Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Vegetation of Socotra

The Vegetation of Socotra

Uploaded by

marwan98Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- James Gurney - Dinotopia - A Land Apart From Time (SiPDF)Document168 pagesJames Gurney - Dinotopia - A Land Apart From Time (SiPDF)Sergio Mercado Gil98% (54)

- Ingleton Field ReportDocument5 pagesIngleton Field Reportjosh0704No ratings yet

- Bpharm Myleads 2023 09 12 (All)Document202 pagesBpharm Myleads 2023 09 12 (All)nitingudduNo ratings yet

- Geology of Labuan - 1852Document13 pagesGeology of Labuan - 1852Martin LavertyNo ratings yet

- Explanatory Notes On The Perth Geological SheetDocument40 pagesExplanatory Notes On The Perth Geological Sheetscrane@No ratings yet

- Metodichka Part 1 Final Version 1Document49 pagesMetodichka Part 1 Final Version 1Alyona ChernyaevaNo ratings yet

- Stratigraphic ReportDocument3 pagesStratigraphic Reportapi-309272596No ratings yet

- Extract Prehistoric Cultures of The Horn of Africa - ClarkDocument29 pagesExtract Prehistoric Cultures of The Horn of Africa - Clarklolololoolololol999No ratings yet

- Epicor Data DiscoveryDocument3 pagesEpicor Data Discoverygary kraynakNo ratings yet

- Cruise of the Revenue-Steamer Corwin in Alaska and the N.W. Arctic Ocean in 1881: Botanical Notes: Notes and Memoranda: Medical and Anthropological; Botanical; OrnithologicalFrom EverandCruise of the Revenue-Steamer Corwin in Alaska and the N.W. Arctic Ocean in 1881: Botanical Notes: Notes and Memoranda: Medical and Anthropological; Botanical; OrnithologicalNo ratings yet

- Kissling-CharacterPurposeHebridean-1943 (1) - CompressedDocument30 pagesKissling-CharacterPurposeHebridean-1943 (1) - Compressedahmet.uzunNo ratings yet

- FIG (1) Location and Boundaries of PalestineDocument11 pagesFIG (1) Location and Boundaries of PalestineMohammed Mustafa ShaatNo ratings yet

- Southern Nigeria1907Document10 pagesSouthern Nigeria19074zhhmwqb75No ratings yet

- Tidalflat LandformDocument6 pagesTidalflat LandformMaung Maung ThanNo ratings yet

- Geological Field Report of Salt Range and Hazara Range PakistanDocument69 pagesGeological Field Report of Salt Range and Hazara Range PakistanEw HoneyNo ratings yet

- Tsingtao Black BookDocument38 pagesTsingtao Black BookDinko OdakNo ratings yet

- AVNER, Ancient Water Management in The Southern Negev, ARAM 14 (2002)Document19 pagesAVNER, Ancient Water Management in The Southern Negev, ARAM 14 (2002)omnisanctus_newNo ratings yet

- John Haldon - Palgrave Atlas of Byzantine History 1-13 OCRDocument7 pagesJohn Haldon - Palgrave Atlas of Byzantine History 1-13 OCRAnathema Mask100% (1)

- An Introduction To The Study of The Babylonians and AssyriansDocument88 pagesAn Introduction To The Study of The Babylonians and AssyriansAisel OmarovaNo ratings yet

- Hydrogeochemical Assessment of Groundwater in Gal-Mudug Region - SomaliaDocument17 pagesHydrogeochemical Assessment of Groundwater in Gal-Mudug Region - SomaliaSalsabiil water well drillingNo ratings yet

- Sweeting, Marjorie M. The Karstlands of JamaicaDocument18 pagesSweeting, Marjorie M. The Karstlands of JamaicaCae MartinsNo ratings yet

- Sedimentary Facies Distribution PDFDocument18 pagesSedimentary Facies Distribution PDFgeologuitaristNo ratings yet

- Crofting Settlements and Housing in The Outer HebridesDocument14 pagesCrofting Settlements and Housing in The Outer Hebridesahmet.uzunNo ratings yet

- The American Southeast, A Guide To Florida and Adjacent Shores - A Golden Regional Guide (1959)Document168 pagesThe American Southeast, A Guide To Florida and Adjacent Shores - A Golden Regional Guide (1959)Kenneth100% (3)

- Arabia in The Pre-Islamic Period PDFDocument26 pagesArabia in The Pre-Islamic Period PDFRıdvan ÇeliközNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 Abbottabad DistrictDocument18 pagesCHAPTER 1 Abbottabad DistrictTaimur Hyat-KhanNo ratings yet

- Case Study of A Drainage BasinDocument8 pagesCase Study of A Drainage BasinGrace KamauNo ratings yet

- 2 WeatheringDocument31 pages2 WeatheringEfraim HermanNo ratings yet

- History of Waterlooville, John RegerDocument56 pagesHistory of Waterlooville, John RegerAnonymous UgVOzaNo ratings yet

- Dos Latossolos Aos Espodossolos Evolucao Rio Negro 1998Document36 pagesDos Latossolos Aos Espodossolos Evolucao Rio Negro 1998manoelribeiroNo ratings yet

- Terrestrial Morphologics Tidal Flat Sublittoral ZoneDocument6 pagesTerrestrial Morphologics Tidal Flat Sublittoral ZonerandikaNo ratings yet

- Geology of EgyptDocument47 pagesGeology of EgyptMohamed Ibrahim ShihataaNo ratings yet

- SWEcuador MIOCNEDocument3 pagesSWEcuador MIOCNEPatricia Del Carmen Guevara VasquezNo ratings yet

- Criminal Statistics and Movement of the Bond Population of Norfolk IslandFrom EverandCriminal Statistics and Movement of the Bond Population of Norfolk IslandNo ratings yet

- C 483244-l 3-k SpennDocument39 pagesC 483244-l 3-k SpennAngelo-Daniel SeraphNo ratings yet

- Solifluction Gold Placers of MongoliaDocument8 pagesSolifluction Gold Placers of MongoliaSarah Wulan SariNo ratings yet

- The Peoples of the Great North. Art and Civilisation of SiberiaFrom EverandThe Peoples of the Great North. Art and Civilisation of SiberiaNo ratings yet

- Groundwater Quality: Ethiopia: BackgroundDocument6 pagesGroundwater Quality: Ethiopia: BackgroundTewfic SeidNo ratings yet

- Show Older Posts Show Older Posts On The Tracks of Ancient MammalsDocument41 pagesShow Older Posts Show Older Posts On The Tracks of Ancient MammalssatishgeoNo ratings yet

- Special Study of The Enemy Situation Iwo Jima USA 1944Document29 pagesSpecial Study of The Enemy Situation Iwo Jima USA 1944skaw999100% (1)

- Geochronology of Plistocene EpochDocument6 pagesGeochronology of Plistocene EpochRUHUL AMIN LASKARNo ratings yet

- Troia Peninsula Evolution The Dune Morphology RecoDocument5 pagesTroia Peninsula Evolution The Dune Morphology RecofilipaNo ratings yet

- Heron IslandDocument15 pagesHeron IslandMuhammad Faishal Imam AfifNo ratings yet

- Oceans and OceanographyDocument13 pagesOceans and OceanographymkprabhuNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899Document6 pagesThe Cambridge Anthropological Expedition To Torres Straits and S 1899MUPyP comunidadNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Archaeological Sites Near Guaymas, SonoraDocument24 pagesA Survey of Archaeological Sites Near Guaymas, SonoraAlberto Duran IniestraNo ratings yet

- Vegetation Ecology of Fiji: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives!Document17 pagesVegetation Ecology of Fiji: Past, Present, and Future Perspectives!Ahmed GaribNo ratings yet

- Notes on the Fenland; with A Description of the Shippea ManFrom EverandNotes on the Fenland; with A Description of the Shippea ManNo ratings yet

- Geomorphology of The Eastern Badia Basalt Plateau, JordanDocument19 pagesGeomorphology of The Eastern Badia Basalt Plateau, Jordanhind.ghanemNo ratings yet

- Geographical Survey NotesDocument19 pagesGeographical Survey Noteswilliegeraghty71No ratings yet

- Barit2 PDFDocument14 pagesBarit2 PDFResa Rifal PraditiaNo ratings yet

- The Romance of Modern Geology: Describing in simple but exact language the making of the earth with some account of prehistoric animal lifeFrom EverandThe Romance of Modern Geology: Describing in simple but exact language the making of the earth with some account of prehistoric animal lifeNo ratings yet

- Continental ShelfDocument4 pagesContinental ShelffangirltonNo ratings yet

- Sedimentary Rocks: Compaction and Cementation Are Two of TheDocument10 pagesSedimentary Rocks: Compaction and Cementation Are Two of TheweldsvNo ratings yet

- 1957 Russell The Instability of Sea LevelDocument18 pages1957 Russell The Instability of Sea Levelriparian incNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument21 pagesProjectkizzbonnyNo ratings yet

- Thesis About YemenDocument488 pagesThesis About Yemenmarwan98No ratings yet

- A Protocol For Extraction and Purification of High-Quality and Quantity Bacterial DNA Applicable For Genome Sequencing: A Modified Version of The Marmur Procedure.Document6 pagesA Protocol For Extraction and Purification of High-Quality and Quantity Bacterial DNA Applicable For Genome Sequencing: A Modified Version of The Marmur Procedure.marwan98No ratings yet

- Miswak As An Alternative To The Modern Toothbrush in Preventing Oral DiseasesDocument33 pagesMiswak As An Alternative To The Modern Toothbrush in Preventing Oral Diseasesmarwan98No ratings yet

- Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma OverviewDocument8 pagesOral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Overviewmarwan98No ratings yet

- Review On Chemical and Biologically Active Components of The Toothbrush Tree (Salvadora Persica)Document6 pagesReview On Chemical and Biologically Active Components of The Toothbrush Tree (Salvadora Persica)marwan98No ratings yet

- Bizimana Anastase&Ntiruvamunda Donatha Final ThesisDocument75 pagesBizimana Anastase&Ntiruvamunda Donatha Final Thesisngaston2020No ratings yet

- Steegmuller - Flaubert and Madame Bovary - A Double Portrait-Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1977)Document378 pagesSteegmuller - Flaubert and Madame Bovary - A Double Portrait-Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (1977)Jorge Uribe100% (2)

- Vizag Srikakulam Vizianagaram Kakinada Rajahmundry Godavari Real Estate PlotDocument9 pagesVizag Srikakulam Vizianagaram Kakinada Rajahmundry Godavari Real Estate Plotwww.hindustanpropertyhub.com Secunderabad Waltair Bezawada East Godavari West Godavari Krishna Prakasam real estate property plotsNo ratings yet

- SdefdesgaesgaesgDocument3 pagesSdefdesgaesgaesgBeepoNo ratings yet

- 112 Meditations For Self Realization: Vigyan Bhairava TantraDocument5 pages112 Meditations For Self Realization: Vigyan Bhairava TantraUttam Basak0% (1)

- Geo19 2 Climatology 1 ShortDocument81 pagesGeo19 2 Climatology 1 ShortChandu SeekalaNo ratings yet

- 购买 SATOR LNG 中介支付承诺书: Letter Of Commitment To Purchase Satorlng Intermediary PaymentDocument3 pages购买 SATOR LNG 中介支付承诺书: Letter Of Commitment To Purchase Satorlng Intermediary PaymentJIN YuanNo ratings yet

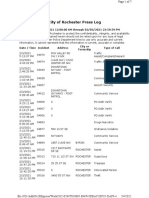

- RPD Daily Incident Report 2/3/21Document7 pagesRPD Daily Incident Report 2/3/21inforumdocsNo ratings yet

- 5e - Ley Lines & Nexuses 1.0Document21 pages5e - Ley Lines & Nexuses 1.0Russo BrOficialNo ratings yet

- Christian Worldview - PostmodernismDocument6 pagesChristian Worldview - PostmodernismLuke Wilson100% (2)

- Ethical Considerations When Conducting ResearchDocument3 pagesEthical Considerations When Conducting ResearchRegine A. UmbaadNo ratings yet

- DevynsresumeDocument2 pagesDevynsresumeapi-272399469No ratings yet

- Lecture Note 5 - BSB315 - LIFE CYCLE COST CALCULATIONDocument24 pagesLecture Note 5 - BSB315 - LIFE CYCLE COST CALCULATIONnur sheNo ratings yet

- Setting Up A Home VPN Server Using A Raspberry Pi - SitepointDocument33 pagesSetting Up A Home VPN Server Using A Raspberry Pi - SitepointSteve AttwoodNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Overview of Reliability: 1.1 Definitions and Concepts 1.1.1 Power Systems and ElementsDocument24 pagesChapter 1: Overview of Reliability: 1.1 Definitions and Concepts 1.1.1 Power Systems and ElementsThành Công PhạmNo ratings yet

- Reading PracticeDocument1 pageReading Practicejemimahluyando8No ratings yet

- Research Paper Cell Phones While DrivingDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Cell Phones While Drivingntjjkmrhf100% (1)

- Death and The AfterlifeDocument2 pagesDeath and The AfterlifeAdityaNandanNo ratings yet

- Module 4 - Ignition Systems - QSK60GDocument18 pagesModule 4 - Ignition Systems - QSK60GMuhammad Ishfaq100% (1)

- Internship Cover LetterDocument7 pagesInternship Cover LetterIeqa HaziqahNo ratings yet

- Social Responsibility in The Jewelry IndustryDocument6 pagesSocial Responsibility in The Jewelry IndustryMK ULTRANo ratings yet

- HR Policies ProjectDocument70 pagesHR Policies ProjectrmburraNo ratings yet

- BioclimaticDocument9 pagesBioclimaticHaber HaberNo ratings yet

- LangA Unit Plan 1 en PDFDocument10 pagesLangA Unit Plan 1 en PDFsushma111No ratings yet

- SS2 Chemistry 3rd Term Lesson Note PDFDocument97 pagesSS2 Chemistry 3rd Term Lesson Note PDFkhaleedoshodi7No ratings yet

- Theory and Models of Consumer BehaviorDocument28 pagesTheory and Models of Consumer BehaviorNK ShresthaNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 2.4 Object-Oriented Paradigm InheritanceDocument7 pagesWorksheet 2.4 Object-Oriented Paradigm InheritanceLorena FajardoNo ratings yet

The Vegetation of Socotra

The Vegetation of Socotra

Uploaded by

marwan98Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Vegetation of Socotra

The Vegetation of Socotra

Uploaded by

marwan98Copyright:

Available Formats

706

0.B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION O F SOCOTRA

The vegetation of Socotra. By G. B. POPOV,

Desert Locust Survey, Nairobi.

(Communicated by Dr B. P. Uverov, C.M.G., F.R.S., F.L.S.)

(With Plates 5S59 and 1 Map

[Read 24 May 19571

INT~ODUCTION

The existing literature on the vegetation of Socotra is rather scanty. The island received

much attention from the collectors a t the end of last and early in this century, when

several British and German expeditions visited the island. Important contributions

were made to the flora, chiefly by Balfour (1888), Forbes et al. (1903) and Vierhapper

(1907), but these works only contain general brief descriptions of the physiognomy of the

vegetation without an attempt at the classification of vegetation communities or types.

Similar brief references are also found in Engler (1910),and Wettstein (1906),and the

available information was used by Pichi-Sermolli (1955) in his review of the plant

ecology of arid and semi-arid zones of East Africa.

The present author had an opportunity in 1953 to spend a few weeks on Socotra in

connexion with control of the Desert Locust. A general ecological survey of the island

was carried oyt in order to investigate its possible suitability as a habitat of the locust.

An account of locusts will be published elsewhere, and B list of Saltatorial Orthoptera of

Socotra, with zoogeographical analysis of the fauna, is in the course of publication

(Popov & Uvarov, in press).

The plants collected during the visit were first examined by Mr B. Verdcourt of the

East African Herbarium, Nairobi, where the duplicates were retained. The original

specimens were later presented to the British Museum (Natural History) for final

determination by Dr G. Taylor, Miss D. Hillcoat and Mr A. W. Exell. The names of plants

referred to in this paper were subsequently checked by Mr J. B. Gillett of Royal Botanic

Gardens, Kew, who also compiled the list on pp. 717-20. The author wishes to offer his

sincere thanks to the above and to Dr B. P. Uvarov for editing this paper.

PHYSICAL GEOGRAPHY A N D SOILS

The coastal plains. The southern coastal plain of Naukad is the largest on Socotra,

being some 30 miles long and up to 5 miles wide. To a large extent it i s covered with

packed gravels, stones and coarse sand, with an overlying mantle of loose sand. The loose

sand belt runs in a ribbon along the widest part of the plain, locally developing into windblown crescentic dunes up to 7 m.high (PI. 55, fig. 1). This sand has been largely formed

through the decomposition of granites, while the beach sands, formed all along this plain,

are mainly of shell and coral origin.

The watercourses traverse the plain along single, well-defined beds of boulders and

rock slabs, without extensive fanning out or leaving finer deposits. The banks are hardly

ever more than 1 m. high, in parts exposing recent conglomerates and raised coral

beaches.

Clay and silt deposits are found along some depressions, such as at Mahallas, where the

soil is somewhat saline, or in very small quantities along the minor watercourses which,

on being blocked by sands, spill and dry up over the plain.

Elsewhere, the southern coastal plain is narrow, and much of the southern coast

presents spectacular abrupt cliffs and bluffs, rising steeply to the plateau above. These

cliffs are honeycombed with caves and fissures and there is some water seepage, which

forms tufa encrustations and deposits in many p&rts of the cliffs.

G. B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTRA

ZI

707

708

G. B. POPOV: TEE VEGETATION Or SOCOTRA

Between Ras Shoab and Katanahan there is a narrow inland basin at Nait separated

from the sea by a line of dunes, but filling up at spring tides. The water gradually evaporates, leaving a salt deposit, which is the main source of salt on Socotra. Similar basins are

said to exist in other parts of the island, as at Ras Bishuri, near Kalansiya.

The northern coast is composed of a number of smaller coastal plains, separated from

each other by rocky headlands. Kalansiya, Goba (Karma) and Hadibo plains are open

to the sea and correspond to the bays of the same name. Eastwards from Houlaf to

Momi, the lowland plains are separated from the sea by ranges of hiUs and divided by

watersheds into series of small river basins reaching the sea through narrow gorges; Kam,

Moabbadh and Khor-garieh are the major ones. From Hamadera to Ras Momi, the coast

is again formed by precipitous cliffs.

Much of the soil of the northern coastal plains, like that of Naukad, is composed of

packed gravel, stones and coarse sand, with a small admixture of clays. There are some

deposits of soft sand, on the Goba plain as thin sheets or hummocks under vegetation,

but at Houlaf reaching an unexpected thickness, covering the Houlaf promontory on the

one hand, and encroaching on to the seaward slope of Hawari hill to a height of 100 m.

or so, on the other (Pl. 55, fig. 2). It might be more than a coincidence that Acacia

edgeworthii forms an association in this area, but is rare elsewhere.

A feature common to the greater majority of the northward draining watercourses of

Socotra is the formation of estuaries, separated from the sea by sand-bars, which are

broken only by the heavy floods. The beds of rivers are covered by stones and boulders

most of the way across the plain, but h e r soils become deposited a t the estuaries, where

agriculture is practised. Even here the depth of the soil is so slight, that it is not sufficient

to take the full roots of the date palm, which on reaching the rock bed begin to arch and

bulge above the soil level.

The large river basin of Zahr was only seen from the air. No large sand deposits were

noticed, and in general appearance this area was similar to the coastal plain at Kalansiya.

The vegetation is probably akin to that of the coastal zones and not of the limestone

plateau proper.

The limestone plateau. This forms the greatest area of Socotra and varies in height

between 300 and 700 m., but in places, such as Reiged, rising to 900. Within the confines

of the limestone plateau, soil deposits are nowhere great. This area is much dissected by

gullies and ravines, and the surface worn smooth or pot-marked by erosion. Little

pockets of fhe, grey clayey soil occur in the hollows and between rock crevices, but

locally larger shallow soil deposits become accumulated in depressions,where the gradient

is slight. The largest of these were seen a t Homhil, on the summit of Reiged and the

plateau of Momi.

The granite highlands. The decomposition of granites, of which the Hagghier Massif is

built, has led to the formation of rich red soils. These have become accumulated in the

valleys and the plains and even along the less steep slopes, to form the deepest and most

fertile soil deposits on Socotra.

CLIMATE

The climate of Socotra is tempered considerably by the north-east and the south-west

monsoons and is less torrid than that of the adjacent mainlands. The temperatures

recorded by me in spring, 1953, on the coast a t Hadibo were: January, mean 24,

maximum 30, minimum 15.5; February, mean 25, maximum 31, minimum 16.5; March,

mean 26.5, maximum 32.2, minimum 18.3" C. The relative humidity during this period

varied from 75 to 90yo in the morning and from 55 to 75 yo a t midday. Occasionally

even higher humidity was recorded and morning dew was of frequent occurrence.

Higher temperatures were experienced in some of the valleys in the lowlands, and they

were usually associated with lower humidity. The highest recorded temperature waa

35" C. At higher altitudes, particularly in the Hagghier highlands, temperatures were

709

0. B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTRA

noticeably lower, particularly at night and a minimum of 13.5" C. was recorded a t

Adho Demalu (lo00 m.) in late March. Frost, however, is unknown to the inhabitants.

May is said to be the hottest month, when heat and humidity rise during the period

of calms between the monsoons. Later, the heat is relieved by the south-west monsoon,

but the high winds are dry and cause desiccation, seldom bringing rain. September is

another period of calm airs and high humidity, which ends with the onset of the northeast monsoon, blowing until early May and bringing the main rain to Socotra, with the

highest precipitation in November and December.

Table 1 is compiled from rainfall figures recorded by the Royal Air Force Station a t

Ras Karma, the only locality on Socotra where regular weather observations have been

maintained. These figures can be regarded as representative of the amount of rainfall

that can be expected in the drier parts of the island. Rainfall is said to be greater in the

eastern part of Socotra than the western and, judging by the vegetation, it is probably

higher still in the highlands generally and in the Hagghier particularly where, in addition

to the rain, frequent mists and dews occur.

Table 1. Rainfall records for Ras K a m (in mm.)

1943

1944

1945

Jan.

tr.

4.8

3-6

Feb.

Mar.

0.1

2.1

3.5

tr.

31.4

Nil

Apr.

tr.

tr.

Nil

May

tr.

Nil

June

Nil

Nil

4.3

91.0

July

Nil

0.06

tr.

Aug.

Sept.

Oct.

Nov.

Dec.

tr.

3.2

Nil

Nil

89.6

60.2

5.5

75.2

76.6

4.0

3.8

4.1

21.3

Nil

VEGETATION

I n the following pages the major vegetation communities w i l l be described in turn, then

ascribed to the nearest vegetation type outlined by Pichi-Sermolli (1955). There are two

fundamental difficulties in fitting the vegetation communities of Socotra into this general

classification. The first is due to our comparative lack of knowledge of the climatic and

other factors affecting the vegetation of Socotra, which serve as the basis for the major

divisions ofthe vegetation types in other areas. The second is due to the peculiar structure

of some of the vegetation communities on Socotra, particularly from the point of view

of their physiognomy. Thus the Croton-short grass community, so prevalent on Socotra,

has no real equivalent in East Africa, and the rock communities do not reach the same

development there as they do on Socotra. On the other hand, the Acacia-short grw

savannah, so common in East Africa, is not represented on Socotra. The classificationhas

therefore not always been obvious, and the Socotran communities have been referred to

the one or the other type on the basis of a comparison and the personal acquaintance of

the author with the vegetation communities in other parts of East Africa.

The basis used by Pichi-Sermolli for the division of the vegetation of East Africa into

two major zones-the arid and the semi-arid-has chiefly been the aridity index.

I am in general agreement with Pichi-Sermolli, who regards the greatest part of Socotra

as being within the arid zone, with a narrow semi-arid belt in the upper part of the

Hagghier range, but he overstressed the aridity of the island, a point which w i l l be made

clear in the following description.

(1) The co&stalp h i m

Maritime and halophytic communities

Avicennia nzarinu mangroves occur as local narrow belts a t a number of points along

the coasts of Socotra. One of these was seen at Gubbet Nait, between Ras Katanahan

and Ras Shoab-the locality noted for its salt deposits (p. 708). Here, the salt flats are

fringed with a woody salt-bush, Arthrocnemum sp. ?, followed inland by a sward of coarse,

spiky salt-grass, Heleochloa dura.

710

Q.

B. POPOV: THE VEOETA!PION OF SOCOTRA

The beach dunes along the southern coastal plain of Naukad are fixed seawards by the

same salt-gram (Pl. 55, fig. 3) and landwards by sea-lavender, Linzon&unz spp., and in

some places by another salt-loving woody herb, AtP.ipkx.stoch%i forma sohtrana;

these three plants appear to be frequently associated with sands of coralline or shelly

origin.

Tamarix sobtram is evidently less halophytic than the foregoing species, as it often

grows away from the coast in less saline, sometimes gypseous soils. It is most common

at Khor Garieh, where it forms a narrow belt along the upper end of the inlet, which is

evidently subject to tidal inflows. Elsewhere it is occasional; either as a subdominant

within the Linwnium association or aa a rock-plant in some of the inland valleys and

gorges, usually on tufa deposits.

Suaeda naonoica is another member of the halophytic coastal communities of the

Naukad plain, but is really common only at Mahallaa, where it fringes the palm groves,

on low-lying silty soil. The wiry grass, Ae1urop-m sp., and the beautiful, red-flowered,

spreading convolvulaceous herb, I p m e u pes-cupae, occur in small colonies on the

beaches, but the rush Juncus arabicus, which commonly grows in the brackish estuaries,

can also be found in the marshes in some inland areaa, where water is quite fresh.

Some other plants such as Sporobolus spieatus, F q m i a socotrana, ZygophyUum sp.,

Heliotropium sp., Aerva microphylla and a few others are also tolerant of salt to a greater

or lesser extent, though probably not dependent on it. These are common members of

mixed xerophytic communitieson the coastal cliffs, growing nearest to the edge of the sea.

The above-mentioned communities can be directly ascribed to Pichi-Sermollistype 1,

Maritime vegetation (arid zone).

The sand belt

On the southern coastal plain of Naukad many of the dunes are completely devoid of

vegetation (Pl. 55, fig. l), while others support a thin growth of plants (Pl. 55, fig. 4 ;

P1. 56, fig. 5). No species of plant is evidently con6ned to this area, though some,

e.g. Calotropis prmra-the

large-leaved Asclepiad, are more common here than elsewhere on the island. The perennial plants probably tap the gravel soil below and as such

cannot be regarded as truly representative of the sand belt. Among these are Indigofera

sp.nov.,l I. oblongqolia, Ziziphus sp., Salsola fwskdii, Panicum rigidum, CorchomEs

depressus, Cucumis prophetarum and the above-mentioned Calotropis procera, which are

equally common on the adjoining gravel plain free of surface sand. The numerous annual

herbs and ephemerals are probably more repremntative of sandy soils,where they grow

in greater abundance than on the gravel plains. At the time of the visit (March),most

of these were already paat their prime and the following were recorded as common:

Fqoniu paulayana, Portulaca quudriJida, Dactylocteniurn aristatum, Phyllanthw sp.,

Hdiotropium sp., Ageratum wnymides, Boerhavia repens, Cenchrus cilia&, Enneapogon sp.

and ZygophyUurn simplex. As is common in the sandy areas of the adjacent mainlands

the cornunity is characterized by nanophanerophytes and ephemerals (Pl. 56, fig. 5).

Along the northern coast, only a t Ras Houlaf are the sand deposits deep enough to

affect the vegetation. Acacia edgeworthii forms a consociation here, whilst elsewhere it is

occasional. The dominant annuals, also largely conked to the sand, being Dactyloctenium

aristaturn and a species of Cyperw. The majority of other common plants, however, also

occur on the adjoining sand-free,gravelly and stony slopes of Hawari. Of these the most

noteworthy are Indigofera cordifolia, I. nephromrp, I. colutea, S a r a latqolia,

Aerva sp., Crotalaria sp., Tribulw terrestris, Lindenbergia sokutrana, Ruellia sp. and

Arnebia hispidissima (Pl. 55, fig. 2).

intricata Boiss. in the sense of Bdfour, Bot. Socotra, Tram. R. Soc. E d i d . 31, 74 (1888).not of

Boissier, Flora 07ientdis 2, 190 (1872). To be described shortly by J. B. Gillett.

G. B. POPOV

Journ. Linn. SOC. Bot. Vol. LV, PI. 55

G. B. POPOV

Journ. Linn. SOC. Bot. Vol. LV, PI. 56

Figs. 3-8. Explanation of Plate on p. 720.

Q.

711

B. POPOV: TIIE VEGETATION OF SOCOTRA

Coarse sand, gravel and stony plaina

The &st vegetation zone inland from the sea is formed by the woody herb community

(nanophanerophytes). At Hadibo the dominant species is Indigofera sp. nov.,

frequently associated with other woody herbs such as Convolwulusfastigiatus, Campylanthus spinosus, the tussocky grass Hyprrhenia h i m , some annual herbs, Tephrosia

apolliwa, Aerva javanica, Farsetia hgii&quu and a carpet of ephemeral short grasses,

Aristida A c e m i o n i s and dlelamcenchris abyssinica (Pl. 56, fig. 6). Along the river basins

east of Houlaf, this community is but poorly represented, but some of its elements occur

within the shrub zone (see below). Between Ghadheb and Kalansiya, however, it is well

developed, reaching a width of up to 3 km. on the Goba plain.

Other common nanophanerophytes in this area are Bidens bitemzata, Aerva microphylla,

Dactyloctenium huckelii, Panicum rigidunz, Euphorbia spiralis, E . septemsuhta and a

dwarf Commiphora; each of these plants being sometimes dominant locally but rare or

even absent elsewhere (Pl. 56, fig. 7 ) .

I n addition, Aloe perryi and Euphorbia arbuacula form local isolated communities in

some areas, while occasional bushes of Salvadora persiea, Acacia edgeworthii and C&a

rotundifolia, usually growing close to the seashore, are conspicuous by their larger size.

Inland this belt is followed by the shrub zone dominated by Metred, Croton socotranus, which is easily the commonest shrub on Socotra. Sometimes it forms almost pure

stands, but is more often associated with other shrublets such as Plumpoda virgata,

Justicia rigida, Lycium sohtranum, Grewia erythraea, Ballochia amoena, Trichocalyx

orbiculatus, Dirichletia obovata, Asparagus africanua var. microcaps ; some succulents,

such as Aloe perryi and Carduma sowtrana; herbs, Aerva lanata, Clossonemu revoilii,

Cucumis jicifolius, Pedalium murex, Alzagallis arvensis, with the grass carpet formed

mainly by Aristida adscensionis and Melamwnchris abyssinica (Pl. 56, fig. 8).

This shrub zone is fairly wide, extending to the river basins and the gravelly foothills,

where it merges into the mixed woodlands on the lower slopes, or ends a t the foot of the

limestone cliffs. Its density is evidently governed by the humidity and the edaphic

factors, and some of the gravel plains along the coast support little or no vegetation.

The succession of plants leading to the climax formation of Croton shrub zone, has been

observed a t Ras Karma airfield and other parts of Socotra, where parts of the bush were

cleared for runways and roads. The first invaders were the ephemeral and annual herbs

dominated by Tephrosia apollinea, followed by such perennials as Corchorus depressus

and Cucumis prophetarum, then by perennial prostrate grass, Panicum rigidum, as a

sand-binder for small mounts of drifting sand, then bushes of Indigofera sp.nov. and last

of all Croton sowtranus. The succession has been slow due t o predation by goats and sheep

and the climax has far from re-established itselfin the eight years since the abandonment

of the station a t Ras Karma.

The vegetation communities and zones described above can safely be attributed to the

Subdesert shrub and grass type of Pichi-Sermolli, although the dominant Croton-short

grass community is not found on the East African mainland.

Minor hills and dry hill slopes

The Croton socotranus association frequently encroaches on the hill-sides and sometimes

remains dominant there. I n some localities, however, particularly at a height of

100-250 m. it becomes a t least partly replaced by the Commiphora community represented by such xerophilous elements as Comrniphora parvifolia, C. socotram, Aloe perryi,

Euphorbia nubica, E . spiralis, Barleria tetracantha, Blepharis spiculifolia, Cissus subaphylla

and others.

It is easier to regard this community as a transition between the subdesert shrub and

grass and the subdesert shrub with trees, rather than to attempt t o ascribe it to either.

JOURN. LI. SOC.-BOTANY,

VOL. LV

XH

712

Q.

B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTBA

(2) The 1-p-u

The dopes of the limestone plateau are often sheer cws, but sometimes they are less

steep, composed of tumbled-down slabs and chunks of rock and shelves separated by

stony screes. Not only is the whole limestone block honeycombed with fissures, caves

and ledges, but the individual rocks are scoured with cracks and hollows, where particles

of soil accumulate, affording foothold for vegetation (Pl. 57, fig. 11).

These slopes are veritable rock gardens, surprising for the variety of their 00ra. There

is undoubtedly some gradation with altitude, but the limits were not rigid, particularly

for some species ; the decisive factor probably being the occurrence of mists, and the main

change becomes apparent a t about 500 m. The plants growing nearest the edge of the

sea have a.lready been mentioned. A short distance above, Dendrosicyos sowtrana, Cissus

subaphyllcl, Euphmbia arbu-scuh and Adenium sokotranurn combine to form a landscape

peculiar to Socotra (Pl. 57, fig. 9), together with some Euphmbia nubicu, E . spiralis,

Commicaryuus sp., Mmrma sowtrana, Withunia riebeckii, Cynanchum linifolum. In

addition, the Croton sowtranus community becomes established wherever soil deposits

are suEcient to permit its development.

The annual and perennial herbs are equally varied and abundant, and the commonest

recorded were Triclwdesma microcalyx, Pdiearia skphuwcurpa, P . diversifolia, Corchorus

erodioides, Lactuca r h y n c k r p a , Crotdaria leptocarrpa, Ipowweu blepharocephah,

Boerhavia repens, M e o k ~ g ominim, Convoldus q k r d u s , Oldenlandia pulvinata, and

the ferns Actinbpteris austrdis and Adiantum balf.u.ii.

At the height of 500 m. and above, rock-plants are represented by Dorstenia gigas,

Kleinia swttii, Ficus sowtrana, Boswellia sp., presenting an equally characteristic if

somewhat different appearance (Pl. 57, fig. 10). Other common elements within this

mixed community are BosweUia sp., Tetragoniapentandra,Adenium socotranum, Euphorbia

oblanceolata, Hibiscus swttii and some others (Pl. 57, fig. 11).The young seedlings usually

require a small quantity of soil but, once established, the plants appear to draw sustenance

from the bare rock.

Other plants, such as Psetdomussm& q d ~ e r aPolymrpaea

,

spicata, P . de'varicuta

and Haya obovata, grow suspended from ledges of rock. Yet others are only found growing

in pockets of dark rich soil, deep in the crevices of rocks; of these Begonia sowtrana,

Exmum afine, Peucdanum wrdatum and the fern Adiantum balfourii are the commonest. A greater number, however, show preference for screes, shelves and valleys,

where some soil becomes accumulated. Where soil deposits are poor, the vegetation is

characterized by succulents such aa Aloe perryi, Kdancluw farinacea, K . robu-sta and

some small woody herbs-Melhunia

murim%, Diceratella incana, Leucas urticifolia,

Helichrysum gracilipu, Teucrium sohtranum, in addition to the above-mentioned rock

plants and an occasional E u p h b i a arbuscuh. I n sheltered valleys, where soil deposits

are more abundant, sometimes fairly dense thickets become established; here the

commonest shrubs and trees are represented by Ruellia insignis, Ormcurpum caerukum,

Acacia pennivenia, Dicliptera effusa, Croton sulcif&us, Psiadia schweinfurthii, Vemnia

cockburniana, Rhus thyrsi)?ora, Ficus sowtrana, Justicia heterocarpa, Acridocarpus

sowtranus and Cissu-s quadranqdaris. These are bound by lianas and creepers, such aa

C. panicuhta, Tragia bdfourhna, Curroria decidua subsp. volubilis and Diosmea lamta.

The above description is based on the vegetation of Reiged, the 900 m. high limestone

bluff west of Hadibo. Although the majority of the plants mentioned were also found in

the other parts of the limestone plateau, the composition of the vegetation varied and

the dominants in one locality were sometimes rare or absent in others. The most noteworthy example is the Drmnu-Boszuellia community on the slopes of the Hamadera

hills a t Homhil (Pl. 57, fig. 12), chiefly composed of Dramena cinnubari,Bomellia ameero,

B. elcrngata, B. sowtrana, Aloe perryi, Adenium sokotranum and Mitolepis intricata. While

Dramena is more wmmon on the limestone slopes, B d l i a predominates on the plain

G. B. P O P O V

Journ. Linn. SOC. Bot. Vol. LV. PI. 57

G. B. POPOV

Journ. Linn. SOC. Bot. Vol. LV, PI. 58

Figs. 13-16. Explanation of Plate on p. 720.

G. B. POPOV

Journ. Linn.

Fig. l i

SOC. Bot. Vol. LV, PI. 59

713

0. B. POPOV: WE VEQETA!t'ION OF SOCOTRA

where, in addition, a species of Lunnea, not seen elsewhere, forms a small shady grove.

The vegetation on the southern hills surrounding Homhil is rather different, forming

a mixed shrub thicket, the main components of which are Rhus thyrsifEwa, Dirichktia

venulosa and Punica protopunica.

Lannea aspleniifolia is a common member of the communities on the limestone slopes

inland from Kalansiya, but rare elsewhere, while the vegetation of the cliffs along the

southern coastal plain is characterized by a predominance of rock plants, chiefly shrubs,

such as Boswellia spp., Dyerophytum pendulum, Cyptolapis wbicularis, Cochlunthus

socotranus, Secamone sowtrana, Euphorbia oblanceolata,E . nubica, Hibiscus swttii, Barleria

spinma and Dorstenia gigas.

The altitudinal zonation is also variable; for example, along the northern coast,

Dorstenia gigas is seldom seen below 500 m., while along the southern coast it is commonly

encountered down to 100 m.

With the exception of the thickets found in the sheltered valleys, the communities of

the limestone plateau described so far can be ascribed to the subdesert shrub with trees

LW has been done by Pichi-Sermolli. The mixed thickets ofthis region, together with those

on the lower slopes of the Hagghier, on the other hand, may be referred t o the subdesert

bush and thicket (type 6 of Pichi-Sermolli).

By contrast with the slopes, the top of the main limestone plateau is remarkably arid.

The perennial vegetation is rather scanty, consisting of stunted bushes of Jatropha unicostata, Croton socotranus, Picus socotram, Adenium sokotranum, Aloe perryi and an

occasional Dracaena cinnubari. The annual vegetation is more abundant, being chiefly

composed of grasses-Hyparrhenia hirtu, Arthraxm lancifolius, Aristida funiculata,

Cymbopogon sp. and Pennisetum setaceum ; some herbs-Asphodelus tenuifolius, Digera

alternijolia, Achyranthes aspera and some others (Pl. 58, fig. 13).

Here again there is some difference in the plant composition between the various parts

of the island: thus the community populating the summit ofthe Hamadera hill is chiefly

characterized by low woody perennials such as Mitolepis intricata, the larger shrubs and

trees being absent. The watershed between the coastal valley of Kalansiya and the Goba

plain supports a thin growth of Jatropha uniwstatu and Adenium sokotranum, in parts

replaced by the Croton association.

The paucity of the vegetation on the plateau may not be so much due to the soil and

aridity, since many vegetation communities develop well on rocky slopes under even

more arid conditions, as to the high winds, particularly during the south-west monsoon.

It is significant that vegetation was found to be much better developed in ravines and

gorges where the adjoining cliffs afford some protection. Thus on Reiged, mixed thickets

have developed on the uppermost shelf, but are absent from the summit.

Parts of the limestone plateau are indeed so sparsely clothed with vegetation that one

feels tempted to ascribe them to the desert vegetation, as has been done by PichiSermolli on the information provided by Balfour (1888). However, the sparsity of the

vegetation here is mainly due to one outstanding climatic factor (wind) and not general

d a e r t conditions, and many of the species found here are prominent members of the

semi-arid vegetation elsewhere on Socotra. In all fairness, therefore, one should refer

the largest part of the limestone plateau t o the Subdesert shrub and grass type of PichiSermolli, with islands of less arid vegetation belonging to the Subdesert shrub with trees

and the Subdesert bush and thicket types.

(3) The granite massij of the Hagghier

Along the northern slopes, the coastal shrub-zone extends to the foothills, where it

merges with the mixed thickets composed of a variety of shrubs such as Jatropha unicostata, Dirichletia obovata, Cordia obovata, Cylista sp., Acridocarpm socotranus ; trees like

8krculia rivae, Aberia abyssinica and Tamarindus indica, and an undergrowth of herbs

and annuals such as Tewrium balfourii, Leucas neu$izeana, L. urticifolia, L. virgata,

xx-2

714

G. B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCO"E.4

Jwtkia heterocarpa and many others mentioned for the shrub zone and the lower slopes

of limestone plateau (Pl. 58, fig. 14).

With an increase in altitude, and presumably rainfall, vegetation becomes denser;

many of the elements mentioned for the higher slopes of the limestone plateau such as

Rwllia insig.niS, Rhw thyr&@a, ownmwpum CaeFUleum, Ckrodendmmg&um are also

fairly common here, but some due to better edaphic conditions preeent a somewhat

different "pect. Thus, Fkw socotmna, which in the limestone belt grow as a stunted

rock shrub, here develops into a h e spreading tree.

There is no difficulty in ascribing these mixed thickets together with those of the

sheltered valleys of the limestone region to the subdesert bush md thicket type of PichiSermolli. These thickets gradually change to the evergreen thickets of the Hagghier

Highlands, which belong to the semi-arid vegetation zone.

The main change in vegetation becomes apparent at an altitude of over 750 m., where

many elements appear for the Srst time. The vegetation of the Hagghier Highlands may

be divided into three main types: the grasslands, the thickets and the association of

woody herbs. One might include the rock vegetation, but this community does not reach

the same development on granites, as on the limestone. The surface of rocks is covered

with lichens so thickly that the naturally pink granite appears grey from a distance.

The higher forms of flora, however, are restricted to the occasional fissures where succulents such as K&nchoe farinacea, K . roclm&i;folia,

Aloe per+, and some herbs such aa

Exmum a@m, 2. mruleum and Begonia socotrana find a foothold. However, there

appear to be no rock shrubs.

The grmshnda are to a large extent composed of The&

pwadrivaEvis, Hypwhenia

hirta and Arthramn hncqoliw (Pl. 58, fig. 15). They form the main pastures for the

Socotran cattle and cover a fairly large area of the watershed between the granite peaks.

The division between the grasslands and the thickets is a very sharp one.

The thick.& occupy the lower slopea of the highlands, but are absent from the steeper

peaks. Their specific composition is a rich and varied one, the following being the

commonest in order of their dominance: shrubs and small trees-Cep?u&croton sowtranus, Carissa eddis, Bum~shildebrandtii, Dodonaea viscosa, Ficus sowtrana, Indigofera solcotrana, RueUiu insignis, BosweUia amzero and E u p h b i a soeotrana; smaller

bushes--iliedyotis stellarioides, Hypoestes pdmwm, Ahphylus rAwiphyUus, together

with a tangled undergrowth of Cocculus balfourii, C i s w qu.udran&aris, the twining

Traqia baifourianu and E&kp8ds sp. and the Dioscorea h&

lianas (Pl. 58, fig. 16).

The community of the woody herbs develops on the stony slopes leading steeply from

the watershed, where it replacea the grasslands and the thickets. This is characterized by

such species as Euryqs socotranus, Hypericum torCuosum, H. mysorense and Aerva

revol'uta, with an h o s t Alpine appearance. Other common perennial and annual herbs

include Pluchea obovatu, P.aromatics, Pulhria vier&,

&idia socotrana, hillonia

puberula, lsatureja remota, Sigeshkia opientalk and Ldw munwpsis.

fiacuem cindmri is fairly common, though never as dominant as at Homhil; the

other plants noticeable for their appearance being the flat-topped Commiphora plunifrom and laxge-leaved amaryllid, Haemanthus grandifolius.

The higher peaks of the Hagghier, above 1200 m., were not visited, but according to

the eaxlier deacriptions, they are characterized by such woody herbs as Nirarathanznos

ma&foliw, Diehrmphlu chrysanthmifoliu and various species of Hdichrysum.

The vegetation of the Hagghier Highlands belongs to the semi-arid zone, and one can

attribute the T-Bpwhenia

grassland to the Open gradand and the thickets

to the Evergreen scrub (types 3 and 4) of Pichi-Sermolli. The nanophanerophytic

community of the Hagghier is less easy to classify. Climatically it belongs here, physiognomicdy to the Subdesert shrub and grass type of the arid zone. Perhaps it is best to

regard it as part of the Evergreen scrub type.

The southern slopes of the Hagghier are more arid than the northern, particularly at

Q. B. POPOV: THE VEQETATION

715

OF SOCOTEA

lower altitudes, where mixed thickets soon become replaced by the Croton shrub, or

Boswellia--succulent communities, which in the southern part of Socotra extend to a

greater altitude than in the northern. Aloe forbesii, in this area, almost completely

replaces A. p w y i .

(4) Riverim communities

The majority of the streams on Socotra are sporadic, carrying water only during and

for a short time after rains. In their upper reaches, particularly, the vegetation fringing

these runnels is hardly different from that of the adjoining slopes. There are, however,

a number of springs, streams and pools and some river estuaries, which retain water for

a greater part of the year and thus encourage the formation of plant communities not

represented, or at least not so fully developed elsewhere. The following are the most

noteworthy.

( a ) The semi-aquaticcommunity represented by Juncwr arabicus consociation, which

forms along most estuaries, as well aa along some of the stagnant pools and springs in

the interior, where in addition it includes the tall sedge Cladium m r i s c u s .

The shallower parts and edges of sluggish streams are lined with Lythrum hyssopifolia, Phyla rwdijbra and with the aquatic graas, Paapalidium gemidurn, growing in

deeper water. In sheltered parts along the edge of streams, ferns such as Pteris vittata

and Adianbm balfmrii are common. The upper parts of estuaries, where water begins

to stagnate, are carpeted with a low spongy growth of sedges and grasses of the genera

Fimbristylis, Cyperus, Erapostis and Paapdidium.

( b ) The date palm, Phoenix dactylifera, which is the main cultivated plant on the

island, is planted along the streams, where water-table was high and wherever soil

permits this. In addition, the streams with the water at or near the surface are lined

with groves of Ficus salicifolia, Euclea sp., Cordia obtusa, Acridocurpus socotranus, and

Buxw hildebrandtii with an occasionallarger tree such aa Sterculia rivae, Lunma ornifolia,

Tamarindus indica and Ziziphus sp., the latter usually associated with drier conditions.

There are also many herbs, particularly common along these watercourses: Leucas

virgata, Ocimum hadienae, Hypoestes sobtram, Cassia tora, Heliotropium zeylanicum,

Hibiscus sidiformis, Aerva javanica, Pedulium murex and Ver?wnia cineraacem being the

most prominent, while the ephemeral grasses are represented by Aristida adacemionis,

Chloris barbata, Cenchrus setigerus, Rhynchdytrum microstaehyunz, Apluda mutica and

Heteropogon contortus (Pl. 59, fig. 17).

(c) The drier, sandy stretches of main watercourses, where surface water is absent

most of the year, such aa the one at Hodaf, are characterized by Ziziphus sp., Ochra&nus baccatus, and such herbs aa Aerva javanica, Tephrosia apllinea, C l e m sp. and

Ruta graveolens.

The above description is based on the Hadibo plain, but is generally true of the northern

coast aa a whole. The valleys of the southward draining rivers, which cross the Naukad

plain, were found to be larger and more arid and the change of the vegetation more

gradual. The southern riverine valleys of the Hagghier contain groves of the wild orange

Citrus aurantium,A c r h w socotranus,Peperovmiare$exa, Ziziphus sp. and Tamarindus

trees together with an occasional Borassus palm. The lower reaches support Ziziphus

sp. and the much-branching smaller Ziziphus sp., the latter persisting all the way to

the coastal plain, where the sandy dry bed of rivers is, in addition, dotted with bushes of

Aerva microphylla, Indigofera sp.nov. and Dadyhtenium hackelii much more densely

than the adjoining plain (Pl. 59, fig. 18).

( 5 ) Agriculture

Most of the flood waters quickly drain off Socotra, but a small quantity becomes

absorbed and later reappears as small streams and springs. The granite range is particularly water-bearing and many streams draining from this range are said to flow for about

xx-3

716

a. B. POPOV:

THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTEA

eight months in a year, while permanent springs abound in this region. The limestone

plateau is much more arid, particularly a t the western end of the island, but even here

there are a number of permanent springs, while small amounts of rain wafer, which

collect in hollows, may sufice for human consumption for up to 3 months after rain.

On the southern coast, water is scarce, limited to one or two springs at the base of cliffs

and several wells of brackish water. On the northern coast, the estuaries of larger rivers

retain water for most of the year and water-table is high at Hadibo, Ghadheb and

Kalansiya, where nearly every household has its well. On the Goba plain, however,

water is brackish.

Agriculture is practised on a smali scale. Date gardens exist along most estuaries and

river basins on the north mast, while on the southern, there is an extensive plantation

at Mahallas. Where soil is inadequate for the growth of the plant, additional soil is piled

up against the roots, within a circular stone wall, giving the palms the appearance of

growing in pots.

Vegetable gazdens, irrigated from wells, exist at Hadibo and one or two other villages

along the north coast. Sweet potatoes, pumpkins, cotton, tomatoes, pepper and some

other vegetables are grown for household use.

There are also one or two small fields of finger millet (Eleusinecwacana) a t Moabbadh,

irrigated from the adjoining stream. These are said to be the property of the Sultan and

are probably still in the experimental stage.

Wild orange trees (Citrus aurantium) are found in abundance in the valleys of the

southern Hagghier. The plant may have been originally introduced, but appears to be

growing wild now. The pods of Tamrindus indica, the berries of Cordia sp. and some

other indigenous plants such as G h s m m a revoilii (fruit)and Dwswrea h m h (tubers)

are eaten.

Although most of the population of Socotra is pastoral, and stock breeding is undertaken as keenly as on the adjoining SomalilandPeninsula, overgrazingdoes not seem to be

a problem on Socotra. This is almost certainly due to a balance of stock population

maintained by natural causes in the absence of veterinary services, rather than to any

control by the inhabitants. I n any w e , the recent census shows no notable increase in

either human or stock population since the end of the last century, or even compared

with the figures given by early travellers.

(6) Weeds of cultivatim

Many of the weeds have probably been introduced relatively recently, as suggested by

their abundance in the cultivations in the vicinity of villages and their relative rarity

elsewhere. The commonest noted were Argemme qnexicana, Portulaca oleracea, A i m

mnariense, Trianthma penhndra, Psoraleu wrylijolia, Datura metel, Solanum

coagukcns,Cassia h a , Cassia sp., Ricinus unnmunis and some others. These are common

both in the palm-gardensand the small vegetable gardens near the villages. Other weeds

are often also common members of the coastal and some other communities on the

island, and a few of them are endemic to Socotra. Of these, Hdiotropium dentaturn,

ZygophyUum simp&, Achyranth aspera, Digera alternifolia, Indigofera tinctoria and

Sida mats are the most noteworthy.

SUMMARY

Our information on the extent and the distribution of the vegetation types on Socotra

referable to the arid zone may be summarized as follows:

1. Maritime vegetation is present over small areas along the coast of Socotra. The

observed communities have been described and similar, or slightly different, ones are

believed to exist to a limited extent in other parts of the island which were not seen, such

as near Kalansiya and a t Shoab and possibly elsewhere.

G . B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTBA

717

2. Deszrt vegetation. No vegetation community can truly be ascribed to this type.

There are limited gravel and sand stretches on the coastal plain, where the paucity of the

vegetation is due to edaphic aridity, and parts of the limestone plateau, where perennial

growth is reduced by winds, but the existing vegetation can be described as a debwed

form of other plant communities reaching the climax under more favourable conditions.

3. Subdesert shrub and grass covers most of the island, i.e. the whole of the southern

coast, most of the northern coast and the western and central parts of the limestone

plateau.

4. Subdesert shrub with trees is another well-represented vegetation type, comprising

the rock communities of the limestone slopes, the BosweUia-Drc,cuenu community of

Homhil and possibly other similarly sheltered parts of the limestone plateau.

5 . Subdesert scrub is not represented, a t least in its typical composition. On the basis

of the vegetation cover one might possibly regard the denser Croton formations aa

belonging to this type, but this would be atypical in relation to the communities

characteristic of this type.

6 . Subdesert bush and thicket. The mixed thickets of the lower slopes of the Hagghier

and some of the sheltered valleys within the limestone region, such as the Goahal gorge

can only be ascribed to this type, even though somewhat atypical.

7. Xerophikvus open woocuand is not represented in its typical composition.

8. Vegetation of sites where water is present includes numerous riverine communities

and the cultivations of Socotra.

9. Vegetation of semi-arid type. The vegetation of the semi-arid zone is confined to the

highlands of the Hagghier, above the height of 850 m., where only two vegetation types

can be recognized, the Open grassland and the Evergreen scrub.

Species referred to in G. B. Popovs paper, The Vegetation of Socotra

by J. B. Gillett, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Families in the sequence of Bentham and Hooker, Genera Plantarum

Taxa marked with an asterisk are believed t o be endemic t o Socotra, those with

two asterisks belong to genera endemic to Socotra (in view of our imperfect botanical

knowledge of the Horn of Africa these statements must be considered as provisional).

Menispermaceae

*Cocculua balfourii Schweinf. ex Balf. f.

Papaveraceae

Argenwne m x i c a n a P.

Cruciferae

*Diceratella incana Balf. f.

Farsetia longisiliqua Decne.

Capparidaceae

Cadaba rotundifolia Forsk.

Cleorne sp.

Maesocotrana (Schweinf.) Gilg

Resedaceae

Ochradenua baccatua Del.

Flacourtiaceae

Aberia abyssinica clos

Caryophyllaceae

**Haya obovatu Balf. r.

*Polycarpaea divaricatu Balf. f.

P . spicata Wight ex Am.

Portulacaceae

Portulaca oleracea L.

P . quadri;fida L.

Tamaricaceae

Tamurix aokotrana Vierh.

Hypericaceae

Hypericum mysorense Wight & Am.

*H. tortuosum Balf. f.

Malvaceae

*Hibiscus scottii Balf. f.

H . siclifomis Baill. ( H . t e m t w r (c8V.)

Mast. not of Cav.)

Si&a ovata Forsk.

Sterculiaceae

Melhania muricata Balf. f.

Sterculia rivae (K. Schum.) Chiov.

Tiliaceae

Corchorus depressus (L.) Chistens.

*C. erodwides Balf. f.

G e e erythraea Schweinf.

Malpighiaceae

*Acridocarpua socotranwr Oliv.

Zygophyllaceae

*FagoniapaulayarmWagn. & Vierh.ex Vierh.

F . sowtrana (Balf. f.) Schweinf.

G . B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTBA

717

2. Deszrt vegetation. No vegetation community can truly be ascribed to this type.

There are limited gravel and sand stretches on the coastal plain, where the paucity of the

vegetation is due to edaphic aridity, and parts of the limestone plateau, where perennial

growth is reduced by winds, but the existing vegetation can be described as a debwed

form of other plant communities reaching the climax under more favourable conditions.

3. Subdesert shrub and grass covers most of the island, i.e. the whole of the southern

coast, most of the northern coast and the western and central parts of the limestone

plateau.

4. Subdesert shrub with trees is another well-represented vegetation type, comprising

the rock communities of the limestone slopes, the BosweUia-Drc,cuenu community of

Homhil and possibly other similarly sheltered parts of the limestone plateau.

5 . Subdesert scrub is not represented, a t least in its typical composition. On the basis

of the vegetation cover one might possibly regard the denser Croton formations aa

belonging to this type, but this would be atypical in relation to the communities

characteristic of this type.

6 . Subdesert bush and thicket. The mixed thickets of the lower slopes of the Hagghier

and some of the sheltered valleys within the limestone region, such as the Goahal gorge

can only be ascribed to this type, even though somewhat atypical.

7. Xerophikvus open woocuand is not represented in its typical composition.

8. Vegetation of sites where water is present includes numerous riverine communities

and the cultivations of Socotra.

9. Vegetation of semi-arid type. The vegetation of the semi-arid zone is confined to the

highlands of the Hagghier, above the height of 850 m., where only two vegetation types

can be recognized, the Open grassland and the Evergreen scrub.

Species referred to in G. B. Popovs paper, The Vegetation of Socotra

by J. B. Gillett, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Families in the sequence of Bentham and Hooker, Genera Plantarum

Taxa marked with an asterisk are believed t o be endemic t o Socotra, those with

two asterisks belong to genera endemic to Socotra (in view of our imperfect botanical

knowledge of the Horn of Africa these statements must be considered as provisional).

Menispermaceae

*Cocculua balfourii Schweinf. ex Balf. f.

Papaveraceae

Argenwne m x i c a n a P.

Cruciferae

*Diceratella incana Balf. f.

Farsetia longisiliqua Decne.

Capparidaceae

Cadaba rotundifolia Forsk.

Cleorne sp.

Maesocotrana (Schweinf.) Gilg

Resedaceae

Ochradenua baccatua Del.

Flacourtiaceae

Aberia abyssinica clos

Caryophyllaceae

**Haya obovatu Balf. r.

*Polycarpaea divaricatu Balf. f.

P . spicata Wight ex Am.

Portulacaceae

Portulaca oleracea L.

P . quadri;fida L.

Tamaricaceae

Tamurix aokotrana Vierh.

Hypericaceae

Hypericum mysorense Wight & Am.

*H. tortuosum Balf. f.

Malvaceae

*Hibiscus scottii Balf. f.

H . siclifomis Baill. ( H . t e m t w r (c8V.)

Mast. not of Cav.)

Si&a ovata Forsk.

Sterculiaceae

Melhania muricata Balf. f.

Sterculia rivae (K. Schum.) Chiov.

Tiliaceae

Corchorus depressus (L.) Chistens.

*C. erodwides Balf. f.

G e e erythraea Schweinf.

Malpighiaceae

*Acridocarpua socotranwr Oliv.

Zygophyllaceae

*FagoniapaulayarmWagn. & Vierh.ex Vierh.

F . sowtrana (Balf. f.) Schweinf.

718

-0.B. POPOV:

THE VEQETATION OF SOCOTBA

Zygophyllaceae (wnt.)

Tribulue twrsstris L.

ZygophyUum &n&x L.

Rutacese

Ruta gravwkm L.

Citrcls mrantium L.

Buraera.ceae

*BosweUia ~umeeroBalf. f.

*B. ebngata Balf. f.

*B. 8oCOi%KMU&Balf. f.

C m p m w f & (Bslf.f.) -1.

*C. p h n i f m (Balf.f.) Engl.

eowmna (Belf.f.) Engl.

Rhemnaceaa

Zizyphua sp.

Vitaceae

* C k m pun(Balf.f.) Planch.

qua&L.

*C. uubqvhyllu (Balf. f.) Planch.

Sepindweee

D0dona;ea viawsa (L.) Jwq.

*AlbpbyLua rhuuiphyllua Mf.f.

*c.

c.

*Lanneuq h G f o l i a (Balf.f.) Engl.

*L. orn$oZia (Belf.f.) Engl.

*Rhw thyrsiijlore Balf. f .

Leguminosae: Pspiliomtse

cram lt?ptouwpa Balf. f .

c y l k h Sp.

Indigofera wlutm (Burm. f.) Merr.

I. wrdifolia Heyne ex Roth

I. m p h m r p a Balf. f.

I . obbngifolia Forsk.

*I.aokotrana Vierh.

I . tinetoria L.

*Loworro1Eop8iB Balf. f.

Medimgo mimima L.

Ornwmrpum caertJeum Balf. f.

P 8 0 r h W9yc%fO&J L.

T e p h r o h apollineu (-1.)

Link.

Caesalpinioideaa

C a a h tura L.

Tamm-indua indic0 L.

Mimosoideaa

Acacia edgeuwthii T.Andera. (A. sowtmna

Balf. f.)

*A.pennivenia Balf. f.

Crassulaceae

*Kahne?we farinacm Balf. f.

*K. robuatu Balf. f.

K. rotundifolia Haw.

Lythr&CeaS

Lythmm hyaao@fo&z L.

PUnim*Punica potopu7aic0 Balf. f.

Cucurbitaceae

Cucumkjkifoliua A. Rich.

C. prophtarum L.

**Dend.ro&yoa soc~tranaBalf. f.

Begoniaceaa

*Begonia s o c ~ & a n aHook. f.

Aizoaceas

Aizom canarkme L.

*Tetregoniapentandm Bslf. f.

TAnthema penta;ndra L.

Umbelliferae

* * N k r a t h ~ w a.8a&foliua

a

Balf. f .

*Peucedanum cmdatum Balf. f.

Rubiweae

D .w.d k t i a obovata Balf. f.

*D. wn&sa Balf. f.

* # a h & pube&

Balf. f.

*HedyotiS atelkBalf. f.

*O,!ddandia pubinafu (Balf. f.) Vierh.

**Pluwpodu virgata Balf. f.

(Balf. f.)

WeRlh8ITl

Compositse

Ageratum conyzoides L.

Bidens W m d a (Lour.)Merril & SherfT

Dichmcephula &rysanthem@olia (Bl.) DC.

*Euryopam t r a n u a Balf. f.

Heliohryeclm

Oliv. & Hiern.

*Kkinia ecoti% (Balf. f.) Chiov.

+La;ctuccr rhyndwmrpa Balf. f.

* P l u c k aromatic0 Balf. f.

*P. obovatcr Balf. f.

*Peia&io achweinfurthii BaH. f.

*Pdkwia divemifolia Balf. f .

*P. atepha7wmrpa Balf. f.

*P. viemeoides Balf. f.

Sigeabkia orienta2is L.

Ver?wniacimraacem Sch. Bip.

* V. cockhrniana Balf. f.

Plumbrrginsceae

*Oyemphytum penddum (Balf. f.) Kuntze

Sp.

Primulaceae

AnagaUis amen& L.

Salvadoraceaa

s

u persica L.

Ebenweae

E u c h ap.

Apocynmeaa

*A&niumaokotranum Vierh.

C&sa eddk (Forsk.) Vahl

Asclepiadaceae

Calotropia p c e r a (Ait.) Ait. f.

Carallurn eocotrana (Balf. f.) N.E. Br.

**Cochlcmthuaaocotranua Balf. f.

Cryptokpia m~ularischiov.

Curroria decidua Planch. ex Benth. sap.

volubilis (Balf. f.) Bullock

* C p n e h u m linifolium (Balf. f.) Bullock

comb.nov. (Viwtoxkum linifolium Balf.

f. in Proc. R. SOC.Edinb. 12, 79 (1884))

Ectudiop& sp. (aensu Bdf. f.)

c f b a a a m a rev&& Franch.

*P8f3UdO?nU&W43dU @$E?'tZ

0.B. POPOV: THE VEGETATION OF SOCOTRA

*+Mitole@ intPicarla Balf. f.

*Secamne socotranu Balf. f.

Gentianma

*Emcum aflne Balf. f.

*E. CaeruIeUllz Balf. f.

Boreginaceae

Arnebia hiepidkeinut (Lehm.) DC.

*Cordia obowcta Balf. f.

*C. o b t m Bdf. f.

*Helwtl.qpium dentaturn Belf. f.

H . zeylanicum (Bunn. f.) Lam.

*Trichodesma microdyx Balf. f.

Convolvulaceae

Conuolvulw,faatigiatua Roxb.

C. gbmeratua Choisy

Ipomoeu bkpbrosepak Hochet. ex A. Riah.

I . p c a p m (L.) Roth

SeclcEeralatifoliaHochat.&Steud.exHochst.

Sol&naceae

Datura metel L.

*Lycium sokotranum wagn. & Vierh.

Sohnum waguhm Forsk.

* Withania riebeckii Schweinf. ex Balf. f.

Scrophulariacem

*Campylanthua s p i n o m Balf. f.

*Lindenbergia sohtrarm Vierh.

Pedaliaceae

Pedalium murex L.

Acanthaceae

**BaUochia a m e n u Balf. f.

Bark& apinosa Hook. ex Nees

*B. tetracantha Balf. f.

*Blepha& S p i c d i f O h Balf. f.

*Dicliptera effaa Balf. f.

*Hypoestes pubescens Balf. f.

*H. aokotrana Vierh.

Juaticia hetwocarpa T . Andera.

*J.rig&

Balf. f.

*Ruellia imignis Balf. f.

+Trichocalyx orbiculata Balf. f.

Verbemceae

Avicennia marina (Forsk.) Vierh.

*Clero&ndrum galeatum Balf. f.

Phyla nodifira (L.) Greene

Labiatae

Leucm neuflizeana Courb.

L. urticiifolia (Vahl) Benth.

*L. virgata Balf. f.

Ocimum hadieme Forsk.

*Satureja r e m t a (Balf. f.) Vierh.

*Teucrium balfourii Vierh.

*T.sokotranum Vierh.

Nyctaginaceae

Boerhavia repens L.

Commicarpua sp.

Amaranthaceae

Achyranthes apsera L.

Aerva javanica (Bunn. f.) Jw. ex Schult.

A. lanuta (L.) Juss. ex Schult.

719

A. microphylla Moq.

*A. revoluta Balf. f.

Digera altemifolia (L.)Aachera.

Chenopodiaceae

Arthmmum sp.

Atripkx stock& Boies. forma mkotrana

(Vierh.) Vierh.

Sdaola forakulii Schweinf.

Suaeda monoica Forsk.

Thymedleaceae

*&id& sowtrana (Balf. f.) Gilg

Buxeceae

B u x u hildebrandtii Baill.

Euphorbiaceaa

*Cephaloeroton sowtranua Balf. f.

*Croton socrotranua Balf. f.

*C. &+uctua Balf. f.

*Euphurbia arbuaula Balf. f.

E. nubica N.E. Br.

*E. oblanceolala Balf. f.

*E. septemsulcato Vierh.

* E . socotrana Bdf. f.

*E. spiralis Balf. f.

*Jatrophu unicostda Balf. f.

PhyUanthua sp.

Ricinua wmmunk L.

*Tragia balfou&na Gillett nom.nov. (T.

dioica Balf. f., Proc. R.Soo.E d i d . 12.96

(1884), non Sond., LinlMea 23,109 (1860))

Moraceae

*Dorstenia gigas Schweinf. ex Balf. f.

Fkua d i c i j o l i a Vahl

*F.aocotrana Balf. f.

Amaryllidaceae

*Haemanthus grandifoliua Balf. f.

Dioscoreaceae

*DiosCorea; lanuta Bdf. f.

Liliaoeae

*Aloeforbaeii Balf. f.

* A . perryi Bak.

*Asparapa a f k n u a Lam. var. microcarpua

Balf. f.

Asph~deluatenuifoliua Cav.

*fiacuena cinnubari Balf. f.

Juncaceae

Juncua arabicua (Asch. & Buch.) Adameon

Palmaa

Bwaaeus sp.

Phoenix dactylifera L.

Cyperaceae

C2adium ma&cua R. Br.

Cyperus sp.

Fimbri8tyliS sp.

Graminern

Aeluropua sp.

AplwEa mutica L.

Aristida adscensionis L.

A. f u n i c h Trin.& Rupr.

Arthraxon lancifoliw (Trin.)

Hochst.

720

U. B. POPOV:

THE VEUETATION OF SOCOTRA

Gramineae (cont.)

Cenchma ciliaria L.

C . eetiqem Vehl

Chloris barbata Sw.

cymbopgcm sp.

DactyEoctenium ariataturn Link.

* D . hackelii Wagn & Vierh. ex Vierh.

Eleusine wrwm (L.) Gaertn.

Enneapgcm sp.

Eragroath sp.

Heleochloa dura B o k .

Heteropogorr contortue (L.)Beauv. ex Roem.

& Schult.

Hypawhenia hirta (L.) Stapf.

Melunomnchria aby&nku (R.Br. ex Free.)

Hochst.

*Panicumrigidurn Balf. f.

Pmpalidium geminaturn (Forsk.) Stapf.

Pennisetum setaceurn (Forsk.)Chiov.

*Rhyn&dytrmn rnicroatachyum Balf. f.

Sporobolus apic&ua (Vahl)Kunth

The&

quudrivalvia (L. f.) Kuntze

Filiceg

Actinbpteria australis (L. f.) Lk.

*Adianturn Wfmhi Bak.

Pkh8 V'il%Zi% L.

REFERENCES

I. B., 1888. Botany of Socotra. Trans. R. SOC.Edinb. 31, 1-446.

BALFOUR,

ENGLER,

A., 1910. Die PponZmwelt A f r i h , imbesmzdwe seiner tropkchn Gebkte. 1030 pp. Leipzig.

FORBES,

H. 0. et al., 1903. The. N a . t u d iktory of Socotra and Abd-el-Kuri, 598 pp. Liverpooli

PICHI-SERMOLLI,

R. E. G., 1955. Tropical East Africa (Ethiopia, Somaliland, Kenya, Tangan-).

Arid Zone Research. 6 , 302-360. Plant Ecol., UNESCO, Paris.

VIERHAPPER,F., 1907. Kenntnk der Flora Siidarabiens und der Inseln Sokotra, &mh8 und Adb el

Kuri. Denhhr. A M . Wise. Wien, 1, 321-490.

WEITSTEIN,

R.. 1906. Sokotra. In Kersten Schenk, V e g e t d - b d d ~ , 3 ( 5 ) , 25-30.

EXPLANATION O F PLATES 55-59

PLATE

55

Fig. 1. Bare, crescentic dunes overlying stony floor of the southern coastel plain of Naukad. The

absence of vegetation is due to edaphic aridity.

Fig. 2. Sand deposits at Houlaf, northern coast. Aeocia edgezuo7thii forms 8 community here, but is

rere elsewhere.

Fig. 3. Sward of salt-grass,HeZeoch dara, on the beech dun- at Naukad. In the background, the

belt of the sea-lavender,Limonium app. which develops farther inland from the salt-grw.

Fig. 4. Sometimes the vegetation on the southern coastal plain is very sparse. Low crescentic dunes

with a few shrubs of Caotr+ p m a .

PLATE

56

Fig. 5. At the base of the hills the dunes are fixed by a community of woody herbs and ephemerals.

Fig. 6 . Indigofem sp.nov.4ort grass esaociation on the coastal plain a t Hadibo.

Fig. 7. Another woody herb community: the Dactyloctsnium hmMi&Eqlwrbia spiralis association

on the Gobe plain.

Fig. 8. The shrub zone; Croton socotranus--short grass association on Hadibo plain and at Moabbadh.

PLATE

57

Fig. 9. Community of rock plants on the lower s l o p of the Reiged. ( a ) Dendrosicyos sowtram,

( b ) Cisszls subaphyk and (c) Euphorbia ar6uscplla.

Fig. 10. Community of rock plants on the higher s l o p of Reiged. ( a ) Kleinia scottii, ( b ) Ficw

socotrana, (0) Dorstenia gigas, ( d ) BoaweUia sp.

Fig. 11. Rock vegetation on the middle s l o p of the Reiged; the dominantsare succulents and shrubs.

Fig. 12. A grove of &-ma

cinnabari on the s l o p of the Hamadera hill a t Homhil.

PLATE 58

Fig. 13. A typical view of the summit of the limestone plateau, with stunted shrubs (Jatropha unicoetata) and ephemeral%

Fig. 14. Mixed thickets on the lower slopes of the Hagghier.

Fig. 15. Grasslands on the Hsgghier mountains; dominants The&

q u a d r i d & and Hypawhenko

hirta.

Fig. 16. Mixed evergreen thickets in the Hagghier highlands.

PLATE 59

Fig. 17. F k w salkifolko, Cordia sp. and other plauts which together with the date palm form fairly

dense groves along the rivers, which carry water for most of the year.

Fig. 18. Dry watercourse cros~@the Naukad plain. Vegetation is denser, but of the m e composition as on the adjoining plain.

You might also like

- James Gurney - Dinotopia - A Land Apart From Time (SiPDF)Document168 pagesJames Gurney - Dinotopia - A Land Apart From Time (SiPDF)Sergio Mercado Gil98% (54)

- Ingleton Field ReportDocument5 pagesIngleton Field Reportjosh0704No ratings yet

- Bpharm Myleads 2023 09 12 (All)Document202 pagesBpharm Myleads 2023 09 12 (All)nitingudduNo ratings yet

- Geology of Labuan - 1852Document13 pagesGeology of Labuan - 1852Martin LavertyNo ratings yet

- Explanatory Notes On The Perth Geological SheetDocument40 pagesExplanatory Notes On The Perth Geological Sheetscrane@No ratings yet

- Metodichka Part 1 Final Version 1Document49 pagesMetodichka Part 1 Final Version 1Alyona ChernyaevaNo ratings yet

- Stratigraphic ReportDocument3 pagesStratigraphic Reportapi-309272596No ratings yet

- Extract Prehistoric Cultures of The Horn of Africa - ClarkDocument29 pagesExtract Prehistoric Cultures of The Horn of Africa - Clarklolololoolololol999No ratings yet

- Epicor Data DiscoveryDocument3 pagesEpicor Data Discoverygary kraynakNo ratings yet

- Cruise of the Revenue-Steamer Corwin in Alaska and the N.W. Arctic Ocean in 1881: Botanical Notes: Notes and Memoranda: Medical and Anthropological; Botanical; OrnithologicalFrom EverandCruise of the Revenue-Steamer Corwin in Alaska and the N.W. Arctic Ocean in 1881: Botanical Notes: Notes and Memoranda: Medical and Anthropological; Botanical; OrnithologicalNo ratings yet

- Kissling-CharacterPurposeHebridean-1943 (1) - CompressedDocument30 pagesKissling-CharacterPurposeHebridean-1943 (1) - Compressedahmet.uzunNo ratings yet

- FIG (1) Location and Boundaries of PalestineDocument11 pagesFIG (1) Location and Boundaries of PalestineMohammed Mustafa ShaatNo ratings yet

- Southern Nigeria1907Document10 pagesSouthern Nigeria19074zhhmwqb75No ratings yet

- Tidalflat LandformDocument6 pagesTidalflat LandformMaung Maung ThanNo ratings yet

- Geological Field Report of Salt Range and Hazara Range PakistanDocument69 pagesGeological Field Report of Salt Range and Hazara Range PakistanEw HoneyNo ratings yet

- Tsingtao Black BookDocument38 pagesTsingtao Black BookDinko OdakNo ratings yet

- AVNER, Ancient Water Management in The Southern Negev, ARAM 14 (2002)Document19 pagesAVNER, Ancient Water Management in The Southern Negev, ARAM 14 (2002)omnisanctus_newNo ratings yet

- John Haldon - Palgrave Atlas of Byzantine History 1-13 OCRDocument7 pagesJohn Haldon - Palgrave Atlas of Byzantine History 1-13 OCRAnathema Mask100% (1)

- An Introduction To The Study of The Babylonians and AssyriansDocument88 pagesAn Introduction To The Study of The Babylonians and AssyriansAisel OmarovaNo ratings yet

- Hydrogeochemical Assessment of Groundwater in Gal-Mudug Region - SomaliaDocument17 pagesHydrogeochemical Assessment of Groundwater in Gal-Mudug Region - SomaliaSalsabiil water well drillingNo ratings yet

- Sweeting, Marjorie M. The Karstlands of JamaicaDocument18 pagesSweeting, Marjorie M. The Karstlands of JamaicaCae MartinsNo ratings yet

- Sedimentary Facies Distribution PDFDocument18 pagesSedimentary Facies Distribution PDFgeologuitaristNo ratings yet

- Crofting Settlements and Housing in The Outer HebridesDocument14 pagesCrofting Settlements and Housing in The Outer Hebridesahmet.uzunNo ratings yet

- The American Southeast, A Guide To Florida and Adjacent Shores - A Golden Regional Guide (1959)Document168 pagesThe American Southeast, A Guide To Florida and Adjacent Shores - A Golden Regional Guide (1959)Kenneth100% (3)

- Arabia in The Pre-Islamic Period PDFDocument26 pagesArabia in The Pre-Islamic Period PDFRıdvan ÇeliközNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 Abbottabad DistrictDocument18 pagesCHAPTER 1 Abbottabad DistrictTaimur Hyat-KhanNo ratings yet

- Case Study of A Drainage BasinDocument8 pagesCase Study of A Drainage BasinGrace KamauNo ratings yet

- 2 WeatheringDocument31 pages2 WeatheringEfraim HermanNo ratings yet

- History of Waterlooville, John RegerDocument56 pagesHistory of Waterlooville, John RegerAnonymous UgVOzaNo ratings yet