Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Behavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent Adolescents

Behavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent Adolescents

Uploaded by

You YouOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Behavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent Adolescents

Behavioral Sciences Hispanic Journal Of: Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent Adolescents

Uploaded by

You YouCopyright:

Available Formats

Hispanic Journal of

Behavioral Sciences

http://hjb.sagepub.com

Coping With Discrimination Among Mexican Descent Adolescents

Lisa M. Edwards and Andrea J. Romero

Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 2008; 30; 24

DOI: 10.1177/0739986307311431

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://hjb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/30/1/24

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences can be

found at:

Email Alerts: http://hjb.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://hjb.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations http://hjb.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/30/1/24

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Hispanic Journal of

Behavioral Sciences

Volume 30 Number 1

February 2008 24-39

Coping With Discrimination 2008 Sage Publications

10.1177/0739986307311431

Among Mexican Descent http://hjb.sagepub.com

hosted at

Adolescents http://online.sagepub.com

Lisa M. Edwards

Marquette University

Andrea J. Romero

The University of Arizona

The current research is designed to explore the relationship among discrimina-

tion stress, coping strategies, and self-esteem among Mexican descent youth

(N = 73, age 11-15 years). Results suggest that primary control engagement and

disengagement coping strategies are positively associated with discrimination

stress. Furthermore, self-esteem is predicted by an interaction of primary control

engagement coping and discrimination stress, such that at higher levels of discrim-

ination stress, youth who engaged in more primary control engagement coping

reported higher self-esteem. The authors findings indicate that Mexican descent

youth are actively finding ways to cope with the common experience of negative

stereotypes and prejudice, such that their self-esteem is protected from the stress-

ful impact of discrimination and prejudice. Implications of these findings for

Latino/a youth resilience are discussed.

Keywords: discrimination; coping; self-esteem; Mexican adolescents

E arly theoretical models argued that the experience of discrimination

directly negatively influenced mental health as a result of its effect on

individuals basic human drive to feel included in social groups and to

avoid social rejection (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Maslow, 1968; Rosenberg,

1979; Tajfel & Turner, 1986). However, research has demonstrated that

Authors Note: This project was funded by the small grants program at the College of Social

and Behavioral Sciences, The University of Arizona, and by the funding from the University of

Arizona Foundation awarded to Dr. Romero. The authors thank all students who worked on this

project in various forms and various stages including Ada Wilkinson-Lee, Lisa Lapeyrouse,

Yvonne Montoya, Julieta Gonzalez, and Veronica Vensor. Correspondence concerning this

article should be addressed to Lisa M. Edwards, Department of Counseling and Educational

Psychology, Marquette University, 146 Schroeder Health Complex, Milwaukee, WI 53201;

e-mail: lisa.edwards@marquette.edu.

24

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 25

discrimination does not affect all individuals in the same manner, perhaps

in part due to the effects of individual differences such as personality char-

acteristics, ethnicity, and/or gender identification (Crocker & Major, 1989;

Porter & Washington, 1993). There is still a paucity of research on the expe-

rience of discrimination from the targets perspective, as well as research

about the ways in which individuals actually cope with discrimination in

their lives (Romero & Roberts, 1998; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). We argue,

as others have, that person and situation factors are important to understand

why some minority youth are negatively affected by discrimination and other

youth are more resilient (Crocker & Major, 1989; Porter & Washington, 1993).

In the current study we explore how Mexican descent youth experience and

cope with discrimination, and how the coping strategies they employ relate

to their overall self-esteem.

Discrimination Among Mexican Youth

Discrimination has been characterized as the daily hassles that occur

because of the lower status of minority groups, including negative stereo-

types or prejudiced comments, as well as negative actions toward individu-

als based on ethnic group membership (Sellers & Shelton, 2003). Empirical

findings indicate that discrimination has a negative impact on the mental

health of U.S. ethnic minority children and adolescents by its relation to

depressive symptoms and low self-esteem and well-being (Allison, 1998;

Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999; Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Lee,

2003, 2005; Phinney, Madden, & Santos, 1998; Romero & Roberts, 2003a,

2003b; Sanders Thompson, 1996; Szalacha et al., 2003; Ying, Lee, & Tsai,

2000). It is important to understand the impact of discrimination among

Latino/a youth not only because they are the largest ethnic minority in the

United States and the fastest growing segment of the population under 18

years old (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001), but also because discrimination may

hinder optimal functioning in childhood and adolescence and can nega-

tively affect future adjustment and mental health (Compas, Connor-Smith,

Saltzman, Thomsen, & Wadsworth, 2001).

Studies indicate that Latino/a youth report discrimination as pervasive

and associated with significantly higher rates of depressive symptoms

(Chavez, Moran, Reid, & Lopez, 1997; Fennelly, Mulkeen, & Giusti,

1998; Fisher, Wallace, & Fenton, 2000; Hovey, 2000; Hovey & King,

1996; Romero & Roberts, 2003a, 2003b; Roberts et al., 1999; Sanchez &

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

26 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

Fernandez, 1993) as well as risky health behaviors (Romero, Carvajal,

Valle, & Ordua, 2007; Romero, Martinez, & Carvajal, 2007). Latino/a

youth describe discrimination based on English fluency, immigration con-

cerns, negative stereotypes, poverty, and skin color. Discriminatory com-

ments and behaviors are most frequently received from peers, teachers, as

well as other members of society (Fennelly et al., 1998; Romero &

Roberts, 2003b; Rosenbloom & Way, 2004). While studies have indicated

the harmful effects of discrimination in Latino/a youth, little is known

about how youth cope with the stress from these experiences (Romero &

Roberts, 1998; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). More research is therefore

needed to better understand the subjective experience of discrimination, as

well as how youth employ coping strategies to deal with these challenges.

Subjective Experiences of Discrimination

Individual differences are often overlooked in the measurement of dis-

crimination because it is assumed that the experience of discrimination for

ethnic minority groups will be universal for everyone in the group. The

majority of past studies have investigated discrimination in an objective man-

ner, generally indicated by the number of discriminatory events experienced.

Few studies have assessed discrimination as a subjective stressful experience,

which would probe the degree to which an individual may feel stressed or

bothered by discrimination and would more accurately understand the tar-

gets experience (Padilla & Perez, 2003; Romero & Roberts, 2003b; Sellers

& Shelton, 2003). Lazarus and Folkmans (1984) model of stress and coping

posits that the subjective perception of stress is a result of the interaction

between situational contexts and person characteristics, and it is necessary to

assess the stress beyond simply identifying whether the event occurred. This

framework is useful because it allows for individual differences; thus, we can

avoid assumptions that the experience of discrimination is the same for all

individuals. The measurement of the subjective experience of discrimination

as a stressor may improve our understanding of within-group variance about

the influence of discrimination on mental health.

Coping With Discrimination

Discrimination experiences challenge the adolescent target and require

different types of efforts to manage the stress. Compas and colleagues have

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 27

discussed coping among children and adolescents and provided a frame-

work that further elucidates coping processes by describing dimensions of

control and engagement with stressors (Compas, Champion, & Reeslund,

2005; Compas et al., 2001). They describe primary control engagement

coping strategies, which involve direct coping with the stressor or ones

emotions and include problem solving, emotional expression, and emotional

modulation. Secondary control coping relates to accommodation strategies

such as acceptance, cognitive restructuring, and distraction. Disengagement

coping is coping that distances ones thoughts, emotions, and physical pres-

ence from the stressor, such as denial and wishful thinking. Finally, involun-

tary engagement coping can be considered automatic responses to stress such

as emotional reactivity, and involuntary disengagement involves automatic

responses such as escape and emotional numbing. Compas and colleagues

have noted that effortful engagement strategies such as primary and sec-

ondary control coping are generally associated with fewer behavioral and

emotional problems in children and adolescents (Compas et al., 2001).

Only a few studies have investigated how Latino/a youth cope with dis-

crimination (Fennelly et al., 1998; Romero & Roberts, 2003a). A recent

longitudinal study that investigated perceived adult and peer discrimina-

tion among ethnic minority youth (Greene et al., 2006) suggested that eth-

nic identity moderated the relationship between perceived discrimination

and well-being. Specifically, ethnic identity buffered the negative effects

of peer discrimination on self-esteem among Black, Latino/a, and Asian

American adolescents. Furthermore, ethnic identity affirmation was found

to be a resource for youth when dealing with discrimination from peers

in particular.

Although the field is beginning to better understand the role of ethnic

identity as a buffer of discrimination, little is known about other coping

resources or strategies that adolescents may use to deal with discrimination

(Rodriguez & Morrobel, 2004). Furthermore, past research about discrimi-

nation has relied on objective indicators of discrimination rather than mea-

suring the subjective experience and stress caused by these episodes.

Research is needed to explore Latino/a youths experiences of discrimina-

tion in their lives, as well as the coping strategies that they report they are

using. In addition, it is important to identify the relationship of coping

strategies that Latino/a youth use to self-esteem, to understand the potential

benefits of these strategies on the well-being of adolescents. The current

study will explore the buffering effects of engagement, disengagement, and

involuntary control coping strategies on discrimination stress for Mexican

descent adolescent self-esteem.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

28 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

Method

Participants

A sample of 73 adolescents (11-15 years old, average age 13 years) were

recruited from an urban Southwest community local middle school (79% of

sample) and local community centers (21% of sample). No significant dif-

ferences in basic demographics were found between the school sample and

community center sample. The ethnic background of this sample reflected

urban Southwest cities near border regions. The median family income in

the neighborhood area where youth were recruited was under $14,000, with

approximately 39% single female-headed households and 80% economi-

cally disadvantaged households based on Department of Housing and

Urban Development income limits and federal free lunch eligibility.

The sample was almost evenly split between females (n = 40, 55%) and

males (n = 32, 44%); one respondent did not supply his or her gender. Eighty-

six percent of the youth identified as Mexican origin (including Mexican

American, Chicano, or Mexican National) and the other 14% were of mixed

Mexican ethnic heritage (White or American Indian). The majority classified

themselves as children of immigrant parents (49%), with 15% reporting they

themselves were immigrants, and 16% reporting they were third generation,

and 20% fourth generation or later. The youth were evenly split on language

use, as measured by the Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics

(BAS; Marin & Gamba, 1996): 38% were English dominant, 33% were

bilingual, and 29% were Spanish dominant. All participants parents signed

active consent forms to allow their children to participate in the study and all

youth signed assent forms before completing the survey. All forms were pro-

vided in English and Spanish to all participants.

Materials

Demographics. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire that

included items about age, gender, and ethnicity.

Language preference. The BAS for Hispanics (Marin & Gamba, 1996)

language use subscale consists of six items that assess language preference

with separate questions per language (English and Spanish) in reference to

(a) being at home, (b) when with friends, and (c) when watching TV. A

sample question is How often do you speak English with your friends?

These items have a four-item response range (4 = always, 3 = often, 2 =

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 29

sometimes, and 1 = never). English ( = .88) and Spanish ( = .72) prefer-

ences were dichotomized into high or low separately based on median

scores. Three levels of language preference were created based on the fol-

lowing categories: (a) Spanish preference (low English, high Spanish); (b)

bilingual preference (high English and high Spanish); and (c) English pref-

erence (high English and low Spanish).

Coping. The measure for coping was comprised of 21 items from previ-

ous scales to assess the degree to which participants used various coping

strategies, including engagement and disengagement (Wills, 1986; Wills,

McNamara, & Vaccaro, 1995; Wills, Sandy, Yaeger, Cleary, & Shinar,

2001). Respondents indicated the frequency with which they engaged in

coping strategies by using a Likert-type scale (4 = all the time, 3 = most of

the time, 2 = some of the time, and 1 = none of the time). Five items were

included to measure primary control engagement coping, such as think of

ways to take care of the problem and talk to someone about my feelings.

The internal consistency of this subscale was .68. Eleven items were

included to measure disengagement coping, watch TV so I wont think

about it and pretend the situation isnt happening. The internal consistency

of this subscale was .72. Finally, involuntary engagement coping was com-

prised of two items: get angry and take it out on someone else by yelling

or hitting. Cronbachs alpha for these items was .62.

Discrimination stress. The discrimination subscale from the Bicultural

Stressors Scale (Romero & Roberts, 2003a) was used to assess the frequency

and perceived stressfulness of various discrimination experiences. Eleven dis-

crimination items from this scale were included (e.g., Sometimes I feel it is

harder to succeed because of my ethnic background, I am not accepted

because of my ethnicity, and I do not like it when others put down people of

my ethnic background). The possible range of responses to each stressor are

does not apply (coded as 0), not stressful at all (coded as 1), a little bit stress-

ful (coded as 2), quite a bit stressful (coded as 3), and very stressful (coded as

4). These items provide information on whether youth experienced the stres-

sors (does not apply or is present) and the level of stressfulness (0-4). The

internal consistency of the discrimination subscale for the current sample was

.74. Mean discrimination stress across all items was computed by taking the

average score over all items with a range of 0-4.

Self-esteem. The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965) was

used to measure self-esteem. This scale is comprised of 10 items, of which

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

30 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

seven were used in the present study because of time constraints. Response

options range from 1 = never to 5 = almost always true. A sample item is

I feel that I have a number of good qualities. Four items were reverse

scored. All items were averaged for a total self-esteem score. The scale has

been shown to be reliable in previous studies with adolescents (Rosenberg,

1965, 1989), and specifically with Mexican Americans (Cervantes, Gilbert,

Salgado de Snyder, & Padilla, 1990-1991; Joiner & Kashubeck, 1996). The

internal consistency of the self-esteem scale for the study sample was .61.

Procedure

Surveys were administered to youth during a science/health class for

middle school students and after school hours at local community centers.

The survey took approximately 1 hour to complete. Bilingual/bicultural

trained project staff administered the surveys. Surveys were available in

English and Spanish, and participants had the option to answer the survey

in either language. The questionnaire was first developed in English and

then translated into Spanish by a professional translator. Local native

Spanish speakers, following guidelines suggested by Brislin (1976), back

translated the translations from Spanish to English. Six of the participants

elected to take the survey in Spanish.

Results

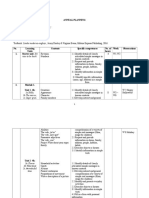

Descriptive statistics for variables of interest can be found in Tables 1

and 2. As can be seen, each discrimination item was reported by at least

26.4% of the sample or more. The items with the highest prevalence rates

were: I feel uncomfortable when others make jokes about people of my

ethnic background (71.8%) and I do not like it when others put down

people of my ethnic background (70.4%). The two most stressful items

(on a 1-4 Likert-type scale) were I do not like it when others put down

people of my ethnic background (M = 1.85, SD = 1.56) and I feel uncom-

fortable when others make jokes about people of my ethnic background

(M = 1.66, SD = 1.44). More than half the youth respondents (n = 46, 64%)

indicated at least one experience of discrimination that they ranked at a

level of 3 (quite a bit stressful) or 4 (very stressful). On average youth

reported that they had experienced 5 of the 11 discrimination experiences

(M = 4.99, SD = 3.26, range = 0-11). Only 11% (n = 8) of the youth reported

no discrimination experiences at all.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 31

Table 1

Descriptive Statistics for Discrimination Items (N = 68)

Percentage

Who

Experienced Degree of Degree of

Stressor Stress Stress

% (n) M (SD) Range

A. I have been treated badly because of my accent 29.2 (21) 0.65 (1.11) 0-4

B. I have worried about family members 43.1 (31) 1.06 (1.38) 0-4

or friends having problems with immigration

C. I do not feel comfortable with people whose 52.8 (38) 0.64 (0.68) 0-2

culture is different from my own

D. I feel uncomfortable when others make 71.8 (51) 1.66 (1.44) 0-4

jokes about people of my ethnic background

E. I have had problems at school because of 26.4 (19) 0.61 (1.22) 0-4

my poor English

F. I do not like it when others put down 70.4 (50) 1.85 (1.56) 0-4

people of my ethnic background

G. I have felt that others do not accept 40.3 (29) 1.11 (1.52) 0-4

me because of my ethnic background

H. I feel that I cant do what most American 45.8 (33) 0.99 (1.33) 0-4

kids do because of my parents culture

I. I feel that belonging to a gang is part 26.4 (19) 0.56 (1.10) 0-4

of representing my ethnic group

J. I do not understand why people from 48.6 (35) 1.11 (1.40) 0-4

a different ethnic background act a certain way

K. I feel that it will be harder to succeed 45.8 (33) 0.88 (1.17) 0-4

because of my ethnic background

Note: = .78.

Independent t tests were conducted to investigate age and gender differ-

ences in self-esteem, discrimination stress, engagement coping, and disen-

gagement coping and involuntary coping. Age was dichotomized into early

(11-13 years; 65.4%) and middle adolescents (14-15 years; 34.6%). No sig-

nificant age differences or gender differences were found.

One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated that no language dif-

ferences were found for variables of interest, except discrimination stress,

(F[2, 65] = 4.12, p < .05). Bonferroni post hoc tests indicate that English-

preferred youth (n = 25, M = 3.70, SD = 5.23) reported significantly lower

discrimination stress compared to Spanish-preferred youth (n = 19, M =

8.69, SD = 6.41). No significant differences were found in discrimination

stress for comparisons to bilingual youth (n = 24, M = 5.82, SD = 5.62).

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

32 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

Table 2

Relationships Among Variables of Interest (N = 73)

Variable 1 2 3 4 5

1. Self-esteem 0.34*** 0.23* 0.03 0.21

2. Discrimination stress 0.26* 0.30* 0.15

3. Primary control engagement coping 0.57*** 0.10

4. Disengagement coping 0.29*

5. Involuntary engagement coping

M 3.51 1.01 2.49 2.28 2.09

SD 0.71 0.73 0.67 0.54 0.86

Note: *p < .05. ***p < .001.

Generational differences were found with a one-way ANOVA for dis-

crimination stress (F[3, 50] = 3.36, p < .05). Immigrant youth (n = 7, M =

1.5, SD = .80) reported significantly more discrimination stress compared

to fourth generation or later youth (n = 11, M = .51, SD = .73). Immigrant

youth (n = 7, M = 7.14, SD = 3.43) compared to fourth generation or later

youth (n = 11, M = 2.73, SD = 2.49) also reported more total stressors

(F[3, 50] = 3.27, p < .05). However, there were no differences in discrimi-

nation stress threshold between generations based on one-way ANOVA. No

significant differences for coping were found by generation.

Pearson product-moment correlation was conducted with all variables of

interest (see Table 2). Discrimination stress was significantly associated with

primary control engagement coping (r = .26, p < .05) and disengagement

coping (r = .30, p < .05), but not involuntary engagement coping. Higher

self-esteem was significantly related to less discrimination stress (r = .34,

p < .001) and more primary control engagement coping (r = .23, p < .05).

The main and interactive effects of discrimination stress and coping on self-

esteem were assessed using hierarchical multiple regression (see Table 3).

First the main effects, discrimination stress and primary control engage-

ment strategies were entered into the regression equation in steps 1 and 2.

Next, the two-way interaction of discrimination stress and primary control

engagement coping was entered. As can be seen in Table 3, the main effect

of discrimination stress ( = .45) was significant, accounting for 10% of

the variance in self-esteem. The main effect of primary control engagement

coping was also significant ( = .29), accounting for an additional 10.5% of

the variance in self-esteem. The interaction between discrimination stress

and primary control engagement coping was significant ( = .25), revealing

incremental utility by accounting for an additional 5% of the variance,

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 33

Table 3

Hierarchical Multiple Linear Regression Analyses

Predicting Self-Esteem

Regression Step R Adj. R2 R2 F(df) Std. t

Model #1

1. Mean discrimination stress .34 .10 .10 9.02(1, 70) .45 4.20***

2. Primary control engagement .48 .21 .11 10.18(2, 69) .29 2.70**

3. Stress Coping Interaction .54 .26 .05 9.11(3, 68) .25 2.37*

Model #2

1. Mean discrimination stress .34 .10 .10 9.02(1, 70) .37 3.08**

2. Disengagement coping .35 .10 4.77(2, 69) .09 .76

Model #3

1. Mean discrimination stress .34 .10 .10 9.02(1, 70) .32 2.79**

2. Involuntary coping .37 .11 .01 5.47(2, 69) .15 1.34

Note: *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

resulting in a total adjusted R2 of .26. To examine the form of the interaction, we

computed median splits of discrimination stress and primary control engage-

ment coping scores and generated separate discrimination stress-self-esteem

lines for individuals high and low on primary control engagement coping.

As shown in Figure 1, at higher levels of discrimination, youth who

engaged in high primary control engagement coping also reported higher

self-esteem, and those with low levels of primary control engagement cop-

ing strategies reported significantly lower self-esteem.

The same approach to hierarchical multiple linear regressions was con-

ducted with disengagement coping and with involuntary coping. However,

results indicated that no significant main effects were found for either type

of coping in relation to self-esteem. A significant main effect of discrimi-

nation stress was found in both models (see Table 3).

Discussion

The current study explored the relationship among discrimination stress,

coping strategies, and self-esteem among Mexican descent adolescents in

an effort to identify positive resources that might help youth as they face

challenges such as discrimination (Lopez et al., 2002; Rodriguez &

Morrobel, 2004). Results indicate that the majority of youth did report dis-

crimination experiences and, at times, with high levels of stressfulness.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

34 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

Figure 1

Relationship Between Discrimination Stress and Self-Esteem as a

Function of Primary Control Engagement Coping

4.5

4

Self-Esteem (1-5)

3.5

2.5

Low Mean Stress High Mean Stress

Dichotomized Discrimination Stress

Low Engagement Coping

High Engagement Coping

These findings are consistent with previous research (Chavez et al., 1997;

Fennelly et al., 1998; Fisher et al., 2000; Hovey, 2000; Hovey & King,

1996; Romero & Roberts, 1998, 2003b), and highlight the pervasive nature

of prejudice that still plagues the lives of many ethnic minority youth.

Higher discrimination stress was associated with lower self-esteem; how-

ever, a high level of engagement coping reduced the negative effect of high

levels of discrimination stress on self-esteem in the current study. Individual

differences in the resilience of youth have important implications for under-

standing existing ethnic/racial health disparities.

Immigrant youth reported more total stressors and higher levels of stress

when compared to fourth generation or later youth, yet no other genera-

tional comparisons were significantly different in the current sample.

Previous research has documented that immigrant youth report higher total

experiences of discrimination with this same measure (Romero & Roberts,

2003b), which is consistent with theory suggesting that immigrant groups

may be targeted for greater discrimination than nonimmigrants (Padilla &

Perez, 2003). In the current study, youth who reported preferring to speak

Spanish reported more discrimination stress than English speakers, but not

significantly more than bilingual youth. Discrimination stress may be com-

pounded for youth who are immigrants and who predominantly speak

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 35

Spanish. While these experiences may be more frequent or intense for

immigrant and Spanish speakers, the current findings indicate that the

majority of youth did report discrimination and resultant stress that influ-

enced their global self-esteem.

The negative significant relationship between self-esteem and discrimi-

nation stress in this sample provides additional support for the negative

impact of this particular stressor on the overall well-being of Mexican

descent youth (Romero & Roberts, 2003a, 2003b; Szalacha et al., 2003).

Higher discrimination stress was associated with more engagement coping,

more disengagement coping, but not involuntary engagement coping, sim-

ilar to previous findings about Mexican American adolescents coping with

general stress (Kobus & Reyes, 2000). Finally, high levels of primary con-

trol engagement buffered the negative effects of high discrimination on

adolescents self-esteem, suggesting that this type of coping strategy was

effective (Compas et al., 2001). Engagement strategies are generally asso-

ciated with less behavioral and emotional problems in children and adoles-

cents (Compas et al., 2001), and for Mexican descent youth, therefore,

these strategies may also be a useful resource in times of discrimination

stress in particular. As mental health professionals work with youth to help

them experience well-being and manage discrimination stress, teaching

about engagement coping strategies may be an important avenue for inter-

vention or prevention.

The results of the current study advance the literature about how

Mexican descent adolescents cope with discrimination. However, care must

be taken with the degree of generalization based on these results, as causal

effects cannot be assumed with a cross-sectional survey design. In addition,

results from a convenience sample Mexican descent youth may not be gen-

eralizable to other Latino/a subgroups (Umaa-Taylor & Fine, 2001) or

other minority ethnic groups. The sample size of the current study had suf-

ficient power to detect significance; yet, future studies should be conducted

with larger samples over multiple time points. A second limitation of this

study relates to measurement issues of coping and self-esteem among early

adolescents. As noted by Compas and colleagues, because of the lack of

standard coping measures for adolescents inconsistent research findings

may be attributed to the usage of different definitions and assessment meth-

ods to measure coping. Finally, the low internal consistency of the self-

esteem measure may be primarily due to the fact that only 7 of the original

10 items were employed in the current study because of limited time for

youth to complete the survey during school hours. In addition, the

Rosenberg self-esteem measure has been used reliably in previous literature

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

36 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

with Mexican descent adolescents (Cervantes et al., 1990-1991; Choi,

Meininger, & Roberts, 2006; Joiner & Kashubeck, 1996); however, none of

these studies have included early adolescents as young as 11 years old as

were surveyed in the current study.

Given the existing mental and physical health disparities faced by

Latino/a youth, further investigation into youth resilience and well-being is

critical, particularly for those who provide direct health services to ethnic

minority youth, including clinicians and public health service providers.

Future research can explore variables that may moderate or mediate the

relationship between discrimination and well-being, including skin color,

gender, acculturative stress, and poverty. In addition, several researchers

have suggested that ethnic minority individuals use cultural strengths to

help buffer the effects of discrimination or other cultural stressors (Lopez

et al., 2002; Sue & Constantine, 2003; Walters & Simoni, 2002); perhaps

future research may further investigate culturally based coping strategies,

such as ethnic identity, familism, and religion/spirituality among Mexican

descent youth more specifically (Edwards & Lopez, 2006; Romero &

Roberts, 2003a; Romero & Ruiz, 2007). It is important that researchers

continue to study the complex influence of cultural contexts and the myr-

iad resources that Latino/a adolescents use to cope with challenges in their

lives to help promote their optimal functioning and well-being.

References

Allison, K. W. (1998). Stress and oppressed social category membership. In J. K. Swim &

C. Stangor (Eds.), Discrimination: The targets perspective (pp. 149-170). New York:

Academic Press.

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attach-

ments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 177, 497-529.

Branscombe, N. R., Schmitt, M. T., & Harvey, R. D. (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimina-

tion among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(1), 135-149.

Brislin, R. W. (1976). Translation: Applications and research. New York: Gardner.

Cervantes, R. C., Gilbert, M. J., Salgado de Snyder, N., & Padilla, A. M. (1990-1991).

Psychosocial and cognitive correlates of alcohol use in younger adult immigrant and U.S.

born Hispanics. International Journal of the Addictions, 25, 687-708.

Chavez, D. V., Moran, V. R., Reid, S. L., & Lopez, M. (1997). Acculturative stress in children:

A modification of the SAFE scale. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 19, 34-44.

Choi, H., Meininger, J. C., & Roberts, R. E. (2006). Ethnic differences in adolescents mental

distress, social stress, and resources. Adolescence, 41, 263-283.

Compas, B. E., Champion, J. E., & Reeslund, K. (2005). Coping with stress: Implications for

preventive interventions with adolescents. Prevention Researcher, 12(3), 17-20.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 37

Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E.

(2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and

potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87-127.

Crocker, J., & Major, B. (1989). Social stigma and self-esteem: The self-protective properties

of stigma. Psychological Review, 96, 608-630.

Edwards, L. M., & Lopez, S. J. (2006). Perceived family support, acculturation, and life satis-

faction in Mexican American youth: A mixed methods exploration. Journal of Counseling

Psychology, 53, 279-287.

Fennelly, K., Mulkeen, R., & Giusti, C. (1998). Coping with racism & discrimination. In H. I.

McCubbin, E. A. Thompsom, A. I. Thompson, & J. E. Fromer (Eds.), Resilience in Native

American and immigrant families (pp. 367-383). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Fisher, C. B., Wallace, S. A., & Fenton, R. E. (2000). Discrimination distress during adoles-

cence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 679-695.

Greene, M. L., Way, N., & Pahl, K. (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimi-

nation among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological

correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218-238.

Hovey, J. D. (2000). Acculturative stress, depression and suicidal ideation in Mexican immi-

grants. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 6, 134-151.

Hovey, J. D., & King, C. A. (1996). Acculturative stress, depression, and suicidal ideation

among immigrant and second generation Latino adolescents. Journal of the American

Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 35, 1183-1192.

Joiner, G. W., & Kashubeck, S. (1996). Acculturation, body image, self-esteem, and eating dis-

order symptomatology in adolescent Mexican American women. Psychology of Women

Quarterly, 20, 419-435.

Kobus, K., & Reyes, O. (2000). A descriptive study of urban Mexican American adolescents

perceived stress and coping. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22, 163-178.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Lee, R. M. (2003). Do ethnic identity and other-group orientation protect against discrimina-

tion for Asian Americans? Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 133-141.

Lee, R. M. (2005). Resilience against discrimination: Ethnic identity and other-group orientation

as protective factors for Korean Americans. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 36-44.

Lopez, S. J., Prosser, E. C., Edwards, L. M., Magyar-Moe, J. L., Neufeld, J. E., & Rasmussen, H. N.

(2002). Putting positive psychology in a multicultural context. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez

(Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 700-714). New York: Oxford University Press.

Marin, G., & Gamba, R. J. (1996). A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The

Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioral

Sciences, 18, 297-316.

Maslow, A. (1968). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row.

Padilla, A. M., & Perez, W. (2003). Acculturation, social identity, and social cognition: A new

perspective. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 25, 35-55.

Phinney, J. S., Madden, T., & Santos, L. J. (1998). Psychological variables as predictors of per-

ceived ethnic discrimination among minority and immigrant adolescents. Journal of

Applied Psychology, 28, 937-953.

Porter, J. R., & Washington, R. E. (1993). Minority identity and self-esteem. Annual Review

of Sociology, 19, 139-161.

Roberts, R. E., Phinney, J. S., Masse, L. C., Chen, Y. R., Roberts, C. R., & Romero, A. J.

(1999). The structure and validity of ethnic identity among diverse groups of adolescents.

Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 300-322.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

38 Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences

Rodriguez, M. C., & Morrobel, D. (2004). A review of Latino youth development research and

a call for an asset orientation. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26, 107-127.

Romero, A. J., Carvajal, S. C., Valle, F., & Ordua, M. (2007). Adolescent bicultural stress and

its impact on mental well-being among Latinos, Asian Americans & European Americans.

Journal of Community Psychology, 35, 519-534.

Romero, A. J., Martinez, D., & Carvajal, S. C. (2007). Bicultural stress and adolescent risk

behaviours in a community sample of Latinos & non-Latino European Americans.

Ethnicity & Health, 12, 443-463.

Romero, A. J., & Roberts, R. E. (1998). Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural vari-

ables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 641-656.

Romero, A. J., & Roberts, R. E. (2003a). The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity

on discrimination and adolescents self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33,

2288-2305.

Romero, A. J., & Roberts, R. E. (2003b). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of

Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 171-184.

Romero, A. J., & Ruiz, M. (2007). Does familism lead to increased parental monitoring?

Protective factors for coping with risky behaviors. Journal of Child and Family Studies,

16, 143-154.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton

University Press.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Rosenberg, M. (1989). Society and the adolescent self-image. Middleton, CT: Wesleyan

University Press.

Rosenbloom, S. R., & Way, N. (2004). Experiences of discrimination among African

American, Asian American, and Latino adolescents in an urban high school. Youth &

Society, 35, 420-451.

Sanchez, J. I., & Fernandez, D. M. (1993). Acculturative stress among Hispanics: A bidimen-

sional model of ethnic identification. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 654-668.

Sanders Thompson, V. L. (1996). Perceived experiences of racism as stressful life events.

Community Mental Health Journal, 32, 223-233.

Sellers, R. M., & Shelton, J. N. (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrim-

ination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1079-1092.

Sue, D. W., & Constantine, M. G. (2003). Optimal human functioning in people of color in the

United States. In W. B. Walsh (Ed.), Counseling psychology and optimal human function-

ing (pp. 151-169). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Szalacha, L. A., Erkut, S., Garcia Coll, C., Alarcon, O., Fields, J. P., & Ceder, I. (2003).

Discrimination and Puerto Rican childrens and adolescents mental health. Cultural

Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 141-155.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1986). The social identity theory of intergroup behavior. In

S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 7-24). Chicago:

Nelson-Hall.

Umaa-Taylor, A. J., & Fine, M. A. (2001). Methodological implications of grouping Latino

adolescents into one collective ethnic group. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 23,

347-362.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2001). The Hispanic population: Census 2000 brief. Washington, DC:

U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistical Administration.

Walters, K. L., & Simoni, J. M. (2002). Reconceptualizing native womens health: An indi-

genist stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 520-524.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

Edwards, Romero / Discrimination and Coping 39

Wills, T. A. (1986). Stress and coping in early adolescence: Relationships to substance use in

urban school samples. Health Psychology, 5, 503-529.

Wills, T. A., McNamara, G., & Vaccaro, D. (1995). Parental education related to adolescent

stress-coping and substance use: Development of a mediational model. Health Psychology,

14, 464-478.

Wills, T. A., Sandy, J. M., Yaeger, A. M., Cleary, S. D., & Shinar, O. (2001). Coping dimen-

sions, life stress, and adolescent substance use: A latent growth analysis. Journal of

Abnormal Psychology, 110, 309-323.

Ying, Y., Lee, P. A., & Tsai, J. L. (2000). Cultural orientation and racial discrimination:

Predictors of coherence in Chinese American young adults. Journal of Community

Psychology, 28, 427-442.

Lisa M. Edwards is an assistant professor in the Counseling and Educational Psychology

Department at Marquette University. She received her PhD in counseling psychology from the

University of Kansas and was previously a research associate at the University of Notre Dame.

Her current research focuses on positive functioning and well-being among racial/ethnic minori-

ties in the United States. Specifically, she examines the influence of cultural resources (e.g.,

familismo, religion, and ethnic identity) on well-being among Latino/a adolescents, ethnically

diverse college students, and multiracial individuals. She is particularly interested in how youth

and adults use strengths to promote positive functioning in addition to buffering the negative

effects of discrimination and other bicultural stressors. She currently teaches graduate courses in

multicultural counseling, assessment, and group counseling, and she is a licensed psychologist

in Wisconsin. In her spare time, she enjoys traveling and spending time with friends and family.

Andrea J. Romero is an associate professor in the Mexican American Studies & Research

Center at the University of Arizona. She is an affiliate faculty member in the Psychology

Department and the Family Studies and Human Development Department. Her PhD (1997) is

in social psychology with a minor in quantitative methods from the University of Houston. Her

research focus is on understanding minority adolescent ethnic and racial health disparities in

the areas of mental health and substance use. Her publications focus on adolescent resiliencies

derived from ethnic identity, familism, and neighborhood resources. Her current research pro-

jects are designed to link theory with substance use prevention strategies for Mexican descent

teens. When she is not working on these issues, she enjoys going to the park with her family.

Downloaded from http://hjb.sagepub.com by taman mihaela on October 13, 2009

You might also like

- Multiple Minorities As Multiply Marginalized: Applying The Minority Stress Theory To LGBTQ People of ColorDocument22 pagesMultiple Minorities As Multiply Marginalized: Applying The Minority Stress Theory To LGBTQ People of ColorVincent Jeymz Kzen VillaverdeNo ratings yet

- Final Coaching SociologyDocument73 pagesFinal Coaching SociologyBenjhon S. Elarcosa92% (12)

- Psychology Question Bank 2021 (Paper 3) (1st Term)Document6 pagesPsychology Question Bank 2021 (Paper 3) (1st Term)Mayookha100% (2)

- Research ProposalDocument15 pagesResearch ProposalNica Duco100% (3)

- Micro Aggression ArticleDocument16 pagesMicro Aggression ArticlechochrNo ratings yet

- Just Listening and Speaking - Pre-Intermediate PDFDocument89 pagesJust Listening and Speaking - Pre-Intermediate PDFYou YouNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Framework Exploring Social Media, Eating Disorders, and Body Dissatisfaction Among Latina AdolescentsDocument15 pagesA Conceptual Framework Exploring Social Media, Eating Disorders, and Body Dissatisfaction Among Latina AdolescentsIsmayati PurnamaNo ratings yet

- Juang Etal., 2016Document13 pagesJuang Etal., 2016Eliora ChristyNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Self Esteem Among Mexican Immigrant Adolescents: An Examination of Well Being Through A Biopsychosocial PerspectiveDocument12 pagesPredictors of Self Esteem Among Mexican Immigrant Adolescents: An Examination of Well Being Through A Biopsychosocial PerspectiveDARSHINI A/P BALASINGAMNo ratings yet

- 16 - Minority Stress and Drinking CAPESDocument27 pages16 - Minority Stress and Drinking CAPESFabiana H. ShimabukuroNo ratings yet

- Stigma Burden FilipinosDocument11 pagesStigma Burden FilipinosJessica AlbaracinNo ratings yet

- Racism Mental Health and Mental Health PracticeDocument70 pagesRacism Mental Health and Mental Health PracticeAku LupayaNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Elusive Construct of Personalismo Among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban American AdultsDocument19 pagesMeasuring The Elusive Construct of Personalismo Among Mexican American, Puerto Rican, and Cuban American AdultsLemuel ConstantinoNo ratings yet

- Abao, J. Paper 1 Final Requirement PSY111-XxDocument6 pagesAbao, J. Paper 1 Final Requirement PSY111-XxMister CatNo ratings yet

- Research: "I Am My Own Gender": Resilience Strategies of Trans YouthDocument11 pagesResearch: "I Am My Own Gender": Resilience Strategies of Trans YouthVictor NamurNo ratings yet

- Racial Microaggressions in Everyday Life Implications For Clinical PracticeDocument16 pagesRacial Microaggressions in Everyday Life Implications For Clinical PracticeqthermalNo ratings yet

- Gendered Racism, Coping, Identity Centrality, and African American College Women's Psychological DistressDocument15 pagesGendered Racism, Coping, Identity Centrality, and African American College Women's Psychological DistressDika DivinityNo ratings yet

- La Familia y El Maltrato Como Factores de Riesgo en La Conducta AntisocialDocument9 pagesLa Familia y El Maltrato Como Factores de Riesgo en La Conducta AntisocialAnonymous 5hru18uSNo ratings yet

- Factores Riesgo y Protecc DelitoDocument13 pagesFactores Riesgo y Protecc DelitoMónica PortilloNo ratings yet

- Skin-Color Prejudice and Within-Group Racial Discrimination: Historical and Current Impact On Latino/a PopulationsDocument25 pagesSkin-Color Prejudice and Within-Group Racial Discrimination: Historical and Current Impact On Latino/a PopulationsRodriguez Serna Gloria IdeniaNo ratings yet

- Being Transgender Navigating Minority Stressors and Developing Authentic Self-Presentation (2013)Document19 pagesBeing Transgender Navigating Minority Stressors and Developing Authentic Self-Presentation (2013)bbt.gender.galaxyNo ratings yet

- Violence Against LGBTQ+ Persons: Research, Practice, and AdvocacyFrom EverandViolence Against LGBTQ+ Persons: Research, Practice, and AdvocacyEmily M. LundNo ratings yet

- JaneRuschel ResearcchPlanDocument6 pagesJaneRuschel ResearcchPlanBRENNDALE SUSASNo ratings yet

- Dej - Psychocentrism and HomelessnessDocument19 pagesDej - Psychocentrism and HomelessnessariaNo ratings yet

- Linking Adverse Childhood Effects and Attachment: A Theory of Etiology For Sexual OffendingDocument12 pagesLinking Adverse Childhood Effects and Attachment: A Theory of Etiology For Sexual OffendingAinur RosikhoNo ratings yet

- An Exploratory Study of Neglect and Emotional Abuse in Adolescents: Classifications of Caregiver Risk FactorsDocument15 pagesAn Exploratory Study of Neglect and Emotional Abuse in Adolescents: Classifications of Caregiver Risk FactorsCláudia Isabel SilvaNo ratings yet

- The Long-Term Effects of Childhood Sexual AbuseDocument8 pagesThe Long-Term Effects of Childhood Sexual AbuseMaheen ShaiqNo ratings yet

- Malgady Hero HeroineDocument6 pagesMalgady Hero HeroineIoana-Laura LucaNo ratings yet

- The Bedan Journal of Psychology 2013Document312 pagesThe Bedan Journal of Psychology 2013San Beda Alabang100% (5)

- EappDocument6 pagesEappAryannaNo ratings yet

- Racism in The Structure of Everyday WorldsDocument2 pagesRacism in The Structure of Everyday WorldsAnh Trịnh Thị DiệuNo ratings yet

- Consecuencias de Los Malos Tratos en Desarrollo PsicológicoDocument24 pagesConsecuencias de Los Malos Tratos en Desarrollo PsicológicoKari MüllerNo ratings yet

- Health Disparities Between Genderqueer, Transgender, and Cisgender Individuals: An Extension of Minority Stress TheoryDocument36 pagesHealth Disparities Between Genderqueer, Transgender, and Cisgender Individuals: An Extension of Minority Stress TheoryMudassar HussainNo ratings yet

- Stigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and HealthDocument16 pagesStigma, Prejudice, Discrimination and Healthnicoleta5aldea100% (1)

- Aa Professionals in Higher Ed - Coping With Racial Microaggressions Full Journal ArticleDocument18 pagesAa Professionals in Higher Ed - Coping With Racial Microaggressions Full Journal Articleapi-718408484No ratings yet

- Behavioral Diabetes: Alan M. Delamater David G. Marrero EditorsDocument522 pagesBehavioral Diabetes: Alan M. Delamater David G. Marrero EditorsLigia AbdalaNo ratings yet

- Drug and Substance AbuseDocument5 pagesDrug and Substance AbuseWafula RonaldNo ratings yet

- Downey, Daniels - 2020 - The Dynamic Ecology of Rejection and Acceptance Mental Health ImplicationsDocument5 pagesDowney, Daniels - 2020 - The Dynamic Ecology of Rejection and Acceptance Mental Health ImplicationspanospanNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument15 pagesResearch ProposalMahnoor Mansoor100% (1)

- Familia y MaltratoDocument9 pagesFamilia y MaltratoEva Marie LizárragaNo ratings yet

- Defense May 9 2018Document50 pagesDefense May 9 2018louie johnNo ratings yet

- Ajph 2013 301241Document9 pagesAjph 2013 301241Neeko JayNo ratings yet

- The Social Psychology of Discrimination: Theory, Measurement and ConsequencesDocument29 pagesThe Social Psychology of Discrimination: Theory, Measurement and ConsequencesRohit Vijay PatilNo ratings yet

- Sexual Orientation and Suicide Risk in The Philippines: Evidence From A Nationally Representative Sample of Young Filipino MenDocument14 pagesSexual Orientation and Suicide Risk in The Philippines: Evidence From A Nationally Representative Sample of Young Filipino MenJASPER KENNETH ARIOLANo ratings yet

- Herman Gendered Restrooms and Minority Stress June 2013Document16 pagesHerman Gendered Restrooms and Minority Stress June 2013Julisa FernandezNo ratings yet

- Primer Aug 2013Document5 pagesPrimer Aug 2013karloncha4385No ratings yet

- Reading and Rubin - 2011 - Advocacy and Empowerment Group Therapy For LGBT ADocument13 pagesReading and Rubin - 2011 - Advocacy and Empowerment Group Therapy For LGBT AjnNo ratings yet

- For Psychological Practice With Sexual Minority Persons: Apa GuidelinesDocument64 pagesFor Psychological Practice With Sexual Minority Persons: Apa GuidelinesRita TorresNo ratings yet

- Group Self-Identification, Drug Use and Psychosocial Correlates Among Spanish AdolescentsDocument6 pagesGroup Self-Identification, Drug Use and Psychosocial Correlates Among Spanish AdolescentsDaniel Cossío MiravallesNo ratings yet

- Private and PDA Among Intraracial and Interracial Adolescent CouplesDocument26 pagesPrivate and PDA Among Intraracial and Interracial Adolescent CouplesMatriack GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Build Your Social Confidence", A Social Anxiety Group For CollegeDocument17 pagesBuild Your Social Confidence", A Social Anxiety Group For CollegejuaromerNo ratings yet

- Fitting in and Fighting Back: Stigma Management Strategies Among Homeless KidsDocument24 pagesFitting in and Fighting Back: Stigma Management Strategies Among Homeless KidsIrisha AnandNo ratings yet

- Educational Resilience Among African Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in South AfricaDocument20 pagesEducational Resilience Among African Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse in South AfricaDNo ratings yet

- Ten Considerations in Addressing Cultural Differences in PsychotherapyDocument7 pagesTen Considerations in Addressing Cultural Differences in PsychotherapyRirikaNo ratings yet

- Challenging Racism & Sexism - Alternatives To Genetic Explanations :: ReviewDocument4 pagesChallenging Racism & Sexism - Alternatives To Genetic Explanations :: ReviewDionisio MesyeNo ratings yet

- Trans-Identity, Different Bodies, Equal RightsDocument17 pagesTrans-Identity, Different Bodies, Equal RightsArturo ArévaloNo ratings yet

- The Trauma of Racism:: Implications For Counseling, Research, and EducationDocument5 pagesThe Trauma of Racism:: Implications For Counseling, Research, and EducationSally Ezz100% (1)

- From Candy Kids To Chemi-Kids - A Typology of Young Adults Who Attend Raves in The Midwestern United StatesDocument22 pagesFrom Candy Kids To Chemi-Kids - A Typology of Young Adults Who Attend Raves in The Midwestern United StatesšpanjolaNo ratings yet

- Colegio de San Juan de LetranDocument4 pagesColegio de San Juan de LetranMaria Lorena SanchezNo ratings yet

- Intent To Seek Counseling Among Filipinos - Examining Loss of Face and GenderDocument30 pagesIntent To Seek Counseling Among Filipinos - Examining Loss of Face and GenderCarlo CaparidaNo ratings yet

- Avance de Pia de Politicas CorrectoDocument13 pagesAvance de Pia de Politicas CorrectoEulalia EulaliaNo ratings yet

- Violence Against WomenDocument11 pagesViolence Against WomenSherwin Anoba CabutijaNo ratings yet

- Kashdan 2008Document7 pagesKashdan 2008Kissie SarnoNo ratings yet

- Five Paragraph EssayDocument7 pagesFive Paragraph EssayYou YouNo ratings yet

- Teste de MorfologieDocument6 pagesTeste de MorfologieYou YouNo ratings yet

- Destination UK - England Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesDestination UK - England Lesson PlanYou You100% (1)

- Planificare 8Document3 pagesPlanificare 8You YouNo ratings yet

- Planif IV SC 21 FairylandDocument9 pagesPlanif IV SC 21 FairylandYou YouNo ratings yet

- Analysis of English PrepDocument8 pagesAnalysis of English PrepYou YouNo ratings yet

- Planif Unit 4Document16 pagesPlanif Unit 4You YouNo ratings yet

- Planificarea Unitatilor de Invatare: Unit 1: Nice To Meet You All - 2 HDocument15 pagesPlanificarea Unitatilor de Invatare: Unit 1: Nice To Meet You All - 2 HYou YouNo ratings yet

- School Psychology International: Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies With School-Related StressDocument17 pagesSchool Psychology International: Assessment of Coping Styles and Strategies With School-Related StressYou YouNo ratings yet

- And Social Support Bullying and Stress in Early Adolescence: The Role of CopingDocument25 pagesAnd Social Support Bullying and Stress in Early Adolescence: The Role of CopingYou YouNo ratings yet

- Romeo Si Julieta-ChestionarDocument1 pageRomeo Si Julieta-ChestionarYou YouNo ratings yet

- Test VIDocument1 pageTest VIYou YouNo ratings yet

- Mental Health & TravelDocument18 pagesMental Health & TravelReyza HasnyNo ratings yet

- Outsourcing On Employee PerspectiveDocument13 pagesOutsourcing On Employee PerspectiveIyan David100% (1)

- Technology and Your Health Reading Comprehension Exercises 5560Document69 pagesTechnology and Your Health Reading Comprehension Exercises 5560Carla SalgadoNo ratings yet

- Aging PopulationDocument2 pagesAging Populationmohammed tahaNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Silence Revised Final Na TalagaDocument4 pagesBreaking The Silence Revised Final Na TalagaNicole Ann BaroniaNo ratings yet

- Designing A Polarity Therapy ProtocolDocument12 pagesDesigning A Polarity Therapy ProtocolTariq J FaridiNo ratings yet

- TFN MidtermsDocument12 pagesTFN MidtermsChang Pearl Marjorie P.No ratings yet

- 20 Egg Nurturing StrategiesDocument6 pages20 Egg Nurturing StrategiesTatjana Nikolić MilivojevićNo ratings yet

- Industrial HomeworkDocument5 pagesIndustrial Homeworkcfcyyedf100% (1)

- Narrative Review Burnout Students and ResidentsDocument19 pagesNarrative Review Burnout Students and ResidentsStefania TacuNo ratings yet

- B Inggris2006Document3 pagesB Inggris2006Henii Trynever GiveupNo ratings yet

- Handout Sa GuidanceDocument4 pagesHandout Sa GuidanceEunice De OcampoNo ratings yet

- There Are Three Kinds of Stress That Each Take A Toll On The BodyDocument6 pagesThere Are Three Kinds of Stress That Each Take A Toll On The BodyMd. Rakibul Islam RanaNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Stress Among Faculty Members ofDocument15 pagesFactors Affecting Stress Among Faculty Members ofMichevelli RiveraNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Teachers StressDocument4 pagesThesis On Teachers Stressdqaucoikd100% (2)

- Term PaperDocument19 pagesTerm PaperDelphy Varghese100% (1)

- Health Psychology: Bio Psychosocial Perspective: Ranya Al-Mandawi Dr. Tyrin Stevenson Psych 331Document6 pagesHealth Psychology: Bio Psychosocial Perspective: Ranya Al-Mandawi Dr. Tyrin Stevenson Psych 331Ranya NajiNo ratings yet

- Emotional IntelligenceDocument15 pagesEmotional IntelligenceMandar Raut100% (1)

- Mba Notes of ObDocument34 pagesMba Notes of ObShivangi BansalNo ratings yet

- Transkrip StressDocument26 pagesTranskrip StressPrasetyo Hendy KurniawanNo ratings yet

- INTRODUCTIONDocument9 pagesINTRODUCTIONSOBANAH A/P CHANDRAN STUDENTNo ratings yet

- Docslide - Us Malaysian University English Test Muet Paper 3 Mid Year 2010Document19 pagesDocslide - Us Malaysian University English Test Muet Paper 3 Mid Year 2010Vanishasri RajaNo ratings yet

- Level 1 Manual Modules 16 PDFDocument215 pagesLevel 1 Manual Modules 16 PDFMaria Bagourdi100% (5)

- Mpob - Work StressDocument23 pagesMpob - Work StressAdityaNo ratings yet

- Mircea Eliade MaitreyiDocument5 pagesMircea Eliade MaitreyiSorleaAlessandroNo ratings yet

- EPWired Magazine June Issue PDFDocument36 pagesEPWired Magazine June Issue PDFBorbála Heléna (Macika)No ratings yet

- Speaking NotesDocument30 pagesSpeaking NotesLovenia LawNo ratings yet

- Stress Management ActivitiesDocument6 pagesStress Management ActivitiesRonnel GolimlimNo ratings yet