodic, prolonged crises that tend to

spread to all other emerging markets in the region. Another issue that complicates the picture is the

finding that for emerging markets, local stock markets changes and exchange rate movements

display positive correlations, meaning that foreign investors suffer more from currency risk in

emerging markets.

18. Although it is true that local risks in emerging markets are high because of volatility, liquidity, and

political risk, correlations between emerging markets and developed markets are low. The low

correlations mean that some of the higher risk in emerging markets can be diversified away in a

global portfolio. Thus, the contribution of emerging markets to the total risk of a global portfolio is

not likely to be very large.

Expected returns in emerging markets are higher because the economies of emerging markets are

expected to grow at a higher rate than developed markets. Emerging market economies are expected

to grow at a higher rate because of lower labor costs, lower levels of unionization, and rapid growth

in domestic demand. In addition, the introduction of pension funds and the trend to privatization have

benefited local emerging stock markets.

Another factor that favors emerging-market investment is research that indicates emerging markets

are somewhat segmented from international markets. Segmented markets imply that assets are

mispriced and may offer portfolio managers investment opportunities at attractive valuations.

19. a.

Arguments in favor of adding international securities include the following:

i. Benefits gained from broader diversification, including economic, political and/or

geographic sources

ii. Expected higher returns at the same or lower (if properly diversified) level of portfolio risk

iii. Advantages accruing from improved correlation and covariance relationships across the

portfolios exposures

iv. Improved asset allocation flexibility, including the ability to match or hedge non-U.S.

liabilities

v. Wider range of industry and company choices for portfolio construction purposes

vi. Wider range of managers through whom to implement investment decisions

vii. Diversification benefits realizable despite the absence of non-U.S. pension liabilities

At the same time, there are a number of potential problems associated with moving away from a

domestic-securities-only orientation:

i. Possible higher costs, including those for custody, transactions, and management fees

ii. Possible reduced liquidity, especially when transacting in size

iii. Possible unsatisfactory levels of information availability, reliability, scope, timelessness, and

understandability

iv. Risks associated with currency management, convertibility, and regulations/controls

v. Risks associated with possible instability/volatility in both markets and governments

vi. Possible tax consequences or complications

vii. Recognition that EAFE underperformed in the 1990s

56

Solnik/McLeavey Global Investments, Sixth Edition

b. A policy decision to include international securities in an investment portfolio is a necessary first

step to actualization. However, certain other policy-level decisions must be made prior to

implementation. That set of decisions would include the following:

i. What portion of the portfolio shall be invested internationally, and in what equity and fixedincome proportions?

ii. Shall all or a portion of the currency risk be hedged, or not?

iii. Shall management of the portfolio be active or passive?

iv. Shall the market exposures be country/marketwide (top-down) or company/ industry-specific

(bottom-up)?

v. By what benchmarks shall results be judged?

vi. How will manager style be incorporated into the process?

vii. How will the process reflect the important differences in risk between developed non-U.S.

markets and emerging markets?

Until decisions on these additional policy-level issues have been made, implementation of

the basic decision to invest internationally cannot begin.

20. a.

The consultant is alluding to the behavior of cross-country equity return correlations during

different market phases, as reported in various research studies. Specifically, the consultant is

referring to the fact that correlations in down markets tend to be significantly higher than

correlations in up markets. In other words, equity markets appear to be correlated more when

they are falling than when they are rising.

b. Although cross-country equity return correlations can vary significantly in the short run, they

remain surprisingly low when measured over long periods of time. This implies that, from a

policy standpoint, international investing still offers the potential to construct more efficient

portfolios, in a riskreturn trade-off sense, than ones constructed using domestic assets only.

This is so because global investing has the potential to reduce risk without sacrificing returns,

even with adverse short-run outcomes.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Answer PDFDocument17 pagesAnswer PDFميلاد نوروزي رهبرNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8: Risk and ReturnDocument56 pagesChapter 8: Risk and ReturnMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Multiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiDocument4 pagesMultiple Choice Questions Subject: Accountancy Class: XiShahid NaikNo ratings yet

- Always Trust The Customer How Zara Has Revolutionized The Fashion Industry and Become A Worldwide LeaderDocument27 pagesAlways Trust The Customer How Zara Has Revolutionized The Fashion Industry and Become A Worldwide LeaderbeatriceNo ratings yet

- Black-Litterman Portfolio Allocation Stability and Financial Performance With MGARCH-M Derived ViewsDocument65 pagesBlack-Litterman Portfolio Allocation Stability and Financial Performance With MGARCH-M Derived ViewsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Introduction & Research: Factor InvestingDocument44 pagesIntroduction & Research: Factor InvestingMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- TN1 Basic Pre-Calculus: AcronymsDocument11 pagesTN1 Basic Pre-Calculus: AcronymsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- TN 2 - Basic Calculus With Financial Applications: 1 Functions and LimitsDocument16 pagesTN 2 - Basic Calculus With Financial Applications: 1 Functions and LimitsMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Dark Side of Passive Investing: White PaperDocument11 pagesThe Dark Side of Passive Investing: White PaperMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Index Smart BetaDocument44 pagesIndex Smart BetaMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Giorgio S. Questa Induction To Quantitative Methods in FinanceDocument2 pagesGiorgio S. Questa Induction To Quantitative Methods in FinanceMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- From Smart Beta To Hard Reality: Executive SummaryDocument8 pagesFrom Smart Beta To Hard Reality: Executive SummaryMohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Transportation Methods PDFDocument24 pagesTransportation Methods PDFMohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Factor Model Notes:: R α β f β f …+β f ϵ R α β ' f ϵDocument2 pagesFactor Model Notes:: R α β f β f …+β f ϵ R α β ' f ϵMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Week 1 NotesDocument72 pagesWeek 1 NotesMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- PerformanceAnalytics PDFDocument214 pagesPerformanceAnalytics PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Probability Distribution and Statistics: Key Points of LearningDocument24 pagesProbability Distribution and Statistics: Key Points of LearningMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- The Efficient Market Theory and Evidence Implications For Active Investment Management PDFDocument93 pagesThe Efficient Market Theory and Evidence Implications For Active Investment Management PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- VX Python For Finance EuroScipy 2012 Y HilpischDocument47 pagesVX Python For Finance EuroScipy 2012 Y HilpischMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- 16 Mexico18 Dorantes PDFDocument43 pages16 Mexico18 Dorantes PDFMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Computational Finance and Financial Econometrics With RDocument527 pagesIntroduction To Computational Finance and Financial Econometrics With RMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Philip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Document117 pagesPhilip J. Romero - Tucker Balch - Hedge Fund Secrets - An Introduction To Quantitative Portfolio Management-Business Expert Press (2018)Mohamed Hussien100% (1)

- Ec371 Topic 3Document13 pagesEc371 Topic 3Mohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Correction For Exercise 7.2Document2 pagesCorrection For Exercise 7.2Mohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Chaos Theory and The Science of Fractals, and Their Application in Risk ManagementDocument78 pagesChaos Theory and The Science of Fractals, and Their Application in Risk ManagementMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Time Value of MoneyDocument48 pagesTime Value of MoneyMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- A Portfolio Selection and Capital Asset Pricing Model: Luigi Buzzacchi, Luca L. GhezziDocument15 pagesA Portfolio Selection and Capital Asset Pricing Model: Luigi Buzzacchi, Luca L. GhezziMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Financial Statement AnalysisDocument29 pagesFinancial Statement AnalysisMohamed HussienNo ratings yet

- Geogonia v. Court of Appeals DigestDocument6 pagesGeogonia v. Court of Appeals DigestJoy RaguindinNo ratings yet

- (3.) Interphil Laboratories Employees Union (Digest)Document2 pages(3.) Interphil Laboratories Employees Union (Digest)Dom Robinson BaggayanNo ratings yet

- SOA TemplateDocument1 pageSOA TemplateNoorasyaLya RozikinNo ratings yet

- Responsibility CentresDocument9 pagesResponsibility Centresparminder261090No ratings yet

- FLENDER D20-1 English HELICAL AND BEVEL GEARDocument25 pagesFLENDER D20-1 English HELICAL AND BEVEL GEARParcela Pinares NorteNo ratings yet

- CH 1 To 8Document4 pagesCH 1 To 8John WickNo ratings yet

- DEP 37.91.10.11-Gen Mobile Mooring Systems (Endorsement of API RP 2SK, API RP 2SM and API RP 2I)Document9 pagesDEP 37.91.10.11-Gen Mobile Mooring Systems (Endorsement of API RP 2SK, API RP 2SM and API RP 2I)Sd MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Quiz Techno Group1 ECEEEMEDocument2 pagesQuiz Techno Group1 ECEEEMEJohn Mark BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Bbsu Graduate Directory2 2016 1Document45 pagesBbsu Graduate Directory2 2016 1Ehsaan NooraliNo ratings yet

- 5 Characteristics-Defined ProjectDocument1 page5 Characteristics-Defined ProjectHarpreet SinghNo ratings yet

- 10-11-2016 - The Hindu - Shashi ThakurDocument26 pages10-11-2016 - The Hindu - Shashi ThakurSunilSainiNo ratings yet

- Khyber City Fee ScheduleDocument2 pagesKhyber City Fee ScheduleMohsin KhanNo ratings yet

- NetApp SnapMirrorDocument4 pagesNetApp SnapMirrorVijay1506No ratings yet

- It 41Document2 pagesIt 41रवींद्र वैद्यNo ratings yet

- Name Shehnila Azam Registration No# 45736 Course Cost and Management Accounting DAY Sunday Timing 3 To 6 Practice#1Document6 pagesName Shehnila Azam Registration No# 45736 Course Cost and Management Accounting DAY Sunday Timing 3 To 6 Practice#1yousuf AhmedNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 - Multivariable FunctionsDocument3 pagesTutorial 4 - Multivariable FunctionssurojiddinNo ratings yet

- Conjoint AnalysisDocument17 pagesConjoint Analysismark david sabellaNo ratings yet

- 2.0 Element of Conversion (Latest)Document5 pages2.0 Element of Conversion (Latest)b2utifulxxxNo ratings yet

- Franchise ProjectDocument3 pagesFranchise ProjectNicollete Limguangco SablaonNo ratings yet

- Kongunadu College of Engineering and Technology: Quantitative Aptitude PartnershipDocument16 pagesKongunadu College of Engineering and Technology: Quantitative Aptitude PartnershipGnana Prakasam RNo ratings yet

- Aca 2024 PlannerDocument1 pageAca 2024 Planneryfarhana2002No ratings yet

- Definition of IrrDocument3 pagesDefinition of IrrRajesh ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Account Statement From 1 Feb 2021 To 30 Apr 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument11 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Feb 2021 To 30 Apr 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceUday AbhiNo ratings yet

- Touc Hin G Li Ves, Imp Ro Ving Life - Proc Ter & GambleDocument30 pagesTouc Hin G Li Ves, Imp Ro Ving Life - Proc Ter & Gamblechandni kundel75% (12)

- PCB Quote 1003Document1 pagePCB Quote 1003rhedmishNo ratings yet

- DBLDocument3 pagesDBLLeafe MendozaNo ratings yet

- Audit Non Conformance ReportDocument4 pagesAudit Non Conformance Reportbudi_alamsyah100% (2)