Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Gutas - Modalities XII Century Translation Movement Spain

Gutas - Modalities XII Century Translation Movement Spain

Uploaded by

RodrigoJoseLimaOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Gutas - Modalities XII Century Translation Movement Spain

Gutas - Modalities XII Century Translation Movement Spain

Uploaded by

RodrigoJoseLimaCopyright:

Available Formats

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive?

Remarks on the Modalities of the Twelfth-Century Translation

Movement in Spain 1

Dimitri Gutas (Yale)

The translation movements from Greek into Arabic during the 8th to the 10th

centuries, and from Arabic into Latin from the 12th to the 13th, are complex

historical processes. Different from individual translation activities of solitary

scholars that prove not to have had historical agency, they do not easily lend

themselves to analysis, as I tried to argue a few years ago in my ,Greek Thought,

Arabic Culture. A key element in the attempt to arrive at some satisfactory

understanding of these processes - and I use the term ,understanding in its

Aristotelian sense of coming to recognize its causes - is asking the right kind

of questions of the historical evidence we possess, and especially discriminating

among the many different aspects of the problem - identifying its major modal-

ities, so to speak - and avoiding confusing issues that need to be kept separate.

Before I start with the question of my title, then, I need to make some major

discriminations. First of all, the noun ,Latins in the question is equivocal -

which Latins and when? For it certainly makes a difference, as Arabic-Latin

transmission was much more diffuse than Graeco-Arabic, and the centers and

foci of translation, let alone of reception, were more varied, both geographically

and temporally. Thus, briefly - and roughly - to review the well-known facts

without going into details, there are the initial translations of Gerbert and the

other earliest translations in Spain 2 at the turn of the 11th century 3; then there

1 Apart from some minor corrections and adjustments and the addition of references, this is

essentially the text of the lecture delivered during the evening session of the conference. The

contents and especially the style of the lecture, geared for an after-dinner evening delivery, have

been retained. I am grateful to Charles Burnett for graciously sending me pre-publication copies

of some of his articles - indispensable for anyone working in this field - and for his unflagging

willingness to share information; and to Dag Hasse for his customary helpful hints and sugges-

tions.

2 While treating of this subject, it is necessary to be precise with nomenclature. By Spain (and as

the occasion requires, Portugal) I will be referring to those parts of the Iberian peninsula under

Christian control, while by al-Andalus to those parts of the same peninsula under Muslim

control.

3 Cf. J. M. Millas-Vallicrosa, Las mas antiguas traducciones arabes hechas en Espana, in: Convegno

di scienze morali storiche e filologiche. Tema: Oriente ed Occidente nel Medio Evo, Rome

1957, 383-390.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

4 Dimitri Gutas

is the activity of Constantinus Africanus in Italy in the 11th century 4; then the

12th-century translations in Sicily but especially in Spain, a long period which

may be divided into a number of stages (Richard Lemay, perhaps rightly, divided

it into three): the beginnings, at the beginning of the century, with Petrus Alfonsi

and Adelard of Bath; then the great period of translations, starting right after

the reconquest of Saragossa in 1118 and lasting until the appearance in Toledo

of Gerard of Cremona, and covering an area, from east to west along the valley

of the Ebro up to and including Barcelona, and from north to south from

Pamplona to Toledo; and then, the latter third of the century, the work of

Gerard and Gundissalinus in Toledo 5. Then follows the even more complicated

13th century, when the work of translation goes on in Spain and continues in

Sicily with greater vigor, etc. - to say nothing of the later translations during

the Renaissance 6.

All these pre-Renaissance translation activities, spanning more than two cen-

turies, cannot be ascribed to the same motivations, the same goals, and the same

type of participants. Each stage, each period, has to be studied independently

in order for their differentiating qualities not to be leveled under the general

rubric of ,Arabic-Latin translations. It is necessary to discriminate the qualita-

tively different Arabic-Latin translation movement of the 12th century from the

previous incidental translation activities as well as from those that came in its

wake and as secondary responses to it. For let us consider: although there had

been sporadic translation activities from Arabic into Latin before the 12th cen-

tury as already mentioned, mostly of astrological, mathematical, and medical

nature (just as there had been sporadic translations from Greek into Arabic

before the Abbasids), this translation activity became a movement only in the

12th century. The Latins were quite aware of the cultural and scientific superior-

ity of the Arabs at least since the days of Charlemagne, if not earlier, and though

the Arabs were already in the Iberian peninsula where borders between the

Islamic and the Christian world were always porous, there was no transfer of

knowledge, much less any translations, in the 9th and 10th centuries. The 10th

century itself was decisive for the development of the Arabic sciences in al-

Andalus: during the reigns of the caliphs Abdarrah man III and his son al-

H akam II which lasted from 912 to 976, a significant portion of the philosophi-

cal and scientific knowledge of the East was brought to al-Andalus. And it is

precisely toward the end of the 10th century that we witness the first attempts

to translate some mathematical and astronomical material into Latin in northern

Spain 7, where perhaps the first western astrolabe was also made after Arabic

4 See in general Ch. Burnett/D. Jacquart (eds.), Constantine the African and Al Ibn al-Abbas

al-Magus. The Pantegni and Related Texts (Studies in Ancient Medicine 10), Leiden 1994.

5 Cf. R. Lemay, Dans lEspagne du XIIe siecle. Les Traductions de larabe au latin, in: Annales.

Economies, Societes, Civilisations 18 (1963), 639-665.

6 For a detailed account, with geographical localization, of both pre-Renaissance and Renaissance

translations see the contribution by Dag Hasse in this volume, 68-86.

7 Cf. Millas-Vallicrosa, Las mas antiguas traducciones (nt. 3).

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 5

models (the Carolingian astrolabe, according to Kunitzsch 8). Thus the introduc-

tion from the East of Arabic science and philosophy into al-Andalus, whose

borders with Latin Spain were, as I mentioned, porous, created a situation where

a significant amount of Arabic learning was theoretically available to the Latins

in close proximity to home. And yet, despite these few translation activities

which took place at the end of the 10th and during the 11th centuries, there was

no translation movement like the one we see in the 12th. Marie-Therese dAl-

verny recognized the problem explicitly: in her magisterial summation of the

scholarly developments on the 12th-century renaissance since Haskins, she said:

Why this promising prelude was not followed immediately by an increasing

stream of translations during the eleventh century is a question still unsolved. 9

This was in 1982, and though great advances have been made on numerous

matters of detail, the overall picture still evades us. In order to solve this prob-

lem, it is necessary to view the 12th-century translation movement in Spain as

something qualitatively distinct from the rest, and it is this movement that I will

be talking about. My purpose is not to discuss and explain the entire movement,

nor to review all the available literature on the subject - in other words, not to

attempt to write the book, ,Arabic Thought, Latin Culture -, but to make the

discriminations I mentioned and raise certain questions whose investigation may

lead to its eventual composition.

A second major discrimination I will be making is in the form of a disclaimer:

I will be talking only of the Arabic-Latin transmission of scientific and philo-

sophical texts in 12th-century Spain. Not only am I not competent to speak

about literary and artistic interactions between the medieval Arabic and Latin

worlds, but I am convinced that such interactions followed different patterns of

transmission and responded to social needs different from those of the scientific

and philosophical. Similarly, I will not be talking about the study of Islam and

of the Arabic language in medieval Europe, a subject which, though clearly

related to the broader issue under discussion, is yet a different problem and has

been addressed, to some degree, by dAlverny and others 10.

To come, then, to my subject thus circumscribed, the question of what there

was in Arabic for the Latins to receive has a number of components which

need to be answered or at least investigated separately in order to avoid the

8 Cf. P. Kunitzsch, The Role of al-Andalus in the Transmission of Ptolemys Planisphaerium and

Almagest, in: Zeitschrift fr Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften 10 (1995/96),

147-155, here: 153-154, and cf. his references to related literature there.

9 Cf. M.-Th. dAlverny, Translations and Translators, in: R. L. Benson/G. Constable (eds.), Renais-

sance and Renewal in the Twelfth Century, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, 421-462; repr. in her La

transmission des textes philosophiques et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Alder-

shot 1994, no. II, here: 440.

10 See her Variorum volume, La connaissance de lIslam dans lOccident medieval, ed. by M.

Gibson, Aldershot 1994; but there are earlier studies like the useful one by U. Monneret de

Villard, Lo studio dellIslam in Europa nel XII e nel XIII secolo (Studi e Testi 110), Vatican

1944, repr. 1972.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

6 Dimitri Gutas

confusion I mentioned earlier. Here I wish to concentrate on three of them, as

follows: (I) first, what there was for the Latins to receive and translate as texts

that were physically available, in the form of concrete manuscripts; (II) second,

and an inalienable concomitant of the first question, what there was in Greek

for the Latins to receive, and what determined their choice of the one over the

other; (III) and third, what the Latins were able to receive in concrete terms,

i. e., were able to translate. (IV) I will conclude with a general remark on a major

difference between the Graeco-Arabic and Arabic-Latin translation movements,

and what it tells us about the possible social and ideological causes of the latter.

I.

The first question, what there was physically available for the Latins to receive,

has a seemingly obvious and easy answer: everything - that is, the entire Arabic

corpus of writings until the 12th century - was theoretically available to all who

would have wanted to translate it. But this is certainly not what happened, which

means that there were factors in operation which enforced a certain selection

in the material that was eventually received. In order to identify these factors

we have to specify the question some more before we can answer it: we have

to ask, what there was available of such writings in the localities where the

Latins would be looking for manuscripts to translate, and of which they had

knowledge. Since I will be speaking of the 12th-century translation movement

in Spain, it is natural to start by looking at the situation with Arabic manuscripts

in al-Andalus and inquiring into what was available there. Two 11th-century

Arabic works from al-Andalus give us information on this matter: the first is

Ibn H azms essay on ,The Excellence of al-Andalus (R. f fad l al-Andalus),

which gives a selective bibliography of what the author considers the most

important works composed by Andalusian authors. Ibn H azm cast his net wide

and included all disciplines, Arab and foreign alike: he listed first the Ma-

lik religious scholars and their works, then the Safis and then the Z ahirs. Next

he moved on to lexicography and philology, and then to poetry and history.

Having completed the Arab sciences he went on with the foreign sciences,

medicine, philosophy, and mathematics, and closed with theology 11. The Anda-

lusocentric 12 stance which is implied by the very composition of the work is

made explicit toward the end where Ibn H azm concludes by saying that the

works by Andalusian authors which he cited have no equal in the entire Islamic

11 See the discussion and translation of the work by Ch. Pellat, Ibn H azm, bibliographe et apolo-

giste de lEspagne musulmane, in: Al-Andalus 19 (1954), 53-102.

12 I must apologize for this rather barbaric sounding neologism, but it is made imperative by the

need for a one-word adjective (and eventually, also a substantive, to come later) describing the

attitude of Andalusian scholars which considered al-Andalus as the focal point of historical

development and the culmination of world civilization.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 7

world except perhaps in Iraq 13. Here Ibn H azm placed al-Andalus culturally

second only to Iraq in a gesture which is due more to traditional respect toward

the seat of the caliphate than to sincerity of opinion. It is a tremendous boast,

and one that is hardly justified by historical reality, especially in the fields of

science and philosophy, which is our main concern here, and especially in his

time, early 11th century, when there was hardly any philosophy in Andalus. But

the attitude is what is important.

The second work is S aid al-Andaluss ,Categories of Nations (T abaqat al-

umam), which presents a very interesting picture of the cultural history of the

world from the point of view of Islamic Toledo: according to S aid, the march

of civilization starts from its beginnings with the Chaldeans, ancient Persians,

and Hindus, proceeds successively through the Greeks, the Romans, the Egyp-

tians, and the Abbasid Muslims, and it finally culminates with the Andalusian

Muslims and Jews in Toledo in the middle of the 11th century 14. In the course

of his discussions of the contributions of each nation, S aid enumerates all the

sciences that were transmitted - essentially all the sciences in the Greek curricu-

lum of higher studies established in late antiquity and passed on to the Muslims.

The largest number of scholars cited by S aid is the Andalusians: he refers to

69 of them. It is to be noted, however, that the vast majority of those cited

were proficient in the mathematical sciences and logic. Very few are named who

mastered the physical sciences and metaphysics. As a matter of fact, S aid him-

self mentions this explicitly: As far as natural science (al-ilm al-tab) and

metaphysics (al-ilm al-ilah) are concerned, no one in al-Andalus showed any

great interest (inaya) in them. 15 The same applies to medicine. S aid says: As

far as medical science is concerned, there was no one in al-Andalus who mas-

tered it completely or was able to equal any of the ancients. 16 This corresponds

very well with the sciences that we know were translated in Spain in the first

half of the 12th century, during the crucial beginning phase of the translation

movement: almost no physics, metaphysics, or medicine. This outlook presented

by S aid, written in Toledo in 1067 - less than twenty years before the re-

conquest of that city -, was shared by his townspeople, and that is the outlook

that one can also observe in the Arabic-Latin translators. We find striking con-

firmation of this in a statement by Daniel of Morley who says, upon his return

13 I will cite the translation by Pellat, Ibn H azm (nt. 11), 91: Malgre la distance qui separe notre

pays de la source ou jaillit la science et tout eloigne quil soit de la demeure des savants, nous

avons pu citer un tel nombre douvrages dus a la plume de ses habitants que lon en chercherait

en vain lequivalent en Perse, a al-Ahwaz, aux Diyar Mudar, aux Diyar Raba, au Yemen ou en

Syrie, bien que ces pays soient proches de lIrak, qui est le centre ou emigrent lintelligence et

les grands esprits, le rendez-vous des connaissances et des savants.

14 See M. G. Balty-Guesdon, Al-Andalus et lheritage grec dapres les Tabaqat al-umam de S aid

al-Andalus, in: A. Hasnaoui/A. Elamrani-Jamal/M. Aouad (eds.), Perspectives arabes et medi-

evales sur la tradition scientifique et philosophique grecque, Leuven-Paris 1997, 331-342.

15 S aid al-Andalus, Kitab Tabaqat al-umam, ed. L. Cheikho, Beirut 1912, 77; French translation

by R. Blachere, Livre des Categories des Nations, Paris 1935, 142.

16 S aid, ibid., 78; Blachere, ibid., 143.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

8 Dimitri Gutas

to England from Spain late in the 12th century, that at present the instruction

of the Arabs [] consists almost entirely of the arts of the quadrivium 17. I

will return later (in Section IV) to Daniels views about the Muslims; for the

time being it is enough to point out that Daniels statement is not true, of

course, but Daniel thought that it was because the choices for translation that

had been made in Spain up to the time of his visit had been preponderantly of

books of the quadrivium, since that was the secular Arabic Andalusian curricu-

lum, as S aid informs us. Finally, of particular significance is S aids incorpora-

tion of the Jews in his classificatory historical scheme: the sciences culminate

with the Muslims and Jews of al-Andalus. This is important evidence for the

self-view of the Jews at the time but also for how the Muslims viewed them,

and it accords well with the major role played by Jewish scholars in the transmis-

sion process from Arabic into Latin.

The Andalusocentric attitude of Ibn H azm and S aid which I just described

was decisive in the determination of which books to translate in 12th-century

Spain. Thus, although theoretically the entire Arabic corpus could have been

available for translation, the works actually selected were those that were appre-

ciated and cultivated by the Arabic-writing Andalusians of the 11th century.

This explains a number of puzzles about the 12th-century translation movement,

notably the fact that in the sciences, and especially in the fields of the quadrivium

that both S aid al-Andalus and Daniel of Morley talk about, what was translated

was essentially the astronomical and mathematical works of al-Battan and

al-Khwarizm, which were already out-dated and surpassed in the Islamic

world 18; by the 12th century scientists in the East had left behind such works.

What does this indicate about the selection of books to translate? Haskins had

suggested that in this process of translation and transmission accident and

convenience played a large part. No general survey of the material was made,

and the early translators groped somewhat blindly in the mass of works suddenly

disclosed to them 19, while more recently Charles Burnett took another ap-

proach: for the early 12th-century translations of Adelard and Hermann of Ca-

rinthia he said: The Arabic works which were singled out for translation either

filled gaps in knowledge of which Latin readers were aware, or fitted in with

the kind of philosophy they were sympathetic towards. 20 These suggestions

are all to a certain extent valid, though I doubt that they are of primary impor-

tance; rather I would put the matter differently: it was not so much the blind

groping, lack of awareness, or philosophical leanings of the Latin scientists and

17 Doctrina Arabum, que in quadruvio fere tota existit ; the passage is in Daniels ,Philosophia, cited

by Ch. Burnett, The Institutional Context of Arabic-Latin Translations of the Middle Ages: A

Reassessment of the ,School of Toledo, in: O. Weijers (ed.), Vocabulary of Teaching and Re-

search between Middle Ages and Renaissance, Turnhout 1995, 214-222, here: 218.

18 D. A. King, Reflections on Some Studies on Applied Science in Islamic Societies (8th-19th

Centuries), in: Islam and Science 2 (2004), 43-56, here: 53.

19 C. H. Haskins, Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science, Cambridge, Mass. 21927, 18.

20 Ch. Burnett, Hermann of Carinthia, De Essentiis, Leiden 1982, 21.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 9

translators that were responsible for the selection of outdated books, but the

leanings and Andalusian bias of the Arabic ,experts and native informants

whom the Latin scholars and translators consulted. For the translations done in

Spain in the 12th century were done on the basis of Arabic manuscripts available

in Spain at that time, and upon the recommendation, apparently, of such local

experts, all of whom naturally must have shared the Andalusocentric bias we

see in Ibn H azm and S aid.

This is best illustrated by an example drawn from an early 13th-century deci-

sion of a book to translate, the astronomy of the Andalusian al-Bitrug (the

Latin Alpetragius). Michael Scot completed his translation of al-Bitrug as late

as 1217 21 - late in the sense that the Arabic-Latin translation movement had

been going on for over a century, during which time Ptolemys ,Almagest had

already been translated. What was the purpose in translating the curiously ana-

chronistic and, for its time, unscientific treatise of al-Bitrug 22? Haskins men-

tions that the treatise was of considerable importance as a source of Aristo-

telian cosmology in the thirteenth century 23. This it certainly was, but I doubt

that this was the reason why it was translated, i. e., so that it would become a

source for Aristotelian cosmology; I would rather think that al-Bitrug was trans-

lated because he represented Andalusian astronomy over other astronomy, that

of the Eastern Arabs and even of Ptolemy, and Michael Scot was translating on

that date in Toledo for Toledan patrons and on the advice, apparently, of Toled-

ans. The choice of an astronomical book to translate manifestly was not his;

when later in life, while in Sicily, he composed his own work on astrology, the

,Liber introductorius, the astronomy he presented there was not that of al-

Bitrug but of al-Fargan and the ,Almagest 24.

The same Andalusian bias can be observed in the philosophical works trans-

lated into Latin in 12th-century Spain 25. First of all it should be noted, as also

can be gleaned from the implications of the texts of both Ibn H azm and S aid,

that philosophy made its appearance late in al-Andalus and when it did appear

it had a profile very different from that in the East. The first philosopher of

note was Ibn Bagga (Avempace) in the first half of the 12th century ( 1139),

and he mostly engaged in rewriting and commenting on Alfarabi. Al-Kind ( af-

ter 870) also was known in al-Andalus, and indeed to Ibn H azm, for we have a

criticism of al-Kinds metaphysics by his pen 26. If we now look at the Latin

21 Cf. Haskins, Studies (nt. 19), 273-277.

22 For the nature of al-Bitrugs astronomy see A. I. Sabra, The Andalusian Revolt against Ptolem-

aic Astronomy: Averroes and al-Bitruj, in: E. Mendelsohn (ed.), Transformation and Tradition

in the Sciences, Cambridge 1984, 133-153.

23 Haskins, Studies (nt. 19), 277.

24 Cf. ibid., 288.

25 For a complete list see Ch. Burnett, Arabic into Latin: The Reception of Arabic Philosophy

into Western Europe, in: P. Adamson/R. Taylor (eds.), Cambridge Companion to Arabic Phi-

losophy, Cambridge 2005, 370-404, list at 391-404.

26 See H. Daiber, Die Kritik des Ibn H azm an Kinds Metaphysik, in: Der Islam 63 (1986), 284-

302.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

10 Dimitri Gutas

translations of philosophical texts in 12th-century Spain, we see a reflection of

the situation on the Andalusian side. In the first place, until well after the middle

of that century and the appearance of the works of Gerard of Cremona and

Gundissalinus, there are virtually no translations of philosophical texts by the

early translators - Adelard of Bath and Hugo of Santalla and Robert of Ketton

and Hermann of Carinthia, etc. -, a lack of interest in philosophy reflecting

that of Andalusian scholars in general. As far as we can tell, there is only the

essay by Qusta b. Luqa, ,On the Difference between the Spirit and the Soul,

translated by John of Seville 27. The climate slightly changed only with the ap-

pearance on the scene, in Toledo, of Gerard of Cremona and Gundissalinus in

the 50s and 60s of the 12th century, both of whom translated philosophical

texts. They translated al-Kind and Alfarabi, predominantly, though of al-Kind

only some works on natural science and not the Neoplatonic treatises on first

philosophy and the One, works that we consider hallmarks of the Arabic al-

Kind; and of Alfarabi they translated quite a few varied treatises on logic, ethics,

physics, and the classification of the sciences, but again, not the major Neopla-

tonic emanationist treatises like ,The Principles of the Opinions of the Inhabi-

tants of the Excellent City and ,The Principles of Beings - choices that clearly

reflect Arabic Andalusian tastes in philosophy, especially in Alfarabi. This is also

indicated by the highly selective and diffident, one could almost say, translations

of Avicenna by Gundissalinus and some others; Gundissalinus, in any case, is

known to have been influenced in his selection of philosophical material to

translate by his native informant, Avendauth (Ibrahm b. Dawud) 28. Averroes,

who was writing his commentaries in Cordoba at the same time that Gundissali-

nus and Gerard were translating philosophical treatises in Toledo, echoed this

distaste for Avicenna - indeed one could characterize Averroes work as moti-

vated by his reaction as much to Avicenna as to al-Gazzal. By the same token,

is it just a coincidence that the first large-scale Arabic-Latin translations of philo-

sophical texts were being done in Toledo at the same time that Averroes was

himself engaged in furious philosophical activity in Cordoba, commenting on

Aristotle? This is not the place to go into the history of Arabic philosophy in

al-Andalus, but clearly any general assessment of it must take seriously into

consideration the 12th-century translations of philosophical texts into Latin and

27 It should be added that the translation of this work needs explanation in the context of the

translations in Spain in the first half of the 12th century. I have not seen the Ph. D. dissertation

of Judith Wilcox, The Transmission and Influence of Qusta ibn Luqas On the Difference

between Spirit and the Soul (City University of New York 1985), so I do not know whether

she dealt with the issue; in general, and following the lead of Thomas Ricklin, Der Traum der

Philosophie im 12. Jahrhundert. Traumtheorien zwischen Constantinus Africanus und Aristo-

teles (Mittellateinische Studien und Texte XXIV), Leiden 1998, it may have had something to

do with the new understanding of the body-soul relationship that was ushered into Latin scholar-

ship through the creative translations of Constantinus Africanus.

28 See Ch. Burnett, Translation and Transmission of Greek and Islamic Science to Latin Christen-

dom, in: The Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2: D. C. Lindberg/M. H. Shank (eds.), Science

in the Middle Ages, forthcoming.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 11

the rationale behind their selection, something which is lacking in accounts of

Andalusian philosophy.

The translators of the 12th century, then, looked for their Arabic manuscripts

in al-Andalus and were influenced by Andalusian tastes and biases in their selec-

tion of works to translate. This would indicate to me that one of the reasons, if

not the main reason, that they engaged in this translation movement was to

imitate the Andalusians and appropriate their knowledge - become like them,

essentially. That this was among their motivations rather than any desire to

improve their ,scientific knowledge or ,advance science is also indicated by the

fact that they selected outdated works to translate and did not look around the

Islamic world for the latest developments in the sciences concerned. Because,

theoretically, they had an excellent opportunity: large parts of Syria and Palestine

were in the hands of the Crusaders at the beginning of the 12th century, and in

Syria, at that time, there could have been found almost the entire production of

Arabic scholarship from the beginning of Islam. But, paradoxical as it might

seem, and without going into details 29, Syria was not mined by the Latins for

its manuscript treasures, in spite of, or rather exactly because of the fact that

parts of Syria and Palestine were under Crusader occupation. We have reports

of pillaging, looting and destruction of libraries by the Crusaders, but not of

their wholesale acquisition or purchase 30. Some cultural contacts between East

and West there certainly were, but their overall contribution to the Arabic-Latin

translation movement is far from being evidently substantial, despite the best

efforts of some recent studies 31.

Thus, the translation movement of the 12th century in Spain appears to have

been a local affair, with local concerns and local ideological motivations. It is

29 Adelard of Bath presumably was there at about this time, but we have no information that he

sought, much less carried away, any Arabic manuscripts. It is possible that he may have found

there a manuscript of the ,Elements which he translated, but he could have procured that

manuscript just as easily from Spain. Philip of Tripoli and Stephen the Philosopher from Pisa

apparently did find the manuscripts of the works they translated in Syria, but we are not yet

sure if this was exceptionally so. Again, Master Theodore, Frederick IIs philosopher, could have

presumably requested manuscripts to be sent to him in Sicily from his home town Antioch, but

in this we are in the realm of speculation and we have no concrete evidence. Pisa, which had a

quarter in Antioch and apparently must have procured Arabic manuscripts from there, never

developed, apart from some incidental translations, a translation movement like that in Spain

in the 12th century. For all this see the material collected by Ch. Burnett, Antioch as a Link

between Arabic and Latin Culture in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, in: I. Draelants/A.

Tihon/B. van den Abeele (eds.), Occident et Proche-Orient: contacts scientifiques au temps des

croisades (Actes du colloque de Louvain-la-Neuve, 24 et 25 mars 1997), Turnhout 2000, 1-66.

30 See L. Cochrane, Adelard of Bath, London 1994, 33, citing the Damascus Chronicle of Ibn al-

Qalanis in H. A. R. Gibbs translation, London 1932, 89; but cf. S. J. Williams, Philip of Tripolis

Translation of the Pseudo-Aristotelian Secretum Secretorum Viewed within the Context of

Intellectual Activity in the Crusader Levant, in: Draelants e. a. (eds.), Occident et Proche-Orient

(nt. 29), 79-94, here: 84 and note 20.

31 See now the articles collected in Draelants e. a. (eds.), Occident et Proche-Orient (nt. 29), and

the Introduction, i-iv, with references to earlier bibliography.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

12 Dimitri Gutas

the exception that proves the rule, they say, and in this case it is an exceptional

case that would seem to support this statement. If the Latin translators in Spain

looked no farther afield than al-Andalus for their manuscripts and their knowl-

edge, this does not mean that others - very few others - did not, like Ramon

Marti in the 13th century. If at the one extreme we have someone like Daniel

of Morley who thought that the Arabs had written only on the quadrivium, then

at the other extreme we have someone like Ramon Marti 32 who learned Arabic

well enough to read widely in Arabic sources and acquainted himself with the

religious literature of his time. In his works he quoted not only from al-Gazals

,Autobiography (al-Munqid ) 33, a work not normally known in Latin, but also,

and quite astonishingly, from Fahr al-Dn al-Razs al-Mabah it al-masriqya

(which he called, very appropriately, ,Liber investigationum orientalium). But

Ramon Marti was, as I said, one of the very few exceptions. The Latin translators

of the 12th century clearly had other priorities in mind than the discovery of the

latest scientific advances in the various fields of the quadrivium, the philosophy,

or indeed the philosophical theology of the Muslims.

II.

The first aspect of the question, What was there in Arabic for the Latins to

receive? which I just discussed cannot be answered satisfactorily unless we take

into account also the related question, What was there in Greek for the Latins

to receive? In every case where the former question is asked so also must be

the attendant one, viz, whether there was any alternative to translating from the

Arabic, i. e., whether any Greek manuscripts and translators who knew Greek

were readily available. This is the technical, factual aspect, of the question, about

which surveys of Greek manuscripts in Spain and generally in Europe will in-

form, but I am not interested in this aspect of the problem. What is significant,

rather, in this connection, is to understand the attitudes behind the choice of

translating from the Greek as opposed to the Arabic. Before I discuss the signifi-

cance of the choice, let me give a brief impressionistic picture of what normally

happened.

A statistical analysis of the actual choices made about which books to translate

will inform us relatively accurately about culturally conditioned motivations and

preferences. And naturally, such examination of actual choices made will be

specific as to the sciences concerned; we cannot mix together indiscriminately

information about different sciences. We do not as yet have complete statistics

32 Cf. M.-Th. dAlverny, Algazel dans lOccident latin, in: Academie du Royaume du Maroc, session

de novembre 1985, Rabat 1986, 125-146; repr. in her La transmission des textes philosophiques

et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994, no. VII, 11.

33 In his Pugio Fidei adversus Mauros et Judaeos; see V. M. Poggi, Un classico della spiritualita

musulmana, Rome 1967.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 13

separately for all disciplines, but let me give one example from one discipline

for which we do, mathematics (in the broad sense of the quadrivium, excluding

music). In a significant article, Richard Lorch gave the numbers of how many

works on mathematics were translated from Arabic and how many from Greek,

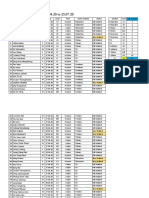

as follows:

Greek works translated from Arabic into Latin: 16, three of them in more

than one version (Euclids ,Elements, Theodosius ,Spherics, Archimedes ,Di-

mensio Circuli).

Greek works translated directly from Greek: 6, if we exclude the versions by

William of Moerbeke, which came later, at a time when the dynamics of the

question Greek versus Arabic had changed from the original one in the 12th

century, which is our concern here.

Original Arabic works on mathematics translated into Latin: 34 (six of them

in more than one version) 34.

What this statistics indicates is this: in the 12th century, European scholars

preferred to translate Greek mathematical works from an Arabic intermediary

translation almost three times more than from the original Greek (16:6), and, in

addition, they preferred original Arabic works on mathematics almost six times

as much as they did the original Greek works (34:6). Such overwhelming ratios

in favor of Arabic texts, both of Arabic translations from the Greek and of

original Arabic works, cannot be accidental: the preference was deliberate and

indicates the cultural predilection.

Let me continue with some further facts along these lines. The famous

Michael Scot finished his translation of Aristotles ,Zoology while still in Toledo,

early in the 13th century, on the basis of the Arabic version. In comparison with

the Greek text, Michaels translation was clearly deficient, yet it remained in

constant use until the fifteenth century 35. Why was there not sought another

translation, from the Greek?

And again: Averroes Middle Commentary on the ,Poetics was translated by

Hermann the German in Toledo by 1256, while William of Moerbekes transla-

tion of the ,Poetics itself from the Greek original was finished some twenty

years later, in 1278. But it was Hermanns translation of Averroes work that

was used and quoted in medieval literature rather than Williams translation of

Aristotle: Hermanns work survives in 24 manuscripts, Williams in only two 36.

What all this evidence taken together indicates is that the order of preference

of source material to translate was, first, Arabic works popular or appreciated

in al-Andalus, second, Arabic works from the East, and only third, Greek works.

34 See the tables in R. Lorch, Greek-Arabic-Latin: The Transmission of Mathematical Texts in the

Middle Ages, in: Science in Context 14 (2001), 313-331, here: 316-319.

35 Cf. Haskins, Studies (nt. 19), 278.

36 Cf. H. A. Kelly, Aristotle-Averroes-Alemannus on Tragedy: The Influence of the ,Poetics on

the Latin Middle Ages, in: Viator 10 (1979), 162-209, here: 161-162.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

14 Dimitri Gutas

This Andalusocentrism and relative disdain of Eastern Arabic accomplishments

is consistent with the perspective presented by S aid al-Andalus in his ,Catego-

ries of the Nations 37, while the even lesser demand for works in Greek is

indicative of the lack of appreciation of them by Europeans, for reasons yet to

be studied and socially analyzed. Incidentally, and not at all irrelevantly, it should

be added that this negative sentiment vis-a-vis the original works in Greek was

not restricted to the Latin world. The Byzantines themselves, when they started

becoming interested in ancient science again in the ninth century - as a direct

result of the Graeco-Arabic translation movement, I claimed -, preferred

translating Arabic works into Byzantine Greek rather than simply reading the

originals in Greek and avoiding translation altogether 38!

There is clearly a historical problem here. The question of which sources to

translate, Greek or Arabic, was doubtless a matter of cultural contest and self-

identification for the Middle Ages; studying it gives us an opportunity to dis-

cover the motives and ideology behind the translation movements, both Arabic-

Latin and Greek-Latin - indeed the politics of the choice, Greek or Arabic,

appears to have been very important in the formation of popular and scholarly

ideologies in the Middle Ages from the 12th century onwards. We are well in-

formed about the politics of learning Greek as it manifested itself in the Refor-

mation and beyond, and the role it played in the public career of someone like

Erasmus - I am reminded of a recent study by Simon Goldhill with the won-

derful title, ,Who Needs Greek? (and the subtitle, ,Contests in the Cultural

History of Hellenism, Cambridge 2002). We need similar studies for the Middle

Ages, and not only for Greek but also for Arabic 39.

III.

My third question, what the Latins were able to translate, from the perspective

I want to raise it, has been treated only tangentially in studies such as those by

dAlverny on translations ,a quattro mani or, in her terms, ,traductions a deux

interpretes 40, and in other studies of individual translations and their accuracy 41.

37 Cf. Balty-Guesdon, Al-Andalus (nt. 14), 342.

38 Cf. D. Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in

Baghdad and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries), London-New York 1998,

175-186. For a brief discussion of the Byzantine preference, in the case of medicine, for Arabic

works over Galens Greek texts see my review of Mavroudi in: Byzantinische Zeitschrift 97

(2004), 610.

39 See on this subject the contribution to this volume by Charles Burnett, 22-31.

40 M.-Th. dAlverny, Les traductions a deux interpretes, darabe en langue vernaculaire et de langue

vernaculaire en latin, in: Traduction et traducteurs au Moyen Age (Colloques internationaux du

CNRS, IRHT 26-28 mai 1986), Paris 1989, 193-206; repr. in her La transmission des textes

philosophiques et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994, no. III.

41 See, e. g., Ch. Burnett, The Strategy of Revision in the Arabic-Latin Translations from Toledo:

The Case of Abu Mashars On the Great Conjunctions, in: J. Hamesse (ed.), Les Traducteurs

au travail: leurs manuscrits et leurs methodes, Turnhout 2001, 51-113, 529-540.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 15

But the questions that I need to have answered are, how much Arabic the

translators knew, where they learned it, and most importantly, how much they

relied on ,native informants for their versions. For let us consider: apart from

the Jews of Spain, both orthodox and converted, like Petrus Alfonsi, John of

Seville, and Abraham ibn Ezra, who can be expected to have grown up speaking

and reading Arabic, most (if not all?) of the other, Christian, translators worked

through intermediary native informants: Gundissalinus worked with ,Avendauth

israelita; Plato of Tivoli with Savasorda; Michael Scot with ,Abuteus levita; the

famous translation project of Peter the Venerable employed a certain Muh am-

mad; and even the great Gerard of Cremona worked with Gallipus (Galib) 42. It

would be worth our while to draw up as complete an inventory as possible of

these ,native informants, who, to call them by their real name, were nothing

else but shadow translators.

Very much to the point is the case of Hermann the German, who confessed

to Roger Bacon that he did not know Arabic well and that he was much more

of an assistant in the translations rather than a translator himself, because he

employed Arabs in Spain who were the real authors of his translations 43. Now

it is to be noted that Hermann is saying this some time in the middle of the

13th century (Bacon, who is reporting this statement, adding that he used to

know Hermann well, wrote his ,Compendium studii philosophiae in 1272) 44.

That is almost a century and a half after the first translations of the Arabic-

Latin movement at the beginning of the 12th century. Why was there no rush

in Europe for translators to improve their Arabic, as there was in Baghdad with

regard to Greek, where, after the initially clumsy Graeco-Arabic translations, the

generation of H unain achieved a very high level of competence in Greek 45?

So there is another serious problem here, for, looked at closely, the evidence

we have even about allegedly skilled translators raises many questions. Let us

take Gerard of Cremona again, a perfect example to make the case: he translated

the ,Almagest in 1175 and he employed for this translation the services of his

42 Cf. Haskins, Studies (nt. 19), 15, 18; dAlverny, Les traductions (nt. 40), 198.

43 Magis fuit adiutor translationum quam translator, quia Sarascenos tenuit secum in Hispania qui fuerunt in

suis translationibus principales; quoted in Kelly, Aristotle-Averroes-Alemannus (nt. 36), 173, nt. 46,

quoting from Bacons ,Compendium studii philosophiae, c. 8, 472, in: J. S. Brewer (ed.), Opera

quaedam hactenus inedita, London 1859.

44 Cf. Kelly, Aristotle-Averroes-Alemannus (nt. 36), 172. Bacon, who apparently was under no

illusion about the translators competence, repeated his criticisms of them on numerous occa-

sions; see Ch. Burnett, Translating from Arabic into Latin in the Middle Ages: Theory, Practice,

and Criticism, in: S. G. Lofts/Ph. Rosemann (eds.), Editer, traduire, interpreter: Essais de metho-

dologie philosophique, Louvain-Paris 1997, 55-78, here: 71 and nt. 42.

45 Cf. Gutas, Greek Thought (nt. 38), 136-141. To make matters worse for the lack of expertise

in Arabic by the Latins, it appears that even translators working in Antioch did not have a

proper command of technical Arabic. Stephen the Philosopher says in his introduction to the

,Regalis dispositio that at present [] we have no one who knows both languages [scil.

Arabic and Latin] ,well enough (Burnett, Antioch [nt. 29], 36); cf. Williams, Philip of Tripolis

Translation (nt. 30), 85-89.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

16 Dimitri Gutas

helper Galippus. Now this was made 13 years before Gerards death, when he

had been translating from the Arabic already for some twenty years; and this

was only the ,Almagest, a highly technical text, but easy once one knows the

mathematics of it; the Arabic itself could not have been any problem - one

can well imagine if this had been a literary text in Arabic! Hadnt Gerard learned

any Arabic? Or was he stupid? The answers of course are, yes, he had learned

some Arabic but not well, and no, he wasnt stupid; what therefore can account

for this evidence is that he didnt learn Arabic well enough because he didnt

need to; as long as he could find shadow translators like Galippus to help him

out - essentially do his work for him - he didnt need to spend the time and

energy to learn proper Arabic. He could employ his time much more gainfully

polishing the style of the versions in broken Latin (or vernacular) given to him

by his shadow translators. But this state of affairs means that the translations

were actually made by the shadow translators, and unless we know what they

knew and how well they knew it we will not be in a better position to answer

the questions I am asking.

And if the unidentified shadow translators in the employ of the Latin so-

called translators played such a major role in the translation process, how far-

reaching was their influence in the determination of what books to translate?

Even assuming that the Latin ,translator had in mind, or was requested, to

translate a particular book, if his shadow translators were not versed in that

particular science, could he have gone through with the project? It seems not.

Again in the case of Hermann the German, he says in the introduction to his

translation of the ,Rhetoric that both the ,Rhetoric and the ,Poetics [] have

been more or less neglected up to his day even by the Arabs, because of their

difficulty; and that he was scarcely able to find a single person to give him

serious help in interpreting them 46. Hermanns claim, for the Arabic side, is

just wrong, for Averroes wrote epitomes and middle commentaries on both

these works by Aristotle a century earlier, to say nothing of the other previous

works on the ,Rhetoric and ,Poetics in Arabic 47; so what Hermanns allegations

mean is that he is conveying his informants views on the subject. Thus, either

his informants - that is, his shadow translators - were ignorant of the many

Arabic works on the ,Rhetoric and ,Poetics, or they were not sufficiently

schooled themselves to dare tackle these subjects, or, and perhaps most likely,

they were not being paid enough for the amount of trouble to which they would

have to go to to translate these treatises; if they were more at home, say, with

mathematics, it would have been easier for them to translate mathematical works

46 Kelly, Aristotle-Averroes-Alemannus (nt. 36), 173.

47 On the ,Rhetoric in particular see now the magisterial work by M. Aouad, Averroes, Com-

mentaire moyen a la Rhetorique dAristote, Paris 2002; for thorough reviews of Arabic works

on both the ,Rhetoric and ,Poetics see M. Aouad, La Rhetorique. Tradition syriaque et arabe,

in: Dictionnaire des Philosophes Antiques, Paris 1989, I, 455-472, Supplement, 219-223; and

H. Hugonnard-Roche, La Poetique. Tradition syriaque et arabe, in: ibid., Supplement, Paris 2003,

208-218.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 17

rather than the ,Rhetoric and ,Poetics, if they were being paid the same amount

for both types of translations. And thus, if the education and cultural outlook

(and, a fortiori, the pay scale) of the native informants are also factors in what

was translated 48, we need to investigate with diligence these shadow translators.

IV.

All of this - the discussion of the availability for translation of Arabic and

Greek works to the 12th-century translators, their criteria of selection, and their

reliance on shadow translators for their work - brings us inevitably to the big

question, why the translation movement, both from Arabic and from Greek,

started and thrived at all. But this may not be the right place to discuss the

social, political, and ideological causes of this translation movement. Dag Hasse

made a wonderful start in a mini essay which he published in the ,Neue Zrcher

Zeitung three years ago 49, Thomas Ricklin slightly before that gave some tanta-

lizing hints in the epilogue of his work on Latin dreams 50, and I am sure others

more knowledgeable than I in medieval European history and society will follow.

But since I offered earlier a hint myself by suggesting that the Arabic-Latin

translation movement proper began in the early 12th century in northern Spain

and that it was, above all, a local movement, a movement that eventually ac-

quired a pan-European significance, I will conclude by making a further point

in this direction while drawing on my experience with the Graeco-Arabic transla-

tion movement that took place a few centuries earlier.

Looking at the two translation movements, the Graeco-Arabic and the Ara-

bic-Latin one 51, we can see numerous differences between the two. In my view,

the most significant difference, and the one that led me to the realization of the

importance of Baghdadi politics and ideologies for the Graeco-Arabic transla-

tions and may lead to an equal appreciation of the same factors in the Arabic-

Latin translations, has to do with the relative stand of the two civilizations at

the time of the translations: in the case of the Graeco-Arabic transmission,

Islam was at the time of the early Abbasids the high civilization in comparison

with both Byzantium and the Europe of Charlemagne, and Islams turning to-

ward classical antiquity (and its Iranian Sasanian version, as I argued) meant the

willful resuscitation of a bookish tradition and indicated a kind of emulation

that consisted of comparing itself to and learning from past civilizations and

48 And thus the translators themselves did not exercise as much ,lively initiative or display as much

creativity in what they selected to translate as one is led to believe from T. Burtons romantic

portrayal of them in: M. R. Menocal/R. S. Scheindlin/M. Sells (eds.), Michael Scot and the

Translators, in: The Literature of Al-Andalus, Cambridge 2000, 404-411, here: 407-408.

49 D. N. Hasse, Griechisches Denken, muslimische und christliche Interessen: Kulturtransfer im

Mittelalter, in: Neue Zrcher Zeitung, 18/19 August 2001, 78.

50 Ricklin, Der Traum der Philosophie (nt. 27).

51 And possibly also the Greek-Latin one, though this has to be verified independently.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

18 Dimitri Gutas

not from any currently in existence. Whereas in the case of the Arabic-Latin

transmission, Latin Europe was manifestly inferior to Islam in intellectual, eco-

nomic, and military terms, and thus this transmission can be ascribed to the

natural tendency, on the part of the Latin world, to follow the path of and

imitate the higher civilization - in essence, become the other civilization and

acquire for itself the glory and prestige that belonged to the Arabs and Islam in

general.

What this means, in terms of trying to understand the two movements as

historically significant processes ideologically responding to the needs of the

societies that generated them, is that the Graeco-Arabic translation movement

is rooted in, and is an expression of, internal political and social developments

in early Abbasid society (as I argued), for it could bring no immediate benefits

in the international political arena but was intended for internal ideological con-

sumption; while the Arabic-Latin translation movement must be seen in the

context of international politics and as an expression of ideological tendencies

that developed because of that.

To illustrate this statement I will cite as example a rather well-known passage

by Daniel of Morley to which I referred earlier, who visited Spain in search of

knowledge, as he claims, in the second half of the 12th century. After mentioning

his visit to Spain and his return to England with a precious collection of

books, he says:

Let no one be disturbed that, as I treat of the creation of the world, I call upon the

testimony not of the catholic fathers, but of the pagan philosophers, for, although the

latter are not among the faithful, some of their words ought nevertheless to be taken

over by our instruction when they are full of [Christian] faith. We too, who have been

mystically liberated from Egypt, have been ordered by the Lord to borrow from the

Egyptians their gold and silver equipment to enrich the Hebrews. Let us, then, in

conformity with the Lords command and with His help, borrow from the pagan

philosophers their wisdom and eloquence, and thus let us rob those infidels to enrich

ourselves in faith with their booty. 52

This passage is remarkable for the way in which it portrays the Europeans in

comparison with the Muslims. Daniel says that we, meaning the Christians of

Europe, have been mystically liberated from Egypt, and continues with the

metaphor from the Biblical Exodus, with the Christians being seen as the He-

brews and the Muslims as the Egyptians. But what is he actually referring to by

being mystically liberated from the Muslims? Given the international political

scene in the second half of the 12th century when Daniel was writing, this could

only refer on the one hand to the Crusader conquest of parts of the Holy Land

and on the other to the reconquest of parts of Spain, and especially of Toledo,

the city he had visited. And indeed, the wars of reconquest of Spain acquired a

new character in the 12th century: they were transformed into a crusade by the

52 G. Maurach, Daniel von Morley, ,Philosophia, in: Mittellateinisches Jahrbuch 14 (1979), 204-

255, here: 212-213.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 19

Popes who began to grant remission of sins to those who participated in the

fight against the Muslims in al-Andalus 53. These military and political advances

on the part of the Christians in Spain and the climate newly enhanced with

crusader ideology created an atmosphere in which cultural plunder, as Daniel

describes it, could be envisaged as well deserved spoils. The military conquest

of cities like Saragossa and Toledo by itself could not bring about - for the

victorious Christians of these cities and for the local bishops who led them and

sponsored the translations - the prestige which these cities enjoyed under Mus-

lim domination, because what was lacking was the cultural component. The

translations, and the appropriation of Muslim science and philosophy - but not

any Muslim science and philosophy, or all, or the most advanced Muslim science

and philosophy, but specifically the science and philosophy of al-Andalus, and

even more narrowly, those of Toledo and Saragossa - produced the required

addition of cultural prestige.

If this approach is going to be at all fruitful, it will need the micro-study of

the Muslim and Christian societies of the re-conquered cities - it will need the

study of the social implications of the translations themselves, of the eventual

expansion of such ideologies to the rest of Europe, and of the participation, at

first by proxy and then by deed, of the other Europeans in the newly acquired

glory and prestige of the Spanish cities.

Bibliog raphy

M. Abattouy/J. Renn/P. Weinig, Transmission as Transformation: The Translation Movements in

the Medieval East and West in a Comparative Perspective, in: Science in Context 14 (2001), 1-

12.

M.-Th. dAlverny, Algazel dans lOccident latin, in: Academie du Royaume du Maroc, session de

novembre 1985, Rabat 1986, 125-146; repr. in her La transmission des textes philosophiques

et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994, no. VII.

Ead., Les traductions a deux interpretes, darabe en langue vernaculaire et de langue vernaculaire en latin,

in: Traduction et traducteurs au Moyen Age (Colloques internationaux du CNRS, IRHT 26-28 mai

1986), Paris 1989, 193-206; repr. in her La transmission des textes philosophiques et scientifiques au

Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994, no. III.

Ead., Pseudo-Aristotle, De Elementis, in: J. Kraye e. a. (eds.), Pseudo-Aristotle in the

Middle Ages: The Theology and Other Texts, London 1986, 63-83; repr. in her La transmission

des textes philosophiques et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994,

no. IX.

Ead., Translations and Translators, in: R. L. Benson/G. Constable (eds.), Renaissance and Renewal

in the Twelfth Century, Cambridge, Mass. 1982, 421-462; repr. in her La transmission des textes

philosophiques et scientifiques au Moyen Age, ed. by Ch. Burnett, Aldershot 1994, no. II.

M. G. Balty-Guesdon, Al-Andalus et lheritage grec dapres les Tabaqat al-umam de S aid al-Anda-

lus, in: A. Hasnaoui/A. Elamrani-Jamal/M. Aouad (eds.), Perspectives arabes et medievales sur

la tradition scientifique et philosophique grecque, Leuven-Paris 1997, 331-342.

53 See now the fully documented account of this development in: J. F. OCallaghan, Reconquest

and Crusade in Medieval Spain, Philadelphia 2003.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

20 Dimitri Gutas

M. Barber, The Two Cities: Medieval Europe 1050-1320, London 1992.

R. Blachere, Kitab tabak at al-umam (Livre des Categories des Nations), Paris 1935.

G. Braga, Le prefazioni alle traduzioni dallarabo nella Spagna del XII secolo: la valle dell Ebro, in:

B. Scarcia Amoretti (ed.), La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel medio evo europeo, Rome

1987, 323-354.

Ch. Burnett, A Group of Arabic-Latin Translators Working in Northern Spain in the Mid-12th

Century, in: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 1977, 62-108.

Id., Antioch as a Link between Arabic and Latin Culture in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries,

in: I. Draelants/A. Tihon/B. van den Abeele (eds.), Occident et Proche-Orient: contacts scienti-

fiques au temps des croisades (Actes du colloque de Louvain-la-Neuve, 24 et 25 mars 1997),

Turnhout 2000, 1-66.

Id., Divination from Sheeps Shoulder Blades: A Reflection on Andalusian Society, in: D. Hook/B.

Taylor (eds.), Cultures in Contact in Medieval Spain: Historical Essays Presented to L. P. Harvey

(Medieval Studies 3), 1990, 29-45.

Id., Hermann of Carinthia, De Essentiis, Leiden 1982.

Id., The Astrologers Assay of the Alchemist: Early References to Alchemy in Arabic and Latin

Texts, in: Ambix 39 (1992), 103-109.

Id., The Coherence of the Arabic-Latin Transmission Program in Toledo in the Twelfth Century,

in: Science in Context 14 (2001), 249-288.

Id., The Institutional Context of Arabic-Latin Translations of the Middle Ages: A Reassessment of

the ,School of Toledo, in: O. Weijers (ed.), Vocabulary of Teaching and Research between Middle

Ages and Renaissance, Turnhout 1995, 214-222.

Id., The Strategy of Revision in the Arabic-Latin Translations from Toledo: The Case of Abu

Mashars On the Great Conjunctions, in: J. Hamesse (ed.), Les Traducteurs au travail: leurs

manuscrits et leurs methodes, Turnhout 2001, 51-113, 529-540.

Id., Translation and Transmission of Greek and Islamic Science to Latin Christendom, in: The

Cambridge History of Science, vol. 2: D. C. Lindberg/M. H. Shank (eds.), Science in the Middle

Ages, forthcoming.

Ch. Burnett/E. Kennedy, The Works of Petrus Alfonsi: Questions of Authenticity, in: Medium

Aevum 66 (1997), 42-79.

P. Carusi, Teoria e sperimentazione nell alchimia medioevale nel passaggio da Oriente a Occidente,

in: B. Scarcia Amoretti (ed.), La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel medio evo europeo, Rome

1987, 355-377.

H. Daiber, Lateinische bersetzungen arabischer Texte zur Philosophie und ihre Bedeutung fr die

Scholastik des Mittelalters, in: Rencontres de cultures dans la philosophie medievale, Louvain-la-

Neuve-Cassino 1990, 203-250.

P. G. Dalche, Epistola Fratrum Sincerorum in Cosmographia: Une traduction latine inedite de la

quatrieme Risala des Ihwan al-S afa, in: Revue dHistoire des Textes 18 (1988), 137-167.

M. Folkerts, Regiomontanus Role in the Transmission and Transformation of Greek Mathematics,

in: F. J. Ragep/S. P. Ragep (eds.), Tradition, Transmission, Transformation, Leiden 1996, 89-

114.

D. Gutas, Greek Thought, Arabic Culture: The Graeco-Arabic Translation Movement in Baghdad

and Early Abbasid Society (2nd-4th/8th-10th Centuries), London-New York 1998.

C. H. Haskins, Studies in the History of Mediaeval Science, Cambridge, Mass. 21927.

D. N. Hasse, Griechisches Denken, muslimische und christliche Interessen: Kulturtransfer im Mittel-

alter, in: Neue Zrcher Zeitung, 18/19 August 2001, 78.

D. Hook/B. Taylor (eds.), Cultures in Contact in Medieval Spain: Historical Essays Presented to

L. P. Harvey (Medieval Studies 3), 1990.

G. F. Hourani, The Medieval Translations from Arabic to Latin Made in Spain, in: The Muslim

World 62 (1972), 97-114.

D. Jacquart, The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West, in: R. Rashed, Encyclopedia

of the History of Arabic Science, London 1996, 963-984.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

What was there in Arabic for the Latins to Receive? 21

H. A. Kelly, Aristotle-Averroes-Alemannus on Tragedy: The Influence of the ,Poetics on the Latin

Middle Ages, in: Viator 10 (1979), 162-209.

D. A. King, Reflections on Some Studies on Applied Science in Islamic Societies (8th-19th Centu-

ries), in: Islam and Science 2 (2004), 43-56.

P. Kunitzsch, The Role of al-Andalus in the Transmission of Ptolemys Planisphaerium and Alma-

gest, in: Zeitschrift fr Geschichte der Arabisch-Islamischen Wissenschaften 10 (1995/96), 147-

155.

R. Lemay, Dans lEspagne du XIIe siecle. Les Traductions de larabe au latin, in: Annales. Economies,

Societes, Civilisations 18 (1963), 639-665.

R. Lorch, Greek-Arabic-Latin: The Transmission of Mathematical Texts in the Middle Ages, in:

Science in Context 14 (2001), 313-331.

A. Maieru, Influenze arabe e discussioni sulla natura della logica presso i latini fra XIII e XIV

secolo, in: B. Scarcia Amoretti (ed.), La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel medio evo europeo,

Rome 1987, 243-268.

G. Makdisi, The Model of Islamic Scholastic Culture and its Later Parallel in the Christian West, in:

O. Weijers (ed.), Vocabulaire des colleges universitaires (XIIIe-XVIe siecles), Turnhout 1993,

158-174.

F. Micheau, Science et medecine, lindispensable transmission, in: Autour dAverroes. Lheritage

andalou (Rencontres dAverroes 1), Marseille 2003, 51-58.

J. M. Millas-Vallicrosa, Las mas antiguas traducciones arabes hechas en Espana, in: Convegno di

scienze morali storiche e filologiche. Tema: Oriente ed Occidente nel Medio Evo, Rome 1957,

383-390.

L. Minio-Paluello, Aristotele dal mondo arabo a quello latino, in: LOccidente e lIslam nellalto

medioevo (Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi sull Alto Medioevo XII), Spoleto

1965, 603-637.

Ch. Pellat, Ibn H azm, bibliographe et apologiste de lEspagne musulmane, in: Al-Andalus 19 (1954),

53-102.

D. Pingree, The Diffusion of Arabic Magical Texts in Western Europe, in: B. Scarcia Amoretti (ed.),

La diffusione delle scienze islamiche nel medio evo europeo, Rome 1987, 57-102.

Thomas Ricklin, Der Traum der Philosophie im 12. Jahrhundert. Traumtheorien zwischen Constantinus

Africanus und Aristoteles (Mittellateinische Studien und Texte XXIV), Leiden 1998.

S aid al-Andalus, Kitab Tabaqat al-umam, ed. L. Cheikho, Beirut 1912.

M. Steinschneider, Die Europischen bersetzungen aus dem Arabischen bis Mitte des 17. Jahrhun-

derts, repr. Graz 1956.

Brought to you by | New York University Bobst Library Technical Services

Authenticated

Download Date | 7/7/15 1:53 AM

You might also like

- Summer Internship Project Report (Rajat)Document93 pagesSummer Internship Project Report (Rajat)deepak Gupta75% (4)

- MooeDocument12 pagesMooeRommel SalagubangNo ratings yet

- Schools Swot Guide QuestionsDocument2 pagesSchools Swot Guide QuestionsGuia Marie Diaz Brigino100% (1)

- First Spanish Translation of LXXDocument9 pagesFirst Spanish Translation of LXXAnonymous mNo2N3No ratings yet

- 02 - Scribes and Scholars A Guide To The Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature 3rd EdDocument347 pages02 - Scribes and Scholars A Guide To The Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature 3rd EdWillamy Fernandes100% (5)

- The Sociology of Anthony GiddensDocument248 pagesThe Sociology of Anthony Giddensprotagorica100% (5)

- From Coptic To Arabic in The Christian LDocument22 pagesFrom Coptic To Arabic in The Christian Lthomas.lawendyNo ratings yet

- Hans Helander - Neo-Latin Studies, Significance and Prospects (2001)Document98 pagesHans Helander - Neo-Latin Studies, Significance and Prospects (2001)Anders FernstedtNo ratings yet

- History of Translation: Group: 1. Mei Valentine 2. Muhtiya Maulana 3. Nadana Sabila 4. Widuri IrmaliaDocument8 pagesHistory of Translation: Group: 1. Mei Valentine 2. Muhtiya Maulana 3. Nadana Sabila 4. Widuri IrmaliaWiduri IrmaliaNo ratings yet

- Arabic-Speaking Christians and Toledo, BCT MS Cajón 99.30 in High Medieval SpainDocument39 pagesArabic-Speaking Christians and Toledo, BCT MS Cajón 99.30 in High Medieval SpainThiago RORIS DA SILVANo ratings yet

- Dialnet MontgomeryScottLScienceInTranslation 4925510Document5 pagesDialnet MontgomeryScottLScienceInTranslation 4925510Osama AbdelsalamNo ratings yet

- Science and Philosophy in EuropeDocument15 pagesScience and Philosophy in EuropeMok SmokNo ratings yet

- Arabic Into Medieval Latin PDFDocument38 pagesArabic Into Medieval Latin PDFalamirizaid100% (1)

- Coptic Arabic Renaissance in The MiddleDocument22 pagesCoptic Arabic Renaissance in The Middlethomas.lawendyNo ratings yet

- Alma 2005 63 161Document8 pagesAlma 2005 63 161bosneviNo ratings yet

- Alexander Fidora Et Al. Latin-Into-HebreDocument11 pagesAlexander Fidora Et Al. Latin-Into-HebreRodrigo B. VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Alastair Hamilton The Study of Islam in PDFDocument14 pagesAlastair Hamilton The Study of Islam in PDFyahya333No ratings yet

- History of TranslationDocument1 pageHistory of TranslationvianaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of History of Translation in The Western World - Dec - 2018Document9 pagesAn Overview of History of Translation in The Western World - Dec - 2018Mihir DaveNo ratings yet

- Translation Theories - Chapter 1Document12 pagesTranslation Theories - Chapter 1Saja Unķnøwñ Ğirł0% (1)

- Burnett Charles 2001Document41 pagesBurnett Charles 2001Eva AladroNo ratings yet

- Transmission: Islamic ScienceDocument31 pagesTransmission: Islamic ScienceSavira AfifahNo ratings yet

- The Study of Arabic Philosophy in The Twentieth Century - Dimitri GutasDocument21 pagesThe Study of Arabic Philosophy in The Twentieth Century - Dimitri GutasSamir Al-HamedNo ratings yet

- Gutas The Study of Arabic Philosophy in The 20th Cent-1. 38582366Document22 pagesGutas The Study of Arabic Philosophy in The 20th Cent-1. 38582366gnothiautoNo ratings yet

- Românic: ReviewDocument15 pagesRomânic: ReviewlukaslickaNo ratings yet

- 1 1Document78 pages1 1StrumicaNo ratings yet

- Gutas - The Study of Arabic PhilosophyDocument22 pagesGutas - The Study of Arabic PhilosophyYunis IshanzadehNo ratings yet

- Lectura 1 BacardiDocument7 pagesLectura 1 BacardiClara Bernal PontNo ratings yet

- Humanismo en España. Revisión Crítica. Di CamilloDocument15 pagesHumanismo en España. Revisión Crítica. Di CamilloCarlos VNo ratings yet

- Adrados-Graeca in H.Document8 pagesAdrados-Graeca in H.luciano cordoNo ratings yet

- 3 18 TransmissionDocument30 pages3 18 Transmissionjessicafan3ckNo ratings yet

- Historical Aspects of TranslationDocument6 pagesHistorical Aspects of TranslationGabriel Dan BărbulețNo ratings yet

- Troy and The True Story of The Trojan WarDocument22 pagesTroy and The True Story of The Trojan WarsedenmodikiNo ratings yet

- Translation Studies and The History of Science - The Greek Textbooks of The 18th CenturyDocument18 pagesTranslation Studies and The History of Science - The Greek Textbooks of The 18th CenturyambulafiaNo ratings yet

- Universal HistoryDocument526 pagesUniversal Historykabatta100% (1)

- Soheil M. Afnan - Philosophical Terminology in Arabic and PersianDocument63 pagesSoheil M. Afnan - Philosophical Terminology in Arabic and Persian4im100% (5)

- Humanist Learning PAul Oskar KristellerDocument19 pagesHumanist Learning PAul Oskar KristellerRodrigo Del Rio JoglarNo ratings yet

- The Early History of India from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan ConquestFrom EverandThe Early History of India from 600 B.C. to the Muhammadan ConquestNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Italian RenaissanceDocument7 pagesThesis For Italian Renaissanceafbteuawc100% (1)

- Coptic Old TestamentDocument11 pagesCoptic Old TestamentDr. Ọbádélé KambonNo ratings yet

- L'Antiquité Tardive Dans Les Collections Médiévales: Textes Et Représentations, VI - Xiv SiècleDocument22 pagesL'Antiquité Tardive Dans Les Collections Médiévales: Textes Et Représentations, VI - Xiv Sièclevelibor stamenicNo ratings yet

- Turkey Before Ottoman EmpireDocument7 pagesTurkey Before Ottoman Empiremervy83No ratings yet

- Harris Complete Latin GrammarDocument68 pagesHarris Complete Latin GrammarGustavoGÑopoNo ratings yet

- A Different Perspective: The Traveler's Guide to Medieval (Islamic) Spain and PortugalFrom EverandA Different Perspective: The Traveler's Guide to Medieval (Islamic) Spain and PortugalNo ratings yet

- Maria Mavroudi Greek Language and Education Under Early IslamDocument48 pagesMaria Mavroudi Greek Language and Education Under Early IslamvartanmamikonianNo ratings yet

- (J. P. Louw) New Testament Greek - The Present State of The Art (Artículo) PDFDocument15 pages(J. P. Louw) New Testament Greek - The Present State of The Art (Artículo) PDFLeandro Velardo100% (1)

- Gallego (M. A.) - The Languages of Medieval Iberia and Their Religious Dimension PDFDocument34 pagesGallego (M. A.) - The Languages of Medieval Iberia and Their Religious Dimension PDFJean-Pierre MolénatNo ratings yet

- Classical Studies and Indology by Michael WitzelDocument44 pagesClassical Studies and Indology by Michael WitzelWen-Ti LiaoNo ratings yet

- C A H L: Anon and Rchive IN Umanist AtinDocument24 pagesC A H L: Anon and Rchive IN Umanist AtinalexfelipebNo ratings yet

- The Language of Gesture Early Modern Italy: Peter BurkeDocument13 pagesThe Language of Gesture Early Modern Italy: Peter BurkeramonabaseNo ratings yet

- Latin and Arabic: Entangled HistoriesDocument289 pagesLatin and Arabic: Entangled Historieshcarn2016100% (2)

- BillerDocument16 pagesBillerRog DonNo ratings yet

- Algazel LatinusDocument64 pagesAlgazel LatinusDaniela Cruz GuzmánNo ratings yet

- Browning - Robert 1983 Medieval - And.modern - Greek PDFDocument164 pagesBrowning - Robert 1983 Medieval - And.modern - Greek PDFNatalia100% (2)

- Intercultural Roots - PaperDocument15 pagesIntercultural Roots - PaperJohn MarenbonNo ratings yet

- Lindsay - A Short Historical Latin GrammarDocument244 pagesLindsay - A Short Historical Latin GrammarKevin Harris100% (1)

- Hooker Early Balkan Scripts and The Ancestry of Lenear ADocument16 pagesHooker Early Balkan Scripts and The Ancestry of Lenear ARo OrNo ratings yet

- History of TranslatoinDocument6 pagesHistory of TranslatoinMarysia AndrunyszynNo ratings yet

- IOWP Reinfandt Arabic PapyrologyDocument27 pagesIOWP Reinfandt Arabic PapyrologymaysNo ratings yet

- In Good Faith: Arabic Translation and Translators in Early Modern SpainFrom EverandIn Good Faith: Arabic Translation and Translators in Early Modern SpainNo ratings yet

- Chemistry Lab Report RubricDocument1 pageChemistry Lab Report Rubricapi-266557448No ratings yet

- Top Ten Tips For ILETS ReadingDocument3 pagesTop Ten Tips For ILETS ReadingEhsan KarimNo ratings yet

- Quarter 2 - Module 2: Renaissance and Baroque Period Sculpture: Elements and PrinciplesDocument16 pagesQuarter 2 - Module 2: Renaissance and Baroque Period Sculpture: Elements and Principleskyl100% (1)