Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Understanding The Factors Influencing Health-Worker Employment Decisions in South Africa

Understanding The Factors Influencing Health-Worker Employment Decisions in South Africa

Uploaded by

allan.manaloto23Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Understanding The Factors Influencing Health-Worker Employment Decisions in South Africa

Understanding The Factors Influencing Health-Worker Employment Decisions in South Africa

Uploaded by

allan.manaloto23Copyright:

Available Formats

George et al.

Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

RESEARCH

Open Access

Understanding the factors influencing

health-worker employment decisions in

South Africa

Gavin George1*, Jeff Gow1,2 and Shaneel Bachoo1

Abstract

Background: The provision of health care in South Africa has been compromised by the loss of trained health

workers (HWs) over the past 20 years. The public-sector workforce is overburdened. There is a large disparity in

service levels and workloads between the private and public sectors. There is little knowledge about the

nonfinancial factors that influence HWs choice of employer (public, private or nongovernmental organization)

or their choice of work location (urban, rural or overseas). This area is under-researched and this paper aims to fill

these gaps in the literature.

Method: The study utilized cross-sectional survey data gathered in 2009 in the province of KwaZulu-Natal. The HWs

sample came from three public hospitals (n = 430), two private hospitals (n = 131) and one nongovernmental organization

(NGO) hospital (n = 133) in urban areas, and consisted of professional nurses, staff nurses and nursing assistants.

Results: HWs in the public sector reported the poorest working conditions, as indicated by participants self-reports

on stress, workloads, levels of remuneration, standard of work premises, level of human resources and frequency of

in-service training. Interesting, however, HWs in the NGO sector expressed a greater desire than those in the public

and private sectors to leave their current employer.

Conclusions: To minimize attrition from the overburdened public-sector workforce and the negative effects of the

overall shortage of HWs, innovative efforts are required to address the causes of HWs dissatisfaction and to further identify

the nonfinancial factors that influence work choices of HWs. The results highlight the importance of considering a broad

range of nonfinancial incentives that encourage HWs to remain in the already overburdened public sector.

Keywords: Health workers, Human resources for health, Public sector, Private sector, Nongovernmental organization

sector, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa

Background

In the health-care field, addressing the health care needs

of a population is largely dependent on the provision of effective, efficient and high-quality health services, and the

health workforce provides arguably the most important

contribution to this process [1]. In 2008, there were approximately 250 000 health workers (HWs) employed in

South Africas health sector; relatively the same amount of

HWs as in 1997/98 [2]. When taking into account population growth and the burden of disease, the Development

* Correspondence: georgeg@ukzn.ac.za

1

Health Economics and HIV and AIDS Research Division, University of

KwaZulu-Natal, Private Bag X54001, Durban 4000, South Africa

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Bank of South Africa calculated a staff shortage of 80 000

HWs [3]. This critical shortage of HWs is being experienced at a time when the population is increasing and the

burden of ill-health, primarily due to HIV, AIDS and tuberculosis, is also on the rise [2]. The South African health

system comprises a strong private sector, serving less than

one-fifth of the population but employing 70% of medical

doctors and 54% of professional nurses [4-6]. Furthermore, there are large disparities between rural and urban

areas; rural parts of South Africa have 14 times fewer doctors than the national average [7].

The period since the mid 1990s has been one of workforce redundancy, vacancy freezes, shortages and cuts in

education and provision of training in the public sector

2013 George et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

[2]. During this time, health outcomes have worsened

and inequalities of access to HWs between the public

and private sectors, as well as between rural and urban

areas have not improved [2]. By way of illustration, the

Joint Venture Initiative, a nongovernmental organization

(NGO) that recruits doctors to work in under-served

rural areas in South Africa, calculated that one-half of

the 2400 medical graduates in 2006 and 2007 would leave

the country; of the remaining 1200 doctors, 75% would

work in the private sector, leaving 300 to work in the

public sector; of those 300, possibly 70 or 2.9% of medical

graduates each year would work in the public sector in a

rural area [8].

There are diverse nonfinancial factors that influence

HWs decisions to work in the private sector, urban

centre or to migrate abroad. They either push HWs

away or pull them towards the private sector, urban

area or destination country [4,8,9]. With a focus that

does not ignore remuneration, push factors are motivators that drive HWs away from the public sector.

Nonfinancial pull factors attract them to the private

sector, urban areas or overseas. While economic factors

play a significant role in the decisions of HWs as to

where they wish to work [5,10], evidence suggests that

remuneration is not the principle motivating factor

[11-15]. While most of these studies are from outside

South Africa, they all allude to the notion that there is

much more to motivation and retention than remuneration. Previous research found that the nonfinancial factors that push HWs from the public sector to the

private sector, urban area or destination country are:

resource-poor health systems, deteriorating work environments, inadequate medicine and equipment, poor human resource planning, political tension and upheaval,

gender discrimination, lack of personal security, HIV and

AIDS, poor housing, lack of transport and diminishing

social systems [16,17]. Of these, this study focuses on

resource-poor health systems and deteriorating work environments. In examining the working conditions and

perceptions of HWs, this study aims to promote an understanding of the nonfinancial motivating factors for

HW employment decisions in South Africa.

Nonfinancial motivating factors in HWs have received

a fair amount of empirical attention in recent times

[11-13]. A study in Cyprus compared the strength of

four work-related motivators for HWs: job attributes,

remuneration, co-workers and achievements [11]. They

found that achievements, which encompasses job meaningfulness, earned respect and interpersonal relationships, ranked the highest, followed by remuneration,

co-workers and job attributes. Other studies have demonstrated similar findings [12-14]. Intrinsic motivating

factors, such as job satisfaction, should therefore be

viewed as being just as important as extrinsic factors,

Page 2 of 7

such as remuneration, in an effort to retain staff and

keep them motivated. Meeting the needs of the employee is the cornerstone of job satisfaction and this is

of crucial importance for management, as it is strongly

correlated with improvements to the quality of service

that the organization provides [18].

The aim of this study is to examine and compare the

perceptions of HWs in the public, private and NGO sectors of their working conditions and their intentions to

stay or leave their existing position. In doing so, this will

identify the nonfinancial push and pull factors associated

with the trend away from public-sector employment and

will highlight areas on which policy-makers need to

focus attention given the efforts of government to retain

personnel within the public sector.

Methods

Study design, setting, population and sample size

The study utilized cross-sectional data collected in 2009

in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The sample of HWs

was selected purposively from three public hospitals,

two private hospitals and one NGO hospital in the province, and consisted of professional nurses, staff nurses

and nursing assistants.

Questionnaires were administered to HWs in urban

and peri-urban areas. The researchers used a proportional sampling method in sourcing participants from

each employment type (sector), meaning that the number of participants from a given sector was proportionate to the number of HWs working in that sector. The

largest number of HWs were selected from the public

sector (n = 430), followed by the NGO (n = 133) and

private (n = 131) sectors. A total of 694 HWs participated in the study.

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was based upon the Health

Worker Incentives Survey Immpact Toolkit [19]. Questions included: background (demographic) information,

cadre type, job and workplace perceptions, assessment

of job satisfaction as well as the desire to change their

current employer and or location.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package

for the Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., version 18.0, Chicago,

IL, USA). The primary unit of analysis in this study was

the type of health-care employer (public, private or

NGO). Bivariate analysis was used to compare responses

from participants in each of the employer types, with

both descriptive and inferential statistical methods used.

Chi-square tests were conducted to detect levels of significance in demographic and categorical variables (e.g.

sex, gender, level of education, employer type), while the

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

Page 3 of 7

one-way analysis of variance (F test) was carried out to

test for levels of significance in continuous (numerical)

variables, such as age. Participants rated various aspects

of their working environment on a 5-point Likert-type

rating scale (with 1 being low and 5 being high), and the

F test was used to test for differences in ratings between

participants from the three employer types.

Research ethics

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of

KwaZulu-Natal Humanities Research Ethics Committee

(Ethical Approval Number: HSS/0703/07). All participants

involved in the study were informed about the nature of

the study and what their participation would entail. Electronic and hard copies of the data are stored under lock

and key at the Health Economics and HIV and AIDS

Research Division office, and are only accessible by the

researchers involved in the study who are bound by confidentiality agreements.

Results and discussion

Demographics

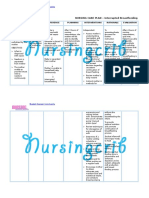

Table 1 shows that 90% (n = 620) of the total sample were

female this was consistent across employer types. No

significant difference in age was observed between the

three employer types, with the mean age being 36.96 years

(standard deviation [SD] = 10.38) (F = 1.650, P = 0.193).

The public sector (37%, n = 121) had significantly more

professional nurses than the private (23%, n = 27) and

NGO (24%, n = 22) sectors (2 = 14.764, P < 0.01). This is

consistent with the national profile [17]. Significantly more

personnel from the private sector (46%, n = 60) compared

with the public (31%, n = 131) and NGO (29%, n = 39) sectors indicated that they were married and living with their

Table 1 Participant demographics by employer type (sector)

Public

Private

NGO

Total

Sex

Male

13 (54)

4 (5)

8 (10)

10 (69)

Female

87 (374)

96 (125)

92 (121)

90 (620)

Cadre

Professional nurse

37 (121)

23 (27)

24 (22)

32 (170)

Staff nurse

33 (108)

48 (58)

39 (36)

38 (202)

Nursing assistant

30 (98)

29 (35)

37 (34)

31 (167)

Marital status

Married, living together

31 (131)

46 (60)

29 (39)

34 (230)

Married, living apart

4 (17)

4 (5)

3 (4)

4 (26)

Divorced

5 (20)

8 (11)

4 (5)

5 (36)

Widowed

6 (25)

3 (4)

7 (9)

6 (38)

Cohabiting, but not married

3 (13)

5 (7)

5 (7)

4 (27)

Single

51 (212)

34 (44)

52 (69)

48 (325)

Years of service

<1 year

12 (48)

63 (78)

22 (27)

1 to 2 years

17 (67)

4 (5)

11 (14)

13 (86)

2 to 3 years

8 (32)

7 (9)

10 (12)

8 (53)

3 to 4 years

7 (30)

4 (5)

2 (3)

6 (38)

4 to 5 years

5 (22)

<1 (1)

6 (7)

5 (30)

5 years or more

51 (207)

21 (26)

48 (60)

45 (293)

Private, renting

40 (164)

33 (43)

32 (40)

37 (247)

Private owned, but paying off loan

31 (129)

38 (49)

30 (38)

32 (216)

Private, owned & paid up

12 (49)

12 (15)

20 (25)

13 (89)

Private, family/friend provided

15 (60)

17 (22)

17 (22)

16 (104)

3 (11)

0 (0)

2 (2)

2 (13)

37.24 (10.61)

35.32 (8.59)

37.59 (11.08)

36.96 (10.38)

Employer provided

a

Data presented as percentage (number). Data presented as mean (standard deviation).

P = 0.116

2 = 14.764

P < 0.01*

2 = 21.960

P < 0.05*

2 = 152.490

P < 0.001**

2 = 13.845

P = 0.180

F = 1.650

P = 0.193

23 (153)

Accommodation

Agea (years)

Statistical test

2 = 15.451

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

spouse (2 = 21.960, P < 0.05). HWs in the public (51%,

n = 207) and NGO (48%, n = 60) sectors were more

likely than HWs in the private sector (21%, n = 26) to

have served their current employer for five years or

more (2 = 152.490, P < 0.001). The majority of the sample either resided in a private dwelling that was rented

(37%, n = 247), or in a privately owned dwelling (32%,

n = 216) that they were in the process of purchasing.

For 75% of the sample, HW income was either the

only income in the home or it made up at least 75%

of total household income.

Working conditions

Participants were asked to rate various aspects of the

conditions in which they work on a 5-point rating scale,

with 1 being low and 5 being high. When asked to compare the level of their workload with that of colleagues in

other sectors, workers in the public sector (mean = 4.55,

SD = 0.88) rated their workload significantly higher than

workers in the NGO (mean = 4.33, SD = 0.97) and private

(mean = 3.81, SD = 1.20) sectors (F = 23.869, P < 0.001).

Personnel from the public (mean = 4.16, SD = 1.03) and

NGO (mean = 4.14, SD = 0.92) sectors reported significantly more stress at work compared with workers in

the private sector (mean = 3.73, SD = 1.21) (F = 8.131,

P < 0.001). In general, workers who felt more stressed at

work were more likely to consider migrating (F = 5.251,

P < 0.01). Also, workers at public facilities (mean = 2.09,

SD = 1.25) rated the level of remuneration as significantly

lower than workers in the NGO (mean = 2.23, SD = 1.24)

Page 4 of 7

and private (mean = 2.61, SD = 1.06) sectors (F = 7.868,

P < 0.001). Moreover, personnel from the public sector

(mean = 2.27, SD = 1.19) rated the standard of their

working premises as much lower than workers from the

NGO (mean = 3.24, SD = 0.98) and private (mean = 3.89,

SD = 1.12) sectors (F = 106.806, P < 0.001). In addition,

public HWs (mean = 2.11, SD = 0.94) rated the adequacy

of available human resources available as significantly

lower than the NGO (mean = 2.32, SD = 1.02) and private

(mean = 3.04, SD = 1.00) sectors rated theirs (F = 43.474,

P < 0.001). Finally, public HWs (68%, n = 280) were significantly less likely to have received any in-service training since being employed when compared with workers

from the private (83%, n = 104) and NGO (87%, n = 115)

sectors (2 = 27.631, P < 0.001). A similar, but more acute

trend was observed when they were asked whether they received any such training in the past 12 months (Table 2).

HWs in the public sector especially experience

poorer working conditions, as indicated by participants self-reports on stress, workload, level of remuneration, standard of work premises, level of human

resources and frequency of in-service training. Our

findings are supported by others, confirming that several

salient push and pull factors play a role in HW plans and

decisions to migrate [17,20,21].

Intention to leave their current employment

HWs in the three sectors differed significantly as to

whether or not they were considering alternative employment (2 = 22.925, P < 0.001). HWs at NGOs (73%,

Table 2 Working conditions by employer type (sector)

Public

Private

NGO

Total

Statistical test

4.55 (0.88)

3.81 (1.20)

4.33 (0.97)

4.37 (1.00)

F = 23.869

Participants rating of:

Workload compared to colleagues in other sectors

Frequency of the feeling of stress at work

4.16 (1.03)

3.73 (1.21)

4.14 (0.92)

4.08 (1.06)

F = 8.131

P < 0.001**

Level of remuneration received for work

2.09 (1.25)

2.61 (1.06)

2.23 (1.24)

2.22 (1.23)

F = 7.868

P < 0.001**

Overall job satisfaction

3.62 (2.55)

3.05 (4.15)

3.53 (1.19)

3.50 (2.74)

F = 1.685

P = 0.186

Standard of the working premises

2.27 (1.19)

3.89 (1.12)

3.24 (0.98)

2.76 (1.31)

F = 106.806

P < 0.001**

Level of human resources

2.11 (0.94)

3.04 (1.00)

2.32 (0.96)

2.32 (1.02)

F = 43.474

P < 0.001**

Staff turnover rate

3.39 (1.25)

3.22 (1.10)

3.53 (1.32)

3.39 (1.24)

F = 1.789

P = 0.168

2 = 27.631

P < 0.001**

2 = 83.465

P < 0.001**

Received in-service training since employedb

Yes

68 (280)

83 (104)

87 (115)

74 (499)

No

31 (130)

16 (20)

12 (16)

25 (166)

Not sure

1 (4)

2 (2)

1 (1)

1 (7)

Received in-service training in the last 12 monthsb

P < 0.001**

Yes

40 (163)

73 (91)

76 (100)

53 (354)

No

58 (238)

23 (29)

22 (29)

44 (296)

Not sure

2 (9)

3 (4)

2 (2)

2 (15)

Mean scores based on a rating scale of 1 to 5 (low to high), presented as mean (standard deviation). bData presented as percentage (number).

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

n = 91) featured most prominently, followed by workers

in the public sector (59%, n = 230), while less than

one-half (47%, n = 56) of workers in the private sector

indicated that they were considering moving. Age significantly predicted the desire to leave, with those seeking alternative employment (mean = 35.23, SD = 8.94) being

significantly younger than those who were not (mean =

41.93, SD = 11.91) (F = 19.544, P < 0.001). Nursing cadre

(2 = 3.267, P = 0.514), sex (2 = 14.725, P = 0.142) and

marital status (2 = 18.138, P = 0.112) did not significantly predict their desire to leave/stay. Several factors

play a role in influencing the flow of HWs away from

the public sector. As is evident from the results, there

are various push factors associated with this sector, and

a number of pull factors associated with the private sector (Table 3).

Although few studies have explicitly set out to determine the variation of push and pull factors across age

groups, it is interesting to note that young HWs between

the ages of 20 and 29 were more likely to cite deteriorating working conditions as a reason for wanting to leave

South Africa, while older respondents (<60 years old)

were less likely to identify heavy workloads as a reason

for wanting to emigrate [22]. This is also the case in most

developing countries where public-sector health facilities

in general are characterized by poor infrastructure,

Page 5 of 7

management problems, unequal distribution of resources

and high numbers of people seeking treatment, accentuated by the high prevalence of HIV and AIDS in most populations on the continent, and in South Africa in particular

[17]. Elsewhere it has been argued that while countries in

east and southern Africa may not be in a position to provide financial incentives, there are alternatives that have

shown positive results in retaining HWs within their respective public health sectors [23]. Lesotho, Mozambique,

Malawi and Tanzania have provided housing to their HWs

whilst the provision of transport, childcare, food and employee support centres have all elicited positive HW retention outcomes [23].

Policy developments

Within South Africa, the need to address the problem of

both internal and external movement of HWs led to the

development and implementation of the Occupational

Specific Dispensation for HWs in the public sector to

improve their conditions of service and remuneration.

Since 2007 when the Occupational Specific Dispensation

strategy was developed, the translation of its objectives

into practice has evidently not been satisfactory. In 2011

the Department of Health estimated an annual attrition

rate of 25%, which excludes an additional 6% for retirement, death and change of profession [2]. This means

Table 3 Participant demographics by their intention to leave their current employment

Considering leaving?

Yes

No

Dont know

Total

Employer

Public

59 (230)

21 (81)

20 (76)

100 (387)

Private

47 (56)

36 (43)

18 (21)

100 (120)

NGO

73 (91)

16 (20)

11 (14)

100 (125)

Sex

Male

57 (34)

20 (12)

23 (14)

100 (60)

Female

60 (340)

23 (129)

17 (96)

100 (565)

Cadre

Professional Nurse

63 (98)

18 (28)

19 (30)

100 (156)

Staff nurse

59 (111)

22 (42)

19 (36)

100 (189)

Nursing assistant

57 (89)

26 (41)

17 (26)

100 (156)

Marital status

Married, living together

55 (118)

27 (58)

19 (40)

76 (19)

8 (2)

16 (4)

100 (25)

Divorced

58 (18)

32 (10)

10 (3)

100 (31)

Widowed

39 (12)

36 (11)

26 (8)

100 (31)

Cohabiting, but not married

62 (18)

12 (3)

19 (5)

100 (26)

Single

a

63 (184)

20 (59)

17 (49)

100 (292)

35.23 (8.94)

41.93 (11.91)

36.31 (10.76)

36.93 (10.36)

Data presented as percentage (number). Data presented as mean (standard deviation).

P < 0.001**

2 = 14.725

P = 0.142

2 = 3.267

P = 0.514

2 = 18.138

P = 0.112

F = 19.544

P < 0.001**

100 (216)

Married, living apart

Agea (years)

Statistical test

2 = 22.925

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

that every year 25% of the potential workforce (not just

new graduates) move from their current position, out of

the South African public health sector [2].

The South African Department of Health Strategy

2010/112012/13, in priority area five, called for the reopening of nursing schools and colleges along with the recruitment of HWs from countries with an excess of these

professionals [24]. The Strategy went further in placing

emphasis on examining the role of community HWs in the

public health-care system [24]. The Human Resources for

Health (HRH) Strategy for South Africa 20122016 further

emphasizes the need to strengthen and professionalize the

management of human resources and prioritize health

workforce needs [2]. To realize this goal, the government

set time horizons for the short (1 to 3 years), medium (3 to

5 years) and long (10 to 20 years) term, during which they

plan on achieving specific objectives [2]. In expressing part

of their strategic direction for the near to distant future,

government has committed itself to the scaling up and

revitalization of education, training and research, and to

strengthening and professionalizing the management of

human resources and prioritizing health workforce needs.

Based on the findings of this study, as well as other studies

[11-13], these goals, if realized, could go some way in curbing the flow of HWs away from the public sector and to

other countries. Based on these findings it will serve to attract others into the profession, and perhaps into the public sector. However, often documents propose effective

strategies to achieve goals only for it to be discovered later

that these goals were not realized due to the failure of authorities and stakeholders to effectively execute or implement these strategies.

To minimize HW attrition and the resultant negative

effects, innovative efforts are required to address the

causes of HWs dissatisfaction and to further identify the

nonfinancial factors that influence HWs choices, especially given the inability to increase remuneration within

a constrained fiscus. The South African Strategic Plan

for HIV, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections

2012 to 2016 does call for the need to explore innovative financing as a mechanism for raising additional resources for the public health care system [25]. Fryatt

suggests a number of avenues that South Africa could

explore to raise funds and whilst these resources will not

solely be allocated to HRH, they could be used to fund

efficacious attraction and retention strategies [25]. The

government of Malawi responded to their HW crisis by

increasing salaries by 50%, improving working conditions, re-enrolment of retired HWs and investment in

training for HRH, all of which yielded positive results

[26]. Ghana, for their innovative education and training

strategies, were recognized with an award from the Health

Worker Migration Policy Council [26]. Limited resources,

inadequate education and career opportunities along with

Page 6 of 7

weak management systems leads to a shortage of HWs

[26]. Further research is needed in those countries that

have successfully addressed these issues. South Africa,

through policy, has set out ways to address the HRH shortage, but implementation is key to ensure there are adequate staffing levels across cadres and in traditionally

under-resourced areas.

Limitations of study

The study is limited by its use of a cross-sectional design

that entailed the gathering of data at only one point in

time from nurses in selected health facilities in one

province of South Africa. The use of proportional sampling does not allow us to generalize these findings to

other types of health professionals. Other categories of

health professionals, such as pharmacists, physiotherapists, dentists, occupational therapists and psychologists,

who are crucial to the delivery of health-care services,

were not included. The generalization of these findings

to other nurses across the public, private and NGO sectors is further limited by the fact that the nurses participating in this study do not necessary represent nurses

across the country working in these sectors.

Conclusions

The results of this study highlight the importance of

implementing a broad range of nonfinancial incentives

that are attractive to HWs and encourage them to remain

as HWs and importantly to stay in the public sector.

While the study identifies several factors that motivate

HWs to move out of health, there is a paucity of evidence

on the efficacy of various incentive schemes that address

the nonfinancial pull and push factors to move within or

out of health. Further examination and analysis are

needed to better understand the contributing factors to

HW motivation and retention, and to better understand

the varying degrees to which different incentives influence HW motivation and job satisfaction. This information is critical for effective workforce planning and policy

development in the public health sector.

Incentive packages to attract, retain and motivate HWs

should be embedded in comprehensive workforce planning

and development strategies in South Africa. The research

findings from three public hospitals, two private hospitals

and one NGO hospital indicate that improved work premises and career advancement and training opportunities are

important. Strategies require examination of the underlying

factors for HW shortages, analysis of the determinants of

HW motivation and retention, and testing of innovative

initiatives for maintaining a well-staffed, competent and

motivated health workforce, especially in the public sector.

Continued research and evaluation will strengthen the

knowledge base and assist the development of effective incentive packages for public HWs.

George et al. Human Resources for Health 2013, 11:15

http://www.human-resources-health.com/content/11/1/15

Abbreviations

HRH: Human Resources for Health; HW: health worker;

NGO: nongovernmental organization.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors contributions

GG conceived the study and manuscript, lead the acquisition of data and

interpretation of data, and was involved in drafting the manuscript. JG

designed the study and contributed to the interpretation of the results and

revising the manuscript. SB conducted analysis and was involved in drafting

the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Page 7 of 7

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Author details

1

Health Economics and HIV and AIDS Research Division, University of

KwaZulu-Natal, Private Bag X54001, Durban 4000, South Africa. 2School of

Accounting, Economics and Finance, University of Southern Queensland,

Toowoomba, QLD 4350, Australia.

Received: 29 March 2012 Accepted: 3 April 2013

Published: 23 April 2013

References

1. Rigoli F, Dussault G: The interface between health sector reform and

human resources in health. Hum Resour Health 2003, 1:9.

2. Department of Health: Human Resources for Health South Africa: HRH

Strategy for the Health Sector: 2012/132016/17. Pretoria: National

Department of Health; 2011.

3. Development Bank of South Africa Roadmap Process. http://www.dbsa.org/

Research/Documents/Health%20Roadmap.pdf.

4. Lehmann U: Strengthening human resources for primary health care. S

Afr Health Rev 2008, 9:781786.

5. Day C, Gray A: Health and related indicators. S Afr Health Rev 2008, 2:382388.

6. Chabikuli N, Blaauw D, Gilson L, Schneider H: Human resource policies. S

Afr Health Rev 2005, 3:104115.

7. Mills EJ, Schabas WA, Volmink J, Walker R, Ford N, Katabira E, Anema A,

Joffres M, Cahn P, Montaner P: Should active recruitment of health

workers from sub-Saharan Africa be viewed as a crime? Lancet 2008,

371:685688.

8. Bateman C: Slim pickings as 2008 health staff crisis looms. S Afr Med J

2007, 97:10201034.

9. Clemens M, Pettersson G: New data on African health professionals

abroad. Hum Resour Health 2008, 6:111.

10. George G, Quinlan T, Reardon C: Human resources for health: a needs and

gaps analysis of Human Resources for Health in South Africa. Durban: Health

Economics and HIV & AIDS Research Division; 2009.

11. Lambrou P, Kontodimopoulos N, Niakas D: Motivation and job satisfaction

among medical and nursing staff in Cyprus public general hospital. Hum

Resour Health 2010, 8:26.

12. Kontodimopoulos N, Paleologou V, Niakas D: Identifying important

motivational factors for professionals in Greek hospitals. BMC Health Serv

Res 2009, 9:164.

13. Franco LM, Bennett S, Kanfer R, Stubblebine P: Determinants and

consequences of health worker motivation in hospitals in Jordan and

Georgia. Soc Sci Med 2004, 58:343355.

14. Mathauer I, Imhoff I: Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of

nonfinancial incentives and human resource management tools.

Hum Resour Health 2006, 4:24.

15. Manongi RN, Marchant TC, Bygbjerg IC: Improving motivation among

primary health care workers in Tanzania: a health worker perspective.

Hum Resour Health 2006, 4:6.

16. Pagett C, Padarath A: A review of codes and protocols for the migration of

health workers (EQUINET Discussion Paper 50). Harare, Zimbabwe: Regional

Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa; 2007.

17. Hamilton K, Yau J: The global tug-of-war for health care workers. Washington,

DC: Migration Policy Institute; 2010.

18. Ovretveit J: Leading improvement. J Health Organ Mgmt 2005, 19:413430.

19. Toolkit I: A guide and tools for maternal mortality programme assessment.

MODULE 4, Tool 5: Health Worker Incentives Survey (HWIS). University of

26.

Aberdeen, Health Sciences Building, Foresterhill, Aberdeen, AB25 2ZD,

Scotland, United Kingdom; 2007.

Packer C, Labonte R, Spitzer D: Globalisation and the health worker crisis.

Geneva: WHO Commission on Social Determinants on Health; 2007.

Oberoi S, Lin V: Brain drain of doctors from southern Africa: brain gain

for Australia. Aust Health Rev 2006, 30:2533.

Maslin A: Databank of bilateral agreements. Washington, US: The Aspen

Institute-Global Health and Development; 2003.

Dambisya Y: A review of non-financial incentives for health worker retention in

east and southern Africa (Equinet Discussion Paper No. 44). Harare, Zimbabwe:

Regional Network for Equity in Health in East and Southern Africa; 2007.

www.equinetafrica.org/bibl/docs/DIS44HRdambisya.pdf.

Department of Health: National Department of Health Strategic Plan 2010/

112012/13. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2010.

Fryatt B: Innovative financing for health: what are the options for South Africa?.

Cape Town, South Africa: Public Health Association of South Africa; 2012.

http://www.phasa.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/Innovativefinancing_Bob-Fryatt.pdf.

Sheikh M: Health workers and MDGs: inextricably linked. Commonwealth

Ministers Reference Book. London: Commonwealth Secretariat; 2012:231234.

doi:10.1186/1478-4491-11-15

Cite this article as: George et al.: Understanding the factors influencing

health-worker employment decisions in South Africa. Human Resources

for Health 2013 11:15.

Submit your next manuscript to BioMed Central

and take full advantage of:

Convenient online submission

Thorough peer review

No space constraints or color gure charges

Immediate publication on acceptance

Inclusion in PubMed, CAS, Scopus and Google Scholar

Research which is freely available for redistribution

Submit your manuscript at

www.biomedcentral.com/submit

You might also like

- Script For Health Talk ShowDocument2 pagesScript For Health Talk ShowJana Jean Ogoc100% (6)

- Understanding Healthcare Access in IndiaDocument46 pagesUnderstanding Healthcare Access in IndiaNaveen KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Sample Curriculum Review Form PDFDocument3 pagesSample Curriculum Review Form PDFallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Subiecte Olimpiadă Limba Engleză Clasa A 9aDocument3 pagesSubiecte Olimpiadă Limba Engleză Clasa A 9akallai annamaria100% (1)

- Ayoub Jumanne Proposal MzumbeDocument36 pagesAyoub Jumanne Proposal MzumbeGoodluck Savutu Lucumay50% (2)

- Omnibus CAV of DocumentsDocument1 pageOmnibus CAV of Documentsallan.manaloto23100% (1)

- Windshield SurveyDocument8 pagesWindshield Surveyapi-251012259No ratings yet

- Nursing Care Plan For Interrupted Breastfeeding NCPDocument3 pagesNursing Care Plan For Interrupted Breastfeeding NCPderic88% (8)

- Nursing Documentation Final Course Exam IDocument5 pagesNursing Documentation Final Course Exam Iapi-329063194No ratings yet

- Ashraf Et Al 2020 (AER)Document40 pagesAshraf Et Al 2020 (AER)Jose CamposNo ratings yet

- Kinerja PerawatDocument12 pagesKinerja PerawatMarvy MarthaNo ratings yet

- PHD Thesis Proposal - Introduction To Information Sheet For Submission To RPODocument115 pagesPHD Thesis Proposal - Introduction To Information Sheet For Submission To RPOmezgebuy100% (1)

- Determinants of Motivation Among Healthcare SLRDocument24 pagesDeterminants of Motivation Among Healthcare SLRyazanNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Interventions To Attract and Retain Health Workers in Rural Zambia - A Discrete Choice ExperimentDocument12 pagesAssessment of Interventions To Attract and Retain Health Workers in Rural Zambia - A Discrete Choice ExperimentJace AlacapaNo ratings yet

- Body PartDocument34 pagesBody Parttolinaabate74No ratings yet

- Sources of Community Health Worker Motivation: A Qualitative Study in Morogoro Region, TanzaniaDocument12 pagesSources of Community Health Worker Motivation: A Qualitative Study in Morogoro Region, TanzaniaNurul pattyNo ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction Work Stress and Turnover IntentioDocument11 pagesJob Satisfaction Work Stress and Turnover IntentioPeter GirasolNo ratings yet

- Private Health Providers AfricaDocument6 pagesPrivate Health Providers AfricaSara FerreiraNo ratings yet

- 1 Assessing Human Resources For Health, What Can Be Learned From Labour Force SurveysDocument16 pages1 Assessing Human Resources For Health, What Can Be Learned From Labour Force Surveyssumadi hartonoNo ratings yet

- Differences in Health Care Seeking Behaviour Between Rural and Urban Communities in South AfricaDocument9 pagesDifferences in Health Care Seeking Behaviour Between Rural and Urban Communities in South AfricafrendirachmadNo ratings yet

- Private-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesDocument18 pagesPrivate-Sector Provision of Health Care in The Asia-Pacific Region: A Background Briefing On Current Issues and Policy ResponsesNossal Institute for Global HealthNo ratings yet

- An Examination of The Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses To The Migration of Highly Trained Health Personnel From The Philippines The High Cost of Living or Leaving-A Mixed Method StudyDocument15 pagesAn Examination of The Causes, Consequences, and Policy Responses To The Migration of Highly Trained Health Personnel From The Philippines The High Cost of Living or Leaving-A Mixed Method StudyPaul Mark PilarNo ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- A Survey Report On Scaling of Public Health Units As Sub Centers, PHC and CHC of Uttar Pradesh State, India.Document71 pagesA Survey Report On Scaling of Public Health Units As Sub Centers, PHC and CHC of Uttar Pradesh State, India.Voice of People100% (1)

- International Journal For Equity in HealthDocument12 pagesInternational Journal For Equity in HealthjlventiganNo ratings yet

- Zhu 2014Document9 pagesZhu 2014Mounir ChadliNo ratings yet

- Accessibility of Primary Health Care Services: A Case Study of Kadakola Primary Health Centre in Mysore DistrictDocument12 pagesAccessibility of Primary Health Care Services: A Case Study of Kadakola Primary Health Centre in Mysore DistrictTharangini MNo ratings yet

- Junal Inter 4Document10 pagesJunal Inter 4adi qiromNo ratings yet

- Health Worker Motivation in Africa: The Role of Non-Financial Incentives and Human Resource Management ToolsDocument36 pagesHealth Worker Motivation in Africa: The Role of Non-Financial Incentives and Human Resource Management ToolsBM2062119PDPP Pang Kuok WeiNo ratings yet

- Identification of Real World ServicesDocument5 pagesIdentification of Real World ServicesBryan RuttoNo ratings yet

- Presentation Health Resumen TextoDocument5 pagesPresentation Health Resumen Textobertin osborneNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and Stress Among Healthcare Workers in Public Hospitals in QatarDocument9 pagesJob Satisfaction and Stress Among Healthcare Workers in Public Hospitals in Qatarmlee5638valNo ratings yet

- Use of Family Planning and Child Health Services in The Private Sector: An Equity Analysis of 12 DHS SurveysDocument12 pagesUse of Family Planning and Child Health Services in The Private Sector: An Equity Analysis of 12 DHS SurveysUpik SupuNo ratings yet

- Factors Motivating Participation of Persons With Disability in The PhilippinesDocument23 pagesFactors Motivating Participation of Persons With Disability in The PhilippinesVERA FilesNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Funding Public HealthDocument5 pagesDissertation Funding Public HealthWriteMyPaperCanadaUK100% (1)

- Litrature Review of Rural Healthcare Management in IndiaDocument42 pagesLitrature Review of Rural Healthcare Management in Indiasri_cbm67% (6)

- 9-Determinants of Health Expenditures- A Case of High Populated Asian CountriesDocument13 pages9-Determinants of Health Expenditures- A Case of High Populated Asian CountriesMuhammad Iftikhar AliNo ratings yet

- Health Insurance in IndiaDocument93 pagesHealth Insurance in IndiaSaurabh NagwekarNo ratings yet

- Urban Health and Health Seeking Behaviour - A Case Study of Slums in India and PhilippinesDocument193 pagesUrban Health and Health Seeking Behaviour - A Case Study of Slums in India and Philippineskarl_poorNo ratings yet

- CHALLENGES OF CHNs & Health Care DeliveryDocument6 pagesCHALLENGES OF CHNs & Health Care DeliveryAnitha KarthikNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Human Resources Management in Health Care: A Global ContextDocument24 pagesThe Importance of Human Resources Management in Health Care: A Global ContextShafaque GideonNo ratings yet

- Career Op Global HealthDocument4 pagesCareer Op Global HealthYano AmimoNo ratings yet

- Beyond The Four Walls ReportDocument85 pagesBeyond The Four Walls ReportMaine Trust For Local NewsNo ratings yet

- Awareness of National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) Activities Among Employees of A Nigerian UniversityDocument9 pagesAwareness of National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS) Activities Among Employees of A Nigerian UniversitySiva KalimuthuNo ratings yet

- DPR-Mar-17-1970.R1 - Deane KD Update TT AcceptedDocument21 pagesDPR-Mar-17-1970.R1 - Deane KD Update TT AcceptedpapanombaNo ratings yet

- DSFDFSDGDFSGDocument9 pagesDSFDFSDGDFSGadasdaNo ratings yet

- Human Resources For HealthDocument10 pagesHuman Resources For HealthzpazpaNo ratings yet

- National Health PolicyDocument8 pagesNational Health PolicyTanmoy JanaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Healthcare ManagementDocument7 pagesThesis Healthcare Managementlesliedanielstallahassee100% (2)

- Social Factors Influencing Individual and Population Health - EditedDocument6 pagesSocial Factors Influencing Individual and Population Health - EditedOkoth OluochNo ratings yet

- International Journal For Equity in HealthDocument12 pagesInternational Journal For Equity in HealthReiner Lorenzo TamayoNo ratings yet

- تقرير طب مجتمعDocument7 pagesتقرير طب مجتمعSaif HashimNo ratings yet

- 122-Article Text-453-1-10-20200622Document12 pages122-Article Text-453-1-10-20200622Real TetisoraNo ratings yet

- Analysis Demand Need: of andDocument12 pagesAnalysis Demand Need: of andnimi111No ratings yet

- Public Health Dissertation TitlesDocument7 pagesPublic Health Dissertation TitlesWriteMyPaperPleaseSingapore100% (1)

- Literature Review On Community Participation in Hiv Aids Prevention ResearchDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Community Participation in Hiv Aids Prevention ResearchaflsbbesqNo ratings yet

- Effects of User Fee Exemptions On The Provision and Use of Maternal Health Services: A Review of LiteratureDocument15 pagesEffects of User Fee Exemptions On The Provision and Use of Maternal Health Services: A Review of LiteratureYet Barreda BasbasNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Nurses and Midwives of DohDocument12 pagesJob Satisfaction and Turnover Intention Among Nurses and Midwives of Dohkaori mendozaNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two To Five EditedDocument23 pagesChapter Two To Five EditedAbdullahi AwwalNo ratings yet

- The Impacts of Health and Education Components of Human Resources Development On Poverty Level in Nigeria, 1980-2013.Document6 pagesThe Impacts of Health and Education Components of Human Resources Development On Poverty Level in Nigeria, 1980-2013.IOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- Julia 2016Document10 pagesJulia 2016JENNIFER RIOFRIO ASEICHANo ratings yet

- In Dessie Town, Ethiopia: Willingness To Join A Village-Based Health Insurance Scheme (Iddir)Document8 pagesIn Dessie Town, Ethiopia: Willingness To Join A Village-Based Health Insurance Scheme (Iddir)mohammed abdellaNo ratings yet

- Uhc Via PHCDocument19 pagesUhc Via PHCTeslim RajiNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction and Morale inDocument13 pagesJob Satisfaction and Morale inMoeshfieq WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Disability and Employer Practices: Research across the DisciplinesFrom EverandDisability and Employer Practices: Research across the DisciplinesNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1-07 Measures of Variation STATDocument12 pagesLesson 1-07 Measures of Variation STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 1-02 Data Collection and Analysis STATDocument12 pagesLesson 1-02 Data Collection and Analysis STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 2-01 Probability STATDocument13 pagesLesson 2-01 Probability STATallan.manaloto23100% (1)

- Lesson 2-03 Random Variables STATDocument10 pagesLesson 2-03 Random Variables STATallan.manaloto23100% (3)

- Lesson 1-04 Types of Data STATDocument19 pagesLesson 1-04 Types of Data STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 1-01 Variation in Data STATDocument16 pagesLesson 1-01 Variation in Data STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 2-02 Geometric Probability STATDocument14 pagesLesson 2-02 Geometric Probability STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 1-05 Measuring Central Tendency STATDocument12 pagesLesson 1-05 Measuring Central Tendency STATallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Lesson 1-03 The Body Mass IndexDocument7 pagesLesson 1-03 The Body Mass IndexcjNo ratings yet

- 3.5 PrytherchDocument15 pages3.5 Prytherchallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Manual For Curriculum Revisions and Development: Mindanao State University (System)Document95 pagesManual For Curriculum Revisions and Development: Mindanao State University (System)allan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Health Workforce Remuneration: Comparing Wage Levels, Ranking, and Dispersion of 16 Occupational Groups in 20 CountriesDocument15 pagesHealth Workforce Remuneration: Comparing Wage Levels, Ranking, and Dispersion of 16 Occupational Groups in 20 Countriesallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- 3.6 MenyaDocument8 pages3.6 Menyaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Acceptance of Teacher I Applicants For School Year 2017 2018 For Public Elementary and Junior or Senior High SchoolsDocument7 pagesAcceptance of Teacher I Applicants For School Year 2017 2018 For Public Elementary and Junior or Senior High Schoolsallan.manaloto2375% (4)

- Application For Permission To Teach Outside of Official Time PDFDocument1 pageApplication For Permission To Teach Outside of Official Time PDFallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Developing A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan AfricaDocument11 pagesDeveloping A Tool To Measure Satisfaction Among Health Professionals in Sub-Saharan Africaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- 7 ParametersDocument1 page7 Parametersallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- 2.3 HontelezDocument12 pages2.3 Hontelezallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- 2.1 GarciaDocument11 pages2.1 Garciaallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Brain Teasers 1Document3 pagesBrain Teasers 1allan.manaloto230% (1)

- Human Resource Issues: Implications For Health Sector ReformsDocument39 pagesHuman Resource Issues: Implications For Health Sector Reformsallan.manaloto23No ratings yet

- Contemporary Orthodontics, 5th Ed: Book ReviewDocument1 pageContemporary Orthodontics, 5th Ed: Book ReviewPaula Diaz100% (1)

- Amoebiasis DiseaseDocument10 pagesAmoebiasis Diseaseshruti ghordadeNo ratings yet

- TRIAGEDocument55 pagesTRIAGELaveena AswaleNo ratings yet

- Clinical Goals For Placement Louisa Oduro Animapauh Hsns 206 220183967Document3 pagesClinical Goals For Placement Louisa Oduro Animapauh Hsns 206 220183967api-426629371No ratings yet

- Biopsychosocial and Interventions PaperDocument13 pagesBiopsychosocial and Interventions Paperapi-272668024No ratings yet

- Controlling The Risks From Vibration at WorkDocument7 pagesControlling The Risks From Vibration at WorkASWINKUMAR GOPALAKRISHNANNo ratings yet

- Xceed 1 Slide Per PageDocument31 pagesXceed 1 Slide Per Pagemccarthy121677100% (1)

- Atrioventricular Spetal Defect Avsd Partial EditDocument2 pagesAtrioventricular Spetal Defect Avsd Partial EditFelicia Shan SugataNo ratings yet

- DLP UndpDocument2 pagesDLP UndpAzzy DalipeNo ratings yet

- RadiologijaDocument42 pagesRadiologijaAzra Bajrektarevic0% (1)

- Public Perception of Mental Health in Iraq: Research Open AccessDocument11 pagesPublic Perception of Mental Health in Iraq: Research Open AccessSri HariNo ratings yet

- Etiological Factors of Ocular Trauma in Children and Adolescents Based On 200 Cases at The Pediatric Ophthalmology Unit of The Bouake University HospitalDocument7 pagesEtiological Factors of Ocular Trauma in Children and Adolescents Based On 200 Cases at The Pediatric Ophthalmology Unit of The Bouake University HospitalAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Intergrated Science G 1 7Document67 pagesIntergrated Science G 1 7david simwingaNo ratings yet

- Kerala Floods - 2018: A Report by Archbishop Andrews ThazhathDocument31 pagesKerala Floods - 2018: A Report by Archbishop Andrews Thazhathsunil unnithanNo ratings yet

- February 19, 2014Document12 pagesFebruary 19, 2014Maple Lake MessengerNo ratings yet

- Analytical Exposition Text: By: Ariful SukronDocument8 pagesAnalytical Exposition Text: By: Ariful SukronAriful SukronNo ratings yet

- Job Stress Work Performance With CommentssssDocument37 pagesJob Stress Work Performance With CommentssssAmen MartzNo ratings yet

- Drug Addiction by Slidesgo 2Document9 pagesDrug Addiction by Slidesgo 2mazanshafi123No ratings yet

- Transition Between Community or Care Home and Inpatient Mental Health Settings Discharge From Inpatient Mental Health Services To Community or Care Home SupportDocument13 pagesTransition Between Community or Care Home and Inpatient Mental Health Settings Discharge From Inpatient Mental Health Services To Community or Care Home SupportAmit TamboliNo ratings yet

- MBT and TraumaDocument19 pagesMBT and Traumassanagav0% (1)

- Para LabDocument22 pagesPara LabClaudine DelacruzNo ratings yet

- Acute Management of Pulmonary Embolism - American College of CardiologyDocument22 pagesAcute Management of Pulmonary Embolism - American College of CardiologyRaja GopalNo ratings yet

- Hospital SellingDocument5 pagesHospital SellingMohamed BahnasyNo ratings yet

- Esophageal VaricesDocument3 pagesEsophageal VaricesSasa LuarNo ratings yet

- Sairui E-Commerce Product CatalogueDocument23 pagesSairui E-Commerce Product CatalogueCanaan GamelifeNo ratings yet