Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effective Screening12

Effective Screening12

Uploaded by

ponekCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effective Screening12

Effective Screening12

Uploaded by

ponekCopyright:

Available Formats

Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Vaccine

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/vaccine

ICO Monograph Series on HPV and Cervical Cancer: Asia Pacic Regional Report

Epidemiology and Prevention of Cervical Cancer in Indonesia, Malaysia,

the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam

Efren J. Domingo a, , Rini Noviani b , Mohd Rushdan Md Noor c , Corazon A. Ngelangel d ,

Khunying K. Limpaphayom e , Tran Van Thuan f , Karly S. Louie f , Michael A. Quinn g

a

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of the Philippines College of Medicine - Philippine General Hospital, Manila, the Philippines

Sub-Directorate of Cancer Control, Directorate of Non Communicable Disease Control, Directorate General of Disease Control and Environmental Health and

Ministry of Health of the Republic of Indonesia, Jakarta, Indonesia

c

Gynaecology Oncology Unit, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Hospital Sultanah Bahiyah, Alor Star, Kedah, Malaysia

d

Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Department of Medicine, Philippine General Hospital, University of the Philippines, Manila, the Philippines

e

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Faculty of Medicine, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok, Thailand

f

Unit of Infections and Cancer (UNIC), Cancer Epidemiology Research Program (CERP), Institut Catal dOncologia - Catalan Institute of Oncology (ICO),

LHospitalet de Llobregat (Barcelona), Spain

g

Oncology and Dysplasia Unit, Royal Womens Hospital, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

b

a r t i c l e

Keywords:

Asia Pacic

Indonesia

Malaysia

Philippines

Thailand

Vietnam

HPV

Cervical cancer

Prevalence

Vaccine

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Cervical cancer remains one of the leading causes of cancers in women from Indonesia, Malaysia, the

Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. High-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) types, particularly HPV-16 and

18, are consistently identied in cervical cancer cases regardless of geographical region. Factors that have

been identied to increase the likelihood of HPV exposure or subsequent development of cervical cancer

include young age at rst intercourse, high parity and multiple sexual partners. Cervical cancer screening

programs in these countries include Pap smears, single visit approach utilizing visual inspection with

acetic acid followed by cryotherapy, as well as screening with colposcopy. Uptake of screening remains

low in all regions and is further compounded by the lack of basic knowledge women have regarding

screening as an opporunity for the prevention of cervical cancer. Prophylactic HPV vaccination with the

quadrivalent vaccine has already been approved for use in Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, while

the bivalent vaccine has also been approved in the Philippines. However, there has been no national or

government vaccination policy implemented in any of these countries.

2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

2. Burden of cervical cancer in Southeast Asia

The burden of cervical cancer in Southeast Asia is moderately

high, where the costs of nationwide organized cytology screening have been a signicant limitation. The use of Pap testing for

cytology-based screening has been highly effective in preventing

cervical cancer in industrialized countries and will most likely be

effective in countries where screening is limited or nonexistent.

Hence, the use of alternative screening modalities, such as visual

inspection of the cervix aided by acetic acid (VIA) with or without

magnication, is currently under evaluation. In addition, prophylactic human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination for the prevention

of infection and related disease is being considered as an additional

cervical cancer control strategy.

2.1. Cervical cancer incidence and mortality

Tel.: +63 2 5255908; fax: +63 2 5255908.

E-mail address: efrendomingo@hotmail.com (E.J. Domingo).

0264-410X/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.039

Cervical cancer is the leading cancer in women in Vietnam and

Thailand, and the second most common cancer in Malaysia, the

Philippines and Indonesia [1]. Furthermore, it is the most common

cause of death in women in Vietnam, the second in Indonesia and

the Philippines, third in Thailand and fourth in Malaysia [1].

In Southeast Asia, cervical cancer incidence (age-standardized

rate (ASR) 15.7 per 100,000) is similar for Indonesia and Malaysia.

Higher and similar ASRs are observed between the Philippines

(ASR: 20.9), Thailand (ASR: 19.8) and Vietnam (ASR: 20.2) [1].

Fig. 1 shows the ASR of cervical cancer in countries with existing cancer registries and the high variability within Malaysia, the

Philippines and Thailand [2]. An ASR of 17.5 was reported in the

Rizal province of the Philippines (19931997) [3]; this rate does

not differ signicantly from recent unpublished data nor from that

of Manila (ASR: 19.8). In Vietnam, the incidence is intermediate,

M72

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

in Chiang Mai and 54.5% in Khon Kaen. The annual cost of care is

estimated at US$10 million [9].

2.1.5. Vietnam

There are over 29 million women in Vietnam over the age of

15 years. More than 6,000 new cases of cervical cancer and 3,000

deaths are estimated each year. Cervical cancer ranks as the second

most common cancer in women ages 1544 years [4].

3. HPV prevalence in Southeast Asia

3.1. HPV prevalence in cervical cancer: Indonesia, Malaysia, the

Philippines and Thailand

Figure 1. Age-standardized (world) incidence rates of cervical cancer by cancer

registries (19982002) in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand [2].

however rates were 4-fold higher in Ho Chi Minh City in the south

compared to Hanoi in the north [3].

2.1.1. Indonesia

Each year approximately 15,000 new cervical cancer cases and

7,500 cancer-related deaths are reported. It is the second most frequent cancer in women of reproductive age 1544 years [4].

2.1.2. Malaysia

In Malaysia, the overall incidence rate is 19.7 per 100,000

women, however differs by ethnic group. Ethnic Chinese women

have the highest ASR of 28.8 per 100,000, followed by ethnic Indians with 22.4 and ethnic Malays (includes Peninsular Malaysia but

not East Malaysia) with 10.5 per 100,000 women [5].

2.1.3. The Philippines

According to the Filipino cancer registry 2005 annual report, the

incidence of cervical cancer remained stable from 1980 to 2005 [6].

The overall 5-year survival rate was 44% and mortality rate was 1 per

10,000 women. The high mortality rate is attributed to the fact that

75% of women are diagnosed at late stage disease with treatment

being frequently unavailable, inaccessible or non-affordable.

The Philippines General Hospital (PGH) has been the countrys

government tertiary center reporting the highest number of new

cervical cancer cases. In 2006, 466 new cases were reported, of

which 68% were squamous cell carcinoma, 21% adenocarcinoma,

3% adenosquamous and 8% of other histology. More than 70% of

cases presented at stage IIB disease or greater, with 4045% in

stage IIIB. Treatment-related costs for patients with cervical cancer exceeded twice the average annual income in the Philippines

with an average cost of US$3501,100 for diagnosis and pretreatment evaluation, US$1,1004,850 for surgery and US$2,1006,000

for chemoradiation) [7].

2.1.4. Thailand

In 2002, 6,243 new cervical cancer cases and 2,620 cancerrelated deaths were reported [1]. Incidence of cervical cancer from

1990 to 2000 remained constant. Squamous cell carcinoma is the

most common histopathological type accounting for 8086%, followed by adenocarcinoma/adenosquamous carcinoma accounting

for 1219% [8]. The age of women diagnosed with cervical cancer

presented as early as 20 years and peaked in women 4550 years.

Most cases are diagnosed in advanced stages of disease with 51% in

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage

II and 31% in stage III. The overall 5-year survival rates are 68.2%

Fig. 2 shows the ve most frequent HPV types in cervical cancer

in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand [10,11]. No data

are available for Vietnam. HPV-16 and 18 are the two most common

HPV types in Southeast Asia, although HPV-18 alone is relatively

more frequent compared to the type distribution estimates in the

rest of the world. This is noteworthy for Indonesia where it is the

leading HPV type in cervical cancer (52 cases of 121). It is unclear

why HPV-18 has such a high prevalence in this population [12]. The

estimate for Malaysia is based on a small number of cases (N = 23)

and there was a high number of co-infections for HPV-16 and 18,

therefore, the interpretation of these data is limited.

3.2. HPV prevalence in women with normal cytology: Indonesia,

the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam

There is a wide variation of the ve most frequent high-risk HPV

types in women with normal cytology in Southeast Asia (Fig. 3). No

data are available for Malaysia. HPV-16 remains the most frequent

type in Thailand and Vietnam, and the second most frequent type

for Indonesia and the Philippines. Although the HPV type distribution in cervical cancer for Vietnam is unknown, HPV-18 ranks

as the fourth most frequent type in women with normal cytology.

In Indonesia, HPV-51 is the most common HPV type although not

identied as one of the ve most prevalent types in cervical cancer

cases, implying its less relative importance for disease. HPV-18 is

the most frequent type in cervical cancer cases but it is not highly

prevalent in women with normal cytology in Indonesia [1113].

4. Risk factors for HPV infection and cervical cancer

The prevalence of cofactors - smoking, oral contraceptive use,

and fertility - for cervical carcinogenesis in Southeast Asia are

shown in Table 1.

4.1. Indonesia

Similar to other countries, factors that increase the risk of

cervical cancer include young age at rst intercourse, multiple

sexual partners and high parity. A cervical cancer case-control

study among women in Jakarta reported that women having more

than one sexual partner (OR: 5.83; 95% condence interval (CI):

2.9811.36) and high parity (>3) (OR: 2.7; 95%; CI: 1.554.72) were

at an increased risk for cervical cancer and women with an older age

(20 years) at rst sexual intercourse (OR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.280.85)

were at a decreased risk [12].

4.2. Malaysia

In a cross-sectional school survey of 1219 year old adolescents,

5.4% (of which 8.3% were males and 2.9% were females) reported

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

M73

Figure 2. Five most frequent HPV types in women with cervical cancer in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand [10,11].

Figure 3. High-risk HPV prevalence in women with normal cytology in Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam [13].

Table 1

Prevalence of smoking, oral contraceptive use, and total fertility in Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam

Cofactors

Indonesia

Malaysia

The Philippines

Vietnam

Sources of data: [4,28,31].

Current smoking (% of women)

Ever use of oral contraceptives (%)

Total fertility Rate (per woman)

2.9

11.6

8.1

8.0

13.2

13.4

13.2

6.3

2.8

2.8

3.0

2.2

M74

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

having had sexual intercourse [14]. Median age at rst sexual intercourse was 15 years; however, this estimate may be underreported

given that talking about sex is a culturally taboo subject in Malaysia.

However, an increasing proportion of adolescents are engaging in

premarital sex, which may reect the rapid social changes in the

country and the increased likelihood of being exposed to HPV and

other sexually transmitted infections (STI).

4.3. The Philippines

A case-control study in the Philippines reported that women

with less household amenities (a proxy for socioeconomic status),

having ever smoked, and having given birth six or more times were

at an increased risk of squamous cell carcinoma [15]. There was a

lower risk of cervical cancer with decreasing time interval from the

last Pap smear.

4.3.1. Adolescent and young adult sexual health prole

The 2005 World Health Organization-Western Pacic Regional

Ofce (WHO-WPRO) reported the mean age of sexual debut to be

1415 years [16]. In 2002, 23% of young adults had engaged in premarital sex and the number has steadily increased over the last

decade. Moreover, about 10% of young women reported that their

rst premarital sex experience was without their consent [16].

Premarital sex initiates and/or accelerates entry into marriage and the Filipino youth marry at an early age. An estimated

1.6 million young adults aged 1527 years, or 34% of the countrys

youth, have had multiple sexual partners.

The prevalence of STIs such as gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis is high among young people. Human immunodeciency

virus (HIV) infection in females occurs at a younger age group compared to males (47% of infected females are between 2029 years).

Risky sexual behavior is common among the youth. Only 26%

of sexually active adolescents admitted to having used contraceptives, with condom use as the most common method. Of the 78%

male adolescents who do not use contraceptives, 6% engage in

commercial sex. Similarly, there is an increasing number of female

adolescents engaging in unprotected commercial sex (17% in 1994

and 30% in 2002).

Among sexually active adolescents, knowledge on contraception

is poor, increasing their risk of exposure to HPV. Of those surveyed,

27% thought that the pill must be taken just prior to or straight

after sexual intercourse. Only 4% of young women can be considered knowledgeable on the subject of contraceptives and family

planning.

4.4. Thailand

Case-control studies have identied increasing number of lifetime sexual partners, having one or more STIs, smoking, high parity,

oral contraceptive use and decreasing age at rst sexual intercourse

as risk factors for cervical squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) [1719].

Furthermore, in a case-control study among monogamous women

with cervical cancer, women whose husbands rst visited commercial sex workers at 19 years of age or younger and rarely or never

used condoms were at an increased risk of SCC (OR: 2.67; 95%;

CI: 1.365.23) compared to women whose husbands never visited

commercial sex workers.

There is some evidence that diet and nutrition may inuence

cervical cancer. In a study conducted in Bangkok, high intake of

foods rich in Vitamin A, particularly in high-retinol foods, may

reduce the risk of carcinoma in situ, suggesting inhibition of the

progression to invasion [20].

In a population-based study of predominantly monogamous

women (85%), HPV positivity was associated with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) seropositivity (OR: 1.9; 95% CI: 1.22.8),

and extramarital affairs of the womans husband (OR: 1.5; 95% CI:

1.022.3). Also, HPV positivity was highest among women <25 years

of age, consistent with the increased risk of HPV infection at early

age at rst sexual intercourse [21].

4.4.1. Adolescent and young adult sexual health prole

Similar to western societies, Thai adolescents have become more

sexually active, but they are not practicing safe sex, which has led to

an increased risk of spreading STIs more rapidly [22,23]. The high

HPV prevalence in this population may be partially explained by

the transmission of STIs, often asymptomatic and under-diagnosed,

which can be associated with having multiple sexual partners. Findings from several surveys are summarized in Table 2. These results

show that the median age of sexual debut reported among adolescents age 1325 years was 16 years for males and 18 years for

females.

4.5. Vietnam

Two population-based surveys were conducted among married

women aged 1569 years in Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi [24]. HPV

prevalence was 5-fold higher in Ho Chi Minh City (10.9%) than in

Hanoi (2.0%) with a peak prevalence observed in women younger

than 25 years in Ho Chi Minh City and not Hanoi. The differences in

prevalence cannot be readily explained. However underreporting

of lifetime number of sexual partners and geographical isolation of

the north compared to the south during past decades of war could

offer a partial explanation.

Also, being nulliparous was associated with an increase risk of

HPV DNA positivity. HSV-2 seropositivity and current oral contraceptive use was associated with HPV infection in Ho Chi Minh City

but not Hanoi.

4.5.1. Adolescent and young adult sexual health prole

Recent social and economic changes in Vietnam, such as the

development of factories and other industries, have increased

the opportunity and openness for premarital sex among youths

[25]. Even though premarital sex is more common, many practice unsafe sex as condom use was perceived negatively because

it decreases pleasure and is only appropriate for prostitutes and

Table 2

Outcomes from sexual behavior surveys in Thailand

Age range surveyed

Ever had sexual intercourse

Median age at sexual debut

a

b

Source data: [22].

Source data: [23].

Secondary schoola

Students and factory

workersb

Unmarried factory

workersb

Rural North and Northeast

Thailandb

1315 years

19.1% males

4.7% females

1519 years

3% females

18 years

1325 years

75% males

6% females

16 years males

18 years females

51% males

2% females

16 years males

18 years females

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

Table 3

Outcomes from sexual behavior surveys in Vietnam

Age range

Sexually active

Used condoms (rst intercourse)

Multiple sex partners

Sex with high risk partner (drug

user or commercial sex worker)

Median age at sexual debut

a

b

General populationa

College studentb

1829 years

50% males and

females

32.8% males

10.8% females

56.7% males

9.2% females

27% males

1724 years

15% males 2% females

5% females

21.3 years males

22.7 years females

20 years

Source of data: [25].

Source of data: [23].

people engaging in extramarital affairs [25]. These data clearly suggest an increase in risk and spread of HPV and other STIs. Table 3

summarizes the results from sexual behavior surveys that report

a higher frequency of multiple partners and sexual activity with

high-risk partners.

5. Current cervical cancer screening programs

5.1. Indonesia

As part of the Female Cancer Program: See & Treat Project in

Indonesia, where women are seen, diagnosed and treated during

their single visit to the clinic, 13,923 women were screened from

October 2004 to May 2005 in Jakarta, Taskimalaya and Bali [26].

The aim of the program was to screen and treat in a one-visit setting

with visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) and immediate treatment with cryotherapy was offered for those with pre-malignant

cervical disease. The study focused on women aged 2555 years of

low socioeconomic status in rural areas. This program has successfully screened more than 50% of women with an income less than

US$3 per day, 3360% of women with only limited primary education, and about 8095% of women who had never been screened

before.

A pilot cervical cancer screening program using a single visit

approach (VIA and cryosurgery) in women aged 2549 years was

started in 2006 and is currently ongoing in six provinces: Deli Serdang (North Sumatera Province), Gowa (South Sulawesi Province),

Karawang (West Java Province), Gunung Kidul (DI Yogyakarta

Province), Kebumen (Central Java Province) and Gresik (East Java

Province). Tests are performed by doctors and midwives in community health centers with technical supervision by gynecologists and

management supervision by District and Provincial Health Ofcers

[27].

5.2. Malaysia

The cervical cancer screening program was started in 1969 using

the conventional Pap smear. Screening was later extended in 1981

to include all family planning users. In 1995 various agencies, such

as the National Population and Family Development Board (NPFDB),

private clinics and hospitals, university and army hospitals, and

non-governmental organizations like the Federation of Family Planning Association of Malaysia (FFPAM) provided Pap smear services

as part of a cancer campaign where the Pap testing was available

once every 3 years for all females aged 2065 years.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) Health Surveys 2001/2002, Pap smear coverage was only 23%. The highest Pap

smear uptake was among women aged 3039 years (36.6%) compared to women in other age groups: 1829 years (14.6%), 4049

M75

years (28.8%), 5059 years (20.9%) and 6069 years (5%) [28]. The

most recent 2003 National Guidelines on Pap Smear Screening recommended that all sexually active women aged 2065 years should

attend screening annually for two consecutive years [29]. If both

smears are normal, screening can continue every 3 years. In that

same year, the Malaysian Ministry of Health allocated 3.55 million

Malaysian ringgit for free Pap smear tests to women attending

public health facilities. The predominant screening method is conventional cytology with only a few public health services and the

private sector offering liquid-based cytology.

In 2005, public health facilities and government hospitals contributed 69% of all Pap smear tests compared to private health

facilities, which contributed only 20.6%. From 1996 to 2005, the

annual number of Pap tests ranged from 350,000 to 400,000

smears, with no signicant variation in the total number of tests

over the years.

Abnormal Pap smears and unsatisfactory ones for evaluation

accounted for 0.86% and 3.1%, respectively [30]. The 1991 Bethesda

reporting system is still in use and an effort to review the 2004 Pap

Smear Guide Book is underway.

The Ministry of Health has initiated a project to develop a

centralized database system for both public and private sectors

to determine the feasibility and cost-effectiveness of an organized screening program to reduce the incidence of cervical cancer

through a call-recall system, and to develop a national Pap smear

registry. This project also aims to increase Pap smear coverage

to 75% among women aged 2065 years. The project is currently

undertaken in Klang, Selangor and in Mersing, Johor Baharu with

completion targeted for 2011 [30].

The Malaysian Ministry of Health has taken the initiative to also

develop a National Colposcopic Training program and to evaluate

the role of VIA and cryotherapy as modalities for secondary prevention. With support from WHO, a demonstration project on VIA

and cryotherapy is in its early implementation phase in the low

socioeconomic district of Sik in the northern state of Peninsular

Malaysia.

5.3. The Philippines

The Philippine Department of Health (DOH) has advocated cervical cancer screening, but less than half (42%) of the 389 Philippine

hospitals offer screening and only 8% have dedicated screening clinics. The 2001/2002 WHO Health Survey reported a dismal 7.7% total

Pap smear coverage of Filipino women aged 1869 years [31].

Findings from a 19982000 community-based cross-sectional

study showed that knowledge on cervical cancer was inadequate

[32]. The disease was regarded as anxiety-provoking, and serious

but moderately curable. Only 23% of respondents had received a

Pap smear in which 26.6% of these women were from metropolitan

Manila and 18.5% were from other areas outside of metropolitan

Manila. The women who were more likely to have Pap smears

were married, had more children, had a family history of cancer

or perceived themselves to be at risk for the disease.

In February 2005, the Philippine DOH established a Cervical Cancer Screening Program [33] to initiate an organized nationwide

program that includes sustainable capability building, training,

education, hiring of health workers on proper VIA, Pap smear, cytology, colposcopy, and pathology. Considering low resources, VIA will

be advocated as an alternative screening method for cervical cancer, especially in primary and secondary level health care facilities

without Pap smear capability, by the governmental health and welfare sectors, non-government organizations, professional and civil

societies at the national and local levels. Pap smear with VIA triage,

colposcopy, tissue biopsy, cryosurgery and surgery treatment (total

abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) and total abdominal hysterectomy

M76

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (TAHBSO)) will be available

at the secondary levels plus radiotherapy and chemotherapy at the

tertiary level.

Recommended screening guidelines are the following: (1)

women 2555 years old will undergo VIA (with acetic acid wash)

cervical cancer screen at least once every 57 years in areas with no

Pap smear capability, otherwise Pap smear will be used; (2) acetic

acid wash (35%) will be used as the primary screening method at

local health units (rural health units; health centers), district hospitals and provincial hospitals with no Pap smear capability; (3) VIA

will be used as a triage method before Pap smear at district, provincial and regional hospitals with Pap smear capability; (4) positive

or suspicious lesion noted upon screening will be referred immediately; and (5) referral centers for cervical cancer diagnostic tests

and treatment will be established in tertiary facilities.

Although the DOH screening program is not fully implemented

as of yet, sustainability of the program will be ensured through local

nancing, e.g., subsidy from the local government unit or health

facility concerned, Philippine Health nancing, or fee for service

(user fee) scheme. A standard system of recording and reporting will be developed at service delivery facilities in collaboration

with population-based cancer registries. Periodic evaluations will

be done to assess the quality of VIA being done, and cytology-based

centers will be improved and increased as the countrys economics

improve. In order to target women about cervical cancer screenig

and services, there will be an annual public education campaign via

mass media and interpresonal communication within each health

center.

In 2006, the Johns Hopkins Program for International Education

on Gynecology and Obstetrics (JHPIEGO) Global Cervical Cancer

Prevention launched the JHPIEGO Cervical Cancer Prevention Network Program (CECAP) at the Philippine General Hospital Cancer

Institute. The aim of CECAP is to increase education and awareness about cervical cancer in Filipino women and provide them

with access and information to screening and effective treatments

through the single visit approach - VIA screening and treatment

with cryotherapy for those tested positive during the same visit-,

as well as HPV vaccination.

5.4. Thailand

Pap smears have long been used in Thailand for screening of cervical cancer but despite 40 years of implementation, there has been

little impact. In 2000, 33% of women have never been screened in

their lifetime in the Khon Kaen province. Moreover, women with

abnormal smears were likely to be lost to follow-up with primary

reasons being: (1) non-attenders did not receive an appropriate

letter of their results; (2) they did not understand the information provided in the letter; (3) they received a letter indicating that

normal test results; (4) they believed that their results were not

serious; or (5) travel-related issues [34].

There is no organized screening program in Thailand, only

opportunistic screening when attending services such as family

planning, pregnancy counseling, ante- and post-natal clinics or

sexually transmitted disease (STD) clinics [35]. Doctors require a

fee for screening, and some costs may be offset by sporadic campaigns from local health departments or charitable foundations. In

19992001, a pilot study evaluating cytology as a primary screening

test was carried out and the results later formed proposals to the

government for a national screening program. In 2002, the Ministry

of Public Health proposed the goal of screening the entire population between the ages of 3560 years at ve year intervals. In

the rst phase of screening, measures to build capacity for screening with cytology have been initiated, which include training for

nurses, cytologists, as well as additional resources for cryotherapy

and loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). This involves

providing reimbursements to provincial health authorities for each

examination performed. The program also included public health

education to improve knowledge and awareness on cervical cancer,

education and training of health care workers, competency-based

training for nurse providers, quality assurance and information

management systems.

The 2005 preliminary report showed Pap smear coverage of

67.6% (405,756 women out of 0.6 million women targeted). Of those

screened, 1.6% had abnormal cytology and 0.04% had pre-invasive

and invasive cervical cancer. Among the 0.1 million women targeted for the single visit approach with VIA-cryotherapy, 47,418

women were screened and 810% were offered cryotherapy. The

competency of nurse providers who performed cryotherapy was

satisfactory and women were highly satised with the single visit

approach [34].

Although, the government backed program is largely based on

cytology, other alternative screening strategies considered in Thailand include are (a) VIA-positive but unsuitable for cryotherapy;

or (b) suspected for cervical cancer. Other screening methods or

strategies that are being considered include 1) self-sampling to

increase coverage and compliance, particularly in rural areas where

adequate numbers of physicians or medical personnel may not be

available; 2) mobile clinics for screening, which can reduce the geographic barriers for participation in screening; and 3) increasing the

capacity for HPV testing as an adjunct to cytology. Patients with

abnormal pap smear are also referred to catchment hospitals for

further management. [35].

5.5. Vietnam

Between 1999 and 2004, population-based Pap smear screening

was established in 10 districts in southern and central Vietnam in

women 3055 years of age, in collaboration with the Viet/American

Cervical Cancer Prevention Project [36]. All screening and treatment services are performed by public sector health providers.

In certain districts, decreasing programmatic quality has been

observed with inadequate follow-up of screen-positive women

and poor laboratory performance. In a systems analysis of program deciencies in Vietnam, it was revealed that the target

age group for reproductive health services and screening services barely overlapped, and with the country transitioning into

a market economy, private-sector health provider incomes outpaced increases in public sector incomes, producing incentives

against Pap screening in the public sector. Moreover, this leaves

fewer incentives to follow-up women with cytological abnormalities [36]. From the perspective of the cytotechnologist, they are

often allocated insufcient time to perform their readings of Pap

smears which adversely affects the detection rates of cervical

neoplasia.

Coverage has not exceeded 40% in any Vietnamese district where

population-based Pap screening is currently performed. In the

20012002 WHO Health Survey, total Pap coverage of the general

population of women aged 1869 years was estimated to be 4.9%

[37]. There has been little political will in supporting cervical cancer prevention efforts in Vietnam when there are other competing

health priorities [36].

Recently, the National Target Cancer Control Program of Vietnam has been approved by the Vietnamese Government and will

begin in 2008 and continue through 2010 to 2020 [36,38]. The general objectives of the program are to reduce cancer incidence and

mortality rates, as well as to improve the quality of life for cancer

patients. The specic objectives of the program are: (1) to control

risk factors of cancer such as smoking and other environmental factors; (2) to monitor prevalence, incidence and mortality of cancers

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

such as breast, lung and cervical cancer; (3) to design and conduct

models for early detection of cancer in communities; (4) to improve

awareness on cancer prevention in communities and to strengthen

the capacity of its health care staff at different levels; (5) to establish pain relief and palliative care units at current prevention and

control cancer hospitals; and (6) to design and implement models

for taking care of cancer patients in communities.

Cervical cancer is one of the most common cancers in Vietnamese women and is one important issue that should be

addressed by the National Target Program. Such activities include

screening for early detection, new techniques for diagnosis and

treatment of cervical cancer and formation of a national network

for cancer prevention. The public health approach is to improve

awareness on cervical cancer, train health care staff and improve

health promotion in the communities.

Furthermore, Vietnam has proposed a National Strategy for Cancer Control up to 2020 with the objectives of reducing cervical

cancer mortality rate and decreasing the proportion of advanced

stage cancers from 80% to 50%. The Pap test has been the main

method of screening but VIA is also being explored. However, the

Ministry of Health in collaboration with PATH through a project

supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, will implement activities to strengthen secondary cervical prevention that

will include a pilot study evaluating new simple and affordable

screening technologies along with VIA.

6. Cervical cancer prevention and HPV vaccination

6.1. Indonesia

The Leiden University Medical Center (LUMC) European Union

consortium sponsored an HPV pilot program in Indonesia (Jakarta

and Bali). A clinical trial will be conducted among 200 women

examining the feasibility of simple, low-cost delayed type hypersensitivity (DTH) skin test to detect HPV-immune reactivity versus

HPV-16 [39]. This will help determine the proportion exposed to

HPV-16 and provide data as to when the most appropriate age

would be for vaccination.

6.2. Malaysia

The Malaysia Drug Authority approved the use of the quadrivalent HPV vaccine (Gardasil , Merck & Co., Inc., Whitehouse Station,

NJ, USA) in October 2006, but its use is exclusively in private health

centers. Many issues regarding vaccine use remain unanswered

including the cost-effectiveness and long-term benets to a population where the burden of type-specic HPV infection is unknown.

Also unknown is the duration of protection by HPV vaccination, the

need for booster doses, vaccine efcacy in older women, and public perception about the prevention of an STD among sexually nave

girls and boys.

The Department of Community Health at the National University of Malaysia is currently conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis

of HPV vaccination in government hospitals and completion is

expected in 2008. Other studies on the prevalence of HPV and

invasive cervical cancer are also underway.

A National Immunization Technical Committee under the Disease Control Division of the Malaysian Ministry of Health has

been given the responsibility to study and make recommendations

on the role of the HPV vaccine in Malaysia by 2009. Currently,

the Ministry of Health, non-governmental organizations (NGOs)

and pharmaceutical companies are actively involved in increasing

knowledge on HPV and cervical cancer using mass media, media

electronics, posters and pamphlets.

M77

6.3. The Philippines

6.3.1. Vaccine acceptability

Two prophylactic HPV vaccines are registered and marketed in

the Philippines that prevent against HPV types -6, 11, 16 and 18

(Gardasil ) and against types -16 and 18 (CervarixTM , GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals, Rixensart, Belgium).

To determine the acceptability of HPV vaccines in the Philippines, a focus group discussion and exploratory survey was initiated

with 195 women with daughters aged 1215 years recruited

from the Philippines General Hospital Obstetrics-Gynecology charity clinics regarding their knowledge and attitude towards HPV

vaccination [40]. Only 14.4% of those surveyed had heard of

HPV with television being the main source of information and

doctors being the second. Approximately 56.4% of the women

identied HPV as an STD and only 31.8% associated it to the

development of cervical cancer. The HPV vaccine was acceptable to 75.4% of women because it would prevent illness, and

of these more than half (55%) thought it should be given prior

to sexual activity, while 27% thought it should be administered

between 1215 years of age. Many thought that men should

also receive the vaccine to prevent them from infecting their

partners.

Acceptability of the vaccine was higher when respondents were

recruited from the Philippines General Hospital general wards. In

ten mothers aged 2143 years, nine mothers would allow their

children to receive the HPV vaccine even if only one out of ten

knew about it. Likewise, in ten pediatric patients aged 1019 years,

seven would like to receive the vaccine. For those non-acceptors,

the reasons cited were young age, painful injection and sexual inexperience.

Another concern against HPV vaccination is the issue that it

could promote or encourage unsafe sexual behavior among adolescents. However the predominant reason for non-acceptance of

the vaccine is its high cost.

6.3.2. Vaccination policy and delivery

The Philippine Department of Health has not formulated a

policy on HPV vaccination, perhaps stemming from the most controversial concern that such formal policy could have a negative

impact on the sexual behavior of the youth. However, it may be

worthwhile to consider the impressions from the Report Card

HIV Prevention for Girls and Young Women (the Philippines)

[41] as a framework for a prospective Philippine HPV Vaccination Program: (1) minimum legal age at marriage is 18 years;

(2) sex work is illegal but tolerated and common in many areas;

(3) there is no budget allocation for sexual and reproductive

health services, and where such services exist, they tend to be

based on marital status than on age-married youths are regarded

as adults for whom services are acceptable; with discrimination against those who are not married; (4) STI treatment is not

free, neither is voluntary counseling and testing; and available

data suggest that fewer women access STI testing compared to

men.

More young people engage in sex at an earlier age and

often without contraceptions. These issues call for a comprehensive evidence-based sexual and reproductive health program

that takes into consideration the needs of the youth. It should

have a clear guideline, which is national in scope that will

provide young people with access to health services. Commitment to womens health should incorporate HPV vaccination

into the educational curriculum with learning modules to adequately train teachers. The success of HPV prevention for

girls and young women will depend on the political will of

the government, as well as the support from relevant inter-

M78

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

governmental and non-government organizations (NGOs), and

donors.

6.3.3. Research on deployment of HPV vaccination

The current DOH cervical screening program includes Pap

smear, VIA, colposcopy and tissue biopsy in women aged 2555

years [21]. If HPV vaccination is integrated into this program, the

target population should be extended to include girls and women

aged 1124 years, and those who have not been vaccinated or have

not completed the full course.

A national registration system that is linked to a populationbased tumor registry could also be implemented to identify a cohort

of vaccinated women who can be followed up and compared to

unvaccinated cervical cancer cases identied from the tumor registry.

Introduction of an HPV vaccination program can be done

in phases across different regions of the archipelago through

demonstration research projects. Once the program is operational,

evaluation of its short and long-term effects can be done, specifically to evaluate: (1) the knowledge, attitudes, practices and

acceptability of vaccination of the target female population and

health providers before, during and after implementation to capture behavioral changes and caveats to improve the program and

to assess the effectiveness of regular information, education and

communication campaigns; (2) the technical issues on vaccine use

in the eld-vaccine storage, handling, and distribution as well as

a nationwide registry; (3) compliance with the three dose vaccine

regimen; (4) the health economic impact of vaccination with regard

to efcacy and long-term safety, and to include the use of new

vaccines; (5) the effects on sexual-reproductive health demographics of Filipino adolescents; (6) the effects on cervical screening,

although the recommendation for screening has not changed for

women who have been vaccinated; and (7) the impact of HPV vaccination on the incidence of cervical cancer. Evaluation of the HPV

vaccination program should be a spearheaded by the government

with collaborative support from local agencies and international

research organizations.

The DOH has not received a proposal for the inclusion of HPV

vaccination in its relevant public health programs such as the

Expanded Program for Immunization, Womens Health and Safe

Motherhood Program and Cancer Control Program. School-based

programs may be the best way to reach the target youth. In this

regard, the Department of Education, Culture and Sports (DepEd)

may be involved in the HPV vaccination campaign. DepEds Population Education Program includes a curriculum on responsible

sexual behavior and reproductive health care commencing at the

5th grade elementary school level and up to college. To cover

the out-of-school youths that comprise 15% of the 724 year age

group, community-based programs should be the most appropriate

approach.

6.4. Thailand

The quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil ) has been licensed in

Thailand since March 2007. It is recommended for children and adolescents 917 years of age and women up to age 26 years. Currently,

cost-effectiveness models of HPV vaccination in cancer prevention

and control programs are being studied. A registry of girls and

women who receive the vaccine has been suggested.

6.4.1. Vaccination policy and delivery

Health promotion programs are mostly implemented by public

health sector agencies and NGOs using various approaches including health behavior modication for positive health impact, social

environment modication, congregation for self-help among peo-

ple with the same health problems and individual and community

encouragement for self-care. Some of the implemented programs

and activities are as follows: campaigns on smoking cessation,

physical activity promotion, healthy diet consumption, and healthy

behavior promotion. To date, there is no national HPV vaccination

policy in Thailand.

6.5. Vietnam

6.5.1. Vaccine acceptability

In a recent survey of mothers on general vaccine attitudes and

attitudes toward HPV vaccination, 11% were aware of the HPV vaccine, 94% believed the vaccine will be effective and 90% disagreed

that their daughter would engage in early sex if they were vaccinated [32]. Over 90% of mothers favored vaccination of their

daughters and 95% indicated that recommendation from their doctors would be important for their decision-making process.

Many questions and program concerns have to be addressed in

this country before any vaccine can be effectively used. It is important to ensure equitable access to HPV vaccines in order to attain

high coverage of adolescents before they become sexually active.

For successful implementation of HPV vaccination, a pilot demonstration in at least one community should be done before extending

it nationwide. The health system should be strengthened to adopt

the vaccine, and engagement and support from various stakeholders will be important.

6.5.2. Potential barriers to HPV vaccination

The lack of knowledge on cervical cancer and HPV among the

Vietnamese communities prohibit participation in a vaccination

program. Since the vaccine targets adolescents, this will need to

be integrated into the countrys national immunization program.

In addition, the cost of the vaccine is high which will hinder those

with a low income accessibility. The government still has to discern whether investment on vaccination or nationwide screening

is best.

6.5.3. Vietnam demonstration project on cervical cancer vaccine

A cervical cancer vaccine project supported by PATH will be

conducted in the province of Thaibinh and Dongthap in 2008. The

aim of the project is to identify the most cost-effective strategy

for reaching 1114 year old girls with the HPV vaccine. The results

will be compared between urban and rural areas, and will answer

whether intensive campaigns or minimal efforts should be put into

the campaign.

7. Conclusions

Cervical cancer has remained a leading cancer in women in

Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam. For

close to ve decades, standard Pap screening has been available

for opportunistic screening in Southeast Asia, but organized programs have yet to be implemented, largely due to high costs and

needs for infrastructure within the health system. Recently, alternatives to Pap smear screening have been introduced in Indonesia,

Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand, where VIA-cryotherapy

programs are being actively evaluated. HPV vaccination has been

approved in these ve countries with new efforts to integrate primary prevention at the forefront of cervical cancer control. The

socio-cultural, economic and political turmoil and upheavals in this

region may inuence the delivery of vital cervical cancer prevention

campaigns.

E.J. Domingo et al. / Vaccine 26S (2008) M71M79

Disclosed potential conict of interest

EJD: Advisory Board (GlaxoSmithKline, Merck Sharp & Dohme).

CAN: Consultant (Roche Philippines, Inc.); Stockholder (Roche

Philippines, Inc.).

References

[1] Ferlay J, Bray F, Pisani P, Parkin D. GLOBOCAN 2002. Cancer Incidence, Mortality

and Prevalence Worldwide. IARC CancerBase No.5, version 2.0 IARCPress, Lyon,

2004.

[2] Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, Storm H, Ferlay J, Heanue M, et al. Cancer

Incidence in Five Continents, Vol. IX. IARC Scientic Publications No. 160. Lyon:

IARC Press, 2007.

[3] Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR, et al. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents, Vol.

I to VIII. IARC Cancer Base No.7. Lyon: IARC Press, 2005.

[4] Castellsagu X, de Sanjose S, Aguado T, Louie KS, Bruni L, Munoz

J, et al. HPV

and Cervical cancer in the World. 2007 Report. WHO/ICO Information Centre

on HPV and Cervical Cancer (HPV Information Centre). Vaccine 2007; Vol. 25

Supp. 3. Available at: www.who.int/hpvcentre (last accessed: April 2008).

[5] The Second Report of National Cancer Registry. Cancer Incidence in Malaysia

2003. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: National Cancer Registry, 2003.

[6] Philippine Cancer Society Manila Cancer Registry and the Department of Health

Rizal Cancer Registry. Philippine Cancer Facts and Estimates. PCSI, 2005.

[7] UP-PGH Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology Staff Conference. Section of

Gynecologic Oncology Annual Report 2006, 2006.

[8] Deerasamee S, Martin N, Sontipong S, Sriamporn S, Sriplung H. Cancer in Thailand. Lyon: IARC Press; 1999. Technical Report No. 34.

[9] Sriplung H., Sontipong S, Martin N. Cancer in Thailand Vol. III, 19951997. Report

No.: 49. Bangkok: National Cancer Institute; 2003.

[10] Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, Keys J, Franceschi S, Winer R, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical

lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer 2007;121(3):62132.

[11] Sriamporn S, Snijders PJ, Pientong C, Pisani P, Ekalaksananan T, Meijer CJ, et al.

Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer from a prospective study in Khon

Kaen, Northeast Thailand. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16(1):2669.

[12] de Boer MA, Vet JN, Aziz MF, Cornain S, Purwoto G, van den Akker BE, et al.

Human papillomavirus type 18 and other risk factors for cervical cancer in

Jakarta, Indonesia. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16(5):180914.

[13] de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Munoz N, et al.

Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect

Dis 2007;7(7):4539.

[14] Lee LK, Chen PC, Lee KK, Kaur J. Premarital sexual intercourse among adolescents in Malaysia: a cross-sectional Malaysian school survey. Singapore Med J

2006;47(6):47681.

[15] Ngelangel C, Munoz N, Bosch FX, Limson GM, Festin MR, Deacon J, et al. Causes

of cervical cancer in the Philippines: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst

1998;90(1):439.

[16] Sexual & Reproductive Health of Adolescents & Youths in the Philippines - A

Review of Literature & Projects 19952003. Manila: World Health OrganizationWestern Pacic Regional Ofce (WHO-WPRO) 2005; 913.

[17] Chichareon S, Herrero R, Munoz N, Bosch FX, Jacobs MV, Deacon J, et al. Risk

factors for cervical cancer in Thailand: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst

1998;90(1):507.

[18] Ishida WS, Singto Y, Kanjanavirojkul N, Chatchawan U, Yuenyao P, Settheetham

D, et al. Co-risk factors for HPV infection in Northeastern Thai women with

cervical carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2004;5(4):3836.

[19] Thomas DB, Qin Q, Kuypers J, Kiviat N, Ashley RL, Koetsawang A, et al.

Human papillomaviruses and cervical cancer in Bangkok. II. Risk factors

for in situ and invasive squamous cell cervical carcinomas. Am J Epidemiol

2001;153(8):7329.

M79

[20] Shannon J, Thomas DB, Ray RM, Kestin M, Koetsawang A, Koetsawang S, et al.

Dietary risk factors for invasive and in-situ cervical carcinomas in Bangkok,

Thailand. Cancer Causes Control 2002;13(8):6919.

[21] Sukvirach S, Smith JS, Tunsakul S, Munoz N, Kesararat V, Opasatian O, et al.

Population-based human papillomavirus prevalence in Lampang and Songkla,

Thailand. J Infect Dis 2003;187(8):124656.

[22] Kanato M, Saranrittichai K. Early experience of sexual intercoursea risk factor

for cervical cancer requiring specic intervention for teenagers. Asian Pac J

Cancer Prev 2006;7(1):1513.

[23] Brown AD, Jejeebhoy SJ, Yount KM. Sexual relations among young people in

developing countries; evidence from WHO case studies. Geneva: Department

of Reproductive Health and Research, Family and Community Health, World

Health Organization; 2001.

[24] Pham TH, Nguyen TH, Herrero R, Vaccarella S, Smith JS, Nguyen Thuy TT, et al.

Human papillomavirus infection among women in South and North Vietnam.

Int J Cancer 2003;104(2):21320.

[25] Duong CT, Nguyen TH, Hoang TT, Nguyen VV, Do TM, Pham VH, et al. Sexual

Risk and Bridging Behaviors Among Young People in Hai Phong, Vietnam. AIDS

Behav 2007;12(4):64351.

[26] International ght against cervical cancer. Female Cancer Program 2005. Available at: http://www.femalecancerprogram.org/FCP/ (last accessed: April 2008).

[27] Noviani R. 2-2-0008. Personal Communication.

[28] WHO. World Health Survey 2001/2002. Malaysia. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

[29] The Malaysian Guidebook for PAP Smear Screening. Malaysia: Division of Family

Health Development, Ministry of Health, 2004.

[30] Proposal paper of pilot project on community-based cervical cancer screening

by call-recall system, Family Health Development Division. Ministry of Health

Malaysia 2001:2885.

[31] WHO World Health Survey 2001/2002. Philippines. Geneva: World Health

Organization, 2002.

[32] Dinh TA, Rosenthal SL, Doan ED, Trang T, Pham VH, Tran BD, et al. Attitudes of

mothers in Da Nang, Vietnam toward a human papillomavirus vaccine. J Adolesc

Health 2007;40(6):55963.

[33] Administrative Order No. 20052006. Establishment of a cervical cancer

screening program. Department of Health, Republic of the Philippines 2005

February 10. Available at: http://www.doh.gov.ph/ (last accessed: April 2008).

[34] Linasmita V. Cervical cancer screening in Thailand. FHI-satellite meeting on the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer in the Asia

and the Pacic region. Bangkok, Thailand, February 2006. Available at:

http://www.tgcsthai.com/index2.php?option=com content&do pdf=1&id=46

(last accessed: April 2008).

[35] Sriamporn S, Khuhaprema T, Parkin DM. Cervical cancer screening in Thailand:

an overview. J Med Screen 2006;13(Suppl. 1):S3943.

[36] Suba EJ, Murphy SK, Donnelly AD, Furia LM, Huynh ML, Raab SS. Systems

analysis of real-world obstacles to successful cervical cancer prevention in

developing countries. Am J Public Health 2006;96(3):4807.

[37] WHO. World Health Surveys 2001/2002. Laos. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002.

[38] The National Target Program on cancer control and cancer prevention. Ministry

of Health, Vietnam 2007.

[39] HPV Pilot Action Indonesia PAHPV-1 (4/15/2004-8/14/2005). The IST

World portal: Internet Communication. Available at: http://www.istworld.org/ProjectDetails.aspx?ProjectId=6fea052aa157419da157d4136c549d

79 (last accessed: April 2008).

[40] Zalameda-Castro CR, Domingo EJ. A hospital-based study on the knowledge and

attitude of mothers of adolescents in the Philippine General Hospital regarding

Human Papillomavirus Infection and its potential vaccine. Philippine J Gynecol

Oncol 2007;4(1):16.

[41] HIV prevention for girls and young women. Report Card Philippines. UNFPA:

Population issues: Preventing HIV infection: HIV Prevention for Girls and

Young Women: Report Cards 2006. Available at: http://www.unfpa.org/

hiv/reportcard.htm (last accessed: April 2008).

You might also like

- Research Proposal On Prevalence of PneumoniaDocument26 pagesResearch Proposal On Prevalence of Pneumoniasolomon demissew62% (13)

- Case Study Hpi SamplesDocument10 pagesCase Study Hpi SamplesMihai DohotariuNo ratings yet

- Thimerosal Content of US Vaccines 02-04Document3 pagesThimerosal Content of US Vaccines 02-04Diane StierNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Research 1Document9 pagesCervical Cancer Research 1tivaNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer MalaysiaDocument12 pagesCervical Cancer MalaysiaAlbina Mary RajooNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Perception of Female Nursing Students About Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Cervical Cancer and Attitudes Towards HPV VaccinationDocument18 pagesKnowledge and Perception of Female Nursing Students About Human Papilloma Virus (HPV), Cervical Cancer and Attitudes Towards HPV VaccinationpangaribuansantaNo ratings yet

- Immunization of Cervical CancerDocument14 pagesImmunization of Cervical CancerAasif KohliNo ratings yet

- WA0054mmmDocument4 pagesWA0054mmmA HNo ratings yet

- Mini CaseDocument4 pagesMini CaseSheryl Anne GonzagaNo ratings yet

- Conduct Organized Campaign On Cervical Cancer ScreDocument3 pagesConduct Organized Campaign On Cervical Cancer Scregivelyn olorvidaNo ratings yet

- Felix Mpachika - CHAPTER 1Document8 pagesFelix Mpachika - CHAPTER 1sekani mondwechilengaNo ratings yet

- Intl J Gynecology Obste - 2021 - WilailakDocument5 pagesIntl J Gynecology Obste - 2021 - WilailakKalaivathanan VathananNo ratings yet

- Case Study of Cervical Cancer Stage III (Final)Document82 pagesCase Study of Cervical Cancer Stage III (Final)DRJC94% (33)

- A Synthesis Paper About Breast, Testicular and Cervical Cancer in The PhillipinesDocument3 pagesA Synthesis Paper About Breast, Testicular and Cervical Cancer in The Phillipinesjanna mae patriarcaNo ratings yet

- Cancer CervixDocument7 pagesCancer Cervixkalpana gondipalliNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Profile of Gynecologic Breast Cancer inDocument3 pagesEpidemiological Profile of Gynecologic Breast Cancer indomi kalondaNo ratings yet

- Cervical CA Proposal Jan152010Document21 pagesCervical CA Proposal Jan152010redblade_88100% (2)

- Cervical Ca R. ProposalDocument7 pagesCervical Ca R. ProposalRobel HaftomNo ratings yet

- Keywords: Human Papillomavirus Vaccine, Efficacy, Safety, Phase III Randomized TrialsDocument10 pagesKeywords: Human Papillomavirus Vaccine, Efficacy, Safety, Phase III Randomized TrialsBassment MixshowNo ratings yet

- Meeting The Challenges of Breast Cancer 290411Document40 pagesMeeting The Challenges of Breast Cancer 290411Presentaciones_FKNo ratings yet

- Neenu BabyDocument24 pagesNeenu BabyNeenu PauloseNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 of Research Study PDFDocument3 pagesChapter 1 of Research Study PDFAasif KohliNo ratings yet

- Current Status of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) and Screening For Cervical Cancer in Countries at Different Levels of DevelopmentDocument7 pagesCurrent Status of Knowledge, Attitude and Practice (KAP) and Screening For Cervical Cancer in Countries at Different Levels of DevelopmentHuzaifa SaeedNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer Main WorkDocument41 pagesCervical Cancer Main WorkocmainNo ratings yet

- Cervical CancerDocument75 pagesCervical CancerJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument48 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument58 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument46 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument47 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument54 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Scientific Research: OncologyDocument3 pagesInternational Journal of Scientific Research: OncologyDr SrigopalNo ratings yet

- Asia Oceania GuidelinesDocument25 pagesAsia Oceania GuidelinesKaily TrầnNo ratings yet

- A Review On Cervical Cancer VaccinationDocument3 pagesA Review On Cervical Cancer VaccinationKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Pamj 22 26Document8 pagesPamj 22 26Yosie Yulanda PutraNo ratings yet

- Trends and Determinants of Maternal Mortality in Mizan-Tepi University Teaching and Bonga General Hospital From 2011 - 2015: A Case Control StudyDocument8 pagesTrends and Determinants of Maternal Mortality in Mizan-Tepi University Teaching and Bonga General Hospital From 2011 - 2015: A Case Control StudyTegenne LegesseNo ratings yet

- Cervical Cancer FACTSHEET April 2011Document3 pagesCervical Cancer FACTSHEET April 2011Daomisyel LiaoNo ratings yet

- Current Global Status & Impact of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Implications For IndiaDocument12 pagesCurrent Global Status & Impact of Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Implications For IndiaPrasanna BabuNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Study On Breast Cancer Associated Risk Factors and Screening Practices Among Women in Mbaise Imo State, NigeriaDocument8 pagesEpidemiological Study On Breast Cancer Associated Risk Factors and Screening Practices Among Women in Mbaise Imo State, NigeriaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Practice Bulletin: Endometrial CancerDocument21 pagesPractice Bulletin: Endometrial CancerDivika ShilvanaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2352578919300554 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S2352578919300554 Mainkarenelijah147No ratings yet

- FIGO CANCER REPORT 2021 - Cancer of The Cervix Uteri 2021 Update 2021Document17 pagesFIGO CANCER REPORT 2021 - Cancer of The Cervix Uteri 2021 Update 2021amrodriguez9No ratings yet

- Ca ServixDocument30 pagesCa ServixDanang MustofaNo ratings yet

- CANCER Preventing Cervical CancerDocument4 pagesCANCER Preventing Cervical CancerLeonardo Rodríguez BottacciNo ratings yet

- Manuskrip PI169418064519870645Document19 pagesManuskrip PI169418064519870645Bibup GhaziyahNo ratings yet

- Genotypes and Associated Risk Levels of Human Papilloma Virus Among Female Patients Attending Rabuor Sub County Hospital, KisumuDocument13 pagesGenotypes and Associated Risk Levels of Human Papilloma Virus Among Female Patients Attending Rabuor Sub County Hospital, KisumuMJBAS JournalNo ratings yet

- Tatalaksana Dan Pencegahan - Hal 29-38 - Cancer of The Cervix Uteri 2021 UpdateDocument17 pagesTatalaksana Dan Pencegahan - Hal 29-38 - Cancer of The Cervix Uteri 2021 UpdateAl-Amirah ZainabNo ratings yet

- Only One in Five Indonesian Women Are Aware of Cervical Cancer ScreeningDocument3 pagesOnly One in Five Indonesian Women Are Aware of Cervical Cancer Screeningedi_wsNo ratings yet

- Update of Breast Cancer Profile in IndonesiaDocument7 pagesUpdate of Breast Cancer Profile in IndonesiaYona TarunaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude and Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Among HIV Positive Women Visiting Kampala International University Teaching HospitalDocument10 pagesKnowledge, Attitude and Uptake of Cervical Cancer Screening Among HIV Positive Women Visiting Kampala International University Teaching HospitalKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- FIGO 2018 - Cervical CADocument15 pagesFIGO 2018 - Cervical CAJP RecioNo ratings yet

- Malaria in Pregnancy - A Community-Based Study On The Knowledge, Perception, andDocument15 pagesMalaria in Pregnancy - A Community-Based Study On The Knowledge, Perception, andsemabiaabenaNo ratings yet

- Assignment No 1 bt502 SeminarDocument15 pagesAssignment No 1 bt502 SeminarMashal WakeelaNo ratings yet

- Figo 2018Document15 pagesFigo 2018EJ CMNo ratings yet

- Prospects and Potential For Expanding Women's Oncofertility Options - Gabriella TranDocument18 pagesProspects and Potential For Expanding Women's Oncofertility Options - Gabriella TrannurjNo ratings yet

- Iva Screening2Document9 pagesIva Screening2ponekNo ratings yet

- Tesfaw, Alebachew, Tiruneh - 2020 - Why Women With Breast Cancer Presented Late To Health Care Facility in North-West Ethiopia A QualitaDocument15 pagesTesfaw, Alebachew, Tiruneh - 2020 - Why Women With Breast Cancer Presented Late To Health Care Facility in North-West Ethiopia A QualitaABDUL MUHAIMINNo ratings yet

- Health Belief Model On The Determinants of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination in Women of Reproductive Age in Surakarta, Central JavaDocument11 pagesHealth Belief Model On The Determinants of Human Papilloma Virus Vaccination in Women of Reproductive Age in Surakarta, Central Javaadilla kusumaNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer Awareness Among Pregnant Women at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western UgandaDocument12 pagesBreast Cancer Awareness Among Pregnant Women at Hoima Regional Referral Hospital, Western UgandaKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument11 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentMihaela AndreiNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Karnataka, Bangalore Annexure - Ii Name of The Candidate and Address (In Block Letters)Document18 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Karnataka, Bangalore Annexure - Ii Name of The Candidate and Address (In Block Letters)subiNo ratings yet

- Sexuallytransmittedhuman Papillomavirus: Update in Epidemiology, Prevention, and ManagementDocument22 pagesSexuallytransmittedhuman Papillomavirus: Update in Epidemiology, Prevention, and Managementerikglu2796No ratings yet

- Breast Cancer in Nigeria: Diagnosis, Management and ChallengesFrom EverandBreast Cancer in Nigeria: Diagnosis, Management and ChallengesNo ratings yet

- Kanker ServiksDocument308 pagesKanker ServiksponekNo ratings yet

- Sadiq KhanDocument5 pagesSadiq KhanponekNo ratings yet

- Checklist Dmpa EnglishDocument3 pagesChecklist Dmpa EnglishponekNo ratings yet

- Scientific Schedule: Alarm Course Day 1Document11 pagesScientific Schedule: Alarm Course Day 1ponekNo ratings yet

- Preclinical Condition MagementDocument27 pagesPreclinical Condition MagementponekNo ratings yet

- Analisis Pengendalian Alkes Farmasi Di Rs Pangkal PinangDocument12 pagesAnalisis Pengendalian Alkes Farmasi Di Rs Pangkal PinangponekNo ratings yet

- CRYOTERAPI See&Treat GatotDocument20 pagesCRYOTERAPI See&Treat GatotponekNo ratings yet

- CHN & CD Pre-Board TestDocument6 pagesCHN & CD Pre-Board TestAndrea Broccoli100% (1)

- Health Check Consent FormDocument4 pagesHealth Check Consent Formaxenic04No ratings yet

- Health For All-ImpDocument54 pagesHealth For All-ImpSathish KumarNo ratings yet

- Polio Eradication: Pulse Polio Programme: A.Prabhakaran M.SC (N), Tutor, VMACON, SalemDocument13 pagesPolio Eradication: Pulse Polio Programme: A.Prabhakaran M.SC (N), Tutor, VMACON, SalemPrabhakaran Aranganathan100% (3)

- Indian Immunization Programme: A Literature Review 2012Document44 pagesIndian Immunization Programme: A Literature Review 2012Raajan K SharmaNo ratings yet

- Nanotechnology and VaccinesDocument24 pagesNanotechnology and VaccinespranchishNo ratings yet

- Multifibren UDocument6 pagesMultifibren UMari Fere100% (1)

- Diphtheria HandoutsDocument8 pagesDiphtheria HandoutsRachelle Mae DimayugaNo ratings yet

- Landasan Teori Tetanus GeneralisataDocument22 pagesLandasan Teori Tetanus GeneralisataadityaNo ratings yet

- Fake Vaccines in June 2016Document1 pageFake Vaccines in June 2016Herlinda SoefiyantiNo ratings yet

- Most Common MedsDocument13 pagesMost Common MedsMaria Zenaida BonoanNo ratings yet

- Science & Health Writing (English, Sample) Dengue Kills TitleDocument2 pagesScience & Health Writing (English, Sample) Dengue Kills TitleValyn Encarnacion100% (1)

- Whooping Cough Letter Shahala Middle SchoolDocument2 pagesWhooping Cough Letter Shahala Middle SchoolKGW NewsNo ratings yet

- "Expanded Program On Immunization": Angeles University FoundationDocument12 pages"Expanded Program On Immunization": Angeles University FoundationJaillah Reigne CuraNo ratings yet

- Sample CDC Whistleblower Letter For RepublicansDocument3 pagesSample CDC Whistleblower Letter For RepublicansmarathonjonNo ratings yet

- Rabies Prevention and ControlDocument9 pagesRabies Prevention and ControlJames RiedNo ratings yet

- Baby Vaccination ProgramDocument1 pageBaby Vaccination Programplainspeak100% (1)

- Battisti Exercices PediatrieDocument197 pagesBattisti Exercices Pediatrieahkrab100% (1)

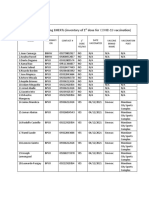

- Barangay Mantuyong Bherts (Inventory of 1 Dose For Covid-19 Vaccination)Document1 pageBarangay Mantuyong Bherts (Inventory of 1 Dose For Covid-19 Vaccination)Barangay CentroNo ratings yet

- Quiz Hand SlidesDocument10 pagesQuiz Hand SlidesSushant SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Chappuis, Neonatal Immunity and Immunisation in Early Age. Lesons From Veterinary MedicineDocument5 pagesChappuis, Neonatal Immunity and Immunisation in Early Age. Lesons From Veterinary MedicineNath BixoNo ratings yet

- Acs Ca3 BookDocument69 pagesAcs Ca3 BookchrisNo ratings yet

- Strachan Hygiene HypotheseDocument9 pagesStrachan Hygiene HypotheseRikko HudyonoNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet Jan 8 PDFDocument2 pagesPamphlet Jan 8 PDFRouetchen AshleeNo ratings yet

- Fever in Infants and Children: Health NotesDocument3 pagesFever in Infants and Children: Health NotesHanso LataNo ratings yet

- Hubungan Antara Faktor Gender Dan Usia Terhadap Efektivitas Vaksinasi Hepatitis B Pada Mahasiswa Jurusan Keperawatan Di Poltekkes SurakartaDocument4 pagesHubungan Antara Faktor Gender Dan Usia Terhadap Efektivitas Vaksinasi Hepatitis B Pada Mahasiswa Jurusan Keperawatan Di Poltekkes SurakartaadindadpyanaNo ratings yet

- Moving Target Vaccines Thimerosol and AutismDocument25 pagesMoving Target Vaccines Thimerosol and AutismcirclestretchNo ratings yet