Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

Uploaded by

Ivan GambusCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- WEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFDocument37 pagesWEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFdudcr100% (1)

- (Paolo Sacchi) Jewish Apocalyptic and Its HistoryDocument288 pages(Paolo Sacchi) Jewish Apocalyptic and Its HistoryDariob Bar100% (3)

- The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870From EverandThe Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870No ratings yet

- The History of Everyday Life - A Second Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesThe History of Everyday Life - A Second Chapter PDFIsabella VillarinhoNo ratings yet

- Explosive Child Prgram 2Document33 pagesExplosive Child Prgram 2ernestuksNo ratings yet

- A History of Political EconomyDocument157 pagesA History of Political EconomyFerran Moncho GonzálbezNo ratings yet

- Yefimov-Montenegrin Journal of EconomicsDocument46 pagesYefimov-Montenegrin Journal of EconomicsVladimir YefimovNo ratings yet

- Elmar Altvater & Juergen Hoffmann - The West German State Derivation Debate: The Relation Between Economy and Politics As A Problem of Marxist State TheoryDocument23 pagesElmar Altvater & Juergen Hoffmann - The West German State Derivation Debate: The Relation Between Economy and Politics As A Problem of Marxist State TheoryStipe ĆurkovićNo ratings yet

- 1994 Mises Institute AccomplishmentsDocument24 pages1994 Mises Institute AccomplishmentsMisesWasRightNo ratings yet

- Harris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.Document32 pagesHarris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.lcr89No ratings yet

- Hsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsDocument9 pagesHsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsGörkem AydınNo ratings yet

- Arndt - Economic DevelopmentDocument11 pagesArndt - Economic DevelopmentFranco Gabriel CerianiNo ratings yet

- Craufurd D. Goodwin History Os Economic ThoughtDocument15 pagesCraufurd D. Goodwin History Os Economic ThoughtMarcelino De Carvalho SantanaNo ratings yet

- Adam Smith ThesisDocument8 pagesAdam Smith Thesisjamieboydreno100% (2)

- Landreth and Colander C4 p76 93Document20 pagesLandreth and Colander C4 p76 93Louis NguyenNo ratings yet

- SmithDocument4 pagesSmithgoudouNo ratings yet

- A History of Political EconomyDocument298 pagesA History of Political EconomyhaffaNo ratings yet

- Criticism and Revision of Classical EconomicsDocument10 pagesCriticism and Revision of Classical EconomicsSeyala KhanNo ratings yet

- Gerber - Constitutionalizing The Economy - German Neo-Liberalism Competition Law and The 'New' EuropeDocument60 pagesGerber - Constitutionalizing The Economy - German Neo-Liberalism Competition Law and The 'New' EuropeAnonymous 3ugEsmL3No ratings yet

- CopleySutherland 1996Document4 pagesCopleySutherland 1996Isaac BlakeNo ratings yet

- The Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarFrom EverandThe Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarNo ratings yet

- ECON1401 JournalDocument3 pagesECON1401 JournalMarkNo ratings yet

- Leube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumDocument21 pagesLeube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumJumbo ZimmyNo ratings yet

- Saavedra DISS Activity2Document10 pagesSaavedra DISS Activity2Danielle SaavedraNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Free Trade ImperialismDocument260 pagesThe Rise of Free Trade ImperialismMadalina CalanceNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About History and Development of Economic AnalysisDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About History and Development of Economic AnalysisfionnaNo ratings yet

- Socialism and American Ideals by Myers, William Starr, 1877-1956Document28 pagesSocialism and American Ideals by Myers, William Starr, 1877-1956Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Working-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesFrom EverandWorking-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ECO 402new ClassicalsDocument27 pagesECO 402new ClassicalsEUTHEL JHON FINLACNo ratings yet

- Pertti Ahonen After The Expulsion West Germany andDocument3 pagesPertti Ahonen After The Expulsion West Germany andDragutin PapovićNo ratings yet

- Hall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)Document27 pagesHall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)rebenaqueNo ratings yet

- Southern Economic AssociationDocument18 pagesSouthern Economic AssociationSyahms T. ThesaurusNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 181.52.63.9 On Sun, 09 May 2021 23:52:50 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 181.52.63.9 On Sun, 09 May 2021 23:52:50 UTCMario Hidalgo VillotaNo ratings yet

- Workers and Capital Mario TrontiDocument34 pagesWorkers and Capital Mario Trontim_y_tanatusNo ratings yet

- 3.2.a-The Social Context of ScienceDocument23 pages3.2.a-The Social Context of Sciencejjamppong09No ratings yet

- Levine, D. & Carter, E. Miller, E. - 1976 - Simmel's Influence in American Sociology IDocument34 pagesLevine, D. & Carter, E. Miller, E. - 1976 - Simmel's Influence in American Sociology IJosé Manuel SalasNo ratings yet

- " The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Document8 pages" The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Amor Vinsent AquinoNo ratings yet

- Economic School of ThoughtsDocument13 pagesEconomic School of Thoughtspakhi rawatNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of The Early History of Economics in The United States 1St Edition Birsen Filip Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of The Early History of Economics in The United States 1St Edition Birsen Filip Online PDF All Chapterrickwray577711100% (4)

- Arnold S. NashDocument2 pagesArnold S. NashMarko MarkoniNo ratings yet

- Workers and CapitalDocument27 pagesWorkers and CapitaleqodmkNo ratings yet

- Heather Whiteside - Capitalist Political Economy - Thinkers and Theories-Routledge (2020)Document173 pagesHeather Whiteside - Capitalist Political Economy - Thinkers and Theories-Routledge (2020)Can ArmutcuNo ratings yet

- Writing The History of CapitalismDocument18 pagesWriting The History of CapitalismenlacesbostonNo ratings yet

- What Are Social Sciences?Document7 pagesWhat Are Social Sciences?Khawaja EshaNo ratings yet

- Academia Diplomatica Chile 2007 Economia Latinoamericana Idioma InglesDocument125 pagesAcademia Diplomatica Chile 2007 Economia Latinoamericana Idioma Inglesbelen_2026No ratings yet

- German Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918-1933From EverandGerman Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918-1933No ratings yet

- Biography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How ADocument4 pagesBiography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How AAlan AptonNo ratings yet

- Gordon, David - The Philosophical Origins of Austrian EconomicsDocument21 pagesGordon, David - The Philosophical Origins of Austrian EconomicsYork LuethjeNo ratings yet

- Elites in Latin America by Seymour Martin Lipset Aldo Solari - WhettenDocument3 pagesElites in Latin America by Seymour Martin Lipset Aldo Solari - WhettenTyss MorganNo ratings yet

- Strange CareerDocument22 pagesStrange Careervivek.vasanNo ratings yet

- Economists As Worldly Philosophers PreviewDocument10 pagesEconomists As Worldly Philosophers PreviewУрош ЉубојевNo ratings yet

- Richard Grassby - The Idea of Capitalism Before The Industrial RevolutionDocument77 pagesRichard Grassby - The Idea of Capitalism Before The Industrial RevolutionKeversson WilliamNo ratings yet

- Political Economy DefinedDocument26 pagesPolitical Economy DefinedDemsy Audu100% (1)

- McNally Political - Economy Rise - Of.capitalismDocument375 pagesMcNally Political - Economy Rise - Of.capitalismites76No ratings yet

- Staatstheorie and The New American Science of PoliticsDocument15 pagesStaatstheorie and The New American Science of PoliticsRaphael T. SprengerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1roanneiolaveNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Roboticist Masahiro Mori's Buddhist Inspired Concept of "The Uncanny Valley"Document12 pagesThe Japanese Roboticist Masahiro Mori's Buddhist Inspired Concept of "The Uncanny Valley"Linda StupartNo ratings yet

- Mantra For Enemies WealthDocument11 pagesMantra For Enemies WealthAnilkumarSharmaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Usol 2016-2017 PGDSTDocument20 pagesAssignment Usol 2016-2017 PGDSTpromilaNo ratings yet

- Lga 3101 PPG Module - Topic 4Document12 pagesLga 3101 PPG Module - Topic 4Anonymous HaMAMvB4No ratings yet

- The Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational Leadership Module 1-Week 2Document21 pagesThe Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational Leadership Module 1-Week 2Josephine Pangan100% (2)

- Holy Heroes Facilitators ManualDocument40 pagesHoly Heroes Facilitators ManualRev. Fr. Jessie Somosierra, Jr.No ratings yet

- People ODocument15 pagesPeople OAnonymous toQNN6XEHNo ratings yet

- What Is A SacramentDocument21 pagesWhat Is A SacramentSheila Marie Anor100% (1)

- The DOGME 95 Manifesto DIY Film ProductiDocument25 pagesThe DOGME 95 Manifesto DIY Film ProductiHaricleea NicolauNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Difference Between Argumentation and PersuasionDocument10 pagesUnderstanding The Difference Between Argumentation and PersuasionEVA MAE BONGHANOYNo ratings yet

- Patricia Benner Nursing Theorist2Document31 pagesPatricia Benner Nursing Theorist2api-216578352No ratings yet

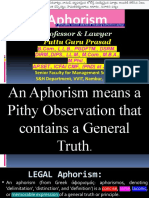

- Aphorism 1Document21 pagesAphorism 1PUTTU GURU PRASAD SENGUNTHA MUDALIARNo ratings yet

- Discourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysDocument2 pagesDiscourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysBadarNo ratings yet

- Paradox and OxymoronDocument5 pagesParadox and OxymoronPM Oroc100% (1)

- Attract Women Be Irresistible How To Effortlessly Attract Women and BecomDocument42 pagesAttract Women Be Irresistible How To Effortlessly Attract Women and Becommanhhung276894954No ratings yet

- Konstruksi Sosial Judi Togel Di Desa Padang Kecamatan Trucuk Kabupaten BojonegoroDocument1 pageKonstruksi Sosial Judi Togel Di Desa Padang Kecamatan Trucuk Kabupaten Bojonegorofandi akhmad jNo ratings yet

- Let's Get Started: Unit 2 LECTURE 6: Introduction To Hypothesis Testing, Type 1 & 2 ErrorsDocument17 pagesLet's Get Started: Unit 2 LECTURE 6: Introduction To Hypothesis Testing, Type 1 & 2 ErrorsVishal Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- A Gate OpensDocument26 pagesA Gate Opensstrgates34No ratings yet

- The Change CurveDocument2 pagesThe Change CurveTroy Healy100% (1)

- Cognitive TheoryDocument12 pagesCognitive TheoryhannaNo ratings yet

- 7 Mental Hacks To Be More Confident in Yourself PDFDocument4 pages7 Mental Hacks To Be More Confident in Yourself PDFSujithNo ratings yet

- Ethics - Part 3 by Spinoza, Benedictus De, 1632-1677Document49 pagesEthics - Part 3 by Spinoza, Benedictus De, 1632-1677Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Critique Paper On Social MediaDocument2 pagesCritique Paper On Social MediaAlex Mendoza100% (1)

- My Job: AIA Premier AcademyDocument60 pagesMy Job: AIA Premier AcademyShah Aia Takaful PlannerNo ratings yet

- Compare The Ways in Which Writers of Your Two Chosen Texts Present The Role of Gender in The MisuseDocument2 pagesCompare The Ways in Which Writers of Your Two Chosen Texts Present The Role of Gender in The MisusesamnasNo ratings yet

- Conflict Related CasesDocument31 pagesConflict Related CasesJZ SQNo ratings yet

- Sophie Stimpson Fine Fragrance Evaluator - Career - DownloadDocument2 pagesSophie Stimpson Fine Fragrance Evaluator - Career - DownloadBagus PrakasaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's The Physics NotesDocument3 pagesAristotle's The Physics NotesJocelyn SherylNo ratings yet

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

Uploaded by

Ivan GambusOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

2 DORFMAN. The Role of The German Historical School in American Economic Thought

Uploaded by

Ivan GambusCopyright:

Available Formats

American Economic Association

The Role of the German Historical School in American Economic Thought

Author(s): Joseph Dorfman

Source: The American Economic Review, Vol. 45, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Sixty-

seventh Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association (May, 1955), pp. 17-28

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1823538 .

Accessed: 18/01/2015 14:50

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

American Economic Review.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

THE ROLE OF THE GERMAN HISTORICAL SCHOOL

IN AMERICAN ECONOMIC THOUGHT

By JOSEPH DORFMAN

Columbia University

Just as Americaneconomic thought has affected developmentsabroad,

so have foreign streams left an impress on the American scene. The

British stream of ideas has been by far the dominant one. But then the

American cultural heritage is predominantly British. This is especially

true of the political and economic institutions-the basic conditioning

forces. To unfold the highly complicated story of the naturalization of

British economic thought on American soil would require much more

than one session. Let me restrict my address to a more manageable

foreign stream. Let me take the German Historical School which was

especially influential in the seventies and eighties. In the broad flow of

history, this movement was a contributory force to the renaissance in

American intellectual life that accompanied Amnerica'sgreat industrial

revolution in the post-Civil War era.

As they envisaged the promise of America's industrialization, en-

lightened men were anxious to avoid the ills that disfigured England's

factory and machine age and threatened the Anglo-Americantradition

of liberty. In an effort to cope with the pressing economic issues of the

new era, progressive-minded economists began to question the ade-

quacy of traditional, classical economic theory which dominated

America in a vulgarized form. They sought ways not only to explain

but also to fructify the economy and build up social wealth. They were

concerned,not only with analysis, but-in an incipient way of course-

with social engineering.

Technically the origins of the German Historical School go back

at least to the middle of the nineteenth century, but it received a strong

impetus fromnthe intellectual revolution symbolized by the name of

Darwin and the effort in all fields to assimilate the doctrine of evolu-

tion. So far as the Anglo-Americanworld is concerned, it was a move-

ment to do for economics what Sir Henry Maine did for English

jurisprudencein correcting the overanalytic emphasis of the dominant

Austinian School by an infusion of historical and comparativemethods.

This was not the old-fashioned history, hardly distinguishable from

belles-lettres but the new history that was concerned with detailed,

objective inquiry. It was in this atmosphere that the GermanHistorical

School makes its appearance in America.

17

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 AMERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

We may begin with a formal event. In 1877, the Trustees of Colum-

bia appointed the German-trainedRichmond Mayo-Smith to develop

economics on an inductive basis. They hoped he would follow in the

footsteps of Continental European pioneers who "brought together

... the ... information . . . gathered by the statistical bureaus of the

several governments, and have sought to infer . . . the system most

favorable to industrial development, to growth in national wealth

and to the fairest and most equal distribution of the rewards of labor."1

Here was the formal acceptance of the German Historical School in

the academic world.

The school-or more properly, members of the school-had come to

the attention of Americans in various ways. There were, of course, the

American students who had studied in Germany. Even before that

movement took on large proportions, there was knowledge of the school

through English and French periodicals which were widely read in the

United States. There was also the deep interest of some American

economists in statistics and therefore in the techniques developed by

the Germans.For example, as early as 1863, Samuel B. Ruggles, as the

official American delegate to the International Statistical Congress at

Berlin, expressed his conviction that "abstract theories and historical

traditions doubtless have their use and their proper place, but statistics

are the very eyes of the statesman, enabling him to survey and scan

with clear but comprehensive vision the whole structure and economy

of the body politic." A few years later, at the next Congress, Ruggles

met and was deeply impressed by Ernst Engel, head of the Royal Statis-

tical Bureau of Prussia and one of the most famous economists of

Europe. His Bureau was unique in that it included a "seminary"to train

university graduates who qualified for admission to the higher branches

of the civil service. In this way, governmentaloffices,like the Statistical

Bureau itself, would become laboratoriesof political science. Engel was

deeply interested in social problems. He visited England to study labor

conditions in the most advanced industrial nation. He was one of the

promoters of the organization of German economists in 1872-the

Union for Social Politics-that apparently first gave prominenceabroad

to the Historical School. The organization espoused social reform along

English precedents and was soon confronted by hostile critics, who

nicknamed the members Katheder-Sozialisten (Socialists of the Chair).

Rumors soon circulated abroad that the organization advocated social-

ism, supported breaking of labor contracts, and favored strikes.

The picture was obscured abroad by the general lack of knowledge

of German economics. To overcome this difficulty in England, the

1 Cited in Joseph Dorfman, "The Department of Economics," in A History of the Faculty

of Political Science of Columbia University (New York, 1955), pp. 170-171.

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTERNATIONAL FLOW OF ECONOMIC IDEAS 19

Fortnightly Review published an article in 1873, written by Professor

Gustav Cohn, on the state of German economics. Cohn pointed out

that the Union was influenced by the widespread revolt in the learned

community against the highly abstract reasoning of the eighteenth

century with its emphasis on natural rights, state of nature, laws of

nature. They insisted on the need to understand "the facts which pre-

ceded the modern state of society" before any reasonable conclusions

concerning the future could be drawn. These economists were, he con-

tinued, affected by the success of the inductive method in the natural

sciences and the progress of a philosophy which asserted the authority

of society and the organic character of the state against the workings of

extreme laissez faire.

Two years later, the same magazine published a review article that

set off a controversy in the United States over the German Historical

School. Wilhelm Roscher, the patriarch of the school, had just published

The History of GermanPolitical Economy. Professor T. E. Cliffe Leslie

of Queen's College, Belfast, in the review defended the school against

the charge of being socialistic. In this essay he said:

Man, in the eyes of the historical or realistic school, is not merely an "exchanging animal"

. with a single unvarying interest, removed from all the real conditions of time and

place-a personification of an abstraction; he is the actual . . . human being . . . history

and surrounding circumstances have made him, with all his wants, passions, and infirmities.

He pointed out the wide range of the publications by members of the

GermanHistorical School and insisted that:

A great diversity of opinion is to be found among the economists of this school . . .

some being conservative and others liberal in their politics; but no revolutionary or social-

ist schemes have emanated from its most advanced Liberal rank. Their principal practical

aims would excite little terror in England. Some legislation after the model of the English

Factory Laws, some system of arbitration for the adjustment of disputes about wages, and

the legalization of trade unions under certain conditions, are the main points in their prac-

tical program.

Leslie's essay attracted the attention of the Commercial& Financial

Chronicleof New York. In a eulogistic editorial it declared that the new

German school treated the forces that caused a nation to grow in

wealth. Interest in the school was stimulated by another eulogy which

appearedat the same time in a French organ, Revue des Deux Mondes.

The article was written by the eminent Belgian economist, Smile de

Laveleye. He fanned the flames of controversy by contending that the

erroneous belief in natural laws strengthened the opposition to bi-

metallism and protectionism, both of which, he argued, were essential

to business prosperity.

This brought the Nation into the arena, a journal which exercised

the greatest influence on respectable opinion. The editor, E. L. Godkin,

was a firm adherent to the creed of free trade and the gold standard.He

wrote an editorial asserting that the new group of German economists

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 AMERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

were erudite university teachers with little public experience and long

accustomed to accepting militarism and bureaucracy. In fact, they were

socialists. Immediately the Nation received protests from several of its

prominent readers.

One defender of the school was W. F. Allen, of the University of

Wisconsin, who had studied in Germany.He was an orthodox Ricardian

in his foundations. He strongly opposed, however, the extreme laissez

faire of the dominant economics. It is all very well, he said, to point

out the socialistic tendencies and the disastrous effect of public poor

relief, for example, but after all was it proper for the state to "suffer

its citizens to die of starvation in open day"? ("Fawcett's Essays,"

in the Nation, September 25, 1872, page 204.) He was, therefore, in

sympathy with a school which he felt accepted the foundation laid by

Adam Smith but built a new structure on it.

The Nation conceded that the Germaneconomists were not socialists

but insisted that they had been blinded by resentment against the in-

cidental, wild speculation of the prosperous era, which unification had

brought to Germany.

The following year the controversy was intensified by the attack of

the French economist, Maurice Block, which appeared in translation

in the Penn Monthly. In the name of the "scientific school," he de-

nounced the GermanHistorical School and Leslie as "empirics"seeking

to substitute sentiment for principle and holding that "the state . . .

should conduct everything, direct everything, decide everything." Leslie

asked the Penn Monthly to reprint a small extract from his article, "On

the Philosophical Method of Political Economy," which would show

that far from being an opponent of the philosophical spirit, as Block

had claimed, his object had been to explain what the philosophical

method ought to be. The journal decided to reprint the essay in full,

because "it . . . represents a real advance in the development of eco-

nomic science."

In 1878, with the aid of Allen, John J. Lalor, a sound money and

free trade journalist, brought out the English translation of Roscher's

famous Principles. This was immediately attacked by William Graham

Sumner, who presented the view of dominant orthodoxy. Sumner

stated that the work was distinguished by its pervasive faith in the

state. History and statistics could not be merged with "dogmatic eco-

nomics" but were separate disciplines.

Nevertheless, interest in the school continued to grow. John Kells

Ingram, of Trinity College, Dublin, gave an important address before

the British Association for the Advancementof Science in 1878. Ingram

condemnedthe extremely abstract method of current English economics

and declared that the study of the economic phenomena of society

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTE RNATIONAL FLOW OF ECONOMIC IDEAS 21

should, in accordancewith the historical method, be systematically com-

bined with that of the other aspects of social existence. He pointed out

that the essentials of the method were presented by the Secretary of the

Union for Social Politics. Adolf Held, a student of Engel, had published

elaborate inductive studies in taxation. He warned against too abstract

theorizing on tax incidence and against overestimating the income tax

as the sole means of reaching the entire taxable capacity. At the

moment, Held was attempting to meet the challenge of socialism by

supporting an advanced program of social security that culminated in

Bismarck's legislation of sickness, accident, invalidity, and old age

insurance. Ingram presented Held's standpoint in his own words:

1. The new school . . . opposes. . . the view . . . that the productionand acquisitionof

wealth by individualsis the single . .. object of humanlife; wealth, it regardsas a means

used by Humanity in its struggletowards moral ideas of life, and for the furtheranceof

universalculture

2. It . . . seeks to understandpresent economicphenomenathrough the study of their

historicaldevelopment,and to ascertainthem as accuratelyas possible through statistical

investigations.It uses the knowledge of the nature of man's intellect and will for the

rationalexplanationof economicfacts, but does not constructthose facts themselvesout of

one-sidedassumptionsrespectingthe natureof man.

3. It . . . recognizesthe right of the state to positive interventionin the economicrela-

tions of the community,for the supportof the weak and the strengtheningof publicspirit.

As the Political Economy of the last century applied itself chiefly to the liberationof the

economicforces from antiquatedand uselessrestrictions,so the new school speciallymeets

the acknowledgedneed of new social arrangements,the need of social reformin opposition

to social revolution on the one hand and to rigid laissez-faireon the other.

4. It takes up, therefore, a less isolated position in relation to the other Moral and

PoliticalSciences.

In a quiet way the school had already struck root. Already in 1875,

Colonel Carroll D. Wright, chief of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statis-

tics of Labor, had introduced Engel's law of consumption. He drew

upon Engel's studies to make a comparison of the condition of the

workmen in Massachusetts with that in other states and foreign coun-

tries. Wright went a step beyond Engel and concluded also "that the

higher the income . . . the greater the saving, absolutely and propor-

tionately." Thanks to Wright, the study of family budgets was de-

veloped which, whether in the form of "Engel tables" or "Engel curves"

has become so pivotal in economic analysis in our day. Engel also

influencedWright's fundamentalwork on the structure for a price index

which has provided the statistical substance for many far-reaching

decisions, such as adjustment of wages to cost of living. Inspired by

Engel's success in training statisticians, WVrightsuccessfully promoted

among American colleges the establishment of courses in statistics.

The German influences were summed up by Wright himself. The

new school, he exclaimed, "bids fair to include on its roll of pupils

the men in all civilized lands who seek by legitimate means, and with-

out revolution, the amelioration of unfavorable industrial and social

relations." (The Relation of Political Economy to the Labor Question

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22 AMERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

[1882], page 13.) The rigidly orthodox promptly castigated Wright

as being infected by the socialists of the chair who stress moral forces

and ignore the primitive and more elementary force of self-interest.

Wright, however, continued to plead for sociAl reform, in terms of the

idiom of the Historical School. Thus, while the United States Com-

missioner of Labor in 1893, he described the German social legislation

as a brave attempt to reduce economic insecurity.

Equally receptive to the school was a scholar who was to become

the country's foremost economist and statistician, General Francis A.

Walker. He insisted that the classical economics, as formulatedby John

Elliot Cairnes, furnished the skeleton foundation for sound economics,

but he questioned the wage-fund doctrine and supported international

bimetallism. Walker castigated the reigning orthodox economics for its

extreme conservatism. He observed their neglect of historical methods,

and their overemphasis upon an a priori method which achieved a

simplicity in classification to which the subject matter was not suscepti-

ble. These factors, he said, in 1879 had cost the science of economics

public regard, especially among the laboring classes. As a remedy for

this, the Historical School, it seemed to him, offered the greatest prom-

ise. "The economists of Germany, Italy, Belgium, and France," he

wrote, "are doing the work which Adam Smith began, in his spirit, but

with larger opportunities and a wider and ever widening view."2

The movement reached a high pitch in the eighties, especially under

the impact of English writings, that opened up the field of economic

history. Indicative of the temper of the times was the fact that the

article on "Political Economy," in the ninth edition of the Encyclo-

paedia Brittanica (1885), was prepared by Ingram; and the En-

cyclopaedia, of course, was an authority here as well as in England.

The essay was quickly reprinted here for use in college classes, largely

through the efforts of F. W. Taussig.

The Historical School was scoring, again because an ever increasing

number of college graduates were going to Germany for advanced work

in the seventies and eighties. Germany had long been known as the

land of scholarship, a land where, it was said, professors achieved a

"degree of perfection . . . that astonishes the world." (F. W. Taussig,

"College Graduates in Germany," in the Nation, April 2, 1885, page

275.) And it was pointed out in 1876 by Charles F. Dunbar, of

Harvard, that the lead in economics had now passed from England and

France to Germany.

The young men who went to Germany were imbued with a lively

2Walker, "The Present Standing of Political Econonmy," 1879; reprinted in Walker, Dis-

cussions in Economics and Statistics, Vol. I, edited by D. R. Dewey (New York, 1899),

p. 318.

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTERNATIONAL FLOW OF ECONOMIC IDEAS 23

interest in statistics. A number who studied with Engel and his assist-

ant, August Meitzen, at the Royal Statistical Bureau, achieved con-

siderableprominence.Henry CarterAdams became the first statistician

of the Interstate Commerce Commission and devised its pivotal

accounting system which served as a model for the regulation of public

utilities here and throughout the world. Roland P. Falkner was the

first man to hold a leading American university post devoted exclu-

sively to statistics, at the Wharton School of the University of Penn-

sylvania. He prepared the translation of Meitzen's History, Theory,

and Technique of Statistics. His work on the famous Aldrich Report of

1893, Wholesale Prices, Wages and Transportation, was one of the

landmarks in statistical investigation. Richmond Mayo-Smith became

the outstanding teacher in statistics, and turned out such students as

WAalter F. Willcox and the inventor of the electrical tabulating machine,

Herman Hollerith.

Another area which left a definite impress on American students

was the systematic treatment of public finance or, as the Germanscalled

it, the "Science of Finance," a subject which the English had neglected

as comparativelyunimportant.Interestingly, in line with this emphasis,

the American pioneers in the field followed a German precedent in

substituting the term economics for political economy, as the more com-

prehensive term. Political economy was restricted to private finance,

or the domain of voluntary association. The term public finance covered

the "wants of the state and the means by which they are supplied."

Political economy and the science of finance became branches of eco-

nomics. (See Joseph Dorfman, "Henry Carter Adams: Harmonizer of

Liberty and Reform," introductory essay in Adams, Relation of the

State to Industrial Action and Economics and Jurisprudence [New

York, 1954], page 13.)

Students were also impressed by the scope of national economy

covered in the massive works of such leaders as Roscher and Adolph

Wagner. For example, comprehensive instruction was given, not only

in principles, but also in agriculture (including forestry), transporta-

tion, commerce, manufactures, and finance. It was under this impact

that Adams urged the need for a course on "AmericanTechnics" which

would comprise the contributions of agriculture, manufacturing, and

transportation.

To clarify the nature of the influence of the German Historical

School, let me discuss specifically five German-trainedeconomists who

were the leading promoters and the first officers (along with Walker)

of that landmark in the development of economic thought in America,

the American Economic Association.

J. B. Clark (in "Unrecognized Forces in Political Economy," the

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24 AMERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

New Englander, October, 1877, page 712) warned that the assumed

man of orthodoxy "is too mechanical and too selfish to correspondwith

the reality; he is actuated altogether too little by higher psychological

forces."

E. J. James was more positive. He attracted attention through his

contributions to the authoritative Cyclopaedia of Political Science,

Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States

(1883-84). His articles ranged from the "History of Political Econ-

omy" and "Finance" to "Banks of Issue" and "Factory Laws." In the

spirit of his German training, he declared that factory legislation could

be justified, not only as protection for the helpless, but as an essential

movement in the interest of society. To quote: "A state has other and

nobler ends to follow than the accumulationof mere material wealth....

Moderate wealth and happy homes are better than a degradedproletary

and ability to underbid all competitors in the industrial world."

Richard T. Ely was the most provocative of the group. He had not

only studied in Germany but found it desirable to spend there a good

part of each of the three years, 1911-13, in order to complete his most

substantial book, Property and Contract. On his return in 1880 from

his first trip to Germany he found academic openings scarce. Forced

"to wander about the streets of New York . . . in a most wretched

desperate state," he vowed to "use every opportunity to benefit those

who suffer."3After a year and a half he obtained a foothold at Johns

Hopkins. To aid in devising the best methods of carrying out proposed

reforms and executing the laws, he lectured on the "Principles and

Practices of Administration with Special Reference to Civil Service

Problems and Municipal Reform." City planning, the mother of modern

planning, likewise owes much to Ely. He was deeply impressed with

the efficient administrationof German cities by a permanent civil serv-

ice which included the highest officials. A considerable advantage of a

civil service, he wrote in 1880, was the permanence and steadiness of

policy. Plans could be laid for a number of years and carried out grad-

ually as a city could afford to execute them.

While still fresh at Johns Hopkins, he published widely read studies

on the "new political economy." He granted that the older political

economy had considerable merit. It separated wealth from the other

social phenomena for special study. It showed the impossibility of

understanding society without investigating the processes of the pro-

duction and distribution of goods. In serving to pull down outworn

institutions, it answered satisfactorily the needs of the latter part of

the eighteenth century and the early part of the nineteenth century, but

' Ely to Labadie, August 14, 1885, in "The Ely-Labadie Letters," edited by Sidney Fine,

Michigan History, March, 1952, p. 17.

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTERNATIONAL FLOW OF ECONOMIC IDEAS 25

like the French Revolution it was negative. Not least among the merits

of the new view, Ely said, was that it gave a more concrete interpreta-

tion of economic history, by attempting to understand past doctrines in

the light of their environment. He especially commended Wagner for

his statement of the three ethical principles underlying economic policy.

The first was the principle of individualism. This was modified by the

social principle which acted through the state. Finally, there was the

"caritative" principle-the principle of brotherly love expressed in

voluntary action on behalf of others. Charity was only one form. The

principle softened the rigors of life in ways that the social principle

could not, for it was not obliged to operate according to fixed rules. Ely

also noted Wagner's program for comprehensive social security that

would eventually include protection against unemploymentduring hard

times. Ely's emphasis, as early as 1882, on the acceptance of German

social legislation, was prophetic. "It behooves . . . Americans to follow

diligently the course of these experiments," he stated, "for we may be

sure the same social problems which now vex Germany, will one day

confront us." ("Bismarck's Plan for Insuring GermanLaborers,"in the

InternationalReview, May, 1882, page 526.) To this end, he, along with

Henry Farnam, later promoted the American Association for Labor

Legislation.

Ely also pointed out that government regulation of industry provided

the means of effectively applying the inductive method, for the legisla-

tion necessitated the systematic gathering and classification of data.

He got John R. Commons and other students to prepare the famous

IIistory of Labour in the United States. In his widely used Introduction

to Political Economy, Ely not only presented Engel's law, but called

attention to Engel's basic objective "that it might be possible by a

careful study of a sufficient number of family budgets for a period of

years to construct a sort of social signal service"; in other words, "that

changes in total expenditures and in expenditures for various items in

a sufficient number of typical families could enable one to predict the

coming of industrial storms."

Henry Carter Adams, though he found the Germany of Bismarck's

day an example of efficiency and enlightened reform, warned against

the dangers to liberty implicit in indiscriminate state intervention. He

admired the German methods of study and their skill at systematiza-

tion, but he was disturbed by their worship of the state. This lay at the

heart of his warning, in speaking of German university training. "It

is not possible," said Adams, "for an instructorwhose lectures are worth

the hearing to separate himself from the peculiar influence of his time

and immediate environment,and in Germany especially do the lectures

one hears upon political sciences reflect the bias of German local and

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26 AMERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

national policy." ("Political Science in German Universities," in the

Michigan Alumnnus,January, 1899, pages 137-138.) On the other hand,

Adams was also disturbed by the workings of unrestrained private

enterprise in America, which in another century, he felt, would con-

tradict the theory of freedom and destroy the government. "From this

dilemma must arise," he said, "an American Political Economy-an

Economy which is to be legal rather than industrial in its character."

("The Position of Socialism in the Historical Development of Political

Economy," in Penn Monzthly,April, 1879, page 294.) In this he was

deeply imjpressed,as he wrote in 1878, with Wagner's view that the

tendency in economic study was towards jurisprudence.

Adams noted the need for forest conservation, and he pointed out

that corporations could not undertake such a task because the fruits

of the investment were too remote. In the famous monograph, Rela-

tion of the State to Industrial Action, he declared that there were two

important functions that the governmentcould perform in the industrial

area. First, the state could raise the ethical plane of competition. For

example, factory legislation need not curtail competition, but it could

remove serious abuses in the factory without eliminating the benefits

of individual action. Second, the state may realize for the public good

the benefits of monopoly. For this purpose, Adams developed the prin-

ciple of "increasingreturns" to cover industries which lend themselves

to public control; for example, the railroads.

Government control, Adams argued, would not necessarily lead to

corruption. Corruption was due to the lack of correlation between the

public and private functions. The inducements offered in the two varied

widely. Extension of the state's functions, manned by a well-paid civil

service, would restore the harmony between state and private service,

for it would bring social distinction, the chance to exercise one's talents,

and the pleasure of filling well a responsible position.

Factory legislation and monopoly regulation, however, did not touch

the problem of the rights and duties under which work is done. This

brought Adams, in 1886, to the need of building up a common law of

labor relations, through collective bargaining.

Explicitly building on Held, Adams contended that in the scheme of

petty industry, the regime of tools, the ordinary rights of personal free-

dom, secured to men an enjoyment of the fruits of their labor. In the

great industries of today, however, the laborer was dependent upon the

owner of machines, of materials, and of places for the opportunity to

work. It followed that laborers must unite or they would surely get the

worst of any bargain. Underlying labor's demands was the "idea" that

the laborers had some right of proprietorshipin the industry to which

they gave their skill and time. Thus collective bargaining and the labor

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

INTERNATIONAL FLOW OF ECONOMIC IDEAS 27

contract envisaged a crystallization of a common law of labor rights

which was in full harmony with the development of Anglo-Saxon li-

berty.

Finally, E. R. A. Seligman did much to clarify the objectives of the

Historical School. He said, in 1883, that the difference between the

orthodox school and the modern German school was not between de-

ductive and historical methods. The exclusive use of either led to

absurdities, producing an unreal science or a body of archeological

facts. A judicious combination of both was the only permissible pro-

cedure. The chief point of difference was that the orthodox had an

atomistic, individualistic point of view; the other had a social stand-

point. The orthodox posited the universal spirit of self-interest; the

other stressed the "multiplicity of motives which cannot be jumbled

together in the phrase, 'desire for wealth."' It emphasized, also, the im-

portance of legal systems and historical causes and the close connection

between ethics and economics as sister moral sciences. Seligman felt

that only extremists would deny any value to the views of those on the

other side. He called attention, however, to the "practical use to which

the bald, unqualified, and therefore untrue theories" have been put in

late years. For example, the so-called "scientific socialism" of Lassalle

and Marx was the "logical conclusion from the premise that labor is

the cause of all value, and many of Mr. Henry George's wild fallacies

are traceable to an almost superstitious acceptance of the Ricardian

law of rent." The state, concluded Seligman, had a duty to interfere

where free competition ends disastrously, and "where the powers of

state themselves are threatened . . . by corporate monopolies." ("Sidg-

wick on Political Economy," the Inzdex,August 16, 1883, pages 75-76.)

Despite the numerous attacks on it, the "new school" had made its

way. In the seventies and eighties, it furnished a rationale for com-

bating the arrogant individualism of the time. Its emphasis on history

and statistics was a powerful force in developing these mighty instru-

ments for the expansion of economics. Its impact is epitomized in the

statement of principles of the American Economic Association on its

formation in 1885:

1. We regardthe state as an agency whose positive assistanceis one of the indispensable

conditionsof humanprogress.

2. We believe that political economyas a scienceis still in an early stage of its develop-

ment. While we appreciatethe work of former economists,we look not as much to

speculationas to the historicaland statisticalstudy of actual conditionsof economic

life, for the satisfactoryaccomplishmentof that development.

3. We hold that the conflict of labor and capital has brought into prominencea vast

numberof social problems,whose solution requiresthe united effort, each in its own

sphere,of the church,of the state, and of science.

4. In the study of the industrial and commercialpolicy of governmentswe take no

partisan attitude. We believe in a progressivedevelopmentof economic conditions,

which must be met by a correspondingdevelopmentof legislativepolicy.

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28 AMlERICAN ECONOMIC ASSOCIATION

Having given so mnuchi, let us take somnethingaway. The staterment

of principles was in a few years dropped. For a while there occurred

an overwhelming emphasis on the doctrine of marginal utility as the

key to all economic analysis. Interestingly, the German-trained con-

tingent was the first to welcome Jevons' theory as a part of the new

economics (Clark attributed his own version of marginal utility to the

inspiration of his German teacher, Karl Knies), but they had hardly

intended that economics should be restricted to this doctrine, a develop-

ment which was accelerated by the popularity of the translations of

the nonmathematical,"Austrian"works. The creation of chairs of eco-

nomic history, sociology, and social ethics tended to remove from

economics the issues that had made the Historical School a vital force,

especially the concern with the moral problems presented by industrial

changes.

We are ready to sum up. From the beginning, the Americans followed

the German Historical School in a discriminating fashion. They dis-

tinguished between its methods and its political philosophy. The first

they adopted with enthusiasm, and made it an enduring feature of

American economic thought. They diversified their scientific study.

They developed new realms of interest, such as public finance, rail-

roads, agriculture, labor, and the history and significance of technologi-

cal and legal relations. They kept alive a serious interest in the systema-

tic treatment of "commercial crises." They enriched economics with

historical and sociological material. It became difficult henceforth to

discuss even the most abstract doctrines without reference to statistics,

history, and environment. Yet Americans adapted the attitudes of the

German Historical School to their own traditions. For the Germans,

the organic character of society was reduced to a question of action by

a centralized and almost dictatorial state authority. This is not what

organism meant to the Anglo-American mind. The national state was

not the only embodimentof society. In the United States, particularly,

there was a multitude of state and local authorities. There were, in

addition, entities of a social or economic sort that exercised organic

functions. In the new doctrine, therefore, as transformedby the Anglo-

American mentality, doctrinaire individualism was modified or cor-

rected by the encouragement of the powers and functions of a great

many aggregates. This spelled the fundamental distinction in political

outlook between the Historical School in its native land and its Amer-

ican heirs.

This content downloaded from 200.130.19.150 on Sun, 18 Jan 2015 14:50:41 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- WEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFDocument37 pagesWEHLER, Hans-Ulrich - Bismarck's Imperialism 1862-1890 PDFdudcr100% (1)

- (Paolo Sacchi) Jewish Apocalyptic and Its HistoryDocument288 pages(Paolo Sacchi) Jewish Apocalyptic and Its HistoryDariob Bar100% (3)

- The Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870From EverandThe Divided Path: The German Influence on Social Reform in France After 1870No ratings yet

- The History of Everyday Life - A Second Chapter PDFDocument22 pagesThe History of Everyday Life - A Second Chapter PDFIsabella VillarinhoNo ratings yet

- Explosive Child Prgram 2Document33 pagesExplosive Child Prgram 2ernestuksNo ratings yet

- A History of Political EconomyDocument157 pagesA History of Political EconomyFerran Moncho GonzálbezNo ratings yet

- Yefimov-Montenegrin Journal of EconomicsDocument46 pagesYefimov-Montenegrin Journal of EconomicsVladimir YefimovNo ratings yet

- Elmar Altvater & Juergen Hoffmann - The West German State Derivation Debate: The Relation Between Economy and Politics As A Problem of Marxist State TheoryDocument23 pagesElmar Altvater & Juergen Hoffmann - The West German State Derivation Debate: The Relation Between Economy and Politics As A Problem of Marxist State TheoryStipe ĆurkovićNo ratings yet

- 1994 Mises Institute AccomplishmentsDocument24 pages1994 Mises Institute AccomplishmentsMisesWasRightNo ratings yet

- Harris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.Document32 pagesHarris, A. L. (1942) - Sombart and German (National) Socialism. The Journal of Political Economy, 805-835.lcr89No ratings yet

- Hsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsDocument9 pagesHsitory of Thoughts Historical Critics of Neoclassical EconomicsGörkem AydınNo ratings yet

- Arndt - Economic DevelopmentDocument11 pagesArndt - Economic DevelopmentFranco Gabriel CerianiNo ratings yet

- Craufurd D. Goodwin History Os Economic ThoughtDocument15 pagesCraufurd D. Goodwin History Os Economic ThoughtMarcelino De Carvalho SantanaNo ratings yet

- Adam Smith ThesisDocument8 pagesAdam Smith Thesisjamieboydreno100% (2)

- Landreth and Colander C4 p76 93Document20 pagesLandreth and Colander C4 p76 93Louis NguyenNo ratings yet

- SmithDocument4 pagesSmithgoudouNo ratings yet

- A History of Political EconomyDocument298 pagesA History of Political EconomyhaffaNo ratings yet

- Criticism and Revision of Classical EconomicsDocument10 pagesCriticism and Revision of Classical EconomicsSeyala KhanNo ratings yet

- Gerber - Constitutionalizing The Economy - German Neo-Liberalism Competition Law and The 'New' EuropeDocument60 pagesGerber - Constitutionalizing The Economy - German Neo-Liberalism Competition Law and The 'New' EuropeAnonymous 3ugEsmL3No ratings yet

- CopleySutherland 1996Document4 pagesCopleySutherland 1996Isaac BlakeNo ratings yet

- The Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarFrom EverandThe Visionary Realism of German Economics: From the Thirty Years' War to the Cold WarNo ratings yet

- ECON1401 JournalDocument3 pagesECON1401 JournalMarkNo ratings yet

- Leube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumDocument21 pagesLeube 2002 - On Menger, Austrian Economics, and The Use of General EquilibriumJumbo ZimmyNo ratings yet

- Saavedra DISS Activity2Document10 pagesSaavedra DISS Activity2Danielle SaavedraNo ratings yet

- The Rise of Free Trade ImperialismDocument260 pagesThe Rise of Free Trade ImperialismMadalina CalanceNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About History and Development of Economic AnalysisDocument5 pagesResearch Paper About History and Development of Economic AnalysisfionnaNo ratings yet

- Socialism and American Ideals by Myers, William Starr, 1877-1956Document28 pagesSocialism and American Ideals by Myers, William Starr, 1877-1956Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Working-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesFrom EverandWorking-Class Formation: Ninteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United StatesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- ECO 402new ClassicalsDocument27 pagesECO 402new ClassicalsEUTHEL JHON FINLACNo ratings yet

- Pertti Ahonen After The Expulsion West Germany andDocument3 pagesPertti Ahonen After The Expulsion West Germany andDragutin PapovićNo ratings yet

- Hall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)Document27 pagesHall, Peter-Dilemmas Social Scence (Draft)rebenaqueNo ratings yet

- Southern Economic AssociationDocument18 pagesSouthern Economic AssociationSyahms T. ThesaurusNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 181.52.63.9 On Sun, 09 May 2021 23:52:50 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 181.52.63.9 On Sun, 09 May 2021 23:52:50 UTCMario Hidalgo VillotaNo ratings yet

- Workers and Capital Mario TrontiDocument34 pagesWorkers and Capital Mario Trontim_y_tanatusNo ratings yet

- 3.2.a-The Social Context of ScienceDocument23 pages3.2.a-The Social Context of Sciencejjamppong09No ratings yet

- Levine, D. & Carter, E. Miller, E. - 1976 - Simmel's Influence in American Sociology IDocument34 pagesLevine, D. & Carter, E. Miller, E. - 1976 - Simmel's Influence in American Sociology IJosé Manuel SalasNo ratings yet

- " The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Document8 pages" The Great Thinkers": ADAM SMITH (1723-1790)Amor Vinsent AquinoNo ratings yet

- Economic School of ThoughtsDocument13 pagesEconomic School of Thoughtspakhi rawatNo ratings yet

- Full Ebook of The Early History of Economics in The United States 1St Edition Birsen Filip Online PDF All ChapterDocument69 pagesFull Ebook of The Early History of Economics in The United States 1St Edition Birsen Filip Online PDF All Chapterrickwray577711100% (4)

- Arnold S. NashDocument2 pagesArnold S. NashMarko MarkoniNo ratings yet

- Workers and CapitalDocument27 pagesWorkers and CapitaleqodmkNo ratings yet

- Heather Whiteside - Capitalist Political Economy - Thinkers and Theories-Routledge (2020)Document173 pagesHeather Whiteside - Capitalist Political Economy - Thinkers and Theories-Routledge (2020)Can ArmutcuNo ratings yet

- Writing The History of CapitalismDocument18 pagesWriting The History of CapitalismenlacesbostonNo ratings yet

- What Are Social Sciences?Document7 pagesWhat Are Social Sciences?Khawaja EshaNo ratings yet

- Academia Diplomatica Chile 2007 Economia Latinoamericana Idioma InglesDocument125 pagesAcademia Diplomatica Chile 2007 Economia Latinoamericana Idioma Inglesbelen_2026No ratings yet

- German Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918-1933From EverandGerman Liberalism and the Dissolution of the Weimar Party System, 1918-1933No ratings yet

- Biography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How ADocument4 pagesBiography: Nations, Perhaps The Most Influential Work Ever Written About Capitalism. Smith Explained How AAlan AptonNo ratings yet

- Gordon, David - The Philosophical Origins of Austrian EconomicsDocument21 pagesGordon, David - The Philosophical Origins of Austrian EconomicsYork LuethjeNo ratings yet

- Elites in Latin America by Seymour Martin Lipset Aldo Solari - WhettenDocument3 pagesElites in Latin America by Seymour Martin Lipset Aldo Solari - WhettenTyss MorganNo ratings yet

- Strange CareerDocument22 pagesStrange Careervivek.vasanNo ratings yet

- Economists As Worldly Philosophers PreviewDocument10 pagesEconomists As Worldly Philosophers PreviewУрош ЉубојевNo ratings yet

- Richard Grassby - The Idea of Capitalism Before The Industrial RevolutionDocument77 pagesRichard Grassby - The Idea of Capitalism Before The Industrial RevolutionKeversson WilliamNo ratings yet

- Political Economy DefinedDocument26 pagesPolitical Economy DefinedDemsy Audu100% (1)

- McNally Political - Economy Rise - Of.capitalismDocument375 pagesMcNally Political - Economy Rise - Of.capitalismites76No ratings yet

- Staatstheorie and The New American Science of PoliticsDocument15 pagesStaatstheorie and The New American Science of PoliticsRaphael T. SprengerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document13 pagesChapter 1roanneiolaveNo ratings yet

- The Japanese Roboticist Masahiro Mori's Buddhist Inspired Concept of "The Uncanny Valley"Document12 pagesThe Japanese Roboticist Masahiro Mori's Buddhist Inspired Concept of "The Uncanny Valley"Linda StupartNo ratings yet

- Mantra For Enemies WealthDocument11 pagesMantra For Enemies WealthAnilkumarSharmaNo ratings yet

- Assignment Usol 2016-2017 PGDSTDocument20 pagesAssignment Usol 2016-2017 PGDSTpromilaNo ratings yet

- Lga 3101 PPG Module - Topic 4Document12 pagesLga 3101 PPG Module - Topic 4Anonymous HaMAMvB4No ratings yet

- The Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational Leadership Module 1-Week 2Document21 pagesThe Teacher and The Community, School Culture and Organizational Leadership Module 1-Week 2Josephine Pangan100% (2)

- Holy Heroes Facilitators ManualDocument40 pagesHoly Heroes Facilitators ManualRev. Fr. Jessie Somosierra, Jr.No ratings yet

- People ODocument15 pagesPeople OAnonymous toQNN6XEHNo ratings yet

- What Is A SacramentDocument21 pagesWhat Is A SacramentSheila Marie Anor100% (1)

- The DOGME 95 Manifesto DIY Film ProductiDocument25 pagesThe DOGME 95 Manifesto DIY Film ProductiHaricleea NicolauNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Difference Between Argumentation and PersuasionDocument10 pagesUnderstanding The Difference Between Argumentation and PersuasionEVA MAE BONGHANOYNo ratings yet

- Patricia Benner Nursing Theorist2Document31 pagesPatricia Benner Nursing Theorist2api-216578352No ratings yet

- Aphorism 1Document21 pagesAphorism 1PUTTU GURU PRASAD SENGUNTHA MUDALIARNo ratings yet

- Discourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysDocument2 pagesDiscourse Analysis DA and Content AnalysBadarNo ratings yet

- Paradox and OxymoronDocument5 pagesParadox and OxymoronPM Oroc100% (1)

- Attract Women Be Irresistible How To Effortlessly Attract Women and BecomDocument42 pagesAttract Women Be Irresistible How To Effortlessly Attract Women and Becommanhhung276894954No ratings yet

- Konstruksi Sosial Judi Togel Di Desa Padang Kecamatan Trucuk Kabupaten BojonegoroDocument1 pageKonstruksi Sosial Judi Togel Di Desa Padang Kecamatan Trucuk Kabupaten Bojonegorofandi akhmad jNo ratings yet

- Let's Get Started: Unit 2 LECTURE 6: Introduction To Hypothesis Testing, Type 1 & 2 ErrorsDocument17 pagesLet's Get Started: Unit 2 LECTURE 6: Introduction To Hypothesis Testing, Type 1 & 2 ErrorsVishal Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- A Gate OpensDocument26 pagesA Gate Opensstrgates34No ratings yet

- The Change CurveDocument2 pagesThe Change CurveTroy Healy100% (1)

- Cognitive TheoryDocument12 pagesCognitive TheoryhannaNo ratings yet

- 7 Mental Hacks To Be More Confident in Yourself PDFDocument4 pages7 Mental Hacks To Be More Confident in Yourself PDFSujithNo ratings yet

- Ethics - Part 3 by Spinoza, Benedictus De, 1632-1677Document49 pagesEthics - Part 3 by Spinoza, Benedictus De, 1632-1677Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Critique Paper On Social MediaDocument2 pagesCritique Paper On Social MediaAlex Mendoza100% (1)

- My Job: AIA Premier AcademyDocument60 pagesMy Job: AIA Premier AcademyShah Aia Takaful PlannerNo ratings yet

- Compare The Ways in Which Writers of Your Two Chosen Texts Present The Role of Gender in The MisuseDocument2 pagesCompare The Ways in Which Writers of Your Two Chosen Texts Present The Role of Gender in The MisusesamnasNo ratings yet

- Conflict Related CasesDocument31 pagesConflict Related CasesJZ SQNo ratings yet

- Sophie Stimpson Fine Fragrance Evaluator - Career - DownloadDocument2 pagesSophie Stimpson Fine Fragrance Evaluator - Career - DownloadBagus PrakasaNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's The Physics NotesDocument3 pagesAristotle's The Physics NotesJocelyn SherylNo ratings yet