Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Texto Aalbers

Texto Aalbers

Uploaded by

Bruno Leonardo BarcellaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Texto Aalbers

Texto Aalbers

Uploaded by

Bruno Leonardo BarcellaCopyright:

Available Formats

Virtual special issue editorial essay

Urban Studies

124

Urban Studies Journal Limited 2016

Virtual special issue editorial essay: Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

The shitty rent business: Whats DOI: 10.1177/0042098016638975

usj.sagepub.com

the point of land rent theory?

Callum Ward and Manuel B Aalbers

KU Leuven, Belgium

Abstract

In this introduction to a virtual special issue on land rent, we sketch out the history of land rent

theory, encompassing classical political economy, Marxs political economy, the marginalist turn

and subsequent foundations for urban economics, and the Marxist consensus around rent theory

during geographys spatial turn. We then overview some of the contemporary strands of litera-

ture that have developed since the break down of this consensus, namely political economy

approaches centred on capital-switching, institutionalism of various stripes, and the rent gap the-

ory. We offer a critical urban political economy perspective and a particular set of arguments run

through the review: first, land is not the same as capital but has unique attributes as a factor of

production which require a separate theorisation. Second, since the 1970s consensus around land

rent and the city dissipated, the critical literature has tended to take the question of why/how the

payment exists at all for granted and so has ignored the particular dynamics of rent arising from

the idiosyncrasies of land. Amongst the talk of an Anthropocene and planetary urbanisation it is

surprising that the economic fulcrum of the capitalist remaking of geography has fallen so com-

pletely off the agenda. It is time to bring rent back into the analysis of land, cities and capitalism.

Keywords

David Harvey, ground rent, land rent, urban economics, urban political economy

Incidentally, another thing I have at last been able theory; pronouncing that he had at last been

to sort out is the shitty rent business . I had long able to sort out . the shitty rent business.

harboured misgivings as to the absolute correct- One would not begrudge a desperate man

ness of Ricardos theory, and have at length got even the most unlikely source of succour, yet

to the bottom of the swindle. (Marx, in correspon-

the subsequent century of economic thought

dence with Engels, [18601864] 1985: 380)

has shown land rent to be anything but

Introduction

Corresponding author:

In a letter to Engels recounting the misery of Callum Ward, Department of Geography and Tourism,

his familys impoverishment, Marx found an Celestijnenlaan 200e - box 2409, 3001 Heverlee, Belgium.

unlikely reason for optimism in land rent Email: callum.ward@kuleuven.be

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

2 Urban Studies

sorted out. Confusion and conflict has Much of the focus of neoclassical theories

reigned throughout and today the topic is of rent, and to some extent approaches in

largely neglected in the social sciences except geography since the spatial turn, has been

as a set of inherited assumptions in the mod- on spatial differences in land price.

els of urban economists or a heuristic for the However, the overarching problem requiring

idiosyncratic analyses of some Marxists. a theory of rent is not this, but that of

That is not to say that the issues sur- explaining the existence of ground rent at

rounding land rent have disappeared. They all: why does land command large values,

are central to many key contemporary topics the largest portion of which cannot be attrib-

in urban studies such as the financialisation uted to labour or interest on capital invest-

of land, the dynamics of house prices, the ment but seemingly appears for nothing?

governance of urban infrastructure, land The attempt to account for this payment

grabs, expulsions, gentrification and redlin- generates a corresponding problematic, of

ing; to name but a few. Yet even as interest which spatial differentiation is a part. In her

in these issues has intensified, their political insuperable review of the topic, Haila asserts

economic kernel land rent has been that a theory of rent broaches one or more

black-boxed as many researchers have either of three questions:

turned away from political economy

approaches in general or simply found little (1) How does (the substance of) rent emerge?

applicability from the imposing, esoteric (2) Who or what are its agents, what are

debates in the rent theory literature. The aim their behavioural patterns and mutual

of this virtual special issue is to clarify the social relations, for example, who

raison detre of a theory of rent and encour- receives rent?

age debate around its uses. (3) What is the economic role of rent, for

First, a definition of terms. Land rent is a example, what is its role in accumulation

payment made to landlords for the right to and coordination (Haila, 1990: 276)?

use land and its appurtenances (Harvey,

[1982] 2006: 331). It is the total rent paid. In our view these questions are, of them-

Ground rent is the rent paid for the use of selves, important enough to justify a pursuit

the land, minus that paid for the fixed capital of rent theory. Yet in the quarter-century

on the land (buildings and other appurte- since Haila offered this outline and called

nances). The distinction itself is not crucial for a modern theory of rent, the trend has

to our discussion and we use the terms inter- been one of neglect punctuated by isolated

changeably but, properly speaking, the dis- calls for a revival amongst critical scholars

cussions on rent theory pertain to ground (Anderson, 2014; Haila, 2015; Harvey, 2010:

rent because the part afforded to buildings 140183; Jager, 2003; Park, 2014). What

and their appurtenances is usually considered remains to be demonstrated, perhaps, is not

a straightforward return on capital invested. only that the questions themselves are signif-

Similarly, land values and the land market icant but also the efficacy of extant rent the-

fall under the purview of rent theory because ory in answering them and the explanatory

the value of land is held to be the result of its power of these answers in understanding the

estimated rental value over the future (typi- geographies of capitalism.

cally a period of two or three decades). In this introduction to a virtual special

Ground rent, then, is seen as the major deter- issue on land rent, we sketch out the history

minant of both the contracted rent paid by of rent theory, encompassing: classical polit-

tenants and the lands purchase price. ical economy; Marxs political economy; the

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 3

marginalist turn and foundations of urban The roots of a problem: Classical

economics; and the Marxist revival of rent rent theory

theory during geographys spatial turn. We

then overview some of the strands of litera- For the French physiocrats and Adam Smith

ture that have been prominent since the ([1776] 1982), land rent is the price paid for

breakdown of this consensus in political the value contributed by nature itself.

economy approaches centred on capital However, to maintain that land is a source

switching, institutionalism of various stripes of value is incompatible with the labour the-

and the rent gap theory. ories of value which prevailed in classical

We offer a critical urban political econ- political economy. A labour theory of value

omy perspective on the topic, highlighting holds that the economic value of a commod-

three problems hampering a full political ity depends on how much labour must be

economic theorisation of rent. First is a ten- spent in order to produce it. It follows from

this theory that land cannot command a

dency in recent critical literature to ignore

value in itself as it is permanent and does not

Hailas first question, of the emergence of

require labour to produce. Ricardos ([1817]

rent, and focus only on Hailas second

2004) solution was to bring rent theory into

question, the nature and operation of the

accordance with the labour theory of value

actors of rent. By thus taking the question

using the notion of differential rent.

of why we pay rent at all as unproblematic

Differential rent was first formulated by

and ignoring the particular dynamics of

James Anderson ([1777] 1984; see Clark,

rent that the idiosyncrasies of land imbue it

1988: 21) in his assertion that rent derives

with, the contemporary critical literature

from differences in fertility of the soil which,

risks reproducing the conflation of land

therefore, determine the profitability of a

and capital that underpins many of the con-

farmer using a particular plot. The land-

tradictions of capitalist urbanism (Harvey,

lords rent is her claim on the increased prof-

[1982] 2006). This needs to be addressed

itability that results from using her plot of

with a robust theorisation of the categories

land over others. Thus differential rent

of rent and of the features of land as a pri- entails only a redistribution of the profits

mary factor of production. Second, the crit- (rent is in an ingenious contrivance for

ical literature on rent has eschewed a equalising the profits to be drawn from

theorisation of the bid-rent function but in fields of different degrees of fertility, and of

doing so loses the conceptual grounding local circumstances (Anderson, quoted in

with which to build a non-functionalist the- Clark, 1988: 22). As such, if no rent were

ory of land markets and their role in the charged the price of the commodity would

capitalist coordination of space. Third, be unaffected, the tenant farmer would sim-

absolute rent has been rejected in the liter- ply not have to share her profits.

ature but should be the basis of a critical For Ricardo, labour is the only source of

theory of monopolies. Indeed, as the form value so all rent must be differential rent.

of rent that arises only through the violence Fertility is a feature of nature but is econom-

of asserting property rights or class posi- ically valuable only as a factor affecting how

tion, this category should not only be reha- much labour must be applied in order to

bilitated but requires extension beyond produce the commodity. With differential

land to an increasingly extractive financia- rents being derived from the advantage a

lised capitalism rife with distributional particular plot of land holds over inferior

conflicts. plots, Ricardo held rents to be determined

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

4 Urban Studies

by the fertility of marginal land in cultivation of profit. Marx, however, reincorporated a

that is, the least profitable land that is in theory of monopoly pricing into his rent the-

use (the amount of land in use being deter- ory in (a) allowing for the existence of natu-

mined by demand). Such marginal land com- ral monopolies (Ramirez, 2009) where the

mands no rent itself but forms a sort of unavoidable scarcity of something means

baseline: any fertility above this level is a that its price is limited only by effective

productivity gain due to the land and the demand; and (b) arguing for the existence of

resulting extra yield is taken by the landlord absolute rent, where the barriers imposed

as a condition of the farmers access to it. by the existence of a rentier class in itself is

Ricardos theory can be regarded the defini- the source of rent.

tive classical political economy statement on The general logic of the argument is to

rent and is the departure point for neoclassi- explain how the existence of rent is consis-

cal economics and Marxist theory, the two tent with a labour theory of value and to

dominant approaches to the subject. deduce the economic conditions and social

relations that must be in place for this to be

so. On this basis the two categories of rent

Marxs theory of rent are identified: differential rent, in which the

Marx reformulated the labour theory of value landlord claims the excess profit from the

and introduced two important innovations to competitive advantages of using their land

Ricardos theory of rent. In the theory of value, and so is a rent based on the distribution of

he argued that it is not the labour put into cre- profits that would exist anyway and does

ating a specific commodity that determines its not affect the price of the final commodity

value, but the socially necessary labour time produced; and monopoly rents, based on the

required to produce that or similar commodities impairment of competition which, as such,

across society as whole, that is, the average does enter into the costs of production and

labour time required to produce something affects the price of the commodity produced.

under current technological and social condi- These rents are further subdivided into

tions determines its value. two categories of differential rent (DR):

This reconstituted labour theory of value DR1, also known as extensive rent, being

led to the first of Marxs innovations to due to increased productivity attributable to

Ricardos rent theory: it is no longer neces- an existing feature of the land; and DR2,

sary to posit marginal land commanding no also known as intensive rent, being due to

rent as a baseline for differential rent. increased productivity attributable to invest-

Instead, differential rent is understood as ment upon that land. And two categories of

charged on the basis of enhancements over a monopoly rents, distinguished based on

socially determined acceptable level of prof- whether the rent flows from a monopoly

itability of land in use (see Ball, 1977; Fine, price, because a monopoly price of the prod-

1979). Differential rent in Marxs theory, uct or of the soil exists independently of it,

then, is not purely technical or ahistorical or whether the products are sold at a mono-

but depends on the specificities of prevailing poly price, because a rent exists (Marx,

socio-economic relations (Haila, 1990: 283). [1894] 1981: 910). This first is monopoly rent

The second innovation was to incorpo- in which the impairment of competition is

rate theories of monopoly rent. Ricardo had due to some natural feature of the land of

rejected Smiths proposition that rent is a which there is a limited supply; and the sec-

determinant of price, arguing instead that all ond absolute monopoly rent, in which the

rent is differential and so only a transferral impairment is attributable to the existence of

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 5

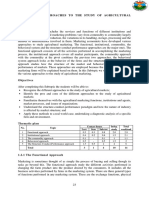

Table 1. Differential, monopoly and absolute rent.

Differential forms Description Examples

Differential rent 1 Rent arising from increases in Classic example: Fertility of the soil

productivity due to some feature of Modern example: Distance from workplace/

the land market, as per Alonso-Muth model

Differential rent 2 Rent arising from increases in Classic example: Investment in improving the

productivity as a result of fertility of the soil

investment on the land Modern example: A shopping mall which

invests in facilities and services to ensure that

its tenants receive greater custom (see

Lamarche, 1976)

Monopoly forms

Monopoly rent A rent arising from some unique, Classic example: Fine wine from a particular

non-substitutable feature of the vineyard

commodity which is, as such, Modern example: A toll road that is the only

limited only by effective demand viable route, or the sale of a Picasso painting

(see Harvey, 2012)

Absolute rent A rent arising because of the Classic example: Class of landlords preventing

existence of a class of landlords the entry of capital into the agricultural

acting as a barrier to entry for industry and so preventing the equalisation of

capital or consumers. the profit rate, maintaining higher rents as a

Can take the form of: result

1) a reservation price which Modern example: 1) housing which the

keeps land out of supply; landlord keeps vacant rather than rent out at

2) concerted, cartel-like action a loss (see Walker, 1974)

amongst landowners in order to 2) protection/creation of a monopoly

circumscribe competition and/or through litigation despite substitutability

exploit consumers otherwise, i.e. brand protection of wine from

the Champagne region of France (see

discussion in Harvey, 2012: 89112)

the class of rentiers themselves (see Table 1). first place an aspect Evans (1999, this spe-

The different forms of rent, it must be made cial issue) explores in his attempt to translate

clear, may be at work simultaneously and are it into mainstream economic theory through

empirically indistinguishable as the actual rent the concept of minimum rent. This is the

is only paid in lump sum at a price determined notion of absolute rent as a reservation

by the tenancy contract negotiations (in the price. However, while this class-monopoly

case of annual rents) and the bid-rent process is the necessary precondition for rent, it is

(in the case of land purchases). not sufficient to explain as to how the mini-

Further, the basis of rent is the monopoli- mum rent is met or exceeded monopoly

sation of particular portions of the globe by does not, in itself, create value. This is what

a certain class demanding a payment for its the categories of rent describe: a set of con-

use, so in this sense every rent is an absolute ditions (and implicit corresponding social

rent: it is only the application of private relations) in which rent above a minimum

property to land and the existence of a class tribute is possible in a capitalist economy.

of landlords demanding a certain rate of Much of Marxs work on this topic

profit that allows the existence of rent in the centred on building a theory of rent

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

6 Urban Studies

commensurate with his value theory. It is sense of creating maximal satisfaction (util-

not surprising, then, that the transformation ity), and value was held to be determined not

of classical political economy into economics by the intensity or absolute utility provided

centring around the shift from labour to (whereby bread would be more valuable

marginalist theories of value corresponded than diamonds) but that provided by the last

with a long period of quietude on rent the- unit needed to be completely satisfied; hence

ory. In addition, the agricultural question the term marginal utility (Mandel, 1962).

was no longer as salient in a century charac- On the basis of this principle, utility curves

terised by rapid and mass (sub-)urbanisa- can be constructed demonstrating the point

tion, and it was not until the 1950s that any of equilibrium, being that at which supply

serious effort was made to adapt agricultural and demand is balanced and utility is maxi-

theories of rent to the urban context. It is to mised in terms of resource allocation.

the marginalist revolution in value theory With the emergence of macroeconomic

and subsequent attempts to apply the tools and institutional approaches in the 20th cen-

of economics to understand urban land use tury, the neoclassical paradigm of pure

which we now turn. microeconomics would not maintain a com-

plete hegemony over economics but its mar-

ginalist reconception of value shifted the

The marginalist turn perspective of value theory from objective

For the classical theorists, the labour theory (in the sense of being determined by costs of

of value was held to be central because com- production) to subjective, and from the

petition pushed the value of commodities long-term perspective of the wealth of

down towards the costs of production, so nations to the abstract a-temporality of

over the long run and across the economy as mathematical modelling. As such, [f]or the

a whole (except, importantly, those situa- first time, economics truly became the sci-

tions where competition is hampered and so ence that studies the relationship between

monopoly rents arise) the determining factor given ends and given scarce means that have

of commodity prices is the value of the alternative uses (Blaug, 1985: 295).

labour imbued in them (the price here is not Insofar as the marginalist theory of value

understood as 1:1 with value but varies became dominant, the problem animating

around it, averaging roughly the same over much of classical rent theory to explain the

the long-term). This suited the agenda of apparent existence of values paid to land-

classical political economy which took pro- owners that do not correspond with any

duction and the process of capital accumula- labour imbued in a product disappeared.

tion as the starting point of analysis, with a Yet this does not eliminate the need for a

focus on the social character of economic theory of ground rent. Despite all appear-

activity (Mandel, 1962). ances to the contrary, the basic principles

Economists of the marginal revolution, determining ground rent are relatively sim-

by contrast, posited some exogenously deter- ple, as Foldvary summarises: the supply of

mined given supply of productive factors land of a particular quality, relative to mar-

and demand as an independent factor, so ginal land, sets the rent, utility being equiva-

that the economic problem was to search lent to the productivity (2008: 11). We can

for the conditions under which given produc- take issue with the Ricardian assumption of

tive services were allocated with optimal marginal land as the yardstick in Foldvarys

results among competing uses (Blaug, 1985: summary, as well as whether one wants to

295). These results were to be optimal in the use the concept of utility and productivity as

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 7

equivalents, but the basic principle applies (Clark, 1988: 3252; Marshall, 1893, 1961:

for any treatment of land rent: it is deter- 430432). In this virtual special issue,

mined by the supply of land of a particular Neutze (1987) outlines some of the estab-

sort on the one hand, with shortages in sup- lished problems in changing the supply of

ply of that sort creating monopoly rents; land but also raises the problem of uncer-

and the productivity and/or utility increase tainty over future land use (and hence value),

that that particular plot of land provides on something the prevailing static models in

the other, so creating differential rents. Of urban economics struggle to account for.

course, in that the market value is deter- If these latter arguments are accepted

mined by the supply of the product in rela- then land cannot be said to be a normal

tion to the utility its purchase provides, land form of capital responsive to supply/

is no different than any other commodity. demand, is not subject to many of the

The crucial question is whether land is like assumptions of the marginalists models,

other commodities within this valuation pro- and so requires a distinct understanding of

cess or if it has some unique feature as a fac- the emergence and dynamics of its market.

tor of production that sets it apart and Within mainstream economics the treatment

requires a distinct theorisation. of land as a form of capital is almost ubiqui-

Within classical political economy, land tous, but this appears to have been mostly

was considered a free gift of nature and, as due to mathematical convenience in being

such, was seen as a primary factor of pro- able to take only two factors of production

duction requiring a separate theory. (labour and capital) into account as opposed

Marginalists began to question this and the to being due to any persuasive argumenta-

issue of how far to erase the classical econo- tion. It seems clear to us that land is distinct

mists distinction between capital and land from capital and that this underpins many

was a major debate which never saw a satis- of the contradictions of the capitalist pro-

factory conclusion (see Blaug, 1985: 7983; duction of space. Conveniently, however,

Clark, 1988: 3252; and Foldvary, 2008, for making the assumption that land is perfectly

extensive reviews). Ultimately, at least responsive to pressures of supply and

within the economists paradigm, the prob- demand also allowed economists to con-

lem is reducible to one of the elasticity of struct models of perfect competition and

supply: the assumption made in mainstream subsequent equilibrium in land markets, as

economics is that the supply of land will be in the Alonso-Muth model outlined in the

responsive to market demand through the next section.

augmentation of available land via infra-

structure extensions, the depth of land (dig-

Von Thunen and the Alonso-Muth

ging down or building up) or simply changes

in use (Blaug, 1985). On the other hand,

model

those, such as Marshall, who felt land Ricardos differential rent theory only con-

should be separated as a factor of produc- sidered agricultural land and so did not take

tion, argued that land is unique (so it is diffi- into account competing uses of the land,

cult to find an adequate supply of a given while rent differentials were based on non-

quality), difficult to adapt to other uses marginal benefits to productivity two fun-

because of the irreversibility of changes and damental incompatibilities with marginal

other path-dependencies, and impossible to theory. Yet the core logic of the theory is

augment the supply of in some contexts formally identical with the marginal

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

8 Urban Studies

productivity theory (Blaug, 1985: 79). As emerged in the 1960s with the work of

such, the development of location theory in Alonso. Alonsos (1964) innovation was to

mainstream economics proceeded as an translate Von Thunens agrarian land use

adaptation of Ricardian differential rent but model to one of urban land uses and within

with its basic assumptions replaced by mar- a neoclassical framework based on utility

ginalist ones (of competing uses determined and spatial equilibrium. Like Von Thunen,

by marginal utility curves translated into the Alonso assumed a central node and rising

price mechanism and resulting in equili- transportation costs as one moves away

brium). In fact, location theory in economics from the centre. However, Alonso also

took its departure point not directly from introduced the possibility of substitution

Ricardo but from a 19th-century German and variations in taste. So some users are

landowner, Von Thunen, who modified fun- willing and able to pay more for central

damental Ricardian assumptions by making land than others, which explains the loca-

rent differentials not dependent on increased tion of the typical North-American Central

productivity over the worst land, but a func- Business District (CBD), but the poor may

tion of distance and transportation costs to live more centrally in more intensively used

market. land, or the rich may choose to live further

Von Thunen (1926) developed an agrar- out and pay more towards transport costs

ian land use model in order to price his own so as to own a larger plot of land. This

land by assuming that there is a single price became enshrined as the Alonso-Muth

at the market for each agrarian product. model, after Muth (1969) complemented

Further, production costs and the required Alonsos focus on urban land with one on

income for the farmer are assumed to be the urban housing and a simplified conception

same for each land unit. The market price of utility assuming equilibrium of loca-

per hectare minus the farmers required tional costs/benefits.

income and the production costs then equal In this virtual special issue, Spivey (2008)

the bid-rent plus the transportation costs. is representative of a number of recent urban

Therefore, land that is closer to the market economics articles (see also Lauridsen et al.,

has lower transportation costs and com- 2013; Sexton et al., 2012; Verhetsel et al.,

mands higher bid-rent. There are competing 2010) empirically applying the Alonso-Muth

uses of the land in terms of what agricultural model and finding that, despite its simplify-

commodity the farmer produces and some ing stylistic assumptions, it captures an

products need shorter transportation times approximate mechanism shaping the mor-

to the market (e.g. dairy products) than oth- phology of cities. This approach is essen-

ers (e.g. grain). It follows that there are con- tially static the models capture a point in

centric rings of land use, commonly termed time and do not account for change so

Von Thunen rings, as formalised by Abelsons (1997) article is remarkable in

Launhardt (1885; Blaug, 1985: 618; Shieh, incorporating an historical account of the

2003), who produced Figure 1 demonstrat- development of an urban area. Finally, Phe

ing the rent gradient in such a model. and Wakely (2000) offer an interesting

Although the earliest examples of a mar- attempt to improve the realism of the

ginal mode of analysis were thus developed Alonso-Muth model by adapting its assump-

in relation to agricultural land, land and tions to include the meaning and perception

space are neglected topics in mainstream of place, thus attempting to incorporate cul-

economics largely left to the specialist sub- turally determined relational factors affect-

discipline of urban economics which ing the value of location.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 9

Figure 1. Von Thunen rings.

Source: Blaug (1985: 619).

In summary, for Von Thunen, Alonso rent. For Alonso, not only transportation

and neoclassical economists in their wake, costs (DR1), but also the intensity of land

differential rent/marginal utility is key while use and differences in the costs of preparing

monopolies, if recognised at all, are seen as land for urban land use (DR2) are sources of

aberrations and are not incorporated in their rent. Differential rent/the marginal utility of

models. For Von Thunen, rent is paid for different land, therefore, is an expression of

the relative advantage of a place compared the relative advantage of a place and helps to

with the most marginal, e.g. as a result of explain a crucial geographical aspect of land

lower transportation costs, higher fertility rent theory: why are there spatial differences

(DR1, in Ricardian/Marxist terms), or in land price? As an approximate mechan-

because of differences in the costs of prepar- ism, this is useful beyond the assumptions of

ing the land for agrarian use such as irriga- urban economics. If we reject the assumption

tion (DR2). The productivity of the land, of spatial equilibrium, for instance, one can

and therefore the land price, can be increased see this as an important driver of uneven

if the costs of creating higher productivity development (see Smith, 1984: 175205). The

are lower than the potential increase in the subsequent critical consensus on rent theory,

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

10 Urban Studies

however, was predicated on the rejection of consensus of the bulk of contributors to

this mechanism. Urban Studies will be shaken (Pahl, 1974:

93).

A significant portion of Harveys attack

The Marxist revival on such approaches centred upon the failure

of the Alonso-Muth model to take into

The short-lived revival and subsequent

account the path-dependent and power-

decline of heterodox rent theory has received

laden nature of actually existing urban geo-

extensive review, definitively so by Haila

graphies (1973: 153194). By introducing

(1990), but see also, among others, Ball et al.

class and power to the rent debate, Marxists

(1985), Clark (1988), Park (2014). Given

such as Harvey were able to move beyond

this, we restrict ourselves to a summary

simplistic centreperiphery models of land

overview here, seeking to offer an interpreta-

rent and come to a fuller understanding of

tion of the direction in which this literature

the central role of land in urban politics and

has moved in the 25 years since Hailas

vice versa. This also allowed explanations of

review. Following her periodisation, hetero-

changes in land use aiming to understand

dox rent theory is understood as enjoying a

rather than describe or predict land use var-

consensus during the 1970s under the influ-

iation a` la the Alonso-Muth model. In

ence of Harveys (1973) critique of urban

accordance with this, there was a focus on

economics, then a period of transition as this

monopoly and absolute rents as power rela-

consensus broke down (notably marked by

tions, framed explicitly in opposition to neo-

Harveys reformulation of rent theory in The

classical assumptions of optimal outcomes

Limits to Capital, [1982] 2006), and a mid- to

and spatial equilibrium achieved through a

late-1980s rupture as any common frame-

competitive market. The emphasis placed on

work for a theory of rent fractured and

the existence of absolute rents appears to

researchers began to question its founda-

have been informed by this opposition: if it

tions and function.

is allowed that there exist rents which enter

the cost of production, then this undermines

the supposition that the price mechanism

Consensus

can deliver such an equilibrium.

David Harveys Social Justice and the City Given the focus on power, there was also

(1973) was a seminal text in geographys an emphasis on landlords role as a social

general turn away from purely quantitative class and a tendency to view them as a para-

methods and towards what is now known as sitical obstacle to accumulation (Massey and

critical geography. Given the seismic Catalano, 1978). Hence Harveys (1974)

importance of its break with urban econom- urban application of absolute rent as class-

ics for both rent theory and human geogra- monopoly rent in which the class of land-

phy as a discipline, we have included this owners, together with state institutions,

journals review of the book (Pahl, 1974). In create artificial scarcity by keeping land off

this book review one can see the central role the market on the one hand, and creating

that Harveys critique of the Alonso-Muth exclusivity in land use on the other.

model played in the germinal stage of the Similarly, building on Emmanuels (1972)

spatial turn and its profound implications monopoly-based theory of rents (see also

for the discipline expressed in the authors Emmanuel, 1985), Walker (1974) attempted

hope that this critique of urban economics to extend rent in the urban context as a the-

means that the somewhat antiseptic ory of monopolies within the sphere of

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 11

exchange and consumption, positing govern- This inaugurated the period of rupture

ment transfers as a form of distributional (Haila, 1990), in which debates raged and

rent and offering an early formulation of confusion grew over the coherence, applic-

absolute rent as a reservation price in order ability and definition of the rent categories.

to explain the existence of vacant housing Certainly a recognition of differential rents

alongside shortages in supply. Thus, driving importance was necessary and insightful, as

the Marxist revolution of human geography was a recognition of the limits of absolute

in the 1970s was a project of urban political and monopoly rent. However, the way in

economy with rent at the centre, but in the which these concepts were recalibrated was

1980s this common grounding in rent theory incomplete and confused.

became less sure. First, even as differential rent was

placed at the centre of Marxist rent theory

there was still a suspicion of marginalist

Rupture approaches and, correspondingly, the bid-

Conceptualising the role of land rent within rent function was eschewed. In The Limits

capitalism is complex. The consensus in 1970s to Capital Harvey allowed that differential

geography had been to follow what was per- rent played a positive coordinative role

ceived to be Marxs view that landlords were that was central to capitalisms viability

a feudalistic hangover acting as a drain on and spatial form yet ignored the central

capitalist productivity. In the late 1970s and mechanism in this (that of competing users

early 1980s, however, there was a reappraisal bidding for the use of the land) and the

in which landowners were increasingly seen major body of theory attempting to explain

as a fraction of the capitalist class critical to that mechanism (that based on the Alonso-

capital accumulation (Braudel, [1979] 1992; Muth model). Ultimately, this rendered his

Harvey, [1982] 2006; Scott, 1980; see Haila, account of the actions of landowners as a

1990). Further, the category of absolute rent, class reliant on functionalism (Kerr, 1996),

which entails the power of the rentier class to and the failure to analyse the bid-rent pro-

create otherwise non-existent costs, was jetti- cess made a wider Marxist theory of land

soned as scholars such as Fine (1979) ques- markets impossible by black-boxing a cru-

tioned its applicability outside of the context cial mechanism which should be the basis

of 19th century agriculture. This followed of theoretical generalisation.

Balls (1977) recognition that differential rent Second, the move away from monopoly

the rent based on productivity gains rents on the basis of a rejection of absolute

afforded by the land was more important rent as a category was confused. Here (i.e.

than previously allowed. Bringing these Fine, 1979; Harvey, [1982] 2006), the defini-

strands together, Harvey ([1982] 2006) offered tion of absolute rent was understood as the

a new conceptualisation of the role of rent dynamics of value creation that Marx

and landowners, in which rent was argued to described to explain its existence in 19th cen-

be crucial to accumulation in (a) ensuring tury agriculture: that of barriers to capitals

competition amongst capitalists by draining entry into the industry created by the land-

excess profits attributable to location and (b) owners class-monopoly, so circumscribing

insofar as landlords increasingly treat their competition and allowing a higher organic

land as financial assets they will seek to composition of capital and therefore more

enhance the productivity of land in order to surplus value produced. On the basis of this

capture more differential rents, thus coming definition, many began to reject the possibil-

to play a crucial spatially coordinative role. ity of absolute rent in the urban context.

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

12 Urban Studies

However, to define absolute rent as a rent shades of institutionalism gutted of substan-

arising because the landowners are able to tive political economic analysis.

create a higher organic composition of capital We would speculate that the decline of

is unnecessarily narrow. Marx defined abso- rent theory was also partially (perhaps pri-

lute rent as a situation where a monopoly marily) metatheoretical. The 1980s saw a

price is commanded because the rent exists general rejection of structuralism, an atten-

and creates some sort of impairment to com- dant cultural turn and fractured methodo-

petition (Marx, [1894] 1981: 910). Harveys logical reconstruction. Rent theory had been

work on the notion of class-monopoly in the closely associated with structuralism and

1970s showed this to be possible in a modern was an early casualty of geographys philo-

urban context, and it is bemusing that the def- sophical regrounding. Yet while the Marxist

inition of absolute rent was obfuscated to the urban political economy singled out for criti-

point where such analyses were for a long cism was often structuralist in nature, they

time ignored before being rediscovered as are theories open to differences and change.

class-monopoly rent but not integrated to The purpose of the work of scholars such as

wider rent theories nor acknowledged to be a Topalov (1984) who analysed how areas that

form of absolute rent (e.g. Aalbers, 2011; should bear a high rent develop into segre-

Anderson, 2014; Baxter, 2014; Wyly et al., gated, rundown areas in which rents are very

2009). This, further, has meant that the basis low or even negative; and Smith (1979), who

of a Marxist theory of monopolies has been analysed how this process may prepare

absent where it should have been highly appli- some areas for social and physical change,

cable to a contemporary economy rife with signifying a steep increase in rent; is to create

rentiers of immaterial goods in a financialised theories of iterative relations able to explain

knowledge economy (Hardt, 2010; Ramirez, difference and change rather than to argue

2009; Zeller, 2008). that the underlying structures create the

Regardless of the precise definition of the same outcomes always and everywhere.

categories of rent, if one accepts that there However, the strawman fallacy that rent the-

exist rents which enter into the price of pro- ory attempts to provide one explanatory

duction, then the neoclassical models of spa- structure for every process involving land

tial equilibrium are incoherent. At the same across every context would become a basis

time, it is clear that the Alonso-Muth model for its rejection by many. In the rest of this

captures a key mechanism in the dynamics article, we turn to the contemporary strands

of differential rent shaping space. What is of literature that emerged following this

missing is a heterodox rent theory which can rejection.

use these insights but be sensitive to their

limitations and place them within the con-

text of historically geographically bound

The magic roundabout

social contestation and uneven development; As Haila (1990) styles it, two main camps

as socially, legally and politically produced developed in this period of dissensus: a

and compromised by the existence of path- nomothetic one led by Harvey, which seeks

dependencies and monopolies. While a few to derive generalisable laws; and an idio-

have attempted such a synthetic approach graphic one led by Ball, which advocated

(Park, 2011; Van Nuffel, 2005), theories in describing specific social relations of prop-

this tradition, on the whole, have failed to erty development as opposed to relying on a

account for the dynamics of the land market general theory of rent. Following his exhor-

and have instead come to rely on varying tation to look at detailed historical

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 13

situations rather than to make gestures critique of rent theory as a universal theory,

towards some grand general theory (Ball, not a general one in the sense of seeking gen-

1985a: 86), Ball advocated a structures of eralisable laws applicable to many instances.

provision approach which would focus on For Haila, meanwhile, the problem with rent

describing the established sets of agents theory was that it appeared to take its gener-

within a given context and the patterns of ality as a given whereas, she asserted, any

their interactions (see Ball, 1998, this virtual such generalities must be substantiated

special issue). However, as he continues through empirically observed mechanisms.

immediately after rejecting gestures towards She identified the tendency for landowners

a grand general theory: to increasingly treat their land as a financial

asset as just such a mechanism, for insofar as

Even though the effects of rent depend on his- land is mobilised as a commodity then land-

torical circumstances the conditions that struc- lords become subject to the general laws of

ture the operations of landed property at those accumulation and rent comes to have a coor-

points in time still need to be theorised; analys-

dinative function over space. Harvey ([1982]

ing rent mechanisms and evaluating their con-

sequences are part of that theorisation. (Ball, 2006) initially posited this tendency but

1985a: 86) Haila departs from him in arguing that it

cannot be theoretically deduced from posited

Effectively, Ball is emphasising that rent is tendencies internal to the logic of capital,

only one aspect of understanding land mar- but instead must be empirically investigated

kets and property development. Such an with an account of landlords behaviour. So,

emphasis on variegation in property markets in contrast with the old theory of rent

and the importance of institutions was which explains rent within the system of

undoubtedly necessary, yet it is not clear production, a new theory of rent hinges on

how Ball jumps from this to pronouncing empirical exploration of the existence,

the death of urban rent theory (Ball, 1985b: scope, and meaning of the tendency of land

504). As Haila (1990: 285) points out, it is to become a pure financial asset (Haila,

self-evident that relations in reality involve 1990: 270, 292).

much more than an abstract rent relation. For Kerr (1996), however, both Ball and

Further, we would add, while the dynamics Haila offer circular theories because they

of rent is only one aspect deciding a given focus on the contingencies of real estate

socio-spatial outcome, it is the only one that market dynamics and the actors therein to

we know we can find across any capitalist explain rent but, at the same time, allow that

context (capitalism being itself a historically rent and rent-seeking are important aspects

specific set of relations) and the only one of that dynamic. Rejecting the crossroads

that amounts to a set of necessities condi- Haila posits between old ossified theory

tioning the nature and existence of land mar- and the new theory of rent she outlines

kets. This does not mean that they are (1996: 294), Kerr mischievously1 offered a

mechanistic or deterministic (indeed, they counter-characterisation of rent as a magic

offer little predictive power as to specific roundabout because both Ball and Hailas

outcomes) but it certainly means they are a theories of rent start and end with the activi-

crucial component of any analysis. ties of landowners, rather than with capital

Balls critique of rent theory depended on accumulation and the capitalist users of

refuting it as a theory that aspired to be able landed property (Kerr, 1996: 80). The sole

to explain everything in every context. This, concern with the nature of the agents of rent

Haila (1990: 287) points out, amounts to a led to a focus on the influence that

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

14 Urban Studies

landowners/property developers have on focusing on the entry of capital into the built

land prices without connecting that analysis environment institutional approaches devel-

either to the dynamics of capital production oped from a wide range of theoretical per-

and circulation, nor land use. In contrast: spectives but which all in some way explicitly

focus on a theorisation of organisations and

this tautology can only be transcended . if actors of rent as their guiding frame, and the

the theory of rent recognises the real estate literature on the rent gap which remains the

sectors dynamics does not explain rent but most consistent contemporary application of

rather presupposes its existence and the chang- rent theory.

ing ability of users to pay such rent. (Kerr,

1996: 82)

Capital-switching approaches

This accords with our reading of rent litera-

ture over the last 25 years in which there has Scotts article in this virtual special issue is

been a convergence upon institutional to be located within the transitional stage of

approaches describing a diversity of actors the development of the rent literature, expli-

of rent, their immediate motivations and citly placing itself within the urban political

social relations without any connecting anal- economy problematic which seeks at the

ysis of rent as a political economic category outset to conceptualise the urban process in

itself. The effect has been to implicitly repro- relation to the structure and dynamics of

duce the economists denial of any funda- commodity production (1982: 112). While

mental difference between land and capital. Scotts piece is somewhat atypical of this lit-

Rent revenues from the land do, in practice, erature in drawing upon a Sraffian rather

become treated as pure financial assets indis- than Marxist approach, it is characteristic of

tinguishable from capital; but it takes a what Haila deemed old rent theory in that

complex set of institutional, regulatory, it embeds a theory of rent and location

socio-cultural, calculative and political prac- within the system of production. It was a

tices to make it so. We have become very growing rejection of this productionist focus

good at documenting these in the literature that underpinned the move towards what

on calculative practices but in doing so have she christened a new theory of rent (Haila,

tended to forget the caveat that rent is funda- 1990: 290) focusing on investment flows into

mentally different to capital proper; arising, the built environment.

as it does, in a very different way and with a This rejection was intertwined with

peculiar set of characteristics. The conflation metatheoretical changes in geography, with

of rent and capital in actual practice is a fun- the focus on production perceived as a fea-

damental contradiction of capitalism exactly ture of structuralism: Gottdeiners (1985)

for this reason and ends in disastrous rounds application of structuration theory to the

of market rationalisation being applied to development of the built environment was a

socio-spatial configurations (Harvey, [1982] frequent touchstone in the literatures grow-

2006). To reflect this conflation in analysis is ing assertion that real estate has its

to reproduce a contradiction of practice into own internal dynamics linked to those of

one of theory also. finance as opposed to being subservient to

In the rest of this review, we will look at that of manufacturing (see Aalbers, 2007;

prominent contemporary approaches which Beauregard, 1994; Feagin, 1987; Gotham,

can be said to have spun off from this magic 2002). Surprisingly, however, the insight that

roundabout: capital-switching approaches real estate has autonomous dynamics to

within the urban political economy tradition those of manufacturing did not provoke any

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 15

exploration of the economic category of the The other article from this strand of liter-

rent on the land as quite distinct from the ature selected in this issue, by Guironnet

category of profit on capital. The result has et al. (2015), encapsulates why it is proble-

been the proliferation of studies emphasising matic to replace an analysis of rent with an

contingent practices of property develop- account of the links between finance and real

ment which, nevertheless, blackbox the one estate. Rejecting the focus on rent maximisa-

thing at the heart of the whole process in the tion in the literature on the mobilisation of

appropriation of rent, so also undermining urban land as a financial asset (Charnock

the basis for generalising their insights out- et al., 2014; Harvey, [1982] 2006; Kaika and

side of the particular context under investi- Ruggiero, 2016; Moulaert et al., 2003), they

gation vis-a`-vis the motivations and logics of assert that in adopting a conception of

rent. financialisation as a general process affecting

Here we have selected two papers engaged all landowners irrespective of their charac-

with this tradition, the first from Bryson teristics this approach paradoxically fails to

(1997), bucks these trends and offers a sub- fully engage with the growing importance of

stantiation of the sort of rent theory Kerr financial markets and investors (Guironnet

(1996, see above) had called for. Bryson et al., 2015: 2). The problem, we suggest, is

points out that a series of intermediaries precisely the opposite. To assert that the lit-

determine whether and how supply reacts to erature claims financialisation is an even

demand and argues with respect to the process affecting all landowners irrespective

power of capital markets that investors cri- of their characteristics omits the body of

teria are a crucial determinant in the produc- work reviewed above emphasising exactly

tion of the built environment (Bryson, 1997: the historical contingencies of landowner

1440, 1442). Yet he does not claim they are characteristics in accounting for the ten-

independent of the dynamics of rent. Rather, dency to treat land as a financial asset and

[w]hat is built and where it is built is deter- the associated switching of financial capital

mined by current rental levels and yields as into the built environment. The problem at

well as by the actions, perceptions and moti- the core of much of this literature is, as

vations of a variety of property development Bryson (1997: 1456) put it, a confusion

and investment interests (Bryson, 1997: between the actions of landowners and the

1445), and his empirical analysis of develop- role of rent as a mechanism to control the

ment in a marginal property market depends operation of the urban land market.

on exactly this: on the combination of inves- Guironnet et al. not only reproduce this

tor requirements and the manipulation of confusion but compound it further by

rent mechanisms by property developers in obscuring the dynamics of the land market

order to ensure revenue from the specific as the subjectivities of investors. Thus, the

properties in question. In this approach com- developer makes particular demands over

bined with an analysis of the sort recently the surface area of the development for that

offered by Smet (2015), which attempted to which they have deemed profitable in

draw connections between housing prices the light of . market circumstances, it

and the geographically bound production demands particular allowances on the basis

and circulation of economic revenues, one of [c]laiming an intimate understanding of

could imagine how theories connecting the the market and certain features of the wider

dynamics of surplus production and the cir- built environment in the locality are sought

culation of rents might be constructed with- by investors because this is believed to influ-

out being deterministic or productionist. ence both resale and rental liquidity (2015:

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

16 Urban Studies

1516); and all of this is proffered as proof approaches, as Balls (1998, this virtual spe-

that investors expectations shape urban cial issue) review of institutions in British

development. Rather than entertaining the property research demonstrates.

notion that these demands might correspond Perhaps the most notable thing about

to strategies to maximise rent on that partic- institutionalist approaches is their lack of a

ular plot of land and in that particular land shared definition over what an institution is

market, the analysis is halted at the fact that and what status a theory of institutions

international investors and their local inter- should hold. Ball ascertains two main defini-

mediaries form expectations about the mar- tions: a formal one based on the framework

ket and act upon them. of property rights (distinguishing between

As a result, their analysis begins to look organisations as the players and institutions

very much like the radical idealism of which as the rules) and casual one in which agen-

Smith (1996, see below) accuses Bourassa cies involved in property development are

(1993). A more charitable interpretation may understood to be institutions (1998: 1502).

be that their approach amounts to a form of Balls adoption of the casual definition on

what Ball (1998, this issue) termed conflict the basis that it appeals to the common sense

institutionalism and the authors do gesture meaning of the term appears to sit uneasily

towards this in calling for the development with his criticism of ad hoc institutionalism

of a financialised structures of provision (and what he terms conflict institutionalism

approach. However, they neither define the as ad hoc) on the basis that [t]here is no

concept nor deploy it in analysis. This is one clear theory of institutions and how to study

demonstration of how political economy them, rather elements are drawn together in

approaches concerned with the entry of capi- ad hoc explanations (Ball, 1998: 1506).

tal into the built environment, shorn of the As, indeed, does his avocation of a struc-

substantive political economic analysis of tures of provision approach as not a com-

rent theory, have begun to converge upon a plete theory in itself . [but rather] a series

rather ad hoc institutionalism. of statements about how to examine institu-

tions and their roles (Ball, 1998: 1514).

However, this is not a contradiction for Ball

Institutional approaches as he appears to be content with a theory of

For Marx ([1894] 1981) the institution of the institutions as a bolt on for other theories

state was crucial in creating the possibility of as and when including institutions in the

rent as it is only through property rights analysis provides greater explanatory power.

(defined and maintained by and through This is what the SOP is designed as: theoreti-

states) that land is monopolisable. The cor- cal guidelines about institutions and their

rective to this provided by institutional role in mediating supply/demand which can

approaches are important in their theoretical be appended to other theories (see also Ball,

formalisation and expansion of the role of 2002). There is a lack of studies using this

institutions beyond merely enforcing prop- framework but Ball himself (2003) offers a

erty titles, as well as their insistence that study of factors affecting housing supply,

property regimes and their implementation while in this virtual special issue Wu (1998)

are variegated. However, institutionalism deploys the framework in the context of

itself is a wide tent with oft vaguely defined Chinese urbanism.

concepts and little by way of shared epis- For others, such as Needham et al.

temologies or method between different (2011), in this virtual special issue, a bolt

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 17

on approach to institutionalism runs the synthetic approach to land rent and urban

risk of institutions becoming a deus ex development.

machina, deployed to explain away empiri- Indeed, while some, such as Guy and

cal results that run counter to the core the- Henneberry (2000), are sceptical of eco-

ory. Embedded in new institutional nomic approaches to land markets in favour

economics which reduces institutions to of agent-focused institutionalism, there is no

transaction costs, they aim to complement inherent mutual exclusivity. Institutionalism

this by looking to the more casually defined can be bolted on to mainstream economics

old institutional approaches to build a the- (see Ball, 2002; Guy and Henneberry, 2002;

ory which makes institutions internal to the although this is a superficial solution in our

theory of land markets. However, they view, as per Needham et al., 2011) and from

maintain the methodological commitment to a political economy perspective the institu-

deductive, predictive model-making of main- tional approaches to land and rent surveyed

stream economics and within this paradigm could be said to be variations on the

find that they cannot construct a general Polanyian ([1944] 2002: 187) theme that

theory of markets which take into account land is an element of nature inextricably

institutions, instead arguing for partial the- woven with mans institutions. Polanyi

ories tailored to explain the context of inter- deemed the commodity of land itself ficti-

est. That their attempts at a general theory tious, meaning it is a commodity only

fail is hardly surprising, for they attempt to through social construction as opposed to

integrate an old institutionalist approach being the result of a production process.

acknowledging that man-made institutions This being so, institutional factors funda-

can affect preferences (Needham et al., 2011: mentally shape the market in general and

166) within a neoclassical methodology that give rise to a relatively unique position for

is predicated on taking preferences as given. landowners in that their engagement in rele-

Offering an institutionalism more rooted vant institutions directly shapes the form,

in political economy, Healey and Barretts content and profitability of their own com-

framework attempts to combine the insights modity. There is no fundamental logical

from the traditions of institutional analysis contradiction between land being institu-

. with the neoclassical analyses of the oper- tionally constituted as a commodity, and

ation of the urban land markets and Marxist that commodity being a concrete one from

approaches to the way capital flows through the point of view of the market and so sub-

the built environment (1990: 90, this virtual ject to general laws of accumulation.

special issue). However, their treatment of

rent is indicative of the obfuscation of rent

prominent in the political economy literature

Rent gap

and outlined in the previous section. In The rent gap literature provides a synthetic

short, they reject the applicability of theories conceptual tool which has been a consistent

of rent and argue that to understand the way application of rent theory at the urban level

capital flows through the built environment but has remained curiously isolated from

is to understand the financial agents invest- wider theorisations of rent. Neil Smith

ing into it (1990: 9294, this virtual special (1979) developed the rent gap as an explana-

issue), an assertion which leaves them subject tion of where and why gentrification takes

to the critique offered of Guironnet et al. place. Emphasising that the ground rent and

(2015), above. Nonetheless, their framework the house value are separate components

demonstrates the potential of a more making up the house price, he pointed out

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

18 Urban Studies

that as houses age and if they are under- reflect the best use of the land regardless of

maintained the house price, the house the actual use.

value and the capitalised ground rent all go This critique emanates from a neoclassi-

down but that the potential ground rent cal methodology that cannot account for

remains stable or even goes up (following change: it simply assumes that the best price

the assumption that more central places will be reached immediately and automati-

have higher ground rents and that these go cally, regardless of the actual use of the land

up if the metropolitan area extends). Smith or any informational and/or power asymme-

labelled this difference between the potential tries. This, Smith argues, amounts to a radi-

and capitalised ground rent the rent gap. cal idealism centred on the desquamation of

Over time, the rent gap widens until the taste (1996: 1201, this virtual special issue).

point at which it becomes profitable enough Clark (1995, this issue), meanwhile, points

to attract investment in redeveloping and/or out a number of technical points Bourassa

revalorising the land, with the gap then misunderstood regarding rent gap theory

closed through the actions of property-based and offers an adjusted representation of the

capital. In this supply-side explanation, gen- rent gap as compared with Smiths (1979)

trification thus represents a back to the city original, allowing that speculation drives up

movement by capital, not people (Smith, the land rents prior to a change in land use

1979). (Figure 2).

Rent gap theory offers a powerful under- Further, as both Clark and Smith argue,

standing of the way in which the dynamics rent gap theory is not intended to be predic-

of rent determine the geographies and tem- tive but an explanatory tool to understand

porality of investment into the built environ- the geography of gentrification in particular

ment. Smiths explanation of gentrification places at particular times (Smith, 1996:

came to dominate the literature on the 1202). Bourassa incorrectly separates rent

subject throughout the 1980s at the expense gap theory from the larger theoretical frame-

of demand-side explanations, although it work in which it is embedded, that of a

attracted some criticism (among others, political economic theory of uneven develop-

Hamnett and Randolph, 1984; Ley, 1987). ment on the urban scale [which] as such can-

Bourassa (1993, this virtual special issue) not be divorced from the societal relations

argued that Smiths distinction between two and power struggles involved in the creation

forms of ground rent (capitalised and poten- and capture of values in the built environ-

tial) does not contribute to the explanation ment (Clark, 1995: 1489).

of either the location or timing of changes in It is in this particularity, the adoption of

land use. For Bourassa, rent, by definition, the viewpoint of a particular neighbour-

is based only on the current use of land, hood, that we find the limits of rent gap the-

making it conceptually impossible to speak ory. Hammels (1999) article in this issue

of potential rent. In his neoclassical account points to this in arguing for greater attention

there can only be a difference between cur- to be paid to scale in rent gap theory on the

rent and potential, feasible land uses basis that potential land rent is determined

[b]ecause land rent and value change as soon at the metropolitan scale and capitalised

as perceptions about the future change and land rent at the neighbourhood scale (1289).

do not wait for land use to change (1993: Indeed, within the reduction of potential

1741, emphasis in original). That is to say, rent is a whole world of demand-side factors

any future potential rent is the current rent and the wider dynamics of rent. Regarding

because the capitalised rent is adjusted to this latter, Smiths supervisor David Harvey

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 19

Figure 2. The rent gap.

Source: Clark (1995).2

himself mired in the categories of rent the- rent. In this, rent is determined by the sup-

ory in writing The Limits to Capital at the ply of land of a particular sort on the one

time was famously dismissive of his gradu- hand, with shortages in supply of that sort

ate students efforts (Slater, 2015), and this creating monopoly rents; and the productiv-

can be said to have rather anticipated a sym- ity and/or utility increase that that particular

pathetic but definite distance between rent plot of land provides on the other, so creat-

gap and land rent theory. Although the link ing differential rents. Aspects of these differ-

to a wider analysis of rent is explicitly made ential rents as an approximate mechanism in

in rent gap theorists emphasis on uneven the urban context are captured well by neo-

development (Clark, 1988; Smith, 1984), classical models, and aspects of the monopo-

their particular scalar focus has led to a lack listic, socially constructed nature of land

of integration between the two and Bryson ownership are captured well by institutional

(1997, this virtual special issue) is rather analyses; however, with the convergence

exceptional in deploying both rent gap the- towards institutional approaches in the criti-

ory and an analysis of the rent mechanisms cal literature, the emergence of rent has been

at work in a particular development. neglected and so an understanding of how

capital flows through land made untenable.

In doing so the critical literature reproduces

Challenges for future research

the conflation between land and capital of

To summarise, land has unique features as a both mainstream economic analysis and the

factor of production that sets it apart from extant practices of investors treating land as

capital in general and requires a theory of a financial asset, thus losing sight of a

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

20 Urban Studies

crucial contradiction which should be cen- political heuristic to expose extractive power

tral to critique. relations within an institutional analysis (e.g.

Heterodox rent theory has fallen into a Baxter, 2014; Charnock et al., 2014), or

state of dilapidation due we suggested to obfuscated the issue of rent altogether. The

three major problems that emerged follow- bid-rent mechanism is crucial to understand-

ing its rupture (Haila, 1990). Here we out- ing the land market in a way that avoids slip-

line them again alongside associated ping into functionalism and should be

suggestions for rehabilitating rent back into integrated with considerations of power,

the centre of analysis. capital accumulation and associated uneven

First, within the context of urban land development.

rent, a mixture of confusion over the appli- Third, a confusion over the status of

cations of rent theory alongside rejection of absolute rent has led to disarray. This has

structuralist explanations led to the prolif- meant that even where absolute rent has

eration of approaches emphasising contin- been unavoidable for analysis, as in those

gent mediations and agentic factors rather using the concept of class-monopoly rent to

than connecting analyses to a general theory understand urban property markets, there

of rent. This was an important corrective to has often been a lack of integration with

a literature which often paid insufficient wider understandings of the dynamics of

attention to mediating factors. However, in rent. Most frustratingly, absolute rent

the course of this redressal theorists have should be the basis of a general Marxist the-

failed to distinguish rent as an economic ory of monopoly and its neglect has fore-

category distinct from its constitutive institu- closed potentially fertile ground to extend

tions (in the case of Ball, 1985b), typology the theory beyond land to other situations

of its actors (in the case of Haila, 1990), or where the existence of a class of rentiers

fictitious capital in general (in the case of itself creates rents for instance, in the case

Guironnet et al., 2015). In attempting to of immaterial commodities where profit is

combine an emphasis on the importance of reliant on the imposition of intellectual

all of these with a consideration of the property rights, and the process of financia-

dynamics of rent mechanisms, Bryson (1997) lisation across the economy generally.

offers an example of an alternative to this Indeed, insofar as we accept that much new

magic roundabout. production is effectively enclosure of vari-

Second, reservations regarding theories ous commons (Zeller, 2008), then this form

centring on the phenomenal form of price of rent should be the central category for

(as opposed to underlying value dynamics) understanding capitalism today.

meant that when Marxists conceded differ- Amongst current talk of an

ential rent a central place in rent theory, little Anthropocene and planetary urbanisation

attention was paid to the bid-rent mechan- it is surprising, to say the least, that the eco-

ism. This rendered their account of landlords nomic fulcrum of the capitalist remaking of

as a class functionalist and disconnected it geography has fallen so completely off the

from an understanding of the wider land agenda. One would reasonably expect the

market (e.g. Harvey, [1982] 2006: 330372). interplay of capitalist and spatial dynamics

So instead of connecting their research to and their metabolism through the rent rela-

macro-level analyses and theories of the land tion to be at the very core of geography and

market, researchers in this tradition have urban studies. A theory of ground rent is

tended to adopt as Ball (1985a) suggests required not only for analyses of the politics

they should the rent categories as a of rural land (see Lefebvre, [1956] 2016)

Downloaded from usj.sagepub.com by guest on April 20, 2016

Ward and Aalbers 21

especially its contemporary issues of large- Notes

scale land grabbing but is a crucial link 1. Seemingly both a reference to the town of

between urban political economy and the Swindons infamously confusing and turgid

burgeoning field of political ecology more magic roundabout crossing; and the mid-

generally (Andreucci et al., forthcoming). 1990s British daytime TV schedule in which

Further, if the challenge of the last century Crossroads was a melodramatic soap opera,

was to apply land rent theory to the urban and the The Magic Roundabout a nonsensical

context, the challenge of this looks to be to childrens show set on an enchanted fair-

take the categories of rent beyond land in ground carousel.

2. Potential land rent (PLR); capitalised land

the analysis of a capitalism increasingly reli-

rent (CLR); building value (BV).

ant on flows of rentier income through

financial instruments (recently theorised in References

the context of real estate by Haila, 2015, as

Aalbers MB (2007) Geographies of housing

derivative rents), immaterial commodities

finance: The mortgage market in Milan, Italy.

enforced by property rights such as in the

Growth and Change 38(2): 174199.

case of carbon trading (Felli, 2014) and so- Aalbers MB (2011) Place, Exclusion and Mort-

called sharing economies on digital plat- gage Markets. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

forms; while, correspondingly, contempo- Abelson P (1997) House and land prices in Syd-

rary social struggles increasingly centre upon ney from 1931 to 1989. Urban Studies 34(9):

the existence and distribution of these new 13811400.

and old forms of rent. The challenges for Alonso W (1964) Location and Land Use: Toward

future research are manifold, but the con- a General Theory of Land Rent. Cambridge,

ceptual foundations exist. It is time to get MA: Harvard University Press.