Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Scrisdsf

Scrisdsf

Uploaded by

KateBarrionEspinosaCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Laurel v. Garcia DigestDocument2 pagesLaurel v. Garcia DigestAbi Bernardino100% (11)

- Laurel v. Garcia, GR No. 92013, 92047Document2 pagesLaurel v. Garcia, GR No. 92013, 92047Amicah100% (3)

- Property - Laurel v. GarciaDocument4 pagesProperty - Laurel v. GarciaPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST Laurel Vs GarciaDocument2 pagesCASE DIGEST Laurel Vs GarciaErica Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- How to Transfer Real Property Ownership in the PhilippinesFrom EverandHow to Transfer Real Property Ownership in the PhilippinesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Application Data SheetDocument4 pagesApplication Data SheetThedford I. HItafferNo ratings yet

- Telenor's Agreement On Responsible Business ConductDocument10 pagesTelenor's Agreement On Responsible Business ConductThan Htaik AungNo ratings yet

- Abacus Securities Corporation v. Ruben AmpilDocument2 pagesAbacus Securities Corporation v. Ruben AmpilRafael100% (1)

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaBeatrice AbanNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument5 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaDolores PulisNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs Garcia and DENR Vs YAPDocument12 pagesLaurel Vs Garcia and DENR Vs YAPMariko IwakiNo ratings yet

- Facts: The Subject Roppongi Property Is One of The Four Properties in Japan Acquired by The Philippine Government Under TheDocument62 pagesFacts: The Subject Roppongi Property Is One of The Four Properties in Japan Acquired by The Philippine Government Under TheMarianne FelixNo ratings yet

- Chapter VDocument20 pagesChapter VRessie June PedranoNo ratings yet

- 09 - Laurel v. Garcia - LiaoDocument2 pages09 - Laurel v. Garcia - LiaoRalph Deric EspirituNo ratings yet

- Public v. Private PropertyDocument3 pagesPublic v. Private PropertyMarvin TuasonNo ratings yet

- Torts and CrimesDocument14 pagesTorts and CrimesCheer SNo ratings yet

- Law On Property: Case Reporting By: Espinosa, Von Leslie LDocument10 pagesLaw On Property: Case Reporting By: Espinosa, Von Leslie LLeslie EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Salvador Laurel Vs Ramon GarciaDocument2 pagesSalvador Laurel Vs Ramon GarciahowieboiNo ratings yet

- 6.1 Laurel Vs GarciaDocument8 pages6.1 Laurel Vs GarciaGhifari MustaphaNo ratings yet

- 64 Laurel vs. GarciaDocument3 pages64 Laurel vs. GarciaCarlo FernandezNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. GarciaDocument2 pagesLaurel vs. GarciaCharry Castillon100% (1)

- Laurel V GarciaDocument1 pageLaurel V GarciaMariano RentomesNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, 187 SCRA 797, G.R. No. 92013, G.R. No. 92047 July 25, 1990Document2 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, 187 SCRA 797, G.R. No. 92013, G.R. No. 92047 July 25, 1990yangkee_17No ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel v. GarciaCheryl OlivarezNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. Garcia (G.R. No. 92013)Document16 pagesLaurel v. Garcia (G.R. No. 92013)Angela AquinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Property in Relation To The Person To Whom It BelongsDocument5 pagesChapter 3: Property in Relation To The Person To Whom It BelongsLielet MatutinoNo ratings yet

- PROPERTY - Laurel v. GarciaDocument2 pagesPROPERTY - Laurel v. GarciaJenn DenostaNo ratings yet

- Laurel V GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel V GarciaTinNo ratings yet

- 19 Laurel v. GarciaDocument7 pages19 Laurel v. GarciaMaria Yolly RiveraNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument1 pageLaurel Vs GarciaMitz FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument2 pagesLaurel v. GarciaronaldNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Review 1 Finals ReviewerDocument10 pagesCivil Law Review 1 Finals ReviewerchikateeNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia 187 SCRA 797Document15 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia 187 SCRA 797Ryan CondeNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel v. GarciaMarielle MorilloNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, G.R No. 92013, 27 July 1990Document29 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, G.R No. 92013, 27 July 1990wintergyeolNo ratings yet

- 2GN 09-07-2021Document4 pages2GN 09-07-2021Owen DefuntaronNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument2 pagesCase Digestashley brownNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013 July 25, 1990Document31 pagesLaurel v. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013 July 25, 1990Ryuzaki HidekiNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document14 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Jhanelyn V. InopiaNo ratings yet

- Cagayan Fishing Dev. Co., Inc. v. Teodoro Sandiko, 65 Phil. 223 (1937)Document32 pagesCagayan Fishing Dev. Co., Inc. v. Teodoro Sandiko, 65 Phil. 223 (1937)bentley CobyNo ratings yet

- Assigned Cases - 01-24-2024Document18 pagesAssigned Cases - 01-24-2024Edcel June AmadoNo ratings yet

- (Conflict) Compilation of Case Digests - Batch 2Document20 pages(Conflict) Compilation of Case Digests - Batch 2Japoy Regodon EsquilloNo ratings yet

- Property Law Cases - Atty. SengaDocument140 pagesProperty Law Cases - Atty. SengaAgatha Faye CastillejoNo ratings yet

- Epublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document22 pagesEpublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013creusjoyanneNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013, July 25, 1990 - HI-LITEDocument28 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013, July 25, 1990 - HI-LITEEmil BautistaNo ratings yet

- REL LaurelvGarcia RepublicvCA ZamboangadelNortevCityofZamboanga ChavezvPEADocument72 pagesREL LaurelvGarcia RepublicvCA ZamboangadelNortevCityofZamboanga ChavezvPEAN4STYNo ratings yet

- Property Cases 1Document45 pagesProperty Cases 1Regina Rae LuzadasNo ratings yet

- Land Reg Laws Case DigestsDocument11 pagesLand Reg Laws Case DigestsPaul BasillaNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel v. GarciaNoel Cagigas FelongcoNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws Cases Set 1Document70 pagesConflict of Laws Cases Set 1Coreene CularNo ratings yet

- Property Case Digests 1Document8 pagesProperty Case Digests 1Eloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- City of Pasig Vs RepublicDocument5 pagesCity of Pasig Vs Republicjovani emaNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaKadzNituraNo ratings yet

- Laurel V Garcia DigestDocument2 pagesLaurel V Garcia DigestKDNo ratings yet

- Laurel V GarciaDocument8 pagesLaurel V GarciaRalph Deric EspirituNo ratings yet

- Title I - Chapter 3 - Property in Relation To Person Whom It BelongsDocument3 pagesTitle I - Chapter 3 - Property in Relation To Person Whom It BelongsiesumurzNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Law CasesDocument247 pagesConflict of Law CasesMaria Guilka SenarloNo ratings yet

- Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document12 pagesArturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Veah CaabayNo ratings yet

- 3.1 Laurel V GarciaDocument31 pages3.1 Laurel V GarciaYna SuguitanNo ratings yet

- FinalsDocument124 pagesFinalsmuton20No ratings yet

- Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document25 pagesArturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Junior DaveNo ratings yet

- Fishwealth Canning Corporation Vs CirDocument2 pagesFishwealth Canning Corporation Vs CirKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Medado Vs Heirs Case DigestDocument2 pagesMedado Vs Heirs Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Coa Vs Paler Case DigestDocument1 pageCoa Vs Paler Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosa100% (1)

- Science 6: Separating MixturesDocument32 pagesScience 6: Separating MixturesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Alma Jose Vs Javellano Case DigestDocument2 pagesAlma Jose Vs Javellano Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Manila Electric Company Vs CirDocument1 pageManila Electric Company Vs CirKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

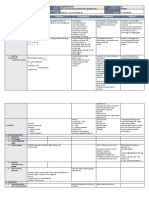

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument3 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue VsDocument2 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue VsKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument5 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Separation Methods: Ways To Separate Mixtures - Chapter 3: Matter & Its PropertiesDocument17 pagesSeparation Methods: Ways To Separate Mixtures - Chapter 3: Matter & Its PropertiesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Science 6 q1 Week 4 Day 1Document32 pagesScience 6 q1 Week 4 Day 1KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs RhombusDocument2 pagesCIR Vs RhombusKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Methods of AccountingDocument1 pageMethods of AccountingKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Scxso 2222Document1 pageScxso 2222KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Cont : Fees in Proportion To The Work Performed and Responsibility AssumedDocument1 pageCont : Fees in Proportion To The Work Performed and Responsibility AssumedKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Trust Receipt Agreements or Exercise The Courses of Action by Entruster As Provided For Under PD 115Document2 pagesTrust Receipt Agreements or Exercise The Courses of Action by Entruster As Provided For Under PD 115KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 6: Parties Who Are LiableDocument2 pagesCHAPTER 6: Parties Who Are LiableKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Srib 11111111111111Document99 pagesSrib 11111111111111KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- 3333333333333333333333Document90 pages3333333333333333333333KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs FABELADocument1 pageCIR Vs FABELAKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Legal FeesDocument1 pageLegal FeesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- 222222222222222222222Document94 pages222222222222222222222KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Scribd Chapter 4Document1 pageScribd Chapter 4KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Business Governance: Learning OutcomesDocument30 pagesModule 1: Business Governance: Learning OutcomesMicah Ruth PascuaNo ratings yet

- Aparna CVDocument2 pagesAparna CVvaibs26No ratings yet

- West of England Defence Guide Speed and ConsumptionDocument4 pagesWest of England Defence Guide Speed and Consumptionc rkNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Delegation and DecentralizationDocument4 pagesDifference Between Delegation and Decentralizationjatinder99No ratings yet

- OREVOYBILLDocument2 pagesOREVOYBILLGerik AlmarezNo ratings yet

- SampledocretentionpolicyDocument3 pagesSampledocretentionpolicyAbhijeet MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Epl Aif 2021 Final - 2022 03 24Document106 pagesEpl Aif 2021 Final - 2022 03 24Pierre CoffeeNo ratings yet

- Know Your Client and Anti-Money Laundering Questionnaire: Bank of Taiwan South Africa BranchDocument8 pagesKnow Your Client and Anti-Money Laundering Questionnaire: Bank of Taiwan South Africa BranchJagadeesh H JaganNo ratings yet

- Land Purchase and Sale Agreement Templates - LegalDocument4 pagesLand Purchase and Sale Agreement Templates - LegalAlekz PicarNo ratings yet

- Edfrx Bas s1Document9 pagesEdfrx Bas s1Nicola Rumbidzai MhakaNo ratings yet

- Construction CSHP Application Form - DOLEDocument3 pagesConstruction CSHP Application Form - DOLEJUCONS ConstructionNo ratings yet

- PPP Philippine Competition CommissionDocument21 pagesPPP Philippine Competition Commissionkristin.luceroNo ratings yet

- Notice of Understanding and Intent and Claim of RightDocument4 pagesNotice of Understanding and Intent and Claim of RightAmbassador: Basadar: Qadar-Shar™, D.D. (h.c.) aka Kevin Carlton George™100% (8)

- Presidential Decree No. 100Document16 pagesPresidential Decree No. 100ZC Fd KSNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering ActDocument4 pagesMoney Laundering ActpadminiNo ratings yet

- Project Report ON " in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For The Award of The Degree of (PGDM)Document7 pagesProject Report ON " in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For The Award of The Degree of (PGDM)Rishu PandeyNo ratings yet

- Public Mergers and Acquisitions in Malaysia - Overview - Practical LawDocument17 pagesPublic Mergers and Acquisitions in Malaysia - Overview - Practical LawAbigailNo ratings yet

- PMPDocument4 pagesPMPteccNo ratings yet

- Savings Accounts TNCDocument2 pagesSavings Accounts TNCrohan1234567No ratings yet

- Specify The Types of Country Risks That Pharmaceutical Firms Face in International BusinessDocument4 pagesSpecify The Types of Country Risks That Pharmaceutical Firms Face in International BusinessFidan DemirNo ratings yet

- Sawit Sumber Mas Sarana 150907 CRR ReportDocument38 pagesSawit Sumber Mas Sarana 150907 CRR ReportKai SanNo ratings yet

- MSFM Vendor Form - FillableDocument2 pagesMSFM Vendor Form - FillablelouispayneNo ratings yet

- City of Kalamazoo Medical Marijuana OrdinancesDocument10 pagesCity of Kalamazoo Medical Marijuana OrdinancesMalachi BarrettNo ratings yet

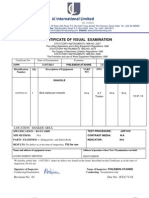

- International Limited: Certificate of Visual ExaminationDocument36 pagesInternational Limited: Certificate of Visual Examinationanon_656326693No ratings yet

- SP ProjectDocument14 pagesSP ProjectVyankatesh KarnewarNo ratings yet

- 106.national Exchange Co. vs. DexterDocument4 pages106.national Exchange Co. vs. Dextervince005No ratings yet

- PICPA Building, 700 Shaw BLVD., Mandaluyong CityDocument2 pagesPICPA Building, 700 Shaw BLVD., Mandaluyong CityPedro MarcoNo ratings yet

Scrisdsf

Scrisdsf

Uploaded by

KateBarrionEspinosaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Scrisdsf

Scrisdsf

Uploaded by

KateBarrionEspinosaCopyright:

Available Formats

The petitioners and respondents in both cases do not dispute the fact that the Roppongi site and

the three related properties were through

reparations agreements, that these were assigned to the government sector and that the Roppongi property itself was specifically designated under

the Reparations Agreement to house the Philippine Embassy.

The nature of the Roppongi lot as property for public service is expressly spelled out. It is dictated by the terms of the Reparations Agreement and

the corresponding contract of procurement which bind both the Philippine government and the Japanese government.

There can be no doubt that it is of public dominion unless it is convincingly shown that the property has become patrimonial. This, the

respondents have failed to do.

As property of public dominion, the Roppongi lot is outside the commerce of man. It cannot be alienated. Its ownership is a special collective

ownership for general use and enjoyment, an application to the satisfaction of collective needs, and resides in the social group. The purpose is not

to serve the State as a juridical person, but the citizens; it is intended for the common and public welfare and cannot be the object of appropration.

(Taken from 3 Manresa, 66-69; cited in Tolentino, Commentaries on the Civil Code of the Philippines, 1963 Edition, Vol. II, p. 26).

The applicable provisions of the Civil Code are:

ART. 419. Property is either of public dominion or of private ownership.

ART. 420. The following things are property of public dominion

(1) Those intended for public use, such as roads, canals, rivers, torrents, ports and bridges constructed by the

State, banks shores roadsteads, and others of similar character;

(2) Those which belong to the State, without being for public use, and are intended for some public service or

for the development of the national wealth.

ART. 421. All other property of the State, which is not of the character stated in the preceding article, is

patrimonial property.

The Roppongi property is correctly classified under paragraph 2 of Article 420 of the Civil Code as property belonging to the State and intended

for some public service.

Has the intention of the government regarding the use of the property been changed because the lot has been Idle for some years? Has it become

patrimonial?

The fact that the Roppongi site has not been used for a long time for actual Embassy service does not automatically convert it to patrimonial

property. Any such conversion happens only if the property is withdrawn from public use (Cebu Oxygen and Acetylene Co. v. Bercilles, 66

SCRA 481 [1975]). A property continues to be part of the public domain, not available for private appropriation or ownership until there is a

formal declaration on the part of the government to withdraw it from being such (Ignacio v. Director of Lands, 108 Phil. 335 [1960]).

The respondents enumerate various pronouncements by concerned public officials insinuating a change of intention. We emphasize, however, that

an abandonment of the intention to use the Roppongi property for public service and to make it patrimonial property under Article 422 of the

Civil Code must be definite Abandonment cannot be inferred from the non-use alone specially if the non-use was attributable not to the

government's own deliberate and indubitable will but to a lack of financial support to repair and improve the property (See Heirs of Felino

Santiago v. Lazaro, 166 SCRA 368 [1988]). Abandonment must be a certain and positive act based on correct legal premises.

A mere transfer of the Philippine Embassy to Nampeidai in 1976 is not relinquishment of the Roppongi property's original purpose. Even the

failure by the government to repair the building in Roppongi is not abandonment since as earlier stated, there simply was a shortage of

government funds. The recent Administrative Orders authorizing a study of the status and conditions of government properties in Japan were

merely directives for investigation but did not in any way signify a clear intention to dispose of the properties.

Executive Order No. 296, though its title declares an "authority to sell", does not have a provision in its text expressly authorizing the sale of the

four properties procured from Japan for the government sector. The executive order does not declare that the properties lost their public character.

It merely intends to make the properties available to foreigners and not to Filipinos alone in case of a sale, lease or other disposition. It merely

eliminates the restriction

You might also like

- Laurel v. Garcia DigestDocument2 pagesLaurel v. Garcia DigestAbi Bernardino100% (11)

- Laurel v. Garcia, GR No. 92013, 92047Document2 pagesLaurel v. Garcia, GR No. 92013, 92047Amicah100% (3)

- Property - Laurel v. GarciaDocument4 pagesProperty - Laurel v. GarciaPepper PottsNo ratings yet

- CASE DIGEST Laurel Vs GarciaDocument2 pagesCASE DIGEST Laurel Vs GarciaErica Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- How to Transfer Real Property Ownership in the PhilippinesFrom EverandHow to Transfer Real Property Ownership in the PhilippinesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Application Data SheetDocument4 pagesApplication Data SheetThedford I. HItafferNo ratings yet

- Telenor's Agreement On Responsible Business ConductDocument10 pagesTelenor's Agreement On Responsible Business ConductThan Htaik AungNo ratings yet

- Abacus Securities Corporation v. Ruben AmpilDocument2 pagesAbacus Securities Corporation v. Ruben AmpilRafael100% (1)

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaBeatrice AbanNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument5 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaDolores PulisNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs Garcia and DENR Vs YAPDocument12 pagesLaurel Vs Garcia and DENR Vs YAPMariko IwakiNo ratings yet

- Facts: The Subject Roppongi Property Is One of The Four Properties in Japan Acquired by The Philippine Government Under TheDocument62 pagesFacts: The Subject Roppongi Property Is One of The Four Properties in Japan Acquired by The Philippine Government Under TheMarianne FelixNo ratings yet

- Chapter VDocument20 pagesChapter VRessie June PedranoNo ratings yet

- 09 - Laurel v. Garcia - LiaoDocument2 pages09 - Laurel v. Garcia - LiaoRalph Deric EspirituNo ratings yet

- Public v. Private PropertyDocument3 pagesPublic v. Private PropertyMarvin TuasonNo ratings yet

- Torts and CrimesDocument14 pagesTorts and CrimesCheer SNo ratings yet

- Law On Property: Case Reporting By: Espinosa, Von Leslie LDocument10 pagesLaw On Property: Case Reporting By: Espinosa, Von Leslie LLeslie EspinosaNo ratings yet

- Salvador Laurel Vs Ramon GarciaDocument2 pagesSalvador Laurel Vs Ramon GarciahowieboiNo ratings yet

- 6.1 Laurel Vs GarciaDocument8 pages6.1 Laurel Vs GarciaGhifari MustaphaNo ratings yet

- 64 Laurel vs. GarciaDocument3 pages64 Laurel vs. GarciaCarlo FernandezNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. GarciaDocument2 pagesLaurel vs. GarciaCharry Castillon100% (1)

- Laurel V GarciaDocument1 pageLaurel V GarciaMariano RentomesNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, 187 SCRA 797, G.R. No. 92013, G.R. No. 92047 July 25, 1990Document2 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, 187 SCRA 797, G.R. No. 92013, G.R. No. 92047 July 25, 1990yangkee_17No ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel v. GarciaCheryl OlivarezNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. Garcia (G.R. No. 92013)Document16 pagesLaurel v. Garcia (G.R. No. 92013)Angela AquinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3: Property in Relation To The Person To Whom It BelongsDocument5 pagesChapter 3: Property in Relation To The Person To Whom It BelongsLielet MatutinoNo ratings yet

- PROPERTY - Laurel v. GarciaDocument2 pagesPROPERTY - Laurel v. GarciaJenn DenostaNo ratings yet

- Laurel V GarciaDocument3 pagesLaurel V GarciaTinNo ratings yet

- 19 Laurel v. GarciaDocument7 pages19 Laurel v. GarciaMaria Yolly RiveraNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument1 pageLaurel Vs GarciaMitz FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument2 pagesLaurel v. GarciaronaldNo ratings yet

- Civil Law Review 1 Finals ReviewerDocument10 pagesCivil Law Review 1 Finals ReviewerchikateeNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia 187 SCRA 797Document15 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia 187 SCRA 797Ryan CondeNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel v. GarciaMarielle MorilloNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, G.R No. 92013, 27 July 1990Document29 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, G.R No. 92013, 27 July 1990wintergyeolNo ratings yet

- 2GN 09-07-2021Document4 pages2GN 09-07-2021Owen DefuntaronNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument2 pagesCase Digestashley brownNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013 July 25, 1990Document31 pagesLaurel v. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013 July 25, 1990Ryuzaki HidekiNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document14 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Jhanelyn V. InopiaNo ratings yet

- Cagayan Fishing Dev. Co., Inc. v. Teodoro Sandiko, 65 Phil. 223 (1937)Document32 pagesCagayan Fishing Dev. Co., Inc. v. Teodoro Sandiko, 65 Phil. 223 (1937)bentley CobyNo ratings yet

- Assigned Cases - 01-24-2024Document18 pagesAssigned Cases - 01-24-2024Edcel June AmadoNo ratings yet

- (Conflict) Compilation of Case Digests - Batch 2Document20 pages(Conflict) Compilation of Case Digests - Batch 2Japoy Regodon EsquilloNo ratings yet

- Property Law Cases - Atty. SengaDocument140 pagesProperty Law Cases - Atty. SengaAgatha Faye CastillejoNo ratings yet

- Epublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document22 pagesEpublic of The Philippines Manila en Banc: Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013creusjoyanneNo ratings yet

- Laurel vs. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013, July 25, 1990 - HI-LITEDocument28 pagesLaurel vs. Garcia, G.R. No. 92013, July 25, 1990 - HI-LITEEmil BautistaNo ratings yet

- REL LaurelvGarcia RepublicvCA ZamboangadelNortevCityofZamboanga ChavezvPEADocument72 pagesREL LaurelvGarcia RepublicvCA ZamboangadelNortevCityofZamboanga ChavezvPEAN4STYNo ratings yet

- Property Cases 1Document45 pagesProperty Cases 1Regina Rae LuzadasNo ratings yet

- Land Reg Laws Case DigestsDocument11 pagesLand Reg Laws Case DigestsPaul BasillaNo ratings yet

- Laurel v. GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel v. GarciaNoel Cagigas FelongcoNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws Cases Set 1Document70 pagesConflict of Laws Cases Set 1Coreene CularNo ratings yet

- Property Case Digests 1Document8 pagesProperty Case Digests 1Eloisa Katrina MadambaNo ratings yet

- City of Pasig Vs RepublicDocument5 pagesCity of Pasig Vs Republicjovani emaNo ratings yet

- Laurel Vs GarciaDocument24 pagesLaurel Vs GarciaKadzNituraNo ratings yet

- Laurel V Garcia DigestDocument2 pagesLaurel V Garcia DigestKDNo ratings yet

- Laurel V GarciaDocument8 pagesLaurel V GarciaRalph Deric EspirituNo ratings yet

- Title I - Chapter 3 - Property in Relation To Person Whom It BelongsDocument3 pagesTitle I - Chapter 3 - Property in Relation To Person Whom It BelongsiesumurzNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Law CasesDocument247 pagesConflict of Law CasesMaria Guilka SenarloNo ratings yet

- Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document12 pagesArturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Veah CaabayNo ratings yet

- 3.1 Laurel V GarciaDocument31 pages3.1 Laurel V GarciaYna SuguitanNo ratings yet

- FinalsDocument124 pagesFinalsmuton20No ratings yet

- Arturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Document25 pagesArturo M. Tolentino For Petitioner in 92013Junior DaveNo ratings yet

- Fishwealth Canning Corporation Vs CirDocument2 pagesFishwealth Canning Corporation Vs CirKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Medado Vs Heirs Case DigestDocument2 pagesMedado Vs Heirs Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Coa Vs Paler Case DigestDocument1 pageCoa Vs Paler Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosa100% (1)

- Science 6: Separating MixturesDocument32 pagesScience 6: Separating MixturesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Alma Jose Vs Javellano Case DigestDocument2 pagesAlma Jose Vs Javellano Case DigestKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Manila Electric Company Vs CirDocument1 pageManila Electric Company Vs CirKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument3 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Commissioner of Internal Revenue VsDocument2 pagesCommissioner of Internal Revenue VsKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument5 pagesMonday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday: GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Separation Methods: Ways To Separate Mixtures - Chapter 3: Matter & Its PropertiesDocument17 pagesSeparation Methods: Ways To Separate Mixtures - Chapter 3: Matter & Its PropertiesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Science 6 q1 Week 4 Day 1Document32 pagesScience 6 q1 Week 4 Day 1KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs RhombusDocument2 pagesCIR Vs RhombusKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Methods of AccountingDocument1 pageMethods of AccountingKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Scxso 2222Document1 pageScxso 2222KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Cont : Fees in Proportion To The Work Performed and Responsibility AssumedDocument1 pageCont : Fees in Proportion To The Work Performed and Responsibility AssumedKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Trust Receipt Agreements or Exercise The Courses of Action by Entruster As Provided For Under PD 115Document2 pagesTrust Receipt Agreements or Exercise The Courses of Action by Entruster As Provided For Under PD 115KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 6: Parties Who Are LiableDocument2 pagesCHAPTER 6: Parties Who Are LiableKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Srib 11111111111111Document99 pagesSrib 11111111111111KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- 3333333333333333333333Document90 pages3333333333333333333333KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- CIR Vs FABELADocument1 pageCIR Vs FABELAKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Legal FeesDocument1 pageLegal FeesKateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- 222222222222222222222Document94 pages222222222222222222222KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Scribd Chapter 4Document1 pageScribd Chapter 4KateBarrionEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Module 1: Business Governance: Learning OutcomesDocument30 pagesModule 1: Business Governance: Learning OutcomesMicah Ruth PascuaNo ratings yet

- Aparna CVDocument2 pagesAparna CVvaibs26No ratings yet

- West of England Defence Guide Speed and ConsumptionDocument4 pagesWest of England Defence Guide Speed and Consumptionc rkNo ratings yet

- Difference Between Delegation and DecentralizationDocument4 pagesDifference Between Delegation and Decentralizationjatinder99No ratings yet

- OREVOYBILLDocument2 pagesOREVOYBILLGerik AlmarezNo ratings yet

- SampledocretentionpolicyDocument3 pagesSampledocretentionpolicyAbhijeet MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Epl Aif 2021 Final - 2022 03 24Document106 pagesEpl Aif 2021 Final - 2022 03 24Pierre CoffeeNo ratings yet

- Know Your Client and Anti-Money Laundering Questionnaire: Bank of Taiwan South Africa BranchDocument8 pagesKnow Your Client and Anti-Money Laundering Questionnaire: Bank of Taiwan South Africa BranchJagadeesh H JaganNo ratings yet

- Land Purchase and Sale Agreement Templates - LegalDocument4 pagesLand Purchase and Sale Agreement Templates - LegalAlekz PicarNo ratings yet

- Edfrx Bas s1Document9 pagesEdfrx Bas s1Nicola Rumbidzai MhakaNo ratings yet

- Construction CSHP Application Form - DOLEDocument3 pagesConstruction CSHP Application Form - DOLEJUCONS ConstructionNo ratings yet

- PPP Philippine Competition CommissionDocument21 pagesPPP Philippine Competition Commissionkristin.luceroNo ratings yet

- Notice of Understanding and Intent and Claim of RightDocument4 pagesNotice of Understanding and Intent and Claim of RightAmbassador: Basadar: Qadar-Shar™, D.D. (h.c.) aka Kevin Carlton George™100% (8)

- Presidential Decree No. 100Document16 pagesPresidential Decree No. 100ZC Fd KSNo ratings yet

- Money Laundering ActDocument4 pagesMoney Laundering ActpadminiNo ratings yet

- Project Report ON " in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For The Award of The Degree of (PGDM)Document7 pagesProject Report ON " in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirement For The Award of The Degree of (PGDM)Rishu PandeyNo ratings yet

- Public Mergers and Acquisitions in Malaysia - Overview - Practical LawDocument17 pagesPublic Mergers and Acquisitions in Malaysia - Overview - Practical LawAbigailNo ratings yet

- PMPDocument4 pagesPMPteccNo ratings yet

- Savings Accounts TNCDocument2 pagesSavings Accounts TNCrohan1234567No ratings yet

- Specify The Types of Country Risks That Pharmaceutical Firms Face in International BusinessDocument4 pagesSpecify The Types of Country Risks That Pharmaceutical Firms Face in International BusinessFidan DemirNo ratings yet

- Sawit Sumber Mas Sarana 150907 CRR ReportDocument38 pagesSawit Sumber Mas Sarana 150907 CRR ReportKai SanNo ratings yet

- MSFM Vendor Form - FillableDocument2 pagesMSFM Vendor Form - FillablelouispayneNo ratings yet

- City of Kalamazoo Medical Marijuana OrdinancesDocument10 pagesCity of Kalamazoo Medical Marijuana OrdinancesMalachi BarrettNo ratings yet

- International Limited: Certificate of Visual ExaminationDocument36 pagesInternational Limited: Certificate of Visual Examinationanon_656326693No ratings yet

- SP ProjectDocument14 pagesSP ProjectVyankatesh KarnewarNo ratings yet

- 106.national Exchange Co. vs. DexterDocument4 pages106.national Exchange Co. vs. Dextervince005No ratings yet

- PICPA Building, 700 Shaw BLVD., Mandaluyong CityDocument2 pagesPICPA Building, 700 Shaw BLVD., Mandaluyong CityPedro MarcoNo ratings yet