Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review Inf Sys Wade and Hulland 2004

Review Inf Sys Wade and Hulland 2004

Uploaded by

Pedro NunesOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review Inf Sys Wade and Hulland 2004

Review Inf Sys Wade and Hulland 2004

Uploaded by

Pedro NunesCopyright:

Available Formats

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

MISQ REVIEW

REVIEW: THE RESOURCE-BASED VIEW AND

INFORMATION SYSTEMS RESEARCH:

REVIEW, EXTENSION, AND SUGGESTIONS

1

FOR FUTURE RESEARCH

By: Michael Wade tical and conceptual foundations. As new

Schulich School of Business theories are brought into the field, particularly

York University theories that have become dominant in other

4700 Keele Street areas, there may be a benefit in pausing to assess

Toronto, ON M3J 1P3 their use and contribution in an IS context. The

CANADA purpose of this paper is to explore and critically

mwade@schulich.yorku.ca evaluate use of the resource-based view of the

firm (RBV) by IS researchers.

John Hulland

Graduate School of Business The paper provides a brief review of resource-

University of Pittsburgh based theory and then suggests extensions to

Pittsburgh, PA 15260 make the RBV more useful for empirical IS

U.S.A. research. First, a typology of key IS resources is

jhulland@katz.pitt.edu presented, and these are then described using six

traditional resource attributes. Second, we em-

phasize the particular importance of looking at

both resource complementarity and moderating

Abstract factors when studying IS resource effects on firm

performance. Finally, we discuss three consi-

Information systems researchers have a long tra- derations that IS researchers need to address

dition of drawing on theories from disciplines such when using the RBV empirically. Eight sets of

as economics, computer science, psychology, and propositions are advanced to help guide future

general management and using them in their own research.

research. Because of this, the information sys-

tems field has become a rich tapestry of theore- Keywords: Resource-based view, organizational

impacts of IS, information systems resources,

1 competitive advantage, IS strategic planning,

Jane Webster was the accepting senior editor for this

paper. information resource management

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 107-142/March 2004 107

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Introduction The Resource-Based

View of the Firm

In 1992, Mahoney and Pandian outlined how the

resource-based view of the firm (RBV) might be An Overview of the Resource-

useful to the field of strategic management. Based View

One benefit of the theory, they noted, was that

it encouraged a dialogue between scholars from

The resource-based view argues that firms pos-

a variety of perspectives, which they described

sess resources, a subset of which enables them

as good conversation. Since then, the

to achieve competitive advantage, and a further

strengths and weaknesses of the RBV have subset which leads to superior long-term per-

been vigorously debated in strategic formance (Barney 1991; Grant 1991; Penrose

management and other management disciplines 1959; Wernerfelt 1984). Empirical studies of firm

(e.g., Barney 2001; Fahy and Smithee 1999; performance using the RBV have found dif-

Foss 1998; Priem and Butler 2001a, 2001b). ferences not only between firms in the same

industry (Hansen and Wernerfelt 1989), but also

Very little discussion on the resource-based within the narrower confines of groups within

view, however, has been conducted in the field industries (Cool and Schendel 1988). This sug-

of information systems. The RBV has been gests that the effects of individual, firm-specific

used in the IS field on a number of occasions resources on performance can be significant

(see the Appendix for a list of IS research (Mahoney and Pandian 1992).

studies using the RBV), yet there has been no

effort to date to comprehensively evaluate its Resources that are valuable and rare and whose

strengths and weaknesses. This paper outlines benefits can be appropriated by the owning (or

how the RBV can be useful to research in IS, controlling) firm provide it with a temporary

and provides guidelines for how this research competitive advantage. That advantage can be

might be conducted. In short, the purpose of sustained over longer time periods to the extent

this paper is to initiate a discussion of the RBV that the firm is able to protect against resource

within the conversation of information systems imitation, transfer, or substitution. In general,

research. empirical studies using the theory have strongly

supported the resource-based view (e.g., McGrath

et al. 1995; Miller and Shamsie 1996; Zaheer and

The paper is organized as follows. First, we

Zaheer 1997).

briefly introduce the resource-based view of the

firm and describe how the theory has relevance

One of the key challenges RBV theorists have

for IS scholars. Second, we present a typology

faced is to define what is meant by a resource.

of IS resources and then describe, compare,

Researchers and practitioners interested in the

and contrast them with one another using six

RBV have used a variety of different terms to talk

key resource attributes. Third, we address the about a firms resources, including competencies

important issues of resource complementarity (Prahalad and Hamel 1990), skills (Grant 1991),

and the role played by moderating factors that strategic assets (Amit and Schoemaker 1993),

influence the IS resource-firm performance assets (Ross et al. 1996), and stocks (Capron and

relationship. We then turn to a discussion of Hulland 1999). This proliferation of definitions and

three major sets of considerations that IS classifications has been problematic for research

researchers need to address when using the using the RBV, as it is often unclear what

RBV in empirical settings. researchers mean by key terminology (Priem and

Butler 2001a). In order to simplify the interpre-

108 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

tation of the theory, it is useful to clarify the IS researchers and therefore it is valuable to

definitions of relevant terms. In this paper, we pause and reflect on the actual utility of the theory

define resources as assets and capabilities that to the IS field. That the theory has become

are available and useful in detecting and influential in other management fields such as

responding to market opportunities or threats strategy and marketing merely points to its

(Sanchez et al. 1996; see also Christensen and potential use in IS research. Usefulness in one

Overdorf 2000). Together, assets and capabilities field does not dictate usefulness in all fields.

define the set of resources available to the firm. Furthermore, the IS field already incorporates

theories from many other areas. This review will

Assets are defined as anything tangible or explore what, if anything, the RBV can offer that

intangible the firm can use in its processes for the IS field does not already obtain from

creating, producing, and/or offering its products elsewhere.

(goods or services) to a market, whereas capa-

bilities are repeatable patterns of actions in the use This review will argue that the RBV is indeed

of assets to create, produce, and/or offer products useful to IS research. The theory provides a

to a market (Sanchez et al. 1996). Assets can valuable way for IS researchers to think about how

serve as inputs to a process, or as the outputs of information systems relate to firm strategy and

a process (Srivastava et al. 1998; Teece et al. performance. In particular, the theory provides a

1997). Assets can be either tangible (e.g., cogent framework to evaluate the strategic value

information systems hardware, network of information systems resources. It also provides

infrastructure) or intangible (e.g., software patents, guidance on how to differentiate among various

strong vendor relationships) (Hall 1997; Itami and types of information systemsincluding the

Roehl 1987; Srivastava et al. 1998). In contrast, important distinction between information tech-

capabilities transform inputs into outputs of greater nology and information systemsand how to

worth (Amit and Schoemaker 1993; Capron and study their separate influences on performance

Hulland 1999; Christensen and Overdorf 2000; (Santhanam and Hartono 2003). Further, the

Sanchez et al. 1996; Schoemaker and Amit 1994).2 theory provides a basis for comparison between

Capabilities can include skills, such as technical or IS and non-IS resources, and thus can facilitate

managerial ability, or processes, such as systems cross-functional research.

development or integration.

Yet, as currently conceptualized, the theory is not

ideally suited to studying information systems.

Unlike some resources, such as brand equity or

What Can the Resource-Based View financial assets, IS resources rarely contribute a

Contribute to IS Research? direct influence to sustained competitive advant-

age (SCA). Instead, they form part of a complex

chain of assets and capabilities that may lead to

A critical issue addressed in this review is the

sustained performance. In the parlance of

usefulness of the resource-based view to IS

Clemons and Row (1991), information systems

research. The RBV is increasingly being used by

resources are necessary, but not sufficient, for

SCA. Information systems exert their influence on

the firm through complementary relationships with

2

In this paper we view the terms capabilities, compe- other firm assets and capabilities. While the RBV

tencies, and core competencies as essentially synony-

mous. According to Sanchez et al. (1996), the only

recognizes the role of resource complementarity,

difference between these terms lies in the fact that core it is not well developed in the theory. The

competencies are capabilities that achieve competitive refinement of this element is necessary to

advantage. Because we explicitly discuss only capa-

enhance the usefulness of the RBV to IS

bilities that lead to superior performance, in this paper the

terms can be considered interchangeable. researchers.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 109

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

We recognize three aspects of the RBV that list of RBV studies conducted to date in the IS

provide rare and valuable benefits to IS field). Much of this work has attempted to identify

researchers. First, by way of a defined set of and define either a single IS resource or sets of IS

resource attributes, the RBV facilitates the spe- resources. For example, Ross et al. (1996)

cification of information systems resources. This divided IS into three IT assets which together with

specification provides the groundwork for a set of IT processes would contribute to business value.

mutually exclusive and exhaustive information These three IT assets were labeled human assets

systems assets and capabilities. This review sug- (e.g., technical skills, business understanding,

gests a framework for this IS resource set. problem-solving orientation), technology assets

Second, by using the same set of resource (e.g., physical IT assets, technical platforms, data-

attributes mentioned above, IS resources can be bases, architectures, standards) and relationship

compared with one another and, perhaps more assets (e.g., partnerships with other divisions,

importantly, can be compared with non-IS client relationships, top management sponsorship,

resources. Thus, the RBV promotes cross-func- shared risk and responsibility). IT processes were

tional research through comparisons with other defined as planning ability, cost effective opera-

firm resources. Third, the RBV sets out a clear link tions and support, and fast delivery. This cate-

between resources and SCA through a well- gorization was later modified by Bharadwaj (2000)

defined dependent variable, providing a useful way to include IT infrastructure, human IT resources,

to measure the strategic value of IS resources. In

and IT-enabled intangibles.

addition, we recognize one area in which the

theory is deficient as conceivedthe

Other categorization schemes have also been

complementarity of resourcesand suggest a way

developed. (The Appendix summarizes these

to extend the theory to reduce the effect of this

studies. In Table 2, presented later in the paper,

deficiency. We also suggest key moderating

we offer an alternative way of categorizing these

variables that are relevant to studies of the IS

constructs.) Feeny and Willcocks (1998) iden-

resource-performance relationship and that we

tified nine core IS capabilities, which they

believe warrant greater attention from IS

organized into four overlapping areas. These

researchers.

areas were business and IT vision (integration

between IT and other parts of the firm), design of

IT architectures (IT development skills), delivery of

IS Resources and the Resource- IS services (implementation, dealing with vendors

and customers), and a core set of capabilities

Based View

which included IS leadership and informed buying.

This section starts by reviewing RBV research As a further step, each capability was ranked as to

conducted to date within the IS field, with an eye to how much it relied on business, technical, or

identifying the major IS resources used in these interpersonal skills. Bharadwaj et al. (1998) sug-

studies. These resources are then organized gested and subsequently validated a measure of

using a typology proposed by Day (1994). This is IT capability with the following six dimensions:

followed by a description of six key resource IT/business partnerships, external IT linkages,

attributes that have been employed by RBV business IT strategic thinking, IT business process

researchers in the past. Finally, we describe each integration, IT management, and IT infrastructure.

of the major IS resources identified previously Each dimension was found to be reliable and valid

using these six attributes. using psychometric testing on a sample of senior

IS executives.

Information Systems Resources The link between IS resources and firm perfor-

mance has been investigated by a number of

The resource-based view started to appear in IS researchers. For example, Mata et al. (1995)

research in the mid-1990s (see the Appendix for a used resource-based arguments to suggest that

110 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

five key IS driverscustomer switching costs, et al. 1998). From an RBV perspective, this

access to capital, proprietary technology, technical advantage may result from development of

IT skills, and managerial IT skillslead to sus- capabilities over an extended period of time that

tained competitive advantage, although they found become embedded in a company and are difficult

empirical support for only the last of these pro- to trade. Alternatively, the firm may possess a

posed relationships. Powell and Dent-Micallef capability that is idiosyncratic to the firm (i.e., an

IS expert with specialized knowledge who is loyal

(1997) divided information systems resources into

to the firm) or difficult to imitate due to path

three categories: human resources, business

dependencies (Dierickx and Cool 1989) or

resources, and technology resources. In a study of

embeddedness in a firms culture (Barney 1991).

the U.S. retail industry, they found that only human

Capabilities are often critical drivers of firm per-

resources in concert with IT contributed to formance (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Makadok

improved performance. Among the business 2001; Teece et al. 1997).

resources, only IT training positively affected

performance, while no technology resources linked

positively to performance at all.

A Typology of IS Resources

Using an approach similar to that employed by

Kohli and Jaworski (1990) to develop the mar- Day (1994) suggests one approach to thinking

keting orientation construct, Marchand et al. (2000) about IS resources. He argues that the capa-

proposed an information orientation construct bilities (as previously noted, a subset of the firms

resources) held by a firm can be sorted into three

comprised of three elements: information

types of processes: inside-out, outside-in, and

technology practices (the management of tech-

spanning. Inside-out capabilities are deployed

nology), information management practices (the

from inside the firm in response to market

management of information collection, organization

requirements and opportunities, and tend to be

and use), and information behaviors and values internally focused (e.g., technology development,

(behaviors and values of people using the cost controls). In contrast, outside-in capabilities

information). These factors were validated using are externally oriented, placing an emphasis on

data from a large-scale cross-sectional survey. anticipating market requirements, creating durable

The study also found that firms ranking highly on customer relationships, and understanding com-

all three information orientation dimensions tended petitors (e.g., market responsiveness, managing

to have superior performance when compared to external relationships). Finally, spanning capa-

other firms. bilities, which involve both internal and external

analysis, are needed to integrate the firms inside-

Many of the studies mentioned above divided IS out and outside-in capabilities (e.g., managing IS/

resources into two categories that can be broadly business partnerships, IS management and

defined as IS assets (technology-based) and IS planning). Such an approach is entirely consistent

capabilities (systems-based). Research has sug- with Santhanam and Hartonos (2003) recent call

gested that IS assets (e.g., infrastructure) are the to develop theoretically-based multidimensional

easiest resources for competitors to copy and, measures of IT capability.

therefore, represent the most fragile source of

sustainable competitive advantage for a firm Table 1 suggests how eight key IS resources

(Leonard-Barton 1992; Teece et al. 1997). In con- described in previous research can be organized

trast, there is growing evidence that competitive within this framework. While this earlier work has

advantage often depends on the firms superior used a variety of different terms for IS resources,

deployment of capabilities (Christensen and it can be mapped directly onto Days framework,

Overdorf 2000; Day 1994) as well as intangible as shown in Table 2. Each of the resources in this

assets (Hall 1997; Itami and Roehl 1987; Srivistava table is described more fully below.

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 111

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

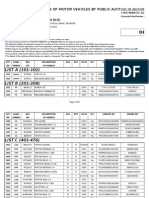

Table 1. A Typology of IS Resources

Outside-In Spanning Inside-Out

External relationship IS-business partnerships IS infrastructure

management IS planning and change IS technical skills

Market responsiveness management IS development

Cost effective IS operations

Table 2. A Categorization of Information Systems Resources from Previous Studies

Resource Source

Manage external Manage external linkages (Bharadwaj et al. 1998)

relationships Manage stakeholder relationships (Benjamin and Levinson 1993)

Strong community networks (Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1998)

Contract facilitation (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Informed buying (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Vendor development (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Contract monitoring (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Coordination of buyers and suppliers (Bharadwaj 2000)

Customer service (Bharadwaj 2000)

Market responsiveness Fast delivery (Ross et al. 1996)

Ability to act quickly (Bharadwaj 2000)

Increased market responsiveness (Bharadwaj 2000)

Responsiveness (Zaheer and Zaheer 1997)

Fast product life cycle (Feeny and Ives 1990)

Capacity to frequently update information (Lopes and Galletta 1997)

Strategic flexibility (Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1998)

Flexible IT systems (Bharadwaj 2000)

Organizational flexibility (Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997)

IS-business partnerships Integrate IT and business processes (Benjamin and Levinson 1993;

(manage internal Bharadwaj 2000; Bharadwaj et al. 1998)

relationships) Capacity to understand the effect of IT on other business areas

(Benjamin and Levinson 1993)

IT/business partnerships (Bharadwaj et al. 1998; Ross et al. 1996)

Aligned IT planning (Ross et al. 1996)

Business/IT strategic thinking (Bharadwaj et al. 1998)

IT/business synergy (Bharawdaj 2000; Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1998)

IT assimilation (Armstrong and Sambamurthy 1999)

Relationship building (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

IT/strategy integration (Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997)

112 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Table 2. A Categorization of Information Systems Resources from Previous Studies

(Continued)

IS planning and change IT management skills (Bharadwaj 2000; Bharadwaj et al. 1998; Mata et

management al. 1995)

Business understanding (Feeny and Willcocks 1998; Ross et al. 1996)

Problem solving orientation (Ross et al. 1996)

Business systems thinking (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Capacity to manage IT change (Benjamin and Levinson 1993)

Information management practices (Marchand et al. 2000)

Manage architectures/standards (Ross et al. 1996)

Architecture planning (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

IS infrastructure IT infrastructure (Armstrong and Sambamurthy 1999; Bharadwaj 2000;

Bharadwaj et al. 1998)

Proprietary technology (Mata et al. 1995)

Hard infrastructure (Benjamin and Levinson 1993)

Soft infrastructure (Benjamin and Levinson 1993)

Storage and transmission assets (Lopes and Galletta 1997)

Information processing capacity (Lopes and Galletta 1997)

Technology asset (Ross et al. 1996)

Information technology practices (Marchand et al. 2000)

IS technical skills Technical IT skills (Bharawdaj 2000; Feeny and Willcocks 1998; Mata et

al. 1995; Ross et al. 1996)

Knowledge assets (Bharadwaj 2000)

Using knowledge assets (Bharadwaj 2000)

IS development Technical innovation (Bharadwaj 2000)

Experimentation with new technology (Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1998)

Capacity to develop services that utilize interactive multimedia (Lopes

and Galletta 1997)

Alertness (Zaheer and Zaheer 1997)

Cost effective IS Cost effective operations and support (Ross et al. 1996)

operations Getting IT to function (Feeny and Willcocks 1998)

Enhanced product quality (Bharadwaj 2000)

Outside-In Resources tions, support, and/or customer service (Bharad-

waj 2000; Bharadwaj et al. 1998). Many large IS

External relationship management. This re- departments rely on external partners for a

source represents the firms ability to manage significant portion of their work. The ability to work

linkages between the IS function and stakeholders with and manage these relationships is an impor-

outside the firm. It can manifest itself as an ability tant organizational resource leading to competitive

to work with suppliers to develop appropriate sys- advantage and superior firm performance.

tems and infrastructure requirements for the firm

(Feeny and Willcocks 1998), to manage relation- Market responsiveness. Market responsiveness

ships with outsourcing partners (Benjamin and involves both the collection of information from

Levinson 1993; Feeny and Willcocks 1998), or to sources external to the firm as well as the dis-

manage customer relationships by providing solu- semination of a firms market intelligence across

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 113

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

departments, and the organizations response to Willcocks 1998; Ross et al. 1996), problem

that learning (Day 1994; Kohli and Jaworski solving orientation (Ross et al. 1996), and

1990). It includes the abilities to develop and capacity to manage IT change (Benjamin and

manage projects rapidly (Ross et al. 1996) and to Levinson 1993). It includes the ability of IS man-

react quickly to changes in market conditions agers to understand how technologies can and

(Bharadwaj 2000; Feeny and Ives 1990; Zaheer should be used, as well as how to motivate and

and Zaheer 1997). A key aspect of market manage IS personnel through the change process

responsiveness is strategic flexibility, which allows (Bharadwaj 2000).

the organization to undertake strategic change

when necessary (Bharadwaj 2000; Jarvenpaa and

Leidner 1998; Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997). Inside-Out Resources

IS infrastructure. Most studies recognize that

Spanning Resources many components of IS infrastructure (such as

off-the-shelf computer hardware and software)

IS-business partnerships. This capability repre- convey no particular strategic benefit due to lack

sents the processes of integration and alignment of rarity, ease of imitation, and ready mobility.

between the IS function and other functional areas Thus, the types of IS infrastructure mentioned in

or departments of the firm. The importance of IS most of the existing RBV-IS studies are either

alignment, particularly with business strategy, has proprietary or complex and hard to imitate

been well documented (e.g., Chan et al. 1997; (Benjamin and Levinson 1993; Lopes and Galletta

Reich and Benbasat 1996). This resource has 1997). Despite these attempts to focus on the

variously been referred to as synergy (Bharadwaj non-imitable aspects of IS infrastructure, the IS

2000; Jarvenpaa and Leidner 1999), assimilation infrastructure resource has generally not been

(Armstrong and Sambamurthy 1999), and partner- found to be a source of sustained competitive

ships (Bharadwaj et al. 1998; Ross et al. 1996). advantage for firms (Mata et al. 1995; Powell and

All of these studies recognize the importance of Dent-Micallef 1997; Ray et al. 2001).

building relationships internally within the firm

between the IS function and other areas or IS technical skills. IS technical skills are a result

departments. Such relationships help to span the of the appropriate, updated technology skills,

traditional gaps that exist between functions and relating to both systems hardware and software,

departments, resulting in superior competitive that are held by the IS/IT employees of a firm

position and firm performance. An element of this (Bharadwaj 2000; Ross et al. 1996). Such skills

resource is the support for collaboration within the do not include only current technical knowledge,

firm. but also the ability to deploy, use, and manage

that knowledge. Thus, this resource is focused on

IS planning and change management. The technical skills that are advanced, complex, and,

capability to plan, manage, and use appropriate therefore, difficult to imitate. Although the relative

technology architectures and standards also helps mobility of IS/IT personnel tends to be high, some

to span these gaps. Key aspects of this resource IS skills cannot be easily transferred, such as

include the ability to anticipate future changes and corporate-level knowledge assets (Bharadwaj

growth, to choose platforms (including hardware, 2000) and technology integration skills (Feeny and

network, and software standards) that can accom- Willcocks 1998), and, thus, these resources can

modate this change (Feeny and Willcocks 1998; become a source of sustained competitive

Ross et al. 1996), and to effectively manage the advantage. This capability is focused primarily on

resulting technology change and growth (Bharad- the present.

waj et al. 1998; Mata et al. 1995). This resource

has been defined variously in previous research IS development. IS development refers to the

as understanding the business case (Feeny and capability to develop or experiment with new

114 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

technologies (Bharadwaj 2000; Jarvenpaa and firm.3 For example, Barney (1991) suggested that

Leidner 1998; Lopes and Galletta 1997), as well advantage-creating resources must possess four

as a general level of alertness to emerging tech- key attributes: value, rareness, inimitability, and

nologies and trends that allow a firm to quickly non-substitutability. Other typologies have been

take advantage of new advances (Zaheer and proposed by Amit and Schoemaker (1993), Black

Zaheer 1997). Thus, IS development is future- and Boal (1994), Collis and Montgomery (1995),

oriented. IS development includes capabilities and Grant (1991). Although the terms employed

associated with managing a systems development across these frameworks are somewhat different,

life-cycle that is capable of supporting competitive all attempt to link the heterogeneous, imperfectly

advantage (Bharadwaj 2000; Marchand et al. mobile, and inimitable, firm-specific resource sets

2000; Ross et al. 1996), and should therefore lead possessed by firms to their competitive positions.

to superior firm performance. Before suggesting how the IS resources identified

above can be described using these attributes, we

Cost effective IS operations. This resource first discuss these attributes more generally as

encompasses the ability to provide efficient and they are viewed in the context of the RBV.

cost-effective IS operations on an ongoing basis.

Firms with greater efficiency can develop a long- Some researchers have made the useful dis-

term competitive advantage by using this capa- tinction between resources that help the firm attain

bility to reduce costs and develop a cost leader- a competitive advantage and those that help the

ship position in their industry (Barney 1991; Porter firm to sustain that advantage (e.g., Piccoli et al.

1985). In the context of IS operations, the ability 2002; Priem and Butler 2001a). Borrowing from

to avoid large, persistent cost overruns, unneces- terminology used by Peteraf (1993), these two

sary downtime, and system failure is likely to be types of resource attributes can be thought of as,

an important precursor to superior performance respectively, ex ante and ex post limits to compe-

(Ross et al. 1996). Furthermore, the ability to tition. Most previous research using the RBV has

develop and manage IT systems of appropriate blurred these two phases, but we believe that they

quality that function effectively can be expected to need to be considered separately.

have a positive impact on performance (Bharad-

waj 2000; Feeny and Willcocks 1998). Ex ante limits to competition suggest that prior to

any firms establishing a superior resource posi-

tion, there must be limited competition for that

position. If any firm wishing to do so can acquire

Resource Attributes and deploy resources to achieve the position, it

cannot by definition be superior. Attributes in this

In order to explore the usefulness of the RBV for category include value, rarity, and appropriability.

IS research, it is necessary to explicitly recognize Firm resources can only be a source of SCA when

the characteristics and attributes of resources that they are valuable. A resource has value in an

lead them to become strategically important. RBV context when it enables a firm to implement

Although firms possess many resources, only a strategies that improve efficiency and effective-

few of these have the potential to lead the firm to ness (Barney 1991). Resources with little or no

a position of sustained competitive advantage.

What is it, then, that separates regular resources

from those that confer a sustainable strategic 3

RBV theory is built on the assumption that all resource

benefit? RBV theorists have approached this attributes must be present for that resource to support a

question by identifying sets of resource attributes sustained competitive advantage. While most empirical

work using the RBV has supported this view, a few

that might conceptually influence a firms com- studies have found results that are inconsistent with this

petitive position. Under this view, only resources assumption (e.g., Ainuddin 2000; Poppo and Zenger

exhibiting all of these attributes can lead to a 1998). The key point here is that this assumption is

empirically testable, opening the RBV to potential

sustained competitive advantage (SCA) for the falsification (see also Barney 2001).

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 115

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

value have a limited possibility of conferring an another, forcing them to set lower prices than they

SCA on the possessing firm. To take an extreme might otherwise establish in order to win the

example, the use of a new, innovative paper clip business.

design may set one firm apart from others, but it is

unlikely the paper clip design would be valuable Ex post limits to competition mean that

from a competitive advantage standpoint.4 subsequent to a firms gaining a superior position

and earning rents, there must be forces that limit

Resources that are valuable cannot become competition for those rents (Hidding 2001; Peteraf

sources of competitive advantage if they are in 1993). Attributes in this category include imita-

plentiful supply. Rarity refers to the condition bility, substitutability, and mobility.

where the resource is not simultaneously available

to a large number of firms (Amit and Schoemaker In order to sustain a competitive advantage, firms

1993). For example, an ATM network might have must be able to defend that advantage against

significant value to a bank, but since it is not rare, imitation.6 The advantage accruing from newly

it is unlikely to confer a strategic benefit. developed features of computer hardware, for

instance, are typically short-lived since compe-

The appropriability of a resource relates to its rent titors are able to quickly duplicate the technology

earning potential (Amit and Schoemaker 1993; (Mata et al. 1995). According to Barney (1991),

Collis and Montgomery 1995; Grant 1991). The there are three factors that can contribute to low

advantage created by a rare and valuable imitability: unique firm history, causal ambiguity,

resource or by a combination of resources may and social complexity. The role of history recog-

not be of major benefit if the firm is unable to nizes the importance of a firms unique past, a

appropriate the returns accruing from the advan- past that other firms are no longer able to

tage. Technical skills provide an example of this duplicatethe so-called Ricardian argument. For

phenomenon. The additional benefit accruable to example, a firm might purchase a piece of land at

a firm from hiring employees with rare and valu- one point in time that subsequently becomes very

able technical skills may be appropriated away by valuable (Hirshleifer 1980; Ricardo 1966). Causal

the employee through higher than normal wage ambiguity exists when the link between a resource

demands.5 Similarly, a computer component and the competitive advantage it confers is poorly

supplier may be unable to enjoy the benefits of understood. This ambiguity may lie in uncertainty

improved cost efficiencies if the computer manu- about how a resource leads to SCA, or it may lie

facturer (i.e., the buyer) is sufficiently powerful to in lack of clarity about which resource (or

appropriate away such benefits. This might be combination of resources) leads to SCA. Such

done by sharing the learning with other suppliers, ambiguity makes it extremely hard for competing

or by pitting more efficient suppliers against one firms to duplicate a resource or copy the way in

which it is deployed (Alchian 1950; Barney 1986

1991; Dierickx and Cool 1989; Lippman and

4 Rumelt 1982; Reed and DeFillipe 1990). If a firm

An extensive discussion of the concept of value in

relation to resource-based theory has been conducted in understands how and why its resources lead to

the strategic management literature (Barney 2001; Priem SCA, then competing firms can take steps to

and Butler 2001a, 2001b; Makadok 2001). Most of this acquire that knowledge, such as hiring away key

discussion has focused on whether or not value can be

determined endogenously to the theory. The contention

personnel, or closely observing firm processes

that resource value is a pre-cursor to SCA has not been and outcomes. Finally, social complexity refers to

in dispute. the multifarious relationships within the firm and

5

For example, firms attempting to hire ERP-knowledge-

able personnel during the 1999-2000 period discovered

6

that they were able to appropriate only part of the It is important to note, however, that firms may not

potential rents associated with this resource, with the always be able to mount such defenses as a result of

balance appropriated by the employees themselves (in either not fully understanding the threat of imitation or

the form of higher wages or compensation). not having the necessary resources to counter it.

116 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

between the firm and key stakeholders such as puter hardware and software, are relatively easy

shareholders, suppliers, and customers (Hambrick to acquire. Technical knowledge, managerial

1987; Klein and Lefler 1981). The complexity of experience, and many skills and abilities are less

these relationships makes them difficult to easy to obtain. Other resources, such as

manage and even more difficult to imitate. An company culture, brand assets, and so on, may

example of this is Wal-Marts logistics manage- only be available if the firm itself is sold (Grant

ment system. Even if all the individual elements 1991).

are in place, the relationships between the

elements, and thus its complexity, would likely The preceding attributesboth ex ante and ex

result in an imperfect substitute (Dierickx and Cool postare summarized in Table 3. Conceptually,

1989). the two types of resource attributes are related.

When a resource is imitated, more of that

A resource has low substitutability if there are few, resource exists than before, and thus it becomes

if any, strategically equivalent resources that are, less rare. Resources that are highly mobile may

themselves, rare and inimitable (Amit and be acquired by competing firms, again affecting

Schoemaker 1993; Black and Boal 1994; Collis the rarity of the resource for that firm (but not its

and Montgomery 1995). Firms may find, for overall rarity in the marketplace). Substitutability,

example, that excellence in IS product develop- by contrast, affects resource value, not rarity.

ment, systems integration, or environmental Resources do not become less rare by having

scanning may be achieved through a number of multiple substitutes; however, their value can be

equifinal paths. expected to diminish as substitute resources are

developed. This conceptualization is shown in

Once a firm establishes a competitive advantage Figure 1.8

through the strategic use of resources, com-

petitors will likely attempt to amass comparable

resources in order to share in the advantage. A

primary source of resources is factor (i.e., open) IS Resource Attributes

markets (Grant 1991). If firms are able to acquire

the resources necessary to imitate a rivals In this section, we use the resource attributes

competitive advantage, the rivals advantage will introduced above to describe the IS resources

be short-lived. Thus, a requirement for sustained identified earlier in the paper. The relationships

competitive advantage is that resources be between these resources and their attributes are

imperfectly mobile or non-tradable (Amit and summarized in Table 4. The entries in this table

Schoemaker 1993; Barney 1991; Black and Boal should be interpreted in relative (i.e., versus other

1994; Dierickx and Cool 1989).7 Some resources

are more easily bought and sold than others.

Technological assets, for example, such as com- 8

It is important to recognize that imitability and imperfect

mobility or tradability are distinct resource attributes.

The former prevents imitation by competitors of a firms

critical resources via direct copying or innovation. This

7

Resource mobility and tradability are closely related can be due to causal ambiguity, lack of relevant

constructs. As Peteraf (1993, p. 183) notes, resources resources on the part of the potential imitator, and time-

are perfectly immobile if they cannot be traded. On the competitive pressures (Braney 1991; Dierickx and Cool

other hand, imperfectly mobile resources are not 1989). In contrast, imperfect mobility prevents the

commonly, easily, or readily exchanged on the market acquisition and transfer of key resources from one firm

(Capron and Hulland 1999, p. 42), even though they are to another. Whereas resource imitability leads to an

tradable. Such barriers to mobility can arise as a result increase in the availability of a critical resource (thus

of switching costs (Montgomery and Wernerfelt 1988), undermining its rarity), resource mobility describes the

resource co-specialization (Teece 1986), and/or high degree to which an existing, fixed stock of a key

transactions costs (Rumelt 1987). We prefer use of the resource can be transferred between firms. This distinc-

term resource mobility over resource tradability here tion has been clearly recognized in previous RBV work

because the former is a more finely grained construct (e.g., see Dierickx and Cool 1989; Dutta et al. 1999;

than the latter. Peteraf 1993).

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 117

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Table 3. Resource Attributes

Resource Attribute Terminology

Ex ante limits to competition

Value Value (Barney 1991; Dierickx and Cool 1989)

Rarity Rare (Barney 1991)

Scarcity (Amit and Shoemaker 1993)

Idiosyncratic assets (Williamson 1979)

Appropriability Appropriability (Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Collis and Montgomery 1995;

Grant 1991)

Ex post limits to competition

Imitability Imperfect imitability: history dependent, causal ambiguity, social

complexity (Barney 1991)

Replicability (Grant 1991)

Inimitability (Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Andrews 1971; Collis and Mont-

gomery 1995)

Uncertain imitability (Lippman and Rumelt 1982)

Social Complexity (Fiol 1991)

Causal ambiguity (Dierickx and Cool 1989)

Substitutability Non-substitutability (Barney 1991)

Transparency (Grant 1991)

Substitutability (Collis and Montgomery 1995)

Limited substitutability (Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Dierickx and Cool

1989)

Substitutes (Black and Boal 1994)

Mobility Imperfect mobility (Barney 1991)

Transferability (Grant 1991)

Low tradability (Amit and Shoemaker 1993; Dierickx and Cool 1989)

Tradability (Black and Boal 1994)

118 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Table 4. IS Resources, by Attribute

Advantage Creation Advantage Sustainability

Value Rarity Appropriability Imitability Substitutability Mobility

Outside-In

External

relationship H MH LM L LM L

management

Market

H MH LM L LM L

responsiveness

Spanning

IS-business

H MH LM L LM L

partnerships

IS management/

planning H MH LM LM LM M

Inside-Out

IS infrastructure MH LM H H LM H

IS technical skills MH LM M M MH MH

IS development MH M M M MH M

Cost efficient IS

MH LM M LM MH M

operations

Note: L = low; M = medium, H = high

time

Competitive Advantage Phase Sustainability Phase

Productive Is sustained

use of firm over

resources leads to Short term which time due to

which are competitive resource

-valuable advantage -imitability

-rare -substitutability

-appropriable -mobility

Ex ante limits to competition Ex post limits to competition

value sustains Low substitutability

Low mobility

rarity sustains

Low imitability

Figure 1. The Resource-Based View Over Time

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 119

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

entries in the same table) rather than absolute markets, and must instead be developed through

terms. We emphasize that this table is based on on-going, firm-specific investments or through

limited existing empirical evidence and therefore mergers and/or acquisitions of other companies.

describes hypothesized rather than proven

relationships.

Appropriability

Value Although it is difficult to determine the exact

degree of appropriability associated with each IS

As noted earlier, all of the IS resources described resource, a number of general observations seem

here have at least moderate value to the firms that warranted based on past research. First, IS infra-

possess them. For example, the studies by structure, technology skills, IS development, and

Bharadwaj (2000), Feeny and Willcocks (1998), cost efficiency may be appropriable, rent-gene-

Lopes and Galletta (1997), and Marchand et al. rating resources in the short term, particularly

(2000), Mata et al. (1995), and Ross et al. (1996) when the firm possessing the IS resource has a

have all shown that IS resources have value to first-mover advantage in its use, and competitors

their firms (albeit not always realized). At the find such uses difficult to wrest away from the

same time, outside-in and spanning resources advantaged firm. For example, firms that are first

seem to have potentially higher value than inside- to possess next-generation hardware and soft-

out resources to firms. The reason for this is that ware are typically able to use this new infra-

the two former sets of resourcesif valuable structure to improve firm efficiency and/or effec-

must be based on a continued understanding of tiveness, thereby enhancing short-term compe-

the changing business environment. While inside- titive advantage and rent-earning potential.

out resources can lead to greater efficiency and/or Second, the appropriability of the outside-in and

effectiveness at any particular point in time, it is spanning resources tends to be lower than that of

essential for the firm to track and respond to the the inside-out resources. This stems from the fact

changing business environment over time if it is to that they tend to be organizationally complex, and

attain a sustainable competitive advantage. thereby more difficult to deploy successfully.

Rarity Imitability

In general, the key IS resources described here Over time, some IS resources become easier to

are all likely to be relatively rare. However, as imitate than others. The outside-in and spanning

was the case for the value attribute, outside-in and resources (particularly IS-business partnerships)

spanning resources are likely to be associated are likely to be more difficult to imitate because

with a higher degree of rarity than are inside-out both sets of resources will develop and evolve

resources. The underlying reason for this is that uniquely for each firm. Moreover, these resources

available labor markets allow firms lacking key IS are likely to be socially complex. In contrast, firms

technology, operational efficiency skills, and IS are likely to be able to develop technology skills

development personnel resources to acquire them and IS development capabilities through the hiring

by offering superior wages or through business of relevant expertise via existing labor markets or

arrangements with external consultants. Similarly, by interacting with external consulting firms.

IS infrastructure can be acquired or copied rela- Although less readily available, the IS manage-

tively easily once it has been in existence even for ment/planning and cost efficiency capabilities may

a comparatively short period of time, although it also be available through such means. Thus,

may be very rare initially. In contrast, spanning these latter resources will be more imitable than

and outside-in resources tend to be socially the outside-in and IS-business partnership

complex and cannot be easily acquired in factor resources, but less imitable than the technology

120 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

skills and IS development capability. Finally, acquired via the marketplace; thus, they are also

existing empirical evidence suggests that IS relatively mobile. In contrast, the external rela-

infrastructure is particularly easy to imitate over tionship management, market responsiveness,

moderate to longer time periods. and IS-business partnership capabilities are

generally not readily available in factor markets.

Therefore, the mobility of these latter three

Substitutability resources is expected to be low.

The key question that one needs to answer in

considering substitutability is whether or not a

strategically equivalent resource exists and is IS Resource Attribute Propositions

potentially available to the firm while leading to an

equifinal outcome. This may involve the use of Two key implications emerge from the preceding

very different resource sets, but could also reflect discussion. First, it is important to recognize the

a decision to acquire and deploy resources in- fundamental difference that can exist between a

house versus obtaining them from third parties. In resources initial and longer-term impact on a

the case of IS infrastructure, it seems unlikely that firms competitive position. Second, Table 4

strategic alternatives exist that lead to the same suggests that both similarities and differences

ultimate competitive position. Thus, the substitu- exist between distinct types of IS resources (cf.

tability of this resource will be low. At the other Santhanam and Hartono 2003). Each of these

extreme, firms may be able to outsource their IS implications is examined in turn below.

development and other operations to third parties,

and thereby compete effectively. Strategic substi-

tutes for the outside-in and spanning resources Resource Creation Versus Sustainability

are also likely to be rare, although it may be

possible for firms with a subset of these capa- Although various studies have examined how IS

bilities (e.g., market responsiveness) to compete resources can potentially create competitive

on an equal basis with firms possessing a different advantage for firms, very little of this work has

subset (e.g., IS-business partnerships). looked at sustaining that advantage over time. In

fact, Kettinger et al. (1994) concluded that many

of the success stories attributed to new IT

Imperfect Mobility configurations were only successful for a short

period of time. Similarly, early arguments sug-

This final resource attribute captures the extent to gesting that a so-called first-mover advantage, if

which the underlying resource can be acquired maintained, could lead to sustained advantage

through factor markets. IS infrastructure, once (e.g., Feeny and Ives 1990) were later challenged.

established, is easily disseminated to other firms, In order to sustain a first-mover advantage, firms

and is thus highly mobile.9 Technology skills, as would need to become perpetual innovators, a

well as the IS development, cost efficiency, and IS role that may be untenable (Kettinger et al. 1994).

management/planning capabilities can all be More focus on the sustainability of IS resources is

clearly warranted (Willcocks et al. 1997).10

9

Note that this statement assumes that IS hardware is a

10

discrete and separable part of the firms overall IS Defining precisely what is meant by the term sustain-

resource set, and that it can be transferred from one firm able is trickier than it might first appear. Barney (1991,

to another with relative ease. However, as one reviewer p. 102) clearly states that a sustained competitive

noted, this may only be a recent phenomenon. Old, pre- advantage is one that continues to exist after efforts to

ERP collections of legacy systems and databases were duplicate that advantage have ceased, and that this

far more difficult to either imitate (due to organizational definition of SCA is equilibrium-based. However, as

complexity; Barney 1991) or acquire (due to co- Wiggins and Ruefli (2002, p. 84) note, while Barneys

specialization; see Barney 2001; Teece 1986). definition is theoretically precise, it has proven to be

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 121

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

As we noted earlier, the ex post notions of operations).11 Furthermore, because it is harder

resource imitability, substitutability, and mobility to imitate, acquire, or find strategic substitutes for

affect the ex ante notion of rarity. As resources the former set of resources than for the latter,

are copied and traded, they become less rare outside-in and spanning resources are more likely

(even when they maintain their value and appro- to maintain their rarity, and thus support a sus-

priability). Because resource rarity is critical to the tainable competitive position for a longer period of

maintenance of longer-term competitive advan- time. Thus:

tage, we predict the following:

Proposition 2: Outside-in and span-

Proposition 1: Only IS resources ning IS resources will have a stronger

that are (1) inimitable, (2) non-substi- impact than inside-out IS resources

tutable, and (3) imperfectly mobile will on initial competitive position.

have a positive effect on competitive

position in the longer term. Proposition 3: Outside-in and span-

ning IS resources will have a more

enduring impact than inside-out IS

Outside-In Versus Spanning Versus resources on long-term competitive

Inside-Out Resources position.

Proposition 1 is very general, and applies to both A disproportionate share of the existing work

IS and non-IS resources. Our earlier review of IS within IS looking at the link between IS resources

resources suggests, however, that more specific and firm performance or competitive position has

predictions can be made for different types of focused either primarily or exclusively on those

resources. In particular, visual inspection of resources that we have characterized above as

Table 4 suggests that outside-in and spanning inside-out resources. However, the preceding

resources tend to have similar resource attributes. discussion suggests strongly that the key drivers

In general, when compared to inside-out re- of a longer-term competitive position are more

sources, they tend to have somewhat greater likely to be the result of superior outside-in and

value, be rarer (but less appropriable), be more spanning resources, whereas those resources

difficult to imitate or acquire through trade, and that have received the greatest attention to date

have fewer strategic substitutes. Focusing for a tend to be more transitory in their impact on

moment on the first two of these attributes, this performance. Thus, one key conclusion to be

suggests that firms possessing superior external drawn from our review is that greater attention

relations, market responsiveness, IS-business needs to be paid to all types of IS resources, and

partnership, and IS management/planning re- not just those that are internally focused (Straub

sources are likely to initially outperform com- and Watson 2001). This does not mean that

petitors that rely more on resources that are resources such as IS infrastructure, technology

internally focused (e.g., IS infrastructure, tech- skills, IS development, and cost efficiency should

nology skills, IS development, and cost efficient be ignored, but that their effects on competitive

position and/or performance should be examined

jointly with those of other, less inwardly focused IS

(and non-IS) resources.

virtually impossible to meaningfully operationalize quan-

11

titatively. Others (e.g., Jacobsen 1988; Porter 1985) This initial period will typically be relatively short in

have suggested that a sustained competitive advantage duration (e.g., 6 months to 1 year), representing the time

is a competitive advantage that endures for a longer required for competitors to imitate or acquire the

period of calendar time. In this section, we adopt the necessary resource(s). If these can be quickly attained

latter perspective in order to develop empirically testable or duplicated, then the short-term competitive advantage

propositions. We discuss this point in more detail in the will prove to be fleeting, representing little more than a

section on using the RBV in IS research. first-mover advantage.

122 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Potential Moderators concede that IT-based success rests on the ability

to fit the pieces together but offer little guidance

The discussion thus far has assumed that IS on how this might happen. Jarvenpaa and

resources directly affect the performance and/or Leidner (1998) note that IT can generate compe-

competitive advantage of the firm. However, there titive value only if deployed so that it leverages

is considerable and growing evidence to suggest preexisting business and human resources in the

that these effects may be more correctly viewed firm via co-presence or complementarity. Yet, the

as both contingent and complementary. We begin process by which IS resources interact with other

this section by discussing the issue of resource firm resources is poorly understood, as is the

complementarity in general, and then turn to an nature of those resources (Ravichandran and

identification of key moderators that we believe Lertwongsatien 2002).

can affect the IS resource-performance relation-

ship. While recognized by various RBV theorists as

important, the role of resource complementarity

within the theory has not been extensively

developed (Amit and Schoemaker 1993; Dierickx

Resource Complementarity and Cool 1989; Teece 1986). Complementarity

refers to how one resource may influence another,

Conceptual and empirical development of the and how the relationship between them affects

RBV as outlined above has resulted in a useful competitive position or performance (Teece 1986).

way to analyze the strategic value of resources. Black and Boal (1994) note that resources can

The further subdivision of resource attributes into have one of three possible effects on one another:

those that help to create a competitive advantage compensatory, enhancing, or suppressing/ de-

and to sustain such an advantage once created stroying. A compensatory relationship exists

helps to account for changes in performance over when a change in the level of one resource is

time. However, the RBV as currently conceived offset by a change in the level of another

fails to adequately consider the fact that resources resource. An enhancing relationship exists when

rarely act alone in creating or sustaining compe- one resource magnifies the impact of another

titive advantage. This is particularly true of IS resource. A suppressing relationship exists when

resources that, in almost all cases, act in con- the presence of one resource diminishes the

junction with other firm resources to provide impact of another.

strategic benefits (Ravichandran and

Lertwongsatien 2002). For example, Powell and Although not based on resource theory, the

Dent-Micallef (1997) concluded that the comple- strategic information technology (SIT) area of

mentary use of IT and human resources lead to research is a rich source of evidence that can be

superior firm performance, and Benjamin and used to illustrate the importance of the resource

Levinson (1993) concluded that performance complementarity issue. In particular, a review of

depends on how IT is integrated with organiza- research in this area clearly demonstrates that

tional, technical, and business resources. possession of superior IS resources is not

inevitably linked to enhanced performance. Since

The issue of complementarity is an important one the 1950s, the influence of IT on organizations

since it implies a more complex role for IS (Ackoff 1967; Argyris 1971; Dearden 1972; Gorry

resources within the firm (Alavi and Leidner 2001; and Scott-Morton 1971; Keen 1981; Leavitt and

Henderson and Venkatraman 1993). In the same Whisler 1958), both positive and negative, has

way that IT software is useless without IT hard- been hotly debated. The study of information

ware (and vice versa), IS resources play an technology as a driver of competitive advantage

interdependent role with other firm resources began to take hold in the 1980s (e.g., Bakos and

(Keen 1993; Walton 1989). Yet, the nature of this Treacy 1986; McFarlan 1984). A number of case

role is largely unknown. Kettinger et al. (1994) studies in the mid- to late-1980s appeared to sup-

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 123

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

port the notion of information technology as a to be a top priority of researchers interested in

direct contributor of competitive advantage (e.g., applying the RBV in an IS context. Indeed, at the

Brady 1986; Copeland and McKenney 1988; Short moment three competing propositions can be

and Ventaktaman 1992). However, more recent articulated:

studies have challenged these conclusions by

suggesting contingent effects of IT resources on Proposition 4a: IS resources directly

performance (e.g., Carroll and Larkin 1992; Ket- influence competitive position and

tinger et al. 1994; Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997). performance.

Table 5 summarizes the SIT empirical literature to Proposition 4b: IS resources influ-

date that relates IT to performance or competitive ence competitive position and perfor-

advantage. Two general conclusions can be mance both directly and indirectly

drawn from this table. First, for those studies through interactions with other con-

finding a direct relationship between IT and structs (including other resources).

performance, the vast majority have reported a

positive effect (e.g., Banker and Kauffman 1991; Proposition 4c: IS resources influ-

Mahmood 1993). In contrast, few studies have ence competitive position and perfor-

indicated null or negative effects (for exceptions, mance only indirectly through inter-

see Sager 1988; Venkatraman and Zaheer 1990; actions with other constructs (in-

Warner 1987). cluding other resources).

Second, a greater number of the SIT studies Although only one of these propositions can be

summarized in Table 5 have found a contingent correct, existing studies do not definitively support

effect of IT on performance than have found a one over the other two. The SIT literature as well

direct effect. In some cases, SIT has been noted as a number of key resource-based studies within

to have both a direct effect on performance as IS appear to lend support for proposition 4b, while

well as an interactive effect with other constructs. researchers are increasingly skeptical of pro-

In other cases, only the interactive effects are position 4a. The essential question that remains

significant, particularly over the longer term. From unansweredand that deserves researcher

this, it seems clear that information systems attentionis whether proposition 4b or 4c is more

infrequently contribute directly and solely to sus- correct. Clemons and Row (1991) have argued in

tained firm performance. While information tech- favor of the latter, but the empirical findings to

nology may be essential for firms to compete, it date do not consistently support this perspective.

conveys no particular sustainable advantage to It is our belief that RBV theory can be useful in

one firm over its rivals. This sentiment is con- helping researchers to design future studies

sistent with the strategic necessity hypothesis aimed at resolving this ongoing debate.

proposed by Clemons and Row (1991).

While the SIT research stream is not based on

resource-based logic, its conclusions helpfully Potential Moderators

inform the debate around resource comple-

mentarity. From the preceding discussion, it Moderators that have the potential to affect the

seems clear that there will be conditions under relationship between key IS resources and per-

which specific IS resources must interact with formance can be separated into organizational

other resources (IS and/or non-IS) if they are to factors (i.e., those that operate within the firm) and

confer competitive advantage on the firm, both in environmental factors (i.e., those that operate out-

the immediate and longer terms. However, at side the firms boundaries). Top management

present the relevant set of moderating constructs commitment has been identified as a moderating

is not well established; we suggest that this needs factor within the organization. Similarly, environ

124 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Table 5. Summary of the Effects of Strategic Information Technology on Firm

Performance

Outcome Effect Relevant Studies

Direct and Positive

Strategic information technology has a Banker and Kauffman (1991); Bharadwaj (2000); Clemons

direct and positive effect on competitive and Weber (1990); Floyd and Woolridge (1990); Jelassi and

advantage or performance Figgon (1994); Mahmood (1993); Mahmood and Mann

(1993); Mahmood and Soon (1991); Roberts et al. (1990);

Silverman (1999); Tavakolion (1989); Tyran et al. (1992);

Yoo and Choi (1990)

Direct and Negative

Strategic information technology has a Warner (1987)

negative effect on competitive

advantage or performance

No Effect

Strategic information technology has no Sager (1988); Venkatraman and Zaheer (1990)

impact on competitive advantage or

performance

Contingent Effect

The effect of strategic information Banker and Kauffman (1988); Carroll and Larkin (1992);

technology on competitive advantage or Clemons and Row (1988); Clemons and Row (1991);

performance depends on other Copeland and McKenney (1988); Feeny and Ives (1990);

constructs Henderson and Sifonis (1988); Holland et al. (1992);

Johnston and Carrico (1988); Kettinger et al. (1994);

Kettinger et al. (1995); King et al. (1989); Lederer and Sethi

(1988); Li and Ye (1999); Lindsey et al. (1990); Mann et al.

(1991); Neo (1988); Powell and Dent-Micallef (1997); Reich

and Benbasat (1990); Schwarzer (1995); Short and

Venkatraman (1992)

mental turbulence, environmental munificence, Dent-Micallef 1997). In general, a top manage-

and environmental complexity have been pro- ment team that promotes, supports, and guides

posed as key moderating environmental factors. the IS function is perceived to enhance the impact

Each of these moderators is discussed in turn of IS resources on performance (Armstrong and

below. Sambamurthy 1999; Ross et al. 1996). For

example, Neo (1988) found that the use of stra-

tegic information technologies could lead to

Organizational Factors strategic advantage subject to management vision

and support. When such support is lacking, IS

Top Management Commitment to IS. This resources will have little effect on competitive

construct relates primarily to having commitment position or performance, even when substantial

from top management for IS initiatives (Powell and investments are made to acquire or develop such

MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004 125

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

resources. Conversely, strong top management Environmental Turbulence. In turbulent, fast

support should facilitate a strong IS resource- changing environments, different assets and

performance link. Thus: capabilities than those needed in more stable

environments are required to achieve superior

Proposition 5: Strong top manage- performance (Eisenhardt and Martin 2000; Teece

ment commitment to IS will interact et al. 1997; Volberda 1996). In a relatively stable

with IS resources to positively affect business environment, the bulk of managements

performance. effort is put toward creating competitive advantage

for the firm. Because the environment in this case

changes slowly, any advantage achieved by a firm

Other Organizational Factors. Top manage- is likely to be sustained over an extended period

ment commitment has been clearly identified in of time (Miller and Shamsie 1996). By contrast, in

the IS literature as affecting the relationship a turbulent environment, many advantages are

between IS resources and firm-level competitive short-lived as competitive and environmental

advantage. However, there are other factors that pressures quickly undermine any resource value

may also moderate this relationship in specific or heterogeneity (Foss 1998). The ability to stay

contexts. For example, there is some evidence on top of business trends and to quickly respond

that organizational structure affects the role of IS to changing market needs is critical for superior

resources within a firm (Fielder et al. 1996; Leifer firm performance in such environments.

1988; Sambamurthy and Zmud 1999). Corporate

culture, particularly as it relates to the level of Firms faced with more stable environments have

innovation within a firm, has been shown to influ- a tendency to emphasize static efficiency at the

ence the effectiveness of information system expense of dynamic efficiency (Ghemawat and

adoption and use (Barley 1990; Orlikowski 1996). Costa 1993). Such firms prefer to exploit existing

Other factors such as firm size, location, and knowledge and capabilities rather than explore

industry may also influence how information new possibilities (Leonard-Barton 1992; Levinthal

systems resources affect firm performance and and March 1993; Levitt and March 1988). In

competitive advantage. The extent to which these general, these will be inside-out (i.e., IT tech-

or other factors play a role in the IS resource-firm nology skills, IT development, cost efficiency, IS

performance relationship could become a subject infrastructure) rather than outside-in or spanning

of future research. resources. Thus, in more stable environments,

inside-out resources will be emphasized and be a

stronger determinant than outside-in or spanning

Environmental Factors resources of superior firm performance.

The relationship between IS resources and firm Proposition 6a: T h e r e l a t i o n s h i p

performance is affected not only by internal between inside-out resources and

elements such as top management commitment performance will be stronger for firms

and corporate culture, but also by environmental in stable business environments than

factors. These factors reflect the uncertainty in an for firms in turbulent business en-

organizations operating environment. Drawing on vironments; but

the work of Aldrich (1979), Child (1972), and

Pfeffer and Salancik (1978), Dess and Beard Proposition 6b: T h e r e l a t i o n s h i p

(1984) concluded that three dimensions of the between outside-in resources and

environment contribute most to environmental performance will be stronger for firms

uncertainty and are thus most likely to consistently in turbulent business environments

influence firm performance over time: environ- than for firms in stable business

mental turbulence, munificence, and complexity. environments; and

126 MIS Quarterly Vol. 28 No. 1/March 2004

Wade & Hulland/Review: Resource-Based View of IS Research

Proposition 6c: The relationship and a firms competitive position. Thus, we only

between spanning resources and propose the following moderating effect for

performance will be stronger for firms environmental munificence (although we believe

in turbulent business environments that its effect on all three types of resources

than for firms in stable business should be studied empirically):

environments.

Proposition 7: The relationship

Environmental Munificence. Environmental between inside-out resources and

munificence refers to the extent to which a busi- performance will be stronger for firms

ness environment can support sustained growth in low munificent environments than

(Dess and Beard 1984). Environments that are for firms in high munificent envi-

mature or shrinking are normally characterized by ronments.

low levels of munificence, whereas rapidly growing

markets are typically associated with a high Environmental Complexity. Environmental

degree of munificence. When munificence is low, complexity refers to the heterogeneity and range

stiff competition often exists that can adversely of an industry and/or an organizations activities

affect the attainment of organizational goals, or (Child 1972). It can refer variously to the number

even organizational survival (Toole 1994). In such of inputs and outputs required for an organi-

environments, firms frequently strive to maintain zations operations, the number and types of

profits by maximizing internal efficiencies. Inside- suppliers, consumers and competitors that it

out IS resources such as cost effective IS opera- interacts with, and so on. Complexity makes it

tions play a key role in affecting competitive more difficult for firms to both identify and

position in these cases by reducing costs and understand the key drivers of performance. From

streamlining operations. In contrast, while the RBV perspective, such ambiguity makes it

outside-in and spanning IS resources can poten- more difficult for competing firms to identify these

tially support organizational goals by helping to critical resources for potential imitation, acqui-

monitor changes in the external environment to sition, or substitution. Thus, under conditions of

coordinate internal responses to such changes, high environmental complexity, the link between

the absence of munificence puts pressure on key resources and superior performance will tend

organizations to reduce investments in outside-in to be stronger and more enduring.

and spanning resources. Furthermore, since low

munificence environments tend to be relatively This effect is likely to be important for all three

mature, firms may be tempted to assume a static types of resources. Organizations operating in

competitive picture and to focus more attention on highly complex environments must rely on efficient

inside-out capabilities that support improvements and effective systems to manage information and