Professional Documents

Culture Documents

32 2843 PDF

32 2843 PDF

Uploaded by

Aisyah Aftita KamrasyidOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

32 2843 PDF

32 2843 PDF

Uploaded by

Aisyah Aftita KamrasyidCopyright:

Available Formats

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH

SOCIODEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS OF FOOD

HANDLERS AND THEIR KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE AND

PRACTICE TOWARDS FOOD SANITATION :

A PRELIMINARY REPORT

Maizun Mohd Zain and Nyi Nyi Naing

Department of Community Medicine, School of Medical Sciences, Universiti Sains

Malaysia, 16150 Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia

Abstract. Diseases spread through food still remain a common and persistent problems resulting

in appreciable morbidity and occasional mortality. Food handlers play an important role in

ensuring food safety throughout the chain of production, processing, storage and preparation. This

study is to explore the pattern of sociodemographic distribution and to determine knowledge,

attitude and practice of food handlers towards food-borne diseases and food safety. A total of

430 food handlers were randomly selected from Kota Bharu district and interviewed by using

structured questionnaire. Distribution of food handlers was Malays (98.8%), females (69.5%),

married (81.4%), working in food stalls (64.2%), involved in operational areas (49.3%), having

no license (54.2%) and immunized with Ty2 (60.7%). The mean age was 41 12 years and the

mean income was RM 465 243/month. The educational level was found as no formal education

(10.5%), primary school (31.9%), secondary school (57.0%) and diploma/degree holders (0.7%).

A significant number of food handlers (57.2%) had no certificate in food handlers training

program and 61.9% had undergone routine medical examinations (RME). Almost half (48.4%)

had poor knowledge. Multiple logistic regression showed type of premise [Odd ratio (OR) = 4.0,

95% Confidence interval (CI) =1.8-7.5, p = 0.0004], educational level (OR = 4.0, 95% CI = 1.8-

7.4, p = 0.0003) and job status of food handlers (OR = 0.5, 95% CI = 0.3-0.8, p = 0.0031)

significantly influenced the level score of knowledge. No significant difference of attitude and

practice between trained and untrained food handlers. Findings of this preliminary study may help

in planning health education intervention programs for food handlers in order to have improve-

ment in knowledge, attitude and practice towards food-borne diseases and food safety. Further-

more, it will in turn reduce national morbidity and mortality of food-borne diseases.

INTRODUCTION an endemic food- and water-borne disease and

cases occur periodically; in addition, typhoid

and hepatitis A are endemic in the state and

Food is an important basic necessity: its give rise to clusters of disease and periodic

procurement, preparation, and consumption are outbreaks (Ministry of Health, 1998a). In the

vital for the sustenance of life. However, diseases United States, between 24 and 81 million people

spread through food are common and persis- become ill each year from the consumption of

tent problems that rusult in appreciable mor- contaminated foods and many cases of food-

bidity and occasionally in death. (Ministry of related illness are caused by the mishandling

Health, 1998a; Ranjit, 1998; WHO, 1998). Food- of food, especially in retail establishments

borne diseases are increasing in both devel- (Climent, 1999).

oped and developing countries (Ranjit, 1998;

WHO, 1998; Kaferstein and Abdussalam, 1999). Food-borne disease is attributed to a wide

The main diseases are typhoid, cholera, hepa- variety of bacteria, parasites and viruses. It is

titis A, food poisoning and dysentery. Kelantan found worldwide and cause human illness just

has more cases of typhoid and hepatitis A than about everywhere (Scott and Sockett, 1998;

any other state in Malaysia; cholera remains Tauxe, 1998; WHO, 1998). While the pathol-

410 Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002

SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS AND KAP OF FOOD HANDLERS

ogy, disease spectrum and causative agents distribution of food handlers and determining

differ, the same basic disease risk factors their knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP)

influence transmission. Although numerous of food sanitation. The results of this study

control strategies are in place, person-to-per- may help in identifying proper and suitable

son disease transmission has not ceased. Food methods for planning health education pro-

handlers play an important role in ensuring grams for food handlers that will improve their

food safety throughout the chain of production, knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Evaluation

processing, storage, and preparation (Hedberg is an essential component in determining the

et al, 1994; Goh, 1997; WHO, 1998). Approxi- effectiveness of health education programs.

mately 10 to 20% of food-borne disease Health education programs may reduce na-

outbreaks are due to contamination by the food tional morbidity, mortality, and the transmis-

handler. The mishandling of food and the sion of food-borne diseases.

disregard of hygienic measures enable patho-

gens to come into contact with food and, in

some cases, to survive and multiply in suffi- MATERIALS AND METHODS

cient numbers to cause illness in consumers.

Personal hygiene and environmental sanitation

are key factors in the transmission of food- This study was the preliminary phase of

borne diseases. Investigations of outbreaks of a three-phase non-randomized controlled trial:

food-borne disease throughout the world show Phase I included preliminary data collection

that, in nearly all instances, they are caused (sociodemographics and KAP) related to food-

by the failure to observe satisfactory standards borne diseases and food safety; Phase II was

in the preparation, processing, cooking, storing an intervention program involving both inter-

or retailing of food (Yew et al, 1993; Merican, vention and control groups. Interventions were

1997; Luby et al, 1998; WHO, 1988b). conducted in the Peringat Subdistrict (health

education on food-borne disease and food safety

In Malaysia, the Food Quality Control for food handlers) and in the Ketereh subdis-

Division (FQCD) of the Ministry of Health trict (control group; health education on healthy

(MOH) runs the food control program. The diet was given); Phase III was an evaluation

training of food handlers started in 1996; 90,170 on the effectiveness of the intervention pro-

food handlers were trained from 1996 to 1998 gram.

(FQCD, 2000). The training program is being

conducted by private training institutions ac- During the period January 1st to March

st

credited by the FQCD. With training, it was 31 , 2001 (Phase I), 430 food handlers were

expected that the food handlers would adopt recruited: 215 from each of the two sub-dis-

good hygienic practices that would lead to the tricts, Peringat and Ketereh. The food handlers

reduction of food-borne diseases. In Kelantan, were contacted directly at their premises; a list

the total number of food handlers was 29,124 of food handlers was obtained from the reg-

of which 1,317 (4.5%) were trained in 2000 istry of Kota Bharu District Council. The purpose

(FQCD, 2000). of the study was explained and the informed

consent of each food handler was obtained. A

Education, training, and the development questionnaire was developed and pretested in

of food safety certification examinations are Bahasa Melayu; the validity and reliability of

key components in the process of ensuring that the questionnaire were tested using prelimi-

food handlers are proficient in and knowledge- nary data. There were 2 sections in the ques-

able about food safety and sanitation principles tionnaire: (i) sociodemography and (ii) knowl-

(Jacob, 1989); it is important to emphasize the edge, attitude, and practice (KAP) of food-

effectiveness of health education programs for borne disease and food handling. The socio-

food handlers. This study was conducted with demographic section included: age, race, sex,

the aim of exploring the sociodemographic marital status, educational level, food-handling

Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002 411

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH

status, duration of experience, training status, were categorized as: poor or adequate knowl-

license status, immunization status, type of edge, poor or good attitude and poor or good

food establishment, and income. Food estab- practice based on the summation of individual

lishments were inspected, with an emphasis on scores of the variables. Potential influencing

personal hygiene and environmental sanitation. factors towards knowledge were examined by

Trained interviewers administered the ques- using univariate and multivariate analyses .

tionnaires and inspected food establishments. For univariate analysis, simple logistic regres-

sion was applied to identify significant vari-

Food handler was defined as a person in ables. Variables that were found statistically

the food trade or someone professionally as- significant in univariate analysis, biologically

sociated with it, such as an inspector who, in plausible and those under main interests of the

his routine work, comes into direct contact study were included in multivariate analysis.

with food in the course of its production, Final model was estimated by applying mul-

processing, packaging or distribution (includ- tiple logistic regression. Maximum likelihood

ing raw milk for direct consumption) (WHO, ratio estimation was used to estimate the

1988b). Food was defined as every article parameters and the goodness of fit was applied

manufactured, sold, or represented for use as to assess models. The 95% confidence interval

food or drink for human consumption, or any with 5% level of significance was taken.

item than enters into or is used in the com- Likelihood ratio (LR) test was applied to assess

position, preparation, or preservation of any the statistical significance. The results were

food or drink. Food and drink includes con- presented by appropriate tabulations based on

fectionery and chewing substances and their the determined variables, crude or adjusted

respective ingredients (Food Act 1983; FQCD, odds ratio with 95% confidende interval and

1999). Premises included any building or tent its corresponding p-values.

or any other structure, permanent or otherwise,

together with the land on which the building,

tent or other structure is situated and any

RESULTS

adjoining land used in connection therewith

and any vehicle, conveyance, vessel or air-

Distribution of food handlers by socio-

craft; and for the purpose of any street, open

demograhic variables were Malays (98.8%),

space or place of public resort or bicycle or

females (69.5%), married (81.4%), working in

any vehicle used for or in connection with the

food stall (64.2%), involved in operational areas

preparation, preservation, packaging, storage,

(49.3%), having no license (54.2%) and im-

conveyance, distribution or sale of any food

munized with Ty2 (60.7%). The mean age was

(Food Act 1983; FQCD, 1999).

41 12 years with range 14 to 70 years and

Statistical analysis the mean income was RM 465 243/month.

The educational level was found as no formal

Sample size estimation was calculated education (10.5%), primary school (31.9%),

based on the proportion of food handlers in secondary school (57.0%) and diploma/degree

Kelantan. The required sample size was 430 holders (0.7%). A significant number of food

food handlers. Factor and reliability analyses handlers (57.2%) had no certificate in food

were applied on 100 food handlers to test handlers training program and 61.9% have

validity and reliability of questionnaire. Data undergone routine medical examination(RME).

were entered and analyzed by SPSS software Fig 1 shows that most of the food handlers

version 9.0 (Norusis, 1999). Initially subjects had adequate knowledge about mode of trans-

were classified into trained and untrained food mission (82.1%) and mode of prevention

handlers in order to assess the difference of (83.3%) of food-borne diseases. They had poor

knowledge, attitude and practice between them. knowledge in etiology (58.8%), symptoms

The score of knowledge, attitude and practice (59.3%) and treatment (52.6%). Attitude to-

412 Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002

SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS AND KAP OF FOOD HANDLERS

wards food-borne diseases was good almost in 93.5

99.1

94.4 95.3

all aspects, awareness of seriousness (93.5%), 100

belief as a curable disease (99.1%), belief as 90

a preventable disease (94.4%) and belief of the 80

70

importance of training program (95.3%) except

Percentage (%)

60

in awareness of personal hygiene (55.8%) as

50

shown in Fig 2. On the contrary practice towards 40

food-borne disease and food safety was poor 30

in view of hand washing (50.9%), personal 20 6.5 0.9 5.6 4.7

hygiene (63.7%), treatment (50.2%) and safety 10

food handling (54.7%) as shown in Fig 3. 0

Awareness of Belief as a Belief as a Belief the

There were significant differences of knowl- seriousness curable disease preventable importance of

edge (2 = 4.6, p<0.05) and practice (2 = 5.1, disease training program

p<0.05) between trained and untrained food Attitude Good

handlers. However, there was no significant Poor

difference of attitude between them. Fig 2Attitude towards food-borne diseases by food

On univariate analysis, there were signifi- handlers (n = 430).

cant differences between poor and adequate

knowledge regarding educational level, job

status, sex, license, type of premise and train-

ing. Crude odds ratio with corresponding 95% 63.7

confidence interval and p values were shown 70 54.7

in Table 1. 50.9 50.2 49.8

60 49.1

45.3

On multivariate analysis (multiple logistic 50 36.3

Percentage (%)

regression) variables that were found as sig-

40

nificant potential influencing factors were type

of premise predominantly food stall and level 30

of education mainly secondary school. Ad- 20

10

0

Hand washing Personal hygiene Treatment Safety food

handling

Good

83.3

Practice

90 82.1 Adequate Poor

80 Poor

70 58.8 59.3

Fig 3Practice towards food-borne disease by food

handlers (n = 430).

Percentage (%)

60 52.6

47.4

50 41.2 40.7

40

30

justed odds ratio with their confidence inter-

17.9 16.7

20

vals and p values were shown in Table 2.

10

0

Etiology Mode of Mode of Symptoms Treatment DISCUSSION

transmission prevention

Knowledge

From this preliminary study, a significant

Fig 1Knowledge about food-borne diseases among number of food handlers (57.2%) were not

food handlers (n = 430). trained under food handlers training program

Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002 413

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH

Table 1

Univariate analysis of relationship between knowledge and sociodemographic factors.

Variables Knowledgea (n=208) Crude OR,(95% CI) p-value

Age (meanSD) 41 12 0.0008c 0.927b

Income (meanSD) 457 246 0.0003c 0.503b

Sex (%)

Male 51 (24.5) 1.0

Female 157 (75.5) 0.6 (0.4-0.9) 0.010b

Marital status (%)

Single 31 (14.9) 1.0 0.262b

Married 165 (79.3) 1.3 (0.7-2.2) 0.374

Divorce 5 (2.4) 1.8 (0.5-6.3) 0.333

Others 7 (3.4) 0.3 (0.1-1.7) 0.188

Level of education (%)

No formal education 31 (14.9) 1.0 0.001b

Primary school 78 (37.5) 1.7 (0.8-3.4) 0.158

Secondary school 98 (47.1) 3.3 (1.7-6.6) 0.001

Diploma/degree 1 (0.5) 4.4 (0.4-52.9) 0.240

License (%)

No 126 (60.6) 1.0

Yes 82 (39.4) 1.7 (1.1-2.4) 0.010b

RME (%)

No 87 (41.8) 1.0

Yes 121 (58.2) 1.4 (0.9-2.0) 0.128b

Duration of experience (%)

<6 months 24 (11.5) 1.0 0.019b

6 months to 1 year 30 (14.4) 0.9 (0.4-1.8) 0.692

>1 year to 5 years 75 (36.1) 0.8 (0.4-1.5) 0.481

>5 years to 10 years 26 (12.5) 1.9 (0.9-3.9) 0.077

>10 years 53 (25.5) 0.7 (0.4-1.4) 0.347

Type of premise (%)

Restaurant 32 (15.4) 1.0 0.001b

Food stall 112 (53.8) 3.6 (1.8-7.2) 0.001

School canteen 64 (30.8) 1.7 (0.8-3.7) 0.152

Status (%)

Management 87 (41.8) 1.0

Operation 121 (58.2) 0.5 (0.3-0.7) 0.001b

Training (%)

No 130 (62.5) 1.0

Yes 78 (37.5) 1.5 (1.0-2.2) 0.032b

Immunization (%)

No 84 (40.4) 1.0

Yes 124 (59.6) 1.1 (0.7-1.6) 0.657b

a

expressed as percentage of poor score.

b

simple logistic regression.

c

regression coefficient with 95% confidence interval.

and majority of them (65%) were from food started in 1996 and a total of 90,170 food han-

stall, school canteen (22.8%) and restaurant dlers were trained from 1996 to 1998. (FQC

(12.2%). A total of (72%) of untrained had no Unit, 2000). However, as the number of trained

license. In Malaysia, training of food handlers food handlers increased, the food-borne disease

414 Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002

SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS AND KAP OF FOOD HANDLERS

Table 2

Multivariate analysis of relationship between knowledge and significant variables.

Variables Adjusted OR (95%CI) p-value

Sex

Male 1.0

Female 0.7 (0.4-1.1) 0.126

Level of education

No formal education 1.0 -

Primary school 1.5 (0.7-3.2) 0.279

Secondary school 3.6 (1.8-7.4) 0.001

Diploma/degree 5.8 (0.5-72.6) 0.170

License

No 1.0

Yes 0.7 (0.4-1.5) 0.400

Type of premise

Restaurant 1.0 -

Food stall 3.6 (1.8-7.5) 0.001

School canteen 2.0 (0.9-4.3) 0.089

Status

Management 1.0 -

Operation 0.5 (0.3-0.8) 0.003

Training

No 1.0 -

Yes 1.4 (0.9-2.3) 0.153

cases also increased and food poisoning cases insist that all food handlers especially hawk-

mostly occur at school canteens/hostel. It may ers/food stall be registered, licensed and un-

be due to the fact that the target group of food dergone training on basic food hygiene and

handlers or high-risk group of people handling handling. This may need cooperation from local

food were not properly selected and also no government in view of financial support as the

evaluation was done towards the effectiveness food handlers usually had low income. The

of the training program. Therefore it is impor- training programs need an evaluation to ensure

tant to emphasize that all food handlers espe- the effectiveness since majority of food han-

cially hawkers and those involved in food stall dlers had low level of education which may

must be trained before they are allowed to cause poor understanding towards food-borne

operate. Close cooperation between the Minis- diseases and the importance of food safety

try of Health, the Ministry of Education (school measures. Food handlers had poor knowledge

canteens/hostel kitchen) and local government in etiology, symptoms and treatment, as shown

(that issues the licenses for the premises) is in this study.

needed to ensure that all the food handlers are

trained. From this study, food handlers had good

attitude towards food-borne diseases though

This study showed that food stall had four they did not practice accordingly during their

times significantly higher odds of having poor daily activities. Their practice were poor in

knowledge. The main reason of this was food hand washing, personal hygiene and safety

handlers who involved in food stall/hawkers food handling. Hand washing practices should

activities were not all registered with local be emphasized to food handlers as the hands

government, had low level of education and need to be washed carefully before touching

were not trained. An effort must be made to food or any sort and particularly after handling

Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002 415

SOUTHEAST ASIAN J TROP MED PUBLIC HEALTH

raw food ingredient, which will introduce morbidity and mortality of food-borne diseases.

bacteria daily to the kitchen and before con- Education, training and the development of

tinuing with other cooking preparations (Hobbs food safety certification examinations are key

and Roberts, 1993). Hand cleanliness is one components in the process of ensuring that

of the most critical parts of a food producers food handlers are proficient in and knowledge-

daily regimen. Following that, stricter action able about food safety and sanitation prin-

is needed on food establishment with the aid ciples.

of the Food Act of 1983 and the Disease

Prevention and Control Act of 1988. Inspec-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

tion of food premises should be done to ensure

sanitary premises. Priority must be given to

We would like to express our deep ap-

school canteens and hostel kitchens because

preciation to Dr Rahman Muda, State Director

food poisoning cases usually occurred mainly

of Health, Kelantan; Dr Hamzah Awang Mat,

in schools and institutions. In 1997, the total

District Health Officer, Kota Bharu; all staff

number of inspections on hostel kitchens and

at District Health Office, Kota Bharu and all

school canteens is only 9%(4,323) of the total

staff at Majlis Daerah Kota Bharu. We would

number of inspections instead of total number

also like to thank the Ministry of Science,

of school canteens present in 1997 is about

Technology and Environment, Malaysia for

6,224 (FQC Unit, 2000). Unhygienic premises

funding this project under IRPA RM7.

should not be allowed to operate unless up-

graded.

Food handlers often have little understand- REFERENCES

ing of the risk of microbial or chemical con-

tamination of food or how to avoid them (Hobbs Climent J. The Centres for Disease Control and Pre-

vention (CDC). Study quantifies foodborne ill-

and Roberts, 1993). As the poorly paid job,

ness. Br Med J 1999; 319: 873.

it is poorly motivated and rapid staff turnover

also causes problems. Food handlers should Food Act. Laws of Malaysia: Food Act and Regula-

tions, 9th ed. Kuala Lumpur: MDC Publishers

therefore receive suitable training in the basic

Printers, 1983.

principles of food safety (WHO, 1998). Par-

Food Quality Control Division (FQCD), Ministry of

ticular attention should be given to the impor-

Health, Malaysia,1999.

tance of time and temperature control, personal

hygiene, cross contamination, sources of con- Food Quality Control Unit Report, Health State Office,

Kelantan. Ministry of Health, Malaysia, 2000.

tamination and the factors determining the

survival and growth of pathogenic organisms Goh KY. Information related to food and water-borne

in food (WHO,1988b; Goh, 1997). At the end disease in Penang. Med J Penang Hosp 1997; 2:

42-7.

of the training period, the knowledge and un-

derstanding of food safety on the part of food Hedberg CW, MacDonald KL, Osterholm MT. Chang-

handlers should be tested. The use of attractive ing epidemiology of food-borne disease : A Min-

nesota perspective. Clin Infect Dis 1994; 18:

and explicit poster-type displays in workrooms

671-82.

is considered to be effective way of reminding

food handlers of various aspects of food safety Hobbs BC, Roberts D. Food poisoning and food hy-

giene, 6th ed. London: St Edmunsbury Press,

(WHO, 1988b).

1993.

Findings of this preliminary study may Jacob M. Safe food handling - A training guide for

help in planning health education intervention managers of food service establishments.

programs for food handlers in order to have Geneva: World Health Organization, 1989.

improvement in knowledge, attitude and prac- Kaferstein F, Abdussalam M. Food safety in the 21st

tice towards food-borne diseases and food safety. century. Bull WHO 1999; 77: 347-51.

Furthermore, it will in turn reduce national Luby SP, Faizan MK, Fisher- Hoch SP, et al. Risk fac-

416 Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002

SOCIODEMOGRAPHICS AND KAP OF FOOD HANDLERS

tors for typhoid fever in an endemic setting, Tauxe RV. Food-borne illnesses: Strategies for surveil-

Karachi, Pakistan. Epidemiol Infect 1998; 120: lance and prevention. National Center for Infec-

129-38. tious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and

Merican I. Typhoid fever: present and future. Med J Prevention, Atlanta. Lancet 1998; 352 (suppl

Malaysia 1997; 52: 299-309. review): 10.

Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Food-borne disease. World Health Organization. Education for health. A

Malaysia Health Report. Ministry of Health, manual on health education in primary health

1998a. care. Geneva: World health Organization, 1988a.

Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Annual report on com- World Health Organization. Report of a WHO Consul-

municable diseases. Kelantan: Ministry of Health tation, Health surveillance and management pro-

1998b. cedures for food-handling personnel. Geneva:

Norusis MJ. SPSS 9.0. Guide to data analysis. New World Health Organization, 1988b.

Jersy: Prentice-Hall, 1999. World Health Organization. Life in the 21st century. A

Ranjit K. Food and water-borne diseases in Kelantan. vision for all. The World Health Report. Geneva:

Kelantan Health Conference, 1998. World Health Organization, 1998.

Scott E, Sockett P. How to prevent food poisoning. A Yew FS, Goh KT Lim YS. Epidemiology of typhoid

practical guide to safe cooking, eating and food fever in Singapore. Epidemiol Infect 1993; 110:

handling. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 1998. 63-70.

Vol 33 No. 2 June 2002 417

You might also like

- Foodborne Disease Outbreaks in The Philippines (2005-2018)Document20 pagesFoodborne Disease Outbreaks in The Philippines (2005-2018)Fiel Mendoza OgabangNo ratings yet

- Static Trip ManualDocument52 pagesStatic Trip ManualRavijoisNo ratings yet

- Articulo - Food Safety and Education LevelDocument6 pagesArticulo - Food Safety and Education LevelNicole PerezNo ratings yet

- Ijphs Fix B.inggrisDocument14 pagesIjphs Fix B.inggrisrizkimNo ratings yet

- Employee Food Safety KnowledgeDocument10 pagesEmployee Food Safety KnowledgePawitra RamuNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Basic Knowledge On Food Safety and Food Handling Practices Amongst Migrant in MalaysiaDocument10 pagesEvaluation of Basic Knowledge On Food Safety and Food Handling Practices Amongst Migrant in MalaysiaSiska PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Yahaya Musa Balarabe's Project CHAPTER ONE To ThreeDocument25 pagesYahaya Musa Balarabe's Project CHAPTER ONE To ThreeJonah MerabNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Food Safety Practices Among Food Handlers in Selected Food EstablishmentsDocument9 pagesDeterminants of Food Safety Practices Among Food Handlers in Selected Food EstablishmentsIJPHSNo ratings yet

- 234684535Document8 pages234684535Safi MohammedNo ratings yet

- The Evaluation of Food Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and PracticesDocument6 pagesThe Evaluation of Food Hygiene Knowledge, Attitudes, and PracticessyooloveNo ratings yet

- Factors Influence Awareness Canteen Student MalaysiaDocument4 pagesFactors Influence Awareness Canteen Student MalaysiaPawitra RamuNo ratings yet

- Apjeas-2020 7 1 06Document7 pagesApjeas-2020 7 1 06ROY BULTRON CABARLESNo ratings yet

- Microbial Quality and Safety of Cooked Foods Sold in Urban Schools in Ghana: A Review of Food Handling and Health Implications Ghana A Review of Food Handling and Health ImplicationsDocument10 pagesMicrobial Quality and Safety of Cooked Foods Sold in Urban Schools in Ghana: A Review of Food Handling and Health Implications Ghana A Review of Food Handling and Health ImplicationsresearchpublichealthNo ratings yet

- Relationship of Knowledge and Attitude With Food Handling Practices: A Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesRelationship of Knowledge and Attitude With Food Handling Practices: A Systematic ReviewIJPHSNo ratings yet

- The Level of Food Safety Knowledge in Food Establishments in Three Europians ContriesDocument8 pagesThe Level of Food Safety Knowledge in Food Establishments in Three Europians ContriesSiska PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Food Hygiene Among Mobile Food Ven1ors in - 1Document17 pagesKnowledge, Attitudes and Practices of Food Hygiene Among Mobile Food Ven1ors in - 1Samson ArimatheaNo ratings yet

- Food Safety Practices Among Vendors in Capaoay San Jacinto PangasinanDocument4 pagesFood Safety Practices Among Vendors in Capaoay San Jacinto PangasinanPatricia Mae SabadoNo ratings yet

- The International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary ResearchDocument19 pagesThe International Journal of Multi-Disciplinary ResearcheyobNo ratings yet

- Food Label Reading Habit in Indonesian Nutrition Student: Multi-Strata Comparison ReviewDocument7 pagesFood Label Reading Habit in Indonesian Nutrition Student: Multi-Strata Comparison ReviewMaudonlodNo ratings yet

- Food Safety Attitude and Practice QuestiDocument7 pagesFood Safety Attitude and Practice QuestiHamid AshrafNo ratings yet

- ... Thesis About Proper Hygiene Awareness Towards Food ProductionDocument25 pages... Thesis About Proper Hygiene Awareness Towards Food ProductionAngelie UmambacNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyDocument70 pagesThe Problem and Its Setting Background of The StudyJoana Mae M. Wamar100% (1)

- Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude and Hygiene Practices Among The Street Food Vendors in Northern Kuching City, SarawakDocument9 pagesFood Safety Knowledge, Attitude and Hygiene Practices Among The Street Food Vendors in Northern Kuching City, SarawakFidya Ardiny50% (2)

- Thesis About Improper Hygiene11Document18 pagesThesis About Improper Hygiene11Angelie UmambacNo ratings yet

- Food Safety Attitude of Culinary Arts Based Students in Public PDFDocument11 pagesFood Safety Attitude of Culinary Arts Based Students in Public PDFsyooloveNo ratings yet

- Predicting Relationship Between Food-Borne Disease Information-Adequacy and Food Handling Practices Among Food-Handlers in Selected Restaurants in Ggaba Kampala, Makindye Division UgandaDocument8 pagesPredicting Relationship Between Food-Borne Disease Information-Adequacy and Food Handling Practices Among Food-Handlers in Selected Restaurants in Ggaba Kampala, Makindye Division UgandaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Food Safety Knowledge and Self-Reported Practices PDFDocument29 pagesFood Safety Knowledge and Self-Reported Practices PDFAlle Eiram PadilloNo ratings yet

- Barbosa 2020Document9 pagesBarbosa 2020Doris Xilena Caicedo ViverosNo ratings yet

- Food Hygiene, Market Sanitation and Nutrition - BSPH 223Document159 pagesFood Hygiene, Market Sanitation and Nutrition - BSPH 223Jaward Charles M SL-PromizNo ratings yet

- Local Media332677152785013991Document9 pagesLocal Media332677152785013991Jehan Marie GiananNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, Self-Reported Practices, and Microbiological Hand Hygiene of Food HandlersDocument14 pagesAssessment of Food Safety Knowledge, Attitude, Self-Reported Practices, and Microbiological Hand Hygiene of Food HandlersNadanNadhifahNo ratings yet

- Adellade Luchinga ProjectDocument14 pagesAdellade Luchinga ProjectDERRICK OCHIENGNo ratings yet

- Food Handling Serving and Hygiene PractiDocument7 pagesFood Handling Serving and Hygiene PractiFarha KamilatunNo ratings yet

- RESEARCH - Chapter 1Document9 pagesRESEARCH - Chapter 1Ivan PadecioNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Some Hotel Kitchen Staff On Their Knowledge On Food Safety and Kitchen Hygiene in The Kumasi MetropolisDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Some Hotel Kitchen Staff On Their Knowledge On Food Safety and Kitchen Hygiene in The Kumasi MetropolisIwan Suryadi MahmudNo ratings yet

- 8-Article Text-13-1-10-20200803Document10 pages8-Article Text-13-1-10-20200803Adonis BesaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Hygiene Guidelines On Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Food Handlers at University CafeteriasDocument12 pagesEffect of Hygiene Guidelines On Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices of Food Handlers at University CafeteriasOSCAR DE JESUS FLORESNo ratings yet

- A Cross Sectional Study On Food Safety Knowledge Among Adult ConsumersDocument8 pagesA Cross Sectional Study On Food Safety Knowledge Among Adult ConsumersAlina ShahidNo ratings yet

- Assesment of Personal Hygiene of Canteen Workers of Government Medical College and Hospital, Solapur PDFDocument4 pagesAssesment of Personal Hygiene of Canteen Workers of Government Medical College and Hospital, Solapur PDFRutvik ChawareNo ratings yet

- Food Control: Norrakiah Abdullah Sani, Oi Nee SiowDocument8 pagesFood Control: Norrakiah Abdullah Sani, Oi Nee SiowJerod KingNo ratings yet

- Background of The StudyDocument3 pagesBackground of The StudyKraeNo ratings yet

- Essay Article On Consumer Awareness Towards Food SafetyDocument4 pagesEssay Article On Consumer Awareness Towards Food SafetyMohd Faizal Bin AyobNo ratings yet

- Group 7 BSN 3h Research ProposalDocument69 pagesGroup 7 BSN 3h Research ProposalLeah Mae TomasNo ratings yet

- 9+food Safety and Hygiene Standards in The Hospitality Industry by Sarthak Mahajan and Anshu SinghDocument16 pages9+food Safety and Hygiene Standards in The Hospitality Industry by Sarthak Mahajan and Anshu Singhmaedehmohamadian80No ratings yet

- Food Control: ReviewDocument13 pagesFood Control: ReviewyovikaNo ratings yet

- Main PDFDocument13 pagesMain PDFyovikaNo ratings yet

- Alberta Chapter One To TwoDocument30 pagesAlberta Chapter One To TwoErnest OclooNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaDocument10 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude and Practices Concerning Food Safety Among Restaurant Workers in Putrajaya, MalaysiaAlexander DeckerNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument19 pagesResearch PaperDearlyne AlmazanNo ratings yet

- Keamanan Pangan Dimasa PandemiDocument5 pagesKeamanan Pangan Dimasa PandemiAnita Dewi MoelyaningrumNo ratings yet

- Food Sanitation and Hygiene Practices Among Food Handlers in Food Joints in HyderabadDocument6 pagesFood Sanitation and Hygiene Practices Among Food Handlers in Food Joints in HyderabadEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Research Paper (Judy Garcia & Ybeth Duerme)Document8 pagesResearch Paper (Judy Garcia & Ybeth Duerme)Judy GarciaNo ratings yet

- Research Ma'Am PauDocument32 pagesResearch Ma'Am PauKristine PascuaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Food Hygiene Practices of Food Handlers in The Federal Capital Territory of NigeriaDocument6 pagesAssessment of The Food Hygiene Practices of Food Handlers in The Federal Capital Territory of Nigeriarafael514No ratings yet

- Asante FinalDocument52 pagesAsante FinalErnest OclooNo ratings yet

- Food Control: J.M. Soon, R.N. BainesDocument12 pagesFood Control: J.M. Soon, R.N. BainesjaristizabalNo ratings yet

- Food Safety FAO PaperDocument2 pagesFood Safety FAO PaperKathiravan GopalanNo ratings yet

- Food Hygienic Practices and Safety Measures AmongDocument7 pagesFood Hygienic Practices and Safety Measures AmongIntrovert PrinzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22Document11 pagesChapter 22MaryGraceVelascoFuentesNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment As Applied To Food Sanitation and SafetyDocument55 pagesRisk Assessment As Applied To Food Sanitation and SafetyAllyson Angel IturiagaNo ratings yet

- Food Handler's Manual: InstructorFrom EverandFood Handler's Manual: InstructorRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Comparsion of Intravenous Lignocaine, Tramadol and Keterolac For Attenuation of Propofol Injection PainDocument4 pagesComparsion of Intravenous Lignocaine, Tramadol and Keterolac For Attenuation of Propofol Injection PainAisyah Aftita KamrasyidNo ratings yet

- Isoniazid TuberculosisDocument10 pagesIsoniazid TuberculosisAisyah Aftita KamrasyidNo ratings yet

- Tria Lof Sho Rt-Cou Rse Anti Mic Robi Al The Rapy For Intr Aab Do Min Al Inf Ecti OnDocument23 pagesTria Lof Sho Rt-Cou Rse Anti Mic Robi Al The Rapy For Intr Aab Do Min Al Inf Ecti OnAisyah Aftita KamrasyidNo ratings yet

- Hand-Arm Vibration PolicyDocument27 pagesHand-Arm Vibration PolicyAisyah Aftita KamrasyidNo ratings yet

- Gerinda Dan Keluhan Subyektif (Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome)Document9 pagesGerinda Dan Keluhan Subyektif (Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome)Aisyah Aftita KamrasyidNo ratings yet

- Angular With NodeJS - The MEAN Stack Training Guide - UdemyDocument15 pagesAngular With NodeJS - The MEAN Stack Training Guide - UdemyHarsh TiwariNo ratings yet

- Research On Process of Raising Funds Through QipDocument5 pagesResearch On Process of Raising Funds Through QipRachit SharmaNo ratings yet

- AppsDocument6 pagesAppsxxres4lifexxNo ratings yet

- First Certificate Booklet 2Document89 pagesFirst Certificate Booklet 2Alina TeranNo ratings yet

- A Concept Paper About LoveDocument5 pagesA Concept Paper About LoveStephen Rivera100% (1)

- Chu Chin Chow - Libretto (Typescript)Document68 pagesChu Chin Chow - Libretto (Typescript)nathan_hale_jrNo ratings yet

- Ancient IndiaDocument9 pagesAncient IndiaAchanger AcherNo ratings yet

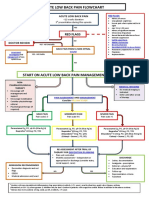

- Acute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 2017Document1 pageAcute Low Back Pain Flowchart January 20171234chocoNo ratings yet

- FILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20Document28 pagesFILM TREATMENT PE-Revised-11.30.20ArpoxonNo ratings yet

- Tia HistoryDocument11 pagesTia HistoryTiara AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Investigative Skills 3Document75 pagesInvestigative Skills 3Keling HanNo ratings yet

- ABB Fittings PlugsDocument204 pagesABB Fittings PlugsjohnNo ratings yet

- Sexy Book 121Document252 pagesSexy Book 121Irepan Ponce50% (2)

- Advent Jesse Tree - 2013Document35 pagesAdvent Jesse Tree - 2013Chad Bragg100% (1)

- MSDS - Prominent-GlycineDocument6 pagesMSDS - Prominent-GlycineTanawat ChinchaivanichkitNo ratings yet

- Api 577 Q 114Document31 pagesApi 577 Q 114Mohammed YoussefNo ratings yet

- Theis Topics - MA in Teaching English As A Foreign LanguageDocument14 pagesTheis Topics - MA in Teaching English As A Foreign LanguageAnadilBatoolNo ratings yet

- 17 Artikel Analisis Komponen Produk Wisata Di Kabupaten KarawangDocument10 pages17 Artikel Analisis Komponen Produk Wisata Di Kabupaten KarawangPutri NurkarimahNo ratings yet

- Handout - Education in EmergenciesDocument31 pagesHandout - Education in EmergenciesFortunatoNo ratings yet

- Project Management Process GroupsDocument10 pagesProject Management Process GroupsQueen Valle100% (1)

- DB (04.2013) HiromiDocument7 pagesDB (04.2013) HiromiLew Quzmic Baltiysky75% (4)

- Bunk Bed Plans SampleDocument4 pagesBunk Bed Plans SampleCedrickNo ratings yet

- Main Slokas With MeaningDocument114 pagesMain Slokas With MeaningRD100% (1)

- Sep. Gravimetrica - CromitaDocument13 pagesSep. Gravimetrica - Cromitaemerson sennaNo ratings yet

- Members of The Propaganda MovementDocument2 pagesMembers of The Propaganda MovementjhomalynNo ratings yet

- 哈佛商业评论 (Harvard Business Review)Document7 pages哈佛商业评论 (Harvard Business Review)h68f9trq100% (1)

- Facilio State of Operations and Maintenance SoftwareDocument25 pagesFacilio State of Operations and Maintenance Softwarearunkumar277041No ratings yet

- City of Tampa Disparity Study Report 050206 - Vol - 1Document102 pagesCity of Tampa Disparity Study Report 050206 - Vol - 1AsanijNo ratings yet

- Latex ManualDocument160 pagesLatex Manualcd_levyNo ratings yet