Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beliefs and Practices of Chinese University Teachers in EFL Writing Instruction

Beliefs and Practices of Chinese University Teachers in EFL Writing Instruction

Uploaded by

YNYOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beliefs and Practices of Chinese University Teachers in EFL Writing Instruction

Beliefs and Practices of Chinese University Teachers in EFL Writing Instruction

Uploaded by

YNYCopyright:

Available Formats

Language, Culture and Curriculum, 2013

Vol. 26, No. 2, 128145, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2013.794817

Beliefs and practices of Chinese university teachers in EFL writing

instruction

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Luxin Yang* and Shaofen Gao

National Research Center for Foreign Language Education, Beijing Foreign Studies University,

Beijing, Peoples Republic of China

(Received 8 June 2012; final version received 6 April 2013)

This study examined four experienced teachers beliefs and practices in teaching English

as a foreign language (EFL) writing at a university in China. Multiple sources of data

were collected over two semesters, including class observations, interviews, and

course materials. All the teachers perceived that they integrated product and process

elements of writing in their teaching. However, they varied in their views about the

focus and function of prewriting, multiple drafts, teacher written feedback, peer

review, and the teachers role in students learning to write. Three of the four teachers

showed consistency between their beliefs and practices in teaching writing, while the

remaining ones practices were in some cases consistent with his beliefs and in other

cases contradictory. Variability in beliefs and practices about teaching writing was

related to individuals prior experiences as EFL learners and teachers, their

understanding of students capabilities, self-reflection, and collegial influences. The

development of their beliefs and practices in teaching writing paralleled the

development of L2 writing theories in the West, mirroring the worldwide spread of

English and of professional networks over recent decades. This study indicates that

teachers beliefs and practices need to be explicitly taken into account in designing

and implementing development programmes for L2 writing teachers.

Keywords: L2 writing teaching; EFL teachers; beliefs; practices

Introduction

Numerous theories of teaching second language (L2) writing have appeared in the professional literature over the past four decades (Cumming, 2001; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996;

Hyland, 2003; Matsuda, 2003). Each theory has a distinctive focus, emphasising either

language structures, creative expression, composing processes, content, genres, or contexts

of writing. In the 1950s and 1960s, language teachers often used writing as a vehicle for

language practice. Current-traditional rhetoric was, and in some situations still remains,

one of the main teaching methods, emphasising correct usage, grammar, and rhetorical patterns. In the 1970s, inspired by research and educators analyses, theories about L2 writing

instruction started to shift from a focus on structures of language and of written texts

towards an emphasis on the processes of composing. Theories about the processes of

writing developed in three main strands: the expressive view, the cognitive view, and the

*Corresponding author. Email: yangluxin@bfsu.edu.cn

2013 Taylor & Francis

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

129

social view. The expressive view regards writing as a form of communicating personal

ideas that is progressively learnt, not taught, so rather than focusing narrowly on correct

grammar and usage, writers are encouraged to discover their own ideas while they

compose. The cognitive view regards writing as a, non-linear, exploratory, and generative

process whereby writers discover and reformulate their ideas as they attempt to approximate

meaning (Zamel, 1983, p. 165). From a cognitive view, learning to write focuses on developing an efficient and effective composing process. The social view regards writing as situated acts that occur within particular situations and groups of people, so learning to write is

a process of socialising into an academic or other specialised community. Much discussion

has focused on these different theories and their implications for students L2 learning, but

scant attention has been given to how teachers actually teach, and learn to teach L2 writing

in real classrooms (Hirvela & Belcher, 2007; Leki, Cumming, & Silva, 2008).

There is a glaring gap between theories of writing instruction and actual practices of

classroom teaching (Hedgcock, 2010; Zhu, 2010). Theory is mainly seen to be the work

of scholars and empirical researchers, whereas practice is the work of teachers, many of

whom may deride theory as irrelevant to their classrooms (Clarke, 1994; Hedgcock,

2010). Nonetheless, teachers are one of the most available supports that students can

seek in their process of learning to write. In the context of English as a second language

(ESL), writing abilities in English are recognised as decisive for students in performing academic writing tasks at universities or college and in professional or vocational writing at

work (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996; Leki et al., 2008). In many contexts of English as a

foreign language (EFL) (e.g. China), writing abilities in English are often required not

only at the college and university level but also in secondary schools for various entrance

exams or qualifications. Grabe and Kaplan (1996, p. 6) stated that writing abilities are not

naturally acquired but culturally transmitted in every generation, whether in schools or in

other assisting environments. To meet their writing demands, students definitely need good

writing instruction, for which qualified and experienced writing teachers are necessary. The

present study took up Hirvela and Belchers (2007) call for more research on writing teachers by examining in-depth a sample of experienced EFL teachers beliefs and practices in

teaching L2 writing.

Research on L2 writing teachers

Only a small number of studies have investigated systematically how L2 writing is taught in

actual classrooms and how writing teachers perceive the teaching and learning of L2

writing. Among those existing studies, teachers beliefs have been found to impact directly

on their classroom practices (Burns, 1992) and to determine their reactions to pedagogical

innovations for writing instruction (Shi & Cumming, 1995; Tsui, 2003). In particular,

Cumming (1992) found that experienced ESL teachers systematically structure classroom

activities around students performance of writing, reading, and group discussion tasks.

Certain contextual conditions (e.g. institutional, curricular, or public examinations) may

constrain teachers realisations of their beliefs into practices (Lee, 2003; Tsui, 1996) or

influence teachers theories of L2 writing instruction (Sengupta & Falvey, 1998; Tsui,

2003). In turn, structured or stimulated reflection on their practices may help teachers integrate their learned theories into new or improved practices and to develop more effective

ways of teaching (Farrell, 2006; Sengupta & Xiao, 2002; Tsui, 2003). Moreover, the education of writing teachers may broaden in-service teachers perspectives on teaching writing

and help them to construct new identities as writing teachers (Lee, 2010).

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

130

L. Yang and S. Gao

Studies by Pennington et al. (1997), Cumming (2003), and You (2004) are particularly

relevant to the present study. Pennington et al. (1997) found that many teachers in the Asia

Pacific region took a middle-of-the-road approach to integrating process and product

teaching elements in order to accommodate constraints in their educational contexts.

Cumming (2003) found that experienced writing teachers in a range of different countries

and programme types had similar conceptualisations of ESL/EFL writing curricula. He

attributed this uniformity to the broader contexts in which these teachers worked, involving

the worldwide spread of English and influences of professional networks, conferences, publications, and graduate education in English-speaking countries. You (2004) found that

English writing for non-English majors in a Chinese university tended to be taught with

a current-traditional rhetoric approach, focusing on correct language forms rather than on

helping students to develop their thoughts or writing expertise.

In terms of research methods, Pennington et al. (1997) and Cumming (2003) relied on

survey questionnaires or single-occasion interviews rather than lengthy classroom observations, so their studies did not reveal much about the details of teaching practices or individual teachers beliefs. Similarly, Yous (2004) observational study of college teaching of

English writing provided little in-depth information about teachers of English writing in

China. Further research is needed, therefore, to examine ESL/EFL teachers beliefs and

practices in teaching writing.

Most of the studies reviewed above were conducted in English-dominant contexts. More

research is needed to understand the relatively distinct situations of teaching writing in EFL

contexts. Countries such as China, for example, have enormous numbers of EFL learners. In

2009, about 21 million students attended universities in Mainland China, almost all of whom

were taking some English courses as degree requirements (National Bureau of Statistics of

China, 2010). Each year millions of university students take the College English Test

Band 4 or 6, which has a writing component (Reichelt, 2009; You, 2004). How teachers

teach these students impacts directly on how the latter learn to write and perform in such

tests. Unfortunately, teacher education focused on English writing remains underdeveloped

in China. Many EFL teachers lack knowledge about composition, tending to see themselves

more as teachers of language rather than teachers of writing, as Reichelt (2009) observed in

other EFL contexts. Obviously, teacher education is crucial for effective EFL writing instruction and learning in schools and institutions in China and similar EFL contexts. Knowledge of

experienced EFL writing teachers beliefs and practices, and especially of the development of

their beliefs and practices, is needed to provide insights for the education and professional

development of new entrants. The present study is intended to contribute to this goal by

examining the beliefs and practices of four experienced university EFL writing teachers.

We had three research questions:

What are the beliefs of experienced university teachers concerning the teaching of L2 writing?

What are the practices of experienced university teachers in teaching L2 writing?

What factors contribute to experienced university teachers beliefs and practices in teaching L2

writing?

Context

This study took place at an English department of a major university in China. The writing

programme in the department started in the 1980s, and since that time has been using teaching materials developed by its instructors. The programme consists of three levels of writing

Language, Culture and Curriculum

131

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

courses offered to undergraduate students who are either English majors (96 students per

year) or majors in Journalism and Translation (96 students per year). Specifically, the

first year focuses on paragraph and essay writing of summaries, narrations, descriptions,

and expositions; the second year focuses on argumentation and research-paper writing;

and the third year focuses on writing in particular disciplines. Our study focused on the

instructors who were teaching in the first and second years of the programme.

Participants

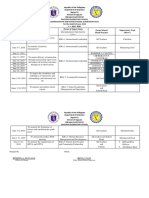

The participants were selected according to their years of teaching at this English department.

Table 1 presents the profiles of each participant in terms of gender, age, years of teaching

English, years of teaching English writing, education background, academic field, TEFL

(teaching English as a foreign language)/TESL (teaching English as a second language)

training, and academic position. The four teachers, who we call Chen, Hong, Dong, and

Liang, collectively had experiences of 512 years of teaching English writing and

948 years of teaching English. At the time of the study, Chen was teaching expository

writing to the first-year English majors, whereas Dong, Hong, and Liang were teaching argumentative writing to the second-year English majors. The participants represent the four generations of writing instructors in this department. So our examination of their beliefs and

practices in teaching EFL writing reflects the historical development of EFL writing instruction in this university through successive hiring of new generations of faculty members.

The four instructors had all received their undergraduate education in China. Chen and

Hong were graduates of the university where they were now employed. Chen had officially

retired more than 10 years earlier but was invited by the programme chair to teach at least

one course each semester so as to mentor young teachers. All the four instructors had

experiences of studying in the USA for periods of one to six years. Chen did a year-long

Masters degree in American literature in the early 1980s in the USA, during which time

she also worked as a teaching assistant (TA) responsible for marking students compositions. Dong studied in the USA for six years, earning his Masters degree in Linguistics

and his doctorate in American literature while working as a writing instructor for local

freshmen. Hong and Liang each had opportunities to study in the USA for one year as visiting scholars in the early 2000s.

The four professors had taught a wide range of other courses besides writing. Chen had

rich experience teaching undergraduates English language courses such as intensive

reading, extensive reading, speaking, and listening. Hong had taught undergraduates intensive reading courses for 10 years before teaching writing courses. Dong and Liang offered

courses on American literature to the senior undergraduates and graduate students. Like

most English teachers in China, they had not received any training in English language

teaching pedagogy before they became university professors.

Data collection

Our data collection consisted of two stages, lasting for five months, starting from March 2008

to June 2008 and then from November 2008 to December 2008. In the first stage, we took

turns observing the four teachers classes. At the second stage, we observed each teacher

for two sessions (one complete unit of teaching) to verify our initial data interpretations. In

total, we observed Chen and Dong for nine sessions (18 hours) each and Hong and Liang

for seven sessions (14 hours) each. These periods of classroom observation deepened our

understanding of the four participants beliefs and practices in teaching writing. As requested

L. Yang and S. Gao

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

132

Table 1.

Profiles of the four writing instructors.

Teacher Gender Age

Years of teaching

English

Years of teaching

writing

Education

background

Chen

Female

71

48

10

MA (USA)

Dong

Male

51

23

12

MA (USA)

PhD (USA)

Hong

Female

40

15

Liang

Male

36

MA (China)

PhD (China)

MA (China)

PhD (China)

TEFL/TESL

training

Academic field

American

literature

Linguistics

American

literature

American study

American study

American

literature

American

literature

Academic position

Limited (as a TA)

Professor

Limited (as a TA)

Professor

No

Associate

professor

Associate

professor

No

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

133

by the participants, we did not video- or audio-record the classes that we observed, but instead

took detailed field notes (i.e. recording the instructional procedures, interactions between

teacher and students, and students activities). Copies of lecture slides were collected with

the instructors permission, helping us to prepare for our interviews. In addition, we talked

to each professor after class to understand certain of their teaching decisions. We also had

two formal interviews with Chen, Dong, and Hong and one interview with Liang, with

each interview lasting from 30 minutes to two hours. The interviews were based on our classroom observations, covering questions about the nature of writing, the role of writing instruction, teaching content and approach, and teacher development. These interviews were first

transcribed verbatim. Later the transcripts were sent to the participants for verification. In

the present article, utterances originally spoken in Chinese have been translated into

English and are presented here in normal font. Utterances of the participants originally in

English are presented in italics. Our own contextual explanations are in brackets.

Data analysis

Our analyses emphasised the identification of key themes through constant comparison and

contrast (Merriam, 1998; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Our initial theme analysis was done

during data collection. Then, after obtaining the complete set of data, we read through

them and refined the themes related to teachers theories of EFL writing instruction across

observation notes, teaching slides, and interview transcripts. The classroom observation

notes were summarised for a macro view of the classroom as a social context in order to identify influences that the settings might have had on the teachers beliefs in teaching writing. We

read the interview transcripts individually to distinguish the main themes. We then compared

our individual thematic analyses and grouped these into larger themes through discussion and

by reference to our research questions. Eventually, we established three main themes concerning the teachers beliefs about: (1) the focus of writing; (2) teaching approach, including prewriting, multiple drafts, teacher feedback, and peer review; and (3) the teachers role in

students learning to write. Three themes concerning the sources of teachers beliefs in teaching writing were also identified: (1) learning from ones experience as a student; (2) learning

from ones classroom teaching; and (3) learning from ones colleagues. To verify our interpretations we then discussed with the four teachers individually their beliefs in teaching writing.

Findings and discussion

The purpose of our study was to examine the four teachers thinking about EFL writing

instruction, rather than to directly look for evidence of the impact of particular practices,

derived from particular beliefs, on students learning. For this reason, we relied primarily

on observations and observation-based interviews to establish our findings. We first

report the four teachers beliefs in teaching L2 writing. Then we present the four teachers

practices in teaching L2 writing. Finally, we trace the sources for the development of the

four teachers beliefs and practices in teaching L2 writing.

Teachers beliefs about teaching L2 writing

The focus in teaching writing

The four professors all stated that they believe writing is a process of thinking, but each

teacher expressed differing perceptions about the focus of teaching writing. Chen indicated

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

134

L. Yang and S. Gao

that writing was a process of understanding truths about life because writing can stimulate

students to think and the purpose of writing is to understand others and be understood by

others. A basic requirement for university student writers was to express themselves

clearly. Compared with her students in the 1950s and 1960s, Chen stated that many students

nowadays were poor in language accuracy and used many Chinglish expressions such as

Life at college is boring, just like a glass of boiled water. Chen considered clarity of

expression as her focus in teaching writing because poor language quality will lead to misunderstanding in writing. These sentiments echo the view of Paula, a participant in

Sengupta and Xiaos (2002) study.

Hong agreed with Chens view of the importance of accuracy in teaching writing, citing

the pervasiveness of language problems in students writing as learners of English. She

doubted the effectiveness of teachers help regarding students use of English, however,

because it depends on both teachers English proficiency and students sensitivity to

English. Hong stressed that writing is to express thinking clearly in words and thus

thinking clearly is the first step for writing. Therefore, her focus in teaching was to

help students notice and solve logical problems in their writing.

Like Hong, Dong perceived that students writing problems mainly came from poor

thinking abilities. He stated that, writing is to express ones thinking and writing is a

process of creative thinking and critical thinking. He argued that the primary focus of

teaching writing was not to teach techniques of using language and rhetorical patterns,

but to train students to think creatively and critically. He said that, a composition

without any grammatical mistakes is not good writing if it has no interesting ideas.

Liang agreed with Dong that training students thinking abilities should be the focus of

teaching writing. He thought that if a student can think both creatively and critically, his

writing must be excellent. Liang perceived that few students could have creative ideas and

strong English competence simultaneously. Thus, the challenge was to balance a focus on

language and a focus on ideas in teaching. In particular, Liang stressed that writing needs

emotional involvement in addition to language and creative ideas. That is, if writing cannot

touch readers, despite correct grammar and good language, it is meaningless.

Approach to teaching writing

The four teachers believed that written products and processes should be integrated rather

than separated in teaching, and sufficient reading input was essential for learning to write.

They all regarded their teaching approaches as a mixture of product and process orientations

to writing. However, each professor had different emphases in conceptualising their teaching methods. Chen stressed the importance of the quality of written products in teaching.

She argued that, No matter which approach is used, the written product is expected.

Without a written product, teaching writing is meaningless. Liang valued a balance

between products and processes in teaching writing, because writing needs both product

and process. In contrast, Hong and Dong strongly believed that writing instruction

should first focus on the process of writing, particularly to help students with developing

ideas at the prewriting stage, and then should focus on language use and rhetorical patterns

at the revision stage.

The professors all considered that prewriting activities (e.g. brainstorming) were crucial

for students to prepare for writing, but each teacher had different views about the purposes

of students engagement. Chen stated that prewriting can help students think clearly.

Hong indicated that prewriting can help students find a proper focus. Liang observed

that, students should spend more time in prewriting, such as searching related information,

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

135

thinking and writing an outline. Dong claimed that prewriting was an important stage for

students if they are to develop creative thinking abilities, and therefore, teachers at this point

should be less judgemental and encourage students to articulate their ideas without concerns

for accuracy.

The four teachers all asked their students to do multiple drafts of their compositions, as

required by programme policies. But the teachers each had different attitudes about the usefulness of multiple drafts. Chen doubted the benefits of multiple drafts, observing that multiple drafts made students depend excessively on teachers feedback for revisions,

especially in regards to language use. Chen argued that students made concerted efforts

to use language and rhetorical structures properly if they did not have another chance to

change their grades. Liang considered it optimal to give students his feedback on ideas

and outlines at the prewriting stage when students were collecting information, thinking,

and outlining for a writing topic. He doubted the necessity of the requirement for multiple

drafts given his students motivation for developing writing expertise, though he observed

that the language use in a composition could be improved after several rounds of revisions.

Dong perceived that two drafts were sufficient for his university students to change their

ideas or content substantially in their writing, noting that more drafts did not make much

difference because students language proficiency would not improve greatly over a

short period of time. In contrast, Hong was highly positive about students writing multiple

drafts because good writing is the result of multiple revisions. She stated that multiple

drafts provided students with opportunities to polish their language and to clarify their

thinking under a teachers guidance. She emphasised that teachers guidance was crucial

for students to benefit from multiple drafts.

Moreover, the four teachers differed in their beliefs about the focus and functions of teachers written feedback. Chen stated that teachers should focus on content and structure to

see whether students meet teachers requirements (e.g. in terms of topic selection, rhetorical

patterns) in the first draft of a composition, but for the second draft, teachers feedback

should focus on the use of language, especially those expressions which cause misunderstanding or are inappropriately used. In contrast, Hong believed that teachers feedback

should focus on logic and coherence because students could easily handle typos and grammatical errors themselves. Both Chen and Hong viewed providing written feedback as a

teachers responsibility, though it was an enormous consumption of time and energy, and

they felt rewarded when their students made improvements in writing as a result of their

written feedback:

I spend most of my time commenting on students writing. Sometimes I spent one afternoon

reading one essay, thinking how to help this student improve his writing without hurting

him. It is time consuming to write down my feedback. But whenever I see my students

express themselves clearly with the support of my feedback, I really feel rewarded. (Chen)

Compared with peer review, students highly valued teacher feedback. I think its a teachers

responsibility to respond to students writing carefully. Commenting on students writing is

a process of dialoguing with students and exploring their thinking. I feel happy when I see

my students make progress in writing. (Hong)

Dong consistently expressed the view that he focused on idea development in his feedback rather than on grammar errors. Like Hong, he perceived that students could self-correct

their grammar errors. Thus, he usually underlined students grammar errors, believing that

students will have deep impressions about that grammar use if they correct their own

grammar errors and they need this process of learning to use grammar properly.

136

L. Yang and S. Gao

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Liang indicated that he had a dilemma. He spent a lot of time reading and commenting on students writing each week, but he did not see his students writing get better

with his corrections and comments. He stressed that writing cannot be taught and students should have the desire of I want to write well or I want to be creative. Liang

doubted the usefulness of telling students about formulaic rules because, to write well,

students need to have life experience, read good writing, have a memory of good

writing, and think. Despite his dilemma, like the participant Peter in Sengupta and

Xiaos (2002) study, Liang often focused on accuracy in his written feedback, for

which he explained:

The content is constrained by their personal experiences, which is difficult to improve within a

short time, even with teacher feedback. In contrast, language correction is more useful to students and can bring immediate effect to their next writing.

Furthermore, the four teachers had differing views about the usefulness of peer review.

Chen and Hong considered that peer review could raise students awareness of audience

and nurture their critical thinking abilities:

In the process of identifying the problems in their peers essays, they could reflect on their own

writing. And in responding to their peers comments, they need to decide to accept or refuse

them, which exercises their critical thinking. (Chen)

Peer evaluation is complementary to teacher feedback. Peer review engages students in the

process of self-evaluation. This participation allows students to exercise their judgment and

raise language awareness. It is also a process of training their consciousness of audience and

critical thinking abilities. (Hong)

In contrast, Dong and Liang indicated that students might not benefit from peer review,

because some students tended to be reserved in their opinions or comments about other students writing. Dong and Liang held that peer review could be beneficial to students (as

writers and readers) only when they took peer review seriously and were willing to give

their opinions candidly to each other:

Some capable students can do peer review very well, but they are not devoted. American students may express frankly what they think, so it is easy to carry on peer discussions, whereas

our Chinese students tend to reserve their opinions during team work. (Dong)

If students regard peer review just as an assignment, peer review is then just a task. As a result,

little difference exists between the first draft and the revised draft. Most of the time I find peer

review doesnt achieve its purpose. (Liang)

The teachers role in students learning to write

The four teachers also had diverse beliefs about the teachers role in students learning to

write. Chen stressed that teachers needed to give students guidance and to require them

to follow rules in English at the early stages:

In teaching expository writing, I ask students to have a thesis statement. Students then question

why they have to do this. They want more freedom, but they dont know the differences in

writing between Chinese and English. I tell them you must do it this way. Once you

develop writing competence to a certain level, you could be a little freer in how to write in

English. I have to push them to make efforts to meet my requirements.

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

137

Chen believed that students benefit from learning language forms because these forms enable

them to generate and express ideas when successfully appropriated. Her belief echoes

Devitts (1997) argument that, Only when we understand genres as both constraint and

choice, both regularity and chaos, both inhibiting and enabling will we be able to help students use the power of genres critically and effectively (p. 54; cited in Dean, 2000, p. 54).

Hong viewed the development of students writing competence as mainly dependent on

students own practices and intentions. To write well, students need to have formed good

writing habits such as considering audience and purpose. Before becoming independent

writers, students need a teachers guidance and support to get rid of bad writing habits

they had formed in high school and to offer them more opportunities to change their previous perceptions about writing.

Dong used the metaphor coach to describe his role in writing instruction. He emphasised that students should take the responsibility for their own learning, so teachers need to

set up tasks to stretch students potential. He believed that students have the potential to

learn well and will learn from writing and making mistakes. Similarly, Liang valued students autonomy more than formal classroom instruction. Advocating the view that writing

ability is not acquired through teaching but is learnt from abundant reading, Liang argued

that teachers need to encourage students to read, think, and write as well as to give

responses at the stage of prewriting.

Teachers practices in teaching L2 writing

The classroom observations revealed that Chen, Hong, and Dongs beliefs were consistent

with their teaching practices, whereas Liangs belief was not closely matched with his teaching practice. Chen, in line with her belief that language accuracy and basic writing techniques

were crucial to students development of writing competence, gave more attention to rhetorical conventions, writing techniques, and error analyses in her teaching. Chen organised her

classroom teaching based on the in-house textbook. Each unit focused on a specific writing

technique, which was completed within four class periods with 50 minutes per period. In the

first two class periods, Chen spent most of the time introducing rhetorical rules and writing

techniques (e.g. how to write a topic sentence) through analysing model essays and exercises.

Towards the end of the class, she usually gave students several topic choices for their writing

assignment and asked them to submit the first draft prior to the next class. In the latter two

class periods, Chen mainly discussed students drafts. Primarily, Chen showed the class

their errors she found in their drafts and offered her revised versions. Overall, Chens classroom teaching was teacher-dominated, well organised, and informative.

Hong organised her classroom teaching based on the in-house textbook, supplemented

with an American college composition textbook. Different from Chen, Hong spent little

time discussing the rhetorical rules and writing techniques covered in the in-house textbook, believing that students could read themselves. Instead, she briefly went through

the key points in the textbook and spent most of the class time discussing model essays.

Commenting on her practice, Hong said:

Students expect the teacher to tell them explicitly what good writing is, and they expect the

teacher to give them model essays to follow. In the process of analysing the model essays, students get to know the teachers requirements on their writing.

Unlike Chen, Hong actively involved students in class discussions on model essays and

students writing by questions and comments. Viewing logical issues as the major problems

138

L. Yang and S. Gao

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

in student writing, Hong spent plenty of time in class analysing students writing and guided

them to identify their logical fallacies.

Differently from Chen and Hong, Dong used his own teaching materials covering the

major themes of the in-house textbook but emphasising the training of students thinking

abilities. Dong encouraged students to actively participate in class discussions, which he

viewed as important for his classroom teaching:

New ideas will not occur without discussion. Discussions can make my teaching easier and

make me feel comfortable in class. If there is no communication, it will be difficult for me

to teach because I can only imagine the possible problems they have rather than know

exactly what they have difficulty with.

Dong seldom stayed behind the teachers desk in class; he kept on stepping forth and back

around the classroom with a very rich body language. He vigorously responded to students

questions and comments in class discussions and guided students to perceive the same issue

from different perspectives.

Similarly to Dong, Liang used his self-selected materials for his teaching in line with the

themes of the in-house textbook. He put these materials in his PowerPoint (PPT) slides. His

PPT courseware was tremendously rich and involved various aspects of each theme. For

example, when coming to the topic beauty, he demonstrated differing perceptions of

beauty from the ancient to the modern, illustrated with vivid pictures and poems in order

to broaden his students vision. Unlike Chen, Hong, and Dong, Liangs writing teaching

practices were both contradictory to and consistent with his beliefs. On the one hand,

Liang did introduce rhetorical rules and techniques for English writing and conduct error

analysis as other writing teachers did, though he believed that students could not develop

their writing abilities simply through his teaching. On the other hand, he was interested

in sharing his views about life with his students, as he believed that good writing came

from rich life experiences. However, in presenting his slides concerning art, poems and education, he appeared to be engaged in lecturing without much communication with his students. He arranged his students to do group discussions, but he stood behind or near the

teachers desk, reading his materials, rather than walking around the classroom and

responding to his students.

The four teachers varied in practising the requirement of multiple drafts, depending on

their beliefs in the usefulness of multiple drafts. Chen, Dong, and Liang showed less interest

in students drafts beyond the second one, whereas Hong was positive about students efforts

towards multiple drafts. Chen gave students detailed written comments on the first draft,

which she scored for her own reference. Students were required to do peer review on their

second draft. Some students made revision according to peer feedback whereas some did

not. Chen scored and gave written feedback to their second draft or revised second draft as

well as offered her comments on peer evaluation. It was up to students to do the final

draft, but Chen did not award students higher scores for their further drafts.

Differently from Chen, Hong required students to do peer review on both their first

and second drafts following her checklist. Hong did not score the first draft but the

second one. She encouraged multiple drafts and gave higher scores to the third or even

further draft depending on the quality of revision. She also held writing conferences regularly in her spare time with those students who may have unresolved problems or confusions about her instruction or their writing. Like the teacher in Diab (2005), Hong

regarded conferences and peer reviews as useful feedback methods, supplementary to

teacher written feedback.

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

139

Similarly to Hong, Dong asked students to do peer review on their first draft with his

checklist. He scored and provided his feedback to students first revised draft, second

draft, and peer evaluation. In contrast, Liang occasionally asked students to do peer

review and usually responded to students first drafts with the focus on language use. He

scored but rarely offered feedback to students second drafts, because he did not see students

make substantial improvement in terms of language and content between the two drafts.

In short, Chen, Hong, and Dong all had good control over the classroom activities and

were highly devoted to classroom teaching. Our observations show that Chen was more

director-oriented and Hong and Dong played mixed roles in their teaching: on the one

hand, Hong and Dong offered their forceful guidance to students; on the other hand,

they tried to create more opportunities to communicate with students and facilitate them

in their process of writing. In contrast, Liang seemed to be detached from his students.

In spite of his belief that teachers should play a role of stimulating students interest in

writing and developing their competence in independent learning, Liang appeared to let students learn to swim by swimming themselves.

Development of teachers beliefs and practices in teaching L2 writing

The four teachers learned to teach EFL writing, and thus formed their beliefs and practices

of teaching writing, primarily through their experiences as EFL learners and teachers, their

understanding of students capabilities, and collegial influences. Coincidentally, the development of each of their beliefs in writing instruction was in parallel with the historical

development of theories of L2 writing in the West, related to their ages and periods of university employment. In particular, Chens beliefs displayed principles of current-traditional

rhetoric; Dongs and Liangs beliefs were close to the expressive view of process writing;

and Hongs beliefs combined current-traditional rhetoric with views of writing as a cognitive process.

Chen: the current-traditional rhetoric view

Chen began to teach English at the university in the late 1950s, which was also the popular

period for product-oriented pedagogy in the West. She recalled that English writing at that

time was done to introduce China to the world. With this purpose in mind, accuracy and

appropriateness were highly valued as indicators of a persons education among colleagues.

Moreover, due to the shortage of pedagogical materials, teachers at that time emphasised

imitation and repetition in English learning, including learning to write. Writing was integrated into reading courses to help students read and grasp vocabulary and grammar. She

learned to teach English writing by observing the head teachers classes and being observed

herself by the head teacher. Chen said that the teaching method came from their instincts

and experiences of learning to write in their first language (Chinese) at that time.

Another influence was native-English-speaking teachers with whom Chen worked. In

the late 1970s, an American teacher drew her attention to the Chinglish expressions in the

student compositions she collected for the in-house writing materials. The 1970s were the

time of promoting the process-oriented writing instruction and criticising the productoriented writing instruction in the West. Thus, it is not surprising that this teacher introduced

Chen to distinctions between product and process writing pedagogy. In the early 1980s,

another American teacher made Chen and her colleagues aware of how to teach writing systematically by organising lessons according to genres or rhetorical patterns:

140

L. Yang and S. Gao

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Before this American teacher worked with us, we taught English writing following the ways of

teaching Chinese writing. We never taught students about a topic sentence, rhetorical patterns,

and so on. The American teacher and six teachers in our department formed a group of writing

teachers. We all wrote about the topics which our students were going to write about, and then

we met and discussed our own writing. He gave us his comments and graded our writing as well.

The requirement for Chen and her colleagues to write themselves before they asked their

students to write helped Chen to understand the needs and problems students might encounter in writing (cf. Casanave, 2004) and to realise that using rhetorical patterns can structure

the process of expressing ideas readily in English (cf. Dean, 2000).

The third influence was Chens experience studying at an American university in the

mid-1980s. Working as a TA for writing courses during that time, Chen noticed that accuracy was an important criterion for evaluating students writing. This experience reinforced

her beliefs about the importance of accuracy in English composition:

As a TA, I didnt need to correct errors in student writing, but I needed to indicate the type of

error such as agreement or tense In the training session for TAs, a run-on sentence was considered a serious writing problem. Accuracy was quite important. Poor control of language in

writing makes one look poorly educated.

Chens attention to accuracy was even further strengthened by her observations of inappropriate uses of English in students writing, even though many students could get their

intended meanings across. With these three primary influences, Chen was oriented to the

current-traditional rhetorical view of teaching writing, complemented by some elements

of process writing. That is, she required students to use formulaic patterns in their

writing while attending to the processes of composing such as prewriting, multiple

drafts, teachers feedback, and peer reviews.

Dong and Liang: the expressive view

Dong and Liang perceived that teachers should encourage students to discover their own

ideas at the prewriting stage and that writing is learnt rather than taught, echoing principles

of the expressive view of writing. Dong firmly believed that good thinking is the foundation of producing good writing. He identified two primary sources for his view of

writing. First, his view came from his teaching experiences in the USA in the early

1990s, when the process approach to teaching writing was prevalent in many American universities. Basically, Dong learned to teach writing by teaching as he had never taught

writing before studying abroad:

I attended a TA course on teaching writing when I studied at the USA. We were encouraged to use

the process writing approach in our teaching. Then I had to rely on myself in classroom teaching as

I didnt have a mentor. The whole writing course focused on argumentation and logical fallacies.

Critical thinking was an important ability that students needed to grasp in this writing course.

Second, after returning to China in the mid-1990s, Dong observed that lack of ideas was the

main problem in Chinese students writing, which he attributed to students thinking abilities. Thus he put a special emphasis on finding a way of training students creative and

critical thinking abilities in his teaching.

Unlike Dong, Liang attributed his beliefs about writing instruction to his own learning

experiences as a student. Liang said that one of the professors in his masters programme

had a great influence on him:

Language, Culture and Curriculum

141

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

When I was in the MA program, one of my professors asked us to read one book each week. He

set a good example for us. He said to us, Every day I read one book and translate one poem

either from Chinese into English or vice versa. Now I ask you [students] to read one book per

week. I think you can do it. He required us to read carefully because he would ask any sort of

question regarding the book in class. I did as he required. After a year, I felt I made great

improvements in my English.

This experience taught Liang that a teachers responsibility is to guide students learning,

inspiring students to explore further themselves. Students benefit more from extensive

reading than from classroom instruction on the use of formulaic language or rhetorical patterns. However, Liang admitted that he did not realise his beliefs in his practices. He was

uncertain about how to make his teaching interesting, finding it difficult to design tasks

and organise students in discussions. Liang attributed his ineffective teaching to his prejudice towards linguistics and his few reflections on his teaching:

I always consider linguistics useless as it is quite away from classroom teaching. I dont know how

to make my students accept my views, probably because I dont know teaching methodology.

Also, I rarely reflect on my teaching. When the class is over, I feel Ive done my teaching job.

Hong: a mixture of product- and process-oriented writing instruction

Hong perceived that she mixed product and process pedagogy in her teaching of writing. On

the one hand, she followed the arrangement of genres (e.g. narration, description, exposition,

and argumentation) and of rhetorical patterns (e.g. exemplification, classification, definition,

comparison, and contrast) that appeared in the in-house textbooks. On the other hand, Hong

followed process-oriented methods in her teaching, starting with explanation of formulaic

patterns and prewriting, then first drafts, followed by peer evaluation and teacher feedback,

and then second drafts. Hong identified three primary influences in developing her approach

to teaching writing: her teachers, her colleagues, and her own reflection. Hongs initial

approach to teaching writing, particularly of formulaic patterns, came from her own apprenticeship in observing Chens teaching. Chen was Hongs writing teacher during her undergraduate studies and then Hongs mentor when she started teaching.

Hong learned the terms process writing and critical thinking from her colleague

Dong in their group lesson-planning meetings. But reflecting on her learning experience,

Hong observed that elements of process writing were actually embedded in the approaches

to teaching in this department: students were often told to think clearly and make an outline

before writing. The concept of composing processes clarified Hongs understanding of the

nature of writing and gave her the meta-language to explain to students how to write.

Moreover, Hongs ongoing reflections about her own teaching prompted her to refine

the efficiency and effectiveness of her methods for helping her students:

Generally speaking, our students are highly proficient in English. I often wonder how to help

them make great progress in their university studies. Writing is the weakest skill compared to

their speaking, listening, and reading abilities Sometimes, I am not satisfied with my teaching. After class, I ask myself, Why do my students have so many questions about this issue?

What should I do for the next class?

Conclusion and implications

This study examined four experienced Chinese EFL teachers beliefs and practices in teaching writing and identified the primary sources for the development of their beliefs and

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

142

L. Yang and S. Gao

practices. Like the teachers in Shi and Cumming (1995), the present instructors each conceptualised their work differently even though they taught in the same programme and had

similar educational backgrounds. The variability in their conceptualisations related to their

theories of learning, as described in van Liers (1996) theory of practice. Chen considered

that students linguistic knowledge determined the quality of their EFL writing, supporting

Schoonen, Snellings, Stevenson, and van Gelderens (2009) research findings about the significance of linguistic knowledge in foreign language writing. Chen perceived that students

needed to follow formulaic patterns under a teachers guidance before they became competent writers. In contrast, Hong, Dong, and Liang perceived that students thinking was the

underlying force which made their writing clear and meaningful because they assumed that

their students already had a reasonably good command of English. These three thus took up

more process-oriented pedagogy in their teaching even though they focused differently on

training students thinking abilities (Dong), awareness of audiences for their writing

(Hong), and reading extensively (Liang).

In another sense, Chen and Hong were similar in their focus on the moral values of

teaching, particularly responsibility and devotion. Chen and Liang attended more to

language use in their teacher feedback compared to Dong and Hong. Dong and Liang considered students autonomy to be crucial in the success of their learning to write. In sum,

like the teachers in Farrell (2006), Pennington et al. (1997), and Shi and Cumming

(1995), these four teachers took a blended approach, occupying a kind of middle ground

between product- and process-oriented extremes according to their understanding of students needs and their beliefs about learning. The four teachers could also be regarded as

practitioners of post-process pedagogy (Matsuda, 2003) because they took the elements

important to their teaching from principles of both product- and process-oriented writing

pedagogy.

Our study also showed that the four teachers development of their beliefs and practices

in teaching writing related to the historical development of L2 writing theories, even though

the professors had little formal training in the teaching of writing, as is the case with many

L2 writing teachers in other contexts (Lee, 2010; Reichelt, 2009). This coincidence of personal and historical trends might be related to the international spread of English and the

influences of professional networks and cross-cultural exchanges (Cumming, 2003; Pennington et al., 1997). Direct contact with American colleagues exposed Chen and Dong

to current thinking and practices for teaching L2 writing in the West in the late 1970s,

1980s, and 1990s. Chen and Dong then passed on their understanding of teaching L2

writing to the next generation (here Hong and Liang) through regular group lesson-planning

meetings and mentorship. In these ways, writing teachers in China and other EFL contexts

may be consolidating their practices around, a common basis of pedagogical or content

knowledge unique to second language writing instruction (Shi & Cumming, 1995, p. 104).

The four professors experiences of EFL learning and teaching also significantly shaped

their beliefs and practices in teaching writing and may continue to influence them throughout their careers. As in previous, related studies (Burns, 1992; Sengupta & Xiao, 2002; Shi

& Cumming, 1995), the present study points to the importance of valuing teachers beliefs

because teachers beliefs tend to have a personal significance which differs from prescribed

models of educational theory (Cumming, 1989, p. 47) and lie at the heart of teaching and

learning (Burns, 1992, p. 64). From this perspective, one sensible approach to the development of writing teachers would be to ground the curriculum in their beliefs. It is crucial

that teachers would have an opportunity to bring their own experiences into professional

development activities, as teachers are in a strong position to judge the relevance and transferability of researchers pedagogical suggestions (Belcher, 2007, p. 398). Such an

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

143

approach can promote teachers further awareness and reflection on their beliefs and practices, helping teachers to see the relevance of writing research to their own practices. As

Ortega (2009, p. 249) rightly put it, a blend of realism and idealism is our best hope to

deliver successful L2 writing instruction across EFL contexts.

The four professors paid attention to both product- and process-orientations in their

teaching of writing because they considered both orientations integral to the real needs

and abilities of their students. These conceptual orientations may be of particular value

for helping novice writing teachers identify the aspects of their students writing they

should focus on. Whether in ESL or EFL teaching contexts, educators can expect to

address issues related to the focus of writing instruction (on language or ideas development)

and on writing processes (e.g. prewriting, multiple drafts, teachers feedback, and peer feedback). Novice teachers can relate their knowledge and expertise to these issues in designing

and providing instruction with, the orientations most appropriate for particular curriculum

contexts, student groups, and individual teaching styles or preferences (Cumming, 2003,

p. 87).

Teaching is not only intellectual in nature, but necessarily involves a moral dimension

a point not captured in much other research on the teaching of writing or other aspects of

language education, as Johnston (2003) has observed. In the present study, Chen and Hong

showed their dedication to their teaching by spending long periods reading and commenting

on students writing because they believed that teachers devotion and engagement can

influence students attitudes towards efforts in writing. Indeed, a teachers willingness to

reflect, and to find alternative ways to make teaching effective, depends critically on the

extent of their dedication to their teaching. Moral dimensions of responsibility and commitment play a decisive role in teaching practices, as morality is integral to the whole process

of teaching and learning (Wylie, 2005, p. 16) and learning requires a personal relationship like pastoral care (Wilson, 1997, p. 5). Teacher education and development cannot

afford to miss this fundamental point, though further research is needed to examine precisely how morals and values actually influence the teaching and learning of L2 writing.

Our study revealed how certain critical incidents shaped the four teachers beliefs and

practices of teaching EFL writing, but we could not trace the professors actual processes of

learning to teach writing, given the essentially cross-sectional (in four teachers of different

ages who had already developed their experienced abilities) rather than longitudinal design

of our inquiry. Longitudinal research is needed to substantiate our understanding of how

writing teachers develop and how they implement their beliefs in classroom teaching.

Special attention needs to be given to the role of reflection and collegial support in professional development. Teaching writing is a decision-rich, intellectual, social, and moral

enterprise, but above all it is an individual and highly personal undertaking (Clarke,

1994). Helping writing teachers engage with and challenge their beliefs and bring improvement to their practices through ongoing critical reflection should be the core concern of education on writing teachers.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this paper was granted by the Project Sponsored by the Scientific Research

Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars, State Education Ministry of China

(#20071108) to the first author. We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Alister

Cumming and Ling Shi for their precious comments and suggestions on the earlier versions of this

article. We are also grateful to the editor and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments

on the earlier version of the paper. Our appreciation also goes to our participants for their willingness

to share their time and insights with us.

144

L. Yang and S. Gao

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

References

Belcher, D. (2007). A bridge too far? TESOL Quarterly, 41, 396399.

Burns, A. (1992). Teacher beliefs and their influence on classroom practice. Prospect, 7(3), 5666.

Casanave, C. P. (2004). Controversies in second language writing: Dilemmas and decisions in

research and instruction. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Clarke, M. A. (1994). The dysfunctions of the theory/practice discourse. TESOL Quarterly, 28, 926.

Cumming, A. (1989). Student teachers conceptions of curriculum: Towards an understanding of

language teacher development. TESL Canada Journal, 7, 3351.

Cumming, A. (1992). Instructional routines in ESL composition teaching: A case study of three teachers. Journal of Second Language Writing, 1, 1735.

Cumming, A. (2001). Learning to write in a second language: Two decades of research. In

R. M. Manchon (Ed.), International Journal of English Studies, Special Issue, 1(2), 123.

Cumming, A. (2003). Experienced ESL/EFL writing instructors conceptualizations of their teaching:

Curriculum options and implications. In B. Kroll (Ed.), Exploring dynamics of second language

writing (pp. 7192). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dean, D. M. (2000). Muddying boundaries: Mixing genres with five paragraphs. English Journal,

90(1), 5356.

Devitt, A. J. (1997). Genre as language standard. In W. Bishop & H. Ostrom (Eds.), Genre and

writing: Issues, arguments, alternatives (pp. 4555). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Diab, R. L. (2005). Teachers and students beliefs about responding to ESL writing: A case study.

TESL Canada Journal, 23(1), 2843.

Farrell, T. S. C. (2006). Reflective practice in action: A case study of a writing teachers reflections on

practice. TESL Canada Journal, 23(2), 7790.

Grabe, W., & Kaplan, R. (1996). Theory and practice of writing. New York, NY: Longman.

Hedgcock, J. (2010). Theory-and-practice and other questionable dualisms in L2 writing. In T. Silva

& P. K. Matsuda (Eds.), Practicing theory in second language writing (pp. 229244). West

Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Hirvela, A., & Belcher, D. (2007). Writing scholars as teacher educators: Exploring writing teacher

education. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16, 125128.

Hyland, K. (2003). Second language writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, B. (2003). Values in English language teaching. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Associates.

Lee, I. (2003). L2 writing teachers perspectives, practices and problems regarding error feedback.

Assessing Writing, 8, 216237.

Lee, I. (2010). Writing teacher education and teacher learning: Testimonies of four EFL teachers.

Journal of Second Language Writing, 19, 143157.

Leki, I., Cumming, A., & Silva, T. (2008). A synthesis of research on second language writing in

English. Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Matsuda, P. K. (2003). Processes and post-processes: A discursive history. Journal of Second

Language Writing, 12, 6583.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2010). Zhongguo tongji nianjian-2010 [China Statistical Year

Book-2010]. Beijing: China Statistics Press.

Ortega, L. (2009). Studying writing across EFL contexts: Looking back and moving forward. In

R. M. Manchn (Ed.), Writing in foreign language contexts: Learning, teaching, and

research (pp. 232255). Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Pennington, M., Costa, V., So, S., Shing, J., Hirose, K., & Niedzielski, K. (1997). The teaching of

English-as-a-second-language writing in the AsiaPacific region: A cross-country comparison.

RELC Journal, 28, 120143.

Reichelt, M. (2009). A critical evaluation of writing teaching programmes in different foreign

language settings. In R. M. Manchn (Ed.), Writing in foreign language contexts: Learning,

teaching, and research (pp. 183206). Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Schoonen, R., Snellings, P., Stevenson, M., & van Gelderen, A. (2009). Towards a blueprint of the

foreign language writer: The linguistic and cognitive demands of foreign language writing. In

R. M. Manchn (Ed.), Writing in foreign language contexts: Learning, teaching, and research

(pp. 77101). Buffalo, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Downloaded by [University of Colorado at Boulder Libraries] at 07:15 02 January 2015

Language, Culture and Curriculum

145

Sengupta, S., & Falvey, P. (1998). The role of the teaching context in Hong Kong English teachers

perceptions of L2 writing pedagogy. Evaluation and Research in Education, 12(2), 7295.

Sengupta, S., & Xiao, M. K. (2002). The contextual reshaping of beliefs about L2 writing: Three teachers practical process of theory construction. TESL-EJ, 6(1). Retrieved from http://www.tesl-ej.

org/wordpress/issues/volume6/ej21/ej21a1/

Shi, L., & Cumming, A. (1995). Teachers conceptions of second language writing instruction: Five

case studies. Journal of Second Language Writing, 4, 87111.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tsui, A. B. M. (1996). Learning how to teach ESL writing. In D. Freeman & J. Richards (Eds.),

Teacher learning in language teaching (pp. 97123). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsui, A. B. M. (2003). Understanding expertise in teaching: Case studies of second language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Lier, L. (1996). Interaction in the language curriculum: Awareness, autonomy and authenticity.

London: Longman.

Wilson, J. (1997). Caring for children: Some long-term issues. Journal of Pastoral Care in Education,

15(4), 47.

Wylie, K. (2005). The moral dimension of personal and social education. Journal of Pastoral Care in

Education, 23(3), 1218.

You, X. (2004). The choice made from no choice: English writing instruction in a Chinese university. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13, 97110.

Zamel, V. (1983). The composing processes of advanced ESL students: Six case-studies. TESOL

Quarterly, 17, 165187.

Zhu, W. (2010). Theory and practice in second language writing: How and where do they meet? In

T. Silva & P. Matsuda (Eds.), Practicing theory in second language writing (pp. 209228). West

Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

You might also like

- Education of Psychology - Windows On ClassroomsDocument39 pagesEducation of Psychology - Windows On ClassroomsPJ Gape40% (5)

- MONTHLY iNSTRUCTIONAL sUPERVISORY PLANDocument14 pagesMONTHLY iNSTRUCTIONAL sUPERVISORY PLANROLANDO CABUTAJE100% (19)

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Genre Approach PDFDocument58 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Genre Approach PDFLee Ming Yeo100% (3)

- Anne Sliwka - Alternative EducationDocument14 pagesAnne Sliwka - Alternative EducationTheKidLocoNo ratings yet

- Teaching English in The 21st CenturyDocument8 pagesTeaching English in The 21st CenturyVcra GenevieveNo ratings yet

- Using An Analytical Rubric To Improve The Writing of EFL College StudentsDocument38 pagesUsing An Analytical Rubric To Improve The Writing of EFL College StudentssamNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Reasoning in EFLESL Teaching Revisiting The Importance of Teaching Lesson PlanningDocument18 pagesPedagogical Reasoning in EFLESL Teaching Revisiting The Importance of Teaching Lesson PlanninggretayuanNo ratings yet

- 52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Document19 pages52 Bài Scaffolding 10.1515_iral-2023-0125Ngọc OanhNo ratings yet

- ELT - Volume 9 - Issue 20 - Pages 109-134Document26 pagesELT - Volume 9 - Issue 20 - Pages 109-134Triều ĐỗNo ratings yet

- EFL Learner and Teacher Beliefs about Grammar Learning in KoreaDocument19 pagesEFL Learner and Teacher Beliefs about Grammar Learning in Koreadmri12196No ratings yet

- 06 AssessmentDocument9 pages06 Assessmentwosenyelesh adaneNo ratings yet

- BL-So & Lee 2013 A CASE STUDY ON THE EFFECTS OF AN L2 WRITING INSTRUCTIONAL MODEL FOR BLENDED LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATIONDocument10 pagesBL-So & Lee 2013 A CASE STUDY ON THE EFFECTS OF AN L2 WRITING INSTRUCTIONAL MODEL FOR BLENDED LEARNING IN HIGHER EDUCATIONEla NurhayatiNo ratings yet

- ILT Volume 7 Issue 2 Page 1-28Document28 pagesILT Volume 7 Issue 2 Page 1-28Reyhane MoradiNo ratings yet

- Resumenes de ArticulosDocument101 pagesResumenes de ArticulosSandra LilianaNo ratings yet

- Enhancing Iranian EFL Learners' Descriptive Writing Skill Through Genre-Based Instruction and Metalinguistic Feedback IRANDocument30 pagesEnhancing Iranian EFL Learners' Descriptive Writing Skill Through Genre-Based Instruction and Metalinguistic Feedback IRANRaidhríNo ratings yet

- Grammar Ethiopia 30Document22 pagesGrammar Ethiopia 30miki hideki100% (1)

- Pronunciation Pedagogy in English As A Foreign Language Teacher Education Programs in VietnamDocument17 pagesPronunciation Pedagogy in English As A Foreign Language Teacher Education Programs in Vietnamlimili1996No ratings yet

- TEACHERS' PERCEPTIONS - Nghia Trung PhamDocument19 pagesTEACHERS' PERCEPTIONS - Nghia Trung PhamNhi Nguyen PhuongNo ratings yet

- Exploring Teachers' Grammar Teaching Practices in EFL Classrooms Grade 9 in FocusDocument17 pagesExploring Teachers' Grammar Teaching Practices in EFL Classrooms Grade 9 in FocustolstoianaNo ratings yet

- A Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsDocument5 pagesA Resume of The Practice of Genre-Based Pedagogy in Indonesian SchoolsSiti Himatul AliahNo ratings yet

- Comprehensible Input Through Extensive Reading: Problems in English Language Teaching in ChinaDocument11 pagesComprehensible Input Through Extensive Reading: Problems in English Language Teaching in ChinaMuhammadMalekNo ratings yet

- 4 Kwon PDFDocument40 pages4 Kwon PDFRobertMaldiniNo ratings yet

- Innovative Approaches To Teaching Literature in The World Language ClassroomDocument17 pagesInnovative Approaches To Teaching Literature in The World Language ClassroomAlvina MozartNo ratings yet

- Application of CL in Teaching College English WritingDocument5 pagesApplication of CL in Teaching College English WritingAlam SyahNo ratings yet

- Haifa Al BuainainDocument36 pagesHaifa Al BuainainFarah BahrouniNo ratings yet

- Article Summary - Ghais Aulia Syarif (1202621028)Document3 pagesArticle Summary - Ghais Aulia Syarif (1202621028)ghais auliaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of English Textbook For 8Document13 pagesEvaluation of English Textbook For 8Lê Anh Thư - ĐHKTKTCNNo ratings yet

- Miss, NominanizationDocument20 pagesMiss, NominanizationJam ZhangNo ratings yet

- 1443 3097 1 SMDocument10 pages1443 3097 1 SMleilagerivaniNo ratings yet

- Thái Thị Mỹ Linh K28 Final AssignmentDocument15 pagesThái Thị Mỹ Linh K28 Final AssignmentNguyễn Thảo NhiNo ratings yet

- The Influence of L1 Toward Students' Writing SkillDocument14 pagesThe Influence of L1 Toward Students' Writing SkillTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Uas LTMDocument39 pagesUas LTMdelfian piongNo ratings yet

- Doan Khuong's Critique PaperDocument11 pagesDoan Khuong's Critique PaperBill ChenNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument14 pages1 PBAsafew KelebuNo ratings yet

- Task-Based Language TeachingDocument15 pagesTask-Based Language TeachingSyamimi ZolkepliNo ratings yet

- Learners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolDocument13 pagesLearners' Attitudes Towards Using Communicative Approach in Teaching English at Wolkite Yaberus Preparatory SchoolIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Types of Writing Approaches On Efl Students' Writing PerformanceDocument8 pagesThe Effects of Types of Writing Approaches On Efl Students' Writing PerformanceJashanpreet KaurNo ratings yet

- Innovative Approaches To Teaching Literature in The World Language ClassroomDocument16 pagesInnovative Approaches To Teaching Literature in The World Language ClassroomAnthony ChanNo ratings yet

- Mat GrammarDocument10 pagesMat GrammarLovely WooNo ratings yet

- EFL Writer's Noticing and Uptake: A Comparison Between Models and Error CorrectionDocument30 pagesEFL Writer's Noticing and Uptake: A Comparison Between Models and Error CorrectionChristine YangNo ratings yet

- Reading and Writing 3 PDFDocument18 pagesReading and Writing 3 PDFMohammed Al DaqsNo ratings yet

- EJ1076693Document9 pagesEJ1076693ichikoNo ratings yet

- AGENO ABERAbook ReviewDocument4 pagesAGENO ABERAbook ReviewBangu Kote KochoNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Input-Based and Output-Based Instruction On EFL Learners' Autonomy in WritingDocument9 pagesThe Effect of Input-Based and Output-Based Instruction On EFL Learners' Autonomy in WritingTrần ĐãNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument10 pagesChapter IIMel SantosNo ratings yet

- LanguageDocument22 pagesLanguageDiyah Fitri WulandariNo ratings yet

- Teacher Student InteractionDocument22 pagesTeacher Student InteractionAnonymous tKqpi8T2XNo ratings yet

- Top Notch vs. InterchangeDocument6 pagesTop Notch vs. InterchangegmesonescasNo ratings yet

- Process-Genre Based ApproachDocument25 pagesProcess-Genre Based ApproachRabiya JannazarovaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Grammar in The English Language Classroom: Perceptions and Practices of Students and Teachers in The Ampara DistrictDocument15 pagesTeaching Grammar in The English Language Classroom: Perceptions and Practices of Students and Teachers in The Ampara DistrictTrần ĐãNo ratings yet

- Students View On Grammar Teaching Fdf48e39Document13 pagesStudents View On Grammar Teaching Fdf48e39Nurpazila PBINo ratings yet

- Scholars ViewDocument8 pagesScholars Viewfor studyNo ratings yet

- ILT Volume 10 Issue 2 Page 171-202Document32 pagesILT Volume 10 Issue 2 Page 171-202Reyhane MoradiNo ratings yet

- Grammar Teaching and LearningDocument28 pagesGrammar Teaching and LearningPablo García MárquezNo ratings yet

- Summaries of Some Relevant ResearchesDocument4 pagesSummaries of Some Relevant ResearchesAhmed AbdullahNo ratings yet

- LEiA V8I2A05 TruongDocument21 pagesLEiA V8I2A05 Truongngoxuanthuy.davNo ratings yet

- Chang 2012 English For Specific PurposesDocument14 pagesChang 2012 English For Specific PurposesAmanda MartinezNo ratings yet

- Students Attitudes Towards Cooperative LearningDocument9 pagesStudents Attitudes Towards Cooperative Learningeksiltilicumle9938No ratings yet

- Teaching Grammar: A Survey of Eap Teachers in New Zealand: Roger Barnard & Davin ScamptonDocument24 pagesTeaching Grammar: A Survey of Eap Teachers in New Zealand: Roger Barnard & Davin ScamptonSonia MiminNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Teacher and Learner Beliefs About English Teaching and Learning For Mongolian University StudentsDocument18 pagesAn Investigation of Teacher and Learner Beliefs About English Teaching and Learning For Mongolian University StudentsJohn AdamNo ratings yet

- Action Research in ELT: Growth, Diversity and Potential: University of Sydney Papers in TESOLDocument7 pagesAction Research in ELT: Growth, Diversity and Potential: University of Sydney Papers in TESOLTori NurislamiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Self - Peer and Teacher Assessment in Promoting Iranian EFL Learners Writing PerformanceDocument22 pagesThe Role of Self - Peer and Teacher Assessment in Promoting Iranian EFL Learners Writing Performanceabronnimann86No ratings yet

- Body Part RiddlesDocument2 pagesBody Part RiddlesYNYNo ratings yet

- A4双面-Spectrum Reading, GK(被拖移) PDFDocument3 pagesA4双面-Spectrum Reading, GK(被拖移) PDFYNYNo ratings yet

- Skull Upper Arm Bone BackboneDocument1 pageSkull Upper Arm Bone BackboneYNYNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness and ChantsDocument2 pagesPhonemic Awareness and ChantsYNYNo ratings yet

- Spectrum Reading, MaxmeetsmanDocument1 pageSpectrum Reading, MaxmeetsmanYNYNo ratings yet

- Alphabet Song Lyrics: JazzlesDocument35 pagesAlphabet Song Lyrics: JazzlesYNYNo ratings yet