Professional Documents

Culture Documents

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

Uploaded by

hekiCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- CreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Document28 pagesCreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Burning Rose89% (140)

- 112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Document20 pages112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Paula GonzálezNo ratings yet

- YP CORE User ManualDocument36 pagesYP CORE User Manualloubwoy100% (4)

- BukowskiDocument5 pagesBukowskisalome davitulianiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingDocument94 pagesChapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingNaomi LiangNo ratings yet

- Mapa de Duelo ArtículoDocument19 pagesMapa de Duelo ArtículoCristian Steven Cabezas JoyaNo ratings yet

- Child Parent Psychotherapy - Alicia LiebermanDocument16 pagesChild Parent Psychotherapy - Alicia Liebermanapi-279694446No ratings yet

- CHRISTIAN LIVING EDUCATION 2 - Summative Test 2 - 3rd QuarterDocument5 pagesCHRISTIAN LIVING EDUCATION 2 - Summative Test 2 - 3rd Quarterjanet100% (1)

- EMI Therapy: clinical cases treated and commented step by step (English Edition)From EverandEMI Therapy: clinical cases treated and commented step by step (English Edition)No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Volume 1: Intellectual and Neuropsychological AssessmentFrom EverandComprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Volume 1: Intellectual and Neuropsychological AssessmentNo ratings yet

- Interoception and CompassionDocument4 pagesInteroception and CompassionMiguel A. RojasNo ratings yet

- Coherence Therapy (Previously, Depth-Oriented Brief Therapy)Document13 pagesCoherence Therapy (Previously, Depth-Oriented Brief Therapy)Paola AlarcónNo ratings yet

- 1968 - Kiresuk, T. Sherman, R.Document11 pages1968 - Kiresuk, T. Sherman, R.nataliacnNo ratings yet

- From Perception To Action: The Role of Auditory and Visual Information in Perceiving and Performing Complex MovementsDocument239 pagesFrom Perception To Action: The Role of Auditory and Visual Information in Perceiving and Performing Complex MovementsN SchaffertNo ratings yet

- A Proposal For An EMDR Reverse ProtocolDocument3 pagesA Proposal For An EMDR Reverse ProtocolLuiz Almeida100% (1)

- The Gender You Are and The Gender You Like - Sexual Preference and Empathic Neural ResponsesDocument10 pagesThe Gender You Are and The Gender You Like - Sexual Preference and Empathic Neural Responsesgabriela marmolejoNo ratings yet

- Interventions For Children With RADDocument6 pagesInterventions For Children With RADJohn BitsasNo ratings yet

- Bottom-Up and Top-Down Emotion GenerationDocument10 pagesBottom-Up and Top-Down Emotion GenerationTjerkDercksenNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenology of TraumaDocument4 pagesThe Phenomenology of TraumaMelayna Haley0% (1)

- Working With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewDocument5 pagesWorking With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewIngridSusuMoodNo ratings yet

- Emdr 2002Document14 pagesEmdr 2002jivinaNo ratings yet

- Self Reflective Essay For Foundations of Counselling Anc PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesSelf Reflective Essay For Foundations of Counselling Anc PsychotherapyRam MulingeNo ratings yet

- The Termination Phase: Therapists' Perspective On The Therapeutic Relationship and OutcomeDocument13 pagesThe Termination Phase: Therapists' Perspective On The Therapeutic Relationship and OutcomeFaten SalahNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFDocument20 pagesCognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFAhkam BloonNo ratings yet

- Radically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RODBT) : Who Is The Program For?Document1 pageRadically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RODBT) : Who Is The Program For?Ruslan IzmailovNo ratings yet

- The Racket System: A Model For Racket Analysis: Transactional Analysis Journal January 1979Document10 pagesThe Racket System: A Model For Racket Analysis: Transactional Analysis Journal January 1979marijanaaaaNo ratings yet

- Ansa Manual Sfy2017Document41 pagesAnsa Manual Sfy2017bhojaraja hNo ratings yet

- Loving Eyes ProtocolDocument1 pageLoving Eyes ProtocolMarta Casillas100% (1)

- Valeria Grishko Animal Guides in LifeDocument6 pagesValeria Grishko Animal Guides in LifeVerónicaMonyo100% (1)

- Tuguinay, Joshua FLA6 Later Views On Object Relations (Concept Map)Document1 pageTuguinay, Joshua FLA6 Later Views On Object Relations (Concept Map)Joshua TuguinayNo ratings yet

- DiagnosingDocument10 pagesDiagnosingAnonymous PIUFvLMuVONo ratings yet

- Pre TherapyDocument11 pagesPre TherapyВладимир ДудкинNo ratings yet

- Main 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentDocument25 pagesMain 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentKevin McInnes0% (1)

- Carl RogersDocument5 pagesCarl RogersHannah UyNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Children With Attachment Disorder - The Randolph PDFDocument161 pagesThe Assessment of Children With Attachment Disorder - The Randolph PDFAnonymous g3sy0uINo ratings yet

- Book Review An Action Plan For Your Inner Child Parenting Each OtherDocument3 pagesBook Review An Action Plan For Your Inner Child Parenting Each OtherNarcis NagyNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatrization of Difference: Frangoise Castel, Robert Caste1 and Anne LovellDocument13 pagesThe Psychiatrization of Difference: Frangoise Castel, Robert Caste1 and Anne Lovell123_scNo ratings yet

- Family System TheoryDocument23 pagesFamily System TheoryZaiden John RoquioNo ratings yet

- Gestalt Peeling The Onion Csi Presentatin March 12 2011Document6 pagesGestalt Peeling The Onion Csi Presentatin March 12 2011Adriana Bogdanovska ToskicNo ratings yet

- Expertise in Therapy Elusive Goal PDFDocument12 pagesExpertise in Therapy Elusive Goal PDFJonathon BenderNo ratings yet

- Approaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionDocument33 pagesApproaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionrusdaniaNo ratings yet

- Stern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreDocument17 pagesStern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Use of Flash Technique On A GroupDocument1 pageUse of Flash Technique On A GroupElisa ValdésNo ratings yet

- Running Header: ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT 1Document28 pagesRunning Header: ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT 1Coleen AndreaNo ratings yet

- Existential Phenomenological Psychotherapy - "Working With Internalizations" Part 2Document8 pagesExistential Phenomenological Psychotherapy - "Working With Internalizations" Part 2Rudy BauerNo ratings yet

- Standard Progressive MatricesDocument6 pagesStandard Progressive MatricesZoya SajidNo ratings yet

- Piperno, F., Biasi, S. & Levi, G. (2007) - Evaluation of Family Drawings of Physically and Sexually Abused ChildrenDocument10 pagesPiperno, F., Biasi, S. & Levi, G. (2007) - Evaluation of Family Drawings of Physically and Sexually Abused ChildrenRicardo NarváezNo ratings yet

- MBT I ManualDocument42 pagesMBT I ManualMauroNo ratings yet

- 09 - Kohut & Wolf - 1978 - The Disorders of The Self and Their TreatmentDocument13 pages09 - Kohut & Wolf - 1978 - The Disorders of The Self and Their TreatmentRebeca UrbonNo ratings yet

- The Wounded Healer As Cultural ArchetypeDocument10 pagesThe Wounded Healer As Cultural ArchetypeScotNo ratings yet

- Bosmans, 2010 - Attachment and Early Maladaptive SchemasDocument26 pagesBosmans, 2010 - Attachment and Early Maladaptive SchemasElaspiriNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Play Therapy On Reduction ofDocument6 pagesThe Effectiveness of Play Therapy On Reduction ofHira Khan100% (1)

- The Empty ChairDocument1 pageThe Empty Chairapi-244827434No ratings yet

- Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Core Concepts and Clinical Practice by Kristie Brandt Bruce D. Perry Stephen Seligman Ed TronickDocument382 pagesInfant and Early Childhood Mental Health Core Concepts and Clinical Practice by Kristie Brandt Bruce D. Perry Stephen Seligman Ed TronickRucsandra Murzea100% (1)

- Psychodynamic Diagnostic ManualDocument6 pagesPsychodynamic Diagnostic Manualas9as9as9as9No ratings yet

- Gabbard Suport TerapiDocument25 pagesGabbard Suport TerapiAgit Z100% (1)

- Transcript of Therapy Session by Douglas BowerDocument12 pagesTranscript of Therapy Session by Douglas Bowerjonny anlizaNo ratings yet

- The Satir Model: Yesterday and Today: John BanmenDocument16 pagesThe Satir Model: Yesterday and Today: John BanmenLaura LinaresNo ratings yet

- Nancy McWilliams - Beyond Traits - Personality As Intersubjective ThemesDocument30 pagesNancy McWilliams - Beyond Traits - Personality As Intersubjective Themesmeditationinstitute.netNo ratings yet

- Therapist As A Container For Spiritual ExperienceDocument27 pagesTherapist As A Container For Spiritual ExperienceEduardo Martín Sánchez Montoya100% (1)

- OH Cards and Their Counterparts (Atkinson K., Wells C.) (Z-Library)Document11 pagesOH Cards and Their Counterparts (Atkinson K., Wells C.) (Z-Library)Merce VisanoNo ratings yet

- MCMI IV Interpretation Webinar Handout 072116Document21 pagesMCMI IV Interpretation Webinar Handout 072116HUDA NAAZNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Rainfall Intensity For Southern Nigeria: S.O. Oyegoke, A. S. Adebanjo, E.O. Ajani, and J.T. JegedeDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Rainfall Intensity For Southern Nigeria: S.O. Oyegoke, A. S. Adebanjo, E.O. Ajani, and J.T. JegedeAdebanjo Adeshina SamuelNo ratings yet

- X32 Digital Mixer: User ManualDocument69 pagesX32 Digital Mixer: User ManualLuis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Cambodia of The Land Management and Administration Project (LMAP)Document19 pagesCambodia of The Land Management and Administration Project (LMAP)SaravornNo ratings yet

- Procesul de ReticulareDocument20 pagesProcesul de ReticulareMadalina CalcanNo ratings yet

- Prophet Hope Khoza - See in The SpiritDocument36 pagesProphet Hope Khoza - See in The SpiritMiguel SierraNo ratings yet

- Prelim Notes AccountingDocument63 pagesPrelim Notes AccountingKristine Camille GodinezNo ratings yet

- EstimationDocument106 pagesEstimationasdasdas asdasdasdsadsasddssa0% (1)

- Six Major Forces in The Broad EnvironmentDocument11 pagesSix Major Forces in The Broad EnvironmentRose Shenen Bagnate PeraroNo ratings yet

- Master Distributor Stock Components: Bulletin HY14-2700/USDocument72 pagesMaster Distributor Stock Components: Bulletin HY14-2700/USYuriPasenkoNo ratings yet

- 01-06-2202-13-40-GMC-Information Radiodiagnosis & ImagingDocument18 pages01-06-2202-13-40-GMC-Information Radiodiagnosis & ImagingSilent StalkerNo ratings yet

- Mangalagiri Proposed Landuse Map PDFDocument1 pageMangalagiri Proposed Landuse Map PDFGurpal kaurNo ratings yet

- Tranfer PF Anand PDFDocument2 pagesTranfer PF Anand PDFShubham ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- The Dilemma: Goodbye, Jimmy, Goodbye.: HIRE Verified WriterDocument9 pagesThe Dilemma: Goodbye, Jimmy, Goodbye.: HIRE Verified WriterBritney Anne H. PasionNo ratings yet

- The Giver Week 4 BookletDocument12 pagesThe Giver Week 4 Bookletapi-315186689No ratings yet

- Smo 3Document6 pagesSmo 3Irini BogiagesNo ratings yet

- MomDocument2 pagesMomSikkim MotorsNo ratings yet

- Le Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDocument8 pagesLe Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDeepika DevarajNo ratings yet

- Lesbian ActivismDocument243 pagesLesbian Activismepcferreira6512No ratings yet

- Hansatsu Exhibit Text OnlyDocument6 pagesHansatsu Exhibit Text OnlyosvarxNo ratings yet

- Shubhangi D. Mulik: Career ObjectiveDocument2 pagesShubhangi D. Mulik: Career ObjectiveShubhangiNo ratings yet

- Sistem Saraf Pusat (SSP) Dan Sistem Saraf Tepi (SST)Document37 pagesSistem Saraf Pusat (SSP) Dan Sistem Saraf Tepi (SST)Kris Canter Eka PutraNo ratings yet

- NET Lab ManualDocument32 pagesNET Lab ManualMadhu Sudan100% (1)

- Work-Life Balance Crafting During COVID-19Document21 pagesWork-Life Balance Crafting During COVID-19Sílvia PereiraNo ratings yet

- EuropassCV-NECHIFOR ENGLEZADocument4 pagesEuropassCV-NECHIFOR ENGLEZAcd13_nechifor1874No ratings yet

- Engineered Elastomeric Void Form: Product DescriptionDocument1 pageEngineered Elastomeric Void Form: Product DescriptionRajdip GhoshNo ratings yet

- The High Performance CompanyDocument6 pagesThe High Performance CompanyVinicius Bessa TerraNo ratings yet

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

Uploaded by

hekiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

P. Kernberg - The CPTI

Uploaded by

hekiCopyright:

Available Formats

Kernberg

Play

reliability

Psychotherapy

____

struments;

Therapystudies.

PF,

Play

Instrument:

Chazan

of

Therapy

JChildren

Psychother

SE, description,

Normandin

and

Pract

Adolescents;

Resdevelopment,

L:1998;

The Childrens

7(3):____

Ratingand

In-

The Childrens Play Therapy

Instrument (CPTI)

Description, Development, and

Reliability Studies

P A U L I N A F. KERNBERG, M.D.

S A R A L E A E. CHAZAN, PH.D.

L I N A N O R M A N D I N , PH.D.

The Childrens Play Therapy Instrument

(CPTI), its development, and reliability T he Childrens Play Therapy Instrument

(CPTI) was constructed to assess the play

activity of a child in psychotherapy. It is in-

studies are described. The CPTI is a new

instrument to examine a childs play activity tended to be of use to clinicians and researchers

in individual psychotherapy. Three as an additional criterion for diagnosissince

children with different diagnoses tend to have

independent raters used the CPTI to rate

different forms of play1,2and as an objective

eight videotaped play therapy vignettes.

instrument to measure change and outcome in

Results were compared with the authors

child treatment. The purpose of this article is

consensual scores from a preliminary study. to describe the instrument and the initial reli-

Generally good to excellent levels of interrater ability studies.

reliability were obtained for the independent

raters on intraclass correlation coefficients for T H E C P T I

ordinal categories of the CPTI. Likewise,

kappa levels were acceptable to excellent for Although several scales have recently been

nominal categories of the scale. The CPTI written to measure the play of children,35 the

holds promise to become a reliable measure of CPTI is specifically intended to be a compre-

play activity in child psychotherapy. Further hensive measure of a childs play activity in

research is needed to assess discriminant psychotherapy. The CPTI adapts several es-

validity of the CPTI for use as a diagnostic tablished scales69 in order to measure play ac-

tool and as a measure of process and outcome. tivity from a variety of perspectives. The CPTI

(The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice provides a tool to describe, record, and analyze

and Research 1998; 7:196207) a childs play activity equivalent to a mental

status formulation of a childs overall function-

Received March 26, 1997; revised January 6, 1998; ac-

cepted January 7, 1998. From The New York Hospital-

Cornell Medical Center, Westchester Division, White

Plains, New York, and Laval University, Quebec, Can-

ada. Address correspondence to Dr. Kernberg, The New

York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, 21 Bloomingdale

Road, White Plains, NY 10605.

Copyright 1998 American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 197

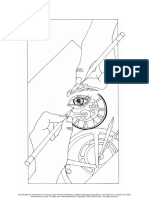

ing following a clinical interview. An TABLE 1. Outline of the Childrens Play Therapy

Instrument (CPTI)

outline of the CPTI appears in Table 1.

Level One: Segmentation of Childs Activity

Level One: Non-Play Activity

Segmentation Pre-Play Activity

Play Activity

Level One analysis addresses the Interruption

different types of activity the child en- Level Two: Dimensional Analysis of the Play Activity

gages in during the psychotherapy Descriptive Analysis

session by segmenting the childs * Category of Play Activity

activity into four categories. These four * Script Description of Play Activity

categories are Pre-Play, Play Activity, * Sphere of Play Activity

Non-Play, and Play Interruption. Seg- Structural Analysis

mentation of the childs activity results Affective Components of Play Activity

in an overview of the distribution and * Childs Affects Modulation

* Affects Expressed by Child While in

span of time of various categories of the

the Play

childs activity in therapy. For example,

* Therapists Affective Tone

segmentation delineates a child who

Cognitive Components of Play Activity

does not play from a child who does; it

* Role Representation

registers the activity of a child who un- * Stability of Representation

dergoes play interruptions and con- (People & Play Object)

trasts it with that of a child who is * Use of Play Object

capable of sustained play activity. It * Style of Role Representation

provides information on the ratio be- (People & Play Object)

tween play activity and non-play activ- Dynamic Components of Play Activity

ity. D uring the session, clinical * Topic of the Play Activity

experience suggests that a child with * Theme of the Play Activity

significant emotional problems will * Level of Relationship Portrayed

within the Play Activity

tend to spend less time engaged in play

* Quality of Relationship within the

activity and will experience interrup- Play Activity

tions due to anxiety or aggression. * Use of Language (Child and Therapist)

Pre-Play is defined as the activity in

Developmental Components of Play Activity

which the child is setting the stage for * Estimated Developmental Level of Play

play. She may pick up a toy and ma- * Gender Identity of Play

nipulate it, arrange play materials, or * Psychosexual Phase Represented in the Play

try out a characters voice or actions. * Separation-Individuation Phase

The predominant purpose of pre-play Represented in the Play

activity is preparation. Pre-play may be * Social Level of Play

prolonged in compulsive or depressed Adaptive Analysis

children. In some instances, the child Coping and Defensive Strategies

will not progress beyond pre-play. Cluster I Cluster II Cluster III Cluster IV

*Normal *Neurotic *Borderline *Psychotic

Play Activity begins if the child be-

*Awareness

comes engrossed in playful activity

often indicated by the adult or child ex- Level Three: Pattern of Child Activity Over Time

Continuity and Discontinuity in

hibiting one or a combination of the fol-

Play Narrative(s)

lowing behaviors: 1) an expression of

intent (e.g., Lets play.); 2) actions in-

2 *Subscale of the CPTI.

dicating initiative, such as definition of

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

198 CHILDRENS PLAY THERAPY I NSTRUMENT

roles (e.g., This dolly will be the teacher; Once the therapy session has been seg-

Lets climb the mountain); 3) an expression mented, a detailed description of one play ac-

of specific positive or negative affects such as tivity segment, based on the videotape, is

glee, delight, pleasure, surprise, anxiety, fear, written. This constitutes a play narrative that

disgust, or boredom; 4) focused concentration; includes the setting of the play, relevant dia-

5) use of toy objects or the physical surround- logue, associated affects, the childs play

ings to develop a narrative. themes, and the childs attitudes and involve-

Normal Play in children is generally an age- ment in the play activity and with the therapist

appropriate, joyful, absorbing activity. It is in- while playing. The play narrative is a central

itiated spontaneously, with a developing integrating database to which the rater returns

theme carried to a resolution; there is a natural when rating any of the individual subscales.

ending and then a move on to another activity. The emphasis is on a frame-by-frame analysis

In contrast, pathological play of children with integrating all the distinctive features of the

the diagnosis of severe disruptive disorders has childs play activity and concomitant affects.

been described as compulsive, joyless, and

monotonous; the play of autistic children is Level Two:

joyless, nonreciprocal, repetitive, with no evi- Dimensional Analysis

dent narrative and no sense of resolution; and

the play of psychotic children is characterized The Dimensional Analysis examines the

by drivenness, sudden fluid transformations of play activity segment using three distinct pa-

the characters in the play, and play disruption. rameters: Descriptive, Structural, and Adap-

From the perspective of segmentation, a child tive.

optimally involved in play can consistently de-

velop play after pre-play preparation and can Descriptive Analysis: The Descriptive Analysis

unfold a play narrative ending naturally in play includes the following subscales: 1) Category

satiation.10 If the length of the segments of play of the Play Activity, which lists nonmutually

is sufficient for the expression of the childs exclusive types of play activity: gross motor

narratives, the patient therapy session is being activity, construction fantasy, game play;

used optimally and/or the patient has im- 2) Script Description, which measures the

proved in her capacity to play. childs initiatives to play, the contribution of

Non-Play refers to a variety of activities or the adult to the unfolding of the childs play,

behaviors of the child outside the realm of the and the interaction between child and thera-

play activity, such as showing reluctance, eat- pist in composing the play; this subscale pro-

ing, reading, doing homework, or conversing vides information regarding the childs

with the therapist. All of these activities or be- autonomy and reciprocity as well as a measure

haviors have in common the absence of in- of therapeutic alliance between therapist and

volvement in play activity and may have child; and 3) Sphere of the Play Activity, which

positive or negative implications in relation to indicates the spatial realms within which the

therapeutic alliance and phase of treatment. play activity takes place: Autosphere (the

Play Interruption is operationally defined as realm of the body); Microsphere (the realm of

any abrupt cessation in a play activityfor ex- small toys), or Macrosphere (the realm of the

ample, if the child must go to the bathroom or actual surroundings).8 This subscale may have

abruptly ends the play activity because of some specific clinical reference in terms of bounda-

extraneous distraction. The time interval of 18 ries, reality testing, maturity, and perspective

to 22 seconds was pragmatically chosen be- taking.

cause raters agreed it was a minimum interval

that could be reliably timed without instru- Structural Analysis: The structural analysis in-

ments. cludes the following measures of a childs play

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 199

activity: 1) Affective Components, 2) Cogni- child is unable to achieve a given complexity

tive Components, 3) Dynamic Components, of role-play, this may reflect a lack of differen-

and 4) Developmental Components. tiation between self and others, an incapacity

Affective Components of Play Activity. The for empathy with and investment in others, or

types and range of emotions brought by the cognitive limitations due to stage of develop-

child to her play reflect those feelings signifi- ment or other causes.9,12 Further, Piaget13 refers

cant in her own life. The link between emo- to failure to view reality from different perspec-

tions and play activity is what brings play alive tives as a failure in decentering. The child is

with understanding. Concentration and in- unrelated to the other person and remains cen-

volvement characterize play activity. The over- tered on herself in an egocentric fashion. Al-

all hedonic tone may vary from positive ternatively, others (including the therapist or

feelings, expressing pleasure, to negative feel- toys) may be animated only as recipients or

ings, associated with conflict.8 When distress extensions of the childs activities. From this

is too threatening to the child, this will eventu- initial point, the child proceeds to playing with

ate in play disruption.8 The childs capacity to therapist and toys as passive recipients and be-

regulate expression of feelings will affect gins to comprehend the give and take of recip-

and/or reflect the organization of play.11 The rocal roles and their reactions.

greater capacity for smooth transitions and A major advance occurs when the child is

regulation of affect reflects an integration of capable of expressing independent intention-

the childs subjective world, and it is a key to ality for a toy or a person. At this important

the capacity to play at the highest levels of crea- juncture the child has become capable of as-

tivity. If the child is able to gain expression of suming a different role, other than her own,

intense feelings through play, she has made without experiencing the threat that she herself

giant steps toward coping and mastery. The might disappear. An example of this type of

capacity to play symbolically implies the ca- cognitive anxiety occurs on Halloween, when

pacity for regulation of emotions. Indeed, some young children, 3 to 4 years old, exhibit

scenarios portrayed with intensity and a wide fear of being in disguise. The costume suggests

range of emotions can be assumed to be of to the young child that she could disappear.

great significance to the child. However, at a later age a child can tolerate

Cognitive Components of Play Activity. This donning a disguise and playing anothers role;

modified scale was based on the work of Inge she has gained self-constancy.

Bretherton6 on symbolic play. The structure of Dynamic Components of Play Activity. The

the social representational world is a crucial topic of play reveals important emotional

dimension of the childs play. From a cognitive themes to the child. A child who repetitively

perspective, it indicates the degree to which a engages in play about particular topics is com-

child is capable of creating narrative structures municating about the types of conflicts he is

to represent different affect-laden relation- dealing with at the time: fear of death, sexual

ships. Beginning role-play is the child pretend- themes, competitiveness. The theme indicates

ing he is another person, or animating a toy or the narrative of the play enacted by particular

anothers behavior. In its most complex form, characters. It is important to keep in mind what

role-play becomes directorial play or narrator topics and themes might be expected for a

play, with several interacting roles, enlivened given developmental perspective and what mi-

by the child with a variety of emotional themes. nor discrepancies might represent divergence

Younger children are capable of only sim- from this expected pattern. The divergence

ple representations; older children may draw may be significant in conveying a specific con-

from a varied repertoire. The level of role rep- cern of the child.

resentation also indicates progression and re- The level of relationship portrayed within

gression in the childs level of functioning. If a the play activity specifies the pattern of inter-

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

200 CHILDRENS PLAY THERAPY I NSTRUMENT

actions between play characters. The level of appearance. The concept of a spectrum of

dyadic, triadic, and oedipal configurations clusters of coping and defensive strategies was

places the child at different points of personal- based on the writings of Vaillant,23 Perry et

ity organization, from severely disturbed per- al.,24 and P. Kernberg.25

sonalities to neurotic or normal ones. A final subscale measures the childs

The Quality of Relationship Within the awareness that he is engaged in play activity.

Play Activity segment is an adaptation of the This subscale condenses several cognitive and

Urist Scale,9 as written for children by Tuber,14 affective variables that determine how capable

and the scale of Diamond et al.15 It assesses, the child is of observing himself at play, or,

through the dynamics of the narrative, the na- alternatively, the extent to which he and his

ture of the childs emotional conflicts and the surroundings have been completely absorbed

extent of expression of aggressiondirect, into the play.

attenuated, neutralized, or sublimatedthat As outlined above, each of the CPTI scales

he exercises over his subjective world, i.e., (Descriptive, Structural, and Adaptive) con-

autonomous, dependent, and destructive in- sists of several subscales (see Table 1). Depend-

teraction among play characters. ing on the interests of the examiner, he or she

Developmental Components of Play Activity. may use the CPTI in its entirety or may select

This dimension compares the childs activity only certain scales or combinations of sub-

with play of other children of the same age, scales.

gender, and level of emotional and social de-

velopment. This analysis implies an underly- Level Three:

ing epigenetic sequence to the unfolding of a Patterns Over Time

childs capacity to play. It is a relative judgment

and depends on cultural and social standards This level of analysis refers to patterns of

and values. Because play unfolds in a socially the childs activity over time and seeks to assess

shared context, group norms are appropriate changes in treatment. The patterns of segmen-

to evaluate the childs play. Ideally, play activ- tation are expected to change over time. For

ity is consistent across developmental dimen- example, the sequence and length of the

sions. different segments of the childs activityPre-

Several different sources supplied informa- play, Play Activity, Non-play, and Interrup-

tion for the compilation of these last categories. tionchange in the course of treatment

Gender identity assessment was influenced depending on the childs diagnosis and type of

by the writing of Erikson,8,10,16 Coates,17 and treatment. However, this level of analysis will

Zucker;18 psychosexual phases were based on not be addressed in this article.

the writings of Anna Freud19 and Peller;20 sepa-

ration-individuation phases were based on the P R E L I M I N A R Y

writings of Mahler;21 and the social level of play R E L I A B I L I T Y S T U D Y

includes Winnicotts concept of the capacity to

play alone.22 Construction of the instrument required

multiple observations of videotaped play ther-

Adaptive Analysis: The adaptive analysis as- apy sessions. The associated discussions in-

sesses the overall purpose of the play activity volved 10 experienced clinicians over a span

for the playing child. The childs observable of 3 years. The authors of the scale gleaned

play behaviors are classified as manifesting material from these discussions to write a man-

specific coping/defensive strategies grouped ual defining the primary dimensions of the

into four clusters: 1) Normal, 2) Neurotic, 3) CPTI and formulating operational definitions

Borderline, and 4) Psychotic. These clusters for each scale and subscale, with clinical illus-

may be placed in sequence in order of their trations.

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 201

Methods and Results These scores ranged from ICC 0.50 to 0.79.

For example, Affects Expressed in Play, ICC

A preliminary reliability study was = 0.77; Stability of Role Representation, ICC

planned using three members of the group as = 0.79; Developmental Level of Play, ICC =

raters. A videotape montage consisting of eight 0.50; Social Level of Play, ICC = 0.56. Low

clinical vignettes was composed by an inde- scores were obtained on Role Representation,

pendent clinician trained to identify the differ- ICC = 0.29; Use of Play Object, ICC = 0.33;

ent categories of child activity. The main and Use of Language, ICC = 0.32. The Adap-

selection criterion was to find segments that tive dimension produced the lowest results,

contained at least one segment of play activity ICC = 0.09.

and any of the other three child activities (Pre- Despite acceptable levels of agreement be-

Play, Non-Play, and Interruption). Table 2 de- tween raters on many of the subscales, there

scribes the sample. were disparities on some subscales, which were

attributed primarily to the lack of sufficient

specificity in definition of categories in the

Level One (Segmentation): The three raters

manual. A decision was made to revise the

(one psychiatrist, two psychologists) were

scoring manual and refine the definitions.

child therapists, each with more than 10 years

To establish a consensual rating to be used

of clinical experience. They rated the eight

as a standard for new independent raters, the

vignettes independently, with subsequent dis-

raters of the preliminary study performed an

cussions of the ratings to improve on the clar-

item-by-item analysis of the ratings of the eight

ity of the segmentation in the manual.

vignettes.

Agreement on the segmentation of the

childs activity into four categories (Pre-Play, R E L I A B I L I T Y S T U D Y :

Non-Play, Play, and Interruption) as measured I N D E P E N D E N T R A T E R S

by the weighted kappa coefficient was 0.69.26 A N D C O M P A R I S O N W I T H

This level of agreement between the judges on C O N S E N S U S

segmentation is considered to be good.*

Methods

Level Two (Dimensional Analysis): Two raters

(one psychiatrist, one psychologist) completed Three independent raters, recruited from

ratings for level two. Analysis of the play ac- different institutions, rated the same eight

tivity segments was done by using intraclass videotaped vignettes used in the preliminary

correlation coefficient (ICC)28 for ordinal cate- reliability study. The raters were all child psy-

gories of the CPTI and kappa for the nominal chologists, ranging in experience from 1 to 12

ones. The most consistent subscale scores years in child therapy. They received 15 hours

were obtained on the Descriptive dimension of training from one of the authors (a psycholo-

of the CPTI. For example, Category of Play gist). The training consisted of group discus-

Activity, ICC = 0.68; Script Description, ICC sions based on definitions and descriptions of

= 0.70; Sphere of Play Activity, ICC = 0.88.** the CPTI scales found in the manual.

Among the Structural and Adaptive Eight vignettes were selected from a set of

scales, good to excellent scores were obtained 19 videotaped play therapy sessions by an

for all the subscales on these dimensions. independent clinician who was trained to

*

Landis and Koch27 furnished criteria to assess the level of agreement between judges as calculated

from the kappa: 0.00 to 0.39 poor; 0.40 to 0.74 acceptable to good; 0.75 to 1.00 excellent.

**

Jones et al.29 suggested 0.70 agreement as an acceptable level when complex coding schemes are

used; Gelfand and Hartmann30 recommend 0.60.

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

202 CHILDRENS PLAY THERAPY I NSTRUMENT

identify the different Level One categories of Three types of reliability estimates were

Childs Activity, namely Pre-Play, Play, Non- derived from data, according to the different

Play, and Interruption. The main selection cri- types of scales constituting the CPTI and the

terion was to find segments that contained at number of raters used in the experiment.

least one Play Activity, defined as a narrative Reliability of the categorical data obtained

with a beginning and an end, and any of the from the segmentation of the eight vignettes

other three Child Activities. Also, the vignettes (Level One) was appraised by using a weighted

were chosen to provide a varied array of child kappa.26 Disagreements between different

diagnoses, levels of therapist experience, and categories have different clinical implications.

phases of treatment. The duration of the For example, it is more serious to rate equally

vignettes ranged from 4 minutes, 6 seconds, to Play and Non-Play than Pre-Play and Play.

11 minutes, 34 seconds, with a mean of 7 min- Therefore, the relative importance of different

utes, 47 seconds, and a standard deviation of types of disagreement among the four catego-

2 minutes, 37 seconds (see Table 2). ries of the Child Activity (Pre-Play, Play, Non-

To maintain each raters accuracy, ratings Play and Interruption) was established in order

sessions were split into two parts, as suggested to perform the data analysis. A disagreement

by Hartmann,31 each part consisting of the between Play, Non-Play, or Pre-Play and In-

CPTI-based rating of four vignettes followed terruption gets a weight of 1.00; a disagreement

by a discussion with the trainer. between Play and Non-Play gets a weight of

After the submission of the whole ratings, 0.75; a disagreement between Pre-Play and

discussion and comparison with the authors Non-Play gets a weight of 0.50; and a disagree-

consensus ratings were conducted. Reliability ment between Play and Pre-Play gets a weight

estimates were obtained for the degree of of 0.25. However, weighted kappa is restricted

agreement of each individual rater with the to cases where the number of raters is two

consensus. The raters contributed to the clari- and the same two raters rate each subject

fication of the manual categories and to their (vignette).28 In this study, we will present a

training by the exchange of opinions and clini- mean weighted kappa derived from each pair

cal examples from their own experience. of raters.

TABLE 2. Description of the eight vignettes

Phase of

Therapist Patient Diagnosis Therapy Duration

1. 1st-year child resident 56-year-old boy Adjustment reaction disorder Middleadvanced 625

Grief reaction

2. Resident psychology intern 5-year-old girl Stress disorder Middleadvanced 654

Physical child abuse

Failure to thrive

3. Senior therapist >15 years 57-year-old boy Gender identity disorder Earlymiddle 836

Posttraumatic stress disorder

4. Therapist 5 years 9-year-old boy Oppositional defiant disorder Late 1134

5. 2nd-year child resident 7-year-old girl Separation anxiety disorder Middleadvanced 802

Avoidant disorder

6. Psychology intern 5-year-old girl Posttraumatic stress disorder Middleadvanced 506

Physical child abuse

Failure to thrive

7. Senior therapist > 15 years 912-year-old boy Pervasive developmental disorder Beginning 406

Autism

8. Senior therapist > 20 years 10-year-old boy Conduct disorder Middle 902

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 203

For reliability of the categorical scales tendency of 0.71, with a range from acceptable

from Level Two of the CPTI, namely Category to excellent (ICC 0.520.89). However, there

of Play Activity, subscales of Child and Adult are two subscales at unacceptable levels of re-

Script Description, Topic, Theme, and Gender liability, namely Separation-Individuation

Identity, a multiple-rater kappa is estimated,32,33 Phases Represented in the Play (ICC = 0.43),

in which the average pairwise kappas are ad- an increment over earlier findings but still be-

justed for covariation among pairwise kappas low acceptable levels, and Borderline cop-

and chance agreements. ing/defensive mechanisms (ICC = 0.45),

For appraising reliability of the remaining lower than the acceptable levels obtained for

quantitative scales of the CPTI (ordinal scale other coping/defensive mechanisms.

ranging from 1 to 5), an intraclass correlation Generally, the new raters did almost as

coefficient is calculated, using a two-way analy- well as the authors of the scale and in several

sis of variance, where the three raters are con- instances were able to obtain higher levels of

sidered random effects. Thus, differences at the interrater reliability. Significant improvements

between-raters level are included as error from were seen in Style of Role Representation: Play

the analysis. The choice of this statistic is based Object (ICC = 0.83, compared with 0.38);

on the wish of the authors to generalize the Separation-Individuation Phase Represented

estimated results to raters who have at least in the Play (ICC = 0.43, compared with 0.21).

1 year of clinical experience and as much as

12 years of experience, so that the CPTI could Individual Rater Agreement With the Consensus:

be reliably used by a variety of clinicians.34,35 Each raters performance was compared with

the standard provided by the consensus of the

Results authors of the scale. Results indicate that, over-

all, satisfactory to excellent agreement with the

Level One: Segmentation: Agreement among standard was obtained by all three judges. For

three raters on the segmentation of a childs example, the intraclass correlation coefficients

activity into four categories (Pre-Play, Play for seven main subscales of the CPTIspecif-

Activity, Interruption, and Non-Play) as mea- ically the global scores for Script Description,

sured by the weighted kappa coefficient was Affective, Cognitive, Developmental, and Dy-

0.72. namic components; Adaptive functions; and

Awarenessshow a mean of ICC = 0.81 (range

Level Two: Dimensional Analysis: Interrater re- 0.610.94) for Rater A; a mean of ICC = 0.84

liabilities measured by the kappa coefficient (range 0.690.92) for Rater B; and a mean of

for the twelve categorical subscales of the ICC = 0.84 (range 0.710.96) for Rater C.

CPTI indicate an average coefficient of 0.65, Further comparisons were performed for

with range 0.42 to 1.00 (Table 3). The single each individual vignette and revealed a similar

exception was 0.12, Initiation of Play by Adult. pattern of results on the main structural cate-

The kappa statistic is extremely sensitive gories of the CPTI. Raters A, B, and C reached

to an unbalanced distribution of categories good to excellent agreement with the standard.

(presence versus absence), and this sensitivity The intraclass correlation coefficients for the

accounted for some of the variability in our four main structural categories of the CPTI,

results. specifically the global scores for Affective,

The intraclass correlation coefficients Cognitive, Developmental, and Dynamic

for the 25 main ordinal subscales of the components, show a mean of ICC = 0.62

CPTIspecifically the global scores for Script (range 0.580.85) for Rater A; a mean of ICC

Description, Affective, Cognitive, Develop- = 0.73 (range 0.590.81) for Rater B; and a

mental, and Dynamic components; Adaptive mean of ICC = 0.69 (range 0.630.75) for

functions; and Awarenessshow a mean Rater C.

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

204 CHILDRENS PLAY THERAPY I NSTRUMENT

TABLE 3. Interrater reliability among three raters as measured by kappa and intraclass correlation

coefficients (ICC)

Variable Kappa % Agreementa ICC

Category of the Play Activity Segment 0.50 81.0 NA

Script Description of the Play Activity Segment (Global) NA 0.89

Script Description (Child) NA 0.86

Initiation of Play 1.00 100.0 NA

Facilitation of Play 1.00 100.0 NA

Inhibition of Play 0.47 87.2 NA

Ending of Play 0.52 80.0 NA

Script Description (Adult) NA 0.87

Initiation of Play 0.12 44.4 NA

Facilitation of Play 1.00 100.0 NA

Inhibition of Play 0.42 86.1 NA

Ending of Play 1.00 100.0 NA

Contribution of Participants (Child) NA 0.89

Contribution of Participants (Adult) NA 0.57

Sphere of the Play Activity NA 0.92

Affective Components of the Play Activity Segment (Global) NA 0.84

Childs Affects Modulation NA 0.70

Affects Expressed by the Child while in the Play NA 0.73

Therapists Affective Tone NA 0.66

Cognitive Components (Global) NA 0.80

Role Representation NA 0.72

Stability of Representation (People) NA 0.83

Stability of Representation (Play Object) NA 0.84

Use of Play Object NA 0.88

Style of Role Representation (People) NA 0.64

Style of Role Representation (Play Object) NA 0.83

Dynamic Components of the Play Activity Segment (Global) 0.63 92.3 0.68

Topic of the Play Activity Segment 0.66 94.1 NA

Theme of the Play Activity Segment 0.60 90.7 NA

Level of Relationship Portrayed within the Play Activity Segment NA 0.82

Quality of Relationship within the Play Activity Segment NA 0.70

Use of Language by the Child NA 0.68

Use of Language by the Therapist NA 0.57

Developmental Components of the Play Activity (Global) NA 0.62

Estimated Developmental Level of Play NA 0.90

Gender Identity of Play 0.90 NA

Psychosexual Phase Represented in the Play NA 0.72

Separation-Individuation Phase Represented in the Play NA 0.43

Social Level of Play: Interaction with the Therapist NA 0.63

Adaptive Analysis of the Play Activity (Global) NA 0.65

Cluster I NA 0.81

Cluster II NA 0.64

Cluster III NA 0.45

Cluster IV NA 0.60

Awareness NA 0.52

2 aPercentage agreement among the three judges.

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 205

These comparisons were derived from the cians who receive a minimum of 15 hours of

consensual mean and standard deviation intensive training.

scores obtained for each vignette (Table 4). Despite the small number of vignettes

One should note that vignettes that are associ- used to establish the reliability of the instru-

ated with high mean scores and small standard ment, it must be stated that the vignettes em-

deviation scores are mainly associated with the brace the whole spectrum of the different

middleadvanced and late phases of treat- ordinal scales. The vignettes that showed

ment, whereas low mean scores and large higher mean scores with smaller standard

standard deviation scores are associated with deviations were associated with the middle

vignettes from the beginning or middle phases advanced and late phases of treatment; lower

of treatment. mean scores with larger SDs were associated

with vignettes from the beginning or middle

D I S C U S S I O N phases of treatment. Likewise, the raters were

consistently able to make these sensitive dis-

These preliminary studies demonstrate the fea- tinctions. However, in some subscales using

sibility of using the CPTI to measure a childs the kappa, reliabilities were lowered by a pre-

activity in psychotherapy. The CPTI provides ponderant representation of one of the catego-

a means to identify play activity within a psy- ries over the other; for example, (Adult)

chotherapy session. The play activity is then Initiation of Play ( = 0.12) and Functional

measured from three different perspectives: analysis: Cluster II ( = 0.41). This dispropor-

descriptive, structural, and adaptive. Each of tionate pattern was likely to lower the reliabil-

these dimensions consists of individual sub- ity coefficient each time a disagreement on the

scales that are operationally defined. The less represented category was encountered.

quantification of these subscales provides both The Separation-Individuation category of

the flexibility to derive individual profiles of the Developmental scale gave results below ac-

play activity in psychotherapy and a method- ceptable standards. A closer examination of

ology to identify relevant dimensions of a raters individual ratings showed a wide dis-

childs play activity. crepancy among raters. This scale clearly re-

Training procedures established the credi- quired further definition, particularly as it

bility of these measures in assessing play activ- pertains to higher-functioning children. Fur-

ity. The independent raters, with varying levels ther work on clarifying the phases of separa-

of experience, required 15 hours of training to tion-individuation represented in the childs

reach satisfactory levels of agreement. This re- play resulted in a revision of the definitions of

sult is preliminary evidence to suggest CPTI these categories in the manual. Specifically,

may be a usable tool for researchers and clini- new examples illustrating these phenomena in

TABLE 4. Means and standard deviations of the average rating for the main structural categories of

each vignette

Vignette Number and Phase of Treatment

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Variable M-A M-A M-E L M-A M-A B M

Affective (Global) 3.2 1.1 4.2 0.8 2.8 1.7 3.7 0.9 3.5 1.1 4.1 0.6 1.7 2.3 2.7 2.1

Cognitive (Global) 3.7 1.2 3.9 0.5 2.9 2.1 2.9 0.5 3.5 1.2 4.3 1.2 1.5 1.6 3.4 1.3

Dynamic (Global) 4.2 0.6 2.7 1.4 2.7 2.4 3.3 1.1 2.7 1.5 3.5 0.6 1.7 2.1 2.9 1.9

Developmental (Global) 3.0 0.9 3.1 0.7 2.8 1.5 3.3 0.9 2.9 0.8 3.1 0.9 1.4 2.2 2.7 1.8

2 Note: Phases of treatment: M-A = middleadvanced; M-E = middleearly; L = late; B = beginning; M = middle.

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

206 CHILDRENS PLAY THERAPY I NSTRUMENT

children with mild emotional disorders were and accompanying manual, raters were

added in the training. In the prior reliability trained to obtain satisfactory to excellent levels

studies, raters had experienced difficulty mak- of agreement on the segmentation and dimen-

ing meaningful reference to these categories, sions of a childs play activity occurring within

except in cases of severe disturbance (psychosis a psychotherapy session. In addition, each of

and autism). After a 2-month hiatus, the Sepa- these trained raters obtained good to excellent

ration-Individuation subscale was readminis- agreement with the consensus standard for the

tered to the group of three trained raters, and scale reached by the authors of the scale. Future

the results obtained were good: ICC = 0.63. planned studies include obtaining reliability

Looking toward the future, a larger data- on a larger new sample of play sessions and

base is required, to include both clinical and evaluating sequences of play sessions over

nonclinical children, to establish definitive re- time. In addition, future validity studies are

liability and to validate the sensitivity and planned to investigate the concurrence of play

specificity of the CPTI as a diagnostic tool that profiles with diagnostic categories, attachment

discriminates distinctive psychopathological behaviors, and outcome variables. These pre-

profiles and is sensitive to changes occurring liminary findings indicate that the CPTI holds

in the course of treatment. promise to become a diagnostic instrument

and outcome measure of a childs play activity

S U M M A R Y in psychotherapy.

We described the development of a new and The authors acknowledge with appreciation the

comprehensive measure of a childs play ac- participation of Elsa Blum, Ph.D., Pauline Jordan,

tivity in psychotherapy, the CPTI, and pre- Ph.D., Judith Moskowitz, Ph.D., and Risa Ryger,

sented reliability studies. Using the instrument Ph.D.

R E F E R E N C E S

1. Kernberg PF: Las formas del juego: una comunicacin 8. Erikson EH: Studies in the interpretation of play. Ge-

preliminar [The forms of play: a preliminary commu- netic Psychology Monographs 1940; 22:557671

nication]. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicoanlisis 9. Urist J: The Rorschach test and the assessment of ob-

1996; 1:197201 ject relations. J Pers Assess 1977; 41:39

2. Kernberg PF, Chazan SL, Normandin L: The Cornell 10. Erikson EH: Further explorations in play construc-

Play Therapy Instrument. Poster presented at the an- tions. Psychol Bull 1941; 38:748756

nual meeting of the Society for Psychotherapy Re- 11. Sorce JE, Emde RN: Mothers presence is not enough:

search, York, England, June 1994 effect of emotional availability on infant exploration.

3. Greenspan SI, Lieberman AF: Representational Dev Psychol 1981; 17:737745

elaboration and differentiation: a clinical-quantitative 12. Stern D: The Interpersonal World of the Infant. New

approach to the clinical assessment of 24 year olds, York, Basic Books, 1985

in Children at Play, edited by Slade A, Wolf DP. New 13. Piaget J: The Construction of Reality in the Child. New

York, Oxford University Press, 1994, pp 332 York, Basic Books, 1954

4. Lindner TW: Transdisciplinary Play-based Assess- 14. Tuber S: Assessment of childrens object repre-

ment. Baltimore, Paul H. Brookes, 1990 sentations with Rorschach. Bull Menninger Clin 1989;

5. Schaefer CE, Gitlin K, Sandgrund A: Play Diagnosis 53:432441

and Assessment. New York, Wiley, 1991 15. Diamond D, Kaslow N, Coonerty S, et al: Changes in

6. Bretherton I: Representing the social world in sym- separation-individuation and intersubjectivity in long

bolic play, in Symbolic Play, edited by Bretherton I. term treatment. Psychoanalytic Psychology 1990;

New York, Academic Press, 1984, pp 341 7:363397

7. Emde RN, Sorce JE: The rewards of infancy: emo- 16. Erikson EH: Childhood and Society, 2nd edition. New

tional availability and maternal referencing, in Fron- York, Norton, 1963

tiers of Infant Psychiatry, vol 2, edited by Call JD, 17. Coates S, Tuber SB: The representation of object re-

Galenson E, Tyson R. New York, Basic Books, 1983, lations in the Rorschachs of extremely feminine boys,

pp 1730 in Primitive Mental States and the Rorschach, edited

VOLUME 7 NUMBER 3 SUMMER 1998

KERNBERG ET AL. 207

by Lerner H, Lerner P. Madison, CT, International with provision for scaled disagreement or partial

Universities Press, 1988, pp 647664 credit. Psychol Bull 1968; 70:213220

18. Zucker KJ, Bradley SJ: Gender Identity Disorder and 27. Landis JR, Koch CG: The measurement of observer

Psychosexual Problems in Children and Adolescents. agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;

New York, Guilford, 1992 33:159174

19. Freud A: The concept of developmental lines. Psycho- 28. Bartko JJ: On various intraclass correlation coeffi-

anal Study Child 1963; 18:245265 cients. Psychol Bull 1976; 83:762763

20. Peller LE: Libidinal phases, ego development and 29. Jones RR, Reid JB, Patterson GR: Naturalistic obser-

play. Psychoanal Study Child 1954; 9:178198 vation in clinical observation, in Advances in Psycho-

21. Mahler M, Pino F, Bergman A: The Psychological logical Assessment, vol 3, edited by McReynolds P.

Birth of the Human Infant. New York, Basic Books, San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass, 1973, pp 4295

1975 30. Gelfand DM, Hartmann DP: Child Behavior Analysis

22. Winnicott D: Playing and Reality. New York, Basic and Therapy. New York, Pergamon, 1975

Books, 1971 31. Hartmann DP: Assessing the dependability of obser-

23. Vaillant GE, Bond M, Vaillant CO: An empirically vational data, in Using Observers to Study Behavior,

validated hierarchy of defense mechanisms. Arch Gen edited by Hartmann DP. San Francisco, CA, Jossey-

Psychiatry 1986; 43:786794 Bass 1982, pp 5165

24. Perry CJ, Kardos ME, Pagano CJ: The study of de- 32. Conger AJ: Integration and generalization of kappas

fenses in psychotherapy using the Defense Mechanism for multiple raters. Psychol Bull 1980; 88:322328

Rating Scale (DMRS), in The Concept of Defense 33. Hubert L: Kappa revisited. Psychol Bull 1977; 84:289

Mechanisms in Contemporary Psychology: Theoreti- 297

cal, Research, and Clinical Perspectives, edited by 34. Shrout PE, Fleiss JL: Intraclass correlations: uses in

Hentschel U, Ehlers W. New York, Springer, 1993, pp assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 1979; 86:420

122132 428

25. Kernberg PF: Current perspectives in defense mecha- 35. Fleiss JL, Shrout PE: Approximate interval estimation

nisms. Bull Menninger Clin 1994 58:5587 for a certain intraclass correlation coefficient. Psy-

26. Cohen J: Weighed kappa: nominal scale agreement chometrika 1978; 43:259262

JOURNAL OF PSYCHOTHERAPY PRACTICE AND RESEARCH

You might also like

- CreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Document28 pagesCreativeWriting12 Q1 Module-1Burning Rose89% (140)

- 112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Document20 pages112200921441852&&on Violence (Glasser)Paula GonzálezNo ratings yet

- YP CORE User ManualDocument36 pagesYP CORE User Manualloubwoy100% (4)

- BukowskiDocument5 pagesBukowskisalome davitulianiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingDocument94 pagesChapter 20 - Culturally Adaptive InterviewingNaomi LiangNo ratings yet

- Mapa de Duelo ArtículoDocument19 pagesMapa de Duelo ArtículoCristian Steven Cabezas JoyaNo ratings yet

- Child Parent Psychotherapy - Alicia LiebermanDocument16 pagesChild Parent Psychotherapy - Alicia Liebermanapi-279694446No ratings yet

- CHRISTIAN LIVING EDUCATION 2 - Summative Test 2 - 3rd QuarterDocument5 pagesCHRISTIAN LIVING EDUCATION 2 - Summative Test 2 - 3rd Quarterjanet100% (1)

- EMI Therapy: clinical cases treated and commented step by step (English Edition)From EverandEMI Therapy: clinical cases treated and commented step by step (English Edition)No ratings yet

- Comprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Volume 1: Intellectual and Neuropsychological AssessmentFrom EverandComprehensive Handbook of Psychological Assessment, Volume 1: Intellectual and Neuropsychological AssessmentNo ratings yet

- Interoception and CompassionDocument4 pagesInteroception and CompassionMiguel A. RojasNo ratings yet

- Coherence Therapy (Previously, Depth-Oriented Brief Therapy)Document13 pagesCoherence Therapy (Previously, Depth-Oriented Brief Therapy)Paola AlarcónNo ratings yet

- 1968 - Kiresuk, T. Sherman, R.Document11 pages1968 - Kiresuk, T. Sherman, R.nataliacnNo ratings yet

- From Perception To Action: The Role of Auditory and Visual Information in Perceiving and Performing Complex MovementsDocument239 pagesFrom Perception To Action: The Role of Auditory and Visual Information in Perceiving and Performing Complex MovementsN SchaffertNo ratings yet

- A Proposal For An EMDR Reverse ProtocolDocument3 pagesA Proposal For An EMDR Reverse ProtocolLuiz Almeida100% (1)

- The Gender You Are and The Gender You Like - Sexual Preference and Empathic Neural ResponsesDocument10 pagesThe Gender You Are and The Gender You Like - Sexual Preference and Empathic Neural Responsesgabriela marmolejoNo ratings yet

- Interventions For Children With RADDocument6 pagesInterventions For Children With RADJohn BitsasNo ratings yet

- Bottom-Up and Top-Down Emotion GenerationDocument10 pagesBottom-Up and Top-Down Emotion GenerationTjerkDercksenNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenology of TraumaDocument4 pagesThe Phenomenology of TraumaMelayna Haley0% (1)

- Working With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewDocument5 pagesWorking With Trauma Lacan and Bion ReviewIngridSusuMoodNo ratings yet

- Emdr 2002Document14 pagesEmdr 2002jivinaNo ratings yet

- Self Reflective Essay For Foundations of Counselling Anc PsychotherapyDocument6 pagesSelf Reflective Essay For Foundations of Counselling Anc PsychotherapyRam MulingeNo ratings yet

- The Termination Phase: Therapists' Perspective On The Therapeutic Relationship and OutcomeDocument13 pagesThe Termination Phase: Therapists' Perspective On The Therapeutic Relationship and OutcomeFaten SalahNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFDocument20 pagesCognitive Behavior Theraphy PDFAhkam BloonNo ratings yet

- Radically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RODBT) : Who Is The Program For?Document1 pageRadically Open Dialectical Behavioural Therapy (RODBT) : Who Is The Program For?Ruslan IzmailovNo ratings yet

- The Racket System: A Model For Racket Analysis: Transactional Analysis Journal January 1979Document10 pagesThe Racket System: A Model For Racket Analysis: Transactional Analysis Journal January 1979marijanaaaaNo ratings yet

- Ansa Manual Sfy2017Document41 pagesAnsa Manual Sfy2017bhojaraja hNo ratings yet

- Loving Eyes ProtocolDocument1 pageLoving Eyes ProtocolMarta Casillas100% (1)

- Valeria Grishko Animal Guides in LifeDocument6 pagesValeria Grishko Animal Guides in LifeVerónicaMonyo100% (1)

- Tuguinay, Joshua FLA6 Later Views On Object Relations (Concept Map)Document1 pageTuguinay, Joshua FLA6 Later Views On Object Relations (Concept Map)Joshua TuguinayNo ratings yet

- DiagnosingDocument10 pagesDiagnosingAnonymous PIUFvLMuVONo ratings yet

- Pre TherapyDocument11 pagesPre TherapyВладимир ДудкинNo ratings yet

- Main 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentDocument25 pagesMain 1991 Metacognitive Knowledge Metacognitive Monitoring and Singular Vs Multiple Models of AttachmentKevin McInnes0% (1)

- Carl RogersDocument5 pagesCarl RogersHannah UyNo ratings yet

- The Assessment of Children With Attachment Disorder - The Randolph PDFDocument161 pagesThe Assessment of Children With Attachment Disorder - The Randolph PDFAnonymous g3sy0uINo ratings yet

- Book Review An Action Plan For Your Inner Child Parenting Each OtherDocument3 pagesBook Review An Action Plan For Your Inner Child Parenting Each OtherNarcis NagyNo ratings yet

- The Psychiatrization of Difference: Frangoise Castel, Robert Caste1 and Anne LovellDocument13 pagesThe Psychiatrization of Difference: Frangoise Castel, Robert Caste1 and Anne Lovell123_scNo ratings yet

- Family System TheoryDocument23 pagesFamily System TheoryZaiden John RoquioNo ratings yet

- Gestalt Peeling The Onion Csi Presentatin March 12 2011Document6 pagesGestalt Peeling The Onion Csi Presentatin March 12 2011Adriana Bogdanovska ToskicNo ratings yet

- Expertise in Therapy Elusive Goal PDFDocument12 pagesExpertise in Therapy Elusive Goal PDFJonathon BenderNo ratings yet

- Approaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionDocument33 pagesApproaching Countertransference in Psychoanalytical SupervisionrusdaniaNo ratings yet

- Stern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreDocument17 pagesStern, D.N., Sander, L.W., Nahum, J.P., Harrison, A.M., Lyons-Ruth, K., Morgan, A.C., Bruschweilerstern, N. and Tronick, E.Z. (1998). Non-Interpretive Mechanisms in Psychoanalytic Therapy- The Something MoreJulián Alberto Muñoz FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Use of Flash Technique On A GroupDocument1 pageUse of Flash Technique On A GroupElisa ValdésNo ratings yet

- Running Header: ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT 1Document28 pagesRunning Header: ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT 1Coleen AndreaNo ratings yet

- Existential Phenomenological Psychotherapy - "Working With Internalizations" Part 2Document8 pagesExistential Phenomenological Psychotherapy - "Working With Internalizations" Part 2Rudy BauerNo ratings yet

- Standard Progressive MatricesDocument6 pagesStandard Progressive MatricesZoya SajidNo ratings yet

- Piperno, F., Biasi, S. & Levi, G. (2007) - Evaluation of Family Drawings of Physically and Sexually Abused ChildrenDocument10 pagesPiperno, F., Biasi, S. & Levi, G. (2007) - Evaluation of Family Drawings of Physically and Sexually Abused ChildrenRicardo NarváezNo ratings yet

- MBT I ManualDocument42 pagesMBT I ManualMauroNo ratings yet

- 09 - Kohut & Wolf - 1978 - The Disorders of The Self and Their TreatmentDocument13 pages09 - Kohut & Wolf - 1978 - The Disorders of The Self and Their TreatmentRebeca UrbonNo ratings yet

- The Wounded Healer As Cultural ArchetypeDocument10 pagesThe Wounded Healer As Cultural ArchetypeScotNo ratings yet

- Bosmans, 2010 - Attachment and Early Maladaptive SchemasDocument26 pagesBosmans, 2010 - Attachment and Early Maladaptive SchemasElaspiriNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Play Therapy On Reduction ofDocument6 pagesThe Effectiveness of Play Therapy On Reduction ofHira Khan100% (1)

- The Empty ChairDocument1 pageThe Empty Chairapi-244827434No ratings yet

- Infant and Early Childhood Mental Health Core Concepts and Clinical Practice by Kristie Brandt Bruce D. Perry Stephen Seligman Ed TronickDocument382 pagesInfant and Early Childhood Mental Health Core Concepts and Clinical Practice by Kristie Brandt Bruce D. Perry Stephen Seligman Ed TronickRucsandra Murzea100% (1)

- Psychodynamic Diagnostic ManualDocument6 pagesPsychodynamic Diagnostic Manualas9as9as9as9No ratings yet

- Gabbard Suport TerapiDocument25 pagesGabbard Suport TerapiAgit Z100% (1)

- Transcript of Therapy Session by Douglas BowerDocument12 pagesTranscript of Therapy Session by Douglas Bowerjonny anlizaNo ratings yet

- The Satir Model: Yesterday and Today: John BanmenDocument16 pagesThe Satir Model: Yesterday and Today: John BanmenLaura LinaresNo ratings yet

- Nancy McWilliams - Beyond Traits - Personality As Intersubjective ThemesDocument30 pagesNancy McWilliams - Beyond Traits - Personality As Intersubjective Themesmeditationinstitute.netNo ratings yet

- Therapist As A Container For Spiritual ExperienceDocument27 pagesTherapist As A Container For Spiritual ExperienceEduardo Martín Sánchez Montoya100% (1)

- OH Cards and Their Counterparts (Atkinson K., Wells C.) (Z-Library)Document11 pagesOH Cards and Their Counterparts (Atkinson K., Wells C.) (Z-Library)Merce VisanoNo ratings yet

- MCMI IV Interpretation Webinar Handout 072116Document21 pagesMCMI IV Interpretation Webinar Handout 072116HUDA NAAZNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Rainfall Intensity For Southern Nigeria: S.O. Oyegoke, A. S. Adebanjo, E.O. Ajani, and J.T. JegedeDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Rainfall Intensity For Southern Nigeria: S.O. Oyegoke, A. S. Adebanjo, E.O. Ajani, and J.T. JegedeAdebanjo Adeshina SamuelNo ratings yet

- X32 Digital Mixer: User ManualDocument69 pagesX32 Digital Mixer: User ManualLuis FernandezNo ratings yet

- Cambodia of The Land Management and Administration Project (LMAP)Document19 pagesCambodia of The Land Management and Administration Project (LMAP)SaravornNo ratings yet

- Procesul de ReticulareDocument20 pagesProcesul de ReticulareMadalina CalcanNo ratings yet

- Prophet Hope Khoza - See in The SpiritDocument36 pagesProphet Hope Khoza - See in The SpiritMiguel SierraNo ratings yet

- Prelim Notes AccountingDocument63 pagesPrelim Notes AccountingKristine Camille GodinezNo ratings yet

- EstimationDocument106 pagesEstimationasdasdas asdasdasdsadsasddssa0% (1)

- Six Major Forces in The Broad EnvironmentDocument11 pagesSix Major Forces in The Broad EnvironmentRose Shenen Bagnate PeraroNo ratings yet

- Master Distributor Stock Components: Bulletin HY14-2700/USDocument72 pagesMaster Distributor Stock Components: Bulletin HY14-2700/USYuriPasenkoNo ratings yet

- 01-06-2202-13-40-GMC-Information Radiodiagnosis & ImagingDocument18 pages01-06-2202-13-40-GMC-Information Radiodiagnosis & ImagingSilent StalkerNo ratings yet

- Mangalagiri Proposed Landuse Map PDFDocument1 pageMangalagiri Proposed Landuse Map PDFGurpal kaurNo ratings yet

- Tranfer PF Anand PDFDocument2 pagesTranfer PF Anand PDFShubham ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- The Dilemma: Goodbye, Jimmy, Goodbye.: HIRE Verified WriterDocument9 pagesThe Dilemma: Goodbye, Jimmy, Goodbye.: HIRE Verified WriterBritney Anne H. PasionNo ratings yet

- The Giver Week 4 BookletDocument12 pagesThe Giver Week 4 Bookletapi-315186689No ratings yet

- Smo 3Document6 pagesSmo 3Irini BogiagesNo ratings yet

- MomDocument2 pagesMomSikkim MotorsNo ratings yet

- Le Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDocument8 pagesLe Conditionnel Présent: The Conditional PresentDeepika DevarajNo ratings yet

- Lesbian ActivismDocument243 pagesLesbian Activismepcferreira6512No ratings yet

- Hansatsu Exhibit Text OnlyDocument6 pagesHansatsu Exhibit Text OnlyosvarxNo ratings yet

- Shubhangi D. Mulik: Career ObjectiveDocument2 pagesShubhangi D. Mulik: Career ObjectiveShubhangiNo ratings yet

- Sistem Saraf Pusat (SSP) Dan Sistem Saraf Tepi (SST)Document37 pagesSistem Saraf Pusat (SSP) Dan Sistem Saraf Tepi (SST)Kris Canter Eka PutraNo ratings yet

- NET Lab ManualDocument32 pagesNET Lab ManualMadhu Sudan100% (1)

- Work-Life Balance Crafting During COVID-19Document21 pagesWork-Life Balance Crafting During COVID-19Sílvia PereiraNo ratings yet

- EuropassCV-NECHIFOR ENGLEZADocument4 pagesEuropassCV-NECHIFOR ENGLEZAcd13_nechifor1874No ratings yet

- Engineered Elastomeric Void Form: Product DescriptionDocument1 pageEngineered Elastomeric Void Form: Product DescriptionRajdip GhoshNo ratings yet

- The High Performance CompanyDocument6 pagesThe High Performance CompanyVinicius Bessa TerraNo ratings yet