Professional Documents

Culture Documents

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

138 viewsFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Furukawa Chinese Alchemy

Uploaded by

Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Year 7 Japanese Booklet 2021 PDFDocument154 pagesYear 7 Japanese Booklet 2021 PDFMaliha JamilNo ratings yet

- WuxingDocument6 pagesWuxingCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Chen Techniques For Rotating The DantianDocument3 pagesChen Techniques For Rotating The DantianschorleworleNo ratings yet

- Gikan RyuDocument5 pagesGikan Ryutendoshingan100% (1)

- Characters - Fairy Tail Wiki - Fandom PDFDocument52 pagesCharacters - Fairy Tail Wiki - Fandom PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Curs I-Ching 1 2014Document4 pagesCurs I-Ching 1 2014Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- 陈氏混元38式太极刀Document3 pages陈氏混元38式太极刀Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Cinc Entitats Viscerals PDFDocument7 pagesCinc Entitats Viscerals PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Shamanism in YangshaoDocument2 pagesShamanism in YangshaoCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Mahadihassan Comparative Study of CosmologyDocument5 pagesMahadihassan Comparative Study of CosmologyCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of QigongDocument13 pagesA Brief History of QigongGeo GlennNo ratings yet

- 洪範Document4 pages洪範Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Mahdihassan The Tridosa DoctrineDocument3 pagesMahdihassan The Tridosa DoctrineCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Qijing Bamai Taxtos Medics PDFDocument14 pagesQijing Bamai Taxtos Medics PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong0% (1)

- Ode of The Jade Dragon Yu Long Fu PDFDocument10 pagesOde of The Jade Dragon Yu Long Fu PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas: by Togmay Sangpo Translation by Ruth SonamDocument6 pagesThe Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas: by Togmay Sangpo Translation by Ruth SonamCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Cinc Entitats VisceralsDocument7 pagesCinc Entitats VisceralsCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Chen Techniques For Rotating The Dantian PDFDocument3 pagesChen Techniques For Rotating The Dantian PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Mercury in Traditional MedicinesDocument14 pagesMercury in Traditional MedicinesCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Fruehauf CorrelativecosmoDocument6 pagesFruehauf CorrelativecosmoCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Louis Komjathy PHD Daoist Meditation Theory Method Application v01Document29 pagesLouis Komjathy PHD Daoist Meditation Theory Method Application v01yieldsNo ratings yet

- Shafer Efflorescence of Lang KanDocument12 pagesShafer Efflorescence of Lang KanCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- JapaneseaestheticsofimperfectionDocument10 pagesJapaneseaestheticsofimperfectionLøløNo ratings yet

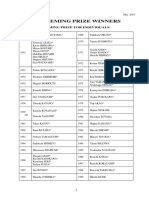

- DP WINNERS LIST The Deming Prize For Individuals201905Document2 pagesDP WINNERS LIST The Deming Prize For Individuals201905Jaime BarrancoNo ratings yet

- NikkoriDocument3 pagesNikkoriIvyNo ratings yet

- L5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorDocument52 pagesL5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorCarlos William LaresNo ratings yet

- Self-Censorship The Case of Japanese Poetry Wartime - Leith MortonDocument20 pagesSelf-Censorship The Case of Japanese Poetry Wartime - Leith MortonJuan Manuel Gomez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- One Piece - Minato Mura - Village HarbourDocument1 pageOne Piece - Minato Mura - Village HarbourKim CheSed FlOres Paller100% (1)

- Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style VillageDocument1 pageOgi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style VillageaphinxwuNo ratings yet

- Ninja - The Ultimate Guide To TH - Wayne LiDocument46 pagesNinja - The Ultimate Guide To TH - Wayne LiFabiano Bertuche100% (2)

- Kimi To NaraDocument2 pagesKimi To NaraClariossa Daora ForthortheNo ratings yet

- Yuhki Kuramoto - A Winter Story PDFDocument3 pagesYuhki Kuramoto - A Winter Story PDFGrace JXNo ratings yet

- Japanese TermsDocument9 pagesJapanese TermsRHENZ ARABIA2003No ratings yet

- Kodanshas Dictionary of Basic Japanese Idioms (Jeff Garrison, Kayoko Kimiya, George Wallace Etc.)Document670 pagesKodanshas Dictionary of Basic Japanese Idioms (Jeff Garrison, Kayoko Kimiya, George Wallace Etc.)ads ads100% (3)

- SumoDocument2 pagesSumoCameberly DalupinesNo ratings yet

- Japanese CinemaDocument4 pagesJapanese Cinemaapi-299433356No ratings yet

- Provider List International Hospital & Surgical Care PremierDocument36 pagesProvider List International Hospital & Surgical Care PremierDian Handayani PratiwiNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Mythology Behind Gamera 3Document7 pagesThe Japanese Mythology Behind Gamera 3dhoinsNo ratings yet

- Shintoism For CotDocument27 pagesShintoism For CotHanz Albrech AbellaNo ratings yet

- Chairman StatusDocument25 pagesChairman StatusMD DUJA UD DOULANo ratings yet

- Group 5Document6 pagesGroup 5jun rey viradorNo ratings yet

- Lec 7Document29 pagesLec 7ARCHANANo ratings yet

- l5r Kyotei Handouts Webquality PDFDocument14 pagesl5r Kyotei Handouts Webquality PDFadolfomix100% (1)

- Shining Force: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument3 pagesShining Force: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchKing BascosNo ratings yet

- Hiroshima Nagasaki PDFDocument30 pagesHiroshima Nagasaki PDFThe Dangerous OneNo ratings yet

- 2 SengokuDocument5 pages2 SengokuAndres Banguera RuizNo ratings yet

- Kitō-Ryū Jūjutsu and The Desolation of Kōdōkan Jūdō's Koshiki-No-KataDocument17 pagesKitō-Ryū Jūjutsu and The Desolation of Kōdōkan Jūdō's Koshiki-No-Katagester1No ratings yet

- Ancient JapanDocument45 pagesAncient JapanHailey RiveraNo ratings yet

Furukawa Chinese Alchemy

Furukawa Chinese Alchemy

Uploaded by

Centre Wudang Taichi-qigong0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

138 views16 pagesFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

138 views16 pagesFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Furukawa Chinese Alchemy

Uploaded by

Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongFurukawa Chinese Alchemy

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf

You are on page 1of 16

Chinese Alchemy:

Its Origins and Development

Yasu Furukawa

Alchemy has often been treated as peculiar to the Western

tradition ; Chinese alchemy has been rather neglected by the Western

historians. For example, in his famous Entstehung und Ausbreitung der

Alchemie (1919), E. ©. von Lippmann has stated, “The Chinese

possessed no characteristic chemical methods of their own, nor any

apparatus of original design.” With a few exceptions,” it has not

been until recently that Chinese alchemy has been systematically

studied in its own light. An indication of renewed attention is

thorough English translations of Chinese alchemical works which have

appeared together with commentaries.” This paper attempts to deal

with the origins of Chinese alchemy and its development, based on these

available materials.

T. L. Davis defines alchemy in general as “the search or the

effort, whether successful or not, by chemical means to prepare a

medicine of longevity or immortality, or by chemical means to prepare

authentic noble metal (e.g., gold) from base metal or both.“ Indeed

alchemy both in the East and the West held two mutually related aims,

ie., longevity or immortality, and gold-making. To attain these goals,

alchemists used chemical means which had been practiced in metal

work by artisans since the Bronze Age. However, it should be noticed

that in addition tn the chemical technology, alchemists had the

theoretical explanations of substantial change ; given such alchemical

theories they belived that they could arrive at their goal. At the same

time, the theories clearly reflected the philosophical framework of the

95

times. For example, Arabic alchemical theory that metals were

composed of mercury and sulphur owed much to Aristotelianism which

had been widely spread On the other hand, Chinese alchemy was

concerned with Taoism as well as the traditional concepts of yin-yang*

and of wwhsing® In this respect, as N. Sivin insists, “What dis-

tinguishes alchemy is the systematic attempts of its practioners to apply

a philosophical framework to chemical operation.”

Before alchemy flourished in China, there had been some

elements of it. As early as the eighth century B.C. there was belief in

the possibility of physical immortality.” J. Needham attributes this

belief to “this-worldy ethos of the Chinese.” He states that with this

ethos,"life on earth was found good and greatly treasured, so that from

the Shang* period onwards, emphasis on longetivity grew and grew,

length of life in some quiet hermitage or surrounded by one’s des-

cendents being the greatest blessing that Heaven could confer.” This

desire for longevity, according to Needham, eventually developed into

the desire for immortality.” Indeed before Buddhism which introduced

a certain pessimism about life in this world and was much concerned

with after-life, the Chinese seem to have little idea of where one was to

go after death, hence the this-worldly emphasis.” In any event, by the

fourth century, immortality was widely thought to be attainable by

technical means such as the taking of drugs (ie., elixirs). There now

appeared immortality cults which were called the cults of Asien.“

These cults at first considered that the eating of food out of golden

vessels could lengthen life. Eventually, gold came to be regarded as a

drug for immortality. Such ideas may have been drawn from an

analogy that gold spontaneously never oxidizes in air, therefore if one

ingests it he would be able to live forever."

There had been a gold industry in China for a thousand years

before the time of Confucius (651 - 479 B.C.). A multitude of gold

objects have been recovered from Shang and Chou® tombs by modern

archaeologists Gold refining was practiced in the Chou and Ch'in‘

periods, as is evidenced by an ancient document about gold.” These

facts show that China had produced gold by herself and had been

96

regarding it as a valuable metal long before alchemy appeared.

However, while natural gold would serve the purpose of the members of

immortality cults, they wished to make artifical gold rather than use

natural. As Ko Hungé (A.D. 283 - 343), an alchemical writer, later

reported, most of them [members of immortality cults] were poor; it

was therefore more convenient for them to make the gold themselves.

Furthermore, “the gold which is made by transformation embodies the

essences of many different ingredients, so that it is superior to natural

gold.” Thus, unlike Alexandrian alchemy whose final goal was to

make gold, Chinese alchemy pursued gold-making as a means to attain

immortality. This is why Chinese alchemy was called line tan shu,” the

art of medical gold. Line chin shu,‘ the art of gold-making, was

regarded as a step toward lien tan shu. For this reason Chinese

alchemical literautre is commonly divided into the two parts, ie., the

preparation of gold and the method of consuming it to attain im-

mortality.

Chinese alchemy was based upon the fundamental concepts of

Wohsing, the Five Elements, and Yin- Yang, the Two Contraries. T. L.

Davis observes, “Both are genuine scientific concepts which supply

categories for the description of natural things, and both in the writings

of the alchemists are involved with magical and fantastic connota-

tion.""® The notion of wu-hsing may be traced back to the twelfth

century B.C, In the Shu Ching! (Book of Historical Documents [twelfth

century B.C.] ), one of the earliest sources that includes this term, it

meant simply the constituents of materical things: all material

substances are composed of five elements, ie., water, fire, wood, metal,

and earth. By the fourth century B.C., this notion was further

extended, with each elment having its relation to the otheres : water is

channeled and contained by earth, earth is broken by wood, wood is

shaped by metal, metal is melted by fire, fire is put out by water, and

so on." Moreover, the concept wu-hsing was applied to nearly

everything. Hence, for example, planets, seasons, locations, colors,

tones, tastes, smells, grains, animals, virtues, dynasties, and others were

respectively classified into five categories, and the relations of these

7

were widely discussed among the Chinese."® Therefore it is not

surprising that the concept wu-hsing was employed for the explanation

of substantial change in Chinese alchemy.

On the other hand, the notion of yin-yang appeared much later

than the wu-hsing. Davis places the date as sometime after Con-

fucius."® Although the terms yin and yang were originally used in the

literal meaning, i.e., shade and light, later the couplet yin-yang had the

notion of two contrasted principles which regulated the universe :

It was supposed that the primal matter, t’ai-chi,* in its gyrations

gradually separated into two parts, the /ang-i' or regulating

powers which together constituted the soul of the universe. The

heavy and gross part, yin, settled and formed the earth, while the

fine and light part, yang, remained suspended and formed the

heavens. Yin was the female principle, negative, heavy, earthy,

and dry, typifying in general the more undesirable aspects of

nature such as cold, darkness, weakness, and death. Yang was

the positive, male principle, desirable, active, fiery, possessive of

qualities directly opposed to those of yin. From the interaction

of these two contraries, all things in the universe were created

and controlled in their various manifestations.2”

While the concept wu-hsing expresses the constitutent elements of

things and their order, yin-yang can be considered to show a state of

things, i.e., somewhat potentiality. Thus the changing seasons, for

example, can be explained as follows. In spring, yang began to come

about ; in summer it reaches its highest peak ; on the contrary, yin

began to appear in autumn ; and it arrives at its peak in winter. But in

summer yin has already been involved and successively increases

toward autumn.” As D. Bodde suggests, unlike Western “good-versus-

evil type of dualism,” yin-yang dualism was “based not upon mutual

opposition but upon mutual harmony.” Both counterparts were equally

essential for the existence of the universe just as that of male and

female ; “neither is necessarily superior or inferior from a moral point

of view.”

The two concepts of wu-hsing and yin-yang were, it has been told,

98

combined and elaborated by Tsou Yen™ (c. 350-270 B.C.) and his

followers. Although Tsou Yen's writings are no longer extant, several

sources refer to him and his school. For example, Ssu-ma Ch’ien” (c.145

-90 B.C), in his Shik Chi° (Historical Record or Record of the

Historian), reports that “Tsou Yen was famous among the feudal lords

(for his doctrine) that the Yin and Yang control the cyclical movements

of destiny,” and that “the disciples of the Master Tsou discussed and

wrote about the cyclical succession of the Five Powers.”°9 The Chien

Han Shu? (History of the Former Han Dynasty [c. 100 A.D.] ) states,

“Tsou Yen's technique for prolonging life by a method of repeated

(transformation).” So far as historical records in China are concerned,

Tsou Yen is the earliest to be mentioned as a person who engaged in

alchemy. Therefore most recent authorities place the date of origin of

Chinese alchemy around his time, ie., the fourth century B.C.°° We

should also know that it was by this time that alchemy had embraced

such theoretical entities as wu-hsing and yin-yang.

Chinese alchemy was much associated with Taoism. Actually

most of the alchemists in Chinese history were Taoists. For this reason,

some modern scholars have supposed the Taoist origin of Chinese

alchemy.°” However, it may be considered that there is no evidence of

Taoism’s influence on the earliest alchemy ; or at least, Tsou Yen’s

ideas did not reflect the contemporary Taoism. Taoism had originated

as a highly abstract philosophy during the sixth century B.C. It was

founded by Lao Tzu,* a somewhat shadowy figure, whose thought

appears to have been collected by his disciples in the third century B.C.

under the title of his name, ie., Lao Tzu.” Tao,’ the Way, is the

principle of all things:

There is a thing confusedly formed,

Born before heaven and earth.

Silent and void

It stands alone and does not change,

Goes round does not weary,

It is capable of being the mother of the world.

1 know not its name

99

So I style it “the way.”?®

Lao Tzu continued, “Tao produced the One, the One produced the Two,

the Two produced the Three, and the Three produced the myriad

phenomenal. things.”*” In other words, the phenomenal world is

continuously produced out of the Tao. This rather abstract philosophy

was carried further by his followers, such as Chuang-Chou® (369 - 286

B.C.) . According to their views, Nature is impersonal purposeless

cosmos in which everything, including human beings, has its natural

place and function: “Let Nature take its course! Be yourself.”® It was

this course of Nature that they called Tao. Their concern was, unlike

moralistic Confucianism, with Nature itself, and not with artificial

society. One seeks Tao by inaction, by solitude, and by spiritual

practices. Those who attained the Tao were supposed to be hsien,

which eventually came to mean the immortals.*” The Taoists began to

search for the Way not only by mental practices, but by physical

operations including alchemy. Thus probably, by the second B.C., it

became a common practice for Taoists to study alchemy in search for

elixir of immortality.“ As Taoism spread in China, alchemy also

became popular. The main systemizers of alchemy, such as Wei Po-

yan‘ (c.142A.D.) ,Ko Hung (283 - 343 A.D.) , Sun Ssu-mo! (seventh

century A.D.), and others were characteristically all Taoists.

Therefore, to the later Chinese the term “alchemist” became syn-

onymous to “Taoist.” But it should be noted that alchemy was only a

part of the practices of Taoism ; as one statistic indicates, only 132 titles

of 1,464 Taoist treatises (approximately 11 percent) relate to alchmy.”

The fact that alchemy spread widely during the second century

B.C. may be evidenced by the following passages in Chien Han Shu:

The emperor Wen Ti’ (r. 179 - 156 B.C.), in the fifth year of his

reign, had allowed the common people to mint (ie., cast) coin

(without special authorisation), and this law had not yet been

abrogated. During the intervening time, and earlier, many people

had made artificial gold.“?

In 144 B.C. the Former Han Emperor Ching-Ti” (r. 156 - 141 B.C.) issued

an edict to prohibit the making of artificial or counterfeit gold :

100

In the sixth year of the middle (part of the reign). . . in the

twelfth month. . . a statute was established forbidding the

(unauthorised private) minting (lit. casting) of coin, and the

(making of) artifical or counterfeit gold (wei hwang chin*) under

penalty of death.*®

Despite such an edict, and also the observation in the Chien Han Shu

that “they incurred heavy expenses and in the end they did not

succeed” in fabricating gold, alchemy persisted and became deeply

rooted in Chinese tradition.

According to Sivin, there remain over a hundred alchemical

treatises, from half a millennium to two millenia old.” The earliest of

them is the Chow I Ts’an T’ung Ch’? (The Concordance of the Three :

an aprocryphal tradition of interpretation of the Book of Changes, 142

A.D.) which is attributed to Wei Po-yang. This work is regarded as the

oldest complete alchemical book extant in any culture.” It is also

referred to as the fruit of the outgrowth of alchemical tradition which

preceded him. Ts’an, “The Three,” indicates the alchemical oper-

ations, the Taoist theories, and the Changes. Wei Po-yang seems to

have considered the Three to be the same one : to be devoted to alchemy

is to search for tao, the Way, as well as to follow the principles of

change such as wu-hsing and yin-yang. As a Taoist, Wei Po-yang

shows his esoteric attitude toward alchemy :

Those who love the Tao trace things to their roots. They

carefully observe the Five Elements to determine the weights (of

the materials used), Profound reflection should be made, but no

discussion with others is necessary. The secrets should be

carefully guarded, and the knowledge should not be handed down

in writing.”

Therefore in his writing, Wei Po-yang, like many others and like

Western alchemists, devised symbolic and imaginative names for many

substances. He used such terms as “White Tiger,” “Gray Dragon,” and

“Scarlet Bird.” The use of such symbolic language resulted in the

following account and description of an alchemical process.

Above, cooking and distillation take place in the caldron ; below,

101

blazes the roaring flame. Afore goes the White Tiger leading the

way ; following comes the Grey Dragon. The fluttering Chu-

niao? (Scarlet Bird) flies the five colors. Encountering ensnaring

nets, it is helplessly and immovably pressed down and cries with

pathos like a child after its mother. Willy-nilly it is put into the

caldron of hot fluid to the detriment of its feathers. Before half

of the time has passed, Dragons appear with rapidity and in great

number. The five dazzling colors change incessantly. Tur-

bulently boils the fluid in the fing" (furnace). One after another

they appear to from an array as irregular as a dog’s teeth.

Stalagmites which are like midwinter icicles, are spit out

horizontally and vertically. Rocky heights of no apparent

regularity make their appearance, supporting one another. When

‘yin (negativeness) and yang (positiveness) are properly matched,

tranquility prevails.“

His description consisted of metaphor upon obscure metaphor. As

Needham points out, “what the fundamental alchmical reactions

mentioned in the Ts’an T’ung Ch’i were is not at all certain... .

Even the meaning of his terminology is controversial.“ But from the

above passage we may see that Wei Po-yang is describing a process of

transmutation from “Tiger” into “Dragon” by heat, during which one

observes a change of color in five phases. The terminal point of this

reaction is the point at which yin and yang are properly matched. It

precisely indicates his application of wa-hsing and yin-yang theories to

the chemical operation. Elsewhere he argues that mercury refined from

cinabar and lead ore are the prime sources of the elixir. Mercury is rich

in yang while lead is rich in yin; so a chemical change naturally occurs

between them.“ This is a process we now call amalgamation, The

above passage appears to show a similar reaction. Wei Po-yang also

considered the wu-hsing, the Five Elements, i.e., water, fire, wood,

metal, and earth to correspond with five colors, respectively black, red,

blue, white, and yellow.“ By using this correspondence he was able to

explain the change of color of the metals in reaction in terms of the

cyclical relation of each element.

102

There is a passage in which Wei Po-yang clearly expressed elixir

of immortality :

If even the herb chu-sheng*® can make one live longer,

Why not try putting the Eixir into the mouth?

Gold by nature does not rot or decay ;

Therefore it is of all things most precious.

When the artist (i.e.,alchemist) includes it in his diet.

The duration of his life becomes everlasting. . .

When the golden powder enters the five entrails,

A fog is dispelled, like rain-clouds scattered by wind.

Fragrant exhalations pervade the four limbs;

The countenance beams with well-being and joy.

Hairs that were white all turn to black ;

Teeth that had fallen grow in their former place.

The old dotard is again a lusty youth ;

‘The decrepit crone is again a young girl.

He whose from is changed and has escaped the perils of life,

Has for his title the name of True Man.“”

This passage shows the goal which was common to the whole Chinese

alchemy. The similar idea can be seen in the Pao pu’ tzu nei p’ien® of

Ko Hung:

The more the Gold Medicine is heated, the more exquisite

are the transformations it passes through. Yellow gold will not

be changed even after long heating in the fire, nor will it rot after

long burial in the earth, The eating of these two medicines

(Huan tan, returned medicine, and Chin i,°° gold fluid, or gold-

making fluid] will therefore strengthen one’s body that he will

not grow old and die. This is a case of deriving strength from an

external substance, comparable to the maintenance of fire by oil

and the protection of the leg from rotting in water by a smear of

copper blue, which merely acts on the surface.“*”

Since Ko Hung’s style is much more simplified and richer in variety

than that of Wei Po-yang, this work became a standard Chinese text on

this subject.“ A chapter of the book provides a great variety of

103

formulas for the preparation of the elixirs of immortality. For

example,

The fourth medicine is called Huan tan (returned med-

icine). Immortality will come to the eater in a hundred days after

eating. Above him will hover pheasants, peacocks, and red birds,

and at his side will be fairies. Yellow gold will be formed

immediately by heating a knifeblade full of the medicine ad-

mixed with a catty of quicksilver [the philosopher’s stone] .

Whoever has his money painted with it will have it back on the

same day that he spends it. Words painted with this medicine on

the eyes of common people will keep spirits away from them.

It was, as mentioned above, a standard practice for alchemists to

use mercury and lead as the sources of the elixirs of immortality.

Therefore it is not surprizing that in their pursuit many of them

ironically died after partaking those elixirs.*” There were many

emperors and court officials who employed some distinguished

alchemists to attain immortality. The official Dynastic Histories tell us

that many of them became the victims of elixir poisoning. The Chin

Shu (Official Histroy of the Chin Dynasty) reports the case of the Chin

emperor Ai Ti** (r. 361 - 366 A.D.) who died at the age of only 25:

He had a liking for the art of the alchemists. He abstaind from

cereal grains, but consumed elixirs. As the result of an overdose

he was poisoned and no longer knew what was going on around

him.

Needham calls the period between the end of Chin™ (c, 400 A.D.) and

late T’ang"' (c. 800 A.D.) “the golden age of alchemy” during which the

elixir of life continued to attract many a Chinese emperor.) More so

than the others, the T’ang Dynasty openly accepted Taoism and

alchemy ;° this only resulted in more victims of elixir poisoning.

According to M. Yoshida, of twenty-one emperors and an empress of

the T’ang Dynasty, seven partook of the elixirs with six being killed.

A passage from the Chiu Tang Shu (Old Standard History of the

T'ang) decribes Emperor Wu Tsung“ (r. 840 - 846 A.D.):

The emperor (Wu Tsung) favoured alchemists took some

104

of their elixirs, cultivated the arts of longevity and personally

accepted (Taoist) talismans. The medicines made him very

irritable, losing all normal self-control in joy or anger; finally

when his illness took a turn for the wose he could not speak for

ten days at a time. The prime minister Li Te-Yu" and others

asked for audience but were refused, and nobody inside or

outside the palace knew his real state, so that people were

alarmed and sensed danger. On the 23rd day of that month (22nd

April 846) the imperial will was read, and the emperor's uncle,

Prince Kuang™" (Li Shen") ascended the throne (as Hsuan

Tsung™) in front of the coffin.**

Besides these emperors and court officials, many common people may

have lost their lives by ingesting the elixirs of life, although such

instances were usually not recorded. As a result of such events, by the

time of Sung’? (960 - 1127) more caution was exercised in the

preparations for elixir-making, “not only in the composition of elixirs

themselves, but also in attempts to elaborate pharmaceutical ways and

means of counteracting the toxic effect.” It should be added that as

the art of alchemy was practiced the equipment for its operation

became more and more developed. These developments include such

chemical aparatus as various types of caldrons with three legs used for

reaction vessels, a number of stoves, baths and stills.* However, as

Taoism lost favor, especially after the Mongolian invasion during the

late thirteenth century, Chinese alchemy finally ceased to develop.”

Recent scholarship has led to the strong urging by some that

Chinese alchemy has influenced the Western world.“ Arguing that

contacts between East and West have a very long history, and further,

observing many similarities in alchemical literature, some scholars

have concluded that there exists an historical and an intellectual

connection between Eastern and Western alchemical speculations.

Arabic alchemy, which flourished during the tenth and eleventh

centuries A.D., embraced some concepts similar to that of Chinese.

Therefore H. M. Leicester concludes :

Combining ideas from both Alexandria and China, they

105

[the Arabs] gave to alchemy the explicit formulation of the

sulfur-mercury theory of the composition of substances, they

added a clear statement of the doctrine of the elixir, the

philosopher's stone, and probably again under Chinese influence,

they clarified the concept of the therapeutic virtues of the stone

in curing “sick” metals, and perhaps human illnesses as well.*?

Some Arabic alchemical writers such as al-Razi (d. 923 or 924), like the

Chinese, stressed the medical effect of alchemical elixirs. After taking

over Arabic alchemy, the Latins, by the fifteenth century, shifted “their

objectives from elixirs for gold to elixirs for eternal life or simply

superior medicines for specific cures.” This eventually led to the

foundation of the so-called “iatrochemistry.”. Thus, it is not groundless

to suspect the influence of Chinese alchemy upon the West.

‘A question has ofen been raised : why was not Chinese alchemy

transformed into European style chemistry? Some historians have

attempted to answer the question. For example, C. O. Hucker states,

c Taoinst alchemists were not interested in generalizing their

methods and observations. For this reason, and because China’s best

minds were normally occupied with other intellectual pursuits, Chinese

alchemy was never transformed into science.”* However it should be

noted that Chinese alchemy arose and was developed strictly within the

Chinise cultural framework. Alchemists in China did have their own

explanations for alchemical phenomena based on their philosophy.

Being a “True Man” or hsien through alchemy was their ultimate

desire. To Taoists hsien was nothing but the most intellectual and

completed human state, Thus Chinese alchemy should be understood in

its own light, rather than as a “failed prototype” of modern science.

106

Chinese Characters Referred to In the Paper

a i 1 ay He wo oO if hh &

bok it m iff x Re ii

cif n FM ya Ble jj @iar

ds fil o # Ac, 2 OR & kk ak Be

e fl p of a aa Mh 11 f& Ht

f & q & f bb & ® mm %

g & rf cco TURE ii on #

ho s Ht f dd & com oo

i & ffi t ee f im

ji & # uw ff @ =

k Km v gg i

NOTES

(1) Edmund 0. Lippman, Entstehung und Ausbreitung der Alchemie (Berlin :

Spengler, 1919), vol. I, p. 456.

(2) Eg, Obed S. Johnson, A Study of Chinese Alchemy (Shanghai:

Commercial Press, 1928): Tenney L. Davis and Lu-Ch’ang Wu, “An

Ancient Chinese Treatise on Alchemy Entitled Ts’an T’ung Ch’i,” Isis, 18

(1932), pp. 210-289 ; and Masumi Chikashige. Alchemy and Other Chemical

Achievements of Ancient Orient (Tokyo : Rokakudo Uchida, 1936).

(3) A complete translation of Ko Hung’s Pao p’u t2u nei p’ien is in James R.

Ware, Alchemy, Medicine, Religion in the China of A.D. 320: The Nei

Pien of Ko Hung (Pao-p'u teu) (Cambridge : MIT. Press, 1967). N. Sivin

has made a full translation of the Tan ching yao chueh of Sun Ssu-mo

(seventeenth century A.D.): Nathan Sivin, Chinese Alchemy : Preliminary

Studies (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1968). A considerable

amount of new materials on Chinese alchemy are available in Joseph

Needham, Science and Civilisation in China (7 vols ; Cambridge: At the

University Press, 1954- ), vol. 5, Chemistry and Chemical Tchnology(1974- ).

107

(4) Tenney L. Davis, “The Problem of the Origins of Alchemy,” The

Scientific Monthly, 43 (1936), P.551.

(5) For Arabic alchemy, see Robert P. Multhauf, The Origins of Chemistry

(New York: Franklin Watts,Inc., 1967),pp. 124-142.

(6) Sivin, p. 24.

(7) Ibid, p. 25.

(8) Joseph Needham (and Lu Gwei-djen), Science and Civilistion in China,

vol. 5, part 2, p. 82.

(9) Charles 0. Hucker, China's Imperial Past : An Introduction to Chinese

History and Culture (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1975), p. 215.

() Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 2, p. 82.

a) Ibid.

(2) Cheng Te-k'un, Archaeology in China (Cambridge: W. Heffer and Sons

Ltd., 1959-), II, pp. 11, 161, and 198.

(3) Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 2, p. 51.

(4) Pao p’u tau nei p'ien, ch. 16, pp. 5a ff.: cited in Needham, Science and

Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, pp. 1-2

(5) Davis, “An Ancient Chinese Treatise on Alchemy Entitled Ts’an T’ung

Chi” p. 216.

(6) Ibid, p. 217.

() Hucker, p. 195.

i Davis, “An Ancient Chinese Treatise on Alchemy Entitled Ts'an T’ung

Chi.” p. 218.

9 [bid

(0) Ibid, p. 220,

() Keizo Hashimoto, “Chugoku no Kagaku” (Chinese Science), Kagaku no

Rekishi (A History of Science), ed. by N. Shimao, in Japanese (Tokyo :

Sogensha, 1978), p. 38.

(2) Derk Bodde, “Dominant Ideas, “China (Berkeley: Los Angeles:

University of California Press, 1946), ed. by Harley F. MacNair, p. 22.

(8) Ssu-ma Ch’ien, Shih Chi, pp. 10b-11b: cited in Needham, Science and

Civlisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 13.

Ch’ien Han Shu, ch. 36, 7a: cited in Needham, Science and Civilisation

in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 12.

0) For example, ibid, pp. 2, 7, and 12-13; Homer H. Dubs, “Taoism,” in

MacNair ed., China, p. 284; Hucker, p. 204.

(6 Exg.. Johonson, esp. the first two chs.

() See Hucker, p. 88 ff.

(8) Lao tzu, 25, Lao tzu. Tao te ching (Harmondsworth, Middlesex, 1963), tr.

by D.C. Lau, p. 82.

108

(09) Lao teu, 42.

(0) Hucker, p. 90.

Gl) The Chinese character hsien, (il, consists of man (4) and mountain

(i) , which, it might be argued, originally implied who inhibits a

mountain,

(2) A document written in the early first century A.D. suggests the fact that

there were some Taoists who dealt with gold-making during the second

century B.C. See Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part

3, p. 26.

(3) Davis, “An Ancient Chinese Treatise on Alchemy Entitled Ts‘an T’ung

Ch'i,” pp. 225-6.

() Chien Han Shu, ch. 5, p. 7b: cited in Needham, Science and Civilization

in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 27.

(5) Chien Han Shu, ch. 5, p. 7b: Ibid., p. 26.

(8) Chien Han Shu, ch. 5, p. 7b: Ibid., p. 27.

(0 Sivin, p. 36.

(Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 50.

(8) Ts'an T’ung Ch’i includes a description of several earlier alchemists,

which suggests that Wei Po-yang was clearly within their tradition.

0) See Mitsukuni Yoshida, Renkinjutsw (Alchemy) in Japanese (Tokyo:

Chuokoron-Sha, 1963), p. 29.

() san Tung Chi, ch. 33, p. 10b: cited in Needham, Science and

Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 74.

() TIbid., ch. 64: Davis, "An Ancient Chinese Treatise or Alchemy Entitled

Ts'an T'ung Chi,” pp. 258-9.

(8) Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 66.

See ibid.

(6) Tbid., p. 73.

i) Yoshida, p. 35.

4) Ts'an Tung Chi, ch. 27: cited in Arthur Waley, “Notes on Chinese

Alchemy,” Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies,

University of London 6 (1930), p. 11

48) Pao p’u teu nei p'ien: Wu Lu-ch’iang and Tenney Davis, “An Ancient

Chinese Alchemical Classic. Ko Hung on the Gold Medicine and the Yellow

and the White,” Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and

Sciences, 70(1935), p. 236.

9 Yoshida, p. 58.

60) Pao p'u tzu nei prien: Wu and Davis, pp. 240-1.

6) See Ho Ping-yu and J. Needham, “Elixir Poisoning in Mediaeval China,”

Janus, 48 (1959), pp. 221-51.

109

(3) Chin Shu, ch. 8, p. cited in ibid., p. 222.

(3) Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 117.

6 Exg., Hucker, p. 205.

(Yoshida, p. 61.

(9) Chiu T’ang Shu, ch. 18A: cited in Ho Ping-yu and Needham, p. 224.

(3) Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 208.

(8 For chemical aparatus of Chinese alchemy, see Ho Ping-yu and J.

Needham, “The Laboratory Equipment of the Early Mediaeval Chinese

Alchemists,” Ambix, vol. 7(1959), pp. 57-115.

(9 Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, vol. 5, part 3, p. 208,

() Eg. ibid., vol. 5, part 2, p. 15: Henry M. Leicester, The Historical

Background of Chemistry (New York : Dover Publications, Inc., 1971), pp.

60, 62; and F. Sherwood Taylor, The Alchemists, Founders of Modern

Chemistry (New York : Henry Shuman, 1949), p. 75.

) Leicester, p. 72.

(@) Robert P. Multhauf, “The Science of Matter,” Science in the Middle Ages

ed. by David C. Lindberg (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978), p.

380.

(| Hucker, p, 204.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank Professor Sidney D. Brown in the East

Asian Program at the University of Oklahoma for his comments and

helpful suggestions.

110

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Year 7 Japanese Booklet 2021 PDFDocument154 pagesYear 7 Japanese Booklet 2021 PDFMaliha JamilNo ratings yet

- WuxingDocument6 pagesWuxingCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Chen Techniques For Rotating The DantianDocument3 pagesChen Techniques For Rotating The DantianschorleworleNo ratings yet

- Gikan RyuDocument5 pagesGikan Ryutendoshingan100% (1)

- Characters - Fairy Tail Wiki - Fandom PDFDocument52 pagesCharacters - Fairy Tail Wiki - Fandom PDFJohnNo ratings yet

- Curs I-Ching 1 2014Document4 pagesCurs I-Ching 1 2014Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- 陈氏混元38式太极刀Document3 pages陈氏混元38式太极刀Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Cinc Entitats Viscerals PDFDocument7 pagesCinc Entitats Viscerals PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Shamanism in YangshaoDocument2 pagesShamanism in YangshaoCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Mahadihassan Comparative Study of CosmologyDocument5 pagesMahadihassan Comparative Study of CosmologyCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of QigongDocument13 pagesA Brief History of QigongGeo GlennNo ratings yet

- 洪範Document4 pages洪範Centre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Mahdihassan The Tridosa DoctrineDocument3 pagesMahdihassan The Tridosa DoctrineCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Qijing Bamai Taxtos Medics PDFDocument14 pagesQijing Bamai Taxtos Medics PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong0% (1)

- Ode of The Jade Dragon Yu Long Fu PDFDocument10 pagesOde of The Jade Dragon Yu Long Fu PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- The Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas: by Togmay Sangpo Translation by Ruth SonamDocument6 pagesThe Thirty-Seven Practices of Bodhisattvas: by Togmay Sangpo Translation by Ruth SonamCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Cinc Entitats VisceralsDocument7 pagesCinc Entitats VisceralsCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Chen Techniques For Rotating The Dantian PDFDocument3 pagesChen Techniques For Rotating The Dantian PDFCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Mercury in Traditional MedicinesDocument14 pagesMercury in Traditional MedicinesCentre Wudang Taichi-qigong100% (1)

- Fruehauf CorrelativecosmoDocument6 pagesFruehauf CorrelativecosmoCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- Louis Komjathy PHD Daoist Meditation Theory Method Application v01Document29 pagesLouis Komjathy PHD Daoist Meditation Theory Method Application v01yieldsNo ratings yet

- Shafer Efflorescence of Lang KanDocument12 pagesShafer Efflorescence of Lang KanCentre Wudang Taichi-qigongNo ratings yet

- JapaneseaestheticsofimperfectionDocument10 pagesJapaneseaestheticsofimperfectionLøløNo ratings yet

- DP WINNERS LIST The Deming Prize For Individuals201905Document2 pagesDP WINNERS LIST The Deming Prize For Individuals201905Jaime BarrancoNo ratings yet

- NikkoriDocument3 pagesNikkoriIvyNo ratings yet

- L5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorDocument52 pagesL5R 1e - S2 Twilight HonorCarlos William LaresNo ratings yet

- Self-Censorship The Case of Japanese Poetry Wartime - Leith MortonDocument20 pagesSelf-Censorship The Case of Japanese Poetry Wartime - Leith MortonJuan Manuel Gomez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- One Piece - Minato Mura - Village HarbourDocument1 pageOne Piece - Minato Mura - Village HarbourKim CheSed FlOres Paller100% (1)

- Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style VillageDocument1 pageOgi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style Village Ogi-Machi Gassho Style VillageaphinxwuNo ratings yet

- Ninja - The Ultimate Guide To TH - Wayne LiDocument46 pagesNinja - The Ultimate Guide To TH - Wayne LiFabiano Bertuche100% (2)

- Kimi To NaraDocument2 pagesKimi To NaraClariossa Daora ForthortheNo ratings yet

- Yuhki Kuramoto - A Winter Story PDFDocument3 pagesYuhki Kuramoto - A Winter Story PDFGrace JXNo ratings yet

- Japanese TermsDocument9 pagesJapanese TermsRHENZ ARABIA2003No ratings yet

- Kodanshas Dictionary of Basic Japanese Idioms (Jeff Garrison, Kayoko Kimiya, George Wallace Etc.)Document670 pagesKodanshas Dictionary of Basic Japanese Idioms (Jeff Garrison, Kayoko Kimiya, George Wallace Etc.)ads ads100% (3)

- SumoDocument2 pagesSumoCameberly DalupinesNo ratings yet

- Japanese CinemaDocument4 pagesJapanese Cinemaapi-299433356No ratings yet

- Provider List International Hospital & Surgical Care PremierDocument36 pagesProvider List International Hospital & Surgical Care PremierDian Handayani PratiwiNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Mythology Behind Gamera 3Document7 pagesThe Japanese Mythology Behind Gamera 3dhoinsNo ratings yet

- Shintoism For CotDocument27 pagesShintoism For CotHanz Albrech AbellaNo ratings yet

- Chairman StatusDocument25 pagesChairman StatusMD DUJA UD DOULANo ratings yet

- Group 5Document6 pagesGroup 5jun rey viradorNo ratings yet

- Lec 7Document29 pagesLec 7ARCHANANo ratings yet

- l5r Kyotei Handouts Webquality PDFDocument14 pagesl5r Kyotei Handouts Webquality PDFadolfomix100% (1)

- Shining Force: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument3 pagesShining Force: Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchKing BascosNo ratings yet

- Hiroshima Nagasaki PDFDocument30 pagesHiroshima Nagasaki PDFThe Dangerous OneNo ratings yet

- 2 SengokuDocument5 pages2 SengokuAndres Banguera RuizNo ratings yet

- Kitō-Ryū Jūjutsu and The Desolation of Kōdōkan Jūdō's Koshiki-No-KataDocument17 pagesKitō-Ryū Jūjutsu and The Desolation of Kōdōkan Jūdō's Koshiki-No-Katagester1No ratings yet

- Ancient JapanDocument45 pagesAncient JapanHailey RiveraNo ratings yet