Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2566 Heart Failure

2566 Heart Failure

Uploaded by

noronisa talusobCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- FST MCQS 1 With Answers KeyDocument61 pagesFST MCQS 1 With Answers KeyAleem Muhammad88% (16)

- Nursing Patient InteractionDocument7 pagesNursing Patient Interactionnoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Bahasa Inggeris Kertas 1Document13 pagesBahasa Inggeris Kertas 1Sheda Rum100% (5)

- Pediatrics in Review. Dehydration 2015Document14 pagesPediatrics in Review. Dehydration 2015Jorge Eduardo Espinoza Rios100% (2)

- Muslim Female Students and Their Experiences of Higher Education in CanadaDocument231 pagesMuslim Female Students and Their Experiences of Higher Education in Canadanoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Noronisa Talusob Bsn-3: What Is Hinduism?Document4 pagesNoronisa Talusob Bsn-3: What Is Hinduism?noronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Impact of Stress Management On Learning in A Classroom Setting PDFDocument58 pagesImpact of Stress Management On Learning in A Classroom Setting PDFnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- R. Ryles: The Impact of Braille Reading Skills On Employment, Income, Education, and Reading HabitsDocument9 pagesR. Ryles: The Impact of Braille Reading Skills On Employment, Income, Education, and Reading Habitsnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Communication As Basic Tool in Learning: Norhaina K. Galindo BSEXEDDocument8 pagesCommunication As Basic Tool in Learning: Norhaina K. Galindo BSEXEDnoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Transfer of Learning and MotivationDocument12 pagesTransfer of Learning and Motivationnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- DialogueDocument18 pagesDialoguenoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- NPI 3rd YrDocument3 pagesNPI 3rd Yrshin_2173No ratings yet

- Examples of Dialogue in LiteratureDocument4 pagesExamples of Dialogue in Literaturenoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Asignment Update Population of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesAsignment Update Population of The Philippinesnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Labio, Roan Claire BSN-4: Staffing ScheduleDocument2 pagesLabio, Roan Claire BSN-4: Staffing Schedulenoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- The Role of The TeacherDocument6 pagesThe Role of The Teachernoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Seminar Evaluation: 4 Strongly Agree 3 Agree 2 Disagree 1 Strongly Disagree 0 No OpinionDocument1 pageSeminar Evaluation: 4 Strongly Agree 3 Agree 2 Disagree 1 Strongly Disagree 0 No Opinionnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Background of The ProblemDocument45 pagesBackground of The Problemnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Annex 8 Ec Conference EvaluationDocument3 pagesAnnex 8 Ec Conference Evaluationnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Extreme Icu: 5 Percent of Patients Account For 33 Percent of Intensive Care, Need Special FocusDocument8 pagesExtreme Icu: 5 Percent of Patients Account For 33 Percent of Intensive Care, Need Special Focusnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- 3h. Toliet Facility: Water Seled Latrine Pit Privy NoneDocument7 pages3h. Toliet Facility: Water Seled Latrine Pit Privy Nonenoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Work-Shop Evaluation: (Post-Test)Document2 pagesWork-Shop Evaluation: (Post-Test)noronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- 09 ASA SK Vit MineralsDocument25 pages09 ASA SK Vit MineralsmarofNo ratings yet

- Micronutrienti, Macronutrienti - Alune, Linte, Naut, PuiDocument4 pagesMicronutrienti, Macronutrienti - Alune, Linte, Naut, PuiAnda_Titieni_5017No ratings yet

- Medial Collateral Ligament Injury MCL Rehabilitation Yale 240271 28716Document8 pagesMedial Collateral Ligament Injury MCL Rehabilitation Yale 240271 28716Raluca Alexandra PlescaNo ratings yet

- Adani Wilmar LTDDocument55 pagesAdani Wilmar LTDAmit ChotaiNo ratings yet

- 1 - Dysphagia and StrokeDocument39 pages1 - Dysphagia and StrokeVeggy Septian Ellitha100% (1)

- Weight Loss StrategiesDocument28 pagesWeight Loss StrategiesCatherine FadriquelanNo ratings yet

- Drug Study For GDMDocument7 pagesDrug Study For GDMFuture RNNo ratings yet

- Stomach CancerDocument11 pagesStomach CancerJumar Vallo ValdezNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Ginger PowderDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Ginger PowdermplennaNo ratings yet

- Balance KH 5509Document20 pagesBalance KH 5509Manolis MichelakisNo ratings yet

- Supplements That Doctors Themselve TakeDocument7 pagesSupplements That Doctors Themselve TakeJen Cooper100% (1)

- Drink Your Milk - The Many Benefits of Dairy - Ray Peat ForumDocument13 pagesDrink Your Milk - The Many Benefits of Dairy - Ray Peat ForumDarci HallNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For AYUSH-NET For Ph.D.fellowships SRFDocument24 pagesSyllabus For AYUSH-NET For Ph.D.fellowships SRFHarish KiranNo ratings yet

- Microgreens: Guide ToDocument21 pagesMicrogreens: Guide ToVinod100% (3)

- Controlled GI Transit in Enteral NutritionDocument36 pagesControlled GI Transit in Enteral NutritionSiti Ika FitrasyahNo ratings yet

- Ephmra - Atcguidelines2018finalDocument154 pagesEphmra - Atcguidelines2018finalClose UpNo ratings yet

- 6BI01 01 Que 20160526Document39 pages6BI01 01 Que 20160526sg noteNo ratings yet

- David PerlmutterDocument25 pagesDavid PerlmutteralicedwyerNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument4 pagesEnglishTodirenche LarisaNo ratings yet

- TKR ProtocolDocument8 pagesTKR ProtocolSandeep SoniNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Current Food Consumption Amongst The Spanish ANIBES Study PopulationDocument15 pagesNutrients: Current Food Consumption Amongst The Spanish ANIBES Study PopulationAntony LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Sample - Review of Related LiteratureDocument5 pagesSample - Review of Related LiteratureJohn Williams89% (9)

- A Project Report On Cadbury 75 PagesDocument76 pagesA Project Report On Cadbury 75 PagesRenju Romals0% (1)

- FHP & NCP - FractureDocument14 pagesFHP & NCP - FractureFrancis AdrianNo ratings yet

- Final Case StudyDocument4 pagesFinal Case Studyapi-207971474No ratings yet

- In Season Training Program BacksDocument35 pagesIn Season Training Program BacksjeanNo ratings yet

- 1000 MCQs Food NutritionDocument153 pages1000 MCQs Food NutritionSaba ChaudhryNo ratings yet

2566 Heart Failure

2566 Heart Failure

Uploaded by

noronisa talusobCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2566 Heart Failure

2566 Heart Failure

Uploaded by

noronisa talusobCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 1 of 3

View this article online at: patient.info/doctor/palliative-care-of-heart-failure

Palliative Care of Heart Failure

The management of chronic heart failure (CHF) has improved considerably in recent years but there still remains

a significant number of people who will die from this chronic disease. Many of those could benefit from palliative

care.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) has identified the need for palliative care. [1] Around

40% will die within a year of diagnosis and the quality of life may well be poorer than with other illnesses. There is

a heavy burden of symptoms, a lack of communication and many psychological and social needs that are not

being met. Much of what has been learned from cancer care is not being applied to the care of end-stage heart

failure.

Place of care

The most appropriate place of care does not depend on the aetiology of the terminal condition. Most people would

prefer dying at home if there is sufficient support. The hospice movement has made a great impact and deals

with all forms of terminal care. Specially trained nurses can improve the management of patients with heart

failure in hospital and there is also outreach to the community. [2] Nurse-led community management can provide

support with:

Regular follow-up and assessment, including blood chemistry, to detect early clinical deterioration.

Continued adjustment and optimisation of therapy according to agreed protocols.

Promotion and support of self-management, including daily monitoring of weight.

Education: covering both pharmacological and non-pharmacological aspects of care, including

exercise and nutrition advice.

Acting as an intermediary between the patient and other professionals - eg, cardiologists and the

primary healthcare team.

Provision of support for patients and their carers.

Patient needs [3]

CHF produces a wide range of symptoms.

Fatigue and breathlessness (see below) are the most common limiting and distressing complaints:

The position of the patient (supine/prone) should be considered.

Oxygen may well be helpful.

If dyspnoea remains a problem then morphine is often effective. It does not cause undue

suppression of the respiratory drive but it does help to relieve distress and can have a

pharmacological action to improve left ventricular failure.

Depression may occur in about a third of patients and is often overlooked:

It should be sought and treated if found.

Tricyclic antidepressants are best avoided in heart failure.

Pain is very common, especially in the terminal stages:

One common cause is stretching of the capsule of the liver.

It should be managed in the usual way for palliative care except that non-steroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs should be avoided.

Morphine or diamorphine may be of value for both pain and dyspnoea.

Page 2 of 3

Nausea and decreased appetite are common problems and may result in such low nutritional intake

that health is impaired:

Factors include decreased hunger sensations, diet restrictions, fatigue, shortness of

breath, nausea, anxiety and sadness.

In the elderly, early satiety, decreased taste and smell, and eating alone also contribute. [4]

Management [3, 5]

Communication

CHF patients are still being ignored despite all that has been learned from communicating with cancer patients.

Talk to the patient. Spend some unhurried time. Find out what they know. Breaking bad news is not

easy but it must be done.

Patients want to learn about their prognosis at a time when they have optimum cerebral function. They

want an honest discussion about treatment options and prognosis but do not want to be left bereft of

hope. [6]

Poor cerebral blood flow is likely to lead to confusion and memory problems. Therefore, it may be

necessary to repeat information that has already been given.

Poor imparting of information and disease-specific barriers to effective communication, such as short-

term memory loss, confusion and fatigue, should be addressed.

Drug management

Make sure that maximum tolerated doses of drugs are used to control the heart failure. Dyspnoea can be

extremely distressing and a much-feared way to die. See the separate Dyspnoea in Palliative Care article which

covers many aspects of care, including coping with the patient who is panicking and distressed.

Nutrition

Maintaining adequate nutrition is important and difficult. Small, frequent, easily digested and appetising meals are

required.

Prognosis

Despite advances in therapy, the life expectancy for patients with CHF is worse than for any of the

common cancers and is associated with a comparable number of expected life-years lost.

In Scotland, as in many other countries, despite progressive heart failure therapeutic strategies, the

prognosis has remained poor compared to many cancers. After first hospitalisation with heart failure

50% of men and women have died by 2.3 years and 1.7 years respectively. [5]

In one American study, 54% of those who were expected to live for another six months died within

three days.

Various risk stratification methods, based on patient profiles and clinical features, are being developed

to make the assessment of life expectancy more accurate. [7]

Conclusion

Talking to the patients, managing pain, nausea and distress, and the many facets of good terminal care are not

receiving the attention they deserve.

The Department of Policy, Care and Rehabilitation at King's College Hospital, London has devised the following

recommendations: [8]

Sensitive provision of information and discussion of end-of-life issues with patients and families.

Mutual education of cardiology and palliative care staff.

Mutually agreed palliative care referral criteria and care pathways for patients with CHF.

Further reading & references

Acute and Chronic Heart Failure; European Society of Cardiology (2012)

Page 3 of 3

1. Chronic heart failure: Management of chronic heart failure in adults in primary and secondary care; NICE Clinical Guideline

(August 2010)

2. Takeda A, Taylor SJ, Taylor RS, et al; Clinical service organisation for heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Sep

12;9:CD002752. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002752.pub3.

3. Heart failure - chronic; NICE CKS, May 2015 (UK access only)

4. Lennie TA, Moser DK, Heo S, et al; Factors influencing food intake in patients with heart failure: a comparison with healthy

elders. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006 Mar-Apr;21(2):123-9.

5. Management of chronic heart failure; Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network - SIGN (2016)

6. Caldwell PH, Arthur HM, Demers C; Preferences of patients with heart failure for prognosis communication. Can J Cardiol.

2007 Aug;23(10):791-6.

7. Fonarow GC; Epidemiology and risk stratification in acute heart failure. Am Heart J. 2008 Feb;155(2):200-7. Epub 2007 Nov

26.

8. Selman L, Harding R, Beynon T, et al; Improving end-of-life care for patients with chronic heart failure: "Let's hope it'll get

better, when I know in my heart of hearts it won't". Heart. 2007 Aug;93(8):963-7. Epub 2007 Feb 19.

Disclaimer: This article is for information only and should not be used for the diagnosis or treatment of medical

conditions. EMIS has used all reasonable care in compiling the information but makes no warranty as to its

accuracy. Consult a doctor or other healthcare professional for diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions.

For details see our conditions.

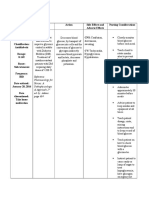

Original Author: Current Version: Peer Reviewer:

Dr Laurence Knott Dr Colin Tidy Dr John Cox

Document ID: Last Checked: Next Review:

2566 (v24) 24/03/2016 23/03/2021

View this article online at: patient.info/doctor/palliative-care-of-heart-failure

Discuss Palliative Care of Heart Failure and find more trusted resources at Patient.

Patient Platform Limited - All rights reserved.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5835)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (350)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- FST MCQS 1 With Answers KeyDocument61 pagesFST MCQS 1 With Answers KeyAleem Muhammad88% (16)

- Nursing Patient InteractionDocument7 pagesNursing Patient Interactionnoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Bahasa Inggeris Kertas 1Document13 pagesBahasa Inggeris Kertas 1Sheda Rum100% (5)

- Pediatrics in Review. Dehydration 2015Document14 pagesPediatrics in Review. Dehydration 2015Jorge Eduardo Espinoza Rios100% (2)

- Muslim Female Students and Their Experiences of Higher Education in CanadaDocument231 pagesMuslim Female Students and Their Experiences of Higher Education in Canadanoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Noronisa Talusob Bsn-3: What Is Hinduism?Document4 pagesNoronisa Talusob Bsn-3: What Is Hinduism?noronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Impact of Stress Management On Learning in A Classroom Setting PDFDocument58 pagesImpact of Stress Management On Learning in A Classroom Setting PDFnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- R. Ryles: The Impact of Braille Reading Skills On Employment, Income, Education, and Reading HabitsDocument9 pagesR. Ryles: The Impact of Braille Reading Skills On Employment, Income, Education, and Reading Habitsnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Communication As Basic Tool in Learning: Norhaina K. Galindo BSEXEDDocument8 pagesCommunication As Basic Tool in Learning: Norhaina K. Galindo BSEXEDnoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Transfer of Learning and MotivationDocument12 pagesTransfer of Learning and Motivationnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- DialogueDocument18 pagesDialoguenoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- NPI 3rd YrDocument3 pagesNPI 3rd Yrshin_2173No ratings yet

- Examples of Dialogue in LiteratureDocument4 pagesExamples of Dialogue in Literaturenoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Asignment Update Population of The PhilippinesDocument5 pagesAsignment Update Population of The Philippinesnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Labio, Roan Claire BSN-4: Staffing ScheduleDocument2 pagesLabio, Roan Claire BSN-4: Staffing Schedulenoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- The Role of The TeacherDocument6 pagesThe Role of The Teachernoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Seminar Evaluation: 4 Strongly Agree 3 Agree 2 Disagree 1 Strongly Disagree 0 No OpinionDocument1 pageSeminar Evaluation: 4 Strongly Agree 3 Agree 2 Disagree 1 Strongly Disagree 0 No Opinionnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Background of The ProblemDocument45 pagesBackground of The Problemnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Annex 8 Ec Conference EvaluationDocument3 pagesAnnex 8 Ec Conference Evaluationnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- Extreme Icu: 5 Percent of Patients Account For 33 Percent of Intensive Care, Need Special FocusDocument8 pagesExtreme Icu: 5 Percent of Patients Account For 33 Percent of Intensive Care, Need Special Focusnoronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- 3h. Toliet Facility: Water Seled Latrine Pit Privy NoneDocument7 pages3h. Toliet Facility: Water Seled Latrine Pit Privy Nonenoronisa talusob100% (1)

- Work-Shop Evaluation: (Post-Test)Document2 pagesWork-Shop Evaluation: (Post-Test)noronisa talusobNo ratings yet

- 09 ASA SK Vit MineralsDocument25 pages09 ASA SK Vit MineralsmarofNo ratings yet

- Micronutrienti, Macronutrienti - Alune, Linte, Naut, PuiDocument4 pagesMicronutrienti, Macronutrienti - Alune, Linte, Naut, PuiAnda_Titieni_5017No ratings yet

- Medial Collateral Ligament Injury MCL Rehabilitation Yale 240271 28716Document8 pagesMedial Collateral Ligament Injury MCL Rehabilitation Yale 240271 28716Raluca Alexandra PlescaNo ratings yet

- Adani Wilmar LTDDocument55 pagesAdani Wilmar LTDAmit ChotaiNo ratings yet

- 1 - Dysphagia and StrokeDocument39 pages1 - Dysphagia and StrokeVeggy Septian Ellitha100% (1)

- Weight Loss StrategiesDocument28 pagesWeight Loss StrategiesCatherine FadriquelanNo ratings yet

- Drug Study For GDMDocument7 pagesDrug Study For GDMFuture RNNo ratings yet

- Stomach CancerDocument11 pagesStomach CancerJumar Vallo ValdezNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Ginger PowderDocument8 pagesThe Effect of Ginger PowdermplennaNo ratings yet

- Balance KH 5509Document20 pagesBalance KH 5509Manolis MichelakisNo ratings yet

- Supplements That Doctors Themselve TakeDocument7 pagesSupplements That Doctors Themselve TakeJen Cooper100% (1)

- Drink Your Milk - The Many Benefits of Dairy - Ray Peat ForumDocument13 pagesDrink Your Milk - The Many Benefits of Dairy - Ray Peat ForumDarci HallNo ratings yet

- Syllabus For AYUSH-NET For Ph.D.fellowships SRFDocument24 pagesSyllabus For AYUSH-NET For Ph.D.fellowships SRFHarish KiranNo ratings yet

- Microgreens: Guide ToDocument21 pagesMicrogreens: Guide ToVinod100% (3)

- Controlled GI Transit in Enteral NutritionDocument36 pagesControlled GI Transit in Enteral NutritionSiti Ika FitrasyahNo ratings yet

- Ephmra - Atcguidelines2018finalDocument154 pagesEphmra - Atcguidelines2018finalClose UpNo ratings yet

- 6BI01 01 Que 20160526Document39 pages6BI01 01 Que 20160526sg noteNo ratings yet

- David PerlmutterDocument25 pagesDavid PerlmutteralicedwyerNo ratings yet

- EnglishDocument4 pagesEnglishTodirenche LarisaNo ratings yet

- TKR ProtocolDocument8 pagesTKR ProtocolSandeep SoniNo ratings yet

- Nutrients: Current Food Consumption Amongst The Spanish ANIBES Study PopulationDocument15 pagesNutrients: Current Food Consumption Amongst The Spanish ANIBES Study PopulationAntony LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Sample - Review of Related LiteratureDocument5 pagesSample - Review of Related LiteratureJohn Williams89% (9)

- A Project Report On Cadbury 75 PagesDocument76 pagesA Project Report On Cadbury 75 PagesRenju Romals0% (1)

- FHP & NCP - FractureDocument14 pagesFHP & NCP - FractureFrancis AdrianNo ratings yet

- Final Case StudyDocument4 pagesFinal Case Studyapi-207971474No ratings yet

- In Season Training Program BacksDocument35 pagesIn Season Training Program BacksjeanNo ratings yet

- 1000 MCQs Food NutritionDocument153 pages1000 MCQs Food NutritionSaba ChaudhryNo ratings yet